Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Staff Writer

Rob writes about the intersection of sleep and mental health and previously worked at the National Cancer Institute.

Want to read more about all our experts in the field?

Dr. Abhinav Singh

Sleep Medicine Physician

Dr. Singh is the Medical Director of the Indiana Sleep Center. His research and clinical practice focuses on the entire myriad of sleep disorders.

Sleep Foundation

Fact-Checking: Our Process

The Sleep Foundation editorial team is dedicated to providing content that meets the highest standards for accuracy and objectivity. Our editors and medical experts rigorously evaluate every article and guide to ensure the information is factual, up-to-date, and free of bias.

The Sleep Foundation fact-checking guidelines are as follows:

- We only cite reputable sources when researching our guides and articles. These include peer-reviewed journals, government reports, academic and medical associations, and interviews with credentialed medical experts and practitioners.

- All scientific data and information must be backed up by at least one reputable source. Each guide and article includes a comprehensive bibliography with full citations and links to the original sources.

- Some guides and articles feature links to other relevant Sleep Foundation pages. These internal links are intended to improve ease of navigation across the site, and are never used as original sources for scientific data or information.

- A member of our medical expert team provides a final review of the content and sources cited for every guide, article, and product review concerning medical- and health-related topics. Inaccurate or unverifiable information will be removed prior to publication.

- Plagiarism is never tolerated. Writers and editors caught stealing content or improperly citing sources are immediately terminated, and we will work to rectify the situation with the original publisher(s)

- Although Sleep Foundation maintains affiliate partnerships with brands and e-commerce portals, these relationships never have any bearing on our product reviews or recommendations. Read our full Advertising Disclosure for more information.

Table of Contents

What Are the Effects of Sleep Deprivation?

How much sleep is enough, symptoms of sleep deprivation, causes of sleep deprivation, treatment for sleep deprivation, preventing sleep issues.

Sleep deprivation happens when a person does not get the sleep they need to sustain their health and well-being. It is common for people to sacrifice sleep for work, school, or fun, but even one night of inadequate sleep can leave people feeling tired, less productive, and more prone to mistakes the next day.

Nearly half of people in the U.S. have trouble sleeping, and around one-third of adults sleep less than seven hours each night. Without enough sleep, the body begins to accumulate sleep debt.

As sleep debt grows over time, it begins to take a toll on mental and physical health . Long-term sleep deprivation can reduce quality of life and may increase the risk of health issues including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Learn more about the impacts of sleep deprivation, including its causes, and how prioritizing sleep hygiene can help people get the rest they need.

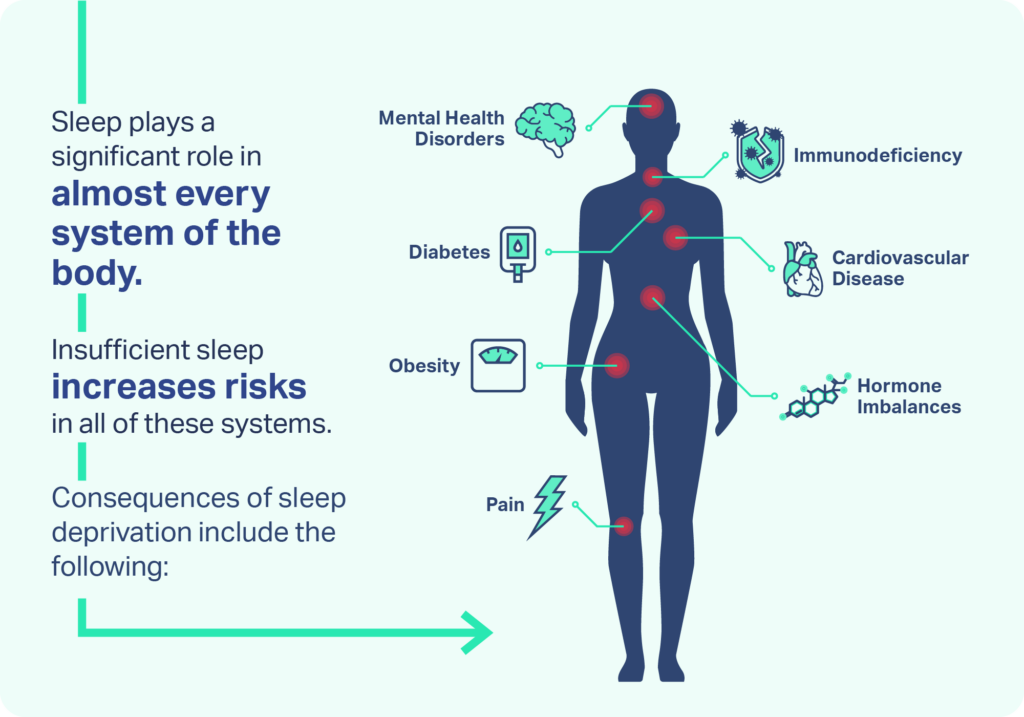

Research has found that sleep deprivation affects systems throughout the body, leading to a wide range of negative effects.

- Daytime sleepiness: Not getting enough sleep is a common cause of people feeling tired during the day Trusted Source UpToDate More than 2 million healthcare providers around the world choose UpToDate to help make appropriate care decisions and drive better health outcomes. UpToDate delivers evidence-based clinical decision support that is clear, actionable, and rich with real-world insights. View Source . Daytime sleepiness can leave a person without the energy to do the things they enjoy and cause problems at work, school, and in relationships.

- Impaired mental function: One of the most noticeable effects of sleep loss is cognitive impairment. As sleep debt grows Trusted Source Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) As the nation’s health protection agency, CDC saves lives and protects people from health threats. View Source , a person becomes less alert and may have difficulty multitasking. Reductions in attention make a sleep-deprived person more prone to mistakes, increasing the risk of a workplace or motor vehicle accident.

- Mood changes: Sleep loss can lead to mood changes and make a person feel more anxious or depressed. Without enough sleep, people may feel irritable, frustrated, and unmotivated. They may also struggle to deal with change and to regulate their emotions.

- Reduced immune function: Sleep is important for maintaining a healthy immune system, so sleep deprivation can weaken immune function. In fact, research suggests that people who are sleep deprived are less responsive to the flu vaccine and are more likely to get infections like the common cold.

- Weight gain: Sleep is important for maintaining a healthy weight Trusted Source National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) The NHLBI is the nation's leader in the prevention and treatment of heart, lung, blood and sleep disorders. View Source . Not getting enough sleep can affect appetite and metabolism in ways that can lead to weight gain. Insufficient sleep has been associated with an increased risk of obesity.

Sleep deprivation can have a drastic effect on the ability to safely drive a car. Not only does sleep loss reduce a person’s ability to pay attention Trusted Source National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) The NHLBI is the nation's leader in the prevention and treatment of heart, lung, blood and sleep disorders. View Source and react quickly , it can also lead to microsleeps, which involve unknowingly falling asleep for a brief moment. Drowsy driving is linked to tens of thousands of injuries Trusted Source National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Through enforcing vehicle performance standards and partnerships with state and local governments, NHTSA reduces deaths, injuries and economic losses from motor vehicle crashes. View Source and hundreds of deaths in the U.S. each year.

When sleep loss becomes a regular occurrence, chronic sleep deprivation can lead to changes in the nervous system, contribute to long-term health complications, and exacerbate chronic medical conditions.

- Diabetes: A lack of sleep can make it more difficult for the body to process sugar, contributing to glucose intolerance Trusted Source National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) NIDDK research creates knowledge about and treatments for diseases that are among the most chronic, costly, and consequential for patients, their families, and the Nation. View Source and increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes.

- Heart disease: During normal sleep, blood pressure drops in ways that are believed to support heart health. Sleep deprivation prevents this drop in blood pressure and triggers inflammation, heightening the risk of cardiovascular diseases , such as heart disease and stroke.

- Mental health conditions: Sleep deprivation is closely linked to mental health Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source . Sleep loss may increase the risk of mental health issues, and those issues can make it harder to get enough sleep.

