- Social Science

- Grounded Theory

The Place of the Literature Review in Grounded Theory Research

- International Journal of Social Research Methodology 14(2):111-124

- 14(2):111-124

- Dublin City University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Necati Cemaloğlu

- Yalew Alemayehu Abbay

- Yong-Hoon Son

- Kyu-Chul Lee

- Yuying Tang

- Nantana Chavasirikultol

- Trakul Chitwattanakorn

- Jamnean Joungtrakul

- Benchmark Int J

- Masoud Bagherpasandi

- Zohreh Hajiha

- B.G. Glaser

- Anselm L. Strauss

- A.L. Strauss

- Kathleen M. Eisenhardt

- A.M. Huberman

- N.K. Denzin

- Y.S. Lincoln

- M. Saunders

- A. Thornhill

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Grounded Theory In Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Grounded theory is a useful approach when you want to develop a new theory based on real-world data Instead of starting with a pre-existing theory, grounded theory lets the data guide the development of your theory.

What Is Grounded Theory?

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967.

- Data shapes the theory: Instead of trying to prove an existing theory, you let the data guide your findings.

- No guessing games: You don’t start with assumptions or try to confirm your own biases.

- Data collection and analysis happen together: You analyze information as you gather it, which helps you decide what data to collect next.

It is important to note that grounded theory is an inductive approach where a theory is developed from collected real-world data rather than trying to prove or disprove a hypothesis like in a deductive scientific approach

You gather information, look for patterns, and use those patterns to develop an explanation.

It is a way to understand why people do things and how those actions create patterns. Imagine you’re trying to figure out why your friends love a certain video game.

Instead of asking an adult, you observe your friends while they’re playing, listen to them talk about it, and maybe even play a little yourself. By studying their actions and words, you’re using grounded theory to build an understanding of their behavior.

This qualitative method of research focuses on real-life experiences and observations, letting theories emerge naturally from the data collected, like piecing together a puzzle without knowing the final image.

When should you use grounded theory?

Grounded theory research is useful for beginning researchers, particularly graduate students, because it offers a clear and flexible framework for conducting a study on a new topic.

Grounded theory works best when existing theories are either insufficient or nonexistent for the topic at hand.

Since grounded theory is a continuously evolving process, researchers collect and analyze data until theoretical saturation is reached or no new insights can be gained.

What is the final product of a GT study?

The final product of a grounded theory (GT) study is an integrated and comprehensive grounded theory that explains a process or scheme associated with a phenomenon.

The quality of a GT study is judged on whether it produces this middle-range theory

Middle-range theories are sort of like explanations that focus on a specific part of society or a particular event. They don’t try to explain everything in the world. Instead, they zero in on things happening in certain groups, cultures, or situations.

Think of it like this: a grand theory is like trying to understand all of weather at once, but a middle-range theory is like focusing on how hurricanes form.

Here are a few examples of what middle-range theories might try to explain:

- How people deal with feeling anxious in social situations.

- How people act and interact at work.

- How teachers handle students who are misbehaving in class.

Core Components of Grounded Theory

This terminology reflects the iterative, inductive, and comparative nature of grounded theory, which distinguishes it from other research approaches.

- Theoretical Sampling: The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study. The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

- Theoretical Sensitivity: Researchers need to be aware of their preconceptions going into a study and understand how those preconceptions could influence the research. However, it is not possible to completely separate a researcher’s history and experience from the construction of a theory.

- Coding: Coding is the process of analyzing qualitative data (usually text) by assigning labels (codes) to chunks of data that capture their essence or meaning. It allows you to condense, organize and interpret your data.

- Core Category: The core category encapsulates and explains the grounded theory as a whole. Researchers identify a core category to focus on during the later stages of their research.

- Memos: Researchers use memos to record their thoughts and ideas about the data, explore relationships between codes and categories, and document the development of the emerging grounded theory. Memos support the development of theory by tracking emerging themes and patterns.

- Theoretical Saturation: This term refers to the point in a grounded theory study when collecting additional data does not yield any new theoretical insights. The researcher continues the process of collecting and analyzing data until theoretical saturation is reached.

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data.

Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss first introduced grounded theory in 1967 in their book, The Discovery of Grounded Theory .

Their aim was to create a research method that prioritized real-world data to understand social behavior.

However, their approaches diverged over time, leading to two distinct versions: Glaserian and Straussian grounded theory.

The different versions of grounded theory diverge in their approaches to coding , theory construction, and the use of literature.

All versions of grounded theory share the goal of generating a middle-range theory that explains a social process or phenomenon.

They also emphasize the importance of theoretical sampling , constant comparative analysis , and theoretical saturation in developing a robust theory

Glaserian Grounded Theory

Glaserian grounded theory emphasizes the emergence of theory from data and discourages the use of pre-existing literature.

Glaser believed that adopting a specific philosophical or disciplinary perspective reduces the broader potential of grounded theory.

For Glaser, prior understandings should be based on the general problem area and reading very wide to alert or sensitize one to a wide range of possibilities.

It prioritizes parsimony , scope , and modifiability in the resulting theory

Straussian Grounded Theory

Strauss and Corbin (1990) focused on developing the analytic techniques and providing guidance to novice researchers.

Straussian grounded theory utilizes a more structured approach to coding and analysis and acknowledges the role of the literature in shaping research.

It acknowledges the role of deduction and validation in addition to induction.

Strauss and Corbin also emphasize the use of unstructured interview questions to encourage participants to speak freely

Critics of this approach believe it produced a rigidity never intended for grounded theory.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This version, primarily associated with Charmaz, recognizes that knowledge is situated, partial, provisional, and socially constructed. It emphasizes abstract and conceptual understandings rather than explanations.

Kathy Charmaz expanded on original versions of GT, emphasizing the researcher’s role in interpreting findings

Constructivist grounded theory acknowledges the researcher’s influence on the research process and the co-creation of knowledge with participants

Situational Analysis

Developed by Clarke, this version builds upon Straussian and Constructivist grounded theory and incorporates postmodern , poststructuralist , and posthumanist perspectives.

Situational analysis incorporates postmodern perspectives and considers the role of nonhuman actors

It introduces the method of mapping to analyze complex situations and emphasizes both human and nonhuman elements .

- Discover New Insights: Grounded theory lets you uncover new theories based on what your data reveals, not just on pre-existing ideas.

- Data-Driven Results: Your conclusions are firmly rooted in the data you’ve gathered, ensuring they reflect reality. This close relationship between data and findings is a key factor in establishing trustworthiness.

- Avoids Bias: Because gathering data and analyzing it are closely intertwined, researchers are truly observing what emerges from data, and are less likely to let their preconceptions color the findings.

- Streamlined data gathering and analysis: Analyzing and collecting data go hand in hand. Data is collected, analyzed, and as you gain insight from analysis, you continue gathering more data.

