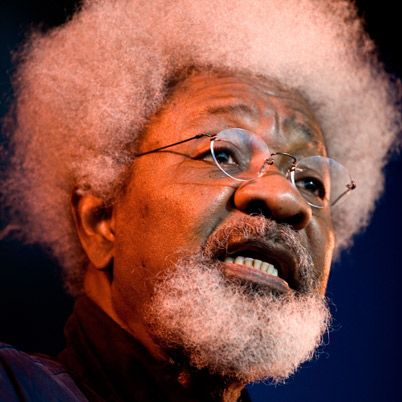

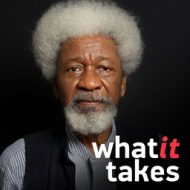

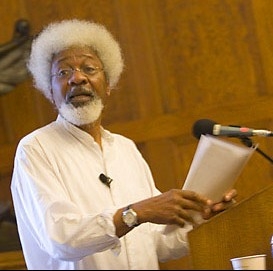

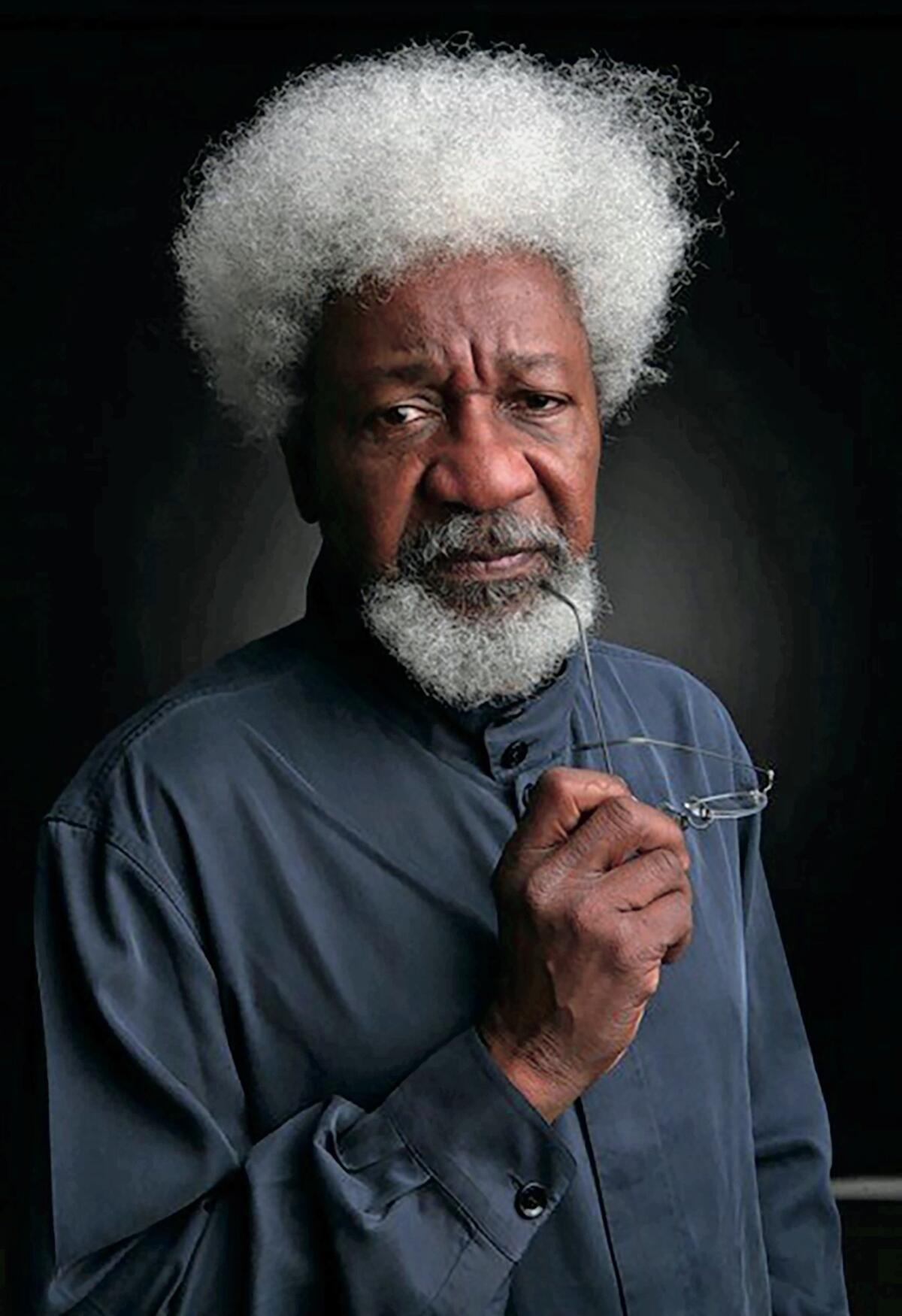

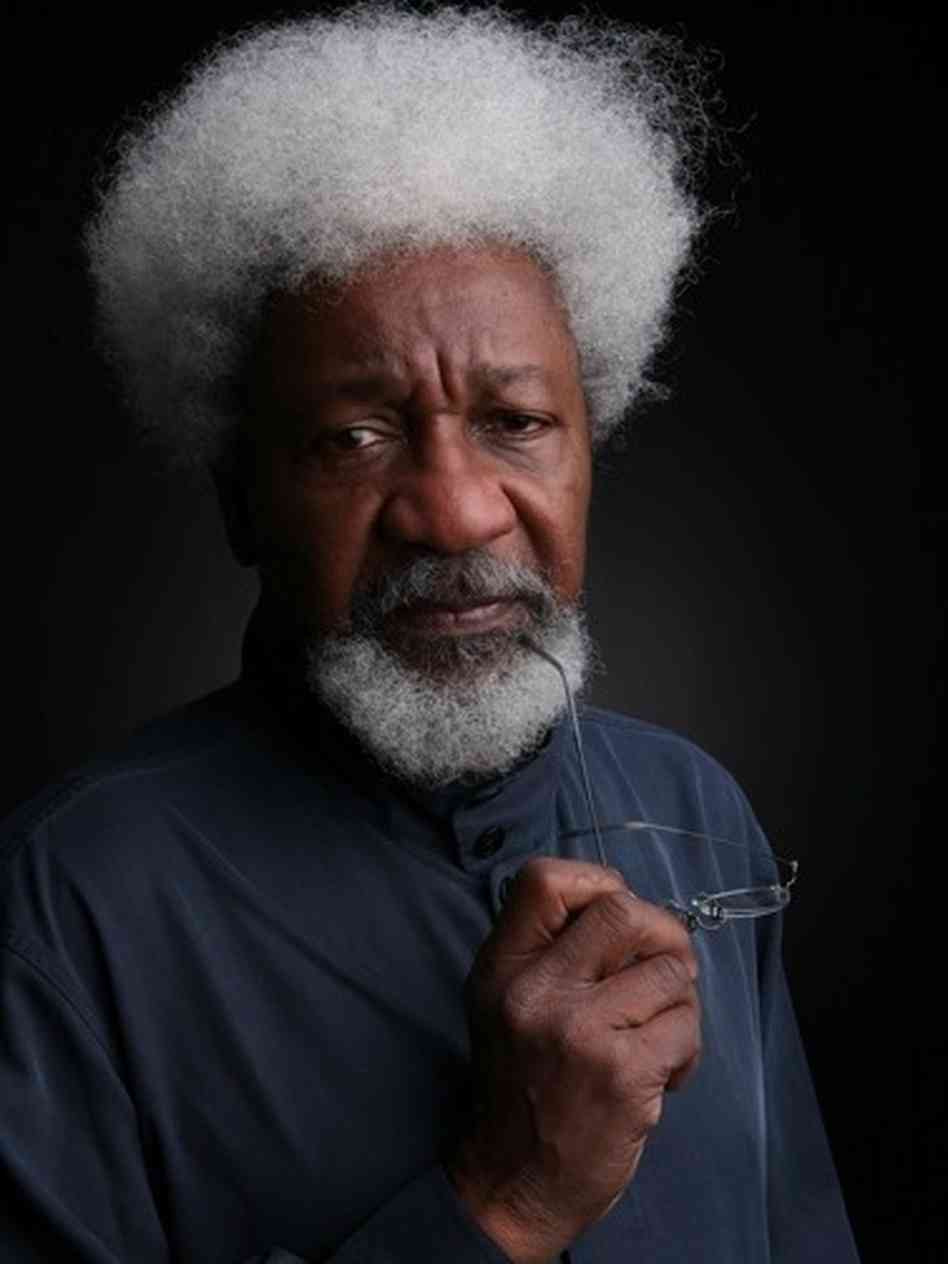

Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright, poet, author, teacher and political activist. In 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Who Is Wole Soyinka?

Wole Soyinka was born Akinwande Oluwole "Wole" Babatunde Soyinka on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, near Ibadan in western Nigeria. His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was a prominent Anglican minister and headmaster. His mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, who was called "Wild Christian," was a shopkeeper and local activist. As a child, he lived in an Anglican mission compound, learning the Christian teachings of his parents, as well as the Yoruba spiritualism and tribal customs of his grandfather. A precocious and inquisitive child, Wole prompted the adults in his life to warn one another: “He will kill you with his questions.”

After finishing preparatory university studies in 1954 at Government College in Ibadan, Soyinka moved to England and continued his education at the University of Leeds, where he served as the editor of the school's magazine, The Eagle . He graduated with a bachelor's degree in English literature in 1958. (In 1972 the university awarded him an honorary doctorate).

Plays & Political Activism

In the late 1950s Soyinka wrote his first important play, A Dance of the Forests , which satirized the Nigerian political elite. From 1958 to 1959, Soyinka was a dramaturgist at the Royal Court Theatre in London. In 1960, he was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship and returned to Nigeria to study African drama.

