Recommended for you

Violence is never the answer, violence only causes more harm in our society and it needs to come to an end.

Today, if you turn on the television and watch the news, it is almost guaranteed you will see or hear about a violent act someone has committed, whether that be a mass shooting, police brutality, protests during a presidential candidate rally, or everyday violent occurrences. Violence has become a norm, and for some people, violent acts are encouraged. This can be an overwhelmingly scary thought; violence is not something that should even be thought of as a means of retaliation.

Violence, unfortunately, is a vicious cycle, and one that is hard to break. For example, abusive relationships are cycles where the victim becomes suffocated and smothered by the dominant. Similarly, once violence is learned, it is difficult to break that way of thinking. As human beings, violence isn’t natural, it is something that is taught; children, teenagers, and even young adults learn to become violent, they most likely aren’t born with a violent trait. We are influenced by the world around us, which ultimately reflects our society as whole. Today, the United States is one of the most violent developed countries in the world, meaning we have a large population full of violent people. As the millennial generation, we need to put an end to so much hatred in our society.

It is important for us to realize that violence is never an answer in any situation. If you try to fight fire with fire, you only get a bigger fire (or an inferno), and an inferno is practically impossible to put out. Nothing good ever comes out of violent acts. In the end, it is always a lose-lose situation. Take wars, for example. Each party involved in a war is going to have lives lost. Protests that become violent result in having protesters arrested, and others who may have been innocent end up getting injured or even sometimes killed.

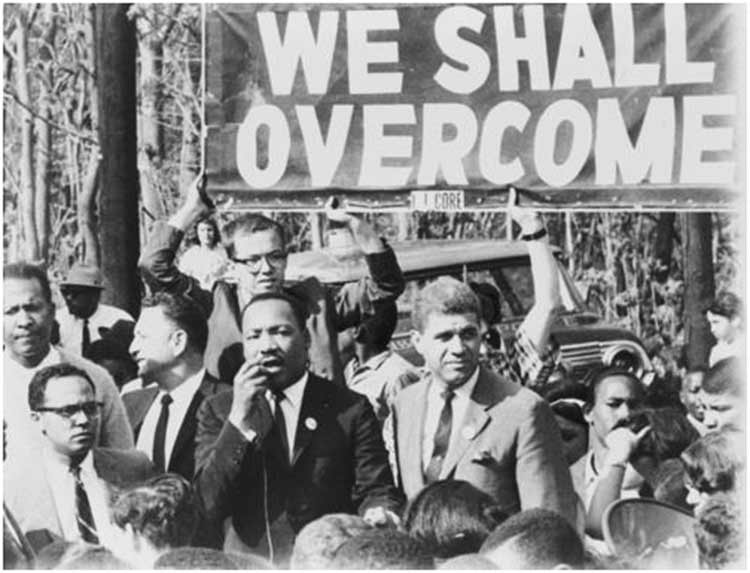

History has shown us that violent acts get the most innocent of people killed. It has also shown us that some of the greatest nonviolent acts send the biggest message and ultimately are what end up getting the most justice. For example, Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Gandhi are faces for nonviolence movements. Each of these individuals stood for what they believed in and let their peaceful actions speak the loudest. These activists were able to gain support because they peacefully protested and spoke out for what they believed in.

The more we continue to use violence as a means of retaliation in our society, the more violent our society becomes. We need to come together and realize the violent acts that we, as citizens, partake in are unacceptable and we must all stop allowing these types of violent acts to continue in our country. Human beings are meant to engage and protect one another while working together. The sooner we take a stand against violence, the more peaceful our society and world will become.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Grateful beyond words: a letter to my inspiration, i have never been so thankful to know you..

I can't say "thank you" enough to express how grateful I am for you coming into my life. You have made such a huge impact on my life. I would not be the person I am today without you and I know that you will keep inspiring me to become an even better version of myself.

You have taught me that you don't always have to strong. You are allowed to break down as long as you pick yourself back up and keep moving forward. When life had you at your worst moments, you allowed your friends to be there for you and to help you. You let them in and they helped pick you up. Even in your darkest hour you showed so much strength. I know that you don't believe in yourself as much as you should but you are unbelievably strong and capable of anything you set your mind to.

Your passion to make a difference in the world is unbelievable. You put your heart and soul into your endeavors and surpass any personal goal you could have set. Watching you do what you love and watching you make a difference in the lives of others is an incredible experience. The way your face lights up when you finally realize what you have accomplished is breathtaking and I hope that one day I can have just as much passion you have.

SEE MORE: A Letter To My Best Friend On Her Birthday

The love you have for your family is outstanding. Watching you interact with loved ones just makes me smile . You are so comfortable and you are yourself. I see the way you smile when you are around family and I wish I could see you smile like this everyday. You love with all your heart and this quality is something I wished I possessed.

You inspire me to be the best version of myself. I look up to you. I feel that more people should strive to have the strength and passion that you exemplify in everyday life.You may be stubborn at points but when you really need help you let others in, which shows strength in itself. I have never been more proud to know someone and to call someone my role model. You have taught me so many things and I want to thank you. Thank you for inspiring me in life. Thank you for making me want to be a better person.

Waitlisted for a College Class? Here's What to Do!

Dealing with the inevitable realities of college life..

Course registration at college can be a big hassle and is almost never talked about. Classes you want to take fill up before you get a chance to register. You might change your mind about a class you want to take and must struggle to find another class to fit in the same time period. You also have to make sure no classes clash by time. Like I said, it's a big hassle.

This semester, I was waitlisted for two classes. Most people in this situation, especially first years, freak out because they don't know what to do. Here is what you should do when this happens.

Don't freak out

This is a rule you should continue to follow no matter what you do in life, but is especially helpful in this situation.

Email the professor

Around this time, professors are getting flooded with requests from students wanting to get into full classes. This doesn't mean you shouldn't burden them with your email; it means they are expecting interested students to email them. Send a short, concise message telling them that you are interested in the class and ask if there would be any chance for you to get in.

Attend the first class

Often, the advice professors will give you when they reply to your email is to attend the first class. The first class isn't the most important class in terms of what will be taught. However, attending the first class means you are serious about taking the course and aren't going to give up on it.

Keep attending class

Every student is in the same position as you are. They registered for more classes than they want to take and are "shopping." For the first couple of weeks, you can drop or add classes as you please, which means that classes that were once full will have spaces. If you keep attending class and keep up with assignments, odds are that you will have priority. Professors give preference to people who need the class for a major and then from higher to lower class year (senior to freshman).

Have a backup plan

For two weeks, or until I find out whether I get into my waitlisted class, I will be attending more than the usual number of classes. This is so that if I don't get into my waitlisted class, I won't have a credit shortage and I won't have to fall back in my backup class. Chances are that enough people will drop the class, especially if it is very difficult like computer science, and you will have a chance. In popular classes like art and psychology, odds are you probably won't get in, so prepare for that.

Remember that everything works out at the end

Life is full of surprises. So what if you didn't get into the class you wanted? Your life obviously has something else in store for you. It's your job to make sure you make the best out of what you have.

Navigating the Talking Stage: 21 Essential Questions to Ask for Connection

It's mandatory to have these conversations..

Whether you met your new love interest online , through mutual friends, or another way entirely, you'll definitely want to know what you're getting into. I mean, really, what's the point in entering a relationship with someone if you don't know whether or not you're compatible on a very basic level?

Consider these 21 questions to ask in the talking stage when getting to know that new guy or girl you just started talking to:

1. What do you do for a living?

What someone does for a living can tell a lot about who they are and what they're interested in! Their career reveals a lot more about them than just where they spend their time to make some money.

