How to Cope with a Problematic PhD Supervisor

- by James Hayton, PhD

- January 17th, 2022

Need help? Book a free introductory session

Why you (probably) shouldn’t do a phd, “i can’t contact my phd supervisor until i have something to show”.

“Is there any system that protects PhD candidates from having a problematic supervisor? For example, any ways to make complaints? Or would complaints not help but make the relationship worse?”

The simple answer is yes, usually there are ways to make formal complaints.

My view is that universities and supervisors have a responsibility to provide support, feedback and guidance to PhD students. There’s a trust that you place in them when you invest years of your life and possibly quite a lot of money in tuition fees, and they have a duty to provide adequate support in return.

If you’re not receiving that support, you’ve got to be assertive . You’ve got to speak up, and you’ve got to speak up early while there’s still time to find a potential solution rather than waiting until the last few months of your PhD when it might be too late.

If you don’t say anything because you’re afraid of their reaction, there will probably be much worse consequences later.

However, as you rightly point out, making a formal complaint to the university or to your department is likely to affect your relationship with your supervisor.

I think that it’s always best to try to resolve any issues directly with your supervisor, and formal complaints should really only be used as a last resort if you’ve made every reasonable attempt to sort things out, but the working relationship has completely broken down. At that point, it doesn’t really matter how they react because the relationship is already dead.

So how should you try to address problems in your relationship with your PhD supervisor?

The original question doesn’t specify what the problem is, so I’ll go through a few common issues and how you might be able to approach them.

Problem 1: A lack of contact

The first common problem is simply a lack of contact. This is especially common if you’re doing a PhD remotely and you’re entirely dependent on email for communication.

Sometimes this isn’t entirely the supervisor’s fault. Often I speak to students who say they emailed the supervisor three months ago but didn’t get a reply. They can then get stuck in a cycle of worry about whether the supervisor cares about the project or whether the work they sent was good enough.

But then when I ask if they’ve tried to follow up, often they say they’re afraid of appearing rude, or they don’t want to disturb their supervisor because they’re so busy and important.

But remember that academics struggle too. The day your email arrived, maybe they had 100 other emails in their inbox. Maybe they had a grant application deadline. Maybe they were about to reply and someone knocked on their door. And maybe they fully intended to get back to you and because they wanted to give you a considered reply they didn’t do it in the moment and then it slid further down their inbox.

Personally, I try to stay on top of my email, but sometimes things slip. It doesn’t mean anything that I haven’t replied, and It’s helpful to me if you follow up on a message I haven’t replied to.

So try not to project your fears onto your supervisor. Assume good intentions and just send a polite follow up.

If they consistently don’t reply, then yes, that’s a problem. What I would do is say that you would really value their input and whether it would be possible to have more frequent contact, whether there’s something you can do to make that easier… and if there’s still no response or if they say no or if they get angry, this is when you might consider trying to change supervisor.

Problem 2: Multiple supervisors & contradictory advice

You might have more than one supervisor. Maybe they aren’t communicating with each other or maybe they are giving you contradictory advice.

In this case it’s your responsibility to manage the communication, making sure that they are both copied into emails, and they each know what the other has said.

It’s also worth noting that, often, supervisors are giving you suggestions and it’s up to you to decide what to do with them. They will want you to have counter-suggestions, they will want you to have your own ideas and they will want you to make decisions.

So instead of seeing it as contradictory advice, maybe try to see it as a range of options that you can try, or even modify to come up with another option of your own

Then in your communication with both supervisors, you can say what you’re going to try first.

Problem 3: Harsh feedback

What if your supervisor keeps giving you overly harsh feedback ?

This can be difficult to take, especially if you’ve put a lot of work in and if you’re feeling a bit stressed. So there’s an emotional component that can sometimes affect the way you interpret feedback and it can make you feel demotivated and disengaged.

When you were an undergraduate and you submitted an essay you probably just received a grade and moved on. You weren’t expected to make any changes. But at PhD level, you’re learning to be a professional academic. And when professional academics submit a paper—unless they submit to a low quality journal that accepts anything—there will almost always be things they have to change in response to the reviewers comments.

That’s actually a good result, because a lot of the best journals completely reject the majority of submissions. So I can guarantee that your supervisor, no matter how good their publication record, will have had work rejected and they will have had harsh feedback. It’s not a personal judgement, It’s just part of the job and it’s necessary to improve your work and your writing.

What I’d suggest is really engaging with the feedback, possibly just one section at a time to make it a little bit easier, and making sure you really understand the points they’re making and asking them questions to clarify if necessary.

One of the biggest frustrations I hear from PhD supervisors is students not saying anything. Most supervisors would want you to ask questions, they would want you to tell them if there’s something you don’t understand and they would want you to discuss a point you disagree with.

So try to become an active participant in your feedback, rather than a passive recipient.

For more on this point, check out my video on dealing with harsh feedback .

What makes a good PhD supervisor?

Stay up to date

I offer one to one coaching in academic writing. Click below to learn more and book your introductory session.

share this with someone who needs it:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Current ye@r *

Leave this field empty

PhD: An uncommon guide to research, writing & PhD life

By james hayton (2015).

PhD: an uncommon guide to research, writing & PhD life is your essential guide to the basic principles every PhD student needs to know.

Applicable to virtually any field of study, it covers everything from finding a research topic, getting to grips with the literature, planning and executing research and coping with the inevitable problems that arise, through to writing, submitting and successfully defending your thesis.

Useful links

About james hayton, phd, latest phd tips, academic writing coaching.

AI-free zone

All the text on this site (and every word of every video script) is written by me, personally, because I enjoy writing. I enjoy the challenges of thinking deeply and finding the right words to express my ideas. I do not advocate for the use of AI in academic research and writing, except for very limited use cases.

Why you shouldn't rely on AI for PhD research and writing

The false promise of AI for PhD research

Meta Gorup, Melissa Laufer

When relationships between supervisors and doctoral researchers go wrong.

Doctoral researchers represent a crucial group within the academic workforce. They importantly contribute to their departments’ and universities’ research efforts by, among other, carrying out data collection, running experiments, helping with or leading publication writing, presenting at conferences, and sometimes applying for research funding.

In 2018, doctoral programs across OECD countries enrolled over a million and a half doctoral students and granted a total of nearly 278,000 PhD or equivalent degrees (OECD n.d.).

However, this large, vital group of researchers faces numerous challenges connected to managing a several-years-long research project while learning a host of new skills and coming to terms with the unwritten rules of academia. It is thus perhaps not unexpected – although rarely openly talked about – that around 50 percent of doctoral researchers discontinue their doctorates (Council of Graduate Schools 2008; Groenvynck et al. 2013; Vassil and Solvak 2012).

In this blog post, we explore what is behind this worrying statistic. Specifically, we examine the role the relationship between doctoral supervisors and their students plays in the latter’s decision to discontinue their doctorates.

Melissa Laufer

We first shed light on the existing research pointing to the crucial role of supervisors in and their control over students’ doctoral journeys . Furthermore, we demonstrate that supervision-related issues are a common concern among PhD students. We then show that doctoral researchers’ problems with supervisors are often exacerbated by an institutional environment which discourages PhD students from addressing these issues.

