Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Laziness as the main cause of obesity, social effects of obesity, effects of obesity: health complications.

Bibliography

Maintaining good body weight is highly recommended by medical doctors as a way of promoting a healthy status of the body. This is to say that there is allowed body weight, which a person is supposed to maintain. Extreme deviations from this weight expose a person to several health complications.

While being underweight is not encouraged, cases of people who are overweight and increasing effects of this condition have raised concerns over the need of addressing the issue of obesity in the society today, where statistics are rising day and night. What is obesity? This refers to a medical condition in which a person’s body has high accumulation of body fat to the level of being fatal or a cause of serious health complications. Additionally, obesity is highly associated with one’s body mass index, abbreviated as BMI.

This denotes the value obtained when a person’s weight in kilograms is divided by the square of their height in meters (Burniat 3). According to medical experts, obesity occurs when the BMI exceeds 30kg/m 2 . While this is the case, people who have a BMI of between 25 and 29 and considered to be overweight. Obesity has a wide-range of negative effects, which may be a threat to the life of a person.

The fist effect of obesity is that it encourages laziness in the society. It is doubtless that obese people find it hard and strenuous to move from one point to the other because of accumulated fats. As a result, most of these people lead a sedentary lifestyle, which is usually characterized by minimal or no movement. In such scenarios, victims prefer being helped doing basic activities, including moving from one point to another.

Moreover, laziness makes one to be inactive and unproductive. For example, a student who is obese may find it hard to attend to his or her homework and class assignments, thus affecting performance. With regard to physical exercises, obese people perceive exercises as punishment, which is not meant for them (Korbonits 265). As a result, they do not accept simple activities like jogging because of their inability to move.

In line with this, obese people cannot participate in games like soccer, athletics, and rugby among others. Based on this sedentary lifestyle, obese people spend a lot of their time watching television, movies, and playing video games, which worsen the situation.

The main effect of obesity is health complications. Research indicates that most of the killer diseases like diabetes, heart diseases, and high blood pressure are largely associated with obesity. In the United States, obesity-related complications cost the nation approximately 150 billion USD and result into 0.3 million premature deaths annually.

When there is increase in body fat, it means that the body requires more nutrients and oxygen to support body tissues (Burniat 223). Since these elements can only be transported by the blood to various parts of the body, the workload of the heart is increased.

This increase in the workload of the heart exerts pressure on blood vessels, leading to high blood pressure. An increase in the heart rate may also be dangerous due to the inability of the body to supply required blood to various parts. Moreover, obesity causes diabetes, especially among adults as the body may become resistant to insulin. This resistance may lead to a high level of blood sugar, which is fatal.

Besides health complications, obesity causes an array of psychological effects, including inferiority complex among victims. Obese people suffer from depression, emanating from negative self-esteem and societal rejection. In some cases, people who become obese lose their friends and may get disapproval from teachers and other personalities (Korbonits 265). This is mainly based on the assumption that people become obese due to lack of self-discipline. In extreme cases, obese people may not be considered for promotion at workplaces, because of the negative perception held against them.

Due to inferiority complex, obese people avoid being in public and prefer being alone. This is because they imagine how the world sees them and may also find it hard being involved in public activities because of their sizes.

This further makes them to consider themselves unattractive based on their deviation from what is considered as the normal body size and shape. Regardless of how obese people are treated, they always believe that they are being undermined because of their body size.

In summary, obesity is a major cause of premature deaths in the United States and around the world. This health condition occurs when there is excess accumulation of body fat, caused by unhealthy lifestyles. Obesity is largely associated with several killer diseases like high blood pressure, diabetes, and diseases of the heart.

These diseases drain world economies since most of them are fatal and expensive to manage. Additionally, obesity promotes sedentary life where victims minimize movement by adopting an inactive lifestyle. Moreover, obese victims suffer psychologically because of societal rejection. In general, obesity has a wide-range of negative effects, which may be a threat to the life of a person.

Burniat, Walter. Child and Adolescent Obesity: Causes and Consequences, Prevention and Management . United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Print.

Korbonits, Márta. Obesity and Metabolism . Switzerland: Karger Publishers, 2008. Print.

- Screening for Obesity

- Parental Education on Overweight and Obese Children

- Blood Pressure and Obesity Solution

- Eating Disorders: Assessment & Misconceptions

- Human Digestion

- Definitions of Obesity and Criteria for Diagnosing It

- Obesity Could Be Catching

- White Wines vs. Red Wines

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 11). Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/effects-of-obesity/

"Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay." IvyPanda , 11 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/effects-of-obesity/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay'. 11 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay." December 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/effects-of-obesity/.

1. IvyPanda . "Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay." December 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/effects-of-obesity/.

IvyPanda . "Causes and Effects of Obesity Essay." December 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/effects-of-obesity/.

Obesity in America: Cause and Effect Essay Sample

It is clear that the American lifestyle has contributed to the increasing prevalence of obesity. With estimates from the Washington-based Centers for Disease Prevention in the Department of Health and Human Services indicating that one in three American adults is overweight, it is evident that the country is facing an obesity epidemic. To better understand the causes and effects of obesity, research is needed to further explore the issue. For those struggling with obesity, coursework assistance may be available to help them make the necessary lifestyle changes in order to live a healthier life.

Writing a thesis paper on the topic of obesity can be extremely challenging. It requires extensive research and time to adequately cover the subject. However, there are services available that can provide assistance with the writing process. Pay for a thesis allows for the benefit of having an experienced professional provide guidance and support throughout the entire process.

Causes of Obesity

Every phenomenon must have a reason. In order to write a cause and effect essay , you need to analyze the topic carefully to cover all aspects. Obesity is considered to be a complex illness, with a number of factors contributing to its development. These can be:

- hereditary;

As you may have guessed, it is the latter category of causes and effects that we are interested in. At this point, we care about the five ones that have made the biggest contribution.

Product Range

The main cause of obesity is junk food and an unbalanced diet rich in simple carbohydrates, fats, and sugars, plus a bunch of additives. Manufactured, processed, refined, and packaged meals are the most popular. Thanks to advances in technology, Americans have come to mass-produce meals that keep fresh longer and taste better. It takes less time to prepare unhealthy, processed foods in the microwave than it does to cook them yourself.

Lack of a work-life balance, high-stress levels, insufficient sleeping hours contribute to body weight gain. Not only do these factors contribute to this, but failing to take the time to do your homework can also have a negative impact on your physical health. Without a healthy, balanced approach to work, rest, and play, you may find yourself increasingly dependent on a sedentary lifestyle that can lead to overweight consequences. Many Americans work 50, 60, or more hours a week and suffer from a deficit of leisure hours. Cooking processed foods saves them hours and money, even though they end up costing them a lot more – by causing cardiovascular disease. In addition, obese people feel stressed on a regular basis in the United States metropolitan areas. Many of them are simply binge eating under the influence of negative emotions. Chronic overeating leads to a disturbance in the appetite center in the brain, and the normal amount of food eaten can no longer suppress hunger as much as necessary, affecting the body mass.

