Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Free to the people.

The First Amendment, Censorship, and Private Companies: What Does “Free Speech” Really Mean?

By Julie Horowitz

Updated August 2023:

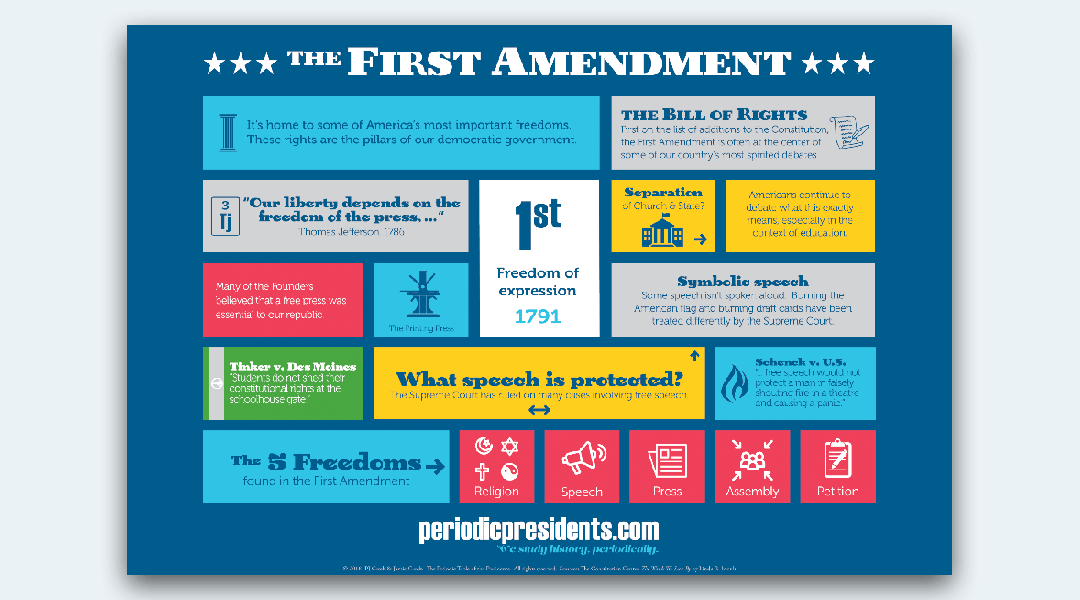

The First Amendment Defined

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects what are commonly known as The Five Freedoms: freedom of religion, freedom of press, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of petition. The amendment is part of ten amendments to the Constitution known as the Bill of Rights, which was adopted in 1791. The First Amendment Reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” (Source: National Archives )

This amendment gives Americans the right to express themselves verbally and through publication without government interference. It also prevents the government from establishing a “state” religion, and from favoring one religion over others. And finally, it protects Americans’ rights to gather in groups for social, economic, political, or religious purposes; sign petitions; and even file a lawsuit against the government. (Source: History.com )

Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Speech

Freedom of the press and freedom of speech are closely related, and are often the subject of court cases and popular news. Understanding how and when these rights are protected by the First Amendment can help us better understand current events and court decisions.

While the First Amendment acknowledges and protects these rights, there are limitations to how the amendment can be invoked. For instance: people are free to express themselves through publication; however, false or defamatory statements (called libel) are not protected under the First Amendment.

What is Defamation? Defamation occurs if you make a false statement of fact about someone else that harms that person’s reputation. Such speech is not protected by the First Amendment and could result in criminal and civil liability. Defamation is limited in multiple respects though.

If you make a false statement of fact about a public official or a public figure, more First Amendment protection applies to ensure that people are not afraid to talk about public issues. According to New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) , defamation against public officials or public figures also requires that the party making the statement used “actual malice,” meaning the false statement was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

Parodies and satire are protected by the First Amendment (and are not defamatory). Parodies and satire are meant to humorously poke fun at someone or something, not report believable facts.

(Source: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee )

The First Amendment also specifically refers to the interference of government in these rights. This ensures that Americans are free to critique the government, but it does not give Americans blanket immunity to say whatever they want, wherever they want, without consequences. Lata Nott, Executive Director of the First Amendment Center, explains:

The First Amendment only protects your speech from government censorship. It applies to federal, state, and local government actors. This is a broad category that includes not only lawmakers and elected officials, but also public schools and universities, courts, and police officers. It does not include private citizens, businesses, and organizations. This means that:

- A private school can suspend students for criticizing a school policy;

- A private business can fire an employee for expressing political views on the job; and

- A private media company can refuse to publish or broadcast opinions it disagrees with.

(Source: Freedom Forum Institute )

Supreme Court Cases

The U.S. Supreme Court has often been called upon to determine what types of speech are protected under the First Amendment. Since the adoption of the Bill of Rights, hundreds of cases have been seen by the Supreme Court, setting precedence for future cases and refining the definition of speech protected by the First Amendment.

Cox v. New Hampshire Protests and freedom to assemble

Elonis v. U.S. Facebook and free speech

Engel v. Vitale Prayer in schools and freedom of religion

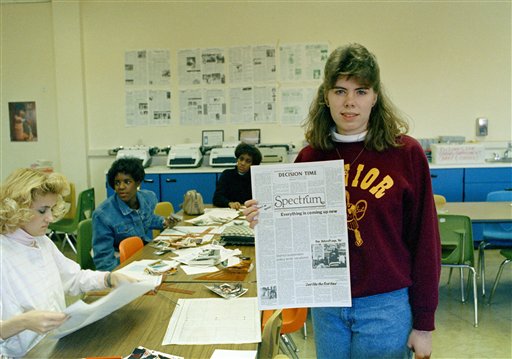

Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier Student newspapers and free speech

Morse v. Frederick School-sponsored events and free speech

Snyder v. Phelps Public concerns, private matters, and free speech

Texas v. Johnson Flag burning and free speech

Tinker v. Des Moines Free speech in schools

U.S. v. Alvarez Lies and free speech

(Source: UScourts.gov )

So what types of speech are protected by the First Amendment? Let’s turn to some experts to better understand:

- Is Your Speech Protected by the First Amendment? by Lata Nott, Executive Director, First Amendment Center (Source: Freedom Forum Institute )

- What does Free Speech Mean? (Source: United States Courts )

- Freedom of Speech and the Press by Geoffrey R. Stone and Eugene Volokh (Source: Interactive Constitution via the National Constitution Center )

Censorship Defined

Censorship is the suppression or prohibition of words, images, or ideas that are considered offensive, obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security (Sources: Lexico and ACLU ). The First Amendment Encyclopedia notes that “censors seek to limit freedom of thought and expression by restricting spoken words, printed matter, symbolic messages, freedom of association, books, art, music, movies, television programs, and internet sites” (Source: The First Amendment Encyclopedia ).

Censorship by the government is unconstitutional. When the government engages in censorship, it goes against the First Amendment rights discussed above. However, there are still examples of government censorship in our history (see the 1873 Comstock Law and the 1996 Communications Decency Act ), and the Supreme Court is often called upon to ensure that First Amendment rights are being protected.

Private individuals and groups still often engage in censorship. As long as government entities are not involved, this type of censorship technically presents no First Amendment implications. Many of us are familiar with the censoring of popular music, movies, and art to exclude words or images that are considered “vulgar” or “obscene.” While many of these forms of censorship are technically legal, private groups like the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) work to make sure that the right to free speech is honored.

To learn more about the history of censorship in the United States, and across the world, consider the sources below.

