Life after COVID: most people don’t want a return to normal – they want a fairer, more sustainable future

Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol

Professor of Cognitive Psychology and Australian Research Council Future Fellow, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Stephan Lewandowsky receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 964728 (JITSUVAX). He also receives funding from the Australian Research Council via a Discovery Grant to Ullrich Ecker, from Jigsaw (a technology incubator created by Google), from UK Research and Innovation (through the Centre of Excellence, REPHRAIN), and from the Volkswagen Foundation in Germany. He also holds a European Research Council Advanced Grant (no. 101020961, PRODEMINFO) and receives funding from the John Templeton Foundation (via Wake Forest University’s Honesty Project).

Ullrich Ecker receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

University of Bristol provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We are in a crisis now – and omicron has made it harder to imagine the pandemic ending. But it will not last forever. When the COVID outbreak is over, what do we want the world to look like?

In the early stages of the pandemic – from March to July 2020 – a rapid return to normal was on everyone’s lips, reflecting the hope that the virus might be quickly brought under control. Since then, alternative slogans such as “ build back better ” have also become prominent, promising a brighter, more equitable, more sustainable future based on significant or even radical change.

Returning to how things were, or moving on to something new – these are very different desires. But which is it that people want? In our recent research , we aimed to find out.

Along with Keri Facer of the University of Bristol, we conducted two studies, one in the summer of 2020 and another a year later. In these, we presented participants – a representative sample of 400 people from the UK and 600 from the US – with four possible futures, sketched in the table below. We designed these based on possible outcomes of the pandemic published in early 2020 in The Atlantic and The Conversation .

We were concerned with two aspects of the future: whether it would involve a “return to normal” or a progressive move to “build back better”, and whether it would concentrate power in the hands of government or return power to individuals.

Four possible futures

| “Collective safety” | “For freedom” |

| “Fairer future” | “Grassroots leadership” |

In both studies and in both countries, we found that people strongly preferred a progressive future over a return to normal. They also tended to prefer individual autonomy over strong government. On balance, across both experiments and both countries, the “grassroots leadership” proposal appeared to be most popular.

People’s political leanings affected preferences – those on the political right preferred a return to normal more than those on the left – yet intriguingly, strong opposition to a progressive future was quite limited, even among people on the right. This is encouraging because it suggests that opposition to “building back better” may be limited.

Our findings are consistent with other recent research , which suggests that even conservative voters want the environment to be at the heart of post-COVID economic reconstruction in the UK.

The misperceptions of the majority

This is what people wanted to happen – but how did they think things actually would end up? In both countries, participants felt that a return to normal was more likely than moving towards a progressive future. They also felt it was more likely that government would retain its power than return it to the people.

In other words, people thought they were unlikely to get the future they wanted. People want a progressive future but fear that they’ll get a return to normal with power vested in the government.

We also asked people to tell us what they thought others wanted. It turned out our participants thought that others wanted a return to normal much more than they actually did. This was observed in both the US and UK in both 2020 and 2021, though to varying extents.

This striking divergence between what people actually want, what they expect to get and what they think others want is what’s known as “ pluralistic ignorance ”.

This describes any situation where people who are in the majority think they are in the minority. Pluralistic ignorance can have problematic consequences because in the long run people often shift their attitudes towards what they perceive to be the prevailing norm. If people misperceive the norm, they may change their attitudes towards a minority opinion, rather than the minority adapting to the majority. This can be a problem if that minority opinion is a negative one – such as being opposed to vaccination , for example.

In our case, a consequence of pluralistic ignorance may be that a return to normal will become more acceptable in future, not because most people ever desired this outcome, but because they felt it was inevitable and that most others wanted it.

Ultimately, this would mean that the actual preferences of the majority never find the political expression that, in a democracy, they deserve.

To counter pluralistic ignorance, we should therefore try to ensure that people know the public’s opinion. This is not merely a necessary countermeasure to pluralistic ignorance and its adverse consequences – people’s motivation also generally increases when they feel their preferences and goals are shared by others. Therefore, simply informing people that there’s a social consensus for a progressive future could be what unleashes the motivation needed to achieve it.

- United States

- Coronavirus

- Coronavirus insights

- United Kingdom (UK)

OzGrav Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Student Administration Officer

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

Senior Lecturer, Digital Advertising

Manager, Centre Policy and Translation

Three Years Later: How the Pandemic Changed Us

From routines to deep losses, the global health crisis altered lives of staff and faculty

Since her father’s death from COVID-19 in 2021, Alexy Hernandez’s days have become emotional minefields. Any small thing can be a gut punch, reminding her of what’s lost.

Perhaps it’s a football highlight, since she and her father, Josue, shared a love of the sport. Coffee has become complicated since her dad always got a kick out of pictures she sent of the creative designs left in her latte foam.

Or maybe it will simply be the small pieces of her daily routine — getting into work in the morning, coming home at night — experiences that warranted a quick text to her dad, who always wrote back with love and encouragement.

“He was my best friend, my biggest supporter, my biggest cheerleader,” said Hernandez, 28, a clinical research coordinator with the Department of Population Health Sciences . “I am who I am because of him.”

The pandemic changed the way most of us lived. We learned how to work remotely or gained new appreciation for human connection. And, for the loved ones of the roughly 1 million Americans who died from the virus, life will forever feel incomplete.

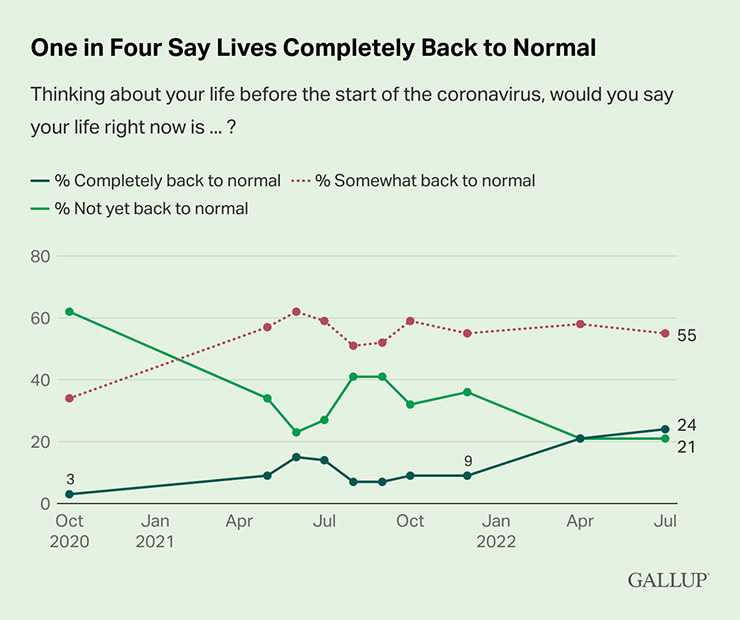

While the worst of the pandemic may be behind us, its effects linger. According to a Gallup poll , 53 percent of U.S. adults don’t expect their life to ever be the same as it was before the pandemic.

“We all felt this,” said Rachel Kranton, the James B. Duke Professor of Economics who, early in the pandemic, contributed to Project ROUSE , an independent Duke faculty research study that looked at how staff and faculty at Duke coped with changes to life, work, and well-being.