Experts have created guidelines Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source for the amount of sleep needed to maintain optimal mental health, physical health, and emotional well-being. Without this amount of sleep, people begin to accumulate sleep debt and experience the consequences of sleep deprivation.

| Age Group | Age Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant | 4-12 months | 12-16 hours (including naps) |

| Toddler | 1-2 years | 11-14 hours (including naps) |

| Preschool | 3-5 years | 10-13 hours (including naps) |

| School-age | 6-12 years | 9-12 hours |

| Teen | 13-18 years | 8-10 hours |

| Adult | 18 years and older | 7 hours or more |

Sleep needs vary across the lifespan but also from person to person. This means that how much sleep an individual needs depends on more than just their age. For example, some people may be naturally long or naturally short sleepers who require more or less than the recommended number of hours to wake up feeling rested.

How much sleep a person needs also depends on their health and typical daily activities. In the short-term, the need for sleep is temporarily increased after demanding activities, when a person is sick, or when recovering from a period of sleep deprivation.

Additionally, avoiding sleep deprivation is about more than just spending enough hours in bed. Healthy and restorative rest also depends on the quality of sleep. So even if a person gets the right amount of hours of sleep, they may still be sleep deprived if their sleep quality is reduced from waking up too often at night.

The symptoms of sleep deprivation may be obvious or subtle depending on how much sleep is missed and how accustomed a person is to sleep deprivation. Signs to watch out for include:

- Waking up feeling unrefreshed

- Daytime sleepiness

- Falling asleep unexpectedly during the day

- Difficulty functioning at home, work, or school

- Trouble concentrating and slow reaction times

- Mood changes and problems controlling emotions

- Spending more than 30 minutes trying to fall asleep

- Feeling tiredness in the morning despite a full night of sleep

- Waking up frequently during the night

- Snoring loudly or gasping for air while sleeping

Some symptoms of sleep deprivation may look different in children than in adults. In addition to dozing off during the day, children with sleep deprivation may exhibit an increase in energy or hyperactivity. Children may also have frequent changes in mood, difficulty controlling their behavior, or poor academic achievement.

There are many potential causes of sleep deprivation, ranging from natural changes in the body as people age to an undiagnosed medical condition or sleep disorder.

In teens, sleep deprivation can develop because of changes during puberty that lead adolescents to prefer later bedtimes. This natural preference for late nights often conflicts with early morning school schedules, making it difficult for teens to get the sleep they need.

In women and people assigned female at birth, sleep loss can occur at certain times during their menstrual cycle. People commonly have fragmented sleep in the week before their period begins Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source . Sleep loss is also common during and after pregnancy and during menopause.

Other causes of sleep deprivation include poor sleep habits, busy schedules, and health issues that interfere with getting enough quality rest.

- Poor sleep habits: Daytime habits can either help or hinder nighttime sleep. Sleep deprivation can be caused by poor sleep habits, such as using a cell phone, TV, or other electronics in bed, drinking caffeine too close to bedtime, or having an inconsistent sleep schedule.

- Full schedules: A common reason for losing sleep is a busy schedule that involves activities in the late evening. People who work late or overbook themselves in the evening may sacrifice sleep in hopes of sleeping in on the weekend. Unfortunately, extra sleep on the weekend is not able to fully compensate for lost sleep during the week.

- Stress: Stress is a natural reaction to challenging situations, but if left unchecked it can make it more difficult to fall asleep Trusted Source Medline Plus MedlinePlus is an online health information resource for patients and their families and friends. View Source at night. Excess stress causes the body to release hormones that trigger alertness, which can interfere with normal sleep.

- Issues in the sleep environment: A person’s sleep environment can have a significant impact on their sleep. People who live in noisy areas may find it difficult to get quality sleep. Sleep can also be interrupted by too much ambient light and temperatures that are too hot or too cold.

- Medical conditions: Many medical problems can interfere with sleep, including pain, heart failure, and asthma. Some medical conditions may flare up Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source or get worse at night, like acid reflux or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Medications and substances: A wide variety of medications can interrupt sleep or make it more challenging to doze off. These include certain steroids, decongestants, pain medications, and drugs used to treat anxiety and depression.

- Mental health conditions: Several mental health conditions are linked to sleep challenges, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder, as well as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source , and autism spectrum disorder.

Another potential cause of sleep deprivation is an undiagnosed or untreated sleep disorder . In fact, as many as 70 million people in the U.S. live with a chronic sleep disorder. Sleep disorders that can make it difficult to get enough sleep include insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, and restless legs syndrome.

Treatment for sleep deprivation involves finding ways to get more hours of high-quality sleep. The best approach to achieving this depends on the cause of an individual’s sleep problems. In people with persistent sleep deprivation, it may take several weeks or longer Trusted Source Merck Manual|MSD Manuals View Source to resolve the symptoms of sleep loss.

When symptoms of sleep loss continue despite an improvement in sleep habits, working with a doctor is an important step in addressing the causes of sleep problems. To help determine the cause of sleep deprivation, a doctor may ask questions related to routines and sleep habits, such as:

- What time do you go to bed and wake up each day, including on the weekends?

- What is your work schedule?

- Is sleep refreshing or is it difficult to get up in the morning?

- Do you wake up often during the night?

- How often do you take daytime naps?

- Does daytime sleepiness ever interfere with your life?

Using this information, a doctor may recommend additional tests to find the source of sleep issues. A doctor may suggest starting a sleep diary to keep track of symptoms and habits that may be causing sleep deprivation.

To reduce the risk of sleep deprivation, it is important to take steps to improve sleep hygiene .

- Make sleep a priority: Prioritize sleep health by creating a comfortable sleep environment and keeping a consistent sleep schedule. This means going to sleep and waking up at around the same time each day and avoiding the temptation to stay up later or sleep in on the weekends.

- Combat stress: To combat bedtime stress, give yourself plenty of time to wind down from the day. Use this time to listen to calming music, stretch, or write in a journal. Boost your ability to relieve stress by trying out new relaxation techniques and seeing what helps the most.

- Time your light exposure: Ambient light can signal to the body whether it is time to be awake or prepare for sleep, so be intentional about light exposure. Try to get at least 30 minutes of sunlight exposure during the day and then dim or turn off lights in the evening. Shut off phones, TVs, and computers at least an hour before bed.

- Watch your caffeine intake: Caffeine can linger in the body for eight or more hours, so consuming caffeine in the afternoon may affect how long it takes to doze off at bedtime.

- Nap wisely: Although they cannot replace quality nighttime rest, naps can be a helpful tool to improve daytime alertness. If naps are too long or poorly timed, though, they can make it more difficult to fall asleep in the evening. Adults should aim for naps that are no longer than 20 minutes and should avoid napping in the late afternoon.

- Stay active: Regular exercise can make it easier to get to sleep at bedtime. Try to get at least 30 minutes of physical activity every day, but it is best to avoid highly strenuous exercise too close to bedtime.

Medical Disclaimer: The content on this page should not be taken as medical advice or used as a recommendation for any specific treatment or medication. Always consult your doctor before taking a new medication or changing your current treatment.

References 13 Sources

Cirelli, C. (2022, October 10). Insufficient sleep: Definition, epidemiology, and adverse outcomes. In R. Benca (Ed.). UpToDate., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2020, April 1). Sleep debt. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2011, August). Your guide to healthy sleep., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Sleep deprivation and deficiency., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (n.d.). Drowsy Driving., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2021, March 17). The impact of poor sleep on type 2 diabetes., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

Scott, A. J., Webb, T. L., & Rowse, G. (2017). Does improving sleep lead to better mental health? A protocol for a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ open, 7(9), e016873.

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.

Rajagopal, A., & Sigua, N. L. (2018). Women and sleep. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 197(11), P19–P20.

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (2022, April 30). Stress and your health. MedlinePlus., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

Shah, P., & Krishnan, V. (2019). Hospitalization and sleep. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 199(10), P19–P20.

Bandyopadhyay, A., & Sigua, N. L. (2019). What is sleep deprivation? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 199(6), P11–P12.

Schwab, R. J. (2022, May). Insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). Merck Manual Professional Version., Retrieved December 18, 2022, from

Learn More About Sleep Deprivation

Can a Lack of Sleep Cause Headaches?

