What's the Israel-Palestinian conflict about and how did it start?

- Medium Text

WHAT ARE THE ORIGINS OF THE CONFLICT?

What major wars have been fought since then, what attempts have there been to make peace.

WHERE DO PEACE EFFORTS STAND NOW?

What are the main israeli-palestinian issues.

Sign up here.

Compiled by Reuters journalists; Editing by Edmund Blair

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Brazilian flag raised at Argentine embassy in Caracas

The Brazilian flag was raised on Thursday at the residence of Argentina's ambassador to Venezuela in Caracas, according to a Reuters witness, after Argentine diplomats were expelled from the country.

Home — Essay Samples — War — Israeli Palestinian Conflict — Israel-Palestine Conflict: Historical Context, Causes, and Resolution

Israel-palestine Conflict: Historical Context, Causes, and Resolution

- Categories: Israeli Palestinian Conflict

About this sample

Words: 612 |

Published: Jan 31, 2024

Words: 612 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical context, causes of the conflict, major parties involved, international involvement, consequences and impacts, attempts at resolution, current situation and future prospects.

- United Nations. "Israel-Palestine Conflict: An Overview." https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/israel-palestine-conflict/

- BBC News. "Israel and Palestinians: The Conflict Explained." https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-43789452

- Council on Foreign Relations. "The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict." https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/israeli-palestinian-conflict

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: War

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1057 words

3 pages / 1286 words

2 pages / 1074 words

1 pages / 655 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Israeli Palestinian Conflict

Conflict between Israel and Palestine has far-reaching implications, not only for the region but also for the global economy and politics. Possible scenarios of how the conflict might shape global economic and political [...]

One of the most powerful ways to understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is through personal narratives. These stories provide a window into the everyday lives of individuals on both sides who are affected by the ongoing [...]

Rooted in historical, religious, and territorial grievances, the conflict has drawn the attention of numerous global actors, each attempting to influence its resolution. This essay delves into the multifaceted roles played by [...]

The conflict between Israel and Palestine has persisted for decades, marked by cycles of violence, failed negotiations, and deep-rooted animosities. As the world entered 2023, the prospects for peace remained uncertain amidst [...]

The constant battle between Israel and the Arab Nation has stemmed for thousands of years, a conflict that originates so far back to the point that Islam didn’t exist. Most of the conflict was not based on the theological [...]

The political aspect and amount of acknowledgment of human rights of any country or part of the world is a crucial facet when considering violence, environmental issues, economic issues, education, and much more. The middle east [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The History Behind Tensions Between Israelis And Palestinians

The conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians is long and complex. NPR's Lulu Garcia-Navarro explains what has lead up to the latest attacks, and how it's different than before.

Copyright © 2021 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Timeline

Explore the history and important events behind the long-standing Middle East conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians from 1947 to today.

Smoke rises in Gaza following Israeli strikes on October 9, 2023.

Source: Mohammed Salem / Reuters

The conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians reflects a long-standing struggle in the region encompassing the land between the Jordan River to the east and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. That conflict has deep historical roots, shaped by statehood claims from the Israelis and the Palestinians that have been supported by various international agendas and activities over time.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dates back more than a century, with flashpoints building from the United Nations’ 1947 initial UN Partition Plan to the 1973 Yom Kippur War, to the recent Israel-Hamas war sparked in October 2023.

Despite continued efforts at brokering peace—including the 1979 Camp David Accords, the Oslo Accords of the 1990s, and the 2020 Abraham Accords—conflict has persisted.

This timeline explores some of the pivotal moments in the conflict from 1947 to today.

Universal History Archive

The UN General Assembly passes Resolution 181 calling for the partition of the Palestinian territories into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. The resolution also envisions an international, UN-run body to administer Jerusalem. The Palestinian territories had been under the military and administrative control of the United Kingdom (known as a mandate) since the 1917 defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Civil strife and violence between the Jewish and Arab communities of the Palestinian territories intensifies.

Saar Yaacov/Israel GPO

Israel declares its independence as the British rule ends. Sparked by Israel’s declaration of independence, the first Arab-Israeli War begins. Egypt (supported by Saudi Arabian, Sudanese, and Yemeni troops), Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria invade Israel. The fighting continues until 1949, when Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria sign armistice agreements.

Bettmann / Getty Images

Over the course of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, at least seven hundred thousand Palestinian refugees flee their homes in an exodus known to Palestinians as the nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”). Israel wins the war, retaining the territory provided to it by the United Nations and capturing some of the areas designated for the imagined future Palestinian state. Israel gains control of West Jerusalem, Egypt gains the Gaza Strip, and Jordan gains the West Bank and East Jerusalem, including the Old City and its historic Jewish quarter. In 1948, the UN General Assembly passes Resolution 194, which calls for the repatriation of Palestinian refugees . The Palestinians will later point to Resolution 194 as having established a “right of return” for Palestinian refugees and their descendants. The specific parameters of that return are debated in the decades that follow, including among many descendants from the 1948 refugees and the three hundred thousand Palestinians who will flee their homes during the June 1967 war.

Israel GPO.

Israel and several of its Arab neighbors fight the Six-Day War. Israel wins a decisive victory: it suffers seven hundred casualties; its adversaries suffer nearly twenty thousand. Israel emerges with control of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—areas inhabited primarily by Palestinians—as well as all of East Jerusalem. Israel also takes control of Syria’s Golan Heights and the Sinai Peninsula, which is part of Egypt. Israel will stay in the Sinai Peninsula until April 1982.

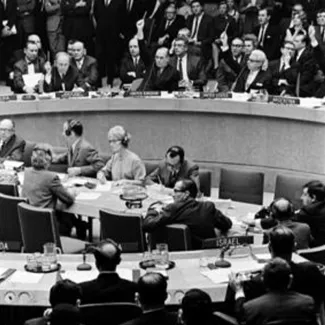

Yutaka Nagata / United Nations

The UN Security Council passes Resolution 242 calling for Israeli “withdrawal … from territories occupied in the recent conflict” and for the termination of “states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgement of the sovereignty , territorial integrity, and political independence of every state in the area and the right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries.” The resolution establishes the concept of land for peace .

Another Arab-Israeli war, known variously as the Yom Kippur War, the Ramadan War, and the October War, is fought when Egypt and Syria attempt to retake the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights. Cold War tensions spike as the Soviet Union aids Egypt and Syria and the United States aids Israel. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries begins an oil embargo on countries that support Israel, and the price of oil skyrockets. The fighting ends after a UN-sponsored cease-fire (negotiated by the United States and the Soviet Union) takes hold. The UN Security Council passes Resolution 338, which calls for implementing UN Security Council Resolution 242.

Warren K. Leffler / Library of Congress.

Israel and Egypt sign the Camp David Accords, which establish a basis for a peace treaty between the two countries. The accords also commit the Israeli and Egyptian governments, along with other parties, to negotiate the disposition of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

François Lochon / Getty Images

Egypt and Israel sign a peace treaty, the first between Israel and one of its Arab neighbors. The treaty commits Israel to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and evacuate its settlements there. The termination of the state of war between Egypt and Israel leads to the normalization of diplomatic and commercial relations between the two countries. Israel’s prime minister and Egypt’s president exchange letters reaffirming their commitment—outlined in the Camp David Accords—to negotiate the disposition of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Jim Hollander / Reuters

An Israeli driver kills four Palestinians in a car accident that sparks the first intifada, or uprising, against Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. The image of Palestinians throwing rocks at Israeli tanks becomes the enduring image of the intifada. Over the next six years, roughly 200 Israelis and 1,300 Palestinians are killed.

