New report | Russia's economy faces growing imbalances as war effort drains resources

Russia's economy under the fog of war

Russia’s war against Ukraine has placed its economy under unprecedented pressure, and this pressure has grown as sanctions continue to take effect. Before the war, the Russian economy was heavily dependent on oil exports, and fluctuations in international oil prices were the main driver of its economic health. Since the full-scale invasion in February 2022, Russia has faced severe sanctions that have disrupted its trade patterns, limited its access to foreign exchange reserves, and restricted the functioning of its financial system.

How the war is reshaping Russia's economic future

The purpose of this report is to assess the current state of the Russian economy in light of the ongoing war and sanctions. It aims to provide a clearer picture of how economic indicators like inflation and GDP growth are affected by Russia’s military actions and how the economy is changing under the weight of sanctions and financial pressure. It also seeks to explore how these changes may affect Russia’s long-term economic outlook, especially in terms of investment, productivity, and growth.

"One of the biggest challenges is obtaining reliable data, as much of Russia's economic reporting has become entangled with wartime propaganda. The Russian government has stopped publishing large swaths of data, and the numbers that are available are often skewed to present a more favorable picture," the researchers note in the report.

Key issues:

- Russian economic statistics should be treated with caution : Official statistics, such as GDP growth and inflation rates, have been manipulated to support the narrative that the Russian economy is stable, but alternative measures suggest a different reality.

- Mounting economic imbalances : An increasingly inconsistent mix of fiscal stimulus and monetary tightening in Russia's economic policies may lead to an economic crisis.

- Dependence on oil prices : The price of oil remains a critical factor for Russia's economic health, with any drop in oil prices directly impacting the country’s foreign exchange revenues, inflation, and overall economic stability.

A shrinking financial cushion

The report warns that the Russian government’s financial reserves, which have been used to finance war expenditures, are depleting rapidly and could run out within a year. Once these reserves are exhausted, the central bank will face pressure to loosen its key interest rate, or even resort to printing more money, leading to potentially high inflation and a weakened ruble.

- Read the full report

- Watch the seminar hosted by the Swedish Government

This report was written by a team of researchers at SITE, affiliated with the Stockholm School of Economics (SSE).

- Anders Olofsgård , Deputy Director at SITE and Associate Professor at SSE. Email: [email protected]

SITE was set up as a research institute at the Stockholm School of Economics (SSE) in 1989 with the mandate of studying developments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Today, SITE is a leading research-based policy institute on these issues. SITE has also built a network of research institutes in the region ( FREE Network ) that includes the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE). KSE not only provides a premier economics education to future leaders in Ukraine but is also involved in the analysis of the Ukrainian, as well as the Russian, economy, including analysis of the role of sanctions in limiting Russia’s destructive capacity. KSE has been an important contributor of data and analysis that underlies this report.

Photo: UladzimirZuyeu, Shutterstock

related news

New report reveals Russia’s core shadow fleet, calls for strengthened sanctions

Milestones in economic research and institution building | SITE’s 35th Anniversary

New chapters by Anders Åslund and Torbjörn Becker focus on Ukraine’s and Russia’s connections to the EU

Shaping the future together: Stockholm summit on rebuilding war-torn Ukrainian municipalities

- Yale University

- About Yale Insights

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

A Year after the Invasion, the Russian Economy Is Self-Immolating

Economic pressure and a talent drain are driving Russia into permanent irrelevance, write Yale SOM’s Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and Steven Tian.

A vacant commercial building in Moscow on February 10.

- Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld Senior Associate Dean for Leadership Studies & Lester Crown Professor in the Practice of Management

- Steven Tian Director of Research, Chief Executive Leadership Institute

This commentary originally appeared in Fortune.

A year after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, some cynics lament that the unprecedented economic pressure campaign against Russia has not yet ended the Putin regime. What they’re missing is the transformation that has happened right before our eyes: Russia has become an economic afterthought and a deflated world power.

Coupled with Putin’s own misfires, economic pressure has eroded Russia’s economic might as brave Ukrainian fighters, HIMARS, Leopard tanks, and PATRIOT missiles held off Russian troops on the battlefield. This past year, the Russian economic machine has been impaired as our original research compendium shows. Here are Russia’s most notable economic defeats:

Russia’s permanent loss of 1,000+ global multinational businesses coupled with escalating economic sanctions

The 1,000+ global companies who voluntarily chose to exit Russia in an unprecedented, historic mass exodus in the weeks after February 2022, as we’ve faithfully chronicled and updated to this day, have largely held true to their pledges and have either fully divested or are in the process of fully separating from Russia with no plans to return.

These voluntary business exits of companies with in-country revenues equivalent to 35% of Russia’s GDP that employ 12% of the country’s workforce were coupled with the imposition of enduring international government sanctions unparalleled in their scale and scope, including export controls on sensitive technologies, restrictions on Russian elites and asset seizures, financial sanctions, immobilizing Russia’s central bank assets, and removing key Russian banks from SWIFT, with even more sanctions planned.

Plummeting energy revenues thanks to the G7 oil price cap and Putin’s punctured natural gas gambit

The Russian economy has long been dominated by oil and gas, which accounts for over 50% of the government’s revenue, over 50% of export earnings, and nearly 20% of GDP every year.

In the initial months following the invasion, Putin’s energy earnings soared. Now, according to Deutsche Bank economists, Putin has lost $500 million a day of oil and gas export earnings relative to last year’s highs, rapidly spiraling downward.

The precipitous decline was accelerated by Putin’s own missteps. Putin coldly withheld natural gas shipments from Europe–which previously received 86% of Russian gas sales–in the hopes freezing Europeans would get angry and replace their elected leaders. However, a warmer-than-usual winter and increased global LNG supply mean Putin has now permanently forfeited Russia’s relevance as a key supplier to Europe, with reliance on Russian energy down to 7%–and soon to zero. With limited pipeline infrastructure to pivot to Asia, Putin now makes barely 20% of his previous gas earnings.

However, Russia’s energy collapse is also triggered by savvy international diplomacy. The G7 oil price cap has achieved the once unimaginable balance of keeping Russian oil flowing into global markets while simultaneously cutting into Putin’s profits. Russian oil exports have held amazingly consistent at pre-war levels of ~7 million barrels a day, ensuring global oil market stability, but the value of Russian oil exports has gone from $600 million a day down to $200 million a day as the Urals benchmark crashed to ~$45 a barrel, barely above Russia’s breakeven price of ~$42 per barrel.

Even countries on the sidelines of the price cap scheme, such as India and China, ride the coattails of the G7 buyers cartel to secure Russian supply at deep discounts of up to 30%.

Talent and capital flight

Since last February, millions of Russians have fled the country. The initial exodus of some 500,000 skilled workers in March was compounded by the exodus of at least 700,000 Russians, mostly working-age men fleeing the possibility of conscription, after Putin’s September partial mobilization order. Kazakhstan and Georgia alone each registered at least 200,000 newly fleeing Russians desperate not to fight in Ukraine.

Moreover, the fleeing Russians are desperate to stuff their pockets with cash as they escape Putin’s rule. Remittances to neighboring countries have soared more than tenfold and they rapidly attracted ex-Russian businesses. For example, in Uzbekistan, the Tashkent IT Park has seen year-over-year growth of 223% in revenue and 440% growth in total technology exports.

Meanwhile, offshore havens for wealthy Russians such as the UAE are booming, with one estimate claiming 30% of Russia’s high-net-worth individuals have fled.

Russia will only become increasingly irrelevant as supply chains continue to adapt

Russia has historically been a top commodities supplier to the world economy, with a leading market share across the energy, agriculture, and metals complex. Putin is fast making Russia irrelevant to the world economy as it is always much easier for consumers to replace unreliable commodity suppliers than it is for suppliers to find new markets.

