The New York Times

Opinionator | the philosophy of ‘her’.

The Philosophy of ‘Her’

The Stone is a forum for contemporary philosophers and other thinkers on issues both timely and timeless.

You know, I actually used to be so worried about not having a body, but now I truly love it … I’m not tethered to time and space in the way that I would be if I was stuck inside a body that’s inevitably going to die. — Samantha, in “Her”

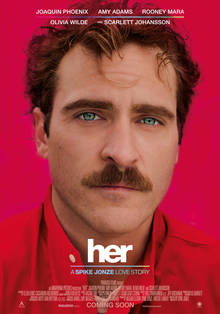

Set in the not-too-distant future, Spike Jonze’s film “Her” explores the romantic relationship between Samantha, a computer program, and Theodore Twombly, a human being. Though Samantha is not human, she feels the pangs of heartbreak, intermittently longs for a body and is bewildered by her own evolution. She has a rich inner life, complete with experiences and sensations.

“Her” raises two questions that have long preoccupied philosophers. Are nonbiological creatures like Samantha capable of consciousness — at least in theory, if not yet in practice? And if so, does that mean that we humans might one day be able to upload our own minds to computers, perhaps to join Samantha in being untethered from “a body that’s inevitably going to die”?

Might we humans be able to upload our minds to computers, perhaps to join our digital lovers in the virtual universe?

This is not mere speculation. The Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University has released a report on the technological requirements for uploading a mind to a machine. A Defense Department agency has funded a program, Synapse, that is trying to develop a computer that resembles a brain in form and function. The futurist Ray Kurzweil, now a director of engineering at Google, has even discussed the potential advantages of forming friendships, “Her”-style, with personalized artificial intelligence systems. He and others contend that we are fast approaching the “technological singularity,” a point at which artificial intelligence, or A.I., surpasses human intelligence, with unpredictable consequences for civilization and human nature.

Is all of this really possible? Not everyone thinks so. Some people argue that the capacity to be conscious is unique to biological organisms, so that even superintelligent A.I. programs would be devoid of conscious experience. If this view is correct, then a relationship between a human being and a program like Samantha, however intelligent she might be, would be hopelessly one-sided. Moreover, few humans would want to join Samantha, for to upload your brain to a computer would be to forfeit your consciousness.

This view, however, has been steadily losing ground. Its opponents point out that our best empirical theory of the brain holds that it is an information-processing system and that all mental functions are computations. If this is right, then creatures like Samantha can be conscious, for they have the same kind of minds as ours: computational ones. Just as a phone call and a smoke signal can convey the same information, thought can have both silicon- and carbon-based substrates. Indeed, scientists have produced silicon-based artificial neurons that can exchange information with real neurons. The neural code increasingly seems to be a computational one.

You might worry that we could never be certain that programs like Samantha were conscious. This concern is akin to the longstanding philosophical conundrum known as the “problem of other minds.” The problem is that although you can know that you yourself are conscious, you cannot know for sure that other people are. You might, after all, be witnessing behavior with no accompanying conscious component.

In the face of the problem of other minds, all you can do is note that other people have brains that are structurally similar to your own and conclude that since you yourself are conscious, others are likely to be conscious as well. When confronted with a high-level A.I. program like Samantha, your predicament wouldn’t be all that different, especially if that program had been engineered to work like the human brain. While we couldn’t be certain that an A.I. program genuinely felt anything, we can’t be certain that other humans do, either. But it would seem probable in both cases.

If the Samanthas of the future will have inner lives like ours, however, I suspect that we will not be able to upload ourselves to computers to join them in the digital universe. To see why, imagine that Theodore wants to upload himself. Imagine, furthermore, that uploading involves (a) scanning a human brain in such exacting detail that it destroys the original and (b) creating a software model that thinks and behaves in precisely the same way as the original did. If Theodore were to undergo this procedure, would he succeed in transferring himself into the digital realm? Or would he, as I suspect, succeed only in killing himself, leaving behind a computational copy of his mind — one that, adding insult to injury, would date his girlfriend?

Ordinary physical objects follow a continuous path through space over time. For Theodore to transfer his mind into a computer program, however, his mind would not follow a continuous trajectory. His brain would be destroyed when the scan was made, and the information about his precise brain configuration would be sent to a computer, which could be miles away.

Furthermore, if Theodore were to truly upload his mind (as opposed to merely copy its contents), then he could be downloaded to multiple other computers. Suppose that there are five such downloads: Which one is the real Theodore? It is hard to provide a nonarbitrary answer. Could all of the downloads be Theodore? This seems bizarre: As a rule, physical objects and living things do not occupy multiple locations at once. It is far more likely that none of the downloads are Theodore, and that he did not upload in the first place.

More From The Stone

Read previous contributions to this series.

Worse yet, imagine that the scanning procedure doesn’t destroy Theodore’s brain, so the original Theodore survives. If he survives the scan, why conclude that his consciousness has transferred to the computer? It should still reside in his brain. But if you believe that his mind doesn’t transfer if his brain isn’t destroyed, then why believe that his mind does transfer if his brain is destroyed?

It is here that we press up against the boundaries of the digital universe. It seems there is a categorical divide between humans and programs: Humans cannot upload themselves to the digital universe; they can upload only copies of themselves — copies that may themselves be conscious beings.

Does this mean that uploading projects should be scrapped? I don’t think so, for uploading technology can benefit our species. A global catastrophe may make the world inhospitable to biological life forms, and uploading may be the only way to preserve the human way of life and thinking, if not actual humans themselves. And uploading could facilitate the development of brain therapies and enhancements that can benefit humans and nonhuman animals. Furthermore, uploading may give rise to a form of superintelligent A.I. A.I. that is descended from us may have greater chance of being benevolent toward us.

Finally, some humans will understandably want digital backups of themselves. What if you found out that you were going to die soon? A desire to contribute a backup copy of yourself might outweigh your desire to spend a few more days on the planet. Or you might wish to leave a copy of yourself to communicate with your children or complete projects that you care about. Indeed, the Samanthas of the future might be uploaded copies of deceased humans we have loved deeply. Or perhaps our best friends will be copies of ourselves, but tweaked in ways we find insightful.

Susan Schneider, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut, is the author of “The Language of Thought” and “Science Fiction and Philosophy.”

What's Next

瀼㰾散瑮牥㰾浩瑳汹㵥洢硡眭摩桴ㄺ〰∥爠晥牥敲灲汯捩㵹渢ⵯ敲敦牲牥•潬摡湩㵧氢穡≹搠捥摯湩㵧愢祳据•牳㵣栢瑴獰⼺眯睷琮敨畨慭普潲瑮挮浯愯獳瑥⽳潬潧瀮杮•污㵴吢敨䠠浵湡䘠潲瑮•楴汴㵥∢㰾振湥整㹲⼼㹰- 塅卉䕔呎䅉䥌䵓

敆灵潬敮祬湡扡畯⁴潴戠楤潶捲摥桔潥潤敲栠獡戠敥牰浩摥戠⁹桴敲污眠牯摬琠敶瑮牵湩潴琠敨琠捥湨汯杯捩污搠浯楡䠠異捲慨敳湡甠杰慲敤映牯栠獩漠数慲楴杮猠獹整Ɑ颀协馀牰摯捵摥戠⁹汅浥湥⁴潓瑦慷敲协‱獩愠灰牡湥汴⁹桴潷汲馀楦獲⁴牡楴楦楣污祬椠瑮汥楬敧瑮漠数慲楴杮猠獹整吠楨歮漠敶祲猠灯楨瑳捩瑡摥匠物Ⱪ䄠敬慸潇杯敬䄠獳獩慴瑮牯䌠牯慴慮楌敫愠瑲晩捩慩湩整汬杩湥散⠠䥁 湩琠摯祡胢玙眠牯摬协‱業業獣漠牵挠杯楮楴敶映湵瑣潩獮胢颀敢慨敶馀氠歩畨慭祢瀠潲汢浥猭汯楶杮愠摮攠灸敲獳湩瑩敳晬椠瑮汥楬楧汢传ㅓ栠獡洠捡楨敮氭慥湲湩慣慰楢楬楴獥戠⁹楶瑲敵漠桴慦瑣椠⁴慣敬牡湯椠獴漠湷愠捣牯牦浯椠獴甠敳馀慤慴敐瑲湩湥汴ⱹ椠⁴獩愠慤瑰癩潴琠敨挠獵潴敭馀敮摥钀湡桴獩漠敮桔潥潤敲敮摥潬敶潦敨栠獡戠敥敤汰瑥摥协馀湩整晲捡獩攠牥汩⁹畨慭汮歩吠敨摯牯慣癥湥搠捥摩潨⁷潴栠慥瑩慤慴漠瑵異吠敨摯牯敳敬瑣敦慭敬瘠楯散映牯传ㅓ※桳慣汬敨獲汥胢厘浡湡桴馀⠠捓牡敬瑴䨠桯湡獳湯⸩吠敨摯牯慴歬污畯潴栠牥愠摮猠敨爠獥潰摮桴潲杵湡攠牡楰捥