A Palestinian cleric named Sheikh Ahmed Yassin establishes the militant group Hamas as an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas endorses jihad as a way to regain territory for Muslims; the United States designates Hamas a foreign terrorist organization in 1997.

Ali Jareki / Reuters

King Hussein of Jordan relinquishes his country’s claims to the West Bank and East Jerusalem in favor of the claims of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In December of the same year, PLO Chairman Yasir Arafat denounces violence, recognizes Israel’s right to exist, and acknowledges UN Security Council Resolution 242 and the concept of land for peace. The United States responds to Arafat’s announcement by beginning direct talks with him, though it suspends the talks following a Palestinian terrorist attack against Israel.

David Valdez / U.S. National Archives

The Madrid Peace Conference begins, sponsored jointly by the United States and the Soviet Union . Israeli, Jordanian, Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian delegates attend the first negotiations among those parties. The talks proceed along bilateral tracks between Israel and its neighbors, though the Lebanese join the Syrian delegation and the Jordanian team includes Palestinian representatives. A multilateral track includes the wider Arab world and addresses regional issues. The talks last for two years without any breakthroughs.

Saar Yaacov / Israel GPO.

Secret negotiations in Norway result in the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, also known as the Oslo Accords. Before the accords are signed, Israel and the PLO recognize each other in an exchange of letters. Israel and the PLO agree to the creation of the Palestinian Authority to temporarily administer the Gaza Strip and West Bank. Israel also agrees to begin withdrawing from parts of the West Bank, though large swaths of land and Israeli settlements remain under the Israeli military’s exclusive control. The Oslo Accords envision a peace agreement by 1999. Palestinian leader Arafat, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 for their efforts on the Oslo Accords.

Patrick Baz / AFP / Getty Images

The Israelis and the Palestinians sign the Gaza-Jericho Agreement, which begins implementation of the Oslo Accords. The agreement provides for an Israeli military withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho, a town in the West Bank, and for a transfer of authority from Israeli administration to the newly formed Palestinian Authority. The agreement also establishes the structure and composition of the Palestinian Authority, its jurisdiction and legislative powers, a Palestinian police force, and relations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Arafat returns to the Gaza Strip after a long absence.

Sa'ar Ya'acov / Israel Government Press Office Photo

Israel and Jordan sign a peace treaty, settling their territorial dispute and agreeing to future cooperation in sectors such as trade and tourism. This is Israel’s second peace treaty with an Arab state. It accords special administrative responsibilities for Jerusalem’s Muslim holy places to Jordan.

Israeli and Palestinian negotiators sign the Interim Agreement, sometimes called Oslo II. It gives the Palestinians control over additional areas of the West Bank and defines the security, electoral, public administration, and economic arrangements that will govern those areas until a final peace agreement is reached in 1999.

President Bill Clinton hosts Israeli and Palestinian leaders for talks at Camp David. Reports indicate that Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak is prepared to accept, among other things, Palestinian sovereignty over some 91 percent of the West Bank and certain parts of Jerusalem. The deal would include a land swap in which some Israeli land would go to the Palestinians in compensation for the remaining 9 percent of the West Bank, which would go to Israel. Two weeks of intensive discussion, however, fails to produce an agreement. President Clinton blames Arafat for the failure. Before leaving office several months later, Clinton lays out proposals for both sides. Talks between them continue, but without success.

Natalie Behring / Reuters

Israeli politicians, including Ariel Sharon, a controversial retired Israeli general, visit the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. The Palestinians view the visit as an effort to change the status quo at the holy site. The ensuing demonstrations turn violent, marking the beginning of a second intifada. It will last until 2005 and be markedly more violent than the first intifada. Four thousand Palestinians and one thousand Israelis die.

Nir Elias / Reuters

A terrorist attack kills thirty people at a Passover celebration at a hotel in the Israeli city of Netanya. As a result, the Israeli military reoccupies portions of the West Bank, including the city of Ramallah, where the Palestinian Authority is located and where Arafat has his West Bank headquarters.

Israel begins building a security barrier in the West Bank to protect Israeli cities and towns from terrorist attacks. The barrier, which is a wall in some stretches and a fence in others, is controversial because in places it cuts deep into West Bank territory to protect settlements. The Palestinians are cut off from Jerusalem, some Palestinian villages are sliced in half, and some Palestinians are unable to get to work or school as a result of the security barrier’s path. Israel’s Supreme Court forces changes in the barrier’s route, but the barrier continues to impede Palestinian movement and commerce in certain areas.

Ali Jarekji / Reuters

The Quartet, an informal group created to pursue Middle East peace comprising the United States, Russia, the United Nations, and the European Union , puts forth a Road Map for Peace based on the outline President George W. Bush offered in his 2002 speech. The road map lays out a plan for peace based on Palestinian reforms and a cessation of terrorism in return for an end to Israeli settlements and a new Palestinian state.

Paul Hanna / Reuters

Israel begins a unilateral withdrawal of settlers and military forces from the Gaza Strip. The Israeli military remains in control of Gaza’s borders (except the Gaza-Egypt border, which is controlled by Egypt), airspace, and coastline. After Israel’s withdrawal, Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad , and other smaller militant groups fire rockets from Gaza into southern Israel.

Ahmed Jadallah / Reuters

Hamas defeats Fatah, a Palestinian political faction founded in 1950s which was a long-dominant faction within the PLO, in Palestinian elections. The United States and other countries suspend their aid to the Palestinian Authority because they consider Hamas to be a terrorist organization. Fatah and Hamas make a deal to govern the West Bank and Gaza Strip together. The deal quickly fails, and Hamas takes over the Gaza Strip in 2007.

Ronen Zvulun / Reuters

Hamas operatives kidnap an Israeli soldier named Gilad Shalit on Israeli soil near the Gaza Strip. The Israeli military tries and fails to free him. He is held captive in Gaza until Israel—with the help of Egypt and the United States—negotiates his release in 2012.

Ammar Awad / Reuters

Israel attacks the Gaza Strip following nearly eight hundred rocket attacks from Gaza on Israeli towns in the months of November and December. The war lasts less than a month but kills hundreds of civilians, in addition to hundreds of combatants, and sparks international criticism.

Jonathan Ernst / Reuters

Secretary of State John Kerry seeks to restart final status negotiations. The process begins with the Israeli’s agreement to release 104 Palestinian prisoners and the Palestinians’ agreement not to use their new observer state status at the United Nations to advance the cause of statehood. Negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority collapsed in April 2014 over such issues as Israeli settlement growth, the status of a final round of prisoners, and Palestinian attempts to join several international organizations.

Suhaib Salem / Reuters

The PLO and Hamas sign an agreement to form a unity government. Tensions between the factions remain, however, and no unity government is formed. Gaza and the West Bank remain disconnected and under the control of rival Palestinian leaderships.

Baz Ratner / Reuters

After tit-for-tat attacks on Israeli and Palestinian civilians by extremists on both sides, Israel invades the Gaza Strip. The operation, code-named Protective Edge, lasts for fifty days, killing about two thousand Gazans, sixty-six Israeli soldiers, and five Israeli civilians. Unlike the conflicts from 2008 to 2009 and in 2012, Palestinian rocket fire targets major Israeli cities. The war ends after the United States, in consultation with Egypt, Israel, and other regional powers, brokers a cease-fire .

