The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientific research in the life sciences

Affiliations.

- 1 AXES, IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca, Lucca, Italy.

- 2 Chair of Systems Design D-MTEC, ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland.

- PMID: 35139089

- PMCID: PMC8827464

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263001

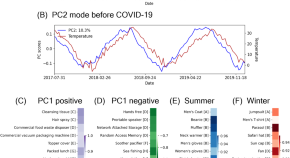

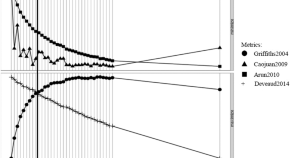

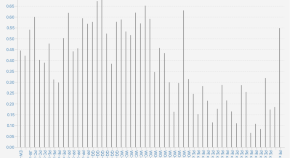

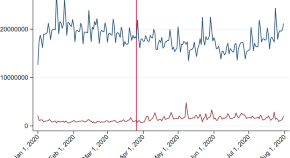

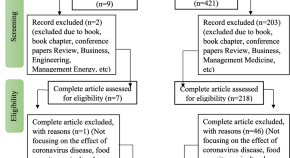

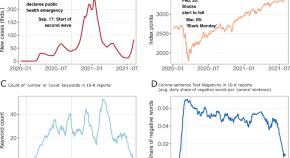

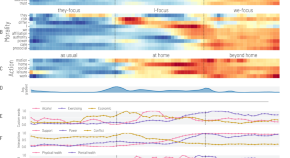

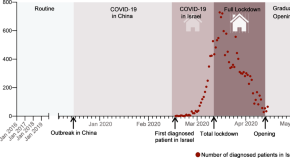

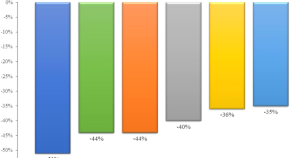

The COVID-19 outbreak has posed an unprecedented challenge to humanity and science. On the one side, public and private incentives have been put in place to promptly allocate resources toward research areas strictly related to the COVID-19 emergency. However, research in many fields not directly related to the pandemic has been displaced. In this paper, we assess the impact of COVID-19 on world scientific production in the life sciences and find indications that the usage of medical subject headings (MeSH) has changed following the outbreak. We estimate through a difference-in-differences approach the impact of the start of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientific production using the PubMed database (3.6 Million research papers). We find that COVID-19-related MeSH terms have experienced a 6.5 fold increase in output on average, while publications on unrelated MeSH terms dropped by 10 to 12%. The publication weighted impact has an even more pronounced negative effect (-16% to -19%). Moreover, COVID-19 has displaced clinical trial publications (-24%) and diverted grants from research areas not closely related to COVID-19. Note that since COVID-19 publications may have been fast-tracked, the sudden surge in COVID-19 publications might be driven by editorial policy.

- Bibliometrics

- Biological Science Disciplines

- Biomedical Research*

- COVID-19* / epidemiology

- Medical Subject Headings

Grants and funding

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Collection 23 July 2020

COVID-19: humanities and social sciences perspectives

The novel coronavirus SARS2-CoV-2 has precipitated the present outbreak of COVID-19, a highly infectious respiratory disease, for which there is presently no effective treatment. The resulting pandemic is having profound and likely long-lasting effects on communities, economies and individuals’ lived experiences. Here, we highlight research published across this journal that reflects in some way on this crisis from humanities and social sciences perspectives.

This collection will continue to be updated as relevant perspectives are published.

All papers submitted to Collections are subject to the journal’s standard editorial criteria and policies . This includes the journal’s policy on competing interests .

Viral decisions: unmasking the impact of COVID-19 info and behavioral quirks on investment choices

- Wasim ul Rehman

- Omur Saltik

- Suleyman Degirmen

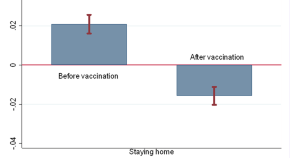

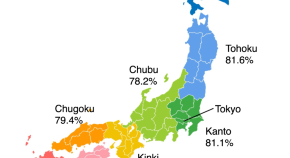

COVID-19 vaccination, preventive behaviours and pro-social motivation: panel data analysis from Japan

- Eiji Yamamura

- Yoshiro Tsutsui

- Fumio Ohtake

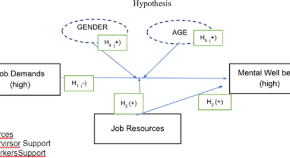

The determinants of mental well-being of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Nuria Ceular-Villamandos

- Virginia Navajas-Romero

- Maria Jesus Vazquez-Garcia

Pro-religion attitude predicts lower vaccination coverage at country level

- Zhe-Fei Mao

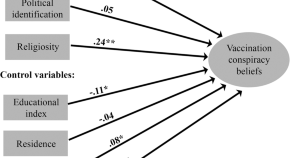

Health literacy, religiosity, and political identification as predictors of vaccination conspiracy beliefs: a test of the deficit and contextual models

- Željko Pavić

- Emma Kovačević

- Adrijana Šuljok

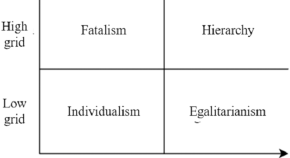

Cultural worldviews and support for governmental management of COVID-19

- Palizhati Muhetaer

Job satisfaction and self-efficacy of in-service early childhood teachers in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era

- Yan-Fang Zhou

- Atsushi Nanakida

Evidence of the time-varying impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on online search activities relating to shopping products in South Korea

- Kwangmin Jung

- Jonghun Kam

Multifractal scaling analyses of the spatial diffusion pattern of COVID-19 pandemic in Chinese mainland

- Yuqing Long

- Yanguang Chen

Nourishing social solidarity in exchanging gifts: a study on social exchange in Shanghai communities during COVID-19 lockdown

- Youjia Zhou

After the pandemic: the global seafood trade market forecasts in 2030

- Chunzhu Wei

- Wenguang Zhang

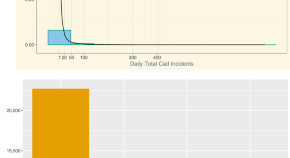

Car enthusiasm during the second and fourth waves of COVID-19 pandemic

- Michał Suchanek

- Agnieszka Szmelter-Jarosz

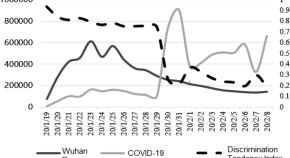

The effect of official intervention on reducing the use of potentially discriminatory language during the COVID-19 pandemic in China

- Yiwei Jiang

- Hsin-Che Wu

Public opinion in Japanese newspaper readers’ posts under the prolonged COVID-19 infection spread 2019–2021: contents analysis using Latent Dirichlet Allocation

- Hideaki Kasuga

- Tetsuhito Fukushima

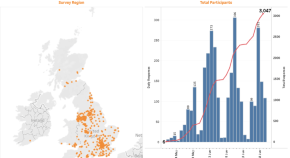

How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected wheelchair users? Time-series analysis of the number of railway passengers in Tokyo

- Yukari Niwa

- Kentaro Honma

Quiet quitting during COVID-19: the role of psychological empowerment

- Mingxiao Lu

- Abdullah Al Mamun

- Mohammad Masukujjaman

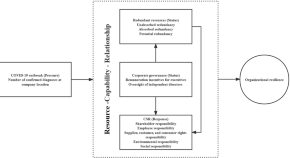

Pressure, state and response: configurational analysis of organizational resilience in tourism businesses following the COVID-19 pandemic crisis

Framing of female medical personnel during the covid-19 pandemic: a case study of the chinese official media.

- Cunling Gao

- Shanshan Han

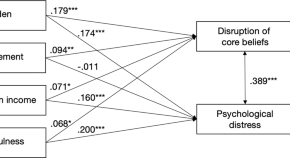

Cognitive and emotional factors related to COVID-19 among high-risk ethnically diverse adults at the onset of the New York City outbreak: A cross-sectional survey

- Rita Kukafka

- Mari Millery

- Alejandra N. Aguirre

Well-being of artisanal fishing communities and children’s engagement in fisheries amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a case in Aklan, Philippines

- Ronald J. Maliao

- Pepito R. Fernandez Jr

- Rodelio F. Subade

Sentiment and emotion in financial journalism: a corpus-based, cross-linguistic analysis of the effects of COVID

- Chelo Vargas-Sierra

- M. Ángeles Orts

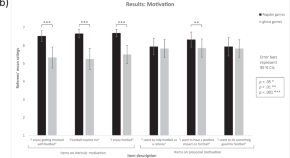

Subjective experience, self-efficacy, and motivation of professional football referees during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Fabio Richlan

- J. Lukas Thürmer

- Michael Christian Leitner

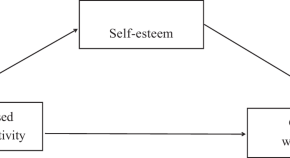

The relationship between home-based physical activity and general well-being among Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediation effect of self-esteem

- Yongzhen Teng

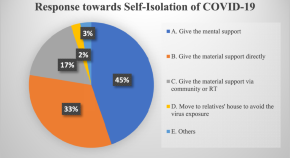

Integrating socio-cultural value system into health services in response to Covid-19 patients’ self-isolation in Indonesia

- Yety Rochwulaningsih

- Singgih Tri Sulistiyono

- Fajar Gemilang Purna Yudha

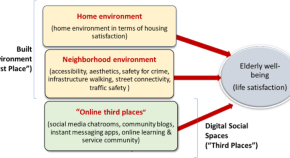

Assessing the significance of first place and online third places in supporting Malaysian seniors’ well-being during the pandemic

- Teck Hong Tan

- Izian Idris

Revival of positive nostalgic music during the first Covid-19 lockdown in the UK: evidence from Spotify streaming data

