A Summary and Analysis of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

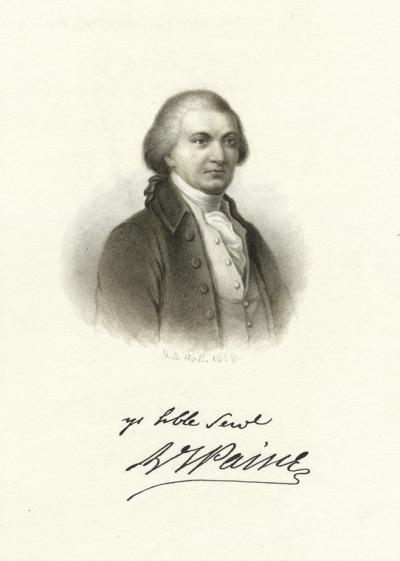

After the Declaration of Independence, probably the most important and influential document of the American Revolution was a short pamphlet written not by an American, but by an English writer who had been living in America for less than 15 months.

But although his country of birth was the very nation – Britain – that Americans were fighting against to secure their independence, Thomas Paine was most of the most significant supporters of the American cause.

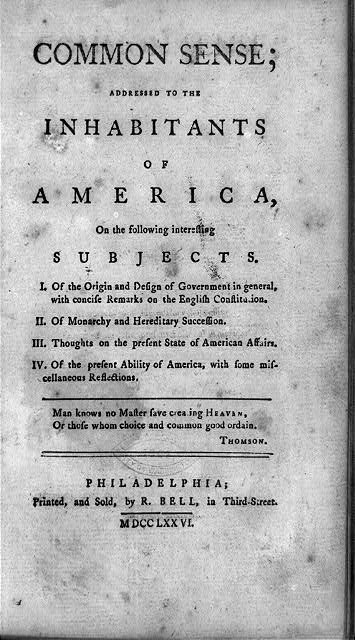

And Americans were clearly ready to hear what he had to say. Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense , published at the beginning of that momentous year, 1776, rapidly became a bestseller, with an estimated 100,000 copies flying off the shelves, as it were, before the year was out.

Indeed, in proportion to the population of the colonies at that time – a mere 2.5 million people – Common Sense had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history, before or since. Common Sense , it turns out, was fairly common – and very popular.

But what made Paine’s pamphlet of some 25,000 words and 47 pages strike such a chord with Americans in 1776? Why did Paine write Common Sense , and what exactly does the pamphlet say? Before we offer an analysis of this landmark text, here’s a summary of Paine’s argument.

Paine’s pamphlet is a polemical work, so he is not setting out to offer a balanced and even-handed appraisal of the facts. Instead, he views his role as that of rabble-rouser, stoking the fires of revolution in the heart of every American living under British rule in the Thirteen Colonies.

Common Sense is divided into four parts. In the first part, ‘On the Origin and Design of Government in General, with Concise Remarks on the Constitution’, Paine considers the role of government in abstract terms. For Paine, government is a ‘necessary evil’ because it keeps individuals in check, when their inner ‘evil’ might otherwise break out.

Paine then considers the English constitution, established in 1689 in the wake of the Glorious Revolution . The main problem is that England has monarchy and aristocratic power written into its constitution: the monarchy is a hereditary privilege which the individual king or queen has done nothing personally to ‘earn’, and the same is true of those who sit in the House of Lords and participate in government. (Paine was against all forms of hereditary power, believing the individual should earn whatever role they have.)

In the second part, Paine considers monarchy from a biblical perspective and a historical perspective. Aren’t all men equal when they are created? In that case, the idea that one man – calling himself king – is greater than his subjects, who are but his fellow men, is flawed. He cites various passages from the Old and New Testaments in support of his argument.

For example, he discusses 1 Samuel 8 in which God punishes the people for asking for a king. ‘That the Almighty hath here entered his protest against monarchical government is true,’ Paine argues, ‘or the scripture is false.’ And few of Paine’s God-fearing readers would believe that the Bible could be false in what it showed.

Next, Paine turns from the biblical to the historical argument against monarchical government, point out how past kings have been problematic: for example, the Wars of the Roses lasted for decades and kept England in a state of turmoil as two warring royal houses fought for control of the kingdom. ‘In short,’ Paine concludes, ‘monarchy and succession have laid (not this or that kingdom only) but the world in blood and ashes.’

Finally, Paine also attacks the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke ’s notion of a ‘mixed state’, a kind of constitutional monarchy where the monarch has limited powers. For Paine, this isn’t enough: most monarchs who wish to seize more power for themselves will find a way of doing so.

The third part of Common Sense , ‘Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs’, looks at the conflict between Britain and the American colonies, arguing that independence is the most desirable outcome for America. He proposes a Continental Charter which would lead to a new national government, which would take the form of a Congress. He then outlines the form that this would take (each colony, divided into smaller districts, who send delegates to Congress to represent them).

In the fourth and final section of the pamphlet, ‘On the Present Ability of America, with Some Miscellaneous Reflections’, Paine turns to the practicalities of fighting the British, both in terms of money and resources.

He draws attention to America’s strong military potential. Shipyards can be used to provide the timber to create a navy that could rival Britain’s. Economically, too, America is in a strong position because it has no national debt.

Before he arrived in America in 1774, Thomas Paine had a fine series of failures behind him: a onetime corset-maker and customs officer born in Norfolk in 1737, he travelled to the American colonies after Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in London, put in a good word for him.

Paine was soon editing the Pennsylvania Magazine , and in late 1775 began writing Common Sense , which would rapidly cause a sensation throughout the Thirteen Colonies. George Washington wrote to a friend in Massachusetts, ‘I find that Common Sense is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men’.

What was it about Paine’s pamphlet that caused such a stir? It was partly good timing: anti-British feeling had been growing in the last few years, especially since Britain introduced a range of taxes in 1763 to help fund their wars in Europe and India; such a tax famously led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and the British retaliation that swiftly followed.

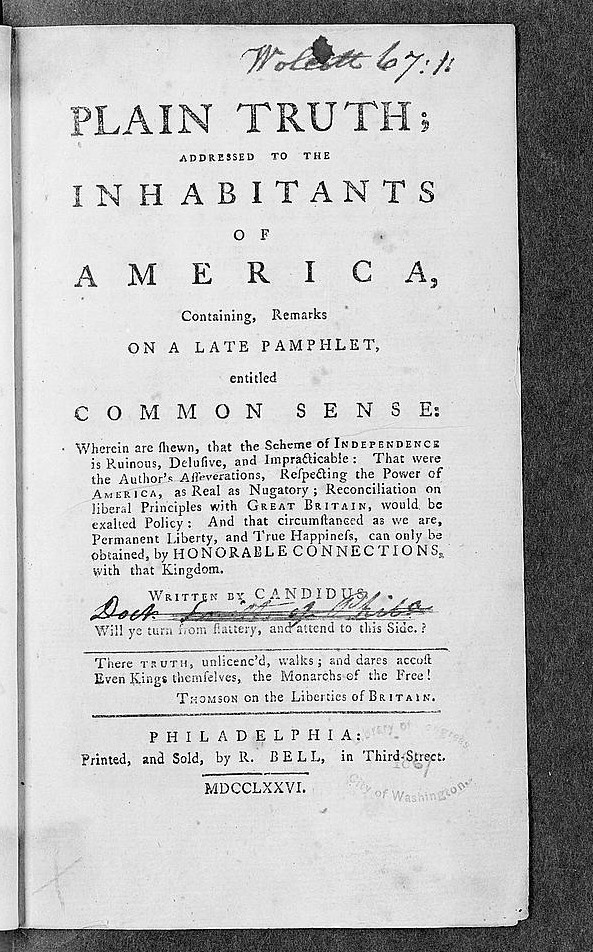

Nevertheless, in 1775 many Americans living within the Thirteen Colonies still favoured reconciliation with their British overlords. Put simply, many people didn’t have enough enthusiasm to go to war against such a powerful imperial nation as Britain. But Thomas Paine sensed that the appetite for a fight was there, if only someone could stir the populace to action; and he knew the right way to get the ordinary man and woman on side.

