- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a History Essay

Last Updated: December 27, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a Private Tutor and Life Coach in Santa Cruz, California. In 2018, she founded Mindful & Well, a natural healing and wellness coaching service. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. Emily also received her Wellness Coach Certificate from Cornell University and completed the Mindfulness Training by Mindful Schools. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 244,610 times.

Writing a history essay requires you to include a lot of details and historical information within a given number of words or required pages. It's important to provide all the needed information, but also to present it in a cohesive, intelligent way. Know how to write a history essay that demonstrates your writing skills and your understanding of the material.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- The key words will often need to be defined at the start of your essay, and will serve as its boundaries. [2] X Research source

- For example, if the question was "To what extent was the First World War a Total War?", the key terms are "First World War", and "Total War".

- Do this before you begin conducting your research to ensure that your reading is closely focussed to the question and you don't waste time.

- Explain: provide an explanation of why something happened or didn't happen.

- Interpret: analyse information within a larger framework to contextualise it.

- Evaluate: present and support a value-judgement.

- Argue: take a clear position on a debate and justify it. [3] X Research source

- Your thesis statement should clearly address the essay prompt and provide supporting arguments. These supporting arguments will become body paragraphs in your essay, where you’ll elaborate and provide concrete evidence. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Your argument may change or become more nuanced as your write your essay, but having a clear thesis statement which you can refer back to is very helpful.

- For example, your summary could be something like "The First World War was a 'total war' because civilian populations were mobilized both in the battlefield and on the home front".

- Pick out some key quotes that make your argument precisely and persuasively. [5] X Research source

- When writing your plan, you should already be thinking about how your essay will flow, and how each point will connect together.

Doing Your Research

- Primary source material refers to any texts, films, pictures, or any other kind of evidence that was produced in the historical period, or by someone who participated in the events of the period, that you are writing about.

- Secondary material is the work by historians or other writers analysing events in the past. The body of historical work on a period or event is known as the historiography.

- It is not unusual to write a literature review or historiographical essay which does not directly draw on primary material.

- Typically a research essay would need significant primary material.

- Start with the core texts in your reading list or course bibliography. Your teacher will have carefully selected these so you should start there.

- Look in footnotes and bibliographies. When you are reading be sure to pay attention to the footnotes and bibliographies which can guide you to further sources a give you a clear picture of the important texts.

- Use the library. If you have access to a library at your school or college, be sure to make the most of it. Search online catalogues and speak to librarians.

- Access online journal databases. If you are in college it is likely that you will have access to academic journals online. These are an excellent and easy to navigate resources.

- Use online sources with discretion. Try using free scholarly databases, like Google Scholar, which offer quality academic sources, but avoid using the non-trustworthy websites that come up when you simply search your topic online.

- Avoid using crowd-sourced sites like Wikipedia as sources. However, you can look at the sources cited on a Wikipedia page and use them instead, if they seem credible.

- Who is the author? Is it written by an academic with a position at a University? Search for the author online.

- Who is the publisher? Is the book published by an established academic press? Look in the cover to check the publisher, if it is published by a University Press that is a good sign.

- If it's an article, where is published? If you are using an article check that it has been published in an academic journal. [8] X Research source

- If the article is online, what is the URL? Government sources with .gov addresses are good sources, as are .edu sites.

- Ask yourself why the author is making this argument. Evaluate the text by placing it into a broader intellectual context. Is it part of a certain tradition in historiography? Is it a response to a particular idea?

- Consider where there are weaknesses and limitations to the argument. Always keep a critical mindset and try to identify areas where you think the argument is overly stretched or the evidence doesn't match the author's claims. [9] X Research source

- Label all your notes with the page numbers and precise bibliographic information on the source.

- If you have a quote but can't remember where you found it, imagine trying to skip back through everything you have read to find that one line.

- If you use something and don't reference it fully you risk plagiarism. [10] X Research source

Writing the Introduction

- For example you could start by saying "In the First World War new technologies and the mass mobilization of populations meant that the war was not fought solely by standing armies".

- This first sentences introduces the topic of your essay in a broad way which you can start focus to in on more.

- This will lead to an outline of the structure of your essay and your argument.

- Here you will explain the particular approach you have taken to the essay.

- For example, if you are using case studies you should explain this and give a brief overview of which case studies you will be using and why.

Writing the Essay

- Try to include a sentence that concludes each paragraph and links it to the next paragraph.

- When you are organising your essay think of each paragraph as addressing one element of the essay question.

- Keeping a close focus like this will also help you avoid drifting away from the topic of the essay and will encourage you to write in precise and concise prose.

- Don't forget to write in the past tense when referring to something that has already happened.

- Don't drop a quote from a primary source into your prose without introducing it and discussing it, and try to avoid long quotations. Use only the quotes that best illustrate your point.

- If you are referring to a secondary source, you can usually summarise in your own words rather than quoting directly.

- Be sure to fully cite anything you refer to, including if you do not quote it directly.

- Think about the first and last sentence in every paragraph and how they connect to the previous and next paragraph.

- Try to avoid beginning paragraphs with simple phrases that make your essay appear more like a list. For example, limit your use of words like: "Additionally", "Moreover", "Furthermore".

- Give an indication of where your essay is going and how you are building on what you have already said. [15] X Research source

- Briefly outline the implications of your argument and it's significance in relation to the historiography, but avoid grand sweeping statements. [16] X Research source

- A conclusion also provides the opportunity to point to areas beyond the scope of your essay where the research could be developed in the future.

Proofreading and Evaluating Your Essay

- Try to cut down any overly long sentences or run-on sentences. Instead, try to write clear and accurate prose and avoid unnecessary words.

- Concentrate on developing a clear, simple and highly readable prose style first before you think about developing your writing further. [17] X Research source

- Reading your essay out load can help you get a clearer picture of awkward phrasing and overly long sentences. [18] X Research source

- When you read through your essay look at each paragraph and ask yourself, "what point this paragraph is making".

- You might have produced a nice piece of narrative writing, but if you are not directly answering the question it is not going to help your grade.

- A bibliography will typically have primary sources first, followed by secondary sources. [19] X Research source

- Double and triple check that you have included all the necessary references in the text. If you forgot to include a reference you risk being reported for plagiarism.

