Photography and the Civil War

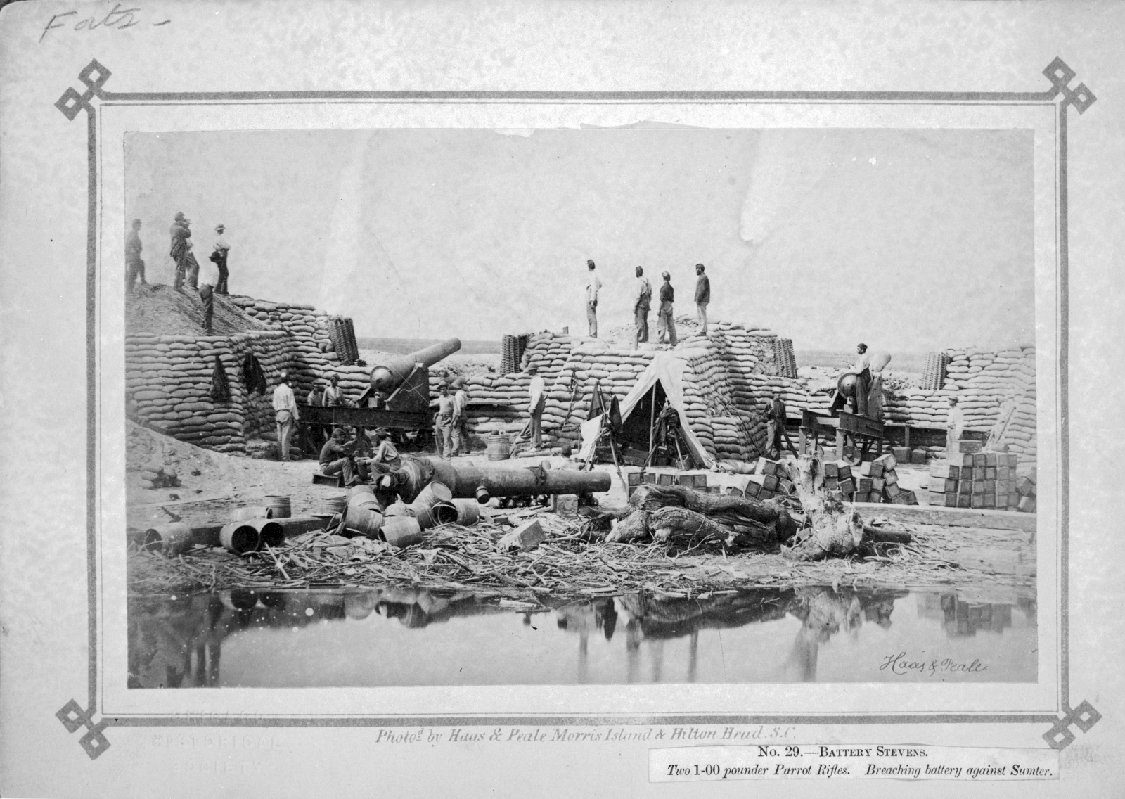

While photographs of earlier conflicts do exist, the American Civil War is considered the first major conflict to be extensively photographed. Not only did intrepid photographers venture onto the fields of battle, but those very images were then widely displayed and sold in ever larger quantities nationwide.

Photographers such as Mathew Brady , Alexander Gardner , and Timothy O'Sullivan found enthusiastic audiences for their images as the shockingly realistic medium piqued America's interests. For the first time in history, citizens on the home front could view the actual carnage of far away battlefields. Civil War photographs stripped away much of the Victorian-era romance around warfare.

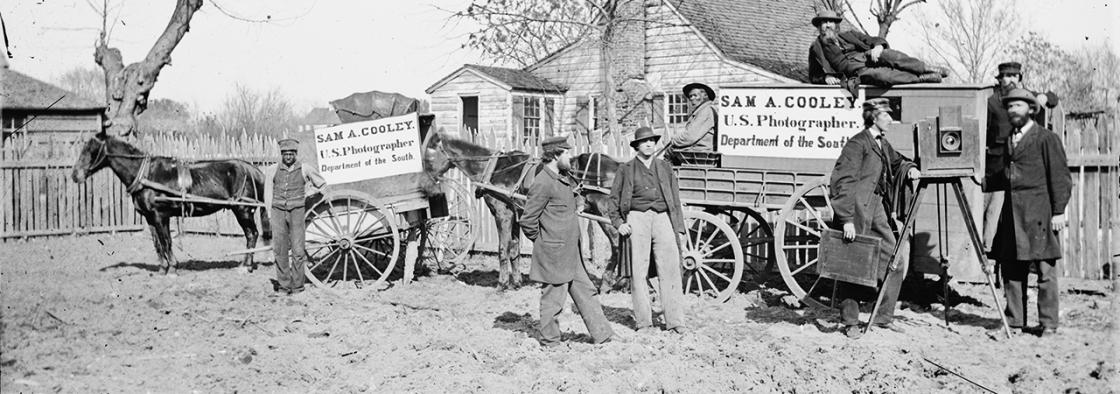

Photography during the Civil War, especially for those who ventured out to the battlefields with their cameras, was a difficult and time consuming process. Photographers had to carry all of their heavy equipment, including their darkroom, by wagon. They also had to be prepared to process cumbersome light-sensitive images in cramped wagons.

Today pictures are taken and stored digitally, but in 1861, the newest technology was wet-plate photography, a process in which an image is captured on chemically coated pieces of plate glass. This was a complicated process done exclusively by photographic professionals.

Cameras in the time of the Civil War were bulky and difficult to maneuver. All of the chemicals used in the process had to be mixed by hand, including a mixture called collodion. Collodion is made up of several types of dangerous chemicals including ethyl ether and acetic or sulfuric acid.

The photographer began the process of taking a photograph by positioning and focusing the camera. Then, he mixed the collodion in preparation for the wet-plate process.

The Wet-Plate Photographic Process:

- Collodion was used to coat the plate glass in order to sensitize it to light.

- In a darkroom, the plate was then immersed in silver nitrate, placed in a light-tight container, and inserted into the camera.

- The cap on the camera was removed for two to three seconds, exposing it to light and imprinting the image on the plate.

- Replacing the cap, the photographer immediately took the plate, still in the light-tight container, to his darkroom, where he developed it in a solution of pyrogallic acid.

- After washing and drying the plate with water, the photographer coated it with a varnish to protect the surface.

- This process created a plate glass negative. Once the plate-glass negative was made, the image could be printed on paper and mounted.

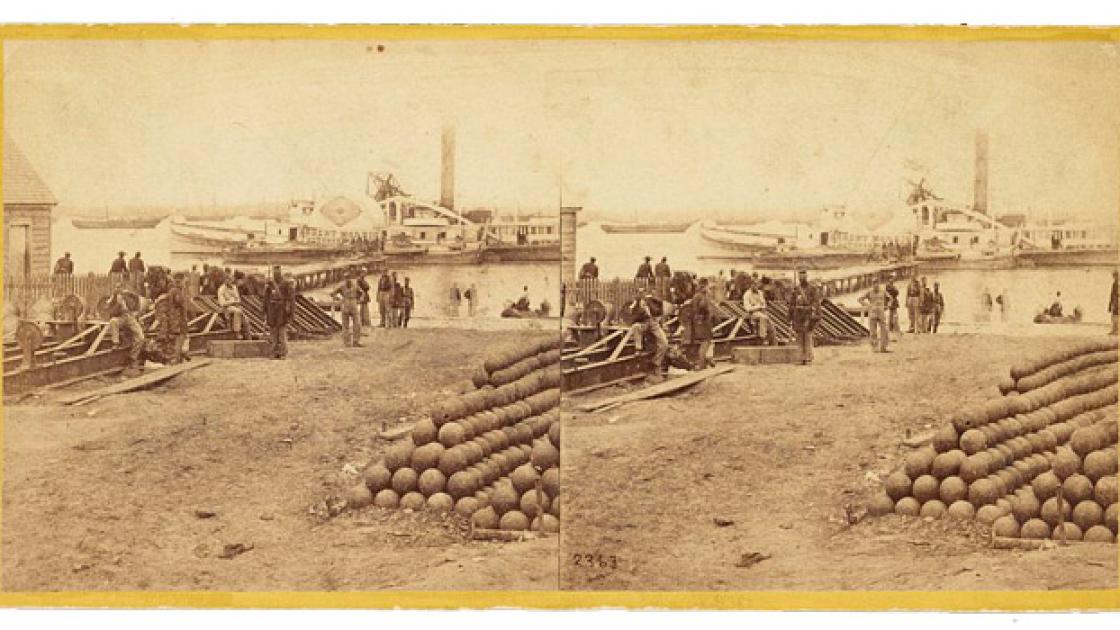

While photography of the 1860's would seem primitive by the technological standards of today, many of the famous Civil War photographers of the day were producing sophisticated three-dimensional images or "stereo views." These stereo view images proved to be extremely popular among Americans and a highly effective medium for displaying life-like images.

To create a stereo view image a twin-lens camera was used to capture the same image from two separate lenses, in much the same way that two human eyes capture the same image from slightly different angles on the head. The images were developed using the same wet-plate process, but stereoscopic photography produced two of the same image on one plate glass.

Once processed, the photographer would place the two stereo images onto a viewing card – the stereograph or stereoview card. These stereoview cards could then be easily inserted into widely available viewers creating a 3D image.

With these advancements in photographic technology, the Civil War became a true watershed moment in the history of photography. The iconic photos of the American Civil War would not only directly affect how the war was viewed from the home front, but it would also inspire future combat photographers who would take their cameras to the trenches of Flanders, the black sands of Iwo Jima, the steaming jungles of Vietnam, and the deserts of Afghanistan.

Escape to Freedom: Capturing the Journey at Cow’s Ford

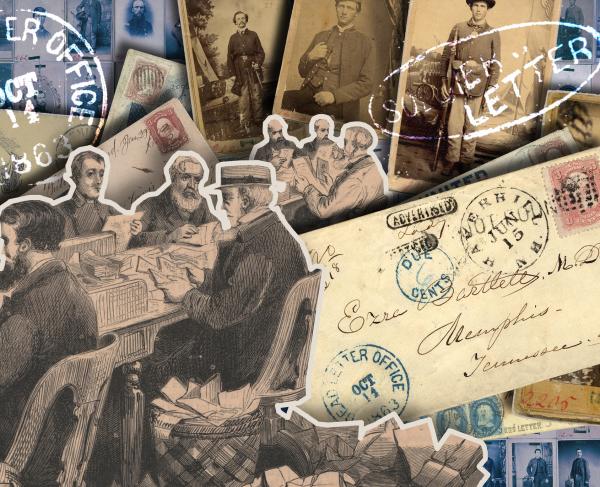

Lost In the Mail: Dead Letter Office Photos

10 Facts: Civil War Photography

Explore civil war photography.

Top of page

Witness to History: Civil War Photographs

April 19, 2017

Posted by: Barbara Orbach Natanson

Share this post:

Last month’s offering in this series of posts about documentary and photojournalism collections noted how the Crimean War posed an opportunity—and enormous challenges—to British photographer Roger Fenton .