Muhammad Hamed / Reuters

Changing long-standing U.S. policy, U.S. President Donald Trump formally recognizes Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. He also pledges to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to that city, though the move is not set to occur immediately. Numerous foreign leaders, including those of Egypt, France, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, along with UN Secretary-General António Guterres, criticize the policy change. It also sparks protests and violence throughout East Jerusalem, Gaza, and the West Bank, as well as in Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and Jordan. In January 2018, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas declines to meet with U.S. Vice President Mike Pence during Pence’s trip to the region.

Carlos Barria / Reuters

The Trump administration recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, which Israel had formally annexed from Syria in 1981. The United States is the first country other than Israel to recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the territory.

Trump unveils his administration’s proposed Israeli-Palestinian peace plan, crafted by U.S. and Israeli diplomats without Palestinian input. The plan calls for a two-state solution with significant economic aid to the Palestinians. Many analysts criticize the plan as being one sided, stipulating impossible requirements for Palestinian statehood and paving the way for Israeli annexation of the West Bank. Palestinian authorities reject the plan immediately. Following the plan’s announcement, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announces Israel’s plan to annex portions of the West Bank as outlined in Trump’s proposal.

Tom Brenner / Reuters

Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates agree to normalize diplomatic relations with Israel, becoming the first Arab countries to do so in over twenty-five years. In return, Israel announces the suspension of its plans to annex territory in the West Bank. Morocco and Sudan subsequently also sign on to the agreement and normalize relations with Israel.

Evictions of Palestinians in East Jerusalem and clashes at al-Aqsa Mosque spark conflict between Israel and Hamas. Over two hundred people in Gaza and at least ten in Israel die. The Joe Biden administration helps mediate a truce and restores some U.S. aid and diplomatic contact with the Palestinians.

Israel launches a counterterrorism operation in the West Bank in response to attacks by Palestinians against Jewish Israelis. The operation and resulting resurgence contribute to the deadliest year for both sides since 2005, an uptick in violence that only turned out to rise in 2023.

Mohammed Salem / Reuters

Hamas launches an unprecedented surprise attack on Israel, leading to an explosion of violence. According to the Israeli government, the attack kills approximately 1,200 people, many of them civilians. Over 200 people are also taken hostage. The attack is the deadliest in Israel’s history. Hamas military leaders justify the attack by citing Israel’s long-running blockade on Gaza and its occupation of Palestinian lands. Following the attack, Israel launches a deadly counter offensive aiming to eradicate Hamas in Gaza. International bodies, including the International Criminal Court and International Court of Justice, have since issued investigations into Israeli and Hamas officials for violating international law . Both parties reject these claims. Despite a growing humanitarian crisis, as well as numerous attempts to broker ceasefire deals, the warring parties remain in conflict. As of July 2024, over 35,000 Palestinians have been killed, many of them civilians. Over 100 Israeli hostages are still held by Hamas.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Worried about violence, threats as election nears? Just say no.

Alone in the spotlight but not alone

The way forward for Democrats — and the country

Panelists Tarek Masoud (from left), Amaney Jamal, David Makovsky, Khalil Shikaki, and Shai Feldman at Klarman Hall.

Photos by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hope for progress survives terror and war

Christina Pazzanese

Harvard Staff Writer

Can the Israelis and Palestinians find peace? Scholars discuss — and debate — long history of conflict, prospects for a durable accord

Scholars revisited the long history of Israel-Palestine conflict leading up to the Oct. 7 terror attack by Hamas and weighed potential steps toward peace before hundreds of Harvard community members at a recent Klarman Hall event.

“We’re here because of dead civilians, Jewish and Arab,” said moderator Tarek Masoud, faculty chair of the Middle East Initiative and Ford Foundation Professor of Democracy and Governance at Harvard Kennedy School , which co-hosted the Nov. 20 discussion with Harvard Business School .

The third such gathering convened by the Middle East Initiative in recent weeks, the event, which unfolded as Israel and Hamas negotiated a cease fire and hostage deal, was an attempt to share scholarly expertise with students so they can make better sense of the crisis and perhaps contribute to a solution, Masoud said. Srikant Datar, dean of the Business School, urged attendees to approach the talk “with open-mindedness and a commitment to empathy and learning.”

It’s important to separate the terror unleashed by Hamas from the plight of Palestinians in Gaza, said David Makovsky, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy who served as senior adviser to the State Department’s Special Envoy for Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations from 2013 to 2014.

“This was a deliberate decision by the Hamas leadership to do [these] atrocities,” he said. “The people of Gaza did not commit these atrocities.”

Hamas chose to attack at a moment when its leadership believed Israel had been weakened by internal strife over the overhaul of Israel’s judiciary by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, according to Makovsky. Another key factor was the worry that a normalization pact between Saudi Arabia and Israel would be “game over” for the terror group, leaving Hamas isolated from the other Arab nations that had struck accords with Israel.

Panelists agreed that Hamas members are terrorists, not freedom fighters. They also agreed that Netanyahu has used Hamas in the past to help thwart peace efforts.

“The current Israeli government, led by Netanyahu, is the same government that has been trying for most of the last 16 years to create conditions, or to support conditions, that have essentially prevented any progress in that direction,” said Khalil Shikaki, director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research in Ramallah. “Hamas was very instrumental in providing that kind of environment.”

At times, Masoud politely refereed passionate disagreements among the scholars over who did what during the decades that precipitated this crisis, further underscoring the enormous challenge facing those who wish to engage in reasoned debate on the subject.

On what the way forward looks like, the panelists were uncertain.

For Netanyahu, success in the short term would be to eliminate Hamas’ fighting and governing capacity and to free the hostages held in Gaza, said Shai Feldman, a professor of Israeli politics and society at Brandeis University. But eventually, the Israeli people will force a “major reckoning” internally about the policies and strategies the prime minister and his allies adopted.

Asked what role the international community can play to facilitate peace, Feldman said that if Hamas is defeated, perhaps a regional coalition made up Egypt, Jordan, and/or Saudi Arabia could temporarily take control in Gaza and make an effort to rejuvenate the Palestinian Authority, which was pursuing a two-state solution with Israel before Hamas rose to power in 2006.

“If violence were going to solve this conflict, it would have already,” said Amaney Jamal, dean of the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and a daughter of Palestinian immigrants. “I would rather see our policies and efforts and the Palestinian Authority … make the message of peace and reconciliation far more attractive than any other message.”

She added: “This starts with people seeing tangible changes on the ground, but also political leaders to step up and sanction their leaders when they’re espousing violence and vitriol and hatred and the dehumanization of the other. We have been victims of this conflict since we were born. We would love to turn the page and be able to live with peace and dignity as Israelis, as Palestinians.”

Share this article

You might like.

Key is for leaders, voters to stand in solidarity against it, political scientists say

Cognitive neurologist sees lessons in age-focused conversations around Biden’s exit, but also a lack of nuance

Danielle Allen is more worried about identity politics and gaps in civic education than the power of delegates

17 books to soak up this summer

Harvard Library staff recommendations cover romance, fantasy, sci-fi, mystery, memoir, music, politics, history

Beginning of end of HIV epidemic?

Scientists cautiously optimistic about trial results of new preventative treatment, prospects for new phase in battle with deadly virus

- How We Work

- CrisisWatch

- Upcoming Events

- Event Recordings

- Afrique 360

- Hold Your Fire

- Ripple Effect

- War & Peace

- Photography

- For Journalists

The Israel-Palestine Crisis: Causes, Consequences, Portents

The confrontations across Israel-Palestine are well on the way to becoming one of the worst spasms of violence there in recent memory. In this Q&A, Crisis Group experts explain what is behind the explosive events and where they might lead.

How serious is the most recent flare-up in the conflict?

It is extremely serious, partly because it is taking place on several fronts at once: Israeli police actions against Palestinians protesting home evictions or praying at the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, cross-border fighting between Israel and Palestinian armed groups in Gaza, marches from Jordan on the West Bank border, and violence in Israel’s mixed cities – towns with significant numbers of Jewish and Palestinian citizens. Combined, these confrontations are well on their way to becoming one of the worst spasms in the recent history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The flare-up could get worse still, namely if Israel decides to launch a ground offensive into the Gaza Strip. Israeli officials are still reportedly considering this option, with tanks and heavy artillery close to the territory’s northern perimeter and already involved in fighting, though from the outside; residents in the northern parts of the strip have started evacuating their homes in response. The situation will be further compounded if Israel deploys its military battalions into the mixed cities, an option it also appears to be considering.

Even if the parties can bring some of the fighting to a halt through, for example, a Gaza ceasefire, all the underlying problems remain, now much further inflamed, and crying out for a far more serious effort to forge a durable solution than has been the case in the conflict to date.

The toll in human and material terms is already shattering. By 10 May, some 250 Palestinians had been injured during police operations against what started as peaceful protests in East Jerusalem. Since then, when Hamas, the Palestinian Islamist movement that governs Gaza, began firing rockets at Israel and Israel mounted retaliatory airstrikes, the fighting has become much bloodier. The health ministry in Gaza has recorded 830 Palestinians hurt and 119 killed, including 31 children, as a result of Israeli aerial and artillery bombardment. During the same period, nine Israelis, including one child, have been killed and over 400 injured in Hamas rocket attacks.

In an unprecedented wave of violence, dozens of people have been injured throughout Israel’s mixed cities and neighbourhoods. Some of the worst attacks occurred in Lod/Al-Lid. On 10 May, Palestinians set fire to a synagogue and police cars, and a Jewish gunman shot dead a Palestinian during altercations, after which the government placed the city under a nightly curfew, which ultra-nationalist Jews subsequently breached. Authorities also imposed a state of emergency – for the first time since Israel dismantled its military rule over its Palestinian citizens in 1966 – and moved Border Police units into the city from their main area of operations in the occupied West Bank. On 12 May, Israeli ultra-nationalists attacked Al-Lid’s Al-Omari mosque ahead of the curfew, which led the mayor, Yair Revivo, to declare a state of civil war.

Similar incidents took place elsewhere. Jewish mobs from Israel and Israeli settlements in the West Bank, organised through cell phones and social media, sought out and attacked Palestinians in various cities, at times under the gaze of Israeli security forces nearby. In Acre, Palestinians assaulted a Jewish man, leaving him in serious condition. In Bat Yam, dozens of nationalist Jews bearing the Israeli flag assaulted a Palestinian citizen, who was hospitalised. In West Jerusalem, a Palestinian was stabbed on 12 May and remains in serious condition.

In the Gaza Strip, Israeli strikes have done enormous damage to buildings and civil infrastructure, bringing down several apartment and office towers and levelling government buildings, service facilities such as schools and banks, homes and security compounds, including several police stations. As of 13 May, Hamas had fired over 2,000 rockets and mortars at Israel (a number of which misfired, and most of which Israel intercepted with its Iron Dome air defence system, but some of which landed in Tel Aviv and other urban areas); and Israel had carried out hundreds of air and artillery strikes. Hamas’s firepower, both in terms of number of rockets and their reach, far surpasses earlier escalations, and Israeli retaliation has been swift and devastating, making this episode’s destruction more comparable to the four earlier Gaza wars – in 2006, 2008-2009, 2012 and 2014 – than any of the flare-ups in between.

Most significantly, perhaps, this occasion is the first since the September 2000 intifada when Palestinians have responded simultaneously and on such a massive scale throughout much of the combined territory of Israel-Palestine to the cumulative impact of military occupation, repression, dispossession and systemic discrimination.

What triggered it?

It all began with a number of separate but interrelated incidents in East Jerusalem, which escalated, became militarised and then metastasised, building on points of conflict that had been smouldering for years and now rapidly received oxygen.

One catalyst was at the entrance to Jerusalem’s Old City at the Damascus Gate, at the start of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, 13 April, when Israeli authorities banned East Jerusalem residents from congregating on the gate’s steps and barricaded the area. Damascus Gate is a social hub for many of the Old City’s Palestinian residents, a platform for civic and cultural gatherings and events. Palestinian youth saw the placement of metal barriers as a provocation and launched what became nightly protests; these were not linked to political factions or any other wider agenda. Within days, ultra-nationalist Jews responded by marching through central Jerusalem toward Damascus Gate, chanting “death to Arabs”. The outrage these marches aroused among Palestinians spilled over into the adjacent West Bank and neighbouring Jordan, while militant groups in Gaza fired dozens of rockets into Israel. Palestinians filmed attacks on Jews and posted them to social media to seek sympathy and support, while ultra-nationalist Israeli Jews roamed Jerusalem’s streets attacking Arabs. Following twelve days of violent confrontation in East Jerusalem, Israeli authorities took down the barricades on 25 April.

Next came a second trigger in the form of growing popular anger over an Israeli Supreme Court ruling – subsequently delayed – concerning the planned expulsion of four Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah, an East Jerusalem neighbourhood that connects the Old City to the West Bank. The case had been wending its way through the Israeli court system for years before landing in its uppermost forum. Local Palestinians organised daily iftar sit-ins to break the Ramadan fast and protest the expulsions, which were part of a sweep of at least 27 other households yet to be carried out. These attracted the attention of ultra-nationalist Jews, who, accompanied by newly elected Knesset member Itamar Ben Gvir, entered Sheikh Jarrah on 10 May to disrupt the protests and at times assault those who had gathered peacefully. Israeli police fired sponge bullets, stun grenades and skunk water, causing hundreds of injuries. Numerous Palestinians were subsequently beaten by police as they were taken into custody. Tensions and arrests are continuing to date.

Further inflaming the situation around this time was the decision by Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas, on 29 April, to “indefinitely postpone” legislative elections in the occupied Palestinian territories scheduled for 22 May. Abbas likely feared that his fractured Fatah movement would fare poorly in the polls, but the reason he cited for the postponement was the absence of Israeli assurances that East Jerusalem residents would be permitted to participate. In fact, Israeli authorities had disrupted election campaigning in East Jerusalem throughout April, arresting Palestinian politicians and their supporters. The detentions infuriated Palestinians across the political spectrum, as these actions threatened to obstruct their attempt at renewing their national institutions through the democratic process, as international actors had been encouraging them to do.

The fourth trigger proved the most serious. On the evening of 7 May, Israeli police clashed with young Palestinians and used force against worshippers at the Al-Aqsa mosque inside the walled Old City, injuring dozens. Police also closed the gates leading to the mosque, which is the third holiest site for Muslims after Mecca and Medina; such categorical access restrictions, even when in response to violent protest, nearly always lead to further escalation. The police worsened matters further when they blocked busloads of Palestinian citizens from entering Jerusalem on 8 May, preventing thousands of Muslims from reaching Al-Aqsa for prayers on laylat al-qadr , the holiest night of Ramadan. Israeli forces then attacked Muslim worshippers at the Holy Esplanade (Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount) that same evening. The following day, Israeli forces breached the compound, firing stun grenades and tear gas canisters at worshippers, pushing their way into the mosque and attacking people inside. Scores of Palestinians were injured and many detained. On 10 May, Israeli soldiers staged another raid and confiscated the keys to the mosque’s main gates.

The events of that day, 10 May, coincided with what Israelis celebrate as Jerusalem Day – what they see as the reunification of East Jerusalem, including the Old City, with West Jerusalem during the 1967 war. The same day, Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem had protested Jewish ultra-nationalist plans to march through the Old City toward Al-Aqsa. Following international, including U.S., pressure, Israeli authorities redirected the march to avert further violence, but tensions had already risen to dangerous levels.

Responding to the events in Jerusalem that same day, Hamas’s military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, admonished Israel to halt violence against Palestinians in the city. Palestinian armed factions had already started issuing warnings two weeks earlier, saying they would respond to the escalations in Jerusalem. On 10 May, the Joint Chamber of Palestinian Resistance Factions in the Gaza Strip issued an ultimatum, declaring that Israel had until 6pm local time to withdraw its forces from Al-Aqsa and Sheikh Jarrah, and to release all those it had detained during these events. Shortly after the deadline expired, Hamas fired a series of rockets toward Jerusalem. Israeli forces retaliated by launching airstrikes on Gaza, killing 28 people, including nine children, in the first few hours, and threatening an expanded response lasting days , including a ground invasion.

How is this set of events different from previous ones?

Militarily, Israel was caught off guard by Hamas’s expanded operational capacity to fire so many rockets at once and at such distant targets. On 13 May, Hamas unveiled its longer-range Ayyash rocket, firing one at Ramon International Airport outside Eilat at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. Politically, this series of events was a wake-up call for those in Israel hoping that the conflict is “containable” or even largely over – that they could ignore the Palestinian issue and pretend it had been largely settled in Israel’s favour. That sense has deepened over the last couple of years with the Abraham Accords normalising relations between Israel and important Gulf Arab states and the continued rise in the Israeli economy and living conditions. Israeli leaders also saw Hamas break from its Gazan confines by using its escalation with Israel to attempt to negotiate concessions on Jerusalem, not solely the lifting of the blockade on Gaza, as it had done in the past. In so doing, Hamas appeared to be usurping leadership of the Palestinian national movement from President Abbas and the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority.

While the 2006, 2008-2009, 2012 and 2014 wars were all focused on Gaza, the new round of fighting, including in Gaza, has reaffirmed the centrality of Jerusalem in the conflict. The evolving situation in East Jerusalem – at the Holy Esplanade and in neighbourhoods such as Sheikh Jarrah – has come to epitomise the fundamental elements underlying the broader Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the experiences of Palestinians living through it. The latest altercations in Jerusalem brought these to a head, and found common resonance throughout Palestine’s geographically scattered communities, including in the diaspora.

With growing frequency, Palestinians in these protests raised calls for Hamas, a self-described Islamic national liberation and resistance movement, to step in and do something, clearly positioning the movement in Palestinian eyes as a bulwark against Israeli aggression in contrast with Fatah in the West Bank. At these same protests, Palestinians hurled insults at Abbas and the PA for their ineffectiveness at defending Jerusalem, particularly after they had used the city as the pretence for cancelling Palestinian legislative elections. Indeed, throughout the events that have transpired over the past month, the PA has been consistently mocked. In turn, the PA and Fatah have been relatively silent about these developments, while also cracking down on protests in the West Bank that have erupted in solidarity with Palestinians in East Jerusalem.

The novelty this time around, which will inevitably carry longer-term ramifications, was the popular agitation of Palestinians throughout Israel-Palestine, as if boundaries – and particularly the Green Line, marking the armistice line after the 1948 war and today separating Israel from the West Bank – had vanished. Protests spread from Ramle and Al-Lid to Jaffa, Haifa, Umm al-Fahm, Nazareth, Rahat, Hebron, Nablus, Tarshiha, Bethlehem, Tulkarem, Jenin and Qalandia refugee camp in a kind of non-organised pan-Palestinian movement, only to be met with police brutality. The mobilisation occurred despite decades of Israeli attempts at territorial cantonisation that had in effect cut off East Jerusalem from its West Bank hinterland, of which it is an intrinsic part, in the two and a half decades since the signing of the 1993 Oslo accords, and separated Palestinian citizens of Israel from Palestinians in the occupied territories since 1948.

The widespread nature of the fighting and unrest means that a single ceasefire is not going to restore calm, even if it may take the edge off the worst of the violence.

What are leaders on all sides saying?

In the wake of the 23 March Israeli elections, from which a new coalition government has yet to emerge, Israeli politicians are taking hawkish stances. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defence Minister Benny Gantz, as well as their major opponents, Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett, have all said they want to deal a major blow to Hamas. On 11 May, Netanyahu declared , “Hamas and Islamic Jihad have paid and – I tell you here – will pay a very heavy price for their aggression. I say here this evening – their blood is on their heads”.

Gantz warned on 12 May that, “Israel is not preparing for a ceasefire. There is currently no end date for the operation. Only when we achieve complete quiet can we talk about calm”. Israeli military spokesperson Hidai Zilberman said on 13 May that the army has not ruled out a ground invasion: “We have a foot on the gas”. Others criticise the government for its lack of strategy regarding Gaza since Israel pulled soldiers and Jewish settlers out of the strip in 2005. Giora Eiland, a retired major-general and former head of Israel’s National Security Council, chided the leadership in comments to Crisis Group for having “kept the status quo for fifteen years. The state is evading other options. It is not even discussing other strategies. They are in default mode”.

Israel benefits from being able to conflate the Palestinian struggle for freedom with Hamas’s Islamist ideology and indiscriminate rocket fire at residential areas. It can use the latter in particular to justify responding with even greater force, highlighting the severe power imbalance between the two sides, and dodging responsibility for its own attacks taking civilian lives by claiming that Hamas, a designated “terrorist” organisation, is using Gaza residents as “human shields” for its military facilities.

Israeli commentators and military analysts have started assembling a victory narrative, talking about how heavy a hit Hamas has taken, giving the appearance that the war may wind down within a matter of days. Meanwhile, on the domestic front, Bennett has called off efforts to form an alternative coalition with Lapid, saying he will go back to negotiating with Netanyahu to form a government. Alternatively, Israel would go to yet another election. In either case, Netanyahu would succeed, for now, in his effort to stay in power.

Hamas has issued a list of demands, all of which, unlike in past escalations, have centred on Jerusalem. It has made clear that it will not consider a ceasefire until Israel ceases its expulsions in Sheikh Jarrah, and evacuates its forces from Al-Aqsa mosque, allowing for freedom of access to and worship at the mosque. Beyond these two central demands, Hamas has also called for the release of all prisoners detained in these recent events and Israeli acquiescence to Palestinian legislative elections including in East Jerusalem. Unlike in previous Gaza wars, Hamas has deliberately sidelined the issue of Gaza and centred its demands solely on Jerusalem in a clear demonstration of its intent to represent itself as the defender of all Palestinians across Palestine’s divided terrain.

Hamas is unlikely to see its demands regarding Jerusalem fulfilled – no Israeli government can afford to make concessions in that respect. In Gaza, the Islamist movement will have to consider how much destruction it can allow, given that the task of rebuilding will fall on its shoulders. Its endgame remains unclear.

The PA has been largely silent, offering little more than soundbites condemning Israeli violence against Palestinians in Jerusalem and Gaza. Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh criticised the UN Security Council for failing to produce a joint statement on the situation in a 13 May tweet – but PA officials have said little else of note.

Other Middle Eastern countries have deplored the turn of events but likely to little avail. The Arab League issued a statement on 11 May, condemning Israeli airstrikes on Gaza as “ indiscriminate and irresponsible ”, and stating that Israel had provoked the escalation with its actions in Jerusalem. Egypt declared its “total rejection and condemnation of these oppressive Israeli practices” in Jerusalem, and Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry said Cairo had reached out to Israel in an attempt to calm tensions but was met with indifference . Jordan was slow to react, but issued statements supporting the Palestinians in East Jerusalem and decrying Israel’s heavy-handed retaliation . Turkey has expressed similar sentiments.

