Ratio Analysis and Equity Valuation: From Research to Practice

- Published: March 2001

- Volume 6 , pages 109–154, ( 2001 )

Cite this article

- Doron Nissim 1 &

- Stephen H. Penman 2

13k Accesses

441 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Financial statement analysis has traditionally been seen as part of thefundamental analysis required for equity valuation. But the analysis has typicallybeen ad hoc. Drawing on recent research on accounting-based valuation, this paperoutlines a financial statement analysis for use in equity valuation. Standardprofitability analysis is incorporated, and extended, and is complemented with ananalysis of growth. An analysis of operating activities is distinguished from theanalysis of financing activities. The perspective is one of forecasting payoffs to equities. So financial statement analysis is presented as a matter of pro formaanalysis of the future, with forecasted ratios viewed as building blocks offorecasts of payoffs. The analysis of current financial statements is then seen asa matter of identifying current ratios as predictors of the future ratios thatdetermine equity payoffs. The financial statement analysis is hierarchical, withratios lower in the ordering identified as finer information about those higher up.To provide historical benchmarks for forecasting, typical values for ratios aredocumented for the period 1963–1999, along with their cross-sectionalvariation and correlation. And, again with a view to forecasting, the time seriesbehavior of many of the ratios is also described and their typical “long-run,steady-state” levels are documented.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Financial sustainability: measurement and empirical evidence

Werner Gleißner, Thomas Günther & Christian Walkshäusl

Diversification and portfolio theory: a review

Gilles Boevi Koumou

ESG Disclosure and Idiosyncratic Risk in Initial Public Offerings

Beat Reber, Agnes Gold & Stefan Gold

Abarbanell, J. S., and V. L. Bernard. (2000). “Is the U.S. Stock Market Myopic?” Journal of Accounting Research 38, 221-243.

Google Scholar

Beaver, W. H., and S. G. Ryan. (2000). “Biases and Lags in Book Value and their Effects on the Ability of the Book-to-Market Ratio to Predict Book Return on Equity.” Journal of Accounting Research 38, 127-148.

Brief, R. P., and R. A. Lawson. (1992). “The Role of the Accounting Rate of Return in Financial Statement Analysis.” The Accounting Review 67, 411-426.

Brown, L. D. (1993). “Earnings Forecasting Research: Its Implications for Capital Markets Research.” International Journal of Forecasting 9, 295-320.

Brown, S. J., W. N. Goetzmann, and S. A. Ross. (1995). “Survival.” Journal of Finance 50, 853-873.

Claus, J. J., and J. K. Thomas. (2001). “Equity Premium as Low as Three Percent? Evidence from Analysists' Earnings Forecasts for Domestic and International Stocks” Journal of Finance . Forthcoming.

Colander, D. (1992). “Retrospectives: The Lost Art of Economics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 6, 191-198.

Edwards, E. O., and P. W. Bell. (1961). The Theory and Measurement of Business Income . Berkeley, CA: The University of California Press.

Fairfield, P. M., R. J. Sweeney, and T. L. Yohn. (1996). “Accounting Classification and the Predictive Content of Earnings.” The Accounting Review 71, 337-355.

Fama E. F., and K. R. French. (2000). “Forecasting Profitability and Earnings.” Journal of Business 73.

Feltham, G. A., and J. A. Ohlson. (1995). “Valuation and Clean Surplus Accounting for Operating and Financial Activities.” Contemporary Accounting Research 11, 689-731.

Francis, J., P. Olsson, and D. R. Oswald. (2000). “Comparing the Accuracy and Explainability of Dividend, Free Cash Flow, and Abnormal Earnings Equity Value Estimates.” Journal of Accounting Research 38, 45-70.

Frankel, R., and C. M. C. Lee. (1998). “Accounting Valuation, Market Expectation and Cross-Sectional Stock Returns.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 25, 283-319.

Freeman, R. N., J. A. Ohlson, and S. H. Penman. (1982). “Book Rate-of-Return and Prediction of Earnings Changes: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Accounting Research 20, 639-653.

Gebhardt, W. R., C. M. C. Lee, and B. Swaminathan. (2000). “Toward an Implied Cost of Capital.” Journal of Accounting Research, Forthcoming.

Graham, B., D. L. Dodd, and S. Cottle. (1962). Security Analysis. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.

Ibbotson, R., and R. Sinquefield. (1983). Stocks, bonds, bills and inflation . 1926-1982, Charlottesville, VA: Financial Analyst Research Foundation.

Johansson, S. (1998). The Profitability, Financing, and Growth of the Firm: Goals, Relationships and Measurement Methods . Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Kay, J. A. (1976). “Accountants, too, Could be Happy in a Golden Age: The Accountants Rate of Profit and the Internal Rate of Return.” Oxford Economic Papers 17, 447-460.

Lee C. M. C., J. Myers, and B. Swaminathan. (1999). “What Is the Intrinsic Value of the Dow?” Journal of Finance 54, 1693-1741.

Lev, B., and S. R. Thiagarajan. (1993). “Fundamental Information Analysis.” Journal of Accounting Research 31, 190-215.

Lipe, R. C. (1986). “The Information Contained in the Components of Earnings.” Journal of Accounting Research 24, 37-64.

Myers, J. N. (1999). “Conservative Accounting and Finite Firm Life: Why Residual Income Valuation Estimates Understate Stock Price.” Working Paper, University of Washington.

Ohlson, J. A. (1995). “Earnings, Book Values, and Dividends in Equity Valuation.” Contemporary Accounting Research 11, 661-687.

Ohlson J. A., and X. J. Zhang. (1999). “On the Theory of the Forecast-Horizon in Equity Valuation.” Journal of Accounting Research 37, 437-449.

O'Hanlon J., and A. Steele. (1998). “Estimating the Equity Risk Premium Using Accounting Fundamentals.” Working Paper, Lancaster University.

Ou, J. A. (1990). “The Information Content of Nonearnings Accounting Numbers as Earnings Predictors.” Journal of Accounting Research 28, 144-163.

