- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Better Brainstorming

- Hal Gregersen

Great innovators have long known that the secret to unlocking a better answer is to ask a better question. Applying that insight to brainstorming exercises can vastly improve the search for new ideas—especially when a team is feeling stuck. Brainstorming for questions, rather than answers, helps you avoid group dynamics that often stifle voices, and it lets you reframe problems in ways that spur breakthrough thinking.

After testing this approach with hundreds of organizations, MIT’s Hal Gregersen has developed it into a methodology: Start by selecting a problem that matters. Invite a small group to help you consider it, and in just two minutes describe it at a high level so that you don’t constrain the group’s thinking. Make it clear that people can contribute only questions and that no preambles or justifications are allowed. Then, set the clock for four minutes, and generate as many questions as you can in that time, aiming to produce at least 15. Afterward, study the questions generated, looking for those that challenge your assumptions and provide new angles on your problem. If you commit to actively pursuing at least one of these, chances are, you’ll break open a new pathway to unexpected solutions.

Focus on questions, not answers, for breakthrough insights.

The Problem

Great innovators have always known that the key to unlocking a better answer is to ask a better question—one that challenges deeply held assumptions. Yet most people don’t do that, even when brainstorming, because it doesn’t come naturally. As a result, they tend to feel stuck in their search for fresh ideas.

The Solution

By brainstorming for questions instead of answers, you can create a safe space for deeper exploration and more-powerful problem solving. This brief exercise in reframing—which helps you avoid destructive group dynamics and biases that can thwart breakthrough thinking—often reveals promising new angles and unexpected insights.

About 20 years ago I was leading a brainstorming session in one of my MBA classes, and it was like wading through oatmeal. We were talking about something that many organizations struggle with: how to build a culture of equality in a male-dominated environment. Though it was an issue the students cared about, they clearly felt uninspired by the ideas they were generating. After a lot of discussion, the energy level in the room was approaching nil. Glancing at the clock, I resolved to at least give us a starting point for the next session.

- Hal Gregersen is a Senior Lecturer in Leadership and Innovation at the MIT Sloan School of Management , a globally recognized expert in navigating rapid change, and a Thinkers50 ranked management thinker. He is the author of Questions Are the Answer: A Breakthrough Approach to Your Most Vexing Problems at Work and in Life and the coauthor of The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators .

Partner Center

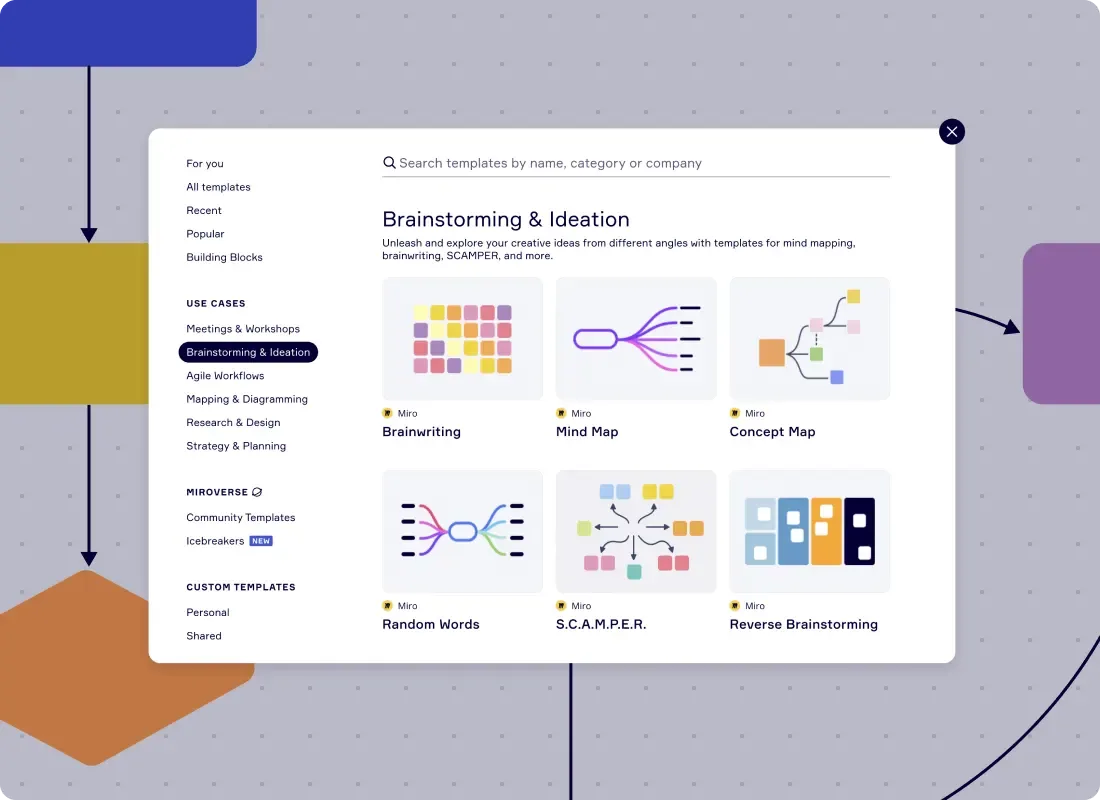

What is brainstorming? Definition, guide, and methods

.png)

When you hear the term brainstorming, there are a few images that might come to mind. One is the classic stock photo of a group of colleagues huddled around a whiteboard or a pile of papers, all big smiles and high energy.

But brainstorming sessions don’t always go as smoothly as these images make them seem. Sometimes, there are disagreements between co-workers. Other times, there’s too much agreement with just one person’s ideas. And then there are days when ideas just don’t seem to make their way onto the blank canvas in front of you.

Whether you’re problem-solving, developing a new product, or trying to come up with creative ideas for your business, brainstorming isn't just about gathering your group members together and hoping the innovation sparks fly.

There are proven methods, techniques, and tools that can make effective brainstorming easier than ever.

In this guide, we’ll dive into all of the resources Mural has put together to help managers and their teams run successful brainstorms.

What is brainstorming?

Brainstorming is a method for producing ideas and solving problems by tapping into creative thinking. Brainstorming usually takes place in an informal, relaxed environment, where participants are encouraged to share their thoughts freely, build upon the ideas of others, and explore a wide range of possibilities.

How to get the most out of your next brainstorming session

Running a great brainstorming session encourages your team to use techniques that inspire creative thinking. As a manager, you’ll likely be the one to facilitate these sessions and make sure they run smoothly and produce positive results.

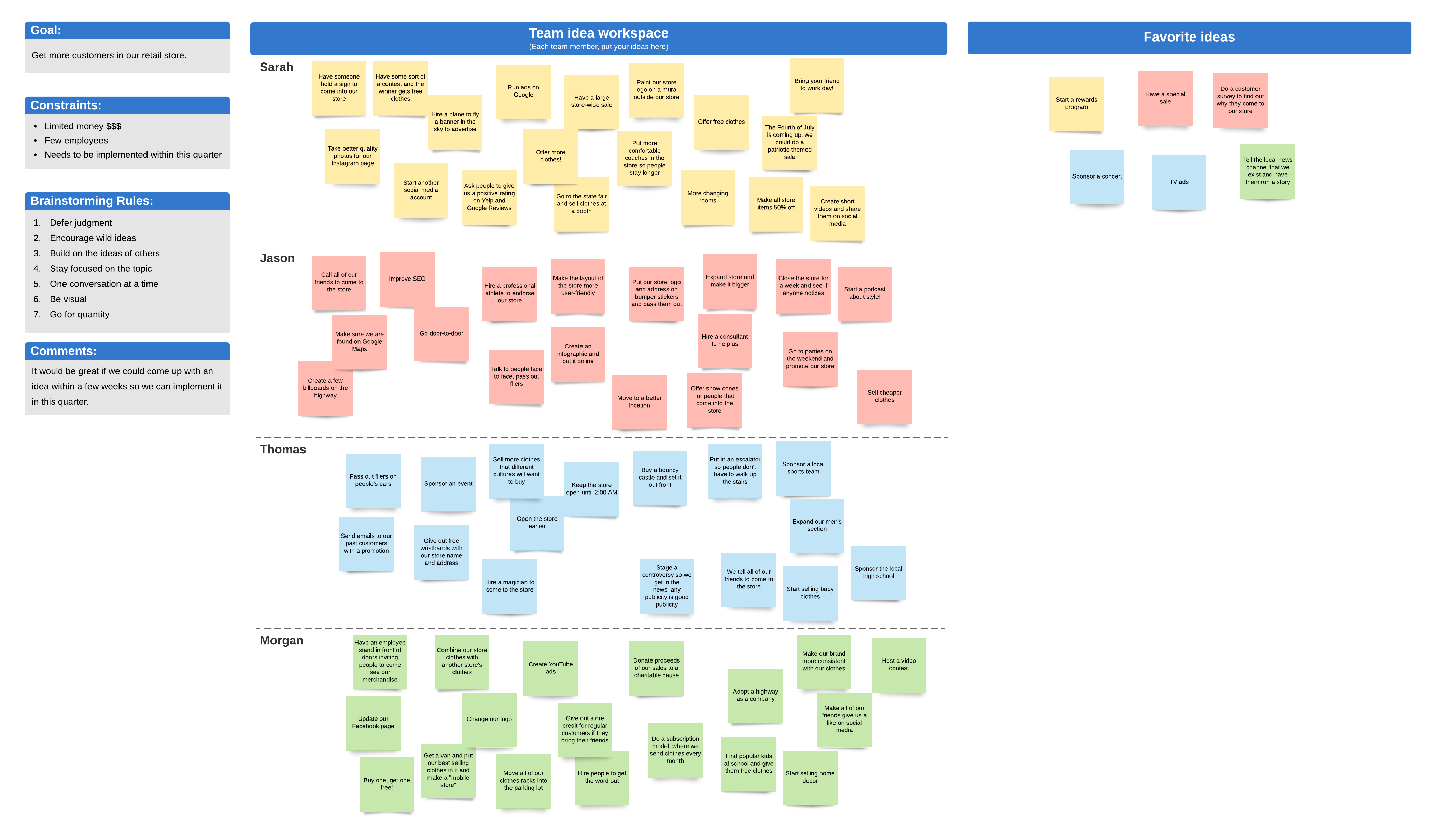

How to run a brainstorming session

As a facilitator, it’s your job to guide your team in the right direction throughout the process, from start to finish. To start, prepare for the session and define your brainstorming topic.

This means setting a clear purpose or goal for the session, deciding on a structure, and dividing your team up into small groups if need be. You’ll also want to define the rules and parameters for your team members.

Next, depending on the brainstorming method you’ve chosen, you may need to keep an eye on the time to give everyone a chance to contribute. Throughout the process, encourage members to voice their opinions. Toward the end, make sure you explain any next steps or action items for your team.