In 1960, he founded the theater group, The 1960 Masks, and in 1964, the Orisun Theatre Company, in which he produced his own plays and performed as an actor. He has periodically been a visiting professor at the universities of Cambridge, Sheffield, and Yale.

"The greatest threat to freedom is the absence of criticism."

Soyinka is also a political activist, and during the civil war in Nigeria he appealed in an article for a cease-fire. He was arrested for this in 1967, and held as a political prisoner for 22 months until 1969.

Nobel Prize and Later Career

In 1986, upon awarding Soyinka with the Nobel Prize for Literature, the committee said the playwright "in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence." Soyinka sometimes writes of modern West Africa in a satirical style, but his serious intent and his belief in the evils inherent in the exercise of power are usually present in his work. To date, Soyinka has published hundreds of works.

In addition to drama and poetry, he has written two novels, The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anom y (1973), as well as autobiographical works including The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), a gripping account of his prison experience, and Aké ( 1981), a memoir about his childhood. Myth, Literature and the African World (1975) is a collection of Soyinka’s literary essays.

“Against my rational instincts, I believe that we have here a genuine case of a born-again democrat,” he said. Ultimately, “the real heroes of this exercise have been the Nigerian people and that gingers me up.”

Now considered Nigeria’s foremost man of letters, Soyinka is still politically active and spent the 2015 election day in Africa’s biggest democracy working the phones to monitor reports of voting irregularities, technical issues and violence, according to The Guardian . After the election on March 28, 2015, he said that Nigerians must show a Nelson Mandela–like ability to forgive president-elect Muhammadu Buhari’s past as an iron-fisted military ruler, according to Bloomberg.com.

Personal Life

Soyinka has been married three times. He married British writer Barbara Dixon in 1958; Olaide Idowu, a Nigerian librarian, in 1963; and Folake Doherty, his current wife, in 1989. In 2014, Soyinka revealed he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and cured 10 months after treatment.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Wole Soyinka

- Birth Year: 1934

- Birth date: July 13, 1934

- Birth City: Abeokuta

- Birth Country: Nigeria

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright, poet, author, teacher and political activist. In 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

- Writing and Publishing

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- University College

- University of Leeds

- Government College

- Nationalities

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- A tiger doesn't proclaim his tigritude, he pounces.

- Under a dictatorship, a nation ceases to exist. All that remains is a fiefdom, a planet of slaves regimented by aliens from outer space.

- Books and all forms of writing are terror to those who wish to suppress the truth.

- The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.

Nobel Prize Winners

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

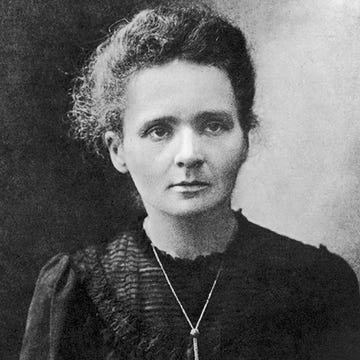

Marie Curie

Martin Luther King Jr.

Henry Kissinger

Malala Yousafzai

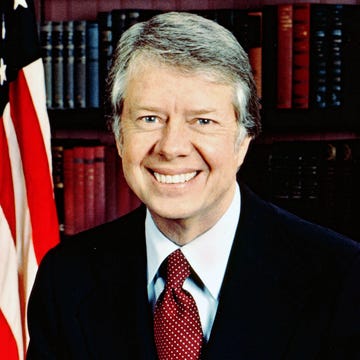

Jimmy Carter

10 Famous Poets Whose Enduring Works We Still Read

22 Famous Scientists You Should Know

Jean-Paul Sartre

Albert Camus

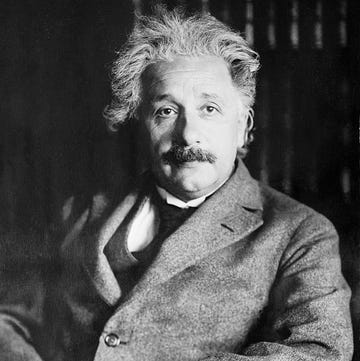

Albert Einstein

- Member Interviews

- Science & Exploration

- Public Service

- Achiever Universe

- Summit Overview

- About The Academy

- Academy Patrons

- Delegate Alumni

- Directors & Our Team

- Golden Plate Awards Council

- Golden Plate Awardees

- Preparation

- Perseverance

- The American Dream

- Recommended Books

- Find My Role Model

All achievers

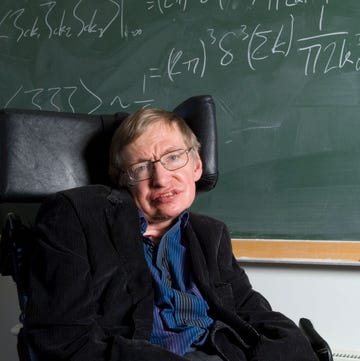

Wole soyinka, nobel prize in literature.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: public service, science and exploration, sports, technology, business, arts and humanities, and justice.

Writing became a therapy. I was reconstructing my own existence. It was also an act of defiance.

Akonwande Oluwole “Wole” Soyinka was born in Abeokuta in Western Nigeria. At the time, Nigeria was a Dominion of the British Empire. British religious, political and educational institutions co-existed with the traditional civil and religious authorities of the indigenous peoples, including Soyinka’s ethnic group, the Yorùbá people, who predominate in Western Nigeria. As a child, Soyinka lived in an Anglican Christian enclave known as the Parsonage. Soyinka’s mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, was a devout Anglican; in his memoirs, Wole Soyinka calls his mother “Wild Christian.” His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was headmaster of the parsonage primary school, St. Peter’s. Known as “S.A.,” Wole Soyinka calls him “Essay” in his memoirs. Although the Soyinka family had deep ties to the Anglican Church, they enjoyed close relations with Muslim neighbors, and through his extended family — particularly his father’s relations — Wole Soyinka gained an early acquaintance with the indigenous spiritual traditions of the Yorùbá people. Even among practicing Christians, belief in ghosts and spirits was common. The young Wole Soyinka enjoyed participating in Anglican services and singing in the church choir, but he also formed an early identification with Ogun, the Yorùbá deity associated with war, iron, roads and poetry.

Soyinka’s mother, a shopkeeper, joined a protest movement, led by her sister Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, against the traditional ruler, the Alake of Abeokuta, who ruled with the support of the British colonial authorities. When the Alake levied oppressive taxes against the shopkeepers, Mrs. Ransome-Kuti, Mrs. Soyinka, and their followers refused to pay, and the Alake was forced to abdicate.

Thanks to his father, young Wole Soyinka enjoyed access to books, not only the Bible and English literature but to classical Greek tragedies such as the Medea of Euripides, which had a profound effect on his imagination. A precocious reader, he soon sensed a link between the Yorùbá folklore of his neighbors and the Greek mythology underlying so much of western literature.

He moved quickly from St. Peter’s Primary School to the Abeokuta Grammar School and won a scholarship to the colony’s premier secondary school, the Government College in Ibadan. At this boarding school, he continued to distinguish himself in his studies, writing stories and acting in school plays, the beginning of his lifelong preoccupation with the practical aspects of theatrical performance.

After graduation at age 16 from the Government College, Soyinka deferred immediate admission to university life and moved to the colonial capital, Lagos, to work in an uncle’s pharmacy for two years before entering university. During this period of personal independence, he began writing plays for local radio. In 1950, he entered the University at Ibadan. Two years later, won a scholarship to the University of Leeds in England, and left Africa for the first time.

In England, he joined a close-knit community of West African students. The petty racism they encountered in Britain seemed less important than the reports they read from South Africa of black Africans being subjected to legally enforced racial discrimination in their own country by the white-led apartheid government. Along with his fellow African students, Soyinka imagined a pan-African movement to liberate South Africa. He went so far as to enlist in the British program of student military education, in hopes that he could use this training in a future campaign against the apartheid regime in South Africa. He dropped out of the program during the Suez Crisis, when it appeared that students might be called up to serve in Egypt. As Britain prepared to leave Nigeria, students like Soyinka were excused from further military service.

After graduating from the University of Leeds, Wole Soyinka continued to study for a master’s degree while writing plays drawing on his Yorùbá heritage. His first major works, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel , date from this period. In 1958, The Lion and the Jewel was accepted for production by the Royal Court Theatre in London. Beginning in the late 1950s, the Royal Court was the major venue for serious new drama in Britain. Soyinka interrupted his graduate studies to join the theater’s literary staff. From this post, he was able to watch the rehearsal and development process of new plays at a time when the British theater was entering a period of renewed vitality. His own next major work was The Trials of Brother Jero , expressing his skepticism about the self-styled elite of black Nigerians who were preparing to take power from the British colonial regime.

In 1960, Soyinka received a Rockefeller Foundation grant to research traditional performance practices in Africa. Nigeria was poised to become independent from Britain, and Soyinka’s play A Dance of the Forest, another satire of the colonial elite, was chosen to be performed during the independence festivities. Soyinka joined the English faculty at the University of Ibadan. He also formed a theater company, 1960 Masks, to produce topical plays, employing traditional performance techniques to dramatize the many issues arising from Nigerian independence. His writings, including his 1964 novel, The Interpreters , were bringing him fame outside his own country, but he faced increasing difficulties with censorship inside Nigeria. Independence from Britain had not brought about the open democratic society Soyinka and others had hoped for. In negotiating the independence of the country, Britain had overestimated the population of the northern region, dominated by Hausa-Fulani people of Muslim faith, and given them greater representation in the national parliament, at the expense of the predominantly Christian peoples of the southern regions: the Yorùbá in the West and the Igbo in the East.