Ou, J. A., and S. H. Penman. (1989). “Financial Statement Analysis and the Prediction of Stock Returns.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 11, 295-329.

Ou, J. A., and S. H. Penman. (1995). “Financial Statement Analysis and the Evaluation of Market-to-Book Ratios.” Working Paper, University of California at Berkeley.

Penman, S. H. (1996). “The Articulation of Price-Earnings Ratios and Market-to-Book Ratios and the Evaluation of Growth.” Journal of Accounting Research 34, 235-259.

Penman, S. H. (1991). “An Evaluation of Accounting Rate-of-Return.” Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance 6, 233-255.

Penman S. H. (1997). “A Synthesis of Equity Valuation Techniques and the Terminal Value Calculation of the Dividend Discount Model.” Review of Accounting Studies 2, 303-323.

Penman S. H., and T. Sougiannis. (1998). “A Comparison of Dividend, Cash Flow, and Earnings Approaches to Equity Valuation.” Contemporary Accounting Research 15, 343-383.

Preinreich, G. (1938). “Annual Survey of Economic Theory: The Theory of Depreciation.” Econometrica, 219-241.

Selling, T. I., and C. P. Stickney. (1989). “The Effects of Business Environments and Strategy on a Firm's Rate of Return on Assets.” Financial Analysts Journal , 43-52.

Zhang, X. (2000). “Conservative Accounting and Earnings Valuation.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 29, 125-149.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate School of Business, Columbia University, 3022 Broadway, Uris Hall 604, New York, NY, 10027

Doron Nissim

Graduate School of Business, Columbia University, 3022 Broadway, Uris Hall 612, New York, NY, 10027

Stephen H. Penman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nissim, D., Penman, S.H. Ratio Analysis and Equity Valuation: From Research to Practice. Review of Accounting Studies 6 , 109–154 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011338221623

Download citation

Issue Date : March 2001

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011338221623

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Financial statement analysis

- ratio analysis

- equity valuation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Ratio Analysis?

- What Does It Tell You?

- Application

The Bottom Line

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Ratios

Financial Ratio Analysis: Definition, Types, Examples, and How to Use

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/andrew_bloomenthal_bio_photo-5bfc262ec9e77c005199a327.png)

Ratio analysis is a quantitative method of gaining insight into a company's liquidity, operational efficiency, and profitability by studying its financial statements such as the balance sheet and income statement. Ratio analysis is a cornerstone of fundamental equity analysis .

Key Takeaways

- Ratio analysis compares line-item data from a company's financial statements to reveal insights regarding profitability, liquidity, operational efficiency, and solvency.

- Ratio analysis can mark how a company is performing over time, while comparing a company to another within the same industry or sector.

- Ratio analysis may also be required by external parties that set benchmarks often tied to risk.

- While ratios offer useful insight into a company, they should be paired with other metrics, to obtain a broader picture of a company's financial health.

- Examples of ratio analysis include current ratio, gross profit margin ratio, inventory turnover ratio.

Investopedia / Theresa Chiechi

What Does Ratio Analysis Tell You?

Investors and analysts employ ratio analysis to evaluate the financial health of companies by scrutinizing past and current financial statements. Comparative data can demonstrate how a company is performing over time and can be used to estimate likely future performance. This data can also compare a company's financial standing with industry averages while measuring how a company stacks up against others within the same sector.

Investors can use ratio analysis easily, and every figure needed to calculate the ratios is found on a company's financial statements.

Ratios are comparison points for companies. They evaluate stocks within an industry. Likewise, they measure a company today against its historical numbers. In most cases, it is also important to understand the variables driving ratios as management has the flexibility to, at times, alter its strategy to make it's stock and company ratios more attractive. Generally, ratios are typically not used in isolation but rather in combination with other ratios. Having a good idea of the ratios in each of the four previously mentioned categories will give you a comprehensive view of the company from different angles and help you spot potential red flags.

A ratio is the relation between two amounts showing the number of times one value contains or is contained within the other.

Types of Ratio Analysis

The various kinds of financial ratios available may be broadly grouped into the following six silos, based on the sets of data they provide:

1. Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company's ability to pay off its short-term debts as they become due, using the company's current or quick assets. Liquidity ratios include the current ratio, quick ratio, and working capital ratio.

2. Solvency Ratios

Also called financial leverage ratios, solvency ratios compare a company's debt levels with its assets, equity, and earnings, to evaluate the likelihood of a company staying afloat over the long haul, by paying off its long-term debt as well as the interest on its debt. Examples of solvency ratios include: debt-equity ratios, debt-assets ratios, and interest coverage ratios.

3. Profitability Ratios

These ratios convey how well a company can generate profits from its operations. Profit margin, return on assets, return on equity, return on capital employed, and gross margin ratios are all examples of profitability ratios .

4. Efficiency Ratios

Also called activity ratios, efficiency ratios evaluate how efficiently a company uses its assets and liabilities to generate sales and maximize profits. Key efficiency ratios include: turnover ratio, inventory turnover, and days' sales in inventory.

5. Coverage Ratios

Coverage ratios measure a company's ability to make the interest payments and other obligations associated with its debts. Examples include the times interest earned ratio and the debt-service coverage ratio .

6. Market Prospect Ratios

These are the most commonly used ratios in fundamental analysis. They include dividend yield , P/E ratio , earnings per share (EPS), and dividend payout ratio . Investors use these metrics to predict earnings and future performance.

For example, if the average P/E ratio of all companies in the S&P 500 index is 20, and the majority of companies have P/Es between 15 and 25, a stock with a P/E ratio of seven would be considered undervalued. In contrast, one with a P/E ratio of 50 would be considered overvalued. The former may trend upwards in the future, while the latter may trend downwards until each aligns with its intrinsic value.

Most ratio analysis is only used for internal decision making. Though some benchmarks are set externally (discussed below), ratio analysis is often not a required aspect of budgeting or planning.

