Political Science

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you to recognize and to follow writing standards in political science. The first step toward accomplishing this goal is to develop a basic understanding of political science and the kind of work political scientists do.

Defining politics and political science

Political scientist Harold Laswell said it best: at its most basic level, politics is the struggle of “who gets what, when, how.” This struggle may be as modest as competing interest groups fighting over control of a small municipal budget or as overwhelming as a military stand-off between international superpowers. Political scientists study such struggles, both small and large, in an effort to develop general principles or theories about the way the world of politics works. Think about the title of your course or re-read the course description in your syllabus. You’ll find that your course covers a particular sector of the large world of “politics” and brings with it a set of topics, issues, and approaches to information that may be helpful to consider as you begin a writing assignment. The diverse structure of political science reflects the diverse kinds of problems the discipline attempts to analyze and explain. In fact, political science includes at least eight major sub-fields:

- American politics examines political behavior and institutions in the United States.

- Comparative politics analyzes and compares political systems within and across different geographic regions.

- International relations investigates relations among nation states and the activities of international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and NATO, as well as international actors such as terrorists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and multi-national corporations (MNCs).

- Political theory analyzes fundamental political concepts such as power and democracy and foundational questions, like “How should the individual and the state relate?”

- Political methodology deals with the ways that political scientists ask and investigate questions.

- Public policy examines the process by which governments make public decisions.

- Public administration studies the ways that government policies are implemented.

- Public law focuses on the role of law and courts in the political process.

What is scientific about political science?

Investigating relationships.

Although political scientists are prone to debate and disagreement, the majority view the discipline as a genuine science. As a result, political scientists generally strive to emulate the objectivity as well as the conceptual and methodological rigor typically associated with the so-called “hard” sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics). They see themselves as engaged in revealing the relationships underlying political events and conditions. Based on these revelations, they attempt to state general principles about the way the world of politics works. Given these aims, it is important for political scientists’ writing to be conceptually precise, free from bias, and well-substantiated by empirical evidence. Knowing that political scientists value objectivity may help you in making decisions about how to write your paper and what to put in it.

Political theory is an important exception to this empirical approach. You can learn more about writing for political theory classes in the section “Writing in Political Theory” below.

Building theories

Since theory-building serves as the cornerstone of the discipline, it may be useful to see how it works. You may be wrestling with theories or proposing your own as you write your paper. Consider how political scientists have arrived at the theories you are reading and discussing in your course. Most political scientists adhere to a simple model of scientific inquiry when building theories. The key to building precise and persuasive theories is to develop and test hypotheses. Hypotheses are statements that researchers construct for the purpose of testing whether or not a certain relationship exists between two phenomena. To see how political scientists use hypotheses, and to imagine how you might use a hypothesis to develop a thesis for your paper, consider the following example. Suppose that we want to know whether presidential elections are affected by economic conditions. We could formulate this question into the following hypothesis:

“When the national unemployment rate is greater than 7 percent at the time of the election, presidential incumbents are not reelected.”

Collecting data

In the research model designed to test this hypothesis, the dependent variable (the phenomenon that is affected by other variables) would be the reelection of incumbent presidents; the independent variable (the phenomenon that may have some effect on the dependent variable) would be the national unemployment rate. You could test the relationship between the independent and dependent variables by collecting data on unemployment rates and the reelection of incumbent presidents and comparing the two sets of information. If you found that in every instance that the national unemployment rate was greater than 7 percent at the time of a presidential election the incumbent lost, you would have significant support for our hypothesis.

However, research in political science seldom yields immediately conclusive results. In this case, for example, although in most recent presidential elections our hypothesis holds true, President Franklin Roosevelt was reelected in 1936 despite the fact that the national unemployment rate was 17%. To explain this important exception and to make certain that other factors besides high unemployment rates were not primarily responsible for the defeat of incumbent presidents in other election years, you would need to do further research. So you can see how political scientists use the scientific method to build ever more precise and persuasive theories and how you might begin to think about the topics that interest you as you write your paper.

Clear, consistent, objective writing

Since political scientists construct and assess theories in accordance with the principles of the scientific method, writing in the field conveys the rigor, objectivity, and logical consistency that characterize this method. Thus political scientists avoid the use of impressionistic or metaphorical language, or language which appeals primarily to our senses, emotions, or moral beliefs. In other words, rather than persuade you with the elegance of their prose or the moral virtue of their beliefs, political scientists persuade through their command of the facts and their ability to relate those facts to theories that can withstand the test of empirical investigation. In writing of this sort, clarity and concision are at a premium. To achieve such clarity and concision, political scientists precisely define any terms or concepts that are important to the arguments that they make. This precision often requires that they “operationalize” key terms or concepts. “Operationalizing” simply means that important—but possibly vague or abstract—concepts like “justice” are defined in ways that allow them to be measured or tested through scientific investigation.

Fortunately, you will generally not be expected to devise or operationalize key concepts entirely on your own. In most cases, your professor or the authors of assigned readings will already have defined and/or operationalized concepts that are important to your research. And in the event that someone hasn’t already come up with precisely the definition you need, other political scientists will in all likelihood have written enough on the topic that you’re investigating to give you some clear guidance on how to proceed. For this reason, it is always a good idea to explore what research has already been done on your topic before you begin to construct your own argument. See our handout on making an academic argument .

Example of an operationalized term

To give you an example of the kind of rigor and objectivity political scientists aim for in their writing, let’s examine how someone might operationalize a term. Reading through this example should clarify the level of analysis and precision that you will be expected to employ in your writing. Here’s how you might define key concepts in a way that allows us to measure them.

We are all familiar with the term “democracy.” If you were asked to define this term, you might make a statement like the following:

“Democracy is government by the people.”

You would, of course, be correct—democracy is government by the people. But, in order to evaluate whether or not a particular government is fully democratic or is more or less democratic when compared with other governments, we would need to have more precise criteria with which to measure or assess democracy. For example, here are some criteria that political scientists have suggested are indicators of democracy:

- Freedom to form and join organizations

- Freedom of expression

- Right to vote

- Eligibility for public office

- Right of political leaders to compete for support

- Right of political leaders to compete for votes

- Alternative sources of information

- Free and fair elections

- Institutions for making government policies depend on votes and other expressions of preference

If we adopt these nine criteria, we now have a definition that will allow us to measure democracy empirically. Thus, if you want to determine whether Brazil is more democratic than Sweden, you can evaluate each country in terms of the degree to which it fulfills the above criteria.

What counts as good writing in political science?

While rigor, clarity, and concision will be valued in any piece of writing in political science, knowing the kind of writing task you’ve been assigned will help you to write a good paper. Two of the most common kinds of writing assignments in political science are the research paper and the theory paper.

Writing political science research papers

Your instructors use research paper assignments as a means of assessing your ability to understand a complex problem in the field, to develop a perspective on this problem, and to make a persuasive argument in favor of your perspective. In order for you to successfully meet this challenge, your research paper should include the following components:

- An introduction

- A problem statement

- A discussion of methodology

- A literature review

- A description and evaluation of your research findings

- A summary of your findings

Here’s a brief description of each component.

In the introduction of your research paper, you need to give the reader some basic background information on your topic that suggests why the question you are investigating is interesting and important. You will also need to provide the reader with a statement of the research problem you are attempting to address and a basic outline of your paper as a whole. The problem statement presents not only the general research problem you will address but also the hypotheses that you will consider. In the methodology section, you will explain to the reader the research methods you used to investigate your research topic and to test the hypotheses that you have formulated. For example, did you conduct interviews, use statistical analysis, rely upon previous research studies, or some combination of all of these methodological approaches?

Before you can develop each of the above components of your research paper, you will need to conduct a literature review. A literature review involves reading and analyzing what other researchers have written on your topic before going on to do research of your own. There are some very pragmatic reasons for doing this work. First, as insightful as your ideas may be, someone else may have had similar ideas and have already done research to test them. By reading what they have written on your topic, you can ensure that you don’t repeat, but rather learn from, work that has already been done. Second, to demonstrate the soundness of your hypotheses and methodology, you will need to indicate how you have borrowed from and/or improved upon the ideas of others.