So Paine needed to do more than simply lay out the situation to such people. He needed to persuade them by showing in powerful and vivid language that Britain was a power-hungry imperial force under whose boot Americans were always going to suffer – unless, that is, they decided enough was enough.

With Common Sense , Paine helped to win over many of those waverers to the cause for independence. He did this, most of all, not by appealing to scholarly argument or intellectual reasoning but by going for the emotions of his readers (and listeners: many people gathered together to hear someone else read aloud from Paine’s essay). We should bear in mind the ‘common’ part of ‘common sense’: Paine was trying to reach everyone, regardless of education or social rank.

Painting the British king, George III, as a tyrannical power-hungry ruler who had overstepped the mark, Paine made the case against monarchical rule and in favour of democratic government. When Common Sense lit the touchpaper for revolution, Paine was more than prepared to put his money where his mouth is, too. He enlisted in the American army in July 1776 and continued to write pamphlets to boost morale throughout the years of bloody war that followed.

Common Sense was popular in America, but it was also translated into French and was eagerly taken up there. Indeed, Paine’s revolutionary call for an anti-monarchical system of government would later help to inspire the French Revolution in 1789, which Paine supported in its early stages. But it was in America that his revolutionary zeal first galvanised others to fight for independence from the monarch who ruled over them.

Fittingly, it was Thomas Paine, writing under the byline ‘Republicus’ in June 29, 1776, who became the first person to make a public declaration for the new country to be named the ‘United States of America’. An Englishman from rural Norfolk had helped to inspire countless Americans to make their country their own.

<script id=”mcjs”>!function(c,h,i,m,p){m=c.createElement(h),p=c.getElementsByTagName(h)[0],m.async=1,m.src=i,p.parentNode.insertBefore(m,p)}(document,”script”,”https://chimpstatic.com/mcjs-connected/js/users/af4361760bc02ab0eff6e60b8/c34d55e4130dd898cc3b7c759.js”);</script>

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Have Fun With History

Common Sense by Thomas Paine – Significance and Influence

“Common Sense” by Thomas Paine is a timeless and influential pamphlet that played a pivotal role in shaping the course of history.

Published in 1776 during the American Revolution, Paine’s persuasive writing and revolutionary ideas captivated the minds of the American colonists, sparking a fervent call for independence from British rule.

This brief exploration delves into the significance of “Common Sense,” its impact on the American Revolution, its role in fostering unity among the colonies, and its enduring influence on political thought both in the United States and beyond.

The Significance of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

1. advocated for american independence.

“Common Sense” was a groundbreaking pamphlet published by Thomas Paine in 1776, during a critical time in American history. Paine’s central argument was for the complete independence of the American colonies from British rule.

Also Read: Thomas Paine Timeline

He eloquently and passionately challenged the notion of a hereditary monarchy and questioned the legitimacy of the British monarchy’s authority over the distant colonies.

Paine argued that it was only natural for the American people to govern themselves, free from the control of a distant and unresponsive government across the Atlantic.

2. Played a crucial role in the American Revolution

The publication of “Common Sense” had an extraordinary impact on the American Revolution. At the time of its release, there was considerable debate within the colonies regarding the path they should take in response to British policies.

Also Read: Thomas Paine Facts

Paine’s pamphlet struck a chord with the general public, as it presented a compelling case for outright independence. The pamphlet was widely read and discussed, reaching people from all walks of life, including ordinary citizens, soldiers, and political leaders.

“Common Sense” helped galvanize public sentiment and mobilized support for the revolutionary cause. It provided a clear and powerful argument for why breaking away from British rule was not only justified but necessary for the preservation of liberty and self-determination.

3. Influenced the formation of the United States as a democratic republic

Beyond advocating for independence, “Common Sense” also laid out Paine’s vision for a new form of government for the American colonies.

Paine promoted the idea of a democratic republic, where the power to govern would be vested in the hands of the people, rather than in the hands of a monarch or ruling elite.

His ideas helped to shape the thinking of the Founding Fathers, such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, who played instrumental roles in drafting the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

Paine’s call for a government based on the consent of the governed and the protection of individual rights echoed throughout the founding documents of the United States, making a lasting impact on the country’s political structure and principles.

4. Written in a clear and accessible style

One of the key reasons for the immense impact of “Common Sense” was Thomas Paine’s ability to convey complex political ideas in a clear and straightforward manner.

Unlike many other political writings of the time, which were often dense and filled with formal language, Paine wrote in simple and accessible prose. He deliberately used everyday language that could be easily understood by common people, ensuring that his arguments reached a wide audience.

This approach was revolutionary in itself, as it made political discourse more inclusive and helped bridge the gap between the educated elite and ordinary citizens.

Paine’s writing style set a precedent for future political communication, emphasizing the importance of clarity and accessibility in conveying ideas to the masses.

5. Widely distributed throughout the American colonies

Despite the limited means of communication and printing technology in the 18th century, “Common Sense” achieved remarkable distribution and dissemination.

Paine initially published the pamphlet anonymously, but its authorship was soon revealed. It was printed and distributed in various cities and towns throughout the American colonies.

Due to its affordable price and easy-to-read format, many copies were sold and shared among people from all walks of life.

The pamphlet’s widespread availability ensured that its message reached a vast audience and contributed to its significant influence on public opinion. Paine’s work also inspired others to write responses and engage in a broader public debate about independence and self-governance.

6. Popularized republican ideology

“Common Sense” played a crucial role in popularizing republican ideals among the American colonists. Paine argued for a government based on the consent of the governed and advocated for the abolishment of monarchy and aristocracy.

He proposed a representative democracy, where elected officials would act in the best interest of the people and uphold their rights and freedoms. Paine’s promotion of these republican principles resonated with many colonists who were seeking a new and just form of government.

His ideas reinforced the belief that the power to govern should come from the people themselves, not from a distant and unaccountable monarchy.

This popularization of republican ideology helped solidify the concept of sovereignty residing with the people and contributed to the formation of democratic institutions in the emerging United States.

7. Contributed to the drafting of the Declaration of Independence

The ideas presented in “Common Sense” had a profound influence on the thinking of the Founding Fathers, many of whom were already sympathetic to the cause of independence. Thomas Paine’s arguments reinforced their beliefs and provided additional support for the case for separation from Britain.

Some of Paine’s language and concepts found their way into the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted on July 4, 1776.

Notably, the Declaration emphasized the principles of natural rights, the consent of the governed, and the right to alter or abolish an oppressive government, ideas that were already prominent in “Common Sense.”

While Paine himself was not directly involved in the drafting of the Declaration, his pamphlet played a significant role in shaping the intellectual climate that led to its creation.

8. Fostered unity among the American colonies

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, the thirteen colonies were diverse in terms of their backgrounds, economies, and political structures. They did not always see eye-to-eye on matters of governance and resistance to British policies.

“Common Sense” helped bridge these divides and fostered a sense of unity among the colonies. By providing a coherent argument for independence and republican government, Paine encouraged the colonies to work together in their struggle against British rule.

The pamphlet made the case that the shared cause of independence was more important than any regional differences or disagreements. As a result, “Common Sense” played a vital role in consolidating the colonies’ efforts and building a collective sense of identity that would prove crucial during the American Revolution.

9. Enduring influence on political thought

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” remains an enduring and celebrated work in the history of political thought. Its impact extended far beyond the American Revolution.

The pamphlet’s articulation of democratic principles, advocacy for independence, and criticisms of monarchy and tyranny have continued to inspire generations of thinkers, politicians, and activists around the world.

