Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

24 The Importance of Research in Public Relations

Research is a crucial component of the public relations process. There are several key reasons why research is so important. First, research allows us to develop a PR strategy . For example, in our cookie example, research allows us to develop a strategy for one of our key publics with nostalgia as a main focus. This information will allow us to design specific campaigns with particular targets and goals, to ensure we aren’t wasting time, money, and energy. This helps public relations operate as a strategic function of the organization, contributing to overall organizational goals and objectives .

Another reason why research is so important in public relations is that it can be used to measure the effectiveness of our public relations efforts. For example, we can measure how often our key public is purchasing Scrumpties cookies before our campaign, during our campaign, and after out campaign. This way, we can understand if our campaign has an impact purchasing habits. Was the campaign worthwhile? Was it effective? Research helps us answer these questions and justify the value of public relations within organizations by directing funds to effective strategies.

If we do research before we begin communicating, we can ensure we are capturing the views of our publics . We can identify key publics, develop targeted communications based on what is important to our publics, and build relationships with those publics who may be interested in our messaging. This contributes to two-way communication , instead of outdated methods of disseminating information one way to our publics (Grunig, 1992). Research is what allows us to understand our publics, their needs, and their values, and ensures that we are as effective and strategic as possible in the public relations process.

If we didn’t do research, PR would not be a key strategic function of organizations. Instead, we would be making decisions based on hunches and instinct, and generating publicity without any clear sense of who our publics are and what matters to them. As a central, strategic function of organizations, public relations relies on research to identify issues, problem solve, prevent and manage crises, develop and maintain relationships with publics, and deploy useful strategies and campaigns to support organizational goals and objectives. Being able to understand, conduct, and report on research also allows public relations professionals to demonstrate the value and worth of PR activities and helps ensure PR is part of the organization’s dominant coalition. In short, research matters!

This chapter is a very brief introduction to public relations research. Research is complicated, and you will learn a lot more about research design, methods, and best practices throughout your degree. For now, it is important that you recognize why research is so important in public relations, and that you are aware of its critical function within the public relations process ( RACE ). You should know the difference between formal and informal research, understand what quantitative and qualitative research means, and be aware of two key research techniques: surveys and focus groups.

Grunig, J. E. (Ed.). (1992). Excellence in public relations and communication management . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

A plan of action or policy designed to achieve a major or overall aim

A goal is something that a person or group is trying to achieve.

An objective is a goal expressed in specific terms.

Any group(s) of people held together by a common interest. They differ from audiences in that they often self-organize and do not have to attune to messages; publics differ from stakeholders in that they do not necessarily have a financial stake tying them to specific goals or consequences of the organization. Targeted audiences, on the other hand, are publics who receive a specifically targeted message that is tailored to their interests.

A process by which two people or groups are able to communicate with each other in a reciprocal way

A process when a person or group sends a message and receives no feedback of any kind from the receiver

RACE formula includes Research, Action planning & Analysis, Communication, Evaluation

Foundations of Public Relations: Canadian Edition Copyright © by Department of Communication Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- About Brant

- Public Relations

- Social Media

- PR Articles

Just how important is research in public relations?

- Just how important is research…

Photo credit: Janeneke Staaks via Flickr cc

By Megan R. Auren

Where research fits into public relations

Public relations activities are often explained with acronyms like ROPES and RACE.

- ROPES: Research, objectives, programming, evaluation, stewardship.

- RACE: Research, action, communication, evaluation.

It is important to note research is the foundation of all public relations activities and should operate on a continuous cycle. However, research is often overlooked and left behind during plan progression. Failing to revisit research throughout a plan is a mistake and can lead to expensive repercussions.

A crash course in research

- Theoretical research and applied research: Public relations professionals most often use applied research in their field. Applied research uses framework created by theoretical research to understand situations and solve problems.

- Quantitative and qualitative data: Within research are terms such as quantitative data and qualitative data. Quantitative data reports quantities whereas qualitative data reports subjective responses. Both quantitative data and qualitative data are equally important to public relations research.

The importance of research in public relations

- Research establishes a foundation for a public relations plan. Research allows public relations professionals to learn and understand an organization, its goals and its target market. In this baseline phase of research public relations professionals are able to judge current organization efforts and use industry knowledge to give advice and provide direction for the plan.

- Research allows for preparation of change and industry trends. In addition to foundation research, continuous research allows for preparation of change and industry trends. Continuous research efforts involve monitoring and tracking a plan and are referred to as checkpoint research or benchmark research.

- Research grants proper evaluation. The final activity in a public relations plan is preparing an evaluation of the plan. Proper measurement and assessment can only be administered when compared to baseline research. Therefore, if a baseline of research is not collected at the beginning of a plan then the effectiveness of the final evaluation diminishes.

Don’t leave research behind

In order to create an effective public relations plan research must be at the forefront of decision making and must be included throughout the plan. Therefore, the best public relations practices involve completing a foundation of baseline research and then accommodating for checkpoint research throughout the plan. Doing so will ensure your public relations plan stays on track, is able to adjust to change, and remains up to date with industry trends.

More public relations insights

Learn more in the book Promoting Your Business: How to Harness the Power of Media Relations and Influencer Marketing .

- The role of public relations in the marketing mix

- Promoting Your Business: new public relations resource for entrepreneurs

- Public relations case study: Johnson & Johnson Tylenol crisis

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE OUR NEWSLETTER

Sign up to get promotions, news and more...

May 21, 2019

The importance of research in a public relations campaign.

- #OlivePRMoments

- #TheOliveWay

- #IlluminatingGreatness

- #NowTrending

By Jaclyn Walian

Contrary to what some may think, research plays an integral role in any public relations and social media campaign. It should be the foundation to the plan and incorporated into every step after. Research is what lets us know and understand target audiences , what resonates with those target audiences and the impact of the campaign. Research allows us to better guide the campaign so you can actually see results and a return on your investment. It is something that should not be overlooked.

We’re not saying that you have to go out and spend thousands of dollars on research. While that is always helpful, there are other ways to gather important information without breaking the bank:

- Customer/client survey – use the contact information you already have to conduct a survey

- Informal focus group – gather some friends or reach out to your network to conduct a focus group

- Hit the streets – go to a high traffic area and talk to people

- Social media and website analytics – you can gather a lot of information from these sources

At Olive, we like to look at numbers and facts to help guide our campaigns. A great example of this is when we worked with VIM & VIGR , a fashionable compression sock company. Being that they were new to the market, we didn’t have much research so we kicked off with what we thought would be the best route – going after the fitness and fashion markets as well as the general public. While these audiences loved the product, we soon realized that the audiences with the most conversions were those professions that were on their feet all day – nurses, teachers, etc. – and those that needed compression socks for medical reasons – DVT and pregnancy. Once we had numbers to look at, we quickly pivoted our plans and changed our strategy to target the audiences most likely to purchase the products.