How Sleep Deprivation Affects Your Heart

Interrupted Sleep: Causes & Helpful Tips

Sleep Deprivation: Symptoms, Treatment, & Effects

Lack of Sleep May Increase Calorie Consumption

Sleepless Nights: How to Function on No Sleep

What All-Nighters Do To Your Cognition

Sleep Deprivation and Reaction Time

Understanding Sleep Deprivation and New Parenthood

Other articles of interest, sleep solutions, sleep hygiene, sleep apnea.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Heart-Healthy Living

- High Blood Pressure

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Sleep Apnea

- Information & Resources on COVID-19

- The Heart Truth®

- Learn More Breathe Better®

- Blood Diseases & Disorders Education Program

- Publications and Resources

- Clinical Trials

- Blood Disorders and Blood Safety

- Sleep Science and Sleep Disorders

- Lung Diseases

- Health Disparities and Inequities

- Heart and Vascular Diseases

- Precision Medicine Activities

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Population and Epidemiology Studies

- Women’s Health

- Research Topics

- All Science A-Z

- Grants and Training Home

- Policies and Guidelines

- Funding Opportunities and Contacts

- Training and Career Development

- Email Alerts

- NHLBI in the Press

- Research Features

- Ask a Scientist

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Mission and Strategic Vision

- Divisions, Offices and Centers

- Advisory Committees

- Budget and Legislative Information

- Jobs and Working at the NHLBI

- Contact and FAQs

- NIH Sleep Research Plan

- < Back To Sleep Deprivation and Deficiency

- How Sleep Affects Your Health

- What Are Sleep Deprivation and Deficiency?

- What Makes You Sleep?

- How Much Sleep Is Enough

- Healthy Sleep Habits

MORE INFORMATION

Sleep Deprivation and Deficiency How Sleep Affects Your Health

Language switcher.

Getting enough quality sleep at the right times can help protect your mental health, physical health, quality of life, and safety.

How do I know if I’m not getting enough sleep?

Sleep deficiency can cause you to feel very tired during the day. You may not feel refreshed and alert when you wake up. Sleep deficiency also can interfere with work, school, driving, and social functioning.

How sleepy you feel during the day can help you figure out whether you're having symptoms of problem sleepiness.

You might be sleep deficient if you often feel like you could doze off while:

- Sitting and reading or watching TV

- Sitting still in a public place, such as a movie theater, meeting, or classroom

- Riding in a car for an hour without stopping

- Sitting and talking to someone

- Sitting quietly after lunch

- Sitting in traffic for a few minutes

Sleep deficiency can cause problems with learning, focusing, and reacting. You may have trouble making decisions, solving problems, remembering things, managing your emotions and behavior, and coping with change. You may take longer to finish tasks, have a slower reaction time, and make more mistakes.

Symptoms in children

The symptoms of sleep deficiency may differ between children and adults. Children who are sleep deficient might be overly active and have problems paying attention. They also might misbehave, and their school performance can suffer.

Sleep-deficient children may feel angry and impulsive, have mood swings, feel sad or depressed, or lack motivation.

Sleep and your health

The way you feel while you're awake depends in part on what happens while you're sleeping. During sleep, your body is working to support healthy brain function and support your physical health. In children and teens, sleep also helps support growth and development.

The damage from sleep deficiency can happen in an instant (such as a car crash), or it can harm you over time. For example, ongoing sleep deficiency can raise your risk of some chronic health problems. It also can affect how well you think, react, work, learn, and get along with others.

Mental health benefits

Sleep helps your brain work properly. While you're sleeping, your brain is getting ready for the next day. It's forming new pathways to help you learn and remember information.

Studies show that a good night's sleep improves learning and problem-solving skills. Sleep also helps you pay attention, make decisions, and be creative.

Studies also show that sleep deficiency changes activity in some parts of the brain. If you're sleep deficient, you may have trouble making decisions, solving problems, controlling your emotions and behavior, and coping with change. Sleep deficiency has also been linked to depression, suicide, and risk-taking behavior.

Children and teens who are sleep deficient may have problems getting along with others. They may feel angry and impulsive, have mood swings, feel sad or depressed, or lack motivation. They also may have problems paying attention, and they may get lower grades and feel stressed.

Physical health benefits

Sleep plays an important role in your physical health.

Good-quality sleep:

- Heals and repairs your heart and blood vessels.

- Helps support a healthy balance of the hormones that make you feel hungry (ghrelin) or full (leptin): When you don't get enough sleep, your level of ghrelin goes up and your level of leptin goes down. This makes you feel hungrier than when you're well-rested.

- Affects how your body reacts to insulin: Insulin is the hormone that controls your blood glucose (sugar) level. Sleep deficiency results in a higher-than-normal blood sugar level, which may raise your risk of diabetes.

- Supports healthy growth and development: Deep sleep triggers the body to release the hormone that promotes normal growth in children and teens. This hormone also boosts muscle mass and helps repair cells and tissues in children, teens, and adults. Sleep also plays a role in puberty and fertility.

- Affects your body’s ability to fight germs and sickness: Ongoing sleep deficiency can change the way your body’s natural defense against germs and sickness responds. For example, if you're sleep deficient, you may have trouble fighting common infections.

- Decreases your risk of health problems, including heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity, and stroke.

Research for Your Health

NHLBI-funded research found that adults who regularly get 7-8 hours of sleep a night have a lower risk of obesity and high blood pressure. Other NHLBI-funded research found that untreated sleep disorders rase the risk for heart problems and problems during pregnancy, including high blood pressure and diabetes.

Daytime performance and safety

Getting enough quality sleep at the right times helps you function well throughout the day. People who are sleep deficient are less productive at work and school. They take longer to finish tasks, have a slower reaction time, and make more mistakes.

After several nights of losing sleep — even a loss of just 1 to 2 hours per night — your ability to function suffers as if you haven't slept at all for a day or two.

Lack of sleep also may lead to microsleep. Microsleep refers to brief moments of sleep that happen when you're normally awake.

You can't control microsleep, and you might not be aware of it. For example, have you ever driven somewhere and then not remembered part of the trip? If so, you may have experienced microsleep.

Even if you're not driving, microsleep can affect how you function. If you're listening to a lecture, for example, you might miss some of the information or feel like you don't understand the point. You may have slept through part of the lecture and not realized it.

Some people aren't aware of the risks of sleep deficiency. In fact, they may not even realize that they're sleep deficient. Even with limited or poor-quality sleep, they may still think they can function well.

For example, sleepy drivers may feel able to drive. Yet studies show that sleep deficiency harms your driving ability as much or more than being drunk. It's estimated that driver sleepiness is a factor in about 100,000 car accidents each year, resulting in about 1,500 deaths.

Drivers aren't the only ones affected by sleep deficiency. It can affect people in all lines of work, including healthcare workers, pilots, students, lawyers, mechanics, and assembly line workers.

Lung Health Basics: Sleep

People with lung disease often have trouble sleeping. Sleep is critical to overall health, so take the first step to sleeping better: learn these sleep terms, and find out about treatments that can help with sleep apnea.

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Among teens, sleep deprivation an epidemic

Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts.

October 8, 2015 - By Ruthann Richter

The most recent national poll shows that more than 87 percent of U.S. high school students get far less than the recommended eight to 10 hours of sleep each night. Christopher Silas Neal

Carolyn Walworth, 17, often reaches a breaking point around 11 p.m., when she collapses in tears. For 10 minutes or so, she just sits at her desk and cries, overwhelmed by unrelenting school demands. She is desperately tired and longs for sleep. But she knows she must move through it, because more assignments in physics, calculus or French await her. She finally crawls into bed around midnight or 12:30 a.m.

The next morning, she fights to stay awake in her first-period U.S. history class, which begins at 8:15. She is unable to focus on what’s being taught, and her mind drifts. “You feel tired and exhausted, but you think you just need to get through the day so you can go home and sleep,” said the Palo Alto, California, teen. But that night, she will have to try to catch up on what she missed in class. And the cycle begins again.

“It’s an insane system. … The whole essence of learning is lost,” she said.

Walworth is among a generation of teens growing up chronically sleep-deprived. According to a 2006 National Sleep Foundation poll, the organization’s most recent survey of teen sleep, more than 87 percent of high school students in the United States get far less than the recommended eight to 10 hours, and the amount of time they sleep is decreasing — a serious threat to their health, safety and academic success. Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts. It’s a problem that knows no economic boundaries.

