Module 14: Small Group Communication

The reflective-thinking method for decision-making, learning objectives.

Identify the steps of the reflective-thinking method for decision-making in small groups.

The reflective-thinking method originated with John Dewey, a leading American social philosopher. This method provides a structured way for small groups to approach decision-making and problem-solving, especially as people are increasingly distracted by electronics or overwhelmed by access to complex and endless information. Dewey maintained that people need a scientific method and a “disciplined mind” to both tap into the strength of a group and to come up with logical solutions. The term disciplined mind refers to gaining intellectual control, rather than just being emotionally based. Discipline in this context isn’t seen as restrictive; in fact, Dewey believed that having a disciplined mind offers intellectual freedom. While the reflective-thinking method can be applied to individual decision-making, we’ll apply it here to small group communication. [1] We’ll explore the five steps of the reflective-thinking method below.

- What steps should our planning team take to prepare and execute an appropriate and fun activity for children in foster care? Notice that this statement is specific and unbiased about the problem to be solved and allows for various possible solutions.

- Analyze the problem . Once again, this step preemptively prevents a small group from jumping to solutions. Here, the group needs to explore the problem in depth, which involves gathering material and researching what has been done, if anything, in the past. You need solid evidence, data, and even anecdotal evidence to better analyze what’s going on. The group planning a holiday event for children in foster care might look at what has been done in past years and gather feedback about those events. The group might create and send an online survey to foster parents and ask what types of activities their children are most interested in. The group might consult with a trauma expert about what types of considerations they should take to ensure any activity is safe and inclusive. Finally, the group would likely research its budget, timelines, demographic information of the children, etc.

- The event fits into our budget of $3,000.

- The event is appropriate for ages 2–18.

- The event allows children and foster parents to interact with one another.

- The event feels safe and inclusive for all children.

- The event is held in convenient locations at appropriate times for younger children.

- The event is relatively simple.

- Brunch, Polar Express party, Winter Wonderland theme, gift drive, gingerbread-making activity, hot chocolate bar, lots of lights, live DJ, mariachi band, etc.

- Select the best solution . Finally, you work to ascertain the best solution. You evaluate the merits and feasibility of each proposed solution. Use the criteria established in Step 3 to evaluate each possible solution. How do you define best ? That definition might be the most feasible, the most effective, the most politically viable, the quickest, etc. The discussion for the event planning team might look something like this:

We kept going back to the simple part, so Polar Express and Winter Wonderland themed events were off the table. We decided the brunch idea best fit the criteria for timing, budget, and location. Then, we remembered the kid-friendly and interactive part, and added an element of a gingerbread-making project for children of all ages. To help children and parents get to know each other in a safe, low-key environment, we decided to have each child or family display their gingerbread houses on tables and let others write positive comments about them.

Once the group decides on its final solution, they can continue further planning, or present their decision (when applicable).

Practice Question

- Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . United States, McGraw-Hill Education, 2020. ↵

- The Reflective-Thinking Method for Decision Making. Authored by : Susan Bagley-Koyle with Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

John Dewey on Education: Impact & Theory

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- John Dewey (1859—1952) was a psychologist, philosopher, and educator who made contributions to numerous topics in philosophy and psychology. His work continues to inform modern philosophy and educational practice today.

- Dewey was an influential pragmatist, a movement that rejected most philosophy at the time in favor of the belief that things that work in a practical situation are true, while those that do not are false. This view would go on to influence his educational philosophy.

- Dewey was also a functionalist. Inspired by the ideas of Charles Darwin, he believed that humans develop behaviors as an adaptation to their environment.

- Dewey’s influential education is marked by an emphasis on the belief that people learn and grow as a result of their experiences and interactions with the world. He aimed to shape educational environments so that they would promote active inquiry but did not do away with traditional instruction altogether.

- Outside of education and philosophy, Dewey also devised a theory of emotions in response to Darwin’s ideas. In this theory, he argued that the behaviors that arise from emotions were, at some point, beneficial to the survival of organisms.

John Dewey was an American psychologist, philosopher, educator, social critic, and political activist. He made contributions to numerous fields and topics in philosophy and psychology.

Besides being a primary originator of both functionalism and behaviorism psychology , Dewey was a major inspiration for several movements that shaped 20th-century thought, including empiricism, humanism, naturalism, contextualism, and process philosophy (Simpson, 2006).

Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont, in 1859 and began his career at the University of Michigan before becoming the chairman of the department of philosophy, psychology, and pedagogy at the University of Chicago.

In 1899, Dewey was elected president of the American Psychological Association and became president of the American Philosophical Association five years later.

Dewey traveled as a philosopher, social and political theorist, and educational consultant and remained outspoken on education, domestic and international politics, and numerous social movements.

Dewey’s views and writings on educational theory and practice were widely read and accepted. He held that philosophy, pedagogy, and psychology were closely interrelated.

Dewey also believed in an “instrumentalist” theory of knowledge, in which ideas are seen to exist mainly as instruments for creating solutions to problems encountered in the environment (Simpson, 2006).

Contributions to Philosophy and Psychology

Dewey is one of the central figures and founders of pragmatism in America despite not identifying himself as a pragmatist.

Pragmatism teaches that things that are useful — meaning that they work in a practical situation — are true, and what does not work is false (Hildebrand, 2018).

This rejected the threads of epistemology and metaphysics that ran through modern philosophy in favor of a naturalistic approach that viewed knowledge as an active adaptation of humans to their environment (Hildebrand, 2018).

Dewey held that value was not a function of purely social construction but a quality inherent to events. Dewey also believed that experimentation was a reliable enough way to determine the truth of a concept.

Functionalism

Dewey is considered a founder of the Chicago School of Functional Psychology, inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, as well as the ideas of William James and Dewey’s own instrumental philosophy.

As chair of philosophy, psychology, and education at the University of Chicago from 1894-1904, Dewey was highly influential in establishing the functional orientation amongst psychology faculty like Angell and Addison Moore.

Scholars widely consider Dewey’s 1896 paper, The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology , to be the first major work in the functionalist school.

In this work, Dewey attacked the methods of psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener, who used stimulus-response analysis as the basis of psychological theories.

Psychologists such as Wund and Titchener believed that all human behaviors could be broken down into a series of fundamental laws and that all human behavior originates as a learned adaptation to the presence of certain stimuli in one’s environment (Backe, 2001).

Dewey considered Wundt and Titchener’s approach to be flawed because it ignored both the continuity of human behavior and the role that adaptation plays in creating it.

In contrast, Dewey’s functionalism sought to consider organisms in total as they functioned in their environment. Rather than being passive receivers of stimuli, Dewey perceived organisms as active perceivers (Backe, 2001).

Chicago School

The Chicago school refers to the functionalist approach to psychology that emerged at the University of Chicago in the late 19th century. Key tenets of functional psychology included:

- Studying the adaptive functions of consciousness and how mental processes help organisms adjust to their environment

- Explaining psychological phenomena in terms of their biological utility

- Focusing on the practical operations of the mind rather than contents of consciousness

Educational Philosophy

John Dewey was a notable educational reformer and established the path for decades of subsequent research in the field of educational psychology.

Influenced by his philosophical and psychological theories, Dewey’s concept of instrumentalism in education stressed learning by doing, which was opposed to authoritarian teaching methods and rote learning.

These ideas have remained central to educational philosophy in the United States. At the University of Chicago, Dewey founded an experimental school to develop and study new educational methods.

He experimented with educational curricula and methods and advocated for parental participation in the educational process (Dewey, 1974).

