An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Leadership Effectiveness in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional and Before–After Studies

Vincenzo restivo, giuseppa minutolo, alberto battaglini, alberto carli, michele capraro, maddalena gaeta, cecilia trucchi, carlo favaretti, francesco vitale, alessandra casuccio.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected] ; Tel.: +39-3200804278

Received 2022 Jul 12; Accepted 2022 Aug 28; Collection date 2022 Sep.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

To work efficiently in healthcare organizations and optimize resources, team members should agree with their leader’s decisions critically. However, nowadays, little evidence is available in the literature. This systematic review and meta-analysis has assessed the effectiveness of leadership interventions in improving healthcare outcomes such as performance and guidelines adherence. Overall, the search strategies retrieved 3,155 records, and 21 of them were included in the meta-analysis. Two databases were used for manuscript research: PubMed and Scopus. On 16th December 2019 the researchers searched for articles published in the English language from 2015 to 2019. Considering the study designs, the pooled leadership effectiveness was 14.0% (95%CI 10.0–18.0%) in before–after studies, whereas the correlation coefficient between leadership interventions and healthcare outcomes was 0.22 (95%CI 0.15–0.28) in the cross-sectional studies. The multi-regression analysis in the cross-sectional studies showed a higher leadership effectiveness in South America (β = 0.56; 95%CI 0.13, 0.99), in private hospitals (β = 0.60; 95%CI 0.14, 1.06), and in medical specialty (β = 0.28; 95%CI 0.02, 0.54). These results encourage the improvement of leadership culture to increase performance and guideline adherence in healthcare settings. To reach this purpose, it would be useful to introduce a leadership curriculum following undergraduate medical courses.

Keywords: leadership effectiveness, healthcare settings, healthcare workers, private healthcare setting, public hospital, before–after, cross-sectional, leadership style

1. Introduction

Over the last years, patients’ outcomes, population wellness and organizational standards have become the main purposes of any healthcare structure [ 1 ]. These standards can be achieved following evidence-based practice (EBP) for diseases prevention and care [ 2 , 3 ] and optimizing available economical and human resources [ 3 , 4 ], especially in low-industrialized geographical areas [ 5 ]. This objective could be reached with effective healthcare leadership [ 3 , 4 ], which could be considered a network whose team members followed leadership critically and motivated a leader’s decisions based on the organization’s requests and targets [ 6 ]. Healthcare workers raised their compliance towards daily activities in an effective leadership context, where the leader succeeded in improving membership and performance awareness among team members [ 7 ]. Furthermore, patients could improve their health conditions in a high-level leadership framework. [ 8 ] Despite the leadership benefits for healthcare systems’ performance and patients’ outcomes [ 1 , 7 ], professionals’ confidence would decline in a damaging leadership context for workers’ health conditions and performance [ 4 , 9 , 10 ]. On the other hand, the prevention of any detrimental factor which might worsen both team performance and healthcare systems’ outcomes could demand effective leadership [ 4 , 7 , 10 ]. However, shifting from the old and assumptive leadership into a more effective and dynamic one is still a challenge [ 4 ]. Nowadays, the available evidence on the impact and effectiveness of leadership interventions is sparse and not systematically reported in the literature [ 11 , 12 ].

Recently, the spreading of the Informal Opinion Leadership style into hospital environments is changing the traditional concept of leadership. This leadership style provides a leader without any official assignment, known as an “opinion leader”, whose educational and behavioral background is suitable for the working context. Its target is to apply the best practices in healthcare creating a more familiar and collaborative team [ 2 ]. However, Flodgren et al. reported that informal leadership interventions increased healthcare outcomes [ 2 ].

Nowadays, various leadership styles are recognized with different classifications but none of them are considered the gold standard for healthcare systems because of heterogenous leadership meanings in the literature [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 , 13 ]. Leadership style classification by Goleman considered leaders’ behavior [ 5 , 13 ], while Chen DS-S proposed a traditional leadership style classification (charismatic, servant, transactional and transformational) [ 6 ].

Even if leadership style improvement depends on the characteristics and mission of a workplace [ 6 , 13 , 14 ], a leader should have both a high education in healthcare leadership and the behavioral qualities necessary for establishing strong human relationships and achieving a healthcare system’s goals [ 7 , 15 ]. Theoretically, any practitioner could adapt their emotive capacities and educational/working experiences to healthcare contexts, political lines, economical and human resources [ 7 ]. Nowadays, no organization adopts a policy for leader selection in a specific healthcare setting [ 15 ]. Despite the availability of a self-assessment leadership skills questionnaire for aspirant leaders and a pattern for the selection of leaders by Dubinsky et al. [ 15 ], a standardized and universally accepted method to choose leaders for healthcare organizations is still argued over [ 5 , 15 ].

Leadership failure might be caused by the arduous application of leadership skills and adaptive characteristics among team members [ 5 , 6 ]. One of the reasons for this negative event could be the lack of a standardized leadership program for medical students [ 16 , 17 ]. Consequently, working experience in healthcare settings is the only way to apply a leadership style for many medical professionals [ 12 , 16 , 17 ].

Furthermore, the literature data on leadership effectiveness in healthcare organizations were slightly significant or discordant in results. Nevertheless, the knowledge of pooled leadership effectiveness should motivate healthcare workers to apply leadership strategies in healthcare systems [ 12 ]. This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses the pooled effectiveness of leadership interventions in improving healthcare workers’ and patients’ outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement guidelines [ 18 ]. The protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database with code CRD42020198679 on 15 August 2020. Following these methodological standards, leadership interventions were evaluated as the pooled effectiveness and influential characteristic of healthcare settings, such as leadership style, workplace, settings and the study period.

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

PubMed and Scopus were the two databases used for the research into the literature. On 16th December 2019, manuscripts in the English language published between 2015 and 2019 were searched by specific MeSH terms for each dataset. Those for PubMed were “leadership” OR “leadership” AND “clinical” AND “outcome” AND “public health” OR “public” AND “health” OR “public health” AND “humans”. Those for Scopus were “leadership” AND “clinical” AND “outcome” AND “public” AND “health”.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

In accordance with the PRISMA Statement, the following PICOS method was used for including articles [ 18 ]: the target population was all healthcare workers in any hospital or clinical setting (Population); the interventions were any leader’s recommendation to fulfil quality standards or performance indexes of a healthcare system (Intervention) [ 19 ]; to be included, the study should have a control group or reference at baseline as comparison (Control); and any effectiveness measure in terms of change in adherence to healthcare guidelines or performances (Outcome). In detail, any outcome implicated into healthcare workers’ capacity and characteristics in reaching a healthcare systems purposes following the highest standards was considered as performance [ 19 ]. Moreover, whatever clinical practices resulted after having respected the recommendations, procedures or statements settled previously was considered as guideline adherence [ 20 ]. The selected study design was an observational or experimental/quasi-experimental study design (trial, case control, cohort, cross-sectional, before-after study), excluding any systematic reviews, metanalyses, study protocol and guidelines (Studies).

The leaders’ interventions followed Chen’s leadership styles classification [ 6 ]. According to this, the charismatic leadership style can be defined also as an emotive leadership because of members’ strong feelings which guide the relationship with their leader. Its purpose is the improvement of workers’ motivation to reach predetermined organizational targets following a leader’s planning strategies and foresights. Servant leadership style is a sharing leadership style in whose members can increase their skills and competences through steady leader support, and they have a role in an organization’s goals. The transformational leadership style focuses on practical aspects such as new approaches for problem solving, new interventions to reach purposes, future planning and viewpoints sharing. Originality in a transformational leadership style has a key role of improving previous workers’ and healthcare system conditions in the achievement of objectives. The transactional leadership style requires a working context where technical skills are fundamental, and whose leader realizes a double-sense sharing process of knowledge and tasks with members. Furthermore, workers’ performances are improved through a rewarding system [ 6 ].