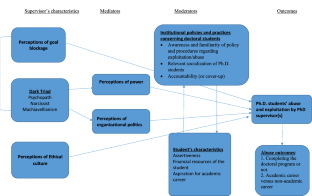

The remainder of the text presents our own study of international doctoral student dropout , revealing patterns of ‘control’ and abuse thereof by doctoral supervisors which in several cases played a decisive role in the PhD students’ decision to discontinue. Drawing upon the empirics of our study, we explore:

- How is control exercised and abused within relationships between doctoral supervisors and their students?

- What happens when PhD students challenge this control?

- And how do we break free of this cycle of control?

Supervisors Play a Central Role

While the reasons for a doctoral researcher’s decision to discontinue their doctoral studies are multifaceted – from personal and family issues to departmental and disciplinary cultures (Gardner 2009; Golde 2005; Leijen et al. 2016) – issues with supervisors often contribute to a doctoral student’s decision to discontinue their PhD (Gardner 2009; Golde 2005; Jones 2013; Leijen et al. 2016).

This is hardly surprising since, to a doctoral student, their supervisor is commonly “the central and most powerful person” who controls many crucial aspects of the PhD trajectory: the doctoral researcher’s integration into the academic community and discipline, the topic and process of their dissertation research, their career path following the doctorate (Lovitts 2001: 131), and sometimes the PhD students’ funding (Golde 2005; Laufer & Gorup 2019).

Doctoral Supervision Needs Improvement

The essential role of doctoral supervisors in the PhD students’ experience and success makes the statistics that report on persistent supervisory issues all the more worrisome.

A global survey of over 6,300 PhD researchers initiated by Nature found that doctoral researchers based in Europe were very likely to list “impact of poor supervisor relationship” as one of their top five concerns (Lauchlan 2019). In the UK, a study of over 50,000 postgraduate research students – which included both PhD-level and research master’s students – found that 38 percent of respondents listed “learning and support” as an area in need of improvement, and out of those, 46 percent referred to various supervision-related is sues (Williams 2019).

What is more, the previously mentioned Nature survey found that 21 percent of respondents experienced being bullied. Among those, 48 percent listed their supervisors as the most frequent perpetrators of bu llying (Lauchlan 2019)

A Disempowering Institutional Environment

What further hinders those doctoral researchers who experience difficulties with their supervisors is an institutional environment which disempowers them to proactively address their situations. Because PhD students “are in a subordinate and dependent position socially, intellectually, and financially,” they are unlikely to challenge those superior to them (Lovitts 2001: 34–35).

Studies report that doctoral students “fear” raising an issue to or about a supervisor (Metcalfe et al. 2018) and are plagued by “fear of repercussions” because they cannot address their concerns anonymously (Lauchlan 2019). At the same time, universities are generally seen as reluctant to address supervision-related problems (Metcalfe et al. 2018) and academics tend to place the blame on PhD researchers for their issues rather than on the doctoral program or the university (Gardner 2009; Lovitts 2001).

To this point, a survey of almost 2,500 doctoral researchers at the Max Planck Society in Germany reports that only half of doctoral students who experienced conflicts with those senior to them reported the conflicts to an institutional body. Among those who did, over 50 percent indicated the reports were not dealt with in a satisfactory manner (Max Planck PhDnet Survey Group 2020).

The International Doctoral Student Experience

One group of PhD researchers particularly vulnerable to the extreme challenges of the doctorate is international doctoral students (IDSs). They are required not only to adjust to a new academic system but also to a new society (Le & Gardner 2010; Campbell 2015; Cotterall 2015).

I DSs make up 22 percent of doctoral enro llments across OECD countries (OECD 2020), with their dropout rates comparable to local students, at circa 50 percent (Groenvynck et al. 2013). However, despite similarities in discontinuation rates, studies point out that IDSs are especially susceptible to disempowerment .

They are more inclined to experience issues with their su pervisors (Adams and Cargill 2003; Adrian-Taylor et al. 2007; Campbell 2015) and may encounter discrimin ation (Mayuzumi et al. 2007). The previously mentioned Max Planck Society survey (2020) for instance found that non-Germans were exposed to more bullying from supervisors than their German colleagues, with doctoral researchers coming from outside the European Union experiencing the most cases at 15 percent.

A Study of International Doctoral Student Dropout

Our 2019 study, The Invisible Others: Stories of International Doctoral Student Dropout , also highlights the vulnerability of IDSs. Specifically, it demonstrates how their statuses as cultural outsiders and academic novices contributed to their disempowerment and the eventual discontinuation of their studies.

We conducted in-depth life story interviews with 11 IDSs who had discontinued their doctorates at a Western European university. Across their narratives, we identified a pattern of ‘control’ that was exercised, and in some cases abused, by those in positions of power as well as institutionalized within the university structure.

Moreover, eight out of 11 participants described how issues with their supervisors to a greater or lesser degree prompted them to discontinue their doctorates .

Supervisors Controlling the Academic Conversation

Below we look at a selection of a broad spectrum of aspects in which supervisors exercised control over their IDSs’ doctoral journeys and show how the scale of power regularly tipped in the favor of supervisors.

Problematic Feedback and Mentorship Practices

Nearly all the IDSs reported some level of dissatisfaction with their supervisors’ feedback and support practices, with some explicitly pointing to supervisors’ control over their progress, learning and even future career.

Some IDSs explained, for example, that it was difficult to get any time at all with their supervisors, in some instances also sharing that this was not a challenge for local students. One PhD student described how they – as internationals – were “ all on our own completely, since the very beginning .”

One participant reported how the feedback he received largely focused on pointing out deficiencies and how he was not given opportunities to engage in dialogue about his work. This made him feel that the comments were delivered from the supervisors’ “ clearly defined position of power .” Similarly, another IDS explained how he felt he was “ not learning anything because I’m doing all that she’s [the supervisor] saying .”

For one research participant, the extent of his supervisor’s control explicitly extended to his future career. Initially, the supervisor agreed with the PhD student’s choice to discontinue and offered to write recommendation letters for his doctorate applications elsewhere. However, our interviewee later found out that his supervisor told a potential employer that he was not actually interested in pursuing a PhD.

Struggles Over the Ownership of the Research Project

A number of IDSs also felt their research projects were largely controlled by supervisors who did not give them the freedom to choose their research topic or decide how to approach it.

One doctoral researcher described how he felt that the “ research project doesn’t belong to me ,” together with feelings of “ working for someone else .” Another IDS shared that she was successful in winning an external grant which was supposed to give her the freedom to choose her research topic. However, in reality, she “ couldn’t make any decisions [about] my own work ”.

Some IDSs also reported the supervisors’ micro-management and lack of trust in them. One research participant explained how her supervisor

was completely behind my back, all the time. Like if I was coming in from an experiment, he would be like, what are the results? … He was all the time behind me and there was no trust in what I was doing, I was surveilled all the time.

This doctoral student was not alone in experiencing a constant pressure to perform and feeling surveilled. One IDS even shared he thought his supervisor “feels like she owns a person.”

Funding in Supervisors’ Hands

Another aspect where the supervisors’ power abuse was very apparent was finances, likely more so because at the case study university, supervisors were in large part directly in control of the PhD students’ funding.

