How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

| Summarizing Conclusion | Impact of social media on adolescents’ mental health | In conclusion, our study has shown that increased usage of social media is significantly associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression among adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the complex relationship between social media and mental health to develop effective interventions and support systems for this vulnerable population. |

| Editorial Conclusion | Environmental impact of plastic waste | In light of our research findings, it is clear that we are facing a plastic pollution crisis. To mitigate this issue, we strongly recommend a comprehensive ban on single-use plastics, increased recycling initiatives, and public awareness campaigns to change consumer behavior. The responsibility falls on governments, businesses, and individuals to take immediate actions to protect our planet and future generations. |

| Externalizing Conclusion | Exploring applications of AI in healthcare | While our study has provided insights into the current applications of AI in healthcare, the field is rapidly evolving. Future research should delve deeper into the ethical, legal, and social implications of AI in healthcare, as well as the long-term outcomes of AI-driven diagnostics and treatments. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, medical professionals, and policymakers is essential to harness the full potential of AI while addressing its challenges. |

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, how to cite in apa format (7th edition):..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

An APA-style research report begins with a title page . The title is centred in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behaviour?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal Psychological Science .

- “Smells Like Clean Spirit: Nonconscious Effects of Scent on Cognition and Behavior”

- “Time Crawls: The Temporal Resolution of Infants’ Visual Attention”

- “Scent of a Woman: Men’s Testosterone Responses to Olfactory Ovulation Cues”

- “Apocalypse Soon?: Dire Messages Reduce Belief in Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs”

- “Serial vs. Parallel Processing: Sometimes They Look Like Tweedledum and Tweedledee but They Can (and Should) Be Distinguished”

- “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words: The Social Effects of Expressive Writing”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

The abstract is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behaviour (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003 [1] ). Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humourous anecdote:

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (Jacoby, 1999, p. 3)

Although both humour and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favourite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) [2] concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behaviour during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions. (p. 378)

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centred on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

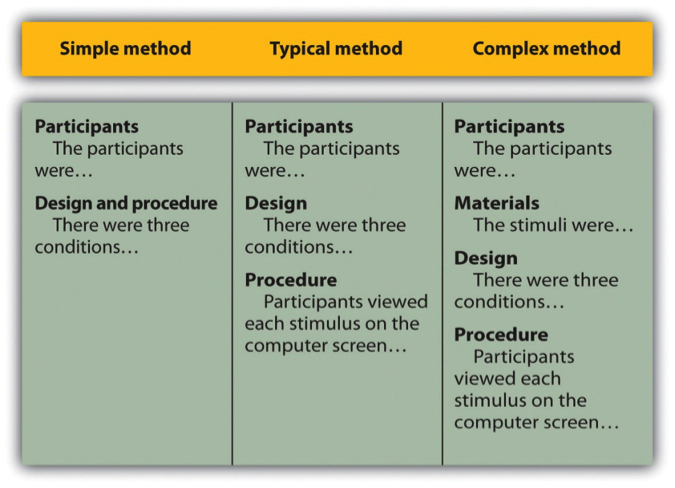

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Several journals now encourage the open sharing of raw data online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) [3] suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.

The discussion is the last major section of the research report. Discussions usually consist of some combination of the following elements:

- Summary of the research

- Theoretical implications

- Practical implications

- Limitations

- Suggestions for future research

The discussion typically begins with a summary of the study that provides a clear answer to the research question. In a short report with a single study, this might require no more than a sentence. In a longer report with multiple studies, it might require a paragraph or even two. The summary is often followed by a discussion of the theoretical implications of the research. Do the results provide support for any existing theories? If not, how can they be explained? Although you do not have to provide a definitive explanation or detailed theory for your results, you at least need to outline one or more possible explanations. In applied research—and often in basic research—there is also some discussion of the practical implications of the research. How can the results be used, and by whom, to accomplish some real-world goal?