By referring to what other researchers have found on your topic, you will have established a frame of reference that enables the reader to understand the full significance of your research results. Thus, once you have conducted your literature review, you will be in a position to present your research findings. In presenting these findings, you will need to refer back to your original hypotheses and explain the manner and degree to which your results fit with what you anticipated you would find. If you see strong support for your argument or perhaps some unexpected results that your original hypotheses cannot account for, this section is the place to convey such important information to your reader. This is also the place to suggest further lines of research that will help refine, clarify inconsistencies with, or provide additional support for your hypotheses. Finally, in the summary section of your paper, reiterate the significance of your research and your research findings and speculate upon the path that future research efforts should take.

Writing in political theory

Political theory differs from other subfields in political science in that it deals primarily with historical and normative, rather than empirical, analysis. In other words, political theorists are less concerned with the scientific measurement of political phenomena than with understanding how important political ideas develop over time. And they are less concerned with evaluating how things are than in debating how they should be. A return to our democracy example will make these distinctions clearer and give you some clues about how to write well in political theory.

Earlier, we talked about how to define democracy empirically so that it can be measured and tested in accordance with scientific principles. Political theorists also define democracy, but they use a different standard of measurement. Their definitions of democracy reflect their interest in political ideals—for example, liberty, equality, and citizenship—rather than scientific measurement. So, when writing about democracy from the perspective of a political theorist, you may be asked to make an argument about the proper way to define citizenship in a democratic society. Should citizens of a democratic society be expected to engage in decision-making and administration of government, or should they be satisfied with casting votes every couple of years?

In order to substantiate your position on such questions, you will need to pay special attention to two interrelated components of your writing: (1) the logical consistency of your ideas and (2) the manner in which you use the arguments of other theorists to support your own. First, you need to make sure that your conclusion and all points leading up to it follow from your original premises or assumptions. If, for example, you argue that democracy is a system of government through which citizens develop their full capacities as human beings, then your notion of citizenship will somehow need to support this broad definition of democracy. A narrow view of citizenship based exclusively or primarily on voting probably will not do. Whatever you argue, however, you will need to be sure to demonstrate in your analysis that you have considered the arguments of other theorists who have written about these issues. In some cases, their arguments will provide support for your own; in others, they will raise criticisms and concerns that you will need to address if you are going to make a convincing case for your point of view.

Drafting your paper

If you have used material from outside sources in your paper, be sure to cite them appropriately in your paper. In political science, writers most often use the APA or Turabian (a version of the Chicago Manual of Style) style guides when formatting references. Check with your instructor if they have not specified a citation style in the assignment. For more information on constructing citations, see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial.

Although all assignments are different, the preceding outlines provide a clear and simple guide that should help you in writing papers in any sub-field of political science. If you find that you need more assistance than this short guide provides, refer to the list of additional resources below or make an appointment to see a tutor at the Writing Center.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Becker, Howard S. 2007. Writing for Social Scientists: How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book, or Article , 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cuba, Lee. 2002. A Short Guide to Writing About Social Science , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lasswell, Harold Dwight. 1936. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Scott, Gregory M., and Stephen M. Garrison. 1998. The Political Science Student Writer’s Manual , 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: What is Comparative Politics?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 135826

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define key concepts within the discipline of comparative politics.

- Understand the scope of comparative politics and its place within the discipline of political science.

Introduction

Have you ever read the news and wondered,

- “Why is this country at war with another country?” or

- “Why did that world leader say or do that?” or

- “Why doesn’t this country trade with that country?” or maybe, very simply,

- “Why can’t all these countries just get along?”

If you have, you’ve already begun asking a few of the many questions scholars within the field of comparative politics ask when practicing their craft. Many of the questions and concerns within the realm of comparative politics are centered on a wide spectrum of social, political, cultural and economic circumstances and outcomes, which provide students and scholars alike with robust and diverse opportunities for inquiry and discussion. The field of comparative politics is broad enough to enable provocative conversations about the nature of violence, the future of democracy, why some democracies fail, and why vast disparities in wealth are able to persist both globally and within certain countries. Whether a student watches or reads the news, or expresses any outward concern for global and current events, many of the problems and issues within comparative politics inevitably affect every single person on the planet.

So, what exactly is comparative politics? What differentiates comparative politics from other subfields within political science? What can be gained from studying comparative politics? The following sections introduce the field, outlook, and topics within comparative politics that will be further explored in this book.

When defining and describing the scope of comparative politics, it is useful to back up and recall the purpose of political science from a broad perspective. Political science is a field of social and scientific inquiry which seeks to advance knowledge of political institutions, behavior, activities, and outcomes using systematic and logical research methods in order to test and refine theories about how the political world operates. Since the field of political science is so broad, it has a number of subfields within it that enable students and scholars to focus on various phenomena from different analytical lenses and perspectives. Although there are many topics that can be addressed within political science, there are eight subfields that tend to garner the most attention; these include: (1) Comparative Politics, (2) American Politics, (3) International Relations (sometimes referred to as World Politics, International affairs, or International Studies), (4) Political Philosophy, (5) Research Methods and Models, (6) Political Economy, (7) Public Policy, and (8) Political Psychology. All of these subfields, to varying degrees, are able to leverage findings and approaches from a diversity of disciplines, including sociology, history, philosophy, psychology, anthropology, economics, and law. Given the vast scope of political science, and in order to understand where comparative politics fits within the discipline, it is useful to briefly consider these subfields side-by-side.

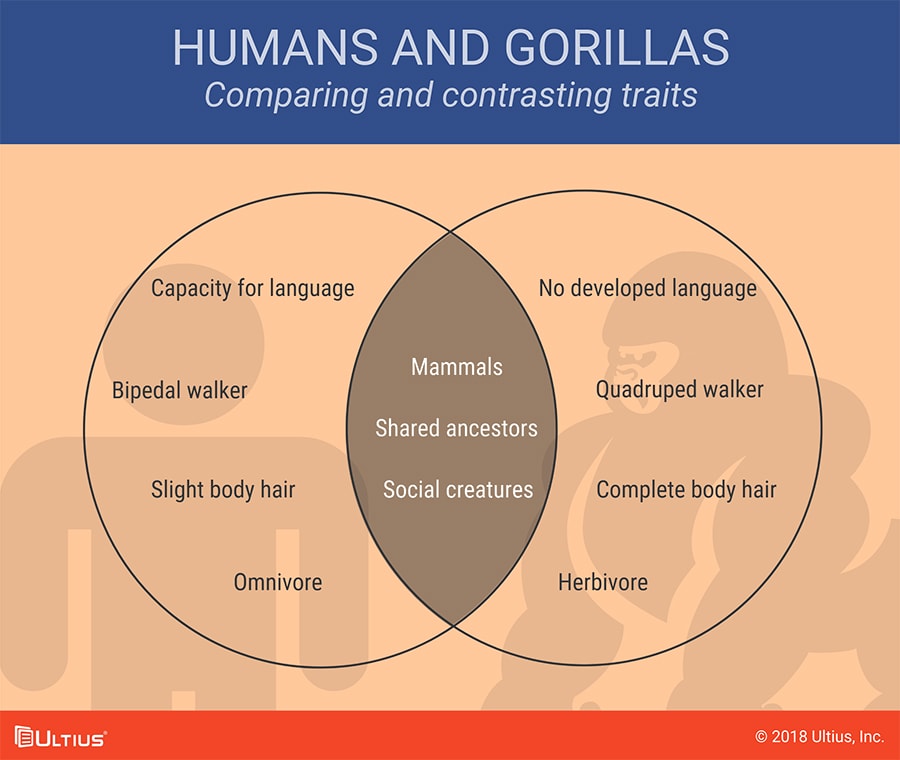

Comparative Politics

This subfield of study within political science seeks to advance understanding of political structures from around the world in an organized, methodological, and clear way. Scholars can, for instance, analyze countries, in part or in whole, in order to consider similarities and differences between and among countries. While the name of the field itself suggests a methodology of comparing and contrasting, there is ample room for debate over the best way to analyze political units side-by-side. In this chapter, we show different ways to prepare a comparison, whether one focuses on area studies, cross-national studies, or subnational studies. Comparative politics involves looking first within countries and then across designated countries (this contrasts with International Relations, which is described below, but entails looking primarily across countries, with less attention given to within country analysis). Further on, we discuss many of the themes for analysis, whether the scholar is focusing on “the state” or statehood, political institutions, democracy and democratization, or backsliding democracies, and so forth. After briefly considering the other subfields within political science, we will revisit the question of the ultimate definition and scope of comparative politics today.