Some IDSs reported how they were promised funding for a full PhD of four to five years, but were told after a year or two that their contract would not be extended. One research participant shared:

during the job interview on Skype and on site I have been told that there was funding for a PhD. That they would make a contract until the end of the first year, at the same time I would apply for an external grant … but not to worry because there was the funding for the entire project. … Which turned out not to be true.

In a couple of cases, doctoral researchers were offered only short-term contracts – of a few months – after their initial one or two-year contract expired. One research participant described what his supervisor did when she perceived at the end of his first two-year contract that he might not be able to finish his PhD:

she [supervisor] told me that she was only going to sign my contract for three months. … So that will give me like the added pressure and should be like a testing time, if I was going to be able to finish my PhD.

Following an evaluation after the first three months, the supervisor planned to continue extending this IDS’s contract every three months rather than offer him a longer-term contract.

Supervisors Using the PhD Students’ Status as Internationals

For IDSs coming from outside the European Union (EU), the supervisors’ control over their funding was also linked to the control over the PhD students’ immigration status. To stay in an EU country, non-EU students need to prove they have financial means to do so – and if their contract ends, that is put at risk.

One research participant shared how his supervisor explicitly referred to her control over his stay in the country:

she [supervisor] told me if I didn’t meet … all the deadlines that she had made for this project … she wouldn’t sign my contract and … that would put my residence here in [the country] and in Europe at risk, if I didn’t do exactly what she said. So that was openly like a threat. … so I think she used that. I mean … like a point of power, like … your stay here [in this country] relies on me.

Another narrative underlying some of our interviewees’ accounts was their perception that IDSs were more vulnerable to exploitation by their supervisors. One interviewee explained that he was “ an easy target for her [supervisor] ” because “ [s]he thought it doesn’t matter how bad she treats me or any other international students. ” He speculated that this group of PhD students was less likely to discontinue their doctorates because it was more difficult for them to find another opportunity in a country away from home. Thus, they were likely to put up with more mistreatment than their local counterparts.

Challenging Supervisors’ Control

As the previous examples illustrate, supervisors exercised and abused their control in various aspects of the PhD students’ lives. Although in most cases, doctoral students were aware of this control and openly spoke about it, it also seemed to be understood that there was little they could do to counter it. In the words of one IDS, “ nobody ever dared to talk to the professors .”

Those who brought up issues to their supervisors were often disappointed and disillusioned with the results. Some IDSs reported that challenging their supervisors resulted in the supervisors becoming furious, storming out of the room or threatening the PhD student with no contract renewal.

Another problem identified by our research participants was that there was simply not enough oversight of what was actually going on behind the scenes. An IDS shared,

apparently I was one of the many who had been quitting in this lab, which is strange because I thought, come on, there has to be some kind of follow-up on this … In the same lab, you have all these students quitting, don’t you think you have a problem? With this group?

At the same time, this PhD researcher seemed resigned to the situation. When asked if she had officially approached anyone about her issues, she responded,

I didn’t because who’s my reference? … I mean what is going to change, really, you know? I didn’t see it was going to help me out. Or who to go to, to begin with.

This notion that professors were somehow ‘untouchable’ was echoed in a number of doctoral researchers’ accounts. As a result, in relation to issues with their supervisors, only two of our interviewees used official university resources such as filing an official complaint with the faculty ombudsman or speaking to the internationalization office.

Moreover, these university resources did little to help the PhD students who approached them. One IDS who got in touch with the internationalization office and the office overseeing her scholarship was told they could not help her because “ this is quite a [personality] problem. So it’s not very academic. So they can’t really interfere .”

Another doctoral student shared how the faculty ombudsman dismissed and joked about his complaints when his supervisor offered him a series of short-term contracts in place of a longer one. Moreover, the intervention had no effect on the supervisor and his supervisor later explained to the PhD student that this practice was legal – and therefore acceptable.

Breaking the Cycle of Control

In the doctoral researchers’ accounts above, we see how supervisors, due to their seniority and institutionalized positions of power, may exercise and abuse their control over various aspects of the doctoral journey. For a number of our interviewees, this abuse was made worse due to their international status .

The fact that supervisors have the power to undertake the actions like those we illustrate above with limited to no consequences speaks to a much larger issue. We are no longer talking about a few bad apples in the barrel, but a systematic problem occurring across academia , as evident from the abovementioned surveys initiated by Nature (Lauchlan 2019) and the Max Planck Society (Max Planck PhDnet Survey Group 2020).

But this cycle of power imbalance does not need to continue. The change begins by rethinking how we characterize the doctorate. In academia folklore, the doctorate is often fashioned as a trial, a time of enormous hardship, of which only the fittest survive – but not without battle scars. Instead of seeing the doctorate as a grueling rite of passage, we need to shift our focus to building confident, empowered scholars , who value collaboration over competition.

Such change can be sparked by focusing on practices embedded within the institutional environment. In our practitioner-geared publication, Pathways to Practice: Supporting International Doctoral Students , we discuss in detail the small and larger steps institutions, supervisors and (international) doctoral students can take to create an inclusive doctoral experience for both international and local PhD students.

In this blog post, we would like to highlight two steps university stakeholders can take to ensure a more empowering institutional environment:

- We encourage institutions to set up training for supervisor s to reflect on their supervision styles and the assumptions embedded within them. Supervisors should also gain insight into giving constructive feedback and building professional partnerships with PhD students.

- We propose a number of formal and informal support structures institutions may make available to doctoral students, ranging from setting up an independent ombudsperson to forming peer and collegial support communities, such as study groups, workshops and online forums.

However, the concerns we raise in this blog post about power imbalances in the relationship between doctoral supervisors and their students are symptomatic of a phenomenon occurring across all levels of academia: the privileged few have power over the subordinate majority. Consequently, the larger question at stake is: how do we change deeply ingrained behaviors in academia that perpetuate inequalities?

Some of these issues are complex and may require a system-level overhaul, but others are within our reach. The relatively simple change actions we propose above can be a good starting point for how we want to shape the next generation of scholars. Let us begin by bringing the discussion of power abuse in academia into the light and, step by step, empower doctoral students, supervisors and institutions to break free of the cycle of control .

Author info

Meta Gorup is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Higher Education Governance Ghent at Ghent University in Belgium. Her research explores topics in research management and doctoral education through the lens of university members’ identities and university cultures.

Melissa Laufer is a senior researcher in the research programme “Knowledge &; Society” at the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. She is interested in investigating change processes at universities.

Digital Object Identifier (DOI)

Gorup, M., Laufer, M. (2020). More Than a Case of a Few Bad Apples: When Relationships Between Supervisors and Doctoral Researchers Go Wrong. Elephant in the Lab . DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4213175

Collapse references

Adams, K., & Cargill, M. (2003). Knowing that the other knows: using experience and reflection to enhance communication in cross-cultural postgraduate supervisory relationships. Christchurch: paper presented at Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia Conference.

Adrian-Taylor, S. R., Noels, K. A., & Tischler, K. (2007). Conflict between international graduate students and faculty supervisors: toward effective conflict prevention and management strategies. Journal of Studies in International Education , 11 (1), 90–117.

Campbell, T. A. (2015). A phenomenological study on international doctoral students’ acculturation experiences at a US university. Journal of International Students , 5 (3), 285–299.

Cotterall, S. (2015). The rich get richer: international doctoral candidates and scholarly identity. Innovations in Education and Teaching International , 52 (4), 360–370.