The theoretical and practical implications are often followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. Perhaps there are problems with its internal or external validity. Perhaps the manipulation was not very effective or the measures not very reliable. Perhaps there is some evidence that participants did not fully understand their task or that they were suspicious of the intent of the researchers. Now is the time to discuss these issues and how they might have affected the results. But do not overdo it. All studies have limitations, and most readers will understand that a different sample or different measures might have produced different results. Unless there is good reason to think they would have, however, there is no reason to mention these routine issues. Instead, pick two or three limitations that seem like they could have influenced the results, explain how they could have influenced the results, and suggest ways to deal with them.

Most discussions end with some suggestions for future research. If the study did not satisfactorily answer the original research question, what will it take to do so? What new research questions has the study raised? This part of the discussion, however, is not just a list of new questions. It is a discussion of two or three of the most important unresolved issues. This means identifying and clarifying each question, suggesting some alternative answers, and even suggesting ways they could be studied.

Finally, some researchers are quite good at ending their articles with a sweeping or thought-provoking conclusion. Darley and Latané (1968) [4] , for example, ended their article on the bystander effect by discussing the idea that whether people help others may depend more on the situation than on their personalities. Their final sentence is, “If people understand the situational forces that can make them hesitate to intervene, they may better overcome them” (p. 383). However, this kind of ending can be difficult to pull off. It can sound overreaching or just banal and end up detracting from the overall impact of the article. It is often better simply to end when you have made your final point (although you should avoid ending on a limitation).

The references section begins on a new page with the heading “References” centred at the top of the page. All references cited in the text are then listed in the format presented earlier. They are listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. If two sources have the same first author, they are listed alphabetically by the last name of the second author. If all the authors are the same, then they are listed chronologically by the year of publication. Everything in the reference list is double-spaced both within and between references.

Appendices, Tables, and Figures

Appendices, tables, and figures come after the references. An appendix is appropriate for supplemental material that would interrupt the flow of the research report if it were presented within any of the major sections. An appendix could be used to present lists of stimulus words, questionnaire items, detailed descriptions of special equipment or unusual statistical analyses, or references to the studies that are included in a meta-analysis. Each appendix begins on a new page. If there is only one, the heading is “Appendix,” centred at the top of the page. If there is more than one, the headings are “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on, and they appear in the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

After any appendices come tables and then figures. Tables and figures are both used to present results. Figures can also be used to illustrate theories (e.g., in the form of a flowchart), display stimuli, outline procedures, and present many other kinds of information. Each table and figure appears on its own page. Tables are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in the text (“Table 1,” “Table 2,” and so on). Figures are numbered the same way (“Figure 1,” “Figure 2,” and so on). A brief explanatory title, with the important words capitalized, appears above each table. Each figure is given a brief explanatory caption, where (aside from proper nouns or names) only the first word of each sentence is capitalized. More details on preparing APA-style tables and figures are presented later in the book.

