We Trust in Human Precision

20,000+ Professional Language Experts Ready to Help. Expertise in a variety of Niches.

API Solutions

- API Pricing

- Cost estimate

- Customer loyalty program

- Educational Discount

- Non-Profit Discount

- Green Initiative Discount1

Value-Driven Pricing

Unmatched expertise at affordable rates tailored for your needs. Our services empower you to boost your productivity.

- Special Discounts

- Enterprise transcription solutions

- Enterprise translation solutions

- Transcription/Caption API

- AI Transcription Proofreading API

Trusted by Global Leaders

GoTranscript is the chosen service for top media organizations, universities, and Fortune 50 companies.

GoTranscript

One of the Largest Online Transcription and Translation Agencies in the World. Founded in 2005.

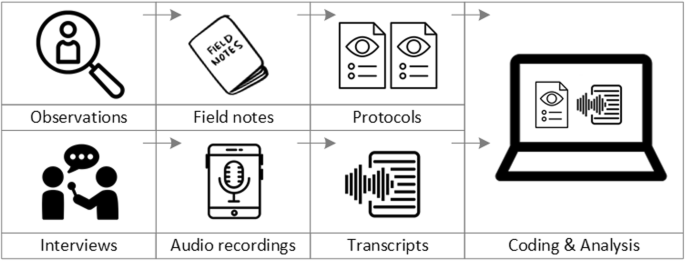

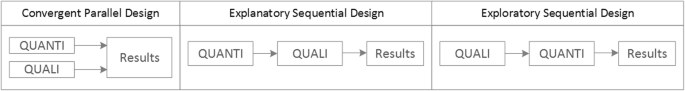

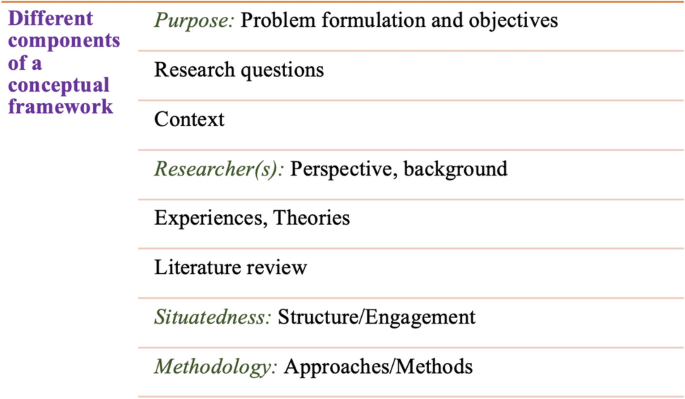

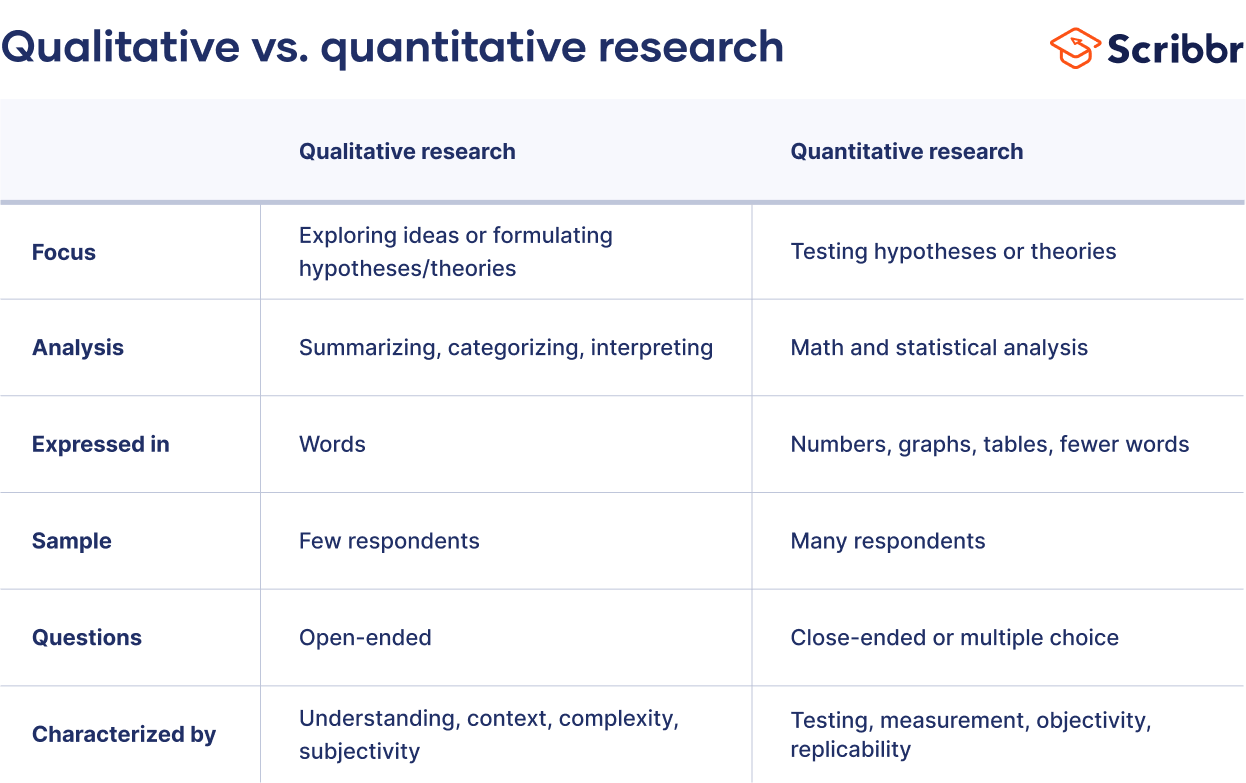

Speaker 1: In this video, we're going to unpack the oftentimes misunderstood topic of qualitative content analysis. We'll explain what it is, discuss its strengths and weaknesses, and look at when to use this analysis method. By the end of this video, you'll have a solid big picture view of content analysis so that you can make a well-informed decision for your project. By the way, if you're currently working on a dissertation, thesis, or research project, be sure to grab our free dissertation templates to help fast-track your write-up. These tried and tested templates provide a detailed roadmap to guide you through each chapter, section by section. If that sounds helpful, you can find the link in the description below. So, what exactly is content analysis? Well, at the simplest level, content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on analyzing recorded communication taken from artifacts. For example, extracts from books, newspaper articles, interviews, audio and video recordings, or even blogs. Importantly, content analysis can be used on both primary and secondary data. In other words, data you collected yourself or data that was already in existence. This makes it quite a flexible qualitative analysis method as you have more choices in terms of data sources. By the way, if you're new to qualitative analysis, be sure to check out our primer video up here. Now, let's go a little deeper. At the highest level, there are two types of content analysis, or rather, two ways to perform content analysis. These are conceptual content analysis and relational content analysis. These two approaches are quite different in terms of how they work, so let's take a look at each of them. First up is conceptual content analysis. In this case, the analysis is focused on the explicit data. You look at the actual appearance of particular words and phrases without offering interpretation of them. So, the main concern here is the frequency of words and phrases. In other words, the number of times they appear in the selected data set. For example, you might be researching changes in attitudes to women's rights issues. In this case, you could look at the frequency of words like equal pay, gender equality, and patriarchy in popular culture over a certain period of time. So, in short, conceptual content analysis is explicit, non-interpretational, and surface-level focused. It's also somewhat quantitative in nature. In other words, it considers some numbers, even though it's still a qualitative analysis method at its core. Next up is relational content analysis. Here, the focus is on the meaning and the use of words and phrases. This meaning is derived from looking at the relationships between the various words and phrases to those around them. Contrary to conceptual analysis, the one we just looked at, the focus here is on the implicit data, or the information interpreted from looking at how certain words are used in relation to others. For example, if a research project is aimed to analyze polling data around a particular political candidate to understand general sentiment, relational content analysis could be used to look at the words used around mentions of that candidate, for example, ethical, trustworthy, dubious, etc. to determine patterns and themes of meaning that could indicate popularity and sentiment. So, in short, relational content analysis is implicit, interpretational, and is focused on meaning. It's also worth mentioning that there are multiple approaches to relational analysis, but we won't dig into them in this introductory video. If you're interested, you can check out our detailed blog post covering all of that. The link is in the description. To recap then, content analysis can be undertaken using either a conceptual approach, where you're interested in the frequency of concepts, or a relational approach, where you're interested in the meaning of language based on the connections, or relationships, between words and phrases. Now that we have a clearer picture of what content analysis is, it's important to discuss the strengths and weaknesses so that you can make the right choice in terms of analysis methods for your research project. One of the main strengths of content analysis is its flexibility, as it can be used on a wide range of data types, including written records, interview recordings, and speech transcripts, as well as non-text-based data. This means you have more choices in terms of the data sources you can draw on, allowing you to develop a rich dataset. Additionally, content analysis tends to be very unobtrusive, since quite often, the analysis can be performed on data that already exists. This means that there are fewer ethical issues to consider, and it's easier to access the data you need. All that said, as with any analysis method, content analysis has its drawbacks. First, there's the problem of reliability. After all, drawing conclusions from the frequency of words and phrases, or their relationship to each other, can be a subjective process, and not quite scientifically rigorous enough. This is especially true if more than one researcher is working on the dataset. Content analysis can also sometimes be considered as rather reductive. In other words, the focus on particular words and phrases can of course result in you missing context, nuance, and culture-specific meanings. Lastly, the results from a content analysis can't usually be easily generalized. Since content analysis is often time-intensive, it can be difficult to analyze a dataset large enough to draw broad conclusions about the research topic. Of course, this can be said for many qualitative methods, but it's worth keeping in mind if you're considering using content analysis. Hey, if you're enjoying this video so far, please help us out by hitting that like button. You can also subscribe for loads of plain language, actionable advice. If you're new to research, check out our free dissertation writing course, which covers everything you need to get started on your research project. As always, links in the description. Now that we've got a clearer picture of what content analysis is, the logical next question is, when should you use it? As a qualitative method focused on recorded communication, content analysis is often most appropriate for research topics focused on changes and patterns in communication around social, economic, or political issues. For example, a research project that involves analyzing government policy regarding healthcare in the UK might look at the use of phrases like healthcare, the NHS, and hospitals in political commentary. An analysis could then be done on the frequency of these phrases and or their relationship to other associated words and phrases. On the other hand, research that's focused on the use of language in context might not be the best fit for content analysis. In other words, if your research is about the particular impact of language in specific social contexts, then content analysis could potentially be too narrowly focused. For example, if you're wanting to assess how political speech is used in impoverished environments to impact beliefs and opinions, a more context-oriented analysis method, such as discourse analysis, could be more appropriate. Simply put, make sure that you always consider the nature of your research aims when you're deciding on an analysis method. Okay, that was a lot, so let's do a quick recap. Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that draws findings from analysis of recorded communication, which can include both primary and secondary data. As we discussed, content analysis can be approached in two ways. Conceptual analysis, where the focus is on the frequency of concepts, and relational analysis, where the focus is on the meaning of and relationship between concepts. As with any analysis method, content analysis has its own set of strengths and weaknesses. As a result, content analysis is generally most appropriate for research focused on changes and patterns in recorded communication. If you got value from this video, please hit that like button to help more students find this content. For more videos like this, check out the Grad Coach channel, and subscribe for plain language, actionable research tips and advice every week. Also, if you're looking for one-on-one support with your dissertation, thesis, or research project, be sure to check out our private coaching service, where we hold your hand throughout the research process, step by step. You can learn more about that and book a free initial consultation at gradcoach.com.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- For authors