Paine’s ideas on the rights of individuals and the legitimacy of government have become foundational concepts in political theory and have shaped discussions on governance, liberty, and democracy for centuries. “Common Sense” stands as a testament to the power of persuasive writing and the ability of one individual to profoundly influence the course of history.

10. Inspired independence movements worldwide

Beyond its impact on the American Revolution and the formation of the United States, “Common Sense” had a broader influence on the global stage. Translations and excerpts of the pamphlet spread to other countries, inspiring independence movements and political revolutions in various parts of the world.

Paine’s ideas on the rights of people to govern themselves and the need to challenge oppressive authority resonated with individuals and groups seeking freedom and self-determination in different contexts. “Common Sense” became a symbol of the transformative power of ideas, inspiring movements for liberty and independence throughout the ages and across continents.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Thomas Paine

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 29, 2022 | Original: November 9, 2009

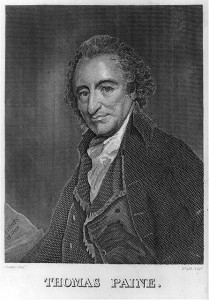

Thomas Paine was an England-born political philosopher and writer who supported revolutionary causes in America and Europe. Published in 1776 to international acclaim, “Common Sense” was the first pamphlet to advocate American independence. After writing the “The American Crisis” papers during the Revolutionary War, Paine returned to Europe and offered a stirring defense of the French Revolution with “Rights of Man.” His political views led to a stint in prison; after his release, he produced his last great essay, “The Age of Reason,” a controversial critique of institutionalized religion and Christian theology.

WATCH: The Revolution on HISTORY Vault

Early Years

Thomas Paine was born January 29, 1737, in Norfolk, England, the son of a Quaker corset maker and his older Anglican wife.

Paine apprenticed for his father but dreamed of a naval career, attempting once at age 16 to sign onto a ship called The Terrible , commanded by someone named Captain Death, but Paine’s father intervened.

Three years later he did join the crew of the privateer ship King of Prussia , serving for one year during the Seven Years' War .

Paine Emigrates to America

In 1768, Paine began work as an excise officer on the Sussex coast. In 1772, he wrote his first pamphlet, an argument tracing the work grievances of his fellow excise officers. Paine printed 4,000 copies and distributed them to members of British Parliament .

In 1774, Paine met Benjamin Franklin , who is believed to have persuaded Paine to immigrate to America, providing Paine with a letter of introduction. Three months later, Paine was on a ship to America, nearly dying from a bout of scurvy.

Paine immediately found work in journalism when he arrived in Philadelphia, becoming managing editor of Philadelphia Magazine .

He wrote in the magazine–under the pseudonyms “Amicus” and “Atlanticus”–criticizing the Quakers for their pacifism and endorsing a system similar to Social Security .

'Common Sense'

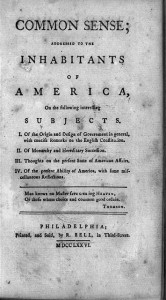

Paine’s most famous pamphlet, “Common Sense,” was first published on January 10, 1776, selling out its thousand printed copies immediately. By the end of that year, 150,000 copies–an enormous amount for its time–had been printed and sold. (It remains in print today.)

“Common Sense” is credited as playing a crucial role in convincing colonists to take up arms against England. In it, Paine argues that representational government is superior to a monarchy or other forms of government based on aristocracy and heredity.

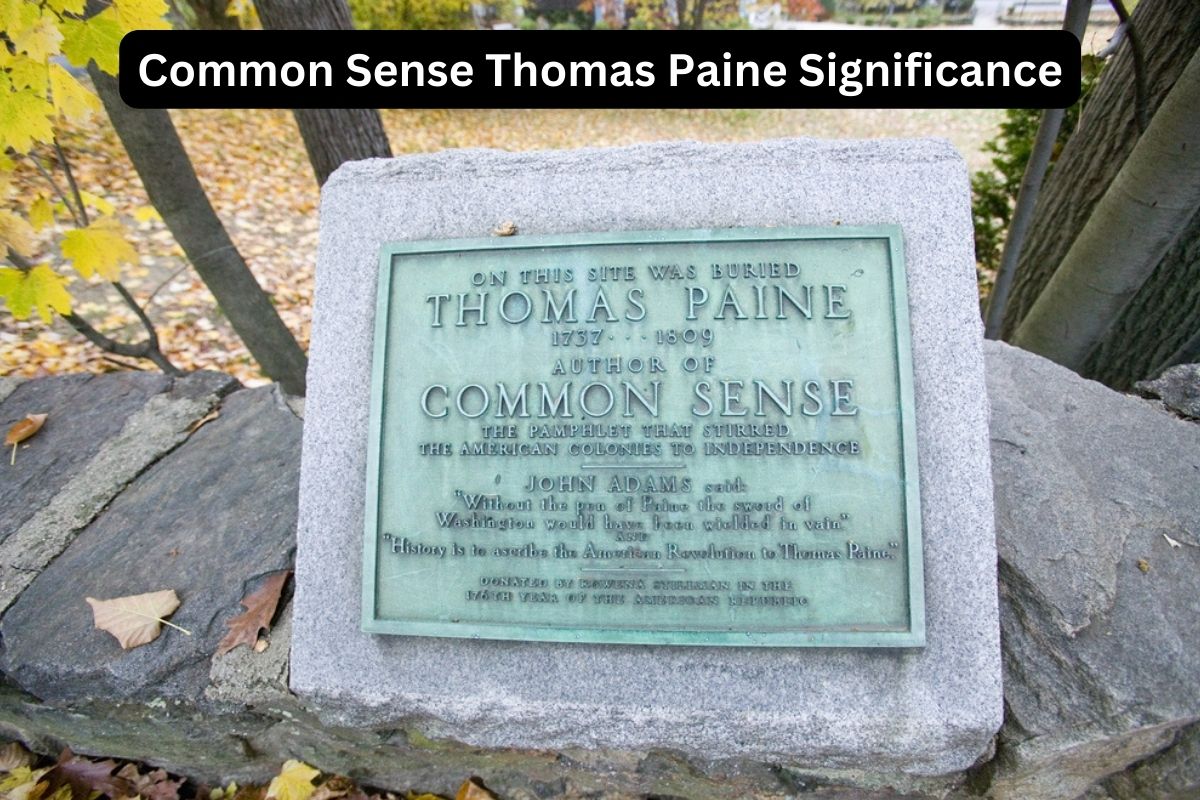

The pamphlet proved so influential that John Adams reportedly declared, “Without the pen of the author of ‘Common Sense,’ the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.”

Paine also claimed that the American colonies needed to break with England in order to survive and that there would never be a better moment in history for that to happen. He argued that America was related to Europe as a whole, not just England, and that it needed to freely trade with nations like France and Spain.

READ MORE: How Thomas Paine's 'Common Sense' Helped Inspire the American Revolution

The American Crisis

As the Revolutionary War began, Paine enlisted and met General George Washington , whom Paine served under.

The terrible condition of Washington’s troops during the winter of 1776 prompted Paine to publish a series of inspirational pamphlets known as “The American Crisis,” which opens with the famous line “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

Political Career of Thomas Paine

Starting in April 1777, Paine worked for two years as secretary to the Congressional Committee for Foreign Affairs and then became the clerk for the Pennsylvania Assembly at the end of 1779.

In March 1780, the assembly passed an abolition act that freed 6,000 enslaved people , to which Paine wrote the preamble.

Paine didn’t make much money from his government work and no money from his pamphlets–despite their unprecedented popularity–and in 1781 he approached Washington for help. Washington appealed to Congress to no avail, and went so far as to plead with all the state assemblies to pay Paine a reward for his work.

Only two states agreed: New York gifted Paine a house and a 277-acre estate in New Rochelle , while Pennsylvania awarded him a small monetary compensation.

