Have Fun With History

Common Sense by Thomas Paine – Significance and Influence

“Common Sense” by Thomas Paine is a timeless and influential pamphlet that played a pivotal role in shaping the course of history.

Published in 1776 during the American Revolution, Paine’s persuasive writing and revolutionary ideas captivated the minds of the American colonists, sparking a fervent call for independence from British rule.

This brief exploration delves into the significance of “Common Sense,” its impact on the American Revolution, its role in fostering unity among the colonies, and its enduring influence on political thought both in the United States and beyond.

The Significance of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

1. advocated for american independence.

“Common Sense” was a groundbreaking pamphlet published by Thomas Paine in 1776, during a critical time in American history. Paine’s central argument was for the complete independence of the American colonies from British rule.

Also Read: Thomas Paine Timeline

He eloquently and passionately challenged the notion of a hereditary monarchy and questioned the legitimacy of the British monarchy’s authority over the distant colonies.

Paine argued that it was only natural for the American people to govern themselves, free from the control of a distant and unresponsive government across the Atlantic.

2. Played a crucial role in the American Revolution

The publication of “Common Sense” had an extraordinary impact on the American Revolution. At the time of its release, there was considerable debate within the colonies regarding the path they should take in response to British policies.

Also Read: Thomas Paine Facts

Paine’s pamphlet struck a chord with the general public, as it presented a compelling case for outright independence. The pamphlet was widely read and discussed, reaching people from all walks of life, including ordinary citizens, soldiers, and political leaders.

“Common Sense” helped galvanize public sentiment and mobilized support for the revolutionary cause. It provided a clear and powerful argument for why breaking away from British rule was not only justified but necessary for the preservation of liberty and self-determination.

3. Influenced the formation of the United States as a democratic republic

Beyond advocating for independence, “Common Sense” also laid out Paine’s vision for a new form of government for the American colonies.

Paine promoted the idea of a democratic republic, where the power to govern would be vested in the hands of the people, rather than in the hands of a monarch or ruling elite.

His ideas helped to shape the thinking of the Founding Fathers, such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, who played instrumental roles in drafting the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

Paine’s call for a government based on the consent of the governed and the protection of individual rights echoed throughout the founding documents of the United States, making a lasting impact on the country’s political structure and principles.

4. Written in a clear and accessible style

One of the key reasons for the immense impact of “Common Sense” was Thomas Paine’s ability to convey complex political ideas in a clear and straightforward manner.

Unlike many other political writings of the time, which were often dense and filled with formal language, Paine wrote in simple and accessible prose. He deliberately used everyday language that could be easily understood by common people, ensuring that his arguments reached a wide audience.

This approach was revolutionary in itself, as it made political discourse more inclusive and helped bridge the gap between the educated elite and ordinary citizens.

Paine’s writing style set a precedent for future political communication, emphasizing the importance of clarity and accessibility in conveying ideas to the masses.

5. Widely distributed throughout the American colonies

Despite the limited means of communication and printing technology in the 18th century, “Common Sense” achieved remarkable distribution and dissemination.

Paine initially published the pamphlet anonymously, but its authorship was soon revealed. It was printed and distributed in various cities and towns throughout the American colonies.

Due to its affordable price and easy-to-read format, many copies were sold and shared among people from all walks of life.

The pamphlet’s widespread availability ensured that its message reached a vast audience and contributed to its significant influence on public opinion. Paine’s work also inspired others to write responses and engage in a broader public debate about independence and self-governance.

6. Popularized republican ideology

“Common Sense” played a crucial role in popularizing republican ideals among the American colonists. Paine argued for a government based on the consent of the governed and advocated for the abolishment of monarchy and aristocracy.

He proposed a representative democracy, where elected officials would act in the best interest of the people and uphold their rights and freedoms. Paine’s promotion of these republican principles resonated with many colonists who were seeking a new and just form of government.

His ideas reinforced the belief that the power to govern should come from the people themselves, not from a distant and unaccountable monarchy.

This popularization of republican ideology helped solidify the concept of sovereignty residing with the people and contributed to the formation of democratic institutions in the emerging United States.

7. Contributed to the drafting of the Declaration of Independence

The ideas presented in “Common Sense” had a profound influence on the thinking of the Founding Fathers, many of whom were already sympathetic to the cause of independence. Thomas Paine’s arguments reinforced their beliefs and provided additional support for the case for separation from Britain.

Some of Paine’s language and concepts found their way into the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted on July 4, 1776.

Notably, the Declaration emphasized the principles of natural rights, the consent of the governed, and the right to alter or abolish an oppressive government, ideas that were already prominent in “Common Sense.”

While Paine himself was not directly involved in the drafting of the Declaration, his pamphlet played a significant role in shaping the intellectual climate that led to its creation.

8. Fostered unity among the American colonies

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, the thirteen colonies were diverse in terms of their backgrounds, economies, and political structures. They did not always see eye-to-eye on matters of governance and resistance to British policies.

“Common Sense” helped bridge these divides and fostered a sense of unity among the colonies. By providing a coherent argument for independence and republican government, Paine encouraged the colonies to work together in their struggle against British rule.

The pamphlet made the case that the shared cause of independence was more important than any regional differences or disagreements. As a result, “Common Sense” played a vital role in consolidating the colonies’ efforts and building a collective sense of identity that would prove crucial during the American Revolution.

9. Enduring influence on political thought

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” remains an enduring and celebrated work in the history of political thought. Its impact extended far beyond the American Revolution.

The pamphlet’s articulation of democratic principles, advocacy for independence, and criticisms of monarchy and tyranny have continued to inspire generations of thinkers, politicians, and activists around the world.

Paine’s ideas on the rights of individuals and the legitimacy of government have become foundational concepts in political theory and have shaped discussions on governance, liberty, and democracy for centuries. “Common Sense” stands as a testament to the power of persuasive writing and the ability of one individual to profoundly influence the course of history.

10. Inspired independence movements worldwide

Beyond its impact on the American Revolution and the formation of the United States, “Common Sense” had a broader influence on the global stage. Translations and excerpts of the pamphlet spread to other countries, inspiring independence movements and political revolutions in various parts of the world.

Paine’s ideas on the rights of people to govern themselves and the need to challenge oppressive authority resonated with individuals and groups seeking freedom and self-determination in different contexts. “Common Sense” became a symbol of the transformative power of ideas, inspiring movements for liberty and independence throughout the ages and across continents.

A Summary and Analysis of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

After the Declaration of Independence, probably the most important and influential document of the American Revolution was a short pamphlet written not by an American, but by an English writer who had been living in America for less than 15 months.

But although his country of birth was the very nation – Britain – that Americans were fighting against to secure their independence, Thomas Paine was most of the most significant supporters of the American cause.

And Americans were clearly ready to hear what he had to say. Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense , published at the beginning of that momentous year, 1776, rapidly became a bestseller, with an estimated 100,000 copies flying off the shelves, as it were, before the year was out.

Indeed, in proportion to the population of the colonies at that time – a mere 2.5 million people – Common Sense had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history, before or since. Common Sense , it turns out, was fairly common – and very popular.

But what made Paine’s pamphlet of some 25,000 words and 47 pages strike such a chord with Americans in 1776? Why did Paine write Common Sense , and what exactly does the pamphlet say? Before we offer an analysis of this landmark text, here’s a summary of Paine’s argument.

Paine’s pamphlet is a polemical work, so he is not setting out to offer a balanced and even-handed appraisal of the facts. Instead, he views his role as that of rabble-rouser, stoking the fires of revolution in the heart of every American living under British rule in the Thirteen Colonies.