Sample APA-Style Research Report

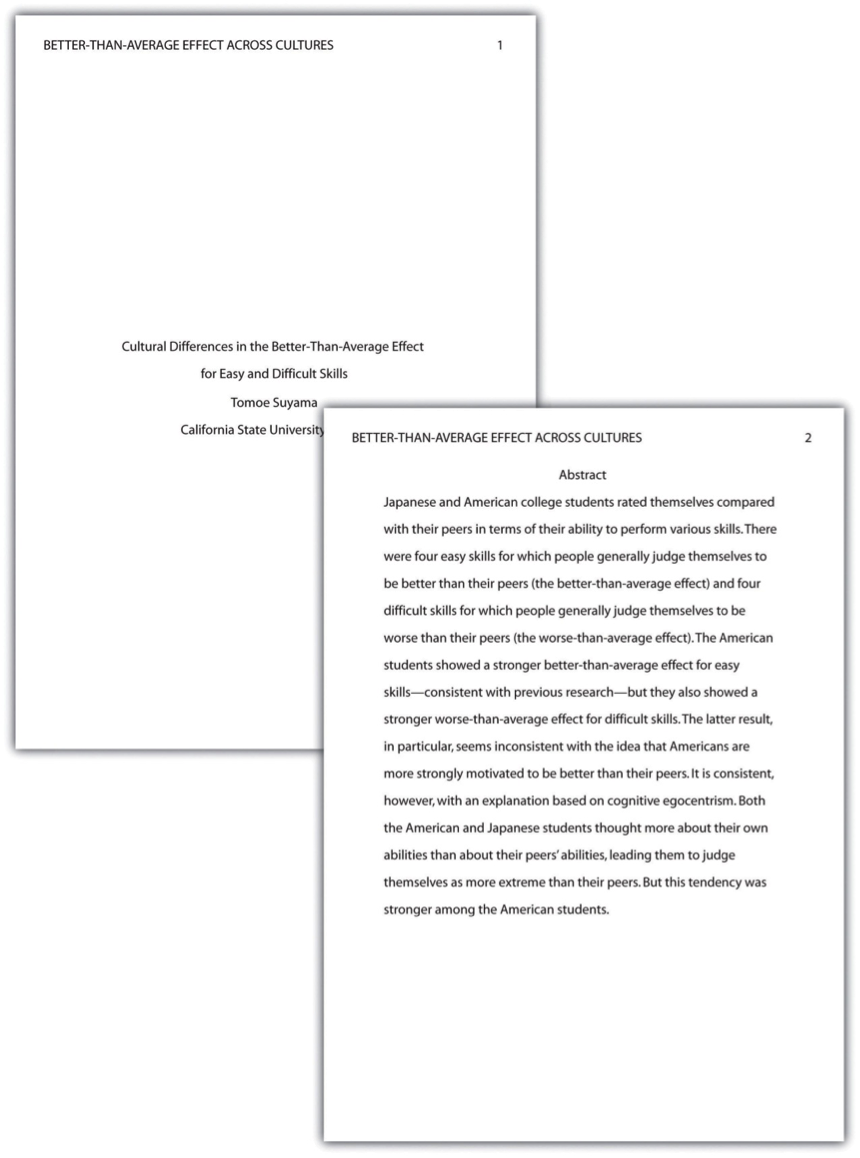

Figures 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, and 11.5 show some sample pages from an APA-style empirical research report originally written by undergraduate student Tomoe Suyama at California State University, Fresno. The main purpose of these figures is to illustrate the basic organization and formatting of an APA-style empirical research report, although many high-level and low-level style conventions can be seen here too.

Key Takeaways

- An APA-style empirical research report consists of several standard sections. The main ones are the abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, and references.

- The introduction consists of an opening that presents the research question, a literature review that describes previous research on the topic, and a closing that restates the research question and comments on the method. The literature review constitutes an argument for why the current study is worth doing.

- The method section describes the method in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. At a minimum, it consists of a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsection.

- The results section describes the results in an organized fashion. Each primary result is presented in terms of statistical results but also explained in words.

- The discussion typically summarizes the study, discusses theoretical and practical implications and limitations of the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

- Practice: Look through an issue of a general interest professional journal (e.g., Psychological Science ). Read the opening of the first five articles and rate the effectiveness of each one from 1 ( very ineffective ) to 5 ( very effective ). Write a sentence or two explaining each rating.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and identify where the opening, literature review, and closing of the introduction begin and end.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and highlight in a different colour each of the following elements in the discussion: summary, theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.1 long description: Table showing three ways of organizing an APA-style method section.

In the simple method, there are two subheadings: “Participants” (which might begin “The participants were…”) and “Design and procedure” (which might begin “There were three conditions…”).

In the typical method, there are three subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”).

In the complex method, there are four subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Materials” (“The stimuli were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”). [Return to Figure 11.1]

- Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. ↵

A type of research article which describes one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

The page at the beginning of an APA-style research report containing the title of the article, the authors’ names, and their institutional affiliation.

A summary of a research study.

The third page of a manuscript containing the research question, the literature review, and comments about how to answer the research question.

An introduction to the research question and explanation for why this question is interesting.

A description of relevant previous research on the topic being discusses and an argument for why the research is worth addressing.

The end of the introduction, where the research question is reiterated and the method is commented upon.

The section of a research report where the method used to conduct the study is described.

The main results of the study, including the results from statistical analyses, are presented in a research article.