Dewey’s educational philosophy highlights “pragmatism,” and he saw the purpose of education as the cultivation of thoughtful, critically reflective, and socially engaged individuals rather than passive recipients of established knowledge.

Dewey rejected the rote-learning approach driven by a predetermined curriculum, the standard teaching method at the time (Dewey, 1974).

Dewey also rejected so-called child-centered approaches to education that followed children’s interests and impulses uncritically. Dewey did not propose an entirely hands-off approach to learning.

Dewey believed that traditional subjects were important but should be integrated with the strengths and interests of the learner.

In response, Dewey developed a concept of inquiry, which was prompted by a sense of need and was followed by intellectual work such as defining problems, testing hypotheses, and finding satisfactory solutions.

Dewey believed that learning was an organic cycle of doubt, inquiry, reflection, and the reestablishment of one’s sense of understanding.

In contrast, the reflexive arc model of learning popular in his time thought of learning as a mechanical process that could be measured by standardized tests without reference to the role of emotion or experience in learning.

Rejecting the assumption that all of the big questions and ideas in education are already answered, Dewey believed that all concepts and meanings could be open to reinvention and improvement and that all disciplines could be expanded with new knowledge, concepts, and understandings (Dewey, 1974).

Philosophy of Education

Dewey believed that people learn and grow as a result of their experiences and interactions with the world. These compel people to continually develop new concepts, ideas, practices, and understandings.

These, in turn, are refined through and continue to mediate the learner’s life experiences and social interactions. Dewey believed that (Hargraves, 2021):

Empirical Validity and Criticism

Despite its wide application in modern theories of education, many scholars have noted the lack of empirical evidence in favor of Dewey’s theories of education directly.

Nonetheless, Dewey’s theory of how students learn aligns with empirical studies that examine the positive impact of interactions with peers and adults on learning (Göncü & Rogoff, 1998).

Researchers have also found a link between heightened engagement and learning outcomes.

This has resulted in the development of educational strategies such as making meaningful connections to students” home lives and encouraging student ownership of their learning (Turner, 2014).

Theory of Emotions

Dewey vs. darwin.

Another influential piece of philosophy that Dewey created was his theory of emotion (Cunningham, 1995).

Dewey reconstructed Darwin’s theory of emotions, which he believed was flawed for assuming that the expression of emotion is separate from and subsequent to the emotion itself.

Darwin also argued that behavior that expresses emotion serves the individual in some way when the individual is in a particular state of mind. These can also cause behaviors that are not useful.

Dewey, however, claimed that the function of emotional behaviors is not to express emotion but to be acts that value someone’s survival. Dewey believed that emotion is separate from other behaviors because it involves an attitude toward an object. The intention of the emotion informs the behaviors that result (Cunningham, 1995).

Dewey also rejected Darwin’s principle that some expressions of emotions can be explained as cases where one emotion can be expressed by actions that are the exact opposite of another.

Dewey again believed that even these opposite behaviors have purposes in themselves (Cunningham, 1995).

Dewey vs. James

Dewey argued against James’s serial theory of emotions, seeing emotion and stimuli as one simultaneous coordinated act.

William James proposed a serial theory of emotion , in which an emotional experience progresses through several sequential stages:

- An object or idea functions as a stimulus

- This stimulus leads to a behavioral response

- The response is then followed by an emotional excitation or affect

An example would be seeing a bear (stimulus), running away (response), and then feeling afraid (emotion).

Dewey, however, argued that emotion and stimulus form a unified, simultaneous act that cannot be separated in this way.

He uses the example of a frightened reaction to a bear to illustrate his point:

- The “bear” itself is constituted by the coordinated sensory excitations of the eyes, touch, etc.

- The feeling of “terror” is constituted by disturbances across glandular, muscular systems.

- Rather than stimulus → response → emotion, these are partial activities within the one act of perceiving the frightening bear and running away in fear.

- The bear object and the fear emotion are two aspects of the total coordinated activity, happening at once.

So, where James treated stimulus, response, and emotion as sequential stages in an emotional episode, Dewey saw them as “minor acts” coming together in a unified conscious experience.

He maintained James was artificially separating elements that occur as part of one ongoing activity of coordination.

The key difference is that Dewey did not believe it was possible to isolate stimulus, response, and affect as self-sufficient events. They exist meaningfully only within the total act – hence why he emphasizes their simultaneity.

Backe, A. (2001). John Dewey and early Chicago functionalism. History of Psychology, 4 (4), 323.

Cunningham, S. (1995). Dewey on emotions: recent experimental evidence. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, 31(4), 865-874.

Dewey, J. (1974). John Dewey on education: Selected writings .

Göncü, A., & Rogoff, B. (1998). Children’s categorization with varying adult support. American Educational Research Journal, 35 (2), 333-349.

Hargraves, V. (2021). Dewey’s educational philosophy .

Hildebrand, D. (2018). John Dewey.

Simpson, D. J. (2006). John Dewey (Vol. 10). Peter Lang.

Turner, J. C. (2014). Theory-based interventions with middle-school teachers to support student motivation and engagement. In Motivational interventions . Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

A John Dewey source page

Originally published as:.

John Dewey. "The Analysis of a Complete Act of Thought" Chapter 6 in How we think . Lexington, Mass: D.C. Heath, (1910): 68-78.

Editors' notes

No notes yet

Related Documents

No links yet

Site Navigation

- Selected Documents

- Dewey Bibliography

- Mead Project Inventory

the Web Mead Project

How We Think

Chapter 6: the analysis of a complete act of thought, table of contents | next | previous.

Object of Part Two

AFTER a brief consideration in the first chapter of the nature of reflective thinking, we turned, in the second, to the need for its training. Then we took up the resources, the difficulties, and the aim of its training. The purpose of this discussion was to set before the student the general problem of the training of mind. The purport of the second part, upon which we are now entering, is giving a fuller statement of the nature and normal growth of thinking, preparatory to considering in the concluding part the special problems that arise in connection with its education.

In this chapter we shall make an analysis of the process of thinking into its steps or elementary constituents, basing the analysis upon descriptions of a number of extremely simple, but genuine, cases of reflective experience. [1]

A simple case of practical deliberation

I. "The other day when I was down town on 16th Street a clock caught my eye. I saw that the hands pointed to 12.20. This suggested that I had an engagement at 124th Street, at one o'clock. I reasoned that

(69) as it had taken me an hour to come down on a surface car, I should probably be twenty minutes late if I returned the same way. I might save twenty minutes by a subway express. But was there a station near? If not, I might lose more than twenty minutes in looking for one. Then I thought of the elevated, and I saw there was such a line within two blocks. But where was the station ? If it were several blocks above or below the street I was on, I should lose time instead of gaining it. My mind went back to the subway express as quicker than the elevated; furthermore, I remembered that it went nearer than the elevated to the part Of I 124th Street I wished to reach, so that time would be saved at the end of the journey. I concluded in favor of the subway, and reached my destination by one o'clock."

A simple case of reflection upon an observation

2. "Projecting nearly horizontally from the upper deck of the ferryboat on which I daily cross the river, is a long white pole, bearing a gilded ball at its tip. It suggested a flagpole when I first saw it; its color shape, and gilded ball agreed with this idea, and these reasons seemed to justify me in this belief. But soon difficulties presented themselves. The pole was nearly horizontal, an unusual position for a flagpole; in the next place, there was no pulley, ring, or cord by which to attach a flag; finally, there were elsewhere two vertical staffs from which flags were occasionally flown. It seemed probable that the pole was not there for flag-flying.