- New editors

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Online First

- Associations between growth, maturation and injury in youth athletes engaged in elite pathways: a scoping review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1915-9324 Gemma N Parry 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1460-0085 Sean Williams 1 ,

- Carly D McKay 1 ,

- David J Johnson 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1377-0234 Michael F Bergeron 3 ,

- Sean P Cumming 1

- 1 Department of Health , University of Bath—Claverton Down Campus , Bath , UK

- 2 West Ham United Football Club , London , UK

- 3 Performance Health , WTA Women’s Tennis Association , St. Petersburg , Florida , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Gemma N Parry; gp799{at}bath.ac.uk

Objective To describe the evidence pertaining to associations between growth, maturation and injury in elite youth athletes.

Design Scoping review.

Data sources Electronic databases (SPORTDiscus, Embase, PubMed, MEDLINE and Web of Science) searched on 30 May 2023.

Eligibility criteria Original studies published since 2000 using quantitative or qualitative designs investigating associations between growth, maturation and injury in elite youth athletes.

Results From an initial 518 titles, 36 full-text articles were evaluated, of which 30 were eligible for final inclusion. Most studies were quantitative and employed prospective designs. Significant heterogeneity was evident across samples and in the operationalisation and measurement of growth, maturation and injury. Injury incidence and burden generally increased with maturity status, although growth-related injuries peaked during the adolescent growth spurt. More rapid growth in stature and of the lower limbs was associated with greater injury incidence and burden. While maturity timing did not show a clear or consistent association with injury, it may contribute to risk and burden due to variations in maturity status.

Conclusion Evidence suggests that the processes of growth and maturation contribute to injury risk and burden in elite youth athletes, although the nature of the association varies with injury type. More research investigating the main and interactive effects on growth and maturation on injury is warranted, especially in female athletes and across a greater diversity of sports.

- Athletic Injuries

- Sporting injuries

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data relevant to the study have been uploaded as supplementary information.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2024-108233

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Growth and maturation during adolescence have been identified as risk factors for potential injury in young athletes.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This review identified 30 contemporary studies. Injury incidence and burden appear most closely related to maturity status and tempo of growth, with growth-related injuries peaking during the adolescent growth spurt. Practitioners are advised to consider measures of growth and maturation alongside clinical and field-based measurements.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Several methodological limitations and inconsistencies exist in the current evidence. Greater consistency and agreement on measurement practices could benefit future research quality, with the inclusion of female and non-football populations to address large gaps in the literature.

Introduction

The relationship between growth, maturation and injury risk in youth athletes is a topic of increasing interest in sports medicine, with a particular focus on the adolescent growth spurt 1 . Initiated by changes in the endocrine system, adolescence is the transitional phase between childhood and adulthood, during which the body undergoes rapid changes in size, shape and composition. 2 It also involves transformation of the circulatory, respiratory and metabolic systems, resulting in substantial changes in athletic and functional capacity. 3 Although the processes of growth and maturation have been proposed as risk factors for injury in young athletes, the evidence to support this contention is limited. 4 Limitations within the research are, however, noted, including heterogeneity across samples, research designs and analytical methods, poor reporting quality and high loss to follow-up. 4

Associating growth and maturation with injury in youth athletes is a logical premise. 5 Physeal injuries are a unique consideration for those working with youth populations. 6 Rapid asynchronous growth in skeletal, muscular and ligamentous structures creates increased ligament stress transfer through relatively weaker physeal plates and bone layers, increasing risk for such injuries. Age-related changes in bone mineral density, imbalances between flexibility and strength and alterations in joint stiffness further contribute towards an increased susceptibility to fractures at the growth plate and apophyses. 5 7 Apophyseal and physeal injuries also follow a distal-to-proximal 8 gradient, consistent with the sequential and asynchronous nature of adolescent growth. 8 9 For example, Sever’s disease at the posterior calcaneus tends to present in advance of Osgood-Schlatter’s or Sinding-Larsen at the knee, which, in turn, present in advance of apophyseal injuries at the sites of the iliac crest and ischial tuberosity of the hip. Apophyseal injuries are attributed to the softening or malformation of the articular cartilage, the latter of which is associated with more rapid growth during adolescence. 7 From a perceptual-motor perspective, rapid and asynchronous changes in skeletal, muscular and ligamentous structures, coupled with developmental changes in neurocognitive processing, have also been linked to temporary disruptions in mobility and motor-coordination, which may further increase injury risk. 5

The introduction of injury surveillance and growth and maturation profiling systems in many elite performance pathways (eg, national athlete development programmes, professional sport academies) has afforded a more systematic and rigorous approach to monitoring physical development and health in young athletes. 10 Implemented in parallel and delivered by trained professionals and clinicians, these organised strategies have enabled the capture of high-quality longitudinal data in young athletes, stimulating further research related to growth, maturation and injury. Characterised by early specialisation and maintained elevated levels of training and competition, elite performance pathways may also provide a more conducive environment from which to observe and investigate associations between physical development and injury in youth. 1 Considering these advances, this scoping review endeavours to synthesise and expand on a previous systematic review, 4 with the aim of providing clinicians, researchers and other stakeholders with a description of contemporary research related to growth, maturation and injury in youth athletes engaged in current elite sports pathways, with a particular emphasis on the operationalisation of growth and maturation, methodological quality and assessment, sample populations, emerging evidence, knowledge gaps and limitations within the extant literature.