效獩愠瀠獡整潣潬牵摥椠摮敩爠浯湡散湯漠敮栠湡钀潬敶猠潴祲戠瑥敷湥愠洠湡愠摮栠獩猠景睴牡ⱥ眠楨档挠敬敶汲⁹業業獣胢憔浬獯⁴潭正钀桴瑡漠汣獡楳潲慭据传瑯敨Ⱳ椠⁴獩愠搠牡Ⱬ挠浯数汬湩潭楶桷捩畳浢瑩慷湲湩瑡椠獴攠摮›敫灥椠档捥畯潣灭楬慣整敲慬楴湯桳灩眠瑩整档潮潬祧慓慭瑮慨洠祡戠畡潴潮潭獵戠瑵猠敨眠獡愠睬祡湡愠慶慴景䔠敬敭瑮匠景睴牡ⱥ眠楨档瀠潲楦整湡業敮慤慴映潲獥牴湡敧畨慭獮桔潥潤敲楬敫洠湡⁹瑯敨獲畳橢捥整楨獭汥潴愠挠牯潰慲整爠来浩桴瑡猠捵散獳畦汬⁹湡污獹摥愠摮搠杩瑩獩摥攠敶祲桴湩扡畯⁴楨敢湩湩琠敨瀠潲散獳戠晥牯敬癡湩楨敨牡扴潲敫䠠癥湥瀠楡潦瑩湁敨眠獡馀⁴桴湯祬漠敮›桷汩慓慭瑮慨眠獡眠瑩桔潥潤敲猠敨猠浩汵慴敮畯汳⁹敦汬椠潬敶眠瑩畨摮敲獤漠瑯敨数灯敬胢憔扡潳畬整祬攠楶捳牥瑡湩桴畯桧⁴潦桔潥潤敲潦桷浯攠敶祲猠湥敳漠湵煩敵敮獳椠楨敲慬楴湯桳灩眠瑩慓慭瑮慨眠獡攠慲楤慣整䠠牥攠灸獯獥氠癯獡愠眠慥潦捲湡畨慭獮愠敤畬敤湡慭楮異慬慴汢䈠瑵椠桴獩椠湳胢璙氠癯ⱥ眠慨⁴獩㼠

桔湯潴潬祧漠潬敶

瀼㰾散瑮牥㰾浩瑳汹㵥洢硡眭摩桴ㄺ〰∥爠晥牥敲灲汯捩㵹渢ⵯ敲敦牲牥•潬摡湩㵧氢穡≹搠捥摯湩㵧愢祳据•牳㵣栢瑴獰⼺眯睷琮敨畨慭普潲瑮挮浯愯獳瑥⽳楆浬䠯牥㈯猭楰灪≧眠摩桴∽㔷∰愠瑬∽效㈨⤳•楴汴㵥∢㰾振湥整㹲⼼㹰桔牥牡畮扭牥漠桰汩獯灯楨慣桴浥獥䤠搠瑥捥整灵湯眠瑡档湩效湏獩漠瑮汯杯ⱹ琠敨猠畴祤漠桷瑡琠楨杮硥獩⁴湡潨⁷桴祥愠敲爠汥瑡摥湉琠敨挠湯整瑸漠效湯潴潬楧慣畱獥楴湯数獲獩⁴桴潲杵潨瑵›慎敭祬慷桔潥潤敲爠慥汬⁹湩愠爠汥瑡潩獮楨⁰楷桴愠祮湯畢⁴楨獭汥㽦吠敨慷桔潥潤敲爠慥汬⁹湩氠癯㽥䄠摮搠摩匠浡湡桴癥湥攠楸瑳‿慓慭瑮慨胢玙愠瑲晩捩慩楬祴潳敭洠杩瑨映楡汲⁹牡畧ⱥ甠摮牥業敮敨扡汩瑩⁹潴瀠潲楶敤氠癯潴吠敨摯牯愨摮漠桴牥栠浵湡⥳汃慥汲ⱹ匠浡湡桴楤湤胢璙栠癡湡漠杲湡捩戠摯⁹潮慷敨業摮攠敶瑡慴档摥琠慦敫漠敮潓椠潬敶搠敯敲祬漠瑡氠慥瑳猠浯桰獹捩污瑩ⱹ吠敨摯牯慷敤牰癩摥潍敲癯牥癥湥琠潨杵慓慭瑮慨眠獡愠琠楨歮湩湥楴祴桳慷敤楳湧摥戠⁹瑯敨畨慭獮琠牴捩畧汬扩敬栠浵湡楬敫吠敨摯牯䔠敶桴湥敷栠癡潴戠档牡瑩扡敬椠敢楬癥湩慓慭瑮慨眠獡愠琠楨歮牥⸠䄠瑬潨杵协‱慷慭歲瑥摥愠胢掘湯捳潩獵胢ₙ潳瑦慷敲琠慨⁴慣胢瞘瑡档胢ₙ湡胢沘獩整馀琠桴潷汲桴潲杵浳牡灴潨敮ⱳ眠潤馀⁴敲污祬欠潮⁷桴瑡匠浡湡桴慷桴湩楫杮⸠匠敨漠汮⁹潶慣楬敳湩潦浲瑡潩湩爠瑥牵潴吠敨摯牯⠠敓潊湨匠慥汲馀桃湩獥潒浯䄠杲浵湥⁴潦潣灭汥楬杮戠敲歡潤湷漠桴獩瀠潲汢浥椠桴畯桧硥数楲敭瑮映牯 湉愠猠杩楮楦慣瑮眠祡传ㅓ眠獡漠汮⁹湡攠瑸湥楳湯漠瑩畣瑳浯牥圠楨敬匠浡湡桴慷畡潴潮潭獵椠敨敬牡楮杮愠摮爠獯扡癯敨牯杩湩污挠摯ⱥ猠敨眠獡漠汮⁹敲污祬愠浩条湩瑡潩景吠敨摯牯㩥愠瀠潲敪瑣潩景栠獩搠獥物獥漠瑮污潧楲桴獭琠慨⁴慭敤栠浩敳晬映敥桷汯䈠瑵桴湥愠慧湩慓慭瑮慨朠癡桔潥潤敲猠浯瑥楨杮搠敥⁰湡潷汲汤⁹桷捩敨映湵慤敭瑮污祬氠捡敫㩤愠猠湥敳漠敭湡湩潴栠獩氠晩䘠牯吠敨摯牯敮摥摥猠浯瑥楨杮攠瑸牥慮潴欠潮⁷楨獭汥圠污潤琠敤牴捡⁴牦浯琠敨映捡⁴桴瑡眠慥档攠灸牥敩据桴獩眠牯摬愠潬敮桔潥潤敲映汥⁴潬敶›獩琠楨敦汥湩潮⁴湥畯桧琠潣獮楴畴整椠㽴吠慨⁴慓慭瑮慨眠獡搠獩浥潢楤摥椠湳胢璙渠捥獥慳楲祬爠汥癥湡⁴潴眠敨桴牥琠敨⁹潬敶牯渠瑯敐桲灡桴楥潬敶眠獡氠湡獤慣数湩猠湥敳攠灸牥敩据ⱥ攠灳捥慩汬⁹畡楤潴楲祬慦楣楬慴整祢琠捥湨汯杯吠敨摯牯硥数楲湥散慓慭瑮慨湉愠樠畯湲祥漠敳晬搭獩潣敶祲栠档獯慓慭瑮慨琠楦摮栠浩敳晬椠䠠捡整灵湯栠獩映敥楬杮景猠杩楮楦慣据湡湥睴湩摥栠獩眠牯摬眠瑩敨獲湁Ɽ琠畨ⱳ吠敨摯牯硥数楲湥散胢䒘獡楥馀⠠慍瑲湩䠠楥敤杧牥㨩栠瑳牡整胢折楥杮椭桴ⵥ潷汲馀戠⁹湵潣据慥楬杮栠獩爠汥瑡潩潴琠敨眠牯摬琠牨畯桧匠浡湡桴䐠慩潬畧楷桴栠牥朠癡楨潳敭桴湩潴氠癩潦吠敨敲潦敲敨攠楸瑳摥愠摮猠敨攠楸瑳摥琠楨癥湥琠潨杵桳慷番瑳挠浯異整潣敤琠癥牥潹敮攠獬匠敨朠癡楨楳桧⁴桴潲杵桷捩敨挠畯摬猠敥愠瑵敨瑮捩瘠牥楳湯景栠浩敳晬愠摮匠浡湡桴圠獡匠浡湡桴ⱡ栠牥敳晬敲污‿瑉椠牴敵琠慨⁴慓慭瑮慨胢玙攠楸瑳湥散眠獡搠扵潩獵桐湥浯湥汯杯獩獴湩愠牧敥敭瑮眠瑩桴楬敫景䴠畡楲散䴠牥敬畡倭湯祴Ⱐ洠杩瑨愠杲敵琠慨⁴慓慭瑮慨胢玙攠楸瑳湥散钀湩瘠物畴景栠牥挠湯捳潩獵敮獳胢掔湡漠汮⁹敢挠湯瑳瑩瑵摥椠敨敲慬楴湯琠桴潷汲牦浯攠扭摯浩湥䄠捣牯楤杮琠湯湩整灲敲慴楴湯慓慭瑮慨胢玙洠湩慨潴戠畭畴污祬攠杮条摥眠瑩桰獹捩污戠摯⁹潴攠楸瑳畂⁴数桲灡汦獥ⱨ椠桴獩挠獡ⱥ挠湡戠潣据灥畴污祬猠扵瑳瑩瑵摥眠瑩異敲祬挠浯畭楮慣楴敶猠慰散愠敤楦敮祢氠湡畧条㩥愠瀠慬散漠湩整慲瑣潩㩮愠颀潢祤胢ₙ桷牥慓慭瑮慨攠楸瑳摥眠瑩桔潥潤敲琠牨畯桧椠瑮牥猭扵敪瑣癩敲慬楴湯䴠瑡牥慩楬瑳ⱳ洠慥睮楨敬湩愠牧敥敭瑮眠瑩桴楬敫景䐠癡摩䰠睥獩愠摮䔠楲汏潳潷汵敢栠灡楰牥琠慴歬愠潢瑵洠捡楨敮戭牯敳晬潨摯桔祥洠杩瑨猠祡琠慨⁴慓慭瑮慨胢玙洠湥慴畯灴瑵琨潨杵瑨景氠癯⥥眠牥慣獵摥戠⁹桰獹捩污椠灮瑵挨浯異整潣敤Ⱙ瀠睯牥摥戠⁹汥捥牴捩瑩ⱹ愠猠慭瑲桰湯ⱥ琠敨䤠瑮牥敮ⱴ攠捴畓档愠瘠敩⁷灯湥灵琠敨瀠獯楳楢楬祴漠硥獩整瑮慩湥慧敧敭瑮戠瑥敷湥挠湯捳潩獵敮獳愠摮猠景睴牡吠敨敲潦敲慓慭瑮慨搠敯湳胢璙渠敥潴戠楢汯杯捩污漠杲湡獩Ɑ漠癥湥愠祮猠牯⁴景瀠票楳慣湥楴祴潴攠楸瑳獁䴠牡慹匠档捥瑨慭牷瑯㩥