Council of Graduate Schools. (2008). Ph.D. completion and attrition: analysis of baseline demographic data from the Ph.D. Completion Project. Washington D.C.: Council of Graduate Schools.

Gardner, S. K. (2009). Student and faculty attributions of attrition in high and low-completing doctoral programs in the United States. Higher Education , 58 (1), 97–112.

Golde, C. M. (2005). The role of the department and discipline in doctoral student attrition: lessons from four departments. The Journal of Higher Education , 76 (6), 669–700.

Groenvynck, H., Vandevelde, K., & Van Rossem, R. (2013). The PhD track: who succeeds, who drops out? Research Evaluation , 22 (4), 199–209.

Jones, M. (2013). Issues in doctoral studies – forty years of journal discussion: where have we been and where are we going? International Journal of Doctoral Studies , 8 (6), 83–104.

Lauchlan, E. (2019). Nature PhD survey 2019. London: Shift Learning. Available on: https://figshare.com/s/74a5ea79d76ad66a8af8 Last accessed on 22 October 2020.

Laufer, M., & Gorup, M. (2020). Pathways to practice: supporting international doctoral students. Amsterdam: EAIE. Available on: https://www.eaie.org/our-resources/library/publication/Pathways-to-practice/pathways-to-practice-supporting-international-doctoral-students.html Last accessed on 22 October 2020.

Laufer, M., & Gorup, M. (2019). The invisible Others: stories of international doctoral student dropout. Higher Education , 78 (1), 165–181.

Le, T., & Gardner, S. K. (2010). Understanding the doctoral experience of Asian international students in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields: an exploration of one institutional context. Journal of College Student Development , 51 (3), 252–264.

Leijen, Ä., Lepp, L., & Remmik, M. (2016). Why did I drop out? Former students’ recollections about their study process and factors related to leaving the doctoral studies. Studies in Continuing Education , 38 (2), 129–144.

Lovitts, B. E. (2001). Leaving the ivory tower: the causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study . Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Max Planck PhDnet Survey Group. (2020). Survey report 2019. Available on: https://www.phdnet.mpg.de/145345/PhDnet_Survey_Report_2019.pdf Last accessed on 22 October 2020.

Mayuzumi, K., Motobayashi, K., Nagayama, C., & Takeuchi, M. (2007). Transforming diversity in Canadian higher education: a dialogue of Japanese women graduate students. Teaching in Higher Education , 12 (5–6), 581–592.

Metcalfe, J., Wilson, S., & Levecque, K. (2018). Exploring wellbeing and mental health and associated support services for postgraduate researchers. Cambridge: Vitae. Available on: https://www.vitae.ac.uk/doing-research/wellbeing-and-mental-health/HEFCE-Report_Exploring-PGR-Mental-health-support/view Last accessed on 22 October 2020.

OECD. (n.d.). OECD.Stat: graduates by field. Available on: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EDU_GRAD_FIELD Last accessed on 22 October 2020.

OECD. (2020). Education at a glance 2020: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Vassil, K., & Solvak, M. (2012). When failing is the only option: explaining failure to finish PhDs in Estonia. Higher Education , 64 (4), 503–516.

Williams, S. (2019). Postgraduate research experience survey 2019. York: Advance HE. Available on: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/postgraduate-research-experience-survey-2019 Last accessed 22 October 2020.

There are so many issues with the quality and attitude of supervisers, in my view – at least in the UK system.

Some of the challenges that I experienced were:- 1) A supervisor who spent a lot of time telling me how certain people (and even a faculty member) – and he named names – had only got their PhDs because he had written their thesis for them, or built their experiemental equipment, run their clinical trials etc. He seemed to almost believe that the world did not turn without his assistance.

2) He regularly wanted to take-over and design or work-out sections for me. I kept telling him that I wanted it to be my work and that the only way I could learn was to do the work. I wanted to know that I had earned it, but he did not stop or respect that and it caused disagreement and bad feeling.

3) There was no help or understanding for the things I really needed his help with; a poor administration where my ID card/computer and library access kept beinng cancelled every three weeks for three years. A computer that could not cope with all I demanded of it and could not cope with the extensive calculations and graphics processing.

4) There was never any time or interest in discussing what I had learned or discovered during my work – I felt so cut-off and isolated. For me, the joy of a doctorate was learning something surprising and new. But this was lost, as I had no one to share it with.

5) His mood would either be over the top nice, where everything was wonderful – or utterly condemning and condescending, depending on the day. So during one meeting I might feel pleased with myself and during the next, for exactly the same points of discussion, suddenly my work was complete rubbish. So I could never trust or believe him either way and that left me feeling wary, on-edge and bewildered.

6) Many supervisors appear to have little understanding or concern for the university rules and purpose of supervising and just muddle along doing whatever they deem fit.

7) Many have long forgotten the struggles and loneliness of research at doctoral level and view students as cannon fodder.

8) When I tried to raise a complaint, they just closed ranks and ignored me. The only way to get them to address my supervisory issues was to go through the formal complaints process and ask for it to be looked at by another faculty. The result was them saying that they had added my supervisor to a “watch list” and they would have liked to get rid of him, but for legal reasons they could not. But they still let him supervise !

9) The university seemed to be split into a myriad of defensive islands that were at war with each other and no one really listened or helped. Whenever a problem arose, the standard practice seemed to be to refer the person to another group of department and then it turn, that group would deny responsibility and you would be passed somewhere else – and so it would go on. In my case, even writing an e-mail to the “President” (as Vice-chancellors like to call themselves now – how pretenious) and the VP Education got nowhere, as my complaint as bounced back to my faculty – who continued to ignore it. So what was the point of the falsely proclaimed “exceptional student experience” ?

10) Faculty like to think that they work really hard and I am sure some do – but my research group/faculty would disappear for two hour lunches and, on Fridays, never come back until Monday. My supervisor would often not turn-up for supervisory meetings and I would find him having coffee and hiding behind a broad-sheet newspaper in the nearby Costa Coffee.

11) The best part was when my supervisor recommended a comference for me – which I paid the fees, booked the flights etc for – only to discover that it did not exist and was a phoney/scam conference. When I complained, he claimed that I had not paid attention – fortunately, I kept a copy of his e-mail with the link he sent me to that supposed conference.

12) When I finally started with a new supervisor, he was upset because the reearch topic I had been given by the previous Professor was actually an area he had “taken” from my new Professor. So I was dragged into a long-standing, ‘silent’ war of mistrust between them.

13) There was an unspoken but firm ritual where other academics names might be added to a paper’s author list, even though they had no involvement – just to boost a colleague’s research profile.

The fundamental issue seems to me to be the lack of supervision of supervisors. It all seems to work on the principles of a gentlemen’s club, where – when something goes wrong – no one mentions or acknowledges it. The academic equivalent of a black hole could open-up and they would just walk around it and comment on how clear the sky was around there. SO bizarre..,…

Continue reading

What’s the Content of Fact-checks and Misinformation in Germany?

In this short analysis, Sami Nenno takes a closer look at the content of fact-checks and misinformation in Germany.

Do you dare? What female scientists expect when communicating

This short analysis focuses on female scientists as a subgroup of a large survey sample and how their assessment of public engagement differs from that of their male counterparts.