Equality diversity and inclusion statement

The author and article screening teams were gender-balanced and included senior and junior academic staff from multiple disciplines and professions. Articles were restricted to those published in English but were not excluded based on country of origin. Gender equity in the study of physical development and injury in young athletes is addressed in the discussion.

Information sources and search strategy

This review was commissioned by the International Olympic Committee to describe the extent, type and quality of contemporary research and evidence pertaining to growth, maturation and injury in ‘elite youth athletes’, contributing towards a consensus statement on the health, safety and sustainability of young athletes competing at the Olympic games. A definition of ‘elite youth athletes’ as ‘highly trained and invested youth athletes routinely participating at national level (Tier 3) to world-class (Tier 5) athletic competitions’ was established in advance of the review 11 12 and extended to include dancers enrolled in professional dance schools.

The search was conducted, in general, adhering to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews, PRISMA-ScR ( online supplemental figure S1 ). All 20+2 PRISMA-ScR reporting items were met, except for protocol registration. Five databases (SPORTDiscus, Embase, PubMed, MEDLINE and Web of Science) were searched for relevant articles. As the review aimed to inform a contemporary consensus statement regarding the health and well-being of elite young athletes, the article search was restricted to peer-reviewed publications written in English from 1 January 2000 to 30 May 2023. A series of unique search terms were employed to identify relevant articles. The Boolean Operators “OR” and “AND” were used to broaden the search results, define the population of interest (ie, elite youth athletes), limit the intended outcomes of our search (ie, injury) and link the search terms. An asterisk (*) was applied to some keywords to search the database for all endings of the word or phrase (eg, matur*). The final search strategy being: (1) “elite” AND “youth” AND “athlete”, (2) AND “growth” OR “matur*” OR “pubert*”, (3) AND “Injur*” OR “medial epicondyle apophysitis” OR “Proximal Humeral Epiphysitis” OR “stress fracture” OR “growth plate fracture” OR “Pars” OR “Femoroacetabular impingement” OR “apophysitis” OR “Sever’s” OR “Osgood” OR “osteochondrosis” OR “osteochondritis dissecans” OR “spondylolysis”.

Supplemental material

Eligibility criteria and description of eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria were articles based on primary research, using original data and related to elite youth athletes. To meet the definition of ‘elite’ and be included in the review, the samples within each study had to be described in a manner that aligned with the criteria for routine participation in national (Tier 3) to world-class (Tier 5) competition. 12 For example, athletes who were members of professional sports academies or national development programmes were considered to have met these criteria. Studies using quantitative designs had to include measures of injury and growth and/or maturation. Qualitative studies investigating associations between growth, maturation and injury in elite youth athletes were eligible for inclusion. Review articles and case studies were excluded. Two independent reviewers (GNP, SC) completed the review process in May 2023. Each reviewer screened the articles, first at the level of title and abstract and then at the level of full text, to judge if the eligibility criteria were met. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and final consensus.

Data synthesis

To ensure consistency in the operationalisation of growth and maturation, the following definitions were adopted. 2 Growth was defined as rate of change in size of the body, its parts, or the proportions of various parts (eg, cm per annum, kg per annum). Maturation refers to the processes of progress towards the mature state occurring in multiple biological systems (eg, endocrine, sexual, skeletal and somatic) and was defined in terms of status, tempo and timing. Status denoted the stage of maturation attained at a specific time point, (eg, pre-peak height velocity (PHV), circa-PHV, post-PHV) whereas tempo described the rate at which maturation occurs. Timing was defined as the age at which maturational events (eg, PHV) occurred and/or the degree to which an athlete was advanced, on-time or delayed in maturation relative to age-specific and sex-specific standards. The data extracted from the eligible studies were summarised descriptively ( online supplemental table S1 ) and appraised with respect to methodological quality.

Study selection

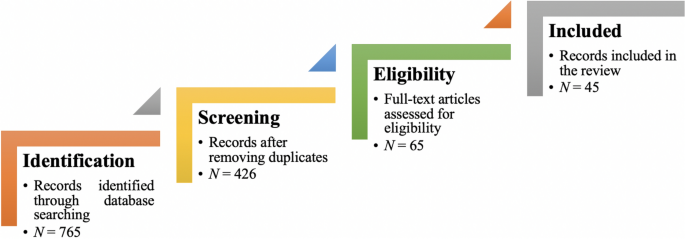

The initial search retrieved 871 citations of which 518 remained after removing duplicates. Full texts of 37 articles were reviewed to determine eligibility, 30 of which were eligible for final inclusion. The eligible articles included 28 quantitative and 2 qualitative studies ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study selection process based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment/analysis of quality

Descriptive data were extracted from eligible studies, comprising study design, population, measures and operationalisation of growth and maturation, and injury definition and outcomes (eg, incidence, burden) ( online supplemental table S1 ). The methodological quality of the quantitative studies (n=28), as judged on the Downs and Black Scale, 13 ranged from 7 to 19 out of 32 points ( online supplemental table S2 ). The Downs and Black Scale is a 28-item checklist used to assess the methodological quality of both randomised and non-randomised studies, evaluating factors such as reporting, external validity, internal validity (bias and confounding) and statistical power. The median quality score of these articles was low (14/32), attributable to study design and the absence of explicit explanations regarding variables of interest and consideration of confounding factors. While some articles included large samples, the distribution of participants by maturity status and/or timing categories was typically non-normal, resulting in inadequate statistical power in several studies. Most studies focused on soccer (n=19) and were exclusive to male participants (n=24). Only four quantitative studies included male and female athletes, and none considered female-only cohorts. The two qualitative papers appraised using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research 14 15 both met 8 out of the 10 criteria, with each noting a failure to consider potential researcher influence on the study findings as a limitation. A breakdown of the individual item scores for each article using the Downs and Black and JBI checklists is available in online supplemental file 2 .

Maturity status and injury

17 quantitative studies 8 16–31 adopting prospective designs and two qualitative studies 32 33 investigated associations between maturity status and injury ( table 1 ). 16 of the quantitative studies 8 16–20 22–31 employed non-invasive estimates of somatic maturation with estimated age at PHV (EA PHV) (n=11) and percentage of predicted (%PAH) or attained adult height (% AAH) (n=5) the most common methods. One study used an estimate of sexual maturation to classify youth handball players as mature or immature. Wik and colleagues 30 employed estimates of both skeletal and somatic maturation in study of maturation and injury in male track and field athletes. Most studies categorised athletes into groups based on maturity status, however, five studies treated maturation as a continuous variable. 19 24 26 27 30 Samples sizes varied from n=21 24 to n=502. 17 The methodological quality of the quantitative studies ranged from poor 29 to fair. 34 Two qualitative studies 32 33 investigated coaches’ and practitioners’ perceptions of how maturational status was related to injury risk in male and female gymnasts. Both of these studies achieved JBI scores of 8 out of 10, indicating a high quality of qualitative research.