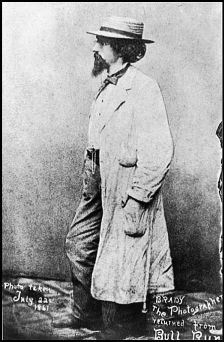

Just six years later, a conflict on American soil, likewise, fueled Mathew Brady’s entrepreneurial ambitions, leading to some of the best known photographic documentation of the Civil War. At the outbreak of war in April 1861, Mathew Brady, already well established as a portrait photographer, was fired with ambition to document the conflict between the Union and the Confederacy on a grand scale. Friends tried to discourage him, citing battlefield dangers and financial risks, but Brady persisted. He later said, “I felt that I had to go. A spirit in my feet said ‘Go,’ and I went.”

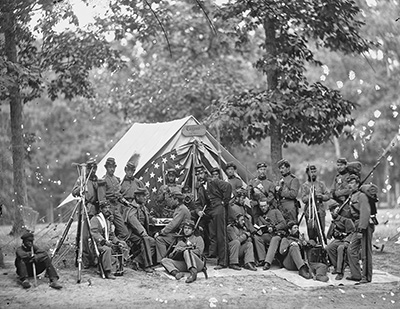

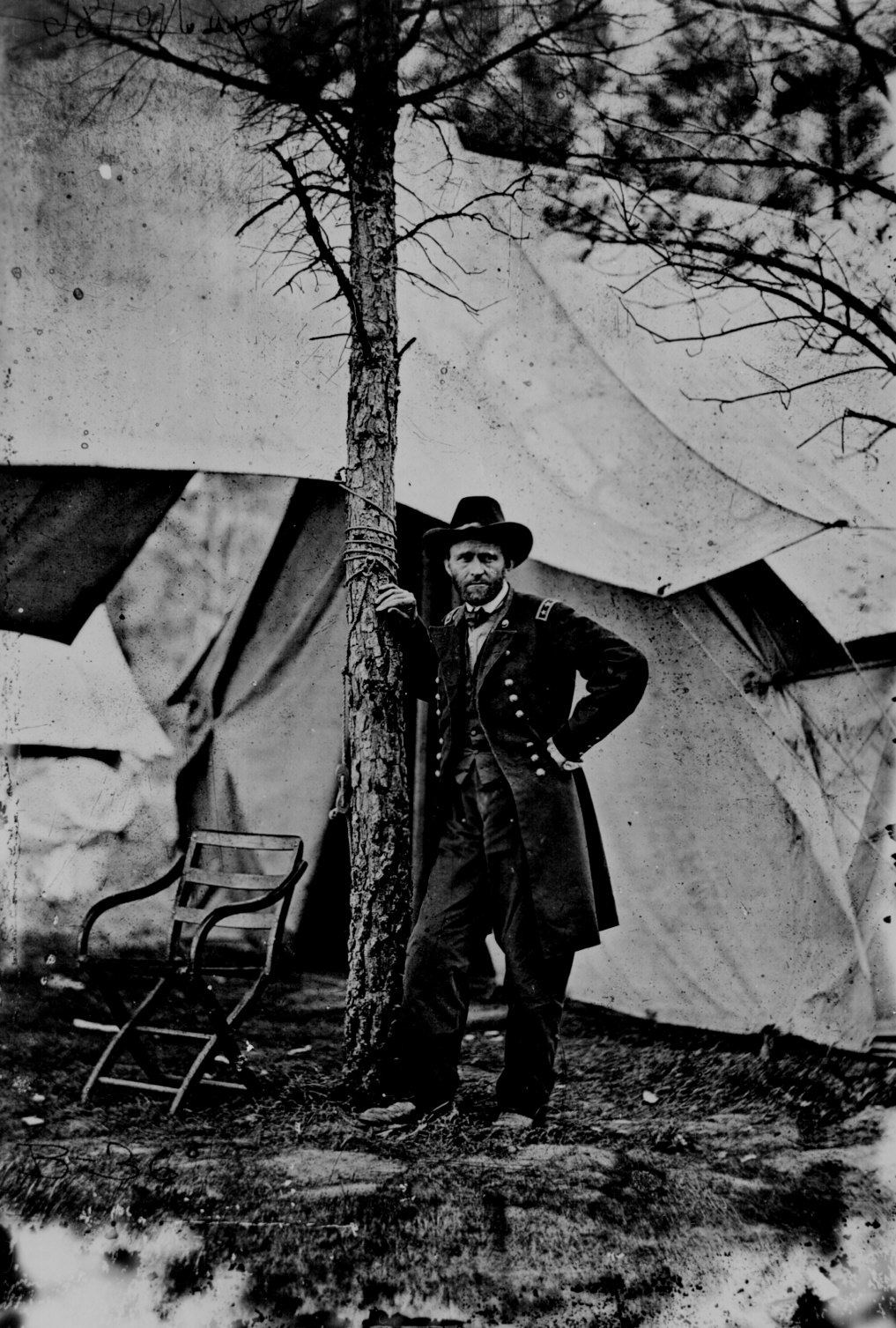

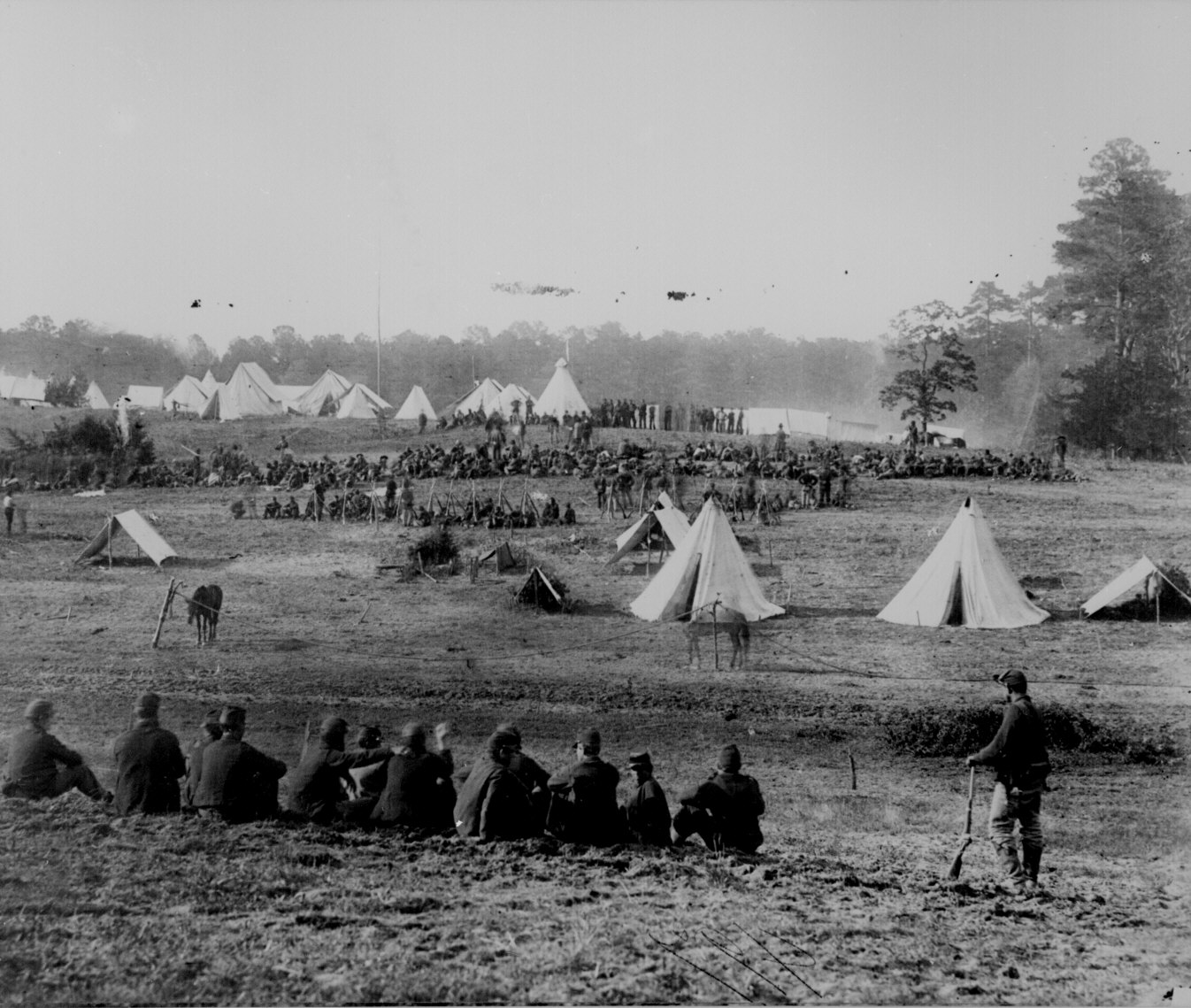

Brady didn’t actually take many of the Civil War photographs attributed to him but, rather, supervised a corps of traveling photographers and bought photos from private photographers fresh from the battlefield. The range of images, from portraits and camp scenes to landscapes and battle preparations and aftermath, is impressive.

Brady’s enterprise earned him attention in his own time and in the decades since. In 1862 Brady shocked America by displaying Alexander Gardner’s and James Gibson’s photographs of battlefield corpses from Antietam. Brady never achieved great wealth from his enterprise, but the New York Times said that he had brought “home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war.” Personally, I find some of the scenes of Richmond in ruins among the most haunting from any war.

Brady’s name became popularly associated with Civil War photography, but many photographers contributed to making a lasting photographic record of the war. The Prints and Photographs Division has photographs by quite a few photographers, including Alexander Gardner, James F. Gibson, Timothy O’Sullivan and Andrew J. Russell.

![in an informative research essay on the civil war photography Group at Commissary Depot, Acquia [i.e. Aquia] Creek Landing, Va. Photograph by Alexander Gardner, 1863 Feb. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.34243](https://blogs.loc.gov/picturethis/files/2017/04/CWGardner34243r.jpg)

The photographers’ combined efforts resulted in a multi-faceted view of the war’s participants and sites, although photographic technology at the time, as with the Fenton photographs, limited how much action a photographer could capture. The Prints and Photographs Division has more than 7,000 glass negatives made during the Civil War, all of which can be viewed as positive images online. The division also holds photographic prints that correspond to many of the negatives, as well as a photographic format that helped to bring Civil War scenes to life: stereographs enable the viewer to have a “you are there” experience when viewed through a special viewer.

A Research Focus

Just as researchers have explored how Roger Fenton may have shaped impressions of the Crimean War by staging photographs, the Civil War photographs have received in-depth analyses. Scholar William Frassanito, in particular, did pioneering work in closely examining photographs taken at Antietam and at Gettysburg. He turned up fascinating findings about how the photographs had been mislabeled (in one case, the same bodies are alternately described as Confederate and as Union soldiers) and how the scene that some photographs captured was altered for effect. (The “Learn More” section, below, gives full bibliographic information for the books.)

More recently, researchers from the Center for Civil War Photography have delved deeply into the content and context of the photographs, illuminating photography practice from the Civil War years, assisting in identification of the locations and scenes depicted, and taking participants in their Image of War seminars to the sites the photographers traversed more than 150 years ago. Along the way, they have informed our description of the images and provided support for ongoing scanning of the Civil War collections in the interest of sharing these images and all that they convey more widely.

- Visit our Civil War search page to get a broad overview of the holdings and try some of your own searches.

- View the Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photograph s, which brings us the faces of those who marched off to war and those who waited anxiously on the home front. The collection includes ambrotype and tintype portraits of Union and Confederate soldiers, as well as women and children.