- Synthesize Findings : By applying grounded theory to a qualitative metasynthesis , researchers can move beyond a simple aggregation of findings and generate a higher-level understanding of the phenomena being studied.

Limitations

- Time-Consuming: Analyzing qualitative data can be like searching for a needle in a haystack; it requires careful examination and can be quite time-consuming, especially without software assistance6.

- Potential for Bias: Despite safeguards, researchers may unintentionally influence their analysis due to personal experiences.

- Data Quality: The success of grounded theory hinges on complete and accurate data; poor quality can lead to faulty conclusions.

Practical Steps

Grounded theory can be conducted by individual researchers or research teams. If working in a team, it’s important to communicate regularly and ensure everyone is using the same coding system.

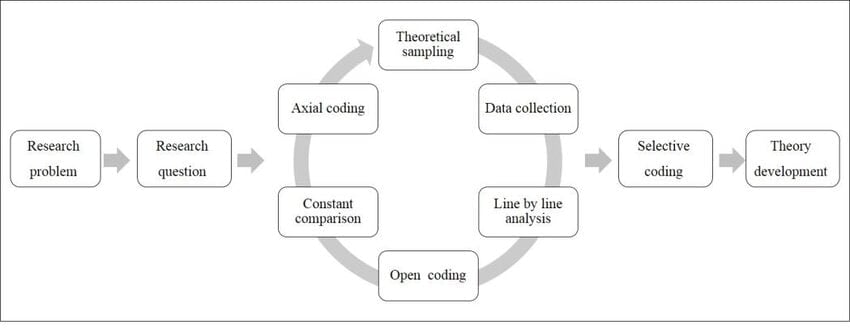

Grounded theory research is typically an iterative process. This means that researchers may move back and forth between these steps as they collect and analyze data.

Instead of doing everything in order, you repeat the steps over and over.

This cycle keeps going, which is why grounded theory is called a circular process.

Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories emerge. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

Theoretical sampling, collecting sufficient and rich data, and theoretical saturation help the grounded theorist to avoid a lack of “groundedness,” incomplete findings, and “premature closure.

1. Planning and Philosophical Considerations

Begin by considering the phenomenon you want to study and assess the current knowledge surrounding it.

However, refrain from detailing the specific aspects you seek to uncover about the phenomenon to prevent pre-existing assumptions from skewing the research.

- Discern a personal philosophical position. Before beginning a research study, it is important to consider your philosophical stance and how you view the world, including the nature of reality and the relationship between the researcher and the participant. This will inform the methodological choices made throughout the study.

- Investigate methodological possibilities. Explore different research methods that align with both the philosophical stance and research goals of the study.

- Plan the study. Determine the research question, how to collect data, and from whom to collect data.

- Conduct a literature review. The literature review is an ongoing process throughout the study. It is important to avoid duplicating existing research and to consider previous studies, concepts, and interpretations that relate to the emerging codes and categories in the developing grounded theory.

2. Recruit participants using theoretical sampling

Initially, select participants who are readily available ( convenience sampling ) or those recommended by existing participants ( snowball sampling ).

As the analysis progresses, transition to theoretical sampling , involving the deliberate selection of participants and data sources to refine your emerging theory.

This method is used to refine and develop a grounded theory. The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study.

This could mean recruiting participants who can shed light on gaps in your understanding uncovered during the initial data analysis.

Theoretical sampling guides further data collection by identifying participants or data sources that can provide insights into gaps in the emerging theory

The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

Theoretical sampling starts early in a GT study and generally requires the researcher to make amendments to their ethics approvals to accommodate new participant groups.

3. Collect Data

The researcher might use interviews, focus groups, observations, or a combination of methods to collect qualitative data.

- Observations : Watching and recording phenomena as they occur. Can be participant (researcher actively involved) or non-participant (researcher tries not to influence behaviors), and covert (participants unaware) or overt (participants aware).

- Interviews : One-on-one conversations to understand participants’ experiences. Can be structured (predetermined questions), informal (casual conversations), or semi-structured (flexible structure to explore emerging issues).

- Focus groups : Dynamic discussions with 4-10 participants sharing characteristics, moderated by the researcher using a topic guide.

- Ethnography : Studying a group’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment through observations, field notes, and interviews. Researchers immerse themselves in the community or organization for an in-depth understanding.

4. Begin open coding as soon as data collection starts

Open coding is the first stage of coding in grounded theory, where you carefully examine and label segments of your data to identify initial concepts and ideas.

This process involves scrutinizing the data and creating codes grounded in the data itself.

The initial codes stay close to the data, aiming to capture and summarize critically and analytically what is happening in the data

To begin open coding, read through your data, such as interview transcripts, to gain a comprehensive understanding of what is being conveyed.

As you encounter segments of data that represent a distinct idea, concept, or action, you assign a code to that segment. These codes act as descriptive labels summarizing the meaning of the data segment.

For instance, if you were analyzing interview data about experiences with a new medication, a segment of data might describe a participant’s difficulty sleeping after taking the medication. This segment could be labeled with the code “trouble sleeping”

Open coding is a crucial step in grounded theory because it allows you to break down the data into manageable units and begin to see patterns and themes emerge.

As you continue coding, you constantly compare different segments of data to refine your understanding of existing codes and identify new ones.

For instance, excerpts describing difficulties with sleep might be grouped under the code “trouble sleeping”.

This iterative process of comparing data and refining codes helps ensure the codes accurately reflect the data.

Open coding is about staying close to the data, using in vivo terms or gerunds to maintain a sense of action and process

5. Reflect on thoughts and contradictions by writing grounded theory memos during analysis

During open coding, it’s crucial to engage in memo writing. Memos serve as your “notes to self”, allowing you to reflect on the coding process, note emerging patterns, and ask analytical questions about the data.

Document your thoughts, questions, and insights in memos throughout the research process.

These memos serve multiple purposes: tracing your thought process, promoting reflexivity (self-reflection), facilitating collaboration if working in a team, and supporting theory development.

Early memos tend to be shorter and less conceptual, often serving as “preparatory” notes. Later memos become more analytical and conceptual as the research progresses.

Memo Writing

- Reflexivity and Recognizing Assumptions: Researchers should acknowledge the influence of their own experiences and assumptions on the research process. Articulating these assumptions, perhaps through memos, can enhance the transparency and trustworthiness of the study.

- Write memos throughout the research process. Memo writing should occur throughout the entire research process, beginning with initial coding.67 Memos help make sense of the data and transition between coding phases.8

- Ask analytic questions in early memos. Memos should include questions, reflections, and notes to explore in subsequent data collection and analysis.8

- Refine memos throughout the process. Early memos will be shorter and less conceptual, but will become longer and more developed in later stages of the research process.7 Later memos should begin to develop provisional categories.

6. Group codes into categories using axial coding

Axial coding is the process of identifying connections between codes, grouping them together into categories to reveal relationships within the data.