In Western Nigeria, the results of a 1964 regional election were set aside so that a candidate favored by the central government could claim victory. With some friends, Soyinka forced his way into the local radio station and substituted a tape of his own for the recorded message prepared by the fraudulent victor of the election. This escapade caused his arrest and detention for two months, but international publicity led to his acquittal. Following his release, Soyinka was appointed to the English Department of Lagos University, and completed the comedy Kongi’s Harvest , which would be produced throughout the English-speaking world. Soyinka had become one of the best-known writers in Africa, but political developments would soon thrust him into a more difficult role. The discovery of oil in the Southeast in 1965 further heightened ethnic and regional tensions in Nigeria. A 1966 military coup led by Igbo officers was followed by a counter-coup, which installed the young army officer Yakubu Gowon as head of state. Massacres of Igbo living in the North sent more than a million refugees fleeing south, and many Igbo began to call for secession from Nigeria. Hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Soyinka traveled in secret to meet with the secessionist General Ojukwu and urged a peaceful resolution. When Ojukwu and the Eastern forces declared an independent Republic of Biafra, Soyinka contacted General Obasanjo of the Western forces to urge a negotiated settlement of the conflict, but Obasanjo sided with the national government, and a full-scale civil war ensued. Soyinka’s friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo, joined the Biafran forces and was killed in action.

Soyinka was accused of collaborating with the Biafrans and went into hiding. Captured by Nigerian federal troops, he was imprisoned for the rest of the war. From his prison cell, he wrote a letter asserting his innocence and protesting his unlawful detention. When the letter appeared in the foreign press, he was placed in solitary confinement for 22 months. Despite being denied access to pen and paper, Soyinka managed to improvise writing materials and continued to smuggle his writings to the outside world. A volume of verse, Idanre and Other Poems , composed before the war, was published to international acclaim during his imprisonment. By the end of 1969, the war was virtually over. Gowon and the Nigerian federal army had defeated the Biafran insurgency, an amnesty was declared, and Soyinka was released. Unable to return immediately to his old life, he repaired to a friend’s farm in the South of France. While recuperating, he wrote an adaptation of the classical Greek tragedy The Bacchae by Euripides. Across the millennia, the story of a state destroyed by a sudden eruption of senseless violence had acquired a special resonance for Soyinka. Another volume of verse, Poems from Prison , also known as A Shuttle in the Crypt , was published in London.

Soyinka returned to Nigeria to head the Department of Theater Arts at the University of Ibadan. The 1970s were a productive decade for Wole Soyinka. He oversaw stage and film productions of his play Kongi’s Harvest and wrote one of his most compelling satirical plays, Madmen and Specialists . His prison memoir, The Man Died , was published in 1972, followed by a novel, The Season of Anomy . He traveled to France and the United States for productions of his plays. When political tensions resurfaced, unresolved by the civil war, Soyinka resigned his university post and went to live in Europe, lecturing at Cambridge and other universities. Oxford University Press published his Collected Plays in 1974. One of his greatest works appeared the following year, the poetic tragedy Death and the King’s Horseman . After a number of years in Europe, Soyinka settled for a time in Accra, Ghana, where he edited the literary journal Transition . His column in the magazine became a forum for his continued commentary on African politics, in particular for his denunciation of dictatorships such as that of Idi Amin in Uganda.

In 1975, General Gowon was deposed, and Soyinka felt confident enough to return to Nigeria, where he became Professor of Comparative Literature and head of the Department of Dramatic Arts at the University of Ife. He published a new poetry collection, Ogun Abibiman , and a collection of essays, Myth, Literature and the African World , a comparative study of the roles of mythology and spirituality in the literary cultures of Africa and Europe. His continuing interest in international drama was reflected in a new work, inspired by John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera and Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera . Soyinka called his musical allegory of crime and political corruption Opera Wonyosi . He created a new theatrical troupe, the Guerilla Unit, to perform improvised plays on topical themes.

At the turn of the decade, Wole Soyinka’s creativity was expanding in all directions. In 1981, he published the first of several volumes of autobiography, Aké: The Years of Childhood . In the early 1980s, he wrote two of his best-known plays, Requiem for a Futurologist and A Play of Giants , satirizing the new dictators of Africa. In 1984, he also directed the film Blues for a Prodigal . For years, Soyinka had written songs. In the 1980s, Nigerian music, including that of Soyinka’s cousin, the flamboyant bandleader Fela Ransome-Kuti, was capturing the attention of listeners around the world. In 1984, Soyinka released an album of his own music entitled I Love My Country , with an assembly of musicians he called The Unlimited Liability Company.

Soyinka also played a prominent role in Nigerian civil society. As a faculty member at the University of Ife, he led a campaign for road safety, organizing a civilian traffic authority to reduce the shocking rate of traffic fatalities on the public highways. His program became a model of traffic safety for other states in Nigeria, but events soon brought him into conflict with the national authorities. The elected government of President Shehu Shagari, which Soyinka and others regarded as corrupt and incompetent, was overthrown by the military, and General Muhammadu Buhari became Head of State. In an ominous sign, Soyinka’s prison memoir, A Man Died, was banned from publication.

Despite troubles at home, Soyinka’s reputation in the outside world had never been greater. In 1986, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first African author to be so honored. The Swedish Academy cited the “sparkling vitality” and “moral stature” of his work and praised him as one “who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” When Soyinka received his award from the King of Sweden in the ceremony in Stockholm, he took the opportunity to focus the world’s attention on the continuing injustice of white rule in South Africa. Rather than dwelling on his own work, or the difficulties of his own country, he dedicated his prize to the imprisoned South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. His next book of verse was called Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems . He followed this with two more plays, From Zia with Love and The Beatification of Area Boy , along with a second collection of essays, Art, Dialogue and Outrage . He continued his autobiography with Isara: A Voyage Around Essay , centering on his memories of his father S.A. “Essay” Soyinka, and Ibadan, The Penkelemes Years .

Meanwhile, Soyinka continued his criticism of the military dictatorship in Nigeria. In 1994, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) named Wole Soyinka a Goodwill Ambassador for the promotion of African culture, human rights and freedom of expression. Less than a month later, a new military dictator, General Sani Abacha, suspended nearly all civil liberties. Soyinka escaped through Benin and fled to the United States. Soyinka judged Abacha to be the worst of the dictators who had imposed themselves on Nigeria since independence. He was particularly outraged at Abacha’s execution of the author Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was hanged in 1995 after a trial condemned by the outside world. In 1996, Soyinka published The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Memoir of the Nigerian Crisis . Predictably, the work was banned in Nigeria, and in 1997, the Abacha government formally charged Wole Soyinka with treason. General Abacha died the following year, and the treason charges were dropped by his successors.

Since 1994, Wole Soyinka has resided primarily in the United States. He has taught at a number of American universities, including Emory University in Atlanta, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles. Since moving to the United States, he has written another play, King Baabu , a volume of verse, Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known , and his latest book of memoirs, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006).

Although Wole Soyinka has always been reticent about discussing his family life, in this volume he makes a particularly touching dedication to his “stoically resigned” children, and to his wife Adefolake, for enduring many years of hardship and dislocation.

Although presidential elections were held in Nigeria in 2007, Soyinka denounced them as illegitimate due to ballot fraud and widespread violence on election day. Wole Soyinka continues to write and remains an uncompromising critic of corruption and oppression wherever he finds them.

The poet and playwright Wole Soyinka is a towering figure in world literature. He has won international acclaim for his verse, as well as for novels such as The Interpreters . His work in the theater ranges from the early comedy The Lion and the Jewel to the poetic tragedy Death and the King’s Horseman .

Born in Nigeria, he returned from graduate studies in England just as his country attained its independence from Britain. Many of his plays, including Kongi’s Harvest and Madmen and Specialists , are bitter satires on the dictatorships of post-colonial Africa. In the late ’60s, his opposition to a repressive regime in his own country led to his imprisonment in solitary confinement for nearly two years, an experience he reflects on in the memoir The Man Died and the verse collection A Shuttle in the Crypt .

His works in all genres deploy a rich poetic language, steeped in European mythology and the Yorùbá spiritual traditions of West Africa, interests he fused in his masterful study Myth, Literature and the African World . In 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Apart from your literary career, you have played a very active political role in Nigeria, beginning many years ago. During the Western regional crisis of 1965, you took to the airwaves to denounce the falsification of election results. Could you tell us how that came about?

Wole Soyinka: Those elections were very violent and the people resisted. This was the Western Region at the time. I was then teaching at the University of Ibadan. Violent, and the incumbent government used its power of incumbency in the region, in alliance with the power of the center. It was a federal structure. In spite of that, they could not rig the election successfully. And so what they did was just start altering the results. And even that proved exceedingly difficult for them. Finally the premier of the region decided to just forget the whole thing and announce his victory on radio. And I happened, you know, by very fortunate coincidence, I learned that this was going to become a fait accompli . And since he had the support of the federal government, something drastic had to be done. And so with some assistance, some of my usual collaborators, I managed to stop the broadcast, substitute my — I pre-recorded my own statement. So I went to the studio and I took the premier’s tape off and substituted my own and went away. And so I was tried — very, very nasty charge. I was charged with armed robbery, because apparently this event was supposed to have taken place with the aid of a gun, and so — very cunning people, coming to frame a charge of armed robbery, for a tape! Costs under a pound or whatever, and I substituted one, anyway — so it wasn’t — and I left that one. So where was the robbery?

Anyway, I was tried and acquitted, thank goodness. Then some years passed. Of course the seeds of what came later were already being laid and planted, from that rigging of the elections in the West, and in the rest of the country, as a matter of fact. So a military coup took place in 1966, in January. There were massacres, especially against the Igbos, because the first coup, the leaders were mostly Igbo, and so reprisal claims took place and the drums of war began to sound very, very loud. The East Igbos, who felt they had been really violated — because they were hunted down all over the place, not just in the North — they decided to secede.

