Preventing police misconduct

Ervin Staub's research on "active bystandership" is the foundation of a program helping New Orleans police avert misconduct by fellow police officers

By Amy Novotney

October 2017, Vol 48, No. 9

Print version: page 30

- Forensics, Law, and Public Safety

- Gun Violence and Crime

In 2005, police misconduct in New Orleans had reached an all-time high. In the weeks before and after Hurricane Katrina, several high-profile beatings and unjustified shootings by police led to intense federal scrutiny of the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD), including a 2010 U.S. Department of Justice investigation and a 2013 federal consent decree to overhaul policies and promote greater transparency and more civilian oversight of the police force.

In 2017, the NOPD aspires to serve as a model for how to reduce police misconduct. Rather than standing silently by—or joining in on a fellow officer's brutality—New Orleans police are being trained to step in when they see their colleagues about to overreact in heated situations, tell them to take a break and urge them not to do something they will regret.

Much of this reform can be attributed to the work of retired University of Massachusetts, Amherst, psychologist Ervin Staub, PhD, who has applied his life's work on what he calls "active bystandership" to develop an officer-training program that emphasizes peer intervention. Known as "Ethical Policing Is Courageous," or EPIC, the program has become "a key part of the reforms instituted to remake the NOPD," according to Michael S. Harrison, the NOPD's superintendent of police.

The city is already seeing some positive effects: Since the NOPD launched EPIC last year, the department has seen fewer complaints against police officers, Harrison says.

The goal of the training is to provide officers with tools and strategies to help them prevent overreactions or potential misconduct by fellow officers by using tactics, such as discreet passwords or codes that encourage a colleague to calm down, stop what they're doing or let them know that another officer is taking over. In nonemergency situations, EPIC teaches officers how to speak to co-workers privately about potential problems, or to ask another trusted colleague to approach a colleague who is engaging in troubling behavior.

"The program appeals to the deep sense of relationships these officers have with one another by asking them, ‘If you would step in and take a bullet for your partner, what is preventing you from intervening when they're about to do something that could get them fired?'" says Mary Howell, JD, a civil rights attorney in New Orleans who knew about Staub's work and introduced it and him to the NOPD.

Bystanding by tragedy

Much of Staub's research has examined what leads witnesses to intervene in everyday emergencies and how passivity by people in some groups and societies is one contributor to an evolution toward genocide or other violence. His research began with expanding research by psychologists Bibb Latané, PhD, and John Darley, PhD, who found that as the number of bystanders increases, the likelihood that any one person will act decreases ( Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , Vol. 8, No. 4, 1968 ). Staub's research, however, found that this was not the case with young children. In a study with 232 children in kindergarten through sixth grade, researchers evaluated how participants—both alone and in pairs—responded when they heard sounds of a child's severe distress from an adjoining room ( Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , Vol. 14, No. 2, 1970 ).

"In kindergarten and first grade, the children support each other and are more likely to engage when they suspect a problem," Staub says. "But as they get older, they show a poker face, and if they don't see other people reacting, they will decide no action is necessary."

The study also showed that bystanders have great power. What the researchers said and how they responded to sounds from the other room greatly affected how participants reacted.

Staub has also found that individuals and groups change as a result of their own actions. This research was used to develop EPIC, as well as a training Staub has developed to reduce bullying in schools. In addition, interventions by his team to promote reconciliation in Rwanda led to more acceptance by Hutus and Tutsis of each other and engagement by survivors and former perpetrators.

Another aspect of the police training is helping officers overcome their conviction that loyalty to a fellow officer means accepting or joining in whatever he or she is doing, even if it is using unnecessary force.

"If, in the system, you're supposed to support your fellow officer all the time and you don't, you're often ostracized or outcast by your fellow officers and even superiors, so the cost of you intervening can be pretty substantial," Staub says. "That's one of the reasons why it's so important for the entire system, including superiors, to buy into the training, so that the culture really changes."

Today, nearly all of the NOPD force has been trained in EPIC, and the response from officers throughout the ranks has been overwhelmingly positive, Harrison says. Now, 28 law-enforcement agencies, including police departments in New York, Seattle, Las Vegas, Memphis and San Francisco, have requested program materials and inquired about the training.

Howell credits these effects to Staub and his commitment to "challenging the rest of us to think about how to be better people and how to not be silent," and putting his research to good use. "His work is a very good example of a successful transition of something that's fundamentally scientific and scholarly but has escaped the boundaries of the professional conversation and is making a huge impact on the larger world," she says.

Further reading

- Overcoming Evil: Genocide, Violent Conflict and Terrorism Staub, E., 2011

- The Roots of Goodness and Resistance to Evil: Inclusive Caring, Moral Courage, Altruism Born of Suffering, Active Bystandership and Heroism Staub, E., 2015

Related Articles

- APA efforts to improve police-community relations

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Police Attitudes Toward Abuse of Authority: Findings From a National Study, Research in Brief

Additional details, related topics, similar publications.

- The Sexual Stratification Hypothesis: Is the Decision to Arrest Influenced by the Victim/Suspect Racial/Ethnic Dyad?

- Perceptions of Service Recipients from the Street Level. A Response to LaFrance and Lees "Sheriffs and Police Chiefs Differential Perceptions of the Residents. They Serve An Exploration and Preliminary Rationale

- Advancing a Theory of Police Officer Training Motivation and Receptivity

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Race and police misconduct cases.

- Andrea M. Headley Andrea M. Headley McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University

- and Kwan-Lamar Blount-Hill Kwan-Lamar Blount-Hill Borough of Manhattan Community College

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.703

- Published online: 26 May 2021

Racial disparities abound in policing, and police misconduct is no exception. Literature on race and police misconduct can be categorized into three sub-themes: race and (a) civilian complaints about police misconduct, (b) public perceptions about police misconduct, and (c) officer perceptions of police misconduct. Racial disparities are apparent in the resolution of civilian complaints, and in perceptions of the ubiquity and severity of police misconduct. People of color may not always view accountability systems as legitimate or feel comfortable using formal complaint processes as a means of resolve. Officers of color report being disadvantaged by internal compliant processes, observing more misconduct than do their White peers, and feeling less comfortable with informal codes of silence. All officers generally rate misconduct involving use of force against civilians of color as more serious when compared to similar incidents involving white individuals. Officers of color, in particular, are more likely to admit beliefs that police treat people differently based on race and income. As with police outcomes more generally, race-based disparities in measures of misconduct likely persist due to a combination of complex and interconnected individual-, institutional-, and societal-level factors. Further research is needed. Lack of comprehensive reporting mechanisms nationwide poses challenges for scholars studying misconduct. There needs to be a greater diversity of methods used to study misconduct, including qualitative methods, and more evaluative studies of the variety of policies proposed as solutions to misconduct. The contexts of misconduct research must also be expanded beyond the United States and the Global North/West to offer international and comparative insights.

- police misconduct

- civilian complaints

- racial disparity

Introduction

Increased attention has been placed on policing in recent years due to the highly publicized deaths of people of color at the hands of police. While incidents that result in death are most often given intense media coverage and scrutiny, they have also sparked larger conversations around systemic racism, police use and abuse of discretion, and coercive authority broadly speaking. Public demonstrations, advocacy campaigns, and political platforms have all centered on policing, including the appropriate use of police services and governmental funding more generally. This current social, political, and economic climate requires a revisiting of the literature on race and police misconduct.

