8 David Foster Wallace Essays You Can Read Online

If you've talked to me for more than five minutes, you probably know that I'm a huge fan of author and essayist David Foster Wallace . In my opinion, he's one of the most fascinating writers and thinkers that has ever lived, and he possessed an almost supernatural ability to articulate the human experience.

Listen, you don't have to be a pretentious white dude to fall for DFW. I know that stigma is out there, but it's just not true. David Foster Wallace's writing will appeal to anyone who likes to think deeply about the human experience. He really likes to dig into the meat of a moment — from describing state fair roller coaster rides to examining the mind of a detoxing addict. His explorations of the human consciousness are incredibly astute, and I've always felt as thought DFW was actually mapping out my own consciousness.

Contrary to what some may think, the way to become a DFW fan is not to immediately read Infinite Jest . I love Infinite Jest. It's one of my favorite books of all-time. But it is also over 1,000 pages long and extremely difficult to read. It took me seven months to read it for the first time. That's a lot to ask of yourself as a reader.

My recommendation is to start with David Foster Wallace's essays . They are pure gold. I discovered DFW when I was in college, and I would spend hours skiving off my homework to read anything I could get my hands on. Most of what I read I got for free on the Internet.

So, here's your guide to David Foster Wallace on the web. Once you've blown through these, pick up a copy of Consider the Lobster or A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again .

1. "This is Water" Commencement Speech

Technically this is a speech, but it will seriously revolutionize the way you think about the world and how you interact with it. You can listen to Wallace deliver it at Kenyon College , or you can read this transcript . Or, hey, do both.

2. "Consider the Lobster"

This is a classic. When he goes to the Maine Lobster Festival to do a report for Gourmet , DFW ends up taking his readers along for a deep, cerebral ride. Asking questions like "Do lobsters feel pain?" Wallace turns the whole celebration into a profound breakdown on the meaning of consciousness. (Don't forget to read the footnotes!)

2. "Ticket to the Fair"

Another episode of Wallace turning journalism into something more. Harper 's sent DFW to report on the state fair, and he emerged with this masterpiece. The Harper's subtitle says it all: "Wherein our reporter gorges himself on corn dogs, gapes at terrifying rides, savors the odor of pigs, exchanges unpleasantries with tattooed carnies, and admires the loveliness of cows."

3. "Federer as Religious Experience"

DFW was obviously obsessed with tennis, but you don't have to like or know anything about the sport to be drawn in by his writing. In this essay, originally published in the sports section of The New York Times , Wallace delivers a profile on Roger Federer that soon turns into a discussion of beauty with regard to athleticism. It's hypnotizing to read.

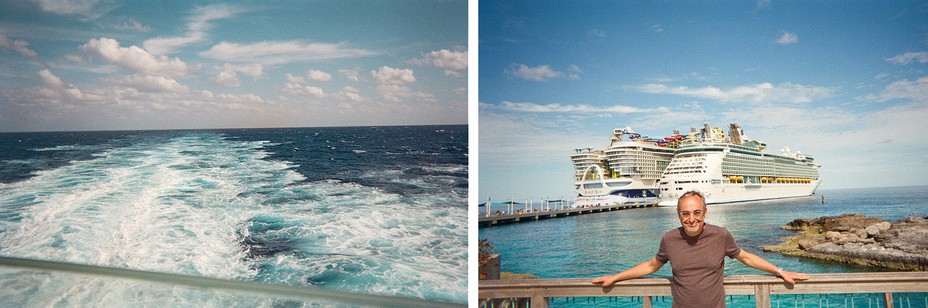

4. "Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise"

Later published as "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again" in the collection of the same name, this essay is the result of Harper's sending Wallace on a luxury cruise. Wallace describes how the cruise sends him into a depressive spiral, detailing the oddities that make up the strange atmosphere of an environment designed for ultimate "fun."

5. "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction"

This is definitely in the running for my favorite DFW essay. (It's so hard to choose.) Fiction writers! Television! Voyeurism! Loneliness! Basically everything I love comes together in this piece as Wallace dives into a deep exploration of how humans find ways to look at each other. Though it's a little long, it's endlessly fascinating.

6. "String Theory"

"You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it's hard."

Originally published in Esquire , this article takes you deep into the intricate world of professional tennis. Wallace uses tennis (and specifically tennis player Michael Joyce) as a vehicle to explore the ideas of success, identity, and what it means to be a professional athlete.

7. "9/11: The View from the Midwest"

Written in the days following 9/11, this article details DFW and his community's struggle to come to terms with the attack.

8. "Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage "

If you're a language nerd like me, you'll really dig this one. A self-proclaimed "snoot" about grammar, Wallace dives into the world of dictionaries, exploring all of the implications of how language is used, how we understand and define grammar, and how the "Democratic Spirit" fits into the tumultuous realms of English.

Images: cocoparisienne /Pixabay; werner22brigette /Pixabay; StartupStockPhotos /Pixabay; PublicDomainPIctures /Pixabay

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Last Essay I Need to Write about David Foster Wallace

Mary k. holland on closing the “open question” of wallace’s misogyny.

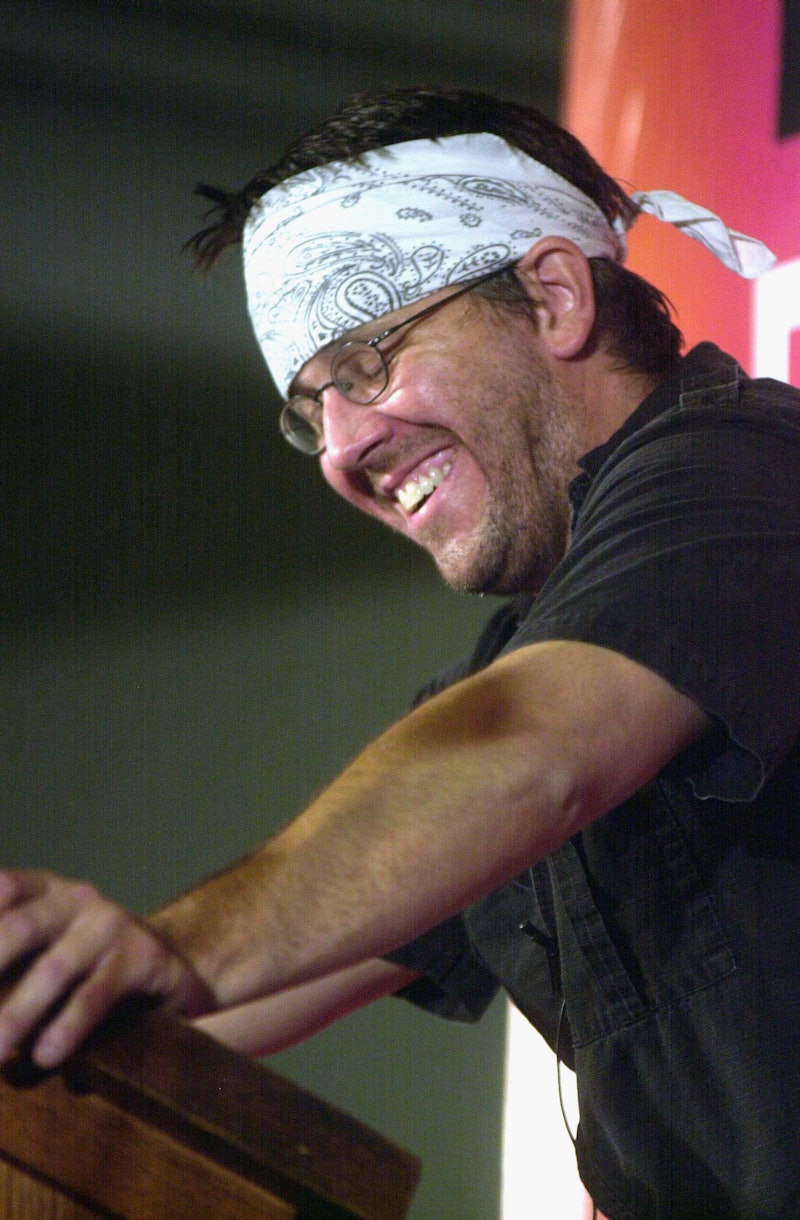

Feature photo by Steve Rhodes .

David Foster Wallace’s work has long been celebrated for audaciously reorienting fiction toward empathy, sincerity, and human connection after decades of (supposedly) bleak postmodern assertions that all had become nearly impossible. Linguistically rich and structurally innovative, his work is also thematically compelling, mounting brilliant critiques of liberal humanism’s masked oppressions, the soul-killing dangers of technology and American narcissism, and the increasing impotence of our culture of irony.