What happens to science when it communicates?

In August 2023 Benedikt Fecher conducted an interview with Clemens Blümel from the German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies (DZHW) on the topic of ‘what happens when science opens up and communicates’ and the emerging challenges for future scientific communication.

- Challenges that PhD Students Face

Written by Ben Taylor

What to expect in this guide

Navigating the journey of a PhD can be challenging, however, with the right strategies, you can turn these hurdles into stepping stones that lead towards a successful completion of your doctorate. Key points we cover in this guide:

- How to handle PhD supervisors who aren’t quite supporting you the way you need them to.

- The importance of seeking support and guidance from other academics and researchers.

- Strategies for maximising the benefits and outcomes of your PhD journey. .

PhD problems arise for almost every student. After all, the PhD is the culmination of your academic work to date and represents a substantial, complex research project. It's unlikely that you'll make it through an entire doctorate without facing at least a few obstacles.

It pays to understand some of the most common PhD struggles and pressures before you begin a doctorate, so that you’re better equipped to deal with them if they crop up in your own journey.

This page gives advice on tackling a range of PhD struggles, from dealing with a bad supervisor to the ‘second year blues’.

On this page

#1 signs of a bad phd supervisor.

The majority of supervisor-supervisee relationships are healthy, productive and mutually beneficial. Chances are you’ll find in your PhD supervisor someone who is an expert in their field and a dedicated mentor to you.

However, as with any other situation in life, there is a possibility that you might not get on with your supervisor. We’ve covered some common PhD supervisor problems below and suggested how you can go about solving them.

A lack of communication

Often the root of disagreement and difficulties between a supervisor and a PhD researcher is a lack of communication.

Ideally, you should discuss and agree on expectations in this area with your supervisor at the beginning of your PhD. But it’s never to late to address the subject if you don’t think these expectations are being met or if you’re worried that you’re not contacting your supervisor enough.

Showing that you have doubts or concerns about the progress of your PhD or asking for help aren’t signs of weakness, but a signal on your part that you want to succeed. These are a few pointers to think about when getting in touch with your supervisor

- Identify where you need training or help

- Share your concerns about where your project is and where it is going

- Ask about techniques, resources and recommended reading

You’ll be surprised what effective communication can achieve. You may find that your supervisor had no idea you were struggling (or, rather, that you are not struggling at all but experiencing the same emotions as most doctoral students).

However, you should be realistic with your demands and expectations. After all, supervisors are busy academics and researchers themselves, often juggling teaching, research, pastoral or administrative roles along with their duties as a supervisor.

PhD supervisors who don’t get back to you

Having stated the importance of communication, how do you reach out to someone who just doesn’t get back to you or respond to emails?

Perhaps the first step is to try and find out, without being indiscrete, why your supervisor is not available. Do they have research commitments abroad? Are they involved in senior-level work with your institution, the government, public organisations or industry? Are they part-time?

Next, you should arrange a meeting where you can discuss a pattern of contact times that would suit you both.

If your supervisor isn’t available because of the number of students they have responsibility for, try and find out how the other students deal with it.

Remember that in most cases you will have a second supervisor and they are there to help you. If you don’t have one, speak to your graduate school (or equivalent) and try to identify one, but keep your main supervisor informed.

Overbearing supervisors

Overbearing supervisors who look over your shoulder constantly can be as much a problem as absent supervisors.

Unfortunately, there aren’t many ways to deal with this other than to have a chat with them and (diplomatically!) explain that you would welcome taking a more leading role in planning and conducting your research. Gently let them know that meeting too frequently is counterproductive and you feel you have the skills and the enthusiasm to take your project forward.

Supervisors who leave

Thankfully, this doesn’t happen very often, Hopefully, if your supervisor is leaving, for whatever reason, you will get advance notice so that you can work together to make alternative supervisory arrangements.

- Retirement – It’s unlikely that someone will agree to be your supervisor if they know that they’ll be retiring soon. However, if you do find yourself in this situation, you should ask your supervisor what their retirement means for you. Will they still be able to supervise you? Are they discharging supervisory responsibility to other academics? If so, do you think it is okay? You could propose your own choice or ask your second supervisor if they can step up.

- Leaving for another university – You really have two choices here – go with them or stay and find another supervisor.

- Going on sabbatical – Ask whether they think they can offer an adequate level of supervision while on research leave (especially if they are abroad) or if you should look for an alternative supervisory structure.

Changing PhD supervisors

There are many reasons why you may be considering a change in supervisor, and not all of them have to do with a bad supervisor-supervisee relationship. For example, if your research has changed in scope considerably, it’s reasonable to think about having an additional supervisor or to switch completely. Your university will probably have a process in place for this.

Make sure you discuss your decision with your current supervisor – especially if the reasons are any of the issues discussed above – so that they know what went wrong.

You should also bear in mind that one of the main skills PhD students develop is self-reliance. Being able to work without constant supervision is a valuable attribute, so it might not be the end of the world if you have less frequent contact with your supervisor, or if you find that you need less and less advice.

Of course, depending on where you are in your PhD, a change of supervisor may be a disruption rather than a benefit. Don’t forget the old adage that the grass always looks greener on the other side...

What does a good relationship with your PhD supervisor look like?

Our guide has more information on what to expect from your PhD supervisor and how to maintain a healthy relationship with them.

#2 Being overworked

Teaching, tutoring and marking are often part of PhD training (especially in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences). However, it shouldn’t prevent you from doing your research. If you feel your workload is too high or that your supervisor is asking too much of you, it’s completely fine to say no to new tasks. While a certain amount of PhD pressure is to be expected, it shouldn’t negatively impact your mental health or contribute towards depression and anxiety.

A workload that seems reasonable in the first two years of your PhD may not be towards the end of your doctorate. If your supervisor is asking you to take on more (non-PhD) work, let them know that, while you welcome the opportunity to gain experience and new skills, you don’t want your PhD work to suffer as a result.

If you need a visa to study wherever you are, there are generally restrictions on the number of hours you can work (in the UK it’s 20 hours per week on a student visa ). Some funders have their own restrictions so make sure you are not in breach of your visa or your funding agreement.

#3 Isolation

The level of independence required by a PhD is a big step up from what students might have been used to during their undergraduate or Masters degrees. As a doctoral student, you’re expected to have a lot of autonomy, along with the ability to set and meet your own targets (as well as those of your supervisor).

While this sense of freedom can initially be very exciting, once you get into the daily routine of a PhD , you may begin to feel a sense of isolation – particularly if your research doesn’t necessitate much collaboration with others.

Getting involved in extra-curricular activities like academic conferences and teaching can be a good way of combatting loneliness and isolation, giving you the chance to meet other research students in a similar position to you.

#4 Loss of motivation

You need enthusiasm, optimism and dedication to do a PhD. It is a long project, probably more so than you expected. As with all things, your motivation will have highs and lows unless you find ways to keep things varied, interesting, realistic and rewarding. Also bear in mind that you are primarily doing your PhD for yourself. So, be proactive and don’t wait for someone to tell you what to do.

Yes, there will be time when it feels that nothing is going your way and that everything you do fails but don’t despair. Among the qualities you’ll develop as a PhD student are determination and a desire to succeed (both highly valued by employers too!). This is what will see you through.