Axial coding seeks to find the axes that connect various codes together.

For example, in research on school bullying, focused codes such as “Doubting oneself, getting low self-confidence, starting to agree with bullies” and “Getting lower self-confidence; blaming oneself” could be grouped together into a broader category representing the impact of bullying on self-perception.

Similarly, codes such as “Being left by friends” and “Avoiding school; feeling lonely and isolated” could be grouped into a category related to the social consequences of bullying.

These categories then become part of the emerging grounded theory, explaining the multifaceted aspects of the phenomenon.

Qualitative data analysis software often represents these categories as nested codes, visually demonstrating the hierarchy and interconnectedness of the concepts.

This hierarchical structure helps researchers organize their data, identify patterns, and develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between different aspects of the phenomenon being studied.

This process of axial coding is crucial for moving beyond descriptive accounts of the data towards a more theoretically rich and explanatory grounded theory.

7. Define the core category using selective coding

During selective coding , the final development stage of grounded theory analysis, a researcher focuses on developing a detailed and integrated theory by selecting a core category and connecting it to other categories developed during earlier coding stages.

The core category is the central concept that links together the various categories and subcategories identified in the data and forms the foundation of the emergent grounded theory.

This core category will encapsulate the main theme of your grounded theory, that encompasses and elucidates the overarching process or phenomenon under investigation.

This phase involves a concentrated effort to refine and integrate categories, ensuring they align with the core category and contribute to the overall explanatory power of the theory.

The theory should comprehensively describe the process or scheme related to the phenomenon being studied.

For example, in a study on school bullying, if the core category is “victimization journey,” the researcher would selectively code data related to different stages of this journey, the factors contributing to each stage, and the consequences of experiencing these stages.

This might involve analyzing how victims initially attribute blame, their coping mechanisms, and the long-term impact of bullying on their self-perception.

Continue collecting data and analyzing until you reach theoretical saturation

Selective coding focuses on developing and saturating this core category, leading to a cohesive and integrated theory.

Through selective coding, researchers aim to achieve theoretical saturation, meaning no new properties or insights emerge from further data analysis.

This signifies that the core category and its related categories are well-defined, and the connections between them are thoroughly explored.

This rigorous process strengthens the trustworthiness of the findings by ensuring the theory is comprehensive and grounded in a rich dataset.

It’s important to note that while a grounded theory seeks to provide a comprehensive explanation, it remains grounded in the data.

The theory’s scope is limited to the specific phenomenon and context studied, and the researcher acknowledges that new data or perspectives might lead to modifications or refinements of the theory

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data. There are different methods for comparing excerpts from interviews, for example, a researcher can compare excerpts from the same person, or excerpts from different people. This process is ongoing and iterative, and it continues until the researcher has developed a comprehensive and well-supported grounded theory.

- Continue until reaching theoretical saturation : Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

8. Theoretical coding and model development

Theoretical coding is a process in grounded theory where researchers use advanced abstractions, often from existing theories, to explain the relationships found in their data.

Theoretical coding often occurs later in the research process and involves using existing theories to explain the connections between codes and categories.

This process helps to strengthen the explanatory power of the grounded theory. Theoretical coding should not be confused with simply describing the data; instead, it aims to explain the phenomenon being studied, distinguishing grounded theory from purely descriptive research.

Using the developed codes, categories, and core category, create a model illustrating the process or phenomenon.

Here is some advice for novice researchers on how to apply theoretical coding:

- Begin with data analysis: Don’t start with a pre-determined theory. Instead, allow the theory to emerge from your data through careful analysis and coding.

- Use existing theories as a guide: While the theory should primarily emerge from your data, you can use existing theories from any discipline to help explain the connections you are seeing between your categories. This demonstrates how your research builds on established knowledge.

- Use Glaser’s coding families: Consider applying Glaser’s (1978) coding families in the later stages of analysis as a simple way to begin theoretical coding. Remember that your analysis should guide which theoretical codes are most appropriate.

- Keep it simple: Theoretical coding doesn’t need to be overly complex. Focus on finding an existing theory that effectively explains the relationships you have identified in your data.

- Be transparent: Clearly articulate the existing theory you are using and how it explains the connections between your categories.

- Theoretical coding is an iterative process : Remain open to revising your chosen theoretical codes as your analysis deepens and your grounded theory evolves.

9. Write your grounded theory

Present your findings in a clear and accessible manner, ensuring the theory is rooted in the data and explains the relationships between the identified concepts and categories.

The end product of this process is a well-defined, integrated grounded theory that explains a process or scheme related to the phenomenon studied.

- Develop a dissemination plan : Determine how to share the research findings with others.

- Evaluate and implement : Reflect on the research process and quality of findings, then share findings with relevant audiences in service of making a difference in the world

Reading List

Grounded Theory Review : This is an international journal that publishes articles on grounded theory.

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Clarke, A. E. (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn . Symbolic interaction , 26 (4), 553-576.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity . University of California.

- Glaser, B. G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding . Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory. In Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: qualitative social research (Vol. 5, No. 2).

- Charmaz, K. (2012). The power and potential of grounded theory. Medical sociology online , 6 (3), 2-15.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1965). Awareness of dying. New Brunswick. NJ: Aldine. This was the first published grounded theory study

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Routledge.

- Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (1997). Using grounded theory in psychological research. In N. Hayes (Ed.), Doing qualitative analysis in psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- Science for Patients

- Invited Commentaries

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, distinguishing features of grounded theory, the role and timing of the literature review.

- < Previous

Grounded theory: what makes a grounded theory study?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Carley Turner, Felicity Astin, Grounded theory: what makes a grounded theory study?, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , Volume 20, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 285–289, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvaa034

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Grounded theory (GT) is both a research method and a research methodology. There are several different ways of doing GT which reflect the different viewpoints of the originators. For those who are new to this approach to conducting qualitative research, this can be confusing. In this article, we outline the key characteristics of GT and describe the role of the literature review in three common GT approaches, illustrated using exemplar studies.

Describing the key characteristics of a Grounded theory (GT) study.

Considering the role and timing of the literature review in different GT approaches.

Qualitative research is a cornerstone in cardiovascular research. It gives insights in why particular phenomena occur or what underlying mechanisms are. 1 Over the past 2 years, the European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing published 20 qualitative studies. 2–21 These studies used methods such as content analysis, ethnography, or phenomenology. Grounded theory (GT) has been used to a lesser extent.