- Dive more deeply into the Civil War photographs, and explore some of William A. Frassanito’s findings in online essays, Does the Camera Ever Lie? , The Case of Confused Identity , and The Case of the Moved Body , that accompany the Civil War photographs. To read the full story, look for some of Frassanito’s most influential books: Gettysburg: a Journey in Time (New York, Scribner [1975]) [ view catalog record ] and Antietam: the Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day (New York : Scribner, 1978) [ view catalog record ].

- Get perspective on what it took to make photographs in the field by reading the essay, Taking Photographs During the Civil War and viewing Civil War photographs and drawings that show photographers’ equipment .

- Follow the activities and insights of the Center for Civil War Photography through their Web site and Facebook page.

- I was treating myself at home to some “you are there” viewing through the pages of Bob Zeller’s and John Richter’s Lincoln in 3-D (San Francisco, Calif.: Chronicle Books, 2010) [ view catalog record ], which I found in my local public library. The book reproduces photographs from the Civil War, including many stereograph negatives and other images from Library of Congress collections, that come to life when you don the 3-D glasses that come packaged with the volume. I couldn’t resist sharing P&P’s copy of the book in the reading room–an easy way to thrill your friends and colleagues!

Comments (2)

Amazing! =)

It really makes you aware that these were real people. Looking at a photograph can put you in that place and that time. Great to have access at the Library of Congress web site.

See All Comments

Add a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Photography and History

The american civil war.

by Serena Covkin

WARNING: Some of the images within this article may be disturbing for a younger audience.

Photographing the Civil War

Americans at war.

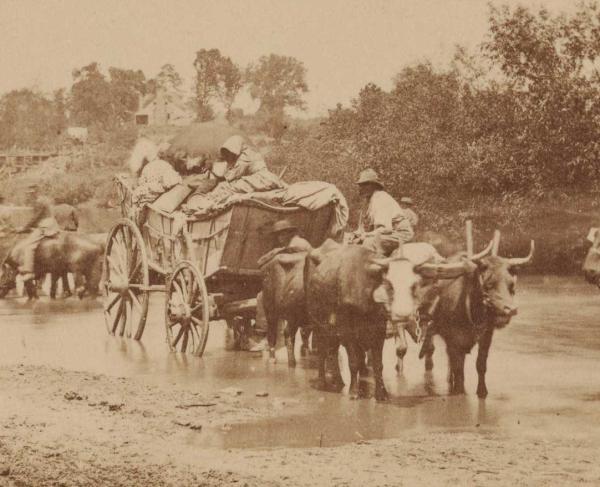

How did plantation owners and northern industrialists, yeoman farmers and slaves, and women and children experience the Civil War and the enormous social and political changes it wrought? Though the Civil War is the most written-about episode in American history, politicians continue to debate its legacy and historians continue to uncover rich new details and narratives. Recently a handful of scholars (perhaps influenced by studies of the impact of television on the Vietnam War) have sought to explore the relationship between the Civil War and the photographers and photographs that documented the conflict and its aftermath. 1 This article aims to summarize and synthesize much of this material in order to elucidate how photographs influenced Americans at war and on the homefront, and how they can enrich our present understanding of the Civil War.

The Library of Congress’ extensive collection of digitized Civil War photographs can be found here . Also, check out the website of the Center for Civil War Photography and its Guide to Finding Civil War Photos !

Daguerreotype

In 1839, Louis Daguerre and Joseph Nicéphone Niépce developed the daguerreotype, which used silvered copper plates to record real-life images for the first time. Almost immediately, entrepreneurial artists saw an opportunity to create innovative art and make money. 2 Likewise, it wasn’t long before photographers documented scenes of conflict—the Mexican-American War was the first to be photographed, though the pictures never reached the general public, and thus had almost no cultural impact. The 1850s were arguably the “golden years of the daguerreotype,” as practitioners opened hundreds of studios and honed their techniques as they documented more and more natural phenomena and major news events. 3 The new wet plate process introduced in the 1850s reduced necessary exposure times and made replication of negatives far simpler. 4

Interest in Photography

As improvements in technology rapidly accelerated, popular interest in photography grew exponentially. Photographers began to produce stereoscopic view cards, which could be produced on a mass scale and came close to displaying a three-dimensional image. These became wildly popular. Aided by new mail-order catalogs, people began to collect them. 5 The Holmes-Bates stereo viewer “created a vast new market among middle-class, nineteenth-century Americans and popularized the first media-driven form of American home entertainment.” 6 As opposed to paintings, photographs were relatively affordable, and ordinary Americans were able to commission family portraits.

Mathew Brady

Mathew Brady was one of the first famous American photographers, and his career was representative of many of the Civil War photographers. After opening his first studio, Brady deliberately sought to capture the “famous and powerful visages of the day”—and “it didn’t take long before leaders were coming to Brady, rather than the other way around.” 7 Not only was this a good business opportunity, but he genuinely believed that “The camera is the eye of history,” and aimed to preserve these images of the wealthy and important for posterity. 8

The embedded photograph, taken in 1860 by Mathew Brady before Abraham Lincoln was set to speak at Cooper Union, was perhaps the “first successful publicity photograph.” 9 Lincoln himself recognized its importance, remarking, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me the president of the United States.” 10 According to Lincoln, the “images would connect him with the electorate” and “people would read character from likeness.” 11 Brady’s manipulations minimized Lincoln’s ungainly appearance, and instead emphasized his “rugged dignity.” 12

To learn more about Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech and his presidential campaign, listen to this National Public Radio interview with Harold Holzer, author of Lincoln and Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President .

Civil War Photographers

When the Civil War began, Brady and other photographers—notably Alexander Gardner, George Barnard, A. J. Russell in the North, and Jacob F. Coonley, George S. Cook, J.D. Edwards, and Richard Wearn in the South—jumped into action. The American Journal of Photography insightfully declared, “Let us try to think that the good time coming is near at hand, and that we should prepare for it! If the hot-headed politicians will cry havoc! and let loose the dogs of war, let us not be distracted from our duties and our pleasures. We are told: In time of peace prepare for war, but a far more Christian maxim is: In time of adversity prepare for prosperity.” 13 Thus, most photographers set south in pursuit of profit. 14

Documenting History

At the same time, though, perhaps even more than ordinary Americans, photographers grasped the historical significance of the conflict and the acute need to document it for the future. As critic Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography , “Photographs furnish instant history, instant sociology, instant participation.” 15 Alexander Gardner, one of the premier Civil War photographers, declared, “Verbal representations of such places, or scenes, may or may not have the merit of accuracy; but photographic presentments of them will be accepted by posterity with an undoubting faith.” 16 Though photographs are always precisely engineered (as demonstrated by Brady’s photograph of Lincoln), their audience has long accepted them as perfectly faithful to reality. This perceived veracity made photography the ideal art form for a nation that valued “individual improvement and social progress through hard work, honesty, and faith.” 17

Presidential Permission

That Brady (and others) requested and received permission to follow the Union troops into battle was revolutionary. 18 Perhaps Lincoln maintained a soft spot for the photographer who assured his ascendance to the presidency, or perhaps he and other government officials appreciated the historical value of documentary photography. Either way, the intrepid photographers were subject to much of the same mortal danger, inclement weather, and dreadful living conditions as the combatants. 19 They developed their negative on the move, in “Whatsit Wagons” and other portable darkrooms, as in the photo above. 20 They often operated as part of larger studios; for example, thousands of photos were marked “Photo by Brady” but were taken by his many assistants and employees—strong intellectual property laws did not yet exist. 21

The romance of war lost its floss for many as they viewed the snarl from beneath overturned carriages and buggies.

The Battle of Antietam was the single bloodiest day in American history—and provided the first of many pictures of “corpse-strewn fields” to match.

Action shots.

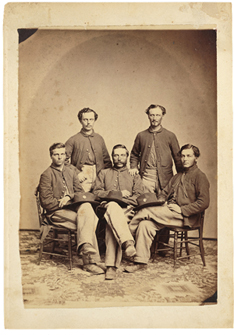

Only one “action shot” was taken during the Civil War, at the Battle of Antietam in 1862. The exposure times necessary for the wet plate process were too long to stop motion. 24 Often photographers took “studio-style” portraits of soldiers, like the photo above, which they sent back to their families. In fact, from the moment Union soldiers began to congregate in Washington, D.C., photographers were swarmed with requests for cartes de visite to send home. 25 As young men went off to war, a photograph “became an essential keepsake…for those staying at home,” as well as for the soldiers themselves. 26 Stereoviews were portable, and many combatants brought the images of loved ones with them to battle. Especially since the Christian notion of a “Good Death” mandated that men die in bed, at home, surrounded by family—an impossibility in war—they “endeavored to provide themselves with surrogates: proxies for those who might have surrounded their deathbeds at home.” 27 Accordingly, dead men were often found clutching photographs in their hands—“denied the presence of actual kin, many dying men removed pictures from pockets or knapsacks and spent their last moments communicating with these representations of absent loved ones.” 28

Painful Landscapes

Their seconds-long exposure times also led photographers to capture unmoving, devastated landscapes. Lincoln’s wartime policies sanctioned the “total destruction of property to financially drain and humiliate the enemy.” 29 On William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” soldiers destroyed crops, homes, and, most importantly, civilian infrastructure and transportation systems. Photographs of the destruction only compounded the economic hardships and psychological trauma that southerners suffered at Sherman’s hands. Also, these photographs provided essential visual context. In an age when cross-country travel was rare, these images were eye-opening. The landscapes underscored the war’s profound consequences, for American citizens and American soil.

![in an informative research essay on the civil war photography Dead Confederate soldier as he lay on the field, after the battle of the 19th May, near Mrs. Allsop's, Pine Forest, 3 miles from Spottsylvania [i.e. Spotsylvania] Court House, Va. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.](https://ushistoryscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/dead-confederate-soldier.jpg)

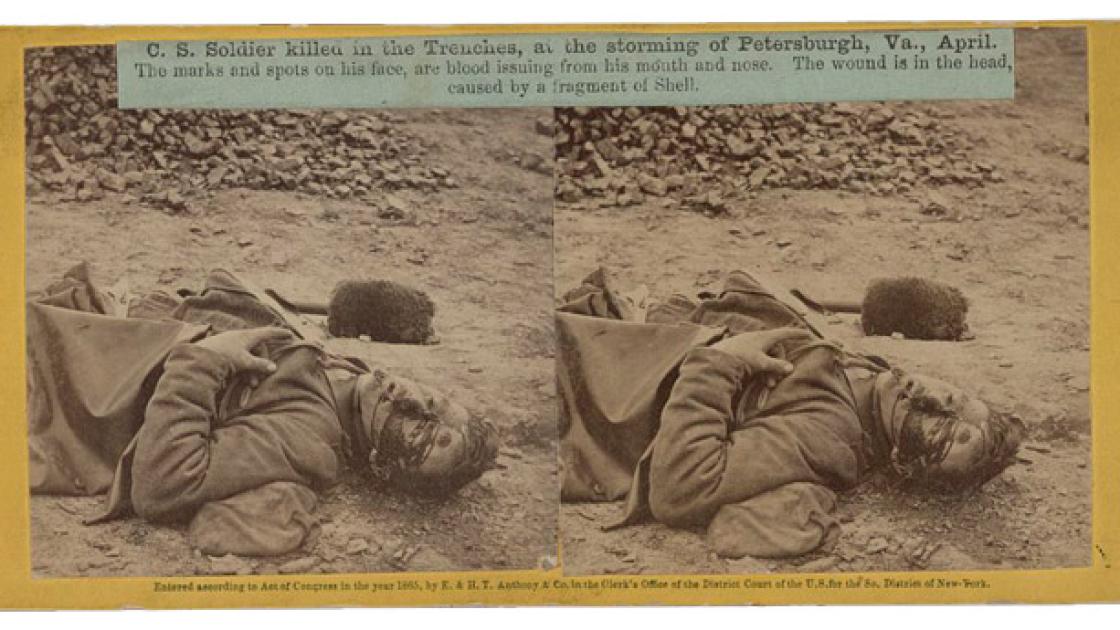

Dead Soldiers

Images of dead soldiers were even more impactful. In fact, not infrequently photographs rearranged the corpses in order to create more dramatic images. 30 In 1862, Brady opened a shocking photographic exhibition in his New York gallery, titled “The Dead of Antietam.” Civilians had never before seen photographs of wartime dead. A New York Times critic proclaimed, “If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it.” 31 Bob Zeller, the founder of the Center for Civil War Photography, proclaimed, “if no other artifact of the Civil War existed, if nothing had ever been said or written about the conflict, the Antietam photographs would be enough.” 32 Visitors flocked to Brady’s gallery in droves. Many even sought to identify their own missing loved ones in the piles of dead bodies, though most were unsuccessful. 33