Wallace spoke and wrote movingly about our need to cultivate self-awareness in order to more fully see and respect others, and created formal methods that construct the reader-writer relationship with such piercing intimacy that his fans and critics feel they know and love him. A year after his death by suicide, as popular and critical attention to him and his work began to build into the industry of Wallace studies that exists today, he was first outed as a misogynist who stalked, manipulated, and physically attacked women.

In her 2009 memoir, Lit , Mary Karr spends less than four pages narrating the several years in which Wallace pursued her, leading to a brief romantic relationship that ended in vicious arguments and “his pitching my coffee table at me.” Unlike her accounts of the relationship nearly a decade later, Karr’s tone here notably remains clever and humorous throughout. She also follows each disclosure of Wallace’s ferocity with a confession of her own regrettable behavior: regarding his “temper fits” she admits to “sentences I had to apologize for” and assures us—twice—that “no doubt he was richly provoked.” After describing the coffee-table incident, she notes parenthetically that “years later, we’ll accept each other’s longhand apologies for the whole debacle,” as if having a piece of furniture thrown at you makes you as guilty as having thrown it.

Three years later D.T. Max published his biography of Wallace, in which he divulged more shocking details about the relationship with Karr—that Wallace tried to buy a gun to kill her husband, that he tried to push her from a moving car—while also dropping enough details about Wallace’s sex life and professed attitudes toward women to make him sound like one of his own hideous men. Wallace called female fans at his readings “audience pussy”; wondered to Jonathan Franzen whether “his only purpose on earth was ‘to put my penis in as many vaginas as possible’”; picked up vulnerable women in his recovery groups; admitted to a “fetish for conquering young mothers,” like Orin in Infinite Jest ; and “affected not to care that some of the women were his students.”

In a 2016 anthology dedicated to the late author, one of those students, Suzanne Scanlon, published a short story about a student having a manipulative, emotionally abusive sexual affair with her professor (called “D-,” “Author,” and “a self-identified Misogynist”), using characteristic formal elements of “Octet” and “Brief Interviews” and dominated by the narrative voice popularized by David Foster Wallace.

None of these accounts had any visible impact on fans’ or readers’ love of Wallace’s writing or on critics’ readings and opinions of his work. Rather, one writer, Rebecca Rothfeld, confessed in 2013 that Max’s record of (some of) Wallace’s misogynistic acts and statements could not shake her “faith in [his] fundamental goodness, intelligence, and likeability” because his “work seemed more real to me than his behavior did.” Critic Amy Hungerford took the opposite stance in 2016, proclaiming her decision to stop reading and teaching Wallace’s work, but without mentioning his abusive treatment of women or the question of how that behavior presses us to re-read the same in his work.

Another writer, Deirdre Coyle, explained her discomfort at reading Wallace not in terms of the author’s own behavior—which she gives no sign of being aware of—but because of sexual and misogynistic violence perpetrated on her by men she sees as very much like Wallace (“Small liberal arts colleges are breeding grounds for these guys”) and in terms of patriarchy in general (“It’s hard to distinguish my reaction to Wallace from my reaction to patriarchy.” Any woman who has been violated, talked over, and condescended to by this kind of man, the kind who thinks his pseudo-feminism allows him to enlighten her about her own experiences of male oppression and sexual violation, cannot help but sympathize with Coyle.

But in rejecting Wallace because of other men’s sexual violence and misogyny in general, she shifts the argument away from questions about how these function in the fiction and how Wallace’s biography might force us to re-read that fiction, and allows for the kind of circular rebuttal that a (male) Wallace critic offered a year later: not all male readers of Wallace are misogynists; therefore, women should listen to the good ones and read more Wallace; let me tell you why.

These pre-#MeToo reactions to Karr’s and Max’s reports of Wallace’s abuse of women clarify what is at stake as readers, critics, and teachers consider this biographical information in the context of Wallace’s work. For, while Wimsatt and Beardsley’s argument against the intentional fallacy is compelling and important, its goal is to protect the sanctity of the text against the undue influence of our assumptions about the person who wrote it. Arguments defending the importance of Wallace’s beautiful empathizing fiction in spite of his abuse of women threaten to do the opposite.

Like Rothfeld, whose admiration for Wallace’s fiction renders his own misogynistic acts less “real,” David Hering argues that “the biographical revelation of unsavoury details about Wallace’s own relationships” leads to an equation between Wallace and misogyny that “does a fundamental disservice to the kind of urgent questions Wallace asks in his work about communication, empathy, and power”—as if Wallace’s real abuse of real women is not worth contemplating in comparison with his writing about how fictional men treat fictional women. Hering’s use of the euphemism “unsavoury” to describe behavior ranging from exploitation to physical attacks, like his description of Wallace’s work regarding gender as “troublesome,” illustrates another widespread problem with nearly all critical treatments of this topic so far: an unwillingness to say, or perhaps even see, that what we are talking about in the fiction and in the author’s life is gender-motivated violence, stalking, physical abuse, even, in the case of Karr’s husband, plotting to murder.

In the wake of the October 2017 resurgence of Burke’s #MeToo movement, we see a curious split between Wallace-studies critics and others in their reactions to these allegations. Not only does Hering’s response downplay the severity of Wallace’s behavior and its relevance to his work; it also asserts Hering’s “belief” that Wallace’s work “dramatize[s]” misogyny, rather than expressing it—without offering a text-based argument or pointing to the critical work that had already done this analysis and found exactly the opposite to be true.

He also relies on a technique used by memoirists, bloggers, and critics alike in their attempts to save Wallace from his own biography: he converts an example of male domination of women into a universal human dilemma, erasing the elements of gender and power entirely, by reading Wallace’s silencing of his female interviewer’s voice in Brief Interviews as “embody[ing] the richness of Wallace’s work—its focus on the difficulty and importance of communication and empathy, and its illustration of the poisonous things that happen when dialogue breaks down.” Such a reading ignores the fact that when dialogue breaks down between an entitled man and a pressured woman , the things that can happen go beyond metaphorically poisonous to physically sickening and injurious—as so many of the stories in that collection illustrate.

Given the same platform and the same task—celebrating Wallace around what would have been his 56th birthday—critic Clare Hayes-Brady offered “Reading David Foster Wallace in 2018,” mere months after the social media flood of women’s testimonies about sexual violence had begun. It does not mention #MeToo or the public allegations that had been made about Wallace, raising the question of what “in 2018” refers to. When asked several months later “what’s changed?” in Wallace studies, after the public (but not critical) backlash had begun, Hayes-Brady falls back on the same generalizing technique used by Hering. She reframes accusations of misogyny as an entirely academic development, beneficial to Wallace studies and unrelated to #MeToo outcry against perpetrators of sexual violence (“a coincidence of timing”). She equates “flaws in his writing both technical and also moral and ethical,” as if women had been up in arms across Twitter over Wallace’s exhausting sentence structures.

When directly asked if Wallace was a misogynist, she replies “yes, but in the way everyone is, including me,” as if we neither have nor need a separate word for men who do not just live unavoidably in our misogynistic culture but also willfully perpetrate selfish, cruel, and violent acts of misogyny against women. That is, rather than responding humanely to indisputable evidence that our beloved writer was not the saint he would have liked us to think he was (and that we would have liked to believe him to be), Wallace critics—including me, in my silence at that time—refused to allow #MeToo to force the reckoning that was so clearly required. We did so by denying the relevance of his personal behavior to his fiction and to our work, or—worse—by participating in that age-old rape culture enabler: refusing to believe women’s testimony.

Those outside literary studies reacted quite differently to the renewed attention #MeToo brought to these accusations. After Junot Díaz was publicly accused on May 4, 2018, of sexually abusing women, causing immediate public protest, Mary Karr responded by reminding us on Twitter of the abuse she had reported nearly a decade earlier, prompting a series of blog articles and interviews that supported Karr by recounting the allegations made by Karr and Max. They also began to reveal the misogyny that had shaped and stifled public reception of those allegations.

Whitney Kimball pointed out that Max described Wallace’s violent treatment of Karr as beneficial to his creative output and part of what made him “fascinating”; that in praising the “quite remarkable” “craftsmanship” of one of Wallace’s letters, Max notes only in passing that the letter is Wallace’s apology for planning to buy a gun to kill Karr’s husband. Megan Garber noted the misogyny of an interviewer asking Max why “his feelings for [Karr] created such trouble for Wallace”—an example of what Kate Manne calls “himpathy,” or empathizing with a male perpetrator of sexual violence rather than the victim.