"I then tried to imagine all possible purposes of such a pole, and to consider for which of these it was best suited : (a) Possibly it was an ornament. But as all the ferryboats and even the tugboats carried like poles,

(70) this hypothesis was rejected. (b) Possibly it was the terminal of a wireless telegraph. But the same considerations made this improbable. Besides, the more natural place for such a terminal would be the highest part of the boat, on top of the pilot house. (c) Its purpose might be to point out the direction in which the boat is moving.

"In support of this conclusion, I discovered that the pole was lower than the pilot house, so that the steersman could easily see it. Moreover, the tip was enough higher than the base, so that, from the pilot's position, it must appear to project far out in front of the boat. Moreover, the pilot being near the front of the boat, be would need some such guide as to its direction. Tugboats would also need poles for such a purpose. This hypothesis was so much more probable than the others that I accepted it. I formed the conclusion that the pole was set up for the purpose of showing the pilot the direction in which the boat pointed, to enable him to steer correctly."

A simple case of reflection involving experiment

3. "In washing tumblers in hot soapsuds and placing them mouth downward on a plate, bubbles appeared on the outside of the mouth of the tumblers and then went inside. Why? The presence of bubbles suggests air, which I note must come from inside the tumbler. I see that the soapy water on the plate prevents escape of the air save as it may be caught in bubbles. But why should air leave the tumbler ? There was no substance entering to force it out. It must have expanded. It expands by increase of heat or by decrease of pressure, or by both. Could the air have become heated after the tumbler was taken from the hot suds? Clearly not the air that was already entangled

(71) in the water. If heated air was the cause , cold air must have entered in transferring the tumblers from the suds to the plate. I test to see if this supposition is true by taking several more tumblers out. Some I shake so as to make sure of entrapping cold air in them. Some I take out holding mouth downward in order to prevent cold air from entering. Bubbles appear on the outside of every one of the former and on none of the latter. I must be right in my inference. Air from the outside must have been expanded by the heat of the tumbler, which explains the appearance of the bubbles on the outside.

"But why do they then go inside? Cold contracts. The tumbler cooled and also the air inside it. Tension was removed, and hence bubbles appeared inside. To be sure of this, I test by placing a cup of ice on the tumbler while the bubbles are still forming outside. They soon reverse."

These three cases have been purposely selected so as to form a series from the more rudimentary to more complicated cases of reflection. The first illustrates the kind of thinking done by every one during the day's business, in which neither the data, nor the ways of dealing with them, take one outside the limits of everyday experience. The last furnishes a case in which neither problem nor mode of solution would have been likely to occur except to one with some prior scientific training. The second case forms a natural transition; its materials lie well within the bounds of everyday, unspecialized experience; but the problem, instead of being directly involved in the person's business, arises indirectly out of his activity, and accordingly appeals to a somewhat theoretic and impartial interest. We

(72) shall deal, in a later chapter, with the evolution of abstract thinking out of that which is relatively practical and direct; here we are concerned only with the common elements found in all the types.

Five distinct steps in reflection

Upon examination, each instance reveals, more or less clearly, five logically distinct steps: (i) a felt difficulty; (ii) its location and definition; (iii) suggestion of possible solution; (iv) development by reasoning of the bearings of the suggestion; (v) further observation and experiment leading to its acceptance or rejection; that is, the conclusion of belief or disbelief.

(a) in the lack of adaptation of means to end

I. The first and second steps frequently fuse into one. The difficulty may be felt with sufficient definiteness as to set the mind at once speculating upon its probable solution, or an undefined uneasiness and shock may come first, leading only later to definite attempt to find out what is the matter. Whether the two steps are distinct or blended, there is the factor emphasized in our original account of reflection ― viz. the perplexity or problem. In the first of the three cases cited, the difficulty resides in the conflict between conditions at hand and a desired and intended result, between an end and the means for reaching it. The purpose of keeping an engagement at a certain time, and the existing hour taken in connection with the location, are not congruous. The object of thinking is to introduce congruity between the two. The given conditions cannot themselves be altered; time will not go backward nor will the distance between 16th Street and 124th Street shorten itself. The problem is the discovery of intervening terms which when inserted between the remoter end and the given means will harmonize them with each other.

(b) in identifying the character of the object

In the second case, the difficulty experienced is the incompatibility of a suggested and (temporarily) accepted belief that the pole is a flagpole, with certain other facts. Suppose we symbolize the qualities that suggest flagpole by the letters a, b, c; those that oppose this suggestion by the letters p, q, r. There is, of course, nothing inconsistent in the qualities themselves; but in pulling the mind to different and incongruous conclusions they conflict ― hence the problem. Here the object is the discovery of some object (0), of which a, b, c, and p, q, r, may all be appropriate traits-just as, in our first case, it is to discover a course of action which will combine existing conditions and a remoter result in a single whole. The method of solution is also the same: discovery of intermediate qualities (the position of the pilot house, of the pole, the need of an index to the boat's direction) symbolized by d, g, 1, o, which bind together otherwise incompatible traits.

(c) in explaining an unexpected event

In the third case, an observer trained to the idea of natural laws or uniformities finds something odd or exceptional in the behavior of the bubbles. The problem is to reduce the apparent anomalies to instances of well-established laws. Here the method of solution is also to seek for intermediary terms which will connect, by regular linkage, the seemingly extraordinary movements of the bubbles with the conditions known to follow from processes supposed to be operative.

2. Definition of the difficulty

2. As already noted, the first two steps, the feeling of a discrepancy, or difficulty, and the acts of observation that serve to define the character of the difficulty may, in a given instance, telescope together. In cases of striking novelty or unusual perplexity, the difficulty, however, is likely to present itself at first as a shock, as

(74) emotional disturbance, as a more or less vague feeling of the unexpected, of something queer, strange, funny, or disconcerting. In such instances, there are necessary observations deliberately calculated to bring to light just what is the trouble, or to make clear the specific character of the problem. In large measure, the existence or non-existence of this step makes the difference between reflection proper, or safeguarded critical inference and uncontrolled thinking. Where sufficient pains to locate the difficulty are not taken, suggestions for its resolution must be more or less random. Imagine a doctor called in to prescribe for a patient. The patient tells him some things that are wrong; his experienced eye, at a glance, takes in other signs of a certain disease. But if he permits the suggestion of this special disease to take possession prematurely of his mind, to become an accepted conclusion, his scientific thinking is by that much cut short. A large part of his technique, as a skilled practitioner, is to prevent the acceptance of the first suggestions that arise; even, indeed, to postpone the occurrence of any very definite suggestion till the trouble ― the nature of the problem ― has been thoroughly explored. In the case of a physician this proceeding is known as diagnosis, but a similar inspection is required in every novel and complicated situation to prevent rushing to a conclusion. The essence of critical thinking is suspended judgment; and the essence of this suspense is inquiry to determine the nature of the problem before proceeding to attempts at its solution. This, more than any other thing, transforms mere inference into tested inference, suggested conclusions into proof.