Grounded theory is both a methodology and a method used in qualitative research ( Table 1 ). It is a research approach used to gain an emic insight into a phenomenon. In simple terms, this means understanding the perspective, or point of view, of an ‘insider’, those who have experience of the phenomenon. 22 Grounded theory is a research approach that originated from the social sciences but has been used in education and health research. The focus of GT is to generate theory that is grounded in data and shaped by the views of participants, thereby moving beyond description and towards theoretical explanation of a process or phenomenon. 23

Grounded theory as a method and methodology

| . | Methodology . | Method . |

|---|---|---|

| Framework of principles on which the methods are based. | Strategy for conducting the research. Methods outline how data will be collected, analysed, and interpreted. | |

| GT application | Researcher openness, with an inductive approach to data. Theory can be generated based on data. | Concurrent data collection and analysis, use of codes and memos for data analysis. |

| . | Methodology . | Method . |

|---|---|---|

| Framework of principles on which the methods are based. | Strategy for conducting the research. Methods outline how data will be collected, analysed, and interpreted. | |

| GT application | Researcher openness, with an inductive approach to data. Theory can be generated based on data. | Concurrent data collection and analysis, use of codes and memos for data analysis. |

One of the key issues with using GT, particularly for novices, is understanding the different approaches that have evolved as each specific GT approach is slightly different.

The tradition of GT began with the seminal text about classic GT written by Glaser and Strauss, 24 but since then GT has evolved into several different types. The approach to GT chosen by the researcher depends upon an understanding of the epistemological underpinnings of the different approaches, the match with the topic under investigation and the researcher’s own stance. Whilst GT is frequently used in applied health research, very few studies detail which GT approach has been used, how and why. Sometimes published studies claim to use GT methodology but the approaches that form the foundation of GT are not reported. This may be due to the word limit in academic journals or because legitimate GT approaches have not been followed. Either way, there is a lack of clarity about the practical application of GT. The purpose of this article is to outline the distinguishing characteristics of GT and outline practical considerations for the novice researcher regarding the place of the literature review in GT.

There are several distinguishing features of GT, as outlined by Sbaraini et al. 25 The first is that GT research is conducted through an inductive process. This means that the researcher is developing theory rather than testing it and must therefore remain ‘open’ throughout the study. In essence, this means that the researcher has no preconceived ideas about the findings. Taking an inductive approach means that the focus of the research may evolve over time as the researchers understand what is important to their participants through the data collection and analysis process.

With regards to data analysis, the use of coding is initially used to break down data into smaller components and labelling them to capture the essence of the data. The codes are compared to one another to understand and explain any variation in the data before they are combined to form more abstract categories. Memos are used to record and develop the researcher’s analysis of the data, including the detail behind the comparisons made between categories. Memos can stimulate the researcher’s thinking, as well as capturing the researcher’s ideas during data collection and analysis.

A further feature for data analysis in a GT study is the simultaneous data analysis and sampling to facilitate theoretical sampling. This means that as data analysis progresses participants are purposefully selected who may have characteristics or experiences that have arisen as being of interest from data collection and analysis so far. Questions in the topic guide may also be modified to follow a specific line of inquiry, test ideas and interpretations, or fill gaps in the analysis to build an emerging substantive theory. This evolving and non-linear methodology is to allow the evolution of the study as indicated by data, rather than analysing at the end of data collection. This approach to data analysis supports the researcher to take an inductive approach as discussed above.

Theoretical sampling facilitates the construction of theory until theoretical saturation is reached. Theoretical saturation is when all the concepts that form the theory being developed are well understood and grounded in data. Finally, the results are expressed as a theory where a set of concepts are related to one another and provide a framework for making predictions. 26 These key features of GT are summarized in Table 2 .

Distinguishing features of a GT study (adapted from Sbaraini et al. 25 )

| Distinguishing feature . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Openness | Grounded Theory is concerned with the development of theory rather than testing it. The researcher has no preconceived ideas about the findings, and the study evolves over time. |

| Concurrent data collection and data analysis | Data analysis occurs at the same time as data collection. |

| Coding | Data are broken down into smaller components and assigned a label to capture the essence of the data. |

| Memos | Memos are a record of the researcher’s ideas and thoughts during data collection and analysis. Use of memos helps to develop the researcher’s analysis. |

| Theoretical sampling | Purposeful selection of participants who may have characteristics or experiences that have arisen as being of interest from data collection and analysis. Theoretical sampling also includes modifications to the topic guide to allow the researcher to explore ideas arising from the interviews or fill gaps in the developing theory. |

| Theoretical saturation | When all the concepts that form the theory are well understood and grounded in data. |

| Theory generation | The results of the study are expressed as a substantive theory. The key aim of GT is to generate a substantive theory, in other words, a theory to explain specific population experiences of a phenomenon. |

| Distinguishing feature . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Openness | Grounded Theory is concerned with the development of theory rather than testing it. The researcher has no preconceived ideas about the findings, and the study evolves over time. |

| Concurrent data collection and data analysis | Data analysis occurs at the same time as data collection. |

| Coding | Data are broken down into smaller components and assigned a label to capture the essence of the data. |

| Memos | Memos are a record of the researcher’s ideas and thoughts during data collection and analysis. Use of memos helps to develop the researcher’s analysis. |

| Theoretical sampling | Purposeful selection of participants who may have characteristics or experiences that have arisen as being of interest from data collection and analysis. Theoretical sampling also includes modifications to the topic guide to allow the researcher to explore ideas arising from the interviews or fill gaps in the developing theory. |

| Theoretical saturation | When all the concepts that form the theory are well understood and grounded in data. |

| Theory generation | The results of the study are expressed as a substantive theory. The key aim of GT is to generate a substantive theory, in other words, a theory to explain specific population experiences of a phenomenon. |

The identification of a gap in the published literature is typically a requirement of successful doctoral studies and grant applications. However, in GT research there are different views about the role and timing of the literature review.

For researchers using classic Glaserian GT, the recommended approach is that the published literature should not be reviewed until data collection, analysis and theory development has been completed. 24 The rationale for the delay of the literature review is to enable the researcher to remain ‘open’ to discover theory emerging from data and free from contamination by avoiding forcing data into pre-conceived concepts derived from other studies. Furthermore, because the researcher is ‘open’ to whichever direction the data takes they cannot know in advance which aspects of the literature will be relevant to their study. 27

In Glaserian GT, the emerging concepts and theory from data analysis inform the scope of the literature review which is conducted after theory development. 24 This approach to the literature review aligns with the rather positivist stance of Glaser in which the researcher aims to remain free of assumptions so that the theory that emerges from the data is not influenced by the researcher. Reviewing the literature prior to data analysis would risk theory being imposed on the data. Perhaps counterintuitively, Glaser does recommend reading literature in unrelated fields to understand as many theoretical codes as possible. 28 However, it is unclear how this is different to reading literature directly related to the topic and could potentially still lead to the contamination of the theory arising from data that delaying the literature review is intended to avoid. It is also problematic regarding the governance processes around research, whereby funders and ethics committees would expect at least an overview of the existing literature as part of the justification for the study.

A study by Bergman et al. 29 used a classic Glaserian GT approach to examine and identify the motive of power in myocardial infarction patients’ rehabilitation process. Whilst the key characteristics of GT were evident in the way the study was conducted, there was no discussion about how the literature review contributed to the final theory. This may have been due to the word limit but illustrates the challenges that novice researchers may have in understanding where the literature review fits in studies using GT approaches.