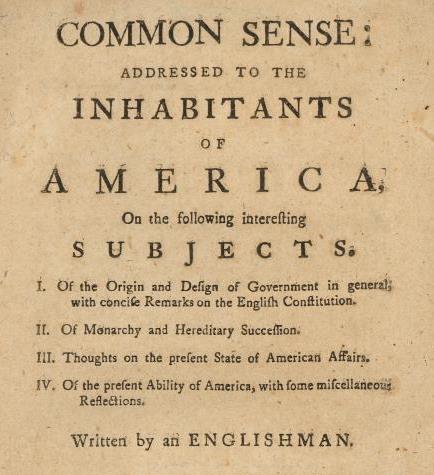

Common Sense is divided into four parts. In the first part, ‘On the Origin and Design of Government in General, with Concise Remarks on the Constitution’, Paine considers the role of government in abstract terms. For Paine, government is a ‘necessary evil’ because it keeps individuals in check, when their inner ‘evil’ might otherwise break out.

Paine then considers the English constitution, established in 1689 in the wake of the Glorious Revolution . The main problem is that England has monarchy and aristocratic power written into its constitution: the monarchy is a hereditary privilege which the individual king or queen has done nothing personally to ‘earn’, and the same is true of those who sit in the House of Lords and participate in government. (Paine was against all forms of hereditary power, believing the individual should earn whatever role they have.)

In the second part, Paine considers monarchy from a biblical perspective and a historical perspective. Aren’t all men equal when they are created? In that case, the idea that one man – calling himself king – is greater than his subjects, who are but his fellow men, is flawed. He cites various passages from the Old and New Testaments in support of his argument.

For example, he discusses 1 Samuel 8 in which God punishes the people for asking for a king. ‘That the Almighty hath here entered his protest against monarchical government is true,’ Paine argues, ‘or the scripture is false.’ And few of Paine’s God-fearing readers would believe that the Bible could be false in what it showed.

Next, Paine turns from the biblical to the historical argument against monarchical government, point out how past kings have been problematic: for example, the Wars of the Roses lasted for decades and kept England in a state of turmoil as two warring royal houses fought for control of the kingdom. ‘In short,’ Paine concludes, ‘monarchy and succession have laid (not this or that kingdom only) but the world in blood and ashes.’

Finally, Paine also attacks the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke ’s notion of a ‘mixed state’, a kind of constitutional monarchy where the monarch has limited powers. For Paine, this isn’t enough: most monarchs who wish to seize more power for themselves will find a way of doing so.

The third part of Common Sense , ‘Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs’, looks at the conflict between Britain and the American colonies, arguing that independence is the most desirable outcome for America. He proposes a Continental Charter which would lead to a new national government, which would take the form of a Congress. He then outlines the form that this would take (each colony, divided into smaller districts, who send delegates to Congress to represent them).

In the fourth and final section of the pamphlet, ‘On the Present Ability of America, with Some Miscellaneous Reflections’, Paine turns to the practicalities of fighting the British, both in terms of money and resources.

He draws attention to America’s strong military potential. Shipyards can be used to provide the timber to create a navy that could rival Britain’s. Economically, too, America is in a strong position because it has no national debt.

Before he arrived in America in 1774, Thomas Paine had a fine series of failures behind him: a onetime corset-maker and customs officer born in Norfolk in 1737, he travelled to the American colonies after Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in London, put in a good word for him.

Paine was soon editing the Pennsylvania Magazine , and in late 1775 began writing Common Sense , which would rapidly cause a sensation throughout the Thirteen Colonies. George Washington wrote to a friend in Massachusetts, ‘I find that Common Sense is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men’.

What was it about Paine’s pamphlet that caused such a stir? It was partly good timing: anti-British feeling had been growing in the last few years, especially since Britain introduced a range of taxes in 1763 to help fund their wars in Europe and India; such a tax famously led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and the British retaliation that swiftly followed.

Nevertheless, in 1775 many Americans living within the Thirteen Colonies still favoured reconciliation with their British overlords. Put simply, many people didn’t have enough enthusiasm to go to war against such a powerful imperial nation as Britain. But Thomas Paine sensed that the appetite for a fight was there, if only someone could stir the populace to action; and he knew the right way to get the ordinary man and woman on side.

So Paine needed to do more than simply lay out the situation to such people. He needed to persuade them by showing in powerful and vivid language that Britain was a power-hungry imperial force under whose boot Americans were always going to suffer – unless, that is, they decided enough was enough.

With Common Sense , Paine helped to win over many of those waverers to the cause for independence. He did this, most of all, not by appealing to scholarly argument or intellectual reasoning but by going for the emotions of his readers (and listeners: many people gathered together to hear someone else read aloud from Paine’s essay). We should bear in mind the ‘common’ part of ‘common sense’: Paine was trying to reach everyone, regardless of education or social rank.

Painting the British king, George III, as a tyrannical power-hungry ruler who had overstepped the mark, Paine made the case against monarchical rule and in favour of democratic government. When Common Sense lit the touchpaper for revolution, Paine was more than prepared to put his money where his mouth is, too. He enlisted in the American army in July 1776 and continued to write pamphlets to boost morale throughout the years of bloody war that followed.

Common Sense was popular in America, but it was also translated into French and was eagerly taken up there. Indeed, Paine’s revolutionary call for an anti-monarchical system of government would later help to inspire the French Revolution in 1789, which Paine supported in its early stages. But it was in America that his revolutionary zeal first galvanised others to fight for independence from the monarch who ruled over them.

Fittingly, it was Thomas Paine, writing under the byline ‘Republicus’ in June 29, 1776, who became the first person to make a public declaration for the new country to be named the ‘United States of America’. An Englishman from rural Norfolk had helped to inspire countless Americans to make their country their own.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