3. The third factor is suggestion. The situation in

3. Occurance of a suggested explanation or possible solution

(75) which the perplexity occurs calls up something not present to the senses : the present location, the thought of subway or elevated train; the stick before the eyes, the idea of a flagpole, an ornament, an apparatus for wireless telegraphy; the soap bubbles, the law of expansion of bodies through heat and of their contraction through cold. (a) Suggestion is the very heart of inference ; it involves going from what is present to something absent. Hence, it is more or less speculative, adventurous. Since inference goes beyond what is actually present, it involves a leap, a jump, the propriety of which cannot be absolutely warranted in advance, no matter what precautions be taken. Its control is indirect, on the one hand, involving the formation of habits of mind which are at once enterprising and cautious; and on the other hand , involving the selection and arrangement of the particular facts upon perception of which suggestion issues. (b) The suggested conclusion so far as it is not accepted but only tentatively entertained constitutes an idea. Synonyms for this are supposition, conjecture, guess, hypothesis, and (in elaborate cases) theory. Since suspended belief, or the postponement of a final conclusion pending further evidence, depends partly upon the presence of rival conjectures as to the best course to pursue or the probable explanation to favor, cultivation of a variety of alternative suggestions is an important factor in good thinking.

4. The rational elaboration of an idea

4. The process of developing the bearings ― or, as they are more technically termed, the implications ― of any idea with respect to any problem, is termed reasoning . [2] As an idea is inferred from given facts, so reasoning

(76) sets out from an idea. The idea of elevated road is developed into the idea of difficulty of locating station, length of time occupied on the journey, distance of station at the other end from place to be reached. In the second case, the implication of a flagpole is seen to be a vertical position; of a wireless apparatus, location on a high part of the ship and, moreover, absence from every casual tugboat; while the idea of index to direction in which the boat moves, when developed, is found to cover all the details of the case.

Reasoning has the same effect upon a suggested solution as more intimate and extensive observation has upon the original problem. Acceptance of the suggestion in its first form is prevented by looking into it more thoroughly. Conjectures that seem plausible at first sight are often found unfit or even absurd when their full consequences are traced out. Even when reasoning out the bearings of a supposition does not lead to rejection, it develops the idea into a form in which it is more apposite to the problem. Only when, for example, the conjecture that a pole was an index-pole had been thought out into its bearings could its particular applicability to the case in hand be judged. Suggestions at first seemingly remote and wild are frequently so transformed by being elaborated into what follows from them as to become apt and fruitful. The development of an idea through reasoning helps at least to supply the intervening or intermediate terms that link together into a consistent whole apparently discrepant extremes (ante, p. 72).

Corroboration of an idea and formation of a concluding belief

5. The concluding and conclusive step is some kind of experimental corroboration, or verification, of the conjectural idea. Reasoning shows that if the idea be adopted, certain consequences follow. So far the conclusion is hypothetical or conditional. If we look and find present all the conditions demanded by the theory, and if we find the characteristic traits called for by rival alternatives to be lacking, the tendency to believe, to accept, is almost irresistible. Sometimes direct observation furnishes corroboration, as in the case of the pole on the boat. In other cases, as in that of the bubbles, experiment is required; that is, conditions are deliberately arranged in accord with the requirements of an idea or hypothesis to see if the results theoretically indicated by the idea actually occur. If it is found that the experimental results agree with the theoretical, or rationally deduced, results, and if there is reason to believe that only the conditions in question would yield such results, the confirmation is so strong as to induce a conclusion at least until contrary facts shall indicate the advisability of its revision.

Thinking comes between observations at the beginning and at the end

Observation exists at the beginning and again at the end of the process: at the beginning, to determine more definitely and precisely the nature of the difficulty to be dealt with; at the end, to test the value of some hypothetically entertained conclusion. Between those two termini of observation, we find the more distinctively mental aspects of the entire thought-cycle : (i) inference, the suggestion of an explanation or solution, (ii) reasoning, the development of the bearings and implications of the suggestion. Reasoning requires some experimental observation to confirm it, while experiment can be economically and fruitfully conducted only

(78) on the basis of an idea that has been tentatively developed by reasoning.

The trained mind one that judges the extent of each step advisable in a given situation

The disciplined, or logically trained, mind ― the aim of the educative process -is the mind able to judge how far each of these steps needs to be carried in any particular situation. No cast-iron rules can be laid down. Each case has to be dealt with as it arises, on the basis of its importance and of the context in which it occurs. To take too much pains in one case is as foolish -as illogical ― as to take too little in another. At one extreme, almost any conclusion that insures prompt and unified action may be better than any long delayed conclusion; while at the other, decision may have to be postponed for a long period ― perhaps for a lifetime. The trained mind is the one that best grasps the degree of observation, forming of ideas, reasoning, and experimental testing required in any special case, and that profits the most, in future thinking, by mistakes made in the past. What is important is that the mind should be sensitive to problems and skilled in methods of attack and solution.

These are taken, almost verbatim, from the class papers of students.

- This term is sometimes extended to denote the entire reflective process-just as inference (which in the sense of test is best reserved for the third step) is sometimes used in the same broad sense. But reasoning (or ratiocination) seems to be peculiarly adapted to express what the older writers called the "notional " or " dialectic " process of developing the meaning of a given idea.

©2007 The Mead Project.

The original published version of this document is in the public domain. The Mead Project exercises no copyrights over the original text.

This page and related Mead Project pages constitute the personal web-site of Dr. Lloyd Gordon Ward (retired), who is responsible for its content. Although the Mead Project continues to be presented through the generosity of Brock University, the contents of this page do not reflect the opinion of Brock University. Brock University is not responsible for its content.

Fair Use Statement:

Scholars are permitted to reproduce this material for personal use. Instructors are permitted to reproduce this material for educational use by their students. Otherwise, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, for the purpose of profit or personal benefit, without written permission from the Mead Project. Permission is granted for inclusion of the electronic text of these pages, and their related images in any index that provides free access to its listed documents.

The Mead Project, c/o Dr. Lloyd Gordon Ward, 44 Charles Street West, Apt. 4501, Toronto Ontario Canada M4Y 1R8

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19.3 Group Problem Solving

Learning objective.

- Identify and describe how to implement seven steps for group problem solving.

No matter who you are or where you live, problems are an inevitable part of life. This is true for groups as well as for individuals. Some groups—especially work teams—are formed specifically to solve problems. Other groups encounter problems for a wide variety of reasons. Within a family group, a problem might be that a daughter or son wants to get married and the parents do not approve of the marriage partner. In a work group, a problem might be that some workers are putting in more effort than others, yet achieving poorer results. Regardless of the problem, having the resources of a group can be an advantage, as different people can contribute different ideas for how to reach a satisfactory solution.

Once a group encounters a problem, the questions that come up range from “Where do we start?” to “How do we solve it?” While there are many ways to approach a problem, the American educational philosopher John Dewey’s reflective thinking sequence has stood the test of time. This seven-step process (Adler, R., 1996) has produced positive results and serves as a handy organizational structure. If you are member of a group that needs to solve a problem and don’t know where to start, consider these seven simple steps:

- Define the problem

- Analyze the problem

- Establish criteria

- Consider possible solutions

- Decide on a solution

- Implement the solution

- Follow up on the solution

Let’s discuss each step in detail.

Define the Problem

If you don’t know what the problem is, how do you know you can solve it? Defining the problem allows the group to set boundaries of what the problem is and what it is not and to begin to formalize a description or definition of the scope, size, or extent of the challenge the group will address. A problem that is too broadly defined can overwhelm the group. If the problem is too narrowly defined, important information will be missed or ignored.

In the following example, we have a Web-based company called Favorites that needs to increase its customer base and ultimately sales. A problem-solving group has been formed, and they start by formulating a working definition of the problem.

Too broad: “Sales are off, our numbers are down, and we need more customers.”

More precise: “Sales have been slipping incrementally for six of the past nine months and are significantly lower than a seasonally adjusted comparison to last year. Overall, this loss represents a 4.5 percent reduction in sales from the same time last year. However, when we break it down by product category, sales of our nonedible products have seen a modest but steady increase, while sales of edibles account for the drop off and we need to halt the decline.”