Wider international reaction has likewise been muted, at least at the government level, reflecting a deep malaise in diplomacy regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict. The UN Security Council has failed repeatedly to issue a statement calling for calm, due to U.S. opposition. The U.S. also blocked the Council from holding a public session on the crisis on 14 May, though it has agreed that this meeting can take place on 16 May. As on many past occasions when it has blocked UN action on this file, the U.S. said the world body’s intercession would unduly complicate its own behind-the-scenes efforts. This position, which echoes the stances of previous administrations, leaves Washington isolated diplomatically. Moreover, blocking statements and debate on Gaza at the Security Council will benefit China (which has been working on draft Council statements on the crisis with Tunisia and Norway) and Russia, which can use it whenever the U.S. raises matters such as Syria or Xinjiang for discussion and a vote.

The Biden administration entered office hoping not to spend significant time or political capital on the Israel-Palestine conflict and, to date, it has shown no sign of getting more involved. In public, U.S. spokespersons have stuck to the line uniting Democratic and Republican administrations during flare-ups in Israel-Palestine in the post-Oslo era, calling on “both sides” to de-escalate while affirming Israel’s “right to defend itself”. Top officials, including President Joe Biden himself, but also National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and Secretary of State Tony Blinken, have placed calls to their Israeli counterparts, reportedly to counsel restraint, but as is often the case, it is not clear what message is received. Biden said Netanyahu had told him that Israel would conclude military operations “sooner rather than later”; the Israeli readout of this conversation said the prime minister told Biden that strikes on Gaza would proceed. Biden has sent a special envoy, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Hady Amr, to the region but without a clear mandate.

Without a U.S. lead, European states are unlikely to take dramatic steps of their own. The European Union, along with France, Poland and Sweden, issued statements emphasising both sides’ responsibility to restore quiet. Representatives of other countries, including Germany and the Netherlands, have denounced the rocket attacks by Hamas but refrained from critical comment about Israel’s actions. Russia, for its part, suggested reconvening the Quartet – the U.S., the UN, the EU and itself – to discuss what can be done. The Quartet’s past interventions, however, have been largely ineffectual.

What will happen next, and what should happen for things to calm down?

Hamas issued its demands when it first launched rockets at Israel over the Jerusalem crisis. Yet it is unclear what it could hope to achieve beyond a ceasefire and a return to the political status quo ante, at which point it will face huge physical devastation in Gaza, especially to its own facilities and capabilities, and to some extent also to its military capacity and command structure. The Israeli military claims it has killed at least 100 Hamas fighters, including commanders, so far, as well as its military research and development team. It posits that these losses, along with the fact that Hamas has used most of the rockets in its arsenal, will force the group to pursue a ceasefire – at which point Israel would need to decide what to do next.

Outside powers could help in laying the ground for a ceasefire. Turkey and Qatar enjoy proximity to Hamas, but Egypt, because of its longstanding interest in what happens on its northern border, is particularly well suited for this task. When the last major Israel-Gaza war happened in 2014, Cairo’s rulers were new in their seats, fresh off the 2013 coup deposing President Muhammad Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood member. They were in no rush to press for a ceasefire, seemingly content to let Morsi’s ideological confreres in Gaza take a beating. Since then, Cairo’s rulers have become more pragmatic, in part because of the Abraham Accords, which threaten their privileged status as Israel’s main partner in the Arab world. They have pressed for a ceasefire since fighting broke out, in an effort to divert attention from their internal challenges and demonstrate their relevance and diplomatic worth, especially to a new administration in Washington. But with Hamas focused on Jerusalem, and Israel bent on crushing Hamas, their effort so far has come to naught. At the moment, Cairo can give neither side what it most wants.

While the UN and Europeans, too, can play useful roles, today only the U.S., Israel’s primary backer, is able to make a real difference in Israel’s calculations. So far, the Biden administration seems content to follow Israel’s lead. Israel will want to be able to claim to its public that it has exacted the right price for Hamas’ rocket barrage – that it has, in the words of its security establishment, “restored deterrence”. With the Security Council meeting on 16 May, however, the White House’s diplomatic considerations might change. So, too, might its domestic considerations. The longer the fighting in Israel-Palestine goes on, the greater the risk of spillover into U.S. domestic politics and disruption of Biden’s agenda. Already, the crisis has started to bleed into Congressional debates.

There is another variable at play in this escalation that has not been there before: the violence between Palestinians and Israelis on the streets of Israel itself. Whether a ceasefire with Gaza would end all this violence is unclear. But continuing the bombardment of the coastal strip likely will keep feeding the country’s internal convulsions. Israel must make a choice: seek a quicker ceasefire than it otherwise might like or see a quicker unravelling of its social fabric.

This new situation gives Hamas new leverage, but it also confronts the movement with a new quandary. Does it continue to press for substantial Israeli concessions in Jerusalem, which are difficult to imagine, or does it consider the sort of deal that in its past wars was unachievable but today might be more plausible and within Cairo’s ability or even Israel’s willingness to deliver, such as a more substantial relaxation of the blockade? Today, Hamas says such a step-back is off the table – that it has its sights set on Jerusalem and has rockets sufficient for a two-month war. But as time drags on, its arsenal is depleted, Gaza’s destruction mounts and, most importantly, the Palestinian death toll climbs, it might wish that it had looked for the deal that it had been unable to achieve in four previous wars.

As for Israel’s choice, if it wishes to prevent a slide into deeper civil strife, Israel should end categorical limitations on Palestinian access to the Holy Esplanade, and remove its soldiers from the compound in all but the direst circumstances, while Muslim religious authorities (the Waqf) should control stone throwing and other violent protest activities there. Israel also should immediately call a halt to evictions of families in East Jerusalem, or at least communicate privately to Egypt and other parties that it will indefinitely postpone any further action.

More broadly, Israel should denounce violence and incendiary hate speech, no matter the source, and mete out impartial justice to all. Israeli officials have a particular responsibility to combat ethnic hatred emanating from the Jewish far right and to make sure Palestinian citizens are protected from both police and civilian violence in the same way that Jewish citizens are. Palestinians leaders in Israel have a parallel obligation within their own communities. Many around the globe, and especially in the U.S. and Europe, have been surprised by the images of Jewish mob violence, but the sentiments they embody did not spring up overnight. They have long been cultivated and endorsed at the highest levels of the state. Tamping down ethnic incitement is a matter of self-preservation for the Jewish majority, because the alternative, a steady escalation of civil strife, is already on the horizon.

Related Tags

More for you, global leaders support new israeli-palestinian peace initiatives, explaining the relative calm at jerusalem’s holy esplanade during passover, subscribe to crisis group’s email updates.

Receive the best source of conflict analysis right in your inbox.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Review our privacy policy for more details.

Settlements and the Israel-Palestine Conflict: Background Reading

Scholarship about Israeli settlement in occupied Palestinian territories provides historical context for recent violence in the region.

After a relatively dormant period, the Israel-Palestine conflict erupted into open war in May of 2021. Hamas in Gaza and the Israeli army engaged in the first sustained exchange of rocket fire and airstrikes in seven years. The near-term cause of the fighting was a series of disputes over the usage of the Al-Aqsa Mosque and nearby Wailing Wall in Jerusalem , as Israel’s national holidays conflicted with the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Moreover, both the governments of Israel and the Palestinian Authority are weak in 2021, discouraging either side from compromise. At that time, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu failed to attract the necessary cohort of far-right wing politicians to form a coalition government in Israel’s parliamentary system. The President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, canceled elections to avoid a potential loss. This emboldened Hamas, which broke with Abbas’ party Fatah in 2007 and has remained in sole control of Gaza since that time.