Sample Essay

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/robert-pearce/how-write-good-history-essay

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/writing-a-good-history-paper

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ http://history.rutgers.edu/component/content/article?id=106:writing-historical-essays-a-guide-for-undergraduates

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/c.php?g=344285&p=2580599

- ↑ http://www.hamilton.edu/documents/writing-center/WritingGoodHistoryPaper.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

- ↑ https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/hppi/publications/Writing-History-Essays.pdf

About This Article

To write a history essay, read the essay question carefully and use source materials to research the topic, taking thorough notes as you go. Next, formulate a thesis statement that summarizes your key argument in 1-2 concise sentences and create a structured outline to help you stay on topic. Open with a strong introduction that introduces your thesis, present your argument, and back it up with sourced material. Then, end with a succinct conclusion that restates and summarizes your position! For more tips on creating a thesis statement, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lea Fernandez

Nov 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Matthew Sayers

Mar 31, 2019

Millie Jenkerinx

Nov 11, 2017

Oct 18, 2019

Shannon Harper

Mar 9, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Writing a history essay

An essay is a piece of sustained writing in response to a question, topic or issue. Essays are commonly used for assessing and evaluating student progress in history. History essays test a range of skills including historical understanding, interpretation and analysis, planning, research and writing.

To write an effective essay, students should examine the question, understand its focus and requirements, acquire information and evidence through research, then construct a clear and well-organised response. Writing a good history essay should be rigorous and challenging, even for stronger students. As with other skills, essay writing develops and improves over time. Each essay you complete helps you become more competent and confident in exercising these skills.

Study the question

This is an obvious tip but one sadly neglected by some students. The first step to writing a good essay, whatever the subject or topic, is to give plenty of thought to the question.

An essay question will set some kind of task or challenge. It might ask you to explain the causes and/or effects of a particular event or situation. It might ask if you agree or disagree with a statement. It might ask you to describe and analyse the causes and/or effects of a particular action or event. Or it might ask you to evaluate the relative significance of a person, group or event.

You should begin by reading the essay question several times. Underline, highlight or annotate keywords or terms in the text of the question. Think about what it requires you to do. Who or what does it want you to concentrate on? Does it state or imply a particular timeframe? What problem or issue does it want you to address?

Begin with a plan

Every essay should begin with a written plan. Start constructing a plan as soon as you have received your essay question and given it some thought.

Prepare for research by brainstorming and jotting down your thoughts and ideas. What are your initial responses or thoughts about the question? What topics, events, people or issues are connected with the question? Do any additional questions or issues flow from the question? What topics or events do you need to learn more about? What historians or sources might be useful?

If you encounter a mental ‘brick wall’ or are uncertain about how to approach the question, don’t hesitate to discuss it with someone else. Consult your teacher, a capable classmate or someone you trust. Bear in mind too that once you start researching, your plan may change as you locate new information.

Start researching

After studying the question and developing an initial plan, start to gather information and evidence.

Most will start by reading an overview of the topic or issue, usually in some reliable secondary sources. This will refresh or build your existing understanding of the topic and provide a basis for further questions or investigation.

Your research should take shape from here, guided by the essay question and your own planning. Identify terms or concepts you do not know and find out what they mean. As you locate information, ask yourself if it is relevant or useful for addressing the question. Be creative with your research, looking in a variety of places.

If you have difficulty locating information, seek advice from your teacher or someone you trust.

Develop a contention

All good history essays have a clear and strong contention. A contention is the main idea or argument of your essay. It serves both as an answer to the question and the focal point of your writing.

Ideally, you should be able to express your contention as a single sentence. For example, the following contention might form the basis of an essay question on the rise of the Nazis:

Q. Why did the Nazi Party win 37 per cent of the vote in July 1932? A. The Nazi Party’s electoral success of 1932 was a result of economic suffering caused by the Great Depression, public dissatisfaction with the Weimar Republic’s democratic political system and mainstream parties, and Nazi propaganda that promised a return to traditional social, political and economic values.

An essay using this contention would then go on to explain and justify these statements in greater detail. It will also support the contention with argument and evidence.

At some point in your research, you should begin thinking about a contention for your essay. Remember, you should be able to express it briefly as if addressing the essay question in a single sentence, or summing up in a debate.

Try to frame your contention so that is strong, authoritative and convincing. It should sound like the voice of someone well informed about the subject and confident about their answer.

Plan an essay structure

Once most of your research is complete and you have a strong contention, start jotting down a possible essay structure. This need not be complicated, a few lines or dot points is ample.

Every essay must have an introduction, a body of several paragraphs and a conclusion. Your paragraphs should be well organised and follow a logical sequence.

You can organise paragraphs in two ways: chronologically (covering events or topics in the order they occurred) or thematically (covering events or topics based on their relevance or significance). Every paragraph should be clearly signposted in the topic sentence.

Once you have finalised a plan for your essay, commence your draft.

Write a compelling introduction

Many consider the introduction to be the most important part of an essay. It is important for several reasons. It is the reader’s first experience of your essay. It is where you first address the question and express your contention. It is also where you lay out or ‘signpost’ the direction your essay will take.

Aim for an introduction that is clear, confident and punchy. Get straight to the point – do not waste time with a rambling or storytelling introduction.

Start by providing a little context, then address the question, articulate your contention and indicate what direction your essay will take.

Write fully formed paragraphs

Many history students fall into the trap of writing short paragraphs, sometimes containing as little as one or two sentences. A good history essay contains paragraphs that are themselves ‘mini-essays’, usually between 100-200 words each.

A paragraph should focus on one topic or issue only – but it should contain a thorough exploration of that topic or issue.

A good paragraph will begin with an effective opening sentence, sometimes called a topic sentence or signposting sentence. This sentence introduces the paragraph topic and briefly explains its significance to the question and your contention. Good paragraphs also contain thorough explanations, some analysis and evidence, and perhaps a quotation or two.

Finish with an effective conclusion

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay. A good conclusion should do two things. First, it should reiterate or restate the contention of your essay. Second, it should close off your essay, ideally with a polished ending that is not abrupt or awkward.

One effective way to do this is with a brief summary of ‘what happened next’. For example, an essay discussing Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 might close with a couple of sentences about how he consolidated and strengthened his power in 1934-35.

Your conclusion need not be as long or as developed as your body paragraphs. You should avoid introducing new information or evidence in the conclusion.

Reference and cite your sources

A history essay is only likely to succeed if it is appropriately referenced. Your essay should support its information, ideas and arguments with citations or references to reliable sources.

Referencing not only acknowledges the work of others, but it also gives authority to your writing and provides the teacher or assessor with an insight into your research. More information on referencing a piece of history writing can be found here .

Proofread, edit and seek feedback

Every essay should be proofread, edited and, if necessary, re-drafted before being submitted for assessment. Essays should ideally be completed well before their due date then put aside for a day or two before proofreading.

When proofreading, look first for spelling and grammatical errors, typographical mistakes, incorrect dates or other errors of fact.

Think then about how you can improve the clarity, tone and structure of your essay. Does your essay follow a logical structure or sequence? Is the signposting in your essay clear and effective? Are some sentences too long or ‘rambling’? Do you repeat yourself? Do paragraphs need to be expanded, fine-tuned or strengthened with more evidence?