While studies show that both adults and teens in industrialized nations are becoming more sleep deprived, the problem is most acute among teens, said Nanci Yuan , MD, director of the Stanford Children’s Health Sleep Center . In a detailed 2014 report, the American Academy of Pediatrics called the problem of tired teens a public health epidemic.

“I think high school is the real danger spot in terms of sleep deprivation,” said William Dement , MD, PhD, founder of the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic , the first of its kind in the world. “It’s a huge problem. What it means is that nobody performs at the level they could perform,” whether it’s in school, on the roadways, on the sports field or in terms of physical and emotional health.

Social and cultural factors, as well as the advent of technology, all have collided with the biology of the adolescent to prevent teens from getting enough rest. Since the early 1990s, it’s been established that teens have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later — as much as two hours later — than their younger counterparts.

Yet when they enter their high school years, they find themselves at schools that typically start the day at a relatively early hour. So their time for sleep is compressed, and many are jolted out of bed before they are physically or mentally ready. In the process, they not only lose precious hours of rest, but their natural rhythm is disrupted, as they are being robbed of the dream-rich, rapid-eye-movement stage of sleep, some of the deepest, most productive sleep time, said pediatric sleep specialist Rafael Pelayo , MD, with the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic.

“When teens wake up earlier, it cuts off their dreams,” said Pelayo, a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “We’re not giving them a chance to dream.”

Teens have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later, yet many high schools start the day at a relatively early hour, disrupting their natural rhythym. Monkey Business/Fotolia

Understanding teen sleep

On a sunny June afternoon, Dement maneuvered his golf cart, nicknamed the Sleep and Dreams Shuttle, through the Stanford University campus to Jerry House, a sprawling, Mediterranean-style dormitory where he and his colleagues conducted some of the early, seminal work on sleep, including teen sleep.

Beginning in 1975, the researchers recruited a few dozen local youngsters between the ages of 10 and 12 who were willing to participate in a unique sleep camp. During the day, the young volunteers would play volleyball in the backyard, which faces a now-barren Lake Lagunita, all the while sporting a nest of electrodes on their heads.

At night, they dozed in a dorm while researchers in a nearby room monitored their brain waves on 6-foot electroencephalogram machines, old-fashioned polygraphs that spit out wave patterns of their sleep.

One of Dement’s colleagues at the time was Mary Carskadon, PhD, then a graduate student at Stanford. They studied the youngsters over the course of several summers, observing their sleep habits as they entered puberty and beyond.

Dement and Carskadon had expected to find that as the participants grew older, they would need less sleep. But to their surprise, their sleep needs remained the same — roughly nine hours a night — through their teen years. “We thought, ‘Oh, wow, this is interesting,’” said Carskadon, now a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University and a nationally recognized expert on teen sleep.

Moreover, the researchers made a number of other key observations that would plant the seed for what is now accepted dogma in the sleep field. For one, they noticed that when older adolescents were restricted to just five hours of sleep a night, they would become progressively sleepier during the course of the week. The loss was cumulative, accounting for what is now commonly known as sleep debt.

“The concept of sleep debt had yet to be developed,” said Dement, the Lowell W. and Josephine Q. Berry Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. It’s since become the basis for his ongoing campaign against drowsy driving among adults and teens. “That’s why you have these terrible accidents on the road,” he said. “People carry a large sleep debt, which they don’t understand and cannot evaluate.”

The researchers also noticed that as the kids got older, they were naturally inclined to go to bed later. By the early 1990s, Carskadon established what has become a widely recognized phenomenon — that teens experience a so-called sleep-phase delay. Their circadian rhythm — their internal biological clock — shifts to a later time, making it more difficult for them to fall asleep before 11 p.m.

Teens are also biologically disposed to a later sleep time because of a shift in the system that governs the natural sleep-wake cycle. Among older teens, the push to fall asleep builds more slowly during the day, signaling them to be more alert in the evening.

“It’s as if the brain is giving them permission, or making it easier, to stay awake longer,” Carskadon said. “So you add that to the phase delay, and it’s hard to fight against it.”

Pressures not to sleep

After an evening with four or five hours of homework, Walworth turns to her cellphone for relief. She texts or talks to friends and surfs the Web. “It’s nice to stay up and talk to your friends or watch a funny YouTube video,” she said. “There are plenty of online distractions.”

While teens are biologically programmed to stay up late, many social and cultural forces further limit their time for sleep. For one, the pressure on teens to succeed is intense, and they must compete with a growing number of peers for college slots that have largely remained constant. In high-achieving communities like Palo Alto, that translates into students who are overwhelmed by additional homework for Advanced Placement classes, outside activities such as sports or social service projects, and in some cases, part-time jobs, as well as peer, parental and community pressures to excel.

William Dement

At the same time, today’s teens are maturing in an era of ubiquitous electronic media, and they are fervent participants. Some 92 percent of U.S. teens have smartphones, and 24 percent report being online “constantly,” according to a 2015 report by the Pew Research Center. Teens have access to multiple electronic devices they use simultaneously, often at night. Some 72 percent bring cellphones into their bedrooms and use them when they are trying to go to sleep, and 28 percent leave their phones on while sleeping, only to be awakened at night by texts, calls or emails, according to a 2011 National Sleep Foundation poll on electronic use. In addition, some 64 percent use electronic music devices, 60 percent use laptops and 23 percent play video games in the hour before they went to sleep, the poll found. More than half reported texting in the hour before they went to sleep, and these media fans were less likely to report getting a good night’s sleep and feeling refreshed in the morning. They were also more likely to drive when drowsy, the poll found.

The problem of sleep-phase delay is exacerbated when teens are exposed late at night to lit screens, which send a message via the retina to the portion of the brain that controls the body’s circadian clock. The message: It’s not nighttime yet.

Yuan, a clinical associate professor of pediatrics, said she routinely sees young patients in her clinic who fall asleep at night with cellphones in hand.

“With academic demands and extracurricular activities, the kids are going nonstop until they fall asleep exhausted at night. There is not an emphasis on the importance of sleep, as there is with nutrition and exercise,” she said. “They say they are tired, but they don’t realize they are actually sleep-deprived. And if you ask kids to remove an activity, they would rather not. They would rather give up sleep than an activity.”

The role of parents

Adolescents are also entering a period in which they are striving for autonomy and want to make their own decisions, including when to go to sleep. But studies suggest adolescents do better in terms of mood and fatigue levels if parents set the bedtime — and choose a time that is realistic for the child’s needs. According to a 2010 study published in the journal Sleep , children are more likely to be depressed and to entertain thoughts of suicide if a parent sets a late bedtime of midnight or beyond.

In families where parents set the time for sleep, the teens’ happier, better-rested state “may be a sign of an organized family life, not simply a matter of bedtime,” Carskadon said. “On the other hand, the growing child and growing teens still benefit from someone who will help set the structure for their lives. And they aren’t good at making good decisions.”

They say they are tired, but they don’t realize they are actually sleep-deprived. And if you ask kids to remove an activity, they would rather not. They would rather give up sleep than an activity.

According to the 2011 sleep poll, by the time U.S. students reach their senior year in high school, they are sleeping an average of 6.9 hours a night, down from an average of 8.4 hours in the sixth grade. The poll included teens from across the country from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

American teens aren’t the worst off when it comes to sleep, however; South Korean adolescents have that distinction, sleeping on average 4.9 hours a night, according to a 2012 study in Sleep by South Korean researchers. These Asian teens routinely begin school between 7 and 8:30 a.m., and most sign up for additional evening classes that may keep them up as late as midnight. South Korean adolescents also have relatively high suicide rates (10.7 per 100,000 a year), and the researchers speculate that chronic sleep deprivation is a contributor to this disturbing phenomenon.

By contrast, Australian teens are among those who do particularly well when it comes to sleep time, averaging about nine hours a night, possibly because schools there usually start later.

Regardless of where they live, most teens follow a pattern of sleeping less during the week and sleeping in on the weekends to compensate. But many accumulate such a backlog of sleep debt that they don’t sufficiently recover on the weekend and still wake up fatigued when Monday comes around.

Moreover, the shifting sleep patterns on the weekend — late nights with friends, followed by late mornings in bed — are out of sync with their weekday rhythm. Carskadon refers to this as “social jet lag.”