- View inline

Associations between maturational status and injury for all eligible studies

The maturational stage associated with the adolescent growth spurt (ie, circa-PHV) appears to yield the greatest increase in injury incidence per 1000 hours, in papers reporting competition, training and overall time loss. When broad definitions of injury were observed, circa-PHV status was associated with greater incidences of overall, 25 non-contact 19 20 and traumatic 28 29 injuries in academy soccer, and higher incidences of all-complaint injuries in both male and female elite youth gymnasts with the peak approximating 90% PAH. 24 While the evidence suggests a general trend towards increased injury incidence and burden with advancing maturation, 16 17 21 the nature of reported associations varied relative to injury type. 8 17 Circa-PHV and pre-PHV status were associated with a higher incidence or prevalence of injuries classified as growth-related in track and field, 34 handball 21 and soccer, 8 17 but not squash. 18 Both qualitative studies also identified the growth spurt as a maturational stage where incidence and burden for growth-related and lower back injuries was greater. 32 33 Moreover, growth-related injuries followed a distal-to-proximal gradient aligned with the sequential and asynchronous nature of adolescent growth. 8 Specifically, these injuries tended to present first in the more distal segments of the lower limbs, before presenting in the more proximal segments of the lower extremities, and finally the trunk and pelvis. Consistent with this pattern, a higher probability for non-contact lower extremity injuries was observed in U13–14 soccer players during the earlier phases of the adolescent growth spurt. 26 A greater number of years to EA PHV was, however, associated with an increased probability for traumatic and overuse injuries in male and female alpine skiers. 27 Mature athletes, or those advanced in maturity status (post-PHV), exhibited the lowest incidence and burden of growth-related injuries, 8 22 23 34 yet evidenced a higher incidence and burden for muscular, cartilaginous and ligamentous injuries in soccer, 8 23 but not in handball where these injuries were higher in immature athletes. 21 Maturity status was unrelated to patellar tendinopathy in male and female ballet dancers. 31

Associations between advancing maturity status and injury burden were observed in several studies. As with injury incidence, associations with burden varied by time-loss definitions and injury type. Six studies in soccer 16 17 19 20 22 23 that used various definitions of time loss reported an increase in injury burden with advancing maturity, with one study documenting peak burden for non-contact injuries at 95% PAH. 19 There were notably higher burdens of growth-related injuries in athletes during the pre and circa-PHV stages in soccer. 17 22 23 The post-PHV stage is associated with a reduced burden for growth-related injury burden, 17 22 but an increase in burden for non-contact 19 and muscle and joint-related injury, 22 although these findings are currently limited to male soccer players.

Maturity timing and injury

10 quantitative studies 20 22 28 35–41 using prospective designs ( table 2 ) investigated associations between maturity timing and injury. Six studies employed estimates of somatic maturation with EA PHV (n=4) 29 40 41 and %PAH 20 37 (n=2) the preferred methods. There was substantial heterogeneity in the criteria used to define early maturation, on-time maturation and late maturation across methods. Four studies 35 36 38 39 employed estimates of skeletal age via hand-wrist radiographs. To define early maturation, on-time maturation and late maturation, three studies 35 36 38 used the traditional criterion of ±1 years SA-CA (skeletal age-chronological age); whereas one study used ±0.5 years SA-CA. 39 Nine studies 20 22 28 35–39 41 included male athletes and one study included males and females. 40 Eight of the studies involved soccer, 20 22 29 35–39 with single studies in track and field 41 and alpine skiing. 40 Sample sizes ranged n=26 29 to n=233. 38 The methodological quality of the studies was generally low, ranging from poor 29 to fair. 39

Associations between maturational timing and injury for all relevant selected studies

Associations between the timing of maturity and injury were observed across several, 22 29 36 38 39 but not all 20 35 37 studies of male soccer players. The nature and direction of these associations did, however, vary depending on injury type and the age range of the sample. A closer inspection of the findings suggested that the impact of maturity status was more important than the timing of maturity itself when investigating injury susceptibility in young athletes. Consistent with this hypothesis, U14 and U13–U19 players categorised as early-maturing presented a higher incidence of injuries associated with more advanced stages of maturation, including reinjury, injury to ligaments, tendons and muscles and injuries to the groin, head or face, and overall injuries. 36 38 Early-maturing U14 players also reported higher burdens for time loss, muscle, hamstring and joint/ligament-related injuries. 39 In contrast, players categorised as ‘on-time’, presented higher incidence rates for injuries associated with the early-to-mid stages of adolescence, including lower limb apophyseal injuries, anterior inferior iliac spine avulsions, Osgood-Schlatter’s, Sever’s and knee-related injuries in on-time than early maturing. 36 38 In comparison to late-maturing players, on-time U14 players presented higher rates of incidence for, groin injuries, tendinopathies and moderate injuries, 36 and higher burdens for joint/ligament, knee, anterior inferior iliac spine, growth-related and time-loss injuries. 22 39 Late-maturing players presented higher incidence rates for osteochondrosis, thigh, growth-related and major injuries than early-maturing players, and a higher incidence of tendinopathies and osteochondral disorder of the knee than early and on-time players. 36 38 Late-maturing track and field athletes also presented a higher incidence for foot, ankle and lower limb injuries compared with their peers. 41 Despite late-maturing alpine skiers presenting a higher prevalence of traumatic and overuse injuries, respectively, these values did not differ statistically from early-maturing skiers. 40

Growth and maturity tempo and injury

Nine quantitative studies 19 23 25 27 34 42–45 adopting prospective designs ( table 3 ) and two qualitative studies 32 33 investigated associations between rate of growth and/or maturation and injury. Rate of change in stature (n=9) and leg length (n=5) were the most frequent growth measures. Four studies assessed growth tempo in body mass and mass-for-stature. Singular studies considered growth of the foot, 42 torso 30 and tempo of skeletal maturation. 34 Six studies 19 23 25 43–45 involved male soccer players with the remaining studies involving male track and field athletes, 34 and dancers 42 and alpine skiers 27 of both sexes. Samples sizes ranged from n=46 42 to n=378. 45 The methodological quality of the studies was generally low, ranging from poor 43 to fair. 34 45

Associations between growth and maturation indices and injury for all relevant selected studies

More rapid gains in stature were associated with a higher incidence and/or probability of overall, 25 43 45 non-contact 19 and overuse 44 injuries in male academy soccer players, and bone and growth plate injuries in male track and field athletes. 34 Greater growth in stature was, however, associated with a reduced probability for acute injuries in U13–15 academy soccer players 44 and overall injuries in male and female alpine skiers. 27 More rapid gains in stature during PHV was associated with a higher burden for overall, knee and growth-related injuries, but not muscle, joint/ligament, knee or ankle injuries in U14 academy soccer players. 22 A non-linear (inverted-U) association between growth in stature and burden for non-contact injuries was reported in U13–U16 male soccer players, with peak estimated injury burden occurring at 4.17 cm per year. 19 More rapid growth of the lower limbs was associated with a higher probability for overall injuries in alpine skiing 27 and track and field, 34 overuse 44 injuries in soccer, and bone and growth plate in track and field. 34 As with stature, a non-linear association was observed between growth rate of the lower limbs with peak estimated injury burden occurring at a growth rate of 5.27 cm per year. 19

Rate of growth in body mass did not differentiate between injured and non-injured alpine skiers 27 and was not associated with injury probability in track and field athletes 34 and U10–15 soccer players. 44 Greater seasonal gains in body mass were observed in injured vs non-injured Italian soccer players; however, growth in mass did not emerge as a predictor of injury in a subsequent regression model. 25 With respect to mass-for-stature, more rapid gains in body mass index (BMI) were observed between injured vs non-injured Dutch soccer players, 43 but not their Italian counterparts. 25 Rate of change in BMI was unrelated to overall injury risk injury in alpine skiing 27 and overall, gradual and sudden-onset, bone and growth plate injuries in track and field. 34

In both qualitative studies, 32 33 more rapid gains in stature and mass were perceived as risk factors for injury in young gymnasts, with specific reference to stress fractures, growth-related, shoulder and lower back injuries. The risk was also perceived to be higher when accompanied with high or sudden spikes in training and competition loads, and restricted eating.

