- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How E-Commerce Fits into Retail’s Post-Pandemic Future

- Kathy Gramling,

- Jeff Orschell,

- Joshua Chernoff

New data from Ernst & Young suggests it will be an important part of the consumer experience — but not everything.

The pandemic has changed consumer behavior in big and small ways — and retailers are responding in kind. Since the early days of the pandemic Ernst & Young has been tracking these shifting trends using the EY Future Consumer Index and EY embryonic platform, which show a significant and widespread industry shift toward e-commerce. In this article, the authors suggest that while e-commerce will continue to be an essential element of retail strategy, the future success of retailers will ultimately depend on creating a cohesive customer experience, both online and in stores.

If we have learned one thing from the past year, it’s that things can change in an instant — changes we thought we had years to prepare for, behaviors we assumed we’d stick to forever, expectations we have of ourselves and our organizations. This is true of the way we live, the way we work, and the way we shop and buy as consumers.

- KG Kathy Gramling is EY Americas Consumer Industry Markets Leader

- JO Jeff Orschell is EY Americas Consumer Retail Leader

- JC Joshua Chernoff is EY-Parthenon Americas Managing Director

Partner Center

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Research on e-commerce data standard system in the era of digital economy from the perspective of organizational psychology.

- Henan University School of Law/Intellectual Property School, Institute of Civil and Commercial Law of Henan University, Kaifeng, China

With the rapid development of technology and the economy, the expansion of the network has had a huge impact on the rapid expansion of the industrial agglomeration e-commerce industry, as well as ensuring the shopping experience of consumers. The rapid expansion of industrial cluster e-commerce has avoided precisely the limitations of logistical bottlenecks. Current networks and modern information technologies can provide good support and maintain a huge growth potential. In addition, digital technologies such as multimedia are becoming increasingly important in industry cluster marketing, and the concept of industry cluster e-commerce models is gaining more and more attention from companies. However, virtual e-commerce systems under industrial clusters have not been well researched in the existing studies. In this paper, through extensive research, literature reading and website browsing statistics, the virtual e-commerce models of different industrial agglomerations are studied. Firstly, the concept of big data and the processing of big data are given. Secondly, the concept of industrial agglomeration and the relationship between industrial agglomeration and e-commerce are analyzed. The basic number of domestic Internet users in the last 10 years is also counted, proving that the expansion of the Internet has led to a substantial growth of Internet users in the country and that e-commerce plays a significant role in the future of business activities. Finally the study concludes that different e-commerce models have different performance and roles in industrial agglomeration e-commerce and cannot be generalized. Instead, it is not good and can only develop different industrial agglomeration e-commerce models according to different environments.

Introduction

In the long history of mankind, when people explore and discover the law of unknowns, they rely mainly on reasoning methods such as experience, theory, and assumptions, which are largely influenced by personal prejudice. Later, people invented mathematical tools such as statistics, sampling, and probability. Through careful design and extraction methods, a small number of data samples were obtained to infer the whole picture of things. Therefore, there are often deviations and distortions in understanding things. According to Victor Meyer, thanks to advances in technology, people can access all the data of a research object and understand things from different angles. Analyze the different dimensions of all data from an incomprehensible perspective. With the rapid expansion of electronic signal technology, e-commerce ( Anam et al., 2017 ; Irene, 2018 ) has changed an inevitable outcome of the expansion of the times and is also a form of transaction that adapts to market demand. The expansion of e-commerce is very gratifying. After more than 10 years of expansion, B2C ( Gui et al., 2019 ) and C2C ( Navarro-Méndez et al., 2017 ) have become the main mode of e-commerce in China. The model has the vitality of information transparency, flexible trading, high efficiency and price advantage. With the rapid propagate of the Net, by the end of 2018, the number of Internet users in China reached 1.08 billion. A great deal of Internet users has established a good customer base for the expansion of e-commerce. In addition, the continuous improvement of relevant laws and regulations and the maturity of information technology have laid the foundation for the expansion of e-commerce. By combining big data with e-commerce, e-commerce based on big data will become the main research direction of the future society ( Nik et al., 2017 ).