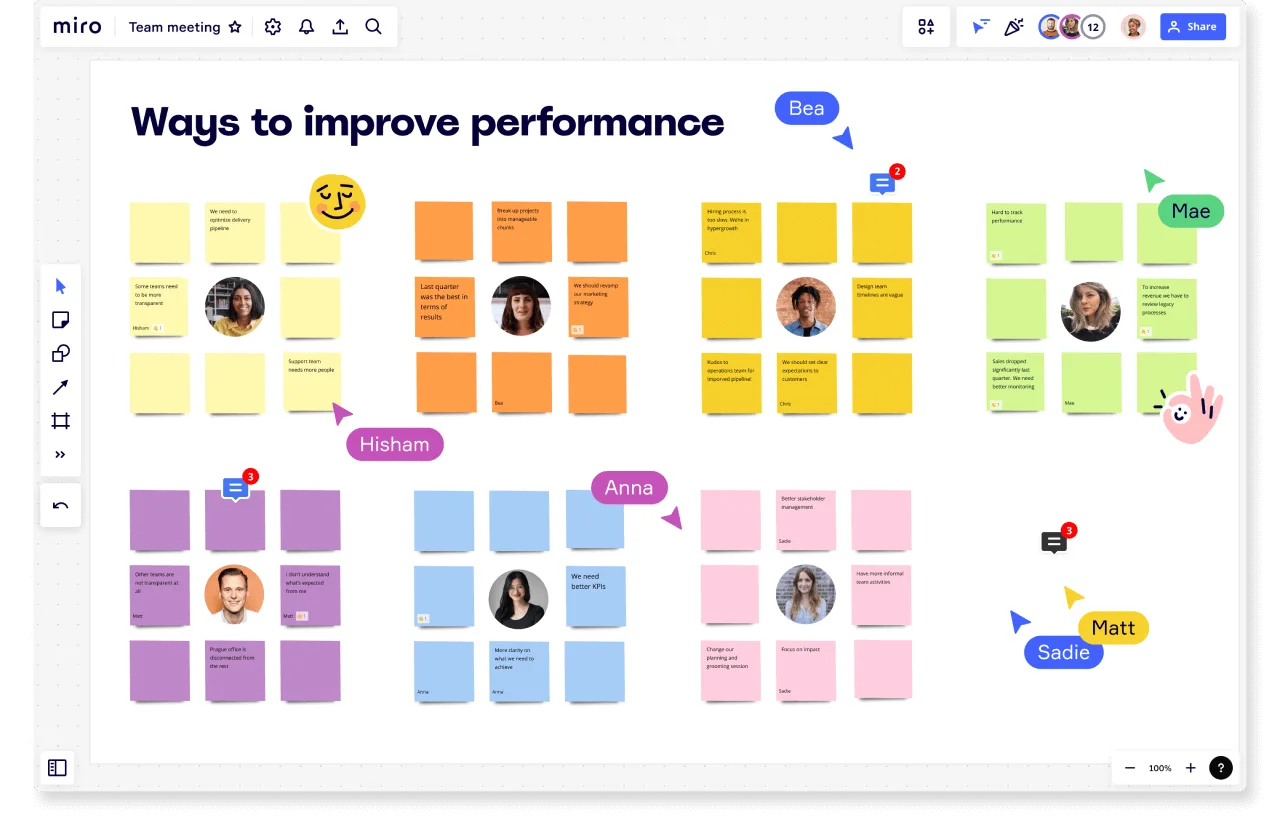

Strategies for better group brainstorming

Group brainstorming can help you generate awesome ideas that one person alone might never come up with. But when you gather a group of people together, it often comes with some challenges. Dominant personalities can hijack a conversation, making the exercise less effective and the rest of the group feel unheard. Groupthink is another potential issue in which too much conformity prevents you from delivering original or creative solutions.

Here are a few things you can do to combat these challenges and have better group brainstorming sessions:

- Establish rules that emphasize the importance of diverse points of view.

- Choose a brainstorming technique that's beneficial for groups, like reverse brainstorming or ‘Crazy 8s.’

- Make sure team members have time to also do some solo thinking.

No matter what techniques you implement, the key is to make sure every participant is on the same page when it comes to rules and expectations.

Structured brainstorming and when to use it

A structured brainstorm helps keep everyone focused on your goals or the task at hand. It’s also a good way to make sure everyone’s opinion is heard. In some cases, participants can also prepare ahead of time, which could be beneficial for the overall success of the activity.

Structured brainstorms are best for remote or distributed teams to efficiently replicate past successes, and for large groups.

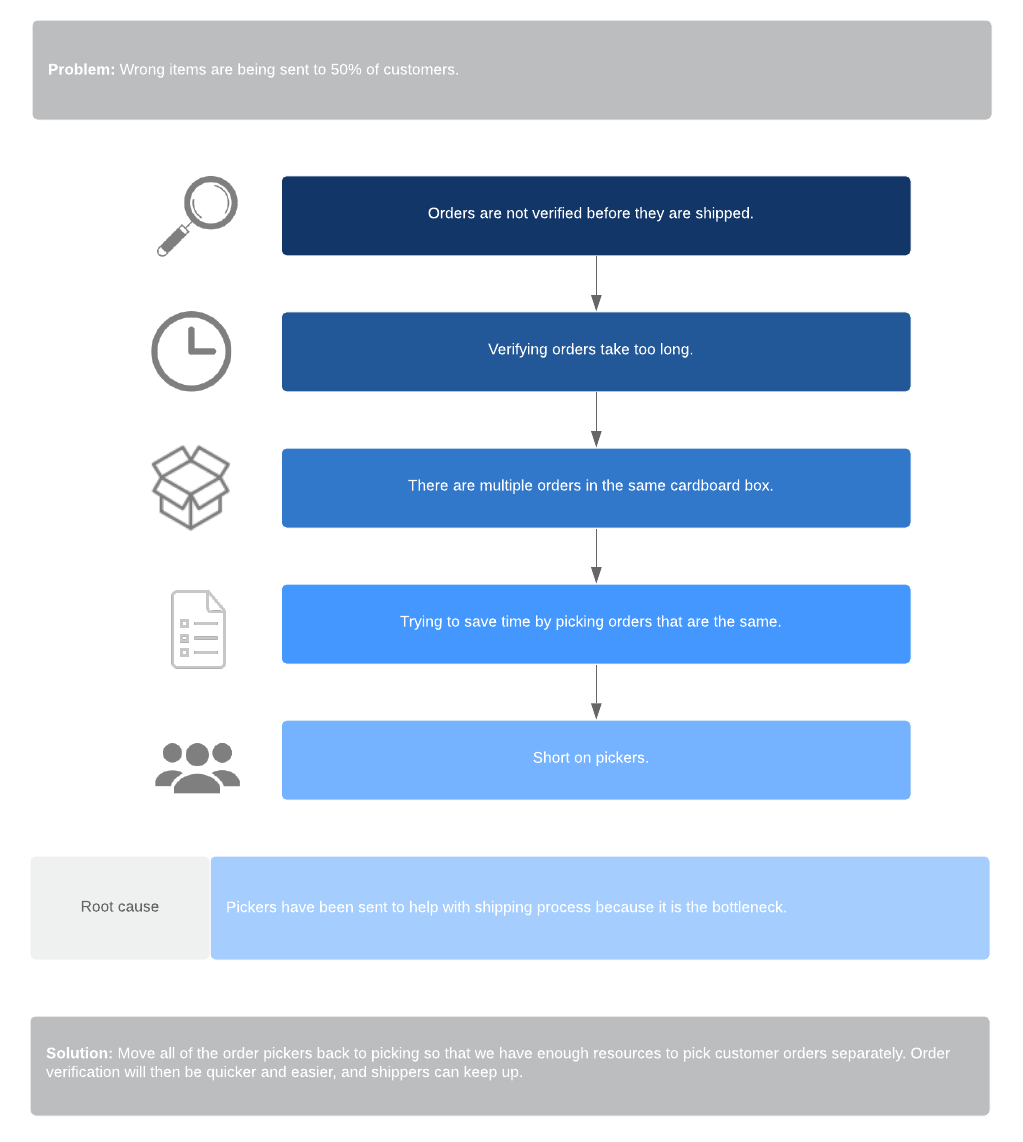

Understanding problem framing

Problem framing is a critical step in the brainstorming process that gives context and provides a deeper understanding of the purpose of the brainstorm. It helps provide your team with clarity and a narrow scope so that their ideas aren’t all over the place. It also helps increase the efficiency of the session as you or the facilitator can spend less time re-orienting them back in the right direction.

Here are a few steps for framing a problem:

- Create a problem statement .

- Identify the root of the problem.

- Empathize with customers or stakeholders.

- Frame the problem with prompts or questions that can be used during brainstorming.

Brainstorming questions to generate better ideas

Thought-provoking questions can really help your team thrive during a brainstorming session. They provide participants with a starting point to think up ideas or directions. They can also be used to enhance or refine any suggestions or solutions that have already been produced. Here are a few examples of the types of questions that produce better ideas:

- Information-gathering questions (e.g., “Why did we shift our marketing strategy from traditional advertising to digital platforms?”)

- Problem-solving questions (e.g., “What are the criteria we should use to evaluate potential solutions?”)

- Refining questions (e.g., “How can we ensure the sustainability of the solution over time?”)

Questions can help reduce the overwhelm or blind spots that can happen as you develop ideas. It narrows everyone’s focus and helps you make ideal decisions.

Advice for teams during a brainstorming session

Generating ideas that solve challenges can be a lot of pressure for your team. It can also be discouraging if it feels like they’re not coming up with anything groundbreaking or even viable. Not to mention, there can be a lack of cohesion and beneficial collaboration among group members.

But, knowing the right strategies and rules for effective brainstorming can help turn a stressful activity into a productive and fruitful one.

Ground rules for brainstorming

Ground rules help set expectations, decrease the chance of a conflict, and make participants feel more comfortable throughout the process. Before your team gets started on ideation, they should create a “rules of brainstorming” document that they can refer to throughout the process. You can create this for them or have them make one as a team.

Here are a few examples of significant ground rules that improve the flow of a brainstorming session:

- There are no “bad ideas”; be accepting of all suggestions no matter how crazy and wild. (You can always iterate, refine, or vote on it later.)

- Incorporate a “private” portion of the brainstorm so people can think for themselves.

- Read ideas carefully before commenting, and don’t judge others' ideas at face value.

Following these rules and others relevant to your team’s needs can help ensure a smooth and efficient process.

Avoiding groupthink in teams

Groupthink is when people, consciously or unconsciously, choose to agree with one another rather than challenge each other with conflicting views. This can happen when there’s poor conflict management, a lack of diversity, or psychological safety issues. One way you can tell that your team is under the spell of groupthink is when there's quick and unanimous agreement or a lack of push-back or follow-up questions to others’ ideas.

To reduce the chances of groupthink, consider ways you can remove bias, like using a private mode or voting feature. Participants should encourage each other to express their own ideas, even if that means light conflict when there's a difference of opinion. It’s also important that every team member understands groupthink and how to spot it.

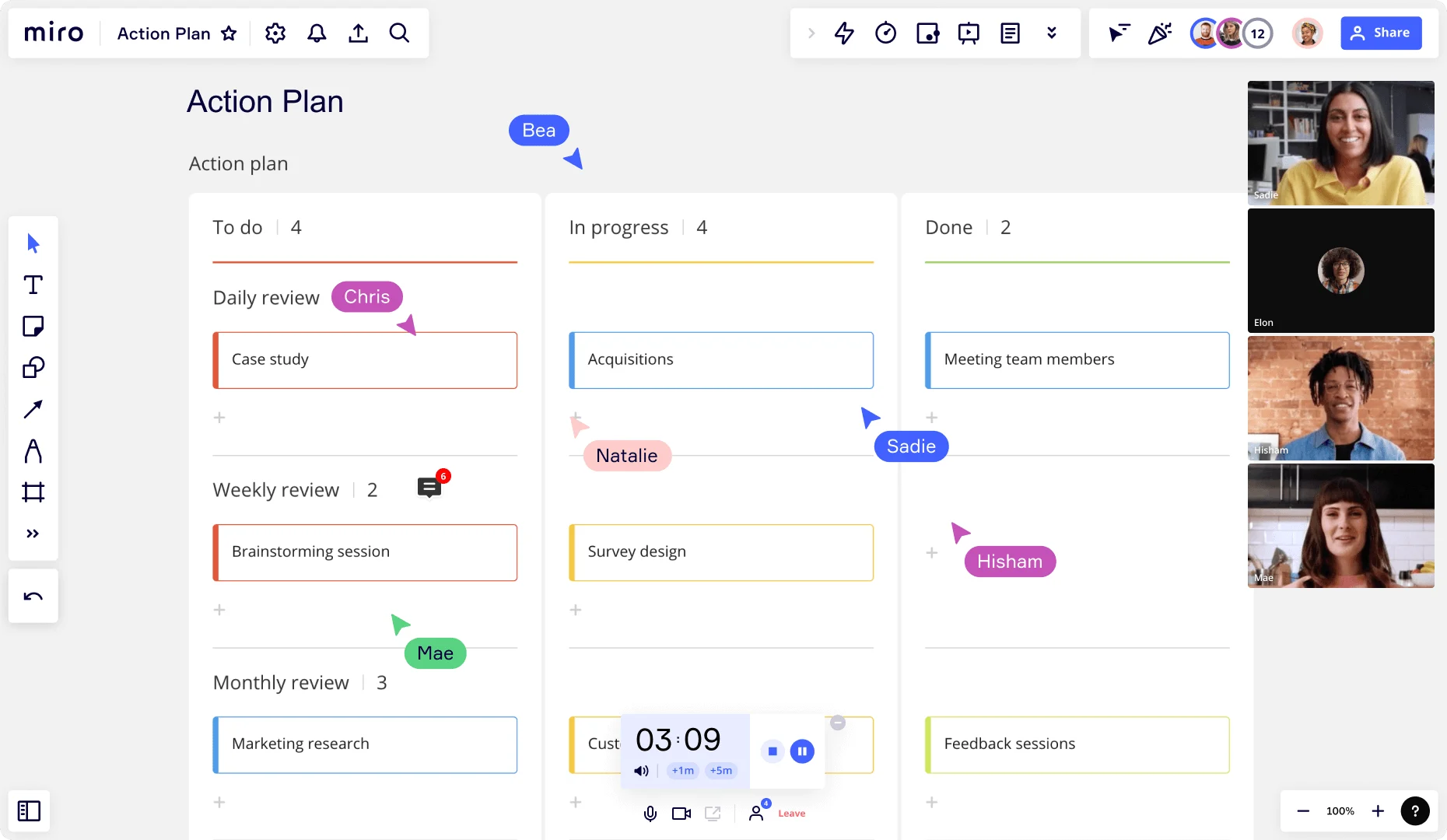

Creating better action items to follow up on

At the end of a brainstorming session, team members should have a list of action items to follow up on. These action items hold everyone accountable and help keep track of progress as you carry out tasks related to the solutions developed during the brainstorming session.