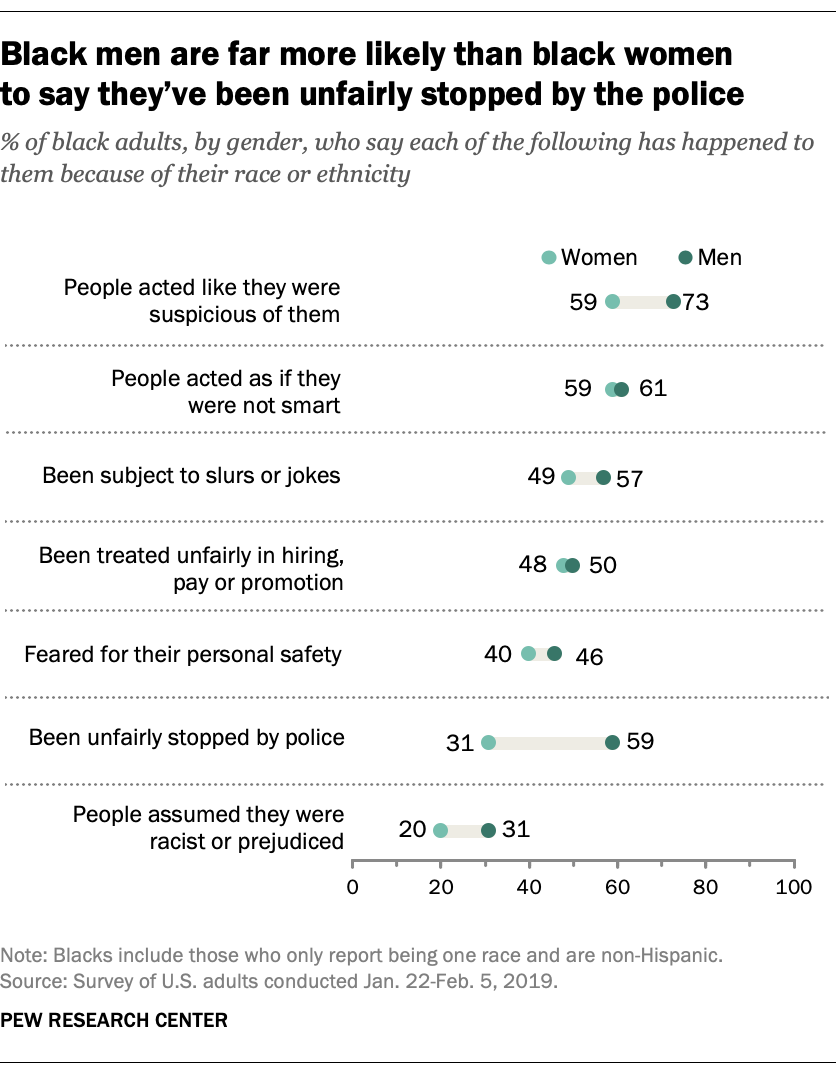

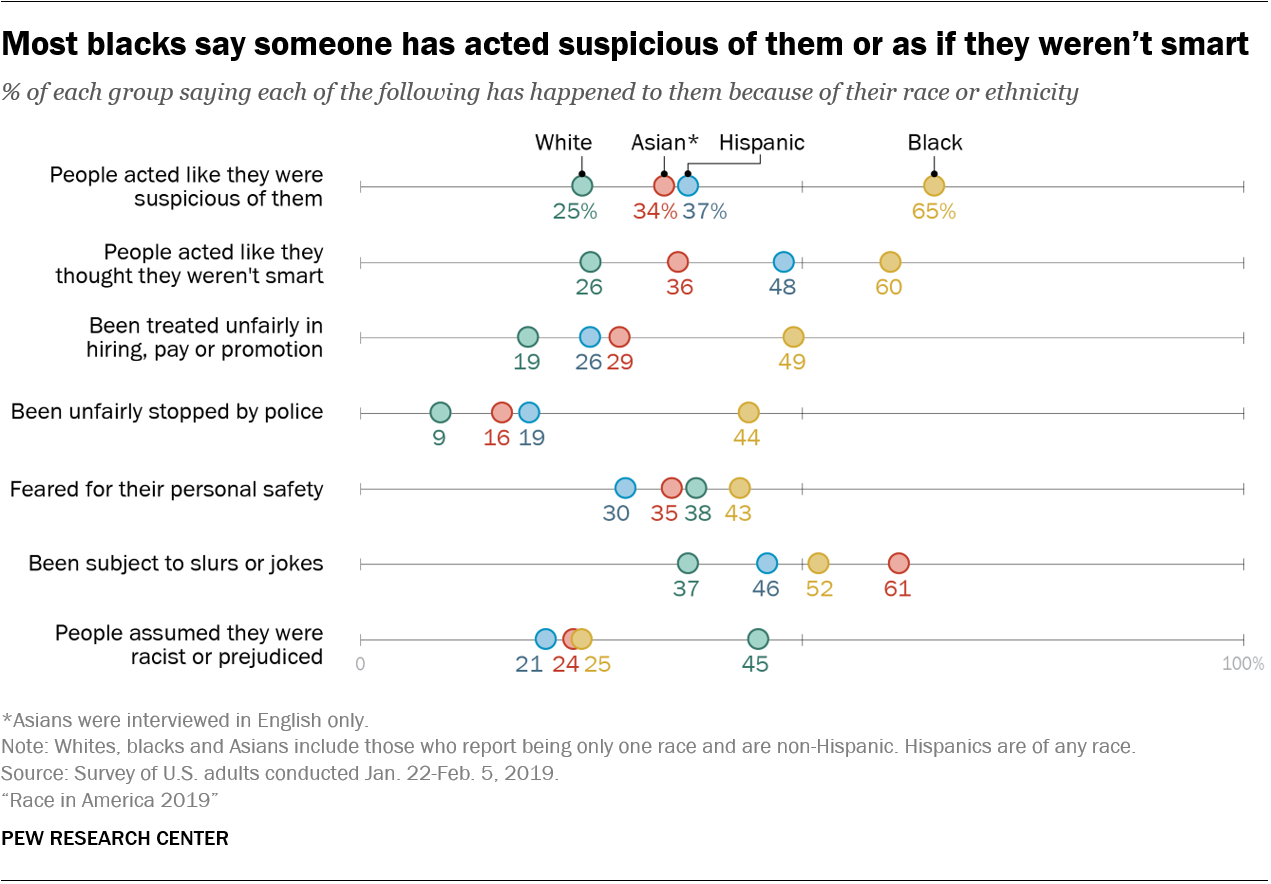

Racial and ethnic disparities abound in policing outcomes like arrest, stops and searches, and use of force. These disparities are also visible in public perceptions of and experiences with police misconduct. People of color report higher likelihoods of being subjected to unjustified stops and racial profiling (Engel, 2005 ; Lundman & Kaufman, 2003 ; Weitzer & Tuch, 2005 ) and are more likely to report being subject to disrespectful treatment, including verbal abuse, police prejudice, and physical abuse by police (Son & Rome, 2004 ). Not only do people of color disproportionately report greater personal negative experiences with police, but they also report increased likelihood of witnessing racial harassment and abuse of force perpetrated by police against others (Son & Rome, 2004 ). Personal and vicarious experiences with police misconduct have downstream implications for people of color’s levels of satisfaction with and attitudes toward the police (Avdija, 2010 ; Wu et al., 2009 ) and even have spillover effects into political and democratic engagement (Weaver et al., 2019 ).

This review proceeds by first providing a general overview of race and policing (primarily in the United States) followed by an overview of the broader police misconduct literature, where attention is devoted to defining and explaining misconduct. Next follows a review of the empirical research on the intersection of race and police misconduct. This is broken down into three subsections, focusing on race and (a) police misconduct as measured by complaints, (b) public perceptions about police misconduct, and (c) officer perceptions of police misconduct. Subsequent attention is given to unpacking the theoretical reasons for the persistence of racial disparities in policing. Finally, the review discusses solutions recommended to address and prevent racialized outcomes in police misconduct and concludes with directions for future research.

Race and Policing in the United States

It is now widely accepted among policing scholars that the history of law enforcement is dualistic and morally complicated. The first professionalized police department was established in Boston, Massachusetts, an improvement over the colonial-era bands of volunteers that had previously patrolled municipalities to ensure public order (Grant & Terry, 2017 ; Lundman, 1980 ). However, law enforcement also traces its history back to the “slave patrols” of the antebellum American South (Reichel, 1992 ). These were vigilante groups of armed White men organized to detect and capture slaves attempting to escape from their masters’ plantations and to mete out justice to Black individuals caught out-of-place or out-of-order. These two origin stories converge and entangle police history in a series of conflicting dualisms:

On the one hand, law enforcement agents have protected civil rights protesters, enforced desegregation orders, and protected Black students as they integrated public schools. On the other hand, law enforcement officers also helped enforce the Fugitive Slave Act prior to the Civil War, facilitated the convict leasing program during Reconstruction, enforced the Black codes and Jim Crow laws during the first half of the twentieth century , and quelled mass protests for racial justice from the 1960s up through the present. (Drakulich et al., 2020 , pp. 375–376)

Often, discussions concerning race and policing center on the collective experience of Black people, but police have tense histories with Native American, Latinx, and East Asian communities (Equal Justice Initiative, 2015 ; Lundman, 1974 ; Sun & Wu, 2018 ), as well as Muslim communities (Waxman, 2009 ), who are often racialized and conflated with Arab or Black. These histories have continued salience even today (e.g., Jones-Brown et al., 2020 ; Schroedel & Chin, 2020 ), evinced by still gaping racial disparities (Headley, 2020 ).

Soss and Weaver ( 2017 ) described American government as having two “faces.” One represents the liberal democratic ideal of a robust social contract wherein the public’s civic duty is matched by a caring and responsive state apparatus. The second “face” is the coercive and, according to some, oppressive and suppressive carceral state, with its criminal justice system and near monopoly over authorized use of force. Police officers have been agents of both but are experienced in poor communities of color (i.e., “race-class subjugated communities”; Soss & Weaver, 2017 , p. 567) overwhelming as representatives of the latter. By some estimates, Black people are nearly three times more likely to be detained by police on suspicion of a crime, and more than five times as likely to be stopped (Epp et al., 2017 ). Black people are arrested at more than double the rate of Whites (Hartney & Vuong, 2009 ). Residents of neighborhoods with higher concentrations of low socioeconomic status minorities are more heavily policed, with increased chances of being stopped and sanctioned, supplying a disproportionate number of residents for incarceration (Brunson & Weitzer, 2009 ; Kurgan & Cadora, 2005 ). Black and Latinx civilians are more likely to experience use of force during encounters with police, to do so more frequently, as well as to experience higher severity in the force applied (Bolger, 2015 ; Edwards et al., 2018 ; Fryer, 2019 ; Gau et al., 2010 ; Goff et al., 2016 ; Ross, 2015 ; Schimmack & Carlsson, 2020 ). Further, people of color often represent a disproportionate share of those killed by police, particularly those who are unarmed when killed (Edwards et al., 2019 ; Jones-Brown & Blount-Hill, 2020 ; Price & Payton, 2017 ). These findings get more complex when examining the interactive effects of officer and civilian race, where some research suggests that heightened or more severe force is used when there is racial or ethnic incongruence in use of force encounters (i.e., particularly in encounters with White officers and Black civilians; see Headley & Wright, 2020 ; Paoline et al., 2018 ; Wright & Headley, 2020 ). Still, intersectional identities are more negatively impacted by having a racial minority status, as in the case of gender-specific and sexual police misconduct against Black women (Ritchie & Jones-Brown, 2017 ) or against those faced with the double stigma of racial and sexual minority status (e.g., English et al., 2020 ).