Application of Ratio Analysis

The fundamental basis of ratio analysis is to compare multiple figures and derive a calculated value. By itself, that value may hold little to no value. Instead, ratio analysis must often be applied to a comparable to determine whether or a company's financial health is strong, weak, improving, or deteriorating.

Ratio Analysis Over Time

A company can perform ratio analysis over time to get a better understanding of the trajectory of its company. Instead of being focused on where it is today, the company is more interested n how the company has performed over time, what changes have worked, and what risks still exist looking to the future. Performing ratio analysis is a central part in forming long-term decisions and strategic planning .

To perform ratio analysis over time, a company selects a single financial ratio, then calculates that ratio on a fixed cadence (i.e. calculating its quick ratio every month). Be mindful of seasonality and how temporarily fluctuations in account balances may impact month-over-month ratio calculations. Then, a company analyzes how the ratio has changed over time (whether it is improving, the rate at which it is changing, and whether the company wanted the ratio to change over time).

Ratio Analysis Across Companies

Imagine a company with a 10% gross profit margin. A company may be thrilled with this financial ratio until it learns that every competitor is achieving a gross profit margin of 25%. Ratio analysis is incredibly useful for a company to better stand how its performance compares to similar companies.

To correctly implement ratio analysis to compare different companies, consider only analyzing similar companies within the same industry . In addition, be mindful how different capital structures and company sizes may impact a company's ability to be efficient. In addition, consider how companies with varying product lines (i.e. some technology companies may offer products as well as services, two different product lines with varying impacts to ratio analysis).

Different industries simply have different ratio expectations. A debt-equity ratio that might be normal for a utility company that can obtain low-cost debt might be deemed unsustainably high for a technology company that relies more heavily on private investor funding.

Ratio Analysis Against Benchmarks

Companies may set internal targets for their financial ratios. These calculations may hold current levels steady or strive for operational growth. For example, a company's existing current ratio may be 1.1; if the company wants to become more liquid, it may set the internal target of having a current ratio of 1.2 by the end of the fiscal year.

Benchmarks are also frequently implemented by external parties such lenders. Lending institutions often set requirements for financial health as part of covenants in loan documents. Covenants form part of the loan's terms and conditions and companies must maintain certain metrics or the loan may be recalled.

If these benchmarks are not met, an entire loan may be callable or a company may be faced with an adjusted higher rate of interest to compensation for this risk. An example of a benchmark set by a lender is often the debt service coverage ratio which measures a company's cash flow against it's debt balances.

Examples of Ratio Analysis in Use

Ratio analysis can predict a company's future performance — for better or worse. Successful companies generally boast solid ratios in all areas, where any sudden hint of weakness in one area may spark a significant stock sell-off. Let's look at a few simple examples

Net profit margin , often referred to simply as profit margin or the bottom line, is a ratio that investors use to compare the profitability of companies within the same sector. It's calculated by dividing a company's net income by its revenues. Instead of dissecting financial statements to compare how profitable companies are, an investor can use this ratio instead. For example, suppose company ABC and company DEF are in the same sector with profit margins of 50% and 10%, respectively. An investor can easily compare the two companies and conclude that ABC converted 50% of its revenues into profits, while DEF only converted 10%.

Using the companies from the above example, suppose ABC has a P/E ratio of 100, while DEF has a P/E ratio of 10. An average investor concludes that investors are willing to pay $100 per $1 of earnings ABC generates and only $10 per $1 of earnings DEF generates.

What Are the Types of Ratio Analysis?

Financial ratio analysis is often broken into six different types: profitability, solvency, liquidity, turnover, coverage, and market prospects ratios. Other non-financial metrics may be scattered across various departments and industries. For example, a marketing department may use a conversion click ratio to analyze customer capture.

What Are the Uses of Ratio Analysis?

Ratio analysis serves three main uses. First, ratio analysis can be performed to track changes to a company over time to better understand the trajectory of operations. Second, ratio analysis can be performed to compare results with other similar companies to see how the company is doing compared to competitors. Third, ratio analysis can be performed to strive for specific internally-set or externally-set benchmarks.

Why Is Ratio Analysis Important?

Ratio analysis is important because it may portray a more accurate representation of the state of operations for a company. Consider a company that made $1 billion of revenue last quarter. Though this seems ideal, the company might have had a negative gross profit margin, a decrease in liquidity ratio metrics, and lower earnings compared to equity than in prior periods. Static numbers on their own may not fully explain how a company is performing.

What Is an Example of Ratio Analysis?

Consider the inventory turnover ratio that measures how quickly a company converts inventory to a sale. A company can track its inventory turnover over a full calendar year to see how quickly it converted goods to cash each month. Then, a company can explore the reasons certain months lagged or why certain months exceeded expectations.

There is often an overwhelming amount of data and information useful for a company to make decisions. To make better use of their information, a company may compare several numbers together. This process called ratio analysis allows a company to gain better insights to how it is performing over time, against competition, and against internal goals. Ratio analysis is usually rooted heavily with financial metrics, though ratio analysis can be performed with non-financial data.