#MeToo also began to make the misogyny of Wallace’s work more visible to his readers. Devon Price describes how reading about Wallace’s abuses against women caused them to revisit Wallace’s work and see its gender violence for the first time. Tellingly, Price also realizes that one of the reasons they were depressed when they fell in love with Wallace’s work is that they were then in a physically, emotionally, and sexually abusive relationship. Price’s realization points to another common reason why readers are blind to or defensive about the misogyny in Wallace’s work and behavior, and to a key way in which the #MeToo movement can allow reading and literary studies to illuminate misogyny in synergistic ways: we are often blind to misogyny and sexual abuse, in fiction and in others’ behavior, because we are living in it unaware. And the awareness of the spectrum of sexual abuse brought by #MeToo testimonies reveals misogyny not just in the fiction that we read, but in our own lives—one revelation causing the other.

To date, no new criticism has emerged that directly considers the implications to his work of Wallace’s now widely reported misogyny and violence toward women. But the recent publication of Adrienne Miller’s memoir In the Land of Men (2020), which describes her years-long relationship with Wallace while she was literary editor at Esquire , makes a compelling, if unwitting, argument for the necessity of such biographically informed criticism. Miller documents the connection between Wallace’s life and work in excruciating detail, recounting extended scenes between them in which Wallace speaks and acts nearly identically to the misogynists of Brief Interviews , an identification he encourages by telling her that “some of the interviews were ‘actual conversations I had when I had to break up with people.’”

But though Miller lays out the “sexism” of Wallace’s fiction, especially Jest and Brief Interviews , more baldly than any of us Wallace scholars has so far, she remains, even from the vantage point of twenty years later and post-#MeToo, unable or unwilling to identify Wallace’s treatment of her as abusive or misogynistic. In fact, most shocking about the memoir is not its record of Wallace’s behavior but its methodical and steadfast refusal to acknowledge the gender violence of that behavior, and Miller’s disturbing pattern of normalizing, apologizing for, and denying it.

Ultimately, she attempts to redirect us from the question of whether her relationship with Wallace qualifies as abuse or sexual harassment by asking, “Who looks to the artist’s life for moral guidance anyway?” and “What are we to do with the art of profoundly compromised men?” But rather than neatly pivoting from Wallace’s culpability, these questions reveal important reasons why we must consider the lives of such men in conversation with their art. For these men are not merely passively “compromised” but aggressively compromis ing , in ways that our misogynistic culture obscures, and which savvy investigation of their art and lives can illuminate. And “moral” investigation is particularly indicated by the work of Wallace, who declared himself a maverick writer willing to return literature to earnestness and “love” (“Interview with David Foster Wallace” 1993), who wrote fiction that quizzes us on ethics and human value (“Octet” 1999), and who delivered a beloved commencement speech arguing the importance of recognizing one’s inherent narcissism in order to extend care to others.

What does it mean that this artist could not produce in his life the mutually respecting empathy he all but preached in his work (or, most clearly, in his statements about it)? What does it mean that a man and a body of work that claimed feminism in theory primarily produced a stream of abusive relationships between men and women in life and art? What can we learn about the blindness of both men and women to their participation in misogyny and rape culture, despite their professions of awareness of both? How might reading Wallace’s fiction in the contexts of biographical information about him and women’s narratives about their experiences of sexual violence enable us to better understand—and interrupt—the powerful hold misogyny and rape culture have on our society, our art, and our critical practices?

_____________________________________________________________________

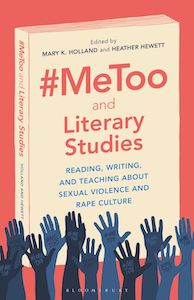

Excerpted from #MeToo and Literary Studies: Reading, Writing, and Teaching about Sexual Violence and Rape Culture , edited by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Academic. © 2021 by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett.

Mary K. Holland

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

A Brand New Interview with David Foster Wallace

This discussion of postmodernism, translation, and the internet has never been published in English

Eighteen years ago, writer and translator Eduardo Lago sat down with David Foster Wallace for a discussion that ranged from pedagogy to tennis to the influence of the internet on literature. The interview remained unpublished until Lago, an award-winning Spanish novelist, critic, and translator who teaches at Sarah Lawrence College, included it in his new book Walt Whitman ya no vive aquí , ten years after Wallace’s death . It has never been published before in English. The conversation has been lightly edited for readability.

Eduardo Lago: I know you’re not teaching right now, but can you talk a little bit about the reading lists of your courses?

David Foster Wallace: Most of what I teach is writing classes where we’re concentrating more on the student’s own writing. When I teach literature classes, I’ve taught everything from freshman literature, where the department will buy an anthology and I will teach them John Updike’s “A & P,” and John Cheever’s “The Five-Forty-Eight,” and Ursula le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walked Away From Omelas,” “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson, a lot of very what I consider to be very standard stories that are in all the anthologies. I’ve tried teaching more ambitious or strange or difficult fiction, but with freshmen and sophomores their preparation isn’t very good and it doesn’t work well. Graduate literature courses are usually themed courses, so what the reading lists are depends a certain amount on how I design the course, as I’m sure you know. I’ve taught a fair amount of Cormac McCarthy, who’s a writer I admire a great deal, and Don DeLillo and William Gaddis. I’ve taught quite a bit of William Gass, but usually his earlier books, and I teach poetry … I’m not a professional poet but I’m an avid reader of poetry, so I teach most of the contemporary poetry that’s available in book form.

EL: Do you consider yourself an accessible writer, and do you know what kind of people read your books?

DFW: That’s a very good question. I think the sort of work I do falls into an area of American fiction that, yes, that is accessible, but that is designed for people who really like to read and understand reading to be a discipline and to require a certain amount of work. As I’m sure you know, most of the money in American publishing gets made in books — some of which I think are very good — that don’t require much work. They’re almost more like motion pictures, and people read them on airplanes and at beaches. I don’t do stuff like that. But of the American writers I know who do some of the more demanding fiction, I think I’m one of the more accessible ones, simply because when I’m working, I’m trying to make it as simple as possible rather than trying to make it as complicated as possible. There’s some fiction that’s very good that I think is trying to be difficult by putting the reader through certain sorts of exercises. I’m not one of those, so within the camp people usually talk about me being one of the more accessible ones, but that camp itself is not regarded as very accessible and I think it tends to be read by people who have had quite a bit of education or a native love of books and for whom reading is important as an activity and not just something to do to pass the time or entertain themselves.

I think I’m one of the more accessible ones simply because I’m trying to make it as simple as possible rather than trying to make it as complicated as possible.

EL: I’ve read in a number of places that you intended Infinite Jest to be a sad book. Can you talk specifically about that aspect of the novel and what else were you intending to do when you started writing it?

DFW: I think what I meant by that was that there are some facts about American culture, particularly for younger people, that seem to me to be far clearer to people who live in Europe than to Americans themselves, which is that in many ways America is a wonderful place to live from a material standpoint, and its economy is very strong and there’s a great deal of material plenty, and yet — let’s see, when I started that book I was about 30, sort of upper middle class, white, had never suffered discrimination or any poverty that I myself had not caused, and most of my friends were the same way, and yet there was a sadness and a disconnection or alienation among I would say people under 40 or 45 in this country, that — and this is probably a cliche — you could say dates from Watergate, or from Vietnam or any number of causes. The book itself is attempting to talk about the phenomenon of addiction, whether it’s addiction to narcotics or whether it’s addiction in its original meaning in English which has to do with devotion, almost a religious devotion, and trying to understand a kind of innate capitalist sadness in terms of the phenomenon of addiction and what addiction means. Usually I would tell people I meant to do it a sad book because when I did a lot of interviews about Infinite Jest all people would seem to want to talk about was that the book was very funny and they wanted to know why the book was so funny and how it was supposed to be so funny, and I was honestly puzzled and disappointed because I had seen it as a very sad book, and that was my attempt to explain to you the sadness that I’m talking about.

EL: How would you define your literary generation?

EL: If you believe in that.

DFW: Can you explain the question a little bit, say who are the writers of the generation?

EL: Perhaps I mean that you belong in a certain age group that has inherited a literary tradition that you are trying to transform somehow. In other words, what are young American writers today like yourself — in a certain type of fiction because there are many different approaches to literature — doing. Do you think you belong in a group where your original work plays a role, or something like that?