My friend Christopher Okigbo was Igbo, of course. I knew him from the writers and artists community in Ibadan. He was a founding member of the Mbari writers and artists club. When I was detained for that “un-robbery” episode, he used to come and visit me in my place of detention. I was not actually formally detained. I was just not granted bail, that’s all. So he used to come to visit me at the police station where I was held and we’d read his poetry together. Or more accurately, he would read his poetry. He loved reading his own poems. He wanted you to hear exactly how it sounded, because it was a very aural, musical kind of poetry. He was a musician also, by the way, so that wasn’t surprising. So we became quite close.

When I realized that war really was going to happen, I tried to — and he (Christopher Okigbo) had left, like the other Igbo that fled to the East, where they were more secure. Chinua Achebe was in the East. We had other writers like Gabriel Okara in the East, and I felt maybe by linking up and resurrecting that tight community we might be able to do something to prevent that war, and so I traveled. By then the firing had started, the early skirmishes had begun. And I traveled by road to the East. I was promptly arrested as a suspected enemy by the Biafrans whom I had come to see, but of course, some time after, the police realized who I was and I was released. And who had come into my police station? He didn’t know I was there. It was Christopher Okigbo, coming from the war front, coming for more equipment. And so we were reunited for the last time. He went back to the front. So the leader of the secessionist enclave, Ojukwu, we spoke, and then when I came back I was detained for having traveled to the East. I was accused of all kinds of things, including trying to buy jet fighters for the — I don’t know why people like to cook, you know, fantasies, around one’s individual existence.

Why did you take on this role of intermediary between the Biafrans and the West?

Wole Soyinka: I belong to the West, the Yorùbá part of the federation. And in a war, when a war is being fought, it is being fought on behalf of people. And this war committed me, as a Nigerian, it committed me, and I felt that war was wrong and I refused to accept that, to be committed in that way. The Biafrans had been violated. They had been massacred. It was more than one massacre, it was like a wave of massacres. And they were being hunted everywhere. In other words, the conduct of the federal side, at least that portion to which I belong, indicated — said, in plain language, even though it was not articulated as such, “You, the Igbo, are no longer part of the federation.” There was no way, nothing was done to make them feel secure, at least not enough was done to make them feel secure in the rest of the nation. And then, after they had seceded, which I considered, by the way, a tactical mistake — not a political crime, not a moral crime, no, no, no, no, no. It was a tactical error. But then, to go after them, to declare war against them on this banal basis of unity above anything else! Unity of what? I mean, who committed the act of disuniting the nation in the first place? Those who made the Igbo feel they were not part of the full entity. So for me it was an unjust war of which I could not be a part. And if I’d not gone to the East, I would have gone into exile, because I would refuse to be part of that entity which waged war against a people who had been so dehumanized. So in effect, it was for my own peace of mind, to try and do everything possible to make sure the war did not take place.

When you returned to the West, you were detained, but never officially charged. Was this because of an open letter you had published in the Daily Times of Nigeria? What was your intent in writing that letter?

Wole Soyinka: First of all, the letter was published before I went to the East.

There was supposed to be a delegation going from the federal side, a delegation of citizens, you know, high-placed citizens, traditional rulers and so on. I wanted to make sure that when they went over to the East, they didn’t go mouthing pious, meaningless sentiment. They should understand that they were going to visit a wronged people, and that they should take the kind of message there that would make them come back. Well, as I expected, it was a futile visitation. The Igbo by that stage didn’t trust anyone, and in any case they could not, they had nothing concrete to take over to the other side. And so I followed up my letter by visiting there, and trying to get Chinua, Christopher, the group I knew, and also talk to Ojukwu, whom I’ve known — the head of the Biafran enclave — whom I’ve known. We were both students around the same time, even though he was somewhat older than myself. And when I came back, I brought back certain messages and delivered those messages on return.

I should add that when I went there, we had formed what we called the “Third Force.” Since the cause of the federal side, in our view, was not just, and since the Igbo had committed a tactical error in deciding on secession, we thought there should be a third force, a neutral force, which would put on the table various concrete proposals, in effect neutralizing the positions of both sides. We could present these proposals to both sides, and to the international community, which might finally succeed in bringing them to some kind of agreement.

You’ve made a distinction between your first arrest, in the mid-’60s, and your second arrest. If corruption, a rigged election, was the issue in the first case, what was really the issue when you were imprisoned the second time?

Wole Soyinka: Power is involved in this, you know. The tendency for sections of any community to dominate the rest seems to be part and parcel of society, historically. Nothing extraordinary, in my view, happened about what went on in Nigeria. It wasn’t really corruption that led to the first coup, even though this was one of the allegations. It had to do with a sense of injustice, of a political lie which had been implanted by the British before they departed. So it was the contest for power, as much as for control of resources. Because power is an element in itself which one should never underestimate. To dominate others seems to be kind of an animal part of the human make-up which we haven’t quite evolved out of. So corruption, yes, was involved, but it wasn’t really the central issue in those early days.

Days after your incarceration, your friend Christopher Okigbo was killed in the civil war. Did you hear of his death while you were in prison? Were you able to get news?

Wole Soyinka: I was in solitary confinement for quite a while, but after a while, even prison has its chinks which one is able to study and explore. So occasionally, after the really hermetic isolation of a couple of months, I was able to start formulating links with the outside world.

You smuggled a letter out of prison in 1967. How did it change your treatment in prison?

Wole Soyinka: First of all, I was held in a maximum security prison in Lagos. After I smuggled out that statement, the government panicked and decided to move me to Kaduna and place me in complete solitary confinement. I was shocked. It was one of the most bitter moments, bitterest moments of my incarceration, to find the Minister of Information calling an international press conference and reading what was supposed to be my confession. It’s one of the most horrible things that can happen to anybody in prison, that you feel, “What else? What is going to come next? What are they going to say next? What are they speaking in my name?” Reading —not to be accusing me, I mean, that’s okay — but actually saying, “I have here his confessional statement,” and every bit of it — except the trip to Biafra — a complete fabrication. But after I got to Kaduna, I stayed completely quiet for some time. Didn’t even attempt to reach the outside world. Just made sure they thought I was a complete model prisoner, totally resigned to being in isolation. And I began to probe the chinks and managed to start getting things outside. Even sent some poems for publication to my publisher outside, which was scribbled on toilet paper with ink I’d manufactured and so on.

You wrote about your prison experience in a memoir, The Man Died . Did you actually begin work on that book while you were in prison?

Wole Soyinka: I began writing, scribbling notes, you know, in prison. But it wasn’t actually published until after I’d come out. Writing became a therapy. First of all, it meant I was reconstructing my own existence. It was also an act of defiance. I wasn’t supposed to write. I wasn’t supposed to have paper, pen, anything, any reading material whatsoever. So this became an exercise in self-preservation, keeping up my spirits. It also, you had to occupy very long hours of the day, you know, not speaking to anyone. And I even — it wasn’t just writing. I evolved all kinds of mental exercises, even went back to those subjects which I said I hated in school, in particular mathematics. I started to try and recover my mathematical formulae by trial and error, and created problems for myself which I solved. You know, anything to keep the mind alive. As I said, it’s an exercise in self-preservation. Writing was just part of it.

- 42 photos

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

Wole soyinka (1934- ).

Akinwande Ouwole “Wole” Soyinka, the first African writer to win a Nobel Prize in Literature (1986) was born in Abeokuta, Nigeria on July 13, 1934. His father, Canon S.A. Soyinka, was an Anglican minister and his mother, Grace Eniola, was the daughter of an Anglican minister.

Soyinka received a primary school education in Abeokuta and then completed secondary school at Government College, Ibadan . He attended the University of Ibadan for two years (1952-1954) before completing his undergraduate education at the University of Leeds in England in 1957. Soyinka received his degree in drama at Leeds under the instruction of world-renowned Shakespearean critic G. Wilson Knight. He worked briefly as a play reader at the Royal Court Theater in London before returning to Nigeria to study African drama. Soyinka taught at the University of Lagos, the University of Ibadan, and the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. On the faculty at the latter institution since 1975, he is currently a Professor of Comparative Literature.

Soyinka wrote his first major plays, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel, while working at the Royal Court Theater in London. His next plays, The Trials of Brother Jero and A Dance of the Forest appeared after he returned to Nigeria in 1960. A Dance of the Forest , a biting criticism of Nigeria’s elites, was first performed on October 1, 1960, Nigeria’s Independence Day. In 1963, Soyinka’s first feature length film, Culture in Transition , was released. One year later, The Interpreters , his most famous novel, was published in London. Both pursued a similar theme.

By 1965, Soyinka’s reputation as a leading dramatist and a political critic of the government was well established. That year Soyinka was arrested for his criticism of recent elections but was released after protests from the international community. In 1967, he secretly and unofficially met with Ibo leaders in a vain attempt to prevent the Nigerian Civil War . When the war began Soyinka was declared a traitor and was incarcerated for the remainder of the war.

After his release, Soyinka lectured and lived in Europe. By 1975, he had returned to Africa and lived briefly in Accra , Ghana, where he edited a literary magazine called Transition . He used the magazine to critique African dictators such as Idi Amin in Uganda. He returned to Nigeria later that year after his political nemesis, General Yakubu Gowon , was removed from power. For the next decade he continued his writing and political protests prompting more government repression. His 1984 play, The Man Died , was banned by a Nigerian court. In 1986, however, Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In November 1994 Soyinka fled Nigeria and briefly lived in exile in the United States. In 1996, while in the U.S., he wrote The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis . The following year, he was charged with treason by the Nigerian military government. Soyinka returned to Nigeria when civilian rule was restored in 1999. However, his critique of the government continues. In April 2007, he called for the cancellation of Nigerian elections due to widespread violence and fraud.