An effective list of action items has the following traits:

- They summarize what needs to be done.

- They explain why each action item or task matters.

- They have a team member assigned to each item with a due date.

You can use a simple to-do list or a project kickoff template , whatever works best for your team!

Tips for brainstorming remotely

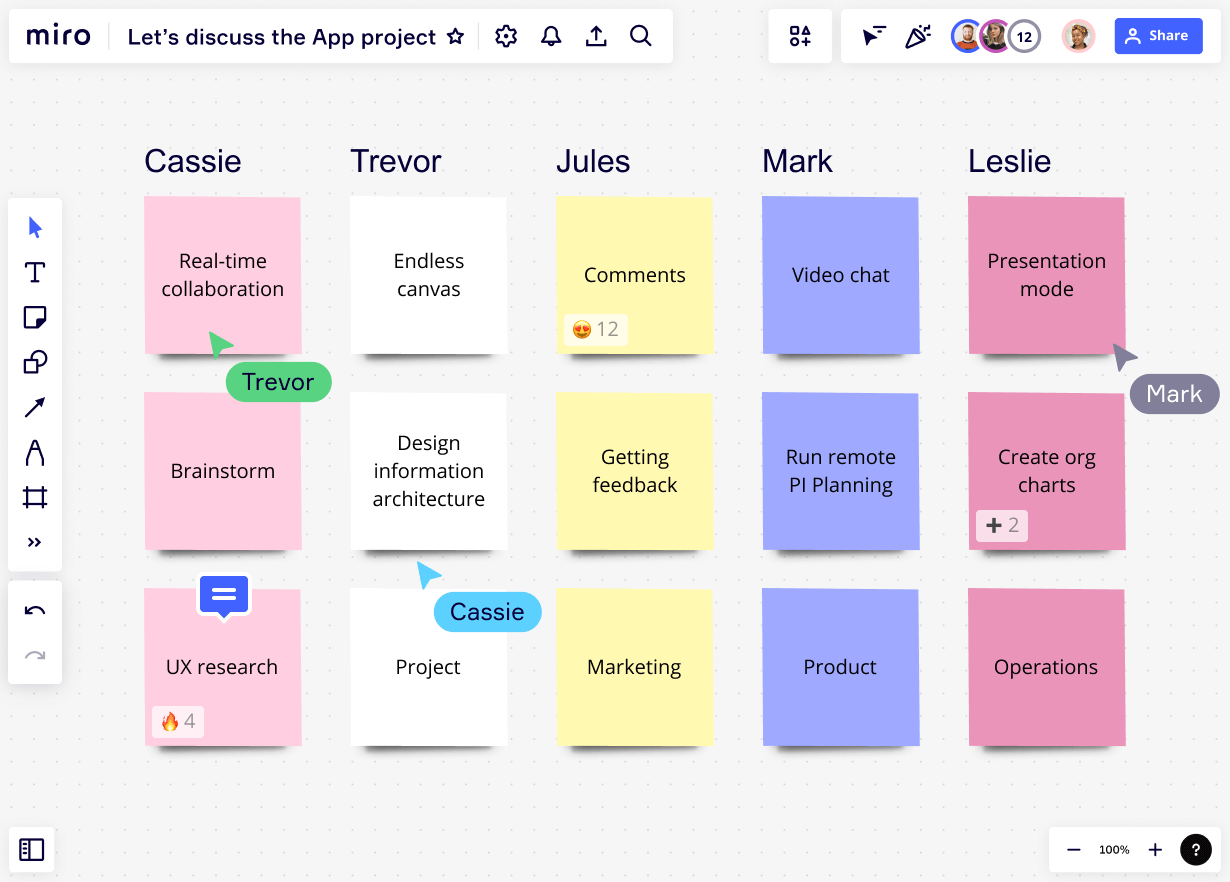

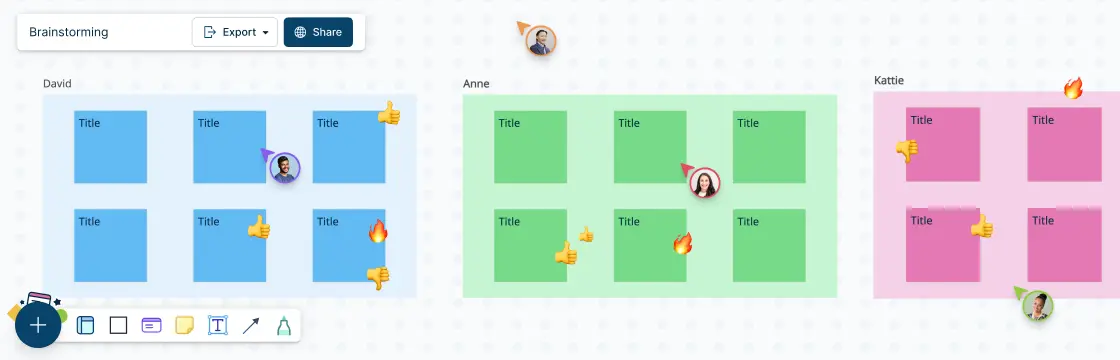

Remote brainstorming exercises can be just as successful at idea generation as in-person brainstorming. The main difference between running a regular brainstorm and a virtual one is the tools you use to communicate and collaborate. Group discussions can be done easily through software like Zoom or Microsoft Teams . Plus, online whiteboards like Mural work just as well, if not better than the analog version.

Optimize your virtual brainstorming session

Virtual brainstorms lack some of the face-to-face interaction of an in-person session. This means you’ll need to adapt your processes to fit an online dynamic. For one, it’s crucial to find a collaboration platform where everyone can contribute their ideas in a central location. You’ll also need a facilitator or point person to keep everyone on track and update the shared document or whiteboard accordingly. Brainstorming templates are also extremely useful for creating an efficient and smooth virtual meeting.

Try asynchronous brainstorming

Asynchronous brainstorming is a great option for those who want to prevent groupthink, improve focus, and reduce time constraints — especially for distributed teams. If you have a team that works across different time zones or working hours, individual brainstorming allows them to contribute at a time that works best for them.

Just like a synchronous brainstorming, you still want to establish a clear goal, select a collaborative platform, and outline the rules and expectations. However, a key difference is that for async work, you need to establish a timeframe and set deadlines so that you’re not waiting on any one person to contribute, iterate, or respond to ideas.

Related: 6 essential steps for building an async-first culture

Improve group communication

Whether you’re in-person or remote, effective communication improves collaboration, increases productivity, and promotes problem-solving. But when you’re working on a distributed team, solid group communication is vital. In our busy digital spaces, things can either get lost in translation or literally lost in a pile of emails and Slack messages.

Here are a few helpful things you can do to combat poor online communication:

- Recognize and celebrate healthy behavior and helpful communication examples.

- Foster a supportive culture that invites constructive feedback but not judgemental criticism.

- Build trust through team activities like icebreakers or team check-ins .

- Use tools that make communication easy and efficient.

Working on each of these will help your team get their footing when it comes to communicating and flourishing in remote work environments.

Brainstorming techniques, methods, and templates

There are countless brainstorming methods and techniques you and your team can use to uncover creative solutions. Some involve lateral thinking, while others start with a basic brain dump. Regardless of which you choose, it’s a good idea to try out different ones over time and see which produces the best results for your team. In fact, switching up the brainstorming method could add some novelty by reengaging your team to come up with new ideas each time you’re faced with a challenge.

One thing most brainstorming methods have in common is the idea of quantity over quality. At the beginning of any brainstorming session, the number of ideas you produce is often more valuable than the quality or viability of any one of those ideas. You can always keep workshopping the existing ones until you narrow down and refine the optimal ones.

Rapid ideation

Producing a high quantity of ideas is the name of the game here. There are many brainstorming exercises that incorporate rapid ideation. The key is to be quick and spontaneous so as not to censor or edit any ideas that come to mind.

Brain-netting

Brain-netting is a term used to describe brainstorming via multiple digital tools and spaces, in other words, online brainstorming. Typically, it’s preceded by online brain dumping, and then connecting related ideas and concepts to narrow down the best ones.

Reverse brainstorming

Reverse brainstorming is a counterintuitive technique in which you come up with ideas on how to make a problem worse. Then, you “reverse” those ideas by coming up with applicable solutions to those problems. This process helps you discover some possible ideas for your original challenge.

Round-robin

In round-robins, each participant writes their idea down during a set time limit before the next person gets a turn to contribute. There are a few variations of this: You can compile ideas on sticky notes to return to later, pass them off to the next person to iterate on, or refine the ideas by providing feedback.

Ready to get started? Try the round-robin template from Mural.