We also focus on the result of the result, which comes from research. While it’s great if we secure a media hit on a site that has 1 million unique monthly visitors, that does not mean that 1 million people will see the article or convert and purchase a product. We work with our clients to determine what the actual impact was – did it result in sales, increased traffic, etc.? If yes, then we are on the right track. If no, we hit the drawing board to figure out a new strategy with the new information we now have.

Interested in making sure research plays into your campaign? Contact us at [email protected]

How Is Research Important to Strategic Public Relations Plans?

- Small Business

- Business Planning & Strategy

- Strategic Planning

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Pinterest" aria-label="Share on Pinterest">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Reddit" aria-label="Share on Reddit">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Flipboard" aria-label="Share on Flipboard">

Effective Communication & Leadership

The importance of planning in an organization, goals of a team leader.

- How to Write a Good Project Proposal for Donor Funding

- Corporate Development & Planning

Formulating strategic public relations plans for your small business involves conducting some research, whether it is through customer surveys or other methods of data gathering. Public relations workers may give their opinions and recommendations on conducting research, but top management needs to understand the importance of research in PR campaigns and make informed decisions on how to proceed.

The Importance of Research in Public Relations

Research, when conducted properly, eliminates bias and gives the leaders of a company a realistic picture of how various members of the public perceive the organization. As North Kentucky University mentions, if the leaders and public relations workers in a company were to rely solely on their own biased opinions of how the public views the organization, they would risk not really knowing if the organization’s public image needs to be improved. The leaders and public relations workers also risk making decisions that would not positively affect the public’s perception of the organization.

Organizational Strengths and Weaknesses

Research for a public relations plan should involve a non-biased assessment of the organization itself. This research analyzes not only the overall mission of the organization but also how far the organization has gone toward achieving its mission. The research also gives a list and assessment of all resources available to the organization that it may use in the implementation of a public relations plan. Leadership in the organization also receives information about any liabilities or possible internal threats that could jeopardize the public relations plan, allowing the leadership to devise a plan for how to proactively manage these risks.

Research and Public Relations Messaging

The research conducted by the organization provides valuable information about how the organization should craft its public relations messaging. The research provides feedback about what matters most to the public, which the organization addresses or incorporates in public relations messaging. Thorough research on groups the organization interacts with also supplies a list of media forms the different groups engage in, letting the organization know the most effective methods of delivering its message.

Gaining Feedback From Stakeholders

After a public relations plan has been formulated and then put into practice, additional research provides feedback on the actual public relations plan. This research allows the organization to determine if any of the objectives formulated for the public relations plan has been achieved and to what degree.

As Nikki Little at Identity points out, organizations should limit the amount of time they spend researching and analyzing to a specific timeline, otherwise you run the risk of inaction due to analysis paralysis. Knowing how effective the public relations plan is at achieving the objectives helps the organization decide whether to continue with the plan, make adjustments to the plan or to scrap the plan and begin formulating a new one.

- Northern Kentucky University; Public Relations Planning; Strategic Planning Steps; Michael Turney

- Identity: A Practical Guide to Public Relations Strategic Planning

Related Articles

What is the difference between operational guidance and operational planning, organizational communication objectives for human services, organizational structure policies, strategic planning at all organization levels, what is a productivity plan, tips on knowing your target audience when communicating within an organization, describe the concept of strategic alignment, how to analyze the key success factors for plan implementation, how to form a 501c, most popular.

- 1 What Is the Difference Between Operational Guidance and Operational Planning?

- 2 Organizational Communication Objectives for Human Services

- 3 Organizational Structure Policies

- 4 Strategic Planning at All Organization Levels

Chapter 8 Public Relations Research: The Key to Strategy

If you previously ascribed to the common misconception that public relations is a simple use of communication to persuade publics, Bowen (2003), pp. 199–214. you might be surprised at the important role that research plays in public relations management. Bowen (2009a), pp. 402–410. We can argue that as much as three quarters of the public relations process is based on research—research, action planning, and evaluation—which are three of the four steps in the strategic management process in the RACE acronym (which stands for research, action planning, communication, and evaluation).

8.1 Importance of Research in Public Relations Management

Public relations professionals often find themselves in the position of having to convince management to fund research, or to describe the importance of research as a crucial part of a departmental or project budget. Research is an essential part of public relations management. Here is a closer look at why scholars argued that conducting both formative and evaluative research is vital in modern public relations management:

- Research makes communication two-way by collecting information from publics rather than one-way, which is a simple dissemination of information. Research allows us to engage in dialogue with publics, understanding their beliefs and values, and working to build understanding on their part of the internal workings and policies of the organization. Scholars find that two-way communication is generally more effective than one-way communication, especially in instances in which the organization is heavily regulated by government or confronts a turbulent environment in the form of changing industry trends or of activist groups. See, for example, Grunig (1984), pp. 6–29; Grunig (1992a; 2001); Grunig, Grunig, and Dozier (2002); Grunig and Repper (1992).

- Research makes public relations activities strategic by ensuring that communication is specifically targeted to publics who want, need, or care about the information. Ehling and Dozier (1992). Without conducting research, public relations is based on experience or instinct, neither of which play large roles in strategic management. This type of research prevents us from wasting money on communications that are not reaching intended publics or not doing the job that we had designed them to do.

- Research allows us to show results , to measure impact, and to refocus our efforts based on those numbers. Dozier and Ehling (1992). For example, if an initiative is not working with a certain public we can show that ineffectiveness statistically, and the communication can be redesigned or eliminated. Thus, we can direct funds toward more successful elements of the public relations initiative.

Without research, public relations would not be a true management function . It would not be strategic or a part of executive strategic planning, but would regress to the days of simple press agentry, following hunches and instinct to create publicity. As a true management function, public relations uses research to identify issues and engage in problem solving, to prevent and manage crises, to make organizations responsive and responsible to their publics, to create better organizational policy, and to build and maintain long-term relationships with publics. A thorough knowledge of research methods and extensive analyses of data also allow public relations practitioners a seat in the dominant coalition and a way to illustrate the value and worth of their activities. In this manner, research is the strategic foundation of modern public relations management. Stacks and Michaelson (in press).