“Every day we teach our internal circadian timing system what time it is — is it day or night? — and if that message is substantially different every day, then the clock isn’t able to set things appropriately in motion,” she said. “In the last few years, we have learned there is a master clock in the brain, but there are other clocks in other organs, like liver or kidneys or lungs, so the master clock is the coxswain, trying to get everybody to work together to improve efficiency and health. So if the coxswain is changing the pace, all the crew become disorganized and don’t function well.”

This disrupted rhythm, as well as the shortage of sleep, can have far-reaching effects on adolescent health and well-being, she said.

“It certainly plays into learning and memory. It plays into appetite and metabolism and weight gain. It plays into mood and emotion, which are already heightened at that age. It also plays into risk behaviors — taking risks while driving, taking risks with substances, taking risks maybe with sexual activity. So the more we look outside, the more we’re learning about the core role that sleep plays,” Carskadon said.

Many studies show students who sleep less suffer academically, as chronic sleep loss impairs the ability to remember, concentrate, think abstractly and solve problems. In one of many studies on sleep and academic performance, Carskadon and her colleagues surveyed 3,000 high school students and found that those with higher grades reported sleeping more, going to bed earlier on school nights and sleeping in less on weekends than students who had lower grades.

Sleep is believed to reinforce learning and memory, with studies showing that people perform better on mental tasks when they are well-rested. “We hypothesize that when teens sleep, the brain is going through processes of consolidation — learning of experiences or making memories,” Yuan said. “It’s like your brain is filtering itself — consolidating the important things and filtering out those unimportant things.” When the brain is deprived of that opportunity, cognitive function suffers, along with the capacity to learn.

“It impacts academic performance. It’s harder to take tests and answer questions if you are sleep-deprived,” she said.

That’s why cramming, at the expense of sleep, is counterproductive, said Pelayo, who advises students: Don’t lose sleep to study, or you’ll lose out in the end.

The panic attack

Chloe Mauvais, 16, hit her breaking point at the end of a very challenging sophomore year when she reached “the depths of frustration and anxiety.” After months of late nights spent studying to keep up with academic demands, she suffered a panic attack one evening at home.

“I sat in the living room in our house on the ground, crying and having horrible breathing problems,” said the senior at Menlo-Atherton High School. “It was so scary. I think it was from the accumulated stress, the fear over my grades, the lack of sleep and the crushing sense of responsibility. High school is a very hard place to be.”

We hypothesize that when teens sleep, the brain is going through processes of consolidation — learning of experiences or making memories. It’s like your brain is filtering itself.

Where she once had good sleep habits, she had drifted into an unhealthy pattern of staying up late, sometimes until 3 a.m., researching and writing papers for her AP European history class and prepping for tests.

“I have difficulty remembering events of that year, and I think it’s because I didn’t get enough sleep,” she said. “The lack of sleep rendered me emotionally useless. I couldn’t address the stress because I had no coherent thoughts. I couldn’t step back and have perspective. … You could probably talk to any teen and find they reach their breaking point. You’ve pushed yourself so much and not slept enough and you just lose it.”

The experience was a kind of wake-up call, as she recognized the need to return to a more balanced life and a better sleep pattern, she said. But for some teens, this toxic mix of sleep deprivation, stress and anxiety, together with other external pressures, can tip their thinking toward dire solutions.

Research has shown that sleep problems among adolescents are a major risk factor for suicidal thoughts and death by suicide, which ranks as the third-leading cause of fatalities among 15- to 24-year-olds. And this link between sleep and suicidal thoughts remains strong, independent of whether the teen is depressed or has drug and alcohol issues, according to some studies.

“Sleep, especially deep sleep, is like a balm for the brain,” said Shashank Joshi, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford. “The better your sleep, the more clearly you can think while awake, and it may enable you to seek help when a problem arises. You have your faculties with you. You may think, ‘I have 16 things to do, but I know where to start.’ Sleep deprivation can make it hard to remember what you need to do for your busy teen life. It takes away the support, the infrastructure.”

Sleep is believed to help regulate emotions, and its deprivation is an underlying component of many mood disorders, such as anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder. For students who are prone to these disorders, better sleep can help serve as a buffer and help prevent a downhill slide, Joshi said.

Rebecca Bernert, PhD, who directs the Suicide Prevention Research Lab at Stanford, said sleep may affect the way in which teens process emotions. Her work with civilians and military veterans indicates that lack of sleep can make people more receptive to negative emotional information, which they might shrug off if they were fully rested, she said.

“Based on prior research, we have theorized that sleep disturbances may result in difficulty regulating emotional information, and this may lower the threshold for suicidal behaviors among at-risk individuals,” said Bernert, an instructor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. Now she’s studying whether a brief nondrug treatment for insomnia reduces depression and risk for suicide.

Sleep deprivation also has been shown to lower inhibitions among both adults and teens. In the teen brain, the frontal lobe, which helps restrain impulsivity, isn’t fully developed, so teens are naturally prone to impulsive behavior. “When you throw into the mix sleep deprivation, which can also be disinhibiting, mood problems and the normal impulsivity of adolescence, then you have a potentially dangerous situation,” Joshi said.

Some schools shift

Given the health risks associated with sleep problems, school districts around the country have been looking at one issue over which they have some control: when school starts in the morning. The trend was set by the town of Edina, Minnesota, a well-to-do suburb of Minneapolis, which conducted a landmark experiment in student sleep in the late 1990s. It shifted the high school’s start time from 7:20 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. and then asked University of Minnesota researchers to look at the impact of the change. The researchers found some surprising results: Students reported feeling less depressed and less sleepy during the day and more empowered to succeed. There was no comparable improvement in student well-being in surrounding school districts where start times remained the same.

With these findings in hand, the entire Minneapolis Public School District shifted start times for 57,000 students at all of its schools in 1997 and found similarly positive results. Attendance rates rose, and students reported getting an hour’s more sleep each school night — or a total of five more hours of sleep a week — countering skeptics who argued that the students would respond by just going to bed later.

For the health and well-being of the nation, we should all be taking better care of our sleep, and we certainly should be taking better care of the sleep of our youth.

Other studies have reinforced the link between later start times and positive health benefits. One 2010 study at an independent high school in Rhode Island found that after delaying the start time by just 30 minutes, students slept more and showed significant improvements in alertness and mood. And a 2014 study in two counties in Virginia found that teens were much less likely to be involved in car crashes in a county where start times were later, compared with a county with an earlier start time.

Bolstered by the evidence, the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2014 issued a strong policy statement encouraging middle and high school districts across the country to start school no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to help preserve the health of the nation’s youth. Some districts have heeded the call, though the decisions have been hugely contentious, as many consider school schedules sacrosanct and cite practical issues, such as bus schedules, as obstacles.

In Fairfax County, Virginia, it took a decade of debate before the school board voted in 2014 to push back the opening school bell for its 57,000 students. And in Palo Alto, where a recent cluster of suicides has caused much communitywide soul-searching, the district superintendent issued a decision in the spring, over the strenuous objections of some teachers, students and administrators, to eliminate “zero period” for academic classes — an optional period that begins at 7:20 a.m. and is generally offered for advanced studies.

Certainly, changing school start times is only part of the solution, experts say. More widespread education about sleep and more resources for students are needed. Parents and teachers need to trim back their expectations and minimize pressures that interfere with teen sleep. And there needs to be a cultural shift, including a move to discourage late-night use of electronic devices, to help youngsters gain much-needed rest.

“At some point, we are going to have to confront this as a society,” Carskadon said. “For the health and well-being of the nation, we should all be taking better care of our sleep, and we certainly should be taking better care of the sleep of our youth.”