Read your essay aloud, either to yourself or another person. Seek feedback and advice from a good writer or someone you trust (they need not have expertise in history, only in effective writing).

Some general tips on writing

- Always write in the third person . Never refer to yourself personally, using phrases like “I think…” or “It is my contention…”. Good history essays should adopt the perspective of an informed and objective third party. They should sound rational and factual – not like an individual expressing their opinion.

- Always write in the past tense . An obvious tip for a history essay is to write in the past tense. Always be careful about your use of tense. Watch out for mixed tenses when proofreading your work. One exception to the rule about past tense is when writing about the work of modern historians (for example, “Kershaw writes…” sounds better than “Kershaw wrote…” or “Kershaw has written…”).

- Avoid generalisations . Generalisation is a problem in all essays but it is particularly common in history essays. Generalisation occurs when you form general conclusions from one or more specific examples. In history, this most commonly occurs when students study the experiences of a particular group, then assume their experiences applied to a much larger group – for example, “All the peasants were outraged”, “Women rallied to oppose conscription” or “Germans supported the Nazi Party”. Both history and human society, however, are never this clear cut or simple. Always try to avoid generalisation and be on the lookout for generalised statements when proofreading.

- Write short, sharp and punchy . Good writers vary their sentence length but as a rule of thumb, most of your sentences should be short and punchy. The longer a sentence becomes, the greater the risk of it becoming long-winded or confusing. Long sentences can easily become disjointed, confused or rambling. Try not to overuse long sentences and pay close attention to sentence length when proofreading.

- Write in an active voice . In history writing, the active voice is preferable to the passive voice. In the active voice, the subject completes the action (e.g. “Hitler [the subject] initiated the Beer Hall putsch [the action] to seize control of the Bavarian government”). In the passive voice, the action is completed by the subject (“The Beer Hall putsch [the action] was initiated by Hitler [the subject] to seize control of the Bavarian government”). The active voice also helps prevent sentences from becoming long, wordy and unclear.

You may also find our page on writing for history useful.

Citation information Title : ‘Writing a history essay’ Authors : Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson Publisher : Alpha History URL : https://alphahistory.com/writing-a-history-essay/ Date published : April 13, 2020 Date updated : December 20, 2022 Date accessed : Today’s date Copyright : The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

How to Write a History Essay

The analytical essay.

One of the most important skills you must learn in order to succeed in a history classroom is the art of essay writing. Writing an essay is one of the most common tasks assigned to a history student, and often one of the most daunting. However, once you gain the skills and confidence to write a great essay it can also be one of the most fun assignments you have. Essays allow you to engage with the material you have studied and draw your own conclusions. A good essay shows that you have mastered the material at hand and that you are able to engage with it in a new and meaningful way.

The Thesis Statement

The most important thing to remember when writing an analytical essay is that it calls for you to analyze something. That is to say your essay should have a challengeable argument . An argument is a statement which people can disagree about. The goal of your essay is to persuade the reader to support your argument. The best essays will be those which take a strong stance on a topic, and use evidence to support that stance. You should be able to condense your strong stance into one or two concrete sentences called your thesis statement . The thesis of your essay should clearly lay out what you will be arguing for in your essay. Again, a good thesis statement will present your challengeable argument – the thing you are trying to prove.

Here are two examples

Bad Thesis Statement : Johannes Kepler was an important figure in the Scientific Revolution.

Good Thesis Statement : Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority, gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe, and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method.

As you can see the first thesis statement is not a challengeable argument. The fact that Johannes Kepler was an important figure is not disputed, and an essay to prove that he was important wouldn’t be effective, and would also be no fun to write (or read.)

The second thesis statement however does make a challengeable argument. It argues that Kepler’s discovery helped to progress the scientific revolution and goes on to explain three reasons why. This thesis statement not only poses a challengeable argument, but also outlines the evidence which will be used to prove the argument. Now the reader knows right away what you will be arguing for, and why you believe the argument is correct.

Note : This type of thesis is called a ‘ three-prong thesis .’ There are other valid ways to set up a thesis statement, but the three prong thesis form is a very straightforward approach which is allows both beginner and advanced essayists the ability to clearly define the structure of their essay.

Writing an Introduction

The introduction is the first part of your essay anyone will read and so it is the most important. People make up their minds about the quality of a paper within the first few lines, so it’s important that you start strong. The introduction of your paper must layout the basic premise behind the paper. It should include any background knowledge essential to understanding your argument that is not directly addressed in your paper. In addition, your introduction should telegraph to a reader what your argument will be, and what topics you will discuss. In order write a good intro, there are a few essential elements which you must have.

First, every good introduction has to have a snappy opening or hook . Your first few lines must be engaging to the reader the same way it’s important to make a good impression with a new classmate. Resist the urge to open your paper with a famous quote. Readers never respond favorably to irrelevant epigraphs. Worse still, is the tired tradition of opening your essay with a definition. If your essay opens with “Webster’s dictionary defines blank as…” then you have some serious editing to do. You should always write your papers as though they are being read by an equally educated individual who is not a member of your class. As such, you should assume they already know the definitions of the key terms you are using, or able to look them up on their own time. Instead, you should try to introduce the topic of your paper in some informal way using a relevant anecdote, rhetorical question, interesting fact or metaphor. Your introduction should start out broadly and so your hook can begin introducing your topic informally. At the same time however, your hook must be relevant enough to lead into the meat of your paper.

Once you have a hook and have begun to introduce your topic, it is important to provide a roadmap for your essay. The roadmap is the portion of your introduction in which you briefly explain to your reader where your essay is going. The clearer your roadmap is the more engaged the reader will be. Generally speaking, you should devote one or two sentences to introducing the main ideas in each of your body paragraphs . By doing this you allow the reader to better understand the direction your essay will take. They will know what each body paragraph will be about and understand right way what your argument is and how plan to prove it.

Finally every introduction must include your thesis statement. As discussed above, our thesis statement should be the specific statement of what you are arguing. Make sure it is as clear as possible. The thesis statement should be at the end of your introduction. When you first begin writing essays, it is usually a good idea to make the thesis statement the final sentence of your introduction, but you can play around with the placement of the components of the introduction as you master the art of essay writing.

Remember, a good introduction should be shaped like a funnel. In the beginning your introduction starts broadly, but as it gets more specific as it goes, eventually culminating in the very specific thesis statement.

The body paragraphs of your essay are the meat of the work. It is in this section that you must do the most writing. All of your sub-arguments and evidence which prove your thesis are contained within the body of your essay. Writing this section can be a daunting task – especially if you are faced with what seems like an enormous expanse of blank pages to fill. Have no fear. Though the essay may seem intimidating to completely finish, practice will make essay writing seem easier, and by following these tips you can ensure the body of your essay impresses your reader.