In Straussian GT, a more pragmatic approach to the literature view is adopted. Strauss and Corbin 30 recognized that the researcher has prior knowledge, including that of the literature, before starting their research. They did not recommend dissociation from the literature, but rather that the literature be used across the various stages of the research. Published literature could identify important areas that could contribute to theory development, support useful comparisons in the data and stimulate further questions during the analytical process. According to Strauss and Corbin, researchers should be mindful about how published work could influence theory development. Whilst visiting the literature prior to data collection was believed to enhance data analysis, it was not thought necessary to review all the literature beforehand, but rather revisit the literature at later stages in the research process. 30

A study published by Salminen-Tuomaala et al. 31 used a Straussian GT approach to explore factors that influenced the way patients coped with hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. The authors described a reflexive process in which the researcher noted down their preconceived ideas about the topic as part of the data analysis process. The literature review was conducted after data analysis.

The most recent step in the evolution of GT is the move towards a constructivist epistemological stance advocated by Charmaz. 32 In simple terms, this means that the underlying approach reflects the belief that theories cannot be discovered but are instead constructed by the researcher and their interactions with the participants and data. As the researcher plays a central role in the construction of the GT, their background, personal views, and culture will influence this process and the way data are analysed. For this reason, it is important to be explicit about these preconceptions and aim to maintain an open mind through reflexivity. 32 Therefore, engaging in a preliminary literature review and using this information to compare and contrast with findings from the research undertaken is desirable, alongside completing a comprehensive literature review after data analysis with a specific aim to present the GT.

A study published by Odell et al. 33 used the modified GT approach recommended by Charmaz 32 to study patients’ experiences of restenosis after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. The authors described the different GT approaches and key features of GT methodology which clearly informed the conduct of the study. However, there was no detail about how the literature review was used to shape the data analysis process and findings.

A solution: be clear on the approach taken to the literature review and why

Despite the clear differences in the approach to the literature review in GT, there appears to be a lack of precise guidance for novice researchers regarding how in depth or exhaustive a preliminary literature review should be. This lack of guidance can lead to a variety of different approaches as evidenced in the GT studies we have cited as examples, which is a challenge for the novice researcher. This uncertainty is further compounded by the concurrent approach to data collection and analysis which allows for the research focus to evolve as the study progresses. The complexity of the research process and the role and timing of the literature review is summarized in Figure 1 .

Literature review in Grounded Theory.

Taking a pragmatic approach, researchers will need to familiarize themselves with the literature to receive funding and approval for their study. This preliminary literature review can be followed up after data analysis by a more comprehensive review of the literature to help support the theory that was developed from the data. The key is to ensure transparency in reporting how the literature review has been used to develop the theory. The preliminary literature review can be used to set the scene for the research as part of the introduction, and the more extensive literature review can then be used during the discussion section to compare the theory developed from the data with existing literature, as per Probyn et al. 34

Whilst this pragmatic approach aligns with Straussian GT and Charmaz’s constructivist GT, it is at odds with Glaserian GT. Therefore, if Glaserian GT is chosen, the researcher should be explicit about deviation and provide a rationale.

Word count for journal articles is often a limiting factor in how much detail is included in why certain methodologies are used. Submitting detail about the methodology and rationale behind it can be presented as online supplementary material, thereby allowing interested readers to access further information about how and why the research was executed.

The use of GT as a methodology and method can shed light on areas where little knowledge is already known, generating theory directly from data. The traditional format of a published article does not always reflect the iterative approach to the literature review and data collection and analysis in GT. This can generate tension between how the research is presented in relation to how it was conducted. However, one simple way to ensure clarity in reporting is to be transparent in how the literature review is used.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest : The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Greenhalgh T , Taylor R. Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) . Br Med J 1997 ; 315 : 740 – 743 .

Google Scholar

Wilson RE , Rush KL , Reid RC , et al. The symptom experience of early and late treatment seekers before an atrial fibrillation diagnosis . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2021 ; 20 :231--242.

Lauck SB , Achtem L , Borregaard B , et al. Can you see frailty? An exploratory study of the use of a patient photograph in the transcatheter aortic valve implantation programme . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2021 ; 20 :252--260.

Sundelin R , Bergsten C , Tornvall P , Lyngå, P. et al. Self-rated stress and experience in patients with Takotsubo syndrome: a mixed methods study . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; doi: 10.1177/1474515120919387.

Janssen DJ , Ament SM , Boyne J , et al. Characteristics for a tool for timely identification of palliative needs in heart failure: the views of Dutch patients, their families and healthcare professionals . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; doi: 10.1177/1474515120918962.

Steffen EM , Timotijevic L , Coyle A. A qualitative analysis of psychosocial needs and support impacts in families affected by young sudden cardiac death: the role of community and peer support . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; doi: 10.1177/1474515120922347.

Molzahn AE , Sheilds L , Bruce A , Schick-Makaroff K , Antonio M , Clark AM. Life and priorities before death: a narrative inquiry of uncertainty and end of life in people with heart failure and their family members . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; 19 : 629 – 637 .

Wistrand C , Nilsson U , Sundqvist A-S. Patient experience of preheated and room temperature skin disinfection prior to cardiac device implantation: a randomised controlled trial . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; 19 : 529 – 536 .

Widell C , Andréen S , Albertsson P , Axelsson ÅB. Octogenarian preferences and expectations for acute coronary syndrome treatment . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; 19 : 521 – 528 .

Ferguson C , George A , Villarosa AR , Kong AC , Bhole S , Ajwani S. Exploring nursing and allied health perspectives of quality oral care after stroke: a qualitative study . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020 ; 19 : 505 – 512 .

Sutantri S , Cuthill F , Holloway A. ‘ A bridge to normal’: a qualitative study of Indonesian women’s attendance in a phase two cardiac rehabilitation programme . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 , doi: 10.1177/1474515119864208.

Liu X-L , Willis K , Fulbrook P , Wu C-J(J) , Shi Y , Johnson M. Factors influencing self-management priority setting and decision-making among Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 700 – 710 .

Wingham J , Frost J , Britten N , Greaves C , Abraham C , Warren FC , Jolly K , Miles J , Paul K , Doherty PJ , Singh S , Davies R , Noonan M , Dalal H , Taylor RS. Caregiver outcomes of the REACH-HF multicentre randomized controlled trial of home-based rehabilitation for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 611 – 620 .

Olsson K , Näslund U , Nilsson J , Hörnsten Å. Hope and despair: patients’ experiences of being ineligible for transcatheter aortic valve implantation . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 593 – 600 .

Heery S , Gibson I , Dunne D , Flaherty G. The role of public health nurses in risk factor modification within a high-risk cardiovascular disease population in Ireland – a qualitative analysis . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 584 – 592 .