- Timothy Yu-Cheong Yeung

The impact of the first wave of COVID-19 on students’ attainment, analysed by IRT modelling method

- Rita Takács

- Szabolcs Takács

- Zoltán Horváth

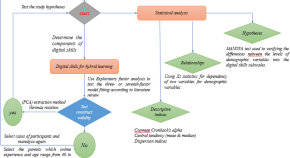

Parents’ digital skills and their development in the context of the Corona pandemic

- Badr A. Alharbi

- Usama M. Ibrahem

- Sameh F. Saleh

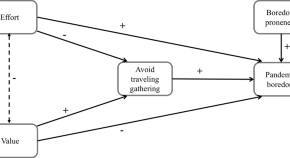

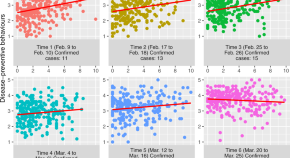

Effects of media on preventive behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Takahisa Suzuki

- Hitoshi Yamamoto

- Ryohei Umetani

Characteristics, likelihood and challenges of road traffic injuries in China before COVID-19 and in the postpandemic era

- Xiuquan Shi

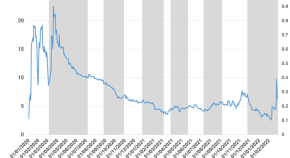

The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the connectedness of the BRICS’s term structure

- Francisco Jareño

- Ana Escribano

- Zaghum Umar

Moving forward: embracing challenges as opportunities to improve medical education in the post-COVID era

Pandemics affect every aspect of life, and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is no exception. The impact of COVID-19 might be even greater in medical education, which involves close contact with patients. This comment reviews current trends in medical education in response to COVID-19, especially in the pre-clerkship curriculum, and discusses opportunities and challenges in medical education in the post-pandemic era. COVID-19 has accelerated the adoption of online teaching and learning and is expected to boost innovation in medical education. First, blended learning, which is a mix of online and offline learning intended to incorporate the best of both worlds, is expected to become more widespread. Second, more novel approaches to learning that involve student-led initiatives likely become popular mediated by various technologies. Third, there will be more use of online learning resources and assessments. As online learning is expected to play a prominent role in the post-COVID-19 era, such transitions offer both opportunities and challenges. These challenges include faculty development on online teaching skills, creation and sharing of online resources, and effective design and implementation of online assessments. This comment calls for institutional support and collaborations for faculty development and for the development and sharing of learning resources, more models and guidelines for effective technology integration, and use of the virtual learning environment to promote student-centered learning to embrace the challenges as opportunities to improve medical education in the post-COVID era.

- Kyong-Jee Kim

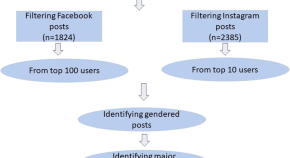

The gendered dimensions of the anti-mask and anti-lockdown movement on social media

- Ahmed Al-Rawi

- Maliha Siddiqi

- Julia Smith

Cyber violence caused by the disclosure of route information during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Yueting Zhou

- Xuefan Dong

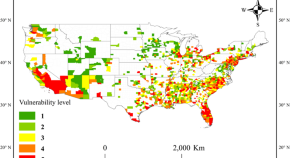

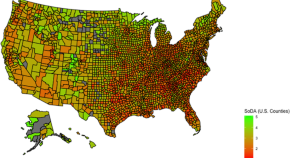

Social vulnerability amplifies the disparate impact of mobility on COVID-19 transmissibility across the United States

- Zhihui Huang

Factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy and reduced vaccine confidence in rural underserved populations

- Renee Robinson

- Elaine Nguyen

- Mary A. Nies

The system-wide effects of dispatch, response and operational performance on emergency medical services during Covid-19

- Ivan L. Pitt

Shining a light on an additional clinical burden: work-related digital communication survey study – COVID-19 impact on NHS staff wellbeing

- Ameet Bakhai

- Leah McCauley

- Derralynn Hughes

Biopolitics of othering during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Dušan Ristić

- Dušan Marinković

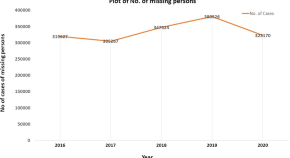

Counterfactual analysis of the impact of the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic on the reporting and registration of missing people in India

- Kandaswamy Paramasivan

- Brinda Subramani

- Nandan Sudarsanam

Empirical evidence of the impact of mobility on property crimes during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Rahul Subburaj

Impact of social determinants on COVID-19 infections: a comprehensive study from Saudi Arabia governorates

- Abdallah S. A. Yaseen

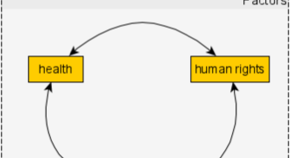

Containing COVID-19 and the social costs on human rights in African countries

- Lenore Manderson

- Diego Chavarro

- Henry Zakumumpa

Psychosocial indicators of individual behavior during COVID 19: Delphi approach

- Wijdan Abbas

- Shahla Eltayeb

Italians locked down: people’s responses to early COVID-19 pandemic public health measures

- Virginia Romano

- Mirko Ancillotti

- Roberta Biasiotto

Individuals’ willingness to provide geospatial global positioning system (GPS) data from their smartphone during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Yulin Hswen

- Ulrich Nguemdjo

- Bruno Ventelou

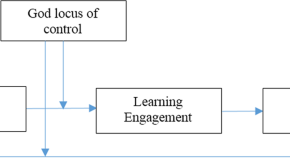

Loneliness, student engagement, and academic achievement during emergency remote teaching during COVID-19: the role of the God locus of control

- Hilmi Mizani

- Ani Cahyadi

- Santi Retno Sari

The importance of citizenship for deserving COVID-19 treatment

- Marc Helbling

- Rahsaan Maxwell

- Richard Traunmüller

Seeds and the city: a review of municipal home food gardening programs in Canada in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Janet Music

- Lisa Mullins

- Kydra Mayhew

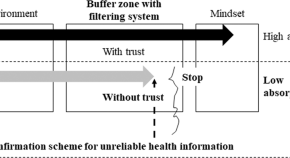

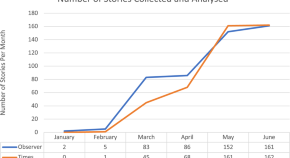

The usefulness of a checklist approach-based confirmation scheme in identifying unreliable COVID-19-related health information: a case study in Japan

- Nanae Tanemura

- Tsuyoshi Chiba

Reasoning COVID-19: the use of spatial metaphor in times of a crisis

- Dominik Kremer

- Tilo Felgenhauer

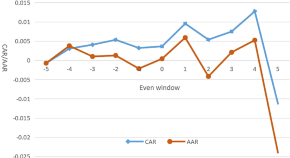

ESG performance and stock prices: evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak in China

- Liuhua Feng

- Hafiz M. Sohail

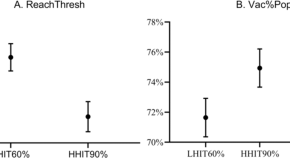

The effect of herd immunity thresholds on willingness to vaccinate

- Per A. Andersson

- Gustav Tinghög

- Daniel Västfjäll

COVID-19: a gray swan’s impact on the adoption of novel medical technologies

- Denise R. Dunlap

- Roberto S. Santos

- David D. McManus

Aggressive behaviour of anti-vaxxers and their toxic replies in English and Japanese

- Kunihiro Miyazaki

- Takayuki Uchiba

- Kazutoshi Sasahara

Psychometric properties of the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) among Malaysians during COVID-19: a methodological study

- Arulmani Thiyagarajan

- Tyler G. James

- Roy Rillera Marzo

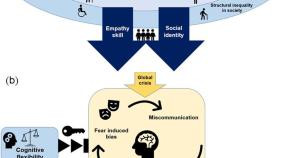

Intercultural discussion of conceptual universals in discourse: joint online methodology to bring about social change through novel conceptualizations of Covid-19

- Zsuzsanna Schnell

- Francesca Ervas

Social ties, fears and bias during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fragile and flexible mindsets

- Junya Fujino

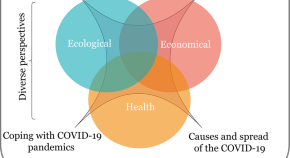

Perspectives of scholars on the origin, spread and consequences of COVID-19 are diverse but not polarized

- Prakash Kumar Paudel

- Rabin Bastola

- Subodh Adhikari

Impact of school closure due to COVID-19 on phonemic awareness of first-grade primary school children

- Kerem Coskun

Effects of social influence on crowdfunding performance: implications of the covid-19 pandemic

- Sirine Zribi

Generosity during COVID-19: investigating socioeconomic shocks and game framing

- Lorenzo Lotti

- Shanali Pethiyagoda

Who and which regions are at high risk of returning to poverty during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Mengxiao Liu

- Shengjie Lai

Major League Baseball during the COVID-19 pandemic: does a lack of spectators affect home advantage?