In this study, the supervisor trained the research team for practical manuscript selection and data extraction. The aim was to ensure data homogeneity and to check the authors’ procedures for selection and data collection. The screening phase was performed by four researchers reading each manuscript’s title and abstract independently and choosing to exclude any article that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. Afterwards, the included manuscripts were searched for in the full text. They were retrieved freely, by institutional access or requesting them from the authors.

The assessment phase consisted of full-text reading to select articles following the inclusion criteria. The supervisor solved any contrasting view about article selection and variable selection.

The final database was built up by collecting the information from all included full-text articles: author, title, study year, year of publication, country/geographic location, study design, viability and type of evaluation scales for leadership competence, study period, type of intervention to improve leadership awareness, setting of leader intervention, selection modality of leaders, leadership style adopted, outcomes assessed such as guideline adherence or healthcare workers’ performance, benefits for patients’ health or patients’ outcomes improvement, public or private hospitals or healthcare units, ward specialty, intervention in single specialty or multi-professional settings, number of beds, number of healthcare workers involved in leadership interventions and sample size.

Each included article in this systematic review and meta-analysis received a standardized quality score for the specific study design, according to Newcastle–Ottawa, for the assessment of the quality of the cross-sectional study, and the Study Quality Assessment Tools by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute were used for all other study designs [ 21 , 22 ].

2.3. Statistical Data Analysis

The manuscripts metadata were extracted in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to remove duplicate articles and collect data. The included article variables for the quantitative meta-analysis were: first author, publication year, continent of study, outcome, public or private organization, hospital or local healthcare unit, surgical or non-surgical ward, multi- or single-professionals, ward specialty, sample size, quality score of each manuscript, leadership style, year of study and study design.

The measurement of the outcomes of interest (either performance or guidelines adherence) depended on the study design of the included manuscripts in the meta-analysis:

for cross-sectional studies, the outcome of interest was the correlation between leadership improvement and guideline adherence or healthcare performance;

the outcome derived from before–after studies or the trial was the percentage of leadership improvement intervention in guideline adherence or healthcare performance;

the incidence occurrence of improved results among exposed and not exposed healthcare workers of leadership interventions and the relative risks (RR) were the outcomes in cohort studies;

the odds ratio (OR) between the case of healthcare workers who had received a leadership intervention and the control group for case-control studies.

Pooled estimates were calculated using both the fixed effects and DerSimonian and Laird random effects models, weighting individual study results by the inverse of their variances [ 23 ]. Forest plots assessed the pooled estimates and the corresponding 95%CI across the studies. The heterogeneity test was performed by a chi-square test at a significance level of p < 0.05, reporting the I 2 statistic together with a 25%, 50% or 75% cut-off, indicating low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [ 24 , 25 ].

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression analyses explored the sources of significant heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis considered the leadership style (charismatic, servant, transactional and transformational), continent of study (North America, Europe, Oceania), median cut-off year of study conduction (studies conducted between 2005 and 2011 and studies conducted between 2012 and 2019), type of hospital organization (public or private hospital), type of specialty (surgical or medical specialty) and type of team (multi-professional or single-professional team).

Meta-regression analysis considered the following variables: year of starting study, continent of study conduction, public or private hospital, surgical or non-surgical specialty ward, type of healthcare service (hospital or local health unit), type of healthcare workers involved (multi- or single-professional), leadership style, and study quality score. All variables included in the model were relevant in the coefficient analysis.

To assess a potential publication bias, a graphical funnel plot reported the logarithm effect estimate and related the standard error from each study, and the Egger test was performed [ 26 , 27 ].

All data were analyzed using the statistical package STATA/SE 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College 482 Station, TX, USA), with the “metan” command used for meta-analysis, and “metafunnel”, “metabias” and “confunnel” for publication bias assessment [ 28 ].

3.1. Studies Characteristics

Overall, the search strategies retrieved 3,155 relevant records. After removing 570 (18.1%) duplicates, 2,585 (81.9%) articles were suitable for the screening phase, of which only 284 (11.0%) articles were selected for the assessment phase. During the assessment phase, 263 (92.6%) articles were excluded. The most frequent reasons of exclusion were the absence of relevant outcomes ( n = 134, 51.0%) and other study designs ( n = 61, 23.2%). Very few articles were rejected due to them being written in another language ( n = 1, 0.4%), due to the publication year being out of 2015–2019 ( n = 1, 0.4%) or having an unavailable full text ( n = 3, 1.1%).

A total of 21 (7.4%) articles were included in the qualitative and quantitative analysis, of which nine (42.9%) were cross-sectional studies and twelve (57.1%) were before and after studies ( Figure 1 ).

Flow-chart of selection manuscript phases for systematic review and meta-analysis on leadership effectiveness in healthcare workers.

The number of healthcare workers enrolled was 25,099 (median = 308, IQR = 89–1190), including at least 2,275 nurses (9.1%, median = 324, IQR = 199–458). Most of the studies involved a public hospital ( n = 16, 76.2%). Among the studies from private healthcare settings, three (60.0%) were conducted in North America. Articles which analyzed servant and charismatic leadership styles were nine (42.9%) and eight (38.1%), respectively. Interventions with a transactional leadership style were examined in six (28.6%) studies, while those with a transformational leadership style were examined in five studies (23.8%). Overall, 82 healthcare outcomes were assessed and 71 (86.6%) of them were classified as performance. Adherence-to-guidelines outcomes were 11 (13.4%), which were related mainly to hospital stay ( n = 7, 64.0%) and drug administration ( n = 3, 27.0%). Clements et al. and Lornudd et al. showed the highest number of outcomes, which were 19 (23.2%) and 12 (14.6%), respectively [ 29 , 30 ].

3.2. Leadership Effectiveness in before–after Studies

Before–after studies ( Supplementary Table S1 ) involved 22,241 (88.6%, median = 735, IQR = 68–1273) healthcare workers for a total of twelve articles, of which six (50.0%) consisted of performance and five (41.7%) of guidelines adherence and one (8.3%) of both outcomes. Among healthcare workers, there were 1,294 nurses (5.8%, median = 647, IQR = 40–1,254). Only the article by Savage et al. reported no number of involved healthcare workers [ 31 ].

The number of studies conducted after 2011 or between 2012–2019 was seven (58.3%), while only one (8.3%) article reported a study beginning both before and after 2011. Most of studies were conducted in Northern America ( n = 5, 41.7%). The servant leadership style and charismatic leadership style were the most frequently implemented, as reported in five (41.7%) and four (33.3%) articles, respectively. Only one (8.3%) study adopted a transformational leadership style.