8.2 Purpose and Forms of Research

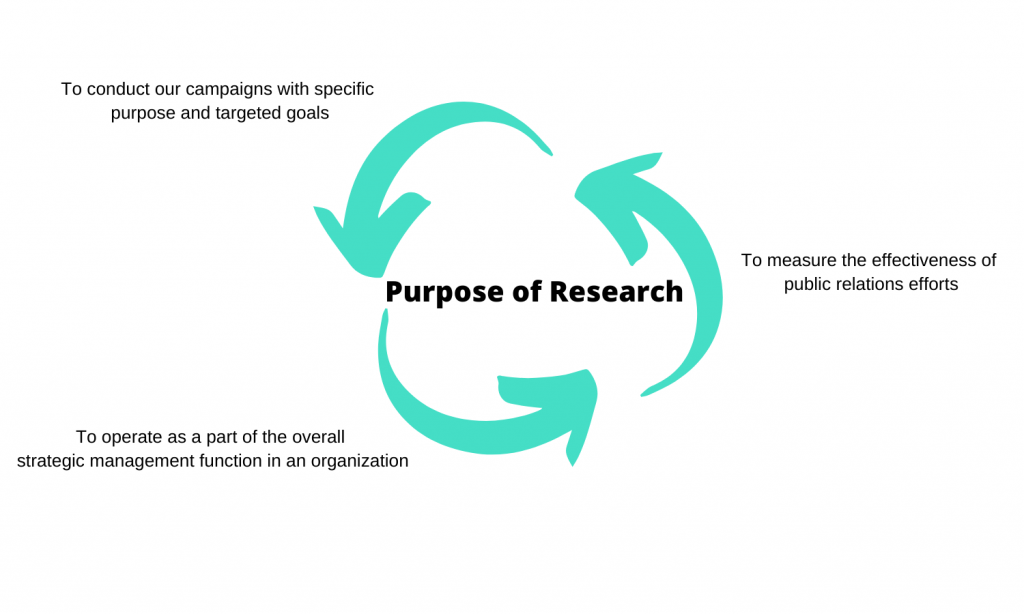

The purpose of research is to allow us to develop strategy in public relations in order to (a) conduct our campaigns with specific purpose and targeted goals, (b) operate as a part of the overall strategic management function in an organization, and (c) measure the effectiveness of public relations efforts. By conducting research before we communicate, we revise our own thinking to include the views of publics. We can segment those publics, tailor communications for unique publics, send different messages to specifically targeted publics, and build relationships by communicating with publics who have an interest in our message. This type of planning research is called formative research Planning research that is conducted so that what the publics know, believe, or value and what they need or desire to know can be understood before communication is begun. because it helps us form our public relations campaign. Stacks (2002). Formative research is conducted so that we can understand what publics know, believe, or value and what they need or desire to know before we began communicating. Thereby, public relations does not waste effort or money communicating with those that have no interest in our message.

Research also allows public relations professionals to show the impact made through their communication efforts after a public relations campaign. This type of research is called evaluation research Research that allows public relations professionals to show the impact made through their communication efforts after a public relations campaign. . Using both forms of research in public relations allows us to communicate strategically and to demonstrate our effectiveness. For example, formative research can be used to determine the percentage of publics who are aware of the organization’s policy on an issue of concern. Through the use of a survey, we might find that 17% of the target public is aware of the policy. Strategically, the organization would like more members of that public to be aware of the organization’s policy, so the public relations department communicates through various channels sending targeted messages.

After a predetermined amount of time, a survey practically identical to the first one is conducted. If public relations efforts were successful, the percentage of members of a public aware of the organization’s policy should increase. That increase is directly attributable to the efforts of the public relations campaign. We could report, “Members of the community public aware of our new toxic waste disposal initiative increased from 17% to 33% in the last 2 months.” Measures such as these are extremely common in public relations management. They may be referred to as benchmarking because they establish a benchmark and then measure the amount of change, similar to a before-and-after comparison. Stacks (2002); Broom and Dozier (1990). The use of statistically generalizable research methods allows such comparisons to be made with a reasonable degree of confidence across various publics, geographic regions, issues, psychographics, and demographic groups.

In this section, we will provide a brief overview of the most common forms of research in public relations management and providing examples of their uses and applications and professional public relations. Building upon that basic understanding of research methods, we then return to the theme of the purpose of research and the importance of research in the public relations function.

Formal Research

Research in public relations can be formal or informal. Formal research Research that typically takes place in order to generate numbers and statistics. Formal research is used to both target communications and measure results. normally takes place in order to generate numbers and statistics that we can use to both target communications and measure results. Formal research also is used to gain a deeper, qualitative understanding of the issue of concern, to ascertain the range of consumer responses, and to elicit in-depth opinion data. Formal research is planned research of a quantitative or qualitative nature, normally asking specific questions about topics of concern for the organization. Formal research is both formative , at the outset of a public relations initiative, and evaluative , to determine the degree of change attributable to public relations activities.

Informal Research

Informal research Research that typically gathers information and opinions through conversations and in an ongoing and open exchange of ideas and concerns. is collected on an ongoing basis by most public relations managers, from sources both inside and outside of their organizations. Informal research usually gathers information and opinions through conversations. It consists of asking questions, talking to members of publics or employees in the organization to find out their concerns, reading e-mails from customers or comment cards, and other informal methods, such as scanning the news and trade press. Informal research comes from the boundary spanning role of the public relations professional, meaning that he or she maintains contacts with publics external to the organization, and with internal publics. The public relations professional spends a great deal of time communicating informally with these contacts, in an open exchange of ideas and concerns. This is one way that public relations can keep abreast of changes in an industry, trends affecting the competitive marketplace, issues of discontent among the publics, the values and activities of activist groups, the innovations of competitors, and so on. Informal research methods are usually nonnumerical and are not generalizable to a larger population, but they yield a great deal of useful information. The data yielded from informal research can be used to examine or revise organizational policy, to craft messages in the phraseology of publics, to respond to trends in an industry, to include the values or priorities of publics in new initiatives, and numerous other derivations.

8.3 Types of Research

Research in public relations management requires the use of specialized terminology. The term primary research The collection of unique data, normally proprietary, that is firsthand and relevant to a specific client or campaign. It is often the most expensive type of data to collect. is used to designate when we collect unique data in normally proprietary information, firsthand and specifically relevant to a certain client or campaign. Stacks (2002). Primary research, because it is unique to your organization and research questions, is often the most expensive type of data to collect. Secondary research The collection of data that is typically part of the public domain but is applicable to a client, organization, or industry. It can be used to round out and support the conclusions drawn from primary research. refers to research that is normally a part of public domain but is applicable to our client, organization, or industry, and can be used to round out and support the conclusions drawn from our primary research. Stacks (2002); Stacks and Michaelson (in press). Secondary research is normally accessed through the Internet or available at libraries or from industry and trade associations. Reference books, encyclopedias, and trade press publications provide a wealth of free or inexpensive secondary research. Managers often use secondary research as an exploratory base from which to decide what type of primary research needs to be conducted.

Quantitative Research

When we speak of research in public relations, we are normally referring to primary research, such as public opinion studies based on surveys and polling. (The following lists quantitative research methods commonly employed in public relations.) Surveys are synonymous with public opinion polls, and are one example of quantitative research. Quantitative research Research that is based on statistical generalization. It allows numerical observations to be made in order for organizations to improve relationships with certain publics and then measure how much those relationships have improved or degraded. is based on statistical generalization . It allows us to make numerical observations such as “85% of Infiniti owners say that they would purchase an Infiniti again.” Statistical observations allow us to know exactly where we need to improve relationships with certain publics, and we can then measure how much those relationships have ultimately improved (or degraded) at the end of a public relations initiative. For example, a strategic report in public relations management for the automobile maker Infiniti might include a statement such as “11% of new car buyers were familiar with the G35 all-wheel-drive option 3 months ago, and after our campaign 28% of new car buyers were familiar with this option, meaning that we created a 17% increase in awareness among the new car buyer public.” Other data gathered might report on purchasing intentions, important features of a new vehicle to that public, brand reputation variables, and so on. Quantitative research allows us to have a before and after snapshot to compare the numbers in each group, therefore allowing us to say how much change was evidenced as a result of public relations’ efforts.