Racial disparities are “numerical differences in outcomes between racial groups” (Khan & Martin, 2016 , p. 84). It is difficult to pinpoint the exact cause of disparities in criminal justice outcomes. At least three common hypotheses have been advanced: (a) certain races have disproportionate numbers of individuals engaging in crime, attracting and deserving police attention (an “individual/group-as-cause” thesis); (b) current socio-structural societal arrangements concentrate and enhance (e.g., through discrimination and hypersegregation) criminogenic factors (e.g., poverty, unemployment) within communities of color, decreasing opportunities for success and increasing crime (“society-as-cause”); and (c) the justice system itself is designed specifically to unfairly prosecute and persecute people of color (“system-as-cause”). While many of the early explanations placing individual blame on people of color have been discredited (e.g., atavism), references to minority cultures of violence are emblematic of these arguments (Hinton, 2016 ; for summary, see Blount-Hill, 2019 ). Researchers now more often explain crime committed by people of color by pointing to inequities in the larger society (e.g., the theory of African American offending of Unnever & Gabbidon, 2011 ). Building on the legacy of Massey and Denton’s demographic work ( 1988 , 1989 ; Massey & Tannen, 2015 ) on “hypersegregation”—highly disparate levels of population isolation and concentration—policing scholars have shown how racial groups’ structural exclusion from the benefits of society encourage contentiousness with police (e.g., Bell, 2017 ; Sampson & Bartusch, 1998 ). Moreover, scholars have increasingly begun disconnecting crime from police contact altogether in favor of explicit and/or implicit racial bias by police organizations as the predominant cause of disparity (see Tregle et al., 2019 for further discussion). Alexander’s The New Jim Crow ( 2010 ) details this phenomenon, while Hinton ( 2016 ) locates its historical roots at the highest levels of federal justice policy (see also St. John, V. J., 2019 ).

Defining and Understanding Police Misconduct

Whatever its roots, disproportionate contact with police leads to disproportionate opportunities for illegal or unethical treatment at the hands of police officers. Police misconduct includes a range of activities and behaviors by police violating ethical or legal rules, policies, and/or procedures whether internal or external to the organization, which are often “abusive, discriminatory, dishonest, fraudulent and/or coercive” (Headley et al., 2017 , p. 44). It is important to note that police misconduct has not been comprehensively conceptualized or operationalized consistently across police departments, which poses inherent challenges to adequately capturing data on the topic. As such, police misconduct types may vary, and activities include, but are not limited to, unjustifiable or unlawful uses of force, especially fatal shootings (e.g., Jones-Brown & Blount-Hill, 2020 ); police corruption (e.g., Ivković, 2009 ; Roebuck & Barker, 1974 ; Stinson et al., 2013 ); sexual misconduct (Cottler et al., 2014 ; Stinson et al., 2015 ); as well as officer participation in hate crimes against sexual minorities, the gender variant, and other marginalized groups (Moton et al., 2020 ; Wolff & Cokely, 2007 ). All misconduct is not necessarily illegal. “Integrity violations” include such actions as accepting questionable secondary employment, abuse of power, misuse of police resources, and, of course, preference or bias on the basis of race (Lasthuizen et al., 2011 ).

Police misconduct has often been conceived as an individual-level phenomenon—the “bad apple” problem. In a review of New York City Police Department (NYPD) records over 2 decades, Kane and White ( 2009 ) found misconduct associated with young officers without college education, and with criminal records and poor employment history, along with officers who were not promoted, who worked in more hectic patrol assignments, and those with prior histories of complaints (on this latter point, see also Harris & Worden, 2014 ). Their study is in line with several that preceded them (e.g., Malouff & Schutte, 1986 ). A countervailing argument is that police organizations produce environments that cultivate misconduct. According to Punch ( 2000 ), this is now the “new realism” and a conclusion on which most recent research converges. Lee et al. ( 2013 ) moved beyond individual officers to find that supervisors and overall departmental culture are highly influential on officers’ attitudes toward corruption. In a study analyzing data from nearly 500 police departments, Eitle et al. ( 2014 ) found that organization size, a full-time internal affairs unit, and department training is negatively associated with police misconduct. These and other studies imply that corruption may be a cultural and organizational phenomenon.

Nevertheless, siting misconduct’s origin at the organizational level invites further critique. Such arguments, along with blaming individual officers, may be seen as a mere smokescreen to cover larger sociocultural issues that would not require targeted sanctions but, instead, more radical professional and systemic reform (Bains, 2018 ). The analysis of discretionary stops by Epp et al. ( 2017 ) presents evidence of racial bias that permeates across organizations. Their findings suggest the influence of widespread professional norms shared by police officers across locales that violate principles of neutrality and objective enforcement. Similar dynamics can also encourage other forms of misconduct. Chappell and Piquero ( 2004 ) showed that officer norms were passed down not necessarily through organizational mandate but through social learning from peer officer. Ivković et al. ( 2018 ) found officers’ perception of a norm against reporting to be “the key factor” influencing willingness to report fellow officers’ misconduct—evidence of a “blue wall of silence,” likened to the Mafia code of omertá. That individual officer behavior can be influenced by social structures is found in international comparative literature as well. At a nation level, police corruption is negatively correlated with male school life expectancy (the number of years a male is likely to spend in school), the level of female involvement in the labor force, and economic development, while it is positively correlated with the size of the informal labor force (Gutierrez-Garcia & Rodríguez, 2016 ).

Race and Police Misconduct

Research specifically on race and police misconduct can be organized into three categories highlighting racial differences with regard to:

misconduct as measured by civilian complaints and/or internal complaint processes;

public perceptions toward and/or attitudes about police misconduct; and

police officer attitudes and/or perceptions of misconduct.

Race and Misconduct Complaints and Complaint Processes

By far the most used indicator of police misconduct in the literature is civilian complaints. Complaints not only get at public perceptions of experienced misconduct (Lersch, 1998 ) but also serve as a proxy for bureaucratic integrity and accountability (Hong, 2017 ). Generally, this literature examines either the impacts on misconduct of a civilian’s race or the racial makeup of the public (Eitle et al., 2014 ; Hickman & Piquero, 2009 ; Lersch, 1998 ) independent of racial identification among officers (Harris, 2010 , 2014 ; Harris & Worden, 2014 ; Hong, 2017 ; Kane & White, 2009 ; Rojek & Decker, 2009 ; Smith et al., 2015 ; Wolfe & Piquero, 2011 ), though some studies do examine implications for the race of both civilians and officers (Headley et al., 2017 ; Terrill & Ingram, 2016 ).

In examining the impact of complainant race on complaint outcomes, complainants of color fare worse once they lodge a formal complaint with a police department (Ajilore & Shirey, 2017 ). Specifically, Terrill and Ingram ( 2016 ) found that Black, Latinx, and other non-White civilians file more improper force complaints, yet, Black complainants have a lower likelihood of having their allegation sustained when compared to White complainants. Similarly, Headley et al. ( 2017 ) found that Black and Latinx complainants are less likely to have allegations “sustained” as compared to “not sustained,” “unfounded,” or “exoneration.” Lersch ( 1998 ) found that complaints involving encounters with proactive contacts, multiple officers on scene, officers with more years of service, and excessive force allegations are more often filed by civilians of color than Whites (yet, force complaints as compared to other types of complaints are less likely to be substantiated). While race may matter at the individual level, at the community level neither Eitle et al. ( 2014 ) nor Hickman and Piquero ( 2009 ) found statistical support for the impact of minority group threat and minority representation, respectively, on civilian complaints across U.S. police departments.

Next, turning to the race of the officer, the current research is mixed regarding whether racial or ethnic demographics correlate with the frequency of complaints that officers receive. Whereas scholarship documents that Black officers are less likely to have multiple complaints filed against them compared to their White peers (Wolfe & Piquero, 2011 ), other research suggests that Black officers receive complaints earlier in their career and more frequently when compared to White officers (Harris, 2014 ; Harris & Worden, 2014 ). Specifically, in a longitudinal analysis, Harris ( 2010 ) found that Black officers are significantly more likely to be in a higher complaint rate group, which had earlier onset, higher frequency, and longer duration of problematic behaviors. Still, officer race is not always a significant correlate of receiving a misconduct complaint, particularly complaints about police excessive use of force (Brandl et al., 2001 ; McElvain & Kposowa, 2004 ). While the aforementioned studies examine complaint outcomes within departments, rather than across departments, Hong ( 2017 ) found that police departments in the United Kingdom that have greater ethnic minority representation have less police misconduct overall (as indicated by a department’s total number of substantiated civilian complaints)—this finding is particularly salient when looking at complaints alleged by Black individuals.

Despite the mixed evidence on the likelihood or frequency of complaints, the research is fairly clear that complaints against Black officers are more likely to be sustained or substantiated (Harris, 2014 ; Headley et al., 2017 ; Terrill & Ingram, 2016 ). In examining career-ending misconduct, Kane and White ( 2009 ) found that Black and Latinx officers are more likely to be separated from the police department for serious or criminal misconduct as well as drugs. Officers of color also receive more internally generated complaints as compared to White officers, which usually result in a sustained outcome (Rojek & Decker, 2009 ). Rojek and Decker ( 2009 ) did not find differences in the severity of disciplinary actions following a sustained complaint outcome—so White officers and officers of color receive similar punishment outcomes. However, they do note that internally generated complaints often lead to harsher punishment irrespective of officer race, suggesting that disparity in the origin of complaints leads to some disparity in complaint outcomes. Further, Smith et al. ( 2015 ) examined how ethnic minority police officers in England and Wales perceive police misconduct investigation processes. They conclude that ethnic minority officers are more likely to experience being subject to formal proceedings whereas informal measures are used with White officers when investigating internal misconduct allegations. This supports prior research conducted in the United States that reveals that Black officers experience a two-tiered internal accountability and disciplinary system that favors White officers at the expense of Black officers (Bolton, 2003 ).