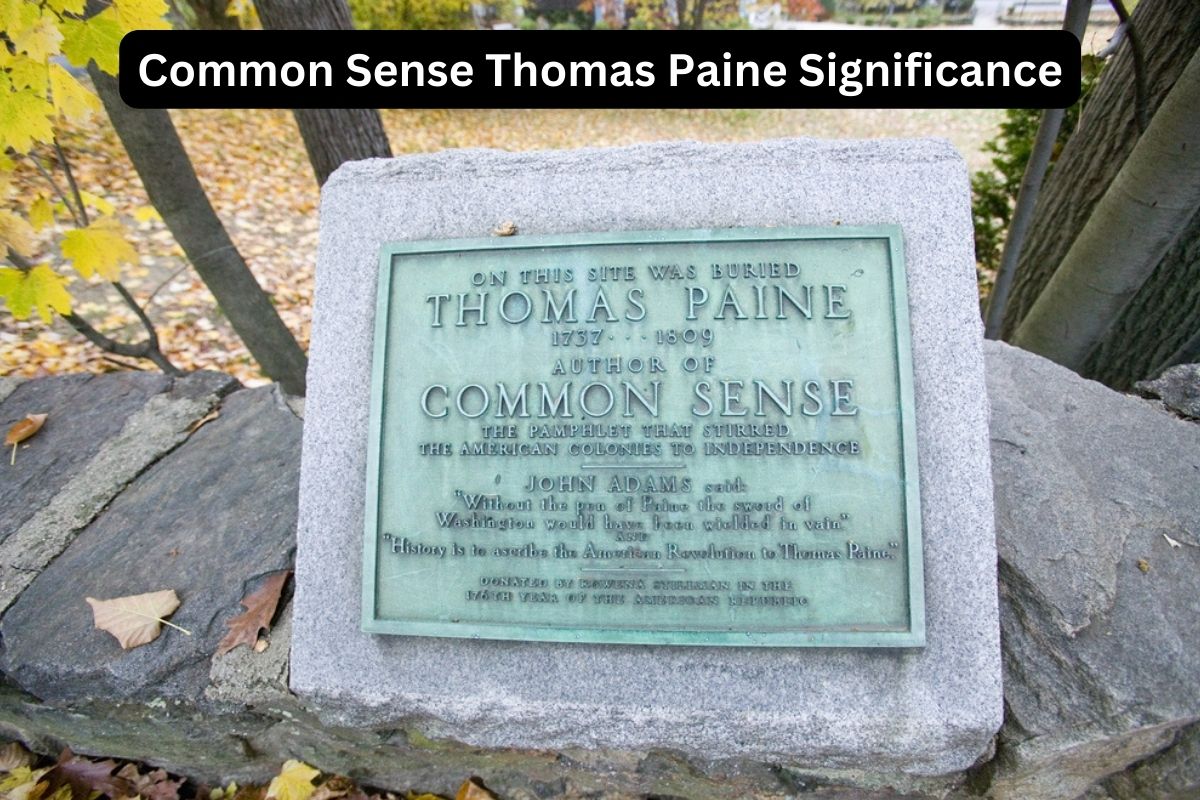

January 10 marks the anniversary of the publication of Thomas Paine’s influential Common Sense in 1776.

On January 10, 1776, an obscure immigrant published a small pamphlet that ignited independence in America and shifted the political landscape of the patriot movement from reform within the British imperial system to independence from it.

One hundred twenty thousand copies sold in the first three months in a nation of three million people, making Common Sense the best-selling printed work by a single author in American history up to that time.

Never before had a personally written work appealed to all classes of colonists. Never before had a pamphlet been written in an inspiring style so accessible to the “common” folk of America.

A government of our own is our natural right…Ye that oppose independence now, ye know not what ye do; ye are opening a door to eternal tyranny, by keeping vacant the seat of government.

Common Sense made a clear case for independence and directly attacked the political, economic, and ideological obstacles to achieving it. Paine relentlessly insisted that British rule was responsible for nearly every problem in colonial society and that the 1770s crisis could only be resolved by colonial independence. That goal, he maintained, could only be achieved through unified action.

Hard-nosed political logic demanded the creation of an American nation. Implicitly acknowledging the hold that tradition and deference had on the colonial mind, Paine also launched an assault on both the premises behind the British government and on the legitimacy of monarchy and hereditary power in general. Challenging the King’s paternal authority in the harshest terms, he mocked royal actions in America and declared that “even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their own families.”

Finally, Paine detailed in the most graphic, compelling and recognizable terms the suffering that the colonies had endured, reminding his readers of the torment and trauma that British policy had inflicted upon them.

Yuval Levin on the Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left

but from the errors of other nations, let us learn wisdom, and lay hold of the present opportunity—To begin government at the right end…

Resources on Thomas Paine and Common Sense

The complete writings of thomas paine.

Project Gutenberg provides the compilation of Thomas Paine’s writings online, including Common Sense , The American Crisis , Rights of Man , and the controversial The Age of Reason . Shorter pieces include private letters to Thomas Jefferson and a letter criticizing the American government and George Washington .

Thomas Paine Friends, Inc.

Thomas Paine Friends, Inc., an association dedicated to an increased public awareness of Paine’s political contributions, provides several articles and resources for further reading on this lesser known founder.

Jon Katz on Paine’s Life and Influence on Journalism

In an article for Wired , Jon Katz provides a narrative of Thomas Paine’s life and argues that Paine should be recognized as the moral father of the internet and a pioneer of journalism.

John Adams on Thomas Paine

Although Common Sense proved to be an influential piece of American political thought, John Adams did not think much of it, nor of its author: “The Arguments in favor of Independence I liked very well: but one third of the Book was filled with Arguments from the old Testament, to prove the Unlawfulness of Monarchy, and another Third, in planning a form of Government, for the separate States in One Assembly, and for the United States, in a Congress.”

How The American Crisis Saved the Revolution

Common Sense may be the best-known of Paine’s writings, but another of his pamphlets, The American Crisis , was critical in rallying the patriots to a victory at Trenton in late 1776. Paine’s The American Crisis contains the famous quote: “ These are the times that try men’s souls : The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph .”

In addition to the audacity and timeliness of its ideas, Common Sense compelled the American people because it resonated with their firm belief in liberty and determined opposition to injustice. The message was powerful because it was written in relatively blunt language that colonists of different backgrounds could understand.

Paine, despite his immigrant status, was on familiar terms with the popular classes in America and the taverns, workshops, and street corners they frequented. His writing was replete with the kind of popular and religious references they readily grasped and appreciated. His strident indignation reflected the anger that was rising in the American body politic. His words united elite and popular strands of revolt, welding the Congress and the street into a common purpose.

As historian Scott Liell argues in Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence : “[B]y including all of the colonists in the discussion that would determine their future, Common Sense became not just a critical step in the journey toward American independence but also an important artifact in the foundation of American democracy” (20).

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Common Sense and the political thought of Thomas Paine

Seth Cotlar, “Thomas Paine in the Atlantic Historical Imagination.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Seth Cotlar, Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Trans-Atlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic . (University of Virginia Press, 2011)

Seth Cotlar, “Tom Paine’s Readers and the Making of Democratic Citizens in the Age of Revolutions.” ( Thomas Paine: Common Sense for the Modern Era , San Diego State University Press, 2007)

Armin Mattes, “Paine, Jefferson, and the Modern Ideas of Democracy and the Nation.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Eric Nelson, “Hebraism and the Republican Turn of 1776: A Contemporary Account of the Debate over Common Sense.” ( The William and Mary Quarterly 70.4, October 2013)

Peter Onuf (editor), Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions . (University of Virginia Press, 2014)

William Parsons, “Of Monarchs and Majorities: Thomas Paine’s Problematic and Prescient Critique of the U.S. Constitution. ” ( Perspectives on Political Science 43.2, 2014)

Gordon Wood, “The Radicalism of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine Considered.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Michael Zuckert, “Two paths from Revolution: Jefferson, Paine and the Radicalization of Enlightenment Thought.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

…But where says some is the King of America? I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the charter; let it be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.

If you are a JMC Scholar who’s published on the Fourteenth Amendment and would like your work included here

Stay up to date with the jack miller center.

Sign up for one of our newsletters!

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : January 10

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Thomas Paine publishes “Common Sense”

On January 10, 1776, writer Thomas Paine publishes his pamphlet “Common Sense,” setting forth his arguments in favor of American independence. Although little used today, pamphlets were an important medium for the spread of ideas in the 16th through 19th centuries.

Originally published anonymously, “Common Sense” advocated independence for the American colonies from Britain and is considered one of the most influential pamphlets in American history. Credited with uniting average citizens and political leaders behind the idea of independence, “Common Sense” played a remarkable role in transforming a colonial squabble into the American Revolution .

At the time Paine wrote “Common Sense,” most colonists considered themselves to be aggrieved Britons. Paine fundamentally changed the tenor of colonists’ argument with the crown when he wrote the following: “Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither they have fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still.”

Paine was born in England in 1737 and worked as a corset maker in his teens and, later, as a sailor and schoolteacher before becoming a prominent pamphleteer. In 1774, Paine arrived in Philadelphia and soon came to support American independence. Two years later, his 47-page pamphlet sold some 500,000 copies, powerfully influencing American opinion. Paine went on to serve in the U.S. Army and to work for the Committee of Foreign Affairs before returning to Europe in 1787. Back in England, he continued writing pamphlets in support of revolution. He released “The Rights of Man,” supporting the French Revolution in 1791-92, in answer to Edmund Burke’s famous “Reflections on the Revolution in France” (1790). His sentiments were highly unpopular with the still-monarchal British government, so he fled to France, where he was later arrested for his political opinions. He returned to the United States in 1802 and died in New York in 1809.