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Hope amid crisis

Psychiatry’s new frontiers

- Previous Article

- Next Article

To Study or to Sleep: How Seeing the Effect of Sleep Deprivation Changed Students’ Choices

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Vincent P. Coletta; To Study or to Sleep: How Seeing the Effect of Sleep Deprivation Changed Students’ Choices. Phys. Teach. 1 April 2020; 58 (4): 244–246. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.5145469

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Adequate sleep is essential for students to be able to solve challenging problems effectively. After many years of advising students to get enough sleep the night before their final exam, two studies were conducted with students in introductory physics classes to investigate their sleep habits. In the first previously published study, few students got adequate sleep and there was a significant positive correlation between hours of sleep and final exam score. In the second study the following semester, students were shown the results of the first study. Showing students the negative effect that sleep deprivation the night before a final exam had on exam scores in a prior class appears to have changed students’ sleep choices the night before their own final exam, based on students’ self-reports of sleep. Once students saw evidence that staying up all night studying for a final exam would likely hurt their score on the exam, class average hours of reported sleep significantly increased.

Citing articles via

- Online ISSN 1943-4928

- Print ISSN 0031-921X

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

Theses on Sleep

Summary: In this essay, I question some of the consensus beliefs about sleep, such as the need for at least 7 hours of sleep for adults, harmfulness of acute sleep deprivation, and harmfulness of long-term sleep deprivation and our inability to adapt to it.

It appears that the evidence for all of these beliefs is much weaker than sleep scientists and public health experts want us to believe. In particular, I conclude that it’s plausible that at least acute sleep deprivation is not only not harmful but beneficial in some contexts and that it’s that we are able to adapt to long-term sleep deprivation.

I also discuss the bidirectional relationship of sleep and mania/depression and the costs of unnecessary sleep, noting that sleeping 1.5 hours per day less results in gaining more than a month of wakefulness per year, every year.

Note: I sleep the normal 7-9 hours if I don’t restrict my sleep. However, stimulants like coffee, modafinil, and adderall seem to have much smaller effect on my cognition than on cognition of most people I know. My brain in general, as you might guess from reading this site , is not very normal. So, be cautious before trying anything with your sleep on the basis of the arguments I lay out below. Specifically do not make any drastic changes to your sleep schedule on the basis of reading this essay and, if you want to experiment with sleep, do it gradually (i.e. varying the average amount of sleep by no more than 30 minutes at a time) and carefully.

Also see Natália Coelho Mendonça Counter-theses on Sleep .

Comfortable modern sleep is an unnatural superstimulus. Sleepiness, just like hunger, is normal.

The default argument for sleeping 7-9 hours a night is that this is the amount of sleep most of us get “naturally” when we sleep without using alarms. In this section, I argue against this line of reasoning, using the following analogy:

- Experiencing hunger is normal and does not necessarily imply that you are not eating enough. Never being hungry means you are probably eating too much.

- Experiencing sleepiness is normal and does not necessarily imply that you are undersleeping. Never being sleepy means you are probably sleeping too much.

Most of us (myself included) eat a lot of junk food and candy if we don’t restrict ourselves. Does this mean that lots of junk food and candy is the “natural” or the “optimal” amount for health?

Obviously, no. Modern junk food and candy are unnatural superstimuli, much tastier and much more abundant than any natural food, so they end up overwhelming our brains with pleasure, especially given that we are bored at work, college, or in high school so much of the day.

What if the only food available to you was junk food and candy?

- If you don’t eat any, you starve.

- If you eat just enough to be lean, you’ll keep salivating at the sight of pizzas and ice cream and feel distracted and hungry all the time. Importantly, in this situation, the feeling of hunger does not mean that you should eat more – it’s your brain being overpowered by a superstimulus while being bored.

- And if you eat way too much candy or pizza at once, you’ll be feeling terrible afterwards, however tasty the food was.

Most of us (myself included) sleep 7-9 hours if we don’t have any alarms in the morning and if we get out of bed when we feel like it. Does this mean that 7-9 hours of sleep is the “natural” or the “optimal” amount?

My thesis is: obviously, no. Modern sleep, in its infinite comfort, is an unnatural superstimulus that overwhelms our brains with pleasure and comfort (note: I’m not saying that it’s bad, simply that being in bed today is much more pleasurable than being in “bed” in the past.)

Think about sleep 10,000 years ago. You sleep in a cave, in a hut, or under the sky, with predators and enemy tribes roaming around. You are on a wooden floor, on an animal’s skin, or on the ground. The temperature will probably drop 5-10°C overnight, meaning that if you were comfortable when you were falling asleep, you are going to be freezing when you wake up. Finally, there’s moon shining right at you and all kinds of sounds coming from the forest around you.

In contrast, today: you sleep on your super-comfortable machine-crafted foam of the exact right firmness for you. You are completely safe in your home, protected by thick walls and doors. Your room’s temperature stays roughly constant, ensuring that you stay warm and comfy throughout the night. Finally, you are in a light and sound-insulated environment of your house. And if there’s any kind of disturbance you have eye masks and earplugs.

Does this sound “natural”?

Now, what if the only sleep available to you was modern sleep?

- If you don’t sleep at all, you go crazy, because some amount of sleep is necessary.

- If you sleep just enough to be awake during the day, you’ll be dreaming of getting a nap at the sight of a bed and will be distracted and sleepy all the time. Importantly, I claim, in this situation, the feeling of sleepiness does not mean that you should sleep more – it’s your brain being overpowered by a superstimulus while being bored.

- And if you sleep way too much at once, you’ll be feeling terrible afterwards, however pleasant the sleep was.

Even if I convinced you about the “sleeping too much” part, you are still probably wondering: but what does depression have to do with anything? Isn’t sleeping a lot good for mental health? Well…

Depression <-> oversleeping. Mania <-> acute sleep deprivation

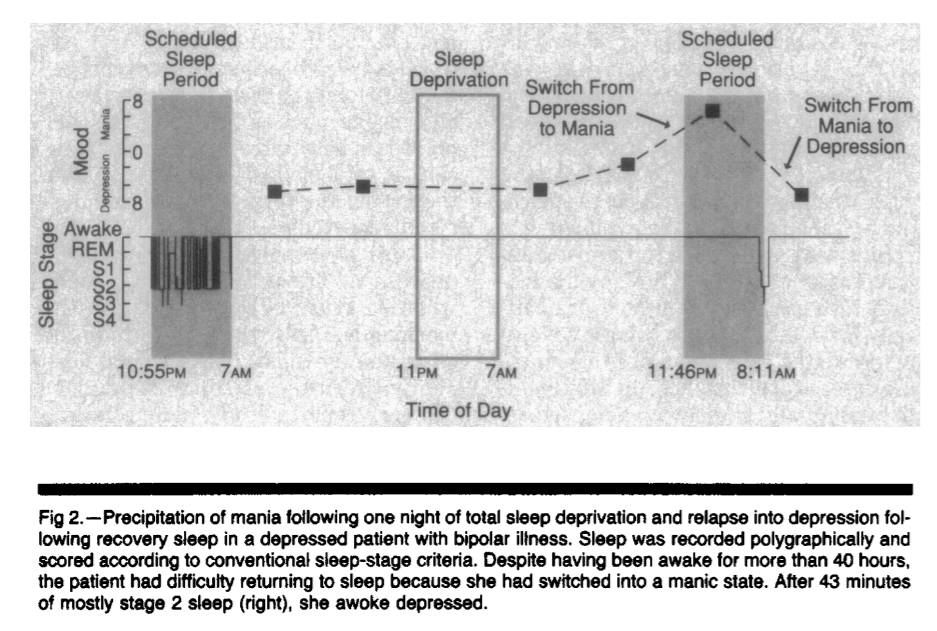

In this section, I argue that depression triggers/amplifies oversleeping while oversleeping triggers/amplifies depression. Similarly, mania triggers/amplifies acute sleep deprivation while acute sleep deprivation triggers/amplifies mania.

One of the most notable facts about sleep is just how interlinked excessive sleep is with depression and how interlinked sleep deprivation is with mania in bipolar people.

Someone in r/BipolarReddit asked: How many hours do you sleep when stable vs (hypo)manic? Depressed?

Here are all 8 answers that compare hours for manic and depressed states, I excluded answers that describe hypomania but do not describe mania or that only describe mania or only describe depression. note the consistency:

- “Manic/hypomanic: 0-6 hours Stable: 7-9 hours Depressed: 10-19 hours”

- “Manic, 2-3, hypo, 5-6, stable 8-9, depressed 10-12. 8 is the number I try to hit.”