Audio brought to you by curio.io

However, the most important long-term factor has been the continuing Israeli efforts to displace Palestinian residents of the occupied Palestine territories and to settle Israeli citizens in their place. Israel occupied the Palestinian territories of Gaza and the West Bank in the 1967 war, which had been formerly under the administration of Egypt and Jordan, respectively. Israel has permitted hundreds of thousands of settlers to make land claims based on pre-1948 ownership in these territories, and to establish entirely new communities on land claimed by the state in the intervening decade. The UN has formally denounced this policy as a violation of international law.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

This long process also arrived at a significant turning point in early 2021, as Israel courts ordered several Palestinian families to vacate their Sheikh Jarrah homes, where many had lived for decades. Those official decrees to remove Palestinian families from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem near Al-Aqsa triggered Palestinian street protests and violent clashes involving Israeli police by May of 2021.

The following research available for free via the links below offers valuable insight and historical context on the topic of the Israeli settlements.

Joel Beinin, “Mixing, Separation and Violence in Urban Spaces and The Rural Frontier in Palestine,” The Arab Studies Journal , Spring 2013, Vol. 21, No. 1, TWENTIETH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE, pp. 14-47.

Beinin situates the phenomenon of the Israeli settlements in historical context. In the era of Ottoman Palestine and even the British mandate that followed World War I, Christian, Muslim and Jewish communities lived side-by-side in Palestine’s major cities Jerusalem and Jaffa. They socialized together and invested in each other’s business ventures as the Levant entered the industrial world. Although many early Zionist settlers, and the later Labor Zionist movement, idealized rural settlement and agriculture as the principal way of creating a Jewish homeland community, Beinin demonstrates that it was largely cities that Zionist immigrants moved to and sought to transform, both before and after the formation of Israel in 1948 and the 1967 war.

“Despite its preponderantly urban character, the post-1967 settlement project has produced a diametrically opposite model of urban life than the norms of late Ottoman Palestine—in practice and as the settlers’ ideal,” Beinin writes. “Jews exclusively inhabit all settlements—urban, suburban, or rural, ideologically or economically inspired—though Palestinians are often employed in them, even to construct them. All Jews are Israeli citizens with greater rights and subject to different laws and norms than their non-citizen neighbors.”

Janet Abu-Lughod, “Israeli Settlements in Occupied Arab Lands: Conquest to Colony,” Journal of Palestine Studies , Winter 1982, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 16-54.

Written only 15 years after the 1967 war, Abu-Lughod’s research provides valuable insight into Israel’s initial government and settlement strategies of the Palestinian territories. Although some right-wing politicians made immediate demands to annex Gaza and the West Bank, in spite of international law, most Israeli leaders realized that this would raise the question of giving citizenship to Palestinians. They then sought other means of legally expropriating land and diminishing the power of occupied Palestinians.

Indeed, Abu-Lughod argues Israel drew on the experience of urban planning inside Israel between 1948 and 1967 to diminish the concentration of Arab Israeli citizens in certain parts of the country when planning the distribution of occupied territory settlements. The justification for taking possession of this land comes “from the fiction of government succession.” The legal practice of freehold private property developed later in the Muslim world than in Europe, and much of the marginal land in the West Bank remained unregistered or in religious foundations (waqfs), which Israel claimed as state land after 1967. “While the confiscation and reassignment of ‘state land’ to Jewish settlers is inherently no more legitimate than any other form of expropriation, the Israelis have made much of this distinction between public and private ownership in their defensive arguments,” she writes.

Marina Sergides, “Housing in East Jerusalem: Marina Sergides reports on a legal mission to the Occupied Palestine Territory,” Socialist Lawyer , No. 60 (February 2012), pp. 14-17.

This is a deep dive into the social and legal situations of the Palestinian families in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem living on land with disputed ownership. Twenty-eight refugee families with 500 people had been living in homes they had built on land granted to them by UNRWH after fleeing from other homes inside Israel after its creation in 1948. Since 1967 and the Israeli declared annexation of East Jerusalem, the Nahalat Shimon company has brought Ottoman-era documents claiming some of the land in the neighborhood had been owned by Jewish families in the 19th century. It succeeded in forcing out four of the families in 2009.

Sergides questions of the legal proceedings of applying domestic Israeli law to Palestinians in territory recognized as occupied under international law. “Moreover, the delegation observed that there is an asymmetry in the way the Israeli courts treat the question of pre-1948 property rights,” she writes. “While the courts have been willing to uphold claims by Jewish organisations in relation to property in Sheikh Jarrah allegedly owned by Jewish families before 1948, similar claims by the Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah in relation to lands which their families owned in what is now the State of Israel would not be entertained.” She concludes by highlighting the ways Israeli demolitions of Palestinian homes and restriction on new construction is causing a housing crisis in East Jerusalem.

Raja Shehadeh, “From Jerusalem to the Rest of the West Bank,” Review of Middle East Studies , June 2019, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 6-19.

The most recent installment on this list, Shehadeh reviews the politics of settlement in recent decades in light of the Trump administration’s decision to move the US Embassy to Jerusalem, recognizing it as Israel’s capital on Dec. 6, 2017. In particular, he highlights the failures of the two-state solution to reconcile the existence of settlements within Palestinian territory, an inherent flaw in the 1990s’ Oslo Peace Accords.

The Accords divided land in the West Bank into three areas: A) Palestinian control; B) Palestinian civil control with Israeli military control and C) Full Israeli control. The resulting map is a Swiss cheese of administrative areas. Combined with Israel’s direct annexation of East Jerusalem, it divided Palestinian settlement into a patchwork difficult to govern. Although the PLO made these compromises to win recognition from Israel, the resulting devolution of political power only heightened the distinction between settlers, who enjoy citizenship rights and state services, and the disenfranchisement of Palestinians.

Joyce Dalsheim and Assaf Harel, “Representing Settlers,” Review of Middle East Studies , Winter 2009, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Winter 2009), pp. 219-238.

This review essay is a cultural critique of the way religious Israeli settlers are conceived in the news media and academic works. Works in both fields, Dalsheim and Harel write, depict these Israeli settlers as religious fundamentalists that are seeking both to create socially alienated communities and to fulfill a religious commitment to reclaim what they see as land promised them in the bible, despite international law. However much this reflects the truth for some communities, they argue it does not reflect the huge diversity of people actually settling in the occupied territories. Moreover, it serves as symbolic legitimization of other brands of Zionism.

“These representations of settlers not only portray religious settlers as categorically different from ‘ordinary’ or ‘mainstream’ Israelis, they also project a sense of moral legitimacy for those writing against the settlers,” Dalsheim and Harel argue. “They reaffirm a moral high ground for Israelis by inscribing a deep division between Israel inside its internationally recognized borders and its settlements in the post-1967 occupied territories.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Archaeology of the October Cuban Crisis

All The Way With LBJ?

The Death of Jack Trice

Staying Cool: Helpful Hints From History

Recent posts.

- Meteorites from Mars

- From Folkway to Art: The Transformation of Quilts

- The “Soundscape” Heard ’Round the World

- Olympic Tech, Emotional Dogs, and Atlantic Currents

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- World Politics

9 questions about the Israel-Palestine conflict you were too embarrassed to ask

by Max Fisher

Editor’s note, October 9, 2023: This story was last updated on July 17, 2014, and some information in it may no longer be accurate. For all of Vox’s latest coverage on Israel and Palestine, see our storystream .

