Gender-based violence and hegemonic masculinity in China: an analysis based on the quantitative research

- August 2019

- China Population and Development Studies 3(2)

- shangdong University,China

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Chenkai Niu

- Nanang Krisdinanto

- Merlina Maria Barbara Apul

- Theresia Intan Putri Hartiana

- ASIAN J WOMEN STUD

- Thomas William Whyke

- Malory Plummer

- Douglas Schrock

- Irene Padavic

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Advertisement

Gender-based violence and hegemonic masculinity in China: an analysis based on the quantitative research

- Survey Report

- Open access

- Published: 05 August 2019

- Volume 3 , pages 84–97, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Xiangxian Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6944-2948 1 ,

- Gang Fang 2 &

- Hongtao Li 3

13k Accesses

7 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Based on a survey implemented in a county in central China, the researchers found it is common for women to experience gender-based violence, especially violence at the hands of intimate partners. About half of men surveyed reported inflicting physical or sexual violence on their female partners. One in five men reported having raped a partner or non-partner woman. The physical, mental and reproductive health of the female and male respondents were found to be significantly associated with women’s victimization and men’s perpetration of intimate partner violence. Gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, is a construction of the social-ecological system. Four elements that are key to hegemonic masculinity are identified: male decision-making, male reputation, violence and heterosexuality. By positing the four elements as standards that define a “real man”, the domination of men over women is naturalized and legitimized. It is necessary to foster other non-violent and more equitable masculinities.

Explore related subjects

- Medical Ethics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the concept of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women arrived in China in the 1990s, surveys conducted by institutions like the Women’s Federation of China (Tao and Jiang 1993 ) and China Population and Development Research Center (Zheng and Xie 2004 ) have demonstrated that IPV is the most common form of violence against women in China. In the effort to eliminate the violence, Chinese scholars have taken into consideration a wide range of topics such as feminist law, ethnic minority issues, marriage markets and the imbalanced sex ratio in their studies of IPV against women (Gu 2014 ; Song and Zhang 2017 ; Dan 2018 ). While more and more international studies point to the strong connection between rigid hegemonic masculinities and violence against women (Schrock and Padavic 2007 ; Duncanson 2015 ; Cossins and Plummer 2018 ; Heilman and Barker 2018 ), this connection is neglected in China. Understanding gender based violence, especially IPV against women, from the perspective of hegemonic masculinities is thus the goal of our survey.

In May 2011, field research was carried out in a county in central China where the majority of the population lives in rural areas. By multiple stage random sampling, 67 communities were chosen and then 50 interviewees (25 women and 25 men) were randomly selected in each community. We had a response rate of 83.7%, with 1103 women and 1017 men aged 18–49 years completing the female and male questionnaires. Among the respondents, 97.8% of them are currently or have been partnered. The female and male questionnaires and research protocol were provided by the institutions that initiated and provided technical support for the survey. The implementation team made slight adjustments to the questionnaires based on Chinese and local contexts. Personal digital assistants were used to ensure that the responses of the interviewees were strictly confidential. Further information is provided in the Table 8 in Appendix (see Table 1 ).

2 Intimate partner violence against women

2.1 prevalence.

A breakdown of details reported by men follows in this paragraph. With respect to emotional violence, 28.6% of men reported deliberately frightening or intimidating their female partners, 22.4% reported insulting or deliberately making their partner feel bad about herself, and 14.2% reported deliberately degrading her in front of others. In terms of financial violence, the three most common items concerned men were forbidding women to find work or earn money (10.6%), male partners who spent their own earnings on alcohol and cigarettes although they knew their female partners could not support the family alone (7.7%), and forcing the female partner out of the place of residence (7.2%). In terms of physical violence, pushing or shoving was the most common type (32.8%), slapping or throwing things at women was second (29.8%), and striking women with fists was third (17.8%). With respect to sexual violence, the most common occurrence was the man insisting on sex when the female partner was unwilling, because the man felt entitled to sex with the woman who was his wife or girlfriend Footnote 1 (15.0%). In other cases the man physically forced his female partner to have sex (12.1%). Both of these behaviors are categorized as partner rape. In terms of the lifetime prevalence of partner rape, 14.3% of male respondents reported having perpetrated partner rape and 9.9% of female respondents reported being the victim. The items partner rape and males forcing female partners to watch phonography or perform sexual acts they do not want are classified as sexual violence. In addition, based on reports from women, the prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual violence inflicted by male partners during the female partner’s any of pregnancy were 13.1%, 3.6% and 5.5%, respectively.

Compared with to the instances of IPV documented above, men controlling the behavior of female partners was much more common. A total of 91.0% of men reported having done this at some point during their lives and 86.4% of women reported being controlled at some point. Among the specific items of men controlling the behavior of female partners, the most common is the male partner having more power to make big decisions (72.4%), followed by the male partner not allowing the female partner to wear certain items of clothing (45.8%) and getting angry if the female partner asks him to use a condom (40.3%).

Women often experience more than one type of IPV. Among women who reported experiencing emotional, financial, physical or sexual IPV, 43% of them experienced only one type, 30% experienced two types, 20% experienced three types and 8% experienced four types. Based on the reports of male perpetrators, the four percentage were 36%, 34%, 22% and 9%, respectively.

With respect to emotional, financial, physical and sexual IPV during the 12 months prior to the survey date, the prevalence of perpetrations reported by men were 19.1%, 10.5%, 14.4% and 7.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of victimizations reported by women were 10%, 6.9%, 6.8% and 3.3%, respectively.

2.2 Health consequences and seeking help

The statistics show the ratio of women injured from IPV was alarmingly high. Among 364 women who reported being victims of physical IPV, 40.7% (n = 148) suffered injuries including sprains, burns, knife cuts, bone fractures, lost teeth and other injuries, or had to receive medical care or be hospitalized. With respect to the severity of physical IPV injuries, 34.5% of 148 injured women were bedridden for a period of time, had to take work leave, or had to receive medical care. Beside these physical injures, IPV harmed women in other ways. Compared to women who never experienced IPV, the possibility that women who experienced IPV would suffer from mental and/or reproductive health problems was significantly higher (see Table 2 below).

Many women who are victims of IPV do not seek help. Among 364 women who reported experiencing physical IPV, 60% kept silent, only 6.6% reported the IPV to the police, 10% sought medical help and 36.8% told family members. Among 24 women who reported IPV to the police, 11 women did not report the details of how the police reacted to their reports, only one woman got the chance to open a court case, three women were sent away, and nine women were asked to compromise with their partners. Among the women who sought medical help, only half of them (n = 30) told the truth about how they had been injured. Of the 133 women who told family members about the IPV, nearly half of them (44.4%) were not supported by the family. Instead what they said was treated with indifference, or the family blamed the woman for causing the IPV or she was told to keep silent. In 24.8% of the cases, families were supportive, among other things, suggesting the women report the matter to the police. In 30.8% of the cases, the family’s reactions were ambiguous.

Women who claimed to be victims of rape or attempted rape by non-partners had similar experiences. Among 176 women who reported experiencing such violence, 72% kept silent and the rest sought help from family, hotlines, the local Women’s Federation or community committee, medical personnel or the police. Among 14 women who reported to the police, 8 women had cases opened. Among 30 women who told their families about being victims of sexual violence, nearly half of them (43.3%) were treated with ambivalence, 30% were not supported and 26.7% were supported.

3 Men’s childhood trauma and the rape of non-partners

3.1 childhood trauma.

Data for five kinds of childhood trauma were collected and are presented below. Hunger here refers to not enough food during childhood. Three behaviors are defined as neglect: living in different households (not with parents) at different times during childhood; parents did not look after the child due to alcohol or drug abuse; or the child spent nights outside the home and adults at home did not notice. Emotional violence includes the following behaviors of parents or teachers: scolding children for being lazy, stupid or weak; or humiliating children in public. Children who witness their mother being beaten by her husband or boyfriend are also victims of emotional violence. Physical violence refers to children being beaten by hard objects, being scarred by beatings, and being physically punished by teachers or principles. The following items are considered sexual violence against children: other people touching a child’s hips or genital areas, children being forced to touch themselves, children being frightened or threatened into having sex with others, or children having sex with men or women 5 years older than they are.

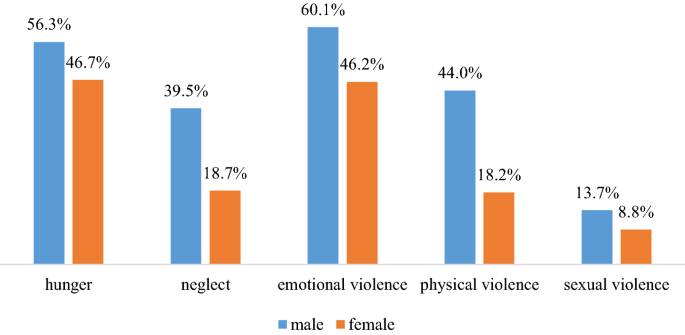

As Fig. 1 shows, many respondents experienced violence or adversity during childhood and male respondents were more likely than females to be involved (P < 0.0001). Besides the traumas listed in Fig. 1 , 24.7% of male respondents reported being bullied at school or in their communities during childhood, and 21.8% reported bullying others.

Source as Table 1

The prevalence of childhood trauma reported by male and female respondents.

3.2 Rape against non-partners

This study investigated men raping non-partner women. This included a man forcing or persuading a woman to have sex against her will, or a man having sex with a woman who was unable to give consent because of excessive alcohol or drug consumption. Gang rape, in which a woman was forced or persuaded to have sex against her will with more than one man, was also investigated. In order to present non-partner rape in context, data on partner rape are also listed in Table 3 . Although the majority of rapes are partner rapes, as indicated in Table 3 , women also face the risk of non-partner rape. One in five women reported being the victim of rape or attempted raped by non-partner men.

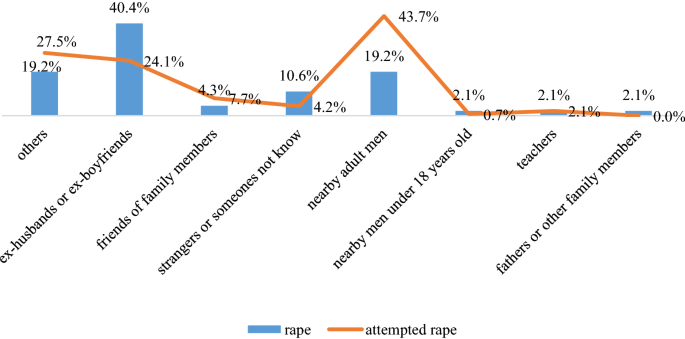

Regarding the motivation of rape, according to 222 male respondents who reported raping or attempting to rape non-partner women, the most common motivation was a feeling of male sexual entitlement. This included the man wanting to have the woman sexually, wanting to have sex, or wanting to show that he could have sex. Among these male respondents, 86.1% reported being driven by sexual entitlement. As well as sexual entitlement, 58% of the men reported being bored or seeking fun, 43% were angry or wanted to punish the woman, and 24% reported they had been drinking alcohol. Figure 2 indicates that some men’s sexual entitlement towards a women did not stop after the end of an intimate partner relationship. In fact ex-husbands and ex-boyfriends were the most likely perpetrators of non-partner rape. A look at the information reported by males who acknowledged having raped a woman, 91% of them committed rape for the first time between the ages of 15 and 29 years old, and 19.8% of the men raped more than one women.

Information on the perpetrators of 47 non-partner rapes and 145 attempted rape, as reported by women.

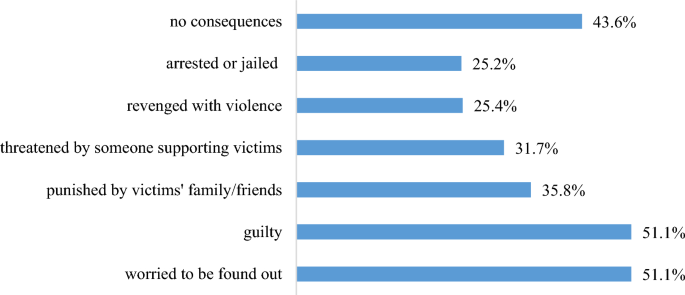

As shown in Fig. 3 , among 222 men who reported raping or attempting to rape non-partner women, nearly half of them reported suffering no consequences and only one quarter experienced legal repercussions. These findings correlate with the fact that about three quarters of women respondents kept silent after experiencing rape or attempted rape by non-partners.

The consequences of rape and attempted rape of non-partner women, as reported by male perpetrators.

4 Hegemonic masculinity and the risk factors of gender-based violence

4.1 hegemonic masculinity.

The views of the respondents on gender, femininities and masculinities were evaluated on several scales and Table 4 summarizes the specific elements of hegemonic masculinity. All except one of the items were supported by more than half of the male and female respondents.

There are two contradictions in Table 4 . First, while almost every male and female respondent agrees in the abstract principle that women and men should be treated equally, more than half of them also agree that men have more privileges than women when it comes to decision-making and sex life. The second contradiction is that, although more than 80% of male and female respondents agree men should share in the housework, more than half also consider looking after family members as women’s paramount duty. The gap between their attitudes and behaviors is greater for male respondents. While Table 4 shows that 92% of male respondents agree women should not be beaten in any situation, 44.7% of them reported inflicting physical IPV against women.

Why are there such striking contradictions? Table 4 reveals four key elements of hegemonic masculinity that provide at least part of the answer: (1) Men should decide important issues; (2) Men should be tough and use force if necessary; (3) A man should not beat a woman unless the woman challenges the man’s reputation; and 4) Men have to be heterosexual and it is in the nature of men to need sex more than women. By establishing these four elements above as a standard that defines “real men”, men’s domination over women is naturalized and legitimized. Such a definition of masculinity has negative ramifications for the notion of gender equality and can help to explain why there is such a large gap between male attitudes and behaviors. If hegemonic masculinity is the norm, gender equality does not mean that men and women should be treated the same, it means that men should treat women according to their “real” natures. In a world where men should decide important issues, be strong and use force if necessary, and need sex more than women, it becomes a simple matter for a man to justify forcing sex on an unwilling woman (i.e. raping a woman)—this is simply a manifestation of the natural order of things. While most people, men and women, agree that gender equality is a good thing in the abstract, widely accepted stereotypes of femininity, masculinity and gender differences lead instead to men dominating women and high levels of gender inequality.

Consistent with hegemonic masculinity which encourages men to be tough, use violence and not control sexual desire, male respondents reported a high likelihood of engaging in violent behavior and having unprotected sex. Nearly one in 5 men (18%) reported having participated in some form of violence including owning weapons, fighting with weapons, joining in gangs, being arrested and being in jail. Having unprotected sex was strikingly common. Among 856 men who reported having sexual experiences and answered the related questions, 82.7% of them reported never or seldom using condoms. Among 88 men who had had more than one sex partner during the last 12 month, 78.2% never or seldom used condoms.

IPV against women, one of the most common forms of violence engaged in by male respondents, also harms the male perpetrators. Compared with male respondents who never perpetrated IPV, Table 5 indicates that men who had perpetrated IPV were more likely to experience mental and reproductive health problems.

4.2 Risk factors for gender-based violence against women

Although poverty, low educational level, youth, and job pressures or unemployment are all commonly assumed to be risk factors associated with men perpetrating physical/sexual IPV against women, these are not confirmed by multiple logistic statistics. Table 6 presents the factors that increase the likelihood of a male perpetrating physical IPV against women. These are generational transmission of domestic violence and male domination, a man’s involvement in other types of violence, alcohol abuse, multiple sexual partners and quarrels between partners.

A comparison of Tables 6 and 7 shows that both the likelihood of men perpetrating physical and sexual IPV against women, and the likelihood of men raping partner and non-partner women were increased by three common risk factors: trauma during childhood, involvement in other types of violence, and having multiple sexual partners. Specifically, having experienced sexual violence during childhood and having low support for gender equality were found to be associated with men inflicting sexual violence.

5 Conclusion

Gender-based violence perpetrated by men is constructed within the social-ecological system, which is composed of four concentric circles. The innermost circle is the individual, and for this circle research identifies several risk factors including childhood trauma, involvement in other types of violence, alcohol abuse, multiple sexual partners and low support for gender equality. In the second circle consisting of relationships, male domination within the family, couples quarreling, generational transmission of ideas about unequal gender relationships and the commission of male violence against both females and children are found to be risk factors. The third circle consists of community, and risk factors in this circle are correlated to community responses to IPV and sexual assault against women, and people’s consciousness of and attitude towards the laws and regulations governing IPV and VAW. The outermost circle consists of social norms and the political and economic environments, and researchers find out that in China, social values, social policy, and laws and regulations are permeated with ideas of rigid hegemonic masculinity, and serve to perpetuate gender-based violence, especially IPV against women (Wang et al. 2013 ; Deng and Shi 2018 ).

Based on our findings, we have the following core recommendations: (1) The whole society including governments, mass media, communities and schools should recognize rigid hegemonic masculinity and work to eliminate this type of masculinity which perpetuates gender-based violence, especially IPV against women, encouraging instead non-violent masculinities based on gender equality. (2) The laws and regulations to stop IPV against women should be strengthened and stronger implementation and evaluation are needed to ensure that men are unable to commit violence against women with impunity. (3) Governmental agencies and NGOs should provide professional services for abused women, engage men in programs of violence prevention and strive to eliminate childhood trauma for boys and girls.

A female respondent received a different question asking if she had had sex she did not want with a male partner because she was afraid the man might become violent or hurt her if she refused.

Cossins, A., & Plummer, M. (2018). Masculinity and sexual abuse, explaining the transition from victim to offender. Men and Masculinities, 21 (2), 163–188.

Article Google Scholar

Dan, S.-H. (2018). New development of female jurisprudence studies: An overview of masters and doctoral theses on female jurisprudence from 2006 to 2015. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 27 (3), 119–128.

Google Scholar

Deng, Y.-X., & Shi, F. (2018). Dormitory labor regime and male workers: A study on Foxconn factory. Journal of Hunan University, 32 (5), 128–135.

Duncanson, C. (2015). Hegemonic masculinity and the possibility of change in gender relations. Men and Masculinities, 18 (2), 231–248.

Gu, X.-B. (2014). Gendered suffering-middle-aged Miao women’s narratives on domestic violence in Southwest China. Journal of Zhejiang Gongshang University, 28 (4), 3–21.

Heilman, B., & Barker, G., (2018). Masculine norms and violence: Making the connections. https://promundoglobal.org/resources/page/10/?type=reports . Accessed February 12, 2019.

Schrock, D. P., & Padavic, I. (2007). Negotiating hegemonic masculinity in a batterer intervention program. Gender and Society, 21 (5), 625–649.

Song, Y.-P., & Zhang, J.-W. (2017). Less is better? The effects of imbalance in sex ratio in the marriage market on domestic violence against women in China. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 26 (3), 5–15.

Tao, C.-F., & Jiang, Y.-P. (1993). An overview of Chinese women’s social status . Beijing: Chinese Women Publisher.

Wang, X. -Y., Jiao, D. -P., & Yang, L. -C. (2013). Masculinities and gender-based violence in transitional China. China Office of UNFPA.

Zheng, Z. Z., & Xie, Z. M. (2004). Migration and rural women’s development . Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The research is funded by China Office of United Nation Population Fund, technically supported by Partners for Prevention, an Asia–Pacific programme jointly established by United Nations Development Programme, United Nation Population Fund, UN women and UN Volunteers, and conducted by the Anti-Domestic Violence Network of China and the Beijing Forestry University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, 300387, China

Xiangxian Wang

Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, 100083, China

China Women’s University, Beijing, 100101, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xiangxian Wang .

See Table 8 .

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wang, X., Fang, G. & Li, H. Gender-based violence and hegemonic masculinity in China: an analysis based on the quantitative research. China popul. dev. stud. 3 , 84–97 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-019-00030-9

Download citation

Received : 31 May 2019

Accepted : 26 July 2019

Published : 05 August 2019

Issue Date : October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-019-00030-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gender-based violence

- Intimate partner violence

- Hegemonic masculinity

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Probing Causes of Violence Against Women in China

- 24 June 2011

HUNAN PROVINCE, China — A lively workshop session on gender equality started with brainstorming of commonly used Chinese idioms describing a good man.

He should have a back like a tiger and a waist like a bear.

He does not shed tears until his heart is broken.

He stands firm amid adversities.

On the subject of a good woman, more hands shot up.

She should behave in a sweet and helpless way.

She should be caring and affectionate.

She should be a good wife and loving mother.

Of the more than 40 men and women who attended the interviewers' training last spring, half were university students from all over China, and half of them were recruited locally from various professions. Most of them are in their 20s, joined by a few older retirees. The training -- which included an innovative use of new technology qualified them to undertake innovative field data collection on men, gender equality and violence against women.

The fieldwork is part of the research on masculinities – the qualities generally ascribed to men – and their connections to violence against women.

Generating new perspectives on masculinities

Equipped with knowledge of complicated issues surrounding violence and gender norms, the interviewers will seek views from both men and women in this Hunan Province city. China is one of seven countries included in a research project on gender-based violence in the Asia Pacific region. Led by Partners for Prevention, a regional programme supported by UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women and UN Volunteers, the research will generate new analysis on masculinities and violence in the region and is expected to improve measures to prevent and respond to violence against women.

“The research is the most strict one in terms of the ethics standard, and the most comprehensive one with lots of hard-to-ask questions,” said Professor Wang Xiangxian, one of the key Chinese researchers dedicated to this project. For both men and women, the questionnaire includes probing some of the most private aspects of their lives, including sexual relations, violence, intimate relationships and drug use. The greatest challenge the research team faces is how to ask these questions in the most appropriate way and to get honest answers without betraying the privacy of the interviewees.

Using technology to make hard-to-ask questions easier

The trendy Apple portable iTouch provides an innovative solution. All the questions are programmed in a special application that can be installed in an ITouch that will serve as a personal digital assistant for the interviewer. Instead of holding printed questionnaires in hand and going through each question face-to-face with the interviewee, the interviewer will guide the subject to answer the questions directly on the iTouch. The questions are even recorded so that those who can’t read will hear the questions with headsets and key in their answers. The use of the PDAs aims to avoid embarrassment, to allow self-reporting of violent acts such as physical abuse and rape, and to ensure maximum protection of privacy.

The field work will last for over a month in the UNFPA-supported pilot site. Already the project has made some important breakthroughs, ranging from village level awareness-raising to the issuing of city-level legislation on violence against women. The findings from the research will bring valuable insights to all stakeholders involved to formulate effective actions to prevent and respond to violence against women by taking into account of both men and women. The results will also be shared with Chinese experts involved in the process of drafting the Anti-Domestic Violence Law of China

--- Gao Cuiling, UNFPA China

Seeking Help for 'Private Matters' in China

LIU YANG CITY, China —" I feel happy with my life now. I believe it is going to be better," says 32-year-old Xiao Hui, who no longer fears the shadow of domestic violence.

Xiao Hui and her husband were schoolmates. After leaving high school, they both went to work in Guangdong Province as migrant workers for a few years, and they fell in love. They returned to Duzheng Village to get married.

With the arrival of their daughter seven years ago, Xiao Hui stayed at home while her husband worked with construction companies nearby. With one more person to feed, the couple began to quarrel about money. One day, her husband returned Xiao Hui’s complaints by forcefully shoving her to the bedside. "He treated me with no respect. He hurt me as much as if he had beaten me," said Xiao Hui.>

Xiao Hui did not just worry and cry after the incident. She remembered seeing the anti-domestic violence posters and performances near the village and she mustered up the courage to ask Ms. Zu of the Women’s Committee whether her ‘private matter’ would qualify for some sort of formal intervention. To her surprise, Ms. Zu organized a mediation session with the couple and their parents. "My husband was told if he did not stop, he would have to face the consequences," Xiao Hui recalled.

Xiao Hui thought the mediation really worked. "My husband would have started beating me if he did not get the formal warning," Xiao Hui believes.

Duzheng Village is one of the seven local villages in Liuyang that have organized intensive community activities to encourage villagers to speak out and seek support whether violence occurs in or out of their houses. It is part of a UNFPA-supported pilot initiative aiming at setting up a multi-sectoral model on violence against women. "Our volunteers spread messages on violence when entertaining big crowds of people, even at weddings and funerals," said Ms. Zu. Every household got a letter on domestic violence and there were displays in the village on where to get support when violence happens.

According to the Violence against Women: Facts and Figure 2010 compiled by UNFPA China and a Chinese NGO Andi-Domestic Violence Network, "one of the greatest challenges to addressing this is that women usually seek help from informal networks such as family, and neighbours, or never tell anyone of the violence". In China, where the culture of "washing your dirty linen at home" is extremely strong, the village campaign on violence makes it possible for many women like Xiao Hui to speak up and seek help for what is usually seen as ‘private matters.’

Related Content

“Innovators, entrepreneurs and catalysts for transformation”: Three youth…

Explainer: Why are gender equality and reproductive rights essential for peace?

79th session of the united nations general assembly.

We use cookies and other identifiers to help improve your online experience. By using our website you agree to this, see our cookie policy

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Chinese intersectionality

DOI link for Chinese intersectionality

Click here to navigate to parent product.

This chapter proposes to establish a new theoretical framework of Chinese intersectionality, to include state, market and cultural discourses in the gender analysis matrix both for gender-based violence research and Chinese feminism. It provides some questions to explore the possibilities of establishing a Chinese intersectionality theory within current feminist scholarship. The chapter argues that different types of violence do not have clear boundaries, as many quantitative studies demonstrate, and a single violent incident may include all types of violence. It presents a detailed discussion of how the three characteristics of post-socialist China – the state, market, and cultural hybridity – are entangled with women's images, studies of violence against women, and Chinese feminism and women's studies, and how they formulate a new framework of Chinese intersectionality as three important macro-political factors and discourses influencing young people's experiences of dating violence.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The Intersection of Gender and Other Social Institutions in Constructing Gender-Based Violence in Guangzhou China

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada [email protected].

- 2 The University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

- 3 University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

- 4 Simon Fraser University, British Columbia, Canada.

- PMID: 25411235

- DOI: 10.1177/0886260514556109

Although violence against women is illegal in China, few studies have been published concerning this issue in that country. This article is part of a program of research undertaken in one province of China. The purpose of this study was to understand, from the perspectives of women who have experienced gender-based violence (GBV), the intersections of gender and other social institutions in constructing GBV in Guangzhou, China. The research question was as follows: For women who have been unfortunate enough to be with a partner who is willing to use abuse, how is gender revealed in their discussion of the experience? Women participants (N = 13) were all over the age of 21, had experienced some form of abuse in an intimate relationship, and had lived in Guangzhou at least for a year prior to data collection. They had a variety of backgrounds and experiences. The majority spoke of GBV as common. "Saving face" was connected to fear of being judged and socially stigmatized which had emotional as well as material consequences. Eight situations in which social stigma existed and caused women to lose face were identified. Gender role expectations and gendered institutions played a part in family relationships and the amount of support a woman could expect or would ask for. The women in this study received very little support from systems in their society. A high proportion (67%) revealed symptoms of mental strain, and three talked about having depression or being suicidal. The results are discussed in terms of identifying the mechanisms by which systems interlock and perpetuate GBV.

Keywords: alcohol and drugs; cultural contexts; domestic violence; domestic violence and cultural contexts.

© The Author(s) 2014.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Stigma, shame and women's limited agency in help-seeking for intimate partner violence. McCleary-Sills J, Namy S, Nyoni J, Rweyemamu D, Salvatory A, Steven E. McCleary-Sills J, et al. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(1-2):224-35. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1047391. Epub 2015 Jul 8. Glob Public Health. 2016. PMID: 26156577

- Factors Mediating the Relationship Between Intimate Partner Violence and Cervical Cancer Among Thai Women. Thananowan N, Vongsirimas N. Thananowan N, et al. J Interpers Violence. 2016 Feb;31(4):715-31. doi: 10.1177/0886260514556108. Epub 2014 Nov 6. J Interpers Violence. 2016. PMID: 25381266

- Community economic status and intimate partner violence against women in bangladesh: compositional or contextual effects? VanderEnde KE, Sibley LM, Cheong YF, Naved RT, Yount KM. VanderEnde KE, et al. Violence Against Women. 2015 Jun;21(6):679-99. doi: 10.1177/1077801215576938. Epub 2015 Apr 6. Violence Against Women. 2015. PMID: 25845617

- Intimate partner violence and the justice system: an examination of the interface. Jordan CE. Jordan CE. J Interpers Violence. 2004 Dec;19(12):1412-34. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269697. J Interpers Violence. 2004. PMID: 15492058 Review.

- An examination of the factors related to dating violence perpetration among young men and women and associated theoretical explanations: a review of the literature. Dardis CM, Dixon KJ, Edwards KM, Turchik JA. Dardis CM, et al. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015 Apr;16(2):136-52. doi: 10.1177/1524838013517559. Epub 2014 Jan 10. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015. PMID: 24415138 Review.

- 'Violence exists to show manhood': Nepali men's views on domestic violence - a qualitative study. Pun KD, Tjomsland TR, Infanti JJ, Darj E. Pun KD, et al. Glob Health Action. 2020 Dec 31;13(1):1788260. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1788260. Glob Health Action. 2020. PMID: 32687002 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Grants and funding.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Canada

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources, other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 05 January 2024

Not all men: the debates in social networks on masculinities and consent

- Oriol Rios-Gonzalez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8219-7393 1 ,

- Analia Torres 2 ,

- Emilia Aiello ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0005-6501 3 ,

- Bernardo Coelho 2 ,

- Guillermo Legorburo-Torres ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0088-9335 1 &

- Ariadna Munte-Pascual 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 67 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

4007 Accesses

1 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Evidence shows the role men can have to contribute to the prevention of non-consensual relationships and gender violence, mainly fostering educational and social strategies which strengthen egalitarian male models that take consent as a key aspect in their sexual and affective relationships. In this regard, social networks show the existence of discourses that reinforce these male models. However, there is a gap in the analysis of how the previously mentioned discourses on consent are linked to men’s sexual satisfaction. The present study deepened into this reality by analysing messages on Reddit and Twitter. Drawing on the Social Media Analytics (SMA) technique, conducted in the framework of the European large-scale project ALL-INTERACT from the H2020 program, the hashtags notallmen and consent were explored aimed at identifying the connections between masculinities and consent. Furthermore, three daily life stories were performed with heterosexual men. Findings shed light on the relevant positioning of men about consent as a key message to eradicate gender-based violence; in parallel, they reveal the existence of New Alternative Masculinities that have never had any relationship without consent: they only get excited by free, mutual and committed consent, while repulsing unconsented or one-sided relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

The gendered dimensions of the anti-mask and anti-lockdown movement on social media

Social media construction of sexual deviance in Hong Kong: a case study of a Facebook discussion

Discursive representations of sexual minorities in China’s English-language news media: a corpus-based study

Introduction.

There are several myths about heterosexual men’s sexual interests and desires, which are based on hoaxes and not scientific evidence. One salient example of them refers to the idea that all heterosexual men always have sexual desire for women, regardless of their lack of consent. However, research has evidenced that this statement is not real and there are men’s groups and men who are positioned against relationships without consent (Kaufman 2001 ). Concerning the approach to gender issues, social media is given a relevant role in their visibility. In fact, studies on the impact of social media have illustrated the effects on the reality that messages posted on virtual networks can have (Fu and Chau 2014 ; Zheng and Yu 2016 ). For instance, the gendered trolling of women was analysed by Pillai and Ghosh ( 2022 ) for its consequences on women.

The research questions that drive this study are: Do men take a stand in favour of consent, in their personal sexual relationships and in interaction with others’ behaviours? Do men desire consensual relationships and reject non-consensual interactions? In the present article, we pay attention to this issue by analysing discourses and messages which have emerged on two social networks: Twitter and Reddit. Thus, we have mainly focused on the discussions around the hashtags #NotAllMen and #Consent, which show the positioning of men and women against gender-based violence and its connection with consent. Furthermore, three life stories of men were conducted aimed at deepening this issue: this fieldwork illustrates different dimensions concerning interviewed men’s desire for consenting relationships that have not been identified in the analysis of social media.

This article is divided into four different sections. Firstly, the theoretical framework of the study will be introduced; secondly, a literature review will highlight some of the latest research relevant to our study, regarding scientific literature on masculinities, consent in affective relationships, and the relevance of social networks for strengthening the transformation processes. Thirdly, mixed methods employed in the article are described, as well as how the data analysis has been carried out. Fourthly, findings obtained through social media analytics and life stories are summarised. Lastly, a brief discussion of the results is elaborated.

Theoretical framework

This study is primarily situated within the theoretical framework and research line of preventive socialisation of gender-based violence, intersectionality and social impact research. The former examines how interactions with media and other people can help overcome violence (Gomez 2015 ; Puigvert 2014 ; Salceda et al. 2020 ). The central thesis revolves around the cultivation of an alternative socialisation that directs our focus, attraction, and decision-making toward egalitarian and dialogic relationships. Within this framework, the analysis of New Alternative Masculinities (NAM) is found and conceptualised: these NAM behaviours, characterised by a fusion of egalitarian values and attractiveness in the same boys and men, are to be promoted and endorsed within society. Shifting attention to such alternative attitudes could prove pivotal in reshaping preferences towards men who are not violent or dominant across various relationship dynamics.

Second, intersectionality is another theoretical approach that has been widely employed to comprehend gender inequalities directly or indirectly connected with masculinities (Crenshaw 1989 ). Following Crenshaw’s works ( 2013 ), intersectionality pays attention to how hierarchical power relations contribute to maintaining discriminatory practices which are linked to structural variables such as race, social class and gender. This is particularly relevant to deepening the situation of social exclusion or discrimination lived by certain vulnerable groups. In this vein, categories of class, race and sexuality can also reinforce patriarchy and men’s privilege, strengthening the legitimacy of dominant models of masculinity that uphold positions of power (Christensen and Jensen 2014 ). Conversely, the theory of the Dialogic Society demonstrates that these kinds of unequal power alignments are being contested by social movements and individuals who claim and build more egalitarian relations (Flecha 2022 ).

Last, social transformation processes are often elucidated by social impact-focused theories, illustrating how research can serve as a valuable tool for bringing about significant societal changes by highlighting realities that contribute to a better world. These realities, like the ones explained in this paper, become social creations thanks to co-creation processes engaging citizens and promoting an egalitarian dialogue with researchers (Flecha 2022 ; Aiello and Joanpere 2014 ). In this regard, there are several analyses that show the role of social science research in generating experiences that reduce or eradicate inequalities. For example, the successful action approach, which arises from European research, provides the definition of successful educational actions that are improving coexistence and academic results in schools of different parts of the world (Flecha 2014 ; Flecha and Soler 2014 ). In relation to gender, Judith Butler ( 2003 ) clearly states that feminism can lead to social transformations of gender relations. Feminism, egalitarian men’s groups and other identity movements are contributing to create new social relations shaping an alternative socialisation which strongly rejects non-consensual relationships (Soler-Gallart and Flecha 2022 ).

Literature review

The review of scientific literature is divided into two sections. Firstly, a review of contributions from men’s studies concerning consent is carried out. Secondly, the role of social media for social transformation is analysed, paying particular attention to those campaigns which emerge in the context of men’s engagement in initiatives that promote consent and gender equality.

Men and consent

About the contributions in the field of men’s studies, impactful and a significant amount of literature pays attention to the relevance of implementing interventions addressed to men and boys to sensitise them on the importance of consent in intimate relationships. For instance, investigations which examine the impact of these interventions stress the relevance to articulate “positive masculinities” which are centred on the performance of healthy behaviours directly linked to male gender identity (Carline et al. 2018 ; Orenstein 2021 ). However, other contributions call into question the capacity of these actions to transform hegemonic masculinities (Jewkes et al. 2015 ), a typology of masculinities which still has an important influence in men’s behaviours (Connell 2012 ; Flecha et al. 2013 ; Guarinos and Martín 2021 ; Padros-Cuxart et al. 2021 ).

There is another body of literature which examines the characteristics of some strategies addressed to men aimed at raising awareness about consent in sexual and affective relationships. One example of these strategies is those which are launched at university campuses where campaign posters are placed in strategic spaces, such as toilets, student unions, and pubs. These campaign posters include key messages related to consent, such as ‘Can’t answer? Can’t consent – sex without consent is rape’ (Carline et al. 2018 ). However, there is a significant academic debate about the impact of these informative strategies on men, particularly because several limitations are identified linked to how tailored these strategies are to local and regional realities where they are implemented (Casey and Lindhorst 2009 ).

From another perspective, there are analyses of consent linked with the construction of masculine models. For instance, Beres ( 2010 ) stipulates young men hold ideas about consent as a tacit understanding; therefore, they used to employ statements such as ‘you get a vibe’ and ‘just feel it in the air’. On the other hand, other conceptualisations relativise sexual abuses using sentences such as ‘sort of just happens’, thus diminishing the importance of consent in intimate relationships. In fact, studies on socialisation related to this type of relationship show how this is strongly influencing social imaginaries about women, who are sometimes perceived as sexual gatekeepers.

Recent developments in men’s studies have introduced alternative conceptualisations, different from the above-mentioned, which provide new insights on the positioning of men concerning consent. Thus, the New Alternative Masculinities’ approach (NAM) (Ríos-González et al. 2021 ) pays attention to the active positioning against gender-based violence and abusive relationships. However, one of the distinctive elements of this approach concerns how New Alternative Masculinities men look for relationships that combine freedom, equality, and passion, so desired consent from all parts is necessary. The last findings in this field illustrate a distinction between traditional and alternative models of masculinities. In the first case, there are the Dominant and the Oppressed models. The Dominant Traditional Masculinities refer to the typology of masculinity, which exercises violence and domination. The Oppressed Traditional Masculinities are not aggressive but become passive in front of discrimination and inequalities (Ríos-González et al. 2021 ). In addition, the former is socially perceived as attractive, and the latter as unattractive (Puigvert et al. 2019 ).

Since the beginning of the study of men and masculinities, outstanding scholars like Connell have identified the pressure that men experience to follow a Dominant model, which is reinforced by a social coercive discourse that breaks the relationship between beauty, goodness and truth and gives social value to men who not only do not improve relationships but actually make them worse with their disdain and power (Puigvert et al. 2019 ). Nonetheless, research suggests that New Alternative Masculinities become an alternative to this double standard generated by traditional models because they combine a clear positioning in front of gender-based violence and awaken desire with their actions (Flecha et al. 2013 ).

In Butler’s terms ( 1990 ), gender exists because it is socially performed, which means that the construction of gender patterns has a relevant role in shaping people’s identities. She stated heteronormative matrix is also conditioning men’s socialisation, pushing them to reject feminine behaviours and reproducing hegemonic values. Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, the New Alternative Masculinities’ approach confirms the existence of an alternative socialisation which confronts this normativity promoting more diverse masculinity models away from the dominant ones.

Social media and transformation

The second facet that this literature review explores is the role of social media in current societies. In this respect, social media can be employed as an instrument that, on one hand, fosters Islamophobia, chauvinism, and homophobia (Awan 2016 ; Leppanen et al. 2016 ); or, conversely, could become a tool to engage citizenship in transformative actions with a significant social impact (Roth-Cohen 2022 ; Soler-Gallart and Flecha 2022 ; Pulido et al. 2018 ; Redondo-Sama et al. 2021 ). However, the existence of a coercive dominant discourse, as previously explained, present in society and expressed as well in social networks such as Instagram or Twitter, is linking attractiveness with violent and risky behaviours (Villarejo et al. 2020 ). This discourse is influencing young people’s socialisation, making them more vulnerable to affective and sexual relationships where this connection emerges. More attention will be paid to all these aspects, which are under the purpose of the research we have conducted.

More linked with the research we have performed here, there are analyses about social media and social transformation, which have evidenced that virtual networks are accelerating activism communication and are making the work of social movements more visible (Poell 2014 ; Maaranen and Tienari 2020 ). This is evident in the experiences on social media driven by specific campaigns and hashtags. For instance, Zheng ( 2020 ) analyses #NotAllMen as a hashtag that has reached a wide audience, although she insists on the fact that several feminist voices have been very critical of it. They argue that it is only restricted to harassers, rapists, batterers, and perpetrators of sexism, concluding that more distinction is needed to properly understand the role of men in the prevention of gender-based violence.

There is another campaign and hashtag strongly linked to the involvement of men in gender equality and violence prevention, #HeForShe, which has been promoted by the actress Emma Watson since her discourse at the United Nations Headquarters in 2014. As it was demonstrated in Samarjeet’s ( 2017 ) analysis, this hashtag encouraged many male celebrities to express their solidarity with women and contributed to creating global rhetoric on the relevance of involving men in gender equality. After this impact, the United Nations created a global social movement that is enabling the implementation of a set of actions addressed to question gender inequalities and stereotypes from a male standpoint.

While covering these issues, there is a scientific gap on the rejection of non-consent and, complementarily, desire towards consent. Moreover, no studies have analysed alternative interactions from men regarding consent. This manuscript endeavours to address the existing void by analysing online dialogues and engaging with a sample of heterosexual men who are actively participating in an egalitarian men’s movement. The evidence found in this study, and presented in this paper, seeks to make a meaningful contribution to the transformation of gender roles and the engagement of egalitarian men in consensual relationships. This transformation is facilitated through the promotion of New Alternative Masculinities, fostering change in both online and face-to-face interactions.

Materials and methods

This research started with the concern of what would the debates on social media be regarding men and consent. More specifically, there was an initial hypothesis that there is growing criticism of non-consent and towards men who perpetrate or reinforce it, while, and most importantly, there is a growing active involvement of men in opposing gender-based violence and only seeking relationships based on consent.

This study is framed within the ALL-INTERACT project from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (ALL-INTERACT, 2020– 2023 ). This project aims at Widening and diversifying citizen engagement in science, grounded on the perspective of the social impact of research.

Our study follows a Communicative orientation (Redondo-Sama et al. 2020 ). This Communicative Methodology aims not only to analyse social realities but also to find solutions that can help overcome injustices and inequalities, with the aim of informing social transformation through research. This methodological approach focuses above all on breaking the hierarchy between researcher and researched, breaking with the idea of interpretative unevenness. Analyses conducted under this methodology are based on the creation of scientific knowledge through egalitarian dialogue, with the primary goal of reducing social inequalities. Next, the data-collection techniques are summarised, that is, the Social Media Analytics and the communicative daily life stories. Their design, implementation and analysis follow a communicative orientation.

First, the Social Media Analytics (SMA, hereinafter) carried out is explained. Reddit and Twitter were the social media platforms chosen for the analysis of posts, comments, and debates given their public dialogue nature, where any user can join an open conversation, read and participate. Precisely, the search unit we employed was NotAllMen and Consent , in the form of hashtags and keywords; these words were searched separately and combined. The objective was to see what people, not only men, talk about regarding consent and men. We initially analysed all messages that contained those words and additionally explored the threads where such messages were inserted to include reactions and responses.