It helps to consider each individual paragraph as an essay within itself. At the beginning of each new paragraph you should have a topic sentence . The topic sentence explains what the paragraph is about and how it relates to your thesis statement. In this way the topic sentence acts like the introduction to the paragraph. Next you must write the body of the paragraph itself – the facts and evidence which support the topic sentence. Finally, you need a conclusion to the paragraph which explains how what you just wrote about related to the main thesis.

Approaching each body paragraph as its own mini essay makes writing the whole paper seem much less intimidating. By breaking the essay up into smaller portions, it’s much easier to tackle the project as a whole.

Another great way to make essay writing easier is to create an outline. We’ll demonstrate how to do that next. Making a through outline will ensure that you always know where you are going. It makes it much easier to write the whole essay quickly, and you’ll never run into the problem of writers block, because you will always have someplace to go next.

Writing The Outline

Before you begin writing an essay you should always write an outline . Be as through as possible. You know that you will need to create a thesis statement which contains your challengeable argument, so start there. Write down your thesis first on a blank piece of paper. Got it? Good.

Now, think about how you will prove your thesis. What are the sub-arguments? Suppose we take our thesis from earlier about Kepler.

Thesis : Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority, gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe, and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method.

What are the sub-arguments here? Well fortunately, because we made our thesis very clear the sub-arguments are easy to find. They are the bolded portions below:

Thesis : Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority , gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe , and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method .

Now we know what the sections of our body should cover and argue:

1) Kepler’s evidence legitimized the need for scientists to question authority. 2) Kepler’s evidence gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe 3) Kepler’s evidence laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method.

Note : The structure we are employing here is called the 5 paragraph essay . When you begin writing essays it is a good idea to master this structure first, and then, once you feel comfortable, you can branch out into different forms. You may also pursue a 5 paragraph essay with the body structure: ‘Narration,’ ‘Affirmation,’ ‘Negation,’ etc. In this structure the first paragraph provides background, the second presents your argument, and the third presents a counter argument which you proceed to rebut.

Now that we know what each body paragraph is about, it is time to fill out what information they will contain. Consider what facts can be used to prove the argument of each paragraph. What sources do you have which might justify your claims? Try your best to categorize your knowledge so that it fits into one of the three groups. Once you know what you want to talk about in each paragraph, try to order it either chronologically or thematically. This will help to give your essay a logical flow.

Once finished your outline should look something like this :

1) Introduction : Thesis: Johannes Kepler’s mathematical evidence supporting the heliocentric model of the universe was instrumental in progressing the scientific revolution because it legitimized the need for scientists to question authority, gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe, and it laid the groundwork for the level of mathematical precision called for in the scientific method. 2) Body Paragraph 1 : legitimized questioning of authority 2.a) Kepler’s discovery proved that the European understanding of the universe was flawed 2.b) By proving that the European understanding was flawed in one area, Kepler’s work suggested there might be flaws in other areas inspiring scientists in all fields to question authority 3) Body Paragraph 2 : gave scientists the tools to begin mapping out the universe 3.a) Kepler’s discovery was widely read by other scientists who were able to expand on his work to make new discoveries 4) Body Paragraph 3 : laid the groundwork for the scientific method 4.a) Kepler’s discovery relied heavily on mathematical proof rather than feelings, or even observations. This made Kepler’s theory able to hold up under scrutiny. 4.b) The method of Kepler’s work impressed Renaissance thinkers like Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes who saw his work as more legitimate than that which came before it. They then measured other scientific work against Kepler’s method of experimental and mathematical proof. 5) Conclusion : Wrap up your paper and explain its importance.

The final part of your essay is the conclusion . The conclusion is the last part of your essay that anyone will read, so it is important that it is also as strong as the introduction. The conclusion should synthesize you argument into one succinct paragraph. You should reiterate your thesis statement – though in slightly different words – and explain how the thesis was proved. Be sure that your conclusion does not simply summarize your paper, but rather ensure that it enhances it. The best way to do this is by explaining how your whole argument fits together. Show in your conclusion that the examples you picked were not just random, but fit together to tell a compelling story.

The best conclusions will also attempt to answer the question of ‘so what?’ Why did you write this paper? What meaning can be taken from it? Can it teach us something about the world today or does it enhance our knowledge of the past? By relating your paper back to the bigger picture you are able to enhance your work by placing it within the larger discussion. If the reader knows what they have gained from reading your paper, then it will have greater meaning to them.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write a dbq essay: key strategies and tips.

Advanced Placement (AP)

The DBQ, or document-based-question, is a somewhat unusually-formatted timed essay on the AP History Exams: AP US History, AP European History, and AP World History. Because of its unfamiliarity, many students are at a loss as to how to even prepare, let alone how to write a successful DBQ essay on test day.

Never fear! I, the DBQ wizard and master, have a wealth of preparation strategies for you, as well as advice on how to cram everything you need to cover into your limited DBQ writing time on exam day. When you're done reading this guide, you'll know exactly how to write a DBQ.

For a general overview of the DBQ—what it is, its purpose, its format, etc.—see my article "What is a DBQ?"

Table of Contents

What Should My Study Timeline Be?

Preparing for the DBQ

Establish a Baseline

Foundational Skills

Rubric Breakdown

Take Another Practice DBQ

How Can I Succeed on Test Day?

Reading the Question and Documents

Planning Your Essay

Writing Your Essay

Key Takeaways

What Should My DBQ Study Timeline Be?

Your AP exam study timeline depends on a few things. First, how much time you have to study per week, and how many hours you want to study in total? If you don't have much time per week, start a little earlier; if you will be able to devote a substantial amount of time per week (10-15 hours) to prep, you can wait until later in the year.

One thing to keep in mind, though, is that the earlier you start studying for your AP test, the less material you will have covered in class. Make sure you continually review older material as the school year goes on to keep things fresh in your mind, but in terms of DBQ prep it probably doesn't make sense to start before February or January at the absolute earliest.

Another factor is how much you need to work on. I recommend you complete a baseline DBQ around early February to see where you need to focus your efforts.

If, for example, you got a six out of seven and missed one point for doing further document analysis, you won't need to spend too much time studying how to write a DBQ. Maybe just do a document analysis exercise every few weeks and check in a couple months later with another timed practice DBQ to make sure you've got it.

However, if you got a two or three out of seven, you'll know you have more work to do, and you'll probably want to devote at least an hour or two every week to honing your skills.