Methods of Quantitative Data Collection

- Internet-based surveys

- Telephone surveys

- Mail surveys

- Content analysis (usually of media coverage)

- Comment cards and feedback forms

- Warranty cards (usually demographic information on buyers)

- Frequent shopper program tracking (purchasing data)

In quantitative research, the entire public you wish to understand or make statements about is called the population In quantitative research, the entire public that is sought to be understood or about which statements are made. . The population might be women over 40, Democrats, Republicans, purchasers of a competitor’s product, or any other group that you would like to study. From that population, you would select a sample In quantitative research, a portion of a population that is sought for study. to actually contact with questions. Probability samples A randomly drawn portion of a population from which the strongest statistical measure of generalizability can be drawn. can be randomly drawn from a list of the population, which gives you the strongest statistical measures of generalizability. A random sample A randomly drawn portion of a population in which the participants have an equal chance of being selected. means that participants are drawn randomly and have an equal chance of being selected. You know some variants in your population exists, but a random sample should account for all opinions in that population. The larger the sample size (number of respondents), the smaller the margin of error and the more confident the researcher can be that the sample is an accurate reflection of the entire population.

There are also other sampling methods, known as nonprobability samples Research sampling that does not allow for generalization but that meets the requirements of the problem or project. , that do not allow for generalization but meet the requirement of the problem or project. A convenience sample A population sample drawn from those who are convenient to study. , for instance, is drawn from those who are convenient to study, such as having visitors to a shopping mall fill out a survey. Another approach is a snowball sample A population sample in which the researcher asks a respondent participating in a survey to recommend another respondent for the survey. in which the researcher asks someone completing a survey to recommend the next potential respondent to complete the survey. A purposive sample Research sampling in which a specific group of people is sought out for research. is when you seek out a certain group of people. These methods allow no generalizability to the larger population, but they are often less expensive than random sample methods and still may generate the type of data that answers your research question.

Quantitative research has the major strength of allowing you to understand who your publics are, where they get their information, how many believe certain viewpoints, and which communications create the strongest resonance with their beliefs. Demographic variables are used to very specifically segment publics. Demographics are generally gender, education, race, profession, geographic location, annual household income, political affiliation, religious affiliation, and size of family or household. Once these data are collected, it is easy to spot trends by cross-tabulating the data with opinion and attitude variables. Such cross-tabulations result in very specific publics who can be targeted with future messages in the channels and the language that they prefer. For example, in conducting public relations research for a health insurance company, cross-tabulating data with survey demographics might yield a public who are White males, are highly educated and professional, live in the southeastern United States, have an annual household income above $125,000, usually vote conservatively and have some religious beliefs, have an average household size of 3.8 people, and strongly agree with the following message: “Health insurance should be an individual choice, not the responsibility of government.” In that example, you would have identified a voting public to whom you could reach out for support of individualized health insurance.

Segmenting publics in this manner is an everyday occurrence in public relations management. Through their segmentation, public relations managers have an idea of who will support their organization, who will oppose the organization, and what communications—messages and values—resonate with each public. After using research to identify these groups, public relations professionals can then build relationships with them in order to conduct informal research, better understand their positions, and help to represent the values and desires of those publics in organizational decision making and policy formation.

Qualitative Research

The second major kind of research method normally used in the public relations industry is qualitative research. Qualitative research Research that allows the researcher to generate in-depth, quality information in order to understand public opinion. This type of research is not generalizable but it often provides quotes that can be used in strategy documents. generates in-depth , “quality ” information that allows us to truly understand public opinion , but it is not statistically generalizable. (The following lists qualitative research methods commonly employed in public relations.) Qualitative research is enormously valuable because it allows us to truly learn the experience, values, and viewpoints of our publics. It also provides ample quotes to use as evidence or illustration in our strategy documents, and sometimes even results in slogans or fodder for use in public relations’ messages.

Qualitative research is particularly adept at answering questions from public relations practitioners that began “How?” or “Why?” Yin (1994). This form of research allows the researcher to ask the participants to explain their rationale for decision making, belief systems, values, thought processes, and so on. It allows researchers to explore complicated topics to understand the meaning behind them and the meanings that participants ascribe to certain concepts. For example, a researcher might ask a participant, “What does the concept of liberty mean to you?” and get a detailed explanation. However, we would expect that explanation to vary among participants, and different concepts might be associated with liberty when asking an American versus a citizen of Iran or China. Such complex understandings are extremely helpful in integrating the values and ideas of publics into organizational strategy, as well as in crafting messages that resonate with those specific publics of different nationalities.

Methods of Qualitative Data Collection

- In-depth interviews

- Focus groups

- Case studies

- Participant observation

- Monitoring toll-free (1-800 #) call transcripts

- Monitoring complaints by e-mail and letter

Public relations managers often use qualitative research to support quantitative findings. Qualitative research can be designed to understand the views of specific publics and to have them elaborate on beliefs or values that stood out in quantitative analyses. For example, if quantitative research showed a strong agreement with the particular statement, that statement could be read to focus group participants and ask them to agree or disagree with this statement and explain their rationale and thought process behind that choice. In this manner, qualitative researchers can understand complex reasoning and dilemmas in much greater detail than only through results yielded by a survey. Miles and Huberman (1994).

Another reason to use qualitative research is that it can provide data that researchers did not know they needed. For instance, a focus group may take an unexpected turn and the discussion may yield statements that the researcher had not thought to include on a survey questionnaire. Sometimes unknown information or unfamiliar perspectives arise through qualitative studies that are ultimately extremely valuable to public relations’ understanding of the issues impacting publics.

Qualitative research also allows for participants to speak for themselves rather than to use the terminology provided by researchers. This benefit can often yield a greater understanding that results in far more effective messages than when public relations practitioners attempt to construct views of publics based on quantitative research alone. Using the representative language of members of a certain public often allows public relations to build a more respectful relationship with that public. For instance, animal rights activists often use the term “companion animal” instead of the term “pet”—that information could be extremely important to organizations such as Purina or to the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Mixed Methods/Triangulation

Clearly, both quantitative and qualitative research have complementary and unique strengths. These two research methodologies should be used in conjunction whenever possible in public relations management so that both publics and issues can be fully understood. Using both of these research methods together is called mixed method research A research method that combines quantitative and qualitative research. This method is considered to yield the most reliable research results. , and scholars generally agree that mixing methods yields the most reliable research results. Tashakkori and Teddlie (1998). It is best to combine as many methods as is feasible to understand important issues. Combining multiple focus groups from various cities with interviews of important leaders and a quantitative survey of publics is an example of mixed method research because it includes both quantitative and qualitative methodology. Using two or more methods of study is sometimes called triangulation In public relations, the use of two or more methods of study in order to ascertain how publics view an issue. , meaning using multiple research methods to triangulate upon the underlying truth of how publics view an issue. See Stacks (2002); Hickson (2003).