Supply chains are already adapting by developing alternative sourcing that is not subject to Putin’s whims. We have shown how in several crucial metals and energy markets, the combined output of new supply developments to be opened in the next two years can fully and permanently replace Russian output within global supply chains.

Even Russia’s remaining trade partners apparently prefer short-term, opportunistic spot-market purchases of Russian commodities to capitalize on depressed prices rather than investing in long-term contracts or developing new Russian supply.

It appears Russia is well on its way toward its long-held worst fear: becoming a weak economic dependent of China–its source of cheap raw materials.

The Russian economy is being propped up by the Kremlin

The Kremlin has had to prop up the economy with escalating measures, and Kremlin control is increasingly creeping into every corner of the economy with less and less space left for private sector innovation.

These measures have proven costly. Government expenditures rose 30% year-over-year. Russia’s 2022 federal budget has a deficit of 2.3%– unexpectedly exceeding all estimates despite initially high energy profits, drawdowns and transfers of 2.4 trillion rubles from Russia’s dwindling sovereign wealth fund in December, and asset fire sales of 55 billion yuan this month.

Even these measures of last resort have been insufficient. Putin has been forced to raid the coffers of Russian companies in what he calls “revenue mobilization” as energy profits decline, extracting a hefty 1.25 trillion ruble windfall tax from Gazprom’s corporate treasury with more raids scheduled–and forcing a massive 3.1 trillion ruble issuance of local debt down the throats of Russian citizens in the autumn.

More can be done

Although 2023 will exacerbate each of these trends and further batter the Russian economy, there is even more that can be done to grease the skids.

A crackdown on sanctions evasion and smugglers, perhaps through secondary sanctions in the case of Turkey and other chronic offenders, will ensure that bad actors do not feed Putin’s war machine.

Sanctions provisions across technology, financial institutions, and commodity exports can be escalated. Pressure on companies remaining in Russia to fully and immediately exit the country must be maintained. Some $300 billion in frozen foreign exchange reserves could be seized and committed to the reconstruction of Ukraine

Tightening these screws will help improve the chances that before this time next year, Russia will realize it does not need Putin, just as the world has already realized it does not need Russia.

Only then will the Russian economy and people stand a chance of returning to prosperity.

- Politics and Policy

- Special Issues

- Authors Guidelines

- Editorial Team

Russian Journal of Economics (RuJE) is an open access, peer-reviewed, quarterly journal that publishes high-quality research articles in all fields of economics related to policy issues.

Prominent on the RuJE agenda is original research on the Russian economy, economic policy and institutional reform with broader international context and sound theoretical background. This focus is not exclusive and RuJE welcomes submissions in all areas of applied and theoretical economics, especially those with policy implications. RuJE audience includes professional economists working in academia, government and private sector.

Publisher: Non-profit partnership "Redaktsiya zhurnala Voprosy Ekonomiki" (Moscow, Russia)

This website uses cookies in order to improve your web experience. Read our Cookies Policy

Russia Economic Report

December 1, 2021: 46th Issue of the Russia Economic Report

Download PDF | Press Release

The World Bank’s Russia Economic Report analyzes recent economic developments, presents the medium-term economic outlook, and provides an in-depth analysis of a particular topic.

Economic Developments

Global activity is now moderating after a strong recovery from the pandemic-induced recession. Following a sharp rebound in the second half of 2020, the pace of global growth eased in the first half of 2021, held back by renewed COVID-19 outbreaks. Growth in trade has lost momentum amid easing of global economic activity and persistent supply bottlenecks.

Russia’s economy saw a strong rebound in the first half of 2021 and is expected to grow by 4.3 percent this year. However, the momentum weakened in the second half of the year.

As COVID-19 restrictions were eased in Russia in late 2020 and early 2021, consumer demand surged ahead in the second quarter, supported by savings built up over 2020 and rapid credit growth. Investment in Russia was also strong in the second quarter of 2021 and the current account surplus reached multiyear highs on elevated commodity prices and low outbound tourism and reached $82 billion by September 2021.

However, by autumn it became clear that a damaging new pandemic wave was underway which, with relatively low vaccination rates, is a risk to both economic activity and human health. With new COVID control measures and the consumer rebound fizzling out, economic activity cooled in the third quarter.

Inflation has been on the rise throughout 2021 as Russia copes with high demand, rising commodity prices and supply bottlenecks. The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) was one of the first central banks to begin tightening monetary policy in 2021 as inflation moved above the CBR’s target rate from December 2020. Since March, it has raised rates six times, by a total of 325 basis points to stand at 7.5 percent at end-October. This move has helped maintain real interest rates around zero and shift monetary policy from an accommodative to a neutral stance.

The Russian banking sector has proven resilient throughout the COVID-19 pandemic so far, as economic recovery now helps improve balance sheets, while rapid credit growth has begun to ease.

Over the first nine months of the year, Russia’s federal budget has seen impressive increases in revenues; oil and gas revenues were up by 60 percent, and VAT and income taxes by around 30 percent each. The overall budget deficit, on a four-quarter rolling basis, shrank from 3.8 percent at end-2020 to around 1 percent in the third quarter of 2021.High oil and gas revenues meant the CBR purchased $35 billion of foreign exchange on behalf of the government during January to November 2021, to be channeled to the National Wealth Fund in 2022.

Labor markets have also recovered. Job postings from employers in 2021 jumped up 24 percent year-on-year in the second quarter and the ratio of unemployed people to job posts has fallen.

Real wage growth, which was maintained just above 2 percent in 2020, has continued this year, at an average of 2.5 percent to end-August.

Economic Outlook

As the world moves into the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, global growth is expected to moderate next year to 4.3 percent. Inflation is expected to ease gradually over 2022, but inflation rates are likely to remain above the target level for most of the year.

Growth in Russia is forecast at 2.4 percent in 2022, on the back of a continually strong oil sector, before slowing down to 1.8 percent in 2023. With vaccination rates still low, COVID-19 control measures may be called for next year, which will weigh significantly on growth.

Uncertainty around inflation remains high. Should inflation prove more persistent than expected, or if the economy faces headwinds, including from the Federal Reserve’s planned unwinding of quantitative easing in the United States, monetary policy may need to be tightened for longer, which may also adversely affect the growth outlook.

Russia’s longer-term economic prospects will depend on a number of factors. Among these, Russia continues to face relatively low potential growth which, unless addressed, will impede its ability to achieve high-level development goals and, raise incomes and living standards. Success will depend on strengthening frameworks and market-based incentives for firms to compete, innovation and building value, both domestically and through links to global value chains.

Another factor that will impact Russia’s economy in the longer-term, is the country’s new Low-Carbon Development Strategy, released by the Government on October 29, 2021. Presenting an opportunity to spur green growth, it sets out a much more ambitious scenario of climate change mitigation, which would see a 70 percent reduction in net emissions by 2050 and net carbon neutrality 10 years after that.

The strategy sets out to raise growth at the same time as greening the economy, targeting average growth of at least 3 percent per year. This ambitious twin goal of growing and greening will call for a simultaneous focus on addressing pre-existing economy-wide constraints to growth and competitiveness, while limiting the costs of green transition and taking full advantage of the opportunities it may afford.

Special Focus on Russia’s Green Transition: Pathways, Risks and Robust Policies

While a much remains uncertain about the global green transition, the pace of change is likely to gain momentum as more countries announce plans to become carbon neutral. So far, more than 60 countries, representing over 80 percent of the world economy, have expressed aspirations to reach carbon neutrality in the coming decades. There are signs of concrete policy changes in some countries around the world. It is in this context that Russia has stated its ambitions to become carbon neutral by 2060.