Project ROUSE showed that the pandemic had profound effects on everyone, including that, during the pandemic’s first year, roughly 40 percent of nearly 5,000 study respondents were at risk of moderate or severe depression.

As the pandemic’s difficult early days fade, Kranton said that other changes will likely endure, such as a willingness to connect in new ways, reassess careers, or build lives with more flexibility.

“I think there’s probably a new normal, and I think that new normal includes both good things and bad things,” Kranton said.

Hernandez’s life won’t be the same after her father’s death, but she is moving forward.

She’s learned not to stress about trivial things and thinks often about how she can make her father proud. Nothing, she said, can be taken for granted.

“Losing my dad has completely changed how I view and interact with the world and has given me more clarity on what I value,” said Hernandez, who has worked at Duke for four years.

We asked staff and faculty to share how the pandemic changed their lives, and here’s what some colleagues shared.

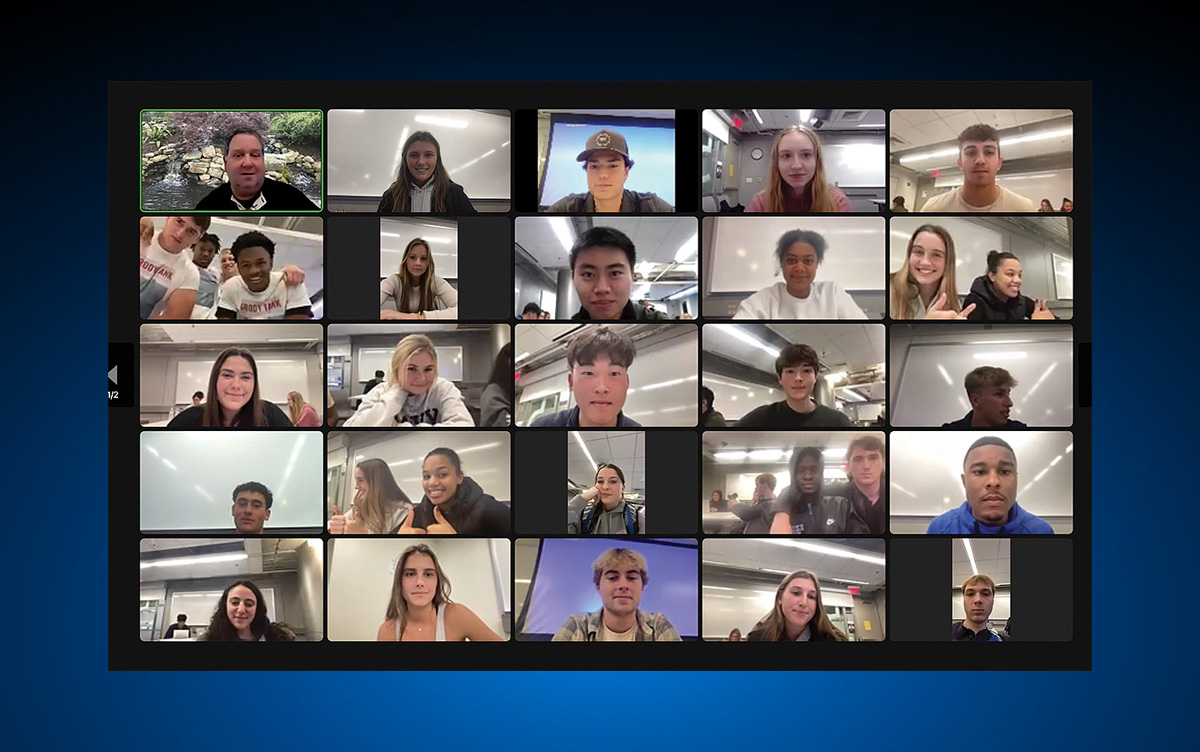

‘I’ve learned from students’

“It’s a new normal. You’ve got to deal with what you’ve got to deal with. Teaching markets and management, I’ve tried to move on and try to keep things fun. I like to make my courses interactive. So whether that’s changing materials or adding new things to a class, I’ve had to adapt. A lot of new stuff I’ve learned from students, whether it’s using polls, or Kahoot, or other activities. You’ve got to keep things fresh. The world is changing, you’ve got to change with it.”

George Grody, 64, Lecturing Fellow of Markets & Management, Trinity College of Arts and Sciences

Value of Life

“I appreciate more than ever before, not only the value of life, but a strong appreciation for others in the respiratory field and healthcare. I have been a respiratory therapist 33 years, and I’ve worked at Duke 35 years. Many have come and some have gone from this world. It’s devastating when you’ve worked so hard on patients, and they don’t make it out. Nothing can replace the value of life and what it means. Life is so important, and each and every day that you work with your patients is important. This all taught me a lot about what it means to really care for your patients, and it taught me a great deal of humility in caring for those who needed me.”

Pamela Bowman, 63, recently retired Respiratory Care Practitioner, Duke Regional Hospital

Out of the Quiet

“Though it’s crazy to say, my life started to flourish during the pandemic in more ways than one. I went back to school at the beginning of the pandemic at Durham Technical Community College to study business. I got in the best shape of my life by focusing on clean eating, and I lost 35 pounds. I started earning more money by taking a job at Duke. The pandemic was a time for me to quiet down the noise around me. Personally, I was able to shut out the world, decide what I really wanted out of life, and for myself, and start making those things happen. Ever since things started getting back to how they were pre-pandemic, those progressions I’ve made slowly started to derail. I gained back the 35 pounds I lost once the world started to open up again, and it’s just been harder to do everything I was doing to better myself every day. I went into a bit of a depression, but now I’m finally coming out of it. I’m back down 20 pounds. I’m learning how to cope with things and get back to being able to do those things that progressed for me and made me happy, even though I’m not able to get the same quietness I once had.”

Sadie Horton, 27, Staff Assistant, Academic Support, Fuqua School of Business

Cherish Loved Ones

“My mom, Johnnie Mae Snipes, was put on hospice on Jan. 11, 2021, and she passed away on January 20, 2021, at age 83. Me and my sisters were holding her hand, and, needless to say, we lost the strongest woman we ever knew. Our queen was gone. My mother had six daughters, 17 grandchildren, 44 great grandchildren and seven great, great grandchildren. My mother passed away from dementia and COVID. The past few years have taught me to never take anything for granted and to cherish your loved ones. It also has showed me how the world can change in one day. But one thing I know for sure that will never change is God is still in charge.”

Clara Bailey, 58, Staff Assistant, Department of Medicine, Oncology

‘I don’t go anywhere without my mask’

“When Dr. Anthony Fauci came out and said we need to wear masks in public, I did it. I’m claustrophobic, so when I first started wearing the cloth masks, I would have panic and anxiety attacks, particularly at the grocery store. Over time, I got used to it, and I started feeling safer by wearing my mask. Now, I don't think I will ever go into another crowded event without a mask. As a woman, we have our purses. We don’t go anywhere without our purses. Now, I don’t go anywhere without my mask. Since wearing my mask, I haven't caught a cold, let alone anything else. It's a piece of cloth, no big deal.”