Brännström M , Fischer Grönlund C , Zingmark K , Söderberg A. Meeting in a ‘free-zone’: clinical ethical support in integrated heart-failure and palliative care . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 577 – 583 .

Haydon G , van der Riet P , Inder K. Long-term survivors of cardiac arrest: a narrative inquiry . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 458 – 464 .

Freysdóttir GR , Björnsdóttir K , Svavarsdóttir MH. Nurses’ Use of Monitors in Patient Surveillance: An Ethnographic Study on a Coronary Care Unit . London, England : SAGE Publications ; 2019 . p 272 – 279 .

Google Preview

Pokorney SD , Bloom D , Granger CB , Thomas KL , Al-Khatib SM , Roettig ML , Anderson J , Heflin MT , Granger BB. Exploring patient–provider decision-making for use of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: results of the INFORM-AF study . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 280 – 288 .

Instenes I , Fridlund B , Amofah HA , Ranhoff AH , Eide LS , Norekvål TM. ‘ I hope you get normal again’: an explorative study on how delirious octogenarian patients experience their interactions with healthcare professionals and relatives after aortic valve therapy . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 224 – 233 .

Palmar-Santos AM , Pedraz-Marcos A , Zarco-Colón J , Ramasco-Gutiérrez M , García-Perea E , Pulido-Fuentes M. The life and death construct in heart transplant patients . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019 ; 18 : 48 – 56 .

De Chesnay M , Banner D. Nursing Research Using Grounded Theory: Qualitative Designs and Methods . New York, NY : Springer Publishing Company ; 2015 .

Corbin J , Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory . 3rd ed. California : SAGE ; 2007 .

Glaser BG , Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . New York : Aldine ; 1967 .

Sbaraini A , Carter SM , Evans RW , Blinkhorn A. How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices . BMC Med Res Methodol 2011 ; 11 : 128 – 128 .

Charmaz K. ‘ Discovering’ chronic illness: using grounded theory . Soc Sci Med 1990 ; 30 : 1161 – 1172 .

Thornberg R , Dunne C. Literature review in grounded theory. In Bryant A , Charmaz K , eds. The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory . London : SAGE Publications ; 2019 .

Glaser BG. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions . California : Sociology Press ; 1998 .

Bergman E , Berterö C. ‘ Grasp Life Again’. A qualitative study of the motive power in myocardial infarction patients . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2003 ; 2 : 303 – 310 .

Strauss A , Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques . 2nd ed. California : Sage ; 1998 .

Salminen-Tuomaala M , Åstedt-Kurki P , Rekiaro M , Paavilainen E. Coping—seeking lost control . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012 ; 11 : 289 – 296 .

Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory . 2nd ed. Los Angeles : SAGE ; 2014 .

Odell A , Grip L , Hallberg LRM. Restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): experiences from the patients' perspective . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006 ; 5 : 150 – 157 .

Probyn J , Greenhalgh J , Holt J , Conway D , Astin F. Percutaneous coronary intervention patients’ and cardiologists’ experiences of the informed consent process in Northern England: a qualitative study . BMJ Open 2017 ; 7 : e015127 .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2021 | 36 |

| April 2021 | 87 |

| May 2021 | 275 |

| June 2021 | 217 |

| July 2021 | 177 |

| August 2021 | 175 |

| September 2021 | 167 |

| October 2021 | 188 |

| November 2021 | 196 |

| December 2021 | 137 |

| January 2022 | 190 |

| February 2022 | 259 |

| March 2022 | 345 |

| April 2022 | 431 |

| May 2022 | 420 |

| June 2022 | 260 |

| July 2022 | 304 |

| August 2022 | 360 |

| September 2022 | 385 |

| October 2022 | 444 |

| November 2022 | 527 |

| December 2022 | 517 |

| January 2023 | 514 |

| February 2023 | 656 |

| March 2023 | 777 |

| April 2023 | 684 |

| May 2023 | 663 |

| June 2023 | 493 |

| July 2023 | 505 |

| August 2023 | 503 |

| September 2023 | 698 |

| October 2023 | 950 |

| November 2023 | 832 |

| December 2023 | 709 |

| January 2024 | 813 |

| February 2024 | 703 |

| March 2024 | 1,038 |

| April 2024 | 1,139 |

| May 2024 | 964 |

| June 2024 | 696 |

| July 2024 | 379 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Literature Grounded Theory (LGT)

- First Online: 31 August 2021

Cite this chapter

- Ana Paula Cardoso Ermel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3874-9792 5 ,

- D. P. Lacerda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8011-3376 6 ,

- Maria Isabel W. M. Morandi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1337-1487 7 &

- Leandro Gauss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5708-5912 8

1096 Accesses

1 Citations

- The original version of this chapter was revised: Table 6.28 and Figures 6.2 and 6.5 are updated. The correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75722-9_10

This chapter introduces the Literature Grounded Theory (LGT), a research method for reviewing, analyzing, and synthesizing literature. The conceptual framework and organization structure of LGT are presented first. Then, by breaking down the structure into steps, the techniques and tools for its implementation are described. Finally, the major guidelines for conducting research with LGT are given.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Change history

06 february 2022.

In addition to the changes described above, we note that

Abbas, A., Zhang, L., Khan, S.U.: A literature review on the state-of-the-art in patent analysis. World Patent Inf. 1–11 (2014)

Google Scholar

Adler, M.J., van Doren, C.: How to Read a Book. A Touchstone Book Published by Simon & Schuster, New York (1972)

Aria, M., Cuccurullo, C.: bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Inf. 11 (4), 959–975 (2017). 1751-1577

Bacharach, S.B.: Organizational theories: some criteria for evaluation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14 (4), 496–515. 1989.03637425

Bardin, L.: L’analyse de contenu [Content Analysis], 223 p. Presses Universitaires de France Le Psychologue, Paris (1993)

Barnett-Page, E., Thomas, J.: Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 9 (1), 1–11 (2009). 1471-2288

Bensman, S.J.: Garfield and the impact factor. Ann. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 41 (1), 93–155 (2007). 1573872768

Bergstrom, C., West, J.: Eigenfactor ® (2017)

Bhattacherjee, A.: Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices, 3rd ed [S.l.]. Textbooks Collection (2012). 9781475146127

Booth, A. et al.: Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 99 , 41–52 (2018)

Borenstein, M.: Impact of Tamiflu on flu symptoms [S.l: s.n.] (2021). Disponível em: www.Meta-Analysis.com . Acesso em: 3 fev. 2021

Borenstein, M., et al.: Introduction to Meta-Analysis, 421 p. Wiley, Padstow (2009). 978-0-470-05724-7

Brunton, G., Stansfield, C., Thomas, J.: Finding relevant studies. In: An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, pp. 107–134. Sage Publications Ltd., London (2012)

CGCOM: Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial (2016)

Chaabna, K., et al.: Gray literature in systematic reviews on population health in the Middle East and North Africa: protocol of an overview of systematic reviews and evidence mapping. Syst. Rev. 7 (94), 1–6 (2018)

Cleff, T.: Applied Statistics and Multivariate Data Analysis for Business and Economics [S.l.], 487 pp. Springer (2019). 9783030177669.