Also on This Day in History January | 10

This Day in History Video: What Happened on January 10

First meeting of the United Nations

League of nations instituted, gusher signals new era of u.s. oil industry, president harding orders u.s. troops home from germany, president johnson asks for more funding for vietnam war.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

FDR introduces the lend‑lease program

Outlaw frank james born in missouri, aol‑time warner merger announced, avalanche kills thousands in peru, world’s cheapest car debuts in india.

America in Class Lessons

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776

By Wason, Marianne (NHC Assistant Director of Education Programs, Online Resources, 1997–2014)

By January 1776, the American colonies were in open rebellion against Britain. Their soldiers had captured Fort Ticonderoga, besieged Boston, fortified New York City, and invaded Canada. Yet few dared voice what most knew was true — they were no longer fighting for their rights as British subjects. They weren’t fighting for self-defense, or protection of their property, or to force Britain to the negotiating table. They were fighting for independence. It took a hard jolt to move Americans from professed loyalty to declared rebellion, and it came in large part from Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. Not a dumbed-down rant for the masses, as often described, Common Sense is a masterful piece of argument and rhetoric that proved the power of words.

Political Science / History / Education Studies / American Revolution / American History / Rhetoric / Primary Sources /

- The Columbian Exchange

- De Las Casas and the Conquistadors

- Early Visual Representations of the New World

- Failed European Colonies in the New World

- Successful European Colonies in the New World

- A Model of Christian Charity

- Benjamin Franklin’s Satire of Witch Hunting

- The American Revolution as Civil War

- Patrick Henry and “Give Me Liberty!”

- Lexington & Concord: Tipping Point of the Revolution

- Abigail Adams and “Remember the Ladies”

- Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” 1776

- Citizen Leadership in the Young Republic

- After Shays’ Rebellion

- James Madison Debates a Bill of Rights

- America, the Creeks, and Other Southeastern Tribes

- America and the Six Nations: Native Americans After the Revolution

- The Revolution of 1800

- Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase

- The Expansion of Democracy During the Jacksonian Era

- The Religious Roots of Abolition

- Individualism in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”

- Aylmer’s Motivation in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”

- Thoreau’s Critique of Democracy in “Civil Disobedience”

- Hester’s A: The Red Badge of Wisdom

- “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

- The Cult of Domesticity

- The Family Life of the Enslaved

- A Pro-Slavery Argument, 1857

- The Underground Railroad

- The Enslaved and the Civil War

- Women, Temperance, and Domesticity

- “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint,” 1873

- “To Build a Fire”: An Environmentalist Interpretation

- Progressivism in the Factory

- Progressivism in the Home

- The “Aeroplane” as a Symbol of Modernism

- The “Phenomenon of Lindbergh”

- The Radio as New Technology: Blessing or Curse? A 1929 Debate

- The Marshall Plan Speech: Rhetoric and Diplomacy

- NSC 68: America’s Cold War Blueprint

- The Moral Vision of Atticus Finch

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense , 1776

Advisor: Robert A. Ferguson , George Edward Woodberry Professor in Law, Literature and Criticism, Columbia University, National Humanities Center Fellow. Copyright National Humanities Center, 2014

Lesson Contents

Teacher’s note.

- Text Analysis & Close Reading Questions

Follow-Up Assignment

- Student Version PDF

How did Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense convince reluctant Americans to abandon the goal of reconciliation with Britain and accept that separation from Britain — independence — was the only option for preserving their liberty?

Understanding.

By January 1776, the American colonies were in open rebellion against Britain. Their soldiers had captured Fort Ticonderoga, besieged Boston, fortified New York City, and invaded Canada. Yet few dared voice what most knew was true — they were no longer fighting for their rights as British subjects. They weren’t fighting for self-defense, or protection of their property, or to force Britain to the negotiating table. They were fighting for independence. It took a hard jolt to move Americans from professed loyalty to declared rebellion, and it came in large part from Thomas Paine’s Common Sense . Not a dumbed-down rant for the masses, as often described, Common Sense is a masterful piece of argument and rhetoric that proved the power of words.

Literary nonfiction; persuasive essay. In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Text Complexity

Grades 9-10 complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org .

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.6 (Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how an author uses rhetoric to advance that point of view or purpose.)

Advanced Placement US History

- 3.2 (IB) (Republican forms of government found expression in Thomas Paine’s Common Sense .)

Advanced Placement English Language and Composition

- Reading nonfiction

- Analyzing and identifying and author’s use of rhetorical strategies

This lesson focuses on the sections central to Paine’s argument in Common Sense — Section III and the Appendix to the Third Edition, published a month after the first edition. We do not recommend assigning the full essay (Sections I, II, and IV require advanced background in British history that Paine’s readers would have known well). However, students should be led through an overview of the essay to understand how Paine built his arguments to a “self-evident” conclusion (See Background: Message , below.)

Lead students through an initial overview of the essay (see Background ). To begin, they could skim the full text and read the pull-quotes (separated quotes in large bold text). What impression of Common Sense do the quotes provide? What questions do they prompt? Then guide students as they read (perhaps aloud) Section III of Common Sense and the Appendix to the Third Edition (pp. 10-19 and 25-29 in the full text provided with this lesson).

Proceed to the close reading of three excerpts in the Text Analysis below. (Note that part of Excerpt #3 is a Common Core exemplar text.)

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, access to the interactive exercises, and a follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive worksheet that can be e-mailed, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions.

| (continues below) | (click to open) |

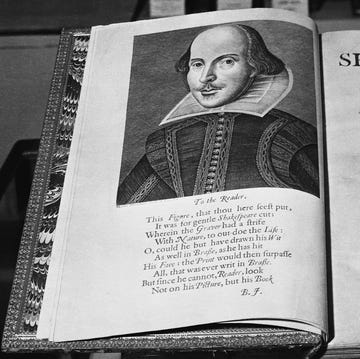

Teacher’s Guide

The man at right does not look angry. To us, he projects the typical figure of a “Founding Father” — composed, elite, and empowered. And to us his famous essays are awash in powdered-wig prose. But the portrait and the prose belie the reality. Thomas Paine was a firebrand, and his most influential essay — Common Sense — was a fevered no-holds-barred call for independence. He is credited with turning the tide of public opinion at a crucial juncture, convincing many Americans that war for independence was the only option to take, and they had to take it now , or else.

Common Sense appeared as a pamphlet for sale in Philadelphia on January 10, 1776, and, as we say today, it went viral. The first printing sold out in two weeks and over 150,000 copies were sold throughout America and Europe. It is estimated that one fifth of Americans read the pamphlet or heard it read aloud in public. General Washington ordered it read to his troops. Within weeks, it seemed, reconciliation with Britain had gone from an honorable goal to a cowardly betrayal, while independence became the rallying cry of united Patriots. How did Paine achieve this?

“Sometime past the idea [of independence] would have struck me with horror. I now see no alternative;… Can any virtuous and brave American hesitate one moment in the choice?” The Pennsylvania Evening Post , 13 February 1776

“We were blind, but on reading these enlightening works the scales have fallen from our eyes…. The doctrine of Independence hath been in times past greatly disgustful; we abhorred the principle. It is now become our delightful theme and commands our purest affections. We revere the author and highly prize and admire his works.” The New-London [Connecticut] Gazette , 22 March 1776

2. Message.

What made Common Sense so esteemed and “enlightening”? Some argue that Common Sense said nothing new, that it simply put the call-to-war in fiery street language that rallied the common people. But this trivializes Paine’s accomplishment. He did have a new message in Common Sense — an ultimatum. Give up reconciliation now, or forever lose the chance for independence. If we fail to act, we’re self-deceiving cowards condemning our children to tyranny and cheating the world of a beacon of liberty. It is our calling to model self-actualized nationhood for the world. “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.”