Sandy Ouellette, 62, Access Specialist, Consultation & Referral Center

Rethinking What’s Most Important

“During the pandemic, my wife got a new job in Virginia, and because I’ve been working remote since March 2020, it made it easy to move with her because, in the past, somebody would have had to quit their job, find a new job, and do all kinds of stuff. Personally, the pandemic has made me rethink what’s most important in life, such as making sure to set aside time for family and friends. Now, I get to spend more time with my wife. We can do house projects, take our dogs out and explore. Now that our parents are getting older, we try to take advantage of any time we can spend with them. The pandemic made spending time with people who are important to you a little extra important because they’re what helped me get through.”

Christopher Morgenstern, 39, Administrative Manager, Cardiology

‘180-degrees different’

“My wedding, honeymoon, and bachelorette party were all canceled due to COVID, so my husband, Brent Durden, and I got married in our backyard with just our parents. We were going to wait several years to start a family so we could travel but decided to seize the day during quarantine after buying a house. Now, we have a beautiful 18-month-old daughter, Eliana. As tragic as the losses we experienced as a country and community have been through this pandemic, my entire world is 180-degrees different than it was before COVID, and it makes me so grateful to have the family that I do.”

Tricia Smar, 36, Education and Training Coordinator, Duke Trauma Center

‘I’m fulfilling my bucket list’

“I have terminal prostate cancer. I live one day at a time. They gave me 18 months to live about six years ago. During the pandemic, I retired to fulfill my bucket list only to find disappointment. I made all sorts of plans, but everything was shut down so my plans were shot. I returned to work. I have a love for nursing and have no regrets coming back to patient care. I missed interacting with people. I missed my coworkers, I missed the patients. Now I travel, and I'm fulfilling my bucket list, but I always look forward to coming back to Duke for both my own care and to care for our patients.”

Doug Buehrle, 68, Clinical Nurse, Apheresis, Duke University Hospital

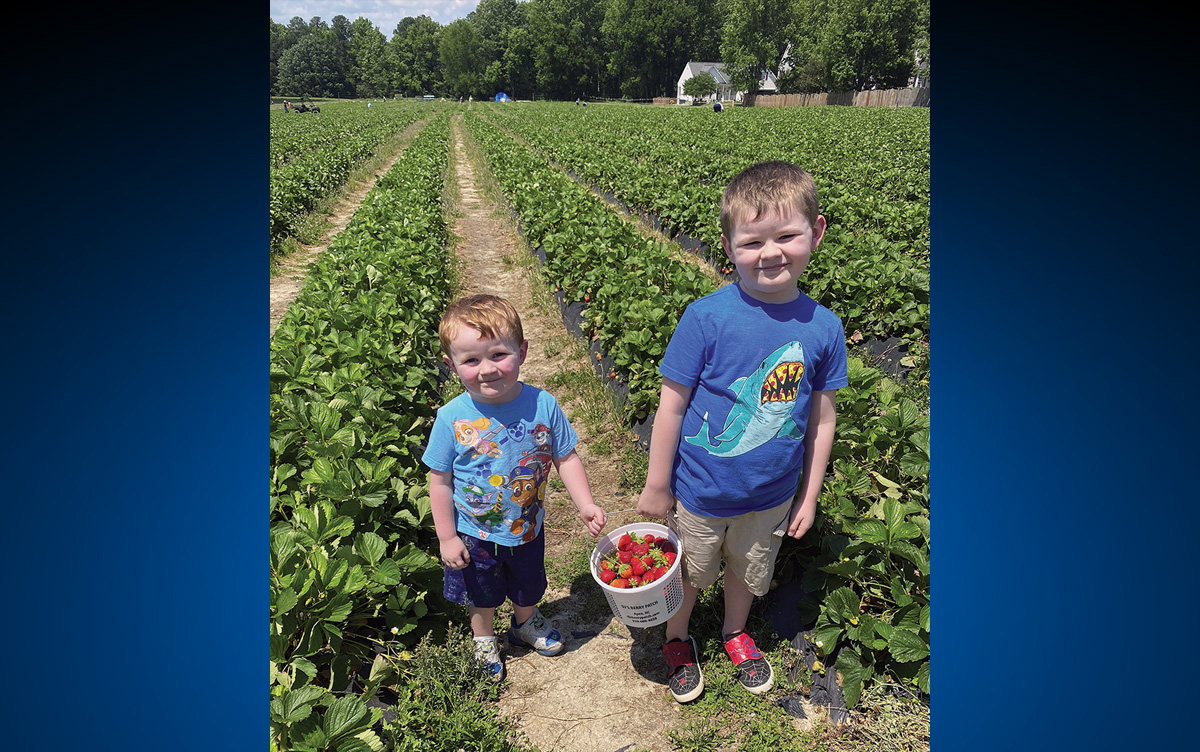

Savor Small Moments

“I learned to make the best out of a horrific situation. My kids, Derek and Joshua, were 5 and nearly 3 when COVID hit. In the clinical research field, we had to scramble to see which trials could keep going and which ones would have to go on pause. We had to be very flexible to work around each other’s schedules and everyone’s kid’s schedules. But I got to spend a lot more time with my kids than I ever would have if COVID didn't hit, so I'm grateful I was able to do it. We got to spend time going to the park and flying kites since the playgrounds were closed. We went hiking and exploring since the museums were closed. Those were memories I am thankful to have made, and I'm hoping they don't fade.”

Kristin Byrne, 41, Clinical Research Coordinator, Hematology

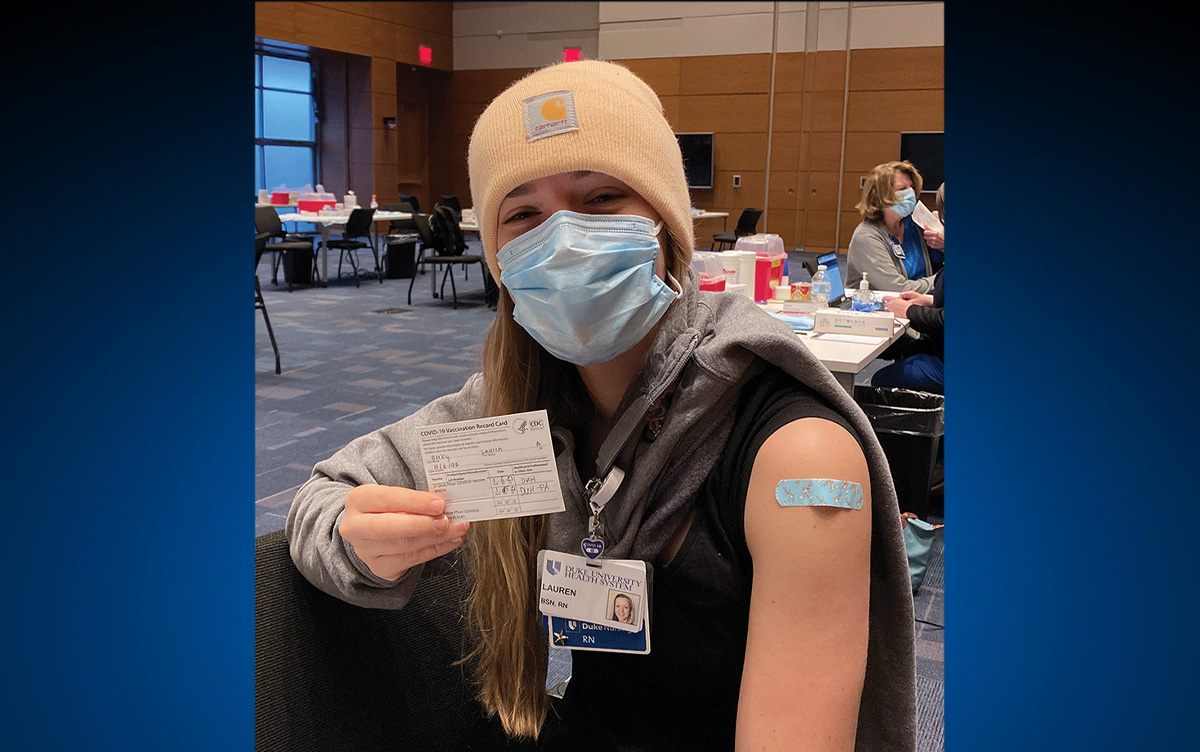

‘Packed up my car with as much as I could fit into it’