8.4 Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we examined the vital role of research in public relations management, both in making the function strategic and in adding to its credibility as a management function. Because research comprises such a large part of the public relations process—three of the four steps in the strategic management process—we discussed the purposes and forms of commonly used research in public relations. The roles of formal and informal research were discussed, as well as the major approaches to research: quantitative (numerically based) and qualitative (in-depth based) as well as the types of types of data collection commonly used in public relations in the mixing of methods.

Taking Digital PR To A New Level

Suggestions, the four-step process in public relations.

The start of the year isn’t just a perfect time to set goals in your personal life. Also, it can be a great opportunity to reconsider your company’s public relations strategy and check if your efforts will bring your desired results all year long.

The best way to boost public relations plans is to follow the four-step RPIE method, which will help you analyze all of the communication activities that are part of your campaign and guarantee they connect to the broader goals of your organization.

The four-step process can help you drive awareness, change attitudes and impact behavior. The four-step process states that to be effective, public relations must be used as a management function. PR managers should be proactive in identifying the issues and scanning the environment.

Whether you’re a beginner who is new to the world of RPIE or an experienced PR communicator who just needs some updates, here, in this article, you’ll find the core things you need to know about this four-step method for your PR success.

Key Elements of the Four-Step Process in Public Relations

#1 research.

Each step is as important as the others, but the first one is crucial. Research should start from gathering information to diagnose the problem. The information you find and understanding you gain in the first step impact other steps in the process and shape the final result.

While the term “public relations” is often associated with big international events like black-tie galas and celebrities’ social media campaigns, those working in the industry know the reality: a significant part of any PR routine is actually gathering data.

So part of this first step in the research is knowing and understanding your target audience. This also means knowing where the audience receives information and news and what media they consume.

Before you start brainstorming about the creative ideas for a successful PR campaign, you have to do the research and carefully consider questions such as:

- WHO are you trying to conquer with the campaign?

- WHAT do you want the audiences you reach to do?

- WHAT are the key messages you want the audiences who are involved in your communications activities to take away?

Many PR experts will tell you that proper research almost guarantees you some surprising findings and new useful insights. You must hold primary research (focus groups, surveys, and interviews—

the most expensive) and secondary research (Internet/social media research, literature reviews, and fact-finding) in order to find real data that will help you find true answers to the questions above.

#2 Planning

In the planning stage, you have to focus on the best ways to find a solution to the communication problem or PR goal. Goals and objectives are created in this phase. Your objectives have to be SMART:

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Realistic

- Timely

These features will help you create and evaluate the implementation.

No matter what is the goal of your public relations plan is—whether it’s raising awareness for a cause or increasing attendance to an event—carefully defining these five elements will provide the roadmap your plan needs to be successful:

Goals are broad, long-term declarations that often attempt to capture a future state of being for a brand.

Example: To become the state leader in your industry

A company’s publics are the key groups of people who have a stake in that organization.

Example: Shareholders, customers, employees

Objectives are shorter-term statements than goals and help to clearly define the attitude shift or behavior change you’d like to reach from one of the given audiences defined above. Objectives should have SMART features—being specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-specific.

Example: To increase downloads of agency’s guide by 10% by the end of the year

Strategies detail how to achieve your objectives.

Example: Spend more money on ads to improve your company’s messaging.

Tactics are the specific public relations activities that will be completed in order to implement a strategy.

Example: Published articles, social media posts, organized events

#3 Implementation

The third phase of the public relations plan is where you actually execute all the actions from your plan. These are the tactics presenting our strategy. What are tactics? Tactics mean the tools you use to execute your plan, like writing a press release, organizing a special event, sending a newsletter, posting on social media, and more. Tactics are the doing part of public relations.

Some of the most important factors to remember during the implementation phase are:

- Timetable: Especially for longer-term campaigns, creating a schedule that sets the specific dates when key processes will be finished and the next one should start. (Just remember, the deadlines have to be realistic.)

- Accountabilities: In addition to defining when specific stages of the plan must be finished , it’s also important to define who is responsible for executing them.

- Budget: Make it a point to clearly call out the money assigned to each part of the campaign. (Update it in real-time as elements came in under- or over-budget.)

#4 Evaluation

Although it can sometimes be disregarded, this final phase of the plan is one of the most important. Evaluation is a focus on results. It helps understand whether the communication actions you performed as part of the campaign actually fulfilled their desired goals. Did you reach the objectives? An evaluation improves public relations because this is how PR managers show value to clients.

The first step in a successful evaluation phase is collecting information that will help you determine the success of your program against the objectives defined in your plan. For example, if your plan covers outcome-based goals (not including awareness increase, changes in opinions, or behavior), you must have some tools and methods to correctly estimate those objectives, whether it’s conducting a survey or looking at fundraising information.

Nevertheless, simply looking at data and then proceeding from that isn’t enough. To fully evaluate the success of a public relations plan, it’s important to analyze individual elements and understand what aspects of the plan were successful—and, just as importantly, which weren’t. Identifying your strengths and weaknesses will go a long way toward helping you choose ways to improve and adjust your plan, messages, and materials going forward.

Most often, the outcome you find during the evaluation stage will become the start for the next plan you complete. Hence the cycle repeats, bringing your company closer to achieving goals next year.

An Example of the Four-Step Process in PR

Now let’s dive deeper into the four-step process in public relations with an example that will better illustrate how to apply RPIE method.

The first step to consider is what communication problem is there to solve or the what goal needs to be achieved.

Sometimes clients or brand managers will self-identify a problem, or maybe you are pitching new business and setting the goals yourselves. Whatever it is, it’s important to define it.

Let’s learn the four-step process implementation with the next task example: to fill the football stadium of a university team.

Before we start to think about how to increase attendance, it’s important to find a reason why the games at the stadium are not popular among the students. Remember, research is the first step in the public relations process.

So first, begin with research. For this, it will be helpful to conduct an environmental scan, monitoring the internal and external environments.

This includes gathering information about segments of the audience, the reactions to the team and university in general, and people’s opinions about issues important to the organization. It’s also useful to carry out a SWOT analysis identifying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the organization.

These methods provide context for the communication problem you are working to solve. The better you will know the organization, the situation, maybe even the history, the better you can strategize on how to solve an issue or reach your PR goal. During the research step, you should conduct both primary and secondary research and use different methods, such as interviews of focus groups, surveys, etc.

So the research revealed that this particular university and residents of this city had a huge interest in basketball. So the reason students didn’t attend football games was because of a low fandom for football. This university football team became a victim of the university’s reputation—

students who attended the university were interested in basketball, and therefore attending football matches was not their goal and interest. So the first reason was found.