Section of a research report that summarizes the study's results and interprets them by referring back to the study's theoretical background.

Part of a research report which contains supplemental material.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on October 30, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on April 13, 2023.

- Restate the problem statement addressed in the paper

- Summarize your overall arguments or findings

- Suggest the key takeaways from your paper

The content of the conclusion varies depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument through engagement with sources .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: restate the problem, step 2: sum up the paper, step 3: discuss the implications, research paper conclusion examples, frequently asked questions about research paper conclusions.

The first task of your conclusion is to remind the reader of your research problem . You will have discussed this problem in depth throughout the body, but now the point is to zoom back out from the details to the bigger picture.

While you are restating a problem you’ve already introduced, you should avoid phrasing it identically to how it appeared in the introduction . Ideally, you’ll find a novel way to circle back to the problem from the more detailed ideas discussed in the body.

For example, an argumentative paper advocating new measures to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture might restate its problem as follows:

Meanwhile, an empirical paper studying the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues might present its problem like this:

“In conclusion …”

Avoid starting your conclusion with phrases like “In conclusion” or “To conclude,” as this can come across as too obvious and make your writing seem unsophisticated. The content and placement of your conclusion should make its function clear without the need for additional signposting.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Having zoomed back in on the problem, it’s time to summarize how the body of the paper went about addressing it, and what conclusions this approach led to.

Depending on the nature of your research paper, this might mean restating your thesis and arguments, or summarizing your overall findings.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

In an argumentative paper, you will have presented a thesis statement in your introduction, expressing the overall claim your paper argues for. In the conclusion, you should restate the thesis and show how it has been developed through the body of the paper.

Briefly summarize the key arguments made in the body, showing how each of them contributes to proving your thesis. You may also mention any counterarguments you addressed, emphasizing why your thesis holds up against them, particularly if your argument is a controversial one.

Don’t go into the details of your evidence or present new ideas; focus on outlining in broad strokes the argument you have made.

Empirical paper: Summarize your findings

In an empirical paper, this is the time to summarize your key findings. Don’t go into great detail here (you will have presented your in-depth results and discussion already), but do clearly express the answers to the research questions you investigated.

Describe your main findings, even if they weren’t necessarily the ones you expected or hoped for, and explain the overall conclusion they led you to.

Having summed up your key arguments or findings, the conclusion ends by considering the broader implications of your research. This means expressing the key takeaways, practical or theoretical, from your paper—often in the form of a call for action or suggestions for future research.

Argumentative paper: Strong closing statement

An argumentative paper generally ends with a strong closing statement. In the case of a practical argument, make a call for action: What actions do you think should be taken by the people or organizations concerned in response to your argument?

If your topic is more theoretical and unsuitable for a call for action, your closing statement should express the significance of your argument—for example, in proposing a new understanding of a topic or laying the groundwork for future research.

Empirical paper: Future research directions

In a more empirical paper, you can close by either making recommendations for practice (for example, in clinical or policy papers), or suggesting directions for future research.

Whatever the scope of your own research, there will always be room for further investigation of related topics, and you’ll often discover new questions and problems during the research process .

Finish your paper on a forward-looking note by suggesting how you or other researchers might build on this topic in the future and address any limitations of the current paper.

Full examples of research paper conclusions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

While the role of cattle in climate change is by now common knowledge, countries like the Netherlands continually fail to confront this issue with the urgency it deserves. The evidence is clear: To create a truly futureproof agricultural sector, Dutch farmers must be incentivized to transition from livestock farming to sustainable vegetable farming. As well as dramatically lowering emissions, plant-based agriculture, if approached in the right way, can produce more food with less land, providing opportunities for nature regeneration areas that will themselves contribute to climate targets. Although this approach would have economic ramifications, from a long-term perspective, it would represent a significant step towards a more sustainable and resilient national economy. Transitioning to sustainable vegetable farming will make the Netherlands greener and healthier, setting an example for other European governments. Farmers, policymakers, and consumers must focus on the future, not just on their own short-term interests, and work to implement this transition now.