“I graduated from nursing school at George Fox University in Oregon about a month after lockdown happened. I have a grandmother in High Point, so I started applying to hospitals in North Carolina, and Duke turned out to be the best option. In October of 2020, I packed up my car with as much as I could fit into it, and I drove across the country with my dad. I left my family, friends, my church back in Portland, and I’ve had to build an entirely new life here. My first nursing job was working for the medical-surgical float pool at Duke University Hospital, which basically staffed the COVID-19 floors for a while. I was thrown into the thick of it, and I really had to stay on my toes all the time. It was really hard, and it was really a dark period in my life, until I started to get my feet settled. I just started to put myself out there out of my comfort zone, and I started inviting people to do things with me. I found Bright City Church too. Over time, I started to find those little sparks of hope, when you send a patient home instead of the ICU. I’ve learned a lot from my nursing career, and I’ve learned a lot about myself and how to take care of myself.”

Lauren Berky, 25, Clinical Nurse, Internal Staffing Resource Pool

‘More Openness to Change’

“I think COVID has opened the clinical community to change more than ever before. Sharing data has replaced hoarding data. Technology has come so far, and we had a hard time getting people to change the way they think about data. I think COVID opened their minds that we need other ways of dealing with data, particularly that the patient needs to be the centerpiece of everything that we’re doing. Some people have said to me, that five years ago we’d have been laughed at for some of the things we’re trying to do. But now, everybody is at least willing to have the conversation.”

William Edward Hammond, 88, Professor of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Family Medicine and Community Health

‘Never take tomorrow for granted’

“I am much more committed to ‘living in the moment,’ appreciating what I have, and looking inward. At home, I find joy with my husband. I walk much more. I cook at home almost all the time. And, maybe most important, I appreciate the beautiful natural environment around our home on Morgan Creek in Chapel Hill, where husband, David, and I began walking nearly every afternoon in January 2021. I’ve learned to never take tomorrow for granted. To appreciate friendships and family and the place where we are, now. To be OK with less ‘running around.’ To not take progress for granted, and to realize that things can get worse.”

Anne Mitchell Whisnant, 55, Director, Graduate Liberal Studies, and Associate Professor of the Practice, Social Science Research Institute

Bittersweet Milestones

“COVID was honestly a bittersweet time. My father-in-law, Mark, the president of North Georgia Technical College, passed away from COVID on September 13, 2020. Then in January 2021, my husband, Andrew, and I found out we were pregnant with our first child, Lilly, after a very long time. We thought we couldn’t have kids, so that was quite the surprise. When she was born on October 21, 2021, the joy of having her was indescribable. She just turned a year old, and I know she’ll never know her grandfather, and he’ll never know her. We want her to be happy and healthy and treat others the best way possible, and we’ll continue to tell her about her Papa when we can. We can’t wish Mark back because he’s not coming back. We’re living in the reality knowing that we can’t change it; it’s something Ecclesiastes calls our lot in life. COVID-19 brought out the worst for so many families, including ours, but it also brought so much good.”

Marissa Ivester, 34, Fellowship Program Coordinator, Office of Pediatrics

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write [email protected] .

- The COVID-19 Pandemic: Human Response Words: 1541

- Impact of COVID-19 on People’s Lives Words: 567

- The COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts on the US Words: 2569

- The COVID-19 Patients Stigmatization Words: 694

- COVID-19: The Effects on Humankind Words: 858

- Impact of IT on Healthcare During COVID-19 Words: 2261

- The Covid-19 Pandemic Impact on the Family Dynamic Words: 1623

- The COVID-19 Pandemic: Role of Leisure Words: 501

- The Effectiveness of the US in Response COVID-19 Pandemic Words: 575

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Symptoms and Causes Words: 1659

Life After COVID-19

COVID-19 is significantly impacting the lives of all people on the globe. Strict quarantine measures changed the attitude towards such simple things as walking in the park, talking to strangers, working, and studying in a team. What is more, people started to value the work of medics as keen as never before. Unfortunately, many nurses become victims of this virus. The current paper discusses the impact of COVID-19 on the loss of nurses on personal and professional levels.

The loss of nurses caused by the death from the coronavirus leads to the shortage of labor in health institutions. Someday, the pandemic will come to an end, and people will return to the usual lifestyle; however, the losses of nurses are irretrievable. During the pandemic situation, some countries such as China, Russia, Japan, the US send their medics to foreign countries. This help is relevant during these hard times. Nevertheless, after the pandemic, other states will hardly share their nurses, medical equipment, and medicines. The shortage of nurses will cause a higher workload on the doctors to whom they usually assist. It would be harder to take care of inpatients since nurses do a great job helping doctors to monitor them.

On a personal level, I admire medical staffers who work with people infected with the virus. They wear special costumes that minimize the probability of getting infected. Notwithstanding this fact, the statistics indicate how significant are the losses among the nurses. Grace Oghiehor-Enoma, a nurse from New York, compared physicians with fighters on the battlefield. She says: “You see the fire, and you are running into the fire, not thinking about yourself. That is the selflessness that you can see in nursing today” (World Health Organization, 2020). People used to underestimate the importance of nurses while now see who the saviors of humanity are.

To sum up, the work of nurses is an excellent feat. They are an example of people whom we must take an example. From the very beginning of the pandemic, it was apparent that the losses among nurses are inevitable. Nevertheless, no one could expect that these losses will be that big. Still, all of us could help them just staying home and minimizing the probability of getting infected.

World Health Organization. (2020). Support Nurses and Midwives through COVID-19 and beyond . Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, February 9). Life After COVID-19. https://studycorgi.com/life-after-covid-19/

"Life After COVID-19." StudyCorgi , 9 Feb. 2022, studycorgi.com/life-after-covid-19/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Life After COVID-19'. 9 February.

1. StudyCorgi . "Life After COVID-19." February 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/life-after-covid-19/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Life After COVID-19." February 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/life-after-covid-19/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Life After COVID-19." February 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/life-after-covid-19/.

This paper, “Life After COVID-19”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 9, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

COVID-19: Where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going

One of the hardest things to deal with in this type of crisis is being able to go the distance. Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel

Where we're going

Living with covid-19, people & organizations, sustainable, inclusive growth, related collection.