- Valuing a Company: Business Valuation Defined With 6 Methods 1 of 37

- What Is Valuation? 2 of 37

- Valuation Analysis: Meaning, Examples and Use Cases 3 of 37

- Financial Statements: List of Types and How to Read Them 4 of 37

- Balance Sheet: Explanation, Components, and Examples 5 of 37

- Cash Flow Statement: How to Read and Understand It 6 of 37

- 6 Basic Financial Ratios and What They Reveal 7 of 37

- 5 Must-Have Metrics for Value Investors 8 of 37

- Earnings Per Share (EPS): What It Means and How to Calculate It 9 of 37

- P/E Ratio Definition: Price-to-Earnings Ratio Formula and Examples 10 of 37

- Price-to-Book (PB) Ratio: Meaning, Formula, and Example 11 of 37

- Price/Earnings-to-Growth (PEG) Ratio: What It Is and the Formula 12 of 37

- Fundamental Analysis: Principles, Types, and How to Use It 13 of 37

- Absolute Value: Definition, Calculation Methods, Example 14 of 37

- Relative Valuation Model: Definition, Steps, and Types of Models 15 of 37

- Intrinsic Value of a Stock: What It Is and Formulas to Calculate It 16 of 37

- Intrinsic Value vs. Current Market Value: What's the Difference? 17 of 37

- The Comparables Approach to Equity Valuation 18 of 37

- The 4 Basic Elements of Stock Value 19 of 37

- How to Become Your Own Stock Analyst 20 of 37

- Due Diligence in 10 Easy Steps 21 of 37

- Determining the Value of a Preferred Stock 22 of 37

- Qualitative Analysis 23 of 37

- How to Choose the Best Stock Valuation Method 24 of 37

- Bottom-Up Investing: Definition, Example, Vs. Top-Down 25 of 37

- Financial Ratio Analysis: Definition, Types, Examples, and How to Use 26 of 37

- What Book Value Means to Investors 27 of 37

- Liquidation Value: Definition, What's Excluded, and Example 28 of 37

- Market Capitalization: What It Means for Investors 29 of 37

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Explained With Formula and Examples 30 of 37

- Enterprise Value (EV) Formula and What It Means 31 of 37

- How to Use Enterprise Value to Compare Companies 32 of 37

- How to Analyze Corporate Profit Margins 33 of 37

- Return on Equity (ROE) Calculation and What It Means 34 of 37

- Decoding DuPont Analysis 35 of 37

- How to Value Private Companies 36 of 37

- Valuing Startup Ventures 37 of 37

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/thinkstockphotos_493208894-5bfc2b9746e0fb0051bde2b8.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Financial Ratio Analysis

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Indian Stock Market Follow Following

- Stock Market Analysis Follow Following

- Mba in Finance Follow Following

- Finance Follow Following

- Education Follow Following

- Smuggling Follow Following

- Management Science Follow Following

- Marketing Follow Following

- Project Report on Uco Bank Follow Following

- Supply Chain Management Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Main navigation

- Main content

The Evolution of US Bank Capital around the Implementation of Basel III

- Jan-Peter Siedlarek

Following the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2008, the capital standards for banks operating in the United States were tightened as US banking regulators implemented the Basel III framework. This Economic Commentary briefly presents the key elements of Basel III relevant to bank capital and analyzes the timing of the evolution of regulatory capital ratios for US bank holding companies during that time. It shows that, on average, banks’ capital ratios increased notably between 2009 and 2012, plateauing before the new rules came into force. While larger and better-capitalized banks increased capital ratios soon after the financial crisis, it took smaller and less-well-capitalized banks longer on average to start that process.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

Introduction

Bank capital standards are a key pillar of modern banking regulation. They require banks to operate with a minimum amount of capital relative to the loans, securities, and other assets on their balance sheets. This capital, mostly in the form of shareholder equity, is first in line in case of losses, for example, from loan defaults, and thereby provides a cushion to protect depositors and other debt holders in the bank. Shortfalls in bank capital were seen as a contributing factor to the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the subsequent major recession. In response, regulators across the world sought to tighten regulation following this financial crisis to help prevent future similar crises. These efforts included a tightening of bank capital regulation, requiring banks to hold both more and higher-quality capital, thereby increasing the resilience of the banking system. More recently, following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and other banks in March 2023, bank capital regulation has once again been under scrutiny, and a new reform package modifying capital requirements, known as “Basel III endgame,” has been proposed by US bank regulators. 1

This Economic Commentary presents the evolution of banks’ regulatory capital ratios around the introduction of higher capital requirements that were part of the post-financial crisis Basel III reforms, analyzing the path of capital ratios across groups of different sizes and across the distribution of tier 1 capital ratios both before and after the introduction of this framework. This analysis of capital ratios around an earlier episode of increased capital requirements can be informative for thinking about banks’ possible responses to new capital regulations.