American Politics

This subfield of political science focuses on political institutions and behaviors within the United States. Those interested in American politics will focus on questions like: What is the role of elections in American democracy? How do interest groups affect legislation in the U.S.? What is the role of public opinion and the media in the U.S., and what are the implications for democracy? What is the future of the two-party system? Do political parties delay important political action? Those who decide to specialize in American politics could find themselves a variety of career opportunities, spanning from teaching, journalism, working for government think-tanks, working for federal, state or local governmental institutions, or even running for office.

International Relations

Sometimes called world politics, international affairs or international studies, international relations is a subfield of political science which focuses on how countries and/or international organizations or bodies interact with each other. Those interested in international relations consider questions like: What causes war between states? How does international trade affect relationships between states? How do international bodies, like non-governmental organizations, work with various states? What is globalization and how does it affect peace and conflict? What is the best balance of power for the global system? Individuals interested in this field of political science may be looking for careers with teaching, non-governmental organizations, the United Nations, and governmental think-tanks focused on U.S. foreign policy.

Political Philosophy

Sometimes called political theory, political philosophy is a subfield of political science which reflects on the philosophical origins of politics, the state, government, fairness, equality, equity, authority and legitimacy. This field can consider themes in broad or narrow terms, considering the origins of political principles, as well as implications for these principles as they relate to issues of political identity, culture, the environment, ethics, distribution of wealth, as well as other societal phenomena. Those interested in political philosophy may ask questions like: Where did the concept of “the state” arise? What were the different ancient beliefs regarding the formation of states and cooperation within societies? How is power derived within systems, and what are the best theories to explain power dynamics? Individuals who are interested in political philosophy may find careers in teaching, research, journalism as well as consulting.

Research Methods and Models

Research methods and models can sometimes be considered a subfield of political science in itself, as it seeks to consider the best practices for analyzing themes within political science through discussion, testing and critical analysis of how research is constructed and implemented. This subfield is concerned with finding techniques for testing theories and hypotheses related to political science. An ongoing and heated debate often arises out of the proper or applicable usage of quantitative versus qualitative research designs, though each inevitably can be appropriate for various research scenarios.

Quantitative research centers on testing a theory or hypothesis, usually through mathematical and statistical means, using data from a large sample size. Quantitative research can be beneficial in situations where a scholar or student is looking to test the validity of a theory, or general statement, while looking at a large sample size of data that is diverse and representative of the subjects being studied. International Relations, American Politics, Public Policy and Comparative politics can, depending on the subject they are considering, find practical applicable for quantitative research methods. Someone interested in International Relations may want to test, for instance, the influence of global trade on conflict between states. For this, the sample size of the study may be 172 states engaged in international trade over a period of 10, 20, or even 50 years. Perhaps the theory being tested would be this: trade improves relations between states, making conflict unlikely. The person testing this would need to find ways to quantify conflict over time, to measure alongside, perhaps, trade volume between states. Overall, some of the methods for quantitative research may involve conducting surveys, conducting bi- or multivariate regression analysis (time-series, cross-sectional), or carrying out observations to test a hypothesis.

Qualitative research centers on exploring ideas and phenomena, potentially with the goal of consolidating information or developing evidence to form a theory or hypothesis to test. Qualitative research involves categorizing, summarizing and analyzing cases more thoroughly, and possibly individually, to gain greater understanding. Often, given the need for more description, qualitative research will have a small sample size, perhaps only comparing a couple states at a time, or even a state individually based on the theme of interest. Some of the methods for qualitative research involve conducting interviews, constructing literature reviews, or preparing an ethnography. Regardless of a quantitative or qualitative approach, topics of interest within the subfield of Research Methods and Models focuses on advancing discussions of best practices in research design and methodology, understanding causal relationships between events or outcomes, identifying best practices in quantitative and qualitative research methods, consideration of how to measure social, economic, cultural and political trends (focusing on validity and reliability), and reducing errors or poor output due to selection bias, omitted variable bias, and other factors related to poor research design. In many ways, this subfield is critical to almost all others within political science, and this book will spend a chapter looking closer at appropriate research methods and models to provide students with a greater understanding in order to test or develop theories within political science. For those interested in pursuing Research Methods and Models as a subfield, there are a number of careers open not only for its relevance to political science, but also to fields within mathematics, the nature of inquiry, statistics and so forth.

Political Economy

This subfield of political science considers various economic theories (like capitalism, socialism, communism, fascism), practices and outcomes either within a state, or among and between states in the global system. Those interested in political economy will become versed with the theories brought forth by Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Karl Marx, and Max Weber to gain greater understanding into economic systems and their outputs and affect on society. Political economy can be studied from the standpoints of a few other subfields in political science, for instance, comparative politics may consider political economy when comparing and contrasting states. International relations could consider International Political Economy, wherein scholars attempt to understand international economics in the context of different state systems. International Political Economy will consider questions relating to global inequalities, relationships between poor and wealthy countries, the role and effect of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or multinational corporations (MNCs) on international trade and finance. Those who are interested in political economy find careers as economists, or analysts for the stock market, as well as in teaching and research.

Public Policy

This subfield of political science explores political policies and outcomes, and focuses on the strength, legitimacy and effectiveness of political institutions within a state or society. Relevant areas of inquiry in this field include: How is the agenda for public policies set? Which public policies issues get the most attention, and why? How do we evaluate the effectiveness of a public policy? To what extent can public policy hurt or help democracy? Individuals interested in public policy can seek careers relating to almost any item of the U.S. political agenda (the healthcare system, social security, military affairs, welfare, education, etc.), go into teaching and research, or serve as public policy consultants for federal, state or local governmental organizations.

Political Psychology

This relatively new subfield within political science weds together principles, themes and research from both political science and psychology, in order to understand the potential psychological roots for political behavior. Is there a psychological reason some world leaders behave in a certain way? Is a leader’s behavior strategic and, consciously or not, rooted in some psychological basis? Can theories of cognitive and social processes explain various political outcomes in states and societies? Those interested in the psychological origins of political behavior could find interesting careers in teaching, research, and consulting.

All of these subfields within political science can utilize each other to develop greater understanding of political institutions and activities to advance the field. Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) provides a graphical representation of the subfields within political science, though it is important to point out that fields are not necessarily mutually exclusive. For instance, there are, at times, overlap between fields. Public policy can be analyzed through the lens of American Politics, but it can also be the key point of consideration for comparative politics or international relations. Similarly, political economy can refer simply to domestic affairs, or be applied across a few or many countries or states. Political psychology can likewise be applied for single state analysis or comparative or global studies. Most all of these fields will need some level of specialization in research methods or models to enable the systematic analysis of their subjects of interest. Without a research method and model, these subfields would not be able to advance knowledge in the field in a substantive way.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=214&height=169)

Given the overall spectrum of subfields available within the field of political science, let’s take a closer look at comparative politics, its origin, expanded definition, its uniqueness among the subfields, and the terminology frequently used by comparativists.

A Brief History and Expanded Definition

In considering the other subfields within political science, it may not seem like a complicated process to define comparative politics. Comparative politics, further explained, seems to be a field of study wherein scholars compare and contrast various political systems, institutions, characteristics and outcomes on one, a few, or a group of countries. In actuality, there has been ample debate over the ideal definition and scope of comparative politics. To consider comparative politics more thoroughly, it is helpful to consider its historical origins.