The Next Normal: Emerging stronger from the coronavirus pandemic

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Life Could Get Better (or Worse) After COVID

How do pandemics change our societies? It is tempting to believe that there will not be a single sector of society untouched by the COVID-19 pandemic . However, a quick look at previous pandemics in the 20th century reveals that such negative forecasts may be vastly exaggerated.

Prior pandemics have corresponded to changes in architecture and urban planning, and a greater awareness of public health . Yet the psychological and societal effects of the Spanish flu, the worst pandemic of the 20th century, were later perceived as less dramatic than anticipated, perhaps because it originated in the shadow of WWI. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud described Spanish flu as a “ Nebenschauplatz ”—a sideshow in his life of that time, even though he eventually lost one of his daughters to the disease. Neither do we recall much more recent pandemics: the Asian flu of 1957 and the Hong Kong flu from 1968.

Imagining and planning for the future can be a powerful coping mechanism to gain some sense of control in an increasingly unpredictable pandemic life. Over the past year, some experts proclaimed that the world after COVID would be a completely different place , with changed values and a new map of international relations. The opinions of oracles who were not downplaying the virus were mostly negative . Societal unrest and the rise of totalitarian regimes, stunted child social development, mental health crises, exacerbated inequality, and the worst economic recession since the Great Depression were just a few worries discussed by pundits and on the news.

Other predictions were brighter—the disruptive force of the pandemic would provide an opportunity to reshape the world for the better, some said. To complement the voices of journalists, pundits, and policymakers, one of us (Igor Grossmann) embarked on a quest to gather opinions from the world’s leading scholars on behavioral and social science, founding the World after COVID project.

The World after COVID project is a multimedia collection of expert visions for the post-pandemic world, including scientists’ hopes, worries, and recommendations. In a series of 57 interviews, we invited scientists, along with futurists, to reflect on the positive and negative societal or psychological change that might occur after the pandemic, and the type of wisdom we need right now. Our team used a range of methodological techniques to quantify general sentiment, along with common and unique themes in scientists’ responses.

The results of this interview series were surprising, both in terms of the variability and ambivalence in expert predictions. Though the pandemic has and will continue to create adverse effects for many aspects of our society, the experts observed, there are also opportunities for positive change, if we are deliberate about learning from this experience.

Three opportunities after COVID-19

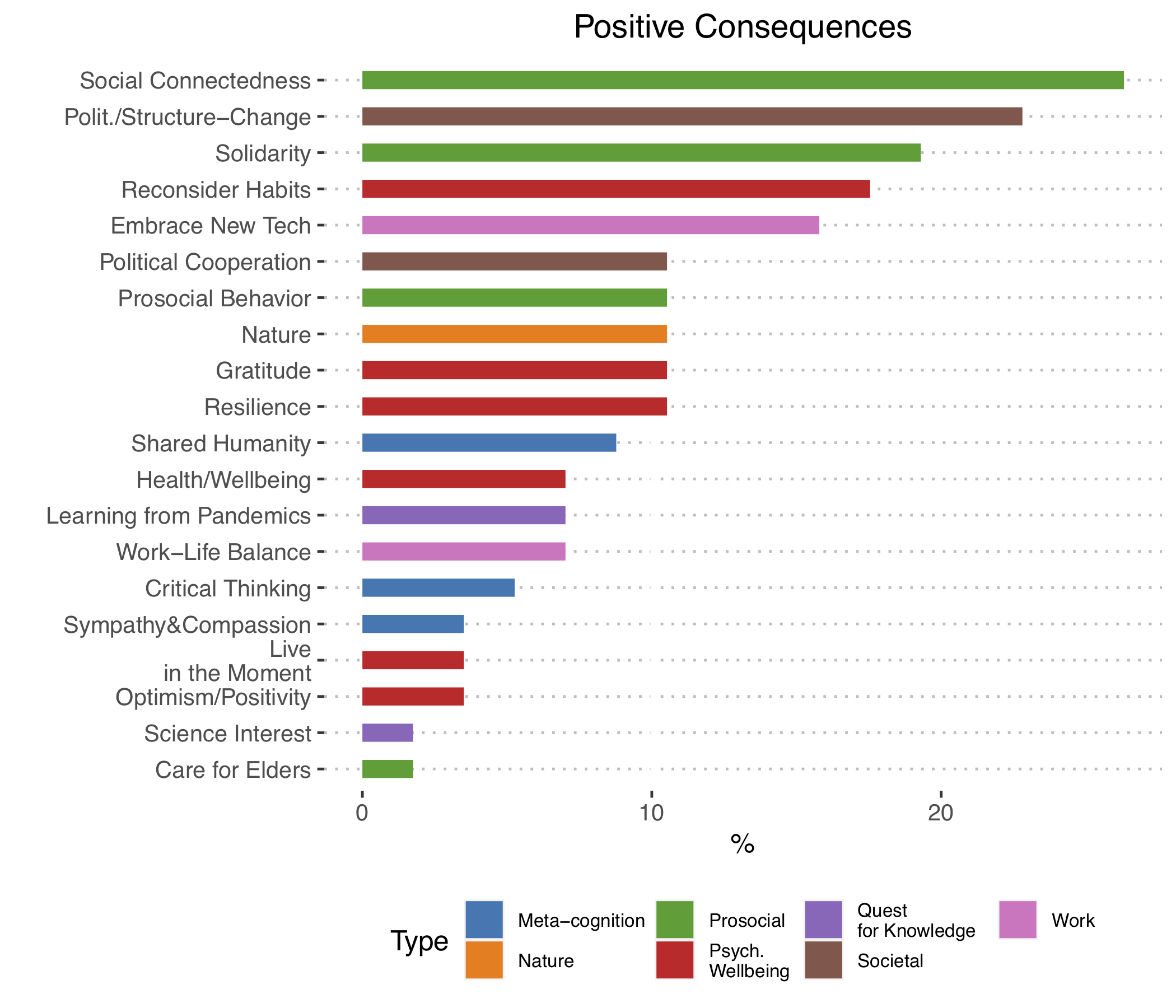

Scientists’ opinions about positive consequences were highly diverse. As the graph shows, we identified 20 distinct themes in their predictions. These predictions ranged from better care for elders, to improved critical thinking about misinformation, to greater appreciation of nature. But the three most common categories concerned social and societal issues.

1. Solidarity. Experts predicted that the shared struggles and experiences that we face due to the pandemic could foster solidarity and bring us closer together, both within our communities and globally. As clinical psychologist Katie A. McLaughlin from Harvard University pointed out, the pandemic could be “an opportunity for us to become more committed to supporting and helping one another.”

Similarly, sociologist Monika Ardelt from the University of Florida noted the possibility that “we realize these kinds of global events can only be solved if we work together as a world community.” Social identities—such as group memberships, nationality, or those that form in response to significant events such as pandemics or natural disasters—play an important role in fostering collective action. The shared experience of the pandemic could help foster a more global, inclusive identity that could promote international solidarity.

2. Structural and political changes. Early in the pandemic, experts also believed that we might also see proactive efforts and societal will to bring about structural and political changes toward a more just and diversity-inclusive society. Experts observed that the pandemic had exposed inequalities and injustices in our societies and hoped that their visibility might encourage societies to address them.