DFW: Well, I don’t know. See, when people would ask me that question before it was because I was very young and I was in the youngest generation, and I think there’s probably a whole new generation now. A generation in American fiction is probably every five or seven years. Usually when people talk to me about my work, the other younger writers they lump it in with are William T. Vollman and Richard Powers, Joanna Scott, A. M. Homes, Jonathan Franzen, Mark Leyner. Those are all — I think Powers and Scott are in their early 40s, I’m 38, I think it’s all sort of writers now in their later 30s and early 40s and I think we all started publishing books at about the same time. And that group of younger writers, as I’m sure you know, we’re only a small percentage of the younger writers who are out there. There are plenty of active, productive young writers who do what I think is called Realism with a capital R: the sort of traditional, third person limited omniscient, central character, central conflict, classically structured kind of fiction. I know a couple of the other writers I get lumped in with, whom I just mentioned to you, and if there seems to be something in common, it seems to be that we all, particularly in college, were exposed to a great deal of first of all literary theory and continental theory, and second of all, classic American postmodern fiction, which means Nabokov and DeLillo and Pynchon and Barth and Gaddis and Gass and all these guys. And both of those exposures, it seems, make it constitutionally more difficult to do traditional stuff, because some of the best classic postmodern fiction really, at least for me, exploded or destroyed the credibility of a lot of the sort of conventions and devices that classic realism uses. Nevertheless, I think that what gets called classic American postmodernism — which would be, you know, metafiction or really high surrealistic fiction — has a very limited utility. Its essential task appears to me to be to be destructive — to clear away, to explode a lot of hypocrisies and conventions — but it gets rather tiresome rather quickly. Now that’s being kind of general. I myself personally find John Barth’s first few books interesting and then it seems to me that all he’s done since is work out certain techniques and certain obsessions over and over and over and over and over and over again. I don’t think any of the writers that I’ve mentioned, myself included, are comfortable with the idea of simply doing more of that kind of fiction. On the other hand we’ve all been influenced by it a great deal and I think for a whole lot of different reasons don’t see and understand the world in the way that classic realist fiction tries to capture or mirror.

I think that what gets called classic American postmodernism has a very limited utility.

So I think what I’m trying to say, in a long-winded way, is [that] probably the group I get lumped in with has been heavily influenced by American postmodernism, and of course by European postmodernism too — I mean Calvino — or Latin American writers like Borges and Marquez and Puig. But nevertheless we are also uncomfortable with some of the self-consciousness, and for me in particular some of the intellectualism, of standard postmodernism, and are interested in trying to do fiction that doesn’t seem to be formulaic or “traditional” but nevertheless has an emotional quality to it; is not meant simply to be about language or certain cognitive paradoxes, but is supposed to be about the human experience, what it is to be particularly an American and yet not be a John Updike or John Cheever traditional story.

EL: Just for a brief answer, why does tennis occupy such a space in your writings?

DFW: The biggest reason isn’t very interesting at all: It’s the one sport that I in particular know about. I grew up playing competitive tennis and just know a great deal more about it and follow it more avidly than any other sport. I think aside from one or two essays and Infinite Jest I don’t know that I’ve written anything else about tennis. There are reasons why so much of Infinite Jest has to do with tennis but those aren’t really autobiographical, it just has to do with the structure of the book.

EL: And how is that?

DFW: [groans] I set myself up for that one, didn’t I. You know, a very simple answer would have to do with the idea of constant movement but within a rigidly defined set of constraints and also with the idea of two and twoness and things moving back and forth between two sides in such a way that a pattern is created.

EL: What is the relationship between television and fiction, and have things changed much in the years following the publication of your essay?

DFW: That essay was actually written in 1990 and it didn’t come out until 1993. To be perfectly honest with you, I haven’t owned a television now for probably ten years. I sometimes watch television at friends’ houses and I just don’t know that much about American television anymore. I know that the purpose of that essay was largely to articulate some of the concerns and agendas of myself and some of the other younger American writers I mentioned to you. I don’t know that I could sum up the relationship between television and fiction now in the year 2000 in one or two sentences. I think the interesting answer is that serious literary fiction in America is in a very complicated love-hate relationship and dialogue with commercial entertainment in this culture, which probably is of no surprise to Europeans. It’s not just economic, it’s also aesthetic, and it also has to do with us both trying to produce things and sometimes entertain people but also to be ourselves, a generation who grew up watching television and understanding ourselves as part of an audience. So except from saying that I’m sure they’re still probably fairly closely connected — although now there’s such an explosion in internet technology and the idea of “interactive entertainment” that the relationship is probably vastly more complicated now than it was ten years ago when I wrote that piece.

The internet is almost the perfect distillation of the American capitalist ethos, a flood of seductive choices with no really effective engines for choosing.

EL: That was going to be my next question: how do you think the internet is affecting the art of fiction?

DFW: I think that’s a terrific question. Most of the journalism I read in America right now is interested in how the internet is going to affect the business of publishing. I personally think that the internet represents simply an enormous flood of available information and entertainment and sensations with very little assistance to the consumer in terms of choosing, finding, discerning between those choices and this sort of rabid, capitalist fervor with which the internet is being not just developed but invested in. I don’t have to tell you about the .com stock market explosion and all that. It seems to me, as just a layman and an amateur, that the internet is almost the perfect distillation of the American capitalist ethos, a flood of seductive choices. It’s completely laissez-faire, with no really effective engines for choosing or searching and everybody being much more interested in the economic and material aspects of it than some of the aesthetic and ethical and moral and political questions attached to it. I can’t think of a better summing up of what America’s strengths and weaknesses are right now, and I’m sure that there are writers who are interested in in the internet as a tool in fiction. As far as I can think it’s really only Richard Powers in Galatea 2.2 and he’s got a new book out called Plowing the Dark , which is partially about virtual reality. Powers, who is himself kind of a cyber-scientist, is really the only one who I think found really effective ways to use the web and the internet as an as an actual tool in fiction. I think most of the rest of us are kind of just standing around with our mouths open, amazed that everybody’s so excited about a phenomenon that really is nothing more than an exaggeration of what we’ve had up ’til now.

EL: Do you find any significant parallels between your aesthetics as a writer and the aesthetics of David Lynch as a filmmaker?

DFW: That’s a really good question. I don’t know. I did an article about David Lynch during which I discovered for myself some stuff about him. I think I pretty much decided he was almost a classical expressionist. I think Lynch and art movies in general are working off an almost classically surrealist aesthetic whereby they are going much more sort of by dream associations and literally unconscious stuff than for instance I would be. I think modern postmodern or avant garde fiction or whatever is quite a bit more deliberate and self conscious and claustrophobic than modern American art film. I do know that watching Lynch at his best is exciting for me both as somebody who loves movies and as a writer. I think he’s probably a Great Artist in the capital-G capital-A way. I don’t know that I understand either his or my own aesthetic enough to know. Blue Velvet , that was his big movie for me, came out in grad school and I know there’s a part of that article that talks about how it affected us but I think that it was more about the emotional effect than the aesthetic effect.

EL: Do you consider Infinite Jest your best book?

DFW: I don’t think in terms of best and worst.

EL: Are you working on a novel right now or do you intend to do so in the more or less near future?

DFW: You would have to explain what you mean by “work on.” I tend to work on several things at the same time and most of them fail at some point. I don’t know what the next thing I finish will be.

EL: The direction of my question was if your readers can expect a big book like Infinite Jest , big in all the meanings of the word.

DFW: It is a superstition with me that I do not talk about work that is not finished yet.

I tend to work on several things at the same time and most of them fail at some point. I don’t know what the next thing I finish will be.

EL: Very good. I’m fascinated by your use of footnotes in Infinite Jest and other books. On the one hand one could see them perhaps as a trademark of “academic writing”; on the other, it is a highly original form of innovation a way of restructuring plots, a fragmentary form of storytelling. Do you have a poetics of the footnote, and what would that poetics be like?

DFW: Not really. I started using them for Infinite Jest as a way to create one more sense of doubleness. One of the things that seems to me to be artificial about most fiction is that it pretends as if experience and thought and perception are linear and singular and that we’re thinking and feeling only one way at a certain point in time. You know, some of that is the constraint of the page, and I think to an extent the footnotes are to suggest at least a kind of doubling that I think is a little more realistic. I should point out though that Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman is just one example I can think of [that also uses footnotes], I believe John Updike’s A Month of Sundays as well. I certainly did not invent this. I leaned on it very heavily in Infinite Jest and I think got in a sort of habit of thinking and writing that caused me to lean on it some more. The last couple things I’ve done don’t have any footnotes in them. They’re certainly not a trademark, at least I hope they’re not. I think they just sort of became a compulsion for a little while.

EL: Another very interesting aspect of your work is the use of fictional interviews in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men . Can you talk about the genesis of that idea?

DFW: Oh boy. There was a great deal of the first draft of Infinite Jest that took place in interviews and I think most of that got cut out. I think I like the idea of interviews because I like the idea of a transcript; it reduces everything to voice in a plausible way. There’s some fictions that just have voices talking to you but that always seems kind of mannered to me. This is a plausibly realistic way to represent nothing but somebody speaking and allowing the reader to know and feel about that character entirely through her voice. In a book of short stories that just came out, it’s a little different, because you get only one side of the interview and so one of the things the answers are doing is, hopefully, helping the reader to guess what the questions were and over time to develop an idea of the character and ideology of the of the interrogator, of the questioner. So I don’t know that I have an aesthetic of it; I find it an interesting style. It’s also not one that I invented. I know DeLillo has written at least a couple of short stories that consist entirely of interviews or transcripts, you know, Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” any sort of dramatic monologue has the implication of a sort of conversation of which you’re only hearing part or one side.