- Censorship in the United States by Tom Head, Civil Liberties Expert (Source: ThoughtCo. )

- Censorship by George Anastaplo (Source: Britannica )

- A Brief History of Film Censorship (Source: NCAC.org )

- Music Censorship in America (Source: NCAC.org )

- Book Banning by Susan L. Webb (Source: The First Amendment Encyclopedia )

Free Speech Online and on Social Media (Section 230)

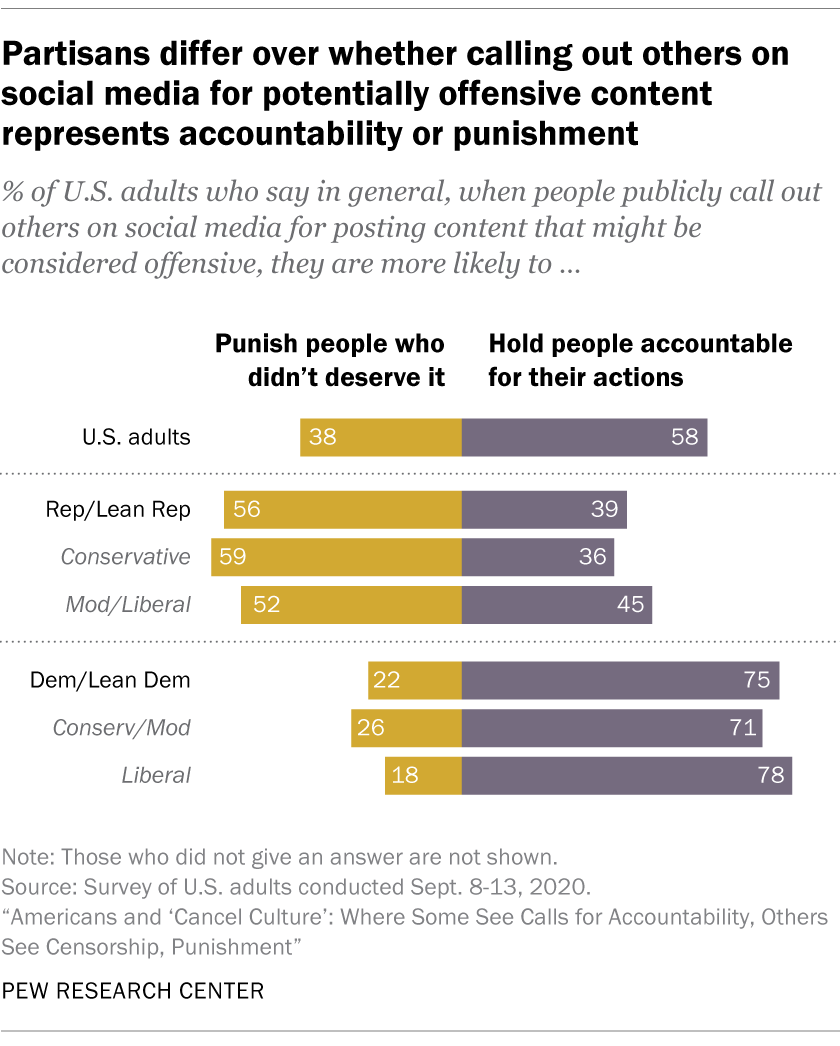

The widespread use of the internet, and particularly social media platforms, has presented new challenges in defining what types speech are protected by the First Amendment. Social Media platforms are private companies, and we learned above that private companies are legally able to establish regulations and guidelines within their communities–including censorship of content or banning of members.

Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act , states that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” That legal phrase shields companies that can host trillions of messages from being sued into oblivion by anyone who feels wronged by something someone else has posted — whether their complaint is legitimate or not.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have argued, for different reasons, that Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms have abused that protection and should lose their immunity — or at least have to earn it by satisfying requirements set by the government.

Section 230 also allows social platforms to moderate their services by removing posts that, for instance, are obscene or violate the services’ own standards, so long as they are acting in “good faith.” (Source: The Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University )

But what happens when politicians use these platforms to communicate with the people they lead? Is it legal for a social media platform to ban a person from using their service? If a politician bans or blocks members from interacting with their content on a social media platform, is it considered a First Amendment violation?

Below are some additional sources discussing how the First Amendment applies to online interactions and social media:

- Video Playlist: CivicCLP – First Amendment

- Podcast: What Does Free Speech Mean Online? Kate Ruane, senior legislative counsel for First Amendment issues at the ACLU (Source: At Liberty via ACLU.org )

- Everything You Need to Know About Section 230 by Casey Newton (Source: The Verge )

- Social Media and Government Use of Social Media by David L. Hudson Jr. (Source: The First Amendment Encyclopedia )

- Censorship, Free Speech & Facebook: Applying the First Amendment to Social Media Platforms via the Public Function Exception (Source: Washington Journal of Law, Technology and Arts )

- Brown v. Board of Ed (1954) - a landmark case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional.

- Loving v. Virginia (1967) – a landmark case in which justices ruled unanimously to strike down state laws banning interracial marriage in the United States.

- Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls (2002) – Justices ruled (5–4) that suspicionless drug testing of students participating in competitive extracurricular activities did not violate the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees protection from unreasonable searches and seizures.

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) – Justices ruled (5–4) that laws that prevented corporations and unions from using their general treasury funds for independent “electioneering communications” (political advertising) violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech.

- Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) – Justices ruled (5-4) that state bans on same-sex marriage and on recognizing same-sex marriages duly performed in other jurisdictions are unconstitutional under the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

- Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru (2020) – Justices ruled (7-2) that federal employment discrimination laws do not apply to teachers at church-run schools.

- Supreme Court Justices – Interactive Timeline

- Rule of Law (Protection of Minorities)

Sign Up for the CivicCLP Newsletter:

What is civic engagement, source: presidential precinct, first amendment resources:.

- First Amendment Center - Freedom Forum Institute

- What Does Free Speech Mean? (U.S. Courts)

- Bill of Rights Institute

- The First Amendment for the Twenty-First Century (The Pittsburgh Foundation)

Voter Registration Resources and Voting Information:

- Pennsylvania Voter Registration Form

- Election Division of Allegheny County

- WESA Voting Guide

- Incarcerated Citizens: Know Your Rights from LWVPGH

- Returning Citizens and Citizens with a Criminal Record from LWVPGH

Civic Education & Engagement Local Partners:

- League of Women Voters of Greater Pittsburgh

- Allegheny County Law Library

- Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts

- JCC's Center for Loving Kindness and Civic Engagement

- VEEEM Pittsburgh

Citizenship and Volunteering Initiatives:

- CLP Welcome Centers

- Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition

- VolunteerMatch (Pittsburgh Organizations)

National Resources

local resources .

Support the Library, Give Today

What would you like to find.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

15.4 Censorship and Freedom of Speech

Learning objectives.

- Explain the FCC’s process of classifying material as indecent, obscene, or profane.

- Describe how the Hay’s Code affected 20th-century American mass media.

Figure 15.3

Attempts to censor material, such as banning books, typically attract a great deal of controversy and debate.

Timberland Regional Library – Banned Books Display At The Lacey Library – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

To fully understand the issues of censorship and freedom of speech and how they apply to modern media, we must first explore the terms themselves. Censorship is defined as suppressing or removing anything deemed objectionable. A common, everyday example can be found on the radio or television, where potentially offensive words are “bleeped” out. More controversial is censorship at a political or religious level. If you’ve ever been banned from reading a book in school, or watched a “clean” version of a movie on an airplane, you’ve experienced censorship.