Philosopher Valerie Tiberius from the University of Minnesota suggested that the pandemic might bring about an “increased awareness of our vulnerability and mutual dependence.”

Fellow of the Royal Institute for International Affairs in the U.K. Anand Menon proposed that the pandemic might lead to growing awareness of economic inequality, which could lead to “greater sustained public and political attention paid to that issue.” Cultural psychologist Ayse Uskul from Kent University in the U.K. shared this sentiment and predicted that this awareness “will motivate us to pick up a stronger fight against the unfair distribution of resources and rights not just where we live, but much more globally.”

3. Renewed social connections. Finally, the most common positive consequence discussed was that we might see an increased awareness of the importance of our social connections. The pandemic has limited our ability to connect face to face with friends and families, and it has highlighted just how vulnerable some of our family members and neighbors might be. Greater Good Science Center founding director and UC Berkeley professor Dacher Keltner suggested that the pandemic might teach us “how absolutely sacred our best relationships are” and that the value of these relationships would be much higher in the post-pandemic world. Past president of the Society of Evolution and Human Behavior Douglas Kenrick echoed this sentiment by predicting that “tighter family relationships would be the most positive outcome of this [pandemic].”

Similarly, Jennifer Lerner—professor of decision-making from Harvard University—discussed how the pandemic had led people to “learn who their neighbors are, even though they didn’t know their neighbors before, because we’ve discovered that we need them.” These kinds of social relationships have been tied to a range of benefits, such as increased well-being and health , and could provide lasting benefits to individuals.

Post-pandemic risks

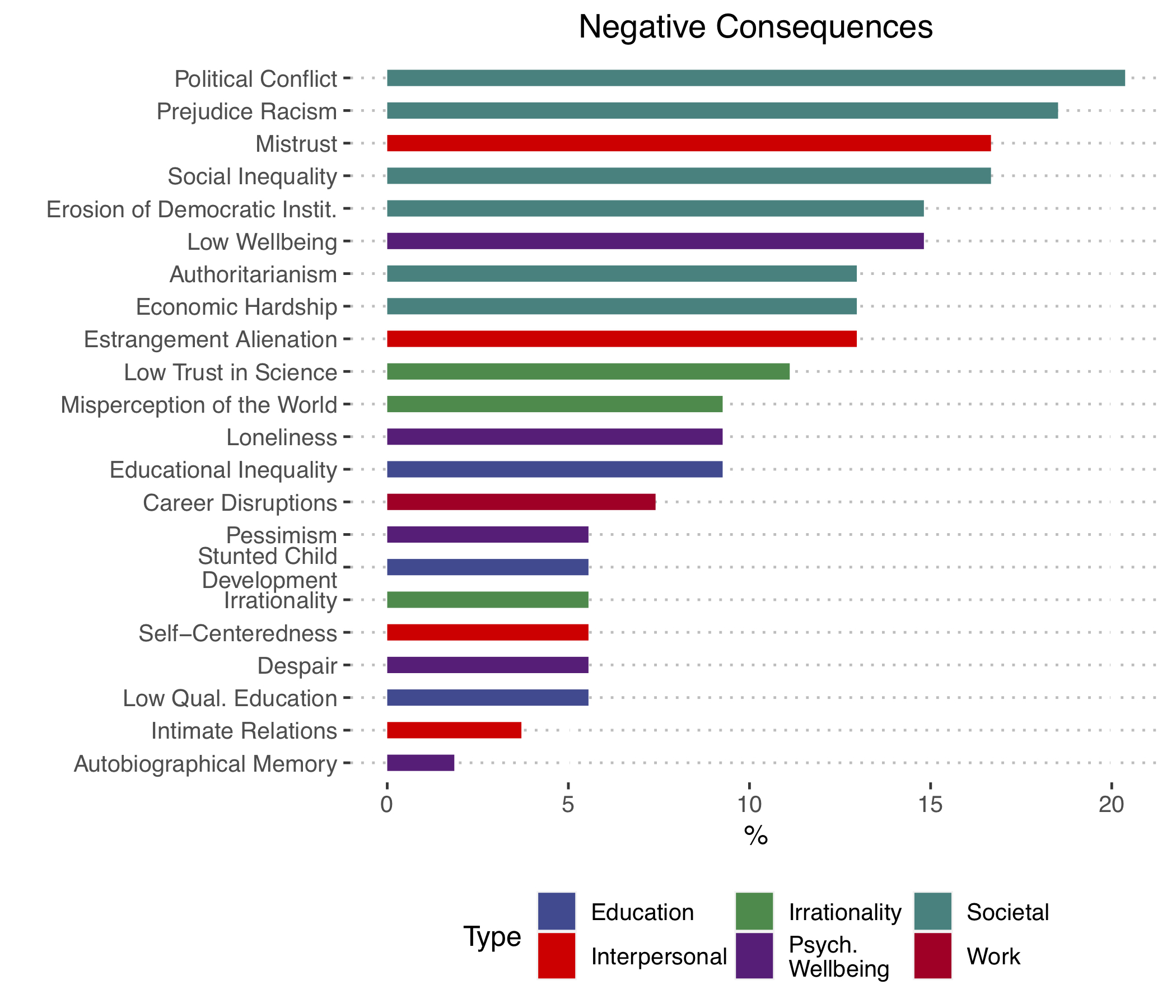

How about predictions for negative consequences of the pandemic? Again, opinions were variable, with more than half of the themes were mentioned by less than 10% of our interviewees. Only two predictions were mentioned by at least ten experts: the potential for political unrest and increased prejudice or racism. These predictions highlight a tension in expert predictions: Whereas some scholars viewed the future bright and “diversity-inclusive,” others fear the rise in racism and prejudice. Before we discuss this tension, let us examine what exactly scholars meant by these two worries.

1. Increased prejudice or racism. Many experts discussed how the conditions brought about by the pandemic could lead us to focus on our in-group and become more dismissive of those outside our circles. Incheol Choi, professor of cultural and positive psychology from Seoul National University, discussed that his main area of concern was that “stereotypes, prejudices against other group members might arise.” Lisa Feldman Barrett, fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and the Royal Society of Canada, echoed this sentiment, noting that previous epidemics saw “people become more entrenched in their in-group and out-group beliefs.”

2. Political unrest. Similarly, many experts discussed how a greater focus on our in-groups might also exacerbate existing political divisions. Past president of the Society for Philosophy and Psychology Paul Bloom discussed how a greater dismissiveness toward out-groups was visible both within countries and internationally, where “countries are blaming other countries and not working together enough.” Dilip Jeste, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, discussed his concerns that the tendency to view both candidates and supporters as winners and losers in elections could mean that the “political polarization that we are observing today in the U.S. and the world will only increase.”

These predictions were not surprising— pundits and other public figures have been discussing these topics, too. However, as we analyzed and compared predictions for positive and negative consequences, we found something unexpected.

The yin and yang of COVID’s effects

Almost half of the interviewees spontaneously mentioned that the same change could be a force for good and for bad . In other words, they were dialectical , recognizing the multidetermined nature of predictions and acknowledging that context matters—context that determines who may be the winners and losers in the years to come. For example, experts predicted that we may see greater acceptance of digital technologies at home and at work. But besides the benefits of this—flexible work schedules, reduced commutes—they also mentioned likely costs, such as missing social information in virtual communication and disadvantages for people who cannot afford high-speed internet or digital devices.