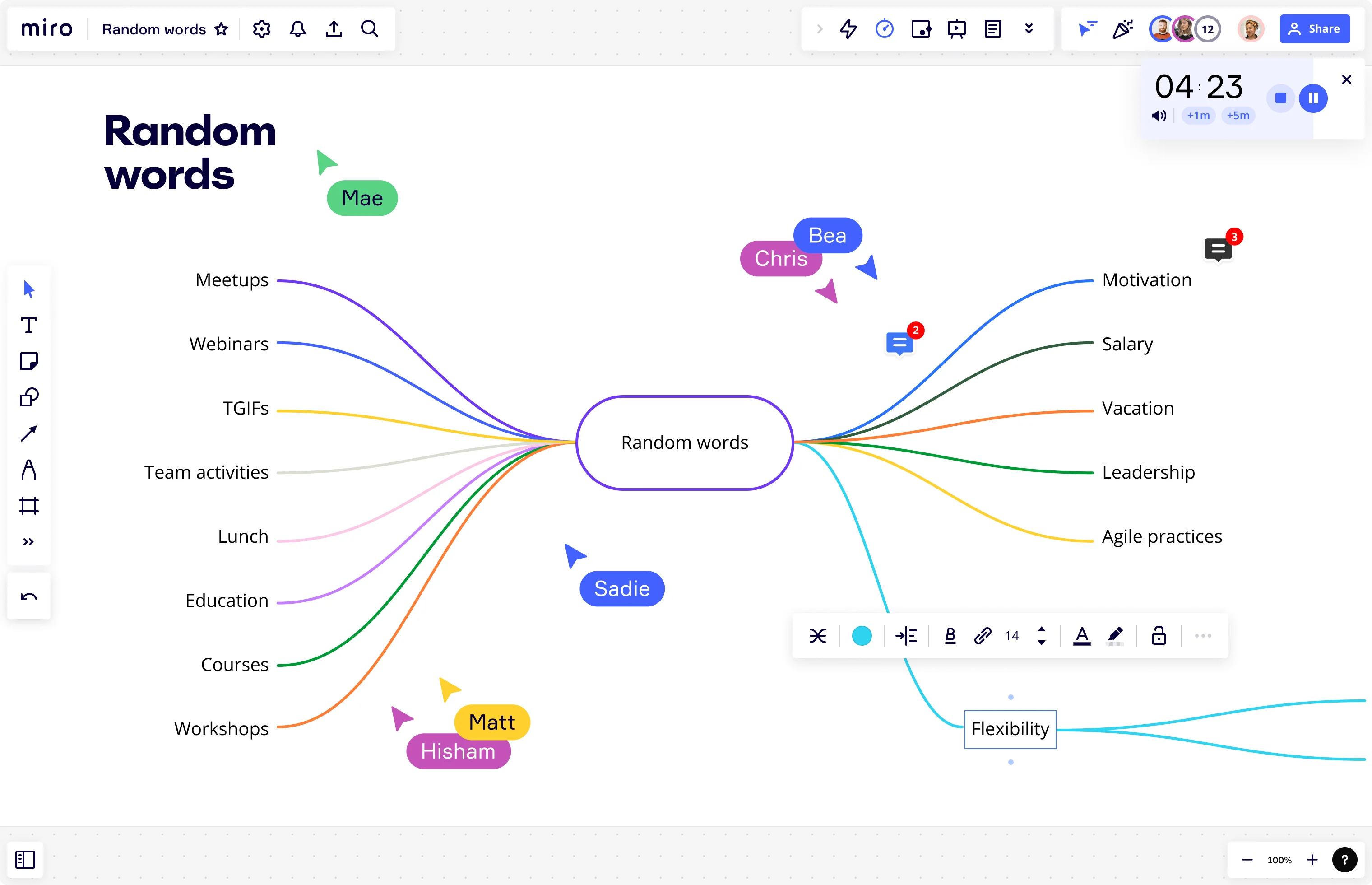

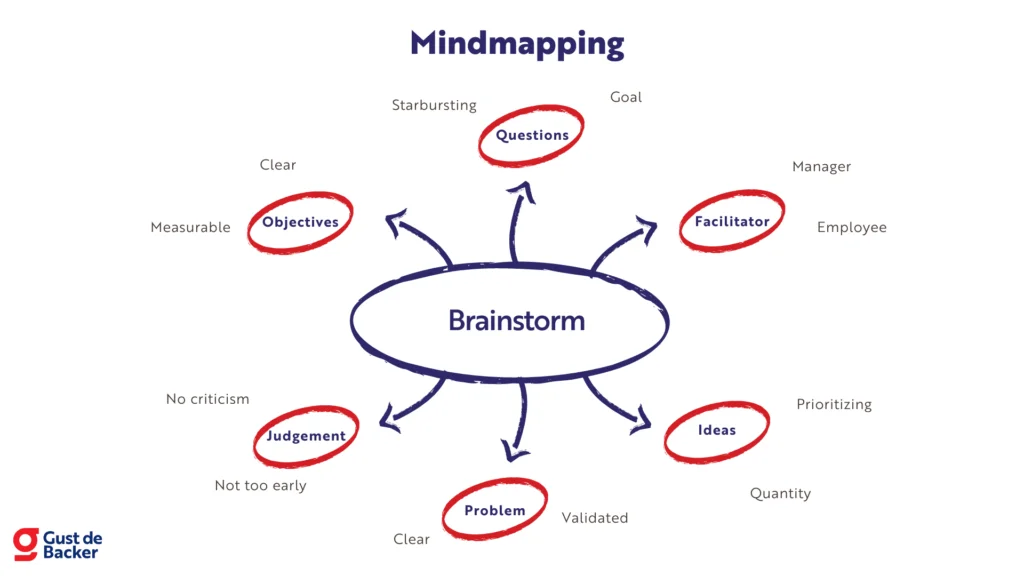

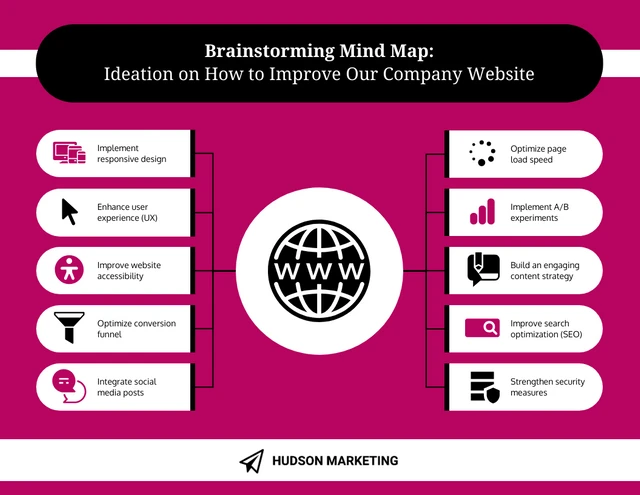

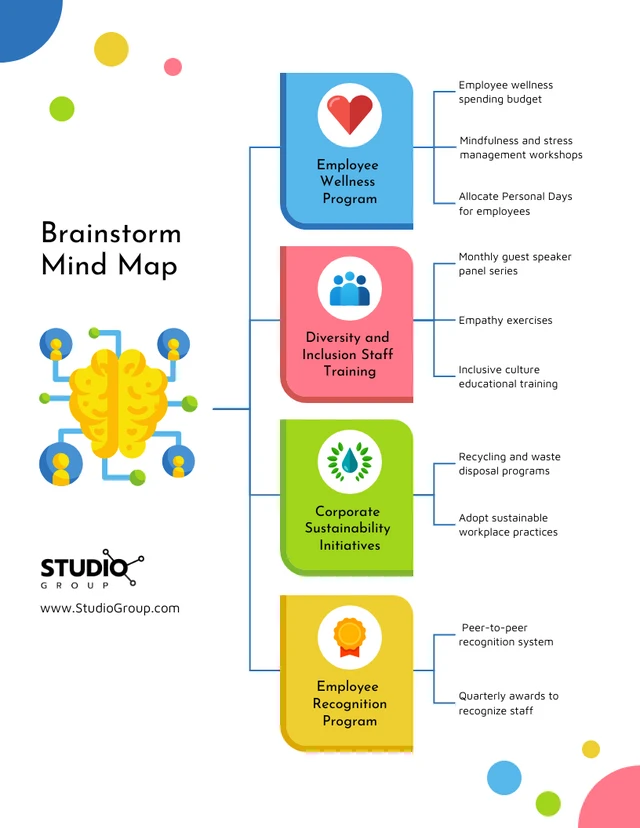

Mind mapping

Mind mapping is a visual way to brain-dump ideas onto a blank page and use those existing ideas to spark new ones. You start with one concept in the middle of the whiteboard and add related ideas on branches shooting out from the central topic. Then you keep building on it like a map or family tree.

Get started with the Mind map template .

Rolestorming

During rolestorming, participants role-play as someone else, such as a famous person or customer persona, to embody different perspectives. Taking on that character during the brainstorm can change the way they think and help them produce creative ideas.

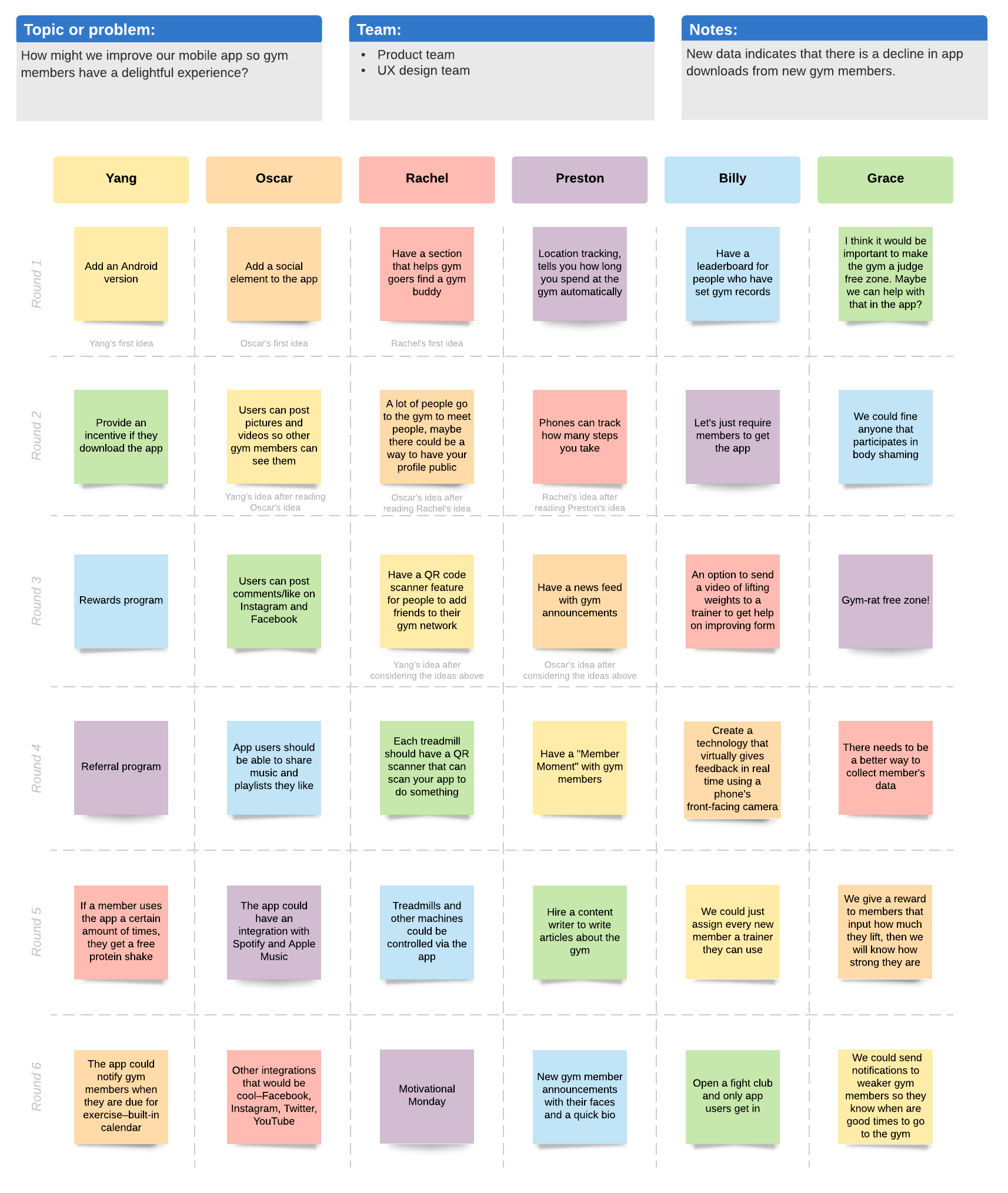

Brainwriting

Brainwriting takes advantage of solo brainstorming time. Participants develop their ideas individually before sharing them with the rest of the team. There are different variations of this method, including a rapid ideation version in which six participants need to each generate three ideas in five minutes.

Start generating ideas with the 6-3-5 brainwriting template .