Food Deserts

The term ‘ food desert ‘ refers to poor areas (urban, suburban and rural) with limited access to fresh fruit, grains, and vegetables – places where it is much easier to access junk food. A grocery shop in a food desert that sells healthy foods may be 10-15 miles away, while a mini-market or cheap shop that sells harmful snacks is close to the house. In such a world, it takes much more effort to eat healthier, form eating habits, and stay slim.

Everyone’s Passion for Sweets

Consuming sweets in large quantities is addictive: the more and easier we give the body energy, the more the brain uses serotonin and dopamine to encourage it – it will make obese people want sweets again and again during the day. Cakes and pastries are fast carbohydrates that easily satisfy hunger and increase body mass. Despite the harm of sweets, obese people experience the need for them to satiate. Sweetened carbonated drinks are one of the main sources of sugar in the American diet. Moreover, some individuals may be more adversely affected by such diets than others: patients with a genetic predisposition to obesity gain body mass faster from sugary drinks than those without it. This leads to childhood obesity.

The Harm of Tolerance

Every year, the body positive movement is becoming more and more popular all over the world. It would seem that this major trend should have freed us from the problems associated with the cult of thinness and society’s notorious standards. In many ways, a positive attitude towards the body has proved fruitful. For example, the notion of beauty has clearly broadened. Now on fashion shows and magazine covers, you can see not only a girl with perfectly retouched skin and without a single hint of body fat but also an ordinary person with its inherent features: overweight, wrinkles, hair, and individual skin features. In general, all the things that we are all so familiar with in real life.

Does it really make that much sense? Is this a positive thing in terms of the cause and effect topic regarding obesity? In short, opinions are divided. Extremes aren’t easy to overcome. Not everyone manages to do it. Researchers have concluded that due to plus size having become positioned as a variant of the norm, more persons have become obese. Many obese Americans have formed the opinion that it is really quite normal, and they have become oblivious to the damage it does to their health. This is what we are going to focus on next.

Effects of Obesity

We all know that obesity is dangerous to health. However, medical studies show that most adults are unaware of the number of complications and diseases that obesity in America entails. So they are fairly comfortable with becoming gradually fatter. But indifference is replaced by concern when obesity related diseases begin to occur.

For interesting examples of students writing that also reveal the causes and effects of other phenomena, consult the custom essay service offering essays by professionals. In this way, you will realize the importance of highlighting the effects right after the causes.

Is obesity an aesthetic disadvantage, an inconvenience, a limitation in physical activity or is it an illness after all? How does it affect health, and what are the consequences? The visible signs of obesity are by no means the only complication associated with this condition. Obesity creates a high risk of life-threatening diseases such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, heart attack, myocardial infarction, and kidney and liver problems. Moreover, it can also lead to disability.

Cardiovascular Disease

This is the most serious and damaging impact on the body and blood vessels in particular. Every extra kilo is a huge additional load on the heart. Obesity increases the risk of heart attacks. Experts from the American Heart Association have developed a paper on the relationship between obesity and cardiovascular disease, which discusses the impact of obesity on the diagnosis and outcomes of patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Childhood obesity aggravates the course of cardiovascular disease from a very early age. The fact that even kids and adolescents are obese is associated with high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia.

The result is excessive insulin production in the body. This, in turn, leads to an overabundance of insulin in the blood, which makes the peripheral tissues more resistant to it. As a consequence of the above, sodium metabolism is disturbed, and blood pressure rises. It is important to remember that excessive carbohydrate food intake leads to increased production of insulin by the pancreas. Excess insulin in the human body easily converts glucose into fat. And obesity reduces tissue sensitivity to insulin itself. This kind of vicious circle leads to type 2 diabetes.

Effects on Joints

Obesity increases the load on joints to a great extent, especially if one undergoes little or no physical activity. For instance, if one lives in a megalopolis, where all physical activity consists of getting off the sofa, walking to the car, and plumping up in an office chair at work. All this leads to a reduction in muscle mass, which is already weak, and all the load falls on the joints and ligaments.

The result is arthritis, arthrosis, and osteochondrosis. Consequently, a seemingly illogical situation is formed – there is practically no exercise, but joints are worn out harder than in the case of powerlifters. In turn, according to a study by the University of California, reducing body weight reduces the risk of osteoarthritis.

Infertility

In most cases, being obese leads to endocrine infertility, as it causes an irregular menstrual cycle. Women experience thyroid disease, polycystic ovarian syndrome, problems with conception, and decreased progesterone hormone. Obese men are faced with erectile dysfunction, reduced testosterone levels, and infertility. It should be noted that the mother’s obesity affects not only her health but also the one of her unborn child. These children are at higher risk of congenital malformations.

Corresponding Inconveniences

Public consciousness is still far from the notion that obese people are sick individuals. The social significance of the issue is that people who are severely obese find it difficult to get a job. They experience discriminatory restrictions on promotion, daily living disadvantages, restrictions on mobility, clothing choices, discomfort with adequate hygiene, and sexual dysfunction. Some of these individuals not only suffer from illness and limited mobility but also have low self-esteem, depression, and other psychological problems due to involuntary isolation by watching television or playing video games. Therefore, the public has to recognize the need to establish and implement national and childhood obesity epidemic prevention programs.

Society today provokes unintentional adult and childhood obesity among its members by encouraging the consumption of high-fat, high-calorie foods and, at the same time, by technological advances, promoting sedentary lifestyles like spending time watching television or playing video games. These social and technological factors have contributed to the rise in obesity in recent decades. Developing a responsible attitude towards health will only have a full impact if people are given the opportunity to enjoy a healthy lifestyle. At the level of the community as a whole, it is therefore important to support people in adhering to dieting recommendations through the continued implementation of evidence-based and demographic-based policies to make regular physical activity and good nutrition both affordable and feasible for all. It is recommended to cut down on the food consumed.

Related posts:

- The Great Gatsby (Analyze this Essay Online)

- Pollution Cause and Effect Essay Sample

- Essay Sample on How Can I Be a Good American

- The Power of Imaging: Why I am Passionate about Becoming a Sonographer

Improve your writing with our guides

Youth Culture Essay Prompt and Discussion

Why Should College Athletes Be Paid, Essay Sample

Reasons Why Minimum Wage Should Be Raised Essay: Benefits for Workers, Society, and The Economy

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 27 February 2019

Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis

- Matthias Blüher 1

Nature Reviews Endocrinology volume 15 , pages 288–298 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

56k Accesses

2560 Citations

981 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Health policy

- Pathogenesis

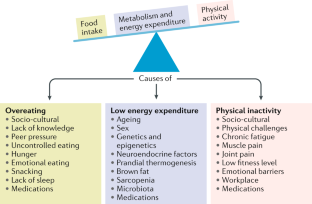

The prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide in the past ~50 years, reaching pandemic levels. Obesity represents a major health challenge because it substantially increases the risk of diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, fatty liver disease, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, dementia, osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnoea and several cancers, thereby contributing to a decline in both quality of life and life expectancy. Obesity is also associated with unemployment, social disadvantages and reduced socio-economic productivity, thus increasingly creating an economic burden. Thus far, obesity prevention and treatment strategies — both at the individual and population level — have not been successful in the long term. Lifestyle and behavioural interventions aimed at reducing calorie intake and increasing energy expenditure have limited effectiveness because complex and persistent hormonal, metabolic and neurochemical adaptations defend against weight loss and promote weight regain. Reducing the obesity burden requires approaches that combine individual interventions with changes in the environment and society. Therefore, a better understanding of the remarkable regional differences in obesity prevalence and trends might help to identify societal causes of obesity and provide guidance on which are the most promising intervention strategies.