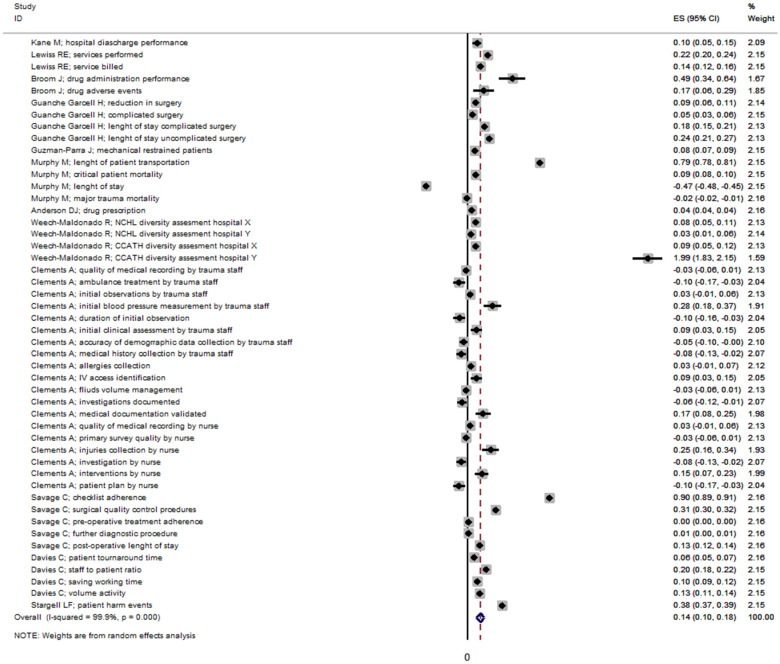

The pooled effectiveness of leadership was 14.0% (95%CI 10.0–18.0%), with a high level of heterogeneity (I 2 = 99.9%, p < 0.0001) among the before–after studies ( Figure 2 ).

Effectiveness of leadership in before after studies. Dashed line represents the pooled effectiveness value [ 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ].

The highest level of effectiveness was reported by Weech-Maldonado R et al. with an effectiveness of 199% (95%CI 183–215%) based on the Cultural Competency Assessment Tool for Hospitals (CCATH) [ 39 ]. The effectiveness of leadership changed in accordance with the leadership style ( Supplementary Figure S1 ) and publication bias ( Supplementary Figure S2 ).

Multi-regression analysis indicated a negative association between leadership effectiveness and studies from Oceania, but this result was not statistically significant (β = −0.33; 95% IC −1.25, 0.59). On the other hand, a charismatic leadership style affected healthcare outcomes positively even if it was not statistically relevant (β = 0.24; 95% IC −0.69, 1.17) ( Table 1 ).

Correlation coefficients and multi-regression analysis of leadership effectiveness in before–after studies.

| Variables | Correlation Coefficient | Beta Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies conducted between 2012–2019 vs. 2005–2011 years | −0.26 | −0.09 | −0.42 | 0.24 |

| North American continent vs. others | 0.27 | −0.04 | −0.82 | 0.75 |

| Oceanian continent vs. others | −0.26 | −0.33 | −1.25 | 0.59 |

| European continent vs. others | 0.07 | −0.27 | −1.12 | 0.58 |

| Public hospital vs. private hospital | 0.01 | |||

| Surgical specialty vs. non-surgical specialty | −0.21 | −0.05 | −0.85 | 0.75 |

| Leadership style transformational vs. other styles | 0.12 | 0.32 | −0.47 | 1.11 |

| Leadership style charismatic vs. other styles | −0.23 | 0.24 | −0.69 | 1.17 |

| Leadership style transactional vs. other styles | 0.25 | 0.25 | −0.40 | 0.91 |

3.3. Leadership Effectiveness in Cross Sectional Studies

A total of 2858 (median = 199, IQR = 110–322) healthcare workers were involved in the cross-sectional studies ( Supplementary Table S2 ), of which 981 (34.3%) were nurses. Most of the studies were conducted in Asia ( n = 4, 44.4%) and North America ( n = 3, 33.3%). All of the cross-sectional studies regarded only the healthcare professionals’ performance. Multi-professional teams were involved in seven (77.8%) studies, and they were more frequently conducted in both medical and surgical wards ( n = 6, 66.7%). The leadership styles were equally distributed in the articles and two (22.2%) of them examined more than two leadership styles at the same time.

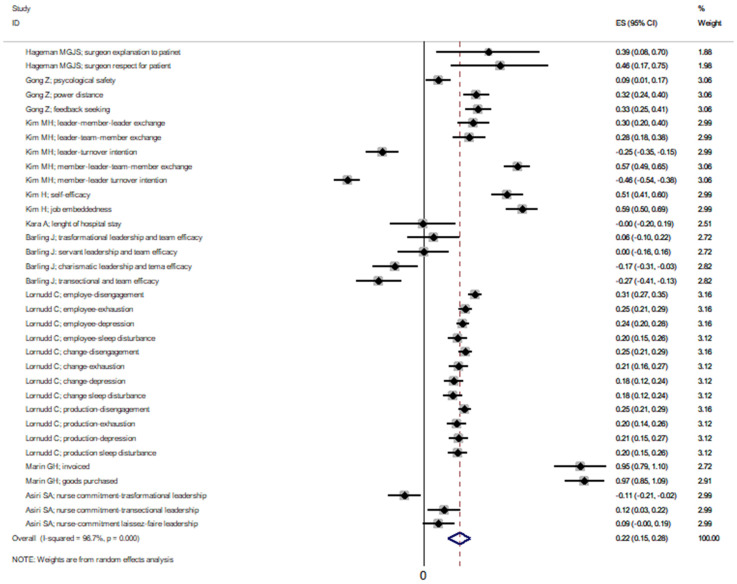

The pooled effectiveness of the leadership interventions in the cross-sectional studies had a correlation coefficient of 0.22 (95%CI 0.15–0.28), whose heterogeneity was remarkably high (I 2 = 96.7%, p < 0.0001) ( Figure 3 ).

Effectiveness of leadership in cross-sectional studies. Dashed line represents the pooled effectiveness value [ 30 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ].

The effectiveness of leadership in the cross-sectional studies changed in accordance with the leadership style ( Supplementary Figure S3 ) and publication bias ( Supplementary Figure S4 ).

Multi-regression analysis showed a higher leadership effectiveness in studies conducted in South America (β = 0.56 95%CI 0.13–0.99) in private hospitals (β = 0.60; 95%CI 0.14–1.06) and in the medical vs. surgical specialty (β = −0.22; 95%CI −0.54, −0.02) ( Table 2 ).

Multi-regression analysis of leadership effectiveness in cross-sectional studies.

| Variables | Correlation Coefficient | Beta Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies conducted between 2012–2019 vs. 2005–2011 years | −0.31 | −0.09 | −0.27 | 0.10 |

| South American continent vs. others | 0.63 | 0.56 * | 0.13 | 0.99 |

| Private hospital vs. public hospital | 0.17 | 0.60 * | 0.14 | 1.06 |

| Surgical specialty vs. non-surgical specialty | −0.22 | −0.28 * | −0.54 | −0.02 |

| Leadership style transformational vs. other styles | 0.41 | 0.16 | −0.14 | 0.46 |

| Leadership style charismatic vs. other styles | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.26 | 0.18 |

| Leadership style transactional vs. other styles | −0.11 | 0.01 | −0.21 | 0.23 |

| Multiprofessional team vs. single professional team | 0.04 | |||

* 0.05 ≤ p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

Leadership effectiveness in healthcare settings is a topic that is already treated in a quantitative matter, but only this systematic review and meta-analysis showed the pooled effectiveness of leadership intervention improving some healthcare outcomes such as performance and adherence to guidelines. However, the assessment of leadership effectiveness could be complicated because it depends on the study methodology and selected outcomes [ 12 ]. Health outcomes might benefit from leadership interventions, as Flodgren et al. was concerned about opinion leadership [ 2 ], whose adhesion to guidelines increased by 10.8% (95% CI: 3.5–14.6%). On the other hand, other outcomes did not improve after opinion leadership interventions [ 2 ]. Another review by Ford et al. about emergency wards reported a summary from the literature data which acknowledged an improvement in trauma care management through healthcare workers’ performance and adhesion to guidelines after effective leadership interventions [ 14 ]. Nevertheless, some variables such as collaboration among different healthcare professionals and patients’ healthcare needs might affect leadership intervention effectiveness [ 14 ]. Therefore, a defined leadership style might fail in a healthcare setting rather than in other settings [ 5 , 13 , 14 ].