Race and Public Perceptions of Police Misconduct

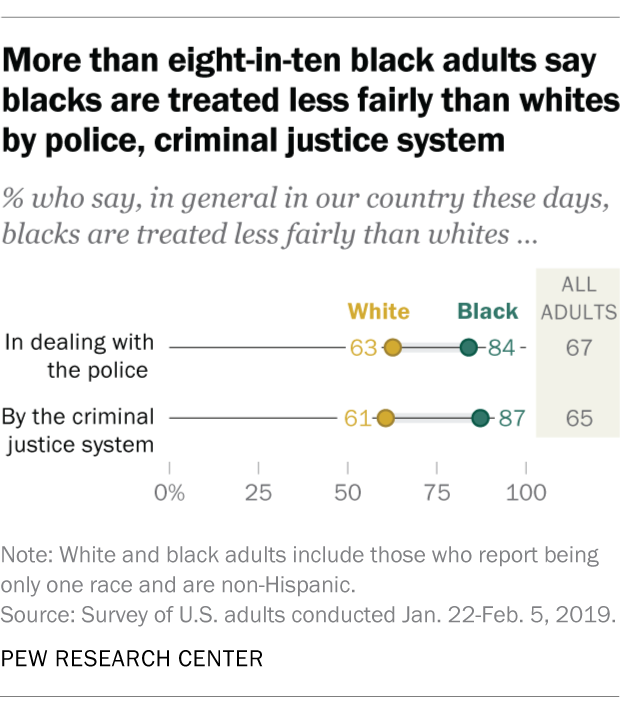

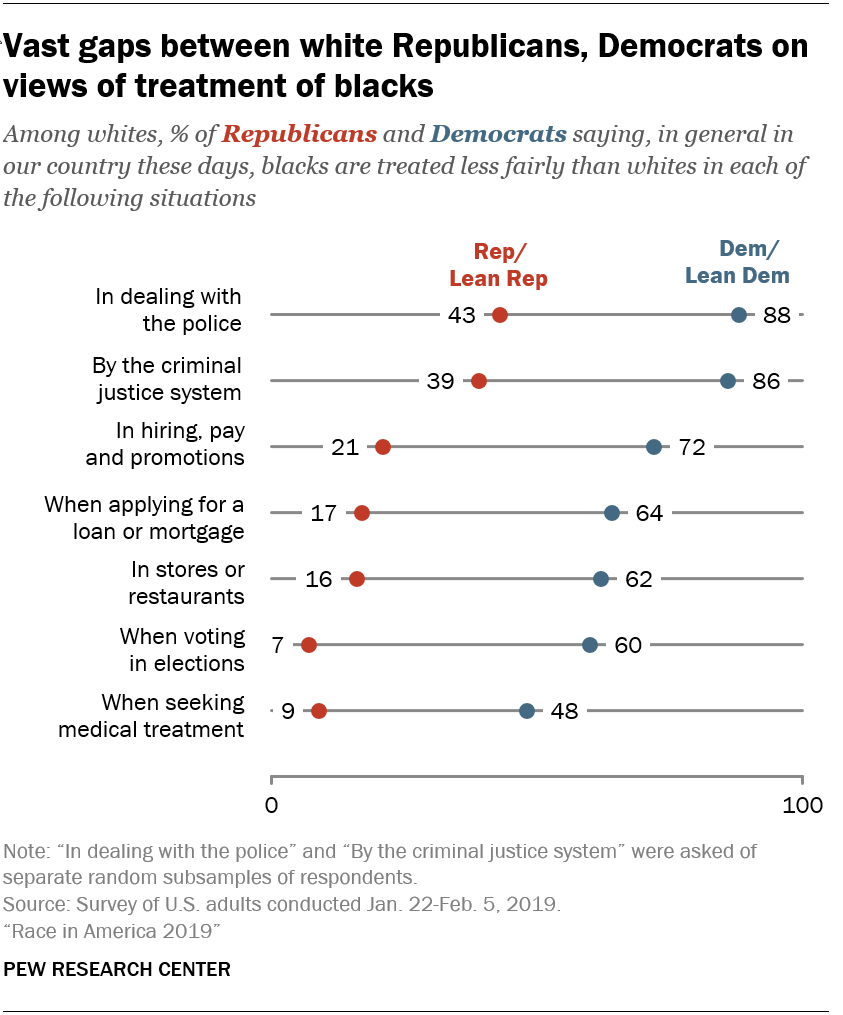

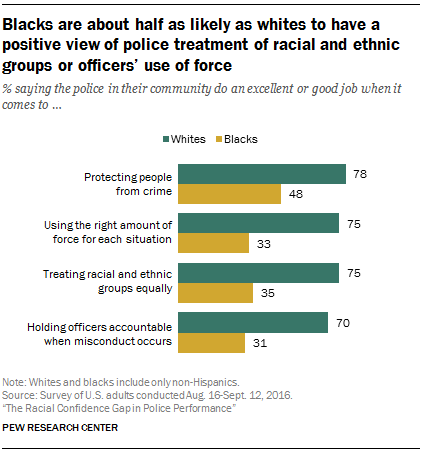

Another measure of police misconduct relies on perceptions of the public, who are likely to be most impacted by misconduct. The finding that White civilians have more favorable perceptions of and experiences with police has long been confirmed (Dowler & Zawilski, 2007 ; Sethuraju et al., 2019 ; Weitzer, 1999 ). Black residents perceive that White individuals are treated preferentially by the police (Brunson, 2007 ; Dowler & Zawilski, 2007 ), and people of color are also more likely to judge police misconduct incidents as more serious (Seron et al., 2004 ).

In an analysis of survey data from Black, Latinx, and White residents, Weitzer and Tuch ( 2004 ) found that there are significant racial differences in perception of police misconduct, with White respondents having the lowest likelihood of believing that police engage in misconduct, then Latinx, and then Black individuals, who have the highest likelihood of agreement. They also found that Black and Latinx respondents report more experiences with police misconduct and abuse overall. Seron et al. ( 2004 , 2006 ) used a vignette study to examine New York residents’ perceptions of seriousness on a variety of police misconduct incidents (e.g., unlawful or misuses of force, abuse of authority, discourteous or offensive verbal language). They found that knowing the race of a victim does not make a difference for the respondent’s rating of the degree of seriousness of police misconduct. However, the racial demographics of the respondent do make a difference in how they judge incidents: Black raters are more likely to judge the police misconduct as more serious when compared to White respondents (Seron et al., 2004 ). Apart from solely looking at Black and White differences, Sethuraju et al. ( 2019 ) compared university student perceptions of the frequency of police misconduct, as measured by unjustified stops, verbal abuse, and excessive physical force. Their results suggest that Black students, as compared to White and Asian students, believe there is more police misconduct in general and more in their respective neighborhoods. Native American students also believe there is more police misconduct compared to White students. In a qualitative analysis of young Black men’s experiences with the police, Brunson ( 2007 ) found that these men commonly report police harassment and mistreatment, aggressive or violent police behavior, and police misconduct (see also Brunson & Miller, 2006 ; Gau & Brunson, 2010 ). Brunson and colleagues concluded that negative contacts with the police accumulate over time, reduce confidence in processes of accountability, and, as such, are often not reported through formal complaint systems.

Other demographic and socioeconomic nuances may interact with race and shape perceptions about police misconduct. Using a mixed-methods approach to examine the impact of race and class on perceptions of police misconduct, Weitzer ( 1999 ) found that neighborhood class position shapes attitudes about police misconduct within race (e.g., comparing lower-class Black residents to middle-class Black residents), exhibiting an inverse relationship. This suggests that “police abuse of citizens is found disproportionately in groups with the least capacity to offer resistance” (Weitzer, 1999 , p. 843). Racial differences in perceptions are also complicated by other characteristics apart from class or socioeconomic status, including, but not limited to, education, gender, age, and personal and vicarious experiences with the police (Weitzer & Tuch, 2004 ).

A handful of studies include examinations of the impacts of media consumption as well as high-profile misconduct incidents on police misconduct perceptions and attitudes (Dowler & Zawilski, 2007 ; Graziano et al., 2010 ; Kaminski & Jefferis, 1998 ; Sethuraju et al., 2019 ; Weitzer, 2002 ; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004 ). Dowler and Zawilski ( 2007 ) found that the frequency of viewing network news has a stronger effect on non-White respondents’ perception of police misconduct as compared to White respondents. Similarly, Black and Latinx civilians who have frequent exposure to media reports about police abuse also believe that police misconduct happens more regularly (Weitzer & Tuch, 2004 ). That said, the type of media exposure matters, and Dowler and Zawilski ( 2007 ) noted that non-White respondents who frequently watch network news have stronger beliefs about racial discrimination by police, yet this relationship is reversed for non-White respondents who watch police reality programs.

Immediately following high-profile incidents of perceived misconduct (of scandals and excessive force) in New York City and Los Angeles, public opinion about and attitudes toward policing declined across White, Black, and Latinx residents, with the magnitude of attitudinal change being stronger for Black Americans (Weitzer, 2002 ), confirming prior research by Kaminski and Jefferis ( 1998 ). Alternatively, using experimental methods, Graziano et al. ( 2010 ) found that Black residents and other residents of color in Chicago hold stronger beliefs about how police use race as a decision-making cue, but that, over time and following a key racial profiling incident, all respondents’ beliefs about the use of racial profiling decreased. The authors’ attribute this decline to the influence of subsequent media construction and portrayal of the incident.