As social media becomes increasingly central to young people’s everyday lives, it is important to understand how different platforms affect their developing self-conception. By testing the effect of daily Instagram use among teenage girls, this study established that highly visual social media does indeed have a significant effect on body image concerns, with a strong correlation between the amount of time spent on the platform and participants’ self-reported dissatisfaction with their appearance. However, the strength of this effect was moderated by pre-test self-esteem ratings: Participants with higher self-esteem were less likely to experience an increase in body image concerns after using Instagram. This suggests that, while Instagram does impact body image, it is also important to consider the wider social and psychological context in which this usage occurs: Teenagers who are already predisposed to self-esteem issues may be at greater risk of experiencing negative effects. Future research into Instagram and other highly visual social media should focus on establishing a clearer picture of how self-esteem and related constructs influence young people’s experiences of these platforms. Furthermore, while this experiment measured Instagram usage in terms of time spent on the platform, observational studies are required to gain more insight into different patterns of usage—to investigate, for instance, whether active posting is associated with different effects than passive consumption of social media content.

If you’re unsure about the conclusion, it can be helpful to ask a friend or fellow student to read your conclusion and summarize the main takeaways.

- Do they understand from your conclusion what your research was about?

- Are they able to summarize the implications of your findings?

- Can they answer your research question based on your conclusion?

You can also get an expert to proofread and feedback your paper with a paper editing service .

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

The conclusion of a research paper has several key elements you should make sure to include:

- A restatement of the research problem

- A summary of your key arguments and/or findings

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

No, it’s not appropriate to present new arguments or evidence in the conclusion . While you might be tempted to save a striking argument for last, research papers follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the results and discussion sections if you are following a scientific structure). The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, April 13). Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing a research paper introduction | step-by-step guide, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, checklist: writing a great research paper, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

General Research Paper Guidelines: Discussion

Discussion section.

The overall purpose of a research paper’s discussion section is to evaluate and interpret results, while explaining both the implications and limitations of your findings. Per APA (2020) guidelines, this section requires you to “examine, interpret, and qualify the results and draw inferences and conclusions from them” (p. 89). Discussion sections also require you to detail any new insights, think through areas for future research, highlight the work that still needs to be done to further your topic, and provide a clear conclusion to your research paper. In a good discussion section, you should do the following:

- Clearly connect the discussion of your results to your introduction, including your central argument, thesis, or problem statement.

- Provide readers with a critical thinking through of your results, answering the “so what?” question about each of your findings. In other words, why is this finding important?

- Detail how your research findings might address critical gaps or problems in your field

- Compare your results to similar studies’ findings

- Provide the possibility of alternative interpretations, as your goal as a researcher is to “discover” and “examine” and not to “prove” or “disprove.” Instead of trying to fit your results into your hypothesis, critically engage with alternative interpretations to your results.

For more specific details on your Discussion section, be sure to review Sections 3.8 (pp. 89-90) and 3.16 (pp. 103-104) of your 7 th edition APA manual

*Box content adapted from:

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 8 the discussion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/discussion

Limitations

Limitations of generalizability or utility of findings, often over which the researcher has no control, should be detailed in your Discussion section. Including limitations for your reader allows you to demonstrate you have thought critically about your given topic, understood relevant literature addressing your topic, and chosen the methodology most appropriate for your research. It also allows you an opportunity to suggest avenues for future research on your topic. An effective limitations section will include the following:

- Detail (a) sources of potential bias, (b) possible imprecision of measures, (c) other limitations or weaknesses of the study, including any methodological or researcher limitations.

- Sample size: In quantitative research, if a sample size is too small, it is more difficult to generalize results.

- Lack of available/reliable data : In some cases, data might not be available or reliable, which will ultimately affect the overall scope of your research. Use this as an opportunity to explain areas for future study.

- Lack of prior research on your study topic: In some cases, you might find that there is very little or no similar research on your study topic, which hinders the credibility and scope of your own research. If this is the case, use this limitation as an opportunity to call for future research. However, make sure you have done a thorough search of the available literature before making this claim.

- Flaws in measurement of data: Hindsight is 20/20, and you might realize after you have completed your research that the data tool you used actually limited the scope or results of your study in some way. Again, acknowledge the weakness and use it as an opportunity to highlight areas for future study.