The special topic in this report presents scenarios and options for Russia to identify appropriate risk management approaches to the green transition of its economy. In an uncertain and changing global environment, proactive domestic policy action on climate change is an effective and robust strategy for managing risks that might otherwise impose a more disorderly and costly transition on Russia. Global green transition can also offer an opportunity to transform the economy for the better and thereby create potential for higher and more diversified growth.

The report notes that green transition calls for an overhaul of policy frameworks to change entrenched investment decisions and behavior of firms and households. Carbon pricing is a central enabler. Taking various forms – usually a tax or a tradeable permit system - carbon pricing ensures market-based incentives for all actors to account for the social cost of carbon emissions.

A successful transition will also require broader diversification of the assets of the country – including human capital, renewable natural capital, and a shift to “green” produced capital. Resources raised from carbon pricing can support this ambition, but just as important will be investing in softer assets, such as institutions, governance, innovation and entrepreneurship. This would be part of a broader reform agenda to enable the emergence of a more dynamic, competitive, and innovative private sector to take the leading role in creating an internationally competitive low-carbon Russian economy.

In its forthcoming Russia Climate Change and Development Report, the World Bank will cover sectoral challenges and opportunities, economywide enablers, and the inclusion and social aspects of green transition.

Accompanying this edition of the Russia Economic Report, a special report on consumer energy subsidies in Russia analyzes how these significant resources can also lead to increased emissions and reduced economic efficiency. New estimates by the World Bank show that Russia’s consumer subsidies on electricity, gas and petroleum amounted to 1.4 percent of GDP in 2019. By redeploying these resources, the authorities could increase GDP and ensure that no consumers are left worse off, while at the same time reducing emissions and moving forward with Russia’s ambitious goal of greener economic development.

Download the full report (PDF)

Previous Russia Economic Reports

Russia's economic recovery gathers pace.

Russia Economic Report 45 The World Bank, May 2021

Download PDF | Press Release

Russia's Economy Loses Momentum Amidst COVID-19 Resurgence; Awaits Relief from Vaccine

Russia Economic Report 44 The World Bank, December 2020

Recession and Growth under the Shadow of a Pandemic

Russia Economic Report 43 The World Bank, July 2020

Weaker Global Outlook Sharpens Focus on Domestic Reforms

Russia Economic Report 42 The World Bank, December 2019

Modest Growth; Focus on Informality

Russia Economic Report 41 The World Bank, June 2019

Russia’s Economy: Preserving Stability, Doubling Growth, Halving Poverty – How?

Russia Economic Report 40 The World Bank, December 2018

Download PDF | Press Release

The Russian Economy: Modest Growth Ahead

Russia Economic Report 39 The World Bank, May 2018

Russia's Recovery: How Strong are its Shoots?

Russia Economic Report 38 The World Bank, November 2017

From Recession to Recovery

Russia Economic Report 37 The World Bank, May 2017

Download PDF | Press Release

Earlier Russia Economic Reports can be downloaded through the World Bank's Documents & Reports.

Lead Country Economist and Program Leader for Equitable Growth, Finance and Institutions in Central Asia

Macro Poverty Outlook for Europe and Central Asia

Media contacts.

(495) 745-7000 Email

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

An economic catastrophe is lurking beneath Russia’s GDP growth as Putin ‘throws everything into the fireplace’

Even as Ukrainian advances in the Kursk region pierce Russia’s aura of military invincibility, resurgent cynics have painted an unrealistically optimistic picture of a supposedly resilient Russian economy despite sanctions and the exit of over 1,000 global multinational corporations .

This misleading narrative attributes Russia’s apparent economic continuity to aggressive government spending and efforts to shield the population from restrictive monetary policies through extreme fiscal stimulus. However, this rosy outlook is fundamentally flawed, except for one crucial observation: Russia is indeed engaged in unsustainable spending practices.

The reality of Russia’s economic situation is far more complex and concerning than some would have you believe. The productive core of the Russian economy has been severely compromised, with the government’s spending spree bearing a striking resemblance to Keynes’ famous metaphor of digging trenches and filling them with dirt—a superficial attempt to prop up GDP figures without creating genuine economic value, improving the lives of the Russian people, or improving Russian productivity. Financial, production, and human resources have been redirected en masse to the defense sector, leaving the civilian sector struggling to meet growing consumer demand. This imbalance—cannibalizing the rest of the Russian economy to fund Putin’s war—has fueled inflation, further exacerbated by the depreciation of the ruble and rising import costs.

Simply put, Putin’s administration has prioritized military production over all else in the economy, at substantial cost. While the defense industry expands, Russian consumers are increasingly burdened with debt, potentially setting the stage for a looming crisis. The excessive focus on military spending is crowding out productive investments in other sectors of the economy, stifling long-term growth prospects and innovation.

It’s crucial to approach Russian economic data with skepticism. As we’ve repeatedly highlighted , the country’s statistical services have a documented history of distorting economic indicators , making it challenging to accurately assess the true state of the economy. In light of these factors, the apparent resilience of the Russian economy is more illusion than reality, especially on the following key fronts.

Mortgaging the future to pay for Putin’s war today

Despite increases in Russian budget revenues, mostly the result of a devalued ruble, continuously growing inflation (hence growing revenues from sales tax), and new levies and taxes all over the economy: a rise in the excise duty on cigarettes and cars, a windfall tax on the metallurgical and fertilizer sector, a tax on the sale of Russian assets by Western companies, and many more—the Russian budget still finds itself running a 2% deficit of GDP, which is significant by Russian standards. Russia is fast running through the reserves that it accumulated over the 2000s and 2010s—or at least the half that is not frozen in the West and being repurposed to help Ukraine by the G7 governments. Today, the total distributable liquid assets remaining in Russia are just short of $100 billion. Putin’s cronies point to sizable yuan-denominated holdings stored with the Chinese Central Bank, ignoring the unenviable reality that this means China holds disproportionate sway over the future of Russian finances .

The biggest revenue item for Russia has always been oil and gas sector proceeds, which constitute one-third of the total budget revenues. The only reason why we see these revenues growing (still below expectations) is due to significantly higher taxes imposed on oil and gas producers, which cannibalizes their productive assets and impedes their ability to reinvest in future production, mortgaging the future to pay for Putin’s war today.

Russia has implemented a mineral extraction tax on its oil and gas giants and increased the corporate tax rate for Novatek , its only LNG producer, from 20% to 34%, while increasing the overall corporate tax rate by 25% across the board effective January 2025. Measures like these, paired with Western sanctions and the voluntary withdrawal of global multinational businesses, stifle investment critical to the future of the Russian economy. Moreover, key development projects such as Arctic LNG-2 have been brought to a halt due to the exit of companies like Linde, Baker Hughes, and Technip, along with sweeping U.S. sanctions.

Over the past months, Russian crude has been trading at an average $10 discount compared to benchmark Brent oil prices, and natural gas prices returned largely to depressed pre-war levels, as we clearly see reflected in the poor economic performance of the Russian state giants. Gazprom’s net loss amounted to 480.6 billion rubles for the period from January to June 2024, compared to a net loss of 255 billion rubles in the same period last year—a record for poor performance. Additionally, the net sales of foreign currencies by the largest exporters fell to $11.5 billion in July from $14.5 billion in June.

The only reason why the budget revenues continue to increase is because of harmful inflation and the overall labor shortage in Russia—partially thanks to the exodus of millions of educated Russian workers following Putin’s invasion—which translates to insatiable wage pressure and spikes in the prices of manufactured goods. Russia is bleeding dry its private sector, which has a hard time competing against the defense sector wages. None of that is sustainable in the longer term. The Russian budget is effectively an act of desperation in wartime. Putin is throwing everything into the fireplace—and it’s completely unsustainable.