Share Your Perspective

Curious about the world after COVID? So are we, and we'd love your opinion about possible changes ahead. Fill out this short survey to offer your perspective on the hopes and worries of a post-pandemic world.

Amid this complexity, experts weighed in on what type of wisdom we need to help bring about more positive changes ahead. Not only do we need the will to sustain political and structural change, many argued, but also a certain set of psychological strategies promoting sound judgment: perspective taking, critical thinking, recognizing the limits of our knowledge, and sympathy and compassion.

In other words, experts’ recommended wisdom focuses on meta-cognition, which underlies successful emotion regulation, mindfulness, and wiser judgment about complex social issues. The good news is that these psychological strategies are malleable and trainable ; one way we can cultivate wisdom and perspective, for example, is by adopting a third-person, observer perspective on our challenges.

On the surface, the “it depends” attitude of many experts about the world after COVID may be dissatisfying. However, as research on forecasting shows, such a dialectical attitude is exactly what distinguishes more accurate forecasters from the rest of the population. Forecasting is hard and predictions are often uncertain and likely wrong. In fact, despite some hopes for the future, it is equally possible that the change after the pandemic will not even be noticeable. Not because changes will not happen, but because people quickly adjust to their immediate circumstances.

The future will tell whether and how the current pandemic has altered our societies. In the meantime, the World after COVID project provides a time-stamped window into experts’ apartments and their minds. As we embrace another pandemic spring, these insights can serve as a reminder that the pandemic may lead not only to worries but also to hopes for the years ahead.

About the Authors

Igor Grossmann

Igor Grossmann, Ph.D. , studies people and cultures, sometimes together, and often across time. He is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Waterloo, where he directs the Wisdom and Culture Lab.

Oliver Twardus

Oliver Twardus is the lab manager for the Wisdom and Culture lab and an aspiring researcher. He will be starting his master’s in neuroscience and applied cognitive science in September 2021.

You May Also Enjoy

What Will the World Look Like After Coronavirus?

Five Lessons to Remember When Lockdown Ends

Can the Lockdown Push Schools in a Positive Direction?

Five Skills We Need for the Year Ahead

What Will Work Look Like After COVID-19?

Four Reasons Why Zoom Can Be Exhausting

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

- Recommendations

Most Popular

- Republicans ask the Supreme Court to disenfranchise thousands of swing state voters

- Did the Supreme Court just overrule one of its most important LGBTQ rights decisions?

- The Chicago DNC everyone wants to forget

- How the DNC solved its Joe Biden problem

- Why Indian doctors are protesting after the rape and death of a colleague

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Culture

The Innocence Project has taken on Scott Peterson. But there are limits to reasonable doubt.

Our society demands Black women be “twice as good.” Beyoncé has found a solution that Harris seems keen to copy.

On the It Ends With Us press tour, the actor’s persona, side hustles, and career are all in conflict.

The truth behind the ongoing controversy over the highly memeable dancer.

How being labeled “gifted” can rearrange your life — for better and for worse.

The Olympian was asked to give her medal back — and the racist attacks began.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

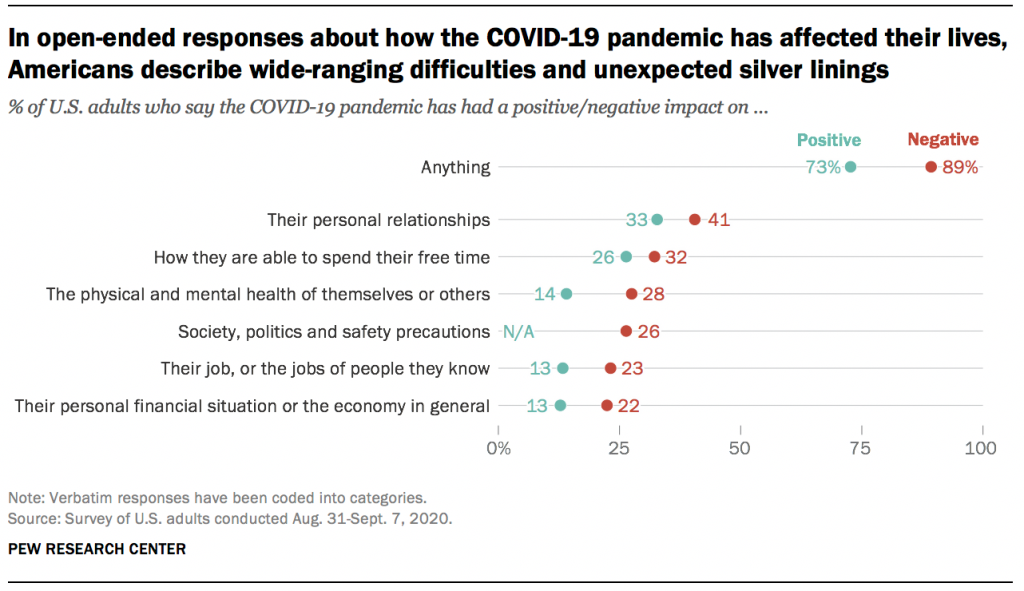

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

How COVID-19 pandemic changed my life

| 4 | |

| 840 | |

| , , , |

Table of Contents

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the biggest challenges that our world has ever faced. People around the globe were affected in some way by this terrible disease, whether personally or not. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, many people felt isolated and in a state of panic. They often found themselves lacking a sense of community, confidence, and trust. The health systems in many countries were able to successfully prevent and treat people with COVID-19-related diseases while providing early intervention services to those who may not be fully aware that they are infected (Rume & Islam, 2020). Personally, this pandemic has brought numerous changes and challenges to my life. The COVID-19 pandemic affected my social, academic, and economic lifestyle positively and negatively.

Social and Academic Changes

One of the changes brought by the pandemic was economic changes that occurred very drastically (Haleem, Javaid, & Vaishya, 2020). During the pandemic, food prices started to rise, affecting the amount of money my parents could spend on goods and services. We had to reduce the food we bought as our budgets were stretched. My family also had to eliminate unhealthy food bought in bulk, such as crisps and chocolate bars. Furthermore, the pandemic made us more aware of the importance of keeping our homes clean, especially regarding cooking food. Lastly, it also made us more aware of how we talked to other people when they were ill and stayed home with them rather than being out and getting on with other things.

Furthermore, COVID-19 had a significant effect on my academic life. Immediately, measures to curb the pandemic were announced, such as closing all learning institutions in the country; my school life changed. The change began when our school implemented the online education system to ensure that we continued with our education during the lockdown period. At first, this affected me negatively because when learning was not happening in a formal environment, I struggled academically since I was not getting the face-to-face interaction with the teachers I needed. Furthermore, forcing us to attend online caused my classmates and me to feel disconnected from the knowledge being taught because we were unable to have peer participation in class. However, as the pandemic subsided, we grew accustomed to this learning mode. We realized the effects on our performance and learning satisfaction were positive, as it seemed to promote emotional and behavioral changes necessary to function in a virtual world. Students who participated in e-learning during the pandemic developed more ownership of the course requirement, increased their emotional intelligence and self-awareness, improved their communication skills, and learned to work together as a community.