Providing a proof motion may fill the stadium once or twice, but remember, public relations is about the long game. Thus, it was important to drill down past the superficiality of the stadium attendance and find more reasons why were students are not attending. Why were locals not attending football games as well?

Answering those questions will help define brand value and brand equity. So here’s further situation analysis. As it was mentioned earlier, the culture of the university was basketball. There wasn’t a lot of interest in football. The university’s football team also had bad results, perhaps a consequence of the empty stadium. But does a full stadium, a winning team make? Absolutely not.

Students needed to become fans or brand ambassadors. What happens when you like a team? You wear their clothes, you take part in their events, you cheer for your favorite players, you engage on social media, you care about the results, and you still keep on attending the games even when your favorite team is loses in the championships for years.

So one part of the research helped determine the goal of public relations for this sporting organization— to create brand ambassadors or fans.

To find more information, conduct a SWOT analysis and discover the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the organization concerning the communication problem. These methods include survey, content analysis, digital analytics and others.

Beginning with the strength: the university administration was ready to help by all necessary means. In addition, the space around the stadium was perfect for entertaining fans. Moreover, the city where the university was located had large enterprises, and that provided an opportunity for sponsorships and partnerships. This means the football team had new stakeholders to build relationships with.

The weaknesses included low game-day attendance, little expression, little school spirit, or minimal fandom. Another weakness was the university’s use of social media. They had too many pages that spread out attention.

After this, let’s move from research to the second step — planning. This is where we plan the messaging strategy. Defining objectives help to keep us on track and decide what it is that we want the communication to do or achieve. This is where strategy comes into public relations.

So we wanted to find a way to increase the brand value of the football team. Find a way to create emotional contact with students and provide benefits for engaging with the brand. The objectives here are focused on interest, prestige, engagement, raising awareness and education. Point out the objectives are not about filling in the stadium. PR is not about short-term actions or stunts. Instead, we want to achieve long-term goals for the mission of the company. It’s better to eliminate the root cause of the problem and try to make some useful changes there. We have to push forward the mission of the brand. That’s a long process. If we are successful with these objectives, the results should have a bigger effect than an increase in the attendance in the stadium.

Then, let’s go over the third phase — implementation. This phase is often thought to be more interesting and creative side of public relations because this is the execution of the strategy phase or where we put the tactics into action.

In this case study, these are some of the tactics that were appropriate to implement. First, it is important to create hype around football games. It was a good idea to organize pregame concerts and invite students to participate in pregame contests and events engaging with the brand.

Then the university website was updated with photos from these events and the social media accounts also featured them. And it gave an opportunity to gather the fans, listen to the reviews, and involve the target audience via a new source. Many people also had difficulty attending games due to all of the unknowns involved. So building an app to centralize information about game day was important, as it provided benefits for users attending football games.

Also, this university initiated the traditions like singing fight songs and using crowd engagement tactics. It’s great to provide fans with a memorable experience so they talk about it and become brand ambassadors.

Finally, it’s important to realize the fourth phase of the process — evaluation. It is about showing value. What did the PR efforts achieve? Did they meet the objectives? Is the issue solved? This is what the evaluation stage is about in public relations. In this particular example, public relations absolutely helped fill the stadium with fans. This university’s football program has continued to improve and now it’s hard to get a ticket to their football games. The brand value has increased and the stakeholders are proud to be associated with the team. This is ultimately the goal of public relations.

I hope this example showed how much the four-step process can assist in successfully executed PR work. When PR is used as a management function, meaning strategically, not tactically, that’s when it is the most productive.

Content Marketing Platform

- 100,000+ media publications;

- get backlinks to your product;

- scale work with content distribution.

Following these time-tested steps in executing your PR campaign is sure to help you succeed —whether that success means winning an award or helping your brand achieve its business goals.

Latest from Featured Posts

Teamsale CRM Uses PRNEWS.IO to Increase Media Visibility in New Regions

About Teamsale CRM Teamsale CRM is the definitive CRM solution that seamlessly integrates voice, messaging, and…

Smaily Increased Brand Awareness in New Markets with PRNEWS.IO

Smaily, founded in 2005 by Erkki Markus, is a renowned email marketing and automation platform, managing…

Brokeree Solutions Tripled Media Mentions and Achieved a 5-Point SERP Jump with PRNEWS.IO

Today, we want to share a case study on the collaboration between PRNEWS.IO and Brokeree Solutions.…

Bojoko Used PRNEWS.IO to Enhance Visibility and Expand Audience in iGaming

Christoffer Ødegården, the Head of Casino at Bojoko, invites us to explore their success story in…

Digital Funnel Used PRNEWS.IO to Overcome Challenges in Securing High-Quality Media Placements for Clients

About Digital Funnel Digital Funnel is a full-service digital marketing agency based in Ireland and the…

This is “Importance of Research in Public Relations Management”, section 8.1 from the book Public Relations (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here .

This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms.

This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz in an effort to preserve the availability of this book.

Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page .

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page . You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here .

8.1 Importance of Research in Public Relations Management

Public relations professionals often find themselves in the position of having to convince management to fund research, or to describe the importance of research as a crucial part of a departmental or project budget. Research is an essential part of public relations management. Here is a closer look at why scholars argued that conducting both formative and evaluative research is vital in modern public relations management:

- Research makes communication two-way by collecting information from publics rather than one-way, which is a simple dissemination of information. Research allows us to engage in dialogue with publics, understanding their beliefs and values, and working to build understanding on their part of the internal workings and policies of the organization. Scholars find that two-way communication is generally more effective than one-way communication, especially in instances in which the organization is heavily regulated by government or confronts a turbulent environment in the form of changing industry trends or of activist groups. See, for example, Grunig (1984), pp. 6–29; Grunig (1992a; 2001); Grunig, Grunig, and Dozier (2002); Grunig and Repper (1992).

- Research makes public relations activities strategic by ensuring that communication is specifically targeted to publics who want, need, or care about the information. Ehling and Dozier (1992). Without conducting research, public relations is based on experience or instinct, neither of which play large roles in strategic management. This type of research prevents us from wasting money on communications that are not reaching intended publics or not doing the job that we had designed them to do.

- Research allows us to show results , to measure impact, and to refocus our efforts based on those numbers. Dozier and Ehling (1992). For example, if an initiative is not working with a certain public we can show that ineffectiveness statistically, and the communication can be redesigned or eliminated. Thus, we can direct funds toward more successful elements of the public relations initiative.

Without research, public relations would not be a true management function . It would not be strategic or a part of executive strategic planning, but would regress to the days of simple press agentry, following hunches and instinct to create publicity. As a true management function, public relations uses research to identify issues and engage in problem solving, to prevent and manage crises, to make organizations responsive and responsible to their publics, to create better organizational policy, and to build and maintain long-term relationships with publics. A thorough knowledge of research methods and extensive analyses of data also allow public relations practitioners a seat in the dominant coalition and a way to illustrate the value and worth of their activities. In this manner, research is the strategic foundation of modern public relations management. Stacks and Michaelson (in press).