Most often, comparative politics is considered to have ancient origins, going back to at least Aristotle. Aristotle has sometimes been credited with being the “father” of political science, and attributed with being one of the first to use comparative methodologies for analyzing competing Greek city-states. The word politics derives from the Greek word, politikos , meaning “of, or relating to, the polis,” with polis being translated as city-state. Aristotle envisioned the study of politics to be one of the three major forms of science individuals could engage in. The first form of science, according to Aristotle, was contemplative science, and in modern terms, this refers closest to the studies of both physics and metaphysics, which he considered to be concerned with truth, and the pursuit of truth and knowledge for intrinsic purposes. The second form of science that Aristotle identified was practical science, which was the study of what is ideal for individuals and society. Aristotle felt the practical sciences were the areas of philosophy, mathematics and science. The final area of science Aristotle identified was productive science, which he envisioned as the making of important or beautiful objects. To Aristotle, political science fell within the realm of practical sciences, and was of critical concern (he identified political science as “the most authoritative science”) when discussing what is best for society. To Aristotle, political science must concern itself with what is “good” or “right” or “just” for society, as the lives of citizens are at stake given political structures and institutions.

It is not difficult to appreciate why Aristotle found political science, and comparative politics, so important given his overall beliefs on the function of politics within a society. In Aristotle’s time, the units-of-analysis were the city-states in Greece, which, if stable, enabled people to live productive and possibly happy lives; if unstable, it could not produce any positive externalities. For Aristotle, it was critical to find ways to compare and contrast the various city-states, how they operated, and what their outcomes for the people were. To this end, Aristotle looked at the constitutions for various city-states, to understand which had the ideal configurations for both the people and political outputs. A city-state could have one ruler, who, depending on how the government is run, is either a rightful king, or a tyrant running an authoritarian regime. Or, a city-state may have a few rulers, which, at best, could be an aristocracy, or at worst, an oligarchy where only the elite are included in decision-making and rewards. Finally, a city-state could have multiple rulers, balanced by a “middle” class which attempts to rule on behalf of the people’s interests. The “middle” group is not tremendously wealthy, nor woefully poor, but being in the “middle” they can understand the needs of society at large. While Aristotle considered democracy to have the possibility of being “deviant,” he also entertained the possibility that having more people involved in government may be a way to edge out corruption. In some ways, perhaps Aristotle was hoping for “cooler heads to prevail,” or that there would be a “wisdom” of the majority which would limit corruption. In any/either case, Aristotle spent a lot of time comparing and contrasting the virtuous and deviant political regime types in order to determine what is best for society.

The work of Aristotle influenced a number of thinkers to continue the scientific tradition of scientifically approaching problems in political science and comparative politics. If considering political science broadly, Aristotle influenced Niccolo Machiavelli (author of The Prince ), Charles Montesquieu, (author of The Spirit of the Laws ), Max Weber (sociologist and author of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism , 1905), to name a few.

If we consider the work of Gerardo Munck, we are currently in a period following the Second Scientific Revolution of 1989-2005. The current status of comparative politics is one where there is a greater reliance on methodology rather than theory, per se. In looking at Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), it can be observed that there are still variations in how significant scholars in the field define comparative politics, with some of these definitions leading to potentially different implications for research and inquiry.

Debate on the definition of comparative politics can arise in a few ways. One way would be this: Zahariadis (1997) argued that comparative politics needs to be a study of foreign countries. If this is true, does that mean someone who lives in a country, cannot study their own country and still call it comparative politics? If this is true, then was Aristotle’s study of city-states methodologically flawed since he occasionally lived in different city-states? Another area where comparativists disagree, which will be considered more in Chapter 2, is: what is the appropriate sample size for inquiry? Does the definition of comparative politics need to mandate a certain number of countries be studied at a time? When Alexis de Tocqueville wrote Democracy in America, 1835, was this study flawed because it was only considered the political lives of Americans? If we take Zahariadis’ definition, de Tocqueville did focus on a foreign country, but since it is only one country, does that mean it does not fall into the realm of comparative politics? Already, the two issues of whether one can originate or reside in a country that is being compared, as well as the appropriate sample size, is already in question. As will be described in Chapter 2, this textbook provides a necessary overview of the scope of methods and models for the comparative politics field for the purpose of greater understanding, focusing less on arguing about a definitive answer to questions still argued within the field of comparative politics.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

The Ultimate Guide to the AP Comparative Government and Politics Exam

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Planning to take the AP Comparative Government and Politics exam? Whether you took the course or self-studied, here’s everything you need to know about the exam, plus tons of free resources to help you get a great score.

The AP Comparative Government and Politics exam and course has been updated for the 2019-2020 school year, so pay special attention to these changes. You can read more about the changes in this AP Comparative Government updates document released by the College Board .

Note that this post is not about the AP U.S. Government and Politics exam , the more popular of the two “AP Government” exams. Be sure to double-check that you’re looking at the right post for the exam you’re taking.

When is the AP Comparative Government Exam?

On Thursday, May 14 at 8 am, the College Board will hold the 2020 AP Comparative Government Exam. For a comprehensive listing of all the AP exam times, check out our post 2020 AP Exam Schedule: Everything You Need to Know .

About the AP Comparative Government Exam

The AP Comparative Government and Politics exam focuses on six core countries: China, Great Britain, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, and Russia. According to the College Board , this exam measures your “ability to compare and contrast political regimes; electoral systems; federal structures; civil rights; and state responses to economic, social, and religious challenges over time.”

Throughout the AP Comparative course, you’ll learn five key skills, or disciplinary practices as they are called by the College Board, which will help you think and act like comparative political scientists. Possessing and demonstrating these skills is essential to getting a high score on the AP Comparative Government exam. The five key disciplinary practices are:

1. Concept Application: Applying political concepts and processes to real-life situations.

2. Country Comparison: Compare political concepts and processes to the course’s six core countries.

3. Data Analysis: Analyze and interpret quantitative data represented in a variety of mediums—such as tables, charts, graphs, maps, and infographics.

4. Source Analysis: Read, analyze, and interpret text-based sources.

5. Argumentation: Develop and defend an argument in the form of an essay.

In addition to acquiring these vital skills, students will explore five big ideas that serve as the foundation of the AP Comparative Government course, using them to make connections between concepts throughout the course. The five big ideas are:

1. Power and Authority: The political systems and regimes governing societies, who is given power and authority, how they use it, and how it produces different policy outcomes.

2. Legitimacy and Stability: The degree a government’s right to rule is accepted by the citizenry and how the legitimacy of a government translates to its ability to enact, implement, and enforce its policies.

3. Democratization: The process of adopting free and fair elections, extending civil liberties, and establishing the rule of law. How that process generally increases government transparency, improves citizen access, and influences policy making.

4. Internal/External Forces: How internal and external forces challenge and reinforce regimes.

5. Methods of Political Analysis: Collecting and using data to identify and describe patterns and trends in political behavior, along with using data and ideas from other disciplines when drawing conclusions.

AP Comparative Government Course Content

The AP Comparative Government course is divided into five units. Below is a suggested sequence of the units from the College Board, along with the percentage each unit accounts for on the multiple-choice section of the AP Comparative Government exam.

AP Comparative Government Exam Content

The exam lasts 2 hours and 30 minutes. As in the years past, there are two sections to the AP Comparative Government exam: a multiple-choice section and a free-response section. However, there are changes to the structure of both sections this year; read below for those changes.

Section 1: Multiple Choice

1 hour | 55 questions | 50% of score

The multiple-choice section of the AP Comparative Government exam will keep the same number of questions (55) as past tests, but students are now given an extra fifteen minutes to answer them. In addition, the number of possible answers shrink from five to four on the new test. There is also a shift in what you’re tested on, as the exam moves its focus from knowledge about individual countries to understanding of concepts and the ability to compare different concepts and countries.