If there is an area that the pandemic affected was the mental health of my family and myself. The COVID-19 pandemic caused increased anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns that were difficult for my family and me to manage alone. Our ability to learn social resilience skills, such as self-management, was tested numerous times. One of the most visible challenges we faced was social isolation and loneliness. The multiple lockdowns made it difficult to interact with my friends and family, leading to loneliness. The changes in communication exacerbated the problem as interactions moved from face-to-face to online communication using social media and text messages. Furthermore, having family members and loved ones separated from us due to distance, unavailability of phones, and the internet created a situation of fear among us, as we did not know whether they were all right. Moreover, some people within my circle found it more challenging to communicate with friends, family, and co-workers due to poor communication skills. This was mainly attributed to anxiety or a higher risk of spreading the disease. It was also related to a poor understanding of creating and maintaining relationships during this period.

Positive Changes

In addition, this pandemic has brought some positive changes with it. First, it had been a significant catalyst for strengthening relationships and neighborhood ties. It has encouraged a sense of community because family members, neighbors, friends, and community members within my area were all working together to help each other out. Before the pandemic, everybody focused on their business, the children going to school while the older people went to work. There was not enough time to bond with each other. Well, the pandemic changed that, something that has continued until now that everything is returning to normal. In our home, it strengthened the relationship between myself and my siblings and parents. This is because we started spending more time together as a family, which enhanced our sense of understanding of ourselves.

The pandemic has been a challenging time for many people. I can confidently state that it was a significant and potentially unprecedented change in our daily life. By changing how we do things and relate with our family and friends, the pandemic has shaped our future life experiences and shown that during crises, we can come together and make a difference in each other’s lives. Therefore, I embrace wholesomely the changes brought by the COVID-19 pandemic in my life.

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Current medicine research and practice , 10 (2), 78.

- Rume, T., & Islam, S. D. U. (2020). Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability. Heliyon , 6 (9), e04965.

- ☠️ Assisted Suicide

- Affordable Care Act

- Breast Cancer

- Genetic Engineering

- PERSPECTIVES

- SUBMIT A PERSPECTIVE

- A NEW MAP OF LIFE

THE NEW MAP OF LIFE

AFTER THE PANDEMIC

It is said that culture is like the air we breathe. We don’t notice it until it’s gone.

The COVID-19 pandemic is bringing into focus a once invisible culture that guides us through life. Seemingly overnight, we experienced profound changes in the ways that we work, socialize, learn, and engage with our neighborhoods and larger communities.

For a short time, before new routines and practices replace familiar old ones, we can see with greater clarity the positive and negative aspects of our former lives. The suddenness and starkness of this transformation allows us to examine daily practices, social norms and institutions from perspectives rarely allowed.

The fragility of the global economy becomes glaringly apparent as critical supply chains faulter, unemployment surges, and markets vacillate. Tacit assumptions about health care systems become clear as we see how they function, fail to function, and have long underserved large parts of the population. Just as sure, sheltering in place allows us to appreciate precious details of our lives that we have taken for granted: the appeal of workplaces, the comfort of human touch, dinner parties, travel, and paychecks. Indeed, through ambivalent eyes we also recognize ways that life is better as we shelter in place.

The premise of the New Map of Life:™ After the Pandemic project is that we have a fleeting window of time that affords us an unprecedented opportunity to examine our lives. Going forward, life will be different and by compiling the insights we have today we can inform and guide the culture that will inevitably emerge from our collective experience. Your insights can contribute to the reshaping of social norms, systems, and practices that shape our collective futures.

Since the founding of the Stanford Center on Longevity, we have advocated for a major redesign of life that better supports century-long lives. More recently, we undertook the New Map of Life ™ initiative, which focuses on envisioning a world where people experience a sense of purpose, belonging, and worth at all stages of life. As tragedies unfold before our eyes, we aim to capture the lessons they teach. With your help, we can compile current insights, fleeting thoughts and deeper reflections about the ways we live now so that going forward we bolster, modify and reinvent cultures that improve quality of life for ourselves, our children, and future generations.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the various authors on this website do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of the Stanford Center on Longevity or official policies of the Stanford Center on Longevity.

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

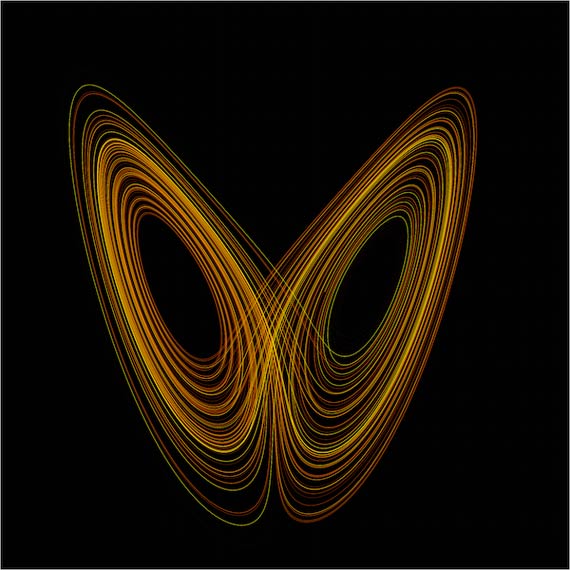

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- Heman Bekele Is TIME’s 2024 Kid of the Year

- The Reintroduction of Kamala Harris

- A Battle Over Fertility Law in China

- For the Love of Savoring Sandwiches : Column

- The 1 Heart-Health Habit You Should Start When You’re Young

- Cuddling Might Help You Get Better Sleep

- The 50 Best Romance Novels to Read Right Now

Contact us at [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Beyond the pandemic: The truth of life after COVID-19

This study focused on how to deal with the psychological trauma from the perspective of a doctor on the front line of the fight against COVID-19. As the pandemic continues to ravage our world, post-pandemic psychological counseling urgently needs to be addressed. Based on the experience of fighting the epidemic, this study discusses the psychological changes since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. Taking a 19-year-old with breast cancer as an example, this study considered how to find spiritual comfort, and examined how to find meaning in today's complicated world and lives, as well as turning the crisis into an opportunity for spiritual renewal and adding meaning to our lives. It is hoped that this study will inspire readers to overcome the difficulties of the epidemic, find strength and see it as a life-changing opportunity.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic is in its third year. China has been battling the outbreak since early 2020. 1 To date, we are still fighting SARS-Cov-2 and the Omicron variants on multiple fronts. 2 The dramatic changes brought about by COVID-19 have affected every aspect of people's lives. Some of the measures to control the epidemic, including isolation, access restrictions and economic shutdowns, radically changed psychosocial behavior, and induced psychological trauma, especially China's strict prevention and control policies have affected large numbers of people. Nevertheless, there is a lack of timely research on post-pandemic trauma and psychological counseling. 3 Here, I would like to share some thoughts about the trauma under the epidemic from the viewpoint of an infectious disease specialist. It is hoped this will inspire readers and help them overcome psychological trauma and bring a new perspective on life in the post-pandemic era.

Trauma haunts many people and psychological counseling is urgent