Analyze the Problem

Now the group analyzes the problem, trying to gather information and learn more. The problem is complex and requires more than one area of expertise. Why do nonedible products continue selling well? What is it about the edibles that is turning customers off? Let’s meet our problem solvers at Favorites.

Kevin is responsible for customer resource management. He is involved with the customer from the point of initial contact through purchase and delivery. Most of the interface is automated in the form of an online “basket model,” where photographs and product descriptions are accompanied by “buy it” buttons. He is available during normal working business hours for live chat and voice chat if needed, and customers are invited to request additional information. Most Favorites customers do not access this service, but Kevin is kept quite busy, as he also handles returns and complaints. Because Kevin believes that superior service retains customers while attracting new ones, he is always interested in better ways to serve the customer. Looking at edibles and nonedibles, he will study the cycle of customer service and see if there are any common points—from the main Web page, through the catalog, to the purchase process, and to returns—at which customers abandon the sale. He has existing customer feedback loops with end-of-sale surveys, but most customers decline to take the survey and there is currently no incentive to participate.

Mariah is responsible for products and purchasing. She wants to offer the best products at the lowest price, and to offer new products that are unusual, rare, or exotic. She regularly adds new products to the Favorites catalog and culls underperformers. Right now she has the data on every product and its sales history, but it is a challenge to represent it. She will analyze current sales data and produce a report that specifically identifies how each product—edible and nonedible—is performing. She wants to highlight “winners” and “losers” but also recognizes that today’s “losers” may be the hit of tomorrow. It is hard to predict constantly changing tastes and preferences, but that is part of her job. It’s not all science, and it’s not all art. She has to have an eye for what will catch on tomorrow while continuing to provide what is hot today.

Suri is responsible for data management at Favorites. She gathers, analyzes, and presents information gathered from the supply chain, sales, and marketing. She works with vendors to make sure products are available when needed, makes sales predictions based on past sales history, and assesses the effectiveness of marketing campaigns.

The problem-solving group members already have certain information on hand. They know that customer retention is one contributing factor. Attracting new customers is a constant goal, but they are aware of the well-known principle that it takes more effort to attract new customers than to keep existing ones. Thus, it is important to insure a quality customer service experience for existing customers and encourage them to refer friends. The group needs to determine how to promote this favorable customer behavior.

Another contributing factor seems to be that customers often abandon the shopping cart before completing a purchase, especially when purchasing edibles. The group members need to learn more about why this is happening.

Establish Criteria

Establishing the criteria for a solution is the next step. At this point, information is coming in from diverse perspectives, and each group member has contributed information from their perspective, even though there may be several points of overlap.

Kevin: Customers who complete the postsale survey indicate that they want to know (1) what is the estimated time of delivery, (2) why a specific item was not in stock and when it will be available, and (3) why their order sometimes arrives with less than a complete order, with some items back-ordered, without prior notification.

He notes that a very small percentage of customers complete the postsale survey, and the results are far from scientific. He also notes that it appears the interface is not capable of cross-checking inventory to provide immediate information concerning back orders, so that the customer “buys it” only to learn several days later that it was not in stock. This seems to be especially problematic for edible products, because people may tend to order them for special occasions like birthdays and anniversaries. But we don’t really know this for sure because of the low participation in the postsale survey.

Mariah: There are four edible products that frequently sell out. So far, we haven’t been able to boost the appeal of other edibles so that people would order them as a second choice when these sales leaders aren’t available. We also have several rare, exotic products that are slow movers. They have potential, but currently are underperformers.

Suri: We know from a zip code analysis that most of our customers are from a few specific geographic areas associated with above-average incomes. We have very few credit cards declined, and the average sale is over $100. Shipping costs represent on average 8 percent of the total sales cost. We do not have sufficient information to produce a customer profile. There is no specific point in the purchase process where basket abandonment tends to happen; it happens fairly uniformly at all steps.

Consider Possible Solutions to the Problem

The group has listened to each other and now starts to brainstorm ways to address the challenges they have addressed while focusing resources on those solutions that are more likely to produce results.

Kevin: Is it possible for our programmers to create a cross-index feature, linking the product desired with a report of how many are in stock? I’d like the customer to know right away whether it is in stock, or how long they may have to wait. As another idea, is it possible to add incentives to the purchase cycle that won’t negatively impact our overall profit? I’m thinking a small volume discount on multiple items, or perhaps free shipping over a specific dollar amount.

Mariah: I recommend we hold a focus group where customers can sample our edible products and tell us what they like best and why. When the best sellers are sold out, could we offer a discount on related products to provide an instant alternative? We might also cull the underperforming products with a liquidation sale to generate interest.

Suri: If we want to know more about our customers, we need to give them an incentive to complete the postsale survey. How about a 5 percent off coupon code for the next purchase to get them to return and to help us better identify our customer base? We may also want to build in a customer referral rewards program, but it all takes better data in to get results out. We should also explore the supply side of the business by getting a more reliable supply of the leading products and trying to get discounts that are more advantageous from our suppliers, especially in the edible category.

Decide on a Solution

Kevin, Mariah, and Suri may want to implement all the solution strategies, but they do not have the resources to do them all. They’ll complete a cost-benefit analysis , which ranks each solution according to its probable impact. The analysis is shown in Table 19.6 “Cost-Benefit Analysis” .

Table 19.6 Cost-Benefit Analysis

Now that the options have been presented with their costs and benefits, it is easier for the group to decide which courses of action are likely to yield the best outcomes. The analysis helps the group members to see beyond the immediate cost of implementing a given solution. For example, Kevin’s suggestion of offering free shipping won’t cost Favorites much money, but it also may not pay off in customer goodwill. And even though Mariah’s suggestion of having a focus group might sound like a good idea, it will be expensive and its benefits are questionable.

A careful reading of the analysis indicates that Kevin’s best suggestion is to integrate the cross-index feature in the ordering process so that customers can know immediately whether an item is in stock or on back order. Mariah, meanwhile, suggests that searching for alternative products is probably the most likely to benefit Favorites, while Suri’s two supply-side suggestions are likely to result in positive outcomes.

Implement the Solution

Kevin is faced with the challenge of designing the computer interface without incurring unacceptable costs. He strongly believes that the interface will pay for itself within the first year—or, to put it more bluntly, that Favorites’ declining sales will get worse if the Web site does not have this feature soon. He asks to meet with top management to get budget approval and secures their agreement, on one condition: he must negotiate a compensation schedule with the Information Technology consultants that includes delayed compensation in the form of bonuses after the feature has been up and running successfully for six months.

Mariah knows that searching for alternative products is a never-ending process, but it takes time and the company needs results. She decides to invest time evaluating products that competing companies currently offer, especially in the edible category, on the theory that customers who find their desired items sold out on the Favorites Web site may have been buying alternative products elsewhere instead of choosing an alternative from Favorites’s product lines.

Suri decides to approach the vendors of the four frequently sold-out products and ask point blank, “What would it take to get you to produce these items more reliably in greater quantities?” By opening the channel of communication with these vendors, she is able to motivate them to make modifications that will improve the reliability and quantity. She also approaches the vendors of the less popular products with a request for better discounts in return for their cooperation in developing and test-marketing new products.