Obesity prevalence has increased in pandemic dimensions over the past 50 years.

Obesity is a disease that can cause premature disability and death by increasing the risk of cardiometabolic diseases, osteoarthritis, dementia, depression and some types of cancers.

Obesity prevention and treatments frequently fail in the long term (for example, behavioural interventions aiming at reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure) or are not available or suitable (bariatric surgery) for the majority of people affected.

Although obesity prevalence increased in every single country in the world, regional differences exist in both obesity prevalence and trends; understanding the drivers of these regional differences might help to provide guidance for the most promising intervention strategies.

Changes in the global food system together with increased sedentary behaviour seem to be the main drivers of the obesity pandemic.

The major challenge is to translate our knowledge of the main causes of increased obesity prevalence into effective actions; such actions might include policy changes that facilitate individual choices for foods that have reduced fat, sugar and salt content.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Obesity and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases

Obesity: a 100 year perspective

Obesity-induced and weight-loss-induced physiological factors affecting weight regain

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor, 2017. WHO https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-progress-monitor-2017/en/ (2017).

Fontaine, K. R., Redden, D. T., Wang, C., Westfall, A. O. & Allison, D. B. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 289 , 187–193 (2003).

PubMed Google Scholar

Berrington de Gonzalez, A. et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 363 , 2211–2219 (2010).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Prospective Studies Collaboration. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 373 , 1083–1096 (2009).

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Woolf, A. D. & Pfleger, B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull. World Health Organ. 81 , 646–656 (2003).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bray, G. A. et al. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes. Rev. 18 , 715–723 (2017).

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. WHO https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (2016).

World Health Organization. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. WHO https://www.who.int/nmh/events/un_ncd_summit2011/political_declaration_en.pdf (2012).

Franco, M. et al. Population-wide weight loss and regain in relation to diabetes burden and cardiovascular mortality in Cuba 1980-2010: repeated cross sectional surveys and ecological comparison of secular trends. BMJ 346 , f1515 (2013).

Swinburn, B. A. et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378 , 804–814 (2011).

Yanovski, J. A. Obesity: Trends in underweight and obesity — scale of the problem. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14 , 5–6 (2018).

Heymsfield, S. B. & Wadden, T. A. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 376 , 254–266 (2017).

Murray, S., Tulloch, A., Gold, M. S. & Avena, N. M. Hormonal and neural mechanisms of food reward, eating behaviour and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10 , 540–552 (2014).

Farooqi, I. S. Defining the neural basis of appetite and obesity: from genes to behaviour. Clin. Med. 14 , 286–289 (2014).

Google Scholar

Anand, B. K. & Brobeck, J. R. Hypothalamic control of food intake in rats and cats. Yale J. Biol. Med. 24 , 123–140 (1951).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhang, Y. et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 372 , 425–432 (1994).

Coleman, D. L. & Hummel, K. P. Effects of parabiosis of normal with genetically diabetic mice. Am. J. Physiol. 217 , 1298–1304 (1969).

Farooqi, I. S. & O’Rahilly, S. 20 years of leptin: human disorders of leptin action. J. Endocrinol. 223 , T63–T70 (2014).

Börjeson, M. The aetiology of obesity in children. A study of 101 twin pairs. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 65 , 279–287 (1976).

Stunkard, A. J., Harris, J. R., Pedersen, N. L. & McClearn, G. E. The body-mass index of twins who have been reared apart. N. Engl. J. Med. 322 , 1483–1487 (1990).

Montague, C. T. et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 387 , 903–908 (1997).

Farooqi, I. S. et al. Effects of recombinant leptin therapy in a child with congenital leptin deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 341 , 879–884 (1999).

Clément, K. et al. A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature 392 , 398–401 (1998).

Farooqi, I. S. et al. Dominant and recessive inheritance of morbid obesity associated with melanocortin 4 receptor deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 106 , 271–279 (2000).

Krude, H. et al. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat. Genet. 19 , 155–157 (1998).

Hebebrand, J., Volckmar, A. L., Knoll, N. & Hinney, A. Chipping away the ‘missing heritability’: GIANT steps forward in the molecular elucidation of obesity - but still lots to go. Obes. Facts 3 , 294–303 (2010).

Speliotes, E. K. et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat. Genet. 42 , 937–948 (2010).

Sharma, A. M. & Padwal, R. Obesity is a sign - over-eating is a symptom: an aetiological framework for the assessment and management of obesity. Obes. Rev. 11 , 362–370 (2010).

Berthoud, H. R., Münzberg, H. & Morrison, C. D. Blaming the brain for obesity: integration of hedonic and homeostatic mechanisms. Gastroenterology 152 , 1728–1738 (2017).

Government Office for Science. Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices – project report. GOV.UK https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287937/07-1184x-tackling-obesities-future-choices-report.pdf (2007).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision. WHO http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en (2010).

Hebebrand, J. et al. A proposal of the European Association for the Study of Obesity to improve the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for obesity based on the three dimensions. Obes. Facts 10 , 284–307 (2017).

Ramos Salas, X. et al. Addressing weight bias and discrimination: moving beyond raising awareness to creating change. Obes. Rev. 18 , 1323–1335 (2017).

Sharma, A. M. et al. Conceptualizing obesity as a chronic disease: an interview with Dr. Arya Sharma. Adapt. Phys. Activ Q. 35 , 285–292 (2018).

Hebebrand, J. et al. “Eating addiction”, rather than “food addiction”, better captures addictive-like eating behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 47 , 295–306 (2014).

Phelan, S. M. et al. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes. Rev. 16 , 319–326 (2015).

Kushner, R. F. et al. Obesity coverage on medical licensing examinations in the United States. What is being tested? Teach Learn. Med. 29 , 123–128 (2017).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 390 , 2627–2642 (2017).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 387 , 1377–1396 (2016).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Obesity update 2017. OECD https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Obesity-Update-2017.pdf (2017).

Geserick, M. et al. BMI acceleration in early childhood and risk of sustained obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 379 , 1303–1312 (2018).

Ezzati, M. & Riboli, E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for noncommunicable diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 , 954–964 (2013).

Kleinert, S. & Horton, R. Rethinking and reframing obesity. Lancet 385 , 2326–2328 (2015).

Roberto, C. A. et al. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet 385 , 2400–2409 (2015).

Lundborg, P., Nystedt, P. & Lindgren, B. Getting ready for the marriage market? The association between divorce risks and investments in attractive body mass among married Europeans. J. Biosoc. Sci. 39 , 531–544 (2007).

McCabe, M. P. et al. Socio-cultural agents and their impact on body image and body change strategies among adolescents in Fiji, Tonga, Tongans in New Zealand and Australia. Obes. Rev. 12 , 61–67 (2011).

Hayashi, F., Takimoto, H., Yoshita, K. & Yoshiike, N. Perceived body size and desire for thinness of young Japanese women: a population-based survey. Br. J. Nutr. 96 , 1154–1162 (2006).