Paine divided Common Sense into four sections with deceptively mundane titles, mimicking the erudite political pamphlets of the day. But his essay did not offer the same-old-same-old treatise on British heritage and American rights. Here’s what he says in Common Sense :

Introduction : The ideas I present here are so new that many people will reject them. Readers must clear their minds of long-held notions, apply common sense, and adopt the cause of America as the “cause of all mankind.” How we respond to tyranny today will matter for all time. Section One : The English government you worship? It’s a sham. Man may need government to protect him from his flawed nature, but that doesn’t mean he must suffocate under brute tyranny. Just as you would cut ties with abusive parents, you must break from Britain. Section Two : The monarchy you revere? It’s not our protector; it’s our enemy. It doesn’t care about us; it cares about Britain’s wealth. It has brought misery to people all over the world. And the very idea of monarchy is absurd. Why should someone rule over us simply because he (or she) is someone’s child? So evil is monarchy by its very nature that God condemns it in the Bible. Section Three : Our crisis today? It’s folly to think we should maintain loyalty to a distant tyrant. It’s self-sabotage to pursue reconciliation. For us, right here, right now, reconciliation means ruin. America must separate from Britain. We can’t go back to the cozy days before the Stamp Act. You know that’s true; it’s time to admit it. For heaven’s sake, we’re already at war! Section Four : Can we win this war? Absolutely! Ignore the naysayers who tremble at the thought of British might. Let’s build a Continental Navy as we have built our Continental Army. Let us declare independence. If we delay, it will be that much harder to win. I know the prospect is daunting, but the prospect of inaction is terrifying.

A month later, in his appendix to the third edition, Paine escalated his appeal to a utopian fervor. “We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he insisted. “The birthday of a new world is at hand.”

3. Rhetoric.

“It is necessary to be bold,” wrote Paine years later on his rhetorical power. “Some people can be reasoned into sense, and others must be shocked into it. Say a bold thing that will stagger them, and they will begin to think.” 4 Keep this idea front and center as you study Common Sense .

As an experienced essayist and a recent English immigrant with his own deep resentments against Britain, Paine was the right man at the right time to galvanize public opinion. He “understood better than anyone else in America,” explains literary scholar Robert Ferguson, “that ‘style and manner of thinking’ might dictate the difficult shift from loyalty to rebellion.” 5 Before Paine, the language of political essays had been moderate. Educated men wrote civilly for publication and kept their fury for private letters and diaries. Then came Paine, cursing Britain as an “open enemy,” denouncing George III as the “Royal Brute of England,” and damning reconciliation as “truly farcical” and “a fallacious dream.” To think otherwise, he charged, was “absurd,” “unmanly,” and “repugnant to reason.” As Virginian Landon Carter wrote in dismay, Paine implied that anyone who disagreed with him “is nothing short of a coward and a sycophant [stooge/lackey], which in plain meaning must be a damned rascal.” 6 Paine knew what he was doing: the pen was his weapon, and words his ammunition. He argued with ideas while convincing with raw emotion. “The point to remember,” writes Ferguson, “is that Paine’s natural and intended audience is the American mob…. He uses anger, the natural emotion of the mob, to let the most active groups find themselves in the general will of a republican citizenry.” 7 What if Paine had written the Declaration of Independence with the same hard-driving rhetoric?

AS JEFFERSON WROTE IT: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. IF PAINE HAD WRITTEN IT: NO man can deny, without abandoning his God-given ability to reason, that all men enter into existence as equals. No matter how lowly or majestic their origins, they enter life with three God-given RIGHTS — the right to live, to right to live free, and the right to live happily (or, at the least, to pursue Happiness on earth). Who would choose existence on any other terms? So treasured are these rights that man created government to protect them. So treasured are they that man is duty-bound to destroy any government that crushes them — and start anew as men worthy of the title of FREE MEN. This is the plain truth, impossible to refute.

Text Analysis

Close reading questions.

Imagine yourself sitting down to read Common Sense in January 1776. How does Paine introduce his reasoning to you? He announces that his logic will be direct and down to earth, using only “simple facts” and “plain arguments” to explain his position, unlike (he implies) the complex political pamphlets addressed to the educated elite. His audience would understand “common sense” to suggest the moral sense of the yeoman farmer, whose independence and clear-headedness made him a more reliable guardian of national virtue (similar to Jefferson’s agrarian ideal).

Why does he write “I offer nothing more” instead of “I offer you many reasons” or “I offer a detailed argument”? “Nothing more” implies that Common Sense will be easy to follow, presenting only what is necessary to make his argument. (Paine considered titling his essay Plain Truth .)

How does Paine ask you to prepare yourself for his “common sense” arguments? Be willing to put aside pre-conceived notions, he says, and judge his arguments on their own merits.

What does he imply by saying a fair reader “will put on , or rather than he will not put off , the true character of a man”? He implies that any reader who would refuse to consider his arguments is narrow-minded. With the “on”–”off” contrast, he suggests that you, the individual reader, are open-minded and thus a fellow man of honor willing to consider a new point of view.

PARAGRAPH 55

With the hyperboles, how does Paine lead you to view the “cause” of American independence? View it, he says, from an overarching global perspective, not the narrow perspective of American colonists in the late 1700s. The hyperboles are ultimates — the most worthy of worthy causes, affecting the future now and forever . The American cause can lead mankind toward enlightened self-determination, driving forward the progress of civilization. Paine says this directly in his introduction: “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.” We’re not just talking taxes and representation, people.

What tone does Paine add with the phrases “The sun never shined” and “even to the end of time”? A biblical and prophetic tone. The sun shining down on human endeavors suggests divine endorsement of the American cause — a cause that will bring light and freedom (“salvation”) to the world. Resisting the cause, Paine implies, would be resisting divine will.

Let’s consider Paine as a wordsmith. How does he use repetition to add impact to the first part of the paragraph? He includes two repetitive sets: 1. “’Tis not” to begin sentences 2 and 3 [anaphora] 2. the phrases “of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom” and “of a day, a year, or an age” [prepositions with multiple objects]. Read the section aloud to hear the insistent rhythm that elevates Paine’s prose to a rousing call to action (his goal in writing Common Sense ).

Paine ends this paragraph with an analogy: What we do now is like carving initials into the bark of a young oak tree. What does he mean with the analogy? A. This is the time to create a new nation. Our smallest efforts now will lead to enormous benefits in the future. B. This is the time to unite for independence. Discord among us now will escalate into future crises that could ruin the young nation. Answer: B. The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ’Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent – of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed time of continental [colonies’] union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

PARAGRAPH 58

What sound repetitions do you find? Alliteration: ar gument/ ar ms/ ar ea/ ar isen p lans/ pr oposals/ pr ior/A pr il Consonance: politi cs /stru ck me th od/ th inking/ha th m atter/argu m ent/ar m s

Read the sentences aloud. What impact does the repetition add to Paine’s delivery? A stirring oratorical rhythm is achieved, like that of a solemn speech or sermon meant to convey the truth and gravity of an argument.