2. What's your favorite color?

OK, I get it, this seems like something you would ask a Kindergarten class, but I feel like it's always good to know someone's favorite color . You could always send them that Snapchat featuring you in that cute shirt you have that just so happens to be in their favorite color!

3. Do you have any siblings?

This one is actually super important because it's totally true that people grow up with different roles and responsibilities based on where they fall in the order. You can tell a lot about someone just based on this seemingly simple question.

4. What's your favorite television show?

OK, maybe this isn't a super important question, but you have to know ASAP if you can quote Michael Scott or not. If not, he probably isn't the one. Sorry, girl.

5. When is your birthday?

You can then proceed to do the thing that every girl does without admitting it and see how compatible your zodiacs are.

6. What's your biggest goal in life?

If you're like me, you have big goals that you want to reach someday, and you want a man behind you who also has big goals and understands what it's like to chase after a dream. If his biggest goal is to see how quickly he can binge-watch " Grey's Anatomy " on Netflix , you may want to move on.

7. If you had three wishes granted to you by a genie, what would they be?

This is a go-to for an insight into their personality. Based on how they answer, you can tell if they're goofy, serious, or somewhere in between.

8. What's your favorite childhood memory?

For some, this may be a hard question if it involves a family member or friend who has since passed away . For others, it may revolve around a tradition that no longer happens. The answers to this question are almost endless!

9. If you could change one thing about your life, what would it be?

We all have parts of our lives and stories that we wish we could change. It's human nature to make mistakes. This question is a little bit more personal but can really build up the trust level.

10. Are you a cat or a dog person?

I mean, duh! If you're a dog person, and he is a cat person, it's not going to work out.

11. Do you believe in a religion or any sort of spiritual power?

Personally, I am a Christian, and as a result, I want to be with someone who shares those same values. I know some people will argue that this question is too much in the talking stage , but why go beyond the talking stage if your personal values will never line up?

12. If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would it be?

Even homebodies have a must visit place on their bucket list !

13. What is your ideal date night?

Hey, if you're going to go for it... go for it!

14. Who was/is your celebrity crush?

For me, it was hands-down Nick Jonas . This is always a fun question to ask!

15. What's a good way to cheer you up if you're having a bad day?

Let's be real, if you put a label on it, you're not going to see your significant other at their best 24/7.

16. Do you have any tattoos?

This can lead to some really good conversations, especially if they have a tattoo that has a lot of meaning to them!

17. Can you describe yourself in three words?

It's always interesting to see if how the person you're talking to views their personal traits lines ups with the vibes you're getting.

18. What makes you the most nervous in life?

This question can go multiple different directions, and it could also be a launching pad for other conversations.

19. What's the best gift you have ever received?

Admittedly, I have asked this question to friends as well, but it's neat to see what people value.

20. What do you do to relax/have fun?

Work hard, play hard, right?

21. What are your priorities at this phase of your life?

This is always interesting because no matter how compatible your personalities may be, if one of you wants to be serious and the other is looking for something casual, it's just not going to work.

Follow Swoon on Instagram .

Challah vs. Easter Bread: A Delicious Dilemma

Is there really such a difference in challah bread or easter bread.

Ever since I could remember, it was a treat to receive Easter Bread made by my grandmother. We would only have it once a year and the wait was excruciating. Now that my grandmother has gotten older, she has stopped baking a lot of her recipes that require a lot of hand usage--her traditional Italian baking means no machines. So for the past few years, I have missed enjoying my Easter Bread.

A few weeks ago, I was given a loaf of bread called Challah (pronounced like holla), and upon my first bite, I realized it tasted just like Easter Bread. It was so delicious that I just had to make some of my own, which I did.

The recipe is as follows:

Ingredients

2 tsp active dry or instant yeast 1 cup lukewarm water 4 to 4 1/2 cups all-purpose flour 1/2 cup white granulated sugar 2 tsp salt 2 large eggs 1 large egg yolk (reserve the white for the egg wash) 1/4 cup neutral-flavored vegetable oil

Instructions

- Combine yeast and a pinch of sugar in small bowl with the water and stir until you see a frothy layer across the top.

- Whisk together 4 cups of the flour, sugar, and salt in a large bowl.

- Make a well in the center of the flour and add in eggs, egg yolk, and oil. Whisk these together to form a slurry, pulling in a little flour from the sides of the bowl.

- Pour the yeast mixture over the egg slurry and mix until difficult to move.

- Turn out the dough onto a floured work surface and knead by hand for about 10 minutes. If the dough seems very sticky, add flour a teaspoon at a time until it feels tacky, but no longer like bubblegum. The dough has finished kneading when it is soft, smooth, and holds a ball-shape.

- Place the dough in an oiled bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and place somewhere warm. Let the dough rise 1 1/2 to 2 hours.

- Separate the dough into four pieces. Roll each piece of dough into a long rope roughly 1-inch thick and 16 inches long.

- Gather the ropes and squeeze them together at the very top. Braid the pieces in the pattern of over, under, and over again. Pinch the pieces together again at the bottom.

- Line a baking sheet with parchment and lift the loaf on top. Sprinkle the loaf with a little flour and drape it with a clean dishcloth. Place the pan somewhere warm and away from drafts and let it rise until puffed and pillowy, about an hour.

- Heat the oven to 350°F. Whisk the reserved egg white with a tablespoon of water and brush it all over the challah. Be sure to get in the cracks and down the sides of the loaf.

- Slide the challah on its baking sheet into the oven and bake for 30 to 35 minutes, rotating the pan halfway through cooking. The challah is done when it is deeply browned.

I kept wondering how these two breads could be so similar in taste. So I decided to look up a recipe for Easter Bread to make a comparison. The two are almost exactly the same! These recipes are similar because they come from religious backgrounds. The Jewish Challah bread is based on kosher dietary laws. The Christian Easter Bread comes from the Jewish tradition but was modified over time because they did not follow kosher dietary laws.

A recipe for Easter bread is as follows:

2 tsp active dry or instant yeast 2/3 cup milk 2 1/2 cups all-purpose flour 1/4 cup white granulated sugar 2 tbs butter 2 large eggs 2 tbs melted butter 1 tsp salt

- In a large bowl, combine 1 cup flour, sugar, salt, and yeast; stir well. Combine milk and butter in a small saucepan; heat until milk is warm and butter is softened but not melted.

- Gradually add the milk and butter to the flour mixture; stirring constantly. Add two eggs and 1/2 cup flour; beat well. Add the remaining flour, 1/2 cup at a time, stirring well after each addition. When the dough has pulled together, turn it out onto a lightly floured surface and knead until smooth and elastic, about 8 minutes.

- Lightly oil a large bowl, place the dough in the bowl and turn to coat with oil. Cover with a damp cloth and let rise in a warm place until doubled in volume, about 1 hour.

- Deflate the dough and turn it out onto a lightly floured surface. Divide the dough into two equal size rounds; cover and let rest for 10 minutes. Roll each round into a long roll about 36 inches long and 1 1/2 inches thick. Using the two long pieces of dough, form a loosely braided ring, leaving spaces for the five colored eggs. Seal the ends of the ring together and use your fingers to slide the eggs between the braids of dough.

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Place loaf on a buttered baking sheet and cover loosely with a damp towel. Place loaf in a warm place and let rise until doubled in bulk, about 45 minutes. Brush risen loaf with melted butter.

- Bake in the preheated oven until golden brown, about 30 minutes.

Both of these recipes are really easy to make. While you might need to have a day set aside for this activity, you can do things while the dough is rising or in the oven. After only a few hours, you have a delicious loaf of bread that you made from scratch, so the time and effort is really worth it!

Unlocking Lake People's Secrets: 15 Must-Knows!

There's no other place you'd rather be in the summer..