Trunk growth was unrelated to probability for overall, gradual onset, sudden onset, bone or growth plate-related injuries in track and field athletes. 34 More rapid growth of the foot was, however, associated with a higher risk for lumbar and lower extremity injury risk in male and female dancers. 42 Finally, more rapid changes in skeletal maturation were associated with an increased risk of bone injuries in a track and field athletes, yet was unrelated to risk of gradual-onset and sudden-onset, growth plate and overall injuries. 34

This review described contemporary research and emerging evidence related to growth, maturation and injury in youth athletes engaged in elite performance pathways. A total of 30 articles were deemed eligible for inclusion in this review with the majority involving male soccer players. The disparity between sports reflects the popularity of soccer, as a sport, and the significant investment by professional clubs and national governing bodies in the monitoring of physical development and health of young players. 10 Implemented in parallel, injury surveillance and growth and maturity profiling systems have enabled researchers to collect high-quality longitudinal data, consider the implications of growth and maturation across diverse injury types and perform more sophisticated methods of analysis. Those investigating the associations between growth, maturation and injury in young athletes should look to soccer for examples of good practice (see Monasterio, 8 22 23 39 Rommers, 44 45 Materne 38 and Hall 17 ), such as the aggregation of data across age groups, clubs and/or multiple seasons and consideration of different injury types and interactional effects. Wik’s investigation of both maturity status and tempo as risk factors across multiple injury types in track and field also serves as a good example of innovative practice within this field. 34

The lack of studies involving and/or exclusive to female athletes is a particular concern. The eligible studies that considered physical development and injury in female athletes all had comparatively small sample sizes and, thus, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the evidence. Injury research related to male athletes does not always generalise to female athletes. 46 The sex differences in human anatomy and physiology that emerge during puberty may predispose male and female athletes to variable levels of injury risk. 7 Whereas some studies have found female athletes to be at greater or reduced risk for certain types of injury, 46 47 others suggest more comprehensive research and data are still required to effectively inform injury prevention and treatment strategies specific to female athletes. 48 There is a need for sport’s national governing bodies to prioritise and invest in research related to physical development and injury in female athletes. Care must, however, be taken in the design and implementation of growth and maturity profiling strategies for female athletes with particular sensitivity around the collection, communication and use of data. 49 Data pertaining to physical development should be used to understand and support the health and development of the athletes and not as a criteria for the selection and exclusion of athletes. 49 Clinicians and researchers should seek to identify those injuries that female and, to a lesser extent, male athletes may be more or less susceptible to at different stages of maturation and consider strategies for the early detection and mitigation of conditions such as relative energy deficiency RED-S which can compromise physical development and the immediate and long-term health of youth athletes. 49 Researchers should also investigate the extent to which the processes of growth and maturation contribute to the elevated risk of medial collateral ligament (MCL) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries observed in female athletes during adolescence. 7

The evidence reviewed suggests that susceptibility to injury in youth athletes varies relative to maturity status. Adopting a broad definition of injury, incidence and burden generally increases with advancing maturation. The nature of the association between maturity status and injury does, however, vary relative to injury type. The adolescent growth spurt signalled a marked increase in the incidence and burden of growth-related injuries, confirming the beliefs and experiences of coaches and medical practitioners. 32 33 Growth-related injuries were most prevalent at the onset and during the growth spurt, with apophyseal, osteochondrosis and avulsion prominent in numerous sport contexts. 8 18 21 22 33 34 Growth-related injuries also followed a distal-to-proximal gradient consistent with the sequential and asynchronous nature of adolescent growth, before declining in both incidence and burden post-PHV. In contrast, the incidence of muscular, cartilaginous and ligamentous injuries generally increased with advancing maturity status and were most prevalent in athletes categorised as mature and/or post-PHV. Increased susceptibility for such injuries post-PHV has been attributed to several factors associated with growth and maturation, including disruptions in neuromuscular control, insufficient muscle capacity, imbalance in muscle and tendon growth, and increase in moments of inertia in athletes’ segments. 8 Despite much of the data within the eligible studies being normalised to exposure per 1000 hours, uncertainties remain regarding the standalone impact of maturational status on injury incidence and burden, given the variations in activity content (eg, modality, frequency, intensity, location) that may comprise an individual’s exposure hours.

The absence of a consistent pattern of association between timing and injury suggested that maturing in advance or delay of one’s peers (ie, timing) was not an inherent risk for injury. Rather, the extent to which timing impacts an athlete’s maturational status and/or proximity to PHV appeared to be of greater relevance. Compatible with this logic, early maturing athletes presented a higher incidence and burden for injuries associated with more advanced stages of maturity (eg, tendinopathies, groin strains, joint and ligament injuries, functional muscle disorders). 22 36 38 39 Conversely, on-time and late maturing reported a higher incidence and burden for injuries associated with the earlier stages of the growth spurt (eg, lower limb apophyseal injuries, osteochondrosis, AIIS, Osgood-Schlatter’s, Sever’s). 22 36 38 39 41 Due to inherent maturity selection biases that exist in sport, 3 50–52 late-maturing athletes were under-represented in several of the eligible studies 22 36 38 39 resulting in insufficient statistical power to make effective comparisons across groups. As late maturing athletes experience the growth spurt at an age when training intensities and volumes are typically higher, they may be more susceptible to injuries associated with growth or overloading. 53 Any elevated injury risk associated with later maturation may, however, be mitigated by a lower rate of growth at PHV. Future studies may need to aggregate data across teams, sport or consecutive seasons to test this hypothesis or focus on sports or activities where late developers are more likely to be represented (ie, gymnastics, ballet, diving).

More rapid gains in stature and length of the lower limbs were associated with a higher incidence of overuse, non-contact and growth-related injuries across several sports. Monasterio et al , also observed more rapid growth in stature to be associated with a higher burden for overall and growth-related injuries during PHV. 22 Johnson et al , did, however, report a non-linear associations between burden and rate of growth in stature and of the lower limbs, with peak burdens occurring post-PHV and at a rate of approximately 4-to-5 cm per year. 19 The delayed effect of injuries sustained during PHV on injury burden post-PHV may explain the discrepancy in these results. No clear or consistent associations were observed between rate of growth in mass and mass-for-stature with injury. Pubertal gains in mass and mass-for-stature may have greater injury implications for athletes participating sports that involve frequent landing, jumping, pivoting and high intensity accelerations and decelerations. 5 They may also have greater impact for risk in female athletes who experience larger gains in absolute and relative fat-mass, and corresponding smaller gains in absolute and relative strength during puberty. 2 50 Further research on the growth and injury in female athletes is needed with a particular focus on the preventative benefits of targeted functional movement and neuromuscular strength training interventions. 54–56

Intervention studies designed to mitigate growth-related injuries in young athletes are currently lacking. However, in the interim, growth and maturity profiling can provide valuable information pertaining to maturational status, timing and growth rate of individual athletes, enabling practitioners to identify athletes at heightened risk for specific injuries and adapt their training and conditioning accordingly. 1 For example, the Athletic Skills Model (ASM) describes a maturity-matching strategy whereby athletes identified as circa-PHV are assigned to training groups with an increased emphasis on movement competency, core and lower body strength, mobility, balance, coordination, coupled with reductions training load, intensity and movement repetition. 57 A recent intervention aligned to theASM principles resulted in marked reductions in non-contact injury incidence and burden among academy soccer players identified as circa-PHV and at-risk. 58 Although promising, further encompassing research is required to validate these findings.