Paine compares the attempts to reconcile with Britain after the Battle of Lexington and Concord to an old almanac. What does he mean? He means the idea of reconciliation is now preposterous and that no rational person could support it. No one would use last year’s almanac to make plans for the current year! Also, as an almanac ceases to be useful at a specific moment (midnight of December 31), Paine implies that reconciliation ceased to be a valid goal at the moment of the first shot on April 19, 1775. (Paine often alludes to aspects of colonial life, like almanacs, that would resonate with all readers. They include references to farming, tree cutting, hunting, land ownership, slavery, biblical scripture, family and neighbor bonds, maturation, and the parent-child relationship; see “The Metaphor of Youth” below.) By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new area for politics is struck; a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, etc., prior to the nineteenth of April, i.e., to the commencement of hostilities [Lexington and Concord], are like the almanacs of the last year which, though proper [accurate] then, are superseded and useless now. Whatever was advanced by the advocates on either side of the question then, terminated in one and the same point, viz. [that is], a union with Great Britain. The only difference between the parties was the method of effecting it — the one proposing force, the other friendship; but it hath so far happened that the first hath failed and the second hath withdrawn her influence.

With this in mind, what tone does he lead the reader to expect: cynical, impatient, hopeful, reasonable, impassioned, angry? Reasonable. The two sentences resemble the opening of a legal argument that promises a balanced appraisal of two options on the basis of known evidence (“principles of nature”) and honest ordinary reasoning (“common sense”).

How does his tone prepare the resistant reader? Paine means to deflect challenges of bias or extremism by inviting readers to give him a hearing. “If I’m being fair in my writing, you can try to be fair in your listening.”

While Paine promises a fair appraisal, look how he describes the two options in the last sentence. Option 1: “if separated” from Britain Option 2: “if dependent on Britain” Why didn’t he use the usual terms for the two options — “independence” and “reconciliation”? First, INDEPENDENCE and RECONCILIATION sound like equally plausible options, but Paine wants to convince you that independence is the only acceptable option. If so, then why did he choose SEPARATION instead of INDEPENDENCE? By January 1776, INDEPENDENCE carried the drastic connotations of war and treason. It was an irrevocable decision with unknown consequences. In contrast, SEPARATION seems less drastic, and even positive. In human development, separation from one’s parents is the natural and long-sought step to full adulthood. That’s the self-image Paine wants to foster in his readers. Are we adults or children? [See the activity below, “The Metaphor of Youth”.]

In this vein, Paine chose DEPENDENCE instead of RECONCILIATION for Option 2 (staying with Britain). RECONCILIATION suggests the calm and rational agreement of two grownups, but Paine wants you to view reconciliation as the defeatist choice of spineless subjects who could never take care of themselves. In other words, DEPENDENCE.

[Note: Paine does call the two options “independence” and “reconciliation” elsewhere in Common Sense , but he meant to avoid them here.] As much hath been said of the advantages of reconciliation, which, like an agreeable dream, hath passed away and left us as we were, it is but right that we should examine the contrary [opposing] side of the argument and inquire into some of the many material injuries which these colonies sustain, and always will sustain, by being connected with and dependent on Great Britain. To examine that connection and dependence, on the principles of nature and common sense, to see what we have to trust to [expect] if separated, and what we are to expect if dependent.

PARAGRAPH 60

Here Paine rebuts the first argument for reconciliation—that America has thrived as a British colony and would fail on her own. How does he dismiss this argument? He slams it down hard. “NOTHING can be more FALLACIOUS,” he yells. The argument is beyond misdirected or short-sighted, he insists; it’s a fatal error in reasoning. So much for calm and reasoned debate. But Paine is not having a temper tantrum in print. His technique was to argue with ideas while convincing with emotion.

Paine follows his utter rejection of the argument with an analogy. Complete the analogy: America staying with Britain would be like a child _______. “America staying with Britain would be like a child remaining dependent on its parents forever and never growing up.” And who would want that, Paine implies? By writing “first twenty years of our lives” instead of, say, “first five years,” Paine alludes to the general consensus that a twenty-year-old is an adult.

Paine goes one step further in the last sentence. What does he say about America’s “childhood” as a British colony? He “answers roundly” (with conviction) that the colonies’ growth was actually hampered by being part of a European empire. They would have been more healthy and successful “adults,” he insists, if they had not been the “children” of the British empire. This was a radical premise in 1776, but one that buttressed Paine’s argument for independence I have heard it asserted by some that as America hath flourished under her former connection with Great Britain, that the same connection is necessary towards her future happiness, and will always have the same effect. Nothing can be more fallacious than this kind of argument. We may as well assert that because a child has thrived upon milk, that it is never to have meat, or that the first twenty years of our lives is to become a precedent for the next twenty. But even this is admitting more than is true; for I answer roundly that America would have flourished as much, and probably much more, had no European power had anything to do with her.

PARAGRAPH 61

Here Paine challenges his opponents to bring “reconciliation to the touchstone of nature.” What does he mean? (A “touchstone” is a test of the quality or genuineness of something. From ancient times the purity of gold or silver was tested with a “touchstone” of basalt stone.) Test the chances of reconciliation against what you know about people’s reactions in similar crises throughout history, not against your own hopes and fears during this particular crisis. In other words, use common sense.

At the start of this paragraph Paine mildly faults the supporters of reconciliation as unrealistic optimists “still hoping for the best.” By the end of the paragraph, however, they are cowards willing to “shake hands with the murderers.” How did he construct the paragraph to accomplish this transition? He poses two challenges to the supporters of reconciliation. If they can honestly answer each challenge, he asserts, and still support reconciliation, then they are selfish cowards bringing ruin to America.

Paraphrase the first challenge (sentences 2–5). “Ask yourself if you can remain loyal to a nation that has brought war and suffering to you. If you say you can, you’re fooling yourself and condemning us to a worse life under Britain than we suffer now.”

Paraphrase the second challenge (sentences 6–11). “Have you been the victim of British violence? If you haven’t, then you still owe compassion to those who have. And if you have, yet still support reconciliation, then you have abandoned your conscience.”

With what phrase does Paine condemn those who would still hope for reconciliation even if they were victims of British violence? They are men who “can still shake hands with the murderers,” i.e., men who have betrayed their fellow Americans and thus become as evil as the British invaders. There is no nuance in this condemnation, and thus no way for the reader to avoid its implications.

Note how Paine weaves impassioned questions through the paragraph: “Are you only deceiving yourselves?” “Have you lost a parent or a child by their hands?” How do these questions intensify his challenges? Addressed to “you” directly and not a faceless “he or they,” the questions deliver an in-your-face challenge that allows no escape. Here’s my question to you: Answer it! or your silence will reveal your cowardice.

Rewrite sentences #4 and #11 to change the second-person “you” to the third-person “he/she/they.” How does the change weaken Paine’s challenges? The reader is off the hook. Since the challenges are deflected from “you,” the reader, to the third-person “other,” no immediate personal reply is demanded. The reader can blithely read on and avoid the aim of Paine’s questions.

PARAGRAPH 77

At this point, Paine pleads with his readers to write the constitution for their independent nation without delay. What danger do they risk, he warns, if they leave this crucial task to a later day? A colonial leader could grasp dictatorial power by taking advantage of the postwar disorder likely to result if the colonies have no constitution ready to implement. Even if Britain tried to regain control of the colonies, it could be too late to wrest control back from a powerful dictator. “Ye are opening a door to eternal tyranny,” Paine warns, “by keeping vacant the seat of government.”

What historical evidence does Paine offer to illustrate the danger? He states that “some Massanello may hereafter arise” and grasp power, alluding to the short-lived people’s revolt led by the commoner Thomas Aniello (Masaniello) in 1647 against Spanish control of Naples (Italy). The Spanish ruler granted a few rights, but Masaniello was soon murdered, ending the uprising and its short-lived gains for the people.