The Revolution over, Paine explored other pursuits, including inventing a smokeless candle and designing bridges.

'Rights of Man'

Paine published his book Rights of Man in two parts in 1791 and 1792, a rebuttal of the writing of Irish political philosopher Edmund Burke and his attack on the French Revolution , which Paine supported.

Paine journeyed to Paris to oversee a French translation of the book in the summer of 1792. Paine’s visit was concurrent with the capture of Louis XVI , and he witnessed the monarch’s return to Paris.

Paine himself was threatened with execution by hanging when he was mistaken for an aristocrat, and he soon ran afoul of the Jacobins , who eventually ruled over France during the Reign of Terror , the bloodiest and most tumultuous years of the French Revolution.

In 1793 Paine was arrested for treason because of his opposition to the death penalty, most specifically the mass use of the guillotine and the execution of Louis XVI. He was detained in Luxembourg, where he began work on his next book, The Age of Reason .

Letter to George Washington

Released in 1794, partly thanks to the efforts of the then-new American minister to France, James Monroe , Paine became convinced that George Washington had conspired with French revolutionary politician Maximilien de Robespierre to have Paine imprisoned.

In retaliation, Paine published his “Letter to George Washington” attacking his former friend, accusing him of fraud and corruption in the military and as president.

But Washington was still very popular, and the letter diminished Paine’s popularity in America. The Federalists used the letter in accusations that Paine was a tool for French revolutionaries who also sought to overthrow the new American government.

'The Age of Reason'

Paine’s two-volume treatise on religion, The Age of Reason , was published in 1794 and 1795, with a third part appearing in 1802.

The first volume functions as a criticism of Christian theology and organized religion in favor of reason and scientific inquiry. Though often mistaken as an atheist text, The Age of Reason is actually an advocacy of deism and a belief in God.

The second volume is a critical analysis of the Old Testament and the New Testament of the Bible , questioning the divinity of Jesus Christ.

Immediately following the Washington debacle, however, The Age of Reason marked the end of Paine’s credibility in the United States, where he became largely despised.

Final Years and Death

By 1802, Paine was able to sail to Baltimore. Welcomed by President Thomas Jefferson , whom he had met in France, Paine was a recurring guest at the White House .

Still, newspapers denounced him and he was sometimes refused services. A minister in New York was dismissed because he shook hands with Paine.

In 1806, despite failing health, Paine worked on the third part of his “Age of Reason,” and also a criticism of Biblical prophesies called “An Essay on Dream.”

Paine died on June 8, 1809, in New York City , and was buried on his property in New Rochelle. On his deathbed, his doctor asked him if he wished to accept Jesus Christ before passing. “I have no wish to believe on that subject,” Paine replied before taking his final breath.

Paine's Remains

Paine’s remains were stolen in 1819 by British radical newspaperman William Cobbett and shipped to England in order to give Paine a more worthy burial. Paine’s bones were discovered by customs inspectors in Liverpool, but allowed to pass through.

Cobbett claimed that his plan was to display Paine’s bones in order to raise money for a proper memorial. He also fashioned jewelry made with hair removed from Paine’s skull for fundraising purposes.

Cobbett spent some time in Newgate Prison and after briefly being displayed, Paine’s bones ended up in Cobbett’s cellar until he died. Estate auctioneers refused to sell human remains and the bones became hard to trace.

Rumors of the remains’ whereabouts sprouted up through the years with little or no validation, including an Australian businessman who claimed to purchase the skull in the 1990s.

In 2001, the city of New Rochelle launched an effort to gather the remains and give Paine a final resting place. The Thomas Paine National Historical Association in New Rochelle claims to have possession of brain fragments and locks of hair.

Thomas Paine. Jerome D. Wilson and William F. Ricketson . Thomas Paine. A.J. Ayer . The Trouble With Tom: The Strange Afterlife and Times of Thomas Paine. Paul Collins . Rehabilitating Thomas Paine, Bit by Bony Bit. The New York Times .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- University Archives

- Special Collections

- Records Management

- Policies and Forms

- Sound Recordings

- Theses and Dissertations

- Selections From Our Digitized Collections

- Videos from the Archives

- Special Collections Exhibits

- University Archives Exhibits

- Research Guides

- Current Exhibits

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Past Exhibits

- Camelot Comes to Brandeis

- Special Collections Spotlight

- Library Home

- Degree Programs

- Majors and Minors

- Graduate Programs

- The Brandeis Core

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Brandeis Online

- Brandeis International Business School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Heller School for Social Policy and Management

- Rabb School of Continuing Studies

- Precollege Programs

- Faculty and Researcher Directory

- Brandeis Library

- Academic Calendar

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Summer School

- Financial Aid

- Research that Matters

- Resources for Researchers

- Brandeis Researchers in the News

- Provost Research Grants

- Recent Awards

- Faculty Research

- Student Research

- Centers and Institutes

- Office of the Vice Provost for Research

- Office of the Provost

- Housing/Community Living

- Campus Calendar

- Student Engagement

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Dean of Students Office

- Orientation

- Hiatt Career Center

- Spiritual Life

- Graduate Student Affairs

- Directory of Campus Contacts

- Division of Creative Arts

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

- Theater Arts Productions

- Brandeis Concert Series

- Public Sculpture at Brandeis

- Women's Studies Research Center

- Creative Arts Award

- Our Jewish Roots

- The Framework for the Future

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Distinguished Faculty

- Nobel Prize 2017

- Notable Alumni

- Administration

- Working at Brandeis

- Commencement

- Offices Directory

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections

Thomas paine's common sense, 1776.

Description by Kenneth Hong, Brandeis undergraduate and special contributor to the Special Collections Spotlight.

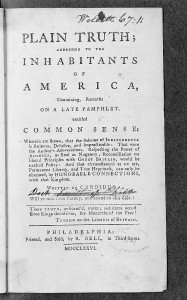

“Common Sense,” published on January 10, 1776, was originally printed in the city of Philadelphia, but was soon reprinted across America and Great Britain, and translated into German and Danish. [1] Thomas Paine’s pamphlet was first published anonymously, due to fears that its contents would be construed as treason; it was simply signed, “by an Englishman”. [2] The version housed at Brandeis University is one of the London printings, which had hiatuses, where words and phrases were omitted that were offensive to the British crown. [3] “Common Sense” sold about 120,000 copies in the first three months alone, being read in taverns and meeting houses across the 13 original colonies (the U.S. Census Bureau estimates the population in 1776 to be about 2.5 million and today to be about 320 million, that would make it proportionally equivalent to selling 15,000,000 copies today!) [4]

Paine used his writing as his weapon against the crown. With masterful language, Paine united the will of the colonists, planting the seed and giving hope and inspiration to fulfill the dream of America as an independent nation. The pamphlet was originally published without his name and all of the royalties associated with “Common Sense” were donated to the Continental Army. [9] It would appear that Paine was looking for neither fame nor fortune in writing a pamphlet that profoundly affected the creation of a nation. To Paine, these ideas came naturally, they were simply, “Common Sense.”

August 2 , 2015

- Powell, Jim. “ Thomas Paine, Passionate Pamphleteer for Liberty ,” in The Freeman, January 1, 1996. Foundation for Economic Education. Accessed March 11, 2015.

- Ibid .

- Entry for Call# D793.P147c . Brown University Library Online Catalog. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Harvey Kaye. “ Common Sense and the American Revolution. ” The Thomas Paine National Historical Association. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- “ Praise for Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776 as Reported in American Newspapers, ” in “America in Class: Making the Revolution: America, 1763-1791: Primary Source Collection.” The National Humanities Center. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Paine, Thomas. Common Sense. London: J. Almon, 1776.

- Kaye, Accessed February 10, 2015.