The general flow of your preparation should be: take a practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, and so on. How often you take the practice DBQs and how many times you repeat the cycle really depends on how much preparation you need, and how often you want to check your progress. Take practice DBQs often enough that the format stays familiar, but not so much that you've done barely any skills practice in between.

He's ready to start studying!

The general preparation process is to diagnose, practice, test, and repeat. First, you'll figure out what you need to work on by establishing a baseline level for your DBQ skills. Then, you'll practice building skills. Finally, you'll take another DBQ to see how you've improved and what you still need to work on.

In this next section, I'll go over the whole process. First, I'll give guidance on how to establish a baseline. Then I'll go over some basic, foundational essay-writing skills and how to build them. After that I'll break down the DBQ rubric. You'll be acing practice DBQs before you know it!

#1: Establish a Baseline

The first thing you need to do is to establish a baseline— figure out where you are at with respect to your DBQ skills. This will let you know where you need to focus your preparation efforts.

To do this, you will take a timed, practice DBQ and have a trusted teacher or advisor grade it according to the appropriate rubric.

AP US History

For the AP US History DBQ, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time.

A selection of practice questions from the exam can be found online at the College Board, including a DBQ. (Go to page 136 in the linked document for the practice prompt.)

If you've already seen this practice question, perhaps in class, you might use the 2015 DBQ question .

Other available College Board DBQs are going to be in the old format (find them in the "Free-Response Questions" documents). This is fine if you need to use them, but be sure to use the new rubric (which is out of seven points, rather than nine) to grade.

I advise you to save all these links , or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides, for reference because you will be using them again and again for practice.

AP European History

The College Board has provided practice questions for the exam , including a DBQ (see page 200 in the linked document).

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2016 DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History exam. Just be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board . (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

I advise you to save all these links (or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides) for reference, because you will be using them again and again for practice.

Who knows—maybe this will be one of your documents!

AP World History

For this exam, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time . As for the other two history exams, the College Board has provided practice questions . See page 166 for the DBQ.

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2017 World History DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History and AP European History exams. So be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board . (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

Finding a Trusted Advisor to Look at Your Papers

A history teacher would be a great resource, but if they are not available to you in this capacity, here are some other ideas:

- An English teacher.

- Ask a librarian at your school or public library! If they can't help you, they may be able to direct you to resources who can.

- You could also ask a school guidance counselor to direct you to in-school resources you could use.

- A tutor. This is especially helpful if they are familiar with the test, although even if they aren't, they can still advise—the DBQ is mostly testing academic writing skills under pressure.

- Your parent(s)! Again, ideally your trusted advisor will be familiar with the AP, but if you have used your parents for writing help in the past they can also assist here.

- You might try an older friend who has already taken the exam and did well...although bear in mind that some people are better at doing than scoring and/or explaining!

Can I Prepare For My Baseline?

If you know nothing about the DBQ and you'd like to do a little basic familiarization before you establish your baseline, that's completely fine. There's no point in taking a practice exam if you are going to panic and muddle your way through it; it won't give a useful picture of your skills.

For a basic orientation, check out my article for a basic introduction to the DBQ including DBQ format.

If you want to look at one or two sample essays, see my article for a list of DBQ example essay resources . Keep in mind that you should use a fresh prompt you haven't seen to establish your baseline, though, so if you do look at samples don't use those prompts to set your baseline.

I would also check out this page about the various "task" words associated with AP essay questions . This page was created primarily for the AP European History Long Essay question, but the definitions are still useful for the DBQ on all the history exams, particularly since these are the definitions provided by the College Board.

Once you feel oriented, take your practice exam!

Don't worry if you don't do well on your first practice! That's what studying is for. The point of establishing a baseline is not to make you feel bad, but to empower you to focus your efforts on the areas you need to work on. Even if you need to work on all the areas, that is completely fine and doable! Every skill you need for the DBQ can be built .

In the following section, we'll go over these skills and how to build them for each exam.

You need a stronger foundation than this sand castle.

#2: Develop Foundational Skills

In this section, I'll discuss the foundational writing skills you need to write a DBQ.

I'll start with some general information on crafting an effective thesis , since this is a skill you will need for any DBQ exam (and for your entire academic life). Then, I'll go over outlining essays, with some sample outline ideas for the DBQ. After I'll touch on time management. Finally, I'll briefly discuss how to non-awkwardly integrate information from your documents into your writing.

It sounds like a lot, but not only are these skills vital to your academic career in general, you probably already have the basic building blocks to master them in your arsenal!

Writing An Effective Thesis

Writing a good thesis is a skill you will need to develop for all your DBQs, and for any essay you write, on the AP or otherwise.

Here are some general rules as to what makes a good thesis:

A good thesis does more than just restate the prompt.

Let's say our class prompt is: "Analyze the primary factors that led to the French Revolution."

Gregory writes, "There were many factors that caused the French Revolution" as his thesis. This is not an effective thesis. All it does is vaguely restate the prompt.

A good thesis makes a plausible claim that you can defend in an essay-length piece of writing.

Maybe Karen writes, "Marie Antoinette caused the French Revolution when she said ‘Let them eat cake' because it made people mad."

This is not an effective thesis, either. For one thing, Marie Antoinette never said that. More importantly, how are you going to write an entire essay on how one offhand comment by Marie Antoinette caused the entire Revolution? This is both implausible and overly simplistic.

A good thesis answers the question .

If LaToya writes, "The Reign of Terror led to the ultimate demise of the French Revolution and ultimately paved the way for Napoleon Bonaparte to seize control of France," she may be making a reasonable, defensible claim, but it doesn't answer the question, which is not about what happened after the Revolution, but what caused it!

A good thesis makes it clear where you are going in your essay.

Let's say Juan writes, "The French Revolution, while caused by a variety of political, social, and economic factors, was primarily incited by the emergence of the highly educated Bourgeois class." This thesis provides a mini-roadmap for the entire essay, laying out that Juan is going to discuss the political, social, and economic factors that led to the Revolution, in that order, and that he will argue that the members of the Bourgeois class were the ultimate inciters of the Revolution.

This is a great thesis! It answers the question, makes an overarching point, and provides a clear idea of what the writer is going to discuss in the essay.

To review: a good thesis makes a claim, responds to the prompt, and lays out what you will discuss in your essay.

If you feel like you have trouble telling the difference between a good thesis and a not-so-good one, here are a few resources you can consult:

This site from SUNY Empire has an exercise in choosing the best thesis from several options. It's meant for research papers, but the general rules as to what makes a good thesis apply.

About.com has another exercise in choosing thesis statements specifically for short essays. Note, however, that most of the correct answers here would be "good" thesis statements as opposed to "super" thesis statements.

- This guide from the University of Iowa provides some really helpful tips on writing a thesis for a history paper.

So how do you practice your thesis statement skills for the DBQ?