![in an informative research essay on the civil war photography Antietam, Maryland. Dead soldiers in ditch on the right wing where Kimball's brigade fought so desperately. (1862) Unidentified soldier of Company G, 147th New York Infantry Regiment, with amputated arms] / Fredricks & Co., 179 Fifth Avenue, Madison Square, New York. (1861-1865).](https://ushistoryscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/civil-war-side-by-side-300x185.png)

Enormous Death Toll

Professor Drew Gilpin Faust’s exceptional book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War argues for the fundamental impact of the war’s enormously high death toll on American culture and society. She writes, “for Americans who lived in and through the Civil War, the texture of the experience, its warp and woof, was the presence of death.” 34 Certainly dead bodies proved useful subjects because of their stillness, but the photographers, too, were seized by a morbid fascination with this death on an unmatched scale. These photographers, though they neither killed nor died in war, became part of “the work of death” that Faust describes. 35 Photographs of dismembered and disfigured combatants (such as the photograph above) were particularly jarring for the American public. They felt forced to question their notions of “corporeal resurrection” in the afterlife, and faced daunting philosophical questions of how limbs “related to the persons who had once inhabited them.” 36 The above photograph of dead soldiers lying in a ditch challenged Americans’ idealized conception of honorable, noble death in war—instead, they were “in bunches, just like dead chickens”—“dehumanizing both the living and the dead through their disregard.” 37 Likewise, photographs that showed impossibly young, otherwise perfectly healthy dead combatants seemed a “violation of assumptions about life’s proper end.” 38

Photographing American Culture

![Washington : Philp & Solomons, [1866]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540. Gardner's photographic sketch book of the war. Washington : Philp & Solomons, [1866]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540.](https://ushistoryscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/00001r.jpg)

Just as the Civil War modernized the economy, it modernized culture, even if its effects took time to manifest themselves…It eroded Victorian habits of feeling and sentimentality. As Edmund Wilson argued, the war chastened American language, making it sharper, more concise, more pungent. The war stripped away illusions. This scourging was accelerated by a flourishing new medium: photography. Photography complemented—and competed with—old discursive methods of verbal description by bringing a visceral immediacy to an audience avid for images. Photographic images became the connective tissue binding the home front to the combat zone. And in a society anxious about its very survival, portraits of statesmen and generals provided reassuring testimony of steadfast character; Lincoln used photography to assert his leadership over a fractious polity. When Mathew Brady exhibited “The Dead of Antietam” in the fall of 1862, the horror and pit of war disoriented Americans. Sensation was replacing rationality in the public’s mind. In the writings from The Atlantic and photographs from the National Portrait Gallery in the pages that follow, one can see a people grappling to make sense of life in the cauldron of war. And one can see, in hesitant and undeveloped ways, the emergence of the modern United States of America. 39

War Profits

Despite their morbid content, sales of war photographs actually peaked after the South surrendered at Appomattox. 40 Many photographers published retrospectives of their work, such as Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War , shown above. Others, such as A. J. Russell, joined the legions of pioneers to the West, to document more adventure and continue to further their still-young art form. Photography became “an indispensable tool of the new mass culture that took shape here after the Civil War.”

Resources for Students

As students of history, how can we use these photographs to better understand the Civil War and its participants? The Library of Congress, among others, have made so many resources (including the Liljenquist Family Collection, above) available online. More than anything else, the photographs show us what Civil-War-era people and places looked like, and how war was fought. We are offered a glimpse at military strategy and technology . A photograph of an unidentified, very young Confederate soldier demonstrates the human cost of the southern nation’s desperation more than words ever could. We can even see how extraordinarily tall Lincoln really was relative to his peers. We see the soldiers’ encampments, weapons, hospitals, uniforms, and means of entertainment—according to Wayne Youngblood and Ray Bond, “all of these peeks into life during wartime give us glimpses of an intense period in the lives of thousands of scared and uncertain young men waiting to go to battle more than a hundred and thirty years ago.” 41

Capturing Diversity

Furthermore, photographs showcase many more people—and more diverse people—than were ever able to write down their impressions and experiences of war. By adding more faces to the historical record, they help us expand our understanding of history and whose stories should be included. Especially since the Confederacy deliberately privileged the opinions and narratives of the wealthy, white planter class at the expense of everyone else, this endeavor becomes particularly important as a source for relics of the Civil War.

Though a photograph is a record of a time long past, it is a three-dimensional object, and its continued presence thus allows past events to be repurposed and contextualized anew. Every moment can be reconsidered in an ever-changing present. As historians uncover more and more about the Civil War, interpretations of these photographs and their significance will shift, as well, always continuing to enrich our understanding of this essential episode.

![Unidentified soldier in Union uniform, unidentified woman, and unidentified baby Unidentified soldier in Union uniform, unidentified woman, and unidentified baby] / Newcomer's Gallery, 508 No. 2nd St., Phila. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540.](https://i0.wp.com/ushistoryscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Unidentified-soldier-in-Union-uniform-unidentified-woman-and-unidentified-baby.jpg?w=207&h=235&ssl=1)

HIS 226 - Civil War: Civil War Photography

- Find Articles

- Web Resources

- Primary Sources

- Civil War Medicine

- Civil War Women

- Civil War Weapons

- Civil War Photography

- Civil War Leaders

- Sherman and the March to the Sea

- Prisoner of War Camps

- Gettysburg And Political Significance

- Research Process

Matthew Brady

Films on Demand

Civil War Photography Films

- Photography and the Civil War

- War Photography

- The Photographers' War

Civil War Photography Articles

- CIVIL WAR PHOTOGRAPHY The American Civil War, however, altered both the face of warfare and of war photography. Like their European predecessors, American cameramen captured initially on glass the eager faces of volunteer soldiers, the martial postures of officers, tented camps, gun emplacements and landscapes scarred by earthworks.

- Capturing War's Grisly Face The photographers who documented the Civil War changed forever the way Americans looked at war. A look at some of the photographers and their work is offered.

- Armed to the Teeth? According to Field, "early war regiments often received some elements of uniform and clothing before they got their weapons and accouterments. According to collector David W. Vaughan, photographers at that time "perceived themselves as artists but were first and foremost entrepreneurs," and would have sought to make money through quality portraits.

Civil War -- Films on Demand

- A Beacon of Hope

- Blood and Glory

- Bloody Shiloh

- The Civil War

- Combat Series

- Civil War Journal

- River of Death

- Ken Burns' The Civil War

- << Previous: Civil War Weapons

- Next: Civil War Leaders >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 10:04 AM

- URL: https://libguides.rccc.edu/CivilWar

- DOI: 10.5860/choice.51-0687

- Corpus ID: 160263617

Photography and the American Civil War

- Jeff L. Rosenheim

- Published 6 May 2013

16 Citations

The war that does not leave us: memory of the american civil war and the photographs of alexander gardner, response to deborah willis's “the black civil war soldier: conflict and citizenship”, immortalizing death on the battlefield: us iconography of war from the american revolution to the civil war, "the last and most precious memento": photographic portraiture and the union citizen-soldier, ruins reframed: the commodification of american urban disaster, 1861-1906, long after the battle: james hope’s “authentic” commemoration of antietam’s bloody lane, ill-protected portraits: mathew brady and photographic copyright, the miracle of analogy or the history of photography, seeing lincoln: spielberg's film and the visual culture of the nineteenth century, developing visual literacy: historical and manipulated photography in the social studies classroom, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion? You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Featured publication: photography and the american civil war.

Photography and the American Civil War , by Jeff Rosenheim, features 297 color images and is available in The Met Store .

«Photography was invented just twenty years before the American Civil War. In many ways the war—its documentation, its soldiers, its battlefields—was the arena of the camera's debut in America. "The medium of photography was very young at the time the war began but it quickly emerged into the medium it is today," says Jeff Rosenheim, curator of the current exhibition Photography and the American Civil War (on view through September 2), and author of its accompanying catalogue . "I think that we are where we are in photographic history, in cultural history, because of what happened during the Civil War . . . it's the crucible of American history. The war changed the idea of what individual freedom meant; we abolished slavery, we unified our country, we did all those things, but with some really interesting new tools, one of which was photography."»

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery B, Petersburg, Virginia , 1864. Albumen silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 (33.65.241)

As the catalogue discusses, photography served many purposes during the war. It was used to promote abolition; as propaganda for both the northern and southern causes; as an important tool in the creation of Lincoln's public persona and career; as well as for reconnaissance and tactical observation. The Civil War also marks the beginning of photojournalism as we understand it today. Photographers in the field who worked for name-brand studios like those of Mathew B. Brady and Alexander Gardner can be understood as the first embedded journalists. In his illuminating text, Rosenheim posits that Brady and the many others who made the photography of war their business came to understand the social responsibility that was part of their art, the responsibility the camera gave them.

Clockwise: Unknown artist. The Pattillo Brothers, Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry , 1861–63. Quarter-plate ruby glass ambrotype with applied color. David Wynn Vaughn Collection; Unknown artist, Confederate Corporal (?) with British Rifle Musket and Bowie Knife, Likely from Georgia , 1861–62 (?), Sixth-plate ambrotype with applied color. David Wynn Vaughn Collection; Unknown artist, Private James House, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee , 1861–62 (?). Sixth-plate ruby glass ambrotype. David Wynn Vaughn Collection

"The Civil War created an incredible demand for photography. It was used by the Union and Confederate armies and of course by regular Americans who wanted photographs of their family members heading into danger, and of the battle scenes themselves," Rosenheim explains. "It's hard to imagine the pathos of people buying photographs of battlefields and slaughter and meticulously inserting the prints into photography portrait albums. But this was happening on a mass scale. I think there may have been a superstitious element to it. Families may have felt that if they could put pictures of their brothers, sons, husbands into an album—to contain their likenesses in some way—that they could stop their death." As the catalogue discusses, most stationers and portrait galleries—and there were many—were in business to accommodate soldiers' needs. People were dying so quickly, families wanted something to hold on to. This tremendous demand galvanized a rapid advancement in camera technology in the Civil War years, allowing for easier and cheaper photography. "This was a time of great democratic change," says Rosenheim. By 1863, thousands of people could afford to buy and commission photographs. "To see a photograph of yourself gave people a sense of their individuality."

Unknown artist, " Picture Gallery Photographs ," 1860s. Albumen silver print (carte de visite). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2013 (2013.57)

In his planning for the exhibition, Rosenheim scoured records from photography historians and from Civil War specialists, the military, newspapers, the Library of Congress, and websites developed by individuals simply uploading family portraits. "All of this incredible information is coming together on the Web—enlistment records, photographs with rare period inscriptions on the verso, scans of newspaper engravings—and now in many cases we are able to put together who made the photographs, where and when they were made, and who or what regiment is depicted. Every day something new is added to the digital universe, be it a new name in a government database, or the discovery of a single photograph from someone's attic."

Attributed to Andrew Joseph Russell, Laborers at Quartermaster's Wharf, Alexandria, Virginia , 1863–65. Albumen silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 (33.65.40)

Related Link The Met Store

Nadja Hansen

Nadja Hansen was formerly an editorial assistant in the Editorial Department.

Hilary Becker

Hilary Becker is an administrative assistant in the Editorial Department.

As we transition our order fulfillment and warehousing to W. W. Norton, select titles may temporarily appear as out of stock. We appreciate your patience.

On The Site

- photography

Photography and the American Civil War

by Jeff L. Rosenheim

288 Pages , 11.00 x 9.00 in , 297 b-w + color illus.

- 9780300191806

- Published: Tuesday, 7 May 2013

Also Available At:

- Barnes & Noble

- Seminary Co-op

- Description

This eye-opening study of Civil War photography traces the introduction of the camera into the battlefield and shows its influence on history and our responses to war Six hundred thousand lives were lost between 1861 and 1865, making the conflict between North and South the nation’s deadliest war. If the “War Between the States” was the test of the young republic’s commitment to its founding precepts, it was also a watershed in photographic history, as the camera recorded the epic, heartbreaking narrative from beginning to end—providing those on the home front, for the first time, with immediate visual access to the horrors of the battlefield.

Photography and the American Civil War features both familiar and rarely seen images that include haunting battlefield landscapes strewn with bodies, studio portraits of armed Confederate and Union soldiers (sometimes in the same family) preparing to meet their destiny, rare multi-panel panoramas of Gettysburg and Richmond, languorous camp scenes showing exhausted troops in repose, diagnostic medical studies of wounded soldiers who survived the war’s last bloody battles, and portraits of both Abraham Lincoln and his assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

Published on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg (1863), this beautifully produced book features Civil War photographs by George Barnard, Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, and many others.

Exhibition Schedule:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (04/01/13–09/02/13)

The Gibbes Museum of Art (09/27/13–01/05/14)

New Orleans Museum of Art (01/31/14–05/04/14)

Jeff Rosenheim is curator in charge in the department of photographs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

"Splendid . . . a wonderful enhancement of the show itself."— New York Review of Books "This is now the definitive source for our visual knowledge of the war and especially of its participants. Rosenheim’s focus on portraiture of soldiers humanizes long-familiar post-battlefield images of bloating corpses. His writing is crisp and full of detail. Best of all, the catalogue doesn’t just recount the photography of the war, it suggests how photography of the Civil War has influenced American art ever since."—Tyler Green, Modern Art Notes

Related Books

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact W.W. Norton to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Notice for Canadian Customers

Due to temporary changes in our shipping process, we cannot fulfill orders to Canada through our website from August 12th to September 30th, 2024.

In the meantime, you can find our titles at the following retailers:

- Powell’s

We apologize for the inconvenience and appreciate your understanding.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

The Museum will be closed on Tuesday, August 20, and Thursday, August 22. More

- Join & Give

Through the Camera’s Lens: The Civil War in Photographs

How are photographs different than artwork? In what ways do they depict reality? Do they represent the “truth”? How do photographs affect public opinion and support of war? Are these images journalistic or artistic?

Lesson 1: On Deck of a Union Warship In this lesson, students will analyze an image of a Union warship. The lesson explores the purpose and effectiveness of naval blockades and the experience of serving on board a ship performing this type of duty. Students will analyze the photograph for detail, including parts of the ship and crewmembers’ leisure time, uniforms, and jobs. A class discussion will summarize small group findings about the photograph. The lesson culminates in a writing activity in which students place themselves in the photograph and write a letter as a crewmember of the ship to an imaginary friend or relative. This photograph can also be used as the inspiration for a geometry lesson. Download On Deck of a Union Warship .

Lesson 2: Civil War Photography Students will work in small groups to analyze a variety of photographs from the studios of Mathew Brady. In a timed rotation, students will work together to complete an initial observation chart for each image. Each small group will present its findings to the class. As individuals, students will then take their analysis to a higher level by answering key questions about the images and expressing critical thinking about photography during the Civil War and today. Download Civil War Photography .

Still Pictures

Civil War Photographs

Engineers of the 8th New York State Militia in front of a tent, 1861. Local Identifier: 111-B-499. National Archives Identifier: 524918.

View in National Archives Catalog

Introduction

The Civil War was the first large and prolonged conflict recorded by photography. During the war, dozens of photographers--both as private individuals and as employees of the Confederate and Union Governments--photographed civilians and civilian activities; military personnel, equipment, and activities; and the locations and aftermaths of battles. Because wet-plate collodion negatives required from 5 to 20 seconds exposure, there are no action photographs of the war.

The name Mathew B. Brady is almost a synonym for Civil War photography. Although Brady himself actually may have taken only a few photographs of the war, he employed many of the other well-known photographers before and during the war. Alexander Gardner and James F. Gibson at different times managed Brady's Washington studio. Timothy O'Sullivan, James Gardner, and Egbert Guy Fox were also employed by Brady during the conflict.

The pictures listed in this select list of photographs are in the Still Picture Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Most are part of the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer (Record Group 111) and Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs (Record Group 165). The records include photographs from the Mathew B. Brady collection (Series Identifier 111-B), purchased for $27,840 by the War Department in 1874 and 1875, photographs from the Quartermaster's Department of the Corps of Engineers, and photographs from private citizens donated to the War Department.

Photographs included in this select list have been organized under one of four main headings: activities, places, portraits, and Lincoln's assassination. Items in the first two parts are arranged under subheadings by date, with undated items at the end of each subheading. Photographs of artworks have also been included in the list. Any item not identified as an artwork is a photograph. Names of photographers or artists and dates of items have been given when available, and an index to photographers follows the list.

Many photographs of the Civil War held by the National Archives are not listed here. A list of selected fully digitized series are included below. Separate inquiries about other Civil War photography should be as specific as possible listing names, places, events, and other details. We have very few portraits of lower ranking individuals and much of our Civil War holdings highlight high-ranking military personnel. In addition, nearly all of our images of Confederates illustrate high-ranking officials and personnel.

Sandra Nickles and Joe D. Thomas did the research, selection, and arrangement for this list and wrote these introductory remarks when this list was revised in 1999. Additional updates to this introduction were made as recently as May 2021. The photographs within this list are within the public domain and have no Use Restrictions.

Fully Digitized Series of Interest :

- 111-B: Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes

- 111-BZ: Photographs Relating to the Civil War

- 165-HV: Herbert Eugene Valentine's Sketches of Civil War Scenes

- 165-SB: " Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War ," by Alexander Gardner

Ringgold Battery on drill. Local Identifier: 111-B-363. National Archives Identifier: 524783.

1. Log hut company kitchen, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524671, Local Identifier: 111-B-252

2. Soldiers at rest after drill, Petersburg, Va., 1864. The soldiers are seated reading letters and papers and playing cards. National Archives Identifier: 524639, Local Identifier: 111-B-220

3. A regimental fife-and-drum corps. National Archives Identifier: 524747, Local Identifier: 111-B-328

4. Winter quarters; soldiers in front of their wooden hut, "Pine Cottage." National Archives Identifier: 524675, Local Identifier: 111-B-256

5. Engineers of the 8th New York State Militia in front of a tent, 1861. National Archives Identifier: 524918, Local Identifier: 111-B-499

6. The 26th U.S. Colored Volunteer Infantry on parade, Camp William Penn, Pa., 1865. National Archives Identifier: 533126, Local Identifier: 165-C-692

7. The 21st Michigan Infantry, a company of Sherman's veterans. National Archives Identifier: 525076, Local Identifier: 111-B-671

8. Ringgold, Ga., battery at drill. National Archives Identifier: 524783, Local Identifier: 111-B-363

Pontoon across Rappahannock River, Va. (alson cavalry column.) Local Identifier: 111-B-508. National Archives Identifier: 524925.

9. Army blacksmith and forge, Antietam, Md., September 1862. National Archives Identifier: 559270, Local Identifier: LC-CC-587

10. Dismounted parade of the 7th New York Cavalry in camp, 1862. Some mounted troops are in the background. National Archives Identifier: 524921, Local Identifier: 111-B-502

11. Federal cavalry column along the Rappahannock River, Va., 1862. National Archives Identifier: 524925, Local Identifier: 111-B-508

12. A black family entering Union lines with a loaded cart. National Archives Identifier: 559271, Local Identifier: 200-CC-657 .

13. A refugee family leaving a war area with belongings loaded on a cart. National Archives Identifier: 55926, Local Identifier: 200-CC-306 .

14. Black laborers on a wharf, James River, Va. National Archives Identifier: 524820, Local Identifier: 111-B-400

Communications and Intelligence

15. Allan Pinkerton, chief of McClellan's secret service, with his men near Cumberland Landing, Va., May 14, 1862. (Pinkerton is smoking a pipe.) Photographed by George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson. National Archives Identifier: 522914, Local Identifier: 90-CM-385 .

16. Federal observation balloon Intrepid being inflated. Battle of Fair Oaks, Va., May 1862. National Archives Identifier: 525085, Local Identifier: 111-B-680 .

17. Scouts and guides for the Army of the Potomac, Berlin, Md., October 1862. Photographed by Alexander Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533302, Local Identifier: 165-SB-28 .

18. Constructing telegraph lines, April 1864. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 533336, Local Identifier: 165-SB-62 .

19. Signal Tower at Cobb's Hill, near New Market, Va., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 533120, Local Identifier: 165-C-571 .

20. A New York Herald Tribune wagon and reporters in the field. National Archives Identifier: 529494, Local Identifier: 111-B-5393 .

21. President Lincoln visiting the battlefield at Antietam, Md., October 3, 1862. General McClellan and 15 members of his staff are in the group. Photographed by Alexander Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533297, Local Identifier: 165-SB-23 .

22. Gen. George Thomas and a group of officers at a council of war near Ringgold, Ga., May 5, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 519439, Local Identifier: 77-HMS-344-2P .

23. Council of war near Massaponax Church, Va., May 21, 1864. General Grant is looking over General Meade's shoulder at a map Meade holds. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 559272, Local Identifier: 200-CC-730 .

Engineering

24. Pontoon bridge at Bull Run, Va., 1862. National Archives Identifier: 524487, Local Identifier: 111-B-68 .

25. Federal engineers bridging the Tennessee River at Chattanooga, March 1864. National Archives Identifier: 519418, Local Identifier: 77-F-147-2-6 .

26. Digging the Dutch Gap Canal on the James River, Va., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 526202, Local Identifier: 111-B-2006 .

27. The four-tiered, 780-foot-long railroad trestle bridge built by Federal engineers at Whiteside, Tenn., 1864. A guard camp is also shown. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 524900, Local Identifier: 111-B-482 .

28. Pontoon bridge across the James River at Richmond, Va., 1865. National Archives Identifier: 533119, Local Identifier:165-C-568 .

Foreign Observers

29. Diplomats at the foot of an unidentified waterfall, New York State, August 1863. Left to right: unidentified; State Department messenger Donaldson; unidentified; Count Alexander de Bodisco; Count Edward Piper, Swedish Minister; Joseph Bertinatti, Italian Minister; Luis Molina, Nicaraguan Minister (seated); Rudolph Mathias Schleiden, Hanseatic Minister; Henri Mercier, French Minister; William H. Seward, Secretary of State (seated); Lord Richard Lyons, British Minister; Baron Edward de Stoeckel, Russian Minister (seated); and Sheffield, British attache. National Archives Identifier: 518056, 59-DA-43 .

30. A group of foreign observers with Maj. Gen. George Stoneman at Falmouth, Va. 1863. National Archives Identifier: 522913, Local Identifier: 90-CM-47 .

31. Crew of the Russian frigate Osliaba docked at Alexandria, Va., 1863. National Archives Identifier: 518113, Local Identifier: 64-CV-210 .

Generals in the Field

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant standing by a tree in front of a tent, Cold Harbor, Va. Local Identifier: 111-B-36. National Archives Identifier: 524455.

32. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant standing by a tree in front of a tent, Cold Harbor, Va., June 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524455, Local identifier: 111-B-36 .

33. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade standing in front of his tent, June 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524434, Local Identifier: 111-B-16 .

34. Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan and his generals in front of Sheridan's tent, 1864. Left to right: Wesley Merritt, David McM.Gregg, Sheridan, Henry E. Davies (standing), James H. Wilson, and Alfred Torbert. National Archives Identifier: 524427, Local Identifier: 111-B-9 .

35. Wounded soldiers being tended in the field after the Battle of Chancellorsville near Fredericksburg, Va., May 2, 1863. National Archives Identifier: 524768, Local Identifier: 111-B-349 .

36. Amputation being performed in a hospital tent, Gettysburg, July 1863. National Archives Identifier: 520203, Local Identifier: 79-T-2265 .

37. Ambulance drill of the 57th New York Infantry, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524469, Local Identifier: 111-B-50 .

38. Ward in the Carver General Hospital, Washington, D.C. National Archives Identifier: 524592, Local Identifier: 111-B-173 .

39. " Volunteer Refreshment Saloon, Supported Gratuitously by the Citizens of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania." The picture includes a view of the outside and three small views of the inside. Lithograph by W. Boell, 1861. National Archives Identifier: 512769, Local Identifier: 15-M-40 .

40. Chaplain conducting mass for the 69th New York State Militia encamped at Fort Corcoran, Washington, D.C., 1861. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. National Archives Identifier: 533114, Local Identifier: 165-C-100 .

41. Members of the Christian Commission at their field headquarters near Germantown, Md., September 1863. Photographed by James Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533327, Local Identifier: 165-SB-53 .

42. Religious services on the deck of the U.S. monitor Passaic, 1864. Stereo photograph by Samuel A. Cooley. National Archives Identifier: 533272, Local Identifier: 165-S-165 .

43. U.S. Sanitary Commission building and flag, Richmond, Va., 1865. National Archives Identifier: 524566, Local Identifier: 111-B-147 .

First ironclad gunboat built in America. The Saint Louis. Local Identifier: 165-C-630. National Archives Identifier: 533123.

44. Battle between the C.S.S. Virginia and the U.S.S. Monitor, Hampton Roads, Va., March 9, 1862. Engraved in 1863 by J. Davies from a drawing by C. Parsons. National Archives Identifier: 518105, Local Identifier: 64-CC-63 .

45. U.S.S. St. Louis, first Eads ironclad gunboat, renamed the Baron de Kalb in October 1862. National Archives Identifier: 533123, Local Identifier: 165-C-630 .

46. "Men Wanted for the Navy!" Federal recruiting poster issued at New Berne, N.C., November 1863. National Archives Identifier: 516344, Local Identifier: 45-X-10 .

47. Confederate ram Atlanta after being captured on the James River, Va., 1863. National Archives Identifier: 527533, Local Identifier: 111-B-3351 .

48. C.S.S. Alabama, commerce raider, sunk June 19, 1864. Artwork by Clary Ray. National Archives Identifier: 512993, Local Identifier: 19-N-13042 .

49. Ruins of the navy yard at Norfolk, Va., December 1864. Photographed by James Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533292, Local Identifier: 165-SB-18 .

50. U.S.S. Commodore Perry, a ferryboat converted into a gunboat, Pamunkey River, Va., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524831, Local Identifier: 111-B-411 .

51. Gun crew of a Dahlgren gun at drill aboard the U.S. gunboat Mendota, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524794, Local Identifier: 111-B-374 .

52. Sailors and marines on the deck of the U.S. gunboat Mendota, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524548, Local Identifier: 111-B-129 .

53. U.S.S. Onondaga, a double-turreted monitor, on the James River, Va., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524788, Local Identifier: 111-B-368 .

54. Capt. John A. Winslow (3d from left) and officers on board the U.S.S. Kearsarge after sinking the C.S.S. Alabama, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524868, Local Identifier: 111-B-448 .

55. A Union station on the James River established for extracting gunpowder from Confederate torpedoes, 1864. Photographed by Egbert Guy Fox. National Archives Identifier: 524854, Local Identifier: 111-B-434 .

56. Confederate torpedo boat David aground at Charleston, S.C., 1865. Photographed by Selmar Rush Seibert. National Archives Identifier: 533129, Local Identifier: 165-C-751 .

57. C.S.S. Manassas, armored ram. Artwork by R. G. Skerrett, 1904. National Archives Identifier: 512991, Local Identifier: 19-N-13004 .

58. Columbiad guns of the Confederate water battery at Warrington, Fla. (entrance to Pensacola Bay), February 1861. Photographed by W. 0. Edwards or J. D. Edwards of New Orleans, La. National Archives Identifier: 519437, Local Identifier: 77-HL-99-1 .

59. Confederate "Quaker" guns-logs mounted to deceive Union forces-in the fortifications at Centreville, Va., March 1862. Photographed by George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson. National Archives Identifier: 533280, Local Identifier: 165-SB-6 .

60. The 13-inch mortar "Dictator" mounted on a railroad flatcar before Petersburg, Va., October 1864. Photographed by David Knox. National Archives Identifier: 533349, Local Identifier: 165-SB-75 .

61. Confederate Napoleon gun used in the defense of Atlanta, 1864. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 528856, Local Identifier: 111-B-4738 .

62. A 200-pound Parrott rifle in Fort Gregg on Morris Island, S.C., 1865. Photographed by Samuel A. Cooley. National Archives Identifier: 533271, Local Identifier: 165-S-128 .

63. Confederate torpedoes, shot, and shells in front of the arsenal, Charleston, S.C., 1865. Photographed by Selmar Rush Seibert. National Archives Identifier: 533134, Local Identifier: 165-C-796 .

64. A 15-inch Rodman gun in Battery Rodgers, Alexandria, Va. National Archives Identifier: 524772, Local Identifier: 111-B-353 .

Photographers and Their Equipment

65. Two photographers having lunch in the Bull Run area before the second battle, 1862. National Archives Identifier: 522912, Local Identifier: 90-CM-42 .

66. Mathew B. Brady under fire with a battery before Petersburg, Va., June 21, 1864. Brady, in the foreground, is wearing a straw hat. National Archives Identifier: 524765, Local Identifier: 111-B-346 .

67. Brady's photographic outfit in the field near Petersburg, Va., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 529185, Local Identifier: 111-B-5077 .

68. Barnard's photographic equipment, southeast of Atlanta, Ga., 1864. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 528870, Local Identifier: 111-B-4753 .

Prisoners and Prisons

Camp scene. Guarding Confederate prisoners. Local Identifier: 111-B-497. National Archives Identifier: 524916.

69. Confederate prisoners captured in the Shenandoah Valley being guarded in a Union camp, May 1862. National Archives Identifier: 524916, Local Identifier: 111-B-497 .

70. Three Confederate prisoners from the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1863. National Archives Identifier: 559274, Local Identifier: 200-CC-2288 .

71. Baseball game between Union prisoners at Salisbury, N.C., 1863. Lithograph of a drawing by Maj. Otto Boetticher. National Archives Identifier: 530502, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1952 .

72. Issuing rations. Andersonville Prison, Ga., August 17, 1864. Photographed by A. J. Riddle. National Archives Identifier: 533034, Local Identifier: 165-A-445 .

73. Libby Prison, Richmond, Va., April 1865. Photographed by Alexander Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533362, Local Identifier: 165-SB-89 .

74. Old Capitol Prison, Washington, D.C. National Archives Identifier: 526486, Local Identifier: 111-B-2292 .

Quartermaster and Commissary

75. Commissary Department, Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, Brandy Station, Va., February 1864. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 533335, Local Identifier: 165-SB-61 .

76. Burying the dead at Fredericksburg, Va., after the Wilderness Campaign, May 1864. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 528928, Local Identifier: 111-B-4817 .

77. Landing supplies at the wharf at City Point, Va., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524571, Local Identifier: 111-B-152 .

78. Men of the Quartermaster's Department building transport steamers on the Tennessee River at Chattanooga, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 533135, Local Identifier: 165-C-1068 .

79. Excavating for a "Y" at Devereux Station on the orange and Alexandria Railroad. Brig. Gen. Hermann Haupt, Chief of Construction and Transportation, U.S. Military Railroads, is standing on the bank supervising the work. The "General Haupt," the engine pulling the train in the photograph, was named in Haupt's honor. Photographed by Capt. Andrew J. Russell. National Archives Identifier: 528988, Local Identifier: 111-B-4877 .

80. Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. National Archives Identifier: 524502, Local Identifier: 111-B-83 .

81. U.S. Military Railroads engine "General Haupt," built in 1863. National Archives Identifier: 529255, Local Identifier: 111-B-5149 .

82. Ruins of the Confederate enginehouse at Atlanta, Ga., September 1864, showing the engines "Telegraph" and "O.A. Bull." National Archives Identifier: 528865, Local Identifier: 111-B-4748 .

83. Ruins of Hood's 28-car ammunition train and the Schofield Rolling Mill, near Atlanta, Ga., September 1864. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 528899, Local Identifier: 111-B-4786 .

84. Depot of the U.S. Military Railroads, City Point, Va., 1864, showing the engine "President." National Archives Identifier: 528971, Local Identifier: 111-B-4860 .

85. U.S. Military Railroads engine No.137, built in l864 in the yards at Chattanooga, Tenn., with troops lined up in the background. National Archives Identifier: 526201, Local Identifier: 111-B-2005 .

86. The engine "Firefly" on a trestle of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. National Archives Identifier: 524604, Local Identifier: 111-B-185 .

Battle Areas

87. Fort Sumter, S.C., April 14, 1861, under the Confederate flag. National Archives Identifier: 532292, Local Identifier: 121-BA-914A .

88. Ruins of Stone Bridge, Bull Run, Va., March 1862. Photographed by George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson. National Archives Identifier: 533281, Local Identifier: 165-SB-7 .