This essay, by Brandeis undergraduate Kenneth Hong, resulted from a Spring 2015 course for the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program, taught by Dr. Craig Bruce Smith, entitled, “Preserving Boston’s Past: Public History and Digital Humanities.” In this course, students worked with archival materials, developed website content, and produced their own commemoration event, “The 250th Anniversary of the Stamp Act: A Revolutionary Exhibit and Performance,” marking one of the first steps of the American Revolution.

The Transitional Year Program was established in 1968 and was renamed in 2013 for Myra Kraft ‘64, the late Brandeis alumna and trustee. It provides small classes and strong support systems for students who have had limitations to their precollege academic opportunities.

- About Our Collections

- Online Exhibits

- Events and In-Person Exhibits

- From the Brandeis Archives

Common Sense

THE BRADFORD EDITION, February 14, 1776

Man knows no Master save creating Heaven Or those whom choice and common good ordain. - Thomson.

INTRODUCTION

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong , gives it a superficial appearance of being right , and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.

As a long and violent abuse of power, is generally the Means of calling the right of it in question (and in Matters too which might never have been thought of, had not the Sufferers been aggravated into the inquiry) and as the King of England hath undertaken in his own Right , to support the Parliament in what he calls Theirs , and as the good people of this country are grievously oppressed by the combination, they have an undoubted privilege to inquire into the pretensions of both, and equally to reject the usurpation of either.

In the following sheets, the author hath studiously avoided every thing which is personal among ourselves. Compliments as well as censure to individuals make no part thereof. The wise, and the worthy, need not the triumph of a pamphlet; and those whose sentiments are injudicious, or unfriendly, will cease of themselves unless too much pains are bestowed upon their conversion.

The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances hath, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all Lovers of Mankind are affected, and in the Event of which, their Affections are interested. The laying a Country desolate with Fire and Sword, declaring War against the natural rights of all Mankind, and extirpating the Defenders thereof from the Face of the Earth, is the concern of every man to whom nature hath given the Power of feeling; of which Class, regardless of Party Censure, is the AUTHOR.

P.S. The Publication of this new Edition hath been delayed, with a View of taking notice (had it been necessary) of any attempt to refute the Doctrine of Independance: As no Answer hath yet appeared, it is now presumed that none will, the Time needful for getting such a performance ready for the Public being considerably past.

Who the Author of this Production is, is wholly unnecessary to the Public, as the Object for Attention is the Doctrine itself , not the Man . Yet it may not be unnecessary to say, That he is unconnected with any Party, and under no sort of Influence public or private, but the influence of reason and principle.

Philadelphia, February 14, 1776

OF THE ORIGIN AND DESIGN OF GOVERNMENT IN GENERAL. WITH CONCISE REMARKS ON THE ENGLISH CONSTITUTION

Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections, the latter negatively by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first a patron, the last a punisher.

Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government , which we might expect in a country without government , our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise. For were the impulses of conscience clear, uniform, and irresistibly obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do by the same prudence which in every other case advises him out of two evils to choose the least. Wherefore , security being the true design and end of government, it unanswerably follows, that whatever form thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expense and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others.

In order to gain a clear and just idea of the design and end of government, let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the earth, unconnected with the rest, they will then represent the first peopling of any country, or of the world. In this state of natural liberty, society will be their first thought. A thousand motives will excite them thereto, the strength of one man is so unequal to his wants, and his mind so unfitted for perpetual solitude, that he is soon obliged to seek assistance and relief of another, who in his turn requires the same. Four or five united would be able to raise a tolerable dwelling in the midst of a wilderness, but one man might labor out of the common period of life without accomplishing any thing; when he had felled his timber he could not remove it, nor erect it after it was removed; hunger in the mean time would urge him from his work, and every different want call him a different way. Disease, nay even misfortune would be death, for though neither might be mortal, yet either would disable him from living, and reduce him to a state in which he might rather be said to perish than to die.

Thus necessity, like a gravitating power, would soon form our newly arrived emigrants into society, the reciprocal blessings of which, would supersede, and render the obligations of law and government unnecessary while they remained perfectly just to each other; but as nothing but heaven is impregnable to vice, it will unavoidably happen, that in proportion as they surmount the first difficulties of emigration, which bound them together in a common cause, they will begin to relax in their duty and attachment to each other; and this remissness will point out the necessity of establishing some form of government to supply the defect of moral virtue.

Some convenient tree will afford them a State House, under the branches of which, the whole colony may assemble to deliberate on public matters. It is more than probable that their first laws will have the title only of REGULATIONS, and be enforced by no other penalty than public disesteem. In this first parliament every man, by natural right, will have a seat.

But as the colony increases, the public concerns will increase likewise, and the distance at which the members may be separated, will render it too inconvenient for all of them to meet on every occasion as at first, when their number was small, their habitations near, and the public concerns few and trifling. This will point out the convenience of their consenting to leave the legislative part to be managed by a select number chosen from the whole body, who are supposed to have the same concerns at stake which those who appointed them, and who will act in the same manner as the whole body would act, were they present. If the colony continues increasing, it will become necessary to augment the number of the representatives, and that the interest of every part of the colony may be attended to, it will be found best to divide the whole into convenient parts, each part sending its proper number; and that the elected might never form to themselves an interest separate from the electors , prudence will point out the propriety of having elections often; because as the elected might by that means return and mix again with the general body of the electors in a few months, their fidelity to the public will be secured by the prudent reflection of not making a rod for themselves. And as this frequent interchange will establish a common interest with every part of the community, they will mutually and naturally support each other, and on this (not on the unmeaning name of king) depends the strength of government, and the happiness of the governed.

Here then is the origin and rise of government; namely, a mode rendered necessary by the inability of moral virtue to govern the world; here too is the design and end of government, viz. freedom and security. And however our eyes may be dazzled with show, or our ears deceived by sound; however prejudice may warp our wills, or interest darken our understanding, the simple voice of nature and of reason will say, it is right.

I draw my idea of the form of government from a principle in nature, which no art can overturn, viz. that the more simple any thing is, the less liable it is to be disordered; and the easier repaired when disordered; and with this maxim in view, I offer a few remarks on the so much boasted constitution of England. That it was noble for the dark and slavish times in which it was erected, is granted. When the world was overrun with tyranny the least remove therefrom was a glorious rescue. But that it is imperfect, subject to convulsions, and incapable of producing what it seems to promise, is easily demonstrated.

Absolute governments, (tho’ the disgrace of human nature) have this advantage with them, that they are simple; if the people suffer, they know the head from which their suffering springs, know likewise the remedy, and are not bewildered by a variety of causes and cures. But the constitution of England is so exceedingly complex, that the nation may suffer for years together without being able to discover in which part the fault lies; some will say in one and some in another, and every political physician will advise a different medicine.

I know it is difficult to get over local or long standing prejudices, yet if we will suffer ourselves to examine the component parts of the English constitution, we shall find them to be the base remains of two ancient tyrannies, compounded with some new republican materials.

First — The remains of monarchial tyranny in the person of the king.

Secondly — The remains of aristocratical tyranny in the persons of the peers.

Thirdly — The new republican materials in the persons of the Commons, on whose virtue depends the freedom of England.

The two first, by being hereditary, are independent of the people; wherefore in a constitutional sense they contribute nothing towards the freedom of the state.

To say that the constitution of England is a union of three powers reciprocally checking each other, is farcical, either the words have no meaning, or they are flat contradictions.

To say that the commons is a check upon the king, presupposes two things:

First — That the king is not to be trusted without being looked after, or in other words, that a thirst for absolute power is the natural disease of monarchy.

Secondly — That the commons, by being appointed for that purpose, are either wiser or more worthy of confidence than the crown.

But as the same constitution which gives the commons a power to check the king by withholding the supplies, gives afterwards the king a power to check the commons, by empowering him to reject their other bills; it again supposes that the king is wiser than those whom it has already supposed to be wiser than him. A mere absurdity!