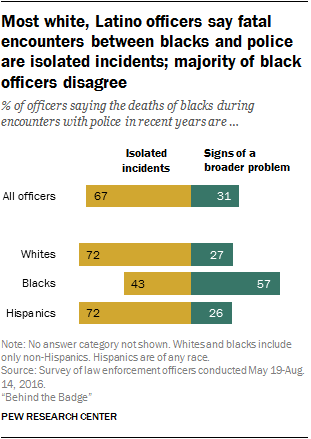

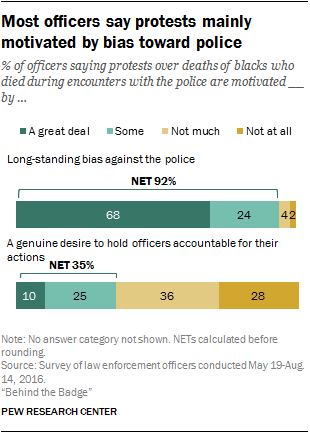

Race, Police Officer Perceptions, and Police Misconduct

Comparatively fewer studies assess racial differences in police officers’ perceptions and attitudes of misconduct. These studies, though limited, either focus on the race of the suspect or victim in an incident (Son et al., 1998 ) or the officer’s racial identity (Gau & Paoline, 2020 ; Wolfe & Piquero, 2011 ) and the respective impacts on officer perceptions. Son et al. ( 1998 ) found that officer behavior is usually the strongest predictor of police officers’ perceptions of the seriousness of a misconduct incident irrespective of suspect race. For instance, a police officer using excessive force is perceived as serious misconduct especially if the suspect died, was seriously injured or if the suspect was not resisting. However, when an officer uses physical harm to coerce a suspect with no prior record, officers rate this as more serious when the incident involves a Black suspect as compared to a White suspect. The authors concluded that there is no evidence of racial bias against Black suspects in police perceptions of the seriousness of misconduct. Regarding differences based on officer race, Gau and Paoline ( 2020 ) assessed officer perceptions of equitable treatment and procedural justice across racial groups in a midsized police department in Florida. They found that Black police officers (as compared to their peer officers) are more likely to share beliefs that police are biased against people of color or people with low-income, suggesting an admission of unequal treatment by race and socioeconomic status. Wolfe and Piquero ( 2011 ) assessed correlations between perceptions of organizational justice, the code of silence, and noble-cause corruption with police misconduct outcomes in Philadelphia. They found that officers who identify with a racial or ethnic minority group are less likely to agree with protecting their peers during misconduct allegations, excusing their peers for minor legal violations, and refusing to take action against misconduct by peers. Further, Son and Rome ( 2004 ) found that officers of color are more likely to report observing other officers use excessive force and engage in racial harassment, particularly when in neighborhoods or areas with heightened levels of perceived criminal activity.

Theoretical Explanations for the Persistence of Racial Disparities in Policing

Why does race persist as such a permanent and indelible factor in American policing? Policing is one in a network of institutions designed to uphold the status quo societal structure. Importantly, law enforcement has traditionally been tasked with upholding the ethics and morality of “the system,” as enshrined in its laws, a first and foremost defense against those who challenge existing norms. Claims to equality by marginalized groups (such as people of color) necessarily challenge an existing system of inequality which, especially when attended by civil upheaval, presents the exact kind of challenge police may feel duty-bound to quell. Moton et al. argue that, “as moral agents and defenders of what is ‘right’, officers may be apprehensive to relent to challenges to absolutist morality” and traditional views of propriety ( 2020 , p. 246). Individuals who feel allegiance to a social system—whether or not they are members of a group benefited by it—will rationalize justifications for its continuance, including “fair” reasons why racial minorities remain disparately disadvantaged (Uhlmann et al., 2010 ). The hypersegregation noted in Massey and Denton’s work ( 1988 , 1989 ) is both cause and consequence of continued resistance to integration by White people, as isolation spurs concentrated disadvantage, which spurs crime, which justifies isolation, and on and on in circular fashion. This social psychological process is called system justification, “the tendency of people to accept and defend the legitimacy of the status quo social order” (Blount-Hill, 2020 , p. 6). It often leads to Bayesian racism, “the belief that it is rational to discriminate against individuals based on stereotypes about their racial group” (Uhlmann et al., 2010 , p. 10; also called rational racism).

Khan and Martin ( 2016 ) provide a thorough review of the social psychological contributors to police bias leading to racial disparities in police treatment. Much recent attention has been given to the operation of implicit bias, harmful and discriminatory attitudes that are “held beneath conscious awareness, are more automatic in nature, and do not require intention or effort” (Khan & Martin, 2016 , p. 91). According to the theory of aversive racism, these biases can coexist with explicit beliefs about racial equality. Therefore, police officers may not only be outwardly non-racist, but may authentically believe themselves to be non-racist, while still subconsciously operating based on racist, stereotypical assumptions about the individuals they encounter. This is important, as similar cultural mechanisms shaping White officers’ perceptions of racial minorities might also shape minority officers’ perceptions of other groups and their own. As Jones-Brown and Blount-Hill ( 2020 ) warn, “Black minds are not immune to racially-biased enculturation merely because they reside in Black bodies” (p. 298). Officers may also perceive minorities—and especially Black men—as specifically dangerous based on stereotypes connecting Blackness to danger that stem from early American history and are propagated consistently throughout the culture in explicit and implicit ways (Owusu-Bempah, 2017 ).

Social psychological theories, while accounting for the individual in interaction with a social milieu, are nonetheless designed to explain internal thought processes at the level of individual persons. The work of Eterno et al. ( 2017 ) shows that organizations can place separate pressures on individual officers to engage in actions such as dubious investigatory stops. According to their work, the NYPD’s implementation of the CompStat (“compare statistics”) performance management system dramatically increased the sense of “high pressure” to stop-question-and-frisk on upper management by more than double, with similar effects on arrest and summons activity. Epp et al. ( 2017 ) used neo-institutional theory to explain how norms of misconduct reach beyond individual organizations and pervade an entire profession. According to this frame, “common institutionalized practices emerge from the sharing of ideas through professional networks rather than from official mandates” (Epp et al., 2017 , p. 171). In writing of how racially discriminatory practices come to pervade not only professions but the societal systems (e.g., the criminal justice system), Blount-Hill ( 2019 ) explains:

Theories of rational racism assert that racist views often rely on seemingly neutral overgeneralizations and that, when these individuals are concentrated in positions of power, biases become embedded in the decision-making of otherwise neutral governing systems to create separate and unequal outcomes. Marked divergence of one group’s experience versus another is such that the one system might as well be two—a single system, separate-experience scheme referred to as petit apartheid. (p. 185)

Within this two-in-one system, Black and Latinx individuals are greatly overrepresented in the criminal justice system writ large, a phenomenon termed disproportionate minority contact (St. John, 2019 ). A minority threat thesis argues that disproportionate policing of minorities increases as the proportional population of minorities increases, “a means to maintain hegemonic dominance in society or retain the status quo of majority power (i.e., White supremacy). Disproportionate minority contact is the intended result and a means to keep people of color from leveraging their population in a way that may disrupt the racial and ethnic hierarchy” (St. John, 2019 , pp. 45–46). Though there is mixed support for the thesis across studies, several have shown predictive power in a minority threat hypothesis—in other words, that sense of societal threat can cause a suppressive reaction from criminal justice systems, resulting in an exponential increase in minority individuals’ police contact and attendant rises in police misconduct (Holmes, 2000 ; Kane, 2002 ; but cf. Eitle et al., 2014 ). In a recent example, Duxbury ( 2020 ) used event-centered statistical analyses of data from 79 national surveys, covering from 1975 to 2012 , to demonstrate a correlation between minority group size, inter alia, white punitiveness, and sentencing policy changes. Notably, the sense of minority threat may be an individual experience but is exemplary of how biases, shared among a set of system actors, can coagulate into system-wide practices that then become self-sustaining with the enculturation of new entrants into the system hierarchy.

Reactive Measures and Preventive Solutions

Resulting from a complex web of societal institutions, professional norms, departmental cultures, and individual dispositions, both inherent and forged by police experience, significant and widespread change in police behavior to stifle misconduct is indeed daunting. However, several proposed solutions show promise.

By far, two of the most commonly and strongly advocated policy proposals for curbing misconduct are the use of body-worn cameras and the institution of civilian oversight boards. Body-worn cameras “can capture, from an officer’s point of view, video and audio recordings of activities, including traffic stops, arrests, searches, interrogations, and critical incidents such as officer-involved shootings” (Miller & Tolliver, 2014 , p. 1). The research on the efficacy of body-worn cameras is mixed (Lum et al., 2019 ). Some studies find generally positive findings (Ariel et al., 2015 ; Jennings et al., 2014 ; White et al., 2018 ), such as reductions in use of force (Farrar, 2014 ) and civilian complaints (Farrar, 2013 ; Goodall, 2007 ; Mesa Police Department, 2013 ), as well as in assaults on officers (ODS Consulting, 2011 ). Others find no support or modest support at best (Ariel, 2017 ; Edmonton Police Service, 2015 ; Headley et al., 2017 ). Reminiscent of the findings of Eterno et al. ( 2017 ) on the implementation of CompStat, body-worn cameras may also increase enforcement activity among officers, possibly by increasing their felt pressure to carry out departmental goals (Headley et al., 2017 ; Morrow et al., 2016 ). Further, there are no published studies to date examining the impact of body-worn cameras on racial disparities.

Civilian oversight mechanisms, most often in the form of civilian review boards, were advanced during the civil rights era as a direct recommendation for dealing with police abuses of discretion (Finn, 2001 ; Walker, 2006 ). While review boards vary in scope and magnitude, these external oversight bodies are often composed of community members tasked with reviewing or investigating civilian complaints and excessive use of force incidents. Some research shows no effect for civilian review boards on civilian complaints (Hickman & Piquero, 2009 ; Smith & Holmes, 2014 ) or assaults (Willits, 2014 ). However, other research suggests that the presence of these review boards indeed reduces racial disparities in discretionary disorderly conduct arrests and police homicides of civilians (Ali & Pirog, 2019 ) and correlates with fewer deadly force incidents (Willits & Nowacki, 2014 ). With both types of accountability mechanisms—body-worn cameras and civilian oversight boards—implementation is paramount. Lack of consistency in how such interventions are governed, used, implemented, and ultimately enforced can lead to inefficiency and ineffectiveness, quelling the original goals of ensuring accountability, curbing misconduct, and reducing racial disparities (Headley, 2020 ).