The people that spend their summers at the lake are a unique group of people.

Whether you grew up going to the lake , have only recently started going, or have only been once or twice, you know it takes a certain kind of person to be a lake person. To the long-time lake people, the lake holds a special place in your heart , no matter how dirty the water may look.

Every year when summer rolls back around, you can't wait to fire up the boat and get back out there. Here is a list of things you can probably identify with as a fellow lake-goer.

A bad day at the lake is still better than a good day not at the lake.

It's your place of escape, where you can leave everything else behind and just enjoy the beautiful summer day. No matter what kind of week you had, being able to come and relax without having to worry about anything else is the best therapy there is. After all, there's nothing better than a day of hanging out in the hot sun, telling old funny stories and listening to your favorite music.

You know the best beaches and coves to go to.

Whether you want to just hang out and float or go walk around on a beach, you know the best spots. These often have to be based on the people you're with, given that some "party coves" can get a little too crazy for little kids on board. I still have vivid memories from when I was six that scared me when I saw the things drunk girls would do for beads.

You have no patience for the guy who can't back his trailer into the water right.

When there's a long line of trucks waiting to dump their boats in the water, there's always that one clueless guy who can't get it right, and takes 5 attempts and holds up the line. No one likes that guy. One time my dad got so fed up with a guy who was taking too long that he actually got out of the car and asked this guy if he could just do it for him. So he got into the guy's car, threw it in reverse, and got it backed in on the first try. True story.

Doing the friendly wave to every boat you pass.

Similar to the "jeep wave," almost everyone waves to other boats passing by. It's just what you do, and is seen as a normal thing by everyone.

The cooler is always packed, mostly with beer.

Alcohol seems to be a big part of the lake experience, but other drinks are squeezed into the room remaining in the cooler for the kids, not to mention the wide assortment of chips and other foods in the snack bag.

Giving the idiot who goes 30 in a "No Wake Zone" a piece of your mind.

There's nothing worse than floating in the water, all settled in and minding your business, when some idiot barrels through. Now your anchor is loose, and you're left jostled by the waves when it was nice and perfectly still before. This annoyance is typically answered by someone yelling some choice words to them that are probably accompanied by a middle finger in the air.

You have no problem with peeing in the water.

It's the lake, and some social expectations are a little different here, if not lowered quite a bit. When you have to go, you just go, and it's no big deal to anyone because they do it too.

You know the frustration of getting your anchor stuck.

The number of anchors you go through as a boat owner is likely a number that can be counted on two hands. Every once in a while, it gets stuck on something on the bottom of the lake, and the only way to fix the problem is to cut the rope, and you have to replace it.

Watching in awe at the bigger, better boats that pass by.

If you're the typical lake-goer, you likely might have an average-sized boat that you're perfectly happy with. However, that doesn't mean you don't stop and stare at the fast boats that loudly speed by, or at the obnoxiously huge yachts that pass.

Knowing any swimsuit that you own with white in it is best left for the pool or the ocean.

You've learned this the hard way, coming back from a day in the water and seeing the flowers on your bathing suit that were once white, are now a nice brownish hue.

The momentary fear for your life as you get launched from the tube.

If the driver knows how to give you a good ride, or just wants to specifically throw you off, you know you're done when you're speeding up and heading straight for a big wave. Suddenly you're airborne, knowing you're about to completely wipe out, and you eat pure wake. Then you get back on and do it all again.

You're able to go to the restaurants by the water wearing minimal clothing.

One of the many nice things about the life at the lake is that everybody cares about everything a little less. Rolling up to the place wearing only your swimsuit, a cover-up, and flip flops, you fit right in. After a long day when you're sunburned, a little buzzed, and hungry, you're served without any hesitation.

Having unexpected problems with your boat.

Every once in a while you're hit with technical difficulties, no matter what type of watercraft you have. This is one of the most annoying setbacks when you're looking forward to just having a carefree day on the water, but it's bound to happen. This is just one of the joys that come along with being a boat owner.

Having a name for your boat unique to you and your life.

One of the many interesting things that make up the lake culture is the fact that many people name their boats. They can range from basic to funny, but they are unique to each and every owner, and often have interesting and clever meanings behind them.

There's no better place you'd rather be in the summer.

Summer is your all-time favorite season, mostly because it's spent at the lake. Whether you're floating in the cool water under the sun, or taking a boat ride as the sun sets, you don't have a care in the world at that moment . The people that don't understand have probably never experienced it, but it's what keeps you coming back every year.

Trending Topics

Songs About Being 17 Grey's Anatomy Quotes Vine Quotes 4 Leaf Clover Self Respect

Top Creators

1. Brittany Morgan, National Writer's Society 2. Radhi, SUNY Stony Brook 3. Kristen Haddox , Penn State University 4. Jennifer Kustanovich , SUNY Stony Brook 5. Clare Regelbrugge , University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Trending Stories

Why we should raise the minimum wage, the color of your shoelaces might tell someone you're a neo nazi, 21 superlatives for your formal, the top 14 nerdiest fandoms, the official rules of slugbug, best of politics and activism top 10 reasons my school rocks, 70 of the most referenced movies ever, 7 new year clichés: break free, embrace change, unleash inspiration: 15 relatable disney lyrics, the six most iconic pitbull lyrics of all time, subscribe to our newsletter, facebook comments.

Violence not a solution to problems

"Through violence you may murder a murderer, but you can't murder murder. Through violence you may murder a liar, but you can't establish truth. Through violence you may murder a hater, but you can't murder hate. Darkness cannot put out darkness. Only light can do that." — Martin Luther King, Jr.

Imagine for a minute someone saying this today. Imagine someone saying, “Through violence you may murder a terrorist, but you can’t destroy terrorism.” Imagine a politician proposing that we look beyond military might to find solutions.

Establishing truth is hard when we live in a society colored by the deceptions of violence. Our society has swallowed the bloody belief that violence solves problems. We wrap violence in acceptability and even admiration. Violence permeates our culture. It seeps into our entertainment. It flavors our national identity.

Violence is made righteous by our military. Our military promises that violence will solve problems. It teaches our youth that killing is commendable. This spills over into our social fabric as soldiers return shaped by violence and suffering from PTSD. Micah Xavier Johnson, the shooter in Dallas, and Galvin Long, the shooter in Baton Rouge, La., are recent reminders of this. Both served in the military.

Tearfully the parents of Johnson shared how the military changed him.

Long believed success came through violence. In his video, “Protesting, Oppression and How to Deal with Bullies,” he discusses the killings of African-American men by police officers. He believed an effective response required violence. Long stated, “One hundred percent of revolutions, of victims fighting their oppressors have been successful through fighting back, through bloodshed. Zero have been successful just over simply protesting.”

Both Johnson and Long were responding to the troubling violence against black lives by police. Militarization has spilled over into the way our police respond.

Many veterans are able to close the chapter on killing and return to society. Many others live with moral injury. Twenty-two or more veterans a day commit suicide.

Violence is good business. Every hour, U.S. taxpayers pay $3.42 million for just the cost of the Pentagon slush fund. Every hour, U.S. taxpayers pay $615,482 for the cost of military action against ISIS.

Lockheed Martin’s revenues rose 15.7 percent and shares rose 1.5 percent following news that the president was committing an additional 259 troops in Syria.

New York Times journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin points out that “some of the biggest gun makers in our nation are owned by private equity funds run by Wall Street titans.” Cerberus Capital Management, Sciens Capital Management and MidOcean Partners all profit from selling weapons of violence. From AK-47s to Hot Lips 10-round magazines, Wall Street firms have you covered.

Violence is popular politics. We will vote for America being great, great meaning militarily strong. Great does not mean compassionate. No candidate could win using King’s words “violence begets violence” as a slogan.