The Kremlin is forcing the increasingly heavy costs of its war on the Russian population

The Kremlin’s approach to social welfare and resource allocation during wartime reveals a stark contrast between military spending and civilian welfare. While the government has poured an estimated 2.75 to 3 trillion rubles (equivalent to 1.4-1.6% of Russia’s expected GDP in 2024) into payments for soldiers, the wounded, and families of the deceased, the civilian population faces a different reality. These military payments, amounting to 3.4-3.7% of all consumer spending by Russians in 2023, have further increased inflationary pressures. However, Russia’s war Keynesianism masks the true wretched state of welfare for the broader population. Announced increases in pensions and public sector salaries often fail to materialize, with public sector salary increases implemented in merely 13% of Russian regions , despite Putin’s decrees—exposing a huge gap between propaganda and reality.

The methodology for calculating these salaries is manipulated through procedural tricks, such as reducing employee numbers through sleight of hand. Consequently, 60% of Russian physicians report that their salaries are insufficient to meet basic needs, with 80% working multiple jobs to make ends meet . Meanwhile, Russia has experienced a massive brain drain, losing over a million highly educated individuals, 86% of whom are under the age of 45 and 80% college degree holders, according to a French Institute of International Relations report.

Notwithstanding the political repressions imposed by the Kremlin, there is a strong economic rationale for this dramatic talent flight. IT workers’ salaries in Russia have decreased by 15-25% in 2024, down to 150,000 rubles , driven in part by the exodus of global multinational companies from the country.

The redistribution of welfare is clearly targeted, prioritizing military expenditures over civilian needs and effectively shifting the economic burden of the war onto the broader Russian population while creating an illusion of economic stability through military spending for a tiny subsection of beneficiaries.

Unsustainable monetary policy and trade weakness are revealing structural flaws in Russia’s economy

The inflationary pressures on the Russian economy remain high, despite the Russian Central Bank setting an interest rate of 18%. An annualized rate of price increases from May to July stands at 10%, driven significantly by war spending. This economic militarization is accelerating inflation in a fundamental way: increased production of military goods boosts employment and wages, but the resulting surge in demand isn’t matched by a corresponding increase in consumer goods production. Normally, such an imbalance would be offset by increased imports. Under current conditions, this correction isn’t occurring. In fact, according to the Russian Central Bank’s preliminary estimate, imports in May 2024 were 10% lower than in May 2023 , exacerbating the supply-demand mismatch.

The business environment is rapidly deteriorating, with the Russian Central Bank’s assessment showing an almost crisis-like 4.75-point monthly decline . Labor shortages are driving unsustainable wage growth, especially in the military-industrial complex, creating an inflationary wage spiral. While seemingly positive for workers, wage growth is outpacing the minimal productivity gains in Russia while fueling further inflation, which is borne by those very workers as they live their everyday lives. Russian businesses, having levered up in expectation of rate cuts, now face a harsh reality in an increasingly closed economy where such cuts are unlikely. The increase in output is not structural but driven by idiosyncrasies such as the completion of large metalworking orders , predominantly concentrated in the state-controlled armaments industry. All these factors combine to create a self-reinforcing cycle of inflation and economic instability, pointing towards an impending downturn and threatening to destabilize the entire economic structure.

The notion that increased interest rates will attract Indian and Chinese investors to Russia is also fundamentally flawed. In reality, Russian treasuries have become toxic assets, and the country teeters on the brink of financial insolvency. The country has become completely cut off from global financial markets and pools of capital. Simply put, no investor from anywhere in the world wants to purchase Russian securities. The only buyers of Russian sovereign bonds at scale are Russian financial institutions, making it impossible for Russia to finance its large deficits. Furthermore, it has become impossible for Russian companies to tap into global debt or equity markets to raise desperately needed funds. The idea that ruble-yuan transactions could form the foundation of a new, non-dollar financial world order, as many Putin cronies optimistically predict, is laughable, with a vast majority of global trade transacted in the dollar.

Moreover, China is not helping Russia financially, contrary to popular belief and no matter whatever political rhetoric the two countries may engage in. The stark disparity in interest rates between Russia and China illustrates the misalignment of their economies. While the interest rate on overnight yuan transactions in Russia hovers near 20%, Chinese banks lend to each other at rates closer to 2%. This gulf in lending rates represents a fundamental disconnect between the two economies. Furthermore, the fact that 80% of Russia’s yuan transactions are being reversed due to fears of secondary sanctions from Chinese financial institutions underscores the reluctance of these institutions to engage with Russia. Even direct commodity payments, traditionally a staple of Russian-Chinese trade, are being frozen, according to Bloomberg reports . This paints a clear picture: Chinese financial institutions are unwilling to lend to Russia, effectively isolating it from a key potential ally, out of their own pragmatic financial self-interest, regardless of the rhetoric of political leaders.

Similarly, the hope of Putin’s cronies that investors from India and China would seamlessly replace Western oil and gas companies in Russia has also proven to be unrealistic. Indian investment in Russia has stagnated and totaled a mere $14 bln by the end of 2023 , close to pre-war levels, while the overall value of greenfield foreign direct investments from all countries decreased from $14.9 bln in 2021 to a meager $300 million in 2022.

The current climate of fear surrounding secondary sanctions and stringent wartime regulations has deterred significant investment out of pure financial self-interest. Even Chinese companies that had previously shown interest, such as Sinopec , have suspended operations and investment talks in Russia.

The forced pivot to Chinese technology has also proven costly for Russia. Novatek, for instance, reported a staggering $4 billion increase in capital expenditures for its Arctic LNG-2 project, attributed to the necessity of replacing Western equipment with Chinese alternatives.

It appears that China, India, and other Global South nations are more interested in buying discounted Russian energy than in making substantial investments in the country’s economy. Russians themselves were not capable of filling the economic niches left by the 1,000 multinationals with combined assets of over $220 billion that curtailed their operations in Russia.

For all the government spending, the rest of the economy is stagnant. The contribution of import substitution schemes to economic growth remains modest at best. Every Russian company that has tried to step into the vacated footsteps of Western predecessors still lacks crucial know-how and access to capital, being completely cut off from global capital markets. And Western pundits don’t understand that oil is now being sold at breakeven prices given Russia’s highly inefficient production costs and high transportation costs to its now-more-distant customers while natural gas remains virtually unsold.

The financial strain is not limited to cross-border trade and investment—it’s increasingly evident in the domestic credit market as well. Russians are facing growing difficulties in obtaining personal loans, a trend that signals deepening economic troubles at the household level. In July, the approval rate for unsecured consumer loan applications plummeted to a year-to-date low of 36%, down from 41% in June. This means that nearly two-thirds of Russians seeking cash loans are being turned away empty-handed, a stark indication of the tightening lending policies of Russian banks.

In conclusion, the apparent resilience of the Russian economy is largely illusory, built on a precarious foundation of unsustainable government spending and short-term market factors. The recent ostensible growth spurt masks deep-seated structural weaknesses. As unsustainable stimulus inevitably fades, Russia faces an unenviable perfect storm of challenges: the exhaustion of foreign exchange reserves, an irreversibly strained labor market, rising inflation outside the control of the central bank, and the heavy burden of military expenditures for years to come.

The government’s approach has redirected resources away from productive sectors, cannibalizing the rest of the Russian economy to fund Putin’s war and stifling long-term growth prospects and innovation. With the economy having absorbed the wartime stimulus through credit expansion and increased investment into the defense industry, it now stands at a precipice. A significant economic slowdown or recession appears not just possible but increasingly probable.