Everyone has heard of the Israel-Palestine conflict . Everyone knows it’s bad, that it’s been going on for a long time, and that there is a lot of hatred on both sides.

But you may find yourself less clear on the hows and the whys of the conflict. Why, for example, did Israel invade the Palestinian territory of Gaza in July 2014, leading to the deaths of hundreds of Palestinian civilians, many of them children? Why did the militant Palestinian group Hamas fire rockets into civilian neighborhoods in Israel? How did this latest round of violence start in the first place — and why do they hate one another at all?

What follows are the most basic answers to your most basic questions. Giant, neon-lit disclaimer: these issues are complicated and contentious, and this is not an exhaustive or definitive account of Israel-Palestine’s history or the conflict today. But it’s a place to start.

1) What are Israel and Palestine?

That sounds like a very basic question but, in a sense, it’s at the center of the conflict.

Israel is an officially Jewish country located in the Middle East. Palestine is a set of two physically separate, ethnically Arab and mostly Muslim territories alongside Israel: the West Bank, named for the western shore of the Jordan River, and Gaza. Those territories are not independent (more on this later). All together, Israel and the Palestinian territories are about as populous as Illinois and about half its size.

Officially, there is no internationally recognized line between Israel and Palestine; the borders are considered to be disputed, and have been for decades. So is the status of Palestine: some countries consider Palestine to be an independent state, while others (like the US) consider Palestine to be territories under Israeli occupation. Both Israelis and Palestinians have claims to the land going back centuries, but the present-day states are relatively new.

2) Why are Israelis and Palestinians fighting?

Israeli soldiers clash with Palestinian stone throwers at a checkpoint outside Jerusalem (AHMAD GHARABLI/AFP/Getty Images)

This is not, despite what you may have heard, primarily about religion. On the surface at least, it’s very simple: the conflict is over who gets what land and how it is controlled. In execution, though, that gets into a lot of really thorny issues, like: Where are the borders? Can Palestinian refugees return to their former homes in present-day Israel? More on these later.

The decades-long process of resolving that conflict has created another, overlapping conflict: managing the very unpleasant Israeli-Palestinian coexistence, in which Israel has put the Palestinians under suffocating military occupation and Palestinian militant groups terrorize Israelis.

Both sides have squandered peace and perpetuated conflict, but palestinians today bear most of the suffering

Those two dimensions of the conflict are made even worse by the long, bitter, violent history between these two peoples. It’s not just that there is lots of resentment and distrust; Israelis and Palestinians have such widely divergent narratives of the last 70-plus years, of what has happened and why, that even reconciling their two realities is extremely difficult. All of this makes it easier for extremists, who oppose any compromise and want to destroy or subjugate the other side entirely, to control the conversation and derail the peace process.

The peace process, by the way, has been going on for decades, but it hasn’t looked at all hopeful since the breakthrough 1993 and 1995 Oslo Accords produced a glimmer of hope that has since dissipated. The conflict has settled into a terrible cycle and peace looks less possible all the time.

Something you often hear is that “both sides” are to blame for perpetuating the conflict, and there’s plenty of truth to that. There has always been and remains plenty of culpability to go around, plenty of individuals and groups on both sides that squandered peace and perpetuated conflict many times over. Still, perhaps the most essential truth of the Israel-Palestine conflict today is that the conflict predominantly matters for the human suffering it causes. And while Israelis certainly suffer deeply and in great numbers, the vast majority of the conflict’s toll is incurred by Palestinian civilians . Just above, as one metric of that , are the Israeli and Palestinian conflict-related deaths every month since late 2000.

3) How did this conflict start in the first place?

(Left map: Passia ; center and right maps: Philippe Rekacewicz / Le Monde Diplomatique )

The conflict has been going on since the early 1900s, when the mostly-Arab, mostly-Muslim region was part of the Ottoman Empire and, starting in 1917, a "mandate" run by the British Empire. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were moving into the area, as part of a movement called Zionism among mostly European Jews to escape persecution and establish their own state in their ancestral homeland. (Later, large numbers of Middle Eastern Jews also moved to Israel, either to escape anti-Semitic violence or because they were forcibly expelled.)

Communal violence between Jews and Arabs in British Palestine began spiraling out of control. In 1947, the United Nations approved a plan to divide British Palestine into two mostly independent countries, one for Jews called Israel and one for Arabs called Palestine. Jerusalem, holy city for Jews and Muslims, was to be a special international zone.

The plan was never implemented. Arab leaders in the region saw it as European colonial theft and, in 1948, invaded to keep Palestine unified. The Israeli forces won the 1948 war, but they pushed well beyond the UN-designated borders to claim land that was to have been part of Palestine, including the western half of Jerusalem. They also uprooted and expelled entire Palestinian communities, creating about 700,000 refugees, whose descendants now number 7 million and are still considered refugees.

The 1948 war ended with Israel roughly controlling the territory that you will see marked on today’s maps as “Israel”; everything except for the West Bank and Gaza, which is where most Palestinian fled to (many also ended up in refugee camps in neighboring countries) and are today considered the Palestinian territories. The borders between Israel and Palestine have been disputed and fought over ever since. So has the status of those Palestinian refugees and the status of Jerusalem.

That’s the first major dimension of the conflict: reconciling the division that opened in 1948. The second began in 1967, when Israel put those two Palestinian territories under military occupation.

4) Why is Israel occupying the Palestinian territories?

A Palestinian boy next to the Israeli wall around the town of Qalqilya (David Silverman/Getty Images)

This is a hugely important part of the conflict today, especially for Palestinians.

Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza began in 1967. Up to that point, Gaza had been (more or less) controlled by Egypt and the West Bank by Jordan. But in 1967 there was another war between Israel and its Arab neighbors, during which Israel occupied the two Palestinian territories. (Israel also took control of Syria’s Golan Heights, which it annexed in 1981, and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, which it returned to Egypt in 1982.)

Israeli forces have occupied and controlled the West Bank ever since. It withdrew its occupying troops and settlers from Gaza in 2005, but maintains a full blockade of the territory, which has turned Gaza into what human rights organizations sometimes call an “open-air prison” and has pushed the unemployment rate up to 40 percent .

Israel says the occupation is necessary for security given its tiny size: to protect Israelis from Palestinian attacks and to provide a buffer from foreign invasions. But that does not explain the settlers.

Settlers are Israelis who move into the West Bank. They are widely considered to violate international law, which forbids an occupying force from moving its citizens into occupied territory. Many of the 500,000 settlers are just looking for cheap housing; most live within a few miles of the Israeli border, often in the around surrounding Jerusalem.

Others move deep into the West Bank to claim land for Jews, out of religious fervor and/or a desire to see more or all of the West Bank absorbed into Israel. While Israel officially forbids this and often evicts these settlers, many are still able to take root.

In the short term, settlers of all forms make life for Palestinians even more difficult, by forcing the Israeli government to guard them with walls or soldiers that further constrain Palestinians. In the long term, the settlers create what are sometimes called “facts on the ground”: Israeli communities that blur the borders and expand land that Israel could claim for itself in any eventual peace deal.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank is all-consuming for the Palestinians who live there, constrained by Israeli checkpoints and 20-foot walls, subject to an Israeli military justice system in which on average two children are arrested every day , stuck with an economy stifled by strict Israeli border control, and countless other indignities large and small.

5) Can we take a quick music break?