It is normal to avoid tasks that are difficult or that you do not want to do. For example, looking at a blank page and imagining your completed thesis is one of the biggest challenges that you will face. However, a doctorate requires you to undertake such a variety of tasks that it is unlikely that you will find them all equally easy and interesting. You’ll find it much easier to set yourself some realistic goals and to break up tasks in smaller chunks.

#5 ‘Second year blues’

This is a well-known phenomenon. Following the initial high of being a PhD student and the enthusiasm of taking forward your beloved research project, your morale may slump, causing you to experience the ‘second-year’ blues. This happens to many students, but by year three you’ll be so busy trying to race to the end of your project and writing up that you won’t have time to think about it.

If you feel out of your depth and that you’re doing badly in your PhD, discuss it with your supervisor or someone in an advisory position. Are you really not up to the task? Or are you just lacking in self-confidence and actually suffering from impostor syndrome? It’s probably just a temporary period of uncertainty and loss of motivation.

Be aware of your own self-confidence levels and learn to recognise when your self-belief goes down so you can address it. Boost your confidence by seeking positive feedback (presenting your research at an academic conference can seem difficult but discussing your research with others in the same field is really rewarding), try new things or go on training courses and remind yourself what you are good at.

Dealing with PhD problems

The best strategy to solve any problem that arises during your PhD should begin by talking to someone about it (and the earlier the better). Best of all is to try and resolve things informally.

Top of the list is talking to your supervisor. If you don’t feel confident speaking to them directly, why not put it in writing? Not only will it be documented but it may be easier to order your thoughts and to put your point across. This can be particularly useful when dealing with PhD pressure.

Alternatively, if you feel that you can’t approach your supervisor, you can raise the issues at your next formal progress meeting or speak to the PhD programme director, another research colleague or fellow students.

In addition, remember that universities often have support services designed to help you such as:

- Counselling

- Student unions

- Career advisers

- Research development advisers

- International officers

The last resort, if you feel that you have exhausted all other avenues, is to start a formal complaint procedure , either through your university or through an external body such as the Office of the Independent Adjudicator for Higher Education.

Ready to do a PhD?

Search our project listings to find out what you could be studying.

Want More Updates & Advice?

Ben worked in the FindAPhD content team from 2017 to 2022, starting as an Assistant Content Writer and leaving as Student Content Manager. He focused on producing well-researched advice across a range of topics related to postgraduate study. Ben has a Bachelors degree in English Literature from the University of Sheffield and a Masters from the University of Amsterdam. Having also spent a semester at the University of Helsinki through the Erasmus programme, he’s no stranger to study abroad (or cold weather!).

What happens during a typical PhD, and when? We've summarised the main milestones of your PhD journey to show you how to get a PhD.

The PhD thesis is the most important part of a doctoral degree. This page will introduce you to what you need to know about the PhD dissertation.

This page will give you an idea of what to expect from your routine as a PhD student, explaining how your daily life will look at you progress through a doctoral degree.

PhD fees can vary based on subject, university and location. Use our guide to find out the PhD fees in the UK and other destinations, as well as doctoral living costs.

Our guide tells you everything about the application process for studying a PhD in the USA.

Postgraduate students in the UK are not eligible for the same funding as undergraduates or the free-hours entitlement for workers. So, what childcare support are postgraduate students eligible for?

FindAPhD. Copyright 2005-2024 All rights reserved.

Unknown ( change )

Have you got time to answer some quick questions about PhD study?

Select your nearest city

You haven’t completed your profile yet. To get the most out of FindAPhD, finish your profile and receive these benefits:

- Monthly chance to win one of ten £10 Amazon vouchers ; winners will be notified every month.*

- The latest PhD projects delivered straight to your inbox

- Access to our £6,000 scholarship competition

- Weekly newsletter with funding opportunities, research proposal tips and much more

- Early access to our physical and virtual postgraduate study fairs

Or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

*Offer only available for the duration of your active subscription, and subject to change. You MUST claim your prize within 72 hours, if not we will redraw.

Create your account

Looking to list your PhD opportunities? Log in here .

What to do if your doctoral supervisor is unresponsive or disengaged

Advice and recommendations on what steps to take if your doctoral supervisor is unresponsive or disengaged..

Every supervisory relationship is different so use your judgement to decide which steps to take, what the appropriate timescale is and what your personal approach should be.

Read this guide for additional information on what to expect from your doctoral supervision and how to make the most of it.

You may also wish to consider the Responsibilities of the Supervision Team as well as the Responsibilities of the Doctoral Student , both of which are appendices of QA7 which sets out the principles for doctoral study (including integrated PhDs and Professional Doctorates).

- For a short period (e.g. 1-2 weeks)

Check they are not on holiday or on leave; check their online calendar or ask close colleagues (e.g. other members of the supervision team, department support contact ).

Check whether their other doctoral students have heard from them.

Send a friendly email or message to check they are OK.

Ask yourself how urgent it is; does the matter require their immediate attention? If it is urgent, send an explicit email (highlight it is urgent by putting the word "urgent" in the heading of the email), go to their office or call.

- For a longer period (e.g. 3-4 weeks)

You might not want to wait this long before taking these actions if it is an urgent issue.

If it is non-urgent and they continue to not engage then you can:

Talk to a member of staff informally to ask for advice (e.g. other members of the supervision team, Doctoral College department support contact , Director of Doctoral Studies or someone else you trust). They may be able to give suggestions on how to proceed, or help broker the discussion.

Send a direct email requesting a quick response explaining why you need their input. Explain you are stuck and can’t make progress (be mindful they may have their own personal challenges of which you are unaware).

Ask for a meeting to discuss the process for future engagement. Set expectations - how do you want the relationship to work and what progress would you like to make?

If there is continued lack of engagement from your supervisor talk to the Director of Doctoral Studies or Head of Department. This is a more formal option as it is likely that the DoS or HoD would need to communicate with the supervisor in order to set expectations. Discussions will remain confidential and they may not need to be communicated directly to your supervisor.

- If the problem persists

If you find that it is often difficult to contact your supervisor(s) and you have tried resolving it using the above methods, you can confidentially report an issue affecting your research by accessing a link available in your six-monthly progress reports or by reporting an issue online . This link will connect you to a simple form that when completed can be routed via the Doctoral College to your Faculty/School Director of Doctoral Studies or the Academic Director of the Doctoral College, who will get in touch to discuss the issue in confidence.

If required, there is a formal process to change supervisor or raise a complaint:

- to change your Supervisor, complete PGR8

- student complaints policy and procedure

If issues are more serious or you would prefer some independent advice, then you can contact the following teams for advice and support:

- The Independent Advice Service for PGR students

- Student Support

- SU Advice and Support

Support for doctoral students

If you have any questions, please contact us.

Doctoral College support

On this page.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 10 December 2021

Managing up: how to communicate effectively with your PhD adviser

- Lluís Saló-Salgado 0 ,

- Angi Acocella 1 ,

- Ignacio Arzuaga García 2 ,

- Souha El Mousadik 3 &

- Augustine Zvinavashe 4

Lluís Saló-Salgado is a PhD candidate in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge. Twitter: @lluis_salo.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Angi Acocella is a PhD candidate in the Center for Transportation & Logistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. LinkedIn: @angi-acocella.