The Tightening of Capital Requirements after 2008 under Basel III

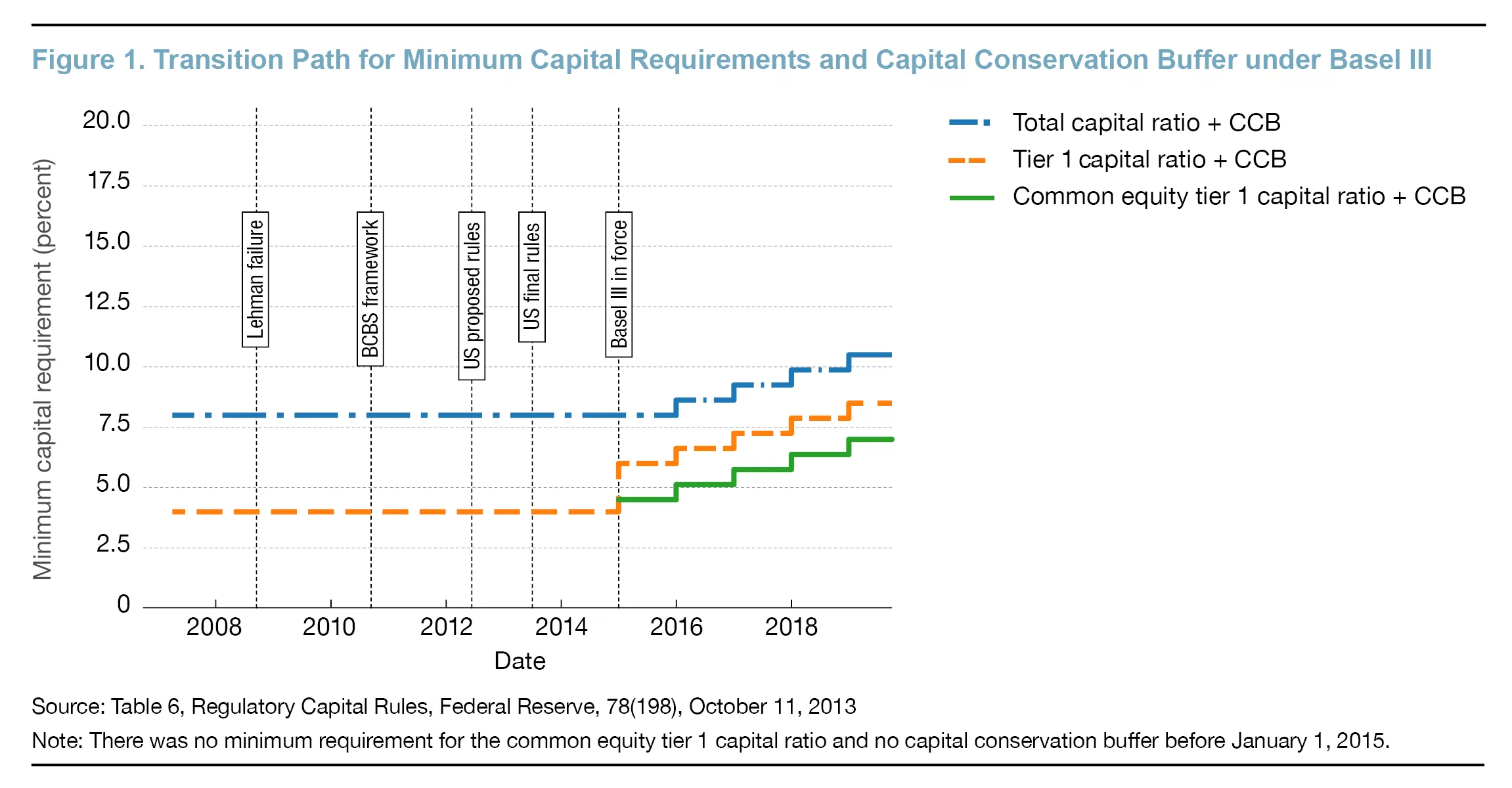

Going into the financial crisis, regulatory capital requirements for banks operating in the United States were based on the Basel II framework published by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in 2004. This framework maintained the two main minimum capital ratios of the earlier Basel I framework, first published by the BCBS in 1988: (1) tier 1 capital to risk weighted assets (RWA) of at least 4 percent, and (2) total capital to RWA of at least 8 percent. 2 Following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the regulatory requirements in Basel I and Basel II were widely regarded by banking regulators as deficient, and there was a concerted international effort to strengthen banking regulation, a process which resulted in the Basel III framework published in September 2010 by the BCBS.

Among other elements of tightening banking regulation, Basel III strengthened minimum capital requirements in several ways. 3 First, it introduced a new, narrower category of capital called “common equity tier 1” (CET1) capital with a minimum CET1 capital-to-RWA ratio requirement of 4.5 percent. CET1 capital presents the highest quality regulatory capital, able to absorb losses as they occur. The CET1 measure comprises mostly common stock and retained earnings and does not include the additional instruments that are permitted under the less strict tier 1 capital measure.

Second, Basel III tightened the minimum tier 1 capital ratio, both narrowing what banks could count toward tier 1 capital relative to previously and increasing the existing minimum tier 1 capital-to-RWA ratio from 4 percent to 6 percent. Third, under Basel III, banks are expected to build up various capital buffers on top of these strict minimums, including the capital conservation buffer (CCB) of 2.5 percent applicable to all banks and an additional surcharge for the “global systemically important banks” (G-SIB), the very largest and systemically important institutions. 4 The new capital buffers on top of the minimum capital requirements are meant to provide an additional layer of protection and act as an early warning mechanism. A failure to meet the required buffer levels leads to restrictions on payouts, such as dividends and bonuses, and thereby helps to keep earnings within the bank.

In the United States, the Basel rules were implemented by the financial sector regulators including the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). A proposed rule was published in June 2012 and, following a comment period, the final rule was released in July 2013. The new regulatory capital minimums became binding for most banks on January 1, 2015, while the additional CCB and G-SIB buffers were phased-in between 2016 and 2019, as shown in Figure 1. 5 In terms of the minimum tier 1 capital ratio, the new rules implied a jump from 4 percent to 6 percent by 2015, increasing for most banks to 8.5 percent including the capital conservation buffer by 2019, with an additional G-SIB surcharge on top for some of the largest banks.

The Basel III implementation was not the only major revision of bank regulation during the time. In parallel, the largest United States banks were also subject to additional new regulations originating in the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010, including compulsory regulatory stress tests for large banks with more than $50 billion in total assets.

Regulatory Capital Ratios of United States Banks Increased Following the Financial Crisis