Other long-standing recommendations focus on training, particularly around cultural competence (the ability to interact respectfully with individuals across cultures), implicit bias, and the structural causes of minority disadvantage (e.g., Epp et al., 2017 ; Khan & Martin, 2016 ). Training can “serve as a way to equip officers with the tools, strategies, and techniques needed to effectively fulfill their job responsibilities” and “as a means to socialize police, teach preferred behaviors, and discourage unwanted behaviors” (Headley, 2020 , p. 90). Smith ( 2004 ) and Eitle et al. ( 2014 ) found that the number of in-service trainings hours is a statistically significant correlate of lower homicides by police and police misconduct, respectively. However, others found positive correlations between in-service training and police use of force (Lee et al., 2010 ). There are limited, if any at all, empirical studies published that evaluate the efficacy of implicit bias and cultural sensitivity trainings on police misconduct specifically, particularly racial disparities in police outcomes.

Departments and the entire police profession must reconsider metrics for measuring police performance (Eterno et al., 2017 ). The use of number of arrests or citations may encourage officers to seek out illegality, often needing to resort to questionable tactics that are concentrated on those least empowered to protect themselves and their communities. Khan and Martin ( 2016 ) pointed to the proposed End Racial Profiling Act, which, among other things, would prohibit the “targeting an individual based on race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation without other reliable information that links that person to a crime” (p. 109). It also establishes a national database for incidents of police misconduct, a recommendation with strong scholar support (e.g., Epp et al., 2017 ). Glaser ( 2015 ) noted the effectiveness in changing administrative policy around targeted practices and procedures that lead to racially disparate outcomes. His book, Suspect Race , recounts the example of the California Highway Patrol prohibiting the use of consent searches due to its disproportionate impact on people of color during drug interdictions and the positive implications thereof.

Others urge departments to put greater effort into discovering officers at risk for misconduct in the candidate hiring process (Arrigo & Claussen, 2003 ; Kane & White, 2009 ), and on interventions external to the department, such as a stronger commitment to prosecute police misconduct (Jones-Brown & Blount-Hill, 2020 ) and removing legal shields from civil suits against officers (Jones-Brown et al., 2020 ). Regardless of the mechanisms put forth to address racial disparities and police misconduct, no entirely novel proposal for police reform has been offered for decades; rather, similar proposals have been put forth time and time again (e.g., for a review of national police reform commissions see Headley & Wright, 2019 ). This fact begs the question whether the true problem is really ignorance of what to do or instead being fixed on not doing it (or not doing it effectively and fully resourced) (see also Weitzer, 2015 ).

Future Research Directions

As a whole, the empirical literature on police misconduct and race has displayed the following key points: First, people of color experience disparities with their complaint resolution outcomes, often having a lower likelihood of having their complaint sustained. Second, officers of color commonly report feeling disadvantaged by the internal compliant investigatory processes. Third, young men of color often report more aggressive, abusive and hostile experiences with the police, which can reduce their trust in systems of accountability and thus may not be captured by formal complaints. Fourth, people of color perceive police misconduct as more serious and occurring more frequently than do their White counterparts. These disparities can be exacerbated by sociodemographic nuances (such as class) as well as experiential factors (such as media exposure and high-profile incidents). Fifth, officers may perceive officer misconduct involving Black victims as more serious than those incidents with White victims. Sixth, racial differences exist among officers where officers of color report stronger beliefs that police treat people unequally based on race and class. Lastly, officers of color are less likely to identify with code of silence beliefs and more likely to report observing their peers engage in misconduct.

Various reasons have been put forth to understand the persistence and prevalence of racial disparities; however, it is likely a combination of complex and interconnected individual-, institutional-, and societal-level factors. While there is ample research explaining the presence of disparities in certain key misconduct outcomes, there is need for further research that addresses the apparent gaps in the literature. First, the lack of comprehensive reporting mechanisms nationwide poses challenges for scholars studying the phenomena. Future research and public initiatives should put forth ways to measure and analyze the various types of police misconduct that occur in police departments and to incorporate key demographic information including, but not limited to, the race and ethnicity of officers and civilians. Thus far, scholars who assess race in their analyses of police misconduct often do so using quantitative methods, while only a few scholars engage in qualitative studies. However, qualitative research can offer important contextualized and nuanced insights that might otherwise be masked by purely quantitative studies (for instance, see Bolton, 2003 ; Brunson, 2007 ; Brunson & Miller, 2006 ; Gau & Brunson, 2010 ; Smith et al., 2015 ; Weitzer, 1999 ). Further, most of the research here fails to include evaluations of policies, practices, programs, or other interventions that prevent racial disparities in police misconduct perceptions or outcomes (with the exception of Ali & Pirog, 2019 ). Understanding the short- and long-term efficacy of proposed solutions is essential. Lastly, the majority of research has been conducted within the United States (for exceptions see Hong, 2017 and Smith et al., 2015 ); thus, future studies should explore cross-country and cross-cultural experiences with regard to race and police misconduct. Law enforcement officers are entrusted with power both awesome in scope and grave in its consequence. Perhaps the most crucial role researchers can have in the criminal justice system is to assist in regulating the use of that power for the public good.

Further Reading

- Ali, M. U. , & Pirog, M. (2019). Social accountability and institutional change: The case of citizen oversight of police. Public Administration Review , 79 (3), 411–426.

- Brunson, R. K. (2007). “Police don’t like black people”: African‐American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminology & Public Policy , 6 (1), 71–101.

- Gau, J. M. , & Paoline, E. A. (2020). Equal under the law: Officers’ perceptions of equitable treatment and justice in policing. American Journal of Criminal Justice , 45 , 474–492.

- Graziano, L. , Schuck, A. , & Martin, C. (2010). Police misconduct, media coverage, and public perceptions of racial profiling: An experiment. Justice Quarterly , 27 (1), 52–76.

- Harris, C. J. (2010). Problem officers? Analyzing problem behavior patterns from a large cohort. Journal of Criminal Justice , 38 (2), 216–225.

- Headley, A. M. (2020). Race, ethnicity and social equity in policing. In M. E. Guy & S. McCandless (Eds.), Achieving social equity: From problems to solutions (pp. 82–91). Melvin & Leigh.

- Headley, A. M. , D’Alessio, S. J. , & Stolzenberg, L. (2017). The effect of a complainant’s race and ethnicity on dispositional outcome in police misconduct cases in Chicago. Race and Justice , 10 (1), 43–61.

- Jones-Brown, D. , & Blount-Hill, K. (2020). Convicted: Do recent cases represent a shift in police accountability? A research note. Criminal Law Bulletin , 56 (2), 270–301.

- Kane, R. J. , & White, M. D. (2009). Bad cops: A study of career‐ending misconduct among New York City police officers. Criminology & Public Policy , 8 (4), 737–769.

- Khan, K. B. , & Martin, K. D. (2016). Policing and race: Disparate treatment, perceptions, and policy responses. Social Issues and Policy Review , 10 (1), 82–121.

- Rojek, J. , & Decker, S. H. (2009). Examining racial disparity in the police discipline process. Police Quarterly , 12 (4), 388–407.

- Sethuraju, R. , Sole, J. , Oliver, B. E. , & Prew, P. (2019). Perceptions of police misconduct among university students: Do race and academic major matter? Race and Justice , 9 (2), 99–122.

- Tregle, B. , Nix, J. , & Alpert, G. P. (2019). Disparity does not mean bias: Making sense of observed racial disparities in fatal officer-involved shootings with multiple benchmarks. Journal of Crime and Justice , 42 (1), 18–31.

- Wolfe, S. E. , & Piquero, A. R. (2011). Organizational justice and police misconduct. Criminal Justice and Behavior , 38 (4), 332–353.

- Ajilore, O. , & Shirey, S. (2017). Do #AllLivesMatter? An evaluation of race and excessive use of force by police. Atlantic Economic Journal , 45 (2), 201–212.

- Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness . The New Press.

- Ariel, B. (2017). Police body cameras in large police departments. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology , 106 (4), 729–768.

- Ariel, B. , Farrar, W. A. , & Sutherland, A. (2015). The effect of police body-worn cameras on use of force and citizens’ complaints against the police: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Quantitative Criminology , 31 (3), 509–535.

- Arrigo, B. A. , & Claussen, N. (2003). Police corruption and psychological testing: A strategy for preemployment screening. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology , 47 (3), 272–290.

- Avdija, A. S. (2010). The role of police behavior in predicting citizens’ attitudes toward the police. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice , 6 , 76–90.

- Bains, C. (2018). “A few bad apples”: How the narrative of isolated misconduct distorts civil rights doctrine . Indiana Law Journal , 93 (1), 29–55.

- Bell, M. C. (2017). Police reform and the dismantling of legal estrangement. Yale Law Journal , 126 , 2054–2150.

- Blount-Hill, K. (2019). From the war on poverty to the war on crime: The making of mass incarceration in America [Review of the book From the war on poverty to the war on crime: The making of mass incarceration in America by E. K. Hinton]. European Journal of American Culture , 38 (2), 185–187.

- Blount-Hill, K. (2020). Advancing a social identity model of system attitudes. International Annals of Criminology , 57 (1–2), 114–137.

- Bolger, P. C. (2015). Just following orders: A meta-analysis of the correlates of American police officer use of force decisions. American Journal of Criminal Justice , 40 (3), 466–492.

- Bolton, K. (2003). Shared perceptions: Black officers discuss continuing barriers in policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management , 26 , 386–399.

- Brandl, S. G. , Stroshine, M. S. , & Frank, J. (2001). Who are the complaint-prone officers?: An examination of the relationship between police officers’ attributes, arrest activity, assignment, and citizens’ complaints about excessive force. Journal of Criminal Justice , 29 (6), 521–529.