Donald Trump is ready to take out terrorist’s families. “When you get these terrorists, you have to take out their families.” Are we ready to elect someone willing to kill children? Have we forgotten that terrorist recruitment becomes easier when we are recklessly violent?

Will we ever wake up and realize that we have swallowed the bloody belief that violence solves problems? Will we ever wake-up and heed President Dwight Eisenhower’s warning to “guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex?” Will we ever understand that through violence you may murder a terrorist, but you can’t destroy terrorism?

"Nonviolence and Racial Justice"

Author: King, Martin Luther, Jr.

Date: February 6, 1957

Location: Chicago, Ill.

Genre: Published Article

Topic: Nonviolence

On 26 November 1956 King submitted an article on nonviolence to Christian Century , a liberal weekly religious magazine. In his cover letter to editor Harold Fey, King noted that “it has just been within the last few days that I have been able to take a little time off to do some much needed writing. If you find it possible to publish this article, please feel free to make any suggestions concerning the content.” He added that the journal’s “sympathetic treatment” of the bus boycott had been of “inestimable value.” 1 On 31 January Fey thanked King for the “excellent” article, and he featured it as the main essay in an issue devoted to race relations. 2 Drawing from his many speeches on the topic, King provides here a concise summary of his views regarding nonviolent resistance to segregation. 3

It is commonly observed that the crisis in race relations dominates the arena of American life. This crisis has been precipitated by two factors: the determined resistance of reactionary elements in the south to the Supreme Court’s momentous decision outlawing segregation in the public schools, and the radical change in the Negro’s evaluation of himself. While southern legislative halls ring with open defiance through “interposition” and “nullification,” while a modern version of the Ku Klux KIan has arisen in the form of “respectable” white citizens’ councils, a revolutionary change has taken place in the Negro’s conception of his own nature and destiny. Once he thought of himself as an inferior and patiently accepted injustice and exploitation. Those days are gone.

The first Negroes landed on the shores of this nation in 1619, one year ahead of the Pilgrim Fathers. They were brought here from Africa and, unlike the Pilgrims, they were brought against their will, as slaves. Throughout the era of slavery the Negro was treated in inhuman fashion. He was considered a thing to be used, not a person to be respected. He was merely a depersonalized cog in a vast plantation machine. The famous Dred Scott decision of 1857 well illustrates his status during slavery. In this decision the Supreme Court of the United States said, in substance, that the Negro is not a citizen of the United States; he is merely property subject to the dictates of his owner.

After his emancipation in 1863, the Negro still confronted oppression and inequality. It is true that for a time, while the army of occupation remained in the south and Reconstruction ruled, he had a brief period of eminence and political power. But he was quickly overwhelmed by the white majority. Then in 1896, through the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, a new kind of slavery came into being. In this decision the Supreme Court of the nation established the doctrine of “separate but equal” as the law of the land. Very soon it was discovered that the concrete result of this doctrine was strict enforcement of the “separate,” without the slightest intention to abide by the “equal.” So the Plessy doctrine ended up plunging the Negro into the abyss of exploitation where he experienced the bleakness of nagging injustice.

A Peace That Was No Peace

Living under these conditions, many Negroes lost faith in themselves. They came to feel that perhaps they were less than human. So long as the Negro maintained this subservient attitude and accepted the “place” assigned him, a sort of racial peace existed. But it was an uneasy peace in which the Negro was forced patiently to submit to insult, injustice and exploitation. It was a negative peace. True peace is not merely the absence of some negative force—tension, confusion or war; it is the presence of some positive force—justice, good will and brotherhood.

Then circumstances made it necessary for the Negro to travel more. From the rural plantation he migrated to the urban industrial community. His economic life began gradually to rise, his crippling illiteracy gradually to decline. A myriad of factors came together to cause the Negro to take a new look at himself. Individually and as a group, he began to re-evaluate himself. And so he came to feel that he was somebody. His religion revealed to him that God loves all his children and that the important thing about a man is “not his specificity but his fundamentum,” not the texture of his hair or the color of his skin but the quality of his soul.

This new self-respect and sense of dignity on the part of the Negro undermined the south’s negative peace, since the white man refused to accept the change. The tension we are witnessing in race relations today can be explained in part by this revolutionary change in the Negro’s evaluation of himself and his determination to struggle and sacrifice until the walls of segregation have been finally crushed by the battering rams of justice.

Quest for Freedom Everywhere

The determination of Negro Americans to win freedom from every form of oppression springs from the same profound longing for freedom that motivates oppressed peoples all over the world. The rhythmic beat of deep discontent in Africa and Asia is at bottom a quest for freedom and human dignity on the part of people who have long been victims of colonialism. The struggle for freedom on the part of oppressed people in general and of the American Negro in particular has developed slowly and is not going to end suddenly. Privileged groups rarely give up their privileges without strong resistance. But when oppressed people rise up against oppression there is no stopping point short of full freedom. Realism compels us to admit that the struggle will continue until freedom is a reality for all the oppressed peoples of the world.

Hence the basic question which confronts the world’s oppressed is: How is the struggle against the forces of injustice to be waged? There are two possible answers. One is resort to the all too prevalent method of physical violence and corroding hatred. The danger of this method is its futility. Violence solves no social problems; it merely creates new and more complicated ones. Through the vistas of time a voice still cries to every potential Peter, “Put up your sword!" 4 The shores of history are white with the bleached bones of nations and communities that failed to follow this command. If the American Negro and other victims of oppression succumb to the temptation of using violence in the struggle for justice, unborn generations will live in a desolate night of bitterness, and their chief legacy will be an endless reign of chaos.

Alternative to Violence

The alternative to violence is nonviolent resistance. This method was made famous in our generation by Mohandas K. Gandhi, who used it to free India from the domination of the British empire. Five points can be made concerning nonviolence as a method in bringing about better racial conditions.

First, this is not a method for cowards; it does resist. The nonviolent resister is just as strongly opposed to the evil against which he protests as is the person who uses violence. His method is passive or nonaggressive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent. But his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade the opponent that he is mistaken. This method is passive physically but strongly active spiritually; it is nonaggressive physically but dynamically aggressive spiritually.

A second point is that nonviolent resistance does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding. The nonviolent resister must often express his protest through noncooperation or boycotts, but he realizes that noncooperation and boycotts are not ends themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent. The end is redemption and reconciliation. The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness.

A third characteristic of this method is that the attack is directed against forces of evil rather than against persons who are caught in those forces. It is evil we are seeking to defeat, not the persons victimized by evil. Those of us who struggle against racial injustice must come to see that the basic tension is not between races. As I like to say to the people in Montgomery, Alabama: “The tension in this city is not between white people and Negro people. The tension is at bottom between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. And if there is a victory it will be a victory not merely for 50,000 Negroes, but a victory for justice and the forces of light. We are out to defeat injustice and not white persons who may happen to be injust.”

A fourth point that must be brought out concerning nonviolent resistance is that it avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. In struggling for human dignity the oppressed people of the world must not allow themselves to become bitter or indulge in hate campaigns. To retaliate with hate and bitterness would do nothing but intensify the hate in the world. Along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate. This can be done only by projecting the ethics of love to the center of our lives.