The leadership effectiveness assessed through cross-sectional studies was higher in South America than in other continents. A possible explanation of this result could be the more frequent use of a transactional leadership style in this area, where the transactional leadership interventions were effective at optimizing economic resources and improving healthcare workers’ performance through cash rewards [ 48 ]. Financing methods for healthcare organizations might be different from one country to another, so the effectiveness of a leadership style can change. Reaching both economic targets and patients’ wellness could be considered a challenge for any leadership intervention [ 48 ], especially in poorer countries [ 5 ].

This meta-analysis showed a negative association between leadership effectiveness and studies by surgical wards. Other research has supported these results, which reported surgical ward performance worsened in any leadership context (charismatic, servant, transactional, transformational) [ 47 ]. In those workplaces, adopting a leadership style to improve surgical performance might be challenging because of nervous tension and little available time during surgical procedures [ 47 ]. On the other hand, a cross-sectional study declared that a surgical team’s performance in private surgical settings benefitted from charismatic leadership-style interventions [ 42 ]. This style of leadership intervention might be successful among a few healthcare workers [ 42 ], where creating relationships is easier [ 6 ]. Even a nursing team’s performance in trauma care increased after charismatic leadership-style interventions because of better communicative and supportive abilities than certain other professional categories [ 29 , 47 ]. However, nowadays there is no standardized leadership in healthcare basic courses [ 5 , 6 , 12 ]. Consequently, promoting leadership culture after undergraduate medical courses could achieve a proper increase in both leadership agreement and working wellness as well as a higher quality of care. [ 17 ]. Furthermore, for healthcare workers who have already worked in a healthcare setting, leadership improvement could consist of implementing basic knowledge on that topic. Consequently, they could reach a higher quality of care practice through working wellness [ 17 ] and overcoming the lack of previous leadership training [ 17 ].

Although very few studies have included in a meta-analysis examined in private healthcare settings [ 35 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], leadership interventions had more effectiveness in private hospitals than in public hospitals. This result could be related to the continent of origin, and indeed 60.0% of these studies were derived from North America [ 38 , 41 , 42 ], where patients’ outcomes and healthcare workers’ performance could influence available hospital budgets [ 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], especially in peripheral healthcare units [ 38 , 41 ]. Private hospitals paid more attention to the cost-effectiveness of any healthcare action and a positive balance of capital for healthcare settings might depend on the effectiveness of leadership interventions [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Furthermore, private healthcare assistance focused on nursing performance because of its impact on both a patients’ and an organizations’ outcomes. Therefore, healthcare systems’ quality could improve with effective leadership actions for a nursing team [ 40 ].

Other factors reported in the literature could affect leadership effectiveness, although they were not examined in this meta-analysis. For instance, professionals’ specialty and gender could have an effect on these results and shape leadership style choice and effectiveness [ 1 ]. Moreover, racial differences among members might influence healthcare system performance. Weech-Maldonado et al. found a higher compliance and self-improvement by black-race professionals than white ones after transactional leadership interventions [ 39 ].

Healthcare workers’ and patients’ outcomes depended on style of leadership interventions [ 1 ]. According to the results of this meta-analysis, interventions conducted by a transactional leadership style increased healthcare outcomes, though nevertheless their effectiveness was higher in the cross-sectional studies than in the before–after studies. Conversely, the improvement by a transformational leadership style was higher in before–after studies than in the cross-sectional studies. Both a charismatic and servant leadership style increased effectiveness more in the cross-sectional studies than in the before–after studies. This data shows that any setting required a specific leadership style for improving performance and guideline adherence by each team member who could understand the importance of their role and their tasks [ 1 ]. Some outcomes had a better improvement than others. Focusing on Savage et al.’s outcomes, a transformational leadership style improved checklist adherence [ 31 ]. The time of patients’ transport by Murphy et al. was reduced after conducting interventions based on a charismatic leadership style [ 37 ]. Jodar et al. showed that performances were elevated in units whose healthcare workers were subjected to transactional and transformational leadership-style interventions [ 1 ].

These meta-analysis results were slightly relevant because of the high heterogeneity among the studies, as confirmed by both funnel plots. This publication bias might be caused by unpublished articles due to either lacking data on leadership effectiveness, failing appropriate leadership strategies in the wrong settings or non-cooperating teams [ 12 ]. The association between leadership interventions and healthcare outcomes was slightly explored or gave no statistically significant results [ 12 ], although professionals’ performance and patients’ outcomes were closely related to the adopted leadership style, as reported by the latest literature sources [ 7 ]. Other aspects than effectiveness should be investigated for leadership. For example, the evaluation of the psychological effect of leadership should be explored using other databases.

The study design choice could affect the results about leadership effectiveness, making their detection and their statistical relevance tough [ 12 ]. Despite the strongest evidence of this study design [ 50 ], nowadays, trials about leadership effectiveness on healthcare outcomes are lacking and have to be improved [ 12 ]. Notwithstanding, this analysis gave the first results of leadership effectiveness from the available study designs.

Performance and adherence to guidelines were the main two outcomes examined in this meta-analysis because of their highest impact on patients, healthcare workers and hospital organizations. They included several other types of outcomes which were independent each other and gave different effectiveness results [ 12 ]. The lack of neither an official classification nor standardized guidelines explained the heterogeneity of these outcomes. To reach consistent results, they were classified into performance and guideline adherence by the description of each outcome in the related manuscripts [ 5 , 6 , 12 ].

Another important aspect is outcome assessment after leadership interventions, which might be fulfilled by several standardized indexes and other evaluation methods [ 40 , 41 ]. Therefore, leadership interventions should be investigated in further studies [ 5 ], converging on a univocal and official leadership definition and classification to obtain comparable results among countries [ 5 , 6 , 12 ].

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis gave the first pooled data estimating leadership effectiveness in healthcare settings. However, some of them, e.g., surgery, required a dedicated approach to select the most worthwhile leadership style for refining healthcare worker performances and guideline adhesion. This can be implemented using a standardized leadership program for surgical settings.

Only cross-sectional studies gave significant results in leadership effectiveness. For this reason, leadership effectiveness needs to be supported and strengthened by other study designs, especially those with the highest evidence levels, such as trials. Finally, further research should be carried out to define guidelines on leadership style choice and establish shared healthcare policies worldwide.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph191710995/s1 , Figure S1. Leadership effectiveness by leadership style in before after studies; Figure S2. Funnel plot of before after studies; Figure S3. Leadership effectiveness in cross sectional studies by four leadership style; Figure S4. Funnel plot of cross-sectional studies; Table S1. Before after studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis; Table S2. Cross-sectional studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. All outcomes were performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R., A.C. (Alessandra Casuccio), F.V. and C.F.; methodology, V.R., M.G., A.O. and C.T.; software, V.R.; validation, G.M., A.B., A.C. (Alberto Carli) and M.C.; formal analysis, V.R.; investigation, G.M., A.B., A.C. (Alberto Carli) and M.C.; resources, A.C. (Alessandra Casuccio); data curation, G.M. and V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.; writing—review and editing, A.C. (Alessandra Casuccio), F.V., C.F., M.G., A.O., C.T., A.B., A.C. (Alberto Carli) and M.C.; visualization, G.M.; supervision, V.R.; project administration, C.F.; funding acquisition, A.C. (Alessandra Casuccio), F.V. and C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to secondary data analysis for the systematic review and meta-anlysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available after writing correspondence to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Solà G.J.I., Badia J.G.I., Hito P.D., Osaba M.A.C., Del Val García J.L. Self-Perception of Leadership Styles and Behaviour in Primary Health Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16:572. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1819-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Flodgren G., O’Brien M.A., Parmelli E., Grimshaw J.M. Local Opinion Leaders: Effects on Professional Practice and Healthcare Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;6:CD000125. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000125.pub5. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Galaviz K.I., Narayan K.M.V., Manders O.C., Torres-Mejía G., Goenka S., McFarland D.A., Reddy K.S., Lozano R., Valladares L.M., Prabhakaran D., et al. The Public Health Leadership and Implementation Academy for Noncommunicable Diseases. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2019;16:E49. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180517. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Kumar R.D.C., Khiljee N. Leadership in Healthcare. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2016;17:63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mpaic.2015.10.012. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Chigudu S., Jasseh M., d’Alessandro U., Corrah T., Demba A., Balen J. The Role of Leadership in People-Centred Health Systems: A Sub-National Study in The Gambia. Health Policy Plan. 2014;33:e14–e25. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu078. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Chen D.S.-S. Leadership Styles and Organization Structural Configurations. J. Hum. Resour. Adult Learn. 2006;2:39–46. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Denis J.-L., van Gestel N. Medical Doctors in Healthcare Leadership: Theoretical and Practical Challenges. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16:158. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1392-8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Mutale W., Vardoy-Mutale A.-T., Kachemba A., Mukendi R., Clarke K., Mulenga D. Leadership and Management Training as a Catalyst to Health System Strengthening in Low-Income Settings: Evidence from Implementation of the Zambia Management and Leadership Course for District Health Managers in Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174536. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Braun S., Kark R., Wisse B. Editorial: Fifty Shades of Grey: Exploring the Dark Sides of Leadership and Followership. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1877. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01877. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Fatima T., Majeed M., Shah S.Z.A. Jeopardies of Aversive Leadership: A Conservation of Resources Theory Approach. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1935. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01935. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Abraham T.H., Stewart G.L., Solimeo S.L. The Importance of Soft Skills Development in a Hard Data World: Learning from Interviews with Healthcare Leaders. BMC Med. Educ. 2021;21:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02567-1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Ovretveit J. Improvement Leaders: What Do They and Should They Do? A Summary of a Review of Research. Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2010;19:490–492. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.041772. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Saxena A., Desanghere L., Stobart K., Walker K. Goleman’s Leadership Styles at Different Hierarchical Levels in Medical Education. BMC Med. Educ. 2017;17:169. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0995-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Ford K., Menchine M., Burner E., Arora S., Inaba K., Demetriades D., Yersin B. Leadership and Teamwork in Trauma and Resuscitation. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2016;17:549–556. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.7.29812. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dubinsky I., Feerasta N., Lash R. A Model for Physician Leadership Development and Succession Planning. Healthc. Q. Tor. Ont. 2015;18:38–42. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2015.24245. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Stahlhut R.W., Porterfield D.S., Grande D.R., Balan A. Characteristics of Population Health Physicians and the Needs of Healthcare Organizations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021;60:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.016. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Quince T., Abbas M., Murugesu S., Crawley F., Hyde S., Wood D., Benson J. Leadership and Management in the Undergraduate Medical Curriculum: A Qualitative Study of Students’ Attitudes and Opinions at One UK Medical School. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005353. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005353. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Sertel G., Karadag E., Ergin-Kocatürk H. Effects of Leadership on Performance: A Cross-Cultural Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2022;22:59–82. doi: 10.1177/14705958221076404. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Hunziker S., Johansson A.C., Tschan F., Semmer N.K., Rock L., Howell M.D., Marsch S. Teamwork and Leadership in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;57:2381–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.017. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Wells G., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. ScienceOpen, Inc.; Burlington, MA, USA: 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with No Control Group Study Quality Assessment Tools|NHLBI, NIH. [(accessed on 10 March 2021)]; Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools .

- 23. DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Trials. Control. Clin. Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Fleiss J.L. The Statistical Basis of Meta-Analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1993;2:121–145. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200202. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Sterne J.A., Egger M. Funnel Plots for Detecting Bias in Meta-Analysis: Guidelines on Choice of Axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in Meta-Analysis Detected by a Simple, Graphical Test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Palmer T.M., Sterne J.A.C., editors. Meta-Analysis in Stata: An Updated Collection from the Stata Journal. 2nd ed. StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX, USA: 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Clements A., Curtis K., Horvat L., Shaban R.Z. The Effect of a Nurse Team Leader on Communication and Leadership in Major Trauma Resuscitations. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2015;23:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2014.04.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Lornudd C., Tafvelin S., von Thiele Schwarz U., Bergman D. The Mediating Role of Demand and Control in the Relationship between Leadership Behaviour and Employee Distress: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015;52:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Savage C., Gaffney F.A., Hussain-Alkhateeb L., Olsson Ackheim P., Henricson G., Antoniadou I., Hedsköld M., Pukk Härenstam K. Safer Paediatric Surgical Teams: A 5-Year Evaluation of Crew Resource Management Implementation and Outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Health Care J. Int. Soc. Qual. Health Care. 2017;29:853–860. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzx113. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Kane M., Weinacker A., Arthofer R., Seay-Morrison T., Elfman W., Ramirez M., Ahuja N., Pickham D., Hereford J., Welton M. A Multidisciplinary Initiative to Increase Inpatient Discharges Before Noon. J. Nurs. Adm. 2016;46:630–635. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000418. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Lewiss R.E., Cook J., Sauler A., Avitabile N., Kaban N.L., Rabrich J., Saul T., Siadecki S.D., Wiener D. A Workflow Task Force Affects Emergency Physician Compliance for Point-of-Care Ultrasound Documentation and Billing. Crit. Ultrasound. J. 2016;8:5. doi: 10.1186/s13089-016-0041-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Broom J., Tee C.L., Broom A., Kelly M.D., Scott T., Grieve D.A. Addressing Social Influences Reduces Antibiotic Duration in Complicated Abdominal Infection: A Mixed Methods Study. ANZ J. Surg. 2019;89:96–100. doi: 10.1111/ans.14414. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Guanche Garcell H., Valle Gamboa M.E., Guelmes Dominguez A.A., Hernández Hernandez E., Bode Sado A., Alfonso Serrano R.N. Effect of a Quality Improvement Intervention to Reduce the Length of Stay in Appendicitis. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2019;34:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jhqr.2019.05.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Guzman-Parra J., Aguilera Serrano C., García-Sánchez J.A., Pino-Benítez I., Alba-Vallejo M., Moreno-Küstner B., Mayoral-Cleries F. Effectiveness of a Multimodal Intervention Program for Restraint Prevention in an Acute Spanish Psychiatric Ward. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2016;22:233–241. doi: 10.1177/1078390316644767. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Murphy M., McCloughen A., Curtis K. The Impact of Simulated Multidisciplinary Trauma Team Training on Team Performance: A Qualitative Study. Australas. Emerg. Care. 2019;22:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2018.11.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Anderson D.J., Watson S., Moehring R.W., Komarow L., Finnemeyer M., Arias R.M., Huvane J., Bova Hill C., Deckard N., Sexton D.J., et al. Feasibility of Core Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions in Community Hospitals. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2:e199369. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9369. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Weech-Maldonado R., Dreachslin J.L., Epané J.P., Gail J., Gupta S., Wainio J.A. Hospital Cultural Competency as a Systematic Organizational Intervention: Key Findings from the National Center for Healthcare Leadership Diversity Demonstration Project. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2018;43:30–41. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000128. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Davies C., Lyons C., Whyte R. Optimizing Nursing Time in a Day Care Unit: Quality Improvement Using Lean Six Sigma Methodology. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2019;31((Suppl. S1)):22–28. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzz087. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Stargell L.F., Heatherly S.L. Managing What Is Measured: A Rural Hospital’s Experience in Reducing Patient Harm. J. Healthc. Qual. Off. Publ. Natl. Assoc. Healthc. Qual. 2018;40:172–176. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000139. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Hageman M.G.J.S., Ring D.C., Gregory P.J., Rubash H.E., Harmon L. Do 360-Degree Feedback Survey Results Relate to Patient Satisfaction Measures? Clin. Orthop. 2015;473:1590–1597. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3981-3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Gong Z., Van Swol L., Xu Z., Yin K., Zhang N., Gul Gilal F., Li X. High-Power Distance Is Not Always Bad: Ethical Leadership Results in Feedback Seeking. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:2137. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02137. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Kim M.-H., Yi Y.-J. Impact of Leader-Member-Exchange and Team-Member-Exchange on Nurses’ Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019;66:242–249. doi: 10.1111/inr.12491. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Kim H., Kim K. Impact of Self-Efficacy on the Self-Leadership of Nursing Preceptors: The Mediating Effect of Job Embeddedness. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019;27:1756–1763. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12870. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Kara A., Johnson C.S., Nicley A., Niemeier M.R., Hui S.L. Redesigning Inpatient Care: Testing the Effectiveness of an Accountable Care Team Model. J. Hosp. Med. 2015;10:773–779. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2432. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Barling J., Akers A., Beiko D. The Impact of Positive and Negative Intraoperative Surgeons’ Leadership Behaviors on Surgical Team Performance. Am. J. Surg. 2018;215:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Marin G.H., Silberman M., Colombo M.V., Ozaeta B., Henen J. Manager’s Leadership Is the Main Skill for Ambulatory Health Care Plan Success. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2015;38:59–68. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Asiri S.A., Rohrer W.W., Al-Surimi K., Da’ar O.O., Ahmed A. The Association of Leadership Styles and Empowerment with Nurses’ Organizational Commitment in an Acute Health Care Setting: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2016;15:38. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0161-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Akl E.A., Kunz R., Vist G., Brozek J., Norris S., Falck-Ytter Y., Glasziou P., deBeer H., et al. GRADE Guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE Evidence Profiles and Summary of Findings Tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.9 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The relationship between leadership and adaptive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Economics and Management, University of Parma, Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, Department of Humanities, Social Sciences and Cultural Industries, University of Parma, Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Economics and Management, University of Parma, Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Humanities, Social Sciences and Cultural Industries, University of Parma, Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Bologna, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