Follow Up on the Solution

Kevin: After several beta tests, the cross-index feature was implemented and has been in place for thirty days. Now customers see either “in stock” or “available [mo/da/yr]” in the shopping basket. As expected, Kevin notes a decrease in the number of chat and phone inquiries to the effect of, “Will this item arrive before my wife’s birthday?” However, he notes an increase in inquiries asking, “Why isn’t this item in stock?” It is difficult to tell whether customer satisfaction is higher overall.

Mariah: In exploring the merchandise available from competing merchants, she got several ideas for modifying Favorites’ product line to offer more flavors and other variations on popular edibles. Working with vendors, she found that these modifications cost very little. Within the first thirty days of adding these items to the product line, sales are up. Mariah believes these additions also serve to enhance the Favorites brand identity, but she has no data to back this up.

Suri: So far, the vendors supplying the four top-selling edibles have fulfilled their promise of increasing quantity and reliability. However, three of the four items have still sold out, raising the question of whether Favorites needs to bring in one or more additional vendors to produce these items. Of the vendors with which Favorites asked to negotiate better discounts, some refused, and two of these were “stolen” by a competing merchant so that they no longer sell to Favorites. In addition, one of the vendors that agreed to give a better discount was unexpectedly forced to cease operations for several weeks because of a fire.

This scenario allows us to see that the problem may have several dimensions as well as solutions, but resources can be limited and not every solution is successful. Even though the problem is not immediately resolved, the group problem-solving pattern serves as a useful guide through the problem-solving process.

Key Takeaway

Group problem solving can be an orderly process when it is broken down into seven specific stages.

- Think of a problem encountered in the past by a group of which you are a member. How did the group solve the problem? How satisfactory was the solution? Discuss your results with your classmates.

- Consider again the problem you described in Exercise 1. In view of the seven-step framework, which steps did the group utilize? Would following the full seven-step framework have been helpful? Discuss your opinion with a classmate.

- Research one business that you would like to know more about and see if you can learn about how they communicate in groups and teams. Compare your results with those of classmates.

- Think of a decision you will be making some time in the near future. Apply the cost-benefit analysis framework to your decision. Do you find this method helpful? Discuss your results with classmates.

Adler, R. (1996). Communicating at work: Principles and practices for business and the professions . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Business Communication for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Student Problem Solving Analysis by Step John Dewey Reviewed from Learning Style

This research aims to describe the student’s mathematical problem solving based on John Dewey’s step viewed by learning style. The subjects are 2 students with a visual learning style, 2 students with auditory learning style, and a student with kinaesthetic learning. The data was collected through a questionnaire of learning style, the test of mathematics problem solving, interview, and documentation. Then it was analyzed used Milles and Huberman model’s data analyzed technique consist of data reduction, data display, and conclusion (verification). This research shows that: (1) the visual subject confronted the problem by reading the question silently in several times, the subject can’t define the problem correctly, can’t found the right solution so that calculating and the answer is not correct, and can’t test consequences (looking back), (2) the auditory subject confronted the problem with reading the question in several times loudly, the subject can define the problem correctly, ...

Related Papers

AKSIOMA: Jurnal Program Studi Pendidikan Matematika

Setiawan edi Wibowo

This research aims to describe the mathematical problem-solving abilities of students with visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles in solving sequence and series questions based on IDEAL problem-solving steps. In this study, the research method used is qualitative. Grouping students based on their learning style through a student learning style questionnaire, namely visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles. Furthermore, data collection was carried out, namely holding a written test with sequences and series material. Then a problem-solving analysis was carried out from the answer data and interviews with the research subjects obtained. Data collection techniques used include Questionnaires, Tests, and Interviews. Meanwhile, in this study, the triangulation technique used is time triangulation. The results of the analysis and discussion show that students with a visual learning style have good abilities in solving mathematical problems. Students with a vimal learni...

Sembodro Ulum

The problem posing ability is making new questions and answers from previous information. Post-solution is modifing a condition of problem solved to submit a new problem. Learning styles in this research is in the form of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. This descriptive research examines the ability of students to post problem solutions based on differences in learning style involving 10 visual’s students, 12 auditory’s students, 9 kinesthetic’s students. Analysis of data in this research is the data reduction, data presentation, and drawing conclusions. Test material of the test is cubes. The results of the study show that ability problems of student with visual learning styles in the form of problems that can be solved is shown clear information, changing, varying, restating, and grouping in accordance with information about previous questions, direct and indirect answers are arranged in detail, language structure questions in the form of assignment and conditional propositions...

The Normal Lights

Rene Belecina

The study aimed to determine and describe the cognitive processes and learning styles of 12 eight graders in performing problem-solving tasks. The cognitive processes of students with different learning styles were studied in terms of the cognitive behaviors they manifested as they were given problem-solving tasks. These cognitive processes were understanding the tasks, specializing, generalizing, conjecturing, justifying, and looking back. Forty-one of the original 75 students from two sections of a government-owned secondary school in Quezon City were classified as active, reflective, sequential, and global, based on learning styles as revealed by the Felder and Soloman’s Index of Learning Styles Questionnaire. Consequently, three students from each learning style were randomly chosen as participants of the study. The three phases of the study involved audio taping the students while doing the problem-solving activities and interviewing them afterwards, coding all the transcribe...

Journal of Physics: Conference Series

Laila Fitriana

Problem solving is essential in mathematics teaching and learning. Mathematical problem solving as finding a way around difficulty and solution to a problem that is unknown. Learning style can be used by students in processing information and can help students in learning. Kolb’s learning style characteristic examined include converger, diverger, accommodator and assimilator. The purpose of this study is to describe about mathematical problem solving based on Kolb learning style. This study used descriptive qualitative method. The subject of the study consisted 4 students of National Senior High School Pekalongan which selected using purposive sampling. The research instruments were questionnaire and problem solving task. Data validity used method triangulation. Data analyses were done through data collection, data reduction, data presentation and conclusion. The results show that students with converger and accomodator learning style are better than diverger and assimilator learnin...

Advances in Mathematics: Scientific Journal

Lia Kurniawati

Asking question is an expression of the thought process. Question arises when someone gets new knowledge that is not in accordance with previous knowledge, through the thought process arises the question to get complete information so that the new knowledge he has becomes more meaningful. This study aims to evamine and analyze the ability of students in problem posing based on their learning style. The method carried out in this study was a quasi-experiment on 80 high-school students. The results showed that there is significant difference for the achievement of mathematical problem posing abilities based on visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles, contrary there is no significant difference in the improvement mathematical problem posing skills based on visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles

American Journal of Educational Research

Elvis Napitupulu

AJHSSR Journal

This research aims to analyze the impact of students" different mathematics problem-solving ability using the problem-solving method, and the relationship between the ability and students" learning styles and initial mathematical abilities. This research is conducted in SMA Negeri 1 Waisala Maluku. The sample comprises 67 tenth-grade students divided into three classes determined by the multi-stage random sampling technique. The method used in this research is pseudo-experiment. To collect relevant data, several instruments are used. They are (1) initial mathematical ability, (2) mathematical problem-solving ability, and (3) auditory, kinesthetic, and visual learning styles. The methods used are problem-solving and expository. Based on the research findings, (1) After their initial mathematical abilities are controlled, the mathematical problem-solving abilities of students taught using a problem-solving method are higher than that of students taught using an expository one; (2) After their initial mathematical abilities are controlled, the mathematical problem-solving abilities of students with an auditory learning are higher than that of students with a kinesthetic learning style; (3) After their initial mathematical abilities are controlled, the mathematical problem-solving abilities of students with an auditory learning are lower than that of students with a visual learning style; (4)After their initial mathematical abilities are controlled, the mathematical problem-solving abilities of students with a kinesthetic learning are lower than that of students with a visual learning style; and (5)After the students" initial mathematical abilities are controlled, there are an impact of the interaction between learning methods with learning styles and students" mathematical problem-solving abilities.