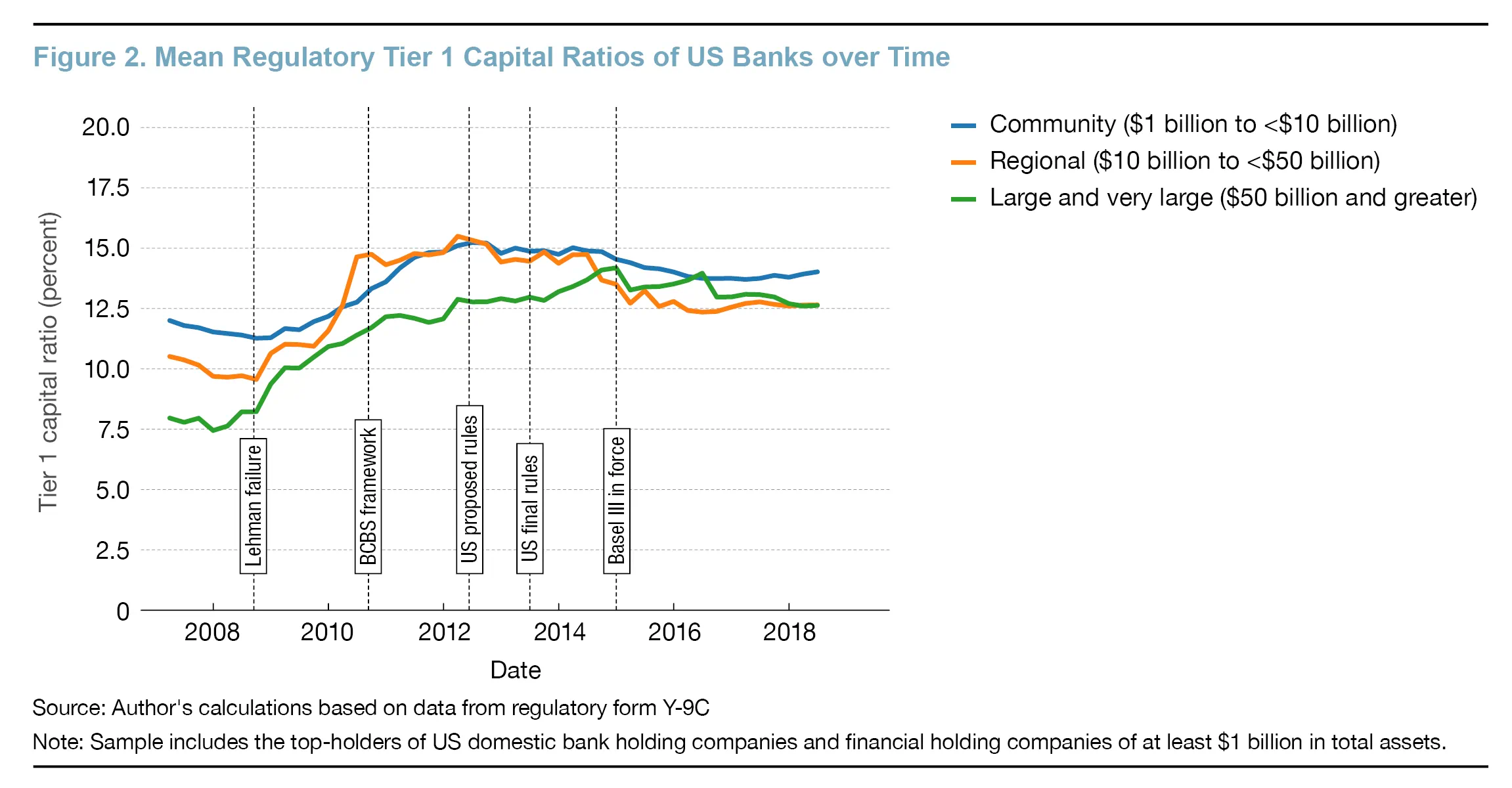

How did United States banks’ capital ratios evolve over this period of changes in capital regulation? Figure 2 shows the mean tier 1 capital ratios from 2007 to 2018 for United States bank holding companies above $1 billion in assets. The data are from Federal Reserve quarterly regulatory filings Consolidated Financial Statements for Holding Companies (Y-9C). The sample covers bank holding companies and financial holding companies operating in the United States with at least $1 billion in total assets. For the analysis, the banks are grouped by balance sheet size as measured by total assets, distinguishing between community banks (less than $10 billion), regional banks ($10 billion to $50 billion), and larger banks (more than $50 billion). 6

The chart highlights two main features of the data that are informative about the way bank capital ratios have evolved around the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and since. First, across all size groups, average capital ratios increased significantly by up to 6 percentage points in the years following the financial crisis, after having declined slowly in the run up to the crisis. Average capital ratios then run approximately flat or even decline slightly from around 2012 onward. The average tier 1 capital ratios that banks reached in 2012 comfortably exceed the minimum required under Basel III from 2015 of 6 percent for all size groups, even including the CCB of 2.5 percent that was set at zero before 2016 and not fully phased-in until 2019.

Second, prior to the financial crisis, the group of large and very large banks on average had lower tier 1 capital ratios than the smaller regional and community banks. Starting in 2008, this gap began to close as the largest banks increased their tier 1 capital/RWA ratios earlier and by more than the smaller banks; and by 2015, the gap had largely disappeared. Note that the banks above $50 billion in assets were subject to the additional requirements under the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010, notably, mandatory regulatory stress tests, that would have provided a strong incentive to increase capital ratios above the minimum required. In addition, some of the very largest banks were also covered by the additional G-SIB surcharge introduced with Basel III. However, both requirements did not apply to the two groups of banks below $50 billion, groups which nonetheless increased their tier 1 capital ratios significantly and well above the new minimum tier 1 ratio required by Basel III.