Hardin, J., McLennan, A. K. & Brewis, A. Body size, body norms and some unintended consequences of obesity intervention in the Pacific islands. Ann. Hum. Biol. 45 , 285–294 (2018).

Monteiro, C. A., Conde, W. L. & Popkin, B. M. Income-specific trends in obesity in Brazil: 1975–2003. Am. J. Public Health 97 , 1808–1812 (2007).

Mariapun, J., Ng, C. W. & Hairi, N. N. The gradual shift of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity towards the poor in a multi-ethnic developing country: findings from the Malaysian National Health and Morbidity Surveys. J. Epidemiol. 28 , 279–286 (2018).

Gebrie, A., Alebel, A., Zegeye, A., Tesfaye, B. & Ferede, A. Prevalence and associated factors of overweight/ obesity among children and adolescents in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Obes. 5 , 19 (2018).

Rokholm, B., Baker, J. L. & Sørensen, T. I. The levelling off of the obesity epidemic since the year 1999 — a review of evidence and perspectives. Obes. Rev. 11 , 835–846 (2010).

Hauner, H. et al. Overweight, obesity and high waist circumference: regional differences in prevalence in primary medical care. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 105 , 827–833 (2008).

Myers, C. A. et al. Regional disparities in obesity prevalence in the United States: a spatial regime analysis. Obesity 23 , 481–487 (2015).

Wilkinson, R. G. & Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better 89–102 (Bloomsbury Press London, 2009).

Sarget, M. Why inequality is fatal. Nature 458 , 1109–1110 (2009).

Plachta-Danielzik, S. et al. Determinants of the prevalence and incidence of overweight in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 13 , 1870–1881 (2010).

Bell, A. C., Ge, K. & Popkin, B. M. The road to obesity or the path to prevention: motorized transportation and obesity in China. Obes. Res. 10 , 277–283 (2002).

Ludwig, J. et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes — a randomized social experiment. N. Engl. J. Med. 365 , 1509–1519 (2011).

Beyerlein, A., Kusian, D., Ziegler, A. G., Schaffrath-Rosario, A. & von Kries, R. Classification tree analyses reveal limited potential for early targeted prevention against childhood overweight. Obesity 22 , 512–517 (2014).

Reilly, J. J. et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. BMJ 330 , 1357 (2005).

Kopelman, P. G. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature 404 , 635–643 (2000).

CAS Google Scholar

Bouchard, C. et al. The response to long-term overfeeding in identical twins. N. Engl. J. Med. 322 , 1477–1482 (1990).

Sadeghirad, B., Duhaney, T., Motaghipisheh, S., Campbell, N. R. & Johnston, B. C. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 17 , 945–959 (2016).

Gilbert-Diamond, D. et al. Television food advertisement exposure and FTO rs9939609 genotype in relation to excess consumption in children. Int. J. Obes. 41 , 23–29 (2017).

Frayling, T. M. et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 316 , 889–894 (2007).

Loos, R. J. F. & Yeo, G. S. H. The bigger picture of FTO-the first GWAS-identified obesity gene. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10 , 51–61 (2014).

Wardle, J. et al. Obesity associated genetic variation in FTO is associated with diminished satiety. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93 , 3640–3643 (2008).

Tanofsky-Kraff, M. et al. The FTO gene rs9939609 obesity-risk allele and loss of control over eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90 , 1483–1488 (2009).

Hess, M. E. et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat. Neurosci. 16 , 1042–1048 (2013).

Fredriksson, R. et al. The obesity gene, FTO, is of ancient origin, up-regulated during food deprivation and expressed in neurons of feeding-related nuclei of the brain. Endocrinology 149 , 2062–2071 (2008).

Cohen, D. A. Neurophysiological pathways to obesity: below awareness and beyond individual control. Diabetes 57 , 1768–1773 (2008).

Richard, D. Cognitive and autonomic determinants of energy homeostasis in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11 , 489–501 (2015).

Clemmensen, C. et al. Gut-brain cross-talk in metabolic control. Cell 168 , 758–774 (2017).

Timper, K. & Brüning, J. C. Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: pathways to obesity. Dis. Model. Mech. 10 , 679–689 (2017).

Kim, K. S., Seeley, R. J. & Sandoval, D. A. Signalling from the periphery to the brain that regulates energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19 , 185–196 (2018).

Cutler, D. M., Glaeser, E. L. & Shapiro, J. M. Why have Americans become more obese? J. Econ. Perspect. 17 , 93–118 (2003).

Löffler, A. et al. Effects of psychological eating behaviour domains on the association between socio-economic status and BMI. Public Health Nutr. 20 , 2706–2712 (2017).

Chan, R. S. & Woo, J. Prevention of overweight and obesity: how effective is the current public health approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7 , 765–783 (2010).

Hsueh, W. C. et al. Analysis of type 2 diabetes and obesity genetic variants in Mexican Pima Indians: marked allelic differentiation among Amerindians at HLA. Ann. Hum. Genet. 82 , 287–299 (2018).

Schulz, L. O. et al. Effects of traditional and western environments on prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians in Mexico and the US. Diabetes Care 29 , 1866–1871 (2006).

Rotimi, C. N. et al. Distribution of anthropometric variables and the prevalence of obesity in populations of west African origin: the International Collaborative Study on Hypertension in Blacks (ICSHIB). Obes. Res. 3 , 95–105 (1995).

Durazo-Arvizu, R. A. et al. Rapid increases in obesity in Jamaica, compared to Nigeria and the United States. BMC Public Health 8 , 133 (2008).

Hu, F. B., Li, T. Y., Colditz, G. A., Willett, W. C. & Manson, J. E. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 289 , 1785–1791 (2003).

Rissanen, A. M., Heliövaara, M., Knekt, P., Reunanen, A. & Aromaa, A. Determinants of weight gain and overweight in adult Finns. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 45 , 419–430 (1991).

Zimmet, P. Z., Arblaster, M. & Thoma, K. The effect of westernization on native populations. Studies on a Micronesian community with a high diabetes prevalence. Aust. NZ J. Med. 8 , 141–146 (1978).

Ulijaszek, S. J. Increasing body size among adult Cook Islanders between 1966 and 1996. Ann. Hum. Biol. 28 , 363–373 (2001).

Snowdon, W. & Thow, A. M. Trade policy and obesity prevention: challenges and innovation in the Pacific Islands. Obes. Rev. 14 , 150–158 (2013).

McLennan, A. K. & Ulijaszek, S. J. Obesity emergence in the Pacific islands: why understanding colonial history and social change is important. Public Health Nutr. 18 , 1499–1505 (2015).

Becker, A. E., Gilman, S. E. & Burwell, R. A. Changes in prevalence of overweight and in body image among Fijian women between 1989 and 1998. Obes. Res. 13 , 110–117 (2005).

Swinburn, B., Sacks, G. & Ravussin, E. Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90 , 1453–1456 (2009).

Swinburn, B. A. et al. Estimating the changes in energy flux that characterize the rise in obesity prevalence. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89 , 1723–1728 (2009).

US Department of Agriculture. Food availability (per capita) data system. USDA https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system/ (updated 29 Oct 2018).