While you should definitely practice looking at DBQ questions and documents and writing a thesis in response to those, you may also find it useful to write some practice thesis statements in response to the Free-Response Questions. While you won't be taking any documents into account in your argument for the Free-Response Questions, it's good practice on how to construct an effective thesis in general.

You could even try writing multiple thesis statements in response to the same prompt! It is a great exercise to see how you could approach the prompt from different angles. Time yourself for 5-10 minutes to mimic the time pressure of the AP exam.

If possible, have a trusted advisor or friend look over your practice statements and give you feedback. Barring that, looking over the scoring guidelines for old prompts (accessible from the same page on the College Board where past free-response questions can be found) will provide you with useful tips on what might make a good thesis in response to a given prompt.

Once you can write a thesis, you need to be able to support it—that's where outlining comes in!

This is not a good outline.

Outlining and Formatting Your Essay

You may be the greatest document analyst and thesis-writer in the world, but if you don't know how to put it all together in a DBQ essay outline, you won't be able to write a cohesive, high-scoring essay on test day.

A good outline will clearly lay out your thesis and how you are going to support that thesis in your body paragraphs. It will keep your writing organized and prevent you from forgetting anything you want to mention!

For some general tips on writing outlines, this page from Roane State has some useful information. While the general principles of outlining an essay hold, the DBQ format is going to have its own unique outlining considerations.To that end, I've provided some brief sample outlines that will help you hit all the important points.

Sample DBQ Outline

- Introduction

- Thesis. The most important part of your intro!

- Body 1 - contextual information

- Any outside historical/contextual information

- Body 2 - First point

- Documents & analysis that support the first point

- If three body paragraphs: use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Body 3 - Second point

- Documents & analysis that support the second point

- Use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Be sure to mention your outside example if you have not done so yet!

- Body 4 (optional) - Third point

- Documents and analysis that support third point

- Re-state thesis

- Draw a comparison to another time period or situation (synthesis)

Depending on your number of body paragraphs and your main points, you may include different numbers of documents in each paragraph, or switch around where you place your contextual information, your outside example, or your synthesis.

There's no one right way to outline, just so long as each of your body paragraphs has a clear point that you support with documents, and you remember to do a deeper analysis on four documents, bring in outside historical information, and make a comparison to another historical situation or time (you will see these last points further explained in the rubric breakdown).

Of course, all the organizational skills in the world won't help you if you can't write your entire essay in the time allotted. The next section will cover time management skills.

You can be as organized as this library!

Time Management Skills for Essay Writing

Do you know all of your essay-writing skills, but just can't get a DBQ essay together in a 15-minute planning period and 40 minutes of writing?

There could be a few things at play here:

Do you find yourself spending a lot of time staring at a blank paper?

If you feel like you don't know where to start, spend one-two minutes brainstorming as soon as you read the question and the documents. Write anything here—don't censor yourself. No one will look at those notes but you!

After you've brainstormed for a bit, try to organize those thoughts into a thesis, and then into body paragraphs. It's better to start working and change things around than to waste time agonizing that you don't know the perfect thing to say.

Are you too anxious to start writing, or does anxiety distract you in the middle of your writing time? Do you just feel overwhelmed?

Sounds like test anxiety. Lots of people have this. (Including me! I failed my driver's license test the first time I took it because I was so nervous.)

You might talk to a guidance counselor about your anxiety. They will be able to provide advice and direct you to resources you can use.

There are also some valuable test anxiety resources online: try our guide to mindfulness (it's focused on the SAT, but the same concepts apply on any high-pressure test) and check out tips from Minnesota State University , these strategies from TeensHealth , or this plan for reducing anxiety from West Virginia University.

Are you only two thirds of the way through your essay when 40 minutes have passed?

You are probably spending too long on your outline, biting off more than you can chew, or both.

If you find yourself spending 20+ minutes outlining, you need to practice bringing down your outline time. Remember, an outline is just a guide for your essay—it is fine to switch things around as you are writing. It doesn't need to be perfect. To cut down on your outline time, practice just outlining for shorter and shorter time intervals. When you can write one in 20 minutes, bring it down to 18, then down to 16.

You may also be trying to cover too much in your paper. If you have five body paragraphs, you need to scale things back to three. If you are spending twenty minutes writing two paragraphs of contextual information, you need to trim it down to a few relevant sentences. Be mindful of where you are spending a lot of time, and target those areas.

You don't know the problem —you just can't get it done!

If you can't exactly pinpoint what's taking you so long, I advise you to simply practice writing DBQs in less and less time. Start with 20 minutes for your outline and 50 for your essay, (or longer, if you need). Then when you can do it in 20 and 50, move back to 18 minutes and 45 for writing, then to 15 and 40.

You absolutely can learn to manage your time effectively so that you can write a great DBQ in the time allotted. On to the next skill!

Integrating Citations

The final skill that isn't explicitly covered in the rubric, but will make a big difference in your essay quality, is integrating document citations into your essay. In other words, how do you reference the information in the documents in a clear, non-awkward way?

It is usually better to use the author or title of the document to identify a document instead of writing "Document A." So instead of writing "Document A describes the riot as...," you might say, "In Sven Svenson's description of the riot…"

When you quote a document directly without otherwise identifying it, you may want to include a parenthetical citation. For example, you might write, "The strikers were described as ‘valiant and true' by the working class citizens of the city (Document E)."

Now that we've reviewed the essential, foundational skills of the DBQ, I'll move into the rubric breakdowns. We'll discuss each skill the AP graders will be looking for when they score your exam. All of the history exams share a DBQ rubric, so the guidelines are identical.

Don't worry, you won't need a magnifying glass to examine the rubric.

#3: Learn the DBQ Rubric

The DBQ rubric has four sections for a total of seven points.

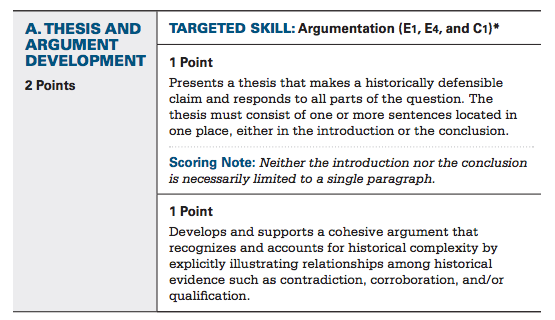

Part A: Thesis - 2 Points

One point is for having a thesis that works and is historically defensible. This just means that your thesis can be reasonably supported by the documents and historical fact. So please don't make the main point of your essay that JFK was a member of the Illuminati or that Pope Urban II was an alien.