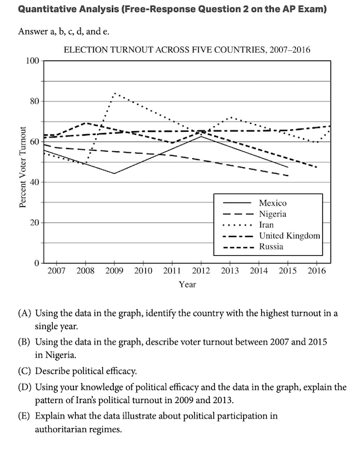

There are three types of multiple-choice questions you’ll encounter on the AP Comparative Government exam: stand-alone, quantitative analysis, and text-based analysis. 40-44 of the multiple-choice questions are stand-alone questions with no stimulus provided. There are also three sets of 2-3 questions testing your quantitative analysis ability, tasking you with analyzing a quantitative stimulus such as a line graph, chart, table, map, or infographic. Lastly, there are two sets of 2-3 questions focused on text-based analysis in which you’ll need to analyze text-based secondary sources.

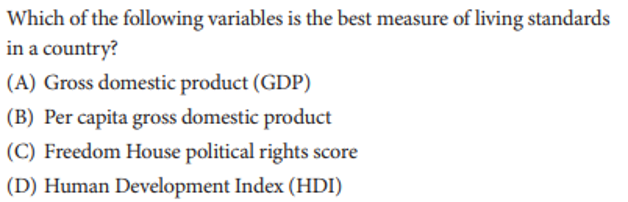

Example of an individual multiple-choice question:

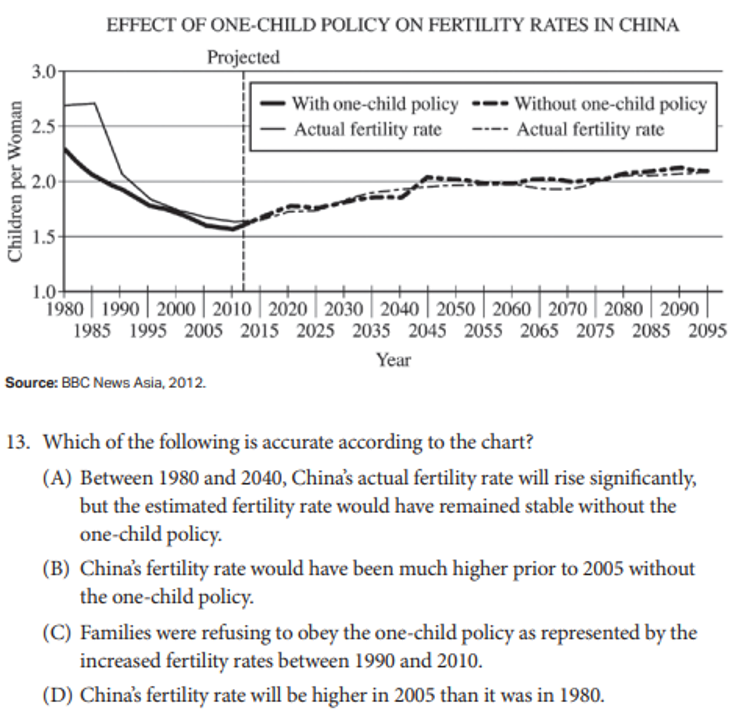

Example of a quantitative-analysis multiple-choice question:

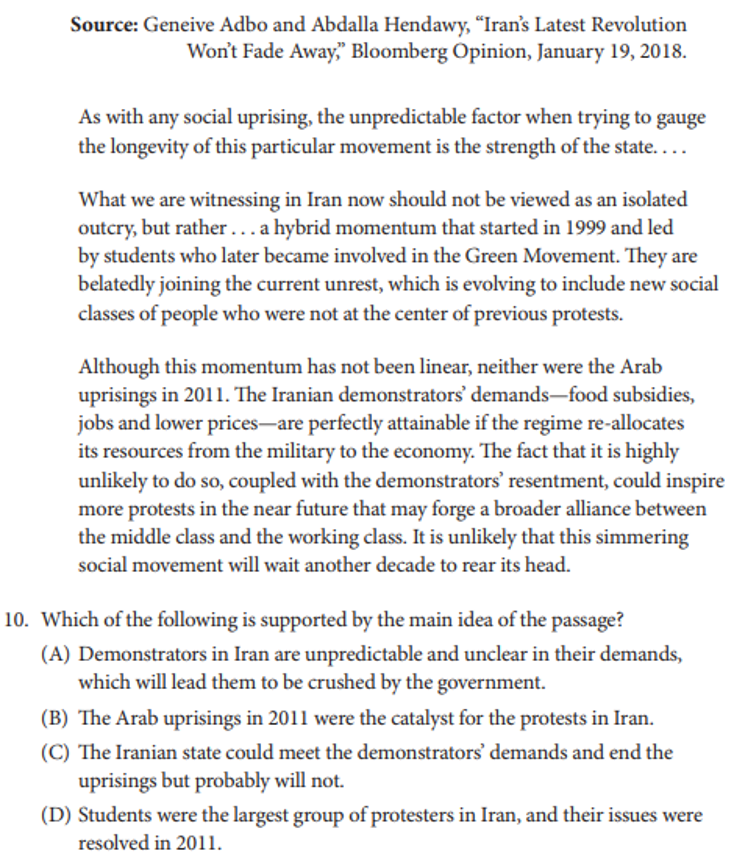

Example of a text-based multiple-choice question:

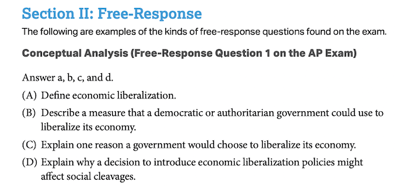

Section 2: Free Response

1 hour 30 minutes | 4 questions | 50% of score

The structure of the free-response questions has also changed on the 2020 AP Comparative Government exam , with the number of questions shrinking from eight to four. Additionally, the skills tested no longer vary from exam to exam; rather, they’re clearly defined. You’ll receive a question about conceptual analysis, quantitative analysis, and comparative analysis, and will need to write an argument-based essay.

Conceptual Analysis: Define political systems and explain and/or compare political systems, principles, institutions, processes, policies, and behaviors.

Quantitative Analysis: Identify trends and patterns or draw conclusions from quantitative data and explain how it relates to political systems, principles, institutions, processes, policies, and behaviors.

Comparative Analysis: Compare political concepts, systems, institutions, or policies in the AP Comparative Government’s six covered countries.

Argument Essay: Write an argument-based essay supported by evidence, based on concepts from the countries covered in the course.

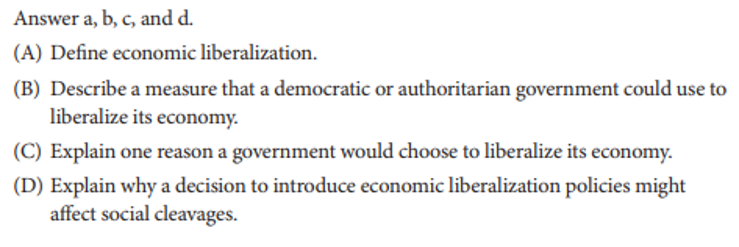

Example of a conceptual-analysis question:

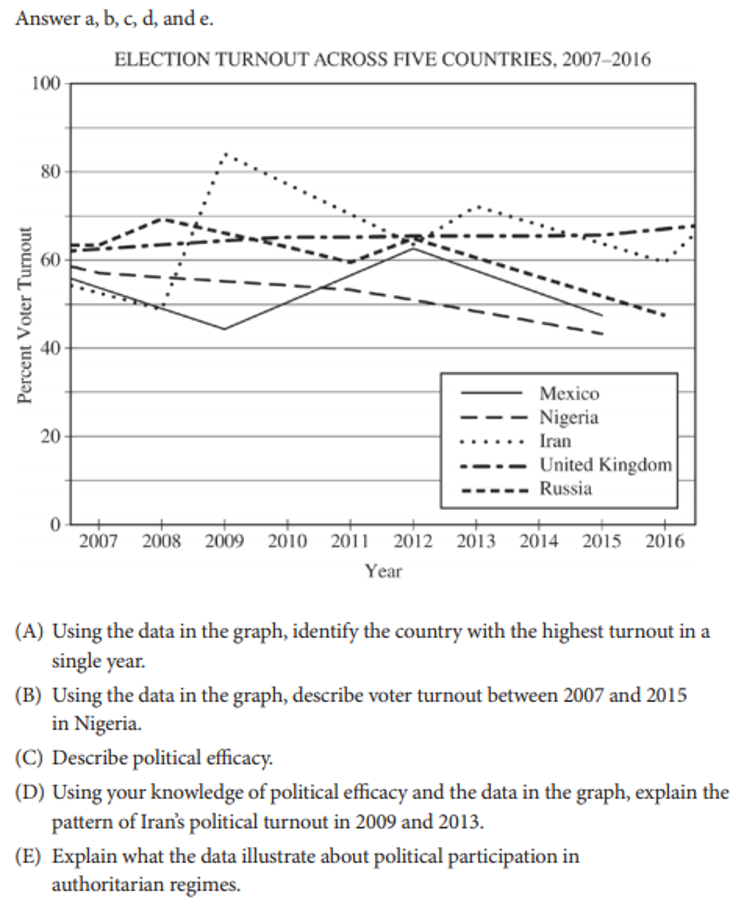

Example of a quantitative-analysis question:

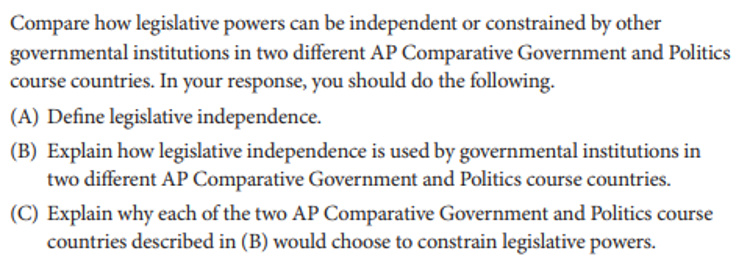

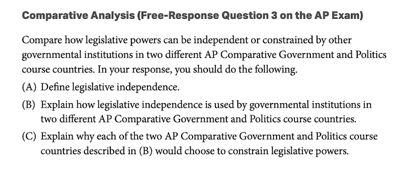

Example of a comparative-analysis question:

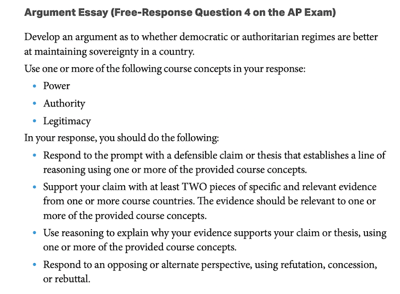

Example of an argument-based question:

AP Comparative Government Score Distribution, Average Score, and Passing Rate

According to the College Board in 2019, a relatively high percentage of students (22.4%) scored a 5. About one-third of test takers (66%) received a “passing” score of 3 or above on the AP Comparative Government exam. Here are the score distributions of all the AP exams if you’re interested in comparing the AP Comparative Gov scores to those of other exams.

Keep in mind, credit and advanced standing based on AP scores varies widely from school to school. Though a score of 3 is typically considered passing, it is not always enough to receive credit. See the College Board website for regulations regarding which APs qualify for course credits or advanced placement at specific colleges.

Best Ways to Study for the AP Comparative Government Exam

Step 1: assess your skills.

The best way to begin studying for any exam is to determine the areas you understand well and the areas you need to work on.

Start by taking a free practice test —this test is structured in the old format, but is still a helpful resource that can give you some hands-on experience with the upcoming test. You can score your own multiple-choice section and free responses, then you can have a teacher or friend score your free responses and average the scores, since this area is often more subjective. Once you have an actual score to work with, identify the areas you need to improve in when you take the actual test.

Step 2: Study the Theory

Crack open some study guides and start to solidify your understanding of the theory taught in this course.

Ask the Experts: The Barron’s AP Comparative Government and Politics: With 3 Practice Tests offers comprehensive reviews of this course and the material that might show up on the exam, along with three practice tests. Another good resource is the AP Comparative Government and Politics 2019 & 2020 Study Guide .

Ask a Teacher: There are also online study resources available to help you. Many AP teachers post complete study guides, review sheets, and test questions—such as this AP Comparative Government page from Mr. Baysdell from Davison High School in Davison, Michigan. Just be careful, as some resources may be outdated.

Try using an app: Apps are a convenient way to study for AP Exams—just make sure you read the reviews before you purchase or download one. You don’t want to end up spending money or time on an app that won’t actually be helpful to you. The AP Comparative Gov. & Politics app is decently well-reviewed and offers two study modes: flashcards and practice tests.

Step 3: Practice Multiple-Choice Questions

Because of the AP Comparative Government exam’s reformatting and shifting of focus this year, finding up-to-date multiple-choice questions to practice is challenging. A handful of sample multiple-choice questions are found in the AP Comparative Government Course and Exam Description . You’ll also find a free AP Comparative Government practice exam on Study.com .

When practicing multiple-choice questions, focus on trying to understand what each question is really asking—what skills or themes does the question tie into? In what way do the test makers want you to demonstrate your understanding of the subject material? Make sure to keep a running list of any unfamiliar concepts so that you can go back later and clarify them.

Step 4: Practice Free-Response Questions

There are four different types of free-response questions: conceptual analysis, quantitative analysis, comparative analysis, and an argument-based essay. Although the free-response questions have changed for 2020, it’s still beneficial to familiarize yourself with past free-response questions. You can find all of the free-response questions that have appeared on the AP Comparative Government exam, along with commentary, dating back to 1999 on the College Board’s website.

It’s important to keep the task verbs in mind for each question of this section. Make sure you understand what each question is asking you to do. These verbs commonly include “identify,” “define,” “describe,” “explain,” “provide one reason,” etc.

It may help you to underline each section of the question and check them off as you write. Students often lose points by forgetting to include one part of a multipart question. If a question asks you to identify and describe, make sure you do both. It is also a good idea to use the task verbs in your answer. If you are asked to “give a specific example,” start your part of the answer that addresses this question with “One specific example of this is…”

Step 5: Take Another Practice Exam

After you’ve practiced the multiple-choice and free-response questions, you should take another practice exam. Score the exam the same way as before, and repeat the studying process targeting areas that are still weak.

Step 6: Exam Day

If you’re taking the AP course associated with this exam, your teacher will walk you through how to register. If you’re self-studying, check out our blog post How to Self-Register for AP Exams .

For information about what to bring to the exam, see our post What Should I Bring to My AP Exam (And What Should I Definitely Leave at Home)?

Want access to expert college guidance — for free? When you create your free CollegeVine account, you will find out your real admissions chances, build a best-fit school list, learn how to improve your profile, and get your questions answered by experts and peers—all for free. Sign up for your CollegeVine account today to get a boost on your college journey!

For more guidance about the AP exams, check out these other informative articles:

2020 AP Exam Schedule

How Long is Each AP Exam?

Easiest and Hardest AP Exams

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Comparative Analysis

What It Is and Why It's Useful

Comparative analysis asks writers to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts. Beyond that, there's a lot of variation, but three overarching kinds of comparative analysis stand out:

- Coordinate (A ↔ B): In this kind of analysis, two (or more) texts are being read against each other in terms of a shared element, e.g., a memoir and a novel, both by Jesmyn Ward; two sets of data for the same experiment; a few op-ed responses to the same event; two YA books written in Chicago in the 2000s; a film adaption of a play; etc.

- Subordinate (A → B) or (B → A ): Using a theoretical text (as a "lens") to explain a case study or work of art (e.g., how Anthony Jack's The Privileged Poor can help explain divergent experiences among students at elite four-year private colleges who are coming from similar socio-economic backgrounds) or using a work of art or case study (i.e., as a "test" of) a theory's usefulness or limitations (e.g., using coverage of recent incidents of gun violence or legislation un the U.S. to confirm or question the currency of Carol Anderson's The Second ).

- Hybrid [A → (B ↔ C)] or [(B ↔ C) → A] , i.e., using coordinate and subordinate analysis together. For example, using Jack to compare or contrast the experiences of students at elite four-year institutions with students at state universities and/or community colleges; or looking at gun culture in other countries and/or other timeframes to contextualize or generalize Anderson's main points about the role of the Second Amendment in U.S. history.