- Yung-Chin Chiu

- Chen-Kang Chang

Bibliometric analysis of trends in COVID-19 and tourism

- Alba Viana-Lora

- Marta Gemma Nel-lo-Andreu

Explore, engage, empower: methodological insights into a transformative mixed methods study tackling the COVID-19 lockdown

- Livia Fritz

- Ulli Vilsmaier

- Claudia R. Binder

The role of community leaders and other information intermediaries during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from the multicultural sector in Australia

- Holly Seale

- Ben Harris-Roxas

- Lisa Woodland

Using big data to understand the online ecology of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy

- Shasha Teng

- Kok Wei Khong

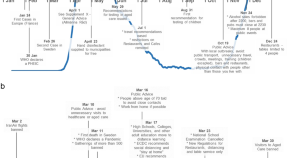

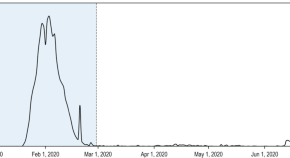

Online public opinion during the first epidemic wave of COVID-19 in China based on Weibo data

- Wen-zhong Shi

- Fanxin Zeng

- Zhicheng Shi

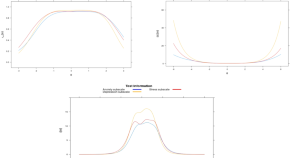

Vaccination and three non-pharmaceutical interventions determine the dynamics of COVID-19 in the US

- Mamadou Diagne

Disparities and intersectionality in social support networks: addressing social inequalities during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond

Pandemic in the digital age: analyzing WhatsApp communication behavior before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown

- Anika Seufert

- Fabian Poignée

- Michael Seufert

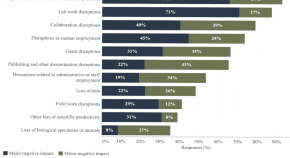

Producing knowledge in a pandemic: Accounts from UK-based postdoctoral biomedical scientists of undertaking research during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Jamie Beverstock

- Martyn Pickersgill

Optimising self-organised volunteer efforts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Anping Zhang

Individualism and the fight against COVID-19

- Oliver Zhen Li

- Zilong Zhang

Economic losses from COVID-19 cases in the Philippines: a dynamic model of health and economic policy trade-offs

- Elvira P. de Lara-Tuprio

- Maria Regina Justina E. Estuar

- Gerome M. Vedeja

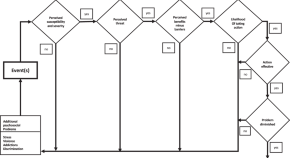

Perceptions of behaviour efficacy, not perceptions of threat, are drivers of COVID-19 protective behaviour in Germany

- Lilian Kojan

- Laura Burbach

- André Calero Valdez

Protecting communities during the COVID-19 global health crisis: health data research and the international use of contact tracing technologies

- Toija Cinque

Exploring the determinants of global vaccination campaigns to combat COVID-19

Evaluation of science advice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden

- Nele Brusselaers

- David Steadson

- Gunnar Steineck

Exploring the experiences, psychological well-being and needs of frontline healthcare workers of government hospitals in India: a qualitative study

- John Romate

- Eslavath Rajkumar

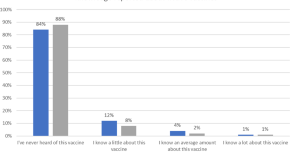

What causes COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy? Ignorance and the lack of bliss in the United Kingdom

- Josh Bullock

- Justin E. Lane

- F. LeRon Shults

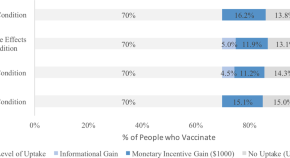

Vaccine hesitancy and monetary incentives

- Ganesh Iyer

- Vivek Nandur

- David Soberman

How South Korean Internet users experienced the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: discourse on Instagram

- Seoyoung Kim

- Hyun-Woo Lim

- Shin-Young Chung

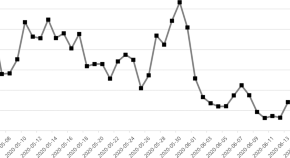

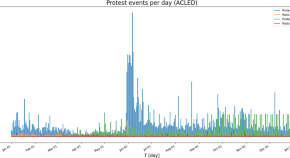

Emergence of protests during the COVID-19 pandemic: quantitative models to explore the contributions of societal conditions

- Koen van der Zwet

- Ana I. Barros

- Peter M. A. Sloot

Examining the role of the occupational safety and health professional in supporting the control of the risks of multiple psychosocial stressors generated during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Andrew Sharman

- David Thomas

Effect of COVID-19 on agricultural production and food security: A scientometric analysis

- Collins C. Okolie

- Abiodun A. Ogundeji

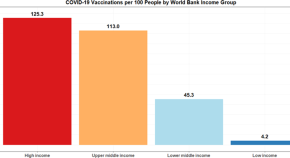

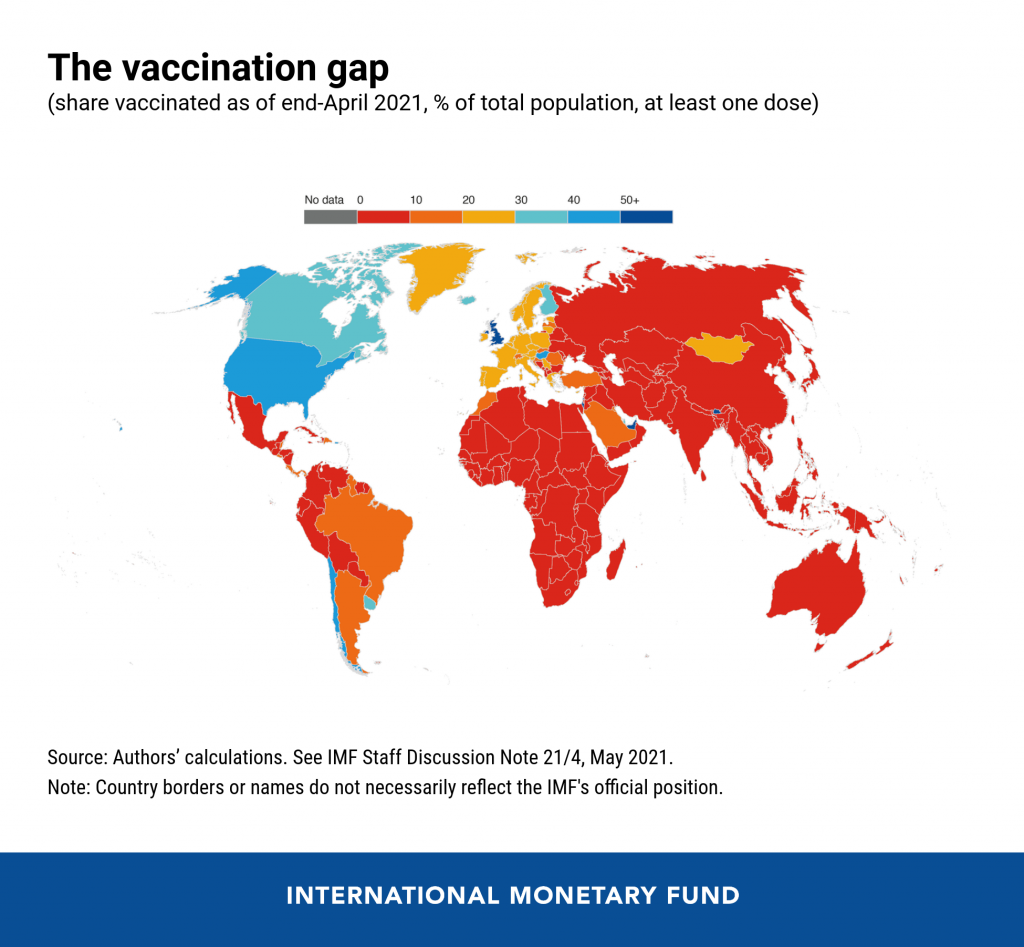

The radically unequal distribution of Covid-19 vaccinations: a predictable yet avoidable symptom of the fundamental causes of inequality

The Covid-19 pandemic—and its social and economic fallout—has thrust social and health-related inequalities into the spotlight. The pandemic, and our response to it, has induced new inequalities both within and between nations. However, now that highly efficacious vaccines are available, one might reasonably presume that we have in our hands the tools to address pandemic-associated inequalities. Nevertheless, two prominent social science theories, fundamental cause theory and diffusion of innovation theory suggest otherwise. Together, these theories predict that better resourced individuals and countries will jockey to harness the greatest vaccine benefit for themselves, leaving large populations of disadvantaged people unprotected. While many other life-saving prevention measures have been distributed unequally in ways these theories would predict, the COVID-19 vaccines represent a different kind of case. As the disease is so highly infectious and because mutations lead to new variants so rapidly, any inequality-generating process that leaves disadvantaged individuals and countries behind acts to put everyone—rich and poor—at risk. It is time that we ensure the equitable distribution of this life-saving benefit. As the fundamental cause and diffusion of innovation theories help illuminate processes that regularly produce inequities, we turn to them to reason about the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines. Specifically, employ them to suggest countermoves that may be necessary to avoid an irrational and inequitable vaccine rollout that ends up unfavorably affecting all people.

- Håvard Thorsen Rydland

- Joseph Friedman

- Terje Andreas Eikemo

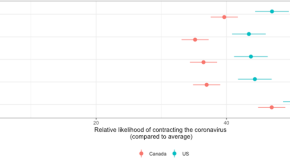

People underestimate the probability of contracting the coronavirus from friends

- Tobias Schlager

- Ashley V. Whillans

Mobilization of expert knowledge and advice for the management of the Covid-19 emergency in Italy in 2020

- Silvia Camporesi

- Federica Angeli

- Giorgia Dal Fabbro

Reading skills intervention during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Ana Filipa Silva

- Cátia Marques

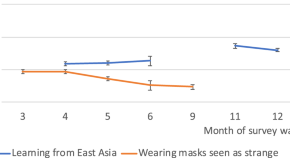

Keep that mask on: will Germans become more like East Asians?