As his plea escalates in intensity, Paine exclaims “Ye that oppose independence now, ye know not what ye do.” To what climactic moment in the New Testament does he allude? While suffering on the cross before his death, Jesus calls out, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23: 34); that is, his crucifiers do not know they are killing the Son of God. With this compelling allusion (which most readers would instantly recognize), Paine warns that opposing independence is as calamitous a decision for Americans as killing Jesus was for his executioners and for mankind.

Paine heightens his apocalyptic tone as he appeals to “ye that love mankind” to accept a mission of salvation (alluding to Christ’s mission of salvation). What must the lovers of mankind achieve in order to save mankind? They must establish the “free and independent States of America” as the sole preserve of human freedom in the world. A desperate fugitive, “freedom” has been “hunted” and “expelled” throughout the world, and it is America’s mission to protect and nurture her. America’s victory will be mankind’s victory, not just the feat of thirteen small colonies in a distant corner of the world.

NOTE: “A government of our own is our natural right” asserts Paine at the beginning of this excerpt. Six months later Thomas Jefferson asserted the same right in the opening of the Declaration of Independence. This Enlightenment ideal anchored revolutionary initiatives in America and Europe for decades.

O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her.—Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

* Thomas Anello, otherwise Massanello, a fisherman of Naples, who after spiriting up his countrymen in the public marketplace against the oppression of the Spaniards, to whom the place was then subject, prompted them to revolt, and in the space of a day become King. [footnote in Paine]

PARAGRAPHS 104, 107

- Write a how-to essay on persuasive writing using Common Sense as the focus text and this statement by Thomas Paine as the core idea: “Some people can be reasoned into sense, and others must be shocked into it. Say a bold thing that will stagger them, and they will begin to think.” –Letter to Elihu Palmer, 21 February 1802.

Quotation Para. Metaphor “The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth.” 58 light, newness, glory “The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries “‘TIS TIME TO PART.” 73 massacre, suffering “Reconciliation is now a fallacious dream.” 79 illusion, vain hope “It is now in the interest of America to provide for herself.” 144 adulthood, self-reliance “Independence is the only BOND that can tie and keep us together.” 163 tying cord, unity for survival

- See colonists’ and newspapers’ responses to Common Sense in the primary source collection Making the Revolution (Section: Common Sense?) to examine how Paine turned public opinion in 1776. Note the critical pieces by John Adams, Hannah Griffitts, and others. What can be learned about Paine’s effectiveness by studying his critics?

Vocabulary Pop-ups

[including 18th-c. connotations]

- posterity : all future generations of mankind

- superseded : replaced something old or no longer useful

- precedent : an action or policy that serves as an example or rule for the future

- touchstone : as a metaphor, a test of the quality or genuineness of something. (in the past, the purity of gold or silver was tested with a “toughstone” of basalt stone.)

- relapse : a return to a previous worse condition after a period of improvement

- sycophant : someone who acts submissively to another in power in order to gain advantage; yes-man, flatterer, bootlicker

- precariousness : uncertainty, instability; dependence on chance circumstances or unknown conditions

- deluge : a cataclysmic flood

1. Benjamin Franklin, letter to Silas Deane, 27 August 1775. Full text in Founders Online (National Archives). ↩ 2. Elbridge Gerry, letter to James Warren, 26 March 1776. ↩ 3. John Adams, autobiography, part 1, “John Adams,” through 1776, sheet 23 of 53 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive . Massachusetts Historical Society. www.masshist.org/digitaladams/. ↩ 4. Thomas Paine, letter to Elihu Palmer, 21 February 1802; cited in Henry Hayden Clark, “Thomas Paine’s Theories of Rhetoric,” Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters , 28 (1933), 317. ↩ 5. Robert A. Ferguson, “The Commonalities of Common Sense ,” William and Mary Quarterly , 3d. Series, 57:3 (July 2000), 483. ↩ 6. Landon Carter, diary entry, 20 February 1776, recounting content of letter written that day to George Washington. Full entry in Founders Online (National Archives). ↩ 7. Robert A. Ferguson, The American Enlightenment , 1750-1820 (Harvard University Press, 1994; paper ed., 1997), 113. ↩

*For a helpful discussion of Paine’s response to the “horrid cruelties” of the British in India, see J.M. Opal, “ Common Sense and Imperial Atrocity: How Thomas Paine Saw South Asia in North America, ” Common-Place , July 2009.

Images courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Library.

- Portrait of Thomas Paine by John Henry Bufford (1810-1870), engraving by Bufford’s Lithography, ca. 1850. Record ID 268504.

- Title page (cover) of Common Sense , 1776. Record ID 2052092.

National Humanities Center | 7 T.W. Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 | Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 | Fax: (919) 990-8535 | nationalhumanitiescenter.org

Copyright 2010–2023 National Humanities Center. All rights reserved.

- University Archives

- Special Collections

- Records Management

- Policies and Forms

- Sound Recordings

- Theses and Dissertations

- Selections From Our Digitized Collections

- Videos from the Archives

- Special Collections Exhibits

- University Archives Exhibits

- Research Guides

- Current Exhibits

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Past Exhibits

- Camelot Comes to Brandeis

- Special Collections Spotlight

- Library Home

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections

Thomas paine's common sense, 1776.

Description by Kenneth Hong, Brandeis undergraduate and special contributor to the Special Collections Spotlight.

“Common Sense,” published on January 10, 1776, was originally printed in the city of Philadelphia, but was soon reprinted across America and Great Britain, and translated into German and Danish. [1] Thomas Paine’s pamphlet was first published anonymously, due to fears that its contents would be construed as treason; it was simply signed, “by an Englishman”. [2] The version housed at Brandeis University is one of the London printings, which had hiatuses, where words and phrases were omitted that were offensive to the British crown. [3] “Common Sense” sold about 120,000 copies in the first three months alone, being read in taverns and meeting houses across the 13 original colonies (the U.S. Census Bureau estimates the population in 1776 to be about 2.5 million and today to be about 320 million, that would make it proportionally equivalent to selling 15,000,000 copies today!) [4]

Paine used his writing as his weapon against the crown. With masterful language, Paine united the will of the colonists, planting the seed and giving hope and inspiration to fulfill the dream of America as an independent nation. The pamphlet was originally published without his name and all of the royalties associated with “Common Sense” were donated to the Continental Army. [9] It would appear that Paine was looking for neither fame nor fortune in writing a pamphlet that profoundly affected the creation of a nation. To Paine, these ideas came naturally, they were simply, “Common Sense.”

August 2 , 2015

- Powell, Jim. “ Thomas Paine, Passionate Pamphleteer for Liberty ,” in The Freeman, January 1, 1996. Foundation for Economic Education. Accessed March 11, 2015.

- Ibid .

- Entry for Call# D793.P147c . Brown University Library Online Catalog. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Harvey Kaye. “ Common Sense and the American Revolution. ” The Thomas Paine National Historical Association. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- “ Praise for Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776 as Reported in American Newspapers, ” in “America in Class: Making the Revolution: America, 1763-1791: Primary Source Collection.” The National Humanities Center. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Paine, Thomas. Common Sense. London: J. Almon, 1776.

- Kaye, Accessed February 10, 2015.

This essay, by Brandeis undergraduate Kenneth Hong, resulted from a Spring 2015 course for the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program, taught by Dr. Craig Bruce Smith, entitled, “Preserving Boston’s Past: Public History and Digital Humanities.” In this course, students worked with archival materials, developed website content, and produced their own commemoration event, “The 250th Anniversary of the Stamp Act: A Revolutionary Exhibit and Performance,” marking one of the first steps of the American Revolution.