Much as media legislation can be controversial due to First Amendment protections, censorship in the media is often hotly debated. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press (Case Summaries).” Under this definition, the term “speech” extends to a broader sense of “expression,” meaning verbal, nonverbal, visual, or symbolic expression. Historically, many individuals have cited the First Amendment when protesting FCC decisions to censor certain media products or programs. However, what many people do not realize is that U.S. law establishes several exceptions to free speech, including defamation, hate speech, breach of the peace, incitement to crime, sedition, and obscenity.

Classifying Material as Indecent, Obscene, or Profane

To comply with U.S. law, the FCC prohibits broadcasters from airing obscene programming. The FCC decides whether or not material is obscene by using a three-prong test.

Obscene material:

- causes the average person to have lustful or sexual thoughts;

- depicts lawfully offensive sexual conduct; and

- lacks literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

Material meeting all of these criteria is officially considered obscene and usually applies to hard-core pornography (Federal Communications Commission). “Indecent” material, on the other hand, is protected by the First Amendment and cannot be banned entirely.

Indecent material:

- contains graphic sexual or excretory depictions;

- dwells at length on depictions of sexual or excretory organs; and

- is used simply to shock or arouse an audience.

Material deemed indecent cannot be broadcast between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m., to make it less likely that children will be exposed to it (Federal Communications Commission).

These classifications symbolize the media’s long struggle with what is considered appropriate and inappropriate material. Despite the existence of the guidelines, however, the process of categorizing materials is a long and arduous one.

There is a formalized process for deciding what material falls into which category. First, the FCC relies on television audiences to alert the agency of potentially controversial material that may require classification. The commission asks the public to file a complaint via letter, e-mail, fax, telephone, or the agency’s website, including the station, the community, and the date and time of the broadcast. The complaint should “contain enough detail about the material broadcast that the FCC can understand the exact words and language used (Federal Communications Commission).” Citizens are also allowed to submit tapes or transcripts of the aired material. Upon receiving a complaint, the FCC logs it in a database, which a staff member then accesses to perform an initial review. If necessary, the agency may contact either the station licensee or the individual who filed the complaint for further information.

Once the FCC has conducted a thorough investigation, it determines a final classification for the material. In the case of profane or indecent material, the agency may take further actions, including possibly fining the network or station (Federal Communications Commission). If the material is classified as obscene, the FCC will instead refer the matter to the U.S. Department of Justice, which has the authority to criminally prosecute the media outlet. If convicted in court, violators can be subject to criminal fines and/or imprisonment (Federal Communications Commission).

Each year, the FCC receives thousands of complaints regarding obscene, indecent, or profane programming. While the agency ultimately defines most programs cited in the complaints as appropriate, many complaints require in-depth investigation and may result in fines called notices of apparent liability (NAL) or federal investigation.

Table 15.1 FCC Indecency Complaints and NALs: 2000–2005

| Year | Total Complaints Received | Radio Programs Complained About | Over-the-Air Television Programs Complained About | Cable Programs Complained About | Total Radio NALs | Total Television NALs | Total Cable NALs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 111 | 85 | 25 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2001 | 346 | 113 | 33 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| 2002 | 13,922 | 185 | 166 | 38 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2003 | 166,683 | 122 | 217 | 36 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2004 | 1,405,419 | 145 | 140 | 29 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| 2005 | 233,531 | 488 | 707 | 355 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

Violence and Sex: Taboos in Entertainment

Although popular memory thinks of old black-and-white movies as tame or sanitized, many early filmmakers filled their movies with sexual or violent content. Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 silent film The Great Train Robbery , for example, is known for expressing “the appealing, deeply embedded nature of violence in the frontier experience and the American civilizing process,” and showcases “the rather spontaneous way that the attendant violence appears in the earliest developments of cinema (Film Reference).” The film ends with an image of a gunman firing a revolver directly at the camera, demonstrating that cinema’s fascination with violence was present even 100 years ago.

Porter was not the only U.S. filmmaker working during the early years of cinema to employ graphic violence. Films such as Intolerance (1916) and The Birth of a Nation (1915) are notorious for their overt portrayals of violent activities. The director of both films, D. W. Griffith, intentionally portrayed content graphically because he “believed that the portrayal of violence must be uncompromised to show its consequences for humanity (Film Reference).”

Although audiences responded eagerly to the new medium of film, some naysayers believed that Hollywood films and their associated hedonistic culture was a negative moral influence. As you read in Chapter 8 “Movies” , this changed during the 1930s with the implementation of the Hays Code. Formally termed the Motion Picture Production Code of 1930, the code is popularly known by the name of its author, Will Hays, the chairman of the industry’s self-regulatory Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association (MPPDA), which was founded in 1922 to “police all in-house productions (Film Reference).” Created to forestall what was perceived to be looming governmental control over the industry, the Hays Code was, essentially, Hollywood self-censorship. The code displayed the motion picture industry’s commitment to the public, stating:

Motion picture producers recognize the high trust and confidence which have been placed in them by the people of the world and which have made motion pictures a universal form of entertainment…. Hence, though regarding motion pictures primarily as entertainment without any explicit purposes of teaching or propaganda, they know that the motion picture within its own field of entertainment may be directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking (Arts Reformation).

Among other requirements, the Hays Code enacted strict guidelines on the portrayal of violence. Crimes such as murder, theft, robbery, safecracking, and “dynamiting of trains, mines, buildings, etc.” could not be presented in detail (Arts Reformation). The code also addressed the portrayals of sex, saying that “the sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing (Arts Reformation).”

Figure 15.4

As the chairman of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, Will Hays oversaw the creation of the industry’s self-censoring Hays Code.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

As television grew in popularity during the mid-1900s, the strict code placed on the film industry spread to other forms of visual media. Many early sitcoms, for example, showed married couples sleeping in separate twin beds to avoid suggesting sexual relations.

By the end of the 1940s, the MPPDA had begun to relax the rigid regulations of the Hays Code. Propelled by the changing moral standards of the 1950s and 1960s, this led to a gradual reintroduction of violence and sex into mass media.

Ratings Systems

As filmmakers began pushing the boundaries of acceptable visual content, the Hollywood studio industry scrambled to create a system to ensure appropriate audiences for films. In 1968, the successor of the MPPDA, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), established the familiar film ratings system to help alert potential audiences to the type of content they could expect from a production.

Film Ratings

Although the ratings system changed slightly in its early years, by 1972 it seemed that the MPAA had settled on its ratings. These ratings consisted of G (general audiences), PG (parental guidance suggested), R (restricted to ages 17 or up unless accompanied by a parent), and X (completely restricted to ages 17 and up). The system worked until 1984, when several major battles took place over controversial material. During that year, the highly popular films Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Gremlins both premiered with a PG rating. Both films—and subsequently the MPAA—received criticism for the explicit violence presented on screen, which many viewers considered too intense for the relatively mild PG rating. In response to the complaints, the MPAA introduced the PG-13 rating to indicate that some material may be inappropriate for children under the age of 13.

Another change came to the ratings system in 1990, with the introduction of the NC-17 rating. Carrying the same restrictions as the existing X rating, the new designation came at the behest of the film industry to distinguish mature films from pornographic ones. Despite the arguably milder format of the rating’s name, many filmmakers find it too strict in practice; receiving an NC-17 rating often leads to a lack of promotion or distribution because numerous movie theaters and rental outlets refuse to carry films with this rating.

Television and Video Game Ratings

Regardless of these criticisms, most audience members find the rating system helpful, particularly when determining what is appropriate for children. The adoption of industry ratings for television programs and video games reflects the success of the film ratings system. During the 1990s, for example, the broadcasting industry introduced a voluntary rating system not unlike that used for films to accompany all TV shows. These ratings are displayed on screen during the first 15 seconds of a program and include TV-Y (all children), TV-Y7 (children ages 7 and up), TV-Y7-FV (older children—fantasy violence), TV-G (general audience), TV-PG (parental guidance suggested), TV-14 (parents strongly cautioned), and TV-MA (mature audiences only).