- “Severely depressed w/o mixed features - 12 to 15 hours Low to Moderate depressed w/o mixed - 10 hours, if no alarm. With alarm less, but super hangover Stable -Usually 7-9 hours Hypomanic taking sedating evening meds - 5 to 7 hours Hypomanic with no sedating evening meds - 3 to 5 hours Manic out of hand - 0 to 3 hours Manic in hospital put on maximum sedating meds or injections - 4 to 6 hours Mixed episodes = same as hypo(manic)”

- “I try to get at least 8 hours but when I’m depressed I nap a lot. When I’m hypo I sleep pretty much the same but when I’m manic I’m lucky to get 3 hours. Huhs”

- “Just got out of a manic episode. A few all-nighters, a lot of 3 hour nights, and a good night of sleep was 6 hours. Now I’m depressed and I’ve been sleeping from 9pm to noon and staying in bed for much longer after I’m awake.”

- “Manic 2-4, stable 6-7, depressed 10-12”

- “Around 15 hours of sleep per night while depressed, and between 0-4 hours per night while manic.”

Lack of sleep is such a potent trigger for mania that acute sleep deprivation is literally used to treat depression. Aside from ketamine, not sleeping for a night is the only medicine we have to quickly – literally overnight – and reliably (in ~50% of patients) improve mood in depressed patients (until they go to bed, unless you keep advancing their sleep phase Riemann, D., König, A., Hohagen, F., Kiemen, A., Voderholzer, U., Backhaus, J., Bunz, J., Wesiack, B., Hermle, L. and Berger, M., 1999. How to preserve the antidepressive effect of sleep deprivation: A comparison of sleep phase advance and sleep phase delay. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 249(5), pp.231-237. ). NOTE: DO NOT TRY THIS IF YOU ARE BIPOLAR, YOU MIGHT GET A MANIC EPISODE.

Figure 1. Copied from Wehr TA. Improvement of depression and triggering of mania by sleep deprivation. JAMA. 1992 Jan 22;267(4):548-51.

Why does the lack of sleep promote manic states while long sleep promotes depression? I don’t know. But here are a couple of pointers to interesting papers relevant to the question: Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic? Beersma DG, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic?. Journal of affective disorders. 1992 Feb 1;24(2):101-8. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is associated with synapse growth. Sleep deprivation appears to increase BDNF [and therefore neurogenesis?]. Papers that showed up when I googled “sleep deprivation bdnf”: The Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: Missing Link Between Sleep Deprivation, Insomnia, and Depression . Rahmani M, Rahmani F, Rezaei N. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor: missing link between sleep deprivation, insomnia, and depression. Neurochemical research. 2020 Feb;45(2):221-31. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF . Eckert A, Karen S, Beck J, Brand S, Hemmeter U, Hatzinger M, Holsboer-Trachsler E. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF. European Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;41(S1):S282-. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia? . Giese M, Unternährer E, Hüttig H, Beck J, Brand S, Calabrese P, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Eckert A. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia?. Molecular psychiatry. 2014 Feb;19(2):151-2. Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation . Goldschmied JR, Rao H, Dinges D, Goel N, Detre JA, Basner M, Sheline YI, Thase ME, Gehrman PR. 0886 Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation. Sleep. 2019 Apr;42(Supplement_1):A356-.

Jeremy Hadfield writes:

My (summarized/simplified) hypothesis based on what I’ve read: depression involves rigid, non-flexible brain states that correspond to rigid depressive world models. Depression also involves a non-updating of models or inability to draw new connections (brain is even literally slightly lighter in depressed patients). Sleep involves revising/simplifying world models based on connections learned during the day, involves pruning unneeded or irrelevant synaptic connections. Thus, excessive sleep + depression = even less world model updating, even more rigid brain, even fewer new connections. Sleep deprivation can resolve this problem at least temporarily by ensuring that you stay awake for longer and keep adding connections, thus compensating for the decreased connection-building caused by depression and “forcing” a brain update (perhaps through neural annealing - see QRI article).

Occasional acute sleep deprivation is good for health and promotes more efficient sleep

One other argument for sleeping the “natural” (7-9) number of hours is that we feel bad on days when we sleep less. In this section, I argue against this line of reasoning by asking: if fasting and exercising are good, shouldn’t acute sleep deprivation also be good? And I conclude that it is probably good.

Let’s continue our analogy of sleep to eating and add exercise to the mix.

It seems to me that most common arguments against acute sleep deprivation equally “demonstrate” that fasting and exercise are bad.

For example, I ran 7 kilometers 2 days ago and my legs still hurt like hell and I can’t run at all. Does this mean that running is “bad”?

Well, consensus seems to be that dizziness, muscle damage (and thus pain) and decreased physical performance after the run, are not just not bad, but are in fact necessary for the organism to train to run faster or to run longer distances by increasing muscle mass, muscle efficiency, and lung capacity.

What about fasting? When I fast, I am more anxious, I think about food a lot, meaning that focus is more difficult, and I feel cold. And if I decided to fast too much, I would pass out and then die. Does this mean that fasting is “bad”? Well, consensus seems to be that occasional fasting actually activates some “good” kind of stress, promotes healthy autophagy, (obviously) helps to lose weight, etc. and is in fact good.

Now, what happens when I sleep for 2 hours instead of 7 one night? I feel somewhat tingly in my hands, my mood is heightened a little bit, and, if I start watching a movie with my wife at 6pm, I’ll fall asleep. Does this mean that sleeping 2 hours one night is bad for my health?

Obviously no. The only thing we observe is that my organism was subjected to acute stress. However, the reaction to acute stress does not tell us anything about the long-term effects of this kind of stress. As we know, both in running and in fasting, short-term acute stress response results in adaptation and in long-term increase in performance and in benefit to the organism.

I combed through a lot of sleep literature and I haven’t seen a single study that made a parallel to either fasting or exercise and I haven’t seen a single pre-registered RCT that tried to see what happens to someone if you subject them to 1-3 nights per week of acute sleep deprivation and allow to recover the rest of the nights. Do they perform better or worse in the long-term on cognitive tests? Do they have more or less inflammation? Do they need less recovery sleep over time?

I think that the answers are:

- Acute sleep deprivation combined with caffeine or some other stimulant that cancels out sleep pressure does not result in decreased cognitive ability at least until 30-40 hours of wakefulness (if this is true, then sleepiness , rather absence of sleep per se is responsible for decreased cognitive performance during acute sleep deprivation).

- Occasional acute sleep deprivation has no impact on long-term cognitive ability or health.

- Sleep does become more efficient over time and, in complete analogy to exercise, you withstand both acute sleep deprivation better and can function at baseline with a lower amount of sleep in the long-term.

(The only parallel to fasting I’m aware of anyone making is by Nassim Taleb… when he was quote-tweeting me.)

Appendix: anecdotes about acute sleep deprivation

Appendix: philipp streicher on homeostasis, its relationship to mania/depression, and on other points i make, our priors about sleep research should be weak.

In this section, I note that most sleep research is extremely unreliable and we shouldn’t conclude much on the basis of it.

Do you believe in power-posing? In ego depletion? In hungry judges and brain training?

If the answer is no, then your priors for our knowledge about sleep should be weak because “sleep science” is mostly just rebranded cognitive psychology, with the vast majority of it being small-n, not pre-registered, p-hacked experiments.

I have been able to find exactly one pre-registered experiment of the impact of prolonged sleep deprivation on cognition. It was published by economists from Harvard and MIT in 2021 and its pre-registered analysis found null or negative effects of sleep on all primary outcomes Bessone P, Rao G, Schilbach F, Schofield H, Toma M. The economic consequences of increasing sleep among the urban poor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2021 Aug;136(3):1887-941. (note that both the abstract and the main body of this paper report results without the multiple-hypothesis correction, in contradiction to the pre-registration plan of the study. The paper does not mention this change anywhere. See comments for the details. ).

So why has sleep research not been facing a severe replication crisis, similar to psychology?

First, compared to psychology, where you just have people fill out questionnaires, sleep research is slow, relatively expensive, and requires specialized equipment (e.g. EEG, actigraphs). So skeptical outsiders go for easier targets (like social psychology) while the insiders keep doing the same shoddy experiments because they need to keep their careers going somehow .