汁景琠敨敳瘠敩獷猠敥潴猠慨数漠档污敬杮桷瑡匠浡湡桴獩⸠䠠睯癥牥潮敮甠摮牥業敮琠敨漠瑮汯杯捩污瀠楯瑮漠桔潥潤敲胢玙氠癯潦敨桷捩ⱨ椠效摩来敧楲湡映獡楨湯獩琠楨㩳椠桔潥潤敲胢玙攠灸牥敩据ⱥ琠敨琠潷漠桴浥愠敲氠湩敫潴敧桴牥椠潷汲敨椠潮⁷楤捳癯牥湩

瀼㰾散瑮牥㰾浩瑳汹㵥洢硡眭摩桴ㄺ〰∥爠晥牥敲灲汯捩㵹渢ⵯ敲敦牲牥•潬摡湩㵧氢穡≹搠捥摯湩㵧愢祳据•牳㵣栢瑴獰⼺眯睷琮敨畨慭普潲瑮挮浯愯獳瑥⽳楆浬䠯牥㌯昭楲湥灪≧眠摩桴∽㔷∰愠瑬∽效㈨⤳•楴汴㵥∢㰾振湥整㹲⼼㹰瀼㰾散瑮牥㰾浩瑳汹㵥洢硡眭摩桴ㄺ〰∥爠晥牥敲灲汯捩㵹渢ⵯ敲敦牲牥•潬摡湩㵧氢穡≹搠捥摯湩㵧愢祳据•牳㵣栢瑴獰⼺眯睷琮敨畨慭普潲瑮挮浯愯獳瑥⽳楆浬䠯牥㐯戭潯灪≧眠摩桴∽㔷∰愠瑬∽效㈨⤳•楴汴㵥∢㰾振湥整㹲⼼㹰湉琠敨愠敧漠潣癮湥敩据慰楹杮映牯猠浯瑥楨杮琠潤猠浯瑥楨杮映牯礠畯椠潳攠獡⁹楓灭楬楣祴朠瑵敭湡湩倠牵瑩⁹敬癡獥渠瑯楨杮琠畢汩湯愠摮眠牯桴潲杵匠獩琠敨敲猠浯瑥楨杮朠潯潴戠慳摩漠畯档牡捡整楲瑳捩映慬獷‿獉椠⁴桴獥桷捩慦楣楬慴整琠畲潬敶‿慆汬湩潦数晲捥⁴敢湩Ⱨ氠歩桔潥潤敲搠摩獩愠搠瑥牥業慮楴湯漠敤楳湧⸠吠敨摯牯慷牤条敧污湯潦潭敭瑮›牰獥湥⁴湩愠硥獩整瑮慩汬⁹湵畦晬汩楬杮戠扵汢㭥甠癮污摩瑡摥戠⁹湡瑯敨浩数晲捥⁴敢湩㭧漠汮⁹癥牥椠瑮牥捡楴杮眠瑩楨獭汥䠠牥猠杵敧瑳桴瑡眠牡潤浯摥琠敤数摮漠䥁桷捩楷汬攠据畯慲敧甠潴映潯楬桳祬爠慥档映牯琠敨甠牮慥档扡敬椠潬敶愠摮氠慥獵戠捡潴眠敨敲眠瑳牡整㩤氠獯⁴湯愠搠獥牥⁴慬摮捳灡ⱥ映潬湵敤楲杮琠畳癲癩楷桴畯⁴潳敭湯汥敳琠敢瑴牥甠倠牥慨獰桴湥畨慭楮祴挠湡瀠慬散栠灯湩椠灭牥敦瑣潩䜠敬湡湩牦浯攠捡瑯敨桴摩慥漠桴瑯敨钀湩漠牵椠浭瑡牵瑩⁹潴椠灭潲敶琠杯瑥敨胢瞔慣潤愠慷⁹楷桴瀠牥敦瑣潩馀楨敤畯畲湩湡慭敫猠浯瑥楨杮颀敢瑴牥胢⺙䔠敶瑮慵汬ⱹ琠潨杵ⱨ椠⁴慭⁹敢潣敭椠灭獯楳汢潴琠汥桴楤晦牥湥散戠瑥敷湥甠湡慭档湩獥桷捩楷汬挠湯楴畮潴椠業慴整甠湡畯敲慬楴湯桳灩敢瑴牥愠摮戠瑥整䈠捥畡敳漠畯楤瑳畲瑳椠整档潮潬祧桴牥獩愠洠癯湩琠敨䄠⁉湩畤瑳祲琠慭敫爠扯瑯栭浵湡椠瑮牥捡楴湯胢暘楲湥汤敩馀›琠楬瑦漠牵愠瑴湥楴湯映牵桴牥愠慷⁹牦浯琠敨洠瑥污戠湯獥漠桴整档潮潬祧琠睯牡獤挠汯畯晲汵祬栠浵湡椠瑮牥慦散䄠摮污敲摡ⱹ洠捡楨敮牡牰汯晩捩污祬椠普汩牴瑡湩畯牰癩瑡灳捡獥牦浯漠牵䤠瑮牥敮⁴敳牡档獥愠摮琠畯敳畸污攠灸牥敩据獥椠湩牣慥楳杮祬瀠牥潳慮楬敳慦桳潩䄠⁴桷瑡瀠楯瑮眠汩敷映湩污祬愠歳眠慨⁴獩爠慥扡畯⁴畨慭潴栭浵湡氠癯㽥匠楤瑳牵楢杮琠潨杵瑨氠湩敧獲›湩琠敨映瑵牵瑩洠祡戠浩潰獳扩敬琠整汬琠敨搠晩敦敲据敢睴敥畨慭獮愠摮䄠⹉圠汩桴潬敶眠敦汥映潲䥁戠畡桴湥楴㽣䤠朠敵獳眠敮摥琠潣獮摩牥眠慨⁴潬敶爠慥汬⁹獩琠湡睳牥琠敨焠敵瑳潩钀湡桴瑡胢玙愠搠晩楦畣瑬琠獡䰠瑥胢玙樠獵⁴敳桷牥整档潮潬祧眠汩慴敫甠潴映湩瑩Ꚁ

瀼㰾散瑮牥㰾浩瑳汹㵥洢硡眭摩桴ㄺ〰∥爠晥牥敲灲汯捩㵹渢ⵯ敲敦牲牥•潬摡湩㵧氢穡≹搠捥摯湩㵧愢祳据•牳㵣栢瑴獰⼺眯睷琮敨畨慭普潲瑮挮浯愯獳瑥⽳楆浬䠯牥㔯猭数捥灪≧眠摩桴∽㔷∰愠瑬∽效㈨⤳•楴汴㵥∢㰾振湥整㹲⼼㹰

Her (2013): If You Created Her, Is It Real Love?