- Xenia Matschke

- Marc Oliver Rieger

The CoRisk -Index: a data-mining approach to identify industry-specific risk perceptions related to Covid-19

- Fabian Stephany

- Leonie Neuhäuser

- Fabian Braesemann

Scientific illustrations of SARS-CoV-2 in the media: An imagedemic on screens

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused an overload of scientific information in the media, sometimes including misinformation or the dissemination of false content. This so-called infodemic , at a low intensity level, is also manifested in the spread of scientific and medical illustrations of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Since the beginning of the pandemic, images of other long-known viruses, sometimes imaginary reconstructions, or viruses that cause diseases in other, non-human species have been attributed to SARS-CoV-2. In a certain way, one can thus speak of a case of an imagedemic based on an alteration of the rigour and truth of informative illustrations in the media. Images that illustrate informative data have an influence on the emotional perception of viewers and the formation of attitudes and behaviours in the face of the current or future pandemics. So, image disinformation should be avoided, making it desirable that journalists confirm the validity of scientific images with the same rigour that they apply to any other type of image, instead of working with fake, made-up images from photo stock services. At a time when scientific illustration has great didactic power, high-quality information must be illustrated using images that are as accurate and real as possible, as for any other news topic. It is fundamental that informative illustrations about COVID-19 used in the media are scientifically rigorous.

- Celia Andreu-Sánchez

- Miguel Ángel Martín-Pascual

Covid-19 vaccines production and societal immunization under the serendipity-mindsponge-3D knowledge management theory and conceptual framework

- Quan-Hoang Vuong

- Minh-Hoang Nguyen

Choosing the right COVID-19 indicator: crude mortality, case fatality, and infection fatality rates influence policy preferences, behaviour, and understanding

- Chiara Natalie Focacci

- Pak Hung Lam

Assessment practices in Saudi higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Samar Yakoob Almossa

- Sahar Matar Alzahrani

Opposition in Japan to the Olympics during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Takumi Kato

Newspapers’ coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Eswatini: from distanciated re/presentations to socio-health panics

- Henri-Count Evans

Government disclosure in influencing people’s behaviors during a public health emergency

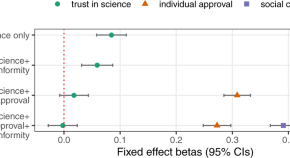

Facing the pandemic with trust in science

- Justin Sulik

- Ophelia Deroy

- Bahar Tunçgenç

Losses, hopes, and expectations for sustainable futures after COVID

- Stephan Lewandowsky

- Ullrich K. H. Ecker

Core belief disruption amid the COVID-19 pandemic in Japanese adults

- Izumi Matsudaira

- Yuji Takano

- Yasuyuki Taki

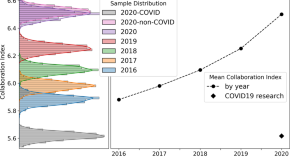

Collaboration in the time of COVID: a scientometric analysis of multidisciplinary SARS-CoV-2 research

- Eoghan Cunningham

- Barry Smyth

- Derek Greene

The impact of COVID-19 on digital data practices in museums and art galleries in the UK and the US

- Lukas Noehrer

- Abigail Gilmore

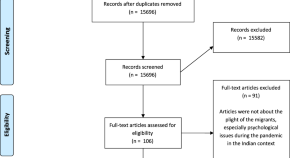

The plight of migrants during COVID-19 and the impact of circular migration in India: a systematic review

- Joshy Jesline

- Allen Joshua George

Perceptions of risk for COVID-19 among individuals with chronic diseases and stakeholders in Central Appalachia

- Manik Ahuja

- Hadii M. Mamudu

- Timir K. Paul

News media coverage of COVID-19 public health and policy information

- Katharine J. Mach

- Raúl Salas Reyes

- Nicole Klenk

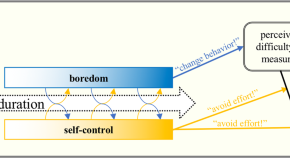

Bored by bothering? A cost-value approach to pandemic boredom

- Corinna S. Martarelli

- Wanja Wolff

- Maik Bieleke

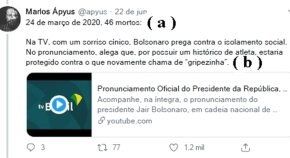

Transmediatisation of the Covid-19 crisis in Brazil: The emergence of (bio-/geo-)political repertoires of (re-)interpretation

- Jaime de Souza Júnior

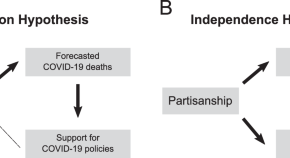

The interplay between partisanship, forecasted COVID-19 deaths, and support for preventive policies

- Lucia Freira

- Marco Sartorio

- Joaquin Navajas

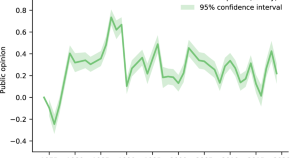

Large-scale quantitative evidence of media impact on public opinion toward China

- Junming Huang

- Gavin G. Cook

Viral tunes: changes in musical behaviours and interest in coronamusic predict socio-emotional coping during COVID-19 lockdown

- Lauren K. Fink

- Lindsay A. Warrenburg

- Melanie Wald-Fuhrmann

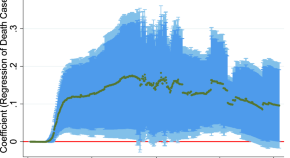

How epidemic psychology works on Twitter: evolution of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.

- Luca Maria Aiello

- Daniele Quercia

- Sagar Joglekar

Effectiveness of the flipped classroom model on students’ self-reported motivation and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- José María Campillo-Ferrer

- Pedro Miralles-Martínez

Predicting effectiveness of countermeasures during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Africa using agent-based simulation

- Moritz Kersting

- Andreas Bossert

- Jan Chr. Schlüter

Institutional and cultural determinants of speed of government responses during COVID-19 pandemic

- Diqiang Chen

- Diefeng Peng

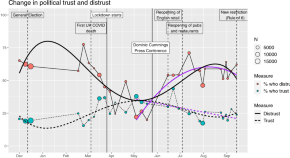

Changes in political trust in Britain during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: integrated public opinion evidence and implications

- Fanny Lalot

- Dominic Abrams

The COVID-19 wicked problem in public health ethics: conflicting evidence, or incommensurable values?

Pandemics and protectionism: evidence from the “Spanish” flu

- Nina Boberg-Fazlic

- Markus Lampe

COVID-19 and the academy: opinions and experiences of university-based scientists in the U.S.

- Timothy P. Johnson

- Mary K. Feeney

- Eric W. Welch

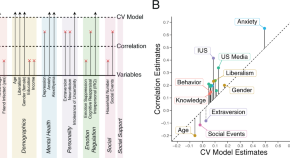

Anxiety, gender, and social media consumption predict COVID-19 emotional distress

- Joseph Heffner

- Marc-Lluís Vives

- Oriel FeldmanHall

Rise and fall of the global conversation and shifting sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Xiangliang Zhang

Not-so-straightforward links between believing in COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and engaging in disease-preventive behaviours

- Hoi-Wing Chan

- Connie Pui-Yee Chiu

- Ying-yi Hong

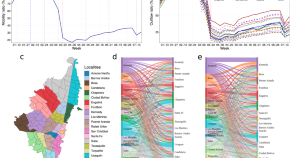

Changes in mobility and socioeconomic conditions during the COVID-19 outbreak

- Marco Dueñas

- Mercedes Campi

- Luis E. Olmos

Hollywood survival strategies in the post-COVID 19 era

- Michael Johnson Jr

More than just a mental stressor: psychological value of social distancing in COVID-19 mitigation through increased risk perception—a preliminary study in China

- Yuanchao Gong

- Linxiu Zhang

Prediction of COVID-19 Social Distancing Adherence (SoDA) on the United States county-level

- Myles Ingram

- Ashley Zahabian

How shades of truth and age affect responses to COVID-19 (Mis)information: randomized survey experiment among WhatsApp users in UK and Brazil

- Santosh Vijaykumar

- Daniel Morris

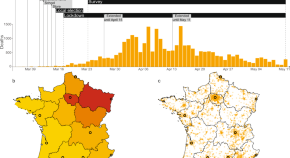

What can we learn from Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on human behaviour? The case of France’s lockdown

- Cyril Atkinson-Clement

- Eléonore Pigalle

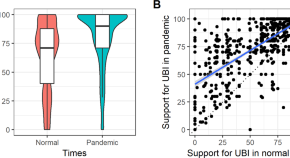

Why has the COVID-19 pandemic increased support for Universal Basic Income?

- Daniel Nettle

- Elliott Johnson

- Rebecca Saxe

A critical juncture in universal healthcare: insights from South Korea’s COVID-19 experience for the United Kingdom to consider

- Kyungmoo Heo

- Keonyeong Jeong

- Yongseok Seo

The history teacher education process in Portugal: a mixed method study about professionalism development

- Glória Solé

- Marília Gago

Understanding the buffering effect of social media use on anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Yousri Marzouki

- Fatimah Salem Aldossari

- Giuseppe A. Veltri

People’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic during its early stages and factors affecting those responses

- Junyi Zhang

Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19

- Bernadette Hyland-Wood

- John Gardner

The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need for an equity-focused global health agenda

- A. H. Kelly

- M. Avendano

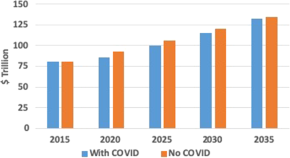

The COVID-19 effect on the Paris agreement

- John M. Reilly

- Y.-H. Henry Chen

- Henry D. Jacoby

Responding to the pandemic as a family unit: social impacts of COVID-19 on rural migrants in China and their coping strategies

- Shuangshuang Tang

Science communication as a preventative tool in the COVID19 pandemic

- Gagan Matta

Human–dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: booming dog adoption during social isolation

- Liat Morgan

- Alexandra Protopopova

COVID-19 impact and survival strategy in business tourism market: the example of the UAE MICE industry

- Asad A. Aburumman

Satisfaction of scientists during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Isabel J. Raabe