Ignacio Arzuaga García is a PhD student in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge. LinkedIn: @ignacioarzuaga.

Souha El Mousadik is a PhD student in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Augustine Zvinavashe is a PhD candidate in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

When you start a PhD, you also begin a professional relationship with your PhD adviser. This is an exciting moment: interacting with someone for whom you might well have great respect and admiration, but who might also slightly intimidate you.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-03703-z

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Related Articles

Why you need an agenda for meetings with your principal investigator

- Research management

I botched my poster presentation — how do I perform better next time?

Career Feature 27 SEP 24

Researchers in Hungary raise fears of brain drain after ‘body blow’ EU funding suspension

Career News 26 SEP 24

How I apply Indigenous wisdom to Western science and nurture Native American students

Career Q&A 25 SEP 24

Seven work–life balance tips from a part-time PhD student

Career Column 24 SEP 24

My identity was stolen by a predatory conference

Correspondence 17 SEP 24

More measures needed to ease funding competition in China

Correspondence 24 SEP 24

Gender inequity persists among journal chief editors

The human costs of the research-assessment culture

Career Feature 09 SEP 24

Postdoctoral Fellow in Biomedical Optics and Medical Physics

We seek skilled and enthusiastic candidates for Postdoctoral Fellow positions in the Biomedical Optical Imaging for cancer research.

Dallas, Texas (US)

UT Southwestern Medical Center, BIRTLab

Associate Professor

J. Craig Venter Institute is conducting a faculty search for Associate Professors position in Rockville, MD and San Diego, CA campuses.

Rockville, Maryland or San Diego, California

J. Craig Venter Institute

Associate Professor position (Tenure Track), Dept. of Computational & Systems Biology, U. Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Please apply by Dec. 2, 2024.

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh | DCSB

Assistant Professor

Assistant Professor position (Tenure Track), Dept. of Computational & Systems Biology, U. Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Please apply by Dec. 2, 2024.

Independent Group Leader Positions in Computational and/or Experimental Medical Systems Biology

NIMSB is recruiting up to 4 Independent Group Leaders in Computational and/or Experimental Medical Systems Biology

Greater Lisbon - Portugal

NOVA - NIMSB

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

“I didn’t want to be a troublemaker” – doctoral students’ experiences of change in supervisory arrangements

Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education

ISSN : 2398-4686

Article publication date: 4 October 2021

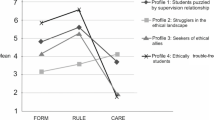

Issue publication date: 23 March 2022

During the lengthy process of PhD studies, supervisory changes commonly occur for several different reasons, but their most frequent trigger is a poor supervisory relationship. Even though a change in supervisors is a formal bureaucratic process and not least the students’ rights, in practice it can be experienced as challenging. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore how doctoral students experience a change in supervisory arrangements.

Design/methodology/approach

This study highlights the voices of 19 doctoral students who experienced at least one supervisory change during their doctoral studies.

The findings were structured chronologically, revealing the students’ experiences prior, during and after the changes. In total, 12 main themes were identified. Most of the interviewed students experienced the long decision-making processes as stressful, difficult and exhausting, sometimes causing a lack of mental well-being. However, once the change was complete, they felt renewed, energized and capable of continuing with their studies. It was common to go through more than one change in supervisory arrangements. Further, the students described both the advantages of making a change yet also the long-lasting consequences of this change that could affect them long after they had completed their PhD programs.

Originality/value

The study fulfills an identified need to investigate the understudied perspective of doctoral students in the context of change in supervisory arrangements. A change in the academic culture is needed to make any changes in supervisory arrangements more acceptable thus making PhD studies more sustainable.

- Thematic analysis

- Doctoral student

- Student experience

- Supervisory change

Schmidt, M. and Hansson, E. (2022), "“I didn’t want to be a troublemaker” – doctoral students’ experiences of change in supervisory arrangements", Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education , Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 54-73. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-02-2021-0011

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Manuela Schmidt and Erika Hansson.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

“Yes, I think a big lesson is that [change] does not have to be [so dramatic]. Okay, it was a bit dramatic [in my case], maybe, but really […] it doesn’t need to be that dramatic to change supervisors. It's just […] It's like just filling out a form. And I think it's important to understand as a doctoral student that it's actually one's right to change supervisors. You are allowed to do that. And I also think that many supervisors think that they are sitting on some kind of knowledge that no one else can convey, but in most cases, there are 20 other potential supervisors who are in line.” (interview 19)

PhD education is often compared to a journey, a roller coaster ride or even white water rafting (Schmidt and Umans, 2014 ; Christie et al. , 2008 ). Many different factors can influence a doctoral student’s experiences either positively or negatively and these experiences can change rapidly. On this journey, a student’s relationship with her/his supervisor is often singled out as the most important factor for the success of PhD studies. The supervisors and the relationship with them play a central role not only in the doctoral students’ outcomes such as degree of completion and attrition but also in the students’ overall experience and satisfaction with the program (Pyhältö et al. , 2015 ; Barnes et al. , 2010 ; Devos et al. , 2017 ). When the relationship between doctoral students and supervisors is experienced as something positive and empowering, the two parties are engaged in the process of mutual learning and the more academic seniors enable socialization and acculturation of the juniors into academic life and practices (Lee, 2020 ; Mendoza, 2007 ). However, the relationship with the supervisor may also have the potential to develop into something more negative, even to the extent that it might be experienced as destructive by the students. Negative relationships with the supervisors can be primarily explained by the expectation gap where the two parties might prioritize different things. For example, doctoral students might view social support from their supervisors and interaction with them to be the highest priority (Basturkmen et al. , 2014 ), while the supervisors might perceive the importance of financial resources and student characteristics such as motivation and an internal locus of control to be of the highest priority (Gardner, 2009 ).

Remaining in an “unhappy” supervisory relationship;

Quitting; and

Opting for a change in supervisors.

A limited number of studies focus on the choice to remain in an unhappy supervisory relationship (Barnes et al. , 2010 ; Kulikowski et al. , 2019 ; Al Makhamreh and Stockley, 2019 ; Owens et al. , 2020 ). Those studies usually focus on “overcoming” and emphasize doctoral students’ pride in succeeding despite negative experiences and supervisory problems (Bryan and Guccione, 2018 ). Most of the studies explore the second choice – quitting, which is also referred to as attrition. The interest in this choice may be particularly motivated by soaring attrition rates of up to 50% in PhD programs (Groenvynck et al. , 2013 ) and indications of many doctoral students considering quitting their PhD studies (Sowell et al. , 2008 ; Cornér et al. , 2017 ; Schmidt and Hansson, 2018 ) with a poor supervisory relationship being the primary reason (Jacks et al. , 1983 ).

Although supervision issues were considered the most researched topic in a review in 2018 (Sverdlik et al. , 2018 ), very few studies report on the third choice – change in supervisory arrangements and doctoral students’ experiences who make that choice (Wisker and Robinson, 2013 ; McAlpine et al. , 2012 ). These nascent studies describe doctoral students’ experiences of supervisory change in terms of confusion, rejections and traumatization. They suggest that the change adds to the students’ insecurities, decreases their well-being (Wisker and Robinson, 2013 ; McAlpine et al. , 2012 ) and has long lasting effects on their careers. According to Wisker and Robinson (2013) , further exploration of the topic from the doctoral students’ perspective is needed. This is important, as doctoral students’ negative experiences in the supervisory process in general and of a supervisory change in particular, might be fundamental in shaping the future roles that doctoral students will play in academia and society at large (Barnes et al. , 2010 ; Schmidt and Hansson, 2018 ).