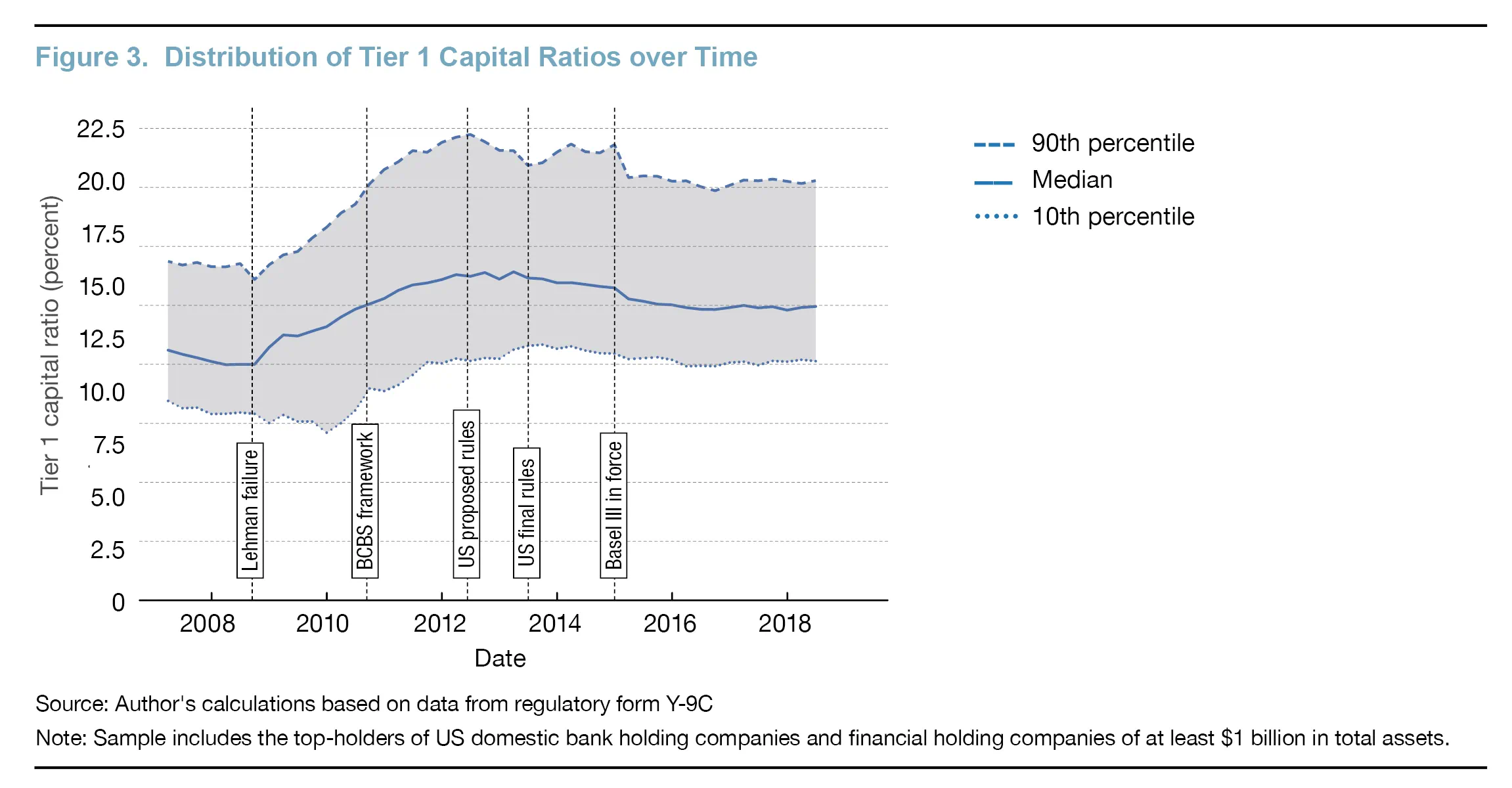

Just like capital ratios did not move uniformly across groups of different sizes, there was variation in the evolution of tier 1 capital ratios between banks with stronger and weaker capital positions. To illustrate this variation, Figure 3 plots the time series of tier 1 capital ratios across three points of the distribution. The thick solid line at the center represents the tier 1 capital ratio of the median bank at the 50th percentile, that is, the capital ratio that within each quarter sits right in the middle of the distribution, with 50 percent of banks having lower capital ratios and the other 50 percent having capital ratios that are higher. The thinner dashed lines at the top and bottom of the chart represent the 90th and 10th percentile of the distribution, respectively.

Figure 3 shows that while both the median and the 90th percentile started their post-crisis increase by early 2009, the bottom of the distribution was lagging: the 10th percentile kept falling throughout 2009, reaching a low of below 8 percent, and only started to increase about a year later, in 2010. This lag suggests that banks with lower capital ratios during and shortly after the financial crisis might have found it harder to rebuild their capital ratios afterwards. Having said that, the 10th percentile tier 1 capital ratio stabilized at a level of around 10 percent by 2012, at a similar time as the median and the 90th percentile, and again well before the new, higher capital requirements of Basel III broadly came into force.

This Economic Commentary analyzes the evolution of banks’ regulatory tier 1 capital ratios amid the new stricter capital regulations introduced following the 2007–2008 financial crisis. The new rules were introduced with the objective to make banks and the financial system safer and reduce the risk of a repeat of the crisis. The analysis shows that following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, on average United States banks of all sizes increased their regulatory capital ratios notably, generally to levels well above the required minimums. In addition, the increase in the average tier 1 capital ratios was largely completed by 2012, well before the new, higher capital requirements of Basel III came into force. This series of events is consistent with the view that banks increased their capital ratios preemptively rather than waiting until the rules were binding.

Furthermore, the data suggest that there was significant variation across banks in the timing of these increases in capital ratios. While the larger banks started increasing their tier 1 capital ratios as early as 2008 on average, it took a little longer, until about early 2009, for the smaller community banks to start the process, albeit with the community banks having started the increase from a higher initial level on average. Similarly, while better-capitalized banks started increasing their capital ratios by the end of 2008, less-well-capitalized banks started the process only from 2010 onward.

The overall pattern of increases in tier 1 capital ratios means that the desired outcomes of the Basel III reforms, including higher capital levels and thus safer banks, were at least partly achieved relatively quickly after the rules had been announced. However, the analysis in this article is descriptive and does not speak directly to the causal impact of the Basel III reforms. Nonetheless, the overall message is consistent with the findings in a recent working paper on the effect of the reforms (Fritsch and Siedlarek, 2022). That paper employs a difference-in-differences model to disentangle the effect of the regulations from other factors, exploiting the cross-sectional variation between banks in the extent to which the new rules reduced measured capital levels. It shows that the proposed rules implementing Basel III triggered a response by the affected banks soon after the rules’ publication in June 2012, with banks responding more strongly the more they were affected by the new rules.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Comptroller of the Currency. 2023. “Agencies Request Comment on Proposed Rules to Strengthen Capital Requirements for Large Banks.” Joint Press Release. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. July 27, 2023. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20230727a.htm .

- Fritsch, Nicholas, and Jan-Peter Siedlarek. 2022. "How Do Banks Respond to Capital Regulation?—The Impact of the Basel III Reforms in the United States." Working Paper No. 22-11. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-202211 .

- Walter, John. “US Bank Capital Regulation: History and Changes Since the Financial Crisis.” Economic Quarterly 105(1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.21144/eq1050101 .