The Meaning of ‘Love’

In speaking of love at this point, we are not referring to some sentimental emotion. It would be nonsense to urge men to love their oppressors in an affectionate sense. “Love” in this connection means understanding good will. There are three words for love in the Greek New Testament. 5 First, there is eros . In Platonic philosophy eros meant the yearning of the soul for the realm of the divine. It has come now to mean a sort of aesthetic or romantic love. Second, there is philia . It meant intimate affectionateness between friends. Philia denotes a sort of reciprocal love: the person loves because he is loved. When we speak of loving those who oppose us we refer to neither eros nor philia ; we speak of a love which is expressed in the Greek word agape . Agape means nothing sentimental or basically affectionate; it means understanding, redeeming good will for all men, an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return. It is the love of God working in the lives of men. When we love on the agape level we love men not because we like them, not because their attitudes and ways appeal to us, but because God loves them. Here we rise to the position of loving the person who does the evil deed while hating the deed he does. 6

Finally, the method of nonviolence is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. It is this deep faith in the future that causes the nonviolent resister to accept suffering without retaliation. He knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. This belief that God is on the side of truth and justice comes down to us from the long tradition of our Christian faith. There is something at the very center of our faith which reminds us that Good Friday may reign for a day, but ultimately it must give way to the triumphant beat of the Easter drums. Evil may so shape events that Caesar will occupy a palace and Christ a cross, but one day that same Christ will rise up and split history into A.D. and B.C., so that even the life of Caesar must be dated by his name. So in Montgomery we can walk and never get weary, because we know that there will be a great camp meeting in the promised land of freedom and justice. 7

This, in brief, is the method of nonviolent resistance. It is a method that challenges all people struggling for justice and freedom. God grant that we wage the struggle with dignity and discipline. May all who suffer oppression in this world reject the self-defeating method of retaliatory violence and choose the method that seeks to redeem. Through using this method wisely and courageously we will emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of man’s inhumanity to man into the bright daybreak of freedom and justice.

1. For Christian Century articles supportive of the boycott see Harold Fey, “Negro Ministers Arrested,” 7 March 1956, pp. 294-295; “National Council Commends Montgomery Ministers,” 14 March 1956, p. 325; and “Segregation on Intrastate Buses Ruled Illegal,” 28 November 1956, p. 1379.

2. King’s draft of the article has not been located; the extent of Fey’s editing of it is therefore unknown. The previous September, Bayard Rustin had sent King a memorandum on the Christian duty to oppose segregation and urged him to send “something similar” to Christian Century (Rustin to King, 26 September 1956, in Papers 3:381-382).

3. In a 26 November 1957 letter to Dolores Gentile of King’s literary agency, Fey agreed to reassign the article’s copyright to allow King use of the material for his book on the bus boycott, Stride Toward Freedom . Much of the article’s substance, especially King’s discussion of the “Alternative to Violence” appeared in the book (see Stride , pp. 102-107). Note also the parallels between this article and King’s 27 June 1958 speech, “Nonviolence and Racial Justice,” delivered at the AFSC general conference in Cape May, New Jersey; it was published in the 26 July 1958 issue of Friends Journal .

4. John 18:11.

5. While the Greek language has three words for love, eros does not appear in the Greek New Testament.

6. Cf. Fosdick, On Being Fit to Live With: Sermons on Post-war Christianity (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1946), pp. 16-17.

7. In a similar discussion in Stride Toward Freedom , King included an additional element of nonviolence: “The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it. He does not seek to dodge jail. . . . Suffering, the nonviolent resister realizes, has tremendous educational and transforming possibilities” (p. 103).

Source: Christian Century 74 (6 February 1957): 165-167.

© Copyright Information

- Our Mission

- Our Sponsors

- Editorial Independence

- Write for The Crime Report

- Center on Media, Crime & Justice at John Jay College

- Journalists’ Conferences

- John Jay Prizes/Awards

- Stories from Our Network

- TCR Special Reports

- Research & Analysis

- Crime and Justice News

- At the Crossroads

- Domestic Violence

- Juvenile Justice

- Case Studies and Year-End Reports

- Media Studies

- Subscriber Account

Reducing Violence: Why ‘Simple’ Solutions Won’t Work

“Libraries, parks, rec centers, pools, free internet — those are all crime prevention activities and resources,” Caterina Roman, Ph.D., a professor of criminal justice at Temple University, told the New York Times last year.

Over the course of her career in academia and at the nonprofit Urban Institute, Prof. Roman has taken a broad view of violence and how to prevent it. Among other topics, she has investigated reentry programs, community justice partnerships, and the social networks of at-risk youth.

I talked to her by phone in February, not long after she had published an op-ed in the Philadelphia Inquirer calling for deeper investments in evidence-based gun violence prevention programs. Much of our conversation was devoted to focused deterrence, an approach to reducing gun violence that emerged in Boston in the 1990s and has been broadly disseminated by the National Network for Safe Communities , under the leadership of John Jay College professor David Kennedy .

Focused deterrence begins with a recognition that most of the violence in a given community is perpetrated by a small group of individuals. It seeks to target these individuals with offers of assistance, providing them with the job training, drug treatment, and other services they might need to avoid future offending.

If they do not cease their violent behavior, the focused deterrence model encourages the justice system to use all of the levers at its disposal–including arrest, prosecution and incarceration–to halt the violence. The use of focused deterrence strategies has been associated with local reductions in homicides, according to a number of evaluations.

In addition to focused deterrence, my conversation with Roman touched on gaps in our collective knowledge base, particularly the need for more information about effective crime prevention. The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

GREG BERMAN: How concerned are you about the spike in homicides we have seen over the past year? Do you think that the increase is something that we need to be worried about?

CATERINA ROMAN: I think we really need to be concerned about it. I think we’ve reached some kind of a tipping point. When you look at the reasons that people generally offer for any major spike in violence, all of them come into play with COVID. You have a little bit of everything. You have so many people buying guns. You have more hurt people who will hurt people. You have disinvestment that has been exacerbated. You have governments that aren’t funding parks, rec centers, summer jobs. You don’t have in-person religious services. You don’t have outreach workers on the streets or the typical social services. And then you have compounded stress.

All of these things are coming to a head together. There’s no place to go. Young people don’t have the access to pro-social jobs that will keep them busy and put them in contact with potential mentors.

BERMAN: Recent writing about the increase in violence seems to fall into two categories: an effort to score political points or a search for simple, silver-bullet answers to what’s going on.

ROMAN: I talk to my students a lot about the media. I’ve studied fear of crime, and I often ask, “Where does that fear come from?” Some of it is based in reality, but most of it is not. Having had many conversations with journalists over the years, I know that journalists often like to focus on just one thing to hang their stories on. Some of this comes from journalism itself, which requires stories to have a hook. It is also true that policymakers tend to want quicker fixes and easier answers. If you hang your hat on one cause, you have a straight line to a solution. In reality, it’s just not that simple.

BERMAN: You talk about the structural forces that lead to violence, including inequality and racism. The investments that we need to make to address these kinds of problems are probably generational. But we also have a need to move right now in response to an immediate crisis.

How would you advise a mayor or some other political actor who wanted to make a difference? How should we balance long-term investments with short-term strategies to quell violence?

ROMAN: I think policymakers and politicians should be direct and transparent with regard to longer-term investments. Given that the world knows that poverty has some relationship to crime and that disadvantage has some relationship to crime, it would be great if policymakers and politicians would just be open and say, “We are optimistic that we can make longer term change, and we’re going to do it by investing in neighborhood infrastructure. We’re going to do this, we’re going to tell you where the money’s going, and we’re going to measure the incremental change over time.”

I recognize that people want a quick fix. I’m not going to tell you that I believe that X policing solution or Y law enforcement solution is an answer. But I do think that police departments have the resources to do data-driven work that can be useful in communities. Where are the hot spots? How long have they been hot? What makes them different from other areas? What have we learned from both our successes and our failures in addressing hot spots from five years ago?