- Brunson, R. K. (2007). “Police don't like black people”: African‐American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminology & Public Policy , 6 (1), 71–101.

- Brunson, R. K. , & Miller, J. (2006). Young black men and urban policing in the United States. British Journal of Criminology , 46 (4), 613–640.

- Brunson, R. K. , & Weitzer, R. (2009). Police relations with Black and White youths in different urban neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review , 44 (6), 858–885.

- Chappell, A. T. , & Piquero, A. R. (2004). Applying social learning theory to police misconduct. Deviant Behavior , 25 (2), 89–108.

- Cottler, L. B. , O’Leary, C. C. , Nickel, K. B. , Reingle, J. M. , & Isom, D. (2014). Breaking the blue wall of silence: Risk factors for experiencing police sexual misconduct among female offenders. American Journal of Public Health , 104 (2), 338–344.

- Dowler, K. , & Zawilski, V. (2007). Public perceptions of police misconduct and discrimination: Examining the impact of media consumption. Journal of Criminal Justice , 35 (2), 193–203.

- Drakulich, K. , Wozniak, K. H. , Hagan, J. , & Johnson, D. (2020). Race and policing in the 2016 presidential election: Black Lives Matter, the police, and dog whistle politics. Criminology , 58 , 370–402.

- Duxbury, S. W. (2020). Who controls criminal law? Racial threat and the adoption of state sentencing law, 1975–2012 . American Sociological Review , 86 (1), 123–153.

- Edmonton Police Service . (2015). Body worn video: Considering the evidence . Final report of the Edmonton police service body worn video pilot project. Edmonton Police Service.

- Edwards, F. , Esposito, M. H. , & Lee, H. (2018). Risk of police-involved death by race/ethnicity and place, United States, 2012–2018. American Journal of Public Health , 108 (9), 1241–1248.

- Edwards, F. , Lee, H. , & Esposito, M. (2019). Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 116 (34), 16793–16798.

- Eitle, D. , D’Alessio, S. J. , & Stolzenberg, L. (2014). The effect of organizational and environmental factors on police misconduct. Police Quarterly , 17 (2), 103–126.

- Engel, R. S. (2005). Citizens’ perceptions of distributive and procedural injustice during traffic stops. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency , 42 (4), 445–481.

- English, D. , Carter, J. A. , Bowleg, L. , Malebranche, D. J. , Talan, A. J. , & Rendina, H. J. (2020). Intersectional social control: The roles of incarceration and police discrimination in psychological and HIV-related outcomes for Black sexual minority men. Social Science & Medicine , 258 , 113121.

- Epp, C. R. , Maynard-Moody, S. , & Haider-Markel, D. (2017). Beyond profiling: The institutional sources of racial disparities in policing. Public Administration Review , 77 (2), 168–178.

- Equal Justice Initiative . (2015). Lynching in America: Confronting the legacy of racial terror . Equal Justice Initiative.

- Eterno, J. A. , Barrow, C. S. , & Silverman, E. B. (2017). Forcible stops: Police and citizens speak out. Public Administration Review , 77 (2), 181–192.

- Farrar, W. (2013). Self-awareness to being watched and socially-desirable behavior: A field experiment on the effect of body-worn cameras and police use-of-force . Police Foundation.

- Farrar, W. (2014). Operation candid camera: Rialto police department’s body-worn cameras experiment. The Police Chief , 81 , 20–25.

- Finn, P. (2001). Citizen review of police: Approaches and implementation . US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

- Fryer, R. G. (2019). An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. Journal of Political Economy , 127 (3), 1210–1261.

- Gau, J. M. , & Brunson, R. K. (2010). Procedural justice and order maintenance policing: A study of inner‐city young men’s perceptions of police legitimacy. Justice Quarterly , 27 (2), 255–279.

- Gau, J. M. , Mosher, C. , & Pratt, T. C. (2010). An inquiry into the impact of suspect race on police use of Tasers. Police Quarterly , 13 (1), 27–48.

- Gau, J. M. , & Paoline, E. A. (2020). Equal under the law: Officers’ perceptions of equitable treatment and justice in policing . American Journal of Criminal Justice , 45 (3), 474–492.

- Glaser, J. (2015). Suspect race: Causes and consequences of racial profiling . Oxford University Press.

- Goff, P. A. , Lloyd, T. , Geller, A. , Raphael, S. , & Glaser, J. (2016, July). The science of justice: Race, arrests, and police use of force . Center for Policing Equity.

- Goodall, M. (2007). Guidance for the police use of body-worn video devices . Home Office.

- Grant, H. B. , & Terry, K. T. (2017). Law enforcement in the 21st century (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Gutierrez-Garcia, J. O. , & Rodríguez, L. (2016). Social determinants of police corruption: Toward public policies for the prevention of police corruption. Policy Studies , 37 (3), 216–235.

- Harris, C. J. (2014). The onset of police misconduct. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management , 37 (2), 285–304.

- Harris, C. J. , & Worden, R. E. (2014). The effect of sanctions on police misconduct. Crime & Delinquency , 60 (8), 1258–1288.

- Hartney, C. , & Vuong, L. (2009). Created equal: Racial and ethnic disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system . National Council on Crime and Delinquency.

- Headley, A. M. , Guerette, R. T. , & Shariati, A. (2017). A field experiment of the impact of body-worn cameras (BWCs) on police officer behavior and perceptions. Journal of Criminal Justice , 53 , 102–109.

- Headley, A. M. , & Wright, J. E. (2019). National police reform commissions: Evidence-based practices or unfulfilled promises? The Review of Black Political Economy , 46 (4), 277–305.

- Headley, A. M. , & Wright, J. E. (2020). Is representation enough? Racial disparities in levels of force and arrests by police. Public Administration Review , 80 (6), 1051–1062.

- Hickman, M. J. , & Piquero, A. R. (2009). Organizational, administrative, and environmental correlates of complaints about police use of force: Does minority representation matter? Crime & Delinquency , 55 (1), 3–27.

- Hinton, E. (2016). From the war on poverty to the war on crime: The making of mass incarceration in America . Harvard University Press.

- Holmes, M. D. (2000). Minority threat and police brutality: Determinants of civil rights criminal complaints in U.S. municipalities. Criminology , 38 , 343–368.

- Hong, S. (2017). Does increasing ethnic representativeness reduce police misconduct? Public Administration Review , 77 (2), 195–205.

- Ivković, S. K. (2009). Rotten apples, rotten branches, and rotten orchards. Criminology & Public Policy , 8 (4), 777–785.

- Ivković, S. K. , Haberfeld, M. , & Peacock, R. (2018). Decoding the code of silence. Criminal Justice Policy Review , 29 (2), 172–189.

- Jennings, W. G. , Fridell, L. A. , & Lynch, M. D. (2014). Cops and cameras: Officer perceptions of the use of body-worn cameras in law enforcement. Journal of Criminal Justice , 42 (6), 549–556.

- Jones-Brown, D. , Ruffin, J. , Blount-Hill, K. , Dawson, A. , & Cottrell, C. (2020). Hernández v. Mesa and police liability for youth homicides before and after the death of Michael Brown. Criminal Law Bulletin , 56 (5), 833–871.

- Kaminski, R. J. , & Jefferis, E. S. (1998). The effect of a violent televised arrest on public perceptions of the police: A partial test of Easton’s theoretical framework. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management , 21 , 683–706.

- Kane, R. J. (2002). The social ecology of police misconduct. Criminology , 40 , 867–896.

- Kurgan, L. , & Cadora, E. (2005). Million dollar blocks .

- Lasthuizen, K. , Huberts, L. , & Heres, L. (2011). How to measure integrity violations. Public Management Review , 13 (3), 383–408.

- Lee, H. , Jang, H. , Yun, I. , Lim, H. , & Tushaus, D. W. (2010). An examination of police use of force utilizing police training and neighborhood contextual factors: A multilevel analysis. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management , 33 , 681–702.

- Lee, H. , Lim, H. , Moore, D. D. , & Kim, J. (2013). How police organizational structure correlates with frontline officers’ attitudes toward corruption: A multilevel model. Police Practice and Research , 14 (5), 386–401.

- Lersch, K. M. (1998). Predicting citizen race in allegations of misconduct against the police. Journal of Criminal Justice , 26 (2), 87–97.

- Lum, C. , Stoltz, M. , Koper, C. S. , & Scherer, J. A. (2019). Research on body‐worn cameras: What we know, what we need to know. Criminology & Public Policy , 18 (1), 93–118.

- Lundman, R. J. (1974). Routine police arrest practices: A commonweal perspective. Social Problems , 22 (1), 127–141.

- Lundman, R. J. (1980). Police and policing: An introduction . Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Lundman, R. J. , & Kaufman, R. L. (2003). Driving while Black: Effects of race, ethnicity, and gender on citizen self-reports of traffic stops and police actions. Criminology , 41 (1), 195–220.

- Malouff, J. M. , & Schutte, N. S. (1986). Using biographical information to hire the best new police officers: Research findings. Journal of Police Science and Administration , 14 , 175–177.

- Massey, D. S. , & Denton, N. A. (1988). The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces , 67 (2), 281–315.

- Massey, D. S. , & Denton, N. A. (1989). Hypersegregation in U.S. metropolitan areas: Black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography , 26 , 373–391.

- Massey, D. S. , & Tannen, J. (2015). A research note on trends in Black hypersegregation. Demography , 52 , 1025–1034.

- McElvain, J. P. , & Kposowa, A. J. (2004). Police officer characteristics and internal affairs investigations for use of force allegations. Journal of Criminal Justice , 32 (3), 265–279.

- Mesa Police Department . (2013). On officer body camera system: Program evaluation and recommendations . Mesa Police Department.