- Limits of self-reported data: In your research, you are assuming that any participants will be honest and forthcoming with responses or information they provide to you. Simply acknowledging this assumption as a possible limitation is important in your research.

- Access: Most research requires that you have access to people, documents, organizations, etc.. However, for various reasons, access is sometimes limited or denied altogether. If this is the case, you will want to acknowledge access as a limitation to your research.

- Time: Choosing a research focus that is narrow enough in scope to finish in a given time period is important. If such limitations of time prevent you from certain forms of research, access, or study designs, acknowledging this time restraint is important. Acknowledging such limitations is important, as they can point other researchers to areas that require future study.

- Potential Bias: All researchers have some biases, so when reading and revising your draft, pay special attention to the possibilities for bias in your own work. Such bias could be in the form you organized people, places, participants, or events. They might also exist in the method you selected or the interpretation of your results. Acknowledging such bias is an important part of the research process.

- Language Fluency: On occasion, researchers or research participants might have language fluency issues, which could potentially hinder results or how effectively you interpret results. If this is an issue in your research, make sure to acknowledge it in your limitations section.

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: Limitations of the study . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/limitations

In many research papers, the conclusion, like the limitations section, is folded into the larger discussion section. If you are unsure whether to include the conclusion as part of your discussion or as a separate section, be sure to defer to the assignment instructions or ask your instructor.

The conclusion is important, as it is specifically designed to highlight your research’s larger importance outside of the specific results of your study. Your conclusion section allows you to reiterate the main findings of your study, highlight their importance, and point out areas for future research. Based on the scope of your paper, your conclusion could be anywhere from one to three paragraphs long. An effective conclusion section should include the following:

- Describe the possibilities for continued research on your topic, including what might be improved, adapted, or added to ensure useful and informed future research.

- Provide a detailed account of the importance of your findings

- Reiterate why your problem is important, detail how your interpretation of results impacts the subfield of study, and what larger issues both within and outside of your field might be affected from such results

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 9. the conclusion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/conclusion

- Previous Page: Results

- Next Page: References

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

How To Write The Conclusion Chapter

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | September 2021

So, you’ve wrapped up your results and discussion chapters, and you’re finally on the home stretch – the conclusion chapter . In this post, we’ll discuss everything you need to know to craft a high-quality conclusion chapter for your dissertation or thesis project.

Overview: The Conclusion Chapter

- What the thesis/dissertation conclusion chapter is

- What to include in your conclusion

- How to structure and write up your conclusion

- A few tips to help you ace the chapter

- FREE conclusion template

What is the conclusion chapter?

The conclusion chapter is typically the final major chapter of a dissertation or thesis. As such, it serves as a concluding summary of your research findings and wraps up the document. While some publications such as journal articles and research reports combine the discussion and conclusion sections, these are typically separate chapters in a dissertation or thesis. As always, be sure to check what your university’s structural preference is before you start writing up these chapters.

So, what’s the difference between the discussion and the conclusion chapter?

Well, the two chapters are quite similar , as they both discuss the key findings of the study. However, the conclusion chapter is typically more general and high-level in nature. In your discussion chapter, you’ll typically discuss the intricate details of your study, but in your conclusion chapter, you’ll take a broader perspective, reporting on the main research outcomes and how these addressed your research aim (or aims) .

A core function of the conclusion chapter is to synthesise all major points covered in your study and to tell the reader what they should take away from your work. Basically, you need to tell them what you found , why it’s valuable , how it can be applied , and what further research can be done.

Whatever you do, don’t just copy and paste what you’ve written in your discussion chapter! The conclusion chapter should not be a simple rehash of the discussion chapter. While the two chapters are similar, they have distinctly different functions.

What should I include in the conclusion chapter?