- Alexander Ehlert

- Heiko Rauhut

Trouble in the trough: how uncertainties were downplayed in the UK’s science advice on Covid-19

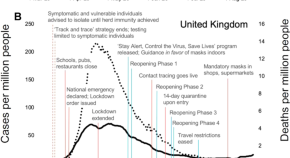

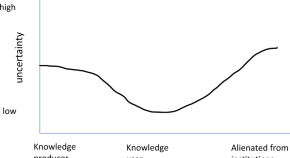

The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic has forced science advisory institutions and processes into an unusually prominent role, and placed their decisions under intense public, political and media scrutiny. In the UK, much of the focus has been on whether the government was too late in implementing its lockdown policy, resulting in thousands of unnecessary deaths. Some experts have argued that this was the result of poor data being fed into epidemiological models in the early days of the pandemic, resulting in inaccurate estimates of the virus’s doubling rate. In this article, I argue that a fuller explanation is provided by an analysis of how the multiple uncertainties arising from poor quality data, a predictable characteristic of an emergency situation, were represented in the advice to decision makers. Epidemiological modelling showed a wide range of credible doubling rates, while the science advice based upon modelling presented a much narrower range of doubling rates. I explain this puzzle by showing how some science advisors were both knowledge producers (through epidemiological models) and knowledge users (through the development of advice), roles associated with different perceptions of scientific uncertainty. This conflation of experts’ roles gave rise to contradictions in the representation of uncertainty over the doubling rate. Role conflation presents a challenge to science advice, and highlights the need for a diversity of expertise, a structured process for selecting experts, and greater clarity regarding the methods by which expert consensus is achieved. The analysis indicates an urgent research agenda that can help strengthen the UK science advice system after Covid-19.

- Warren Pearce

Social markers of a pandemic: modeling the association between cultural norms and COVID-19 spread data

- Máté Kapitány-Fövény

- Mihály Sulyok

Validity and usefulness of COVID-19 models

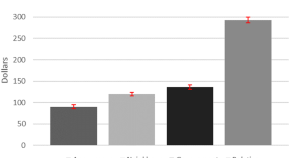

Assessment of monthly economic losses in Wuhan under the lockdown against COVID-19

- Shibing You

- Hengli Wang

- Yongzeng Lai

Too bored to bother? Boredom as a potential threat to the efficacy of pandemic containment measures

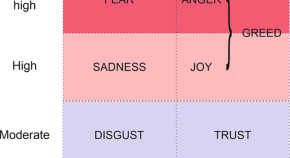

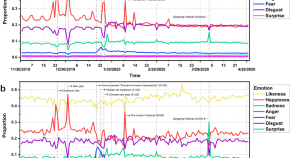

Sentiments and emotions evoked by news headlines of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak

- Faheem Aslam

- Tahir Mumtaz Awan

- Mahwish Parveen

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Learning from a Pandemic. The Impact of COVID-19 on Education Around the World

- Open Access

- First Online: 15 September 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Fernando M. Reimers 2

28 Citations

11 Altmetric

This introductory chapter sets the stage for the book, explaining the goals, methods, and significance of the comparative study. The chapter situates the theoretical significance of the study with respect to research on education and inequality, and argues that the rare, rapid, and massive change in the social context of schools caused by the pandemic provides a singular opportunity to study the relative autonomy of educational institutions from larger social structures implicated in the reproduction of inequality. The chapter provides a conceptual educational model to examine the impact of COVID-19 on educational opportunity. The chapter describes the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and how it resulted into school closures and in the rapid deployment of strategies of remote education. It examines available evidence on the duration of school closures, the implementation of remote education strategies, and known results in student access, engagement, learning, and well-being.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The COVID-19 Teaching Experience: The University of Petra as a Case Study

Post-Pandemic Crisis in Chilean Education. The Challenge of Re-institutionalizing School Education

COVID-19 causes unprecedented educational disruption: Is there a road towards a new normal?

1.1 introduction.

The COVID-19 pandemic shocked education systems in most countries around the world, constraining educational opportunities for many students at all levels and in most countries, especially for poor students, those otherwise marginalized, and for students with disabilities. This impact resulted from the direct health toll of the pandemic and from indirect ripple effects such as diminished family income, food insecurity, increased domestic violence, and other community and societal effects. The disruptions caused by the pandemic affected more than 1.7 billion learners, including 99% of students in low and lower-middle income countries (OECD, 2020c; United Nations, 2020 , p. 2).

While just around 2% of the world population (168 million people as of May 27, 2021) had been infected a year after the coronavirus was first detected in Wuhan, China, and only 2% of those infected (3.5 million) had lost their lives to the virus (World Health Organization, 2021a ), considerably more people were impacted by the policy responses put in place to contain the spread of the virus. Beyond the infections and fatalities reported as directly caused by COVID-19, analysis of the excess mortality since the pandemic outbreak, suggests that an additional 3 million people may have lost their lives to date because of the virus (WHO, 2021b ).

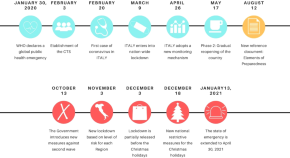

As the General Director of the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020 (WHO, 2020a ), countries began to adopt a range of policy responses to contain the spread of the virus. The adoption of containment practices accelerated as the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020b ).

Chief among those policy responses were the social distancing measures which reduced the ability of many people to work, closed businesses, and reduced the ability to congregate and meet for a variety of purposes, including teaching and learning. The interruption of in-person instruction in schools and universities limited opportunities for students to learn, causing disengagement from schools and, in some cases, school dropouts. While most schools put in place alternative ways to continue schooling during the period when in-person instruction was not feasible, those arrangements varied in their effectiveness, and reached students in different social circumstances with varied degrees of success.

In addition to the learning loss and disengagement with learning caused by the interruption of in-person instruction and by the variable efficacy of alternative forms of education, other direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic diminished the ability of families to support children and youth in their education. For students, as well as for teachers and school staff, these included the economic shocks experienced by families, in some cases leading to food insecurity, and in many more causing stress and anxiety and impacting mental health. Opportunity to learn was also diminished by the shocks and trauma experienced by those with a close relative infected by the virus, and by the constraints on learning resulting from students having to learn at home, and from teachers having to teach from home, where the demands of schoolwork had to be negotiated with other family necessities, often sharing limited space and, for those fortunate to have it, access to connectivity and digital devices. Furthermore, the prolonged stress caused by the uncertainty over the evolution and conclusion of the pandemic and resulting from the knowledge that anyone could be infected and potentially lose their lives, created a traumatic context for many that undermined the necessary focus and dedication to schoolwork. These individual effects were reinforced by community effects, particularly for students and teachers living in communities where the multifaceted negative impacts resulting from the pandemic were pervasive.

Beyond these individual and community effects of the pandemic on students, and on teachers and school staff, the pandemic also impacted education systems and schools. Burdened with multiple new demands for which they were unprepared, and in many cases inadequately resourced, the capacity of education leaders and administrators, who were also experiencing the previously described stressors faced by students and teachers, was stretched considerably. Inevitably, the institutional bandwidth to attend to the routine operations and support of schools was diminished and, as a result, the ability to manage and sustain education programs was hampered. Routine administrative efforts to support school operations as well as initiatives to improve them were affected, often setting these efforts back.

Published efforts to take stock of the educational impact of the pandemic to date, as it continues to unfold, have largely consisted of collecting and analyzing a limited number of indicators such as enrollment, school closures, or reports from various groups about the alternative arrangements put in place to sustain educational opportunity, including whether, when, and how schools were open for in-person instruction and what alternative arrangements were made to sustain education remotely. Often these data have been collected in samples of convenience, non-representative, further limiting the ability to obtain true estimates of the education impact of the pandemic on the student population. A recent review of research on learning loss during the pandemic identified only eight studies, all focusing on OECD countries which experienced relatively short periods of school closures (Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, the United States, Australia, and Germany). These studies confirm learning loss in most cases and, in some, increases in educational inequality, but they also document heterogeneous effects of closures on learning for various school subjects and education levels (Donelly & Patrinos, 2021 ).

There have also been predictions of the likely impact of the pandemic, consisting mostly of forecasts and simulations based on extrapolations of what is known about the interruption of instruction in other contexts and periods. For example, based on an analysis of the educational impact of the Ebola outbreaks, Hallgarten identified the following likely drivers of school dropouts during COVID-19: (1) the reduction in the availability of education services, (2) the reduction in access to education services, (3) the reduction in the utilization of schools, and (4) lack of quality education. Undergirding these drivers of dropout are these factors: (a) school closures, (b) lack of at-home educational materials, (c) fear of school return and emotional stress caused by the pandemic, (d) new financial hardships leading to difficulties paying fees, or to children taking up employment, (e) lack of reliable information on the evolution of the pandemic and on school reopenings, and (f) lack of teacher training during crisis. (Hallgarten, 2020 , p. 3).

Another type of estimate of the likely educational cost of the pandemic includes forecasts of the future economic costs for individuals and for society. A simulation of the impact of a full year of learning loss estimated it as a 7.7% decline in discounted GDP (Hanushek & Woessman, 2020 ). The World Bank estimated the cost of the education disruption as a $10 trillion dollars in lost earnings over time for the current generation of students (World Bank, 2020 ).

Many of the reports to date of the educational responses to the pandemic and their results are in fact reports of intended policy responses, often reflecting the views of the highest education authorities in a country, a view somewhat removed from the day-to-day realities of teachers and students and that provides information about policy intent rather than on the implementation and actual effect of those policies. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank conducted a survey of the strategies for education continuity adopted by 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean during the first phase of the crisis, concluding that most had relied on the provision of digital content on web-based portals, along with the use of TV, radio, and printed materials, and that very few had integrated learning management systems, and only one country had kept schools open (Alvarez et al., 2020 ).