EL: I have not not been able to read Signifying Rappers: Rap and Race in the Urban Present which I understand you co-wrote with Mark Costello. Could you talk briefly about that book?

DFW: Um, sure! That was a book that was written in the late ’80s which was the time in America when rap music, particularly something called gangsta rap, which is very violent and materialistic and misogynistic, became very popular and also popular with white listeners, and the book is really just a long essay on what it’s like to be white in America and to listen to this music and also to like this music and why white listeners might find something to identify with or or feel strongly about in the music. That’s really all, it was a very small book.

EL: In my interviews with North American writers, I sometimes find that many of them remain very endogamic, they almost exclusively read other American writers and talk about North American literature. Is that the case with you? Are you aware of developments in Europe or in other continents?

DFW: The strange thing, Eduardo, is there’s stuff I have to read for school, there’s stuff I have to read for work and my own work, and there’s stuff I read for fun. I read less contemporary American fiction than I do anything else. Part of it is it’s not helpful in my work, because I don’t want my work to have anything to do with what other people are doing. I don’t find it much fun because I think I read it more critically than I read other stuff I end up reading. I’m not terrifically conversant with developments in European and Latin and Asian fiction but I read probably about as much of it as any other American does. I’m not terrifically comfortable with translations, although Suzanne Jill Levine and [Gregory] Rabassa seem to me to be good enough that I don’t feel too guilty reading Spanish language fiction, although most of the Spanish language fiction I read comes from Latin America.

EL: The book that has just been published in in Spain is Girl with Curious Hair. Do you feel very removed from that book, aesthetically, and the first novel too?

DFW: I didn’t even know that any of my stuff had been published in Spain. I feel pretty removed from anything that’s in translation, because I think that when you’re reading the translation of a book, and I mean absolutely no offense, if [someone is reading] your translation of The Sot-Weed Factor then the readers are really enjoying Eduardo Lago’s book. I think most of this is formed for me as a reader of poetry: if you’re not reading something in the original you’re not reading anything remotely like what the author wrote. There are stories in Girl with Curious Hair that I think are very very good. It also seems to me to be a book written by a very very young man.

EL: Which are the ones you like the best?

DFW: The very first story in there, which is about a game show that I don’t know if people in Spain will have heard of called Jeopardy, is a very very good story, and there’s a story about Lyndon Johnson that I think works very well. There’s a story about somebody having a heart attack in a parking garage that I think must have been hard to translate because it’s mostly one long sentence. I don’t know whether anybody will like it, but that’s more or less a perfect story, I think. And the very last piece in there which is partly about John Barth, I really liked when I did it and then for a few years I didn’t like it at all and was tired of talking about it and I re-read it about a year ago and actually now think it’s very good again. [laughs]

EL: What you did with John Barth, was it some kind of literary exorcism in the sense of what you were saying before: that enough was enough with…

DFW: I think that in some ways that story, or I guess it’s really even a novella, I’m not sure, is meant to carry certain axioms of classic American postmodernism to their logical conclusion. But also to talk about a tremendous sadness and emotion that I think is implicit in really good kind of classic postmodernism that I don’t get the sense that the authors are aware of. So… There was kind of a love-hate thing with Barth there, I had just finished a graduate writing program at Arizona and had sort of very complicated feelings about the idea of MFA programs and “schools” for learning to write fiction. I think if anything that piece for me was more of an exorcism of academic fiction than it was of John Barth in particular. Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse, in America it’s this sort of sacred text, kind of Eliot’s “Waste Land” of postmodernism, and it was just probably the easiest thing to write about.

EL: I’m going back briefly to some things that you were saying before. You partially answered the question I was going to ask you, which has to do with your relationship with so-called classical postmodernism in America. You seem to indicate a type of writing which incorporates a good dose of experimentalism but which results in a radically new form of realism somehow, not the typical tradition of realism. What would that realism be like, or is realism even a good term?

DFW: It’s a good question. I feel as if I’m almost the last person who would answer it, though, because, I’m sure you can understand this, working on fiction for me — I mean I think of myself mostly as a fiction writer, but it’s very hard and very scary for me and for the most part I go by whether what I’m working on feels alive to me or not. I don’t even know if can explain that; sometimes it feels alive and real and I feel as if I’m in a conversation with the characters and parts of myself and the reader and it’s just very exciting, and other times it feels false and arch and postured and formulaic. Now, that’s talking about my own work; as a reader I think I get the same sort of sense. The stuff that I really like tends for me to be essentially about emotion and spirituality for people living in America at the Millennium, and yet it’s not stupid or trite or sentimental. It’s emotion and spirituality that has to be earned through tremendous amounts of cognitive processing [laughs] and certainly a great deal of political — boy, see, I’m not answering this well. My real answer to that is that what you just told me would be a good description of the fiction that I like to read. When it’s experimental-looking, I never get the sense that it’s experimental because it’s trying to be experimental or trying to make some sort of coy point about structure. It seems that it’s experimental because that was the one and only inevitable way that the author could convey the dimensions of experience and emotion and cognition that was the story’s world. And what I’m trying to do is describe the fact that there are examples of both classic realism and classic sort of avant garde experimentalism that I truly truly love, and mostly as a reader I try to articulate what it is I love about them. And I think as a writer, that’s certainly what I want in in my own work, but as you’re well aware it’s not a matter of sitting there writing something saying “okay, now what I’m doing is I’m going to go for a certain kind of experimentalism but I want it to seem realistic too.” It’s more how it kind of tastes in my mouth or feels in my stomach as I’m doing it.

The fiction I like to read is experimental because that was the one and only way that the author could convey the dimensions of experience that was the story’s world.

EL: Are you aware of the fact that they are going to publish Infinite Jest in Spanish?

DFW: No, my agent and I have made a deal where I am not told about translations, because if they’re in a language that I can read, I interfere in the translation, and if they’re in a language I cannot read it just drives me crazy and I lie awake at night worrying about that [laughs]. So I just don’t get told.

I wish the translator a lot of luck because I don’t think Infinite Jest is translatable. I think the English is too idiomatic. It’s obviously flattering to have your work translated, but it’s also very scary. Because readers are going to think it’s you.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

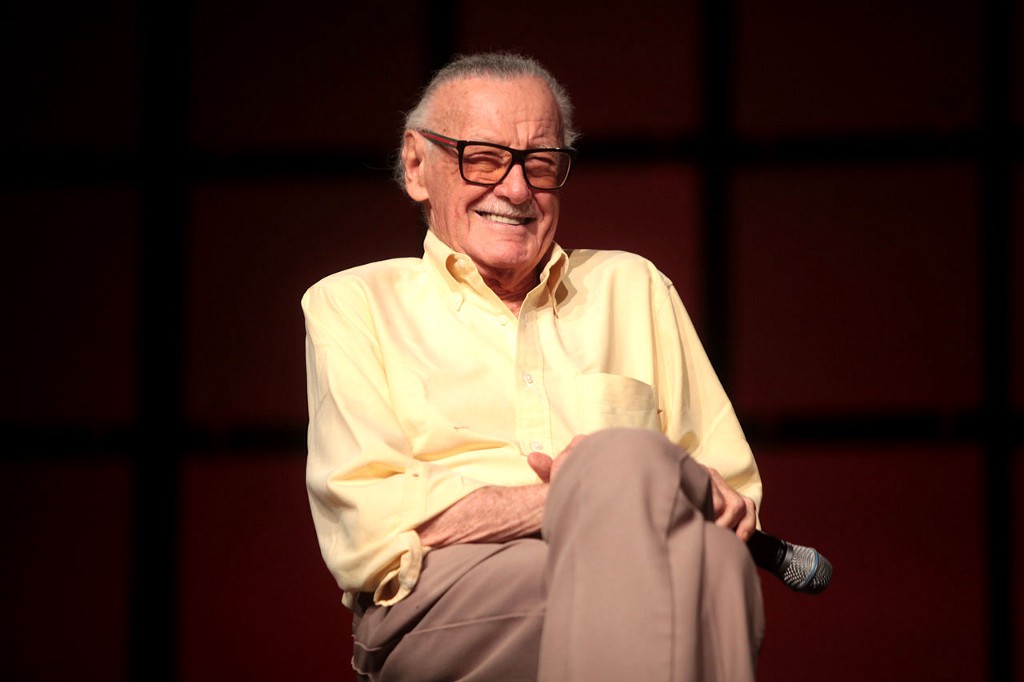

Why Stan Lee’s Death Is a Loss for Literature

The comics giant didn’t just invent your favorite superheroes—he also expanded the definition of a reader

Nov 16 - Carrie V. Mullins Read

More like this.