To understand what needs to go into your conclusion chapter, it’s useful to understand what the chapter needs to achieve. In general, a good dissertation conclusion chapter should achieve the following:

- Summarise the key findings of the study

- Explicitly answer the research question(s) and address the research aims

- Inform the reader of the study’s main contributions

- Discuss any limitations or weaknesses of the study

- Present recommendations for future research

Therefore, your conclusion chapter needs to cover these core components. Importantly, you need to be careful not to include any new findings or data points. Your conclusion chapter should be based purely on data and analysis findings that you’ve already presented in the earlier chapters. If there’s a new point you want to introduce, you’ll need to go back to your results and discussion chapters to weave the foundation in there.

In many cases, readers will jump from the introduction chapter directly to the conclusions chapter to get a quick overview of the study’s purpose and key findings. Therefore, when you write up your conclusion chapter, it’s useful to assume that the reader hasn’t consumed the inner chapters of your dissertation or thesis. In other words, craft your conclusion chapter such that there’s a strong connection and smooth flow between the introduction and conclusion chapters, even though they’re on opposite ends of your document.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the conclusion chapter

Now that you have a clearer view of what the conclusion chapter is about, let’s break down the structure of this chapter so that you can get writing. Keep in mind that this is merely a typical structure – it’s not set in stone or universal. Some universities will prefer that you cover some of these points in the discussion chapter , or that you cover the points at different levels in different chapters.

Step 1: Craft a brief introduction section

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, the conclusions chapter needs to start with a brief introduction. In this introductory section, you’ll want to tell the reader what they can expect to find in the chapter, and in what order . Here’s an example of what this might look like:

This chapter will conclude the study by summarising the key research findings in relation to the research aims and questions and discussing the value and contribution thereof. It will also review the limitations of the study and propose opportunities for future research.

Importantly, the objective here is just to give the reader a taste of what’s to come (a roadmap of sorts), not a summary of the chapter. So, keep it short and sweet – a paragraph or two should be ample.

Step 2: Discuss the overall findings in relation to the research aims

The next step in writing your conclusions chapter is to discuss the overall findings of your study , as they relate to the research aims and research questions . You would have likely covered similar ground in the discussion chapter, so it’s important to zoom out a little bit here and focus on the broader findings – specifically, how these help address the research aims .

In practical terms, it’s useful to start this section by reminding your reader of your research aims and research questions, so that the findings are well contextualised. In this section, phrases such as, “This study aimed to…” and “the results indicate that…” will likely come in handy. For example, you could say something like the following:

This study aimed to investigate the feeding habits of the naked mole-rat. The results indicate that naked mole rats feed on underground roots and tubers. Further findings show that these creatures eat only a part of the plant, leaving essential parts to ensure long-term food stability.

Be careful not to make overly bold claims here. Avoid claims such as “this study proves that” or “the findings disprove existing the existing theory”. It’s seldom the case that a single study can prove or disprove something. Typically, this is achieved by a broader body of research, not a single study – especially not a dissertation or thesis which will inherently have significant limitations . We’ll discuss those limitations a little later.

Step 3: Discuss how your study contributes to the field

Next, you’ll need to discuss how your research has contributed to the field – both in terms of theory and practice . This involves talking about what you achieved in your study, highlighting why this is important and valuable, and how it can be used or applied.

In this section you’ll want to:

- Mention any research outputs created as a result of your study (e.g., articles, publications, etc.)

- Inform the reader on just how your research solves your research problem , and why that matters

- Reflect on gaps in the existing research and discuss how your study contributes towards addressing these gaps

- Discuss your study in relation to relevant theories . For example, does it confirm these theories or constructively challenge them?

- Discuss how your research findings can be applied in the real world . For example, what specific actions can practitioners take, based on your findings?

Be careful to strike a careful balance between being firm but humble in your arguments here. It’s unlikely that your one study will fundamentally change paradigms or shake up the discipline, so making claims to this effect will be frowned upon . At the same time though, you need to present your arguments with confidence, firmly asserting the contribution your research has made, however small that contribution may be. Simply put, you need to keep it balanced .

Step 4: Reflect on the limitations of your study

Now that you’ve pumped your research up, the next step is to critically reflect on the limitations and potential shortcomings of your study. You may have already covered this in the discussion chapter, depending on your university’s structural preferences, so be careful not to repeat yourself unnecessarily.