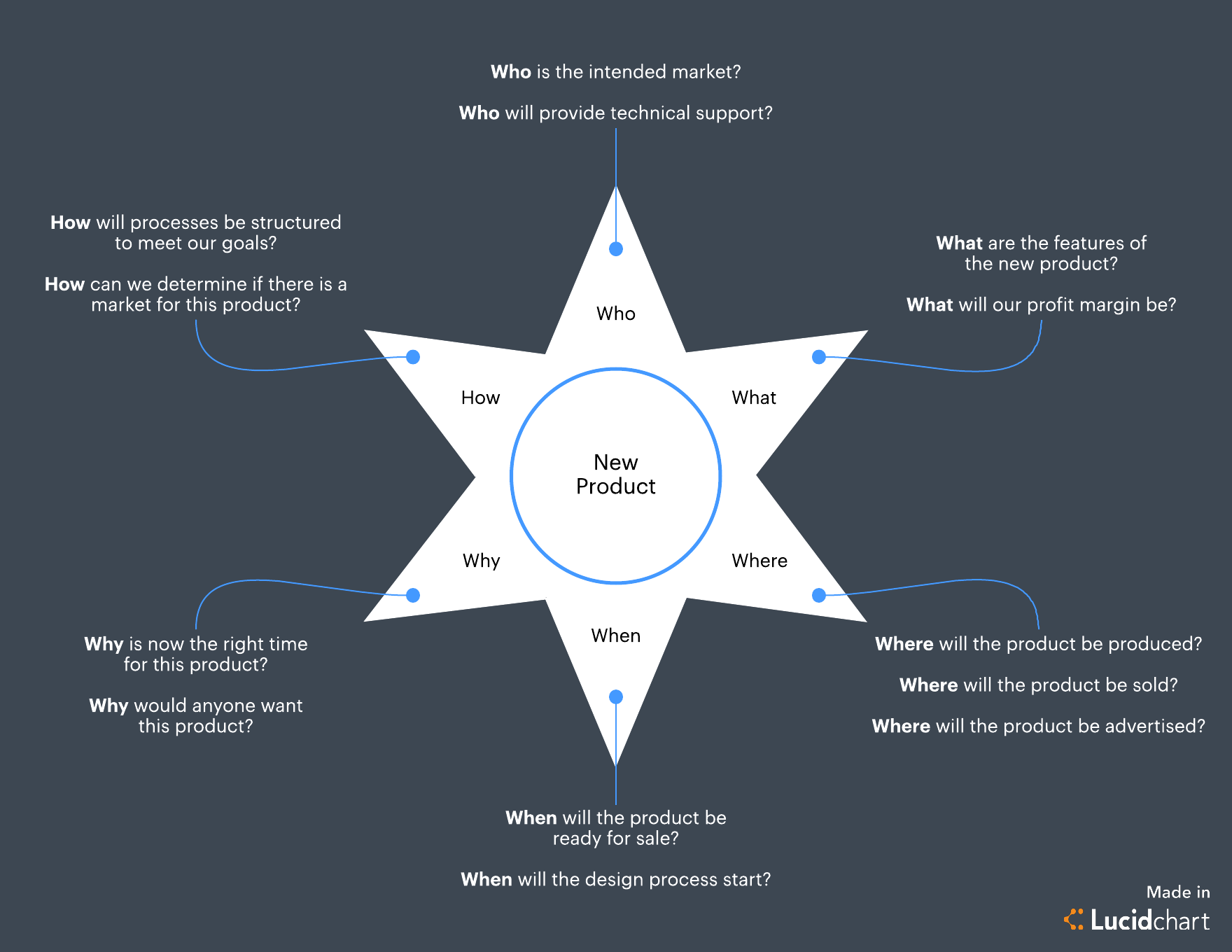

Starbursting

During a starbursting exercise, group members develop questions that begin with “who, what, when, where, why, and how.” These six questions are based on a specific topic or problem statement. The team uses a star graphic, with each point on the star representing one of the six types of questions you come up with during this exercise.

Step-ladder technique

The step-ladder technique begins by selecting two participants in the group to discuss the problem and come up with an idea. Then, you introduce a third team member to the first two, and they present ideas to each other and discuss. Then you add a fourth person, and so on and so forth.

Enhance the collaborative process of brainstorming with the right tools

We use brainstorming activities to help us with creative problem-solving. But without the right tools, it can be difficult to collaborate and record the ideas you’re coming up with together. To make the process more efficient and productive, use tools that make collaboration easier — whether you work in-person, remote, or hybrid.

That’s where Mural can help.

Mural is the visual work platform for all kinds of teams to do better work together — from anywhere. Get team members aligned faster with templates, prompts, and proven methods that guide them to quickly solve any problem. They can gather their ideas and feedback in one spot to see the big picture of any project and act decisively. From online brainstorming , to retrospectives , Mural helps you change how you work, not just where.

That’s what happens when you change not just where, but how you work.

Get started with the free, forever plan with Mural to start collaborating with your team.

About the authors

Bryan Kitch

Tagged Topics

Related blog posts

%2520(1).jpeg)

10 Brainstorming Techniques for Developing New Ideas

%20(1).jpg)

25 Brainstorming Questions to Generate Better Ideas

.jpeg)

How to Facilitate a Brainstorming Session

Related blog posts.

%20(1).jpg)

How to conduct a strategic analysis

%20(3).jpg)

20 top strategic planning tools and frameworks [templates & examples]

%20(1).jpg)

How to make a digital vision board: A complete guide

Get the free 2023 collaboration trends report.

Extraordinary teamwork isn't an accident

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

What is brainstorming? Definition, history, and examples of how to use it

November 28, 2019 by MindManager Blog

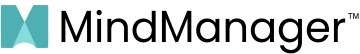

Brainstorming is a great technique that business professionals can use to generate new and unique ideas. It’s a term that’s thrown around quite a bit, and is often used interchangeably with other problem solving and idea generation techniques.

Brainstorming has become part of our daily lexicon in business. But what is brainstorming , and why is it an important technique for business professionals?

This article will tackle these two questions, and give you some examples of brainstorming topics or problems that are common in various business settings.

What is brainstorming?

Brainstorming is a group creativity technique that is often used to find a solution to a specific problem. This is accomplished by gathering and recording new ideas from team members in a free-flowing manner.

Brainstorming sessions are usually made up of a handful of core team members, and typically are led by a director or facilitator.

Brainstorming originated from an advertising executive named Alex F. Osborne, and dates back to around 1939. Frustrated with his employees’ inability to generate creative new ideas, Osborne began developing new methods for problem solving that focused on a team-based approach to work.

He began hosting group-thinking sessions, and discovered that this approach led to a significant boost in the quality and quantity of new ideas. Osborne coined these group meetings “brainstorm” sessions, and wrote about the technique in later publications.

During these brainstorming sessions, ideas are collected and recorded using whatever tool is available to the team. Modern businesses have begun to adopt digital brainstorming tools to speed up the process and make the review phases faster and more productive.

Quantity of ideas is usually emphasized over quality, with the goal of generating as many new suggestions as possible. Once all ideas have been collected, the team then evaluates each of them and focuses on the ones that are most likely to solve the problem.

The four principles of brainstorming

While brainstorming has evolved over the years, Osborne’s four underlying principles are a great set of guidelines when running your own sessions. These principles include:

- Quantity over quality. The idea is that quantity will eventually breed quality as ideas are refined, merged, and developed further.

- Withhold criticism. Team members should be free to introduce any and all ideas that come into their heads. Save feedback until after the idea collection phase so that “blocking” does not occur.

- Welcome the crazy ideas. Encouraging your team members to think outside of the box, and introduce pie in the sky ideas opens the door to new and innovative techniques that may be your ticket for success.

- Combine, refine, and improve ideas. Build on ideas, and draw connections between different suggestions to further the problem solving process.

Brainstorming techniques and processes helps your team innovate and work collaboratively. There’s no single right way to hold a brainstorming session. In fact, holding individual or reverse brainstorming sessions can both be helpful activities for generating new ideas.

Your goal should always be to use the process that works best for you and your team.

Eight reasons why brainstorming is important?

If you’ve ever held a brainstorming session, you likely know that they can be very effective for generating new ideas, and finding solutions to a problem. This is largely due to the many advantages of brainstorming that help teams work more collaboratively towards a common goal.

Some of the advantages of brainstorming for businesses and individual productivity include:

- Brainstorming allows people to think more freely, without fear of judgment.

- Brainstorming encourages open and ongoing collaboration to solve problems and generate innovative ideas.

- Brainstorming helps teams generate a large number of ideas quickly, which can be refined and merged to create the ideal solution.

- Brainstorming allows teams to reach conclusions by consensus, leading to a more well-rounded and better informed path forward.

- Brainstorming helps team members feel more comfortable bouncing ideas off one another, even outside of a structured session.

- Brainstorming introduces different perspectives, and opens the door to out-of-the-box innovations.

- Brainstorming helps team members get ideas out of their heads and into the world, where they can be expanded upon, refined, and put into action.

- Brainstorming is great for team building. No one person has ownership over the results, enabling an absolute team effort.

In summary, the core advantages of brainstorming are its ability to unlock creativity by collaboration. It’s the perfect technique to use for coming together as a team, and can help to generate exciting new ideas that can take your business to a new level.

Now that we’ve established what brainstorming is, and why it’s important, let’s take a look at some examples of scenarios where it would be useful.

Examples of when to use brainstorming

As you can probably guess, brainstorming is a technique that can be used in a wide variety of different situations. It can be in both your personal and professional life to help you find new ideas and solutions to different problems you’re working on.

Because of this versatility, brainstorming is a widely used technique among companies and teams of all sizes.

To get you thinking about where you can use brainstorming, here are some examples of scenarios when this technique might be useful.

Scenario #1

Your content and product marketing teams need to generate new messaging ideas for an upcoming product launch. You have a set of new features that you know will be exciting for your users, but you’re struggling to find the right words to convey their importance and benefits.

Calling a brainstorming session to generate new messaging ideas would be a perfect way to start this writing process. As a team, you can throw as many ideas and slogans together as you can, and then refine them together to get a clear picture of the direction going forward.

Scenario #2

You’ve been tasked by your executive team to come up with a growth strategy for the coming fiscal year, which focuses on expanding your footprint into your most successful markets. You know that there is room for growth, but aren’t sure which areas to focus on.

Gathering the key stakeholders in your department and across the organization for a brainstorming session will help you quickly gather a list of growth opportunities. Each team member will have their own ideas for growth within their role which can be added to a longer list of strategic possibilities.

Scenario #3

Your product development team has been repeatedly running into an issue with a new version of your software. Because of the complexity of the project, it’s difficult to tell what the root cause of the problem might be.

Calling your product team together for a brainstorming session will help you gather opinions on what the issue might be. As more theories come forth, it’s likely that a consensus will start to form about where the core issue lies. From there, you can brainstorm ways to fix the problem.

These are just three high level examples of brainstorming. This technique is incredibly versatile, and can be applied to virtually any problem or goal that your business needs to address.

The advantages of brainstorming are many, and we highly recommend that you start to incorporate it more throughout your business operations.

MindManager® is an innovative visual productivity solution that offers a variety of pre-built templates to help you visualize projects more effectively, including Kanban boards, Gantt charts, Flowcharts, and more.

Download a free trial of MindManager today to get started with brainstorming!

Ready to take the next step?

MindManager helps boost collaboration and productivity among remote and hybrid teams to achieve better results, faster.

Why choose MindManager?

MindManager® helps individuals, teams, and enterprises bring greater clarity and structure to plans, projects, and processes. It provides visual productivity tools and mind mapping software to help take you and your organization to where you want to be.

Explore MindManager

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Brainstorming

What is brainstorming.

Brainstorming is a method design teams use to generate ideas to solve clearly defined design problems. In controlled conditions and a free-thinking environment, teams approach a problem by such means as “How Might We” questions. They produce a vast array of ideas and draw links between them to find potential solutions.

- Transcript loading…

How To Use Brainstorming Best

Brainstorming is part of design thinking . You use it in the ideation phase. It’s extremely popular for design teams because they can expand in all directions. Although teams have rules and a facilitator to keep them on track, they are free to use out-of-the-box and lateral thinking to seek the most effective solutions to any design problem. By brainstorming, they can take a vast number of approaches—the more, the better—instead of just exploring conventional means and running into the associated obstacles. When teams work in a judgment-free atmosphere to find the real dimensions of a problem, they’re more likely to produce rough answers which they’ll refine into possible solutions later. Marketing CEO Alex Osborn, brainstorming’s “inventor”, captured the refined elements of creative problem-solving in his 1953 book, Applied Imagination . In brainstorming, we aim squarely at a design problem and produce an arsenal of potential solutions. By not only harvesting our own ideas but also considering and building on colleagues’, we cover the problem from every angle imaginable.

“It is easier to tone down a wild idea than to think up a new one.” — Alex Osborn

Everyone in a design team should have a clear definition of the target problem. They typically gather for a brainstorming session in a room with a large board/wall for pictures/Post-Its. A good mix of participants will expand the experience pool and therefore broaden the idea space.