Table 15.2 Television Ratings System

| Rating | Meaning | Examples of Programs |

|---|---|---|

| TV-Y | Appropriate for all children | , , |

| TV-Y7 | Designed for children ages 7 and up | , |

| TV-Y7-FV | Directed toward older children; includes depictions of fantasy violence | , , |

| TV-G | Suitable for general audiences; contains little or no violence, no strong language, and little or no sexual material | , , |

| TV-PG | Parental guidance suggested | , , |

| TV-14 | Parents strongly cautioned; contains suggestive dialogue, strong language, and sexual or violent situations | , , |

| TV-MA | Mature audiences only | , , |

Source: http://www.tvguidelines.org/ratings.htm

At about the same time that television ratings appeared, the Entertainment Software Rating Board was established to provide ratings on video games. Video game ratings include EC (early childhood), E (everyone), E 10+ (ages 10 and older), T (teen), M (mature), and AO (adults only).

Table 15.3 Video Game Ratings System

| Rating | Meaning | Examples of Games |

|---|---|---|

| EC | Designed for early childhood, children ages 3 and older | , , |

| E | Suitable for everyone over the age of 6; contains minimal fantasy violence and mild language | , , , |

| E 10+ | Appropriate for ages 10 and older; may contain more violence and/or slightly suggestive themes | , , , |

| T | Content is appropriate for teens (ages 13 and older); may contain violence, crude humor, sexually suggestive themes, use of strong language, and/or simulated gambling | , , |

| M | Mature content for ages 17 and older; includes intense violence and/or sexual content | , , , |

| AO | Adults (18+) only; contains graphic sexual content and/or prolonged violence | , |

Source: http://www.esrb.org/ratings/ratings_guide.jsp

Even with these ratings, the video game industry has long endured criticism over violence and sex in video games. One of the top-selling video game series in the world, Grand Theft Auto , is highly controversial because players have the option to solicit prostitution or murder civilians (Media Awareness). In 2010, a report claimed that “38 percent of the female characters in video games are scantily clad, 23 percent baring breasts or cleavage, 31 percent exposing thighs, another 31 percent exposing stomachs or midriffs, and 15 percent baring their behinds (Media Awareness).” Despite multiple lawsuits, some video game creators stand by their decisions to place graphic displays of violence and sex in their games on the grounds of freedom of speech.

Key Takeaways

- The U.S. Government devised the three-prong test to determine if material can be considered “obscene.” The FCC applies these guidelines to determine whether broadcast content can be classified as profane, indecent, or obscene.

- Established during the 1930s, the Hays Code placed strict regulations on film, requiring that filmmakers avoid portraying violence and sex in films.

- After the decline of the Hays Code during the 1960s, the MPAA introduced a self-policed film ratings system. This system later inspired similar ratings for television and video game content.

Look over the MPAA’s explanation of each film rating online at http://www.mpaa.org/ratings/what-each-rating-means . View a film with these requirements in mind and think about how the rating was selected. Then answer the following short-answer questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Would this material be considered “obscene” under the Hays Code criteria? Would it be considered obscene under the FCC’s three-prong test? Explain why or why not. How would the film be different if it were released in accordance to the guidelines of the Hays Code?

- Do you agree with the rating your chosen film was given? Why or why not?

Arts Reformation, “The Motion Picture Production Code of 1930 (Hays Code),” ArtsReformation, http://www.artsreformation.com/a001/hays-code.html .

Case Summaries, “First Amendment—Religion and Expression,” http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data/constitution/amendment01/ .

Federal Communications Commission, “Obscenity, Indecency & Profanity: Frequently Asked Questions,” http://www.fcc.gov/eb/oip/FAQ.html .

Film Reference, “Violence,” Film Reference, http://www.filmreference.com/encyclopedia/Romantic-Comedy-Yugoslavia/Violence-BEGINNINGS.html .

Media Awareness, Media Issues, “Sex and Relationships in the Media,” http://www.media-awareness.ca/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_sex.cfm .

Media Awareness, Media Issues, “Violence in Media Entertainment,” http://www.media-awareness.ca/english/issues/violence/violence_entertainment.cfm .

Understanding Media and Culture Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

First Amendment and Censorship

First Amendment Resources | Statements & Core Documents | Publications & Guidelines

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791.

One of the ten amendments of the Bill of Rights, the First Amendment gives everyone residing in the United States the right to hear all sides of every issue and to make their own judgments about those issues without government interference or limitations. The First Amendment allows individuals to speak, publish, read and view what they wish, worship (or not worship) as they wish, associate with whomever they choose, and gather together to ask the government to make changes in the law or to correct the wrongs in society.

The right to speak and the right to publish under the First Amendment has been interpreted widely to protect individuals and society from government attempts to suppress ideas and information, and to forbid government censorship of books, magazines, and newspapers as well as art, film, music and materials on the internet. The Supreme Court and other courts have held conclusively that there is a First Amendment right to receive information as a corollary to the right to speak. Justice William Brennan elaborated on this point in 1965:

“The protection of the Bill of Rights goes beyond the specific guarantees to protect from Congressional abridgment those equally fundamental personal rights necessary to make the express guarantees fully meaningful.I think the right to receive publications is such a fundamental right.The dissemination of ideas can accomplish nothing if otherwise willing addressees are not free to receive and consider them. It would be a barren marketplace of ideas that had only sellers and no buyers.” Lamont v. Postmaster General , 381 U.S. 301 (1965).

The Supreme Court reaffirmed that the right to receive information is a fundamental right protected under the U.S. Constitution when it considered whether a local school board violated the Constitution by removing books from a school library. In that decision, the Supreme Court held that “the right to receive ideas is a necessary predicate to the recipient’s meaningful exercise of his own rights of speech, press, and political freedom.” Board of Education v. Pico , 457 U.S. 853 (1982)

Public schools and public libraries, as public institutions, have been the setting for legal battles about student access to books, the removal or retention of “offensive” material, regulation of patron behavior, and limitations on public access to the internet. Restrictions and censorship of materials in public institutions are most commonly prompted by public complaints about those materials and implemented by government officials mindful of the importance some of their constituents may place on religious values, moral sensibilities, and the desire to protect children from materials they deem to be offensive or inappropriate. Directly or indirectly, ordinary individuals are the driving force behind the challenges to the freedom to access information and ideas in the library.

The First Amendment prevents public institutions from compromising individuals' First Amendment freedoms by establishing a framework that defines critical rights and responsibilities regarding free expression and the freedom of belief. The First Amendment protects the right to exercise those freedoms, and it advocates respect for the right of others to do the same. Rather than engaging in censorship and repression to advance one's values and beliefs, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis counsels persons living in the United States to resolve their differences in values and belief by resort to "more speech, not enforced silence."

By virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment, the First Amendment's constitutional right of free speech and intellectual freedom also applies to state and local governments. Government agencies and government officials are forbidden from regulating or restricting speech or other expression based on its content or viewpoint. Criticism of the government, political dissatisfaction, and advocacy of unpopular ideas that people may find distasteful or against public policy are nearly always protected by the First Amendment. Only that expression that is shown to belong to a few narrow categories of speech is not protected by the First Amendment. The categories of unprotected speech include obscenity, child pornography, defamatory speech, false advertising, true threats, and fighting words. Deciding what is and is not protected speech is reserved to courts of law.

The First Amendment only prevents government restrictions on speech. It does not prevent restrictions on speech imposed by private individuals or businesses. Facebook and other social media can regulate or restrict speech hosted on their platforms because they are private entities.