Strengths and limitations

The inclusion of several contemporary studies conducted across multiple clubs or seasons was a strength of this review. 8 17 22 23 36 38 39 44 45 With comparatively large samples and more rigorous approaches to data capture, these studies enabled more comprehensive and detailed investigations of growth, maturation and injury. These studies also provided valuable insight as to the complex, multifaceted and dynamic nature of the relationship between physical development and injury in youth. The myriad of methodological limitations highlighted by Swain et al 4 persist, making it challenging to generalise findings or draw firm conclusions from the existing literature on this topic. Although the quality of the two qualitative studies was deemed excellent, the methodological quality of the quantitative studies was generally low, ranging from poor to fair. To improve research quality and robustness, there is a need to develop a contemporary consensus statement on standardised evidence-informed best practices for assessing and estimating growth and maturation in young athletes. This review was commissioned by the IOC as a wider contribution towards a consensus statement, and as such adopted a harmonised methodology. Researchers may wish to consider alternative methodologies in additional future reviews. Building on previews reviews and commentaries, 3 4 59–61 particular attention should be paid to the operationalisation of growth and maturation and the criteria used to determine maturity status, timing and tempo of growth. It is equally important to consider the rationale for measurement, analytical quality control, frequency of measurement, the education of key stakeholders and how data are communicated to athletes, parents/guardians and coaches. 49 The validity and reliability of the various methods used to estimate maturation should also be considered with a particular focus on non-invasive estimates of somatic maturation. 3 62 63

The evidence reviewed indicates that variability in growth and maturation plays a contributing role in the risk of injury among youth athletes engaged in high performance pathways. The associations involved are intricate and diverse, requiring further research to comprehend the precursors, mechanisms and contextual factors that may predispose athletes to a higher risk of specific injuries (eg, those related to motor competence, functional capacity, training/competition load and content). It is recommended that sport’s governing bodies simultaneously implement comprehensive injury surveillance and growth and maturity profiling systems for youth, along with educational content and a current consensus statement on best/standardised practice in the estimation and monitoring of growth and maturation. Such an approach has the potential to enhance our understanding of the connections between growth, maturation and injury and provide the empirical basis for the subsequent development and implementation of injury prevention programmes.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Research was approved by The University of Bath ethics committee #0122-80.

- Jayanthi N ,

- Cumming SP , et al

- Malina RM ,

- Bouchard C ,

- Kamper SJ ,

- Maher CG , et al

- Broderick C ,

- Steinbeck K

- Kerssemakers SP ,

- Fotiadou AN ,

- de Jonge MC , et al

- Cumming SP ,

- Monasterio X ,

- Bidaurrazaga-Letona I , et al

- Hawkins RD ,

- Hulse MA , et al

- Bergeron MF ,

- McKay AKA ,

- Stellingwerff T ,

- Smith ES , et al

- Pearson A ,

- Lockwood C ,

- Barendrecht M ,

- Larruskain J ,

- Gil SM , et al

- Horobeanu C ,

- Johnson A ,

- Pullinger SA

- Johnson DM ,

- Bradley B , et al

- Williams S ,

- Rincón JAG ,

- Ronsano BJM , et al

- McGregor A ,

- Williams K , et al

- Rinaldo N ,

- Gualdi-Russo E ,

- Oliver JL ,

- De Ste Croix MBA , et al

- Steidl-Müller L ,

- Hildebrandt C ,

- Müller E , et al

- van der Sluis A ,

- Elferink-Gemser MT ,

- Coelho-e-Silva MJ , et al

- Brink MS , et al

- Rudavsky A ,

- Fawcett L ,

- Heneghan NR ,

- James S , et al

- Fawcett L , et al

- Martínez‐Silván D ,

- Farooq A , et al

- Doherty PJ ,

- Le Gall F ,

- Carling C ,

- Williams S , et al

- Materne O ,

- Chamari K ,

- Bidaurrazaga‐Letona I ,

- Larruskain J , et al

- Fourchet F ,

- Loepelt H , et al

- Bowerman E ,

- Whatman C ,

- Harris N , et al

- Kemper GLJ ,

- Rommers N ,

- Rössler R ,

- Goossens L , et al

- Shrier I , et al

- Herman DC , et al

- Hollander K ,

- Junge A , et al

- Stephenson SD ,

- Vinod AV , et al

- Mountjoy M ,

- Sundgot-Borgen J ,

- Burke L , et al

- Baxter-Jones ADG ,

- Thompson AM ,

- Malina RM , et al

- Mitchell SB ,

- Radnor JM ,

- Moeskops S ,

- Morris SJ , et al

- Read PJ , et al

- Palumbo JP , et al

- Wormhoudt R ,

- Savelsbergh GJP ,

- Teunissen JW , et al

- Johnson D ,

- Broekhoff J

- Kozieł SM ,

- Králik M , et al

- Fransen J ,

- Skorski S ,

- Baxter-Jones ADG

X @GemmaNParry, @statman_sean, @Dr_CMCKay, @DrMBergeron_01, @phd_Sean

Contributors GNP, SC and SW conceptualised and planned the study design. GNP and SC led the study. GNP and SC contributed to article screening. GNP is guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study. GNP and SC has access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. GNP, SC and SW wrote the first draft of the article. All coauthors reviewed, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding The research was funded via a consultancy award from the International Olympic Committee

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 31 August 2024

Experiences, barriers and perspectives of midwifery educators, mentors and students implementing the updated emergency obstetric and newborn care-enhanced pre-service midwifery curriculum in Kenya: a nested qualitative study

- Duncan N. Shikuku 1 , 2 ,

- Sarah Bar-Zeev 3 ,

- Alice Norah Ladur 2 ,

- Helen Allott 2 ,

- Catherine Mwaura 4 ,

- Peter Nandikove 5 ,

- Alphonce Uyara 6 ,

- Edna Tallam 7 ,

- Eunice Ndirangu 8 ,

- Lucy Waweru 9 ,

- Lucy Nyaga 9 ,

- Issak Bashir 10 ,

- Carol Bedwell 2 &

- Charles Ameh 2 , 11 , 12

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 950 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Introduction

To achieve quality midwifery education, understanding the experiences of midwifery educators and students in implementing a competency-based pre-service curriculum is critical. This study explored the experiences of and barriers to implementing a pre-service curriculum updated with emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC) skills by midwifery educators, students and mentors in Kenya.

This was a nested qualitative study within the cluster randomised controlled trial investigating the effectiveness of an EmONC enhanced midwifery curriculum delivered by trained and mentored midwifery educators on the quality of education and student performance in 20 colleges in Kenya. Following the pre-service midwifery curriculum EmONC update, capacity strengthening of educators through training (in both study arms) and additional mentoring of intervention-arm educators was undertaken. Focus group discussions were used to explore the experiences of and barriers to implementing the EmONC-enhanced curriculum by 20 educators and eight mentors. Debrief/feedback sessions with 6–9 students from each of the 20 colleges were conducted and field notes were taken. Data were analysed thematically using Braun and Clarke’s six step criteria.

Themes identified related to experiences were: (i) relevancy of updated EmONC-enhanced curriculum to improve practice, (ii) training and mentoring valued as continuous professional development opportunities for midwifery educators, (iii) effective teaching and learning strategies acquired – peer teaching (teacher-teacher and student-student), simulation/scenario teaching and effective feedback techniques for effective learning and, (iv) effective collaborations between school/academic institution and hospital/clinical staff promoted effective training/learning. Barriers identified were (i) midwifery faculty shortage and heavy workload vs. high student population, (ii) infrastructure gaps in simulation teaching – inadequate space for simulation and lack of equipment inventory audits for replenishment (iii) inadequate clinical support for students due to inadequate clinical sites for experience, ineffective supervision and mentoring support, lack/shortage of clinical mentors and untrained hospital/clinical staff in EmONC and (iv) limited resources to support effective learning.

Findings reveal an overwhelmed midwifery faculty and an urgent demand for students support in clinical settings to acquire EmONC competencies for enhanced practice. For quality midwifery education, adequate resources and regulatory/policy directives are needed in midwifery faculty staffing and development. A continuous professional development specific for educators is needed for effective student teaching and learning of a competency-based pre-service curriculum.

Peer Review reports

Approximately one third of all maternal and neonatal deaths are due to poor quality maternal and newborn care [ 1 ]. Midwifery delivered interventions including skilled attendance at birth, provision of emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC) and family planning are central to averting the preventable maternal deaths, newborn deaths and stillbirths [ 2 ]. However, midwifery education and training in low- and middle-income countries is substandard leading to suboptimal quality of care [ 3 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that midwifery educators should possess competencies to support theoretical learning, learning in the clinical areas, assessment and evaluation of students and midwifery practice [ 4 ]. The International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) defines assessment as a systematic process for collecting qualitative and quantitative data to measure, evaluate or appraise performance against specified outcomes or competencies. On the other hand, it defines evaluation as the systematic process for collecting qualitative and quantitative data to measure or evaluate the overall provision of and outcomes of a course of studies [ 5 ]. Evidence suggests that midwifery educators are insufficiently prepared for their teaching role [ 4 , 6 ]. The ICM recommends that at least 50% of the midwifery curriculum to be practical-based with opportunities for clinical and community experience [ 5 ]. In many countries, this does not occur. The inadequately prepared midwifery faculty compounded with a deficient curriculum compared to international standards and limited practical clinical experience for students affect the quality of midwifery graduates and subsequent quality of care [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. As a result, midwifery educators are expected to structure their curriculum and develop learning activities that enable midwifery graduates to learn the knowledge and develop skills and behaviours essential for midwifery practice. The acquired competencies promote the role of the midwife to assess, diagnose, act, intervene, consult and refer as necessary, including providing emergency interventions [ 12 ].