- Alice Bonini,

- Chiara Panari,

- Luca Caricati,

- Marco Giovanni Mariani

- Published: October 18, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304720

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

This research presents a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of literature to examine the impact of various leadership styles on organizational adaptive performance (AP). AP is essential for job performance, especially in environments undergoing rapid changes. Previous reviews on AP found that transformational and self-leadership had had a positive influence on job adaptivity, while the relationship between other leadership styles and AP had not been clear. First, authors outlined the theoretical framework of AP and leadership, clarifying how job adaptivity and the different leadership styles are defined and discussed in the scientific literature. Subsequently four scientific databases were explored to identify studies that investigate the Leadership and AP’ relationship. 32 scientific articles and 2 conference papers were investigated for review, of which 31 were used to conduct a meta-analysis; 52 different effect sizes from 32 samples were identified for a total sample size of 11.640 people. Qualitative synthesis revealed that the influence of different leadership styles on AP depended on contextual variables and on aspects related to the nature of the work. Moreover, it was found that leadership supported AP through motivational and relational aspects. Through this meta-analysis, it was found that a significant positive relationship between leadership and AP existed ( Z r = .39, SE = .04, p < .001. 95%CI [.32, .47], r = .37). However, no differences emerged from the different leadership styles examined in the studies. This review deepens the importance of leadership as organizational factor that affect the employees’ likelihood of dealing with continuously emergent changes at work, extended the search to emerging leadership approaches to highlight the value of collective contributions, ethics, and moral and sustainable elements that could positively affect AP.

Citation: Bonini A, Panari C, Caricati L, Mariani MG (2024) The relationship between leadership and adaptive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 19(10): e0304720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304720

Editor: Faisal Shafique Butt, COMSATS University Islamabad - Wah Campus, PAKISTAN

Received: March 11, 2024; Accepted: May 17, 2024; Published: October 18, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Bonini et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data files are available from the following link https://osf.io/rz82g/ .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In order to remain competitive on the labor market, companies are increasingly requesting their human resources to be able to adapt to changes and to learn new skills. For instance, technology applied to work has been constantly evolving and requires lifelong learning efforts in the acquisition of new digital skills functional to its use [ 1 , 2 ]. Most of the scientific literature is centered around individual differences, rather than around organizational factors that can affect job adaptivity [ 3 ]. Reflecting on contextual aspects, it is possible to read leadership as an organizational resource that activates motivational processes promoting high performance, commitment, and proactive behaviors [ 4 ].

Particularly, leadership plays a crucial role in involving the worker in proactive and positive attitudes in facing change and promoting adaptive performance (AP), by way of modifying their organizational features and encouraging bottom-up initiatives, such as job crafting [ 5 – 7 ] This suggests that leadership, focused on human resources by encouraging followers’ self-determination and developing their intrinsic motivation, creates the ground to foster adaptivity [ 8 ]. Individual or group adaptation passed through the leader’s ability to reinforce collaborators’ personal skills, such as tension to results and autonomy, and the leader’s capacity to pay attention to his/her followers’ individual motivational differences and needs. Following the self-determination theory [ 9 ], transformation in collaborators occur when, the leadership contribute to satisfied their basic human psychological needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) are satisfied. In the same way, paying attention to relational dynamics helped create and maintain trust in leaders and stimulated adaptive performance by sharing and managing emotional states related to changes [ 10 ].

Despite the recognized importance of leadership in facilitating adaptive performance, the understanding of how different leadership styles specifically contribute to this dynamic remains fragmented in literature. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis are necessary to consolidate existing research, identify gaps in our knowledge, and understand the nuanced ways in which leadership can effectively foster an environment conducive to adaptability. This will enable organizations to develop more targeted strategies in leadership development, directly addressing the evolving challenges of the modern workplace.

Based on these assumptions, the primary goal of this review was to emphasize how the relationship between adaptivity to work changes and leadership had been studied as an organizational antecedent that could promote or inhibit one’s adaptive job performance. Particularly, the purpose of this study was to provide a contribution to the existing literature on adaptive performance, by conducting a systematic review and a meta-analysis that would allow for a qualitative and quantitative synthesis of the scientific evidence currently available on the relationship between leadership and AP.

The secondary aim of this review was to dig deeper into the theoretical distinction among different leadership styles, so to understand what peculiarities, differences and dimensions characterize the different styles that could potentially influence AP. So, to guide this exploration, we pose three research questions:

- RQ 1. How does leadership influence an individual’s adaptive performance?

- H1: We hypothesized a strong and positive relationship between leadership and Adaptive Performance.

- RQ2: What specific leadership styles are most effective in promoting adaptive performance among employees?

- H2: We hypothesized a different level of strength in the relationship between styles and Adaptive Performance; in particular, we hypothesized that leadership styles emphasizing members’ involvement, such as transformational leadership, emergent approaches, and members’ leadership, would be more strongly related to Adaptive Performance than control-based leadership approaches, such as transactional or directive ones (H3).

With these aims, the following sections will detail the theoretical foundations of AP and leadership, leading into a comprehensive discussion based on the systematic review and meta-analysis that synthesizes our findings on the interplay between leadership, with his styles, and AP.