In a career that has lasted more than five decades, Soyinka has written twenty-one plays, eight books of poetry, five books of essays, two novels, and five memoirs. He has also produced two feature-length films. Wole Soyinka lives in Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Biodun Jeyifo, Wole Soyinka: Politics, Poetics and Post Colonialism (New York: Cambridge Press, 2004); http://prelectur.stanford.edu/lecturers/soyinka/ .

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

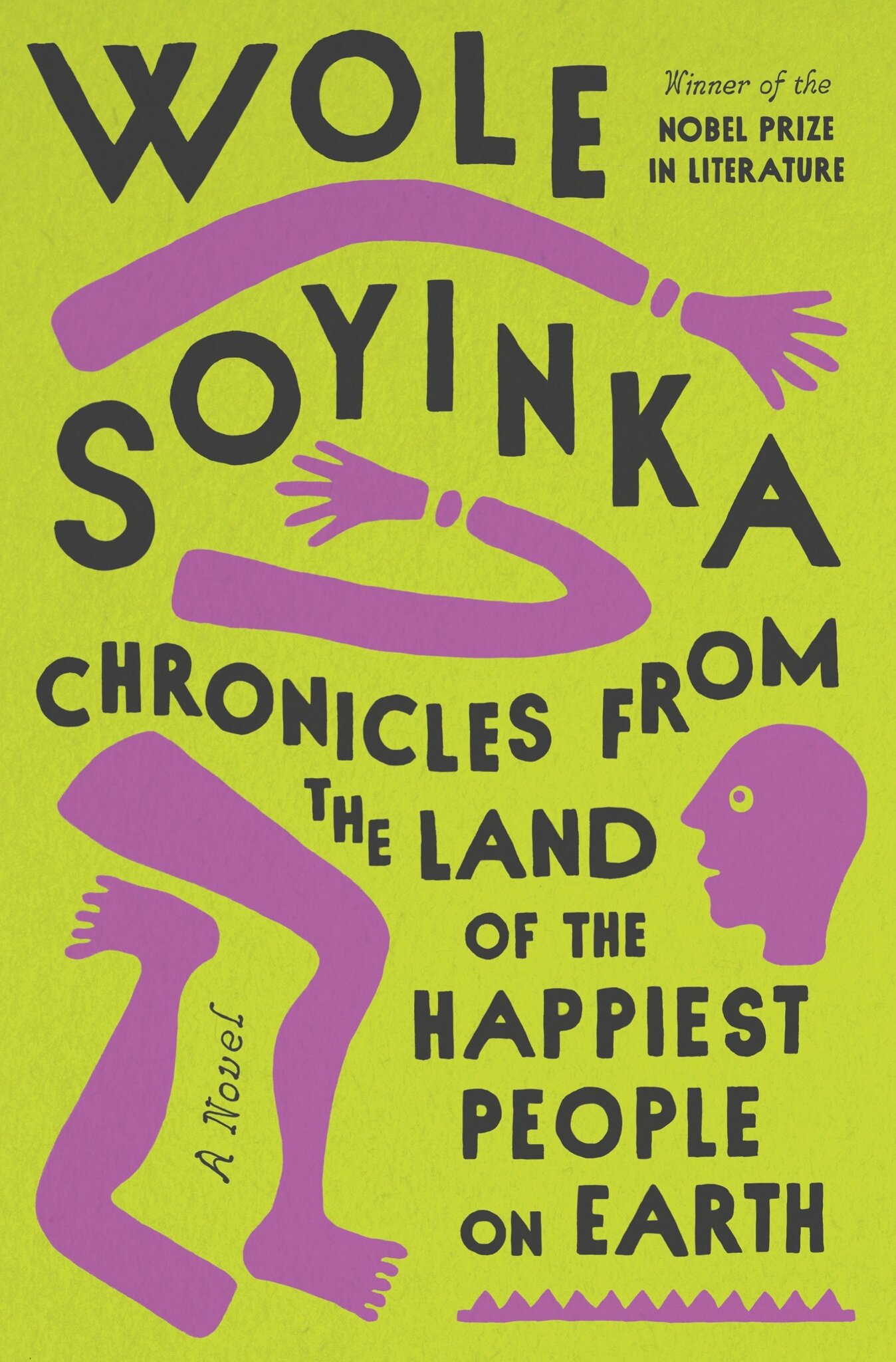

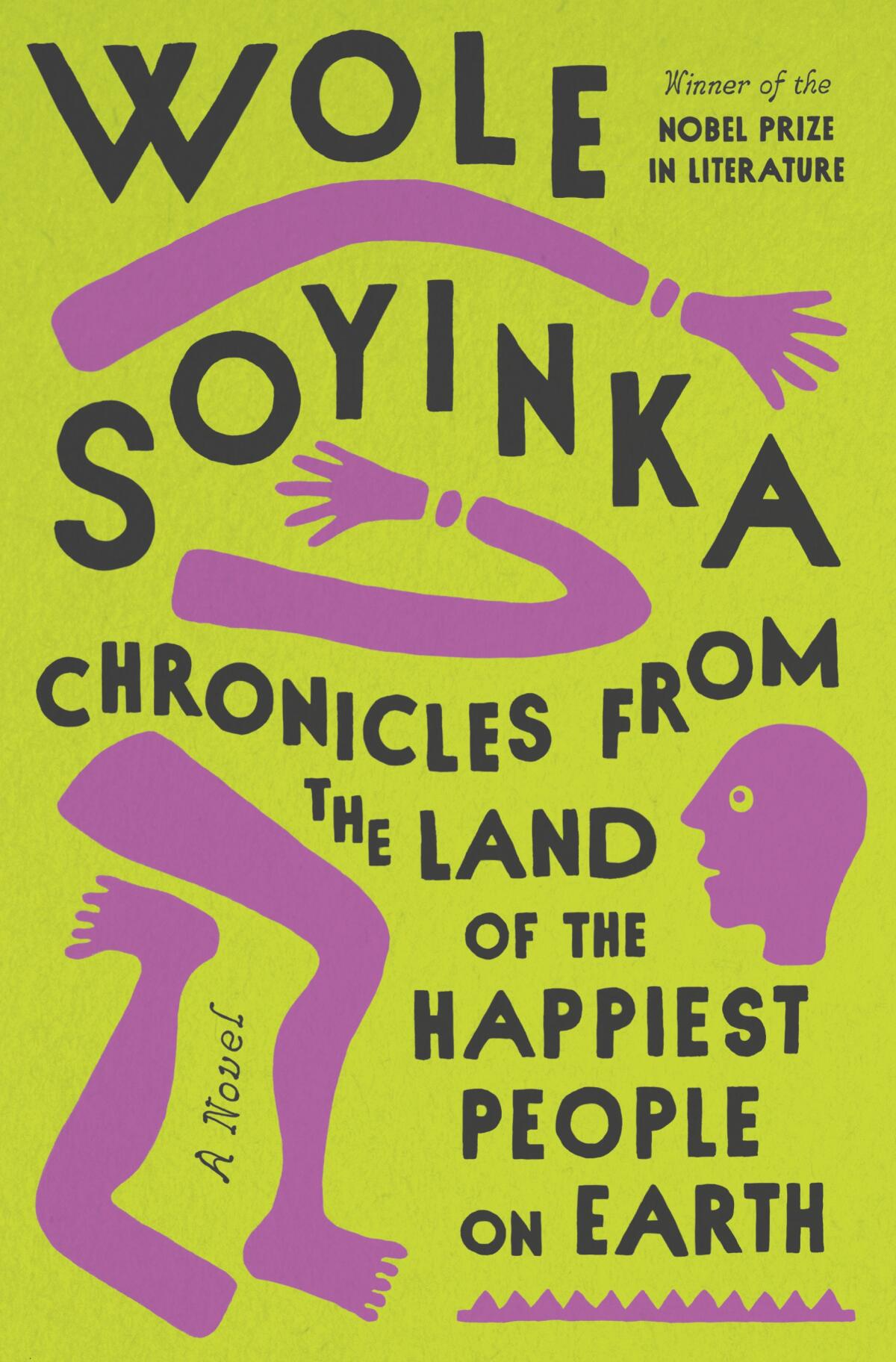

The Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka Discusses His First Novel in Nearly Fifty Years

By Vinson Cunningham

In 1965, five years after Nigeria had gained its independence, the playwright Wole Soyinka was already known as an opposition figure. Authorities falsely accused him of armed robbery, and, before the country’s civil war, in the late sixties, Soyinka tried to avert fighting. He was accused of conspiring with rebels and imprisoned by the Nigerian government. He’s a writer with an astonishing history of putting himself on the line for his political and social commitments.

Soyinka has received the Nobel Prize in Literature. He has written more than two dozen plays, a vast amount of poetry, several memoirs, essays, and short stories, and just two novels. His third novel is out now, nearly five decades after the last one. Called “ Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth ,” it’s both a political satire and a murder mystery. It involves four friends, a secret society dealing in human body parts, and more corruption than any one country can bear. The staff writer Vinson Cunningham spoke with Soyinka at his home in Nigeria.

I really want to talk to you about “Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth,” a title that I love. I heard that you’ve been thinking about this story for many years now. How does it feel to have it out in the world?

It’s been a little bit overwhelming, I think. I wasn’t expecting the standard reception of it. I mean, it’s just part of my own creative continuum, in a different format—you know, like taking time off from theatre to write a novel.

This is your third novel, and, of course, you’re known most prolifically for your works of theatre. But what is it that the novel does for you that theatre doesn’t? This change in form—are there necessities that it meets that theatre doesn’t, and vice versa? What’s the form about for you?

What the novel does for me as a medium of expression is to assuage the masochist in me, because the novel is very taxing—taxing in the sense that it’s tempting to go in so many directions. Theatre, for me, is more focussed. When you’re a narrator, you’re juggling a number of characters, and they insist on wandering very willfully in directions which you did not preview, you know? And then you forget where you last saw them, and so on. I really praise novelists, those whose métier is a novel. I have a hard time at it.