- See the joint press release by the US bank regulatory agencies, “Agencies Request Comment on Proposed Rules to Strengthen Capital Requirements for Large Banks,” July 27, 2023, available from the Board of Governors at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20230727a.htm . Return to 1

- Tier 1 capital is a measure of “core" capital comprising common stock, retained earnings, and a limited set of additional instruments able to absorb losses on an ongoing basis, that is, before the failure of the bank. Total capital is a wider measure that includes tier 1 capital but also allows for additional capital instruments that absorb losses on a gone-concern basis, that is, when the bank fails and is no longer solvent. Risk-weighted assets provide a measure of the size of a bank balance sheet that is adjusted for differences in risk across different asset classes, with higher weights assigned to riskier asset classes. Return to 2

- See Walter (2019) for a comprehensive discussion of the history of United States bank capital regulation and the post-crisis reforms enacted since 2008. Return to 3

- The Basel III framework identifies G-SIBs based on a set of indicators, including the extent of cross-border activities, size, complexity, interconnectedness, and substitutability in the financial system. Return to 4

- For banks following the so-called “advanced approaches” framework to capital regulation, compliance with the higher Basel III minimum became mandatory one year earlier, on January 1, 2014. The advanced approaches framework is mandatory for the largest and internationally active banking organization with at least $250 billion in total assets or at least $10 billion in foreign exposures and is optional for others. Return to 5

- The sample ends in 2018:Q2 to ensure a consistent population of banks as the filing threshold was increased from $1 billion to $3 billion in total assets from 2018:Q3 onward. Return to 6

Suggested Citation

Siedlarek, Jan-Peter. 2024. “The Evolution of US Bank Capital around the Implementation of Basel III.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2024-07. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202407

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

4 .1 Ratio analysis. Ratio analysis is a devise of financial statement analysis conducive to business dec ision-making in multiple crux. ar eas. This analysis supports perception of sea changes in ...

We examine research that has developed financial ratio models to: (a) predict significant corporate events; and (b) predict future performance after significant corporate events. The events we analyze include financial distress and bankruptcy, downsizing, raising equity capital, and material earnings misstatements.

In this publication we cover the basics of using ratio analysis to analyze financial statements. Horizontal and vertical analyses are other common techniques to compare and analyze financial statements from different reporting periods. There are three main financial statements that need to be understood to evaluate

The Journal of Business Finance & Accounting (JBFA) is a corporate finance journal publishing research in accounting, corporate finance and corporate governance. The Analysis and Use of Financial Ratios: A Review Article - Barnes - 1987 - Journal of Business Finance & Accounting - Wiley Online Library

Ratio analysis is a study of relationship among various financial factors in a business [1]. Thus, it seeks to measure the value of the entity and purpose which it pursues, financial analysis develops the steps of collecting, shaping and treatment of a range of management information which may clarify the wanted diagnosis and prognosis.

This paper provides guidance on the appropriate estimation of financial ratios for empirical research corporate finance, corporate governance and accounting. Practical examples are provided employing the widely-used Compustat database, and all calculated ratios are made available for download in a dataset. A companion Github repository of the ...

Find a journal Publish with us Track your research Search. Cart. Financial Statements pp 229-275Cite as. ... Grahame Steven (2006): Financial Management, September 2006, Papers P1, P2, and P3. 14. Meir Tamari (1066): ... The Analysis and Use of Financial Ratios: A Review Article, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, Vol. 14, ...

Abstract. Financial analysis involves the selection, evaluation, and interpretation of financial data and other pertinent information to assist in evaluating the operating performance and financial condition of a company. The operating performance of a company is a measure of how well a company has used its resources—its assets, both tangible ...

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications. ... Financial ratio analysis is a ...

Financial statement analysis has traditionally been seen as part of thefundamental analysis required for equity valuation. But the analysis has typicallybeen ad hoc. Drawing on recent research on accounting-based valuation, this paperoutlines a financial statement analysis for use in equity valuation. Standardprofitability analysis is incorporated, and extended, and is complemented with ...

Findings - The study was able to identify and categorise past studies into areas of Financial evaluation, Insolvency Prediction, Valuation, Inter-linkage studies, Benchmarking & Decision making, Technical Analysis. Limitations of ratios identified from the literature are Proliferation of ratios, Lack of Normality and Accounting framework impact.

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.5, No.19, 2014 153 A Comparative Analysis of the Financial Ratios of Selected Banks in the India for the period of 2011-2014 Rohit Bansal Assistant Professor Department of management studies,Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Petroleum Technology ...

Abstract: Financial ratio analysis is the process of reviewing the financial position of the company. Ratio analysis is extensively used by firms as a technique to forecast the financial ... The research also highlights the ratios that can be useful in forecasting the bankruptcy and financial performance of the organizations. Ohlson (1980 ...

In this paper, I review the extant research on financial statement analysis. I then provide some preliminary evidence using Chinese data and offer suggestions for future research, with a focus on utilising unique features of the Chinese business environment as motivation.

Ratio Analysis: A ratio analysis is a quantitative analysis of information contained in a company's financial statements. Ratio analysis is used to evaluate various aspects of a company's ...

International Journal of Innovative Research in Management Studies (IJIRMS) Volume 2, Issue 3, April 2017. pp.31-39. A STUDY ON FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE USING RATIO ANALYSIS OF BHEL, TRICHY S.Saigeetha1 and Dr.S.T.Surulivel2 1II Year MBA ... Forecasting company failure in the UK using discriminant analysis and financial ratio data. This paper

The research identified parameters (economic factors) that potentially affect the value of Greek construction companies' financial ratios. Finally, prediction models for these financial ratios are proposed based on multiple regression analysis. The resulting models are designed for each specific construction enterprise.

Working Papers; Research in Brief; Community Development Reports; ... While larger and better-capitalized banks increased capital ratios soon after the financial crisis, it took smaller and less-well-capitalized banks longer on average to start that process. ... This analysis of capital ratios around an earlier episode of increased capital ...

Financial ratio is most important tool for accounting analysis. In this paper, researcher will study on ratio analysis, its usefulness, its effectiveness with using various past published papers ...