Per the College Board, your thesis needs to be located in your introduction or your conclusion. You've probably been taught to place your thesis in your intro, so stick with what you're used to. Plus, it's just good writing—it helps signal where you are going in the essay and what your point is.

You can receive another point for having a super thesis.

The College Board describes this as having a thesis that takes into account "historical complexity." Historical complexity is really just the idea that historical evidence does not always agree about everything, and that there are reasons for agreement, disagreement, etc.

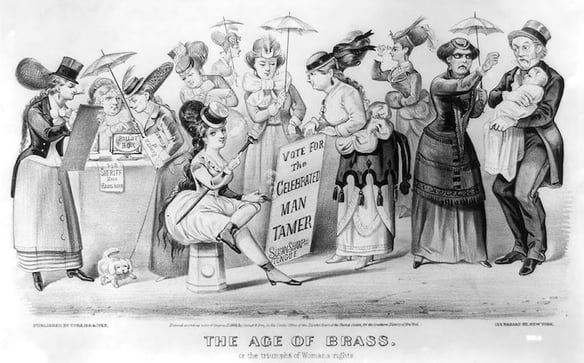

How will you know whether the historical evidence agrees or disagrees? The documents! Suppose you are responding to a prompt about women's suffrage (suffrage is the right to vote, for those of you who haven't gotten to that unit in class yet):

"Analyze the responses to the women's suffrage movement in the United States."

Included among your documents, you have a letter from a suffragette passionately explaining why she feels women should have the vote, a copy of a suffragette's speech at a women's meeting, a letter from one congressman to another debating the pros and cons of suffrage, and a political cartoon displaying the death of society and the end of the ‘natural' order at the hands of female voters.

A simple but effective thesis might be something like,

"Though ultimately successful, the women's suffrage movement sharply divided the country between those who believed women's suffrage was unnatural and those who believed it was an inherent right of women."

This is good: it answers the question and clearly states the two responses to suffrage that are going to be analyzed in the essay.

A super thesis , however, would take the relationships between the documents (and the people behind the documents!) into account.

It might be something like,

"The dramatic contrast between those who responded in favor of women's suffrage and those who fought against it revealed a fundamental rift in American society centered on the role of women—whether women were ‘naturally' meant to be socially and civilly subordinate to men, or whether they were in fact equals."

This is a "super" thesis because it gets into the specifics of the relationship between historical factors and shows the broader picture —that is, what responses to women's suffrage revealed about the role of women in the United States overall.

It goes beyond just analyzing the specific issues to a "so what"? It doesn't just take a position about history, it tells the reader why they should care . In this case, our super thesis tells us that the reader should care about women's suffrage because the issue reveals a fundamental conflict in America over the position of women in society.

Part B: Document Analysis - 2 Points

One point for using six or seven of the documents in your essay to support your argument. Easy-peasy! However, make sure you aren't just summarizing documents in a list, but are tying them back to the main points of your paragraphs.

It's best to avoid writing things like, "Document A says X, and Document B says Y, and Document C says Z." Instead, you might write something like, "The anonymous author of Document C expresses his support and admiration for the suffragettes but also expresses fear that giving women the right to vote will lead to conflict in the home, highlighting the common fear that women's suffrage would lead to upheaval in women's traditional role in society."

Any summarizing should be connected a point. Essentially, any explanation of what a document says needs to be tied to a "so what?" If it's not clear to you why what you are writing about a document is related to your main point, it's not going to be clear to the AP grader.

You can get an additional point here for doing further analysis on 4 of the documents. This further analysis could be in any of these 4 areas:

Author's point of view - Why does the author think the way that they do? What is their position in society and how does this influence what they are saying?

Author's purpose - Why is the author writing what they are writing? What are they trying to convince their audience of?

Historical context - What broader historical facts are relevant to this document?

Audience - Who is the intended audience for this document? Who is the author addressing or trying to convince?

Be sure to tie any further analysis back to your main argument! And remember, you only have to do this for four documents for full credit, but it's fine to do it for more if you can.

Practicing Document Analysis

So how do you practice document analysis? By analyzing documents!

Luckily for AP test takers everywhere, New York State has an exam called the Regents Exam that has its own DBQ section. Before they write the essay, however, New York students have to answer short answer questions about the documents.

Answering Regents exam DBQ short-answer questions is good practice for basic document analysis. While most of the questions are pretty basic, it's a good warm-up in terms of thinking more deeply about the documents and how to use them. This set of Regent-style DBQs from the Teacher's Project are mostly about US History, but the practice could be good for other tests too.

This prompt from the Morningside center also has some good document comprehensions questions about a US-History based prompt.

Note: While the document short-answer questions are useful for thinking about basic document analysis, I wouldn't advise completing entire Regents exam DBQ essay prompts for practice, because the format and rubric are both somewhat different from the AP.

Your AP history textbook may also have documents with questions that you can use to practice. Flip around in there!

This otter is ready to swim in the waters of the DBQ.

When you want to do a deeper dive on the documents, you can also pull out those old College Board DBQ prompts.

Read the documents carefully. Write down everything that comes to your attention. Do further analysis—author's point of view, purpose, audience, and historical context—on all the documents for practice, even though you will only need to do additional analysis on four on test day. Of course, you might not be able to do all kinds of further analysis on things like maps and graphs, which is fine.

You might also try thinking about how you would arrange those observations in an argument, or even try writing a practice outline! This exercise would combine your thesis and document-analysis skills practice.

When you've analyzed everything you can possibly think of for all the documents, pull up the Scoring Guide for that prompt. It helpfully has an entire list of analysis points for each document.

Consider what they identified that you missed.

Do you seem way off-base in your interpretation? If so, how did it happen?

Part C: Using Evidence Beyond the Documents - 2 Points

Don't be freaked out by the fact that this is two points!

One point is just for context—if you can locate the issue within its broader historical situation. You do need to write several sentences to a paragraph about it, but don't stress; all you really need to know to be able to get this point is information about major historical trends over time, and you will need to know this anyways for the multiple choice section. If the question is about the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, for example, be sure to include some of the general information you know about the Great Depression! Boom. Contextualized.

The other point is for naming a specific, relevant example in your essay that does not appear in the documents.

To practice your outside information skills, pull up your College Board prompts!

Read through the prompt and documents and then write down all of the contextualizing facts and as many specific examples as you can think of.

I advise timing yourself—maybe 5-10 minutes to read the documents and prompt and list your outside knowledge—to imitate the time pressure of the DBQ.

When you've exhausted your knowledge, make sure to fact-check your examples and your contextual information! You don't want to use incorrect information on test day.

If you can't remember any examples or contextual information about that topic, look some up! This will help fill in holes in your knowledge.