You offer us this total panoply of great characters. There’s a crooked religious leader. There are politicians, a sort of earnest diplomat, a famous doctor. Did you, in the course of writing this book—was there a favorite character that you alighted on? Was there one who was especially willful and sort of surprised you in different ways?

There’s no question at all that a number of the characters were “inspired” or “triggered” into being by personal encounters. I took great pains to insure that some of the villains knew that they provided the base material—and, in fact, I’ve even met one of them since the novel came out. He came up to me and I said, “Well, you’re coming to me. I hope you realize that you were this in the novel.” It was a politician and, like a good politician, he said, “Oh, Prof, that’s O.K. But I really want to discuss a certain issue with you in the novel. Forget that character.” So the novel does give one that latitude, I must confess, and then you can play variations, far more than in theatre. I think theatre is almost pre-written. By that I mean they are more constricted in the case of the theatre, and that is one of the reasons why tackling a theme like this human tumult in which I’ve been existing, watching others survive—me, too, surviving in my own way, watching that deterioration of society—the novel intuitively struck me as the only medium in which I could actually purge myself of this oppressive sense of society going haywire.

It’s interesting: there is this sense, this dark sense, of, as you say, a society going haywire, and it’s contrasted against this wonderful title, “The Land of the Happiest People on Earth.” Now, I heard that this was inspired by the “ World Happiness Report ,” where Nigeria was rated one of the happiest countries in the world. First of all, is that true? And what did that reality present to you artistically?

Well, when I saw that world report, I thought, Look at these people laughing at us. Why are they so cruel? Why are they doing this? And then I realized it was supposed to be a serious poll, a serious estimate. It was supposed to be objective, analytical, even scientific. And so I looked into this—I said, Maybe I’m in the wrong place, but when I looked around it was still a society which I recognize as my own, as the one in which I function. So it stuck in my head for quite a while. This was some years ago. And, when I began working on it, it actually began with other titles. Eventually, I slowly realized, Oh, wait a minute. That estimation, that analysis, is the exact title I’ve been looking for.

You know, happiness is such a fraught idea. Here in America, of course, we’ve sort of encoded it into our national myth—you know, the “pursuit of happiness.” What does it mean for you? Because, of course, it can be totally vapid, fun-seeking, surface—sort of epicureanism, I guess. But it can also speak to a real joy. What does it mean for you, and why did it fit so well?

It fits so well, of course, because it’s an irony. This country—people in this nation are not the happiest, by no strength of the imagination, and yet, at the same time, if they went deep enough in society, I think they would flee, or consign this nation to the place to be during your—what’s that season of yours, when you hang skeletons all over the place?

Halloween. [ Laughs. ]

Exactly, Halloween. Maybe this is Halloween nation, and they’re not going to understand it. But then, again, as I was saying, you do encounter those who extract, forcibly, a measure of contentment or fulfillment, even of the most meagre kind. They are buoyed either by religion or by an ingrained traditional philosophy that the worst is yet to come, and therefore you’d better enjoy the present. Because Nigerians do celebrate—I mean, that is not a lie. People all over the world where Nigerians are, they do salute Nigerians for their spirit of celebration, which is why I took pains to insure that at least one character represented what the pursuit of happiness might be—through creativity, through just love of others, through just making others happy, if only for a few moments. So it’s a mishmash of ironies, of acknowledgements, of concession, of even a measure of salute to the people. I hope that measure comes out, that element comes out.

Speaking of this issue of happiness and the different places where it can be found, or not found, you know—where it can be promised but not delivered, perhaps—one of those is religion. And a lot of this book turns on a kind of an upswing in religious fundamentalism. Is it O.K. if I read a very short passage that I just love from this book? It’s about a preacher who we get to know better later on, and his name is Papa Divina, and he has this epiphany. He’s on this kind of long comic journey across West Africa. We see him in Liberia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and he’s in Ghana, and he has this epiphany. He’s just kind of made this pun on the idea of a site of prophecy: a “prophesite.” And he says this:

He looked nervously around, hoping that no one else had caught that creative slip, or at least that it had not registered with anyone in that audience with apostolic ambitions. The flash momentarily unnerved him, as it inserted profound doubts in his mind––could it be that he was after all the genuine article? That he had indeed responded to an authentic call to prophecy? Prophesite! Why had all his predecessors failed to formulate such an exquisite, indeed mellifluous name for a place of spiritual quest? Could it be that he was, unbeknownst to himself till now, truly . . . called?

This person, who’s clearly a charlatan of a kind but almost convinces himself that he’s not, in certain ways: I wanted to talk to you just about this emphasis on fundamentalism. What role did that play for you?

You know, some of the greatest charlatans of religion, of the religious profession, are really very likable people, very lovable people. First of all, they’re performers. They enjoy performing. Now, if you enjoy what you’re doing, you’re a happy person, and you infect others with some of that happiness. So even while you are, you know, blabbering platitudes, knowing very well that you are conning your congregation, you do produce not just happiness; sometimes rapture—genuine, authentic rapture. And so I find them very complex people, the genuine religionists. Of course, some of them are just sinister—the fundamentalists, for instance, both of Christianity and of Islam. And Hinduism, for instance. All religions have their fundamentalist sectors, and those are really sinister, dangerous people. They have no sense of humor. They cannot see the pathetic side of life. They cannot even look at themselves in the mirror—and I give them a sort of pat on the back and say, “You charlatan, but today wasn’t bad.” They are incapable of it. Some of them just kill. They believe, that’s it—they kill anybody who doesn’t aspire to your level of malevolent conviction.

I’d love to talk to you about, you know, over the course of your career—and I feel that “career” is not as capacious a word as I want—you’ve been able to bring your activism and your intellectualism and your sort of art all onto the same plane, all operating at once. I learned that—and please correct me if I’m wrong—is Fela Kuti your cousin?

Fela Aníkúlápó, my cousin? Yes.

I had not known that, and it struck me as so apt, because here was another person whose art and intellect and political sense were all inter-implicated, all together. I wonder if just your upbringing made you feel that as a responsibility. Was that a natural step for you to be sort of an activist, politically aware, a true citizen in the deep sense of that word, and also an artist at the same time?

It remains a mystery to me, and why should it be a mystery? It’s because, basically, I would rather not be all these things. In other words, an activist. I ask myself, I don’t know how often, “How on earth did you get on this path? Why don’t you just stick to what you love, really love, doing?” Which is, writing bits of poetry, writing plays, directing plays, exchanging ideas, getting into arguments simply because we live, also, with abstractions, and anybody who believes in the essence of things, the theory of things, loves the discourse about it, and this I enjoy, which is why I’m also a teacher by profession. I would rather be doing all those things, honestly, but I end up using that expression of “closet masochist” for myself because I’m doing certain things which I know I would rather not be doing. But I also love my peace of mind, my tranquility, and I cannot attain that—that’s a contradiction—I know I cannot attain that if I have not attended to an issue, a problem, which I know is pernicious, which I know is manifesting itself in a dehumanizing way in others, whether human beings, environment—child abuse, for instance. So we’re not just talking about politics. We’re just talking about humanity—this is one of me. I get restless when I see such situations, and the only way I can attain that peace which I love so much, which I only very sparsely enjoy—that’s what drives one out again and again and again, using other means when once literature fails one, fails to address the issue. Then, of course, you have to address it frontally, physically, by whatever means.

I love how you just said that your pursuit of tranquility has in some ways required that you get yourself into trouble in these other ways—you know, it seems like there’s not much glory to be had among your own people when you are confronting them in this way. There’s a—it seems like a fraught position, just on a personal level. Have you made peace with that, or is it a constant?

It’s a constant. If I’m to be at peace with myself, I must confront the unacceptable from whichever side. Of course, the state has certain statutory responsibilities, so the state gets it more than the people themselves.

I love a quote in your book that there are two friends who really form the heart of this book, who are speaking at one point, and one of them delivers one of the book’s most affecting lines, for me. He says, “Something is broken. Beyond race. Outside colour or history. Something has cracked. Can’t be put back together.” That something, that sort of ineffable something that’s beyond all of the ideology and all of anything that we can put our finger to—I wonder if writing this book helped you put a name to that ineffable something. And have maybe the politics of the last few years helped you to identify or reconsider what it might be ?

You know, I’ve tried to put my finger on it, and I end up with a question: What is human? I think that’s what we’ve lost. It has gone on for too long, that condition of losing what is human, from the most profound aspects of our relationships to the most trivial. We lost what is human.

As a way to say goodbye, we mentioned Fela Kuti, your late cousin. Do you have a favorite song of his?

My favorite is “ Zombie .” The reason, actually, is one that is not appreciated by most people. That song, “Zombie,” applies not merely to the military in terms of their conduct to the people of this nation, but “Zombie”—and that is what Nigerians have not yet realized—they have become mimic people.

They act like zombies. They accept orders, even if those orders are intolerable. They develop habits that they should not develop. So when I hear “Zombie” I see not merely SARS [ the Nigerian Police Force’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad ], those murdering police. I see not merely the bullying soldiers. I see also what Nigerians have become. So I enjoy “Zombie” on many more levels than the average Nigerian does.

Thank you so much. This has been wonderful, and I really appreciate it.

You’re welcome. Thank you.

More New Yorker Conversations

- Rick Steves says hold on to your travel dreams.

- Carmelo Anthony still feels like he is proving himself.

- Katie Strang on how the sports media covers sexual abuse.

- Representative Joaquin Castro on the exclusion of Latinos from American media and history books.

- Moe Tkacik on the fight to rein in delivery apps.

- Christine Baranski knows that it is good to be scared.