The WHO, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and ICM recommend that skilled health personnel (includes midwives) as part of a team should be competent to perform all the signal functions of EmONC, to optimize the health and well-being of women and newborns [ 13 ]. Competency as defined in the Global Standards for Midwifery Education by ICM refers to the combined utilisation of personal abilities and attributes, skills and knowledge to effectively perform a job, role, function, task, or duty [ 5 ]. However, evidence shows that midwifery graduates are inadequately prepared with limited support and lack requisite competencies needed to function adequately as skilled health personnel after graduation [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 14 , 15 ]. Thus, midwifery graduates should achieve essential clinical competence – defined as a combination of knowledge, skill, attitude, judgment and ability needed for providing safe and effective care without any need for supervision [ 16 ]. Key barriers leading to suboptimal clinical competence include a deficient and largely didactic curriculum, educators/faculty who are less confident with clinical teaching compared to theoretical classroom teaching, inadequate teaching resources/equipment, insufficient clinical exposure of students for practice, absence of clinical supervisors and mentors and poor relationship with qualified hospital/clinical staff [ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 ].

Emergency obstetric and newborn care training helps improve the knowledge and skills of skilled health personnel, change in clinical practice and improved maternal and newborn health outcomes [ 20 ]. The Kenya national Ministry of Health (MoH) included EmONC training for skilled health personnel in the National Health Policy 2014–2030 and Health Sector Strategic Plan 2018–2023 as a priority to improve the quality of maternity care and subsequent maternal and newborn health outcomes [ 21 , 22 ]. Introducing the training at pre-service with a supporting curriculum has the potential for greater returns on midwifery investments [ 23 ]. Funded by Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine supported the Kenya MoH through the Nursing Council of Kenya and Kenya Medical Training College to conduct a detailed review of their national training syllabi and curriculum respectively. Curriculum content integrating EmONC and teaching methods were updated [ 24 ] aligned to the WHO and ICM competencies for midwifery practitioners and educators. This approach was designed to shift from the largely theoretical training to a competency-based skills training for graduates. This was followed by a bundle of interventions to build/strengthen the capacity of the training institutions and midwifery educators. The programme equipped the training colleges’ skills laboratories with EmONC training equipment. Blended (virtual and face-to-face) learning workshops for educators focusing on teaching (theory and practical/clinical EmONC skills), students’ assessments and giving effective feedback were conducted to improve their capacity to deliver the updated EmONC-enhanced curriculum. Supportive follow-up mentoring of midwifery educators in sampled colleges was implemented to build their professional skills in teaching, assessments and effective feedback. This bundle of interventions was evaluated and demonstrated improved educators’ knowledge, skills and confidence in teaching and EmONC skills [ 24 , 25 ]. Consequently, midwifery students’ knowledge and skills in EmONC improved before graduation [ 26 ]. Although the investments were promising, understanding experiences of educators and students is critical for a successful and sustainable implementation of the pre-service competency-based curriculum, scale up and uptake of the bundle of interventions.

Previous studies largely evaluated the changes in knowledge, skills and confidence of educators and students after programme training interventions [ 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 ]. However, studies focusing on experiences of the target group (either the educators or student group only) after midwifery educator capacity strengthening interventions are limited [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Experiences of students and educators enable midwifery educators to improve the design of the courses and support systems in place for effective teaching and learning [ 18 , 33 ]. Exploring students’ experiences is critical in determining what students find important and promoting their learning process [ 32 , 34 ]. This is relevant in designing training programmes that facilitate students’ learning and application of acquired competencies into practice.

This was a nested qualitative study within the broader cluster randomised controlled trial that assessed the effectiveness of a pre-service EmONC-enhanced midwifery curriculum delivered by trained and mentored midwifery educators in Kenya [ 35 ]. The objectives of this study were to explore the experiences, barriers and understand the perspectives of educators, students, and external mentors for educators to successfully implement an updated EmONC-enhanced curriculum during pre-service training. Findings are relevant to improve the design, delivery, uptake and scale-up of the pre-service midwifery programme for competent midwifery graduates as part of accelerating progress towards achieving maternal and newborn health sustainable development goals and universal health coverage.

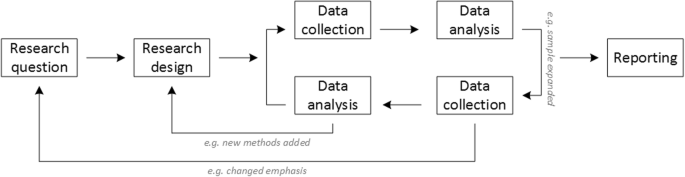

Study design

This was a qualitative descriptive study using focussed group discussions (FGDs) and field notes nested within a cluster randomised controlled trial reported in a separate paper [ 35 ]. Qualitative descriptive studies generate data that describe the ‘who, what, and where of events or experiences’ from a subjective perspective [ 36 ]. Qualitative studies in trials are important in interpretation of trial findings and enhances the understanding of how contextual barriers and facilitators may influence outcomes [ 37 , 38 ]. Insights from qualitative studies can also inform implementation if the intervention is successful. This is because they can help trialists ‘to be sensitive to the human beings who participate in trials’ [ 38 ]. The objective was to understand the experiences of educators, students and mentors, challenges encountered and opportunities for improving the delivery and implementation of the updated EmONC-enhanced midwifery curriculum in Kenya.

The Kirkpatrick model is an effective tool with four levels for evaluating training programmes [ 39 ]. Level 1 (Participants’ reaction to the programme experience) helps to understand how satisfying, engaging and relevant participants find the experience. Level 2 (Learning) measures the changes in knowledge, skills and confidence after training. Level 3 (Behaviour) measures the degree to which participants apply what they learned during training when they are back on job or impact of training to their practice. This level is critical as it can also reveal where participants might need help to successfully implement what was learned. Level 4 (Results) measures the degree to which targeted outcomes occur because of training. The findings from this study are further analysed using the Kirkpatrick model at level 1 (experiences of educators and students) and level 3 (application of what was learned and areas for further support and investment) to improve the quality of pre-service midwifery education and training.

The focus group discussions explored the experiences of educators with the updated content, clinical teaching and skills demonstration, peer teaching and support, clinical supervision and mentoring of students, and effective feedback. Also, institutional challenges/bottlenecks and support required to implementing the updated curriculum. Students feedback on the teaching of the updated curriculum, clinical placements, clinical support supervision and mentoring during placements was documented. Mentors’ experiences and perspectives on the uptake of mentorship intervention by educators were explored. Additional components from mentors included strengths observed during the mentorship intervention (educators and institutional); bottlenecks experienced in the mentoring intervention and opportunities for support and improvement. The study is reported in accordance with the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) (Supplementary Material) [ 40 ].

Study setting

This study was conducted in 20 (12 intervention arm and 8 control arm colleges) of the 52 KMTCs randomly selected in Kenya offering the integrated nursing and midwifery training programme in Kenya (Kenya Registered Community Health Nursing – KRCHN programme). This is the predominant direct entry programme offered at diploma level for nursing and midwifery workforce in the country. Each KMTC has two intakes of 50 students each per year (March and September), thus approximately 50 final year nursing and midwifery students are expected to graduate per intake. The duration of the diploma programme is three years with no internship period after graduation. Midwifery content and clinical placements are distributed across the three years of training. Students are posted to the respective hospitals (offering comprehensive EmONC services) attached to the training colleges for their clinical placements for practice and clinical experience. This is critical to reinforce theoretical learning, develop their clinical skills and attitudes for practice. A common curriculum by KMTC approved by the Nursing Council of Kenya is used for midwifery education in all colleges.