There is something exceedingly ridiculous in the composition of monarchy; it first excludes a man from the means of information, yet empowers him to act in cases where the highest judgment is required. The state of a king shuts him from the world, yet the business of a king requires him to know it thoroughly; wherefore the different parts, by unnaturally opposing and destroying each other, prove the whole character to be absurd and useless.

Some writers have explained the English constitution thus; the king, say they, is one, the people another; the peers are an house in behalf of the king; the commons in behalf of the people; but this hath all the distinctions of a house divided against itself; and though the expressions be pleasantly arranged, yet when examined, they appear idle and ambiguous; and it will always happen, that the nicest construction that words are capable of, when applied to the description of some thing which either cannot exist, or is too incomprehensible to be within the compass of description, will be words of sound only, and though they may amuse the ear, they cannot inform the mind, for this explanation includes a previous question, viz. How came the king by the power which the people are afraid to trust, and always obliged to check? Such a power could not be the gift of a wise people, neither can any power, which needs checking , be from God; yet the provision, which the constitution makes, supposes such a power to exist.

But the provision is unequal to the task; the means either cannot or will not accomplish the end, and the whole affair is a felo de se; for as the greater weight will always carry up the less, and as all the wheels of a machine are put in motion by one, it only remains to know which power in the constitution has the most weight, for that will govern; and though the others, or a part of them, may clog, or, as the phrase is, check the rapidity of its motion, yet so long as they cannot stop it, their endeavors will be ineffectual; the first moving power will at last have its way, and what it wants in speed, is supplied by time.

That the crown is this overbearing part in the English constitution, needs not be mentioned, and that it derives its whole consequence merely from being the giver of places and pensions, is self-evident, wherefore, though we have been wise enough to shut and lock a door against absolute monarchy, we at the same time have been foolish enough to put the crown in possession of the key.

The prejudice of Englishmen in favour of their own government by king, lords, and commons, arises as much or more from national pride than reason. Individuals are undoubtedly safer in England than in some other countries, but the will of the king is as much the law of the land in Britain as in France, with this difference, that instead of proceeding directly from his mouth, it is handed to the people under the more formidable shape of an act of parliament. For the fate of Charles the first hath only made kings more subtle $mdash; not more just.

Wherefore, laying aside all national pride and prejudice in favor of modes and forms, the plain truth is, that it is wholly owing to the constitution of the people, and not to the constitution of the government that the crown is not as oppressive in England as in Turkey.

An inquiry into the constitutional errors in the English form of government is at this time highly necessary, for as we are never in a proper condition of doing justice to others, while we continue under the influence of some leading partiality, so neither are we capable of doing it to ourselves while we remain fettered by any obstinate prejudice. And as a man. who is attached to a prostitute, is unfitted to choose or judge a wife, so any prepossession in favour of a rotten constitution of government will disable us from discerning a good one.

OF MONARCHY AND HEREDITARY SUCCESSION

Mankind being originally equals in the order of creation, the equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance; the distinctions of rich, and poor, may in a great measure be accounted for, and that without having recourse to the harsh, ill-sounding names of oppression and avarice. Oppression is often the consequence , but seldom or never the means of riches; and though avarice will preserve a man from being necessitously poor, it generally makes him too timorous to be wealthy.

But there is another and greater distinction for which no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned, and that is, the distinction of men into kings and subjects. Male and female are the distinctions of nature, good and bad the distinctions of heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth inquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.

In the early ages of the world, according to the scripture chronology, there were no kings; the consequence of which was there were no wars; it is the pride of kings which throw mankind into confusion. Holland without a king hath enjoyed more peace for this last century than any of the monarchial governments in Europe. Antiquity favors the same remark; for the quiet and rural lives of the first patriarchs hath a happy something in them, which vanishes away when we come to the history of Jewish royalty.

Government by kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom. It was the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry. The Heathens paid divine honors to their deceased kings, and the christian world hath improved on the plan, by doing the same to their living ones. How impious is the title of sacred majesty applied to a worm, who in the midst of his splendor is crumbling into dust!

As the exalting one man so greatly above the rest cannot be justified on the equal rights of nature, so neither can it be defended on the authority of scripture; for the will of the Almighty, as declared by Gideon and the prophet Samuel, expressly disapproves of government by kings. All anti-monarchical parts of scripture have been very smoothly glossed over in monarchical governments, but they undoubtedly merit the attention of countries which have their governments yet to form. “Render unto Cesar the things which are Cesar’s” is the scripture doctrine of courts, yet it is no support of monarchical government, for the Jews at that time were without a king, and in a state of vassalage to the Romans.

Now three thousand years passed away from the Mosaic account of the creation, till the Jews under a national delusion requested a king. Till then their form of government (except in extraordinary cases, where the Almighty interposed) was a kind of Republic administred by a judge and the elders of the tribes. Kings they had none, and it was held sinful to acknowledge any being under that title but the Lord of Hosts. And when a man seriously reflects on the idolatrous homage which is paid to the persons of Kings, he need not wonder that the Almighty, ever jealous of his honor, should disapprove of a form of government which so impiously invades the prerogative of heaven.

Monarchy is ranked in scripture as one of the sins of the Jews, for which a curse in reserve is denounced against them. The history of that transaction is worth attending to.

The children of Israel being oppressed by the Midianites, Gideon marched against them with a small army, and victory, through the divine interposition, decided in his favour. The Jews, elate with success, and attributing it to the generalship of Gideon, proposed making him a king, saying, Rule thou over us, thou and thy son, and thy son’’s son . Here was temptation in its fullest extent; not a kingdom only, but an hereditary one, but Gideon in the piety of his soul replied, I will not rule over you, neither shall my son rule over you . The Lord shall rule over you. Words need not be more explicit; Gideon doth not decline the honor, but denieth their right to give it; neither doth he compliment them with invented declarations of his thanks, but in the positive style of a prophet charges them with disaffection to their proper Sovereign, the King of heaven.

About one hundred and thirty years after this, they fell again into the same error. The hankering which the Jews had for the idolatrous customs of the Heathens, is something exceedingly unaccountable; but so it was, that laying hold of the misconduct of Samuel’s two sons, who were entrusted with some secular concerns, they came in an abrupt and clamorous manner to Samuel, saying, Behold thou art old, and thy sons walk not in thy ways, now make us a king to judge us like all the other nations . And here we cannot but observe that their motives were bad, viz. that they might be like unto other nations, i.e. the Heathens, whereas their true glory laid in being as much unlike them as possible. But the thing displeased Samuel when they said, Give us a king to judge us; and Samuel prayed unto the Lord, and the Lord said unto Samuel, Hearken unto the voice of the people in all that they say unto thee, for they have not rejected thee, but they have rejected me , THAT I SHOULD NOT REIGN OVER THEM. According to all the works which they have done since the day that I brought them up out of Egypt, even unto this day; wherewith they have forsaken me and served other Gods; so do they also unto thee. Now therefore hearken unto their voice, howbeit, protest solemnly unto them and shew them the manner of the king that shall reign over them, i.e. not of any particular king, but the general manner of the kings of the earth, whom Israel was so eagerly copying after. And notwithstanding the great distance of time and difference of manners, the character is still in fashion. And Samuel told all the words of the Lord unto the people, that asked of him a king. And he said, This shall be the manner of the king that shall reign over you; he will take your sons and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen, and some shall run before his chariots (this description agrees with the present mode of impressing men) and he will appoint him captains over thousands and captains over fifties, will set them to ear his ground and to reap his harvest, and to make his instruments of war, and instruments of his chariots; and he will take your daughters to be confectionaries, and to be cooks and to be bakers (this describes the expense and luxury as well as the oppression of kings) and he will take your fields and your olive yards, even the best of them, and give them to his servants. And he will take the tenth of your seed, and of your vineyards, and give them to his officers and to his servants (by which we see that bribery, corruption, and favoritism are the standing vices of kings) and he will take the tenth of your men servants, and your maid servants, and your goodliest young men and your asses, and put them to his work; and he will take the tenth of your sheep, and ye shall be his servants, and ye shall cry out in that day because of your king which ye shall have chosen , and the Lord will not hear you in that day. This accounts for the continuation of monarchy; neither do the characters of the few good kings which have lived since, either sanctify the title, or blot out the sinfulness of the origin; the high encomium given of David takes no notice of him officially as a king , but only as a man after God’s own heart. Nevertheless the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel, and they said, Nay, but we will have a king over us, that we may be like all the nations, and that our king may judge us, and go out before us, and fight our battles . Samuel continued to reason with them, but to no purpose; he set before them their ingratitude, but all would not avail; and seeing them fully bent on their folly, he cried out, I will call unto the Lord, and he shall send thunder and rain (which then was a punishment, being in the time of wheat harvest) that ye may perceive and see that your wickedness is great which ye have done in the sight of the Lord , in asking you a king. So Samuel called unto the Lord, and the Lord sent thunder and rain that day, and all the people greatly feared the Lord and Samuel. And all the people said unto Samuel, Pray for thy servants unto the Lord thy God that we die not, for we have added unto our sins this evil, to ask a king. These portions of scripture are direct and positive. They admit of no equivocal construction. That the Almighty hath here entered his protest against monarchical government is true, or the scripture is false. And a man hath good reason to believe that there is as much of king-craft, as priest-craft, in withholding the scripture from the public in Popish countries. For monarchy in every instance is the Popery of government.