Russia is set on a long-term trajectory of structural challenges under the weight of sanctions and elevated government spending—and the true cost of its economic policies is becoming ever more apparent. A looming economic catastrophe driven by the fundamental flaws in Russia’s current strategy will likely set the stage for severe long-term consequences that will play out in the years ahead.

More must-read commentary published by Fortune :

- Markets have overestimated AI-driven productivity gains , says MIT economist

- Brian Niccol may well be the messiah Starbucks—and Howard Schultz—have been looking for

- ‘Godmother of AI’ says California’s well-intended AI bill will harm the U.S. ecosystem

- The ‘Trump dump’ is back—and the stocks that he targets are crashing

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune .

Latest in Commentary

Here’s what it would take for Europe to successfully compete with the U.S. and China, according to EY

The world needs innovative antiviral drugs—but market incentives won’t align until it’s too late, Germany’s ‘head of challenges’ warns

AI regulation gets a bad rap—but lawmakers around the world are doing a decent job so far

Randstad CEO: Coming out at work was crucial for my career—but I was lucky

Trans+ employees are not alone in bearing the burden of bigotry—it costs employers, too

After 2 years of peddling Putin’s propaganda, the IMF is returning to Russia in open defiance of the West

Most popular.

The college student who tracks private jets of Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, and Taylor Swift says his Meta Threads accounts were suspended

Billionaire Mark Cuban doesn’t understand how anyone in business or any hard working American would vote for Trump after his outburst at a rally when his mic dropped out

EY fired dozens of staff members who attended 2 video training meetings simultaneously

2 major polls show Donald Trump gaining slight edge over Kamala Harris in election race

A 19-year-old Walmart employee was found dead inside the bakery’s walk-in oven. Police say the investigation is ‘complex’

Ozempic and Wegovy are trimming waistlines—and showing how quickly U.S. health care can turn into a gold rush

The Contemporary Russian Economy

A Comprehensive Analysis

- © 2023

- Marek Dabrowski 0

Bruegel, Brussels, Belgium

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- Provides a comprehensive and wide-ranging overview of the Russian economy in the 2020s

- Studies the Russian economy comparatively with other emerging-market and advanced economies

- Provides a benchmark for students to assess Russia's strengths, weaknesses, and future challenges

9910 Accesses

11 Citations

2 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

This textbook offers a wide-ranging, comprehensive analysis of the contemporary Russian economy (as it functions in the early 2020s) concentrated on the economy, economic policy, and economic governance. Chapters cover recent Russian economic history, the economic geography of Russia, natural resources, population, major sectors and industries, living standards and social policy, institutions, governance, economic policy, and Russia's role in the global economy. The book will provide a comparative cross-country context, analysing how the Russian economy and its institutions perform compared to its peers to help students and instructors understand Russia’s strengths, weaknesses, and future challenges. Prepared by a team of leading Russian and international experts on the respective topics, this textbook will be of interest to those studying Russian economics. It will be valuable reading for undergraduate and graduate students of Russian studies, the Russian economy, Russian politics,the economics of transition, the economics of emerging markets, and international relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Global Fields and Economic Theory: The Impact of German Scholarship on Russian Political Economy in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century

Ordoliberalism: neither exclusively German nor an oddity. A review essay of Malte Dold’s and Tim Krieger’s Ordoliberalism and European Economic Policy: Between Realpolitik and Economic Utopia .

Russian Economy

- Russian economic policy

- regional development

- social policy

- institutions and governance

- natural resources

- Russian studies

- the economics of transition

- the economics of emerging markets

- contemporary Russian economic history

- economic geography of Russia

- Russia's role in the global economy

Table of contents (19 chapters)

Front matter, natural and human resources, natural resources, geography, and climate.

- Leonid Limonov, Denis Kadochnikov

Human Resources

- Irina Denisova, Marina Kartseva

Historical Roots

Capitalist industrialisation and modernisation: from alexander’s reforms until world war i (the 1860s–1917).

- Carol Scott Leonard

The Soviet Economy (1918–1991)

Institutions and their transformation, constitutional foundations of the post-communist russian economy and the role of the state.

- Christopher A. Hartwell

Business and Investment Climate, Governance System

Marek Dabrowski

Evolution of Ownership Structure and Corporate Governance

- Alexander Radygin, Alexander Abramov

Major Sectors and Regional Diversity

Structural changes in the russian economy since 1992.

- Svetlana Avdasheva

Energy Sector

- Przemyslaw Kowalski

Agriculture

- Eugenia Serova

Regional Diversity

- Leonid Limonov, Olga Rusetskaya, Nikolay Zhunda

Russia in the Global Economy

Russia in world trade.

- Arne Melchior

Foreign Investment

- Kalman Kalotay

Sanctions and Forces Driving to Autarky

- Marek Dabrowski, Svetlana Avdasheva

Editors and Affiliations

About the editor.

Marek Dabrowski is a Non-Resident Scholar at Bruegel, Brussels, Professor of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, and Co-founder and Fellow at CASE - Center for Social and Economic Research in Warsaw. He was a co-founder of CASE (1991), former Chairman of its Supervisory Council and President of Management Board (1991-2011), Chairman of the Supervisory Board of CASE Ukraine in Kyiv (1999-2009 and 2013-2015), and Member of the Board of Trustees and Scientific Council of the E.T. Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy in Moscow (1996-2016).

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : The Contemporary Russian Economy

Book Subtitle : A Comprehensive Analysis

Editors : Marek Dabrowski

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17382-0

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance , Economics and Finance (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-031-17381-3 Published: 02 January 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-17382-0 Published: 01 January 2023

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXXVII, 410

Number of Illustrations : 71 b/w illustrations

Topics : International Economics , Economy-wide Country Studies , Economic Growth , Russian, Soviet, and East European History , Political Economy/Economic Systems

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Articles on Russian economy

Displaying 1 - 20 of 35 articles.

Ukraine’s cross-border incursion challenges Moscow’s war narrative – but will it shift Russian opinion?

Peter Rutland , Wesleyan University

Russia has become so economically isolated that China could order the end of war in Ukraine

Renaud Foucart , Lancaster University

How Russia has managed to shake off the impact of sanctions – with a little help from its friends

Keith A. Preble , Miami University and Charmaine N. Willis , Skidmore College

Russia’s economy is now completely driven by the war in Ukraine – it cannot afford to lose, but nor can it afford to win

Q&A with Sergei Guriev: ‘The optimistic scenario is the departure of Vladimir Putin in whatever way’

Sergei Guriev , Sciences Po

Empire building has always come at an economic cost for Russia – from the days of the czars to Putin’s Ukraine invasion

Christopher A. Hartwell , ZHAW School of Management and Law and Paul Vaaler , University of Minnesota

More corrupt, fractured and ostracised: how Vladimir Putin has changed Russia in over two decades on top

Matthew Sussex , Australian National University

Prigozhin revolt raised fears of Putin’s toppling – and a nuclear Russia in chaos

Gregory F. Treverton , USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

How Russia is shifting to a war economy in the face of international sanctions

Christoph Bluth , University of Bradford

Ukraine war: life on Russia’s home front after ten months of conflict

Alexander Titov , Queen's University Belfast

‘Great resignation’ appears to be hastening the exodus of US and other Western companies from Russia

Steven Kreft , Indiana University and Elham Mafi-Kreft , Indiana University

Russia faces first foreign default since 1918 – here’s how it could complicate Putin’s ability to wage war in Ukraine

Michael A. Allen , Boise State University and Matthew DiGiuseppe , Leiden University

Russian ruble’s recovery masks disruptive impact of West’s sanctions – but it won’t make Putin seek peace