These reports, valuable as they are, are limited in what they contribute to understanding the ways in which education systems, teachers, and students were impacted by the pandemic and about how they responded, chiefly because it is challenging to document the impact of an unexpected education emergency in real time, and because it will take time to be able to ascertain the full short- and medium-term impact of this global education shock.

1.2 Goals and Significance of this Study

This book is a comparative effort to discern the short-term educational impact of the pandemic in a selected number of countries, reflecting varied levels of financial and institutional education resources, a variety of governance structures, varied levels of education performance, varied regions of the world, and countries of diverse levels of economic development, income per capita, and social and economic inequality. Our goal is to contribute an evidence-based understanding of the short-term educational impact of the pandemic on students, teachers, and systems in those countries, and to discuss the likely immediate effects of such an impact. Drawing on thirteen national case studies, a chapter presenting a comparative perspective in five OECD countries and another offering a global comparative perspective, we examine how the pandemic impacted education systems and educational opportunity for students. Such systematic stock-taking of how the pandemic impacted education is important for several reasons. The first is that an understanding of the full global educational impact of the pandemic necessitates an understanding of the ways in which varied education systems responded (such as the nature and duration of school closures, alternative means of education delivery deployed, and the goals of those strategies of education continuity during the pandemic) and of the short-term results of those responses (in terms of school attendance, engagement, learning and well-being for different groups of students). In order to understand the possible student losses in knowledge and skills, or in educational attainment that the current cohort of students will experience relative to previous or future cohorts, and to understand the consequences of such losses, we must first understand the processes through which the pandemic influenced their opportunities to learn. Such systematization and stock-taking are also essential to plan for remediation and recovery, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic and beyond. While the selection of countries was not intended to represent the entire world, the knowledge gained from the analysis of the educational impact of the pandemic on these diverse cases, as well as making visible what is not yet known, will likely have heuristic value to educators designing mitigation and remediation strategies in a wide variety of settings and may provide a useful framework to design further research on this topic.

In addition, the pandemic is likely to exacerbate preexisting challenges and to create new ones, increasing unemployment for instance or contributing to social fragmentation, which require education responses. Furthermore, there were numerous education challenges predating the pandemic that need attention. Addressing these new education imperatives, as well as tackling preexisting ones, requires ‘building back better’; not just restoring education systems to their pre-pandemic levels of functioning, but rather realigning them to these new challenges. Examining the short-term education response to the pandemic provides insight into whether the directionality of such change is aligned to ‘building back better’ and with the kind of priorities that should guide those efforts during the remainder of the pandemic and in the pandemic aftermath.

Lastly, the pandemic provides a rare opportunity to help us understand how education institutions relate to other institutions and to their external environment under conditions of rapid change. Much of what we know about the relationship of schools to their external environment is based on research carried out in much more stable contexts, where it is difficult to discern what is a cause and what is an effect. For instance, there is robust evidence that schools often reflect and contribute to reproducing social stratification, providing children from different social origins differential opportunities to learn, and resulting in children of poor parents receiving less and lower quality schooling than children of more affluent parents. It is also the case that educational attainment is a robust predictor of income. Increases in income inequality correlate with increases in education inequality, although government education policies have been shown to mitigate such a relationship (Mayer, 2010 ).

The idea that education policy can mitigate the structural relationship between education and income inequality suggests that the education system has certain autonomy from the larger social structure. But disentangling to what extent school policy and schools can just reproduce social structures or whether they can transform social relations is difficult because changes in education inequality and social inequality happen concurrently and slowly, which makes it difficult to establish what is cause and what is effect. However, a pandemic is a rare rapid shock to that external environment, the equivalent of a solar eclipse, and thus a singular opportunity to observe how schools and education systems respond when their external environment changes, quite literally, overnight. Such a shock will predictably have disproportionate impacts on the poor, via income and health effects, presenting a unique opportunity to examine whether education policies are enacted to mitigate the resulting disproportionate losses on educational opportunity from such income and health shocks for the poor and to what extent they are effective.

1.3 A Stylized Global Summary of the Facts

A full understanding of the educational impact of the pandemic on systems, educators, and students will require an analysis of such impact in three time frames: the immediate impact, taking place while the pandemic is ongoing; the immediate aftermath, as the epidemic comes under control, largely as a result of the population having achieved herd immunity after the majority has been inoculated; and the medium term aftermath, once education systems, societies, and economies return to some stability. Countries will differ in the timeline at which they transition through these three stages, as a function of the progression of the pandemic and success controlling it, as a result of public health measures and availability, distribution, and uptake of vaccines, and as a result of the possible emergence of new more virulent strands of the virus which could slow down the efforts to contain the spread. There are challenges involved in scaling up the production and distribution of vaccines, which result in considerable inequalities in vaccination rates among countries of different income levels. It is estimated that 11 billion doses of vaccines are required to achieve global herd immunity (over 70% of the population vaccinated). By May 24, 2021, a total of 1,545,967,545 vaccine doses had been administered (WHO, 2021a ), but 75% of those vaccines have been distributed in only 10 high income countries (WHO, 2021c ).

Of the 9.5 billion doses expected to be available by the end of 2021, 6 billion doses have already been purchased by high and upper middle-income countries, whereas low- and lower-income countries—where 80% of the world population lives—have only secured 2.6 billion, including the pledges to COVAX, an international development initiative to vaccinate 20% of the world population (Irwin, 2021 ). At this rate, it is estimated that it will take at least until the end of 2022 to vaccinate the lowest income population in the world (Irwin, 2021 ).

The educational impact of the pandemic in each of these timeframes will likely differ, as will the challenges that educators and administrators face in each case, with the result that the necessary policy responses will be different in each case. The immediate horizon—what could be described as the period of emergency—can in turn be further analyzed in various stages since, given the relatively long duration of the pandemic, spanning over a year, schools and systems were able to evolve their responses in tandem with the evolution of the epidemic and continued to educate to varying degrees as a result of various educational strategies of education continuity adopted during the pandemic. During the initial phase of this immediate impact, the responses were reactive, with very limited information on their success, and with considerable constraints in resources available to respond effectively. This initial phase of the emergency was then followed by more deliberate efforts to continue to educate, in some cases reopening schools—completely or in part—and by more coordinated and comprehensive actions to provide learning opportunities remotely. The majority of the analysis presented in this book focuses on this immediate horizon, spanning the twelve months between January of 2020, when the pandemic was beginning to extend beyond China, as the global outbreak was recognized on March 11, through December of 2020.

The pandemic’s impact in the immediate aftermath and beyond will not be a focus of this book, largely because most countries in the world have not yet reached a post-pandemic stage, although the concluding chapter draws out implications from the short-term impact and responses for that aftermath.

Education policy responses need to differentially address each of these three timeframes: short-term mitigation of the impact during the emergency; immediate remediation and recovery in the immediate aftermath; and medium-term recovery and improvement after the initial aftermath of the pandemic.

As the epidemic spread from Wuhan, China—where it first broke out in December of 2019—throughout the world, local and national governments suspended the operation of schools as a way to contain the rapid spread of the virus. Limiting gatherings in schools, where close proximity would rapidly spread respiratory infections, had been done in previous pandemics as a way to prevent excess demand for critical emergency services in hospitals. Some evidence studying past epidemics suggested in fact that closing schools contributed to slow down the spread of infections. A study of non-pharmaceutical interventions adopted during the 1918–19 pandemic in the United States shows that mortality was lower in cities that closed down schools and banned public gatherings (Markel et al., 2007 ). A review of 79 epidemiological studies, examining the effect of school closures on the spread of influenza and pandemics, found that school closures contributed to contain the spread (Jackson et al., 2013 ).

In January 26, China was the first country to implement a national lockdown of schools and universities, extending the Spring Festival. As UNESCO released the first global report on the educational impact of the pandemic on March 3, 2020, twenty-two countries had closed schools and universities as part of the measures to contain the spread of the virus, impacting 290 million students (UNESCO, 2020 ). Following the World Health Organization announcement, on March 11, 2020, that COVID-19 was a global pandemic, the number of countries closing schools increased rapidly. In the following days 79 countries had closed down schools (UNESCO, 2020 ).

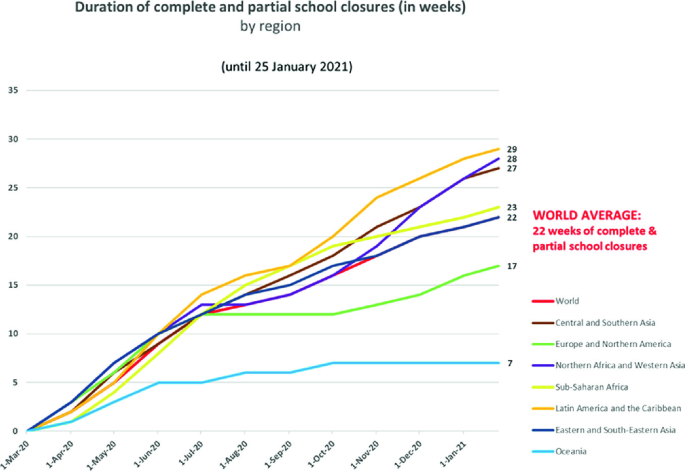

Following the initial complete closure of schools in most countries around the world there was a partial reopening of schools, in some cases combined with localized closings. By the end of January 2021, UNESCO estimated that globally, schools had completely closed an average of 14 weeks, with the duration of school closures extending to 22 weeks if localized closings were included (UNESCO, 2021 ). There is great variation across regions in the duration of school closures, ranging from 20 weeks of complete national closings in Latin America and the Caribbean to just one month in Oceania, and 10 weeks in Europe. There is similar variation with respect to localized closures, from 29 weeks in Latin America and the Caribbean to 7 weeks in Oceania, as seen in Fig. 1.1 . By January 2021, schools were fully open in 101 countries.