This is where I would advocate for practitioner-academic partnerships, because we know even the best police departments with the most data aren’t necessarily applying it in a larger, theory-based way. By creating these partnerships, we can ensure that policing will be used for smart strategies and reduce the likelihood that we’re sending police out on calls that have nothing to do with violence.

BERMAN: One of the problems in New York at the moment is a decline in clearance rates for homicides. Do you have some thoughts about what police should be doing to improve this?

ROMAN: There’s very little research out there on how to improve clearance rates. It is a huge gap in our knowledge. There’s a whole gamut of programs that are trying to achieve community-level change, whether it’s a focused deterrence/pulling levers model or Cure Violence or something else. I would advocate for researchers who have studied these models to go back and look at whether clearance rates were differentially affected in the treatment versus control neighborhoods. That’s relatively easy to do.

Maybe where there’s less violence on the street and less fear of crime, clearance rates go up.

BERMAN: You mentioned focused deterrence policing strategy. I’m curious to hear how you are thinking about focused deterrence these days and what we can say about its effectiveness as an intervention.

ROMAN: I’ve evaluated focused deterrence in Washington, D.C., in its first sort of iteration right after Operation Ceasefire in Boston. And I think the big issue for me about its effectiveness is that we’re only looking at the outcomes related to police data and changes in violence at the aggregate level. We’re not asking who benefits from the intervention and who is burdened. We’re only focused on the data we have at hand. This tends to be what evaluators do. It’s easy to get arrest data, so that’s what we measure. And so we only know from the majority of evaluations of focused deterrence that it reduced violence at the aggregate level.

We just know that we got the end result of reduction in violence. But what got us there? [John Jay professor] David Kennedy’s theory of change is that the threat of this very focused deterrence led to general deterrence. But we have no research that shows us that that is true. Yet everybody who advocates for focused deterrence is saying that it is an evidence-based program, that it’s working, and this is what we should do. I don’t know if that’s true.

BERMAN: So, if you were going to sponsor research into focused deterrence going forward, what would that look like?

ROMAN: Any intervention that expects a community-level reduction in violence has to have enough research dollars behind it to fund a comprehensive survey to track individual-level behavior change. You want to be interviewing those who are targeted in the initiative, and following up with them, and then also interviewing potential high-risk individuals in the community. This won’t be cheap. You’re at a million dollars right there. But that’s where I believe we have to go. If we want answers, we need to be able to conduct the kind of studies that are going to let us measure what is really happening at the community level.

BERMAN: You talk about people advocating for more focused deterrence. Recently, I’ve seen a number of calls for deeper investment in Cure Violence. Do you think that the evidence merits this push?

ROMAN: I think you’re asking the question in the wrong way. I think for every intervention we need to be asking who benefits and who is burdened. If you frame the question that way, I would have to think long and hard about who is burdened by Cure Violence. What are the unintended consequences of using credible messengers to go into the community and be pro-social mentors and caseworkers?

I don’t think there is an obvious burden to funding Cure Violence as it’s intended to be implemented, whereas there are so many things that could go wrong with focused deterrence, given its complex implementation structure. You can reduce violence but harm people.

BERMAN: You are advancing a kind of “do no harm” argument on behalf of Cure Violence. But do we know that it actually does what it says it does, in terms of reducing shootings?

ROMAN: I’m not sure. It’s supposed to be increasing legitimacy by telling the community to be collectively accountable and bringing up the moral voice of the community. But I also think you have to ask whether focused deterrence works in the long run. Is focused deterrence successful at reducing violence if once everyone knows focused deterrence is going away, they start shooting again? Please answer that for me.

BERMAN: I don’t want us to get locked into a focused deterrence versus Cure Violence conversation, because I don’t think that dynamic is helpful.

ROMAN: I wasn’t arguing for one versus the other. I am using those two models as an example of investment versus policing, surveillance, and deterrence. It does not have to be focused deterrence. It does not have to be Cure Violence. I think instead of Cure Violence, you could put money into victim services to make sure that every single person that’s a victim of violent crime has everything they could possibly need. Victim services are basically nonexistent in most urban communities.

BERMAN: Are there other programs out there that you feel are interesting, whether or not they’ve been evaluated with any degree of rigor?

ROMAN: Do you know about the Chelsea Hub ? This is a model where community agencies work collaboratively with the police, probation, school, and victim services. Everyone is meeting weekly. Let’s say I am a victim service agency and in walks someone who witnessed a shooting and that individual seems like they are in a crisis moment. That victim service agency would ask that person, “Would you be willing for me to present your case to a group of service providers to talk about how we could strategize about what you might need holistically?”

So the Hub is a method to provide holistic services to people who are in some type of crisis. It could be a domestic violence event. It could be after a hit-and-run incident. It doesn’t have to be violent crime, necessarily. Philadelphia is testing the model now through Temple med school. It’s voluntary for the individual. It is a positive, full-investment, collaborative model that cuts across systems so you can get to the complexity of the issues and offer an array of useful services and gain individuals’ trust. There hasn’t been a long-term evaluation of it, but it’s a very promising model. The GRYD model in Los Angeles is also worth checking out. I think they’ve had some impact evaluation work done that is pretty strong.

BERMAN: Let ’s talk about some of the articles you have written. A few years ago, you wrote about gang research and how to get people to leave gangs . What did you learn ?

ROMAN: The point of that article was to look across three very large studies to identify the kinds of pushes and pulls that get somebody out of the gang. A “pull” is pro-social. It is anything from “my significant other doesn’t want me involved in that anymore,” to “my grandmother says she’s not going to let me come home if I’m still hanging out with them.” A pull is some pro-social opportunity, like a job, that is getting me out of the gang. A push tends to be more negative. A push can be: they were victimized, or they were incarcerated, or they have gotten tired of being roughed up by the police. But it could also be they just realized that the gang wasn’t what they wanted.

BERMAN: You have also looked at fear of crime in Washington D.C. Tell me about that research .

ROMAN: That piece came from my interest in social capital and collective efficacy.

BERMAN: How would you define collective efficacy?

ROMAN: Collective efficacy is the activation of social ties and informal social control among neighbors. So we ask people, “How likely are your neighbors to help out another neighbor in need?” Or, “If a group of teens is hanging out on the street corner, being rowdy, how likely are your neighbors to do something about it?” We aggregate information from questions like these to measure collective efficacy.

In the survey that I did in the northeast section of Washington, D.C, we looked at how collective efficacy was related to fear of crime as measured by people reporting that they were not going to go walk outside because they were worried about crime. At first, what we found jibed with the literature—older people and women tend to be more fearful. As we added different variables to the model, we looked at the interaction of collective efficacy on Black residents versus white residents.

What we found was that there was an increase of fear when collective efficacy was higher among Black respondents. We did not find any significant effect among non-Black respondents. We posited that, as collective efficacy increased, Black residents in those neighborhoods were talking more and transmitting more information about violent crime and what was actually happening in the neighborhood. And that relaying of information in the neighborhood increased fear. So higher collective efficacy meant more fear for Black respondents.

BERMAN: What do you think is the biggest misconception that policymakers have about crime prevention?

ROMAN: The truth is that we know very little about what works because we don’t test prevention. We don’t test prevention mechanisms like Pre-K. In Philadelphia, where I live, we have 4,000 more kids in Pre-K each year over the last couple of years. We don’t know if that’s going to reduce violence, because we’re not testing that.

So when a policymaker goes to the evidence base, they’re looking at the interventions that were more likely to be evaluated. As we have discussed, policing programs are relatively straightforward to evaluate: You get crime data, that’s really simple. What we’re not doing is funding the kinds of survey research that would give us evidence that legitimacy is increased, that moral cynicism is reduced, that more people are integrated with their neighborhoods. We have no idea how to increase collective efficacy. That’s why we can’t solve the violence problem. So, going back to your question, I think what’s not understood is that we don’t have good evidence on prevention, because we don’t research prevention.