- Sign up for our newsletter and never miss another New Yorker Interview.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Cressida Leyshon

By Hilton Als

‘At long last, Idunit!’ Wole Soyinka on his first novel in nearly 50 years

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

On the Shelf

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth

By Wole Soyinka Pantheon: 464 pages, $28 If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A new work by a Nobel laureate is generally a cause for celebration, but in Wole Soyinka ’s case, it’s especially significant. It’s been nearly 50 years since he published his last novel, “ The Interpreters , ” and though his work has spanned multiple genres — poetry, plays, memoirs and essays — his new novel, “ Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth ,” manages to chart fresh territory. At 87, the first sub-Saharan author to be honored by Stockholm remains a brilliant thinker and tinkerer. “Chronicles” combines elements of a murder mystery, a searing political satire and an “Alice in Wonderland”-like modern allegory of power and deceit.

The novel picks up just as Nigeria — or the author’s stand-in for his home country — is gearing up to celebrate its annual Festival of the People of Happiness, yet another example of official doublespeak. The ruling People on the Move Party (“POMP”) have turned the country into a vast, innocuous reality show even as violence, fanaticism and ruthless plunder wreak havoc across the land. But when Dr. Kighare Menka, famous for tending to the mutilated victims of Boko Haram , stumbles upon a black market in human body parts, the nation’s ugly secrets begin to surface.

And that’s just the beginning of the conspiracies, which stretch from a charlatan preacher named Papa Divina to the president, Sir Godfrey O. Danfere. The mysterious death of Menka’s blood-brother, Duyole Pitan-Payne — who came of age with Menka during the hopeful early years of independence — tightens the web of intrigue. What did he know? Who wanted him dead? And when, exactly, did Nigeria sink so low? These and other questions — personal, moral, social and political — percolate through Soyinka’s acidly comic take on his country’s “grim contest in human desecration, physical and mental.” Soyinka spoke with The Times via email about the new book, his homeland and his own legacy.

How the SoCal coast inspired a legendary author’s feminist Kenyan epic

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the 82-year-old Kenyan author and UC Irvine professor, was inspired to write “The Perfect Nine” by the “blue vastness” of the Pacific.

Oct. 12, 2020

I’m curious how long this book has been germinating and what about this story demanded the form of a novel.

Quite a while, certainly close to two decades. However, the themes found release in other forms, mostly polemical. Let’s say it found temporary outlet in my local interventions, both literary and political. So it had been building up in the mind. With that kind of pressure — rather like a flood behind a retaining wall — only the prose cascade seemed empowered to bear the burden of release.

Were there unexpected challenges in writing a novel again after so long?

Mostly technical. I work — like most — directly from my laptop. I am not a sequential writer, so each session does not necessarily take up the story where it left off. Now, imagine resuming work where you thought you had left your characters. The oftener you click that “save” button, the deeper you dig yourself into a hole — no, into several tunnels.

You started writing during the early days of the pandemic, outside your home in Nigeria . Was that out of necessity or preference?

No, I started work just before the pandemic. Needed to physically distance myself from the provoking environment to be able to address it, and in full isolation. Two sessions of about eight days each — one in Dakar, the other in Ghana — I needed those, to even begin. Then the pandemic locked me down in my own forested home, with just my characters for company. The heavy stuff took over, for some three or four months. Not a recommended regimen.

The title is meant facetiously, but it was inspired by an actual news report on Nigeria’s high rating on a global survey of optimism.

Sometimes, I even propose that the novel wrote itself, with the overpowering gamut of occurrences in manic vein. To encounter a report that this land, clinging to a marginal survival index, is rated high on the “happiness” scale — that scatters your brain! But, then, you also understand. Just recently, a carnival wedding party was staged. The bride was the president’s daughter, and over a hundred private jets flew in guests from every corner of the nation. I had foolishly imagined that the nation was in mourning, what with a thousand or so students still held captive by religious fundamentalist loonies and other homicidal maniacs.

This novel can be read in many ways, but, ultimately, it moves with the pace of a whodunit. Was that something you’ve wanted to try your hand at?

Always longed to write a mystery, no question about that. In secondary school, I ate up detective novels. Well, as “Chronicles” progressed, my long-repressed antennae sniffed an opening and that was it. Backtracked and did some lateral adjustments. So it’s been gratifying to receive comments of it being a kind of whodunit. At long last: Idunnit!

World & Nation

Nobel winner assails religious intolerance

Wole Soyinka of Nigeria calls faith this century’s defining issue and says fundamentalism is the greatest threat to world peace and democracy.

Jan. 27, 2007

How closely did you want to stick to the realities of present-day Nigeria and how much artistic license did you allow yourself?

Would be pointless to deny that I wanted Nigerians to recognize themselves in the work. Yes, it is consciously a J’Accuse of both power and the disempowered. And I drove my African publisher to distraction just so the work could emerge in time for Nigeria’s 60th independence anniversary last year. And guess what? The government announced that the celebrations would be spectacular and would run a full year! Mind you, the anniversary project was simply abandoned . Left to sink quietly in government sump.

You’ve been an outspoken critic of abuses of authority. You tore up your U.S. Green Card when Trump was elected in 2016. I’m interested in how you viewed the Black Lives Matter protests of this past year.

Black Lives Matter was long in coming, its tempo was merely crudely accelerated with the entry of Donald Trump and what he represented. It was psychic release. Trump was the revenge of American racism to the shock of unforgivable Obama. I hope, by the way, that “Chronicles” is seen as not simply a critique of one’s own government. It is meant to indict us also, the governed, as a people who have jettisoned the humane values that that same society impressed on my upbringing. Yes, I would give much to bludgeon Nigeria into accepting that Black Lives do Matter!

You’ve said before that winning the 1986 Nobel Prize brought with it a heavy burden — in a word, it was “hell.” But it has also given you a powerful platform. Is this something you’ve learned to embrace?

Do recall, I did have a “platform” even before the Nobel. I had and routinely exercised that voice. The Nobel, however, began to render the voice hoarse and brittle from expectations and demands. Worst of all was that I lost even my remnant shreds of anonymity. That’s the unrecognized part, and one to which I am yet to be reconciled.

As the first Black African Nobelist, you’ve also had an enormous impact on contemporary African writing. How do you think it’s changed in the past half-century?

Yes, the prize did instigate literary emulation — not imitation, thank goodness — manifested in bolder, self-assured writing among the younger African generation. That alone was gratifying. The young female writers especially.

Review: Two iconic novelists, Adichie and Lahiri, step off their pedestals

Two big novelists take sharp turns in new books: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie mourns in “Notes on Grief”; Jhumpa Lahiri writes a novel, “Whereabouts,” in Italian.

April 30, 2021

When you look back at your oeuvre, what works do you feel represent your greatest legacy?

No, no, I never think in terms of legacy. And I can truthfully claim that I am quite at home in any genre — from poetry to polemics. The theme calls to the medium, and one can only aspire to be a faithful conduit!

Tepper has written for the New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places.

More to Read

Opinion: Why would anyone want a paleo diet? We’re desperate for half-truths about human origins

March 30, 2024

A father goes missing. Then a brother too. In this ‘Great Forest,’ a fraught return home

Jan. 31, 2024

N. Scott Momaday, Pulitzer Prize winner and giant of Native American literature, dies at 89

Jan. 29, 2024

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

‘Rebel’ redacted: Rebel Wilson’s book chapter on Sacha Baron Cohen struck from some copies

April 25, 2024

The independent publisher making a business of celebrity book imprints

April 24, 2024

The week’s bestselling books, April 28

Doris Kearns Goodwin and husband Dick Goodwin lived, observed, created and chronicled the 1960s

- Skip to main content

- assistive.skiplink.to.breadcrumbs

- assistive.skiplink.to.header.menu

- assistive.skiplink.to.action.menu

- assistive.skiplink.to.quick.search

- Hit enter to search

- A t tachments (1)

- Page History

- Page Information

- Resolved comments

- View in Hierarchy

- View Source

- Export to PDF

- Export to Word

- Created by Yanping Zhang , last modified by Farheen Jehan Mukarram on May 08, 2015

Death and the King's Horseman - Wole Soyinka (1975)

Death and the King’s Horseman , a tragedy written by Wole Soyinka in 1975, shares an interpretation of the Yoruba religion and the unique view of the universe. In the Yoruba tradition, there are three worlds: the living, the dead, and the unborn. Soyinka’s play centers upon the interconnectivity between the three worlds and the way in which actors from the different worlds interact.

Plot Summary

As per Yoruba custom, when the chief of the community dies, Elesin Oba, the king’s horseman, must commit ritual suicide to ensure the chief’s spirit makes its way to the afterlife. Otherwise, the chief’s spirit will travel about Earth and wreak havoc upon the community. If the horseman does not die, this is a grave sign of disrupting the cosmic balance.

As the chief has just died, Act I follows Elesin Oba dancing and chanting through the market with his praise singers and drummers. Since it is his last day on Earth, Elesin Oba is given the privilege of any woman in the market place. He asks for a beautiful bride who is meant to marry Iyaloja’s son. After some convincing, Iyaloja accepts Elesin’s request and he is allowed a night with the bride.

Sergeant Amusa, a muslim, enters the home of District Officer, Simon Pilkings, to find him and his wife, Jane dancing while dressed in traditional Yoruba clothing. Amusa instructs them as to how disrespectful this act is to the Yoruba people. Amusa is shaken by the level of disrespect and unable to formulate sentences, decides to leave a note explaining the ritual Elesin is meant to before that night. The note is lost in translation and Pilkings does not completely understand what will be happening until further clarification from his servant, Joseph. Pilkings, a British colonial officer, intervenes with the ritual and tells Amusa to arrest Elesin to prevent him from committing suicide.

When Amusa arrives at the marketplace with a few constables to stop Elesin from engaging in the ritual, the women taunt them and force them to retreat without success. Elesin emerges from his chamber after consummating his marriage to the beautiful bride. The night continues with much singing and dancing in the marketplace.