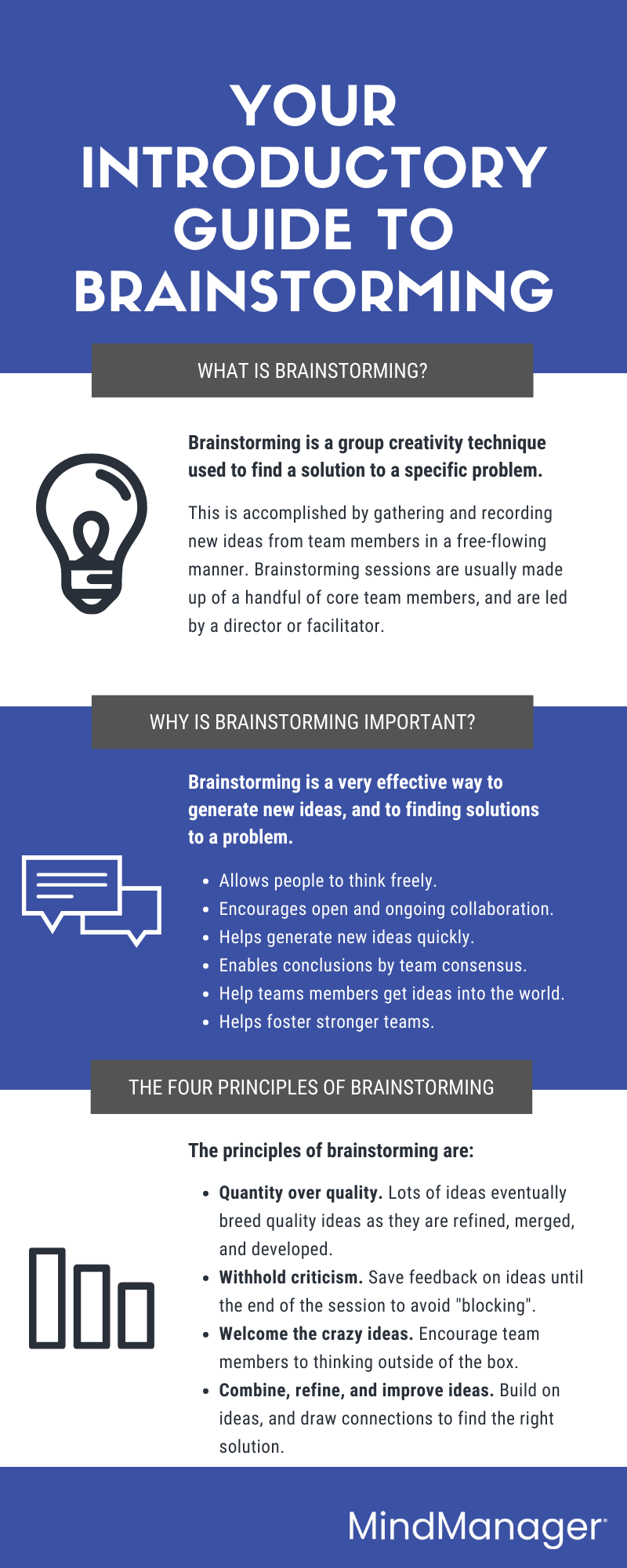

Brainstorming may seem to lack constraints, but everyone must observe eight house rules and have someone acting as facilitator.

Set a time limit – Depending on the problem’s complexity, 15–60 minutes is normal.

Begin with a target problem/brief – Members should approach this sharply defined question, plan or goal and stay on topic.

Refrain from judgment/criticism – No-one should be negative (including via body language) about any idea.

Encourage weird and wacky ideas – Further to the ban on killer phrases like “too expensive”, keep the floodgates open so everyone feels free to blurt out ideas (provided they’re on topic).

Aim for quantity – Remember, “quantity breeds quality”. The sifting-and-sorting process comes later.

Build on others’ ideas – It’s a process of association where members expand on others’ notions and reach new insights, allowing these ideas to trigger their own. Say “and”—rather than discourage with “but”—to get ideas closer to the problem.

Stay visual – Diagrams and Post-Its help bring ideas to life and help others see things in different ways.

Allow one conversation at a time – To arrive at concrete results, it’s essential to keep on track this way and show respect for everyone’s ideas.

To capture everyone’s ideas in a brainstorming session, someone must play “scribe” and mark every idea on the board. Alternatively, write down your own ideas as they come, and share these with the group. Often, design problems demand mixed tactics: brainstorming and its sibling approaches – braindumping (for individuals), and brainwriting and brainwalking (for group-and-individual mixes).

Take Care with Brainstorming

Brainstorming involves harnessing synergy – we leverage our collective thinking towards a variety of potential solutions. However, it’s challenging to have boundless freedom. In groups, introverts may stay quiet while extroverts dominate. Whoever’s leading the session must “police” the team to ensure a healthy, solution-focused atmosphere where even the shiest participants will speak up. A warm-up activity can cure brainstorming “constipation” – e.g., ask participants to list ways the world would be different if metal were like rubber.

Another risk is to let the team stray off topic and/or address other problems. As we may use brainstorming in any part of our design process—including areas related to a project’s main scope—it’s vital that participants stick to the problem relevant to that part (what Osborn called the “Point of View”). Similarly, by framing problems with “How Might We” questions, we remember brainstorming is organic and free of boundaries. Overall, your team should stay fluid in the search for ways you might resolve an issue – not chase a “holy grail” solution someone has developed elsewhere. The idea is to mine idea “ore” and refine “golden” solutions from it later.

How to Supercharge Brainstorming with AI

Learn more about brainstorming.

The Interaction Design Foundation’s course on Design Thinking discusses Brainstorming in depth.

This blog offers incisive insights into Brainstorming workshops .

Jonathan Courtney’s article for Smashing Magazine shows Brainstorming’s versatility .

Literature on Brainstorming

Here’s the entire UX literature on Brainstorming by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Brainstorming

Take a deep dive into Brainstorming with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Some of the world’s leading brands, such as Apple, Google, Samsung, and General Electric, have rapidly adopted the design thinking approach, and design thinking is being taught at leading universities around the world, including Stanford d.school, Harvard, and MIT. What is design thinking, and why is it so popular and effective?

Design Thinking is not exclusive to designers —all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering and business have practiced it. So, why call it Design Thinking? Well, that’s because design work processes help us systematically extract, teach, learn and apply human-centered techniques to solve problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, businesses, countries and lives. And that’s what makes it so special.

The overall goal of this design thinking course is to help you design better products, services, processes, strategies, spaces, architecture, and experiences. Design thinking helps you and your team develop practical and innovative solutions for your problems. It is a human-focused , prototype-driven , innovative design process . Through this course, you will develop a solid understanding of the fundamental phases and methods in design thinking, and you will learn how to implement your newfound knowledge in your professional work life. We will give you lots of examples; we will go into case studies, videos, and other useful material, all of which will help you dive further into design thinking. In fact, this course also includes exclusive video content that we've produced in partnership with design leaders like Alan Dix, William Hudson and Frank Spillers!

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete design thinking project. The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a design thinking practitioner. What’s equally important is you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in the world of human-centered design.

Design thinking methods and strategies belong at every level of the design process . However, design thinking is not an exclusive property of designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering, and business have practiced it. What’s special about design thinking is that designers and designers’ work processes can help us systematically extract, teach, learn, and apply these human-centered techniques in solving problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, in our businesses, in our countries, and in our lives.

That means that design thinking is not only for designers but also for creative employees , freelancers , and business leaders . It’s for anyone who seeks to infuse an approach to innovation that is powerful, effective and broadly accessible, one that can be integrated into every level of an organization, product, or service so as to drive new alternatives for businesses and society.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight them on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or your website .

All open-source articles on Brainstorming

Stage 3 in the design thinking process: ideate.

- 1.2k shares

- 4 years ago

14 UX Deliverables: What will I be making as a UX designer?

Introduction to the Essential Ideation Techniques which are the Heart of Design Thinking

- 1.1k shares

- 3 years ago

Learn How to Use the Best Ideation Methods: Brainstorming, Braindumping, Brainwriting, and Brainwalking

Three Ideation Methods to Enhance Your Innovative Thinking

Ideation for Design - Preparing for the Design Race

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share the knowledge!

Share this content on:

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

What is brainstorming?

Table of contents

Definition of brainstorming.

Brainstorming is a creative thinking technique for coming up with new ideas and solving problems. Teams use this ideation method to encourage new ways of thinking and collectively generate solutions. Brainstorming encourages free thinking and allows for all ideas to be voiced without judgment, fostering an open and innovative environment. This process typically involves a group of people, although it can be done individually as well.

This guide will help you get the most out of every creative session. When you're ready to start your next free thinking exercise, jump into Miro’s brainstorming tool to generate ideas and turn them into action.

What is the main purpose of brainstorming?

The primary purpose of a brainstorming session is to generate and document many ideas, no matter how “out there” they might seem. Through this lateral thinking process, inventive ideas are suggested, which sparks creative solutions. By encouraging everyone to think more freely and not be afraid to share their ideas, teams can build on each other’s thoughts to find the best possible solution to a problem. Brainstorming usually takes place in a group setting where people get together to creatively solve problems and come up with ideas. However, it’s also useful for individuals who need to explore novel solutions to a problem. Sitting down by yourself and writing down solutions to potential problems is a great way to brainstorm individually. Focusing your mind on a defined problem allows you to think of many creative ways to get to an answer. While brainstorming normally allows for free-form methods of thinking and doesn’t require many rules, the best results usually stem from controlled sessions. Posing questions and role-playing different scenarios during the brainstorming session is a smart way to pull out unusual ideas and never-before-thought-of solutions.

Benefits of brainstorming

Why is brainstorming such a popular approach to solving problems and generating ideas? Here are some of its many advantages:

Encourages creativity

Brainstorming sessions are meant to be free of judgment. Everyone involved is meant to feel safe and confident enough to speak their minds. There will be some good and some bad ideas, but this doesn’t matter as long as the final outcome is one that can solve the problem. This kind of free-thinking environment, along with a few essential brainstorming rules, encourage creativity in the workplace.

Fosters collaboration and team building

Brainstorming is not only good for problem-solving. It also allows employees and team members to understand how the people around them think. It helps the team get to know each other’s strengths and weaknesses and helps build a more inclusive and close-knit workforce.

Generates innovative, revolutionary ideas

Brainstorming is the perfect mix between a free-thinking, creative environment and one that is governed by rules. Being faced with a defined problem or asking questions like “What do we do in X scenario?” forces everyone in the room to come up with ideas and solutions. No two people think alike. So, combining the good parts of everyone’s answers will result in holistic and revolutionary solutions.

Establishes different perspectives

One of the major benefits of brainstorming is that it allows and encourages all members of the session to freely propose ideas. This type of environment fosters courage in people who may not usually offer their perspective on a problem. Garnering a range of different perspectives can lead to a never-before-thought-of solution.

Introduces many ideas quickly

The beauty of brainstorming is that it encourages teams to come up with many ideas in a relatively short period of time. Ideas are thrown around, and every train of thought is documented. Different perspectives give different answers, and sifting through a few good answers in quick succession may lead to the perfect solution in no time.

Types of brainstorming techniques

There are plenty of creative brainstorming techniques to choose from. Here are some of the most popular ones:

Reverse brainstorming

In a typical brainstorming session, the group is asked to consider solutions to a problem. This means that they will spend time thinking about the outcome — the end goal — rather than the root of the problem — the starting point. Reverse brainstorming is simply the opposite: teams are asked to ideate on the problem instead of the solution. This type of brainstorming is done before the start of an important project, as it helps teams anticipate any future obstacles that might arise. To help frame this way of thinking, use a Reverse Brainstorming Template to get the team started.

Random word brainstorming

One of the main goals of a brainstorming session is to come up with new ideas. One of the best ways to do this is to say the first words that come to mind when a specific topic or subject is mentioned. Random word brainstorming allows for exactly that. The team is given a problem, and they need to shout out the first words that they think of, regardless of what they are. These words are then written down and later put into interesting combinations to see if they will lead to a usable solution. This brainstorming method is extremely fast and usually very efficient at solving a defined problem. The Random Words Brainstorming Template can help get you started.

The 5 Whys Method

Like the reverse brainstorming method, the 5 Whys method aims to look at the root causes of a problem to stop that same issue from arising again. This method attempts to curb the problem before it can reoccur by asking the question “why?” over and over until it can no longer be answered. Once you reach this stage, you have arrived at the root cause of the issue.