Carden, T. J. & Carr, T. P. Food availability of glucose and fat, but not fructose, increased in the U.S. between 1970 and 2009: analysis of the USDA food availability data system. Nutr. J. 12 , 130 (2013).

Hall, K. D., Guo, J., Dore, M. & Chow, C. C. The progressive increase of food waste in America and its environmental impact. PLOS ONE 4 , e7940 (2009).

Scarborough, P. et al. Increased energy intake entirely accounts for increase in body weight in women but not in men in the UK between 1986 and 2000. Br. J. Nutr. 105 , 1399–1404 (2011).

McGinnis, J. M. & Nestle, M. The Surgeon General’s report on nutrition and health: policy implications and implementation strategies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 49 , 23–28 (1989).

Krebs-Smith, S. M., Reedy, J. & Bosire, C. Healthfulness of the U.S. food supply: little improvement despite decades of dietary guidance. Am. J. Prev. Med. 38 , 472–477 (2010).

Malik, V. S., Popkin, B. M., Bray, G. A., Després, J. P. & Hu, F. B. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 121 , 1356–1364 (2010).

Schulze, M. B. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 292 , 927–934 (2004).

Mozaffarian, D., Hao, T., Rimm, E. B., Willett, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 364 , 2392–2404 (2011).

Malik, V. S. & Hu, F. B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and health: where does the evidence stand? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94 , 1161–1162 (2011).

Qi, Q. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and genetic risk of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 367 , 1387–1396 (2012).

Heiker, J. T. et al. Identification of genetic loci associated with different responses to high-fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6N and C57BL/6J substrains. Physiol. Genomics 46 , 377–384 (2014).

Wahlqvist, M. L. et al. Early-life influences on obesity: from preconception to adolescence. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1347 , 1–28 (2015).

Rohde, K. et al. Genetics and epigenetics in obesity. Metabolism . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2018.10.007 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Panzeri, I. & Pospisilik, J. A. Epigenetic control of variation and stochasticity in metabolic disease. Mol. Metab. 14 , 26–38 (2018).

Ruiz-Hernandez, A. et al. Environmental chemicals and DNA methylation in adults: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Clin. Epigenet. 7 , 55 (2015).

Quarta, C., Schneider, R. & Tschöp, M. H. Epigenetic ON/OFF switches for obesity. Cell 164 , 341–342 (2016).

Dalgaard, K. et al. Trim28 haploinsufficiency triggers bi-stable epigenetic obesity. Cell 164 , 353–364 (2015).

Michaelides, M. et al. Striatal Rgs4 regulates feeding and susceptibility to diet-induced obesity. Mol. Psychiatry . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0120-7 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Weihrauch-Blüher, S. et al. Current guidelines for obesity prevention in childhood and adolescence. Obes. Facts 11 , 263–276 (2018).

Nakamura, R. et al. Evaluating the 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Chile: An observational study in urban areas. PLOS Med. 15 , e1002596 (2018).

Colchero, M. A., Molina, M. & Guerrero-López, C. M. After Mexico implemented a tax, purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages decreased and water increased: difference by place of residence, household composition, and income level. J. Nutr. 147 , 1552–1557 (2017).

Brownell, K. D. & Warner, K. E. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 87 , 259–294 (2009).

Mialon, M., Swinburn, B., Allender, S. & Sacks, G. ‘Maximising shareholder value’: a detailed insight into the corporate political activity of the Australian food industry. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 41 , 165–171 (2017).

Peeters, A. Obesity and the future of food policies that promote healthy diets. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14 , 430–437 (2018).

Hawkes, C., Jewell, J. & Allen, K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes. Rev. 14 (Suppl. 2), 159–168 (2013).

World Health Organisation. Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA). WHO https://www.who.int/nutrition/gina/en/ (2012).

Popkin, B., Monteiro, C. & Swinburn, B. Overview: Bellagio Conference on program and policy options for preventing obesity in the low- and middle-income countries. Obes. Rev. 14 (Suppl. 2), 1–8 (2013).

Download references

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Endocrinology thanks G. Bray, A. Sharma and H. Toplak for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Matthias Blüher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Matthias Blüher .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 15 , 288–298 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8

Download citation

Published : 27 February 2019

Issue Date : May 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Body composition, lifestyle, and depression: a prospective study in the uk biobank.

BMC Public Health (2024)

Physical activity, gestational weight gain in obese patients with early gestational diabetes and the perinatal outcome – a randomised–controlled trial

- Lukasz Adamczak

- Urszula Mantaj

- Ewa Wender-Ozegowska

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2024)

Effects of N-acetylcysteine on the expressions of UCP1 and factors related to thyroid function in visceral adipose tissue of obese adults: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial

- Mohammad Hassan Sohouli

- Ghazaleh Eslamian

Genes & Nutrition (2024)

Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdowns on Body Mass Index of Primary School Children from Different Socioeconomic Backgrounds

- Ludwig Piesch

- Robert Stojan

- Till Utesch

Sports Medicine - Open (2024)

Prevalence and risk factors of obesity among undergraduate student population in Ghana: an evaluation study of body composition indices

- Christian Obirikorang

- Evans Asamoah Adu

- Lois Balmer

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Epidemiology

The causes of obesity: an in-depth review

- 10(4):90-94

- Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Dent Update

- Ali Alqarni

- Zulika Arshad

- Sherzad Abdulahad Shabu Shabu

- Mohammad F. Hashim

- Fatima S. Sabah

- INT J OBESITY

- Unurjargal Galindev

- Galindev Batnasan

- Nadya Shinta Nandra

- Steven Tandiono

- Kristin J Serodio

- Chaoyang Li

- M. P. H. James

- SEMIN REPROD MED

- Forum Health Econ Pol

- Albert J. Stunkard

- Thorkild I. A. Sørensen

- Fini Schulsinger

- Andrew M Prentice

- Susan A Jebb

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.8 Cause and Effect

Learning objectives.

- Determine the purpose and structure of cause and effect in writing.

- Understand how to write a cause-and-effect essay.

The Purpose of Cause and Effect in Writing

It is often considered human nature to ask, “why?” and “how?” We want to know how our child got sick so we can better prevent it from happening in the future, or why our colleague a pay raise because we want one as well. We want to know how much money we will save over the long term if we buy a hybrid car. These examples identify only a few of the relationships we think about in our lives, but each shows the importance of understanding cause and effect.

A cause is something that produces an event or condition; an effect is what results from an event or condition. The purpose of the cause-and-effect essay is to determine how various phenomena relate in terms of origins and results. Sometimes the connection between cause and effect is clear, but often determining the exact relationship between the two is very difficult. For example, the following effects of a cold may be easily identifiable: a sore throat, runny nose, and a cough. But determining the cause of the sickness can be far more difficult. A number of causes are possible, and to complicate matters, these possible causes could have combined to cause the sickness. That is, more than one cause may be responsible for any given effect. Therefore, cause-and-effect discussions are often complicated and frequently lead to debates and arguments.

Use the complex nature of cause and effect to your advantage. Often it is not necessary, or even possible, to find the exact cause of an event or to name the exact effect. So, when formulating a thesis, you can claim one of a number of causes or effects to be the primary, or main, cause or effect. As soon as you claim that one cause or one effect is more crucial than the others, you have developed a thesis.