We assumed that the findings could be able to help organizations understand what leadership-related strategies and tools to use to decrease change resistance and promote adaptivity.

Literature background

Adaptive performance: definition and antecedents..

The construct of AP, coined by Neal and Hesketh [ 11 ], was born to differentiate between task and contextual job performance [ 12 ] with reference to a set of behaviors that arising from a person’s ability to transfer his/her own knowledge to different contexts and to adapt to new job requirements (Allworth and Hesketh, 1999 [ 13 ]), but nowadays, it may be assumed that both the task and contextual job performance can be declined in an adaptive way [ 14 ]. Park and Park, while studying AP-related literature found that some construct definitions emphasized personal characteristics, while others focused on behavioral responses or on cognitive aspects of knowledge acquisition and skills transfer [ 5 , 15 ]. Despite these differences, all definitions considered adaptation as the implementation of behaviors in response to changing working conditions. Pulakos, in particular, proposed a multidimensional model of adaptive performance based on directly observable and measurable behaviors identifying eight dimensions, which involved task and contextual characteristics, connected with: one’s ability to deal with unpredictable and stressful work situations, managing frustration through resilience and directing one’s efforts towards functional solutions; one’s capacity to perform dynamically, taking actions in mutable situations by changing goals, priorities or actions; learning and acquiring new tasks, procedures or working methods by using past experiences to anticipate possible changes and, finally, to be creative in coping with new situations or to find new work resources and be able to adapt—cognitively, emotionally and physically—in interpersonal relationships, as well as in heterogeneous cultural and social environments [ 16 , 17 ]. All these assumptions implied that adaptive performance should be seen as a form of proactive adaptation that implies a degree of event anticipation as an effective response to change [ 11 , 18 ]. For instance, the new model of work role performance proposed by Griffin, Neal and Parker was thought of as innovative, because it was multidimensional and structured starting from insecurity and uncertainty in the work environment. The authors incorporated proficiency, adaptivity and proactivity into three different levels (individual, group and organizational), as key elements of the response to changes. This model introduced the concept of adaptivity, both individually and collectively, with reference to the degree and the way in which people cope with and support organizational changes, either individually or as members of a group and organization [ 19 ].

Many studies investigated the personal features that could influence adaptivity, whereas contextual, situational and organizational aspects remained little explored [ 13 , 20 , 21 ] In this sense, the systematic review of Park and Park [ 15 ] was one of a few studies that, in addition to highlighting individual antecedents, examined contextual and organizational AP antecedents, by emphasizing the crucial role of leadership, analyzed both at the organizational and individual levels. The authors reported that transformational leadership had an impact at the collective level, as it contributed to creating a cooperative and sharing climate that allowed for openness when solving problems in non-traditional ways and that provided the motivation for employees to make an extra effort when coping with complexity [ 22 , 23 ]. At the individual level, the authors focused on self-leadership affecting individual adaptivity at the cognitive, behavioral and emotional levels, through the development of constructive thinking and goal-achievement behaviors, as well as through planning and monitoring of adaptive strategies and, from an emotional point of view, by decreasing negative feelings towards situations and by increasing job satisfaction [ 24 – 26 ]. Also Griffin and colleagues find that leadership vison can promote behavioural changes, in particular work adaptivity and proactivity [ 21 ]. Anyway, in summary, we consider individual adaptive performance as the behavior exhibited by employees when they respond to and manage significant changes within their work environment. This includes adapting to new tasks, processes, technological advancements, and shifting roles. Adaptive performance is characterized by behaviors such as effectively learning new skills, creatively solving problems, handling unexpected situations, and successfully navigating interpersonal dynamics under change. These behaviors are essential in ensuring that individuals can continue to perform effectively in dynamic and evolving workplaces [ 16 , 17 ].

Leadership styles: Literature overview and the relationship with job adaptive performance.

Studies on leadership span from approaches that focus on a leader’s intrinsic aspects, which support the existence of personality traits that are positively related to group performance [ 27 ], to approaches that emphasize a holistic vision of leadership, where not only the characteristics of the leader him/herself are taken into consideration, but also those of the collaborators, including the nature of their professional tasks, the goals to be achieved and the overall work situation [ 28 ]. The focus of the most recent perspectives has also been on the characteristics displayed by organizational members and on the leadership process, where leaders and followers mutually influence one another. These leader-member relationships affect an organization’s outcomes, which can include efficacy and job performance [ 29 ].

Neo-charismatic theories: Transactional and transformational leadership.

Transactional and transformational theories, for example, study those leadership’s strategic aspects that affect performance efficacy. While the transactional style focuses on planning, supervision and evaluation of team members’ performance through a system of rewards and punishments, the transformational theory emphasizes a leader’s charisma as a personal quality of someone who is able to promote followers’ loyalty to the organization and to balance an individual’s wellbeing with that of the organization [ 22 , 23 , 30 , 31 ]. Since adaptivity is usually not imposed “from the top” but emerges from the bottom, transactional leaders are likely to contribute to the creation of a context that is conducive to adaptive behaviors, by clearly specifying and communicating performance expectations [ 32 ]. However, this seems to leave little executive autonomy to workers and it is the reason why there are few studies on the transactional leadership style and AP [ 33 ].

On the other hand, among contextual antecedents of AP, transformational leadership is one of the most investigated styles in literature [ 23 , 31 , 34 ]. Vera and Crossan, found that this style was particularly effective in situations of uncertainty, unpredictability and highly changing contexts, because it helped to create an organizational culture that valued adaptability and risk assumption by the members [ 35 ].

The emergent approaches: Servant, inclusive, authentic, humble and empowering leadership.

These emerging forms of leadership focus on ethical and moral aspects, interpersonal dynamics and how this relationship could translate into positive results, in relation to conformity with organizational objectives, increase in motivational aspects and pro-social behavior [ 36 ].

Servant leadership has been one of the most studied emerging leadership types [ 37 – 39 ]. Greenleaf, who was the first to develop the construct [ 40 ], argued that a servant leader has the natural predisposition to put followers’ needs before personal or organizational ones. Moreover, empathy, altruism and interest in the community are the elements that lead a servant leader’s actions [ 41 ]. The desire to help collaborators should not be confused with a servile attitude; what motivates servant leaders is their decision to put others before themselves, supporting the personal and professional growth of the latter through the exercise of leader power [ 42 ]. Concerning performance, servant leaders understand that effectiveness on performance largely depends on the degree of the followers’ involvement and motivation, and that the use of transparent, ethical and persuasive communication is functional to the enrichment of relationships and to the achievement of positive long-term results with the group [ 38 , 39 , 43 – 45 ].

Employees’ involvement is the principal feature of the inclusive leadership style [ 46 ]. Despite the difference in status, the inclusive leader is open and available, and his/her relationships with colleagues are friendly. Additionally, this type of leader values his/her colleagues’ differences, ideas and propositions; encourages them to share knowledge and expresses divergent thoughts thus contributing to consolidating the team’s sense of belonging and a safe work environment.

Accessibility, which is one of the hallmarks of authentic leadership, is representative of other forms of positive leadership, including the transformational, the servant and the ethical [ 47 , 48 ]. The authentic leader is one who has the ability to gain his/her followers’ respect by way of reliability, credibility and transparency, and he/she is functional to the establishment of an organizational culture that is based on transparency [ 48 , 49 ].

Recently the studies have focus on the concept of humility. Similarly to previous styles, the humble leadership is a collaborators-centered approach in which leader is empathic, interested in members growth, recognizing own personal limitations and appreciate collaborators contribution [ 50 ]. It is interesting to note that scholars found that this style contribute to promote the employee’ initiative both at individual and collective level, increasing proactive behaviors [ 50 – 52 ].