The cost of war: how Russia’s economy will struggle to pay the price of invading Ukraine

Meet Russia’s oligarchs, a group of men who won’t be toppling Putin anytime soon

Stanislav Markus , University of South Carolina

How Vladimir Putin’s security obsession has eroded Russian living standards

Richard Foltz , Concordia University

Ukraine: why the sanctions won’t topple Putin

Sergey V. Popov , Cardiff University

Ordinary Russians are already feeling the economic pain of sanctions over Ukraine invasion

US-EU sanctions will pummel the Russian economy – two experts explain why they are likely to stick and sting

David Cortright , University of Notre Dame and George A. Lopez , University of Notre Dame

How Joe Biden could increase pressure on Vladimir Putin if their June 16 meeting fails to deter Russia’s ‘harmful’ behavior

Scott L. Montgomery , University of Washington

Related Topics

- Biden administration

- Russian central bank

- Russia sanctions

- Ukraine invasion 2022

- Vladimir Putin

Top contributors

Co-Director of the Centre for Russian, European and Eurasian Studies, University of Birmingham

Senior Lecturer in Economics, Lancaster University Management School, Lancaster University

Professor of Government, Wesleyan University

Senior Lecturer in Economics, Cardiff University

Professor of International Relations and Security, University of Bradford

PhD Candidate, KU Leuven

Professor in The Division of Global Affairs and The Department of Political Science, Rutgers University - Newark

Professor of International Management & Political Economy, Loughborough University

Professor of International Political Economy, University of California, Santa Barbara

Professor of IPE, Director of City Political Economy Research Centre (CITYPERC), City St George's, University of London

Associate Professor of Security and International Relations, University of Staffordshire

Senior lecturer, St Petersburg State University

Associate Professor of International Business, University of South Carolina

Clinical Associate Professor of Business Economics, Indiana University

Assistant Professor, Economics, University of Pittsburgh

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: The surprising resilience of the Russian economy

- Almost no Russian oil is sold below $60 cap, say western officials

- The shadowy network smuggling European microchips into Russia

- US seeks to thwart Russia’s ambition to become a major LNG exporter

- EU leaders back using earnings from Russia’s frozen assets to help Ukraine

- Russia pulls out of Black Sea grain deal

- Franco-Polish curbs on Ukrainian imports risk extending war, Kyiv says

The surprising resilience of the Russian economy

- The surprising resilience of the Russian economy on x (opens in a new window)

- The surprising resilience of the Russian economy on facebook (opens in a new window)

- The surprising resilience of the Russian economy on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- The surprising resilience of the Russian economy on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Anastasia Stognei in Tbilisi and Max Seddon in Riga

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Addressing a crowd of activists on Friday in Tula, the capital of Russia’s arms industry, Vladimir Putin crowed that the country’s economy had defeated western sanctions imposed after his invasion of Ukraine.

“They predicted decline, failure, collapse — that we would stand back, give up, or fall apart. It makes you want to show [them] a well-known gesture, but I won’t do that, there are a lot of ladies here,” Putin said to a round of applause. “They won’t succeed! Our economy is growing, unlike theirs.”

Russia’s president gloated that Russia’s economy had not only withstood an onslaught of sanctions from western countries — but was now bigger than all but two of them. He was referring to the World Bank’s ranking of GDP by purchasing power parity, by which Russia slightly edges ahead of Germany. “All of our industry did their part,” he said.

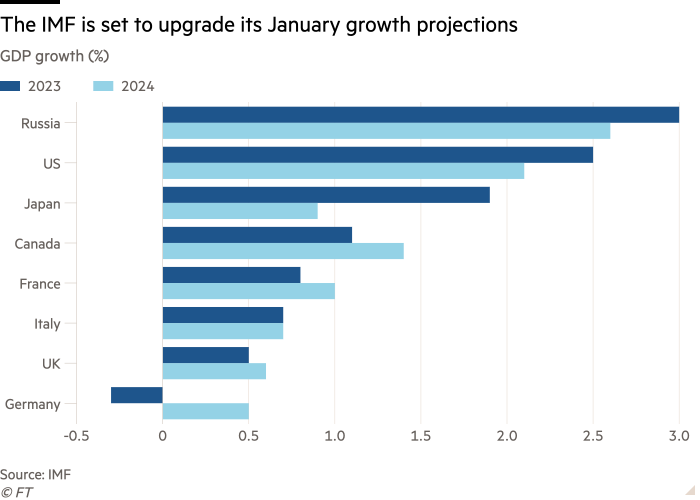

On Tuesday, the IMF appeared to concur with Russia’s president. The IMF revised its own GDP growth forecast for Russia to 2.6 per cent this year, a 1.5 percentage point rise over what it had predicted last October.

The Russian economy’s resilience has stunned many economists who had believed the initial round of sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine nearly two years ago could cause a catastrophic contraction.

Instead, they say, the Kremlin has spent its way out of a recession by evading western attempts to limit its revenues from energy sales and by ramping up defence spending.

Russia is directing a third of the country’s budget — Rbs9.6tn in 2023 and Rbs14.3tn in 2024 — towards the war effort, a threefold increase from 2021, the last full year before the invasion. This includes not only producing hardware, but also giving war-related social payments to those who fight in Ukraine and their families, as well as some spending on the occupied territories.

Some content could not load. Check your internet connection or browser settings.

The significant increase in military expenditure marks “a striking break with Russia’s post-Communist development to date”, a recent Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) paper concluded.

Putin’s own top economic officials have warned a surge in public spending comes at the risk of a major overheating of the economy in the near future. But for the time being, it is keeping growth robust.

All of this would have been impossible if Russia had not continued to generate colossal revenues from its energy resources, despite sanctions.

In 2023, Russia’s energy revenues reached Rbs8.8tn — a decline of about a quarter from the record-breaking result in 2022 but above the average for the past ten years. Despite this, the state has had to resort to increasingly irregular methods to generate revenue from one-off taxes and levies, including “voluntary donations” western businesses have to pay when leaving Russia.

“The regime is resilient because it sits on an oil rig,” says Elina Ribakova, a non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “The Russian economy now is like a gas station that has started producing tanks.”

As he announced Russia’s staggering military spending to lawmakers in September, finance minister Anton Siluanov used a Soviet slogan from the second world war to describe the Kremlin’s approach to the budget.

“Everything for the front, everything for victory,” Siluanov said.

The Kremlin’s shift to what Vasily Astrov, a senior economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW), calls “military Keynesianism” is a radical break from the conservative macroeconomic policy of Putin’s first two decades in power.

Technocrats like Siluanov and central bank governor Elvira Nabiullina helped steer Russia through multiple financial crises by aggressively targeting inflation, shoring up the country’s banking system, building up foreign currency reserves, and attempting to rein in additional spending.

That approach also proved crucial in mitigating the initial impact of the sanctions at the war’s outset, when western countries froze $300bn of Russia’s sovereign reserves and the Kremlin imposed currency controls to halt an exodus of capital and a run on the banks.

“The economic bloc [the finance ministry and central bank] keeps saving the regime. They have proven to be much more useful for Putin than the generals,” says Alexandra Prokopenko, a former Russian central bank official.

Avoiding a bigger contraction in the economy allowed the Kremlin to pivot to fuelling growth through spending, Astrov says. Although the authorities officially continue to refer to the war in Ukraine as a “special military operation”, the entire country’s economy has shifted to producing for the war.

Addressing a group of arms producers on Friday, Putin said they were “guaranteed to be filling orders for years to come” as Russia ramped up its weapons production and said the defence ministry was paying suppliers 80 per cent of the costs in advance.