- Miller, L. , & Tolliver, J. (2014). Implementing a body-worn camera program: Recommendations and lessons learned . Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

- Morrow, W. J. , Katz, C. M. , & Choate, D. E. (2016). Assessing the impact of police body-worn cameras on arresting, prosecuting, and convicting suspects of intimate partner violence. Police Quarterly , 19 (3), 303–325.

- Moton, L. , Blount-Hill, K. , & Colvin, R. A. (2020). Squaring the circle: Exploring lesbian experience in a heteromale police profession. In C. M. Coates & M. Walker-Pickett (Eds.), Women, minorities and criminal justice: A multicultural intersectionality approach (pp. 243–255). Kendall Hunt.

- ODS Consulting . (2011). Body worn video projects in Paisley and Aberdeen, self evaluation . ODS Consulting.

- Owusu-Bempah, A. (2017). Race and policing in historical context: Dehumanization and the policing of Black people in the 21st century. Theoretical Criminology , 21 (1), 23–34.

- Paoline, E. A., III , Gau, J. M. , & Terrill, W. (2018). Race and the police use of force encounter in the United States. The British Journal of Criminology , 58 (1), 54–74.

- Price, J. H. , & Payton, E. (2017). Implicit racial bias and police use of lethal force: Justifiable homicide or potential discrimination? Journal of African American Studies , 21 , 674–683.

- Punch, M. (2000). Police corruption and its prevention. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research , 8 , 301–324.

- Reichel, P. L. (1992). The misplaced emphasis on urbanization in police development. Policing and Society , 3 (1), 1–12.

- Ritchie, A. J. , & Jones-Brown, D. (2017). Policing race, gender, and sex: A review of law enforcement policies. Women & Criminal Justice , 27 (1), 21–50.

- Roebuck, J. B. , & Barker, T. (1974). A typology of police corruption. Social Problems , 21 (3), 423–437.

- Ross, C. T. (2015). Multi-level Bayesian analysis of racial bias in police shootings at the county-level in the United States, 2011–2014. PLoS ONE , 10 (11), e0141854.

- Sampson, R. J. , & Bartusch, D. J. (1998). Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: The neighborhood context of racial differences. Law & Society Review , 32 (4), 777–804.

- Schimmack, U. , & Carlsson, R. (2020). Young unarmed nonsuicidal male victims of fatal use of force are 13 times more likely to be Black than White. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 117 (3), 1263.

- Schroedel, J. R. , & Chin, R. J. (2020). Whose lives matter: The media’s failure to cover police use of lethal force against Native Americans. Race and Justice , 10 (2), 150–175.

- Seron, C. , Pereira, J. , & Kovath, J. (2004). Judging police misconduct: “Street‐level” versus professional policing. Law & Society Review , 38 (4), 665–710.

- Seron, C. , Pereira, J. , & Kovath, J. (2006). How citizens assess just punishment for police misconduct. Criminology , 44 (4), 925–960.

- Smith, B. W. (2004). Structural and organizational predictors of homicide by police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management , 27 , 539–557.

- Smith, B. W. , & Holmes, M. D. (2014). Police use of excessive force in minority communities: A test of the minority threat, place and community accountability hypotheses. Social Problems , 61 (1), 83–104.

- Smith, G. , Johnson, H. , & Roberts, C. (2015). Ethnic minority police officers and disproportionality in misconduct proceedings. Policing and Society , 25 (6), 561–578.

- Son, I. S. , Davis, M. S. , & Rome, D. M. (1998). Race and its effect on police officers’ perceptions of misconduct. Journal of Criminal Justice , 26 (1), 21–28.

- Son, I. S. , & Rome, D. M. (2004). The prevalence and visibility of police misconduct: A survey of citizens and police officers. Police Quarterly , 7 (2), 179–204.

- Soss, J. , & Weaver, V. (2017). Police are our government: Politics, political science, and the policing of race-class subjugated communities. Annual Review of Political Science , 20 , 565–591.

- St. John, V. J. (2019). Probation and race in the 1980s: A quantitative examination of felonious rearrests and minority threat theory. Race and Social Problems , 11 , 243–252.

- St. John, V. J. , & Lewis, V. (2020). “Vilify them night after night”: Anti-black drug policies, mass incarceration, and pathways forward. Harvard Kennedy School Journal of African American Policy , 20 , 18–29.

- Stinson, P. M. , Liederbach, J. , Brewer, S. L., Jr. , & Mathna, B. E. (2015). Police sexual misconduct: A national scale study of arrested officers. Criminal Justice Policy Review , 26 (7), 665–690.

- Stinson, P. M. , Liederbach, J. , Brewer, S. L., Jr. , Schmalzried, H. D. , Mathna, B. E. , & Long, K. L. (2013). A study of drug-related police corruption arrests. Policing: An International Journal , 36 (3), 491–511.

- Sun, I. Y. , & Wu, Y. (2018). Race, immigration, and social control: Immigrants’ views on the police . Palgrave Macmillan.

- Terrill, W. , & Ingram, J. R. (2016). Citizen complaints against the police: An eight city examination. Police Quarterly , 19 (2), 150–179.

- Uhlmann, E. L. , Brescoll, V. L. , & Machery, E. (2010). The motives underlying stereotype-based discrimination against members of stigmatized groups. Social Justice Research , 23 , 1–16.

- Unnever, J. D. , & Gabbidon, S. L. (2011). A theory of African American offending: Race, racism, and crime . Routledge.

- Walker, S. (2006). The history of citizen oversight. In J. Cintrón Perino (Ed.), Citizen oversight of law enforcement (pp. 1–10). American Bar Association.

- Waxman, M. C. (2009). Police and national security: American local law enforcement and counterterrorism after 9/11. Journal of National Security Law and Policy , 3 , 377–407.

- Weaver, V. , Prowse, G. , & Piston, S. (2019). Too much knowledge, too little power: An assessment of political knowledge in highly policed communities. The Journal of Politics , 81 (3), 1153–1166.

- Weitzer, R. (1999). Citizens’ perceptions of police misconduct: Race and neighborhood context. Justice Quarterly , 16 (4), 819–846.

- Weitzer, R. (2002). Incidents of police misconduct and public opinion. Journal of Criminal Justice , 30 (5), 397–408.

- Weitzer, R. (2015). American policing under fire: Misconduct and reform. Society , 52 , 475–480.

- Weitzer, R. , & Tuch, S. A. (2004). Race and perceptions of police misconduct. Social Problems , 51 (3), 305–325.

- Weitzer, R. , & Tuch, S. A. (2005). Racially biased policing: Determinants of citizen perceptions. Social Forces , 83 (3), 1009–1030.

- White, M. D. , Gaub, J. E. , & Todak, N. (2018). Exploring the potential for body-worn cameras to reduce violence in police-citizen encounters. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice , 12 (1), 66–76.

- Willits, D. W. (2014). The organizational structure of police departments and assaults on police officers. International Journal of Police Science & Management , 16 (2), 140–154.

- Willits, D. W. , & Nowacki, J. S. (2014). Police organisation and deadly force: An examination of variation across large and small cities. Policing and Society , 24 (1), 63–80.

- Wolff, K. B. , & Cokely, C. L. (2007). “To protect and serve?”: An exploration of police conduct in relation to the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender community. Sexuality and Culture , 11 , 1–23.

- Wright, J. E. , & Headley, A. M. (2020). Police use of force interactions: Is race relevant or gender germane? The American Review of Public Administration , 50 (8), 851–864.

- Wu, Y. , Sun, I. Y. , & Triplett, R. A. (2009). Race, class or neighborhood context: Which matters more in measuring satisfaction with police? Justice Quarterly , 26 , 125–156.

Related Articles

- Police Violence

- Police Corruption

- Consent Decrees and Police Reform

- Errors of Justice in Policing

- Racial Inequality in Punishment

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Criminology and Criminal Justice. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 30 August 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

Fighting Police Abuse: A Community Action Manual

1. SOME OPERATING ASSUMPTIONS

2. GETTING STARTED — IDENTIFY THE PROBLEM

3. GATHER THE FACTS Forget the Official Data What You Really Need to Know, And Why Where To Get The Information, And How

4. CONTROLLING THE POLICE — COMMUNITY GOALS A Civilian Review Board Control of Police Shootings Reduce Police Brutality End Police Spying Oversight of Police Policy Improved Training Equal Employment Opportunity Certification and Licensing of Police Officers Accreditation of Your Police Department

5. ORGANIZING STRATEGIES Build Coalitions Monitor the Police Use Open Records Laws Educate the Public Use the Political Process to Win Reforms Lobby For State Legislation

A FINAL WORD

RESOURCES Bibliography Organizations ACLU Affiliates

CREDITS & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In the early hours of March 3, 1991, a police chase in Los Angeles ended in an incident that would become synonymous with police brutality: the beating of a young man named Rodney King by members of the Los Angeles Police Department. An amateur video, televised nationwide, showed King lying on the ground while three officers kicked him and struck him repeatedly with their nightsticks. No one who viewed that beating will ever forget its viciousness.

The Rodney King incident projected the brutal reality of police abuse into living rooms across the nation, and for a while, the problem was front page news. Political leaders condemned police use of excessive force and appointed special commissions to investigate incidents of brutality. The media covered the issue extensively, calling particular attention to the fact that police abuse was not evenly distributed throughout American society, but disproportionately victimized people of color.

But six years later, police abuse is still very much an American problem, as the following examples from three recent months demonstrate:

- In December 1996, two men in two weeks died in handcuffs at the hands of the Palm Beach County sheriff's deputies in Florida. Lyndon Stark, 48, died of asphyxia in a cloud of pepper spray while handcuffed behind the back in a prone position. Several days earlier, Kevin Pruiksma, 27, died after being restrained by a sheriff's deputy.