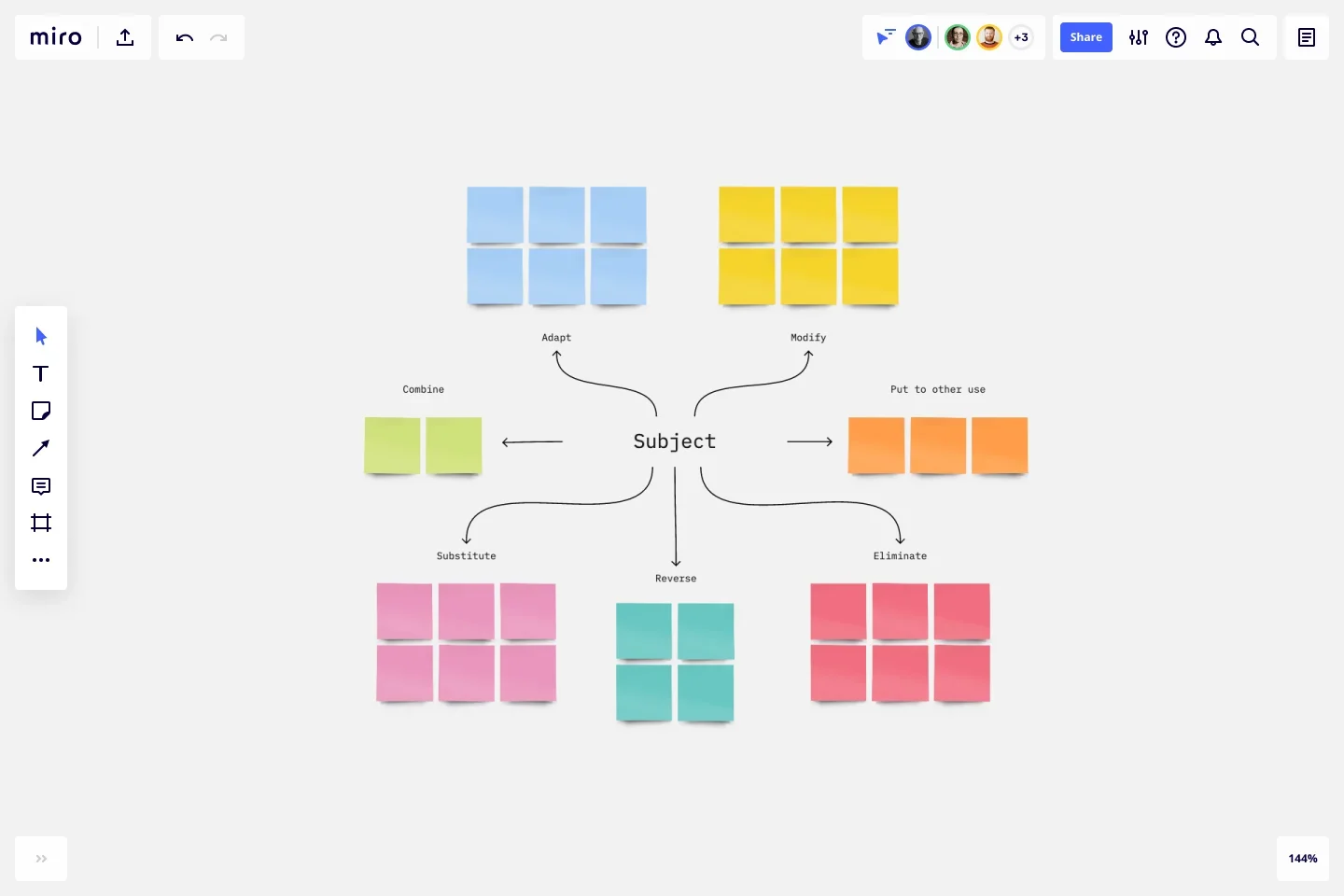

SCAMPER model

Developed by Bob Earle, an author of creativity books for kids, the SCAMPER model was originally a game aimed at imagination development in adolescents. It has, however, become popular in the corporate world as a means of improving and encouraging creativity in team members when dealing with complex, defined problems. Using this model, your team will view a problem through 7 filters: substitute, combine, adapt, modify, put to another use, eliminate, and reverse.

Rapid ideation

Rapid ideation brainstorming is almost the exact same thinking model as random word brainstorming. In this method, however, everyone writes down the solutions they are thinking of instead of shouting them out. This gives participants a bit more privacy with their immediate thoughts — possibly leading to even more creative and revolutionary outcomes.

Starbursting

Once again, brainstorming can change based on the team’s perspective and each session’s expected outcome. Starburst brainstorming focuses on getting the team to ask questions instead of coming up with answers.

How to hold a brainstorming workshop

Ready to harness the power of a well-run brainstorming session? Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to organize a successful brainstorming workshop:

1. Assign a facilitator

When done as a group, a brainstorming session needs to have boundaries. You need to choose someone who will facilitate the session and provide guidelines for the thinking exercises that the group will partake in. This is so the session doesn’t get too scattered and stays on the right track. The facilitator should pose questions and guide the group from start to finish.

2. Establish context and ensure group understanding

A brainstorming session cannot be properly carried out without context. The group must understand why they are meeting and what the end goal of the session is. Everyone should also understand the meaning of brainstorming and what to expect from the brainstorming process. The brainstorming method that will be used should also be established (see point 5) and explained at the outset.

3. Define an objective

While brainstorming is often looked at as a form of free-thinking creativity, it is best to try to stay within certain rules. It’s essential that you define a clear objective and use the session to reach your predetermined goal.

4. Set a time limit

Setting a defined time limit before the session starts is important to the success of your brainstorming session. No doubt your team could come up with countless ideas, but there has to be a limit on how long the session can run. Knowing that you need to solve a problem within one hour, for instance, will help the team focus on the job at hand and come up with ideas faster. It will also keep everyone thinking about the same problem.

5. Decide on the brainstorming technique

The brainstorming technique that will be used must be decided on before the session begins. The best way to do this is to look at the problem at hand. If you’re looking to prevent obstacles from arising in the future, try the “5 Whys” technique. If you’re looking to come up with new marketing ideas or get creative with workplace conflicts, try the rapid ideation technique.

6. Set some ground rules

As stated above, the best and most productive brainstorming sessions are those that allow for free thinking and creativity within preset boundaries. Brainstorming ground rules are essential to to the success of the session, as they keep everyone focused on the topic at hand and ensure that no one goes off track.

7. Capture all ideas

The entire point of a brainstorming session is to come up with as many ideas as possible, regardless of whether the standalone suggestion will lead to success. This means that you need to use the right tools to document the ideas being suggested. Miro has a host of idea-capturing tools, including a simple-to-use visual platform for remote brainstorming sessions and digital sticky notes .

8. Discuss and vote on ideas

After all the ideas have been captured, it’s time to discuss them. The team needs to be productive in choosing a creative idea that suits the problem, or they can try combining a few ideas to come up with a holistic solution. To make decisions as a group and come to an agreement, teams can use the dot voting method . This technique reveals group priorities and helps everyone reach a consensus on the direction to take.

9. Turn ideas into action

Once the final idea has been chosen, it’s time to create a plan of action and a deadline for the idea to be put in place. Transform your ideas into detailed, tangible steps with the Action Plan Template . This will help with coordination between team members and ensures that nothing is missed.

Tips for your brainstorming activities

While all brainstorming sessions look a little different, here are some best practices to get the most out of yours:

Record all ideas

If you want to have a successful and productive brainstorming session, it’s important that you capture every idea suggested, good and bad. An idea might seem silly when first brought up, but it might become an invaluable idea as the session moves on. Capture everything, and right at the end, work out which ideas best suit the problem.

Ensure that everyone’s ideas are heard

When brainstorming is done as a group activity, everyone needs to feel comfortable and confident to propose ideas. The best way to make sure the environment fosters these feelings is to make the session feel like a conversation, not a presentation. Create a safe and open environment that gives everyone equal opportunity to voice their opinions and ideas.

Focus on quantity

People often like to say, "Focus on quality, not quantity," but it’s the opposite when brainstorming. In a brainstorming session, you should focus on getting as many ideas on the board as possible, even if they're only one-word ideas. These can all be used to come to a holistic solution at the end of the session. Each suggestion could be invaluable if you're coming up with a combined idea.

Brainstorming should be a fun and creative endeavor. You shouldn’t be too rigid — though some ground rules are important. If your team has weekly brainstorming sessions, try new brainstorming techniques and activities each time you meet. This will keep your team members on their toes and help make them excited about the next meeting. It will also encourage out-of-the-box thinking, which is essential to any successful brainstorming session.

Avoid criticism

We’ll say it again: there are no bad ideas in a brainstorming session. This is the attitude that all team members must adopt when entering the session. No one should be criticized for the ideas that they propose. The best way to foster an environment that is devoid of criticism and encourages creativity is to maintain a relaxed approach. This will make everyone feel comfortable and happy to contribute their ideas.

Discover more

Guide to collaborative brainstorming

When to use brainstorming (and which techniques are best)

What is brainwriting?

What is reverse brainstorming?

How to conduct a brainstorming session

Get on board in seconds

Join thousands of teams using Miro to do their best work yet.

Seven steps to better brainstorming

Companies run on good ideas. From R&D groups seeking pipelines of innovative new products to ops teams probing for time-saving process improvements to CEOs searching for that next growth opportunity—all senior managers want to generate better and more creative ideas consistently in the teams they form, participate in, and manage.

Yet all senior managers, at some point, experience the pain of pursuing new ideas by way of traditional brainstorming sessions—still the most common method of using groups to generate ideas at companies around the world. The scene is familiar: a group of people, often chosen largely for political reasons, begins by listening passively as a moderator (often an outsider who knows little about your business) urges you to “Get creative!” and “Think outside the box!” and cheerfully reminds you that “There are no bad ideas!”

The result? Some attendees remain stone-faced throughout the day, others contribute sporadically, and a few loudly dominate the session with their pet ideas. Ideas pop up randomly—some intriguing, many preposterous—but because the session has no structure, little momentum builds around any of them. At session’s end, the group trundles off with a hazy idea of what, if anything, will happen next. “Now we can get back to real work,” some whisper.

It doesn’t have to be like this. We’ve led or observed 200 projects over the past decade at more than 150 companies in industries ranging from retailing and education to banking and communications. That experience has helped us develop a practical approach that captures the energy typically wasted in a traditional brainstorming session and steers it in a more productive direction. The trick is to leverage the way people actually think and work in creative problem-solving situations.

We call our approach “brainsteering,” and while it requires more preparation than traditional brainstorming, the results are worthwhile: better ideas in business situations as diverse as inventing new products and services, attracting new customers, designing more efficient business processes, or reducing costs, among others. The next time you assign one of your people to lead an idea generation effort—or decide to lead one yourself—you can significantly improve the odds of success by following the seven steps below.

1. Know your organization’s decision-making criteria

One reason good ideas hatched in corporate brainstorming sessions often go nowhere is that they are beyond the scope of what the organization would ever be willing to consider. “Think outside the box!” is an unhelpful exhortation if external circumstances or company policies create boxes that the organization truly must live within.

Managers hoping to spark creative thinking in their teams should therefore start by understanding (and in some cases shaping) the real criteria the company will use to make decisions about the resulting ideas. Are there any absolute restrictions or limitations, for example? A bank we know wasted a full day’s worth of brainstorming because the session’s best ideas all required changing IT systems. Yet senior management—unbeknownst to the workshop planners—had recently “locked down” the IT agenda for the next 18 months.

Likewise, what constitutes an acceptable idea? At a different, smarter bank, workshop planners collaborated with senior managers on a highly specific (and therefore highly valuable) definition tailored to meet immediate needs. Good ideas would require no more than $5,000 per branch in investment and would generate incremental profits quickly. Further, while three categories of ideas—new products, new sales approaches, and pricing changes—were welcome, senior management would balk at ideas that required new regulatory approvals. The result was a far more productive session delivering exactly what the company wanted: a fistful of ideas, in all three target categories, that were practical, affordable, and profitable within one fiscal year.

2. Ask the right questions

Decades of academic research shows that traditional, loosely structured brainstorming techniques (“Go for quantity—the greater the number of ideas, the greater the likelihood of winners!”) are inferior to approaches that provide more structure. 1 1. For two particularly useful academic studies on the ineffectiveness and inefficiency of traditional brainstorming, see Paul A. Mongeau, The Brainstorming Myth , Annual Meeting of the Western States Communication Association, Albuquerque, New Mexico, February 15, 1993; and Frederic M. Jablin and David R. Seibold, “Implications for problem solving groups of empirical research on ‘brainstorming’: A critical review of the literature,” Southern Speech Communication Journal , 1978, Volume 43, Number 4, pp. 327–56. The best way we’ve found to provide it is to use questions as the platform for idea generation.