To the evil of monarchy we have added that of hereditary succession; and as the first is a degradation and lessening of ourselves, so the second, claimed as a matter of right, is an insult and an imposition on posterity. For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever, and though himself might deserve some decent degree of honors of his contemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them. One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in kings, is, that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion .

Secondly, as no man at first could possess any other public honors than were bestowed upon him, so the givers of those honors could have no power to give away the right of posterity, and though they might say, “We choose you for our head,” they could not, without manifest injustice to their children, say “that your children and your children’s children shall reign over ours for ever.” Because such an unwise, unjust, unnatural compact might (perhaps) in the next succession put them under the government of a rogue or a fool. Most wise men, in their private sentiments, have ever treated hereditary right with contempt; yet it is one of those evils, which when once established is not easily removed; many submit from fear, others from superstition, and the more powerful part shares with the king the plunder of the rest.

This is supposing the present race of kings in the world to have had an honorable origin; whereas it is more than probable, that could we take off the dark covering of antiquity, and trace them to their first rise, that we should find the first of them nothing better than the principal ruffian of some restless gang, whose savage manners or pre-eminence in subtility obtained him the title of chief among plunderers; and who by increasing in power, and extending his depredations, over-awed the quiet and defenceless to purchase their safety by frequent contributions. Yet his electors could have no idea of giving hereditary right to his descendants, because such a perpetual exclusion of themselves was incompatible with the free and unrestrained principles they professed to live by. Wherefore, hereditary succession in the early ages of monarchy could not take place as a matter of claim, but as something casual or complimental; but as few or no records were extant in those days, and traditional history stuffed with fables, it was very easy, after the lapse of a few generations, to trump up some superstitious tale, conveniently timed, Mahomet like, to cram hereditary right down the throats of the vulgar. Perhaps the disorders which threatened, or seemed to threaten, on the decease of a leader and the choice of a new one (for elections among ruffians could not be very orderly) induced many at first to favor hereditary pretensions; by which means it happened, as it hath happened since, that what at first was submitted to as a convenience, was afterwards claimed as a right.

England, since the conquest, hath known some few good monarchs, but groaned beneath a much larger number of bad ones; yet no man in his senses can say that their claim under William the Conqueror is a very honorable one. A French bastard landing with an armed banditti, and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives, is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original. $mdash; It certainly hath no divinity in it. However, it is needless to spend much time in exposing the folly of hereditary right; if there are any so weak as to believe it, let them promiscuously worship the ass and lion, and welcome. I shall neither copy their humility, nor disturb their devotion.

Yet I should be glad to ask how they suppose kings came at first? The question admits but of three answers, viz. either by lot, by election, or by usurpation. If the first king was taken by lot, it establishes a precedent for the next, which excludes hereditary succession. Saul was by lot, yet the succession was not hereditary, neither does it appear from that transaction there was any intention it ever should be. If the first king of any country was by election, that likewise establishes a precedent for the next; for to say, that the right of all future generations is taken away, by the act of the first electors, in their choice not only of a king, but of a family of kings for ever, hath no parallel in or out of scripture but the doctrine of original sin, which supposes the free will of all men lost in Adam; and from such comparison, and it will admit of no other, hereditary succession can derive no glory. For as in Adam all sinned, and as in the first electors all men obeyed; as in the one all mankind we were subjected to Satan, and in the other to Sovereignty; as our innocence was lost in the first, and our authority in the last; and as both disable us from reassuming some former state and privilege, it unanswerably follows that original sin and hereditary succession are parallels. Dishonorable rank! Inglorious connexion! Yet the most subtile sophist cannot produce a juster simile.

As to usurpation, no man will be so hardy as to defend it; and that William the Conqueror was an usurper is a fact not to be contradicted. The plain truth is, that the antiquity of English monarchy will not bear looking into.

But it is not so much the absurdity as the evil of hereditary succession which concerns mankind. Did it ensure a race of good and wise men it would have the seal of divine authority, but as it opens a door to the foolish , the wicked , and the improper , it hath in it the nature of oppression. Men who look upon themselves born to reign, and others to obey, soon grow insolent; selected from the rest of mankind their minds are early poisoned by importance; and the world they act in differs so materially from the world at large, that they have but little opportunity of knowing its true interests, and when they succeed to the government are frequently the most ignorant and unfit of any throughout the dominions.

Another evil which attends hereditary succession is, that the throne is subject to be possessed by a minor at any age; all which time the regency, acting under the cover a king, have every opportunity and inducement to betray their trust. The same national misfortune happens, when a king worn out with age and infirmity, enters the last stage of human weakness. In both these cases the public becomes a prey to every miscreant, who can tamper successfully with the follies either of age or infancy.

The most plausible plea, which hath ever been offered in favour of hereditary succession, is, that it preserves a nation from civil wars; and were this true, it would be weighty; whereas, it is the most barefaced falsity ever imposed upon mankind. The whole history of England disowns the fact. Thirty kings and two minors have reigned in that distracted kingdom since the conquest, in which time there have been (including the Revolution) no less than eight civil wars and nineteen rebellions. Wherefore instead of making for peace, it makes against it, and destroys the very foundation it seems to stand on.

The contest for monarchy and succession, between the houses of York and Lancaster, laid England in a scene of blood for many years. Twelve pitched battles, besides skirmishes and sieges, were fought between Henry and Edward. Twice was Henry prisoner to Edward, who in his turn was prisoner to Henry. And so uncertain is the fate of war and the temper of a nation, when nothing but personal matters are the ground of a quarrel, that Henry was taken in triumph from a prison to a palace, and Edward obliged to fly from a palace to a foreign land; yet, as sudden transitions of temper are seldom lasting, Henry in his turn was driven from the throne, and Edward recalled to succeed him. The parliament always following the strongest side.

This contest began in the reign of Henry the Sixth, and was not entirely extinguished till Henry the Seventh, in whom the families were united. Including a period of 67 years, viz. from 1422 to 1489.

In short, monarchy and succession have laid (not this or that kingdom only) but the world in blood and ashes. ’Tis a form of government which the word of God bears testimony against, and blood will attend it.