The drive to produce more missiles, artillery, and drones in particular, is paying dividends for Russia on the battlefield at a time when Ukraine is struggling to secure funding for the advanced western weaponry Kyiv needs to beat back the invasion.

Putin and other top Russian officials have made a point of complaining that even the recent surge in production is insufficient. On Wednesday, defence minister Sergei Shoigu gave a public dressing down to the head of one of Russia’s weapons manufacturers over what he said was a lag in production of a “promising new artillery system”.

“If we have the chance, then we need to make use of it,” Shoigu said.

Ukraine’s army chief Valery Zaluzhny admitted this week that Kyiv and its allies had not done enough to improve Ukraine’s capabilities at a time when Russia’s ability to reinvest in its own defence industry had given it a significant firepower advantage.

The Russian finance ministry estimates that war-related fiscal stimulus in 2022-23 was equivalent to around 10 per cent of GDP. In that same period, war-related industrial output has risen 35 per cent while civilian production has remained flat, according to research published by the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies. Putin claimed on Friday that civilian production had increased by 27 per cent since the start of the war, but did not cite a source for the figure.

“The verities of economic policy cease to apply when a government prioritises war over all else. Russia’s decision [to dispense] with two decades of prudent economic policies caught many by surprise, not just forecasters,” the Bank of Finland researchers wrote in their most recent forecast for Russia.

Economists and even some of the Kremlin’s own top technocrats have warned, however, that the rampant spending is already exposing new cracks in the Russian economy. Instead of lessening its dependence on oil and gas export sales, which make up about a third of budget income, Putin’s wartime drive has created a new addiction: military production.

“The longer the war lasts, the more addicted the economy will become to military spending,” WIIW economists wrote in their January paper. “This raises the spectre of stagnation or even outright crisis once the conflict is over,” they added.

The growth is already creating imbalances that could become more pronounced over time. This is particularly noticeable on Russia’s labour market, where Russia’s army and its weapons factories are sucking in a growing number of workers on inflated wages — Putin said on Friday that Russia had created 520,000 new jobs in the industry — to man the round-the-clock shifts needed to achieve defence production targets.

This has created labour shortages in civilian industry amid an already bleak demographic outlook exacerbated by the war. Russia mobilised 300,000 men into the army in 2022 and claims to have recruited a further 490,000 in 2023. At least as many more, meanwhile, have fled the country to avoid being sent to the front.

“The greatest shortage of personnel is observed in the machine-building and chemical industries, many enterprises are forced to work in several shifts to fulfil orders received from the state,” analysts from the Gaidar Institute in Moscow wrote in December 2023.

To compete for labour against military production — which offers an exemption from the draft in addition to generous wages — the civilian sector has also had to increase salaries, which in turn drives domestic demand but adds to inflationary pressures.

If the sanctions have failed to stop Russia from spending, however, the restricted access to international markets has driven up the cost of imports, creating another potential economic trap for the Kremlin.

The circuitous routes goods now take to Russia are hitting consumers hard and weakening the rouble, which lost around 30 per cent of its value against the dollar in 2023.

“The huge budget expenses combined with Russia’s isolation . . . create an effect that’s like when you put dough in a plastic container,” says Prokopenko, a non-resident fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin. “It rises until it runs into the roof, and then there’s nowhere to go.”

The surge in public spending has driven inflation up to 7-7.5 per cent, prompting the central bank to raise the key interest rate to 16 per cent — a higher rate even than in Ukraine.

Following the rate rise, central bank governor Nabiullina warned the spending ran the risk of overheating Russia’s economy. “Trying to use dovish fiscal policy to grow beyond our potential will drive price growth [inflation] that’s going to eat more and more into savings and wage growth. And there won’t be any real growth in household wealth as a result,” she said.

The pace of growth may also not be sustainable even if Russia keeps up its current level of military spending, economists say.

Even analysts from the state-owned Russian Academy of Sciences say limited capacity means key sectors of the economy are already showing “signs of a slowdown”. These include a decline in railway transport loading, which is one of the primary indicators of an economic recession, they wrote in a note.

Other economists argue that Russia’s economy would have grown in consecutive years at a much more sustainable level if Putin had not ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

“2022 began from a very optimistic note, and the growth even surpassed most expectations. I would have expected that both in 2022 and 2023, we could have anticipated an annual GDP growth of around 3 per cent,” says Ruben Enikolopov, a research professor with Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona.

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

Letter in response to this article :

Even after the war ends, Moscow may pose a threat / From Abigail MacCartney, Oakham, Leicestershire, UK

Promoted Content

Explore the series.

Follow the topics in this article

- Global Economy Add to myFT

- Russian politics Add to myFT

- War in Ukraine Add to myFT

- Russian business & finance Add to myFT

- Russian economy Add to myFT

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

- Economy & Politics ›

Economy of Russia - statistics & facts

The impact of the war in ukraine on the russian economy, energy sector is crucial to the russian economy, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in Russia 2029

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia 2019-2029

Monthly inflation rate in Russia 2022-2024

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Wages & Salaries

Average nominal wage per month in Russia 1995-2023

Unemployment rate in Russia monthly 2020-2024

Government Finances

National debt in Russia 2011-2023

Further recommended statistics

Gross domestic product.

- Basic Statistic Countries with the largest gross domestic product (GDP) 2024

- Basic Statistic Gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2029

- Basic Statistic Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in Russia 2029

- Basic Statistic Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia 2019-2029

- Basic Statistic Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia quarterly 2018-2024

- Basic Statistic Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia monthly 2019-2024

- Basic Statistic Value added by selected industries as a GDP share in Russia 2023

- Basic Statistic Oil and gas sector as a share of GDP in Russia quarterly 2017-2023

Countries with the largest gross domestic product (GDP) 2024

The 20 countries with the largest gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2029

Russia: Gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices from 1997 to 2029 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Russia: Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in current prices from 1997 to 2029 (in U.S. dollars)

Russia: Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate from 2019 to 2029 (compared to the previous year)

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia quarterly 2018-2024

Russia: Growth of the real gross domestic product (GDP) from 1st quarter 2018 to 1st quarter 2024 (compared to the same quarter of the previous year)

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia monthly 2019-2024

Year-over-year gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in Russia from January 2019 to January 2024

Value added by selected industries as a GDP share in Russia 2023

Share of gross value added in the gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia in 2023, by industry

Oil and gas sector as a share of GDP in Russia quarterly 2017-2023

Share of the oil and gas industry in the gross domestic product (GDP) of Russia from 1st quarter 2017 to 2nd quarter 2023

Government finances

- Basic Statistic Government expenditure relative to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2029

- Basic Statistic National debt in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2029

- Premium Statistic National debt in Russia 2011-2023

- Premium Statistic External debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2013-2022

- Basic Statistic Federal budget income and spending in Russia 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Budget balance in Russia quarterly 2016-2023

- Premium Statistic Oil and gas revenue share in consolidated budget in Russia 2023-2026

Government expenditure relative to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2029

Russia: Ratio of government expenditure to gross domestic product (GDP) from 2019 to 2029

National debt in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2029

Russia: National debt in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) from 2019 to 2029

National debt in Russia from January 2011 to July 2023 (in billion Russian rubles)

External debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia 2013-2022

Foreign debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio in Russia from 2013 to 2022

Federal budget income and spending in Russia 2014-2023

Income and expenditure of the federal budget of Russia from 2014 to 2023 (in trillion Russian rubles)

Budget balance in Russia quarterly 2016-2023

Budget balance (surplus or deficit) in Russia from 1st quarter 2016 to 2nd quarter 2023 (in billion Russian rubles)

Oil and gas revenue share in consolidated budget in Russia 2023-2026

Forecast share of oil and gas revenue in the federal budget in Russia from 2023 to 2026