Intervention

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine supported the review and update of the predominant nursing and midwifery training curriculum for training of nurse midwives at diploma level in Kenya in 2020/2021. The curriculum review and update were conducted by selected midwifery educators and practitioners. The output was a pre-service curriculum with EmONC content. Following the review, midwifery educators from both study arms (intervention and control) received training on the new content to strengthen their capacity to deliver the EmONC-enhanced curriculum. Training used Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s adapted Emergency Obstetric Care and Newborn Care Skilled Health Personnel training package [ 41 ]. This package has been used by LSTM in collaboration with MoH in over 15 low- and middle- income countries to strengthen the capacity of maternity care providers for quality EmONC service delivery [ 42 ]. Educators in the intervention study arm received additional mentoring and peer support on teaching and EmONC skills every three months for 12 months.

Mentoring support intervention

This was conducted every three months after the training for 12 months in the intervention colleges. A group of eight experienced EmONC faculty consisting of midwifery educators and obstetricians were recruited and trained as mentors. Educators were from university or midwifery training colleges not included in the study and they did not form part of the master trainers. They received a virtual one-day mentorship training facilitated by the corresponding author and an LSTM – UK senior MNH specialist experienced in EmONC capacity strengthening and pedagogy. Training focused on introduction to mentoring, building effective working relationships, giving effective feedback, handling difficult situations during mentorship, and teaching methods. The training used interactive lectures, discussions, and case studies. Mentorship sessions were a full day intervention per college for educators and focused on teaching skills, EmONC skills and drills and giving effective feedback to promote learning among students especially on performance of critical lifesaving EmONC skills or scenarios.

Structured participant observation of teaching sessions (theoretical or practical) and support by mentors for midwifery educators were also conducted in the intervention study arm at 3, 9 and 12 months after the training. Key elements of good quality teaching and learning were observed including: [ 1 ] teaching style, [ 2 ] use of visual aids, [ 3 ] teaching environment and [ 4 ] student involvement using a standardized observation checklist [ 43 ].

LSTM’s lead researcher (corresponding author) based in Nairobi Kenya conducted quality assurance visits to some of the mentoring sessions for all mentors. At the end of the mentoring visit, debrief sessions were held by the mentor, mentees, and the campus administration as necessary. The debrief provided feedback and areas that needed institutional support to promote quality teaching and learning. On occasions where the lead researcher was not present at the mentoring visit, the mentor recorded and shared field notes on key strengths observed, areas for further support and the action points proposed by the mentees for development.

Participants

A convenience sampling approach was used to select participants that were already enrolled in the trial to take part in the FGDs. Twelve [ 12 ] intervention arm educators, eight [ 8 ] control arm educators and eight [ 8 ] mentors participated in the FGDs. Each training college was represented by one midwifery educator.

A total sample of 146 final year nursing-midwifery students (KRCHN March 2020 class), the first group to be taught the updated EmONC-enhanced curriculum participated in the study. Due to the variability in the number of students per college, 20 clusters of 6–9 students, selected through stratified systematic sampling who participated in the knowledge and skills assessments participated in the debrief sessions.

Data collection

Three virtual FGDs were conducted at six months of the implementation (February 2022) with the intervention and control colleges’ educators and mentors by the corresponding author using semi-structured interview guides. The adapted interview topic guides were piloted and validated in a previous study [ 28 ]. These guides were also reviewed by study team members with experience in qualitative research. Each FGD lasted between 60 and 90 min. Respondent/member validation/check was routinely applied during the interview discussions to ensure that participants’ responses were accurately interpreted [ 44 ]. The FGDs were audio-recorded with permission from participants and transcribed verbatim in English. New emerging data from educators and mentors was routinely collected during the study implementation period. This strategy was employed due to the information power from a sample of participants but with rich relevant information for the study in qualitative research [ 45 ]. Although the corresponding author was not a faculty member with the KMTC, his status was known to the participants.

Two debriefing sessions moderated by the corresponding author and two independent assessors per college were held with students immediately after completing the knowledge and skills assessments between December 2022 and March 2023. The independent assessors were midwives and obstetricians working as midwifery educators in public or private training institutions and/or in clinicals and experienced EmONC faculty. They worked in pairs per college and were blinded to the intervention implemented and study arms. Details on the assessments are reported in a different paper [ 35 ]. In the first debrief, lasting between 30 and 60 min, were conducted immediately after the assessments by the corresponding author and the two assessors with the students for every college. These were confidential and not recorded to allow students express themselves freely on their experiences with the completed assessments, curriculum content covered, clinical placements and support received during maternity clinical placements. The second debrief lasted between 15 and 30 min and included the available institutional midwifery faculty/administration, students and the research team. Field notes were taken during the students debrief sessions by the corresponding author. Due to the potentially sensitive nature of the students’ feedback in the first debrief, general findings were shared with the college midwifery faculty and administration during the second debrief. Areas of strengths, opportunities and weak sections that needed additional support for improvement were highlighted.

Data management and analysis

Preparation for data analysis involved a rigorous process of transcription of recorded FGDs. Data analysis was led by the lead researcher, but the other authors contributed by reviewing the transcripts and quality checks. Collaborative thematic framework analysis by Braun and Clarke (2006) was used as it provides clear steps to follow, is flexible and uses a very structured process and enables transparency and team working [ 44 ]. Due to the small number of transcripts, computer assisted coding in Microsoft Word using the margin and comments tool was applied for the FGD transcripts and manual coding of text for the field notes. The six steps by Braun and Clarke in thematic analysis were conducted: (i) familiarising oneself with the data – the lead researcher listened to all of the audio recordings while reviewing the transcripts, looking for recurring issues/inconsistencies and, identifying possible categories and sub-categories of data; (ii) generating initial codes – both deductive (using topic guides/research questions) and inductive coding (recurrent views, phrases, patterns from the data) were conducted to derive the codes and enhance transparency of the study. The lead researcher generated a comprehensive list of codes. A second author with expertise in qualitative research separately analysed a selection of transcripts and then compared codes, agreed codes and broad themes; (iii) searching for themes by collating initial codes into potential sub-themes/themes; each transcript was reviewed to refine sub-themes/themes and an exhaustive list of sub-themes/themes was generated (iv) reviewing themes by generating a thematic map (code book) of the analysis; data were mapped to identify prevalence (new and old) of themes; again, two authors compared and validated the interpretations using one transcript (v) defining and naming themes through repeated, systematic and collaborative analysis of transcripts (ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each sub-theme/theme, and the overall story the analysis tells); and (vi) writing findings/producing a report – findings were written up as descriptive accounts with illustrative quotes from the transcripts. Trustworthiness was achieved by (i) respondent validation/check during the interviews for accurate data interpretation; (ii) using a criterion for thematic analysis; (iii) returning to the data repeatedly to check for accuracy in interpretation; (iv) quality checks and discussions with the study team with expertise in mixed methods research [ 44 , 46 ].

Reflexivity

Due to the sensitive nature of the feedback from educators, students and mentors, the lead researcher had good awareness of who and where to address the emerging concerns from the study. These concerns together with programme achievements, challenges and best practices were disseminated to the KMTC management during the joint LSTM – MoH programme knowledge, management and learning dissemination events and policy forums. There was real benefit in the lead researcher being a near-peer to the participants as he was a male midwife educated and trained in Kenya and Uganda and an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, United Kingdom. He could relate to certain aspects of the educators and students’ experience of skills teaching and clinical placement as he had previous experience both as a midwifery student and adjunct faculty in the two countries. This also helped him to ask for points of clarification about certain aspects of the midwifery academic experience, educator and student experience, particularly around clinical skills teaching, organisation of clinical placements and midwifery support during the clinical placements. In addition, this allowed him sufficient distance to ask questions and not take the discussion contents personally. Use of multiple methods of data collection (knowledge surveys, direct observations through objective structured clinical evaluation of skills and debriefing after students assessments/field notes) enhanced triangulation of findings to give detailed descriptions and broad perspectives important in understanding the implementation of the updated EmONC-enhanced curriculum [ 46 ].