Ansari Saleh Ahmar

Mathematical problem posing plays an important role in mathematics curriculum, since it encompasses the core of mathematics activities, among other things, with students’ activities to construct their own problems as the preliminary step to actual problem solving steps. This study aims at revealing the profile of students’ mathematical problem posing based on their cognitive styles in order to know and understand the learning of mathematics students. As a result of this study, students who have the cognitive style ‘field independent’ (FI) are able to propose a solvable mathematical problem and load new data, and also pose problems categorized as high-quality mathematical problems. Students who have the cognitive style of ‘field dependent’ (FD) are generally limited to solvable mathematical problems that do not contain new data, and mathematical problems of a moderate level. In this study, it is seen how student’s work mathematical problem posing using their cognitive style, resulting in a breakthrough in the process of learning to use students’ cognitive styles so as to increase the quality of learning outcomes.

Silas Sudarman

This study aims to analyze and determine the effect of learning strategies (The differences between Problem Based Learning and Direct Instruction) and cognitive style on mathematical problems solving learning outcomes. This study used a quasi-experimental research design (nonequivalent control group designs) The research subjects were students from state elementary school of V grade in Gading I Surabaya, east java. The totals of elementary school population in east Surabaya were 141 elementary schools. The selected schools are the schools which have some parallel classes, therefore the circumstances are relatively similar. Four classes are selected, they were from SDN Gading 1 state elementary school. These schools were randomly chosen to implement different learning strategies, they are implementing problem-based learning and hands-on learning. The data collection techniques were mathematical problems solving learning pre-tests and post-test, Group embedded figures test (GEFT) for cognitive style, assessment performance for learning achievement. Data analysis techniques in this study use ANOVA technique (analysis of variance) two lines. The results of this study showed that (1) there is a difference in learning achievement between the students' groups who are taught by PBL and direct learning; (2) there are differences in achieving learning outcomes toward students' group and different cognitive styles; (3) there are significant interactions between the use of learning strategies and cognitive style on learning outcomes.

RELATED PAPERS

Boletin Del Instituto De Investigaciones Bibliograficas

Mary Ellen Waithe

SOSIO DIALEKTIKA

Anna yulia hartati

Francesco Ciardiello

Addis Adera Gebru

Elisa Blanco

Psychopharmacology bulletin

badari birur

Health Promotion International

hassan alzain

Jurnal Kesehatan Mahardika

Citra Setyo Dwi Andhini, S.Kep., Ners., M.Kep.

Maria Wurzinger

Sasmita Nayak , Nilanjan Sahu

Environmental Technology

Journal of Academic Research in Medicine

Dr. Halil CAN

American Heart Journal

Sadollah Abedini

Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC

Shakil Ahmad Anjum

Jorge Franco Armaza Deza

Hermann Schumacher

Hyperfine Interactions

J.varma J.varma

Pikir Wisnu Wijayanto

Eva Riveline

Frontiers in Genetics

Pollack Periodica

Etelka Szendroi

hjjhgj kjghtrg

Edward Elgar Publishing eBooks

Mariolina Eliantonio

La Trama de la Comunicación

Silvana Comba

International journal of logistics

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The 5 Steps in Problem Analysis

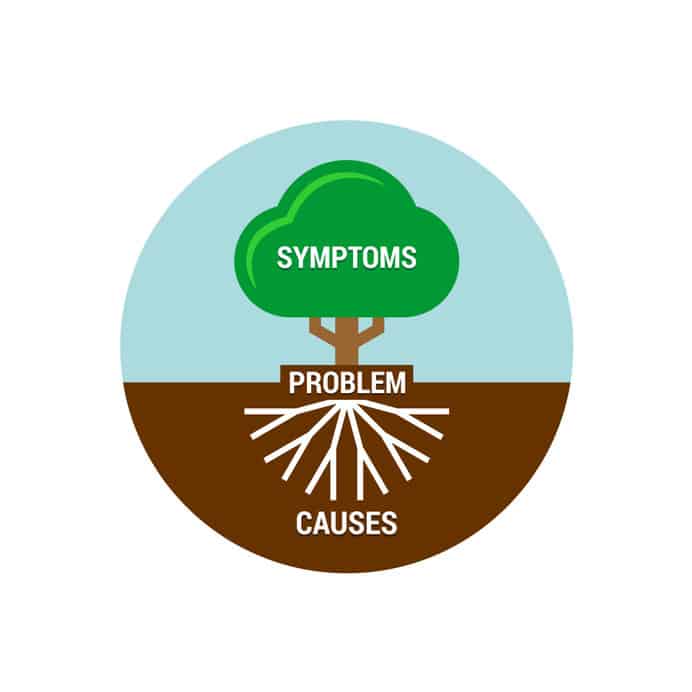

One technique that is extremely useful to gain a better understanding of the problems before determining a solution is problem analysis .

Problem analysis is the process of understanding real-world problems and user’s needs and proposing solutions to meet those needs. The goal of problem analysis is to gain a better understanding of the problem being solved before developing a solution.

There are five useful steps that can be taken to gain a better understanding of the problem before developing a solution.

- Gain agreement on the problem definition

- Understand the root-causes – the problem behind the problem

- Identify the stakeholders and the users

- Define the solution boundary

- Identify the constraints to be imposed on the solution

Table of Contents

Gain agreement on the problem definition.

The first step is to gain agreement on the definition of the problem to be solved. One of the simplest ways to gain agreement is to simply write the problem down and see whether everyone agrees.

Business Problem Statement Template

A helpful and standardised format to write the problem definition is as follows:

- The problem of – Describe the problem

- Affects – Identify stakeholders affected by the problem

- The results of which – Describe the impact of this problem on stakeholders and business activity

- Benefits of – Indicate the proposed solution and list a few key benefits

Example Business Problem Statement

There are many problems statement examples that can be found in different business domains and during the discovery when the business analyst is conducting analysis. An example business problem statement is as follows:

The problem of having to manually maintain an accurate single source of truth for finance product data across the business, affects the finance department. The results of which has the impact of not having to have duplicate data, having to do workarounds and difficulty of maintaining finance product data across the business and key channels. A successful solution would have the benefit of providing a single source of truth for finance product data that can be used across the business and channels and provide an audit trail of changes, stewardship and maintain data standards and best practices.

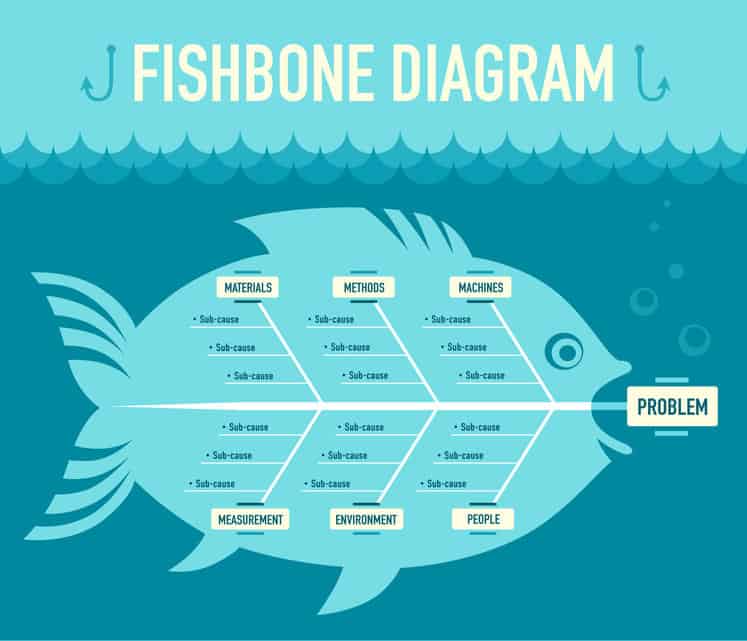

Understand the Root Causes Problem Behind the Problem

You can use a variety of techniques to gain an understanding of the real problem and its real causes. One such popular technique is root cause analysis, which is a systematic way of uncovering the root or underlying cause of an identified problem or a symptom of a problem.