Twitter was openly explored: according to the criteria described above, over two thousand Twitter messages -including the initial tweet, answers and retweeted messages- were read and analysed. On Reddit the search was centred on the following subreddits with a connection to the research purpose and which were obtained from the work of ALL-INTERACT. This European project funded this study and had two focus fields: the subreddits Feminism , Feminisms , Bisexual , FeMRADebates and PurplePillDebate related to gender issues; the subreddits ApplyingToCollege , Education , Science , Teachers and Teaching were focused on education. We were able to utilise this data extraction and analyse its content in search for findings that met our research goals in two fields of great importance for the issue of consent: gender and education forums with great participation. Excel files containing messages from those subreddits added up to a total of 58,114 posts and comments, which were filtered to analyse those that included the target words and hashtags NotAllMen and Consent . The messages finally included in the results section were selected because they answered the purpose of the research. For data protection purposes, no literal excerpts will be presented, but rather descriptions and paraphrases of such comments.

To introduce the communicative daily life stories, it is important to note that our goal was not to provide a comprehensive and representative analysis of men’s perspectives about consent, but rather to complement the SMA to fill the gap that social platforms did not incorporate in filling with statements from egalitarian men who may reject relationships not based on mutual consent and who would be most excited by enthusiastic consent. To achieve that, the inclusion criteria were men from an intentional sample who had participated in groups of men who discuss relationships that combine egalitarian values with desire and passion. Thus, the research team contacted a Spanish men’s movement familiarised with scientific articles on consent and new alternative masculinities that they regularly debate. After being contacted, three heterosexual Spanish men between 35 and 45 years with a long trajectory on the movement and with significant knowledge of the aforementioned topics of age linked to a network of men who debate New Alternative Masculinities and the overcoming of gender-based violence were selected and then interviewed.

The technique chosen was the communicative daily life stories, where a specific topic is discussed based on the life experiences lived, which are put to reflection with the scientific evidence on men and consent that the researcher shares. During the conversation, the participants were asked to share insight about excitement and consent: they talked about their level of satisfaction towards consensual encounters and the way they felt about relationships where consent or reciprocity cannot be ensured. After analysing the interviews, the most repeated results were categorised considering the above-mentioned hypothesis.

The results were analysed following the communicative orientation. An initial general category, “Effects on consensual relationships”, was drawn from the literature reviewed and the research objective. Then, the transformative and exclusionary dimensions were differentiated: the exclusionary dimension includes the debates and comments that perpetuate non-consent relationships; the transformative dimension includes “Debates and comments that help overcome non-consensual relationships” (see Table 1 ). Posts, comments and quotes that included the keywords, or referred to them, were analysed following the main category drawn from the literature and the emergent subcategories.

The results are presented in different categories following the ones established in the above-described data analysis procedure. Therefore, subsections ‘Exclusionary dimension: debates and comments that perpetuate non-consent relationships’ and ‘Transformative dimension: debates and comments that help overcome nonconsent relationships’ refer to the exclusionary and transformative dimensions of the main category, respectively.

In this section, we would like to underline that we draw on the conceptualisation of validity claims performed by Habermas ( 1984 ) and updated by Soler and Flecha ( 2010 ), which focuses on the arguments based on sincerity, truth and normative rightness. Thus, validity claims are contrary to power claims, which are framed on hierarchies and power positions.

Exclusionary dimension: debates and comments that perpetuate non-consent relationships

This section analyses the exclusionary dimension of the results: issues that arise from the comments and debates on Reddit and Twitter related to the chosen hashtags that make it difficult to overcome violence against women and gender violence. Data has shown the presence of debates and comments that pose barriers to overcoming relationships without consent.

The instrumental use of #NotAllMen acts as an excuse for some men to perpetrate and get away with unconsented actions. For instance, a tweet reports gay men touching women without their consent but justifying that they are not sexually attracted to them. Much more extended are conversations where the rape culture is strengthened. Some male posts include the views that a woman’s “no” actually means “yes”, or that they just need to be “warmed up”. An open discussion on Twitter expressed the ideas of a man who argued that men have to insist because girls have learned to say “no” initially out of fear of looking easy, and that if men simply complied none would ever get laid. He shared a story where he respected the “no” of a girl who he later found out had ridiculed him with her friends with an insult regarding his sexual abilities, and that the following day she had called her vile ex to have sex because the first guy had left her sexually frustrated. What is more, the girl’s friends offered him a solution that is not focused on consent and communication, but rather on techniques to have sex from an instrumentalised and senseless point of view.

Related to the previous interaction, we highlight a man’s reflection of how women, he argues, engage in more or less consensual sex depending on whether men are more of a dominant or a nice-guy type. The comment shows that, with dominant men, women would consent to certain sexual practices he considers degrading, but which they would not have consented to with a non-dominant man. This statement can be aligned with previous research where it is noted that the existence of a dominant coercive discourse, linking attractiveness to bad boys and emptying nice guys of desire, is influencing socialisation processes with regard to affective-sexual relationships (Puigvert et al. 2019 ).

Both women and men express how some men behave differently whether in the presence of women or when they are among other men: those men act decently when addressed individually or among women, but openly exhibit misogynistic and anti-feminism comments and ideas when only men are present. Linked to that, some anti-violence men express on Twitter a popular and extended sense of silent and permissive brotherhood from some dominant men with any men, with whom they feel safe to say comments that perpetuate the rape culture. Critical debates about such situations are found in Twitter, and they include criticism of a larger group of less dominant but unconfident men who are nonetheless dragged along, wanting to fit in, and either stay silent or even encourage or reinforce the initial comments or behaviours.

Some female Reddit users express resistance to understanding the lack of consent from some men in different situations. For instance, a doctor stole a woman’s number from personal data to ask her on a date, to which she felt stalked; her male friends excused this behaviour as understandable, as “he was taking his chance”. Another issue that different users point out is the difficulty to identify men who do not care about consent when deciding whether to have a relationship with one.

Some difficulties, concerns, and doubts are shared on how to induce change in such dominant men. Contrary opinions are shared on the role that male friends can have in stopping comments. On the one hand, the problem of being a minority that stands up against them is thought to result in no positive impact. This lack of impact in individual actions can go from not taking the comment seriously to receiving attacks, which discourages them from future standing up because they feel it is not worth it. Men identify how not having a strong network is turning into a barrier for them.

Debates showed different elements as to why non-violent men do not feel empowered or ready to stand up to violence against women. An issue that discourages some non-violent men’s involvement is “being put in the same boat” as the offenders, which frequently happens: they may be labelled as contributors or the problem, and attacked online for it. Further, at times when these men call out all forms of violence, including those perpetrated by women, they are attacked as misogynistic. Some spaces with a supposedly feminist standpoint seem to fuel this notion and its consequences, sharing repeated messages that “all men are evil”. Likewise, some comments state that men who have healthy relationships should not be valued because that is what should be normal; some men themselves, when they support victims or the fight against gender violence, respond defensively because they should not be promoted for doing “the bare minimum”.

Some men show in different online debates struggles in knowing how to flirt, while they seem to try to learn not by engaging in meaningful conversations but by reading self-help guides. They do not believe there are successful alternatives to the dominant model of insisting on women. That leads these men to hide their sexuality to ensure women are not bothered by them, but such an attitude results in women never taking them out of the friend zone. Consequently, to the internalisation of the idea that “successful masculinity is only found within traditional approaches”, these “nice guys” express their need to adopt dominant behaviours due to their initial lack of success and the actual success they achieve when they behave badly. Linked to this, a woman on Reddit expresses her view that most men are very romantic and loving towards women; to this comment, a man’s answer expresses that many men are initially like that, but after some bad experiences, they are taught by women that those attitudes will not bring them any success. Therefore, to appear attractive to women, those initially egalitarian men feel like they have to train themselves not to be kind, even if most of them resist that mindset and keep on longing for mutually loving relations.