In practice, this means building your workshop around a series of “right questions” that your team will explore in small groups during a series of idea generation sessions (more about these later). The trick is to identify questions with two characteristics. First, they should force your participants to take a new and unfamiliar perspective. Why? Because whenever you look for new ways to attack an old problem—whether it’s lowering your company’s operating costs or buying your spouse a birthday gift—you naturally gravitate toward thinking patterns and ideas that worked in the past. Research shows that, over time, you’ll come up with fewer good ideas, despite increased effort. Changing your participants’ perspective will shake up their thinking. (For more on how to do this, see “ Sparking creativity in teams: An executive’s guide .”) The second characteristic of a right question is that it limits the conceptual space your team will explore, without being so restrictive that it forces particular answers or outcomes.

It’s easier to show such questions in practice than to describe them in theory. A consumer electronics company looking to develop new products might start with questions such as “What’s the biggest avoidable hassle our customers endure?” and “Who uses our product in ways we never expected?” By contrast, a health insurance provider looking to cut costs might ask, “What complexity do we plan for daily that, if eliminated, would change the way we operate?” and “In which areas is the efficiency of a given department ‘trapped’ by outdated restrictions placed on it by company policies?” 2 2. For a full discussion about identifying and using a portfolio of such right questions in the generation of personal and institutional ideas, see Brainsteering , the book from which this article is adapted, as well as Patricia Gorman Clifford, Kevin P. Coyne, and Renée Dye, “Breakthrough thinking from inside the box,” Harvard Business Review , December 2007, Volume 85, Number 12, pp. 70–78.

In our experience, it’s best to come up with 15 to 20 such questions for a typical workshop attended by about 20 people. Choose the questions carefully, as they will form the heart of your workshop—your participants will be discussing them intensively in small subgroups during a series of sessions.

3. Choose the right people

The rule here is simple: pick people who can answer the questions you’re asking. As obvious as this sounds, it’s not what happens in many traditional brainstorming sessions, where participants are often chosen with less regard for their specific knowledge than for their prominence on the org chart.

Instead, choose participants with firsthand, “in the trenches” knowledge, as a catalog retailer client of ours did for a brainsteering workshop on improving bad-debt collections. (The company had extended credit directly to some customers). During the workshop, when participants were discussing the question “What’s changed in our operating environment since we last redesigned our processes?” a frontline collections manager remarked, “Well, death has become the new bankruptcy.”

A few people laughed knowingly, but the senior managers in the room were perplexed. On further discussion, the story became clear. In years past, some customers who fell behind on their payments would falsely claim bankruptcy when speaking with a collections rep, figuring that the company wouldn’t pursue the matter because of the legal headaches involved. More recently, a better gambit had emerged: unscrupulous borrowers instructed household members to tell the agent they had died—a tactic that halted collections efforts quickly, since reps were uncomfortable pressing the issue.

While this certainly wasn’t the largest problem the collectors faced, the line manager’s presence in the workshop had uncovered an opportunity. A different line manager in the workshop proposed what became the solution: instructing the reps to sensitively, but firmly, question the recipient of the call for more specific information if the rep suspected a ruse. Dishonest borrowers would invariably hang up if asked to identify themselves or to provide other basic information, and the collections efforts could continue.

4. Divide and conquer

To ensure fruitful discussions like the one the catalog retailer generated, don’t have your participants hold one continuous, rambling discussion among the entire group for several hours. Instead, have them conduct multiple, discrete, highly focused idea generation sessions among subgroups of three to five people—no fewer, no more. Each subgroup should focus on a single question for a full 30 minutes. Why three to five people? The social norm in groups of this size is to speak up, whereas the norm in a larger group is to stay quiet.

When you assign people to subgroups, it’s important to isolate “idea crushers” in their own subgroup. These people are otherwise suitable for the workshop but, intentionally or not, prevent others from suggesting good ideas. They come in three varieties: bosses, “big mouths,” and subject matter experts.

The boss’s presence, which often makes people hesitant to express unproven ideas, is particularly damaging if participants span multiple organizational levels. (“Speak up in front of my boss’s boss? No, thanks!”) Big mouths take up air time, intimidate the less confident, and give everyone else an excuse to be lazy. Subject matter experts can squelch new ideas because everyone defers to their presumed superior wisdom, even if they are biased or have incomplete knowledge of the issue at hand.

By quarantining the idea crushers—and violating the old brainstorming adage that a melting pot of personalities is ideal—you’ll free the other subgroups to think more creatively. Your idea crushers will still be productive; after all, they won’t stop each other from speaking up.

Finally, take the 15 to 20 questions you prepared earlier and divide them among the subgroups—about 5 questions each, since it’s unproductive and too time consuming to have all subgroups answer every question. Whenever possible, assign a specific question to the subgroup you consider best equipped to handle it.

5. On your mark, get set, go!

After your participants arrive, but before the division into subgroups, orient them so that your expectations about what they will—and won’t—accomplish are clear. Remember, your team is accustomed to traditional brainstorming, where the flow of ideas is fast, furious, and ultimately shallow.

Today, however, each subgroup will thoughtfully consider and discuss a single question for a half hour. No other idea from any source—no matter how good—should be mentioned during a subgroup’s individual session. Tell participants that if anyone thinks of a “silver bullet” solution that’s outside the scope of discussion, they should write it down and share it later.

Prepare your participants for the likelihood that when a subgroup attacks a question, it might generate only two or three worthy ideas. Knowing that probability in advance will prevent participants from becoming discouraged as they build up the creative muscles necessary to think in this new way. The going can feel slow at first, so reassure participants that by the end of the day, after all the subgroups have met several times, there will be no shortage of good ideas.

Also, whenever possible, share “signpost examples” before the start of each session—real questions previous groups used, along with success stories, to motivate participants and show them how a question-based approach can help.

One last warning: no matter how clever your participants, no matter how insightful your questions, the first five minutes of any subgroup’s brainsteering session may feel like typical brainstorming as people test their pet ideas or rattle off superficial new ones. But participants should persevere. Better thinking soon emerges as the subgroups try to improve shallow ideas while sticking to the assigned questions.

6. Wrap it up

By day’s end, a typical subgroup has produced perhaps 15 interesting ideas for further exploration. You’ve been running multiple subgroups simultaneously, so your 20-person team has collectively generated up to 60 ideas. What now?

One thing not to do is have the full group choose the best ideas from the pile, as is common in traditional brainstorming. In our experience, your attendees won’t always have an executive-level understanding of the criteria and considerations that must go into prioritizing ideas for actual investment. The experience of picking winners can also be demotivating, particularly if the real decision makers overrule the group’s favorite choices later.

Instead, have each subgroup privately narrow its own list of ideas to a top few and then share all the leading ideas with the full group to motivate and inspire participants. But the full group shouldn’t pick a winner. Rather, close the workshop on a high note that participants won’t expect if they’re veterans of traditional brainstorming: describe to them exactly what steps will be taken to choose the winning ideas and how they will learn about the final decisions.

7. Follow up quickly

Decisions and other follow-up activities should be quick and thorough. Of course, we’re not suggesting that uninformed or insufficiently researched conclusions should be reached about ideas dreamed up only hours earlier. But the odds that concrete action will result from an idea generation exercise tend to decline quickly as time passes and momentum fades.

The president, provost, and department heads of a US university, for example, announced before a brainsteering workshop that a full staff meeting would be held the morning after it to discuss the various cost-savings ideas it had generated. At the meeting, the senior leaders sorted ideas into four buckets: move immediately to implementation planning, decide today to implement at the closest appropriate time (say, the beginning of the next academic year), assign a group to research the idea further, or reject right away. This process went smoothly because the team that ran the idea generation workshop had done the work up front to understand the criteria senior leaders would use to judge its work. The university began moving ahead on more than a dozen ideas that would ultimately save millions of dollars.

To close the loop with participants, the university made sure to communicate the results of the decisions quickly to everyone involved, even when an idea was rejected. While it might seem demoralizing to share bad news with a team, we find that doing so actually has the opposite effect. Participants are often desperate for feedback and eager for indications that they have at least been heard. By respectfully explaining why certain ideas were rejected, you can help team members produce better ideas next time. In our experience, they will participate next time, often more eagerly than ever.

Traditional brainstorming is fast, furious, and ultimately shallow. By scrapping these traditional techniques for a more focused, question-based approach, senior managers can consistently coax better ideas from their teams.

Kevin Coyne and Shawn Coyne, both alumni of McKinsey’s Atlanta office, are cofounders and managing directors of the Coyne Partnership, a boutique strategy consulting firm. This article is adapted from their book, Brainsteering: A Better Approach to Breakthrough Ideas (HarperCollins, March 2011).

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Using rivalry to spur innovation

Rethinking knowledge work: a strategic approach, using knowledge brokering to improve business processes.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

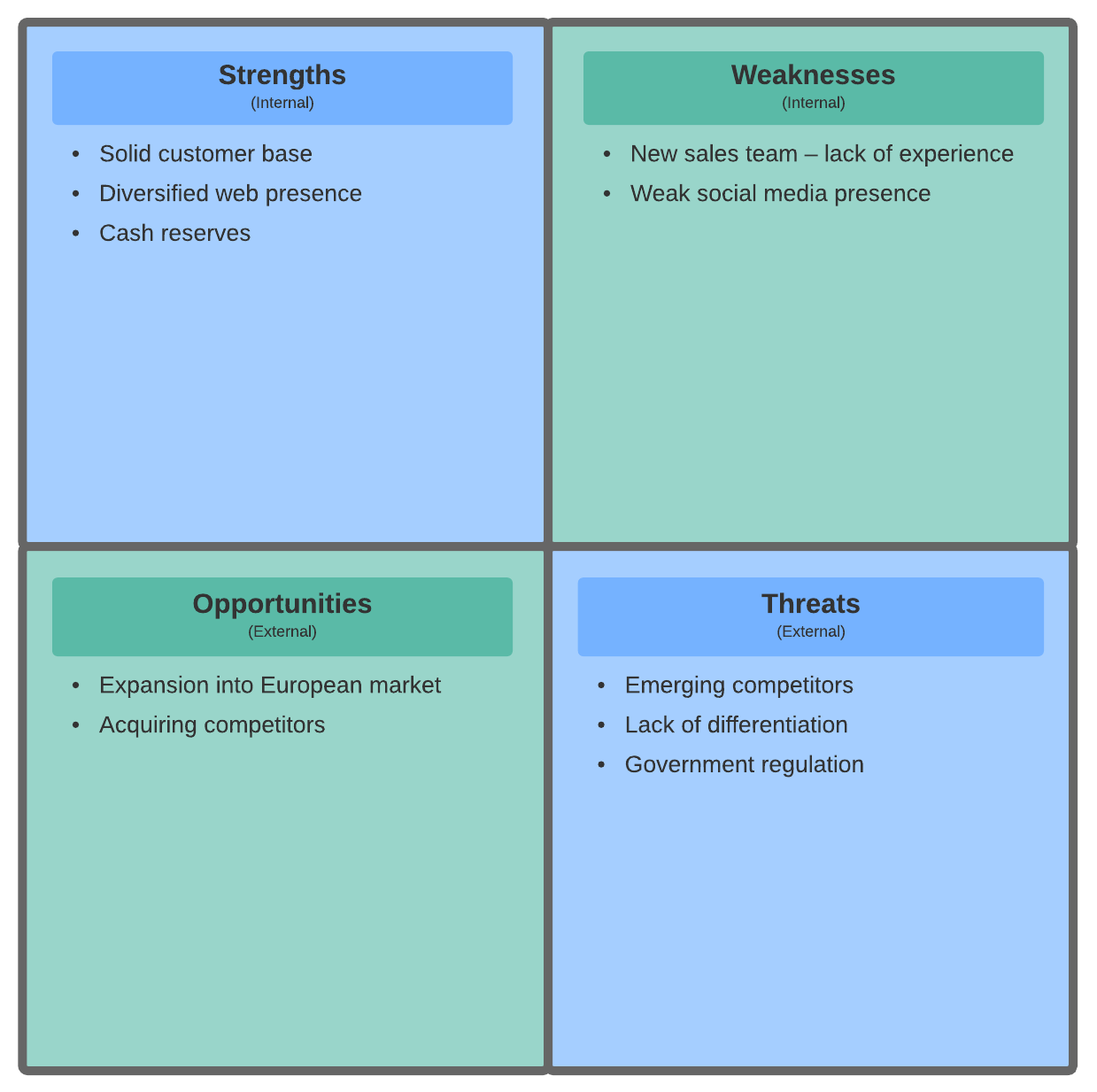

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time