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Importance of research and evaluation in public relations

Related Papers

Melissa Dodd

Communicare: Journal for Communication Studies in Africa

Fortune Tella

The importance of research by public relations practitioners has been highlighted by leading scholarsin most developed countries. However, studies show that the use of research by practitionersis more talked about than actually done. In Ghana, little is known about how practitioners useresearch. This paper therefore attempts to add to the limited literature by investigating whetherpublic relations (PR) practice in Ghana is informed by research. Data was collected from 93 PRpractitioners using a survey. The results suggest that although research is used by practitioners,the emphasis appears to be on media monitoring and content analysis. The implication is thatresearch cannot be fully appreciated if it is based solely on the amount of publicity received.The value of PR in the eyes of management can only be enhanced if emphasis is placed on theimpact and outcome of research. Practitioners must therefore use a more scientific approach intheir research activities.

Fatima Al Shamsi

Research is essential element in public relation. It's not necessary to have been ambiguous, expensive or complex. There is one way to ensure that Public Relation research arrives on time, on budget and gives the right result to create organizational. This paper will discover the importance of research and research steps in public relations in the UAE organizations. It ended that many PR offices do care about the research but still research needs more awareness and development in the future. More researches need to be collected in the PR field.

JOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN HUMANITIES

tanushri mukherjee

There is no second opinion on the fact that in today's highly digitalized communication world, PR has emerged as an indispensable function in almost every organization regardless of its size and nature and it is the most important requirement for securing the desired outcome for every business policy or business initiative. It is also true that this profession is evolving everyday at an accelerating rate ever since the advent of Digital PR and various new and innovative forms of content messaging. But one should not forget the fact that no matter how experienced you are or how much skills you possess, the core is that until and unless you take help of research in planning and executing PR plans or strategies either by being updated about the current trends in information distribution or having an analytical data of the demographic profile of public or by conducting content analysis or readership studies etc, you cannot expect a desired outcome of your PR Programmes and PR strate...

Hallel Onoh

Lewis Ombachi

Effective businesses should invest money into communications research when it comes to optimizing service delivery and customer pleasure. This is where the claim comes in since it ensures the company is prepared to answer concerns about use, branding, advertising, new product launch, and price. Gaining such knowledge is essential for two reasons: predicting the behavior of other businesses and gauging customer response to the company's policies. Given the organization's tight budget, the PR team must allocate resources toward this kind of study to improve the company's public and internal perception

The purpose of this paper is to identify and rank the most important topics for research in the field of public relations. An associated outcome was to propose the research questions most closely linked to the prioritised topics. An international Delphi study on the priorities for public relations research, conducted in 2007 among academics, practitioners and senior executives of professional and industry bodies was used to investigate expert opinion on research priorities for public relations. This choice of qualitative methodology replicated earlier studies by McElreath, White and Blamphin, Synnott and McKie, and Van Ruler et al. The role of public relations in the strategic operation of organisations, and the creation of value by public relations through social capital and relationships were ranked most highly. Some outcomes were comparable with earlier studies; for instance, evaluation of public relations programmes ranked third in this study and was among the leaders in the Synnott and McKie study. Only the topic “management of relationships” was wholly new, whereas “impact of technology on public relations practice and theory” ranked much lower than a decade ago.

Zachary Ochuodho

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Corporate Communications: An International Journal

Gary P Radford

International Journal of Communication and Public Relation

Jeferson Nyakamba

Public Relations Review

James E Grunig

Karla Gower

Communicare

Albert A Anani-Bossman (PhD)

Handbook of Public Relations

Zülfiye Acar Şentürk

Cheng Ean (Catherine) Lee , Kumu Krish

Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG eBooks

Martina Arabadzhieva

Revista Espaço Pedagógico

Isabel Pinho

International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management

Badreya Al-Jenaibi

Marketing of Scientific and Research Organizations

Dariusz Tworzydło

Miri Levin-Rozalis

International Public Relations Review

Jim Macnamara

Fanny Nombulelo Agnes Malikebu(Miss).

NMSU Business Outlook

Jeremy Sierra , Michael R Hyman

Public Relations and the Power of Creativity

Kristina Henriksson

PRism Online PR Journal

Elspeth Tilley

Chehou OUSSOUMANOU

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

Effective ways to communicate research in a journal article

Oxford Academic: Journals

We publish over 500 high-quality journals, with two-thirds in partnership with learned societies and prestigious institutions. Our diverse journal offerings ensure that your research finds a home alongside award-winning content, reaching a global audience and maximizing impact.

- By Megan Taphouse , Anne Foster , Eduardo Franco , Howard Browman , and Michael Schnoor

- August 12 th 2024

In this blog post, editors of OUP journals delve into the vital aspect of clear communication in a journal article. Anne Foster (Editor of Diplomatic History ), Eduardo Franco (Editor-in-Chief of JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute and JNCI Monographs ), Howard Browman (Editor-in-Chief of ICES Journal of Marine Science ), and Michael Schnoor (Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Leukocyte Biology ) provide editorial recommendations on achieving clarity, avoiding common mistakes, and creating an effective structure.

Ensuring clear communication of research findings

AF : To ensure research findings are clearly communicated, you should be able to state the significance of those findings in one sentence—if you don’t have that simple, clear claim in your mind, you will not be able to communicate it.

MS : The most important thing is clear and concise language. It is also critical to have a logical flow of your story with clear transitions from one research question to the next.

EF : It is crucial to write with both experts and interested non-specialists in mind, valuing their diverse perspectives and insights.

Common mistakes that obscure authors’ arguments and data

AF : Many authors do a lovely job of contextualizing their work, acknowledging what other scholars have written about the topic, but then do not sufficiently distinguish what their work is adding to the conversation.

HB : Be succinct—eliminate repetition and superfluous material. Do not attempt to write a mini review. Do not overinterpret your results or extrapolate far beyond the limits of the study. Do not report the same data in the text, tables, and figures.

The importance of the introduction

AF : The introduction is absolutely critical. It needs to bring them straight into your argument and contribution, as quickly as possible.

EF : The introduction is where you make a promise to the reader. It is like you saying, “I identified this problem and will solve it.” What comes next in the paper is how you kept that promise.

Structural pitfalls

EF : Remember, editors are your first audience; make sure your writing is clear and compelling because if the editor cannot understand your writing, chances are that s/he will reject your paper without sending it out for external peer review.

HB : Authors often misplace content across sections, placing material in the introduction that belongs in methods, results, or discussion, and interpretive phrases in results instead of discussion. Additionally, they redundantly present information in multiple sections.

Creating an effective structure

AF : I have one tip which is more of a thinking and planning strategy. I write myself letters about what I think the argument is, what kinds of support it needs, how I will use the specific material I have to provide that support, how it fits together, etc.