"In the wild," these three kinds of comparative analysis represent increasingly complex—and scholarly—modes of comparison. Students can of course compare two poems in terms of imagery or two data sets in terms of methods, but in each case the analysis will eventually be richer if the students have had a chance to encounter other people's ideas about how imagery or methods work. At that point, we're getting into a hybrid kind of reading (or even into research essays), especially if we start introducing different approaches to imagery or methods that are themselves being compared along with a couple (or few) poems or data sets.

Why It's Useful

In the context of a particular course, each kind of comparative analysis has its place and can be a useful step up from single-source analysis. Intellectually, comparative analysis helps overcome the "n of 1" problem that can face single-source analysis. That is, a writer drawing broad conclusions about the influence of the Iranian New Wave based on one film is relying entirely—and almost certainly too much—on that film to support those findings. In the context of even just one more film, though, the analysis is suddenly more likely to arrive at one of the best features of any comparative approach: both films will be more richly experienced than they would have been in isolation, and the themes or questions in terms of which they're being explored (here the general question of the influence of the Iranian New Wave) will arrive at conclusions that are less at-risk of oversimplification.

For scholars working in comparative fields or through comparative approaches, these features of comparative analysis animate their work. To borrow from a stock example in Western epistemology, our concept of "green" isn't based on a single encounter with something we intuit or are told is "green." Not at all. Our concept of "green" is derived from a complex set of experiences of what others say is green or what's labeled green or what seems to be something that's neither blue nor yellow but kind of both, etc. Comparative analysis essays offer us the chance to engage with that process—even if only enough to help us see where a more in-depth exploration with a higher and/or more diverse "n" might lead—and in that sense, from the standpoint of the subject matter students are exploring through writing as well the complexity of the genre of writing they're using to explore it—comparative analysis forms a bridge of sorts between single-source analysis and research essays.

Typical learning objectives for single-sources essays: formulate analytical questions and an arguable thesis, establish stakes of an argument, summarize sources accurately, choose evidence effectively, analyze evidence effectively, define key terms, organize argument logically, acknowledge and respond to counterargument, cite sources properly, and present ideas in clear prose.

Common types of comparative analysis essays and related types: two works in the same genre, two works from the same period (but in different places or in different cultures), a work adapted into a different genre or medium, two theories treating the same topic; a theory and a case study or other object, etc.

How to Teach It: Framing + Practice

Framing multi-source writing assignments (comparative analysis, research essays, multi-modal projects) is likely to overlap a great deal with "Why It's Useful" (see above), because the range of reasons why we might use these kinds of writing in academic or non-academic settings is itself the reason why they so often appear later in courses. In many courses, they're the best vehicles for exploring the complex questions that arise once we've been introduced to the course's main themes, core content, leading protagonists, and central debates.

For comparative analysis in particular, it's helpful to frame assignment's process and how it will help students successfully navigate the challenges and pitfalls presented by the genre. Ideally, this will mean students have time to identify what each text seems to be doing, take note of apparent points of connection between different texts, and start to imagine how those points of connection (or the absence thereof)

- complicates or upends their own expectations or assumptions about the texts

- complicates or refutes the expectations or assumptions about the texts presented by a scholar

- confirms and/or nuances expectations and assumptions they themselves hold or scholars have presented

- presents entirely unforeseen ways of understanding the texts

—and all with implications for the texts themselves or for the axes along which the comparative analysis took place. If students know that this is where their ideas will be heading, they'll be ready to develop those ideas and engage with the challenges that comparative analysis presents in terms of structure (See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more on these elements of framing).

Like single-source analyses, comparative essays have several moving parts, and giving students practice here means adapting the sample sequence laid out at the " Formative Writing Assignments " page. Three areas that have already been mentioned above are worth noting:

- Gathering evidence : Depending on what your assignment is asking students to compare (or in terms of what), students will benefit greatly from structured opportunities to create inventories or data sets of the motifs, examples, trajectories, etc., shared (or not shared) by the texts they'll be comparing. See the sample exercises below for a basic example of what this might look like.

- Why it Matters: Moving beyond "x is like y but also different" or even "x is more like y than we might think at first" is what moves an essay from being "compare/contrast" to being a comparative analysis . It's also a move that can be hard to make and that will often evolve over the course of an assignment. A great way to get feedback from students about where they're at on this front? Ask them to start considering early on why their argument "matters" to different kinds of imagined audiences (while they're just gathering evidence) and again as they develop their thesis and again as they're drafting their essays. ( Cover letters , for example, are a great place to ask writers to imagine how a reader might be affected by reading an their argument.)

- Structure: Having two texts on stage at the same time can suddenly feel a lot more complicated for any writer who's used to having just one at a time. Giving students a sense of what the most common patterns (AAA / BBB, ABABAB, etc.) are likely to be can help them imagine, even if provisionally, how their argument might unfold over a series of pages. See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more information on this front.

Sample Exercises and Links to Other Resources

- Common Pitfalls

- Advice on Timing

- Try to keep students from thinking of a proposed thesis as a commitment. Instead, help them see it as more of a hypothesis that has emerged out of readings and discussion and analytical questions and that they'll now test through an experiment, namely, writing their essay. When students see writing as part of the process of inquiry—rather than just the result—and when that process is committed to acknowledging and adapting itself to evidence, it makes writing assignments more scientific, more ethical, and more authentic.

- Have students create an inventory of touch points between the two texts early in the process.

- Ask students to make the case—early on and at points throughout the process—for the significance of the claim they're making about the relationship between the texts they're comparing.

- For coordinate kinds of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is tied to thesis and evidence. Basically, it's a thesis that tells the reader that there are "similarities and differences" between two texts, without telling the reader why it matters that these two texts have or don't have these particular features in common. This kind of thesis is stuck at the level of description or positivism, and it's not uncommon when a writer is grappling with the complexity that can in fact accompany the "taking inventory" stage of comparative analysis. The solution is to make the "taking inventory" stage part of the process of the assignment. When this stage comes before students have formulated a thesis, that formulation is then able to emerge out of a comparative data set, rather than the data set emerging in terms of their thesis (which can lead to confirmation bias, or frequency illusion, or—just for the sake of streamlining the process of gathering evidence—cherry picking).

- For subordinate kinds of comparative analysis , a common pitfall is tied to how much weight is given to each source. Having students apply a theory (in a "lens" essay) or weigh the pros and cons of a theory against case studies (in a "test a theory") essay can be a great way to help them explore the assumptions, implications, and real-world usefulness of theoretical approaches. The pitfall of these approaches is that they can quickly lead to the same biases we saw here above. Making sure that students know they should engage with counterevidence and counterargument, and that "lens" / "test a theory" approaches often balance each other out in any real-world application of theory is a good way to get out in front of this pitfall.

- For any kind of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is structure. Every comparative analysis asks writers to move back and forth between texts, and that can pose a number of challenges, including: what pattern the back and forth should follow and how to use transitions and other signposting to make sure readers can follow the overarching argument as the back and forth is taking place. Here's some advice from an experienced writing instructor to students about how to think about these considerations:

a quick note on STRUCTURE

Most of us have encountered the question of whether to adopt what we might term the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure or the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure. Do we make all of our points about text A before moving on to text B? Or do we go back and forth between A and B as the essay proceeds? As always, the answers to our questions about structure depend on our goals in the essay as a whole. In a “similarities in spite of differences” essay, for instance, readers will need to encounter the differences between A and B before we offer them the similarities (A d →B d →A s →B s ). If, rather than subordinating differences to similarities you are subordinating text A to text B (using A as a point of comparison that reveals B’s originality, say), you may be well served by the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure.

Ultimately, you need to ask yourself how many “A→B” moves you have in you. Is each one identical? If so, you may wish to make the transition from A to B only once (“A→A→A→B→B→B”), because if each “A→B” move is identical, the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure will appear to involve nothing more than directionless oscillation and repetition. If each is increasingly complex, however—if each AB pair yields a new and progressively more complex idea about your subject—you may be well served by the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure, because in this case it will be visible to readers as a progressively developing argument.