Source UNESCO ( 2021 )

Duration of complete and partial school closures by region by January 25, 2021.

As it became clear that it would take considerable time until a vaccine to prevent infections would become available, governments began to consider options to continue to educate in the interim. These options ranged from total or partial reopening of schools to creating alternative means of delivery, via online instruction, distributing learning packages, deploying radio and television, and using mobile phones for one- or two-way communication with students. In most cases, deploying these alternative means of education was a process of learning by doing, sometimes improvisation, with a rapid exchange of ideas across contexts about what was working well and about much that was not working as intended. As previous experience implementing these measures in a similar context of school lockdown was limited, there was not much systematized knowledge about what ‘worked’ to transfer any approach with some confidence of what results it would produce in the context created by the pandemic. As these alternatives were put in place, educators and governments learned more about what needs they addressed, and about which ones they did not.

For instance, it soon became apparent that the creation of alternative ways to deliver instruction was only a part of the challenge. Since in many jurisdictions schools deliver a range of services—from food to counseling services—in addition to instruction, it became necessary to find alternative ways to deliver those services as well, not just to meet recognized needs prior to the pandemic but because the emergency was increasing poverty, food insecurity, and mental health challenges, making such support services even more essential.

As governments realized that the alternative arrangements to deliver education had diminished the capacity to achieve the instructional goals of a regular academic year, it became necessary to reprioritize the focus of instruction.

In a study conducted at the end of April and beginning of May 2020, based on a survey administered to a haphazard sample of teachers and education administrators in 59 countries, we found that while schools had been closed in all cases, plans for education continuity had been implemented in all countries we had surveyed. Those plans involved using existing online resources, online instruction delivered by students’ regular teachers, instructional packages with printed resources, and educational television programmes. The survey revealed severe disparities in access to connectivity, devices, and the skills to use them among children from different socio-economic backgrounds. On balance, however, the strategies for educational continuity were rated favourably by teachers and administrators, who believed they had provided effective opportunities for student learning. These strategies prioritized academic learning and provided support for teachers, whereas they gave less priority to the emotional and social development of students.

These strategies deployed varied mechanisms to support teachers, primarily by providing them access to resources, peer networks within the school and across schools, and timely guidance from leadership. A variety of resources were used to support teacher professional development, mostly relying on online learning platforms, tools that enabled teachers to communicate with other teachers, and virtual classrooms (Reimers & Schleicher, 2020 ).

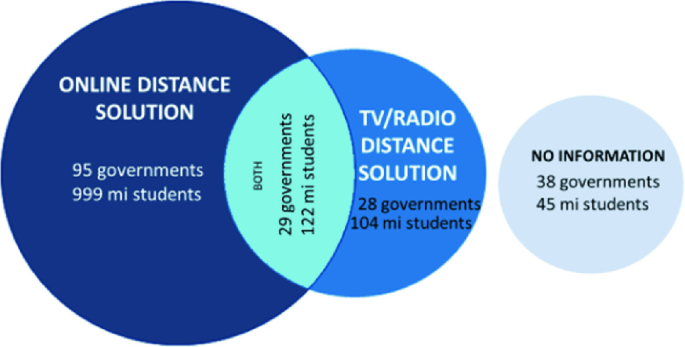

Some countries relied more heavily on some of these approaches, while others used a combination, as reported by UNESCO and seen in Fig. 1.2 .

Source Giannini ( 2020 )

Government-initiated distance learning solutions and intended reach.

Share of students with Internet at home in countries relying exclusively on online learning platforms.

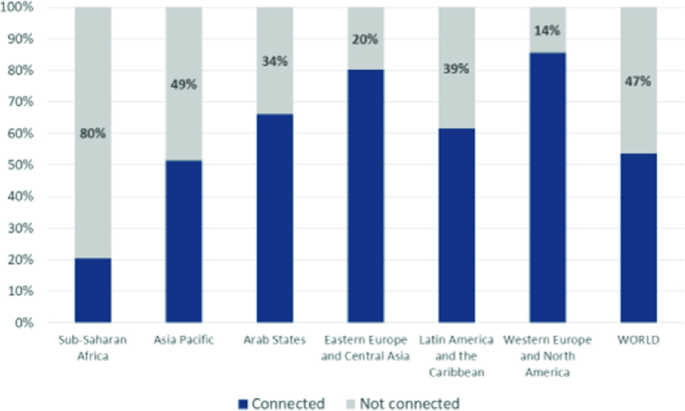

A significant number of children did not have access to the online solutions provided because of lack of connectivity, as shown in a May 2020 report by UNESCO. In Sub-Saharan Africa, a full 80% of children lacked internet at home; this figure was 49% in Asia Pacific; 34% in the Arab States and 39% in Latin America, but it was only 20% in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and 14% in Western Europe and North America (Giannini, 2020 ).

Similar results were obtained by a subsequent cross-national study administered to senior education planning officials in ministries of education, conducted by UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank. These organizations administered two surveys between May and June 2020, and between July and October 2020, to government officials in 118 and 149 countries, respectively. The study documented extended periods of school closures. The study further documented differences among countries in whether student learning was monitored, with much greater levels of monitoring in high income countries than in lower income countries.

The study also confirmed that most governments created alternative education delivery systems during the period when schools were closed, through a variety of modalities including online platforms, television, radio, and paper-based instructional packages. Governments also adopted targeted measures to support access to these platforms for disadvantaged students, provided devices or subsidized connectivity, and supported teachers and caregivers. The report shows disparities between countries at different income levels, with most high-income countries providing such support and a third of lower income countries not providing any specific support for connectivity to low-income families (UNESCO-UNICEF-the World Bank, 2020 ).

The UNESCO-UNICEF-World Bank surveys reveal considerable differences in the education responses by level of income of the country. For instance, whereas by the end of September of 2020 schools in high-income countries had been closed 27 days, on average, that figure increased to 40 days in middle-income countries, to 68 days in lower middle-income countries, and to 60 days in low-income countries (Ibid, 15).

For most countries there were no plans to systematically assess levels of students’ knowledge and skills as schools reopened, and national systematic assessments were suspended in most countries. There was considerable variation across countries, and within countries, in terms of when schools reopened and how they did so. Whereas some countries offered both in-person and remote learning options—and gave students a choice of which approach to use—others did not offer choices. There were also variations in the amount of in-person instruction students had access to once schools reopened. Some schools and countries introduced measures to remediate learning loss as schools reopened, but not all did.

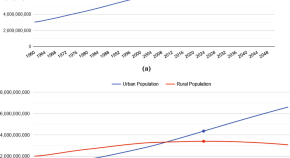

1.4 The Backdrop to the Pandemic: Enormous and Growing Inequality and Social Exclusion

The pandemic impacted education systems as they faced two serious interrelated preexisting challenges: educational inequality and insufficient relevance. A considerable growth in economic inequality, especially among individuals within the same nations, has resulted in challenges of social inclusion and legitimacy of the social contract, particularly in democratic societies. Over the last thirty years, income inequality has increased in countries such as China, India, and most developed countries. Over the last 25 years there are also considerable inequalities between nations, even though those have diminished over the last 25 years. The average income of a person in North America is 16 times greater than the income of the average person in Sub-Saharan Africa. 71% of the world’s population live in countries where inequality has grown (UN, 2021 ). The Great Recession of 2008–2009 worsened this inequality (Smeedling, 2012 ).

One of the correlates of income inequality is educational inequality. Studies show that educational expansion (increasing average years of schooling attainment and reducing inequality of schooling) relates to a reduction in income inequality (Coadi & Dizioly, 2017 ). But education systems, more often than not, reflect social inequalities, as they offer the children of the poor, often segregated in schools of low quality, deficient opportunities to learn skills that help them improve their circumstances, whereas they provide children from more affluent circumstances opportunities to gain knowledge and skills that give them access to participate economically and civically. In doing so, schools serve as a structural mechanism that reproduces inequality, and indeed legitimize it as they obscure the structural forces that sort individuals into lives of vastly different well-being with an ideology of meritocracy that in effect blames the poor for the circumstances that their lack of skills lead to, when they have not been given effective opportunities to develop such skills.

There is abundant evidence of the vastly different learning outcomes achieved by students from different social origins, and of the differences in the educational environments they have access to. In the most recent assessment of student knowledge and skills conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the socioeconomic status of students is significantly correlated to student achievement in literacy, math, and science in all 76 countries participating in the study (OECD, 2019 ). On average, among OECD countries, 12% of the variance in reading performance is explained by the socioeconomic background of the student. The strength of this relationship varies across countries, in some of them it is lower than the average as is the case in Macao (1.7%), Azerbaijan (4.3%), Kazakhstan (4.3%), Kosovo (4.9%), Hong Kong (5.1%), or Montenegro (5.8%). In other countries, the strength of the relationship between socioeconomic background and reading performance is much greater than the average such as in Belarus (19.8%), Romania (18.1%), Philippines (18%), or Luxembourg (17.8%). A significant reading gap exists between the students in the bottom 25% and those in the top 25% of the socioeconomic distribution, averaging 89 points, which is a fifth of the average reading score of 487, and almost a full standard deviation of the global distribution of reading scores in PISA. In spite of these strong associations between social background and reading achievement, there are students who defy the odds; the percentage of students whose social background is at the bottom 25%—the poorest students—whose reading performance is in the top 25%—academically resilient students—averages 11% across all OECD countries. This percentage is much greater in the countries where the relationship between social background and achievement is lower. In Macao, for instance, 20% of the students in the top 25% of achievement are among the poorest 25%. In contrast, in countries with a strong relationship between socioeconomic background and reading achievement, the percentage of academically resilient students among the poor is much lower, in Belarus and Romania it is 9%. These differences in reading skills by socioeconomic background are even more pronounced when looking at the highest levels of reading proficiency, those at which students can understand long texts that involve abstract and counterintuitive concepts as well as distinguish between facts and opinions based on implicit clues about the source of the information. Only 2.9% of the poorest students, compared with 17.4% among the wealthier quarter, can read at those levels of proficiency on average for the OECD (OECD, 2019b , p. 58). Table 1.1 summarizes socioeconomic disparities in reading achievement. The relationship of socioeconomic background to students’ knowledge and skills is stronger for math and science. On average, across the OECD, 13.8% of math skills and 12.8% of science skills are predicted by socioeconomic background.