There are many potential limitations that can apply to any given study. Some common ones include:

- Sampling issues that reduce the generalisability of the findings (e.g., non-probability sampling )

- Insufficient sample size (e.g., not getting enough survey responses ) or limited data access

- Low-resolution data collection or analysis techniques

- Researcher bias or lack of experience

- Lack of access to research equipment

- Time constraints that limit the methodology (e.g. cross-sectional vs longitudinal time horizon)

- Budget constraints that limit various aspects of the study

Discussing the limitations of your research may feel self-defeating (no one wants to highlight their weaknesses, right), but it’s a critical component of high-quality research. It’s important to appreciate that all studies have limitations (even well-funded studies by expert researchers) – therefore acknowledging these limitations adds credibility to your research by showing that you understand the limitations of your research design .

That being said, keep an eye on your wording and make sure that you don’t undermine your research . It’s important to strike a balance between recognising the limitations, but also highlighting the value of your research despite those limitations. Show the reader that you understand the limitations, that these were justified given your constraints, and that you know how they can be improved upon – this will get you marks.

Next, you’ll need to make recommendations for future studies. This will largely be built on the limitations you just discussed. For example, if one of your study’s weaknesses was related to a specific data collection or analysis method, you can make a recommendation that future researchers undertake similar research using a more sophisticated method.

Another potential source of future research recommendations is any data points or analysis findings that were interesting or surprising , but not directly related to your study’s research aims and research questions. So, if you observed anything that “stood out” in your analysis, but you didn’t explore it in your discussion (due to a lack of relevance to your research aims), you can earmark that for further exploration in this section.

Essentially, this section is an opportunity to outline how other researchers can build on your study to take the research further and help develop the body of knowledge. So, think carefully about the new questions that your study has raised, and clearly outline these for future researchers to pick up on.

Step 6: Wrap up with a closing summary

Tips for a top-notch conclusion chapter

Now that we’ve covered the what , why and how of the conclusion chapter, here are some quick tips and suggestions to help you craft a rock-solid conclusion.

- Don’t ramble . The conclusion chapter usually consumes 5-7% of the total word count (although this will vary between universities), so you need to be concise. Edit this chapter thoroughly with a focus on brevity and clarity.

- Be very careful about the claims you make in terms of your study’s contribution. Nothing will make the marker’s eyes roll back faster than exaggerated or unfounded claims. Be humble but firm in your claim-making.

- Use clear and simple language that can be easily understood by an intelligent layman. Remember that not every reader will be an expert in your field, so it’s important to make your writing accessible. Bear in mind that no one knows your research better than you do, so it’s important to spell things out clearly for readers.

Hopefully, this post has given you some direction and confidence to take on the conclusion chapter of your dissertation or thesis with confidence. If you’re still feeling a little shaky and need a helping hand, consider booking a free initial consultation with a friendly Grad Coach to discuss how we can help you with hands-on, private coaching.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

17 Comments

Really you team are doing great!

Your guide on writing the concluding chapter of a research is really informative especially to the beginners who really do not know where to start. Im now ready to start. Keep it up guys

Really your team are doing great!

Very helpful guidelines, timely saved. Thanks so much for the tips.

This post was very helpful and informative. Thank you team.

A very enjoyable, understandable and crisp presentation on how to write a conclusion chapter. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Thanks Jenna.

This was a very helpful article which really gave me practical pointers for my concluding chapter. Keep doing what you are doing! It meant a lot to me to be able to have this guide. Thank you so much.

Nice content dealing with the conclusion chapter, it’s a relief after the streneous task of completing discussion part.Thanks for valuable guidance

Thanks for your guidance

I get all my doubts clarified regarding the conclusion chapter. It’s really amazing. Many thanks.

Very helpful tips. Thanks so much for the guidance

Thank you very much for this piece. It offers a very helpful starting point in writing the conclusion chapter of my thesis.

It’s awesome! Most useful and timely too. Thanks a million times

Bundle of thanks for your guidance. It was greatly helpful.

Wonderful, clear, practical guidance. So grateful to read this as I conclude my research. Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *