Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Evidence-Based Teaching for the 21st Century Classroom and Beyond pp 77–120 Cite as

Learning Interventions: Collaborative Learning, Critical Thinking and Assessing Participation Real-Time

- Kumaran Rajaram 2

- First Online: 17 March 2021

1186 Accesses

This chapter focuses on the authentic learning interventions for team-based and flipped classroom collaborative learning that assesses real-time class participation which develops competency and employability skills set. The discussions address the process in achieving the intended learning outcomes with the adoption of these learning interventions. It provides evidence-based results in terms of how these learning interventions facilitate effective learning in terms of higher-order critical thinking (refers to the process of thinking is made intensive through scaffolding approach that potentially enables learners to question and reflect deeply), deeper engagement amongst students (refers to the ability for students to be motivated and their involvement through listening and/or participation is much more spontaneous) and higher level of collaboration at inter- and intra-group levels (refers to much more interactivity, team-based involvement in engaging within the team members and/or across members of another group). Collaborative learning is generally defined as a situation in which two or more people learn or attempt to learn something together (Dillenbourg in Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches 1:1–15, 1999), whereas in a cooperative learning context, individuals work together to optimize, maximize their own and each other’s learning to attain shared goals. Largely, there are three categories of cooperative learning namely informal cooperative learning groups, formal cooperative learning groups and cooperative base groups. In our context, informal cooperative learning was focused on. In accordance with research scholars (Johnson et al. in Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 30(4):26–35, 1998a; Johnson et al. in Cooperation in the classroom , Interaction Book Company, Edina, MN, 1998b), informal cooperative learning entails students working together to achieve common learning goal in temporary, ad-hoc groups that last from a few minutes to one class period. In a meta-analysis performed by Johnson et al. (Johnson et al. in Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 30(4):26–35, 1998a), studies since 1924 were reviewed and it was found that when students learn together, academic achievement is enhanced. Moreover, students were found to have higher self-esteem and better quality of relationships (Johnson et al. in Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 30(4):26–35, 1998a). The functionalities offered within the learning interventions and support systems fundamentally promote collaboration. Student engagement is correlated with participation in public service, self-reported learning gains, increased student achievement (Carini et al. in Research in Higher Education 47:1–32, 2006) and job engagement (Busteed & Seymour in Gallup Business Journal 19, 2015). The goal of the learning interventions is to maximize student engagement in meaningful learning activities within classroom settings. When students engage in more meaningful learning activities, they are actively learning. DeLozier and Rhodes (DeLozier & Rhodes in Educational Psychology Review 29:141–151, 2017) believed that it is the active learning in class that is responsible for the enhancement in learning performances. The use of learning interventions also increases the number of students participating in meaningful learning activities through providing the quieter students in class an alternative avenue of input other than speaking up in front of the class. Cain and Klein ( Independent School 75(1):64–71, 2015) found in their study that quiet students indeed feel more comfortable sharing their ideas online. Moreover, shy and quiet students contribute more through synchronous online discussion than in regular classroom discussion (Warschauer in CALICO Journal , 7–26, 2015). Lastly, with the synchronous online discussion feature of the activity support system and the organized class activity sequences, it is expected that there will be a reduction in time used for transitions between activities, introductions to activities, and disruptions within activities. Both collaborative learning, through “discussion, clarification of ideas, and evaluation of others’ ideas” (Gokhale in Journal of Technology Education 7:22–30, 1995), and high student engagement (Carini et al. in Research in Higher Education 47:1–32, 2006) enhance the development of critical thinking. It was also argued that critical thinking can be learnt through every interaction (MacKnight in Educause Quarterly 23:38–41, 2000) provided the interaction is supported with specific critical thinking activities (Astleitner in Journal of Instructional Psychology 29:53, 2002; Kim in Interactive Learning Environments 22:467–484, 2014; Weltzer-Ward & Carmona in International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 3:86–88, 2008). Therefore, our learning interventions and supports systems, which enhances students’ engagement and collaborative learning, would also lead to a desirable development of students’ critical thinking ability. The chapter will also describe the varying functionalities and the process of how the learning interventions enable the intended learning outcomes to be achieved. This chapter also furnishes the relevant video and training resources that are developed for the learning interventions. The findings from the surveys and interviews serve as evidence based to validate the discussions that emerge from the analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Alavi, M. (1994). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: An empirical evaluation. MIS quarterly , 159–174.

Google Scholar

Anthony, S., & Garner, B. (2016). Teaching soft skills to business students: An analysis of multiple pedagogical methods. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 79 (3), 360–370.

Article Google Scholar

Arbaugh, J. B., & Benbunan-Finch, R. (2006). An investigation of epistemological and social dimensions of teaching in online learning environments. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5 (4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2006.23473204 .

Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing stereotype threat and boosting academic achievement of African-American students: The role of conceptions of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 113–125.

Astleitner, H. (2002). Teaching critical thinking online. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 29 (2), 53.

Bedwell, W. L., Fiore, S. M., & Salas, E. (2014). Developing the future workforce: An approach for integrating interpersonal skills into the MBA classroom. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 13 (2), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2011.0138 .

Bergmark, U., & Westman, S. (2016). Co-creating curriculum in higher education—Promoting democratic values and a multidimensional view on learning. International Journal for Academic Development, 21 (1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1120734 .

Bergmark, U., & Westman, S. (2018). Student participation within teacher education: Emphasising democratic values, engagement and learning for a future profession. Higher Education Research & Development, 37 (7), 1352–1365.

Bovill, C., & Bulley, C. J. (2011). A model of active student participation in curriculum design: Exploring desirability and possibility. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning. Global theories and local practices: Institutional, disciplinary and cultural variations (pp. 176–188). Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Staff and Educational Development.

Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes were overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28 (1), 31–44.

Britain, S. (2004). A review of learning design: Concept, specifications and tools . A report for the JISC E-learning Pedagogy Programme. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/elearningpedagogy/learningdesigntoolsfinalreport.pdf .

Busteed, B., & Seymour, S. (2015). Many college graduates not equipped for workplace success. Gallup Business Journal , 19.

Cain, S., & Klein, E. (2015). Engaging the quiet kids. Independent School, 75 (1), 64–71. Retrieved from https://www.nais.org/magazine/independent-school/fall-2015/engaging-the-quiet-kids/ .

Carey, P. (2013). Student as co-producer in a marketized higher education system: A case study of students’ experience of participation in curriculum design. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50 (3), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.796714 .

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47 (1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9 .

Caspi, A., Chajut, E., Saporta, K., & Beyth-Marom, R. (2006). The influence of personality on social participation in learning environments. Learning and Individual Differences, 16 (2), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2005.07.003 .

Clay, T., & Breslow, L. (2006, April 14). Why students don’t attend class. Retrieved from https://web.mit.edu/fnl/volume/184/breslow.html .

Coller, B. D., & Scott, M. J. (2009). Effectiveness of using a video game to teach a course in mechanical engineering. Computers & Education, 53 (3), 900–912.

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in teaching and learning: A guide for faculty . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Crossan, M., Mazutis, D., Seijts, G., & Gandz, J. (2013). Developing leadership character in business programs. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12 (2), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2011.0024a .

Dalziel, J. (2003). Implementing learning design: The Learning Activity Management System (LAMS), interact, integrate, impact . Proceedings of the 20th annual conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE).

Dalziel, J. (2014, December 9). LAMS Newsletter 115 . Retrieved from https://lamscommunity.org/dotlrn/clubs/educationalcommunity/forums/message-view?message_id=1891728 .

De Leng, B. A., Dolmans, D. H., Jöbsis, R., Muijtjens, A. M., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2009). Exploration of an e-learning model to foster critical thinking on basic science concepts during work placements. Computers & Education, 53 (1), 1–13.

Delcker, J., Honal, A., & Ifenthaler, D. (2017). Mobile device usage in university and workplace learning settings . Paper presented at the ACET 2017. Jacksonville, FL.

DeLozier, S. J., & Rhodes, M. G. (2017). Flipped classrooms: A review of key ideas and recommendations for practice. Educational Psychology Review, 29 (1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9356-9 .

Desiraju, R., & Gopinath, C. (2001). Encouraging participation in case discussions: A comparison of the mica and the Harvard case methods. Journal of Management Education, 25 (4), 394–408.

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). What do you mean by collaborative learning? Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches, 1, 1–15.

Elise, J. D., Julie, H. H., & Marjorie, B. P. (2006). Nonvoluntary class participation in graduate discussion courses: Effects of grading and cold calling. Journal of Management Education, 30 (2), 354–377.

Erikson, M. G., & Erikson, M. (2018). Learning outcomes and critical thinking—Good intentions in conflict. Studies in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1486813 .

Falchikov, N., & Boud, D. (1989). Student self-assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 59 , 395–430.

Fallows, S., & Steven, C. (2000). Building employability skills into the higher education curriculum: A university-wide initiative. Education + Training, 42 (22), 75–83.

Farmer, K., Meisel, S. I., Seltzer, J., & Kane, K. (2013). The mock trial: A dynamic exercise for thinking critically about management theories, topics, and practices. Journal of Management Education, 37 (3), 400–430.

Fellenz, M. R. (2006). Toward fairness in assessing student groupwork: A protocol for peer evaluation of individual contributions. Journal of Management Education, 30 (4), 570–591.

Finkel, E. J., Slotter, E. B., Luchies, L. B., Walton, G. M., & Gross, J. J. (2013). A brief intervention to promote conflict reappraisal preserves marital quality over time. Psychological Science , 1595–1601.

Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement , 97–131, Springer.

Freeman, M., Blayney, P., & Ginns, P. (2006). Anonymity and in class learning: The case for electronic response systems. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 22 (4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1286 .

Ghanizadeh, A. (2017). The Interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research, 74 (1), 101–114.

Ghorpade, J., & Lackritz, J. R. (2001). Peer evaluation in the classroom: A check for sex and race/ethnicity effects. Journal of Education For Business, 75 (5), 274–281.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7 (1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_910 .

Gopinath, C. (1999). Alternatives to instructor assessment of class participation. Journal of Education for Business, 75 (1), 10–14.

Hemmi, A., Bayne, S., & Land, R. (2009). The appropriation and repurposing of social technologies in higher education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25 (1), 19–30.

Hoegl, M., & Gemuenden, H. G. (2001). Teamwork quality and the success of innovative projects: A theoretical concept and empirical evidence. Organisation Science, 12 (4), 435–449.

Hulleman, C. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2009). Promoting interest and performance in high school science classes. Science, 326 (5958), 1410–1412.

Hwang, A., & Francesco, A. (2010). The influence of individualism—Collectivism and power distance on use of feedback channels and consequences for learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 9 (2), 243–257.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Holubec, E. J. (1998b). Cooperation in the classroom . Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1998a). Cooperative learning returns to college what evidence is there that it works? Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 30 (4), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091389809602629 .

Kim, I.-H. (2014). Development of reasoning skills through participation in collaborative synchronous online discussions. Interactive Learning Environments, 22 (4), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2012.680970 .

Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. (2014). Technology-enhanced learning and teaching in higher education: What Is “enhanced” and how do we know? A critical literature review. Learning, Media and Technology, 39 (1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.770404 .

Kordaki, M., & Agelidou, E. (2010). A learning design-based environment for online, collaborative digital storytelling: An example for environmental education. International Journal of Learning, 17 (5), 95–106.

Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we’re learning about student engagement from NSSE: Benchmarks for effective educational practices. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 35 (2), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091380309604090 .

Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. M. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 486–490.

Laird, T. F. N., & Kuh, G. D. (2005). Student experiences with information technology and their relationship to other aspects of student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 46 (2), 211–233.

Latham, A., & Hill, N. S. (2014). Preference for anonymous classroom participation: Linking student characteristics and reactions to electronic response systems. Journal of Management Education, 38 (2), 192–215.

LAMS Foundation. (2004, January 05). Learning activity management system . Available online at https://www.lamsfoundation.org/about_home.htm .

LAMS Foundation. (2012, March 22). Who is using LAMS? Retrieved from https://wiki.lamsfoundation.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=2855 .

Levy, P., Aiyegbayo, O., & Little, S. (2009). Designing for inquiry-based learning with the learning activity management system. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25 (3), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2008.00309.x .

Lizzio, A., & Wilson, K. (2009). Student participation in university governance: The role conceptions and sense of efficacy of student representatives on departmental committees. Studies in Higher Education, 34 (1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802602000 .

Logel, C., & Cohen, G. L. (2012). The role of the self in physical health testing the effect of a values-affirmation intervention on weight loss. Psychological Science, 23, 53–55.

Mabrito, M. (2006). A study of synchronous versus asynchronous collaboration in an online business writing class. The American Journal of Distance Education, 20 (2), 93–107.

MacKnight, C. B. (2000). Teaching critical thinking through online discussions. Educause Quarterly, 23 (4), 38–41.

Mainkar, A. V. (2007). A student-empowered system for measuring and weighing participation in class discussion. Journal of Management Education, 32 (1), 23–37.

Masika, R., & Jones, J. (2016). Building student belonging and engagement: Insights into higher education students’ experiences of participating and learning together. Teaching in Higher Education, 21 (2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1122585 .

McGlynn, A. P. (2005). Teaching millennials, our newest cultural cohort. Education Digest, 71 (4), 12.

McKeachie, W. (1994). Teaching tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher (9th ed.). Lexington, MA: Heath.

McLeod, J. (2011). Student voice and the politics of listening in higher education. Critical Studies in Education, 52 (2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2011.572830 .

Melvin, K. B. (1998). Rating class participation. The Teaching of Psychology, 15, 137–139.

Melvin, K. B., & Lord, A. T. (1995). The prof/peer method of evaluating class participation: Interdisciplinary generality. College Student Journal, 29, 258–263.

Ohland, M., Loughry, M., Woehr, D., Bullard, L., Felder, R., Finelli, C., & Schmucker, D. (2012). The comprehensive assessment of team member effectiveness: Development of a behaviorally anchored rating scale for self-and peer evaluation. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 11 (4), 609–630.

Panitz, T. (1999). Benefits of cooperative learning in relation to student motivation. In M. Theall (Ed.), Motivation from within: Approaches for encouraging faculty and students to excel, New directions for teaching and learning . San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass Publishing.

Paulhus, D. L., Duncan, J. H., & Yik, M. S. M. (2002). Patterns of shyness in East-Asian and European-heritage students. Journal of Research in Personality, 36 (5), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00005-3 .

Philip, R., & Dalziel, J. (2004). Designing activities for student learning using the learning activity management system (LAMS) . Paper presented at the International Conference on Computers in Education.

Rajaram, K. (2013). Learning in foreign cultures: Self-reports learning effectiveness across different instructional techniques. World Journal of Education, 3 (4), 71.

Rajaram, K. (2020). Educating mainland chinese learners in business education, pedagogical and cultural perspectives – Singapore experiences . Springer.

Rogers, W. T., 1993. Principles for Fair Student Assessment Practices for Education in Canada. Canadian Journal of School Psychology , 110–127.

Roohr, K., et al. (2019). A multi-level modeling approach to investigating students’ critical thinking at higher education institutions. Journal of Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education., 46 (6), 946–960.

Rossiou, E. R. U. G. (2012). Digital natives...are changed: An educational scenario with LAMS integration that promotes collaboration via blended learning in secondary education. Proceedings of the European Conference on e-Learning , 468–479.

Sally, B. (2005). Assessment for learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 81–89. ISSN 1742–240X.

Seale, J. (2010). Doing student voice work in higher education: An exploration of the value of participatory methods. British Educational Research Journal, 36 (6), 995–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903342038 .

Serva, M. A., & Fuller, M. A. (2004). Aligning what we do and what we measure in business schools: Incorporating active learning and effective media use in the assessment of instruction. Journal of Management Education, 28, 19–38.

Sherrard, W. R., Raafat, F., & Weaver, R. R. (2010). An empirical study of peer bias in evaluations: Students rating students. the Journal of Education for Business, 70 (1), 43–47.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85 (4), 571.

Smith, G. F. (2014). Assessing business student thinking skills. Journal of Management Education, 38 (3), 384–411.

Thomas, M. J. (2002). Learning within incoherent structures: The space of online discussion forums. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18 (3), 351–366.

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87 (2), 246.

Walton, G. M. (2014). The new science of wise psychological interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23 (1), 73–82.

Warschauer, M. (1995). Comparing face-to-face and electronic discussion in the second language classroom. CALICO Journal , 7–26.

Weltzer-Ward, L. M. L. W. N. E., & Carmona, G. L. M. U. E. (2008). Support of the critical thinking process in synchronous online collaborative discussion through model-eliciting activities. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 3 (3), 86–88.

Yasushi, G. (2016). Development of critical thinking with metacognitive regulation. 13th International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age , 353–356.

Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81 (2), 267–301.

Zepke, N. (2015). Student engagement research: Thinking beyond the mainstream. Higher Education Research & Development, 34 (6), 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1024635 .

Zepke, N. (2018). Student engagement in neo-liberal times: What is missing? Higher Education Research & Development , 37 (2). https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1370440 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The above two research studies were funded by Nanyang Technological University (NTU) through the NTU Educational Excellence Grants. The author would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for providing valuable feedback and guidance.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Kumaran Rajaram

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kumaran Rajaram .

Appendix A: Post-Survey (After the Intervention of the Learning Support System)

3.1.1 survey questions.

The experience of using “K^mAlive” in this class is ___________________.

Very Positive

Somewhat Positive

Very Negative

What are your thoughts and feelings about your contributions in class being captured?

____________________________________________________________

The use of “K^mAlive” in this class is a/an _________ way to encourage my participation in class.

Very Effective

Somewhat Effective

Ineffective

Very Ineffective

What are your thoughts in terms of the impact of class participation through the adoption of K^mAlive?

The use of “K^mAlive” in this class motivates me to listen more attentively to my classmates’ contributions in class.

Strongly Agree

Strongly Disagree

The use of “K^mAlive” in this class developed my critical thinking abilities.

If you have answered “Strongly Agree/Agree” to question 5, can you explain how the use of “K^mAlive” has enhanced your critical thinking skills?

I believe the use of “K^mAlive” in this course gives a fair assessment of my participation in class.

What are your thoughts and feelings regarding the grading of your participation in class using “K^mAlive”?

What do you like the best about the experience of using “K^mAlive” in class? Please explain why.

What would you like to change about the experience of the usage of “K^mAlive” in class? Please explain why.

Any other comments?

Appendix B: Interview Questions

What are your experiences of using this real-time learning support system—K^mAlive?

How does it explicitly enhance (a) higher levels of class participation; (b) make you think more critically; (c) better engagement with your peers in your group and others in the class

What are your overall perspectives of the features offered in this learning intervention—K^mAlive on how it supports your learning process and how do you learn?

Appendix C: Video Resources

Value Proposition of Learning Support System: K^mAlive (5 min)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZOpR4fWL0s

Value Proposition of Learning Support System: K^mAlive (20 min)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjDQcbq84V4

Operational Guide: K^mAlive

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O0Iv0q1IdiM

The video trailers with supporting illustrations could also be viewed in the furnished links:

K^mAlive Learning Blog Site: https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/learning-innovations/kumalive/

Research Lab for Learning Innovation and Culture of Learning: https://learningintervention.wixsite.com/researchlab/klive

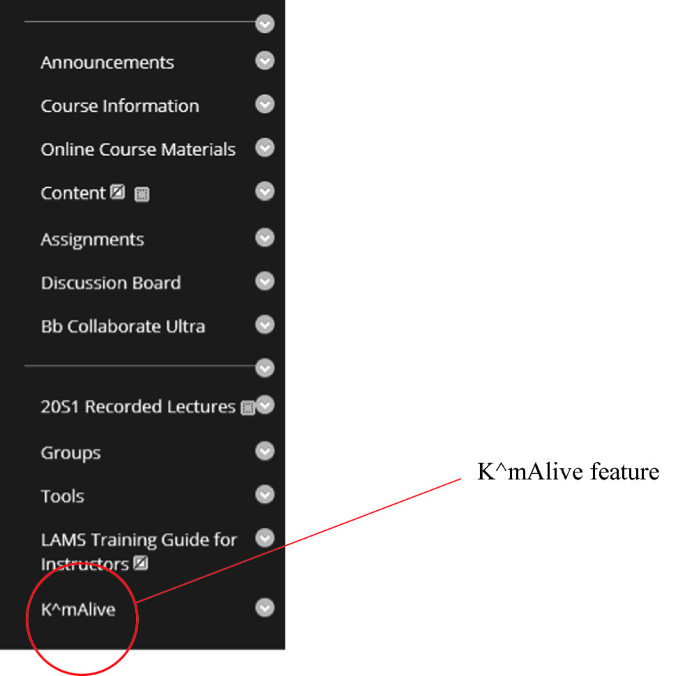

Appendix D: Screen Shot of K^mAlive Feature Embedded with NTULearn (Blackboard)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Rajaram, K. (2021). Learning Interventions: Collaborative Learning, Critical Thinking and Assessing Participation Real-Time. In: Evidence-Based Teaching for the 21st Century Classroom and Beyond. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6804-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6804-0_3

Published : 17 March 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-33-6803-3

Online ISBN : 978-981-33-6804-0

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Essential Learning Outcomes: Critical/Creative Thinking

- Civic Responsibility

- Critical/Creative Thinking

- Cultural Sensitivity

- Information Literacy

- Oral Communication

- Quantitative Reasoning

- Written Communication

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Description

Guide to Critical/Creative Thinking

Intended Learning Outcome:

Analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in order to consider problems/ideas and transform them in innovative or imaginative ways (See below for definitions)

Assessment may include but is not limited to the following criteria and intended outcomes:

Analyze problems/ideas critically and/or creatively

- Formulates appropriate questions to consider problems/issues

- Evaluates costs and benefits of a solution

- Identifies possible solutions to problems or resolution to issues

- Applies innovative and imaginative approaches to problems/ideas

Synthesize information/ideas into a coherent whole

- Seeks and compares information that leads to informed decisions/opinions

- Applies fact and opinion appropriately

- Expands upon ideas to foster new lines of inquiry

- Synthesizes ideas into a coherent whole

Evaluate synthesized information in order to transform problems/ideas in innovative or imaginative ways

- Applies synthesized information to inform effective decisions

- Experiments with creating a novel idea, question, or product

- Uses new approaches and takes appropriate risks without going beyond the guidelines of the assignment

- Evaluates and reflects on the decision through a process that takes into account the complexities of an issue

From Association of American Colleges & Universities, LEAP outcomes and VALUE rubrics: Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion.

Creative thinking is both the capacity to combine or synthesize existing ideas, images, or expertise in original ways and the experience of thinking, reacting, and working in an imaginative way characterized by a high degree of innovation, divergent thinking, and risk taking.

Elements, excerpts, and ideas borrowed with permission form Assessing Outcomes and Improving Achievement: Tips and tools for Using Rubrics , edited by Terrel L. Rhodes. Copyright 2010 by the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

How to Align - Critical/Creative Thinking

- Critical/Creative Thinking ELO Tutorial

Critical/Creative Thinking Rubric

Analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in order to consider problems/ideas and transform them into innovative or imaginative ways.

Elements, excerpts, and ideas borrowed with permission form Assessing Outcomes and Improving Achievement: Tips and tools for Using Rubrics , edited by Terrel L. Rhodes. Copyright 2010 by the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Sample Assignments

- Cleveland Museum of Art tour (Just Mercy) Assignment contributed by Chris Wolken, Matt Lafferty, Luke Schuleter and Sara Clark.

- Disaster Analysis This assignment was created by faculty at Durham College in Canada The purpose of this assignment is to evaluate students’ ability to think critically about how natural disasters are portrayed in the media.

- Laboratory Report-Critical Thinking Assignment contributed by Anne Distler.

- (Re)Imaginings assignment ENG 1020 Assignment contributed by Sara Fuller.

- Sustainability Project-Part 1 Waste Journal Assignment contributed by Anne Distler.

- Sustainability Project-Part 2 Research Assignment contributed by Anne Distler.

- Sustainability Project-Part 3 Waste Journal Continuation Assignment contributed by Anne Distler.

- Sustainability Project-Part 4 Reflection Assignment contributed by Anne Distler.

- Reconstructed Landscapes (VCPH) Assignment contributed by Jonathan Wayne

- Book Cover Design (VCIL)) Assignment contributed by George Kopec

Ask a Librarian

- << Previous: Civic Responsibility

- Next: Cultural Sensitivity >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tri-c.edu/Essential

Learning outcomes and critical thinking – good intentions in conflict

695 citations

34 citations

27 citations

View 1 citation excerpt

Cites background from "Learning outcomes and critical thin..."

... …materials such as those stored on a computer so that they can be accessed by teachers and students whenever and wherever, and the use of lesson schedules, curricula, learning outcomes, and other matters related to educational administration that can be viewed on computers (Erikson & Erikson, 2019). ...

20 citations

13,211 citations

12,926 citations

View 1 reference excerpt

"Learning outcomes and critical thin..." refers background in this paper

... This amalgamation of disciplinary and pedagogical competence is what Shulman (1987) labelled pedagogical content matter. ...

6,414 citations

... Considering how important assumptions about students’ understanding are in the arguments for constructive alignment expressed by, for example, Biggs and Tang (2011), the critique offered by Hussey and Smith (2002) and others – developed further in the present analysis – call for empirical investigation. ...

1,076 citations

1,045 citations

... These dispositions include both the ability to distinguish situations that call for critical thinking and the motivation to actually think critically in those situations (e.g. Facione 2000; Giancarlo and Facione 2001; Halpern 1998). ...

Related Papers (5)

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Contributing institutions

Related topics

- Skip to main content

- Skip to quick search

- Skip to global navigation

- Return Home

- Recent Issues (2021-)

- Back Issues (1982-2020)

- Search Back Issues

Improving Students’ Critical Thinking Outcomes: An Process-Learning Strategy in Eight Steps

Permissions : This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy .

This article describes an eight-step strategy through which students learn to critically analyze situations that they have encountered in their clinical practice. The method was derived from Stephen Brookfield’s four components of critical thinking and his suggestions for themes that relate to nursing culturalization. The approach used to develop this model has implications for educators in all fields because it illustrates a method for integrating the learning of critical thinking processes with their real-world applications.

Although educators in all disciplines share a general interest in developing students’ ability to think critically, nurse educators are especially challenged because they must prepare their students to perform technical; interpersonal, and critical thinking skills simultaneously. They must learn to function as safe, competent, and skillful clinical nurse practitioners in a complex health care environment in which new information and new clinical situations continually emerge (del Bueno, 1990; Miller & Malcolm,1990).

In 1988, the U. S. Department of Education issued a mandate that required accrediting agencies to consider evidence of educational outcomes when conducting program reviews (U. S. Department of Education, 1988). As a result, nursing education’s accrediting agency, the National League for Nursing (NLN), changed its accreditation criteria to include five required outcomes, including critical thinking, in Baccalaureate and Higher Degree Programs (National League for Nursing, 1991). As defined by the NLN, critical thinking should reflect student skills in reasoning, analysis, research, or decision making relevant to the discipline of nursing (National League for Nursing, 1992). In addition to these developments, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a list of national health promotion and disease prevention objectives that supported the need to balance nursing education’s program content and learning strategies (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1992).

These factors provided the impetus for the authors’ development of a process-focused critical thinking strategy. The authors’ employment setting is a baccalaureate nursing program with over 500 nursing student majors, located in an urban area of the Southeastern region of the country. Students participating in the critical thinking activity selected acute cardiology nursing for their clinical learning setting in a nursing synthesis course. The cardiology nursing unit is located in a large urban regional medical center complex.

Conceptual Framework

In his 1987 book on developing critical thinkers, Stephen Brookfield posited four components of critical thinking: (1) identifying and challenging assumptions; (2) challenging the importance of context; (3) imagining and exploring alternatives; (4) reflective skepticism. More recently, Brookfield (1993) also suggested a “phenomenography of nurses as critical thinkers” to account for how nurses learn and experience critical thinking. Each of these culturalization themes has important implications for anyone who practices critical thinking in the field of nursing (and, potentially, many other professional fields): impostership, cultural suicide, lost innocence, roadrunning, and community. Because these themes are less widely known than Brookfield’s components of critical thinking, they require some elaboration. A complete exploration of these themes is beyond the scope of this article, but brief definitions, based on Brookfield (1993), follows.

“Impostorship,” common to many professionals, is a feeling of underlying incompetence that often does not diminish with years of practice. Imposters must always appear to know what they are doing and they live in fear that they will be “exposed” for the hopeless incompetents that really are. “Cultural suicide” refers to a kind of cultural alienation that can result when critically aware nurses question their colleagues who are less critically aware: … nurses who expect their efforts to ignite a fire of enthusiasm for critical reflection and democratic experimentation may be sorely disappointed when they find themselves regarded as uncooperative subversives (and) whistleblowers … (p. 201). The theme of “lost innocence” relates to the often sad discovery that there are no perfect, unchanging models of clinical practice, but only ‘‘the contextual ambiguity of practice” (p. 203). “Roadrunning” (inspired by the Warner Brothers cartoon) describes the state of limbo that occurs in the process of critical thinking when “we realize that the old ways of thinking and acting no longer make sense, but … new ones have not yet formed to take their place” (p. 204). Brookfield explores this theme in the context of the rhythm and pace of the epistimologic, transformational process of critical thinking. “Community” is a more positive and hopeful theme that relates to the development of “emotionally sustaining peer groups” that may consist of just four or five good friends who “know that experiencing dissonance, challenging assumptions, taking new perspectives, and falling foul of conservative administrators are generic aspects of the critical process, not idiosyncratic events” (p. 205).

Brookfield’s four components of critical thinking and his culturalization themes provided the conceptual framework for the authors’ eight-step learning strategy for critical thinking. The process is initiated in Step One by the examination of a critical incident (a real-life situation) in nursing care. Steps Three, Four, Five, and Six incorporate Brookfield’s four components of critical thinking, and his culturalization themes involve Steps Two and Seven. In Step Eight students explore the usefulness of critical incidents as a means of achieving their’ learning outcomes.

The Eight-Step Process: Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice

Step one: identify a critical incident.

In Step One students first identify critical incidents they encountered during clinical practice. As Brookfield (1993) advises, students are instructed to think about episodes in which they experienced “good” or ‘‘bad” forms of clinical practice. A critical incident cited by a student in the class is described below and used as an example in the remaining steps of the process:

The 40 year old cardiac patient was experiencing chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and headache. He was unable to take his oral medications for the heart condition and other problems. The student nurse notified the staff nurse assigned to the patient. The nurse told her not to “bother” the patient’s physician because they had talked with him earlier and he was aware of the patient’s present condition and had not given any additional orders to treat the patient. The nurse refused to call the physician for the student nurse.

Step Two: Note Personal Experience

An inability to relieve the patient of symptoms prompted the student to engage in critical thinking. The most helpful resource was the patient’s understanding of the students desire to care him and the faculty serving as a resource when the staff nurse differed in the student’s decision to call the physician. The helplessness experienced by the student nurse after the staff nurse refused to call the physician was the low point of the episode.

Step Three: Identify & Challenge Assumptions

Nurses rely on the medical doctor and or medications for relieving patient’s symptoms.

Staff nurse showed more compassion and caring for the physician than for the patient.

Staff nurse feared physician actions more than patient as a consumer of health care.

Student nurse had more compassion and caring for the patient than did the primary nurse assigned to his care.

The patient was passive in his ability to treat himself and required the care of his admitting physician.

The staff nurse and student nurse were in conflict with the method of treatment.

Step Four: Challenge the Importance of Context

Developmental context issues identified by the student nurse included the patient’s loss of role functions: i.e. head of household, family provider, faced with serious debilitating heart disease at an early age.

Professional context issues included student nurse-staff nurse relationships, student nurse-physician relationships. Students were concerned with care of this patient only and their perspective on the situation concerned only the patient, as opposed to staff nurses who were concerned with a myriad of other issues such as the physician’s actions, the days unit staffing, and previous experiences in caring for the patient.

Step Five: Imagine and Explore Alternatives

Student nurse could state she was caring for the patient also and would call the physician without the staff nurse’s permission.

The student nurse could confer with a faculty member and request the faculty member call the physician.

The student nurse could present the situation to the nurse responsible for all patients care on the unit.

The student could explain to the patient the staff nurse’s decision to not call the physician and perhaps the patient could call the physician from his room telephone.

The staff nurse could reassess the patient’s chest pain and other symptoms, and call the physician to report the changes with additional orders to treat the patient’s current status.

The student could reevaluate the situation from a more holistic viewpoint of the patient.

The student could provide nursing comfort measures for the symptoms noted for the patient without relying totally on the medical regimen.

Step Six: Reflective Skepticism

Are the decisions made by the unit nurses regarding assigned patients made with an awareness that the decisions have an impact on all members of the health care team?

Are nurses a part of a collaborative effort to assure that quality care standards are maintained?

Are unit nurses accepting the accountability and responsibility for providing nursing care to all patients according to the hospitals established standards of care?

Is the patient allowed to participate in decisions related to his/her plan of care?

Are the patient’s rights a factor in this situation?

Step Seven: Consequences of Critical Thinking Experience

Calling the physician without the nurse’s permission would be cultural suicide for the student. The student with less experience and nursing knowledge has questioned the nursing care practices of a “real” nurse.

Impostership may be a consequence also. The student nurse may agree with the staff nurse’s decision to not call the physician but the “correct” decision is to be a patient advocate.

The situation is jolting to a student nurse who envisions nursing practice as nursing education has shaped the student’s image of nursing practice. The student’s way of interpreting nursing practice and the way nursing is practiced differs. This jolting, halting, and fluctuating rhythm is “roadrunning.”

The student nurse realizes that nursing care practices and decisions involving patient care are complex and there are no set rules to serve as a rigid guide. Hence, another consequence may be “lost innocence.’’

Step Eight: Impact of Thinking Critically on Learning Outcomes

Patient care decisions learned in education programs may differ in nursing practice since many variables are considered in actual nursing practice situations.

Nurses standards of care may differ from student nurses, from ones ascribed to, and from ones reflected in actual nursing practice.

Nurses practice nursing from a medical model of care more than from an interdisciplinary patient care framework.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Students were pleased with their critical thinking experience in this class, citing the use of real clinical situations as a basis for learning and how the process assisted them in clarifying course objectives, understanding the management theory of the course, and validating clinical outcome behaviors. The richness of the critical incidents they chose helped make the method a success. They explored situations relating to issues of management, patients and families, nurse-physician relationships, and clinical nursing practice. Students also participated freely in discussions and they differed widely in their individual responses during each step of the process.

The eight-step critical thinking process encourages students to engage in critical thinking, to view situations from broad perspectives, and to seek solutions to problems and situations experienced in clinical practice settings. This learning strategy incorporates the realities of nursing practice, merges nursing education with practice, and involves students in affective, cognitive, and psychomotor domains of learning. It provides students with enhanced skills in critical thinking and prepares them to function in a dynamic and complex health care system. Baccalaureate nursing education programs seeking accreditation could document their graduates’ critical thinking abilities using this strategy at all levels of the curriculum. Completing the eight-step critical thinking learning strategy could also serve as an alternative clinical learning method for Registered Nurse students and students absent from clinical practice.

Brookfield’s culturalization themes for nursing and their relationship to critical thinking clearly have parallels in other professional fields. Educators in these fields might find it useful to study the extent to which the themes apply in other fields and possibly identify additional themes that could be used to teach the application and consequences of critical thinking in the real world. Critical incidents for use in the program could be suggested by recent graduates or developed by teachers, based on their own real-life experiences. Using Brookfield’s model of the four components of critical thinking as a basis for analyizing these incidents, multi-step processes such as the one described in this article could be established in many other fields.

- Allen, D., Bowers, B. & Diekelmann, N. (1989). Writing to learn: A reconceptualization of thinking and writing in the nursing curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education, 28 (1), 6-10.

- Brookfield, S., (1987). Developing critical thinkers: Challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Brookfield, S. (1993). On impostership, cultural suicide, and other dangers: How nurses learn critical thinking. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 5 (24), 197-205.

- del Bueno, D.J. (1990). Experience, education, and nurses’ ability to make clinical judgments. Nursing and Health Care, 11 (6), 290-293.

- Foster, P.J. Larson, D. & Loveless, E.M. (1993). Helping students learn to make ethical decisions. Holistic Nursing Practice, 7 (3), 28-35.

- Kramer, M. K. (1993). Concept clarification and critical thinking: Integrated processes. Journal of Nursing Education, 32 (9), 406-414.

- Lewis, J. B. (1992). The AIDS care dilemma: An exercise in critical thinking. The Journal of Nursing Education, 31 (3), 136-137.

- Miller, M.A., Malcolm, N.S. (1990). Critical thinking in the nursing curriculum. Nursing and Health Care, 11 (2), 67-73.

- National League for Nursing, (1989). Curriculum revolution: Reconceptualizing nursing education. New York: National League for Nursing Press.

- National League for Nursing, (1991). National League for Nursing Accreditation Criteria: 1991. New York: National League for Nursing Press.

- National League for Nursing, (1992). Perspective in Nursing-1991-1993. New York: National League for Nursing Press.

- U. S. Department of Education (1988). Secretary’s procedures and criteria for recognition of accrediting agencies. Federal Register, 53 (127),25088-25099.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. (1992). Healthy people 2000 national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Boston:Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Portland Community College | Portland, Oregon

Core outcomes.

- Core Outcomes: Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

Think Critically and Imaginatively

- Engage the imagination to explore new possibilities.

- Formulate and articulate ideas.

- Recognize explicit and tacit assumptions and their consequences.

- Weigh connections and relationships.

- Distinguish relevant from non-relevant data, fact from opinion.

- Identify, evaluate and synthesize information (obtained through library, world-wide web, and other sources as appropriate) in a collaborative environment.

- Reason toward a conclusion or application.

- Understand the contributions and applications of associative, intuitive and metaphoric modes of reasoning to argument and analysis.

- Analyze and draw inferences from numerical models.

- Determine the extent of information needed.

- Access the needed information effectively and efficiently.

- Evaluate information and its sources critically.

- Incorporate selected information into one’s knowledge base.

- Understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and access and use information ethically and legally.

Problem-Solve

- Identify and define central and secondary problems.

- Research and analyze data relevant to issues from a variety of media.

- Select and use appropriate concepts and methods from a variety of disciplines to solve problems effectively and creatively.

- Form associations between disparate facts and methods, which may be cross-disciplinary.

- Identify and use appropriate technology to research, solve, and present solutions to problems.

- Understand the roles of collaboration, risk-taking, multi-disciplinary awareness, and the imagination in achieving creative responses to problems.

- Make a decision and take actions based on analysis.

- Interpret and express quantitative ideas effectively in written, visual, aural, and oral form.

- Interpret and use written, quantitative, and visual text effectively in presentation of solutions to problems.

- AB: Auto Collision Repair Technology

- ABE: Adult Basic Education

- AD: Addiction Studies

- AM: Automotive Service Technology

- AMT: Aviation Maintenance Technology

- APR: Apprenticeship

- ARCH: Architectural Design and Drafting

- ASL: American Sign Language

- ATH: Anthropology

- AVS: Aviation Science

- BA: Business Administration

- BCT: Building Construction Technology

- BI: Biology

- BIT: Bioscience Technology

- CADD: Computer Aided Design and Drafting

- CAS/OS: Computer Applications & Web Technologies

- CG: Counseling and Guidance

- CH: Chemistry

- CHLA: Chicano/ Latino Studies

- CHN: Chinese

- CIS: Computer Information Systems

- CJA: Criminal Justice

- CMET: Civil and Mechanical Engineering Technology

- COMM: Communication Studies

- Core Outcomes: Communication

- Core Outcomes: Community and Environmental Responsibility

- Core Outcomes: Cultural Awareness

- Core Outcomes: Professional Competence

- Core Outcomes: Self-Reflection

- CS: Computer Science

- CTT: Computed Tomography

- DA: Dental Assisting

- DE: Developmental Education – Reading & Writing

- DE: Developmental Education – Reading and Writing

- DH: Dental Hygiene

- DS: Diesel Service Technology

- DST: Dealer Service Technology

- DT: Dental Lab Technology

- DT: Dental Technology

- EC: Economics

- ECE/HEC/HUS: Child and Family Studies

- ED: Paraeducator and Library Assistant

- EET: Electronic Engineering Technology

- ELT: Electrical Trades

- EMS: Emergency Medical Services

- ENGR: Engineering

- ESOL: English for Speakers of Other Languages

- ESR: Environmental Studies

- Exercise Science (formerly FT: Fitness Technology)

- FMT: Facilities Maintenance Technology

- FN: Foods and Nutrition

- FOT: Fiber Optics Technology

- FP: Fire Protection Technology

- GD: Graphic Design

- GEO: Geography

- GER: German

- GGS: Geology and General Science

- GRN: Gerontology

- HE: Health Education

- HIM: Health Information Management

- HR: Culinary Assistant Program

- HST: History

- ID: Interior Design

- INSP: Building Inspection Technology

- Integrated Studies

- ITP: Sign Language Interpretation

- J: Journalism

- JPN: Japanese

- LAT: Landscape Technology

- LIB: Library

- Literature (ENG)

- MA: Medical Assisting

- MCH: Machine Manufacturing Technology

- MLT: Medical Laboratory Technology

- MM: Multimedia

- MP: Medical Professions

- MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- MSD: Management/Supervisory Development

- MT: Microelectronic Technology

- MTH: Mathematics

- MUC: Music & Sonic Arts (formerly Professional Music)

- NRS: Nursing

- OMT: Ophthalmic Medical Technology

- OST: Occupational Skills Training

- PCC Core Outcomes/Course Mapping Matrix

- PE: Physical Education

- PHL: Philosophy