89. Confederate fortifications, Manassas, Va., March 1862. Photographed by George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson. National Archives Identifier: 533285, Local Identifier: 165-SB-11 .

90. "General Headquarters near Yorktown, Va., April 1862." Watercolor by William Mcllvaine. National Archives Identifier: 559420, Local Identifier: 200-WM-8 .

91. Main street and church guarded by Union soldiers, Centreville, Va., May 1862. Photographed by George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson. National Archives Identifier: 533278, Local Identifier: 165-SB-4 .

92. "Battle of Gaines Mill, Valley of the Chickahominy, Virginia, June 27, 1862." Artwork by Prince de Joinville. National Archives Identifier: 530495, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1507 .

93. Antietam Bridge, Md., September 1862. Soldiers and wagons are crossing the bridge. Photographed by Alexander Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533293, Local Identifier: 165-SB-19 .

94. Street scene, Warrenton, Va., ca. 1862. National Archives Identifier: 529340, Local Identifier: 111-B-5236 .

95. Fredericksburg, Va., February 1863. View from across the Rappahannock River. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 533304, Local Identifier: 165-SB-30 .

96. Confederate dead behind the stone wall of Marye's Heights, Fredericksburg, Va., killed during the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 1863. Photographed by Capt. Andrew J. Russell. National Archives Identifier: 524930, Local Identifier: 111-B-514 .

97. Fairfax Court House, Virginia, with Union soldiers in front and on the roof, June 1863. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 528872, Local Identifier: 111-B-4755 .

98. Dead Confederate sharpshooter in the Devil's Den, Gettysburg, Pa., July 1863. Photographed by Alexander Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533315, Local Identifier: 165-SB-41 .

99. Union and Confederate dead, Gettysburg Battlefield, Pa., July 1863. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 533310, Local Identifier: 165-SB-36 .

100. Lee and Gordon's Mills. Chickamauga Battlefield, Ga., 1863. National Archives Identifier: 528904, Local Identifier: 111-B-4791 .

101. General Meade's headquarters. Culpeper, Va., 1863. National Archives Identifier: 518112, Local Identifier: 64-CV-182 .

102. Capt. Edmund C. Bainbridge's Battery A, 1st U.S. Artillery, at the siege of Port Hudson, La., 1863. National Archives Identifier: 533151, Local Identifier: 165-CN-12545 .

103. Palisades and chevaux-de-frise in front of the Potter House, Atlanta, Ga., 1864. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 525131, Local Identifier: 111-B-726 .

104. Peachtree Street with wagon traffic, Atlanta, Ga., 1864. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 533419, Local Identifier: 165-SC-46 .

105. Street scene showing Sutlers Row, Chattanooga, Tenn., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524928, Local Identifier: 111-B-512 .

106. Fort Morgan, Mobile Point, Ala., 1864, showing damage to the south side of the fort. National Archives Identifier: 519417, Local Identifier: 77-F-82-70 .

107. Union entrenchments near Kenesaw Mountain, Ga., 1864. National Archives Identifier: 524941, Local Identifier: 111-B-531 .

108. Nashville, Tenn., view from the capitol, 1864. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 533376, Local Identifier: 165-SC-3 .

109. The "Pulpit" after capture, Fort Fisher, N.C., January 1865. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 533353, Local Identifier: 165-SB-79 .

110. Harpers Ferry, W Va., July 1865. High-angle view showing the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers. Photographed by James Gardner. National Archives Identifier: 533300, Local Identifier: 165-SB-26 .

111. McLean house where General Lee surrendered. Appomattox Court House, Va., April 1865. Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan. National Archives Identifier: 533371, Local Identifier: 165-SB-99 .

112. Ruins seen from the Circular Church, Charleston, S.C., 1865. National Archives Identifier: 528788, Local Identifier: 111-B-4667 .

113. Ruins seen from the capitol, Columbia, S.C., 1865. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 533426, Local Identifier: 165-SC-53 .

114. Fort Sumter, S.C., viewed from a sandbar in Charleston Harbor, 1865. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Identifier: 533429, Local Identifier: 165-SC-56 .

115. Soldiers in the trenches before battle, Petersburg, Va., 1865. National Archives Identifier 524576, Local Identifier: 111-B-157 . (The Petersburg identification appearing in the official caption for this photograph received by NARA from the Army Signal Corps has been disputed. Civil War historians and photo-historians have uncovered documentary evidence suggesting that this image of Union forces was taken by Andrew J. Russell just before the Second Battle of Fredericksburg in the spring of 1863. For more information, please see the item in the National Archives Catalog .)

Richmond, Va.

116. High-angle view toward the capitol, 1862. National Archives Identifier: 524454, Local Identifier: 111-B-35 .

117. Ruins in front of the Capitol, 1865. National Archives Identifier: 524971, Local Identifier: 111-B-562 .

118. Silhouette of ruins of Haxall's mills, 1865, showing some of the destruction caused by a Confederate attempt to burn Richmond. National Archives Identifier: 524556, Local Identifier: 111-B-137 .

119. The "White House of the Confederacy," Jefferson Davis' home. National Archives Identifier: 524472, Local Identifier: 111-B-53 .

Washington, D.C., and Environs

120. The U.S. Capitol under construction, 1860. National Archives Identifier: 530494, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1480 .

121. Fort Massachusetts, sally port and soldiers, 1861. The fort was renamed Fort Stevens in 1863. National Archives Identifier: 524897, Local Identifier: 111-B-479 .

122. General view of 96th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment during drill at Camp Northumberland, with the camp in the background, 1861. National Archives Identifier: 524905, Local Identifier: 111-B-487 .

123. Barricades on Duke Street, Alexandria, Va., erected to protect the Orange and Alexandria Railroad from Confederate cavalry, 1861. National Archives Identifier: 524934, Local Identifier: 111-B-523 .

124. Slave pen of Price, Birch, & Co., Alexandria, Va., August 1863. Photographed by William R. Pywell. National Archives Identifier: 533276, Local Identifier: 165-SB-2 .

125. East front of Arlington Mansion (General Lee's home), with Union soldiers on the lawn, June 28, 1864. National Archives Identifier: 533118, Local Identifier: 165-C-518 .

126. Grand review of Union troops, May 23-24, 1865, looking down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the Capitol. Artwork by James E. Taylor, July 1, 1881. National Archives Identifier: 530486, Local Identifier: 111-BA-69 .

127. General view of the city from the south toward the Treasury Building and the White House. Cows are grazing near Tiber Creek. National Archives Identifier: 529253, Local Identifier: 111-B-5147 .

128. Smithsonian Institution Building in a field of daisies. National Archives Identifier: 528794, Local Identifier: 111-B-4672 .

Abolitionists

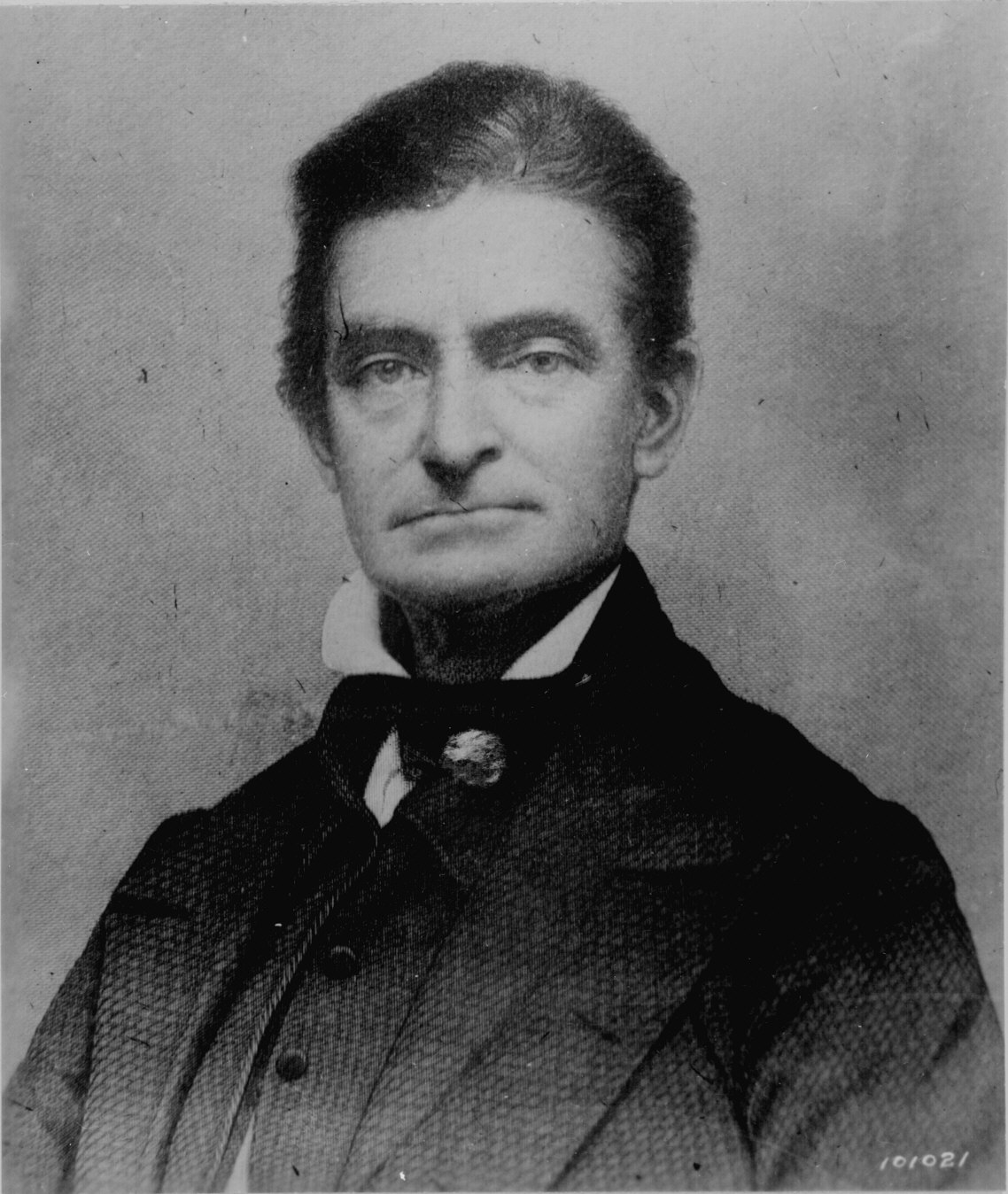

Brown, John; bust-length. Local Identifier: 111-SC-101021. National Archives Identifier: 531116.

129. Brown, John; bust-length. Engraving from daguerreotype, ca. 1856. National Archives Identifier: 531116, Local Identifier: 111-SC-101021 .

130. Douglass, Frederick; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 558770, Local Identifier: 200-FL-22 .

131. Garrison, William Lloyd; three-quarter-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 530489, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1088 .

132. Greeley, Horace; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 527435, Local Identifier: 111-B-3251 .

Artists and Authors

133. Brady, Mathew B., photographer; full-length seated. National Archives Identifier: 525281, Local Identifier: 111-B-1074 .

134. Brumidi, Constantino, artist who painted murals and frescoes in the Capitol; three-quarter-length, standing, holding brush and palette. National Archives Identifier: 527952, Local Identifier: 111-B-3791 .

135. Bryant, William Cullen, poet and editor of the New York Evening Post; full-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 526948, Local Identifier: 111-B-2764 .