Cobo, M.J., et al.: Science mapping software tools: review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 62 (7), 1382–1402 (2011)

Colicchia, C., Strozzi, F.: Supply chain risk management: a new methodology for a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manage. 17 (4), 403–418 (2012). 1359-8546

Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Valentine, J.C.: Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 2nd edn., 610 pp. Russel Sage Foundation, New York (2009). 9780871541635

Counsell, C.: Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann. Int. Med. 127 (5), 380–387 (1997)

Cox, J.F., Schleier, J.G.: Theory of Constraints Handbook, 1175 pp. McGraw-Hill, New York (2010). 9780071665551

Deb, D., Dey, R., Balas, V.E.: Bibliometrics and research quality. In: Engineering Research Methodology. Intelligent Systems Reference Library, vol. 153. 1st edn., pp. 95–105. Springer Nature, Singapore (2019). 978-981-13-2947-0

Denyer, D., Tranfield, D., Van Aken, J.E.: Developing design propositions through research synthesis. Organizat. Stud. 29 (3), 393–413 (2008). 0170-8406

Dresch, A., Lacerda, D.P., Antunes, Jr., J.A.V.: Design Science Research: A Method for Scientific and Technology Advancement, 1st edn, 161 pp. Springer (2015). 978-3-319-07373-6

Dybå, T., Dingsøyr, T.: Empirical studies of agile software development: a systematic review. Inf. Soft. Technol. 50 (9–10), 833–859 (2008)

Fleiss, J.L.: Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 76 (5), 378–382 (1971)

Garousi, V., Felderer, M., Mäntylä, M.V.: Guidelines for including grey literature and conducting multivocal literature reviews in software engineering. Inf. Soft. Technol. 1–22 (2018). 9781450336918

Gauss, L., Lacerda, D.P., Cauchick Miguel, P.A.: Module-based product family design: systematic literature review and meta-synthesis. J. Intell. Manufact. 32 (1), 265–312 (2021)

Gkoulalas-Divanis, A., Verykios, C.S.: Association Rule Hiding for Data Mining [S.l.], 150 pp. Springer (2010). 978-1-4419-6569-1

Gough, D., Oliver, S., Thomas, J.: An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 1st edn., 288 pp. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles (2012). 9781849201803

Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., Adams, A.: Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J. Chiripratic Med. 5 (3), 101–117 (2006). 0024-3892

Grimshaw, J.M., et al.: Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol. Assess. 8 (6), 349 (2004)

Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M., et al.: Some bibliometric procedures for analyzing and evaluating research fields. Appl. Intell. 48 (5), 1275–1287 (2017)

Haddow, G.: Bibliometric research. In: Research Methods: Information, Systems, and Contexts, 2nd edn., pp. 241–266. Chandos Publishing, Cambridge (2018). 978-0-08-102220-7

Hammerstrøm, K., et al.: Searching for studies: information retrieval methods group policy brief, November (2009)

Harden, A., Gough, D.: Quality and relevance appraisal. In: An introduction to systematic reviews, 1st edn., pp. 153–178. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles (2012)

Hart, C.: Doing a Literature Review: Realising the Social Science Research Imagination, 1st edn., 230 pp. SAGE Publications, London (1998)

Higgins, J., Green, S.: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2011)

Higgins, J., Li, T., Deeks, J.J.: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 [S.l: s.n.] (2020a). Disponível em: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10

Higgins, J., Li, T., Deeks, J.J.: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.1 [S.l.]. Cochrane (2020b). Disponível em: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Hood, W.W., Wilson, C.S.: The literature of bibliometrics, scientometrics, and informetrics. Scientometrics 52 (2), 291–314 (2001)

Hsieh, H.F., Shannon, S.E.: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitat. Health Res. 15 (9), 1277–1288 (2005). 1049-7323

Kitchenham, B., Charters, S.: Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Engineering 45 (4ve), 1051 (2007). 1595933751

Krippendorff, K.: Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th edn., 356 pp. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks (2019)

Lacerda, D.P., Rodrigues, L.H., Da Silva, A.C.: Evaluating the synergy of business process engineering and theory of constraints thinking process. Production 21 (2), 284–300 (2011)

Landis, J.R., Koch, G.G.: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33 (1), 159 (1977)

Littell, J.H., Corcoran, J., Pillai, V.: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [S.l: s.n.], 1–211 pp. (2008). 978-0-19-532654-3

Macedo, M.F.G., Muller, A.C.A., Moreira, A.C.: Patenteamento em biotecnologia: um guia prático para os elaboradores de pedidos de patente [S.l.], 200 pp. Editora Embrapa (2001)

Mering, M.: Bibliometrics: Understanding author, article and journal-level metrics. J. Ser. Rev. 43 (1), 41–45 (2017)

Moher, D., et al.: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6 (7) (2009). 0031-9023

Monforte-Royo, C., et al.: What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS ONE 7 (5) (2012). 1932-6203

Morandi, M.I.W.M., Camargo, L.F.R.: Systematic Literature Review. Design In: Science Research [S.l.], p. 161. Springer (2015)

Noblit, G.W., Hare, R.D.: Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies, 1st edn. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park (1988). 9780803930230

OECD: OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms. OECD Publishing, Paris (2008)

Oliveira, O.J. De., et al.: Bibliometric method for mapping the state-of-the-art and identifying research gaps and trends in literature: an essential instrument to support the development of scientific projects. IntechOpen 20 (2019)

Osareh, F.: Bibliometrics, citation analysis and co-citation analysis: a review of literature I. Libri 46 (1), 149–158 (1996)

Pate, D.J., Patterson, M.D., German, B.J.: Optimizing families of reconfigurable aircraft for multiple missions. J. Aircraft title (Snowball Cit. 2nd iteration) 49 (6), 1988–2000 (2012)

Petticrew, M., Roberts, H.: Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide, 1st edn., 336 pp. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA (2006). 1473314060098

Popper, K.: Objective knowledge, 1st edn., 394 pp. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1972)

Quivy, R.: Manuel de Recherche en Sciences Sociales [Manual of Scientific Research in Social Science]. Dunod, Paris (1995). Disponível em: https://tecnologiamidiaeinteracao.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/quivy-manual-investigacao-novo.pdf . 9789726622758

Renz, S.M., Carrington, J.M., Badger, T.A.: Two strategies for qualitative content analysis: an intramethod approach to triangulation. Qualitat. Health Res. 28 (5), 1–8 (2018)

Saini, M., Shlonsky, A.: Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research, 1st edn., 223 pp. Oxford University Press, New York (2012). 9780195387216