Non-scientific debates on men and consent

Next, we explore comments and debates that are not supported by scientific evidence. These conversations, which may be rooted in hoaxes related to gender issues, are not focused on discussing solutions or transformative proposals for the prevention of gender violence, specifically around consent.

The hashtag #NotAllMen is widely seen and explored. This hashtag is mostly used by men who claim never to have committed sexual assault or violence against women and state that they are not like that, even though they have not been personally accused. They act defensively, interfering in debates where women, and sometimes men, have conversations about experiences of non-consent or gender violence. It is then when these men alter the course of the discussion and, not caring for the victim’s feelings or offering any form of ally-wise support, interrupt the debate to let everyone know they would not do the aggression being reported and criticised. As a consequence, victims and people who support them feel their concerns undermined.

Some men use hoaxes that deny the gendered base of violence, alluding to false reports from women being assaulted or to statistics being wrong. Certain profiles manipulate cases and statistics of male sexual abuse to strengthen misogynistic beliefs; or use men’s suicide stats to bring up men’s issues as a tool to switch the approach of the subject, silencing victims’ voices.

Last, some debates introduce incorrect biological assumptions about innate sex drive differences between men and women, which are used with ulterior motives to justify some men’s behaviours. Likewise, non-scientific conclusions that account for more self-control in women than in men are explained and used to justify some men paying for sex, even if they criticise such behaviour.

Transformative dimension: debates and comments that help overcome non-consent relationships

This section summarises the transformative dimension of this study: well-reasoned and impactful critiques against comments that perpetuate the non-consent culture, and against male inactive bystanders. Firstly, the #NotAllMen hashtag is strongly criticised; it is argued that nobody created an initial #AllMen hashtag (referring to all men being aggressors) to which the #NotAllMen hashtag had to be counter-used to make justice.

As another validity claim against #NotAllMen comments, very diverse comments and posts state the widely-held view that the men who harm women are a minority, but declare that this is not the point of the conversation. Some comments use #SomeMen to refer to perpetrators of the worst gender violence, such as rape or murder, to move the attention towards less grave but still worrisome situations that many women suffer, which all portray cases of harassment and violence that create the base of a pyramid of violence: that includes actions boys and men perpetrate, from looking under a girl’s skirt to “slut shaming”. These comments express a wide range of situations of violence against women concerning consent.

In a complementary way, there is a public accusation of men who are accomplices and who therefore support rape culture: some of the behaviours they criticise include men letting rape jokes slide, looking the other way because “it’s none of their business”, or not seeing the problem of using the “boys will be boys” statement.

We found repeated criticism towards people, mainly men, who act defensively but may be incoherent and stand by in face of non-consent situations. That critique is frequently supported by the notion of not being part of the solution: many female users ask if all men do what they can to ensure that other men do not harm women, by stopping bad behaviours or engaging in conversations about women’s safety and consent with their sons. They encourage those men that, before writing #notallmen, they share all their actions in defence of consent and women, such as campaigns, talks in schools, or gatherings to discuss male violence. Otherwise, they argue, it appears as if they seek recognition for not engaging in sexual assault. Some hashtags that reinforce this bystander critique include #TooManyMenNotSpeakingUp and #TooManyMenProtectingHorribleMen. Other users explain that bystanders are evil as well as the aggressors, for seeing hostile situations and doing nothing, since by looking the other way they are endorsing dominant men to escalate to worse behaviours. In this sense, the New Alternative Masculinities approach has demonstrated that alternative men’s positioning and rejection is a transformative response to these men or men’s groups complicit in the perpetuation of non-consensual relationships (Nazareno et al. 2022 ).

Transformative debates on consent and men: men who stand up against gender violence reject non-consent in their relationships

Next, transformative conversations regarding consent and men are presented. These debates offer alternatives, advice based on enthusiastic consent, or help men stand up to violence against women.

Educating about consent is a shared concern and a successful preventive strategy for many people, both in educational institutions and within families. Sex education in high schools seems too late for many, as they argue it should start in preschool years with non-sexual situations, with notions such as consent for physical touching. Regarding teaching consent in sexual-affective relationships, some comments include critically addressing from the “no means no” to a “yes means yes” that takes into account non-verbal communication. Further in that sense, some debates on Twitter express that the ultimate goal to be pursued when discussing consent with youth should be mutual enjoyment and good sex. Educators and parents showing themselves as available for open and continuous dialogues with youth are important for these social media users; from their perspective, adults should frequently engage in critical dialogue about situations they watch together in movies so that they distinguish whether there was or not consent. Another man shows his determination that we should teach our young men about what it is to be a man in sex, “which always starts with consent”. The tea metaphor for learning consent video is shared as a useful resource, with over 20 million views on YouTube. Mention is made towards preventive, governmental and systemic approaches that include the educational system and all social spheres, such as the police and workplaces.

Training men to become confident and successful upstanders is also discussed. Many public campaigns, such as #AllMen by Women’s Aid Organisation, have this approach. For instance, men who lead the men’s engagement campaign “Don’t be that guy” express that men do step up and want to engage in dialogue and action about these issues: one of them explains that since the beginning of one of the campaigns he had been receiving positive daily messages from men, as well as support from women. Some of the famous men portrayed in the campaigns further develop the campaign in their media profiles, having conversations with experts who discuss scientific evidence of the impact of male sexual entitlement on violence against women.

Following that course of action, it is clearly expressed the need for men to have an active role in stopping violence by changing the atmosphere, rather than just an intrapersonal approach to changing their own actions. That involves, they say, retaking social spaces where sexist men think that their misogyny is accepted until they have no spaces where they feel their behaviours are normal. Some comments acknowledge that “leaders set the tone”, but criticise looking up because that encourages the bystander effect -people waiting for others to intervene. In this sense, the bottom-up community approach is reinforced, stressing the need for everyone to be an upstander.

Many discussions on social media, involving both men and women, focus on criticising and condemning non-consent relationships and situations mostly shared by women while expressing support to the victims. When women break the silence online and speak up about a situation they suffered, many men show messages of empathy, support, and rejection of the offenders and their behaviours.

Some debates in social media show that many people choose not to engage in a conversation with other people who are not interested in having an egalitarian dialogue focused on collective solutions; these persons move away from such encounters and focus their energies on those who are willing to engage in respectful and constructive dialogue. Users choose to mute Twitter threads when “gender-critic trolls” invade it with ill-intentioned comments; others choose to stop interactions and relationships with the most dominant men in their environments because it is counterproductive to intervene as an isolated action.

Struggles from unconfident men who care about consent are mostly met with support and advice from other men. That advice includes being assertive and confident about one’s desires, while maintaining an open mind to what the other person may want and being willing to stop. These conversations offer advice about building up a relationship so “it’s pretty clear” that the other person feels comfortable with them before asking for a date or a kiss. Being thoughtful and considerate towards the other person is also appreciated among some men’s debates and seen as a virtue, even if that means some women will lose motivation because they are not used to such kindness. According to the comments analysed, this is not seen as the man’s problem but as the woman’s loss.