First Amendment Resources

Clauses of the First Amendment | The National Constitution Center

First Amendment FAQ | Freedom Forum

Freedom of Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, and Petition: Common Interpretations and Matters for Debate | National Constitution Center

First Amendment - Religion and Expression | FindLaw

What is Censorship?

Censorship is the suppression of ideas and information that some individuals, groups, or government officials find objectionable or dangerous. Would-be censors try to use the power of the state to impose their view of what is truthful and appropriate, or offensive and objectionable, on everyone else. Censors pressure public institutions, like libraries, to suppress and remove information they judge inappropriate or dangerous from public access, so that no one else has the chance to read or view the material and make up their own minds about it. The censor wants to prejudge materials for everyone. It is no more complicated than someone saying, “Don’t let anyone read this book, or buy that magazine, or view that film, because I object to it!”

“Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment.” — Article 3, Library Bill of Rights

ALA Statements and Policies on Censorship

Challenged Resources: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights (2019) A challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group. A banning is the removal of those materials. Challenges do not simply involve a person expressing a point of view; rather, they are an attempt to remove material from the curriculum or library, thereby restricting the access of others. ALA declares as a matter of firm principle that it is the responsibility of every library to have a clearly defined written policy for collection development that includes a procedure for review of challenged resources.

Labeling Systems: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights (2015) The American Library Association affirms the rights of individuals to form their own opinions about resources they choose to read, view, listen to, or otherwise access. Libraries do not advocate the ideas found in their collections or in resources accessible through the library. The presence of books and other resources in a library does not indicate endorsement of their contents by the library. Likewise, providing access to digital information does not indicate endorsement or approval of that information by the library. Labeling systems present distinct challenges to these intellectual freedom principles.

Rating Systems: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights (2019) Libraries, no matter their size, contain an enormous wealth of viewpoints and are responsible for making those viewpoints available to all. However, libraries do not advocate or endorse the content found in their collections or in resources made accessible through the library. Rating systems appearing in library public access catalogs or resource discovery tools present distinct challenges to these intellectual freedom principles. Q&A on Labeling and Rating Systems

Expurgation of Library Materials: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights (2014) Expurgating library materials is a violation of the Library Bill of Rights. Expurgation as defined by this interpretation includes any deletion, excision, alteration, editing, or obliteration of any part(s) of books or other library resources by the library, its agent, or its parent institution (if any).

Restricted Access to Library Materials: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights (2014) Libraries are a traditional forum for the open exchange of information. Attempts to restrict access to library materials violate the basic tenets of the Library Bill of Rights.

Complete list of Library Bill of Rights Interpretations

Core Documents

Library Bill of Rights (1939) Adopted by ALA Council, the Articles of the Library Bill of Rights are unambiguous statements of basic principles that should govern the service of all libraries. ( printable pamphlets )

Freedom to Read Statement (1953) A collaborative statement by literary, publishing, and censorship organizations declaring the importance of our constitutionally protected right to access information and affirming the need for our professions to oppose censorship.

Libraries: An American Value (1999) Adopted by ALA Council, this brief statement pronounces the distinguished place libraries hold in our society and their core tenets of access to materials and diversity of ideas.

Guidelines for Library Policies (2019) Guidelines for librarians, governing authorities, and other library staff and library users on how constitutional principles apply to libraries in the United States.

Intellectual Freedom and Censorship Q&A (2007)

Social Media Guidelines for Public and Academic Libraries (2018)

These guidelines provide a policy and implementation framework for public and academic libraries engaging in the use of social media.

Publications

Intellectual Freedom Manual (2021) Edited by Martin Garnar and Trina Magi with ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom The 10th edition manual is an indispensable resource for day-to-day guidance on maintaining free and equal access to information for all people

Journal of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy (2016 - present) Edited by Shannon Oltmann with ALA's Office for Intellectual Freedom Published quarterly, JIFP offers articles related to intellectual freedom and privacy, both in libraries and in the wider world.

True Stories of Censorship Battles in America's Libraries (2012) By Valerie Nye and Kathy Barco This book is a collection of accounts from librarians who have dealt with censorship in some form. Divided into seven parts, the book covers intralibrary censorship, child-oriented protectionism, the importance of building strong policies, experiences working with sensitive materials, public debates and controversies, criminal patrons, and library displays.

Beyond Banned Books: Defending Intellectual Freedom throughout Your Library (2019) By Kristin Pekoll with ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom A level-headed guide that uses specific case studies to offer practical guidance on safeguarding intellectual freedom related to library displays, programming, and other librarian-created content.

Lessons in Censorship: How Schools and Courts Subvert Students' First Amendment Rights (2015) By Catherine J. Ross Lessons in Censorship highlights the troubling and growing tendency of schools to clamp down on off-campus speech such as texting and sexting and reveals how well-intentioned measures to counter verbal bullying and hate speech may impinge on free speech. Throughout, Ross proposes ways to protect free expression without disrupting education.

Assistance and Consultation

The staff of the Office for Intellectual Freedom is available to answer questions or provide assistance to librarians, trustees, educators, and the public about the First Amendment and censorship. Areas of assistance include policy development, minors’ rights, and professional ethics. Inquiries can be directed via email to [email protected] or via phone at (312) 280-4226.

Updated October 2021

Share This Page

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The status of "individuality”

Requirements of self-government.

- “Freedom of expression”

- Ancient Greece and Rome

- Ancient Israel and early Christianity

- Ancient China

- Medieval Christendom

- The 17th and 18th centuries

- The system in the former Soviet Union

- Censorship under a military government

- Freedom of the press

- Freedom and truth

- Character and freedom

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- University of Washington Pressbooks - Media and Society: Critical Approaches - Censorship and Freedom of Speech

- Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University - Censorship

- The Canadian Encyclopedia - Censorship

- Oklahoma State University - School of Media and Strategic Communications - Defining Censorship

- Humanities LibreTexts - Censorship

- Frontiers - Racism and censorship in the editorial and peer review process

- Cato Institute - Shining a Light on Censorship: How Transparency Can Curtail Government Social Media Censorship and More

- American Library Association - First Amendment and Censorship

- censorship - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- censorship - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

censorship , the changing or the suppression or prohibition of speech or writing that is deemed subversive of the common good . It occurs in all manifestations of authority to some degree, but in modern times it has been of special importance in its relation to government and the rule of law .

Concerns relevant to censorship

Censorship, as a term in English, goes back to the office of censor established in Rome in 443 bce . That officer, who conducted the census, regulated the morals of the citizens counted and classified. But, however honourable the origins of its name, censorship itself is today generally regarded as a relic of an unenlightened and much more oppressive age.

Illustrative of this change in opinion is how a community responds to such a sentiment as that with which Protagoras (c. 490–c. 420 bce ) opened his work Concerning the Gods :

About the gods I am not able to know either that they are, or that they are not, or what they are like in shape, the things preventing knowledge being many, such as the obscurity of the subject and that the life of man is short.

This public admission of agnosticism scandalized Protagoras’s fellow Greeks. Such statements would no doubt have been received with hostility, and probably with social if not even criminal sanctions, throughout the ancient world. In most places in the modern world, on the other hand, such a statement could be made without the prospect of having to endure a pained and painful community response. This change reflects, among other things, a profound shift in opinion as to what is and is not a legitimate concern of government.