Responsibilities, duties and supervisors and doctoral students’ expectations are often loosely defined or are lacking at the university level and differ between different national contexts (Barnett et al. , 2017 ). For example, in Sweden, the higher education ordinance (SFS, 1993 ), clearly regulates a change of supervisors and states it as a doctoral student’s right. Yet, in general, implementation of supervisory change remains to be an ambiguous process. This ambiguity could be one of the reasons that contribute to the negative experiences of supervisory change, often felt as some sort of failure by one or both parties involved (Wisker and Robinson, 2012 ; Wisker and Robinson, 2013 ). Even if both parties do not enter into supervisory relationships with anticipation to change, change in supervisory arrangements is common and happens for various reasons such as retirement, change of workplace or relocation of a supervisor or difficulties in supervisory relationships (Wisker and Robinson, 2012 ). Further, models of doctoral student supervision vary across countries and PhD programs (Paul et al. , 2014 ). Yet, most commonly discussed in the literature is co-supervision, also referred to as joint or team supervision. In this study, co-supervision implies supervision of one doctoral student by two or more supervisors, of which one is appointed as main or principal supervisor. Roles and responsibilities among supervisors might differ depending on supervisory constellation, can change over time and are often individually agreed on among the supervisors. A plethora of studies so far has focused on the concept of supervision, the nature of the relationship between doctoral students and supervisors and supervisors’ styles (Lee, 2020 ; Gatfield, 2005 ; Murphy et al. , 2007 ; Gurr, 2001 ). Yet, most of these studies focus on the supervisors’ perspective and shun discussing doctoral students’ experiences. Taking a rather positive view, these studies fail to consider that supervision itself might not be the solution for the issues experienced by the doctoral students, but instead can be a cause of the problems, thus overlooking students’ negative and damaging experiences of supervision (Wisker and Robinson, 2013 ).

With an increasing number of doctoral students entering tertiary education (The World Bank [Unesco Institute for Statistics], 2020 ; Shin et al. , 2018 ), this occupational group has been gaining more attention and rights. Given these gains, doctoral students have become increasingly demanding of their supervisors, expecting them to be trustworthy, good listeners, encouraging, having faith in the student and being knowledgeable and informative (Denicolo, 2004 ; Barnes et al. , 2010 ). Although these demands can be exhausting for supervisors, they can be explained by doctoral students feeling disoriented, being aware of their dependency position and stressed about juggling competing expectations and financing their studies. From the doctoral students’ perspective, to express dissatisfaction with a senior researcher remains to be a challenging and delicate matter due to dependency issues. However, despite the initial stress and negative emotions because of a change in supervisory arrangements, it may also represent the possibility of a new start (Wisker and Robinson, 2012 ). With increasing demands by employees for better work conditions in academia and elsewhere (Schmidt and Hansson, 2018 ; Dobre, 2013 ), doctoral students – mindful of their well-being – might be gradually more weary of remaining in poor supervisory relationships that have shown to decrease their work and life satisfaction (Schmidt and Hansson, 2018 ; Evans et al. , 2018 ; Cornér et al. , 2017 ), and thus, are more prone to opt for supervisory change. It is, therefore, important to highlight the students’ perspectives and experiences of this process. Thus, the purpose of this study is to explore how doctoral students experience a change in supervisory arrangements.

Material and methods

The study follows a qualitative, explorative design, which is considered suitable for exploring human experiences including people’s perceptions, opinions and feelings to shed light on the phenomenon of interest.

Sweden as a context of this study

In Sweden, PhD studies comprise 240 European credit transfer and accumulation system credits (equivalent to four years of full-time studies). Teaching is often part of doctoral students’ curricula when they are employed by a university, which can prolong their studies by one to two years. The number of newly enrolled doctoral students and those taking their doctoral degrees during 2018 was similar, coming to a total of around 17,000 doctoral students (SCB [ Statistics Sweden], 2019 ). No gender differences were reported among them in 2018. Of those who started their studies in 2010, 75% gained their degrees after eight years ( SCB [Statistics Sweden], 2019 ). The median age of the students was 32 years. As the majority (64%) of doctoral students are financed by being employed at a university ( SCB [Statistics Sweden], 2019 ), PhD candidates need to apply for the position in competition and cannot choose their supervisors when enrolling. Instead, supervisors and project leaders choose their doctoral students. For supervising a doctoral student in Sweden, one needs to have a PhD. Some universities also mandate completing a doctoral supervisor training course ranging from a few days to a few weeks.

Participants

Participants were recruited by applying purposeful sampling in combination with snowball strategy. Inclusion criteria for participation were being currently enrolled or having been enrolled at a Swedish university for a PhD program (graduation no later than 2010) and having experienced a change in supervisory arrangements. In total, 26 doctoral students were asked to participate in the study of which 19 agreed. Of the remainder, three did not reply and four declined participation.

To start with, three former doctoral students belonging to different subject areas and who had changed their supervisors (which the authors were aware of) were purposefully selected; they all agreed to be part of the study. After the interviews, the three participants were asked if she/he knew other doctoral students who had changed supervisors. These students were contacted by the authors and were asked to participate in the study.

The participants were between 31 and 58 years old (mean = 41.1) and were enrolled in five different universities in Southern Sweden. Of the 19 participants, 15 were women. In total, 12 of the participants had finalized their studies, mainly between 2018 and 2020 (of which two had a licentiate degree). The remainder were still enrolled as doctoral students and were at different stages of their program. Overall, they belonged to 11 different subject areas within social sciences including business-related and health-related subject areas, informatics and psychology.

Data collection

Data were collected from May to October 2020 through face to face, individual interviews with 19 doctoral students. A semi-structured interview guide was used that outlined a set of issues that were to be explored with each participant. However, the interviews allowed and welcomed openness to changes to follow the stories of the participants. Examples of the main questions are given below:

Can you tell me why you started your postgraduate education?

Could you describe your experiences of your postgraduate education (so far)?

Can you tell me about how do/did you experience your relationship with your supervisor/s?

What was the reason for the supervisory change?

How did you experience the process of the supervisory change?

How did the supervisory change affect you?

What are your recommendations to other doctoral students who are considering changing a supervisor?

One pilot interview was conducted to test the interview guide, which led to a minimal revision. Thus, the pilot interview was included in the analysis. Seven interviews were conducted in person while the remainder were conducted via the video communication tool Zoom, which guaranteed a face to face conversation. This latter option was mainly used due to current circumstances concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. Five interviews were conducted in English while the remainder were held in the participants’ native language, Swedish. On average the interviews lasted 57 min (ranging from 36 to 105 min). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Swedish law concerning research involving humans (SFS, 2003 ). Informed consent was given by all the participants prior to the interviews. The consent letter included information about the aim of the study, the right to withdraw at any given time without providing a reason, that participation was voluntary, that the interviews would be audio-recorded and that material would be stored in a safe way. Further, the participants were informed that the collected data would be treated confidentially and that only the authors of the study would be able to access it. The findings were presented at the group level.