Finally, even if the empowering leadership focus on organizational results, this style was included in the emergent approaches because the leader creates an environment where responsibilities given to collaborators increase and where individual expression is encouraged, as well as a collaborative climate, collective decision-making and sharing of knowledge within the group [ 53 – 57 ]. For these reasons, this style is associated with positive individual and group outcomes, with an increase in group creativity as well as with adaptability and autonomy [ 53 ].

Members’ leadership: shared and self-leadership.

Companies show more interest in a multidisciplinary approach that promotes teamwork and this legalized the birth of an alternative model of leadership that, from a collective point of view, recognized the importance of the actions of all members.

Differently from leadership focused on a single figure, the leadership distributed among two or more individuals called shared leadership, is another perspective that meets the trend of a flat organizational structure, which is much less based on hierarchy and more centered on the transversality of roles and on skills’ overlapping. The core of shared leadership style is the interaction among group members and their mutual influence [ 58 , 59 ]; this social network leads them to work in a coordinated way to achieve the team’s organizational goals [ 60 ] and contribute to the improvement of complex task performance [ 58 ]. Some authors believed that group performance had improved because of shared leadership, as opposed to a single-figure leadership style [ 61 , 62 ] and that this positively affected the adaptive collective performance at the team level [ 62 ].

If the shared leadership is centered on collective and interactive dimensions, self-leadership is focused on processes of behavior monitoring, control and regulation, to achieve organizational goals [ 25 ] that allow a person to understand whether his/her performance falls within prefixed standards and help to keep his/her motivation high [ 63 ].

The principal features of leadership styles mentioned above are summarized in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304720.t001

Starting from the aforesaid assumptions, this systematic review intends to: a) explore what forms of leadership included in recent literature are considered as antecedents of adaptive performance; b) understand and deepen their relationship with adaptivity in the workplace.

Materials and methods

Search strategy.

In order to identify the relationship between leadership and adaptive performance, a comprehensive systematic literature review was conducted following Davis and colleagues recommendations for systematic review and metanalysis in social sciences [ 73 ]. To locate relevant studies, we used multiple electronic databases including Scopus, Web of Science, APA PsychINFO and Emerald Insight databases. The databased’ exploration ended in February 2024. Search keywords were “adaptive performance” OR “adaptivity” AND “leadership”, and the Boolean operators we used were OR and AND in showed search combination. The search results included articles containing the above words in the title, abstract or keywords.

To minimize the reproducibility bias and ensure that the selected articles assessed the constructs of AP and Leadership, it was decided to not use the terms of “adaptive ability”, “adaptive expertise” and “adaptability”, as synonyms of adaptive performance, because, based on previous exploratory research, it emerged that the above terms mainly referred to cognitive aspects, personality traits, skills, attitudes and individual predisposition to adaptation [ 74 , 75 ]. This review aimed to focus on behavioral aspects of adaptivity in the workplace and both adaptive performance and adaptivity terms are the constructs that best highlight the behavioral aspects that are used to cope with work changes [ 16 , 17 , 19 ]. Therefore, as previously indicated, we consider adaptive performance as behavior and not from an ability perspective.

Eligibility criteria

The research team agreed into locate and select the studies that investigated the relationship between AP and leadership and that had been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Since the term “adaptive performance” appeared for the first time in 1999 [ 13 ], no restrictions on the year of publication were placed; furthermore, all the articles were relatively recent and none of the selected articles had a publication year prior to 2010. To select the studies to include in this review, researchers decided to follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA statements) guidelines [ 76 ].

The inclusion criteria were articles: (a) written in English, (b) published in peer-reviewed scientific journals or (c) conference papers, (d) that reported studies with quantitative measurements and correlation indexes of leadership style and AP, (e) featuring measurement instruments specifically designed to assess the variables of interest, and (f) that contained studies conducted in public or private organizations.

The exclusion criteria were: (a) studies not published in scientific journals, such as thesis reports or books; (b) theoretical qualitative or review articles; (c) articles reporting studies conducted in scholar contexts, measuring scholars’ adaptive performance; (d) studies assessing qualitatively AP and leadership style (e) or that quantitatively evaluated either one of it alone; (f) studies that did not measure the relationship between the two constructs and, finally, (g) the duplicate of articles found in different databases.

Study selection

The study selection was conducted by one author (AB) screening the title, abstract and keywords. A total of 358 articles were found through this literature research. The application of the eligibility criteria previously described reduced the number of articles to 76. Then, the first and the second author (CP), checked and reviewed the studies included on this first step. They agreed that 34 papers were deemed suitable for the review and 31 for the meta-analysis. The third author (MGM) supervised the process. Only two articles elicited indecision with respect to include or exclude it form the review. So, we calculated the Kappa score to estimate the level of agreement intra judges and it indicated an almost substantial agreement between the two authors (k = 0.725–95,24% of agreement). Fig 1 PRISMA flow chart representing the described screening process.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304720.g001

Data collection and coding

Two reviews revised any paper retrieved independently to check for agreement and increase the validity of the study coding. Then, they used Microsoft Excel 2019 program (For Mac version) to organize data extraction categorizing and together they decided to divided and classified each article selected for the review according to the leadership style investigated (see Table 2 ). Any discrepancies in reviewers’ classification were resolved by discussion.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304720.t002

Due to the heterogeneity of the studies found in the articles that had been selected, we chose to combine a qualitative narrative approach and a quantitative meta-analysis to explain the leadership and AP relationship.

Principal descriptive information of the studies included in review are reported in the follow paragraph titled: “Results: Article Description” and synthetized in Table 3 where Pearson’s r correlation coefficients were reported and used to determine the effect size for the meta-analysis (see Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304720.t003

Results: Articles description

All articles contained studies that investigated the relationship between leadership and adaptive AP; some of them read AP at the individual level (n. 24), while others measured it at the team level (n. 6) or at both levels (n. 3). Han and Williams, who studied the differences between individual performance and team adaptive performance, found that the two constructs were closely related, concluding that a high level of individual adaptivity extended to the team through members’ coordination and cooperation capacity.

Except for the studies of Kaltiainen and Hakanen [ 90 ] and Curado and Santos [ 78 ], which detected AP as a multidimensional construct, all studies explored AP as a mono-dimensional construct and the scales mostly used to assess job adaptivity were: Griffin, Neal and Parker’s scale [ 19 ] and Charbonnier-Voirin and Roussel’s scale [ 20 ].

As for the sample, the majority of the articles reported surveys that had been carried out on workers; only two surveys had collected data from students [ 80 , 86 ]. All of the studies were carried out in one or more organizations, with the exception of the one by Sanchez-Manzanares and colleagues [ 86 ], who conducted their research in an artificial context of simulation. In most of the cases, nr. 13, data were collected from private companies, 8 studies are conducted in public sector and 2 studies in enterprises of both sectors, private and public. With respect to the type of organizations involved, it ranges from textile and manufactory industry, bank financial and accounting firms, ICT/electronic firms, health care and human service sector organizations and hospitality industries. One article used an online crowdsourcing platform (MTurk) to collect data and 10 articles did not present sufficient elements for us to understand what type of organizations the data were collected from.

Finally, all the selected articles were recent, with the year of publication ranging from 2010 to 2024, and most of the studies was conducted in Europe (n. 12), followed by Asia (n. 17), North America (n. 4) and Africa (n.1).

Leadership and adaptive performance: The relationship

Many of the studies included not only additional designs aimed to analyze the primary relationship of interest, but also the covariate and moderators’ effects. Of the 34 articles included in our systematic review, the majority (n. 33) probed the relationship between a specific leadership style and employee AP and one focused on leader’s personality and leader’s adaptivity.