The large number of children who fail to gain knowledge and skills in schools has been characterized, by World Bank staff and others, as ‘a global learning crisis’ or ‘learning poverty’, though the evidence on the strong correlation of learning poverty to family poverty suggests that this should more aptly be characterized as ‘the learning crisis for the children of the poor’ (World Bank, 2018 ). These low levels of learning have direct implications for the ability of students to navigate the alternative education arrangements put in place to educate during the pandemic; clearly students who can read at high levels are more able to study independently through texts and other resources than struggling readers.

The second interrelated challenge is that of ensuring that what ALL children learn in school is relevant to the challenges of the present and, most importantly, of the future. While the challenge of the relevance of learning is not new in education, the rapid developments in societies, resulting from technologies and politics, create a new urgency to address it. For students with the capacity to set personal learning goals, or with more self-management skills, or with greater skills in the use of technology, or with greater flexibility and resiliency, or with prior experience with distance learning, it was easier to continue to learn through the remote arrangements established to educate during the pandemic than it was for students with less developed skills in those domains. While the emphasis on the development of such breadth of skills, also called twenty-first century skills, has been growing around the world, as reflected in a number of recent curriculum reforms, there are large gaps between the ambitious aspirations reflected in modern curricula and standards, and the implementation of those reforms and instructional practice (Reimers, 2020b ; Reimers, 2021 ).

The challenges of low efficacy and relevance have received attention from governments and from international development agencies, including the United Nations and the OECD. The UN Sustainable Development Goals, for instance, propose a vision for education that aligns with achieving an inclusive and sustainable vision for the planet, even though, by most accounts, the resources deployed to finance the achievement of the education goal fall short with respect to those ambitions. In 2019 UNESCO’s director general tasked an international commission with the preparation of a report on the Futures of Education, focusing in particular on the question of how to align education institutions with the challenges facing humanity and the planet.

1.5 The Pandemic and Health

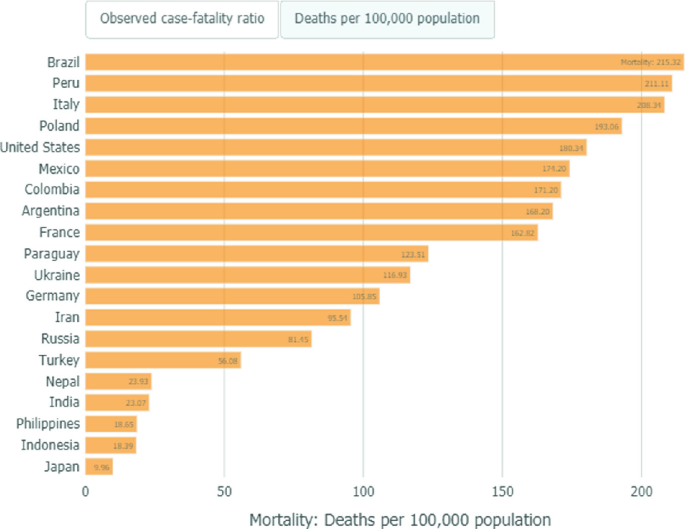

The main direct effect of the Coronavirus disease is in infecting people, compromising their health and in some cases causing their death. By May 27 of 2021, 168,040,871 people worldwide had become infected, of whom 3,494,758 had died reportedly from COVID-19 (World Health Organization, 2021a ) and an additional 3 million had likely died from COVID-19 as they were excess deaths relative to the total number of deaths the previous year (World Health Organization, 2021b ). As expected, more people are infected in countries with larger populations, but the rate of infection by total population and the rate of deaths by total population suggest variations in the efficacy of health policies used to contain the spread as shown in Fig. 1.4 , which includes the top 20 countries with the highest relative number of COVID-19 fatalities. These differences reflect differences in the efficacy of health policies to contain the pandemic, as well as differences in the response of the population to guidance from public health authorities. Countries in which political leaders did not follow science-based advice to contain the spread, and in which a considerable share of the population did not behave in ways that contributed to mitigate the spread of the virus, not wearing face masks or socially distancing for instance, such as in Brazil and the United States, fared much poorer than those who did implement effective public health containment measures such as China, South Korea, or Singapore, with such low numbers of deaths per 100,000 people that they are not even on this chart of the top 20.

Source Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center ( 2021 )

Number of reported COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 population in the 20 countries with the highest rates as of May 27, 2021.

1.6 The Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality

The social distancing measures limited the ability of business to operate, reducing household income and demand. This produced an economic recession in many countries. For example, in the United States, 43% of small businesses closed temporarily (Bartik et al., 2020).

A household survey in seventeen countries in Latin America and the Caribbean demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic differentially impacted households at different income levels. The study shows significant and unequal job losses with stronger effects among the lowest income households. The study revealed that 45% of respondents reported that a member of their household had lost a job and that, for those owning a small family business, 58% had a household member who had closed their business. These effects are considerably more pronounced among the households with lower incomes, with nearly 71 percent reporting that a household member lost their job and 61 percent reporting that a household member closed their business compared to only 14 percent who report that a household member lost their job and 54 percent reporting that a household member closed their business among those households with higher incomes (Bottan et al., 2020 ).

It is estimated that the global recession augmented global extreme poverty by 88 million people in 2020, and an additional 35 million in 2021 (World Bank, 2020 ). A survey conducted by UNICEF in Mexico documented a 6.7% increase in hunger and a 30% loss in household income between May and July of 2020 (UNICEF México, 2020 ).

Because schools in some countries offer a delivery channel for meals as part of poverty reduction programming, several countries created alternative arrangements during the pandemic to deliver those or replaced them with cash transfer programs. Sao Paulo, Brazil, for instance, created a cash transfer program “ Merenda en Casa ’’ to replace the daily meal school programs (Dellagnelo & Reimers, 2020 ; Sao Paulo Government, 2020 ).

In the summer of 2020, Save the Children conducted a survey of children and families in 46 countries to examine the impact of the crisis, focusing on participants in their programs, other populations of interest, and the general public. The report of the findings for program participants—which include predominantly vulnerable children and families—documents violence at home, reported in one third of the households. Most children (83%) and parents (89%) reported an increase in negative feelings due to the pandemic and 46% of the parents reported psychological distress in their children. For children who were not in touch with their friends, 57% were less happy, 54% were more worried, and 58% felt less safe. For children who could interact with their friends less than 5% reported similar feelings. Children with disabilities showed an increase in bed-wetting (7%) and unusual crying and screaming (17%) since the outbreak of the pandemic, an increase three times greater than for children without disabilities. Children also reported an increase in household chores assigned to them, 63% for girls and 43% for boys, and 20% of the girls said their chores were too many to be able to devote time to their studies, compared to 10% of boys (Ritz et al., 2020 ).

1.7 Readiness for Remote Teaching During a Pandemic

Countries varied in the extent to which they had, prior to the pandemic, supported teachers and students in developing the capacities to teach and to learn online, and they varied also in the availability of resources which could be rapidly deployed as part of the remote strategy of educational continuity. Table 1.2 shows the extent to which teachers were prepared to use Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in their teaching based on a survey administered by the OECD in 2018. The percentage of teachers who report that the use of ICT was part of their teacher preparation ranges from 37 to 97%. There is similar variation in the percentage of teachers who feel adequately prepared to use ICT, or who have received recent professional development in ICT, or who feel a high need for professional development in ICT. There is also quite a range in the percentage of teachers who regularly allow students to use ICT as part of their schoolwork.

This variation, along with variation in availability of technology and connectivity among students, creates very different levels of readiness to teach remotely online as part of the strategy of educational continuity during the interruption of in-person instruction.

1.8 What are the Short-term Educational Impacts of the Pandemic?

The study of the ways in which the pandemic can be expected to influence the opportunity to learn can be based on what is known about the determinants of access to school and learning, drawing on research predating the pandemic.

Opportunity to learn can be usefully disaggregated into opportunity to access and regularly attend school, and opportunity to learn while attending and engaging in school. John Carroll proposed a model for school learning which underscored the primacy of learning time. In his model, learning is a function of time spent learning relative to time needed to learn. This relationship between aptitude (time needed to learn) and learning is mediated by opportunity to learn (amount of time available for learning), ability to understand instruction, quality of instruction, and perseverance (Carroll, 1963 ).

In a nutshell, the pandemic limited student opportunity for interactions with peers and teachers and for individualized attention—decreasing student engagement, participation, and learning—while augmenting the amount of at-home work which, combined with greater responsibilities and disruptions, diminished learning time while increasing stress and anxiety, and for some students, aggravated mental health challenges. The pandemic also increased teacher workload and stress while creating communication and organizational challenges among school staff and between them and parents.

Clearly the pandemic constrained both the home conditions and the school conditions that support access to school, regular attendance, and time spent learning. The alternative strategies deployed to sustain the continuity of schooling in all likelihood only partially restored opportunity to learn and quality of instruction. Given the lower access that disadvantaged students had to technology and connectivity, and the greater likelihood that their families were economically impacted by the pandemic, it should be expected that their opportunities to learn were disproportionately diminished, relative to their peers with more access and resources and less stressful living conditions.