136. Stowe, Harriet Beecher, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 535784, Local Identifier: 208-N-25004 .

137. Whitman, Walt, poet; half-length, seated, wearing hat. National Archives Identifier: 525875, Local Identifier: 111-B-1672 .

Confederate Army Officers

138. Beauregard, Gen. Pierre; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 525441, Local Identifier: 111-B-1233 .

139. Breckenridge, Lt. Gen. John C.; bust-length. National Archives Identifier: 530491, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1215 .

140. Gordon, Maj. Gen. John B.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 525987, Local Identifier: 111-B-1786 .

141. Hill, Lt. Gen. Ambrose P.; bust-length. National Archives Identifier: 530490, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1190 .

142. Hood, Gen. John B.; bust-length, in civilian clothes. National Archives Identifier: 529378, Local Identifier: 111-B-5274 .

143. Jackson, Lt. Gen. Thomas Jonathan ("Stonewall"); bust-length, April 1863. Photographed by George W Minnes. National Archives Identifier: 526067, Local Identifier: 111-B-1867 .

144. Johnston, Gen. Joseph E.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 525983, Local Identifier: 111-B-1782 .

145. Lee, Gen. Robert E.; full-length, standing, April 1865. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. National Archives Identifier: 525769, Local Identifier: 111-B-1564 .

146. Longstreet, Lt. Gen. James; half-length, in civilian clothes. National Archives Identifier: 526224, Local Identifier: 111-B-2028 .

147. Mahone, Maj. Gen. William; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 529228, Local Identifier: 111-B-5123 .

148. Mosby, Col. John Singleton; bust-length. National Archives Identifier: 530499, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1709 .

149. Stuart, Brig. Gen. James Ewell Brown ("Jeb"); three-quarter-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 518135, Local Identifier: 64-M-9 .

Confederate Officials

150. Benjamin, Judah P., Secretary of State; three- quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 526652, Local Identifier: 111-B-2458 .

151. Davis, Jefferson, President; three-quarter-length, standing. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady before the war. National Archives Identifier: 528293, Local Identifier: 111-B-4146 .

152. Mallory, Stephen R., Secretary of the Navy; three- quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 528705, Local Identifier: 111-B-4583 .

153. Stephens, Alexander H., Vice President; three- quarter-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 528288, Local Identifier: 111-B-4141 .

154. Mason, James M., Envoy to England; three quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 529268, Local Identifier: 111-B-5163 .

155. Seddon, James A., Secretary of War; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 530492, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1224 .

Enlisted Men

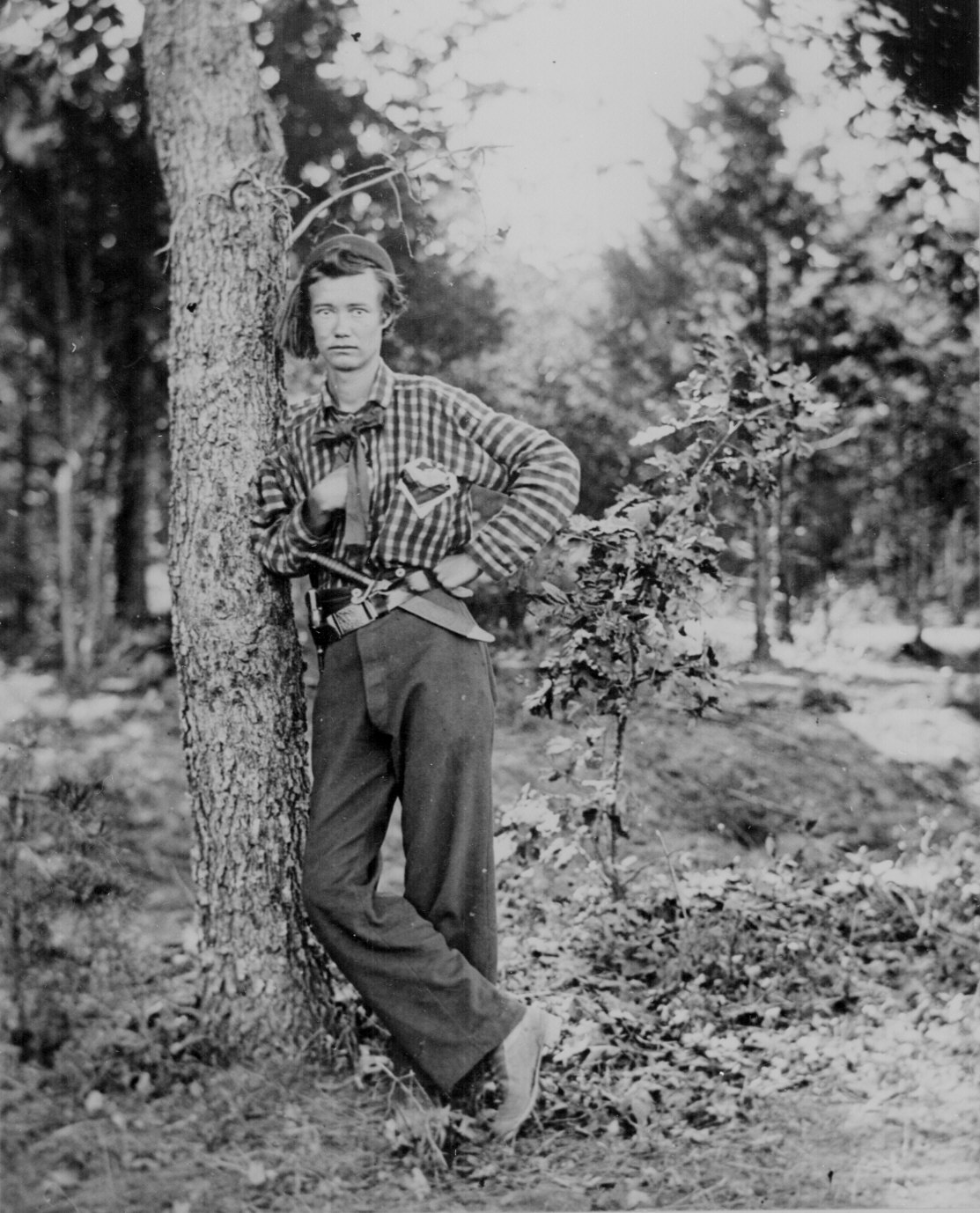

Kingin, Pvt. Emory Eugene. Local Identifier: 111-B-5348. National Archives Identifier: 529450.

156. Arnold, D. W. C., private in the Union Army. National Archives Identifier: 529535, Local Identifier: 111-B-5435 .

157. Kingin, Pvt. Emory Eugene, 4th Michigan Infantry; standing, full-length, leaning against a tree and wearing a plaid shirt. National Archives Identifier: 529450, Local Identifier: 111-B-5348 .

158. Marbury, Gilbert A., drummer, Company H, 22d New York Infantry; posing with drum. National Archives Identifier: 529594, Local Identifier: 111-B-5497 .

159. Ruffin, Pvt. Edmund, Confederate soldier who fired the first shot against Fort Sumter; full-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 530493, Local Identifier: 111-BA-1226 .

Federal Army Officers

160. Anderson, Maj. Robert, defender of Fort Sumter; full-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 528328, Local Identifier: 111-B-4183 .

161. Burnside, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 527863, Local Identifier: 111-B-3698 .

162. Butler, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F.; three-quarterlength. National Archives Identifier: 528659, Local Identifier: 111-B-4533 .

163. Custer, Maj. Gen. George A.; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 558719, Local Identifier: 200S-CA-10 .

164. Grant, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S.; three-quarter-length, standing. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. National Archives Identifier: 558720, Local Identifier: 200-CA-38 .

165. Halleck, Maj. Gen. Henry W. ("Old Brains"); three- quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 526731, Local Identifier: 111-B-2541 .

166. Hancock, Maj. Gen. Winfield S.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 529369, Local Identifier: 111-B-5265 .

167. Hooker, Maj. Gen. Joseph ("Fighting Joe"); full-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 526959, Local Identifier: 111-B-2775 .

168. McClellan, Maj. Gen. George B.; three-quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 528744, Local Identifier: 111-B-4624 .

169. McDowell, Maj. Gen. Irvin; three-quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 527993, Local Identifier: 111-B-3834 .

170. Meade, Maj. Gen. George G.; half-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 527851, Local Identifier: 111-B-3685 .

171. Pope, Brig. Gen. John; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 527743, Local Identifier: 111-B-3569 .

172. Rawlins, Brig. Gen. John A.; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 528564, Local Identifier: 111-B-4435 .

173. Rosecrans, Maj. Gen. William S.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 527814, Local Identifier: 111-B-3646 .

174. Scott, Lt. Gen. Winfield ("Old Fuss and Feathers"); half-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 528333, Local Identifier: 111-B-4188 .

175. Sheridan, Maj. Gen. Philip H.; three-quarter-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 526708, Local Identifier: 111-B-2520 .

176. Sherman, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 525970, Local Identifier: 111-B-1769 .

177. Thomas, Maj. Gen. George H.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 528908, Local Identifier: 111-B-4795 .

Federal Navy Officers

178. Dahlgren, Rear Adm. John A. B.; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 528718, Local Identifier: 111-B-4595.

179. Farragut, Rear Adm. David G.; three-quarter-length. National Archives Identifier: 529975, Local Identifier: 111-B-5889 .

180. Foote, Rear Adm. Andrew H.; three-quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 528018, Local Identifier: 111-B-3860 .

181. Porter, Rear Adm. David D.; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 528608, Local Identifier: 111-B-4480 .

Foreign Diplomats

182. Bruce, Sir Frederick, British Minister to the United States from March 1865; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 525715, Local Identifier: 111-B-1510 .

183. Lyons, Lord Richard B.P., British Minister to the United States from December 1858 to February 1865; full-length, seated. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. National Archives Identifier: 533231, Local Identifier: 165-JT-185 .

184. Romero, Senior Don Matias. Envoy of the Republic of Mexico, 1863; three-quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 525436 , Local Identifier: 111-B-1228.

U.S. Government Officials

185. Chase, Salmon P., Secretary of the Treasury; three- quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 528414, Local Identifier: 111-B-4270 .

186. Douglas, Stephen A., Senator from Illinois; three- quarter-length, standing. National Archives Identifier: 526540, Local Identifier: 111-B-2346 .

187. Johnson, Andrew, Vice President and President; three-quarter-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 528284, Local Identifier: 111-B-4138 .

188. Lincoln, Abraham; three-quarter-length, standing, ca. 1863. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. National Archives Identifier: 527823, Local Identifier: 111-B-3656 .

189. Seward, William H., Secretary of State; bust profile. National Archives Identifier: 528347, Local Identifier: 111-B-4204 .

190. Stanton, Edwin M., Secretary of War; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 528682, Local Identifier: 111-B-4559 .

191. Stevens, Thaddeus. Representative from Pennsylvania; half-length. National Archives Identifier: 525291, Local Identifier: 111-B-1084 .

192. Sumner, Charles, Senator from Massachusetts; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 530021, Local Identifier: 111-B-5937 .

193. Welles, Gideon, Secretary of the Navy; half-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 525398, Local Identifier: 111-B-1189 .

Miss Clara Barton. Local Identifier: 111-B-1857. National Archives Identifier: 526057.

194. Barton, Clara; three-quarter-length, seated. National Archives Identifier: 526057, Local Identifier: 111-B-1857 .