EF : Effective writing comes from effective reading—try to appreciate good writing in the work of others as you read their papers. Do you like their writing? Do you like their strategy of advancing arguments? Are you suspicious of their methods, findings, or how they interpret them? Do you see yourself resisting? Examine your reactions. You should also write frequently. Effective writing is like a physical sport; you develop ‘muscle memory’ by hitting a golf ball or scoring a 3-pointer in basketball.

The importance of visualizing data and findings

MS : It is extremely important to present your data in clean and well-organized figures—they act as your business card. Also, understand and consider the page layout and page or column dimensions of your target journal and format your tables and figures accordingly.

EF : Be careful when cropping gels to assemble them in a figure. Make sure that image contrasts are preserved from the original blots. Image cleaning for the sake of readability can alter the meaning of results and eventually be flagged by readers as suspicious.

The power of editing

AF : Most of the time, our first draft is for ourselves. We write what we have been thinking about most, which means the article reflects our questions, our knowledge, and our interests. A round or two of editing and refining before submission to the journal is valuable.

HB : Editing does yourself a favour by minimizing distractions-annoyances-cosmetic points that a reviewer can criticize. Why give reviewers things to criticize when you can eliminate them by submitting a carefully prepared manuscript?

Editing mistakes to avoid

AF : Do not submit an article which is already at or above the word limit for articles in the journal. The review process rarely asks for cuts; usually, you will be asked to clarify or add material. If you are at the maximum word count in the initial submission, you then must cut something during the revision process.

EF : Wait 2-3 days and then reread your draft. You will be surprised to see how many passages in your great paper are too complicated and inscrutable even for you. And you wrote it!

Featured image by Charlotte May via Pexels .

Megan Taphouse , Marketing Executive

Anne Foster , (Editor of Diplomatic History)

Eduardo Franco , (Editor-in-Chief of JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer institute and JNCI Monographs)

Howard Browman , (Editor-in-Chief of ICES Journal of Marine Science)

Michael Schnoor , (Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Leukocyte Biology)

- Publishing 101

- Series & Columns

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Open access

- Published: 07 August 2024

Ethical considerations in public engagement: developing tools for assessing the boundaries of research and involvement

- Jaime Garcia-Iglesias 1 ,

- Iona Beange 2 ,

- Donald Davidson 2 ,

- Suzanne Goopy 3 ,

- Huayi Huang 3 ,

- Fiona Murray 4 ,

- Carol Porteous 5 ,

- Elizabeth Stevenson 6 ,

- Sinead Rhodes 7 ,

- Faye Watson 8 &

- Sue Fletcher-Watson 7

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 10 , Article number: 83 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1267 Accesses

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

Public engagement with research (PEwR) has become increasingly integral to research practices. This paper explores the process and outcomes of a collaborative effort to address the ethical implications of PEwR activities and develop tools to navigate them within the context of a University Medical School. The activities this paper reflects on aimed to establish boundaries between research data collection and PEwR activities, support colleagues in identifying the ethical considerations relevant to their planned activities, and build confidence and capacity among staff to conduct PEwR projects. The development process involved the creation of a taxonomy outlining key terms used in PEwR work, a self-assessment tool to evaluate the need for formal ethical review, and a code of conduct for ethical PEwR. These tools were refined through iterative discussions and feedback from stakeholders, resulting in practical guidance for researchers navigating the ethical complexities of PEwR. Additionally, reflective prompts were developed to guide researchers in planning and conducting engagement activities, addressing a crucial aspect often overlooked in formal ethical review processes. The paper reflects on the broader regulatory landscape and the limitations of existing approval and governance processes, and prompts critical reflection on the compatibility of formal approval processes with the ethos of PEwR. Overall, the paper offers insights and practical guidance for researchers and institutions grappling with ethical considerations in PEwR, contributing to the ongoing conversation surrounding responsible research practices.

Plain English summary

This paper talks about making research fairer for everyone involved. Sometimes, researchers ask members of the public for advice, guidance or insight, or for help to design or do research, this is sometimes known as ‘public engagement with research’. But figuring out how to do this in a fair and respectful way can be tricky. In this paper, we discuss how we tried to make some helpful tools. These tools help researchers decide if they need to get formal permission, known as ethical approval, for their work when they are engaging with members of the public or communities. They also give tips on how to do the work in a good and fair way. We produced three main tools. One helps people understand the important words used in this kind of work (known as a taxonomy). Another tool helps researchers decide if they need to ask for special permission (a self-assessment tool). And the last tool gives guidelines on how to do the work in a respectful way (a code of conduct). These tools are meant to help researchers do their work better and treat everyone involved fairly. The paper also talks about how more work is needed in the area, but these tools are a good start to making research fairer and more respectful for everyone.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In recent decades, “public involvement in research” has experienced significant development, becoming an essential element of the research landscape. In fact, it has been argued, public involvement may make research better and more relevant [ 7 , p. 1]. Patients’ roles, traditionally study participants, have transformed to become “active partners and co-designers” [ 17 , p. 1]. This evolution has led to the appearance of a multitude of definitions and terms to refer to these activities. In the UK, the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, defines public engagement as the “many ways organisations seek to involve the public in their work” [ 9 ]. In this paper, we also refer to “public involvement,” which is defined as “research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them” (UK Standards for Public Involvement). Further to this, the Health Research Authority (also in the UK), defines public engagement with research as “all the ways in which the research community works together with people including patients, carers, advocates, service users and members of the community” [ 6 ]; [ 9 ]. These terms encompass a wide variety of theorizations, levels of engagement, and terminology, such as ‘patient-oriented research’, ‘participatory’ research or services or ‘patient engagement’ [ 17 , p. 2]. For this paper, we use the term ‘public engagement with research’ or PEwR in this way.

Institutions have been set up to support PEwR activities. In the UK these include the UK Standards for Public Involvement in Research (supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research), INVOLVE, and the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE). Most recently, in 2023, the UK’s largest funders and healthcare bodies signed a joint statement “to improve the extent and quality of public involvement across the sector so that it is consistently excellent” [ 6 ]. In turn, this has often translated to public engagement becoming a requisite for securing research funding or institutional ethical permissions [ 3 , p. 2], as well as reporting and publishing research [ 15 ]. Despite this welcomed infrastructure to support PEwR, there remain gaps in knowledge and standards in the delivery of PEwR. One such gap concerns the extent to which PEwR should be subject to formal ethical review in the same way as data collection for research.

In 2016, the UK Health Research Authority and INVOLVE published a joint statement suggesting that “involving the public in the design and development of research does not generally raise any ethical concerns” [ 7 , p. 2]. We presume that this statement is using the phrase ‘ethical concerns’ to narrowly refer to the kinds of concerns addressed by a formal research ethics review process, such as safeguarding, withdrawal from research, etc. Footnote 1 . To such an extent, we agree that public involvement with research is not inherently ‘riskier’ than other research activities.