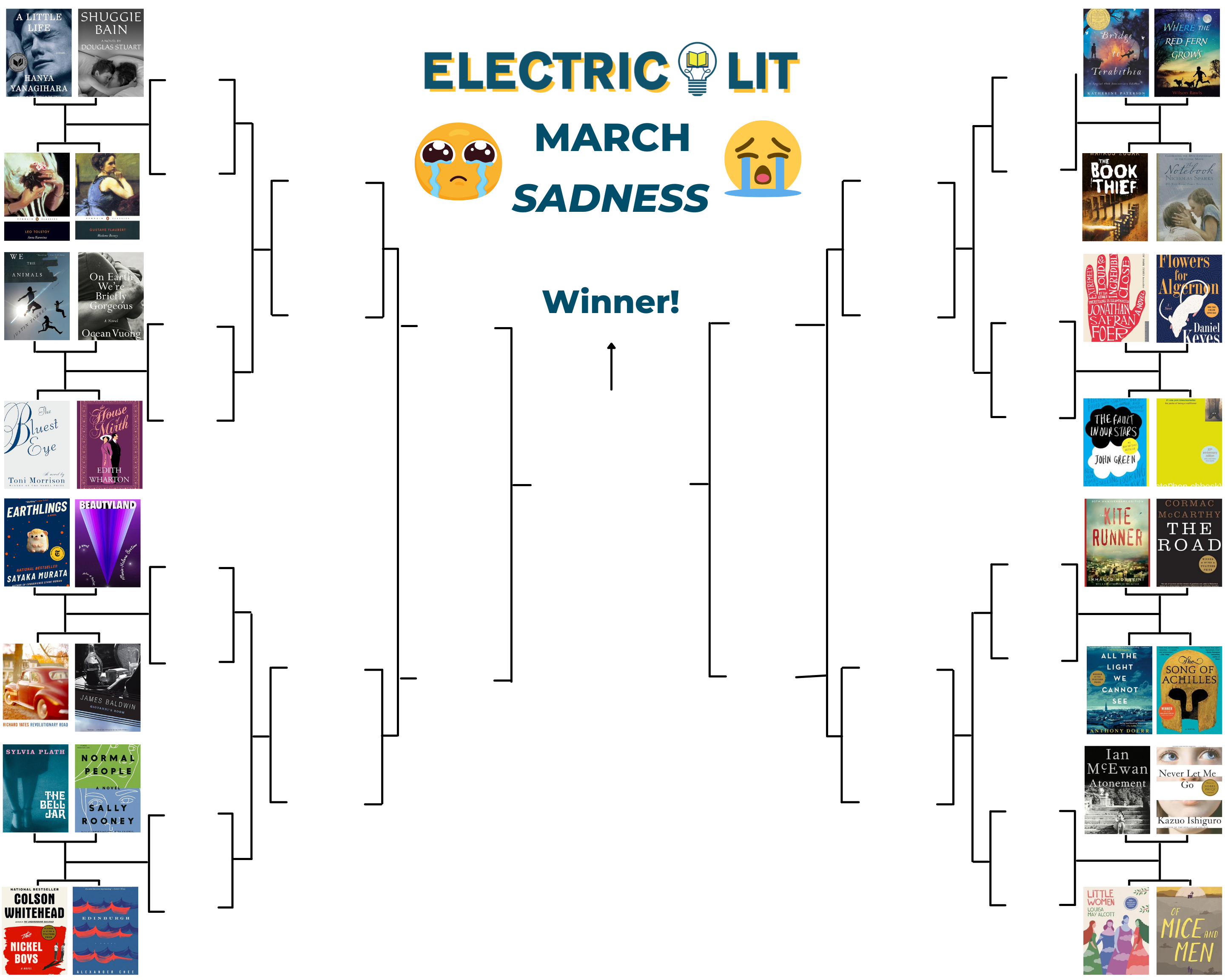

Announcing the Winner of March Sadness

There can only be one saddest of them all

Apr 2 - Katie Robinson

“Worry” is the Novel of the Online Generation

Alexandra Tanner discusses the false promise of the internet, the evangelicalism of MLMs, and Mormon mommie influencers

Mar 26 - Jacqueline Alnes

Help Us Choose the Saddest Book of All Time

This year, leave March Madness behind and vote in March Sadness instead

Mar 25 - Electric Literature

David Foster Wallace and the Joy of Irony

- July 25, 2022

Raymond Dokupil

- Articles , Arts & Culture Articles

“I want to convince you that irony, poker-faced silence, and fear of ridicule are distinctive of those features of contemporary U.S. culture (of which cutting-edge fiction is a part) that enjoy any significant relation to the television whose weird, pretty hand has my generation by the throat. I’m going to argue that irony and ridicule are entertaining and effective, and that, at the same time, they are agents of a great despair and stasis in U.S. culture, and that, for aspiring fictionists, they pose terrifically vexing problems.” – David Foster Wallace, A Supposedly Fun Thing