Employment & wages

- Basic Statistic Unemployment rate in Russia monthly 2020-2024

- Basic Statistic Unemployment rate in Russia quarterly 2019-2024, by region

- Basic Statistic Youth unemployment rate in Russia in 2023

- Premium Statistic Monthly minimum wage in Russia and its major cities 2024

- Premium Statistic Average nominal wage per month in Russia 1995-2023

Russia: Unemployment rate from September 2020 to January 2024

Unemployment rate in Russia quarterly 2019-2024, by region

Average unemployment rate in Russia from 3rd quarter 2019 to 2nd quarter 2024, by federal district

Youth unemployment rate in Russia in 2023

Russia: Youth unemployment rate from 2004 to 2023

Monthly minimum wage in Russia and its major cities 2024

Monthly minimum wage in Russia and its largest cities as of January 1, 2024 (in Russian rubles)

Average monthly nominal wage in Russia from 1995 to 2023 (in Russian rubles)

Inflation and CPI

- Basic Statistic Inflation rate in Russia 2029

- Basic Statistic Monthly inflation rate in Russia 2022-2024

- Basic Statistic Year-over-year inflation rate in Russia in December 2012-2023

- Premium Statistic Inflation rate in Russia quarterly 2005-2024

- Premium Statistic Average food prices in Russia 2013-2022, by product

- Premium Statistic Industrial sector PPI in Russia 2023, by economic activity

Inflation rate in Russia 2029

Russia: Inflation rate from 1997 to 2029 (compared to the previous year)

Russia: Inflation rate from April 2022 to April 2024 (compared to the same month of the previous year)

Year-over-year inflation rate in Russia in December 2012-2023

Inflation rate in Russia from December 2012 to December 2023 (compared to December of the previous year)

Inflation rate in Russia quarterly 2005-2024

Year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Russia from 1st quarter 2005 to 1st quarter 2024

Average food prices in Russia 2013-2022, by product

Average consumer price of selected food products in Russia from 2013 to 2022 (in Russian rubles)

Industrial sector PPI in Russia 2023, by economic activity

Year-over-year Producer Price Index (PPI) in Russia in September 2023, by industrial sector (compared to the corresponding period of the previous year)

Income & expenditure

- Premium Statistic Average monthly income per capita in Russia 1995-2023

- Premium Statistic Real disposable income growth in Russia 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Disposable income distribution in Russia 2022, by spending and savings

- Premium Statistic Population income level distribution in Russia 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Population share in Russia 2013-2023, by monthly per capita income

- Basic Statistic Population under the poverty line in Russia 1995-2023

Average monthly income per capita in Russia 1995-2023

Average monthly income per capita in Russia from 1995 to 2023 (in Russian rubles)

Real disposable income growth in Russia 2014-2023

Year-over-year real disposable income growth of the population in Russia from 2014 to 2023

Disposable income distribution in Russia 2022, by spending and savings

Distribution of disposable population income in Russia in 2022, by expenditure and savings

Population income level distribution in Russia 2014-2023

Total monetary income distribution in Russia from 2014 to 2023, by 20-percent population group

Population share in Russia 2013-2023, by monthly per capita income

Population distribution by average monthly per capita money income in Russia from 2013 to 2023

Population under the poverty line in Russia 1995-2023

Population with an income below the subsistence minimum in Russia from 1995 to 2023 (in millions)

Industrial production

- Premium Statistic Russia: industrial production index 2014-2023

- Basic Statistic Manufacturing PMI in Russia monthly 2020-2023

- Basic Statistic Goods and services output index in Russia 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Industrial production value in Russia 2016-2022, by sector

- Premium Statistic Manufacturing production value in Russia 2022, by product category

Russia: industrial production index 2014-2023

Year-over-year industrial production index (IPI) in Russia from 2014 to 2023

Manufacturing PMI in Russia monthly 2020-2023

Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) for manufacturing in Russia from January 2020 to July 2023

Goods and services output index in Russia 2015-2022

Index of output of goods and services in Russia from 2015 to 2022

Industrial production value in Russia 2016-2022, by sector

Value of shipped own produced goods, works performed, and services rendered in Russia from 2016 to 2022, by economic sector (in trillion Russian rubles)

Manufacturing production value in Russia 2022, by product category

Value of shipped own produced goods, works performed, and services rendered by the manufacturing industry in Russia in 2022, by product category (in billion Russian rubles)

Business enterprise

- Premium Statistic Number of newly registered businesses in Russia 2014-2029

- Basic Statistic Legal entity count in Russia 2015-2024

- Basic Statistic Legal entity distribution in Russia 2024, by industry

- Basic Statistic Individual entrepreneur count in Russia 2015-2024

- Basic Statistic Russia Small Business Index (RSBI) monthly 2020-2024

- Premium Statistic Most profitable companies in Russia 2021

Number of newly registered businesses in Russia 2014-2029

Number of newly registered businesses in Russia from 2014 to 2029 (in thousands)

Legal entity count in Russia 2015-2024

Number of legal entities in Russia from 2015 to 2024 (in millions)

Legal entity distribution in Russia 2024, by industry

Share of legal entities in Russia as of 2024, by economic sector

Individual entrepreneur count in Russia 2015-2024

Number of individual entrepreneurs in Russia from 2015 to 2024 (in millions)

Russia Small Business Index (RSBI) monthly 2020-2024

Russia Small Business Index (RSBI) from January 2020 to June 2024

Most profitable companies in Russia 2021

Leading companies in Russia in 2021, by net profit (in billion Russian rubles)

Foreign trade

- Premium Statistic External merchandise trade value in Russia 2012-2023

- Premium Statistic Leading export partners of Russia 2022, by value

- Premium Statistic Commodity structure of exports in Russia January 2024

- Premium Statistic Leading import partners of Russia 2022, by value

- Premium Statistic Commodity structure of imports in Russia January 2024

External merchandise trade value in Russia 2012-2023

Merchandise export and import value and trade balance in Russia from 2012 to 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Leading export partners of Russia 2022, by value

Export value of goods from Russia in 2022, by major country of destination (in billion U.S. dollars)

Commodity structure of exports in Russia January 2024

Export value distribution in Russia in January 2024, by commodity

Leading import partners of Russia 2022, by value

Import value of goods in Russia in 2022, by major country of origin (in billion U.S. dollars)

Commodity structure of imports in Russia January 2024

Import value distribution in Russia in January 2024, by commodity

Further indicators

- Premium Statistic Gross national income (GNI) in Russia 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Inward flows of FDI in Russia 2011-2022

- Basic Statistic Labor productivity index in Russia 2022, by industry

- Premium Statistic Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) in Russia monthly 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Human development index of Russia 1990-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S. dollar & euro to Russian ruble exchange rate monthly 2008-2024

Gross national income (GNI) in Russia 2014-2023

Annual gross national income (GNI) volume in Russia from 2014 to 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Inward flows of FDI in Russia 2011-2022

Value of foreign direct investment (FDI) inward flows in Russia from 2011 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Labor productivity index in Russia 2022, by industry

Labor productivity index in Russia in 2022, by industry

Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) in Russia monthly 2014-2023

Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) in Russia from January 2014 to May 2023 (long-term average = 100)

Human development index of Russia 1990-2022

Human development index score of Russia from 1990 to 2022

U.S. dollar & euro to Russian ruble exchange rate monthly 2008-2024

Average monthly U.S. dollar (USD) and euro (EUR) exchange rate to Russian ruble (RUB) from January 2008 to June 2024

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Global economic indicators

- Coronavirus: impact on the global economy

- European economy

- Economic impact of the Russia-Ukraine war

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

U.S. Department of the Treasury