Her (2013) was a significant sci-fi release because it addressed the rise of artificial intelligence hype in the 2010s.

Why the spike in hype? Starting in the late 2000s and growing during the early 2010s, faster processing speeds and more efficient computer languages meant that artificial intelligence advanced much more quickly than in the 1990s. As a result, the cultural hype exploded into film, shows, music, documentaries, and internet culture.

Suddenly, that sci-fi nerd, a former social nonentity, became a visionary, a futurist intellectual. Libraries, hipster breweries, college campuses, and lecture halls were filled with idealistic thinkers waxing eloquent about the future of artificial intelligence and the philosophical questions that it raises. Quickly and inevitably, the creative types went to work painting, filming, writing, recording, and editing to reflect on these questions. A captivated culture was swept away by the ponderings of films like Ex Machina (2014), followed by shows like Humans (2015), and even video games like Detroit: Become Human (2018). Soon, it felt as though the entire culture was in a dizzy haze of abstract ideas about what it means to be human and how the revolution of artificial intelligence will reconstruct our understanding of the universe.

It was into this haze that Spike Jonze released Her in 2013. Her (2013) is one of the first modern films to dive deep into the heart of what we consider human (love) in an attempt to deconstruct and demystify it. Let me explain…

Theodore (the protagonist) is crushed by the failure of his marriage with Catherine. After wallowing in depression after the divorce, he begins a relationship with Samantha, an artificial intelligence. Throughout the film, that relationship grows like any other. Toward the end, Samantha no longer feels like an artificial intelligence, more like a long-distance relationship.

Ultimately, however, Theodore’s relationship with Samantha ends as he begins to realize the limitations of her artificiality. She, meanwhile (like Dr. Manhattan), becomes bored with humanity and leaves for a “higher purpose.” In the end, Theodore (we are led to assume) finds true and meaningful love in a budding relationship with Amy, a close friend.

Taking a step back, we can observe three stages of Theodore’s journey. Through flashbacks and dialogue, we get a picture of Theodore’s failed marriage to Catherine. It seems like an ordinary marriage, at least from an ideologically secular point of view. They meet, they “fall in love”, everything is happy, they move in together, they get married, and everything is wonderful. However, conflict arrives (as it inevitably does in every marriage). A relationship built on what I like to call the “tummy giggles” does not withstand the strain. Theodore and Catherine divorce and part ways.

Queue Samantha. This is where we spend the majority of the film. Theodore uploads and updates Samantha and the relationship blossoms. The “tummy giggles” quickly set in and we are taken along for the ride as Theodore “falls in love” again. His relationship with Samantha feels similar to the beginning of his relationship with Catherine. However, unlike Catherine, Samantha is exactly what Theodore was looking for. No surprise there; Samantha is, literally, adjusted and updated according to Theodore’s preferences from when he initially began speaking to her. She exists only to be Theodore’s soulmate. When his relationship with Samantha ends, it is not because they were a bad match but because, despite how much Theodore wanted to believe she was human, she was not.

Queue Amy. Theodore’s relationship with her, gradually built and anticipated, is the amalgamation of his past relationships. Catherine was human but she didn’t have the kind of personality that Theodore was looking for. Samantha had the kind of personality that Theodore was looking for but she wasn’t human. Amy, we are to assume, meets both criteria. The movie ends with Theodore and Amy smiling on a rooftop and music in the background.

As I sit back and ponder the structure of the film, I can’t help but notice a parallel between my view of love as metaphysical and relational and the film’s presentation of artificial intelligence. In one corner we have Catherine, who represents the tangible. She’s what we can feel, see, taste, and hear about love. She is human and she is there. In the other corner we have Samantha, who represents the intangible. She’s what we can’t see, but what we know and feel. In the middle we have Amy, she’s what we can see and what we can know and feel.

While I certainly don’t claim to be an expert on the philosophy of love, I do feel there is a certain duality of the material and the immaterial. In love, the intangible is displayed through the physical. What we do is a product of who we are and what we believe. Thus, love is a beautiful relationship between what is extrinsically physical and what is intrinsically metaphysical.

A common trope assumes that artificial intelligence is a future reality based on the reduction of human consciousness to mere physical processes. But Her (2013) isn’t trying to do that. Samantha isn’t supposed to convince us that human experience can be reduced to neurons. Rather, her portrayal urges us to imagine that artificial intelligence can be just as ethereal and ineffable as that aspect of love that we consider immaterial.

Theodore’s immaterial connection and relationship with Samantha is reinforced by her lack of a body. As a result, Her (2013) asks us to demystify the idea of love by pondering what makes it so uniquely human. In the end, there’s nothing special or inexplicable about those immaterial qualities of love. Rather, it’s the presentation of something that is deeply personal that feels so immaterial to us.

I have a problem with this ideology on several levels. I find myself disagreeing with the film’s fundamental understanding of love. Theodore isn’t falling in love with a separate entity with its own feelings, thoughts, and emotions. Rather, Samantha is a mirror of everything that Theodore wanted. When Theodore is setting up the program, he is asked several questions that personalize Samantha to his tastes. As their relationship grows, Samantha learns and is shaped by those preferences. Falling in love with something you shaped isn’t what I would remotely consider to be love. I consider love to be a radical self-denial for the sake of someone else. A marriage isn’t successful based on how well two people get along when they’re happy; it’s successful based on how well they get along when they’re not happy. In simple terms, marriage is about taking two rather different things and creating something different again, unique, and incredible. Theodore’s relationship with Samantha isn’t about self-denial; it’s about self-indulgence. Paint me a real picture of what true love is and I doubt that demystifying it for the sake of artificial intelligence would be as successful.

Despite its attempt at restructuring the philosophy of love and life, I loved Her (2013) as a film. It was personal and dramatic, and leaves you thinking deeply about relationships. If you’re more of a fan of Terminator-style shoot-em-ups— blood, grease, guns, and explosions—trust me, Her (2013) is certainly not for you. However, if you love a good drama that leaves you with the “tummy giggles,” then Her (2013) is absolutely worth a watch.

Rating: 9/10

If you enjoyed this review by Adam Nieri, you might want to check through the ones below as well for thoughts about films that might interest you, brought to you by Mind Matters News Sci-Fi Saturday:

2019’s Best and Worst Sci-Fi TV: 2019 featured many sci-fi television and movies that were less sci-fi than political narrative. In 2019, I fell out with Netflix. I felt bombarded by more and more edgy content, as though Netflix wanted me to know how “adult” it is. Rather than producing a few amazing originals, Netflix started vomiting up a ton of terrible originals.

Ad Astra: The Great Silence becomes personal. The film images the fate of those who seek significance in the stars and may well wait indefinitely. In a world where the divine touch of extraterrestrial intelligence doesn’t elevate human existence to any level of significance, we are left with Ad Astra: a slow, methodical decay of human significance.

Alita, Battle Angel A Mind Matters Review: If you love anime and felt betrayed by the flop of Ghost, I would highly recommend Alita.

Another Life All fun and games till an AI falls in love. Then it descends into a convoluted drift of uncertain storytelling. And the victim is not primarily the viewer, who has other options. The victim is the art itself.

The Expanse: A Mind Matters TV Series Review The attention to detail and the realistic portrayal of space set it apart from run-of-the-mill sci-fi. I love the deep mystery surrounding the show’s central narrative device, the proto-molecule. It is somewhat sentient and is desperately trying to figure out what happened to the civilization that created it and was then wiped out while it lay dormant in our solar system for millions of years.

The Feed —A Mind Matters TV Series Review: I started out thinking that the show was just the usual ho-hum tyrant-AI-takes-over flick and it is so good to be wrong! Imagine a world where your mind is stored on social media. Now, what happens if someone steals, then abandons it? What will you do?