Sandelowski, M. et al.: Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. J. Mixed Methods Res. 6 (4), 317–331 (2011)

Scopus: Scopus database (2020)

Smith, V., et al.: Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11 (15), 1–6 (2011)

Snyder, H.: Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104 (March), 333–339 (2019). Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Strauss, A., Corbin, J.: Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, 2nd edn., 272 pp. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park (1990). 978-1412906449

Tan, P.-N., et al.: Introduction to Data Mining, 2nd edn., 864 pp. [S.l.]. Pearson (2019)

Thelwall, M.: Bibliometrics to webometrics. J. Inf. Sci. 34 (4), 605–621 (2008)

Thomas, J., Harden, A., Newman, M.: Synthesis: combining results systematically and appropriately. In: An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 1st edn., p. 288. Sage Publications, Los Angeles (2012)

Thomé, A.M.T., Scavarda, L.F., Scavarda, A.J.: Conducting systematic literature review in operations management. Product. Plann. Control 27 (5), 408–420 (2016)

Universidade de São Paulo: Portal da escrita científica (2019)

Veit, D.R., et al.: Towards mode 2 knowledge production. Bus. Process Manage. J. 23 , 293–328 (2017)

Walsh, D., Downe, S.: Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 50 (2), 204–211 (2005). 1365-2648

Webster, J., Watson, R.T.: Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quart. 26 (2), 133–151 (2002). 0959-5309

Whiting, P., et al.: ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 69 , 225–234 (2016)

Whittemore, R., Knafl, K.: The integrative review: updated methodology. Methodol. Issues Nurs. Res. 52 (5), 546–553 (2005)

Wohlin, C.: Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. ACM Int. Conf. Proc. Ser. (2014). 9781450324762

Yearworth, M., White, L.: The uses of qualitative data in multimethodology: developing causal loop diagrams during the coding process. Eur. J. Operat. Res. 231 (1), 151–161 (2013). Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2013.05.002

Zapf, A. et al.: Measuring inter-rater reliability for nominal data—which coefficients and confidence intervals are appropriate? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 16 (1), 1–10 (2016).

Zhang, C., Zhang, S.: Association Rule Mining: Models and Algorithms [S.l.], 238 pp. Springer (2002). 3-540-43533-6

Zupic, I., Čater, T.: Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizat. Res. Methods 18 (3), 429–472 (2015)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Production and Systems Engineering, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Ana Paula Cardoso Ermel

D. P. Lacerda

Maria Isabel W. M. Morandi

Leandro Gauss

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ana Paula Cardoso Ermel .

6.1 Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PPTX 12866 kb)

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cardoso Ermel, A.P., Lacerda, D.P., Morandi, M.I.W.M., Gauss, L. (2021). Literature Grounded Theory (LGT). In: Literature Reviews. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75722-9_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75722-9_6

Published : 31 August 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-75721-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-75722-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

| | | |

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

- CPD Quizzes

Evidence and practice

Approaches to reviewing the literature in grounded theory: a framework, kris deering senior lecturer in mental health nursing, university of west england, bristol, england, jo williams senior lecturer in mental health nursing, university of west england, bristol, england.

• To build an understanding of research methods associated with grounded theory

• To develop critical awareness of how different approaches in grounded theory might tackle literature reviews

• To learn how to review the literature, depending on the stage of your grounded theory study

Background There is considerable debate about how to review the literature in grounded theory research. Notably, grounded theory typically discourages reviewing the literature before data are collected and analysed, so that researchers do not form preconceptions about the theory. However, it is likely researchers will need to review the literature to show they intend to address a gap in knowledge with their research. This might confuse novice researchers, especially given that different approaches to grounded theory can have contrasting positions concerning how and when literature should be reviewed.

Aim To provide an overview of grounded theory and how different approaches might tackle literature reviews.

Discussion A framework is presented to illustrate some of the commonalities between grounded theory approaches, to guide novice researchers in reviewing the literature. The framework acknowledges some of the tensions concerning researchers’ objectivity and sketches three phases for researchers to consider when reviewing the literature.

Conclusion Reviewing the literature has different meanings and implications when using grounded theory compared with other research methodologies.

Implications for practice Novice researchers must be attuned to the different ways of reviewing the literature when using grounded theory.

Nurse Researcher . doi: 10.7748/nr.2020.e1752

This article has been subject to external double-blind peer review and has been checked for plagiarism using automated software

None declared

Deering K, Williams J (2020) Approaches to reviewing the literature in grounded theory: a framework. Nurse Researcher. doi: 10.7748/nr.2020.e1752

Published online: 09 July 2020

grounded theory - literature review - methodology - qualitative research - research - research methods

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

12 June 2024 / Vol 32 issue 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Approaches to reviewing the literature in grounded theory: a framework

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

- Directories

Grounded theory literature reviews

Another type of literature review is one done for a grounded theory research project. According to one approach, in grounded theory projects, the researcher tends to conduct empirical research before writing a literature review. However, this approach can be problematic if you are a postgraduate research student who is doing deadline-dependent research into a topic that is relatively new or unfamiliar to you. Most academics who do grounded theory research already have a well-developed understanding of the field and theory, which is why they may be more comfortable with leaving a literature review late into the process.

For research students doing grounded theory projects, many argue that it is both practical and important to research the theory early on in the project, to make sure that your project is not duplicating extant work, or go on an irrelevant tangent (Dunne, 2011, p. 116; McGhee, Marland & Atkinson, 2007, p. 340). Also, researching into academic literature takes a long time, so doing it from the start of your project will save you stress later on. So, for a grounded theory project it's useful to start writing your literature review early on.

When writing a grounded theory literature review, it's important to take note of how the literature influences your ideas, and to keep track of your original ideas. To maintain your grounded theory perspective, McGhee, Marland and Atkinson (2007, p. 340) argue that "Reflexivity is needed to prevent prior knowledge distorting the researcher's perceptions of the data." Unlike the traditional approach, where the literature review leads on to the research question, in a grounded theory approach the empirical research is used to reflect on the academic literature's values and limitations.

In this sense, then, the placement of the literature review may be different between traditional and grounded theory projects. Some grounded theory projects don't have a dedicated literature review chapter and instead reflect on the literature throughout the chapters. Others incorporate and reflect on literature throughout the chapters as well as in a substantial section or chapter towards the end of the document. Many follow more of a traditional approach with a literature review early on and reflection on the literature throughout the writing.

Whichever option you choose, discuss it early on with your supervisor. Although there are a variety of ways to structure a grounded theory project, it is frequently recommended that you place a literature review early on in the thesis, possibly in the introduction or first chapter. Having a literature review upfront helps your readers to understand how your research fits into the field. It also helps your readers to identify how your research questions relate to the academic literature.

References and resources about grounded theory research

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (Eds.). (2010). The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

- Dunne, C. (2011). The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 14 (2), 111-124. doi:10.1080/13645579.2010.494930