BERMAN: If you were going to make a reading recommendation to an audience that is interested in community-based violence, is there a single book or single study that you would point to?

ROMAN: If someone is interested in this topic, they should spend a week with an outreach worker. They should spend a week in a victim services agency. They should be inside the neighborhood. You’re not going to learn anything from a book. If you want to change a neighborhood, be inside it, and see if you can feel it.

But to answer your question about a book, I would tell you to check out the Aspen Institute’s roundtable on community change, which was turned into a book edited by Karen Fulbright-Anderson and Patricia Auspos . Dennis Rosenbaum has a great chapter in there on promoting safe and healthy neighborhoods. I’d also encourage people to read Wes Skogan , a criminologist who studied policing and community change.

Greg Berman is Distinguished Fellow of Practice at The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation. He previously served as the executive director of the Center for Court Innovation for 18 years. His most recent book is Start Here: A Road Map to Reducing Mass Incarceration (The New Press).

Views expressed are the participants’ own and not necessarily those of The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation.

Previous At the Crossroads interviews:

March 27 Conversation with Jeffrey Butts

COVID-19 and the ‘New Normal’ in Criminal Justice

April 8 Conversation with Marlon Peterson

A Prison Abolitionist’s Plea: We Need a Better Solution for ‘Egregious Harm’

May 13 Conversation with Richard Aborn

Coping With the ‘Crisis of Violence’

June 10. Conversation with Shani Buggs

‘Invest in Communities’: A Gun Violence Researcher Finds Reason for Hope

Related Posts

Silent strength: my time as a prisoner’s wife turned advocate, reclaimed identity: keith jesperson’s sixth murder, mississippi regularly fails to investigate rampant abuses by sheriff’s and their departments, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Reporting Awards

- Events/Fellowships

- Send Us Tips

- Republish Our Stories

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Violence v Non Violence: which is more effective as a driver of change?

By Duncan Green

Oxfam’s Ed Cairns explores the evidence and experience on violence v non violence as a way of bringing about social change

One of the perennial themes of this blog is the idea that crises may provide an opportunity for progressive change. True. But I’ve always been nervous that such hopes can forget that most conflicts cause far more human misery than any good that may come.

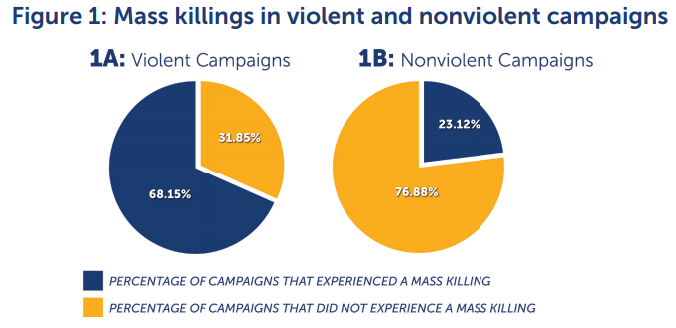

This is something that Duncan and I have (non-violently) tussled about over the years. So imagine my delight when I saw a recent report that seems to back up my caution. The International Center on Nonviolent Conflict’s paper on Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings looked at 308 popular uprisings up to 2013. It found that “nonviolent uprisings are almost three times less likely than violent rebellions to encounter mass killings,” which faced such brutal repression nearly 68% of the time. The authors, Erica Chenoweth and Evan Perkoski , think this is because violent campaigns threaten leaders and security forces alike, encouraging them to “ hold on to power at any cost, even ordering or carrying out a mass atrocity in an attempt to survive .”

There is a positive lesson here, that nonviolence works – at least better than violence. This builds on Chenoweth’s earlier study, which suggested that between 2000 and 2006, 70% of nonviolent campaigns succeeded, five times the success rate for violent ones . Looking back over the 20 th century, she found that non-violent campaigns succeeded 53% of the time, compared with 26% for violent resistance.

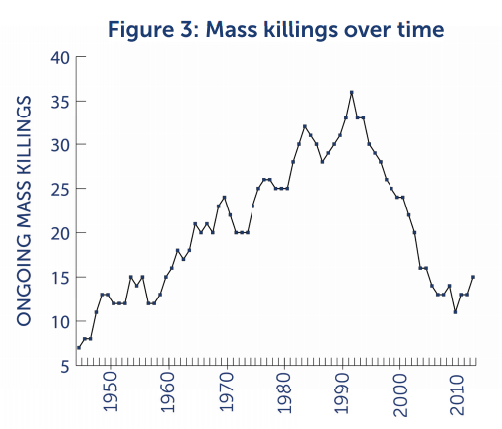

Again, there is a positive lesson – though it’d be interesting to know the figures since 2006, when the world appears to have become more repressive and violent. 2017 was the 12 th year, according to the US-based Freedom House, “of decline in global freedom [as] seventy-one countries suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties. ” As the Uppsala Conflict Data Program shows, these years of pressure on rights have coincided with sharp rises in conflicts since the start of this decade . And according to the 2018 Global Peace Index, just out this month, “ peacefulness has declined year on year for eight of the last ten years.” This seems to suggest that in our violent and challenging decade, nonviolent campaigns have found it tough in many countries too.

Tragically, this may breed a climate of desperation. In another recent article, Robin Luckham wrote that “the temptations of violence… are even stronger when authoritarian regimes violently crush non-violent protests…The turn from non-violent to violent resistance can easily open the way for more ruthless and better armed groups to step into the political spaces initially opened up by peaceful protests, as in Syria and Libya.”

This brings us perhaps to a less positive lesson – that living under tyrannies may be less worse than violent campaigns to change them. Chenoweth and Perkoski argue that “popular uprisings are not all alike. Some, like those in Libya (2011) and eventually Syria (2011), are predominantly violent, wherein the opposition chooses to take up arms to challenge the status quo. Others, like Tunisia (2010), Egypt (2011), and Burkina Faso (2014), eschew violence altogether.”

“Choose to take up arms”? That’s a harsh way to describe the situation at least some armed groups have faced. We should never forget that state repression often drives uprisings to become more violent. But looking at the historical evidence in these articles – and at almost every conflict now – it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that armed resistance is seldom successful, often counterproductive, and therefore rarely justifiable.

This begs one final question which Chenoweth and Perkoski can help with. Few would now argue that foreign countries should intervene to change regimes. But the UK Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee is conducting an enquiry on the prospect of military interventions for a different purpose – to stop mass killings. Its chair, Thomas Tugendhat, suggested that ‘ The Cost of Doing Nothing ’ in Syria had been thousands and thousands of lives.

I’ve never been convinced of that case in Syria, though the world’s failure to stop the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia in the 1990s was among the most shameful events of our times. But Chenoweth and Perkoski highlight the danger of any kind of foreign intervention. The likelihood of mass killings increases, they conclude, both “when foreign states provide material aid to dissidents… [and] to the governments the movements oppose.” In the first case, that’s because foreign support to oppositions encourages states to perceive them “as an existential threat.”

We shouldn’t conclude that military action will never ever be justified to prevent mass killings. But we know more reasons for caution than we once did. Every foreign action needs to be carried out with the best possible knowledge of its consequences.

That’s a harder thing to do than in the 1990s, when this debate first forced its way onto humanitarian agendas. According to a UN/World Bank study , there were eight armed groups in an average civil war in the 1950s. By 2010, there were fourteen. In Syria in 2014, there were more than a thousand. While more local parties are fighting within borders, regional powers – like Saudi Arabia and Iran – as well as Russia and the US are more willing to contemplate war, in what Robert Malley of Crisis Group calls the world’s “ growing militarization of foreign policy .” It is in this dangerous world that the risks of military action are higher than when the ideas of “humanitarian intervention” and Responsibility to Protect were developed.