As we discussed in "Advice on Timing" at the page on single-source analysis, that timeline itself roughly follows the "Sample Sequence of Formative Assignments for a 'Typical' Essay" outlined under " Formative Writing Assignments, " and it spans about 5–6 steps or 2–4 weeks.

Comparative analysis assignments have a lot of the same DNA as single-source essays, but they potentially bring more reading into play and ask students to engage in more complicated acts of analysis and synthesis during the drafting stages. With that in mind, closer to 4 weeks is probably a good baseline for many single-source analysis assignments. For sections that meet once per week, the timeline will either probably need to expand—ideally—a little past the 4-week side of things, or some of the steps will need to be combined or done asynchronously.

What It Can Build Up To

Comparative analyses can build up to other kinds of writing in a number of ways. For example:

- They can build toward other kinds of comparative analysis, e.g., student can be asked to choose an additional source to complicate their conclusions from a previous analysis, or they can be asked to revisit an analysis using a different axis of comparison, such as race instead of class. (These approaches are akin to moving from a coordinate or subordinate analysis to more of a hybrid approach.)

- They can scaffold up to research essays, which in many instances are an extension of a "hybrid comparative analysis."

- Like single-source analysis, in a course where students will take a "deep dive" into a source or topic for their capstone, they can allow students to "try on" a theoretical approach or genre or time period to see if it's indeed something they want to research more fully.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Formative Writing Assignments

- Single-Source Analysis

- Research Essays

- Multi-Modal or Creative Projects

- Giving Feedback to Students

Assignment Decoder

Browse Course Material

Course info.

- Prof. Chappell Lawson

Departments

- Political Science

As Taught In

- Political Philosophy

- American Politics

- Comparative Politics

Learning Resource Types

Introduction to comparative politics, course meeting times.

Lectures: 2 sessions / week; 1 hour / session

Recitations: 1 session / week; 1 hour / session

Prerequisites

There are no prerequisites for this course.

Class Objectives

This class addresses the fundamental problems of governance: the rationale for the state and ways to make sure that the state does what is in the best interests of people subject to its authority. The central purpose of the class is to help you think critically about these issues, which will include interrogating the assumptions that you– like everyone else– probably have about them.

The class also has a few corollary goals:

- To help you identify improvements in how your country could be governed;

- To help you make and critique arguments about public policy and social issues, based on analytical reasoning and empirical evidence;

- To give you practice in writing and presentation; and

- To provide the foundation for more specialized polisci classes, if you wish to take them.

Readings are listed under the specific session for which they are required. There is a logic to the choice of sessions and to the order in which readings are listed. Readings total 50–100 pages per week and should take you at most 4 hours to do. If you have trouble completing the readings in that time, please see me or the teaching assistant about strategies.

See the Readings section for further detail.

Class Participation

This subject is designed so that there is extensive class participation. The first day of each week normally involves more in the way of lecture from me to frame the salient issues, provide the necessary background for those unfamiliar with the topic, and generally make sure everyone is on the same page. The second session of each week and the recitation typically involve much more student participation, in the form of breakout groups and presentations. Even the lectures, however, are usually interactive.

I’d ask that you be prepared to participate actively and intelligently in class throughout the semester. For some people, that may mean pushing yourself to talk more than feels instinctively comfortable; for others it may mean holding yourself back. If participation becomes unbalanced, I may “cold call” people.

In formal presentations, there is a strict time limit, so be sure to practice and to time yourself ahead of time; you should make sure to frame your question clearly in the beginning and then move on swiftly to your main points.

Several class sessions are devoted to breakout groups. We will check informally throughout the semester to make sure that everyone is pulling their weight in the breakout groups and adjust participation grades accordingly. If you are concerned that your group cannot reach consensus on any point, you should not try to force one. Rather, use the division in your group to sharpen your argumentation and to highlight the pros and cons of different options. Basically, imagine that you are teeing the issue up for a decision-maker.

Tests and Exams

In the first week, we have a pop quiz (which will not be graded). There will also be an exam at the end of the semester that focuses on material not covered in other graded assignments (e.g., the readings and lectures from weeks in which no paper was due) and on synthesizing the material from the semester. The goal of this exam is to allow students who took the time to master this material to demonstrate that they have done so. Some questions may require you to extrapolate a bit, but if you have given some thought to the subjects covered in the class, done the reading over the course of the semester, and understood the lectures, you really should not need to study; briefly reviewing your notes ought to be sufficient. The format of the exam changes from one year to the next: it may be a single essay, several shorter essays, a multiple choice exam, or some combination.

Grading Policy

For more information on the activities in the table, see the Assignments section.

Other Engagements

Informal one-on-ones.

I’d enjoy the opportunity to meet one-on-one with each of you, for perhaps fifteen minutes, during the first half of the semester (in person or by Zoom). These meetings are designed to provide some informal, “get-to-know-each other” interaction unrelated to course content. They are a supplement to office hours, not a replacement for them; I hope you will still avail yourself of office hours with me or the TA for questions related to the class.

Gab Sessions / Cocktails / Mocktails

I will hold an entirely optional and informal gab session by Zoom most weeks, usually on Friday afternoons. To emphasize the informal nature of these conversations, please feel free to bring food and any beverage of your choice that you are legally allowed to consume. (I will almost certainly have a beverage in hand, and I am legally allowed to consume anything.) Drop in via Zoom when you like and leave whenever you like, without explanation or apology.

All topics, including current events and heretical questions, are fair game during these sessions. For instance, one of my favorite questions from last year was “What sort of political system do you think extraterrestrials would have?” In the absence of questions or a noteworthy event, I have listed some possible conversation starters for each week.

In the classroom, I obviously keep my personal opinions to myself. If you just attend classes and do no background research on me (positions I have held in government, campaign donations, party affiliation as listed on the voter rolls, public presentations I have given outside MIT, media appearances, etc.), you should be able to go the whole semester without being able to guess my political views or partisan leanings. In these informal gab sessions, however, I may sometimes speak in my own voice. Do not let any of the opinions I express in these instances – whether you agree with them or not – influence how you approach the regular class; in other words, you may have to compartmentalize information that you serendipitously acquire in these conversations.

I may occasionally invite some interesting friends to drop by. If any guests are present, the Chatham House Rule also applies: nothing people say may be attributed to them specifically, and you may not mention that they attended the session.

My wife and I have two active sons (ages 12 and 14) and an even more active dog. Any or all of them may make an unscheduled appearance during the gab sessions, and be advised that you may hear the sound of boys hitting each other with Wiffleball bats in the background.

Curated Outside Reading

The TA or I will occasionally send you articles on current events. We will choose these articles because they strike us as (a) particularly insightful, (b) balanced in their presentation of issues, and (c) relevant to course themes – with the idea being that “if you are going to read anything about this topic, check out this one.” Of course, you are under no obligation to read them.

Random Anecdotes TM

I will sometimes begin class with a very brief story or factoid about comparative politics (“Random Anecdote TM ”), a comment on a recent event, a mention of historically significant event on its anniversary, or something similar. The purpose of these remarks, which are not necessarily relevant to the subject matter for that particular class session (hence the “random”), is to get you thinking about some apparently puzzling political issue.

Classroom Norms

My classroom is meant to be a welcoming and comfortable environment. However, it is also a professional one. With this in mind, some rules of decorum:

- Per MIT norms, MIT’s codes of conduct , and Massachusetts state law, do not under any circumstances make video or audio recordings of class sessions. I cannot emphasize this stricture strongly enough.

- Please do not use any electronic devices during class.

- You should feel free to have water with you, but do not eat in class.

Historically, most students have called me “Professor Lawson,” but some have called me by my first name (“Chappell” – pronounced like “chapel” – or “Chap”), and the trend is in that direction. It’s up to you. Of course, you should also free to address me as “ Jefe, ” “Lawson-Zi,” or “ Dominus et Deus ” if you wish to more or less ensure getting extra credit.

Trigger Warnings

I am unconvinced that trigger warnings provide any real psychological benefit – the scientific literature provides grounds for skepticism – and I also find them vaguely infantilizing. Nevertheless, these days some people ask for them.