Part D: Synthesis - 1 Point

All you need to do for synthesis is relate your argument about this specific time period to a different time period, geographical area, historical movement, etc. It is probably easiest to do this in the conclusion of the essay. If your essay is about the Great Depression, you might relate it to the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

You do need to do more than just mention your synthesis connection. You need to make it meaningful. How are the two things you are comparing similar? What does one reveal about the other? Is there a key difference that highlights something important?

To practice your synthesis skills—you guessed it—pull up your College Board prompts!

- Read through the prompt and documents and then identify what historical connections you could make for your synthesis point. Be sure to write a few words on why the connection is significant!

- A great way to make sure that your synthesis connection makes sense is to explain it to someone else. If you explain what you think the connection is and they get it, you're probably on the right track.

- You can also look at sample responses and the scoring guide for the old prompts to see what other connections students and AP graders made.

That's a wrap on the rubric! Let's move on to skill-building strategy.

I know you're tired, but you can do it!

#5: Take Another Practice DBQ

So, you established a baseline, identified the skills you need to work on, and practiced writing a thesis statement and analyzing documents for hours. What now?

Take another timed, practice DBQ from a prompt you haven't seen before to check how you've improved. Recruit your same trusted advisor to grade your exam and give feedback. After, work on any skills that still need to be honed.

Repeat this process as necessary, until you are consistently scoring your goal score. Then you just need to make sure you maintain your skills until test day by doing an occasional practice DBQ.

Eventually, test day will come—read on for my DBQ-test-taking tips.

How Can I Succeed On DBQ Test Day?

Once you've prepped your brains out, you still have to take the test! I know, I know. But I've got some advice on how to make sure all of your hard work pays off on test day—both some general tips and some specific advice on how to write a DBQ.

#1: General Test-Taking Tips

Most of these are probably tips you've heard before, but they bear repeating:

Get a good night's sleep for the two nights preceding the exam. This will keep your memory sharp!

Eat a good breakfast (and lunch, if the exam is in the afternoon) before the exam with protein and whole grains. This will keep your blood sugar from crashing and making you tired during the exam.

Don't study the night before the exam if you can help it. Instead, do something relaxing. You've been preparing, and you will have an easier time on exam day if you aren't stressed from trying to cram the night before.

This dude knows he needs to get a good night's rest!

#2: DBQ Plan and Strategies

Below I've laid out how to use your time during the DBQ exam. I'll provide tips on reading the question and docs, planning your essay, and writing!

Be sure to keep an eye on the clock throughout so you can track your general progress.

Reading the Question and the Documents: 5-6 min

First thing's first: r ead the question carefully , two or even three times. You may want to circle the task words ("analyze," "describe," "evaluate," "compare") to make sure they stand out.

You could also quickly jot down some contextual information you already know before moving on to the documents, but if you can't remember any right then, move on to the docs and let them jog your memory.

It's fine to have a general idea of a thesis after you read the question, but if you don't, move on to the docs and let them guide you in the right direction.

Next, move on to the documents. Mark them as you read—circle things that seem important, jot thoughts and notes in the margins.

After you've passed over the documents once, you should choose the four documents you are going to analyze more deeply and read them again. You probably won't be analyzing the author's purpose for sources like maps and charts. Good choices are documents in which the author's social or political position and stake in the issue at hand are clear.

Get ready to go down the document rabbit hole.

Planning Your Essay: 9-11 min

Once you've read the question and you have preliminary notes on the documents, it's time to start working on a thesis. If you still aren't sure what to talk about, spend a minute or so brainstorming. Write down themes and concepts that seem important and create a thesis from those. Remember, your thesis needs to answer the question and make a claim!

When you've got a thesis, it's time to work on an outline . Once you've got some appropriate topics for your body paragraphs, use your notes on the documents to populate your outline. Which documents support which ideas? You don't need to use every little thought you had about the document when you read it, but you should be sure to use every document.

Here's three things to make sure of:

Make sure your outline notes where you are going to include your contextual information (often placed in the first body paragraph, but this is up to you), your specific example (likely in one of the body paragraphs), and your synthesis (the conclusion is a good place for this).

Make sure you've also integrated the four documents you are going to further analyze and how to analyze them.

Make sure you use all the documents! I can't stress this enough. Take a quick pass over your outline and the docs and make sure all of the docs appear in your outline.

If you go over the planning time a couple of minutes, it's not the end of the world. This probably just means you have a really thorough outline! But be ready to write pretty fast.

Writing the Essay - 45 min

If you have a good outline, the hard part is out of the way! You just need to make sure you get all of your great ideas down in the test booklet.

Don't get too bogged down in writing a super-exciting introduction. You won't get points for it, so trying to be fancy will just waste time. Spend maybe one or two sentences introducing the issue, then get right to your thesis.

For your body paragraphs, make sure your topic sentences clearly state the point of the paragraph . Then you can get right into your evidence and your document analysis.

As you write, make sure to keep an eye on the time. You want to be a little more than halfway through at the 20-minute mark of the writing period, so you have a couple minutes to go back and edit your essay at the end.

Keep in mind that it's more important to clearly lay out your argument than to use flowery language. Sentences that are shorter and to the point are completely fine.

If you are short on time, the conclusion is the least important part of your essay . Even just one sentence to wrap things up is fine just so long as you've hit all the points you need to (i.e. don't skip your conclusion if you still need to put in your synthesis example).

When you are done, make one last past through your essay. Make sure you included everything that was in your outline and hit all the rubric skills! Then take a deep breath and pat yourself on the back.

You did it!! Have a cupcake to celebrate.

Key Tips for How to Write a DBQ

I realize I've bombarded you with information, so here are the key points to take away:

Remember the drill for prep: establish a baseline, build skills, take another practice DBQ, repeat skill-building as necessary.

Make sure that you know the rubric inside and out so you will remember to hit all the necessary points on test day! It's easy to lose points just for forgetting something like your synthesis point.

On test day, keep yourself on track time-wise !

This may seem like a lot, but you can learn how to ace your DBQ! With a combination of preparation and good test-taking strategy, you will get the score you're aiming for. The more you practice, the more natural it will seem, until every DBQ is a breeze.

What's Next?

If you want more information about the DBQ, see my introductory guide to the DBQ .

Haven't registered for your AP test yet? See our article for help registering for AP exams .

For more on studying for the AP US History exam, check out the best AP US History notes to study with .

Studying for World History? See these AP World History study tips from one of our experts.

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

How To Write a Good History Essay

The former editor of History Review Robert Pearce gives his personal view.

First of all we ought to ask, What constitutes a good history essay? Probably no two people will completely agree, if only for the very good reason that quality is in the eye – and reflects the intellectual state – of the reader. What follows, therefore, skips philosophical issues and instead offers practical advice on how to write an essay that will get top marks.