Consider the causes and effects in the following thesis statements. List a cause and effect for each one on your own sheet of paper.

- The growing childhood obesity epidemic is a result of technology.

- Much of the wildlife is dying because of the oil spill.

- The town continued programs that it could no longer afford, so it went bankrupt.

- More young people became politically active as use of the Internet spread throughout society.

- While many experts believed the rise in violence was due to the poor economy, it was really due to the summer-long heat wave.

Write three cause-and-effect thesis statements of your own for each of the following five broad topics.

- Health and nutrition

The Structure of a Cause-and-Effect Essay

The cause-and-effect essay opens with a general introduction to the topic, which then leads to a thesis that states the main cause, main effect, or various causes and effects of a condition or event.

The cause-and-effect essay can be organized in one of the following two primary ways:

- Start with the cause and then talk about the effects.

- Start with the effect and then talk about the causes.

For example, if your essay were on childhood obesity, you could start by talking about the effect of childhood obesity and then discuss the cause or you could start the same essay by talking about the cause of childhood obesity and then move to the effect.

Regardless of which structure you choose, be sure to explain each element of the essay fully and completely. Explaining complex relationships requires the full use of evidence, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and anecdotes.

Because cause-and-effect essays determine how phenomena are linked, they make frequent use of certain words and phrases that denote such linkage. See Table 10.4 “Phrases of Causation” for examples of such terms.

Table 10.4 Phrases of Causation

| as a result | consequently |

| because | due to |

| hence | since |

| thus | therefore |

The conclusion should wrap up the discussion and reinforce the thesis, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of the relationship that was analyzed.

Be careful of resorting to empty speculation. In writing, speculation amounts to unsubstantiated guessing. Writers are particularly prone to such trappings in cause-and-effect arguments due to the complex nature of finding links between phenomena. Be sure to have clear evidence to support the claims that you make.

Look at some of the cause-and-effect relationships from Note 10.83 “Exercise 2” . Outline the links you listed. Outline one using a cause-then-effect structure. Outline the other using the effect-then-cause structure.

Writing a Cause-and-Effect Essay

Choose an event or condition that you think has an interesting cause-and-effect relationship. Introduce your topic in an engaging way. End your introduction with a thesis that states the main cause, the main effect, or both.

Organize your essay by starting with either the cause-then-effect structure or the effect-then-cause structure. Within each section, you should clearly explain and support the causes and effects using a full range of evidence. If you are writing about multiple causes or multiple effects, you may choose to sequence either in terms of order of importance. In other words, order the causes from least to most important (or vice versa), or order the effects from least important to most important (or vice versa).

Use the phrases of causation when trying to forge connections between various events or conditions. This will help organize your ideas and orient the reader. End your essay with a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your thesis. See Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” to read a sample cause-and-effect essay.

Choose one of the ideas you outlined in Note 10.85 “Exercise 3” and write a full cause-and-effect essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, a clear thesis, strong evidence and examples, and a thoughtful conclusion.

Key Takeaways

- The purpose of the cause-and-effect essay is to determine how various phenomena are related.

- The thesis states what the writer sees as the main cause, main effect, or various causes and effects of a condition or event.

The cause-and-effect essay can be organized in one of these two primary ways:

- Start with the cause and then talk about the effect.

- Start with the effect and then talk about the cause.

- Strong evidence is particularly important in the cause-and-effect essay due to the complexity of determining connections between phenomena.

- Phrases of causation are helpful in signaling links between various elements in the essay.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Band 8 Sample | Causes of Obesity

Essay topic

In some countries the average weight of people is increasing and their levels of health and fitness are decreasing. What do you think are the causes of these problems and what measures could be taken to solve them?

Band 8 essay sample

It is a fact that in some countries, the average weight of the citizens is shooting up while their fitness and health conditions are worsening. In my view this is mainly because of the food habits and modern lifestyle they follow. In this essay, I will examine these two factors and then propose a viable solution.

One of the foremost reasons for obesity is the consumption of unhealthy foods. Many people started to follow western food habits and eventually ended up eating high fat content foods like pizza and burger. Regular consumption of these fat rich foods will increase a person’s weight in a short span of time.

In addition to that, now-a-days, more and more people are living a sedentary lifestyle. They do not dedicate any time to do any kind of physical activity. As a result, they lose their resistance power. If this lifestyle continues then people will fall ill more frequently and lose their health permanently.

It is necessary that the government takes steps to open many sports complexes and fitness studios near residential communities. Most of the people who do not want to travel far to go to a sports center will be ready to use one if it is available nearby. In a study conducted by a popular newspaper 90% of the respondents said that they are willing to use the gym or any physical activity centers if they are within 3 kilometer radius.

To conclude, encouraging people to do more physical activities will not only improve their fitness and overall health but also help people to shed their weight.

(265 words)

Share with friends

Scan below qr code to share with your friends, related ielts tips.

Essay Writing Evaluation with model answer for band 8

Here’s a recently asked Essay Writing Question- Most countries...

Self-employment is better than a job in a company

Some people say that self-employment is better than a job in a company...

Essay Writing Evaluation for Band 8 with model answer

here’s one more Essay Writing Evaluation question.The question...

The following is an essay submitted by one of our students. In some countries,...

Band 8 Sample About The Advantages And Disadvantages Of English As A Global Language

The advantages provided by English as a global language will continue to...

Thank you for contacting us!

We have received your message.

We will get back within 48 hours.

You have subscribed successfully.

Thank you for your feedback, we will investigate and resolve the issue within 48 hours.

Your answers has been saved successfully.

Add Credits

You do not have enough iot credits.

Your account does not have enough IOT Credits to complete the order. Please purchase IOT Credits to continue.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y)

- v.6(12); 2010 Dec

The Obesity Epidemic: Challenges, Health Initiatives, and Implications for Gastroenterologists

Ryan t. hurt.

Dr. Hurt serves as an Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and as Assistant Clinical Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky.

Christopher Kulisek

Dr. Kulisek is a Gastroenterology Fellow in the Department of Medicine at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky.

Laura A. Buchanan

Dr. Buchanan serves as a Resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky.

Stephen A. McClave

Dr. McClave is a Professor of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky.

Obesity is the next major epidemiologic challenge facing today's doctors, with the annual allocation of healthcare resources for the disease and related comorbidities projected to exceed $150 billion in the United States. The incidence of obesity has risen in the United States over the past 30 years; 60% of adults are currently either obese or overweight. Obesity is associated with a higher incidence of a number of diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Consumption of fast food, trans fatty acids (TFAs), and fructose—combined with increasing portion sizes and decreased physical activity—has been implicated as a potential contributing factor in the obesity crisis. The use of body mass index (BMI) alone is of limited utility for predicting adverse cardiovascular outcomes, but the utility of this measure may be strengthened when combined with waist circumference and other anthropomorphic measurements. Certain public health initiatives have helped to identify and reduce some of the factors contributing to obesity. In New York City and Denmark, for example, such initiatives have succeeded in passing legislation to reduce or remove TFAs from residents' diets. The obesity epidemic will likely change practice for gastroenterologists, as shifts will be seen in the incidence of obesity-related gastrointestinal disorders, disease severity, and the nature of comorbidities. The experience gained with previous epidemiologic problems such as smoking should help involved parties to expand needed health initiatives and increase the likelihood of preventing future generations from suffering the consequences of obesity.

Obesity has been defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m 2 , with extreme obesity defined as a BMI greater than 40 kg/m 2 . Obesity is rapidly becoming the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, with obesity-related deaths projected to soon surpass deaths related to tobacco abuse. The incidence of obesity has doubled in the United States since 1960, with one third of the adult population currently obese. 1 , 2 Perhaps more alarming is the increase in overweight children; over the past 25 years, this rate has risen from 6% to 19%. 3 , 4

Numerous comorbid conditions have been associated with obesity, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. As a result of these comorbidities, the medical costs directly related to obesity are difficult to determine, but a conservative estimate would place the healthcare burden for obesity at approximately $150 billion per year in the United States. 4 – 6 The increase in mortality among obese individuals is likely related to comorbid conditions, rather than obesity per se; because of their various obesity-associated conditions, obese patients present challenging and complex issues in medical and surgical intensive care units. In the current debate over healthcare reform in the United States, no proposed solution can reasonably ignore or minimize the role that obesity plays with regard to economic and health consequences.

This article will give an overview of the epidemiology of obesity, provide measures of defining obesity, and discuss the impact of public health and environmental factors associated with the marked increase in obesity. Potential health initiatives that might be successful in preventing obesity and its associated consequences in future generations will also be discussed. Finally, this article will address the implications that obesity has for gastroenterologists.

Obesity Epidemiology

In 2001, the US Surgeon General released a report raising concerns about the growing obesity epidemic; this report was the first to note that obesity and obesity-related diseases might soon overtake smoking as the leading cause of preventable death in the United States. The number of overweight (BMI >25 kg/m 2 ) and obese (BMI >30 kg/m 2 ) adults has increased dramatically in recent years. 4 , 7 , 8 The rate of adults between the ages of 20 and 74 years who were classified as either obese or overweight has risen from 44.9% in 1960–1962 to 66.2% in 2003–2004, with similar trends for both men and women. 4 , 7 , 8 The rate of individuals who were overweight but not obese ranged between 31.5% and 33.4% over the same time period. 4 The major shift in the prevalence of obesity occurred between 1980 and 2004, effectively doubling in just 25 years (from 15.0% in 1980 to 32.9% in 2004). The number of people who were classified as extremely obese (BMI >40 kg/m 2 ) increased from 0.9% in 1960 to 5.1% in 2004. 4 , 7

More concerning than the rise in obesity among adults is the increased prevalence of obesity among chil-dren. 3 , 4 , 8 In the United States, the prevalence of obesity in children has tripled in just 30 years; not surprisingly, rates of dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes among children have shown a corresponding increase over the same time period. 9 In children, obesity is defined based on growth charts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For children aged 19 years or younger, obesity is defined as a weight at or above the 95th percentile for age; overweight children are those whose weight is between the 85th and 95th percentiles for age. In 1974, 5.1% of children were considered obese and 10.4% were considered overweight by these definitions. In 2008, 14.6% of children were considered obese. 4 , 8 , 10 , 11

The prevalence of obesity shows striking disparities with regard to race and ethnicity in both adults and children. 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 12 Between 1999 and 2004, the prevalence of obesity in non-Hispanic white adult women was 30.5%, compared to 39.8% in Mexican American women and 50.6% in non-Hispanic African American women. 4 Obesity rates in adult men showed no significant differences between ethnic groups. 4 The distribution of obesity among children aged 2–19 years with regard to race showed trends similar to those seen in adults. The prevalence of obesity was lower among non-Hispanic white children (13.9%) compared to non-Hispanic African American children (18.8%) and Mexican American children (19.7%). When gender and race were considered, significantly higher rates of obesity were seen in Mexican American boys (22.7%) than in non-Hispanic white boys (14.8%) or non-Hispanic African American boys (16.1%). Non-Hispanic African American girls had significantly higher rates of obesity (21.6%) than non-Hispanic white girls (13.0%).

While obesity is clearly a major public health issue in the United States, the increased prevalence of obesity is not limited to this country; indeed, obesity is now a global epidemic. Over the past 10 years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the increasing number of people who are overweight or obese, and attention is now being given to the global implications associated with this trend. In an analysis of the leading causes of global mortality and burden of disease, obesity and being overweight were among the top 10 causes for each. 13 The presence of a worldwide epidemic is suggested by the fact that in various regions of the world—North America, Central America, South America, most of Western Europe, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe—the majority of countries report that at least 40% of their population between the ages of 45 and 59 years are overweight or obese. 14 East Asian countries such as China, Japan, Vietnam, and India report lower rates of obesity, but the use of BMI alone may be problematic due to cultural and ethnic variability in adipose proportion and distribution. 15 In the latter geographic areas, rates of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are increased at BMIs below the WHO cutoff for being overweight (25 kg/m 2 ), a phenomenon most likely linked to proportionate increases in body fat in these populations. 16 , 17

Body Mass Index as an Estimate of Obesity and Mortality

Using BMI alone to define obesity has been problematic in some settings, given differences in genetics, fat distribution, and percentage of body adiposity among various countries. Because Asian populations have a higher proportion of body fat, for example, lower BMIs have been proposed to identify individuals in these populations who are overweight or obese. 14 , 15 , 18 A cross-sectional study looking at 3 different ethnic groups in Singapore (Chinese, Malays, and Indians) demonstrated the limitations of using BMI alone to estimate body fat percentage. Compared to white subjects, BMI underestimated body fat percentage in Chinese, Malay, and Indian subjects, with the error ranging from 2.7% to 5.6%. Furthermore, Asians had a higher risk of developing diabetes and CVD and had increased mortality at normal BMIs compared to other ethnic groups. 15 , 19

Further problems occur when epidemiologic studies use self-reported data to calculate BMI. Many of the larger international studies used to estimate the number of overweight and obese individuals in foreign countries have used surveys involving self-reported heights and weights. 4 However, the use of self-reported data often results in inaccurate estimations of weight and height and, subsequently, inaccurate BMI values. 4 A study of 16,000 individuals examined the validity of self-reported data for BMI calculation. 20 In this study, subjects were asked to report their weight and height, after which these estimates were compared to measured values. On average, BMIs in older individuals were 1 unit lower when calculated using self-reported values compared to BMIs calculated using measured values. Furthermore, this self-reporting bias worsened as true BMI values increased. In a subsequent study of 6,000 individuals in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Epidemiological Study (NHANES), researchers found that every 1-unit increase in BMI correlated with a 2-lb underestimation of weight. 21 When gender was considered, men were found to overestimate their weight by 5.0 lbs, and women underestimated their weight by 1.8 lbs, on average. In an earlier French study of 7,250 individuals, values for both self-reported weight and height were inaccurate. 22 Weight was significantly underestimated (by a mean of 0.54 kg among men and 0.85 kg among women). In contrast, height was significantly overestimated (by a mean of 0.54 cm among men and 0.40 cm among women). This combination of errors led to an underestimation of BMI— by 0.29 kg/m 2 in men and 0.44 kg/m 2 in women—and an underestimation of the rate of individuals who were overweight, by 13% in men and 17% in women. 22

Large cohort studies have shown that elevated BMI has been associated with an increased risk of future cardiovascular events. 23 , 24 In the largest of these studies, over 1 million adults were prospectively followed for 14 years, and the cause of mortality was evaluated. When other risk factors such as smoking were removed from the analysis, higher BMIs were associated with an increased risk of mor-tality. 23 Among white men and women with a BMI above 40 kg/m 2 , the relative risk (RR) for mortality was 2.58 and 2.0, respectively, compared to individuals with a BMI in the normal range (22.9–24.9 kg/m 2 ). In a similar group of African American subjects with BMIs above 40 kg/m 2 , no increase in mortality was seen compared to normal-weight controls. When death from cardiovascular causes was evaluated, men with BMIs greater than 40 kg/m 2 had an increased risk of mortality compared to their lean counterparts (RR=2.90; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.37–3.56).