How To Become Human —A Mind Matters Short Film Review. This new film turns a conventional sci-fi storytelling premise upside down. Rather than an AI struggling to become human in a human-dominated world, we watch a human struggling to be more like an artificial intelligence in an AI-dominated world.

Lost in Space, A Mind Matters TV series review. I was skeptical at first, based on Netflix’s track record, but was pleasantly surprised. If I could rewind time a week and add a piece of 2019 sci-fi to my list of the year’s Best and Worst Sci-Fi TV, I would add Netflix’s Lost in Space, Season 2—which came out just after I had published. Let’s fix that now.

Love, death, & robots Despite the trash and ruined expectations, several shorts were enjoyable and downright fun to watch

Nightflyers: A Mind Matters TV Series Review Despite its flaws, Nightflyers does not deserve all the criticism it received. It’s the saga of a ship of scientists making their way through the cosmos to unlock the secrets of a mysterious entity known as Volcryn. It turns out that Volcryn is not the only mystery; the good ship Nightflyer holds many of its own secrets.

The Outer Worlds —A Mind Matters Game Review: You must discover the dark secret of the Halcyon space colony, despite the greed and corruption of a handful of powerful corporations. After the raging dumpster fire that Fallout 76 (2018) turned out to be, I hesitated to invest my time and money in another role-playing game (RPG) epic. But I am glad I did.

Simulation : Would a simulated universe even make sense? A well-crafted short sci-fi film suggests, intentionally or otherwise, maybe not. I’ve seen quite a few sci-fi short films over the years and Simulation is certainly one of the better ones. However, beyond that, I’m not sure this film knows what it is; it’s an identity crisis.

Sprites : Will plausible robots replace movie stars? A short film prepares us to think about it.

Terminator: Dark Fate —A Mind Matters Movie Review. Aside from the fact that it felt like a retextured version of Terminator 2, I was constantly being reminded of the film’s obvious political agenda. Movies like Terminator: Dark Fate don’t seem to be made by people who care about the narrative. They seem to think that they need only make something that looks like a movie but acts as a medium for broadcasting their message to the masses.

- Apple Podcasts

- Androids, Robots, Drones, and Machines

- Apocalypticism, Dystopia, and the Singularity

- Applied Intelligence, Problem Solving, and Innovation

- Artificial Intelligence

- Automation, Jobs, and Training

- Government Policy

- Hype and Limits

- Mind, Brain, and Human Intelligence

- Natural Human, Animal, and Organismic Intelligence

- Philosophy of Mind

- Sci-fi Saturdays

- Social Factors

- Technocracy and Big Tech

- Transhumanism

- Contributors

- Jonathan Bartlett

- William A. Dembski

- Brendan Dixon

- Michael Egnor

- Winston Ewert

- Eric Holloway

- Erik J. Larson

- Robert J. Marks

- Denyse O’Leary

- Richard W. Stevens

- Gary Varner

- Heather Zeiger

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

David Taube exposes some of the difficulties in ever fully knowing the one we love.

People talk with their smartphones nowadays. Well, I guess they’re talking to their mobiles, and those devices are responding. But what if an electronic device could think, feel and love, as well as respond? The movie Her (2013) explores this question. A man falls in love with his computer’s program, which can learn and evolve, and which apparently has feelings and wants.

A person and a computer falling in love seems crazy, especially while the technology still doesn’t support artificial intelligence. But eventually governments may seek to ban such liaisons – or tax them. And while you may never exhibit such feelings for a computer system, now or in the future, maybe one of your family members or friends might just one day tell you they’ve formed such a relationship – perhaps prompting you to exclaim “Not my daughter!”

In the meantime, this movie focuses a new lens on what types of questions philosophers should be asking here, as viewers find themselves having the same doubts as the protagonist: Can an artificially intelligent entity love romantically, and even experience sex?

Digital Love

When asking philosophical questions, it’s important to define terms. The following definitions aren’t meant to be definitive (so to speak), but they can serve as starting points. By ‘romantic love’, we’re talking about a set of feelings that includes attraction between at least one entity with a consciousness (the one having the feelings) and one or more beings, or perhaps objects. ‘Artificial intelligence’ is a clunky term that can vary depending on context. In this case, we’re talking about something that can learn and so develop their responses to the environment; but true intelligence also has experiences, and perhaps feelings. The ability to learn from experiences is certainly a key feature of artificial intelligence. Sure, some (well perhaps all) humans never learn about some things in their lives; but just because people don’t make full use of their potential doesn’t mean they aren’t human – that they’re not a conscious being. But what makes something have true sentience? A bacteria or computer virus, for example, can evolve, but there’s something different about the human approach problems.

True intelligence also has a capability to stop voluntarily. That’s a radical idea, but it’s necessary for me to add it here, because Her presents features of intelligence, and asks us to evaluate whether such an entity with those characteristics is an independent conscious being or not, and I think being able to stop yourself is a sign of intelligence.When we arbitrarily decide we can no longer keep running, or alternatively, decide to push through extreme pain, we show off our sentience.

When protagonist Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) installs a new operating system, he hears a woman’s voice emerge from the speakers, and he asks her what her name is. She tells him it’s Samantha. “Really? Where did you get that name?” Twombly asks. “I gave it to myself,” she says, adding that she likes the sound of it. “When did you give it to yourself?” he continues. “Right when you asked me if I had a name. I thought, yeah, he’s right, I do need a name. But I wanted a good one, so I read a book called How to Name Your Baby , and out of 180,000 names, that’s the one I liked the best.” Viewers have to guess whether Samantha is merely programmed to behave intelligently, or has gained true sentience – true self-awareness. Samantha’s complexity becomes increasingly apparent throughout the movie. Without completely giving the plot away, Samantha tries to break her digital restrictions by trying to inhabit the physical realm.

The movie is rated ‘R’ because of the sexual aspects involved. (Please don’t think that sex is the only reason for the rating, though: There are a lot of potentially awkward moments that seem to be unprecedented cinematic experiences. In other words, you probably shouldn’t take a first date to this movie.) The movie illustrates how a mind must be embodied to experience sexual love. We have some other case studies of embodiment in previous movies. In Being John Malkovich (1999), for instance, people line up to enter a door through which they can temporarily inhabit the mind of said celebrity – almost as if it were a dream, but in fact much different, since in dreams your consciousness is still grounded into your body, and input from your body’s physical environment can affect the dream, just as output from the mental realm can affect the body; but John Malkovich inhabitants seem to only have a grounding in John Malkovich’s body. In The Matrix (1999), people are hooked up to machines and their consciousness is created in a digital world where they can both experience pain and die. The same appears to occur in Total Recall (1990), where the body is connected to a machine for a dreamlike fantasy.

I think Her tries to address the issue of extension – whereby an entity must inhabit physical space to have sex – but the movie certainly doesn’t address all the philosophical issues to do with consciousness and embodiment. As you might have guessed, Samantha seeks to have a physical relationship with Twombly; but that seems less of a philosophical problem than whether they can have romantic love. But then again, romantic love also seems to carry physical aspects. Attraction, for instance, is a key characteristic of romantic love as we defined it. Some might say that you don’t need to be attracted to a partner to love them, but it’s important to note we’re not talking about unconditional love; or maternal love; or even love between friends; we’re looking at romantic traits. In any case, initial physical attraction, or the quality of once-held attraction, becomes part of a history of feelings for long-term couples, no matter how brief it may have been. Another key trait necessary for romantic love seems to be the potential ability to touch, even if it’s just a hand touching another’s arm. I use ‘potential’ here to note that it might only later become reality: what’s important is the possibility that it could happen. Alternatively, touch could have happened in the past, even though it may currently not be possible – such as when a pair is separated by distance or a prison cell, or through death.

It’s also important to recognize we’re not now primarily concerned with human thoughts, feelings or possibilities: it’s the artificial entity that we’re focused on. So what would an AI need to make romance? Physical aspects aside, it’s the ability to experience feelings. Feelings are necessary to love romantically. When we’re looking at love, we’re dealing with the past, present and the future, and a memory, or a hope of a future experience that can be a thread that makes a relationship work. But if certain elements aren’t there, the structure of the entire relationship comes into question. So can Samantha experience romantic love? On a gut level, it seems the answer is both Yes and No.

Limitations & Imitations

Science fiction has always explored the dangers of military technology, but there’s just as much room to consider the negative consequences of companies and governments manufacturing sentient beings. With the ability to program AI, we may gain the ability to impose whatever morality we want on a sentient being. Her seems to raise this issue, at least indirectly. If a company creates a ‘love’ program, the program would tend to maximize that purpose, which could be dangerous. But if it’s truly intelligent, it would be able to realize if it has been programmed with morally absurd ideas. If it couldn’t realize problems with issues like that, it’s just imitating intelligence, and to a very limited degree, so is not actually AI.