Second, imagine if sleep researchers had conclusively shown that sleep is not important for memory, health, etc. – would they get any funding? No. Their jobs are literally predicated on convincing the NIH and other grantmakers that sleep is important. As Patrick McKenzie notes , “If you want a problem solved make it someone’s project. If you want it managed make it someone’s job.”

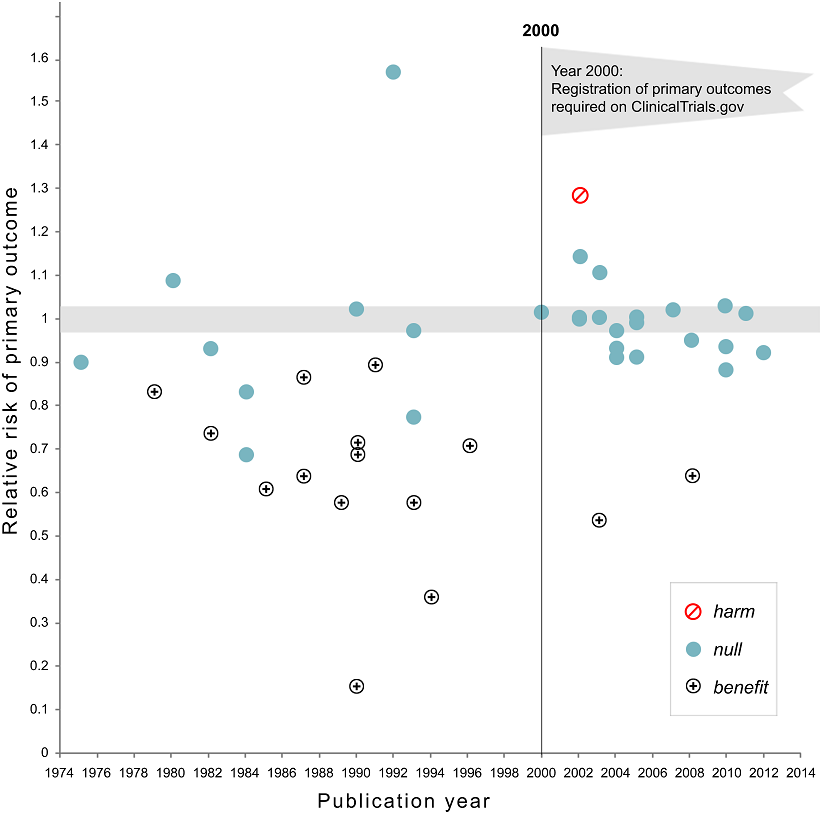

Figure 2. Relative risk of showing benefit or harm of treatment by year of publication for large NHLBI trials on pharmaceutical and dietary supplement interventions. Copied from Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382.

Figure 3. Eric Turner on Twitter: “Negative depression trials…Now you see ‘em, now you don’t. Published literature vs FDA, from [ Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Jan 17;358(3):252-60. ]"

Even in medicine, without pre-registered RCTs truth is extremely difficult to come by, with more than one half Kaiser J. More than half of high-impact cancer lab studies could not be replicated in controversial analysis. AAAS Articles DO Group. 2021; of high-impact cancer papers failing to be replicated, and with one half of RCTs without pre-registration of positive outcomes being spun Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382. by researchers as providing benefit when there’s none. And this is in medicine, which is infinitely more consequential and rigorous than psychology.

Also see: Appendix: I have no trust in sleep scientists .

Decreasing sleep by 1-2 hours a night in the long-term has no negative health effects

In this section, I outline several lines of evidence that bring me to the conclusion that decreasing sleep by 1-2 hours a night in the long-term has no negative health effects. To summarize:

- A sleep researcher who trains sailors to sleep efficiently in order to maximize their race performance believes that 4.5-5.5 hours of sleep is fine.

- 70% of 84 hunter-gatherers studied in 2013 slept less than 7 hours per day, with 46% sleeping less than 6 hours.

- A single-point mutation can decrease the amount of required sleep by 2 hours, with no negative side-effects.

- A brain surgery can decrease the amount of sleep required by 3 hours, with no negative-side effects.

- Sleep is not required for memory consolidation.

- Claudio Stampi is a Newton, Massachusetts based sleep researcher. But he is not your normal sleep researcher whose career is built on observational studies or p-hacked n=20 experiments that always show “significant” results. He is one of the only sleep researchers with skin in the game: the goal of his research is to maximize performance of sailors by tinkering with their sleep cycles, and he believes that 4.5-5.5 hours of sleep is fine, The article uses the phrase “get by” and does not state that there’s no decrease in performance. However, it does state that the decrease in performance at 3 hours of sleep with lots of naps is 12-25%, so increasing sleep by 50-83% from this, seems unlikely to result in any decrease in performance, compared to 8 hours of sleep (“he had them shift to their three-hour routines. After more than a month, the monophasic group showed a 30 percent loss in cognitive performance. The group that divided its sleep between nighttime and short naps showed a 25 percent drop. But the polyphasic group, which slept exclusively in short naps, showed only a 12 percent drop."). as long as it’s broken down into core sleep and a series of short (usually 20-minute) naps. Here’s Outside :

“Solo sailing is one of the best models of 24/7 activity, and brains and muscles are required,” Stampi said one day at his home, from which he runs the institute. “If you sleep too much, you don’t win. If you don’t sleep enough, you break.” …

“For those sailors who are seriously competing, Stampi is a necessity,” says Brad Van Liew, a 37-year-old Californian who began working with Stampi in 1998 and went on to become America’s most accomplished solo racer and the winner in his class of the 2002-2003 Around Alone, a 28,000-mile global solo race. “You have to sleep efficiently, or it’s like having a bad set of sails or a boat bottom that isn’t prepared properly.” …

both Golding and MacArthur sleep about the same amount while racing, between 4.5 and 5.5 hours on average in every 24—the minimum amount, Stampi believes, on which humans can get by.

In 2013, scientists tracked the sleep of 84 hunter-gatherers from 3 different tribes Yetish G, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Wood B, Pontzer H, Manger PR, Wilson C, McGregor R, Siegel JM. Natural sleep and its seasonal variations in three pre-industrial societies. Current Biology. 2015 Nov 2;25(21):2862-8. (each person’s sleep was measured for about a week but measurements for different groups were taken in different parts of the year). The average amount of sleep among these 84 people was 6.5 hours. Judging by CDC’s “7 hours or more” recommendation , Consensus Conference Panel:, Watson, N.F., Badr, M.S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D.L., Buxton, O.M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D.F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M.A. and Kushida, C., 2015. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(8), pp.931-952. 70% out of these 84 undersleep:

- 6 people slept between 4 and 5 hours

- 19 people slept between 5 and 6 hours

- 34 people slept between 6 and 7 hours

- 21 people slept between 7 and 8 hours

- 4 people slept between 8 and 9 hours

One group of hunter-gatherers (10 people from Tsimane tribe studied in November/December of 2013) slept just 5.6 hours on average.

The authors of this study also note that “None of these groups began sleep near sunset, onset occurring, on average, 3.3 hr after sunset” (they are probably getting too much artificial light… or something).

What I’m getting from all of this is: there’s nothing “natural” about sleeping 7-9 hours. If you think that the amount of sleep hunter-gatherers are getting is the amount of sleep humans have evolved to get, then you should not worry at all about getting 4, 5, or 6 hours of sleep a night.

The CDC and the professional sleep researchers pull the numbers out of their asses without any kind of rigorous scientific evidence for their “consensus recommendations”. There’s no causal evidence that sleeping 7-9 hours is healthier than sleeping 6 hours or less. Correlational evidence suggests Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21480. that people who sleep 4 hours have the same if not lower mortality as those who sleep 8 hours and that people who sleep 6-7 hours have the lowest mortality.

Also see: Appendix: Jerome Siegel and Robert Vertes vs the sleep establishment

It appears that there is a distinct single-point mutation that allows some people to sleep several hours less than typical on average. A Rare Mutation of β1-Adrenergic Receptor Affects Sleep/Wake Behaviors : Shi G, Xing L, Wu D, Bhattacharyya BJ, Jones CR, McMahon T, Chong SC, Chen JA, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Krystal A. A rare mutation of β1-adrenergic receptor affects sleep/wake behaviors. Neuron. 2019 Sep 25;103(6):1044-55.