Whereas it could once be maintained that the law forbids whatever it does not permit, it is now generally accepted—at least wherever Western liberalism is in the ascendancy—that one may do whatever is not forbidden by law. Furthermore, it is now believed that what may be properly forbidden by law is quite limited. Much is made of permitting people to do with their lives (including their opinions) as they please, so long as they do no immediate and evident (usually physical) harm to others. Thus, Leo Strauss has observed, “The quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns concerns eventually, and perhaps even from the beginning, the status of ‘individuality.’ ”

All this is to say that individualism is made much of in modernity. The status, then, of censorship very much depends on the standing of government itself and of legitimate authority, revealing still another aspect of the complicated relation between “the individual and the state.”

One critical source of the contemporary repudiation of censorship in the West depends on something that may be distinctive to modernity, an emphasis upon the dignity of the individual. This respect for individuality has its roots both in Christian doctrines and in the (not unrelated) sovereignty of the self reflected in state-of-nature theories about the foundations of social organization. Vital to this approach is the general opinion about the nature and sanctity of the human soul . This general opinion provides the foundation of a predominantly new, or modern, argument against censorship—against anything, in fact, that interferes with self-development, and especially such self-development (or, better still, “self-fulfillment”) as a person happens to want and to choose for himself. This can be put in terms of liberty—the liberty to become and to do what one pleases.

The old, or traditional, argument against censorship was much less individualistic and much more political in its orientation, making more of another sense of liberty. According to that sense, if a people is to be self-governing, it must have access to all information and arguments that may be relevant to its ability to discuss public affairs fully and to assess in a competent manner the conduct of the officials it chooses. Thus, “ freedom of speech ,” which is constitutionally guaranteed to the people of the United States , first comes to view in Anglo-American legal history as a guarantee for the members of the British Parliament assembled to discuss the affairs of the kingdom.

In the circumstances of a people actually governing itself, it is obvious that there is no substitute for freedom of speech and of the press , particularly as that freedom permits an informed access to information and opinions about political matters. Even the more repressive regimes today recognize this underlying principle, in that their ruling bodies try to make certain that they themselves become and remain informed about what is “really” going on in their countries and abroad, however repressive they may be in not permitting their own people to learn about and openly to discuss public affairs. Whether anyone who thus rules unjustly, or otherwise improperly, can be regarded as truly understanding and hence truly controlling his situation is a question not limited to these circumstances.

“ Freedom of expression ”

The shift from the more political to the more individualistic view of liberty may be seen in how the constitutional guarantees with respect to speech and the press are typically spoken of in the United States. Restraints upon speaking and publishing , and indeed upon action generally, are fewer now than at most times in the history of the country. This absence of restraints is reflected as well in the very terms in which these rights and privileges are described. What would once have been referred to as “freedom of speech and of the press” (drawing upon the language of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States ) is now often referred to as “freedom of expression.”

To make much of freedom of expression is to encourage a liberation of the self from the constraints of the community. It may even be to assume that the self has, intrinsic to it or somehow available to it independent of any social guidance, intimations of what it is and what it wants. Thus, liberation may be seen in the desire of most people to be free to pursue their own goals and life plans—which may involve a reliance upon standards and objectives that are solely their own. It is tempting, in such circumstances, to adopt a radical subjectivism that tends to result in a thoroughgoing relativism with respect to moral and political judgments. One consequence of this approach is to identify an ever-expanding array of forms and media of expression that are entitled to immunity from government regulation—including not only broadcast and print media ( books and newspapers ) but also text messaging and Internet media such as blogs , social networking sites, and e-commerce sites.

On the other hand, if the emphasis is placed upon the more traditional language, “freedom of speech and of the press,” the requirements and prerogatives of a self-governing people are apt to be made more of. This means, among other things, that a people must be prepared and equipped to make effective use of its considerable political power. (Even those rulers who act without the authority of the people must take care to shape their people in accordance with the needs and circumstances of their regime. This kind of effort need not be altogether selfish on the part of such rulers, since all regimes do have an interest in law and order, in common decency, and in a routine reliability or loyalty.) It should be evident that a people entrusted with the power of self-government must be able to exercise a disciplined judgment: not everything goes, and there are better and worse things awaiting the community and its citizens.

What is particularly difficult to argue for, and to maintain, is an arrangement that, while it leaves a people clearly free politically to discuss fully all matters of public interest with a view toward governing itself, routinely prepares that same people for an effective exercise of its considerable freedom. In such circumstances, there are some who would take the case for, and the rhetoric of, liberty one step farther, insisting that no one should try to tell anyone else what kind of person he should be. There are others, however, who maintain that a person is truly free only if he knows what he is doing and chooses to do what is right. Anyone else, in their view, is a prisoner of illusions and appetites, however much he may believe that he is freely expressing himself.

There are, then, two related sets of concerns evident in any consideration of the forms and uses of censorship. One set of concerns has to do with the everyday governance of the community; the other, with the permanent shaping of the character of the people. The former is more political in its methods, and the latter is more educational.

- ENCYCLOPEDIA

- IN THE CLASSROOM

Home » Articles » Topic » Issues » Issues Related to Speech, Press, Assembly, or Petition » Censorship

Written by Elizabeth R. Purdy, published on August 8, 2023 , last updated on May 6, 2024

The First Amendment protects American people from government censorship. But the First Amendment's protections are not absolute, leading to Supreme Court cases involving the question of what is protected speech and what is not. On the issue of press freedoms, the Court has been reluctant to censor publication -- even of previously classified material. In the landmark case New York Times v. United States, the Court overturned a court order stopping the newspaper from continuing to print excerpts from the "Pentagon Papers", saying such prior restraint was unconstitutional. In this June 30, 1971 file picture, workers in the New York Times composing room in New York look at a proof sheet of a page containing the secret Pentagon report on Vietnam. (AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler, reprinted with permission from The Associated Press.)

Censorship occurs when individuals or groups try to prevent others from saying, printing, or depicting words and images.

Censors seek to limit freedom of thought and expression by restricting spoken words, printed matter, symbolic messages, freedom of association, books, art, music, movies, television programs, and Internet sites. When the government engages in censorship, First Amendment freedoms are implicated.

Private actors — for example, corporations that own radio stations — also can engage in forms of censorship, but this presents no First Amendment implications as no governmental, or state, action is involved.

Various groups have banned or attempted to ban books since the invention of the printing press. Censored or challenged works include the Bible, The American Heritage Dictionary, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, To Kill A Mockingbird, and the works of children’s authors J. K. Rowling and Judy Blume.

The First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech and press, integral elements of democracy. Since Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court has applied the First Amendment freedoms of speech and press to the states through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court ruled in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) that school officials have broad power of censorship over student newspapers. In this photo, Tammy Hawkins, editor of the Hazelwood East High School newspaper, Spectrum holds a copy of the paper, Jan. 14, 1988. (AP Photo/James A. Finley, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Not all speech is protected by the First Amendment

Freedom of speech and press are not, however, absolute. Over time, the Supreme Court has established guidelines, or tests, for defining what constitutes protected and unprotected speech. Among them are:

- the bad tendency test , established in Abrams v. United States (1919),

- the clear and present danger test from Schenck v. United States (1919),

- the preferred freedoms doctrine of Jones v. City of Opelika (1943), and

- the strict scrutiny , or compelling state interest , test set out in Korematsu v. United States (1944).

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. offered the classic example of the line between protected and unprotected speech in Schenck when he observed that shouting “Fire!” in a theater where there is none is not protected speech. Categories of unprotected speech also include:

- libel and slander ,

- “ fighting words ,”

- obscenity , and

Libel and slander when it comes to public officials

Determining when defamatory words may be censored has proved to be difficult for the Court, which has allowed greater freedom in remarks made about public figures than those concerning private individuals.