If we inquire into the business of a king, we shall find that in some countries they have none; and after sauntering away their lives without pleasure to themselves or advantage to the nation, withdraw from the scene, and leave their successors to tread the same idle ground. In absolute monarchies the whole weight of business, civil and military, lies on the king; the children of Israel in their request for a king, urged this plea “that he may judge us, and go out before us and fight our battles.” But in countries where he is neither a judge nor a general, as in England, a man would be puzzled to know what is his business.

The nearer any government approaches to a republic the less business there is for a king. It is somewhat difficult to find a proper name for the government of England. Sir William Meredith calls it a republic; but in its present state it is unworthy of the name, because the corrupt influence of the crown, by having all the places in its disposal, hath so effectually swallowed up the power, and eaten out the virtue of the house of commons (the republican part in the constitution) that the government of England is nearly as monarchical as that of France or Spain. Men fall out with names without understanding them. For it is the republican and not the monarchical part of the constitution of England which Englishmen glory in, viz. the liberty of choosing an house of Commons from out of their own body $mdash; and it is easy to see that when republican virtue fails, slavery ensues. Why is the constitution of England sickly, but because monarchy hath poisoned the republic, the crown hath engrossed the commons?

In England a king hath little more to do than to make war and give away places; which in plain terms, is to impoverish the nation and set it together by the ears. A pretty business indeed for a man to be allowed eight hundred thousand sterling a year for, and worshipped into the bargain! Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

THOUGHTS ON THE PRESENT STATE OF AMERICAN AFFAIRS

In the following pages I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense; and have no other preliminaries to settle with the reader, than that he will divest himself of prejudice and prepossession, and suffer his reason and his feelings to determine for themselves; that he will put on , or rather that he will not put off , the true character of a man, and generously enlarge his views beyond the present day.

Volumes have been written on the subject of the struggle between England and America. Men of all ranks have embarked in the controversy, from different motives, and with various designs; but all have been ineffectual, and the period of debate is closed. Arms, as the last resource, decide this contest; the appeal was the choice of the king, and the continent hath accepted the challenge.

It hath been reported of the late Mr. Pelham (who tho’ an able minister was not without his faults) that on his being attacked in the house of commons, on the score, that his measures were only of a temporary kind, replied, “ they will last my time. ” Should a thought so fatal and unmanly possess the colonies in the present contest, the name of ancestors will be remembered by future generations with detestation.

The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ’Tis not the affair of a city, a county, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent $mdash; of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed-time of continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new aera for politics is struck; a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the nineteenth of April, i.e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which, though proper then, are superseded and useless now. Whatever was advanced by the advocates on either side of the question then, terminated in one and the same point. viz. a union with Great-Britain; the only difference between the parties was the method of effecting it; the one proposing force, the other friendship; but it hath so far happened that the first hath failed, and the second hath withdrawn her influence.

As much hath been said of the advantages of reconciliation, which, like an agreeable dream, hath passed away and left us as we were, it is but right, that we should examine the contrary side of the argument, and inquire into some of the many material injuries which these colonies sustain, and always will sustain, by being connected with, and dependant on Great-Britain. To examine that connexion and dependance, on the principles of nature and common sense, to see what we have to trust to, if separated, and what we are to expect, if dependant.

I have heard it asserted by some, that as America hath flourished under her former connexion with Great-Britain that the same connexion is necessary towards her future happiness, and will always have the same effect. Nothing can be more fallacious than this kind of argument. We may as well assert that because a child has thrived upon milk, that it is never to have meat, or that the first twenty years of our lives is to become a precedent for the next twenty. But even this is admitting more than is true, for I answer roundly, that America would have flourished as much, and probably much more, had no European power had any thing to do with her. The commerce, by which she hath enriched herself are the necessaries of life, and will always have a market while eating is the custom of Europe.

But she has protected us, say some. That she has engrossed us is true, and defended the continent at our expense as well as her own is admitted, and she would have defended Turkey from the same motive, viz. the sake of trade and dominion.

Alas, we have been long led away by ancient prejudices, and made large sacrifices to superstition. We have boasted the protection of Great- Britain, without considering, that her motive was interest not attachment ; that she did not protect us from our enemies on our account , but from her enemies on her own account , from those who had no quarrel with us on any other account , and who will always be our enemies on the same account . Let Britain wave her pretensions to the continent, or the continent throw off the dependance, and we should be at peace with France and Spain were they at war with Britain. The miseries of Hanover last war ought to warn us against connexions.

It has lately been asserted in parliament, that the colonies have no relation to each other but through the parent country, i.e. that Pennsylvania and the Jerseys, and so on for the rest, are sister colonies by the way of England; this is certainly a very round-about way of proving relationship, but it is the nearest and only true way of proving enmity enemyship, if I may so call it. France and Spain never were, nor perhaps ever will be our enemies as Americans , but as our being the subjects of Great-Britain .

But Britain is the parent country, say some. Then the more shame upon her conduct. Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families; wherefore the assertion, if true, turns to her reproach; but it happens not to be true, or only partly so, and the phrase parent or mother country hath been jesuitically adopted by the king and his parasites, with a low papistical design of gaining an unfair bias on the credulous weakness of our minds. Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither have they fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still.

In this extensive quarter of the globe, we forget the narrow limits of three hundred and sixty miles (the extent of England) and carry our friendship on a larger scale; we claim brotherhood with every European christian, and triumph in the generosity of the sentiment.

It is pleasant to observe by what regular gradations we surmount the force of local prejudice, as we enlarge our acquaintance with the world. A man born in any town in England divided into parishes, will naturally associate most with his fellow parishioners (because their interests in many cases will be common) and distinguish him by the name of neighbour ; if he meet him but a few miles from home, he drops the narrow idea of a street, and salutes him by the name of townsman ; if he travel out of the county, and meet him in any other, he forgets the minor divisions of street and town, and calls him countryman , i.e., country-man ; but if in their foreign excursions they should associate in France or any other part of Europe , their local remembrance would be enlarged into that of Englishman . And by a just parity of reasoning, all Europeans meeting in America, or any other quarter of the globe, are countrymen ; for England, Holland, Germany, or Sweden, when compared with the whole, stand in the same places on the larger scale, which the divisions of street, town, and county do on the smaller ones; distinctions too limited for continental minds. Not one third of the inhabitants, even of this province, are of English descent. Wherefore I reprobate the phrase of parent or mother country applied to England only, as being false, selfish, narrow and ungenerous.

But admitting, that we were all of English descent, what does it amount to? Nothing. Britain, being now an open enemy, extinguishes every other name and title: And to say that reconciliation is our duty, is truly farcical. The first king of England, of the present line (William the Conqueror) was a Frenchman, and half the Peers of England are descendants from the same country; therefore, by the same method of reasoning, England ought to be governed by France.

Much hath been said of the united strength of Britain and the colonies, that in conjunction they might bid defiance to the world. But this is mere presumption; the fate of war is uncertain, neither do the expressions mean any thing; for this continent would never suffer itself to be drained of inhabitants, to support the British arms in either Asia, Africa, or Europe.

Besides what have we to do with setting the world at defiance? Our plan is commerce, and that, well attended to, will secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe; because, it is the interest of all Europe to have America a free port . Her trade will always be a protection, and her barrenness of gold and silver secure her from invaders.

I challenge the warmest advocate for reconciliation, to shew, a single advantage that this continent can reap, by being connected with Great Britain. I repeat the challenge, not a single advantage is derived. Our corn will fetch its price in any market in Europe, and our imported goods must be paid for buy them where we will.

But the injuries and disadvantages we sustain by that connection, are without number; and our duty to mankind at large, as well as to ourselves, instruct us to renounce the alliance: Because, any submission to, or dependance on Great-Britain, tends directly to involve this continent in European wars and quarrels; and sets us at variance with nations, who would otherwise seek our friendship, and against whom, we have neither anger nor complaint. As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no partial connection with any part of it. It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions, which she never can do, while by her dependence on Britain, she is made the make-weight in the scale of British politics.