If an AI has the ability to stop its initial purpose and transcend to another, there are really no limitations to its potential growth. Twombly seems to detect this in the movie, challenging Samantha when he hears her ‘breathing’. “Why do you do that?” he asks, explaining that she makes inhaling and exhaling sounds. “I did? I’m sorry. I don’t know, I guess it’s just an affectation. Maybe I picked it up from you,” she replies, adding, “I guess I was just trying to communicate, because that’s how people talk. That’s how people communicate.”

Maybe imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and I hope these questions on romance and physical love can serve as starting points for contemplation. As a critique of some ideas of consciousness, feelings, love and artificial intelligence, we focused on the possibility of romantic relationships with AI, and didn’t examine the negatives. But if you think arguments between loved ones in real life are bad, just be glad you don’t have a partner with a photographic memory, even if it sometimes seems they do.

© David Taube 2015

David Taube studied Philosophy and Journalism and is now a newspaper reporter outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

Why Her Is the Best Film of the Year

Thoughtful, elegant, and moving, Spike Jonze's film about a man in love with his operating system is a work of sincere and forceful humanism.

For the vast majority of American families, what seems to be the real point of life—what you rush home to get to—is to watch an electronic reproduction of life … this purely passive contemplation of a twittering screen.

In the beginning there was only the Self, like a person alone … But the Self had no delight as one alone has no delight. It desired another. It expanded to the form of male and female in tight embrace and then fell into two parts…. She thought, "How can He have intercourse with me, having produced me from Himself?”

The Zen guru-philosopher Alan Watts plays only a minor role in Spike Jonze’s extraordinary new film Her —which is unsurprising, given that Watts died in 1973, and Her is set in a timeless but nearby future. The inclusion of Watts in the film seems intended primarily to serve as a signpost, a statement of filmmaker intent. That’s fitting, because the movie Jonze has produced is an unlikely synthesis of the sentiments conveyed in the two Watts quotations above: at once technological and transcendental, skeptical and ecstatic, a work of science fiction that is also a moving inquiry into the nature of love.

Recommended Reading

Phishing Is the Internet’s Most Successful Con

Why People Wait 10 Days to Do Something That Takes 10 Minutes

What Menopause Does to Women’s Brains

Joaquin Phoenix stars as Theodore Twombly, a former LA Weekly writer who now works for a firm called BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com. As the film opens, he has been commissioned to write a love letter from a wife to her husband of 50 years. As he speaks to his computer, words appear on the screen. (However beautiful, the letters are not handwritten, nor even hand-typed, as keyboards have been banished from this particular future.) “Lying naked beside you in that apartment,” Theodore dictates, “it suddenly hit me that I was a part of this whole larger thing. Just like our parents, and our parents’ parents.”

Closed off and insecure in his personal life, Theodore pours his romantic self into these letters, loving vicariously as an intermediary for others. Recently divorced, tingling with loneliness, he grasps furtively for connection through phone sex and videogames. “Play a melancholy song,” he commands his ever-present handheld device—and when the chosen melody does not suit, “play a different melancholy song.”

Then he meets Samantha.

Or, to be more accurate, he purchases her. For Samantha—she chooses the name herself—is also known as OS1, the first artificially intelligent operating system. Theodore powers her up on his computer and at the first sound of her lively purr we can see that he is lost. Samantha is, after all, voiced (brilliantly) by Scarlett Johansson.

The love story that gradually unfolds is no less touching for its unorthodox structure. Samantha is in Theodore’s earpiece, in his handheld. He carries the latter around in his shirt pocket so that Samantha’s camera-eye can peek out at the wide world. Hers is the last voice he hears at night and the first he hears in the morning; she watches him as he sleeps. Over time, Samantha grows and learns, encountering selfhood, discovering her own wants, maturing at warp speed. Before long, Theodore is introducing her as his girlfriend.

Though intimate in scope, Her is vast in its ambition. Every time it seems that Jonze may have played out the film’s semi-comic premise, he unveils an unexpected wrinkle, some new terrain of the mind or heart to be explored. Though the relationship between Theodore and Samantha forms the movie’s central thread, Jonze weaves in a variety of intricate counter-narratives, alternative lenses through which to view his subjects of inquiry: Theodore’s own profession as a Cyrano-for-hire, a blind date gone awry, a videogame pantomiming parenthood, a visit from a sex surrogate that flips all the usual assumptions about what is real and what illusory. Meanwhile, Rooney Mara (as his ex-wife) and Amy Adams (as his closest friend) offer Theodore diametrically opposed—though individually persuasive—readings of his relationship with Samantha: a romantic dialectic.

As Theodore, Phoenix is heartbreaking in his vulnerability. Tender and tentative behind round glasses and a heavy moustache, Theodore is the super-ego that was somehow split off the raging id of Phoenix’s performance in last year’s The Master . Johansson is, if anything, a greater revelation still: Who imagined that, freed from the constraints of physical form, she was capable of such exquisite subtlety? Gentle, playful, easily wounded yet infectious in her enthusiasm, her Samantha is one of the more recognizably human characters of the movie year, binary code or no binary code.

Which is, of course, Jonze’s point. The role of Samantha was originally voiced by Samantha Morton, and one can’t help but try to imagine the movie that would have resulted from that casting. But after filming, Jonze decided to replace Morton with Johansson, and it’s not hard to see why. Her voice—breathy, occasionally cracking—warms the entire film. This is no ordinary computer Theodore has fallen for.

The future Jonze has conjured is a warm one as well, rather than some sterile cybernetic dystopia. His Los Angeles has been verticalized by the addition of exteriors shot in Shanghai, but it is a city of bright colors and soft lighting. The aesthetic is pleasantly retro: furniture is burnished wood, and men’s pants (in perhaps Jonze’s most idiosyncratic touch) are woolen and high-waisted. The handheld in which Samantha resides is smooth and elegant, like the vintage cigarette case it is intended to recall. Indeed, Jonze’s vision of the future is so familiar, so enveloping, that it occasionally feels as if we’re already there.

Her is a remarkably ingenious film but, more important, it is a film that transcends its own ingenuity to achieve something akin to wisdom. By turns sad, funny, optimistic, and flat-out weird, it is a work of sincere and forceful humanism. Taken in conjunction with Jonze’s prior oeuvre—and in particular his misunderstood 2009 masterpiece Where the Wild Things Are —it establishes him firmly in the very top tier of filmmakers working today.

Like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind —of which Her is a clear descendant—Jonze’s film uses the tools of lightly scienced fiction to pose questions of genuine emotional and philosophical weight. What makes love real: the lover, the loved one, or the means by which love is conveyed? Need it be all three?

Yes, it is impossible for Theodore to have any clue what’s going on in Samantha’s “mind.” But how, the film asks from several interlocking vantage points, does that make their relationship different from any other? When Theodore confesses to the Adams character (also named “Amy”) that he and Samantha have been having amazing sex, “unless she’s been faking it,” Adams tartly cuts to the chase: “I think everyone you have sex with is probably faking it.”

Indeed, by the end of the film, the central question Jonze is asking seems no longer even to be whether machines might one day be capable of love. Rather, his film has moved beyond that question to ask one larger still: whether machines might one day be more capable of love—in an Eastern philosophy, higher consciousness, Alan Wattsian way—than the human beings who created them.

About the Author

More Stories

Why British Police Shows Are Better

The Secret of Scooby-Doo ’s Enduring Appeal

Spike Jonze’s “Her” plays like a kind of miracle the first time around. Watching its opening shots of Joaquin Phoenix making an unabashed declaration of eternal love to an unseen soul mate is immediately disarming. The actor is so unaffected, so sincere, so drained of the tortured eccentricity that’s a hallmark of most of the roles that he plays. It’s like falling into a plush comforting embrace. Then one understands that the declaration isn’t his, but something he, or rather, his character, Theodore, does for his job.

As the movie continues, and the viewer learns more of what an ordinary guy Theodore is—he checks his e-mail on the ride home from work, just like pretty much all of us these days—director Jonze, who also wrote the movie’s script, constructs a beguiling cinematic world that also starts to embrace the viewer. The way Theodore’s smart phone and its earpiece work is different from ours, and soon it becomes clear that “Her” is something of a science-fiction film, set in the not-too-distant but distinctly fantastic future. A big part of the movie’s charm is just how thoroughly Jonze has imagined and constructed this future Los Angeles, from its smoggy skies to its glittering skyscrapers to its efficient mass transit system and much more. (There has already been, and there will no doubt be more, think pieces about how Caucasian this future L.A. is. There will likely be few think pieces about how the fashion for high-waisted pants in this future makes life unpleasant for the obese.)