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court held that words can be libelous (written) or slanderous (spoken) in the case of public officials only if they involve actual malice or publication with knowledge of falsehood or reckless disregard for the truth. Lampooning has generally been protected by the Court.

In Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988), for example, the Court held that the magazine had not slandered Rev. Jerry Falwell by publishing an outrageous “advertisement” containing a caricature of him because it was presented as parody rather than truth.

On the issue of press freedoms, the Court has been reluctant to censor publication of even previously classified materials, as in New York Times v. United States (1971) — the Pentagon Papers case — unless the government can provide an overwhelming reason for such prior restraint.

The Court has accepted some censorship of the press when it interferes with the right to a fair trial, as exhibited in Estes v. Texas (1965) and Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966), but the Court has been reluctant to uphold gag orders , as in the case of Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart (1976).

In general, rap and hard-core rock-n-roll have faced more censorship than other types of music. In this photo, rap artists DJ Jazzy Jeff (Jeff Townes), left, and The Fresh Prince (Will Smith) are seen backstage at the American Music Awards ceremony in Los Angeles, Calif., Monday, January 31, 1989, after winning in the category Favorite Rap Artist and Favorite Rap Album. (AP Photo/Lennox McLendon, used with permission from the Associated Press)

When words incite “breach of peace”

In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), the Supreme Court defined “ fighting words ” as those that “by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Racial epithets and ethnic derisions have traditionally been unprotected under the umbrella of “fighting words.”

Since the backlash against so-called political correctness, however, liberals and conservatives have fought over what derogatory words may be censored and which are protected by the First Amendment.

Determining whether something is obscene

In its early history, the Supreme Court left it to the states to determine whether materials were obscene.

Acting on its decision in Gitlow v. New York (1925) to apply the First Amendment to limit state action, the Warren Court subsequently began dealing with these issues in the 1950s on a case-by-case basis and spent hours examining material to determine obscenity.

In Miller v. California (1973), the Burger Court finally adopted a test that elaborated on the standards established in Roth v. United States (1957) . Miller defines obscenity by outlining three conditions for jurors to consider:

- “(a) whether the ‘average person, applying contemporary community standards,’ would find that the work taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest;

- (b) whether the work depicts or describes in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable state law; and

- (c) whether the work taken as a whole lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Proposals to censor music date back to Plato’s Republic. In the 1970s, some individuals thought anti-war songs should be censored. In the 1980s, the emphasis shifted to prohibiting sexual and violent lyrics. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) also sought to fine radio stations for the broadcast of indecent speech. In general, rap and hard-core rock-n-roll have faced more censorship than other types of music. Caution must be used in this area to distinguish between governmental censorship and private censorship.

Courts have not interpreted the First Amendment rights of minors, especially in school settings , to be as broad as those of adults; their speech in school newspapers or in speaking to audiences of their peers may accordingly be censored.

Advancing technology has opened up new avenues in which access to a variety of materials, including obscenity, is open to minors, and Congress has been only partially successful in restricting such access. Parental controls on televisions and computers have provided parents and other adults with some monitoring ability, but no methods are 100 percent effective.

Censorship often increases in wartime to tamp down anti-government speech. In this 1942 photo, W. Holden White, clips items from U.S. newspapers at the Washington, D.C. headquarters of the office of censorship to determine newspaper compliance with censorship rules prescribed by the office. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Wrestling with sedition and seditious speech

In general, sedition is defined as trying to overthrow the government with intent and means to bring it about; the Supreme Court, however, has been divided over what constitutes intent and means.

In general, the government has been less tolerant of perceived sedition in times of war than in peace. The first federal attempt to censor seditious speech occurred with the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 under President John Adams.

These acts made it a federal crime to speak, write, or print criticisms of the government that were false, scandalous, or malicious. Thomas Jefferson compared the acts to witch hunts and pardoned those convicted under the statues when he succeeded Adams.

Laws attempting to reduce anti-government speech

During World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 , and the Court spent years dealing with the aftermath.

In 1919 in Schenck , the government charged that encouraging draftees not to report for duty in World War I constituted sedition. In this case, the court held that Schenck’s actions were, indeed, seditious because, in the words of Justice Holmes, they constituted a “clear and present danger” of a “substantive evil,” defined as attempting to overthrow the government, inciting riots, and destruction of life and property.

In the 1940s and 1950s, World War II and the rise of communism produced new limits on speech, and McCarthyism destroyed the lives of scores of law-abiding suspected communists.

The Smith Act of 1940 and the Internal Security Act of 1950, also known as the McCarran Act , attempted to stamp out communism in the country by establishing harsh sentences for advocating the use of violence to overthrow the government and making the Communist Party of the United States illegal.

After the al-Qaida attacks of September 11, 2001, and passage of the USA Patriot Act , the United States faced new challenges to civil liberties. As a means of fighting terrorism, government agencies began to target people openly critical of the government. The arrests of individuals suspected of knowing people considered terrorists by the government was in tension with, if not violation of, the First Amendment’s freedom of association. These detainees were held without benefit of counsel and other constitutional rights.

The George W. Bush administration and the courts have battled over the issues of warrantless wiretaps , military tribunals, and suspension of various rights guaranteed by the Constitution and the Geneva Conventions, which stipulate acceptable conditions for holding prisoners of war.

Certain forms of speech are protected from censure by governments. For instance, the First Amendment protects pure speech, defined as that which is merely expressive, descriptive, or assertive. Less clearly defined are those forms of speech referred to as speech plus, that is, speech that carries an additional connotation, such as symbolic speech. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court upheld the right of middle and high school students to wear symbolic black armbands to school to protest U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In this photo, Debbie Wallace, left, and Phyllis Sweigert, 17-year-old seniors at suburban Euclid High School in Cleveland, Ohio, display armbands they wore to school in mourning for the dead in Vietnam, Dec. 10, 1965. The girls were suspended from school until Monday. (AP Photo/Julian C. Wilson, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Expressive and symbolic speech

Certain forms of speech are protected from censure by governments. For instance, the First Amendment protects pure speech, defined as that which is merely expressive, descriptive, or assertive. The Court has held that the government may not suppress speech simply because it thinks it is offensive. Even presidents are not immune from being criticized and ridiculed.

Less clearly defined are those forms of speech referred to as speech plus, that is, speech that carries an additional connotation. This includes symbolic speech , in which meanings are conveyed without words.

In T inker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court upheld the right of middle and high school students to wear black armbands to school to protest U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

One of the most controversial examples of symbolic speech has produced a series of flag desecration cases, including Spence v. Washington (1974), Texas v. Johnson (1989), and United States v. Eichman (1990).

Despite repeated attempts by Congress to make it illegal to burn or deface the flag, the Court has held that such actions are protected. Writing for the 5-4 majority in Texas v. Johnson, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. stated, “We do not consecrate the flag by punishing its desecration, for in doing so we dilute the freedom that this cherished emblem represents.”

When speech turns into other forms of action, constitutional protections are less certain.

In R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992), the Court overturned a local hate crime statute that had been used to convict a group of boys who had burned a cross on the lawn of a black family living in a predominately white neighborhood.

The Court qualified this opinion in Virginia v. Black (2003), holding that the First Amendment did not protect such acts when their purpose was intimidation.

This article was originally published in 2009. Elizabeth Purdy, Ph.D., is an independent scholar who has published articles on subjects ranging from political science and women’s studies to economics and popular culture.

Send Feedback on this article

How To Contribute

The Free Speech Center operates with your generosity! Please donate now!