Root cause analysis helps prevents the development of solutions that are focussed on symptoms alone .

To help identify the root cause, or the problem behind the problem, ask the people directly involved.

The primary goal of the technique is to determine the root cause of a defect or problem by repeating the question “Why?” . Each answer forms the basis of the next question. The “five” in the name derives from an anecdotal observation on the number of iterations needed to resolve the problem .

Identify the Stakeholders and the Users

Effectively solving any complex problem typically involves satisfying the needs of a diverse group of stakeholders. Stakeholders typically have varying perspectives on the problem and various needs that must be addressed by the solution. So, involving stakeholders will help you to determine the root causes to problems.

Define the Solution Boundary

Once the problem statement is agreed to and the users and stakeholders are identified, we can turn our attention of defining a solution that can be deployed to address the problem.

Identify the Constraints Imposed on Solution

We must consider the constraints that will be imposed on the solution. Each constraint has the potential to severely restrict our ability to deliver a solution as we envision it.

Some example solution constraints and considerations could be:-

- Economic – what financial or budgetary constraints are applicable?

- Environmental – are there environmental or regulatory constraints?

- Technical – are we restricted in our choice of technologies?

- Political – are there internal or external political issues that affect potential solutions?

Conclusion – Problem Analysis

Try the five useful steps for problem solving when your next trying to gain a better understanding of the problem domain on your business analysis project or need to do problem analysis in software engineering.

The problem statement format can be used in businesses and across industries.

Jerry Nicholas

Jerry continues to maintain the site to help aspiring and junior business analysts and taps into the network of experienced professionals to accelerate the professional development of all business analysts. He is a Principal Business Analyst who has over twenty years experience gained in a range of client sizes and sectors including investment banking, retail banking, retail, telecoms and public sector. Jerry has mentored and coached business analyst throughout his career. He is a member of British Computer Society (MBCS), International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA), Business Agility Institute, Project Management Institute (PMI), Disciplined Agile Consortium and Business Architecture Guild. He has contributed and is acknowledged in the book: Choose Your WoW - A Disciplined Agile Delivery Handbook for Optimising Your Way of Working (WoW).

Recent Posts

Introduction to Train the Trainer for a Business Analyst

No matter the industry, modern professionals need to continuously improve themselves and work on up skilling and re-skilling to maintain satisfactory success within their field. This is particularly...

CliftonStrengths for a Business Analyst | Be You

Today, the job of a business analyst is probably more challenging than ever. The already intricate landscape of modern business analysis has recently gone through various shifts, mainly due to the...

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 9 min read

The MoSCoW Method

Understanding project priorities.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

(Also Known As MoSCoW Prioritization and MoSCoW Analysis)

You probably use some form of prioritized To-Do List to manage your daily tasks. But what happens when you're heading up a project that has various stakeholders, each of whom has a different opinion about the importance of different requirements? How do you identify the priority of each task, and communicate that to team members, stakeholders and customers alike?

This is when it's useful to apply a prioritizing tool such as the MoSCoW method. This simple project-management approach helps you, your team, and your stakeholders agree which tasks are critical to a project's success. It also highlights those tasks that can be abandoned if deadlines or resources are threatened.

In this article, we'll examine how you can use the MoSCoW method to prioritize project tasks more efficiently, and ensure that everyone expects the same things.

What Is the MoSCoW Method?

The MoSCoW method was developed by Dai Clegg of Oracle® UK Consulting in the mid-1990s. It's a useful approach for sorting project tasks into critical and non-critical categories.

MoSCoW stands for:

- Must – "Must" requirements are essential to the project's success, and are non-negotiable. If these tasks are missing or incomplete, the project is deemed a failure.

- Should – "Should" items are critical, high-priority tasks that you should complete whenever possible. These are highly important, but can be delivered in a second phase of the project if absolutely necessary.

- Could – "Could" jobs are highly desirable but you can leave them out if there are time or resource constraints.

- Would (or "Won't") – These tasks are desirable (for example, "Would like to have…") but aren't included in this project. You can also use this category for the least critical activities.

The "o"s in MoSCoW are just there to make the acronym pronounceable.

Terms from Clegg, D. and Barker, R. (1994). ' CASE Method Fast-Track: A RAD Approach ,' Amsterdam: Addison-Wesley, 1994. Copyright © Pearson Education Limited. Reproduced with permission.

People often use the MoSCoW method in Agile Project Management . However, you can apply it to any type of project.

MoSCoW helps you manage the scope of your project so that it isn't overwhelmingly large. It is particularly useful when you're working with multiple stakeholders, because it helps everyone agree on what's critical and what is not. The four clearly labeled categories allow people to understand a task's priority easily, which eliminates confusion, misunderstanding, conflict, and disappointment.

For example, some project management tools sort tasks into "high-," "medium-," and "low-" priority categories. But members of the team might have different opinions about what each of these groupings means. And all too often, tasks are labeled "high" priority because everything seems important. This can put a strain on time and resources, and ultimately lead to the project failing.

Using the MoSCoW Method

Follow the steps below to get the most from the MoSCoW method. (This describes using MoSCoW in a conventional "waterfall" project, however the approach is similar with agile projects.)

Step 1: Organize Your Project

It's important that you and your team fully understand your objectives before starting the project.

Write a business case to define your project's goals, its scope and timeline, and exactly what you will deliver. You can also draw up a project charter to plan how you'll approach it.

Next, conduct a stakeholder analysis to identify key people who are involved in the project and to understand how its success will benefit each of them.

Step 2: Write out Your Task List

Once you understand your project's objectives, carry out a Gap Analysis to identify what needs to happen for you to meet your goals.

Step 3: Prioritize Your Task List

Next, work with your stakeholders to prioritize these tasks into the four MoSCoW categories: Must, Should, Could, and Would (or Won't). These conversations can often be "difficult," so brush up on your conflict resolution, group decision making and negotiating skills beforehand!

Rather than starting with all tasks in the Must category and then demoting some of them, it can be helpful to put every task in the Would category first, and then discuss why individual ones deserve to move up the list.

Step 4: Challenge the MoSCoW List

Once you've assigned tasks to the MoSCoW categories, critically challenge each classification.

Be particularly vigilant about which items make it to the Must list. Remember, it is reserved solely for tasks that would result in the project failing if they're not done.

Aim to keep the Must list below 60 percent of the team's available time and effort. The fewer items you have, the higher your chance of success.

Try to reach consensus with everyone in the group. If you can't, you then need to bring in a key decision-maker who has the final say.

Step 5: Communicate Deliverables

Your last step is to share the prioritized list with team members, key stakeholders and customers.

It's important that you communicate the reasons for each categorization, particularly with Must items. Encourage people to discuss any concerns until people fully understand the reasoning.