The Transitional Year Program was established in 1968 and was renamed in 2013 for Myra Kraft ‘64, the late Brandeis alumna and trustee. It provides small classes and strong support systems for students who have had limitations to their precollege academic opportunities.

- About Our Collections

- Online Exhibits

- Events and In-Person Exhibits

- From the Brandeis Archives

Ohio State navigation bar

- BuckeyeLink

- Search Ohio State

Common Sense: Thomas Paine and American Independence

Lesson plan.

Core Theme:

Grade: , ohio academic content standards:, primary source used:, summary: , estimated duration of lesson:, instructional steps:.

2. Pass out the

Post Assessment

Estimated duration of lesson: , summary of lesson:, instructional steps of lesson: , post assessment: .

Common Sense by Thomas Paine

As 1776 began, America’s rebellion against British colonial rule was not yet a revolution. Less than half the projected number of volunteers had enlisted in the Continental army with desertions mounting. George Washington was entrenched, but stalemated in Cambridge outside of Boston. The British Commander, General John Burgoyne, mocked the situation by writing and producing the satirical play, “The Blockade”, which portrayed Washington as an incompetent flailing a rusty sword. Then something amazing happened.

“Common Sense” was published on January 9, 1776. It remains one of the most indispensable documents of America’s founding. In forty-eight pages, Thomas Paine accomplished three things fundamental to America. He is the first to publically assert the only possible outcome of the rebellion is independence from Great Britain. He makes the case for American independence understandable and accessible to everyone. He lays the ground work for the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Paine is both the most unlikely and likely person to accomplish this pivotal Trifecta. He was born in rural England on January 29, 1737, the son of a Quaker father and an Anglican mother. This religious diversity formed a key part of his early writings on religious freedom. His career was a mixture of failed business ventures, failed marriages, and minor positions in British Excise (tax) offices. This mix of mundane activities masked the brilliant mind of an outstanding observer, thinker, and communicator.

In the summer of 1772, Paine wrote his first political article, The Case of the Officers of Excise , a twenty-one page brief for better pay and working conditions among Excise Officers. The work had little impact on Parliament, but did bring him to the attention of political thinkers in London, and ultimately to being introduced to Benjamin Franklin in September 1774. Franklin recommended that Paine immigrate to Pennsylvania and commence a publishing career. Thomas Paine arrived in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774 and became editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine in January 1775.

Editing the magazine gave Paine two major opportunities. He honed his writing skills for appealing to a mass audience and he befriended those opposing British colonial rule, including Benjamin Rush, an active member of the Sons of Liberty. After open rebellion erupted in April 1775, Rush was concerned that, “When the subject of American independence began to be agitated in conversation, I observed the public mind to be loaded with an immense mass of prejudice and error relative to it”. He urged Paine to make the case for American independence understandable to common people.

Common Sense was just that. Paine laid out methodical and easily understood reasons for American independence in plain terms. Up until Common Sense those opposed to British rule did so only in lengthy philosophical letters circulated among intellectual elites.

Common Sense ushered in a new style of political writing, devoid of Latin phrases and complex concepts. Historian Scott Liell asserts in Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence : “[B]y including all of the colonists in the discussion that would determine their future, Common Sense became not just a critical step in the journey toward American independence but also an important artifact in the foundation of American democracy.”

Paine’s simple prose promoted the premise that the rebellion was not about subjects wronged by their monarch, but a separate and independent people being oppressed by a foreign power:

“Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither they have fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still.” Common Sense was an instant bestseller. It sold as many as 120,000 copies in the first three months, 500,000 in twelve months, going through twenty-five editions in the first year alone. This amazingly wide distribution was among a free population of only 2 million Americans.

Originally published anonymously as “Written by an Englishman”, word soon spread that Paine was the author. His authorship known, Paine publically declared that all proceeds would go to the purchase of woolen mittens for Continental soldiers. General Washington ordered Paine’s pamphlet distributed among all his troops. Within the year, Paine became an aide-de-camp to Nathanael Greene, one of Washington’s top field commanders.

Common Sense was not only read by the masses, it was read to them. In countless taverns and local gatherings Paine’s case for American independence and for a unique American form of government was heard even by common folk who had never learned to read.

The masses heard and embraced the concept that, “A government of our own is our natural right”. They also heard and understood the foundations of America: Government as a “necessary evil” formed and maintained by the will of the governed – “in America THE LAW IS KING. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King”; and the need for an engaged electorate, “this frequent interchange will establish a common interest with every part of the community, they will mutually and naturally support each other, and on this, (not on the unmeaning name of king,) depends the strength of government, and the happiness of the governed.”

While the Declaration of Independence became the philosophical core of our Revolution, Common Sense initiated and broadened the public debate about independence, building the public commitment necessary to make our Revolution possible.

March 11, 2013 – Essay #16

Read Common Sense by Thomas Paine here: https://constitutingamerica.org/?p=3523

Scot Faulkner is Co-Founder of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics, Shepherd University. Follow him on Twitter @ScotFaulkner53

Maybe it’s time for a refresher course on “Common Sense”. That might be the spark that is needed to reclaim our Nation and remind those in office that government is through the consent of the governed. Unless the governed today don’t mind the near tyrannical government threatening our freedoms.

Remembering why America happened is about the underlying principles as well as the pivotal events, people, and documents. Our civic culture is at risk because so few people take the time to read and understand who we are.

This may be the heart of our national problem; “The more simple any thing is, the less liable it is to be disordered, and the easier repaired when disordered.” Our government has grown into such a complex monster that “we have to pass a law to find out what’s in it” and even then, no one can really understand what’s in it. Every reasonable citizen knows what the problems are, but it’s no longer easy to repair because there are so many advocates and beneficiaries for thousands of programs that it’s almost impossible to solve even one of the well-known problems without upsetting a large percentage of the citizens.

We need another “Common Sense” today. Even with it, we would need to reprint another set of Federalist Papers in language so simple that even those who buy into the Progressive agenda might understand how far that agenda is from the optimal structure that our founders left for us – and how that agenda is a path to destruction of our Republic. It reminds me of the book “Pilgrim’s Progress;” since our Republic’s journey began more than 200 years ago, we’ve found so many appealing paths to follow that we now have no idea how to get back to the path we were on. All these side paths seem so satisfying for the present that we don’t understand that we’ll never reach our ultimate, most satisfying, destination if we allow ourselves to keep getting diverted. We Constitutionalists have a lot of work to do!

We need another “Common Sense” today. Even with it, we would need to reprint another set of Federalist Papers in language so simple that even those who buy into the Progressive agenda might understand how far that agenda is from the optimal structure that our founders left for us – and how that agenda is a path to destruction of our Republic.

Many conservatives seem to think liberals are intellectually deficient compared to conservatives, but such egoism can only serve as a basis for grave strategic and tactical errors. Liberals don’t believe in absurdities because of any lack of intellectual capacity, but because their thinking has become emotionalized as a result of the increasing feminization of the American body politic.

Ron you are correct. America needs a 21st Century version of “Common Sense” to remind us that our founding principles are timeless and still very relevant today. This document also needs to make people aware of the fundamental threats to these principles (both foriegn and domestic).

I loved this guest essay! And, how very prescient his words are 200 plus years later…it seems that many of our culture’s failings have arisen out of this conflict between society and government with reference to their respective roles. Post modern America has bought into the same old lies as those in merry old England. Thomas Paine seemed to know and embrace “truth”…sadly, America has exchanged the “truth” for self-actualization and a culture of blame.

America needs another Thomas Paine – a person who can clearly communicate basic truths and make a compelling case for preserving our core principles of lberty.