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Freedom of Speech

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 27, 2023 | Original: December 4, 2017

Freedom of speech—the right to express opinions without government restraint—is a democratic ideal that dates back to ancient Greece. In the United States, the First Amendment guarantees free speech, though the United States, like all modern democracies, places limits on this freedom. In a series of landmark cases, the U.S. Supreme Court over the years has helped to define what types of speech are—and aren’t—protected under U.S. law.

The ancient Greeks pioneered free speech as a democratic principle. The ancient Greek word “parrhesia” means “free speech,” or “to speak candidly.” The term first appeared in Greek literature around the end of the fifth century B.C.

During the classical period, parrhesia became a fundamental part of the democracy of Athens. Leaders, philosophers, playwrights and everyday Athenians were free to openly discuss politics and religion and to criticize the government in some settings.

First Amendment

In the United States, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech.

The First Amendment was adopted on December 15, 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution . The Bill of Rights provides constitutional protection for certain individual liberties, including freedoms of speech, assembly and worship.

The First Amendment doesn’t specify what exactly is meant by freedom of speech. Defining what types of speech should and shouldn’t be protected by law has fallen largely to the courts.

In general, the First Amendment guarantees the right to express ideas and information. On a basic level, it means that people can express an opinion (even an unpopular or unsavory one) without fear of government censorship.

It protects all forms of communication, from speeches to art and other media.

Flag Burning

While freedom of speech pertains mostly to the spoken or written word, it also protects some forms of symbolic speech. Symbolic speech is an action that expresses an idea.

Flag burning is an example of symbolic speech that is protected under the First Amendment. Gregory Lee Johnson, a youth communist, burned a flag during the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas to protest the Reagan administration.

The U.S. Supreme Court , in 1990, reversed a Texas court’s conviction that Johnson broke the law by desecrating the flag. Texas v. Johnson invalidated statutes in Texas and 47 other states prohibiting flag burning.

When Isn’t Speech Protected?

Not all speech is protected under the First Amendment.

Forms of speech that aren’t protected include:

- Obscene material such as child pornography

- Plagiarism of copyrighted material

- Defamation (libel and slander)

- True threats

Speech inciting illegal actions or soliciting others to commit crimes aren’t protected under the First Amendment, either.

The Supreme Court decided a series of cases in 1919 that helped to define the limitations of free speech. Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917, shortly after the United States entered into World War I . The law prohibited interference in military operations or recruitment.

Socialist Party activist Charles Schenck was arrested under the Espionage Act after he distributed fliers urging young men to dodge the draft. The Supreme Court upheld his conviction by creating the “clear and present danger” standard, explaining when the government is allowed to limit free speech. In this case, they viewed draft resistant as dangerous to national security.

American labor leader and Socialist Party activist Eugene Debs also was arrested under the Espionage Act after giving a speech in 1918 encouraging others not to join the military. Debs argued that he was exercising his right to free speech and that the Espionage Act of 1917 was unconstitutional. In Debs v. United States the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act.

Freedom of Expression

The Supreme Court has interpreted artistic freedom broadly as a form of free speech.

In most cases, freedom of expression may be restricted only if it will cause direct and imminent harm. Shouting “fire!” in a crowded theater and causing a stampede would be an example of direct and imminent harm.

In deciding cases involving artistic freedom of expression the Supreme Court leans on a principle called “content neutrality.” Content neutrality means the government can’t censor or restrict expression just because some segment of the population finds the content offensive.

Free Speech in Schools

In 1965, students at a public high school in Des Moines, Iowa , organized a silent protest against the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to protest the fighting. The students were suspended from school. The principal argued that the armbands were a distraction and could possibly lead to danger for the students.

The Supreme Court didn’t bite—they ruled in favor of the students’ right to wear the armbands as a form of free speech in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District . The case set the standard for free speech in schools. However, First Amendment rights typically don’t apply in private schools.

What does free speech mean?; United States Courts . Tinker v. Des Moines; United States Courts . Freedom of expression in the arts and entertainment; ACLU .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3: Censorship and Freedom of Speech

Learning Objectives

- Explain the FCC’s process of classifying material as indecent, obscene, or profane.

- Describe how the Hays Code affected 20th-century American mass media.

To fully understand the issues of censorship and freedom of speech and how they apply to modern media, we must first explore the terms themselves. Censorship is defined as suppressing or removing anything deemed objectionable. A common, everyday example can be found on the radio or television, where potentially offensive words are “bleeped” out. More controversial is censorship at a political or religious level. If you’ve ever been banned from reading a book in school, or watched a “clean” version of a movie on an airplane, you’ve experienced censorship.

Much as media legislation can be controversial due to First Amendment protections, censorship in the media is often hotly debated. The First Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press” (Case Summaries, n.d.). Under this definition, the term “speech” extends to a broader sense of “expression,” meaning verbal, nonverbal, visual, or symbolic expression. Historically, many individuals have cited the First Amendment when protesting FCC decisions to censor certain media products or programs. However, what many people do not realize is that U.S. law establishes several exceptions to free speech, including defamation, hate speech, breach of the peace, incitement to crime, sedition, and obscenity.

Classifying Material as Indecent, Obscene, or Profane

To comply with U.S. law, the FCC prohibits broadcasters from airing obscene programming. The FCC decides whether or not material is obscene by using a three-prong test.

Obscene material:

- causes the average person to have lustful or sexual thoughts;

- depicts lawfully offensive sexual conduct; and

- lacks literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

Material meeting all of these criteria is officially considered obscene and usually applies to hard-core pornography (FCC, 2022). “Indecent” material, on the other hand, is protected by the First Amendment and cannot be banned entirely.

Indecent material:

- contains graphic sexual or excretory depictions;

- dwells at length on depictions of sexual or excretory organs; and

- is used simply to shock or arouse an audience.

Material deemed indecent cannot be broadcast between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m., to make it less likely that children will be exposed to it (FCC, 2022).

These classifications symbolize the media’s long struggle with what is considered appropriate and inappropriate material. Despite the existence of the guidelines, however, the process of categorizing materials is a long and arduous one. Each year, the FCC receives thousands of complaints regarding obscene, indecent, or profane programming. While the agency ultimately defines most programs cited in the complaints as appropriate, many complaints require in-depth investigation and may result in fines called notices of apparent liability (NAL) or federal investigation.

Violence and Sex: Taboos in Entertainment

Although popular memory thinks of old black-and-white movies as tame or sanitized, many early filmmakers filled their movies with sexual or violent content. Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 silent film The Great Train Robbery , for example, is known for expressing “the appealing, deeply embedded nature of violence in the frontier experience and the American civilizing process,” and showcases “the rather spontaneous way that the attendant violence appears in the earliest developments of cinema” (Film Reference, n.d.). The film ends with an image of a gunman firing a revolver directly at the camera, demonstrating that cinema’s fascination with violence was present even 100 years ago.

Porter was not the only U.S. filmmaker working during the early years of cinema to employ graphic violence. Films such as Intolerance (1916) and The Birth of a Nation (1915) are notorious for their overt portrayals of violent activities. The director of both films, D. W. Griffith, intentionally portrayed content graphically because he “believed that the portrayal of violence must be uncompromised to show its consequences for humanity” (Film Reference, n.d.).

Although audiences responded eagerly to the new medium of film, some naysayers believed that Hollywood films and their associated hedonistic culture was a negative moral influence. This changed during the 1930s with the implementation of the Hays Code . Formally termed the Motion Picture Production Code of 1930, the code is popularly known by the name of its author, Will Hays, the chairman of the industry’s self-regulatory Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association (MPPDA), which was founded in 1922 to “police all in-house productions” (Film Reference, n.d.). Created to forestall what was perceived to be looming governmental control over the industry, the Hays Code was, essentially, Hollywood self-censorship.