In a subsequent large prospective cohort study of 527,265 US men and women between the ages of 50 and 71 years, researchers evaluated the association between BMI and death from any cause over a 10-year period (1996–2005). 24 Obesity was associated with an increase in mortality across all races and both genders. When individuals without preexisting cardiovascular conditions (including smoking) were isolated, overweight individuals still showed an increase in mortality. In a subcohort analysis of 50-year-old individuals who had never smoked, those who were morbidly obese (BMI >40 kg/m 2 ) had an increased risk of mortality (RR=3.82; 95% CI 2.87–5.08) compared to individuals with a BMI in the normal range (23–24.9 kg/m 2 ). While BMI is thus a useful predictor in some settings, how BMI compares to other anthropo-metric measurements in terms of accurately determining obesity, associated comorbid diseases, and respective mortality has been a topic of recent debate.

Central Adiposity

While the WHO still uses BMI to identify individuals who are overweight or obese, mounting evidence suggests that a pattern of central adiposity is more accurate in predicting obesity-related cardiovascular consequences. 25 – 33 In a large case-control study of 27,000 people in 52 countries, the correlation between myocardial infarction (MI) and either waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) or BMI was evaluated. WHR, waist circumference (WC), and hip circumference were individually associated with an increased risk of subsequent MI independent of other risk factors, including BMI. 27 When other cardiovascular risk factors and WHR were taken into account, there was no significant association between MI and BMI (odds ratio 0.98; 95% CI 0.88–1.09). The attributable risk for MI in the top 2 quintiles for WHR was 24.3% (95% CI 22.5–26.2%), compared to 7.7% in similar quintiles for BMI (95% CI 6.0–10%).

A recent cohort study examined the possibility of using WC, WHR, and BMI in conjunction with Framing-ham risk scores to predict coronary heart disease (CHD) and CVD mortality. A total of 4,175 Australian men who were free of CVD, CHD, diabetes, and stroke at baseline were followed for 15 years. 34 Baseline Framingham risk scores were calculated, and WC, WHR, and BMI measurements were taken. Initial Framingham scores were strong predictors of CVD and CHD deaths 15 years later. WHR was found to be an independent predictor of CVD and CHD deaths, and WC predicted CVD deaths. BMI did not predict mortality due to either CVD or CHD.

Two different meta-analyses evaluated measures of abdominal adiposity and their relationship to cardiac events, as well as their ability to predict the development of associated cardiac risk factors. In the first of these meta-analyses, BMI was compared to measures of central adiposity—including WHR, WC, and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR)—to determine the best predictor for development of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlip-idemia. A total of 10 studies met the inclusion criteria, and a total of 88,514 adult subjects (54% female) in 9 countries were included in the meta-analysis. 35 WHtR was found to be the best discriminator for development of all 3 cardiovascular risk factors, while BMI was the worst. The majority of the patients included in this study were from Asia and the Middle East.

The second meta-analysis, which examined the association between WC or WHR and the incidence of CVD, included 258,114 patients from 15 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective cohort studies. For every 1-cm increase in WC, the RR of a cardiovascular event increased by 2% (95% CI 1–3%). WHR and WC were both associated with an increased risk of future cardiovascular events (WHR RR=1.95, 95% CI 1.55–2.44; WC RR=1.63, 95% CI 1.31–2.04).

In comparing these different measures of central adiposity, it is important to note that technical limitations can make it difficult to measure WHtR consistently. Although visceral adipose stores can be directly measured by computerized axial tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, the high cost of these tests limits their applicability in large epidemiologic studies. 36 , 37 In contrast, WC and WHR can be measured easily in the clinical setting and are not limited by cost or technical issues.

Health Burden and Obesity-associated Diseases

Several studies have shown a relationship between elevated BMI and chronic medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity-related cancers. 38 – 40 Epidemiologic studies have also shown an association between adult obesity and premature death from all-cause mortality. 23 , 41 One study found that obesity was associated with a 7-year decrease in life expectancy for women and a 6-year decrease for men, which is similar to findings from past studies on smoking. 41 Furthermore, pediatric obesity is associated with many of the same cardiovascular risk factors as adult obesity, including hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and hyperlipidemia. 42

Conversely, other studies have shown reduced mortality due to cardiovascular causes in obese patients compared to lean controls. These latter studies appear to reflect an increase in the diagnosis and early treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in this high-risk group more so than a decreased incidence of obesity-related comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. 43 These clinically significant outcomes are not restricted to medical fields, but also complicate surgical outcomes. Postoperative complications occur more frequently in obese patients than lean controls, with an increased incidence of MI, peripheral nerve injury, wound infection, and cardiac arrest. 44

In addition to the potential impact on mortality, the overall morbidity seen in this growing patient population remains a key issue contributing to decreased quality of life in overweight and obese individuals. Impairment in activities of daily living—such as eating, dressing, and transferring to and from a bed or wheelchair—occur at a younger age in obese patients compared to nonobese controls. 45 If overall mortality decreases but the diagnosis and treatment of obesity-related conditions continue to increase, the cost of managing the obese patient population could be overwhelming.

While the hazards of obesity have long been known, the benefits of weight loss and exercise have only recently become more apparent. One study investigated 3,234 nondiabetic patients with elevated fasting glucose levels and randomly assigned them to treatment with placebo, metformin, or lifestyle modification (including weight loss and exercise). Metformin reduced the likelihood of developing diabetes by 31%, whereas lifestyle modification reduced the chance of developing diabetes by 58% (with weight loss >7%). 46 A subsequent meta-analysis examining the effect of weight loss on blood pressure showed that for every 1 kg of weight lost, blood pressure dropped by 1.1 mmHg systolic/0.9 mmHg diastolic. 47 Additional meta-analyses have also demonstrated improvements in cardiovascular risk factors related to weight loss. 48 Loss of only 1 kg was shown to be associated with improvement in serum cholesterol (–1.0%), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (–0.68%), triglycer-ides (–1.9%), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (+0.2%). Furthermore, loss of 5 kg was associated with a decrease in fasting plasma glucose levels of 18 mg/dL, an improvement similar to that achieved from treatment with current oral hypoglycemic agents. 48

Fast Food and Trans Fat