At a masked ball at a British resident’s home, Pilkings receives word that Elesin was not successfully stopped. The resident admonishes Pilkings for not dealing with the matter properly. With Amusa still troubled by the sight of Simon’s manner of dress, Pilkings’ leaves to intervene with the ritual on his own.

Jane meets with Olunde, Elesin’s son who Simon helped travel to England for medical school. Jane and Olunde converse and Jane quickly realizes, much to her surprise, that Olunde has adopted a much more critical view of British culture and still very much believes in the Yoruba way of life. Olunde has come to fulfill his duty of burying his father since hearing the Chief died and knowing Elesin will be next. Jane is shocked that Olunde is not phased by the thought of his father’s death and does not wish to save him.

The sounds of the drums change and Olunde assumes this means Elesin has been killed. When Pilkings returns, Olunde attempts to explain to him that it is for the betterment of the community that Elesin die and is pleased that Pilkings was not able to obstruct the cosmic order.

Upon finding an angry Elesin captured, Olunde is ashamed of his father for not completing his duty. He tells Elesin he no longer has a father and storms away.

An imprisoned Elesin is troubled that he was unable to complete his duty since he is still fully committed to the task. He thinks through the recent events wondering whether to attribute his failure to the consummation of his marriage or the cosmos failing him.

Jane enters with Pilkings and convinces him to allow Iyaloja to speak with Elesin. Iyaloja and Elesin speak about the implications of his failure. Then the women bring in a cloth covered figure which Iyaloja uncovers to reveal Olunde’s dead body. Shamed by his father’s inability to complete his duty, Olunde sacrificed himself instead. Elesin reacts by strangling himself with his chains.

Iyaloja condemns Pilkings for misunderstanding and disrespecting the Yoruba tradition and blames him for how recent events have unfolded. She admonishes him for his last act of ignorance in trying to close Elesin’s eyes. As per Yoruba custom, Iyaloja calls over the bride to close and put dirt on Elesin’s eyelids.

Wole Soyinka's Biography

Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright and political activist who famously won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986.

Wole Soyinka graduated from Government College and University College in Ibadan in 1958 and then received a degree in English from the University of Leeds in England. He wrote his first play for the Nigerian independence celebrations, entitled A Dance of the Forests in 1960 and founded a theater company to perform it in 1963.

He attended Churchill College, Cambridge as a fellow in the 1970s where he would often walk past a statue of Wilston Churchill, the figure of British colonialism. Upon seeing the statue, he says: "I had an overwhelming desire," he says, smiling, "to push it and watch it crash." Soyinka attributes this as the spark which the lit the fuse for the many plays, novels, and poems he has authored since.

Even though his writing has largely been politically inspired in the past, he says if he had the choice, he admires those writers who remain in the purely creative realm.

Soyinka says he most identifies with the Yoruba diety, Ogun, who is the god of metals and poetry. He has been inspired by Ogun who Soyinka claims is a “demanding God”. Ogun is highly revered in Oyo, the city where Death and the King’s Horseman takes place. Ogun is believed to have been one of the first Gods to come to Earth and successively fought for the safety of its people.

British Colonial History

In 1893, the Yoruba kingdoms in Nigeria became part of the Protectorate of Great Britain. The British imperialists united many different groups within the Yoruba people and other ethnic and linguistic groups. Until 1960 Nigeria was a British colony and the Yoruba were British subjects. On October 1, 1960, Nigeria became an independent nation structured as a federation of states. The colonizers left their stamp on Nigeria by slowly dissolving Yoruban religious practices and s preading Christianity. Soyinka presents this slow process of marginalizing the Yorban way of life in the play as the British officers intervene and arrest Elesin to prevent him from completing his ritual suicide after the king's death.

Yoruba Culture

The Yoruba are a collection of diverse groups of people and they are one of the largest African ethnic groups south of the Sahara Desert. Yoruba practices are centered upon much ritual and behavioral symbolism. In Nigeria, they dominate the western part of the country. Particularly relevant to the context of this play is the role of the Yoruba during the centuries of the slave trade. The Yoruba territory was known as the Slave Coast where large numbers of the Yoruba were carried to the Americas.

Yoruba culture is fascinating and their language especially is crucial to the way in which Death and The King’s Horseman has been written. The language is a tonal one which means that the same combination of vowels and consonants can have different meanings depending on the pitch of the vowels (whether they are pronounced with a high voice or a low voice). This fact not only makes the play an interesting one to perform but also means that there are areas where reading the play is a very different experience to watching it being performed especially (as has been the case with many western productions of the play) when actors are not well aware of the Yoruba language and the importance of tonal variations. Soyinka has often stated that no actor can accurately do justice to the characters of this play due to the very difficult task of depicting the language and culture.

Masks are an aspect of Yoruba culture that is not very well understood by the outside world but form a major part of the play as well as Yoruba life to date. Traditionally and historically the masks have very different purposes and are specifically designed for these varying causes. Masks are sculptured and/or carved art pieces made out of wood, brass and occasionally terracotta. They are often worn by traditional healers and are believed to drive away evil spirits. Often masks are placed on shrines and in temples to honor the gods and ancestors. Often these masks are used in traditional ceremonies where they are worn during performances and spiritual acts. When not worn, these ma sks are kept in shrines where they are honored with libations and prayers. In the play, masks play a central role in demonstrating British ignorance and misunderstanding of the Yoruba people. The British officer Pilkings and his wife Jane do not understand the religious significance of these masks and offend Amusa when they choose to "tango" while wearing death masks.

There are several kinds of sculptures and art forms that the Yoruba consider important and that are at the heart of their culture and traditions.

Once such example is the Ibeji which refers to twins whose birth among the Yoruba is unusually frequent. An Ibeji statuette is made, if one twin dies. In the event of such an occurrence, this Ibeji remained with the surviving twin and was treated, fed, and washed as a living child. Their effigies, made on the instructions of the oracle, are among the most numerous of all classes of African sculpture and can be found very frequently in anthropology and historical collections all over the world.

The equestrian figure is another common theme in Yoruba wood sculpture. It reflects the importance of the cavalry in the campaigns of the kings who created the Oyo Empire as early as the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Since only Yoruba chiefs and their personal retainers were privileged to use the horse, the rider and the horse remained an important social symbol and offered an exciting subject for artists. Soyinka demonstrates this importance through the main character Elesin who is revered throughout the community as the king's horseman.

Life and Death

The opposing force of life and death is a major theme in the play. The entire text is concerned with the journey from one state of being (life) to the next (death) and Elesin’s failure is that he is unable to cross the bridge between these two worlds. For the Yoruba, death is another state of existence, transition into which is only natural and part of the circular cycle of being. Soyinka represents the circular cycle of being when the ritual is completed with death but another life is formed through the pregnancy of Elesin's young bride. Apart from the Yoruba, the British are also concerned with the theme of life and death - but for them, life is what one should aspire to while death is frightening because it signifies the end of one's journey. Throughout the play, Soyinka depicts them as struggling to understand the very different Yoruba outlook on life and death and it is this central misunderstanding which drives the story's conflict.

Ritual and tradition are very important throughout the play but the theme of sacrifice is particularly relevant. For instance, only through Elesin sacrificing himself can the ritual be completed and the cosmic balance be restored. Elesin struggles with this as he attempts to enjoy his last day of life before being stopped by the British imperialists. Ultimately, Olunde’s sacrifice of taking his own life is what restores harmony and order, making sacrifice central to the resolution of the play. This perspective on sacrifice is also important because it is incredibly unique and different from Christianity's view of sacrifice. The British view the Yoruba people's sacrifice as a monstrous act because in Christianity sacrifice or suicide is a grave sin. Therefore, it is difficult for Pilkings and Jane to understand and accept that sacrifice might be an appropriate way to die.

Honor is a major, dominant, and overarching theme in the play. Honor is a word that surrounds the actions of the tribal members of the Yoruba, especially with respect to customs, traditions, and rituals. Particularly, in Olunde’s interactions with Pilkings and his wife, Jane, we see honor, dignity and respect for his culture and traditions really come to light. He honors and defends the Yoruba way of life while conversing with an ignorant, Jane. Ultimately, Olunde feels a grave need to honor his father as well as the community and carry out the ritual suicide that his father has been unable to do. Additionally, Elesin must honor his community as well as uphold his own honor by carrying out the ritual suicide which ensures the king's soul may rest peacefully. Not only would this compromise his honor, but it would also upset the cosmic order and jeopardize the future of his community.

Anti-colonialism

European imperialism is present in the play from the beginning to end and there is a constant struggle between the western rulers and the local Yoruba people both culturally and politically. Elesin and Pilkings represent this theme perfectly where they both have duties and responsibilities towards the people but have a very different outlook and relationship with the local population. Pilkings's duty is to enforce the laws of the English colonial empire in Africa, which means not allowing the supposedly "barbaric" customs like the king's horseman ritual to continue. The clash between Olunde and Jane further represents British opposition to Yoruba values. While Jane expects Olunde to have assimilated and adopted the British culture and worldview, Olunde instead argues in favor of Yoruba customs and openly accepts his father's imminent death. Although Olunde attempts to explain the Yoruba point of view, the British continue to demonstrate a stubborn unwillingness to understand a different way of life.

The play also presents the theme of anti-colonialism by highlighting the impact the imperials can have on a culture. It was important for Soyinka to explicate that Yoruba culture is something that is ever changing and evolving. It is not stagnant and “stuck in the past” as the British colonizers have perceived it. Simply because the culture is unlike that of British civilization does not mean that the Yoruba people are somehow backwards or uncivilized. Instead, they have adopted a way of life which was born of a different way of thinking about and perceiving the world.

Drama and Performance

Playbill Cover for Death and the King's Horseman at Vivian Beaumont Theater