I’ve never believed that pacifism is an adequate answer to a world of atrocities that – in truly exceptional cases – call out for an armed response. But there’s an awful lot of evidence for caution – and reason to give peace a chance.

Violence Doesn’t Work (Most of the Time)

People have long assumed that violence is necessary for political change. Rulers never cede power voluntarily, the argument goes, so progressives have no choice but to contemplate the use of force to bring about a better world, mindful of the trade-off between a small amount of violence now and acceptance of an unjust status quo indefinitely. Terrorists invoke this trade-off to justify what would otherwise be wanton murder. Even their most vociferous condemners concede that terrorism, though highly immoral, is often efficacious.

Of course, Mohandas Gandhi, and later Martin Luther King Jr., argued the opposite—that violence, in addition to being morally heinous, is tactically counterproductive. Violent movements attract thugs and firebrands who enjoy the mayhem. Violent tactics provide a pretext for retaliation by the enemy and alienate third parties who might otherwise support the movement.

So how effective is violence? Political scientists have recently tried tallying the successes and failures of violent and nonviolent movements. The evidence is piling up that Gandhi was right—at least on average. In separate analyses, Audrey Cronin and Max Abrahms have shown that terrorist movements almost always fizzle out without achieving any of their strategic aims. Just think of the failed independence movements in Puerto Rico, Ulster, Quebec, Basque Country, Kurdistan, and Tamil Eelam. The success rate of terrorist movements is, at best, in the single digits.

In their recent book, Why Civil Resistance Works , Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan found that about three-quarters of nonviolent movements get some or all of what they want, compared with only about a third of the violent ones. The Arab Spring bears this out: consider the more or less nonviolent movements that ousted the leaders of Egypt, Tunisia, and Yemen (together with the violent one needed in Libya). Even more encouraging, the success rate of nonviolent protest movements has steadily climbed since the 1940s, while that of violent movements has fallen since the 1980s.

Next idea: Fix Law Schools

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Harvard stargazer whose humanity still burns bright

Taiwan sees warning signs in weakening congressional support for Ukraine

How dating sites automate racism

In her book, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict,” Harvard Professor Erica Chenoweth explains why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people.

Photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy

Nonviolent resistance proves potent weapon

Michelle Nicholasen

Weatherhead Center Communications

Erica Chenoweth discovers it is more successful in effecting change than violent campaigns

Recent research suggests that nonviolent civil resistance is far more successful in creating broad-based change than violent campaigns are, a somewhat surprising finding with a story behind it.

When Erica Chenoweth started her predoctoral fellowship at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in 2006, she believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. She had studied terrorism, civil war, and major revolutions — Russian, French, Algerian, and American — and suspected that only violent force had achieved major social and political change. But then a workshop led her to consider proving that violent resistance was more successful than the nonviolent kind. Since the question had never been addressed systematically, she and colleague Maria J. Stephan began a research project.

For the next two years, Chenoweth and Stephan collected data on all violent and nonviolent campaigns from 1900 to 2006 that resulted in the overthrow of a government or in territorial liberation. They created a data set of 323 mass actions. Chenoweth analyzed nearly 160 variables related to success criteria, participant categories, state capacity, and more. The results turned her earlier paradigm on its head — in the aggregate, nonviolent civil resistance was far more effective in producing change.

The Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA) sat down with Chenoweth, a new faculty associate who returned to the Harvard Kennedy School this year as professor of public policy, and asked her to explain her findings and share her goals for future research. Chenoweth is also the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: In your co-authored book, “ Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict ,” you explain clearly why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people — in part it’s because there’s a much lower barrier to participation compared with picking up a weapon. Based on the cases you have studied, what are the key elements necessary for a successful nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: I think it really boils down to four different things. The first is a large and diverse participation that’s sustained.

The second thing is that [the movement] needs to elicit loyalty shifts among security forces in particular, but also other elites. Security forces are important because they ultimately are the agents of repression, and their actions largely decide how violent the confrontation with — and reaction to — the nonviolent campaign is going to be in the end. But there are other security elites, economic and business elites, state media. There are lots of different pillars that support the status quo, and if they can be disrupted or coerced into noncooperation, then that’s a decisive factor.

The third thing is that the campaigns need to be able to have more than just protests; there needs to be a lot of variation in the methods they use.

The fourth thing is that when campaigns are repressed — which is basically inevitable for those calling for major changes — they don’t either descend into chaos or opt for using violence themselves. If campaigns allow their repression to throw the movement into total disarray or they use it as a pretext to militarize their campaign, then they’re essentially co-signing what the regime wants — for the resisters to play on its own playing field. And they’re probably going to get totally crushed.

In 2006, Erica Chenoweth believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. Then she was challenged to prove it.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

WCFIA: Is there any way to resist or protest without making yourself more vulnerable?

CHENOWETH: People have done things like bang pots and pans or go on electricity strikes or something otherwise disruptive that imposes costs on the regime even while people aren’t outside. Staying inside for an extended period equates to a general strike. Even limited strikes are very effective. There were limited and general strikes in Tunisia and Egypt during their uprisings and they were critical.

WCFIA: A general strike seems like a personally costly way to protest, especially if you just stop working or stop buying things. Why are they effective?

CHENOWETH: This is why preparation is so essential. Where campaigns have used strikes or economic noncooperation successfully, they’ve often spent months preparing by stockpiling food, coming up with strike funds, or finding ways to engage in community mutual aid while the strike is underway. One good example of that comes from South Africa. The anti-apartheid movement organized a total boycott of white businesses, which meant that black community members were still going to work and getting a paycheck from white businesses but were not buying their products. Several months of that and the white business elites were in total crisis. They demanded that the apartheid government do something to alleviate the economic strain. With the rise of the reformist Frederik Willem de Klerk within the ruling party, South African leader P.W. Botha resigned. De Klerk was installed as president in 1989, leading to negotiations with the African National Congress [ANC] and then to free elections, where the ANC won overwhelmingly. The reason I bring the case up is because organizers in the black townships had to prepare for the long term by making sure that there were plenty of food and necessities internally to get people by, and that there were provisions for things like Christmas gifts and holidays.

WCFIA: How important is the overall number of participants in a nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: One of the things that isn’t in our book, but that I analyzed later and presented in a TEDx Boulder talk in 2013 , is that a surprisingly small proportion of the population guarantees a successful campaign: just 3.5 percent. That sounds like a really small number, but in absolute terms it’s really an impressive number of people. In the U.S., it would be around 11.5 million people today. Could you imagine if 11.5 million people — that’s about three times the size of the 2017 Women’s March — were doing something like mass noncooperation in a sustained way for nine to 18 months? Things would be totally different in this country.

“Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed.” Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: Is there anything about our current time that dictates the need for a change in tactics?

CHENOWETH: Mobilizing without a long-term strategy or plan seems to be happening a lot right now, and that’s not what’s worked in the past. However, there’s nothing about the age we’re in that undermines the basic principles of success. I don’t think that the factors that influence success or failure are fundamentally different. Part of the reason I say that is because they’re basically the same things we observed when Gandhi was organizing in India as we do today. There are just some characteristics of our age that complicate things a bit.

WCFIA: You make the surprising claim that even when they fail, civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms than violent campaigns do. How does that work?

CHENOWETH: The finding is that civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms and changes that bring about democratization compared with violent campaigns. Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed. This is because even though they “failed” in the short term, the nonviolent campaigns tended to empower moderates or reformers within the ruling elites who gradually began to initiate changes and liberalize the polity.