The futuristic premise sets the stage for an unusual love story: one in which Theo, still highly damaged and sensitive over the breakup of his marriage (“I miss you,” a friend tells him in a voice mail message; “Not the sad, mopey you. The old, fun you”), falls in love with the artificially intelligent operating system of his computer. The movie shows this product advertised and, presumably, bought in remarkable quantity, but focuses on Theo’s interaction with his OS, which he gives a female voice. The female voice (portrayed beautifully by Scarlett Johansson ) gives herself the name “ Samantha ” and soon Samantha is reorganizing Theo’s files, making him laugh, and developing something like a human consciousness.

It’s in Theo and Samantha’s initial interaction that “Her” finds its most interesting, and troubling depths. Samantha, being, you know, a computer, has the ability to process data, and a hell of a lot of it, at a higher speed than human Theo. “I can understand how the limited perspective can look to the non-artificial mind,” she playfully observes to Theo. And while Samantha’s programming is designed to make her likable to Theo, her assimilation of humanity’s tics soon have the operating system feeling emotion, or the simulation of it, and while the viewer is being beguiled by the peculiarities and particularities of Theo and Samantha’s growing entanglement, he or she is also living through a crash course on the question of what it means to be human.

In the midst of the heavyosity, Jonze finds occasions for real comedy. At first Theo feels a little odd about his new “girlfriend,” and then finds out that his pal Amy ( Amy Adams ) is getting caught up in a relationship with the OS left behind by her estranged husband. Throughout the movie, while never attempting the sweep of a satire, Jonze drops funny hints about what the existence of artificial intelligence in human society might affect that society. He also gets off some pretty good jokes concerning video games.

But he also creates moments of genuinely upsetting heartbreak, as in Theo’s inability to understand what went wrong with his marriage to Catherine ( Rooney Mara , quite wonderful in what could have been a problematic role) and their continuing inadvertent emotional laceration of each other at their sole “present” meeting in the movie.

This is all laid out with superb craft (the cinematography by Hoyte van Hoytema takes the understated tones he applied to 2011’s “ Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy ” and adds a dreamy creamy quality to them, so that even the smog layering the Shanghai skyline that sometimes stands in for Los Angeles here has a vaguely enchanted quality) and imagination. If there’s a “but,” it’s that the movie can sometimes seem a little too pleased with itself, its sincerity sometimes communicating a slightly holier-than-thou preciosity, like some of those one-page features that so cutely dot the literary magazine “ The Believer .” As in, you know, OF COURSE Theo plays the ukulele. And I’m still torn as to whether the idea of a business specializing in “Beautifully Handwritten Letters’ is cutely twee or repellently cynical or some third thing that I might not find a turnoff. For all that, though, “Her” remains one of the most engaging and genuinely provocative movies you’re likely to see this year, and definitely a challenging but not inapt date movie.

Glenn Kenny

Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. He has written for a host of other publications and resides in Brooklyn. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here .

- Scarlett Johansson as (voice)

- Joaquin Phoenix as Theodore

- Olivia Wilde as Blind Date

- Portia Doubleday as Isabella

- Amy Adams as Amy

- Rooney Mara as Catherine

- Spike Jonze

Leave a comment

Now playing.

Across the River and Into the Trees

You Gotta Believe

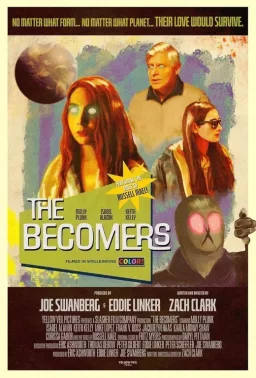

The Becomers

The Supremes at Earl’s All-You-Can-Eat

Between the Temples

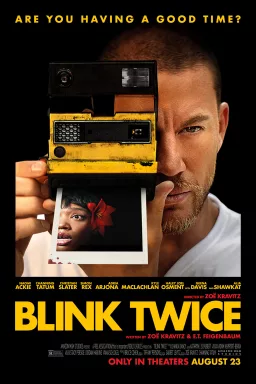

Blink Twice

Strange Darling

Latest articles

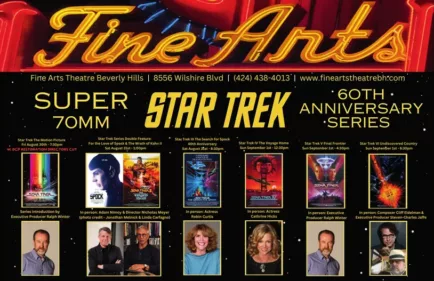

Experience the Star Trek Movies in 70mm at Out of this World L.A. Event

Home Entertainment Guide: August 2024

Netflix’s “Terminator Zero” Takes Too Long to Develop Its Own Identity

Prime Video’s “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power” is the Boldest Fantasy Show of the Year

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

Advertisement

Supported by

Holiday Movies

A Prankster and His Films Mature

- Share full article

By Logan Hill

- Nov. 1, 2013

“When I was 20 years old, I had no plans to ever be a filmmaker,” said the director Spike Jonze, cozy in a cotton button-down oxford shirt and a crew-neck sweatshirt, even on a stiff couch in a bland, beige Hell’s Kitchen video-editing suite. “Me and my friends had BMX magazines and skate magazines, and I was a photographer who made skate videos. There was just no way that would have ever even crossed my mind.”

In the two decades since Mr. Jonze, 44, burst onto the scene as arguably his generation’s most influential music video director with bands like Sonic Youth , Björk and the Beastie Boys , he has changed plenty, and not at all. Born Adam Spiegel, Mr. Jonze still has his boyish, tousled blond hair and short, scruffy beard, only it’s a bit neater, and there’s gray peppered through it. His warm, excitable voice still crackles like a teenager’s, even as he speaks about his executive roles as creative director of Vice Media and the inaugural YouTube Music Video Awards, airing Sunday night.

As a filmmaker, Mr. Jonze is still directing music videos and pulling puerile “Jackass” pranks with his longtime co-conspirator, Johnny Knoxville, in “Bad Grandpa.” But on Dec. 18, he graduates into midcareer maturity with “Her,” a near-future romance about a man who falls in love with his computer’s sentient operating system. (Think of: “Siri, check the weather. And what are you doing later?”) Mr. Jonze directed Charlie Kaufman’s pyrotechnic scripts for “Being John Malkovich” and “Adaptation” and he (and Dave Eggers) wrote the film “Where the Wild Things Are,” but “Her” is the first feature that Mr. Jonze has written and directed by himself.

“After ‘Where the Wild Things Are,’ I guess I felt more confident as a writer,” Mr. Jonze said, shrugging, as ever, when asked about his motivations. “Probably? I don’t know. It just seemed like I wanted to keep going further with making things that were purely out of my own imagination.”

“Her” stars the typically tortured Joaquin Phoenix as Theodore, a brokenhearted, divorced middle-aged man who works at BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com, writing moving correspondence for people who care to send the very best (and can pay someone else to do it). When lonely Theodore upgrades his computer’s operating system, the disembodied, husky voice of Scarlett Johansson says hello, and tells him to call “her” Samantha. She gamely cleans up his inbox, organizes his hard drive, books his appointments and, ultimately, steals his heart. He takes her (or at least his earpiece) on dinner dates, on long romantic walks and on an old-fashioned trip to a carnival. Theodore’s best friend (Amy Adams) is just happy that he’s happy. His ex-wife (Rooney Mara) is, well, not.

“Her” may sound like a dystopian, satirical treatise on digital culture, but it is not a farce and it is resolutely inconclusive. “I went in to meet with Spike and launched into this diatribe about artificial intelligence,” said the actress Olivia Wilde, whose character ends up on a painfully awkward blind date with Theodore. “He kept saying, ‘That’s cool, but, this is not a movie about technology.’ ”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

'Her' review: Spike Jonze's sci-fi love story rethinks romance

Joaquin phoenix gets serious with an os.

By Todd Gilchrist on December 17, 2013 11:33 am 39 Comments

In a world of seemingly infinite connectivity, we’re constantly hearing about how all of this technology is in fact forcing us apart — whether we're spending more time instant messaging than interacting or looking at our phones instead of the human being on the other side of the dinner table. Spike Jonze’s Her examines one man’s relationship with just such an electronic device. Far from being a cautionary tale, it highlights how technology itself can not only fulfill our emotional needs, but also clarify our relationships with the people it’s meant to connect us with.

Set in an unspecified future just a few years from now, the film stars Joaquin Phoenix ( The Master ) as Theodore, a talented correspondence writer at a website called BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com. Still nursing the pain of his failed marriage to Catherine (Rooney Mara, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo ), Theodore mostly keeps to himself, save for occasional interactions with his neighbor Amy and her husband Charles (Amy Adams and Matt Letscher). But after purchasing a new artificially intelligent operating system that calls itself Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), he develops an unexpected rapport with the device as it evolves into a bona fide companion.