“the problem with making yourself stupider than you really are is that you very often succeed.” – c.s. lewis, the magician’s nephew, my meditations on irony began with two pieces from david foster wallace. the first was his essay “e unibus pluram: television and u.s. fiction,” written in 1990 and published in 1993. the second was an interview of wallace conducted by a german television station in 2003. while these are by no means considered wallace’s most prominent creative products, they are central to wallace’s philosophy and i will refer to them throughout the course of this essay., wallace died by suicide in 2008, supposedly as a result of being removed from his antidepressant medications. but we do a disservice to wallace’s intellectual struggles if we simply conclude that he “died of depression.” in his 2003 interview, wallace explained his inspiration for infinite jest began with a much deeper problem than his own mental health condition:, “for the upper middle-class in the u.s., particularly younger people, things are often materially very comfortable, and there’s also often a great sadness and emptiness…i started [ infinite jest ] after a couple of people, not close friends, but people i knew, who were my age [and] had committed suicide. it just became obvious that something was going on. and i know that that impulse was part of starting the book.” [1], wallace was interested in what had driven people of his generation to suicide, and in some sense infinite jest was an investigation of that question. but the reader who was not familiar with wallace himself may not have been aware that he was conducting such an investigation. to quote wallace,, “i’m not often all aware of stuff that’s really funny in the book…i set out to write a sad book. and when people liked it and told me that the thing they liked about was that it was so funny, it was just very surprising.”, jennifer frey, professor of philosophy at usc, describes wallace as someone who “wanted to be charles dickens and couldn’t.” [2] frey’s assessment of wallace is not to say that wallace had delusions of grandeur—quite the contrary. if the duty of the novelist is to identify and provide answers to the particular cultural malaise of his own time in accessible and contemporary language, no one took this duty more seriously than wallace. the undertaking of such a project was what defined the success of dickens, austen, tolstoy, dostoevsky, and the like. it just so happens that today’s cultural malaise is apparently in some state can only be described as an addiction to postmodern irony, and this poses an especially pressing problem for artists., the use of postmodern irony originally began not as a philosophical movement but with the “metafiction” of elite avant-garde novelists. but by the time of the 80s and 90s, postmodern irony had become so mainstream that it was appearing on the david letterman show and pepsi commercials. how can novelists provide an anecdote to postmodern irony when the novelists themselves were responsible for developing it wallace saw that there was a serious (if not insurmountable) challenge in using fiction to solve a problem which the whole genre of fiction had itself embraced. he wanted to answer what dostoevsky called “the desperate questions of existence.” but to truly seek the answer, to ask the question as if you really wanted the answer, would be received by modern audiences merely as moralistic finger-wagging. it is now considered banal and unsophisticated to say what you really mean or claim that what you are saying is actually true. this is the way the universe ends, not with a bang, not even with a whimper, but with a perfunctory roar of canned laughter from saturday night live., one might say that the solution to this problem is simply to ignore the cultural riffraff and return to a more classical state of mind. maybe wallace’s problems are merely the product of his own vanity. he wanted to say what he meant and still be considered a relevant turn-of-the-century novelist. but it is not so simple to escape an addiction to a certain habit of thinking. wallace knew that if he simply adopted some higher, more classical form of language, he would risk being branded as another alan bloom type and dismissed as yet another conservative doomsday prophet. the effects of postmodern irony are so ubiquitous that it could almost be described as cancerous on a cellular level, and no one is immune to it, not even conservatives., indeed, the modern disease of cancer is a very appropriate analogy. cancer cells are not harmful when they work for us. they only become a disease when they turn against us. when rationality turns against us, the soul is at civil war. you may try criticizing the disease of postmodern irony, but you cannot wield the critical mind against postmodernism any more than you can run to the police for aid if you are being chased by them. criticism itself is the thing that has gone wrong. our present situation cannot be resolved by returning to classical irony. a more serious operation is at hand., wallace felt that his audiences were so addicted to these habits of thought that there was no other way of writing fiction except in the language of postmodern irony. by most measurements, this project was a failure, and wallace knew it. wallace’s suicide was not just manic depression. one cannot read his work without being haunted by the sobering suspicion that the cause of his suicide was directly related to the fact that he could not resolve the problems he identified in his writing. assuming that wallace’s critiques of u.s. literature are legitimate and not simply the obsessive pessimism of a disgruntled manic depressant, it is incumbent upon us to wrestle with these critiques as if our life depended on them, because for wallace, it did., irony, comedy, and the devil, i am both a drama teacher and a debate coach, which comes as a surprise to many people who see rhetoric and theatrical arts to be as different as apples and oranges. debate is rational, analytical, left-brained (they say) while drama is artistic, creative, visual, spatial, right-brained. in many ways, drama and debate are closer cousins than they appear, but the strangest common attribute they share is the constant recurring character of the devil. the phrase “devil’s advocate” ( advocatus diaboli ) has its origins in the catholic church, but the methodology itself is part of an older tradition rooted in the socratic method (διαλεκτική). if we note the latin and greek origins of “devil” and “dialectic”, we see their kinship on more obvious display. the word for devil is diabolos , meaning “to tear through.” “dialectic” or “dialogue” comes from dialektike, or “to speak through.” one must not forget, however, that playing “devil’s advocate” is just that: playing. it is an ironic stance. the devil’s advocate pretends to believe the opposite of what he really believes in the service of the thesis, with the intention of sharpening and narrowing the interlocutor’s conclusion. but playing the devil is playing with fire, and things do have a way of getting out of control., in the arts, particularly in comedy, there is a similar attraction to “playing the devil.” the comedic opportunities are obvious. there is nothing particularly funny about saying, for example, “i love beyonce,” but put on devil’s horns and say the exact same thing, and it becomes a joke (about which beyonce happens to be the unfortunate victim). the word satan means “accuser” and comedians generate laughter by doing precisely that: accusing. the devil calls black “white” and white “black”—anything the devil condones is, at the same time, a damning indictment. for a comedian, playing the devil is a goldmine for comedy. comedy, like rhetoric, thrives on reductio ad absurdum —a tactic which reveals the ridiculous by seeing the world through the devil’s perspective. rationality, dialectic, comedy, and the devil are all devices in the ironist’s toolkit., of course, i am not saying that comedy is a satanic profession (or am i ha ha, just kidding.) but the comedian’s reputation for being (secretly and ironically) the most depressed person in the room is so well-known now that it is almost a cliché to point it out. the “sad clown” has become a stereotype. it is easy to see why. the ironic stance is liberating and, at the same time, dangerously addictive. it was wallace who pointed out that the original meaning of addict, addicere , meant religious devotion. he continually emphasized the importance of human beings needing to be able to worship something. what was worthy of our worship, however, wallace did not know., humor and violence, it is a given that much of comedy depends on making a jab at another’s expense. there is an implicit violence in comedy which is revealed in our language by the very fact that we call the ironic twist the “punchline.” in film, visual humor is often referred to as a “gag.” being the “butt-end” of a joke calls to mind the picture of being bludgeoned by the end of a spear. when a joke is funny enough you can even say that it “kills you” or that you “died laughing.” i used to write comedy sketches as a teenager and stumbled across this comedic maxim independently of any professional tutelage: pain is funny. this raised for me a rather uncomfortable question. is the postmodern claim true that all language is simply masked violence, we are taught as children that happy people laugh, and sad people cry. but if it is true that all humor depends on some form of violence or cruelty, then the true makeup of the human psyche is much more malevolent than we supposed. in fact, it is entirely malevolence, and the postmodern claim that all speech is violence is true. there is no difference between “wholesome” comedy and “black” comedy—there is only mildly violent and more violent, and your taste for either depends entirely on your tolerance for pain., it is true that we tend to idealize the innocence of children and gloss over certain acts of childhood cruelty which, without discipline, will later develop into undisguised malevolence. an honest interrogation of human nature will reveal to us the unpleasant truth of our own darkness. the same spirit which drives a mean child to pull the wings of a moth may be the same spirit which drives him to torture political prisoners in an internment camp. should we assume that this malevolent spirit composes the whole of the human spirit, many would naturally respond to this accusation by insisting upon the inherent innocence of children. but the cynic can easily blockade any attempt to return to such a paradisal state of mind by dismissing it as sentimentalism. once the accusatory stance has been assumed, it difficult, perhaps even impossible, to go back. irony is caustic: once the punchline has been delivered, the previous perspective dissolves in the light of the (superior) ironic perspective. once the accuser has spoken, we see our nakedness, and are ashamed., c.s. lewis and the devil, c.s. lewis was a master satirist, and it is not an accident that one of lewis’ must humorous works consisted in him playing the devil in the screwtape letters . screwtape, a senior devil instructing his nephew on the ways of damnation, devotes an entire letter to the subject of laughter. screwtape divides the four kinds of laughter into joy, fun, the joke proper, and flippancy. for screwtape, joy is the least desirable form of laughter:, you will see [joy] among friends and lovers reunited on the eve of a holiday. among adults some pretext of jokes [3] is usually provided, but the facility with which the smallest witticisms produce laughter at such a time shows that they are not the real cause. what the real cause is we do not know. something like it is expressed in much of that detestable art which the humans call music, and something like it occurs in heaven—a meaningless acceleration in the rhythm of celestial experience, quite opaque to us. laughter of this kind does us no good and should always be discouraged. besides the phenomenon is of itself disgusting and a direct insult to the realism, dignity, and austerity of hell . [4], screwtape’s ignorance of joy is key to lewis’s work and provides insight into the plight of the comedian: “what the real cause is we do not know .” lewis, of course, knows about joy, but he must pretend that he does not know, because he is in the ironic position of the devil. the greek root for irony, eironeia, means “feigned ignorance.” if the ironic stance is to play the devil, such ignorance is necessary for the role, for the devil knows nothing of joy. given the nature of irony as such, it becomes clear where comedians go wrong. if you make a career out of playing the devil and become too used to seeing the world from his point of view, there may come a day when the “feigned ignorance” is not so feigned. comedy is cutthroat industry, and the one who wishes to be the king of comedy must be funny all the time . he cannot afford taking off the horns even for a second. if there is no use for joy in his profession, why keep on pretending why not make a faustian deal and become the devil himself the depressed clown is depressed because he pretended to know nothing of joy until he really didn’t. as lewis put it in the magician’s nephew , “the problem with making yourself stupider than you really are is that you very often succeed.” [5], fun, says screwtape, is related to joy and is therefore also of no interest to him. any kind of disinterested fun or enjoyment of something, which cannot be proven to really be at anyone’s expense, obviously cannot be very fertile grounds for cultivating vice. the joke proper is a “much more promising field” for screwtape. screwtape defines the joke proper as the “sudden perception of incongruity” and lewis is probably referring to the more formal kind of joke-telling which depends on an ironic twist and a punchline (i.e. “a man walks into a bar…”). the joke proper is about having a “refined” sense of humor, which i find to be much more characteristic of british than of american comedy. the joke proper is the mother of flippancy, and it is flippancy which screwtape holds in highest regard. as an extension of the west, american tends to take british sensibilities to their farthest extremes, and it is not surprising that flippancy has become our primary mode of humor. screwtape says,, flippancy is the best of all…only a clever human can make a real joke about virtue, or indeed about anything else; any of them can be trained to talk as if virtue were funny. among flippant people the joke is always assumed to have been made. no one actually makes it; but every serious subject is discussed in a manner which implies that they have already found a ridiculous side to it. if prolonged, the habit of flippancy builds up around a man the finest armor against the enemy that i know, and it is quite free from the dangers inherent in the other sources of laughter. it is a thousand miles away from joy; it deadens, instead of sharpening, the intellect; and excites no affection between those who practice it ., at the heart of the problem of postmodern irony is demonic flippancy. this is the cardinal sin of postmodernism which david foster wallace failed to identify. it is impossible to employ postmodern irony as a means to escape flippancy and return to joy. the title of wallace’s novel, infinite jest, meant more than even he realized: it is no accident that hell is described as a bottomless pit. insofar as the western literary tradition has embraced postmodern irony, fiction as an art form is dead. if the novel is to survive, this tradition must be abandoned. only by a total death of this tradition can our culture resurrect the childlike appreciation of disinterested joy., the rediscovery of joy, i argued in part 1 of this essay series that the toddler playing peek-a-boo was the “atomic building block” of laughter. the rediscovery of joy is the most urgent quest of our present age—the “desperate question of our existence.” our call to action, then, is to look to the child. the toddler plays with a narrative in which the mother does not exist, but only in the interest of celebrating her existence. his “irony,” if we are to call it that, is predicated on joy, because the punchline depends not on accusing the solidity of her existence, but on affirming her solidity., joy is a certain quality of being which, by definition, is opaque to the ironic stance, because it is a thing outside of irony. and it is this quality of being which we must somehow return to. we must become as children to enter the kingdom of heaven. we must be born again. the ironist sees at once that such a thing is impossible. “how can one be born again” asks the bewildered rationalist thinker nicodemus. “he cannot enter again into his mother’s womb, can he” jesus answers,, that which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the spirit is spirit. do not be amazed that i said to you, ‘you must be born again.’ the wind blows where it wishes and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going; so is everyone who is born of the spirit., nicodemus said to him, ‘how can these things be’, jesus answered and said to him, ‘are you a teacher of israel and do not understand these things truly, truly, i say to you, we speak of what we know and testify of what we have seen, and you do not accept our testimony. if i told you earthly things and you do not believe, how will you believe if i tell you heavenly things no one has ascended into heaven, but he who descended from heaven: the son of man. as moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the son of man be lifted up; so that whoever believes will in him have eternal life.’ [6], christ says that we must be born of the spirit to inherit the kingdom. those born of the spirit evade the accusatory stance of the ironist. the ironist cannot “zoom out” over those born of the spirit and accuse them, because they are like wind and their origins cannot be identified. christ as the divine logos is origin itself. christ’s statement leaves the final arbiter of truth in a domain outside of argument, posing problems for both the atheist and the christian apologist alike. even if we were proclaim upon the rooftops, “joy is the final layer of sincerity,” we would not yet have saved ourselves, even if such a statement were true—even if we sincerely say it. irony—or rather, the rational principle—cannot discover joy. if the truth cannot be arrived at by argument, our knowledge of joy depends entirely on revelation. no matter how well the comedian perfects his art, no matter how loud his audience howls and whoops with overtures of approval, he has not come one step closer to creating joy. joy must be revealed to us in a divine action of grace, or not at all. what other choice do we have, [1] wallace, “david foster wallace unedited interview”, 2003, https://www.youtube.com/watchv=iglzwdt7vgc, [2] jennifer frey, “the therapeutic fiction of david foster wallace”, sacred and profane love , 2021, https://sacredandprofanelove.com/podcast-item/ep-32-jon-baskin-on-the-therapeutic-fiction-of-david-foster-wallace/, [3] lewis deliberately capitalizes the word “joke” and “laughter.” i do not know whether this is some british peculiarity or whether lewis has in mind some idea of a perfect platonic joke and therefore capitalizes it for emphasis., [4] the screwtape letters, ch. xi, [5] lewis, the magician’s nephew, [6] john 3:6-15, * see parts 1 and 2 of raymond’s essays here and here ..

Raymond Dokupil is a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He co-hosts a culture and literature podcast: Unreliable Narrators .

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

- previous post: What’s Left of Cosmopolitanism? A Review of “Cosmopolitanism and Its Discontents”

- next post: Curt Jaimungal: Humor and Free Will

Subscribe to VoegelinView via Email

Stay informed with the best in arts and humanities criticism, political analysis, reviews, and poetry. Just enter your email to receive every new publication delivered to your inbox.

Email Address

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Another Thing to Sort of Pin on David Foster Wallace

By Maud Newton

- Aug. 19, 2011

Ten years ago, David Foster Wallace admitted in “Tense Present,” one of his best and most charming essays, to being a “SNOOT,” which he defined as a “really extreme usage fanatic, the sort of person whose idea of Sunday fun is to look for mistakes in Safire’s column’s prose itself.” He outed himself while writing in Harper’s on Bryan A. Garner’s Dictionary of Modern American Usage, a book, he says, that serves to confirm its author’s “SNOOTitude while undercutting it in tone.”

Ultimately, though, “Tense Present” is as much about Wallace’s own rhetorical postures as about Garner’s, so much so that Wallace might as well be talking about himself. Garner’s book is “so good and so sneaky,” Wallace contends, because it relies on a “subtle rhetorical strategy.” Its “Ethical Appeal” amounts to “a complex and sophisticated ‘Trust me,’ ” one that “requires the rhetor to convince us not just of his intellectual acuity or technical competence, but of his basic decency and fairness and sensitivity to the audience’s own hopes and fears.”

Wallace, too, strived to make ethical arguments while soothing and flattering his readers and distracting them from the fact that arguments were being made. He was inarguably one of the most interesting thinkers and distinctive stylists of the generation raised on Jacques Derrida, Strunk and White and Scooby-Doo, and his nonfiction writings, on subjects as diverse as cruises, porn, tennis and eating lobster, are a compelling, often dizzying mix of arguments and asides, of reportage and personal anecdotes, of high diction (“pleonasm”), childlike speech (“plus, worse”), slacker lingo (“totally hosed”) and legalese (“what this article hereby terms a ‘Democratic Spirit’ ”), often within the course of a single paragraph. As John Jeremiah Sullivan astutely observed in GQ , Wallace repudiated the demands of “the well-tempered magazine feature,” which “seeks to make you forget its problems, half-truths and arbitrary decisions.” Yet Wallace’s rhetoric is mannered and limited in its own way, as manipulative in its recursive self-second-guessing as any more straightforward effort to persuade.

Geoff Dyer, an essayist as idiosyncratic and perceptive as Wallace but far more economical, confessed recently in Prospect magazine that he “break[s] out in a mental rash” when forced to read Wallace. “It’s not that I dislike the extravagance, the excess, the beanie-baroque, the phat loquacity,” Dyer wrote. “They just bug the crap out of me. ” Wallace’s nonfiction abounds with qualifiers like “sort of” and “pretty much” and sincerity-infusers like “really.” An icon of porn publishing described in the essay “Big Red Son,” for example, is “hard not to sort of almost actually like.” Within a brief excerpt from that piece in The New York Times Book Review, Wallace speaks of “the whole cynical postmodern deal” and “the whole mainstream celebrity culture,” and concludes that “the whole thing sucks.” Nor is this an unrepresentative sample; “whole” appears 20 times in the essay, so frequently that it begins to seem not just sloppy and imprecise but argumentatively, even aggressively, disingenuous. At their worst these verbal tics make it impossible to evaluate his analysis; I’m constantly wishing he would either choose a more straightforward way to limit his contentions or fully commit to one of them.

Of course, Wallace’s slangy approachability was part of his appeal, and these quirks are more than compensated for by his roving intelligence and the tireless force of his writing. The trouble is that his style is also, as Dyer says, “catching, highly infectious.” And if, even from Wallace, the aw-shucks, I-could-be-wrong-here, I’m-just-a-supersincere-regular-guy-who-happens-to-have-written-a-book-on-infinity approach grates, it is vastly more exasperating in the hands of lesser thinkers. In the Internet era, Wallace’s moves have been adopted and further slackerized by a legion of opinion-mongers who not only lack his quick mind but seem not to have mastered the idea that to make an argument, you must, amid all the tap-dancing and hedging, actually lodge an argument.

Visit some blogs — personal blogs, academic blogs, blogs associated with some of our most esteemed periodicals — to see these tendencies writ large. My own archives, dating back to 2002, are no exception.

I suppose it made sense, when blogging was new, that there was some confusion about voice. Was a blog more like writing or more like speech? Soon it became a contrived and shambling hybrid of the two. The “sort ofs” and “reallys” and “ums” and “you knows” that we use in conversation were codified as the central connectors in the blogger lexicon. We weren’t just mad, we were sort of enraged; no one was merely confused, but kind of totally mystified. That music blog we liked was really pretty much the only one that, um, you know, got it. Never before had “folks” been used so relentlessly and enthusiastically as a term of general address outside church suppers, chain restaurants and family reunions. It’s fascinating and dreadful in hindsight to realize how quickly these conventions took hold and how widely they spread. And! They have sort of mutated since to liberal and often sarcastic use of question marks? And exclamation points! “Oh, hi,” people say at the start of sentences on blogs, Twitter and Tumblr these days, both acknowledging and jokily feigning surprise at the presence of the readers who have turned up there.

Wallace isn’t responsible for his imitators, much less for the stylized mess that is Gen-X-and-Y Internet syntax. The devices can be traced back to him, though, if indirectly; they were filtered through and popularized by Dave Eggers’s literary magazine and publishing empire, McSweeney’s, and Eggers’s own novels and memoirs, all of which borrowed not only Wallace’s tics but also his championing of post-ironic sincerity and his attempts to ward off criticism by embedding all possible criticisms within the writing itself. “There is no overwhelming need to read the preface,” Eggers wrote in “A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius”; in fact, after “the first three or four chapters” the book “is kind of uneven.”