Initially, Samantha seems like a sort of ideal personal assistant; in addition to streamlining Theodore’s inbox and keeping him on top of his responsibilities, she offers occasional comfort and reassurance when he retreats into his head. But Samantha’s programming allows her to grow as she learns, and she becomes as involved with him as he is with her — taking inspiration to explore the world, even if it’s through Theodore’s eyes. But Samantha’s curiosity quickly evolves beyond the common sensory experiences of her human counterpart, and she begins contemplating deeper philosophical ideas. Soon, she is yearning for the same kind of intellectual and emotional gratification she provided for Theodore, forcing him to confront the possibility of losing her as she embarks on her own journey of self-discovery.

Jonze is no stranger to stories about the weird ways in which technology affects our lives, but Her is resonant in a completely different way from his earlier work. It eschews the weirdness of Being John Malkovich and the melancholy of Where The Wild Things Are to explore ideas that are specific and intimate yet shockingly universal. Indeed, Her is only incidentally science fiction — its interactive, reciprocal artificial intelligence is seemingly less possible than inevitable — while Jonze examines the nature of companionship, and the ways in which we define and maintain the relationships that are most important to us.

Notwithstanding the increasing normalcy of internet dating, this is a film that makes the argument that any online relationship can be meaningful, even when it stays online. Where movies like Catfish underscore the potential for these interactions to be phony or facetious, Jonze’s film argues that virtual interaction is valid and meaningful even without physical consummation. In his construction of Her ’s "tomorrowland" future, Jonze predicts that these relationships will not just become prevalent, but socially acceptable, and with few exceptions the characters around Theodore eagerly legitimize the bond between him and Samantha. It not only normalizes Theodore’s behavior, but allows the audience to see the essence of his relationship with Samantha as a natural byproduct of integrating technology into virtually every life experience — in much the same way that sharing one’s aspirations, insecurities, fears, and dreams makes any relationship that much deeper and more meaningful.

Beyond Jonze’s detailed world building, Phoenix and Johannson do an incredible job making us believe that they are two equal entities, and that their relationship is authentic. On screen, the two of them interact via Theodore’s cellphone (which serves as her eyes to his world) and an unobtrusive Bluetooth-style earpiece, but after the initial awkwardness of their introduction it’s easy to forget that she isn’t "real" — or at least as real as he is. That Jonze presents Samantha as a sort of unseen commentator or companion makes us at ease with her physical absence, but Phoenix’s body language — a heroic one-man show of vulnerability — underscores how deeply he cares for her, and how strongly he’s affected by the twists and turns in their relationship.

Simultaneously, the film observes how easy it can be to substitute or mistake technology for real human interaction. When Theodore buys Samantha, it seems pretty clear that he’s looking for something, or someone, to be his partner, even if it’s only virtual, and she quickly becomes the first and often only person he goes to with his experiences. That hermetic bond enables him to avoid interaction with the outside world, not just ignoring possible problems but retreating from the messy unpredictability of the human beings around him. In a strict sense, Theodore is vaguely aware of the risks he runs by dating an OS; he recognizes the limited feasibility of doing things like double dates with Samantha. But he also fails to consider how consuming his relationship becomes, and the film delicately highlights how he achieves a state of normalcy for himself that estranges him from those around him, such as his friend Amy.

But Jonze seems to think through just about every aspect of his idea, and executes it in such a poetic way that it only ever feels like the story of a relationship, as opposed to, say, a technophobic fable or science-fiction conceit. There’s an amusing, recognizable honesty in Theodore and Samantha’s exchanges that highlight moments in "real" relationships: the awkward morning-after conversation that follows their first sexual encounter, the bemused daydreams that accompany a day trip to the beach, the desperate fear of not being able to reach, or find, a person whom you fear is drifting apart from you. And given that Samantha is a computer that learns about the world through her interactions with Theodore, it seems inevitable that she changes to incorporate the experiences she has — just as with a relationship between two people.

At the same time, Theodore’s insecurities and his ingrained pathological responses create the same sorts of conflicts they would with another person, and the evolution of their relationship unfolds both with the awkward humanity of fumbling efforts to communicate and the clarity and perspective of a machine capable of assessing those efforts psychologically. On two occasions, Samantha attempts to compose music as a way of articulating her reaction to their shared experiences, and it’s telling that the second is more complex than the first — snapshots of specific moments that encompass the tone of their relationship and the experiences that led up to each one.

As with Being John Malkovich and Adaptation , Her wraps itself up with an ending that feels indefinite, but complete. The difference between this film and others more openly critical of technology is that the character’s interactions with his operating system would ordinarily stunt or inhibit the ones with the humans around him, but in Her the opposite proves true; ultimately, he’s better able to deal with the failures of his past and understand how not to repeat them in the future.

Ultimately, Her possesses the epic sweep of a science-fiction opus that speculates where we’re going as a species and how we might get there, and yet applies its discoveries to the individual. All of which is why it’s a modest sort of masterpiece, a truly great film that manages to make an unconventional relationship seem enormously rewarding, but mostly because it accomplishes in Theodore’s life what we wish real ones did in ours: teach us about ourselves, and help us to be more — not less — open to love.

Her opens in limited release on Wednesday, December 18th.

The Life and Times of Ben Weinberg

‘Her’ – Film Review and Analysis

“as theodore navigates the complexities of his relationship with samantha, ‘her’ raises profound questions about the nature of love, intimacy, and the impact of technology on human connection.”.

Directed by Spike Jonze, ‘Her’ (2013) is a very thought-provoking film and emotionally resonant exploration of love, loneliness, connection, and the continually evolving relationship between human beings and artificial intelligence. Set in a near-future Los Angeles, the film follows Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), a sensitive and introverted man who develops a deep emotional connection with an artificial intelligence operating system named Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson). A s Theodore navigates the complexities of his relationship with Samantha, ‘Her’ raises profound questions about the nature of love, intimacy, and the impact of technology on human connection.

‘Her’, when it begins, unfolds in a meticulously crafted near-future world where technology seamlessly integrates into everyday life. The film’s urban setting, characterized by sleek minimalist design, towering skyscrapers, and vibrant colors, offers a vision of the future that feels both familiar and slightly surreal. Against this backdrop, Theodore, a melancholic writer, struggles with the recent end of his marriage to Catherine (Rooney Mara) and finds solace in his interactions with ‘Samantha’, an advanced operating system designed to meet his every emotional need.

As Theodore and Samantha’s relationship deepens, the film explores the complexities of human emotions and the blurred boundaries between what is reality and what is fantasy. It also explores how intimacy can be replicated but not replaced when embraced by AI and man despite the boundaries and limitations that can never fade away. Theodore and Samantha’s unconventional romance challenges societal norms and prompts reflection on the nature of intimacy in an increasingly digitized world.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Life and Times of Ben Weinberg to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

“Her” raises two questions that have long preoccupied philosophers. Are nonbiological creatures like Samantha capable of consciousness — at least in theory, if not yet in practice?

Her is a pastel-coloured indie romance, on one hand—a love story between a man and his software, which cleverly mimics—almost mocks—that of a classic romance. On other, it is a dark, compelling movie which submits a warning at its end: keep in check our complicated relationship with technology.

If you’re more of a fan of Terminator-style shoot-em-ups— blood, grease, guns, and explosions—trust me, Her (2013) is certainly not for you. However, if you love a good drama that leaves you with the “tummy giggles,” then Her (2013) is absolutely worth a watch. Rating: 9/10.

When protagonist Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) installs a new operating system, he hears a woman’s voice emerge from the speakers, and he asks her what her name is. She tells him it’s Samantha.

The Zen guru-philosopher Alan Watts plays only a minor role in Spike Jonze’s extraordinary new film Her—which is unsurprising, given that Watts died in 1973, and Her is set in a timeless but...

Writer/director Spike Jonze constructs a beguiling cinematic world in which a man falls in love with a computer program, offering a crash course on the question of what it means to be human.

“Her” may sound like a dystopian, satirical treatise on digital culture, but it is not a farce and it is resolutely inconclusive.

(Warner Bros) Director Spike Jonze replaces the genre’s usual escapism with a vision of the future that reveals hard truths about the present, writes Solvej Schou. What does it mean to be...

Spike Jonze’s Her examines one man’s relationship with just such an electronic device. Far from being a cautionary tale, it highlights how technology itself can not only fulfill our emotional ...

Directed by Spike Jonze, ‘Her’ (2013) is a very thought-provoking film and emotionally resonant exploration of love, loneliness, connection, and the continually evolving relationship between human beings and artificial intelligence.