Mega data (big data) ( Wang et al., 2017 ; Zhou et al., 2017 ) is what we often call big data, also known as massive data. Giant data is actually a data repository. In this era, it can be used as an asset. After professional analysis, the efficiency is higher, the amount of data is larger, the data is diverse, and the sources are different, most of which are instantaneous. The communication information generated during the sales process is also generated instantaneously. For example, customer basic data, website clicks, network data, etc., are all counted in big data, some are part of customer information, and some are not counted. In the 1980s, some scholars predicted big data and believed that big data will surely ignite the new wave of the third technological revolution. Since 2009, “Big Data” has made great progress with the rapid expansion of e-commerce and cloud computing ( Liu et al., 2018 ) and is gradually becoming well known to the public. As can be seen from the latest data, the growth of data on the Internet and mobile Internet has gradually approached Moore’s Law, and global data and information have been created “over doubling every 18 months” over the years. The application of big data in industrial agglomeration ( Xuan, 2017 ; Nádudvari et al., 2018 ) e-commerce is also getting more and more wide-ranging.

Industrial clusters ( Cao et al., 2017 ; Wang and Yu, 2017 ) have a long history as well-functioning organizations. At the end of the 19th century, Marshall creatively defined the concept of “industry zone,” that is, industrial clusters. He defines “industrial zone” as the agglomeration of certain industrial zones, which is determined by two factors: history and natural resources. There are many companies of different sizes in the area. There is a close relationship between cooperation and competition, which gradually affects the integration of industrial clusters and society. According to Marshall, the reason for the emergence of “industry zones” in the region is a combination of inside and outside factors. Later, Weber believed that the phenomenon of industrial clusters was the result of regional and geographic influences. Companies with regional and geographic advantages have established close partnerships through partnerships with other related companies. Establish complex and close internal network relationships, achieve the aggregation of enterprises in a specific region, and then develop into industrial clusters. In recent decades, academia and industry have been highly involved in the expansion of synergies between industrial clusters and supply chains. They actively used industrial clusters and supply chains in corporate management ( Heiner and Marc, 2018 ) and achieved remarkable results. Clusters and supply chains can provide a competitive advantage for businesses. However, with the rapid expansion of e-commerce, industrial clusters are faced with the dilemma of optimizing transformation and upgrading. The traditional approach to supply chain management is far from meeting the needs of users. Therefore, it is a major problem to study how e-commerce uses the first-mover advantage to promote synergy between industrial clusters and supply chains.

For the core enterprises in the industrial agglomeration, because of their own advantages in terms of capital and technology, as well as a number of strong manufacturers and suppliers, so that the online market established by the enterprise has a large number of members and good prospects for development, and attracts some new members to join, once the establishment of close cooperation in this online market, its members want to move to other online market will be very expensive, so that the core enterprises in the online market to consolidate their existing position ( Yang et al., 2022 ; Han et al., 2021 ; Setiawan et al., 2022 ; Suska, 2022 ; Yu et al., 2022 ). Therefore, e-commerce has developed into a new opportunity to enhance the synergy of China’s supply chain and enhance its competitive advantage. In the end, this paper starts from the business reality of big data-based industry agglomeration e-commerce, fully considers the dependence of industrial agglomeration area on e-commerce in the era of big data, and studies the relationship between the concept of industrial agglomeration and the relationship between e-commerce and industrial agglomeration. Therefore, with the support of big data, this paper analyses the number of netizens, the level of economic expansion, etc., and compares the impact of e-commerce yield and industrial agglomeration e-commerce investment and big data and e-commerce on industrial agglomeration. The merits and demerits of e-commerce in the type of industrial agglomeration, and the expectation is to provide a summary and reference for the industry to gather e-commerce enterprises to obtain competitive advantages in the market competition.

Big Data and E-Commerce Related Definitions

Big data overview.

With the popularity of the Internet and the rapid expansion of information technology, the signal age is making a subtle transition to the big data era. The network has turned into an integral part of people’s production and life. While enjoying the convenience brought by the information network, people also continuously feedback and input information to the network. Some information involves individual privacy, and network information security has become one of the hot topics of research. At present, the social network information security problem is becoming more and more obvious, the conventional information security software has been unable to deal with the endless information security problem, the network society urgently needs a new information technology to protect the increasingly huge information assets, and the big data technology has stronger insight, more scientific decision-making power and more accurate process optimization ability compared with the conventional software. Must be able to play a positive effect.

Professor Victor is known as the “Big Data Prophet.” Big data also called huge amount of data, refers to the amount of data involved is so large that it cannot be captured, managed, processed and collated in a reasonable time through the human brain or even mainstream software tools to help enterprises to make more positive decisions. By analyzing big data, we can draw conclusions that cannot be obtained in the case of small data. The big data we usually talk about is more about getting valuable information in a short time by quickly analyzing a large amount of data.

Big Data Analysis Process and Features

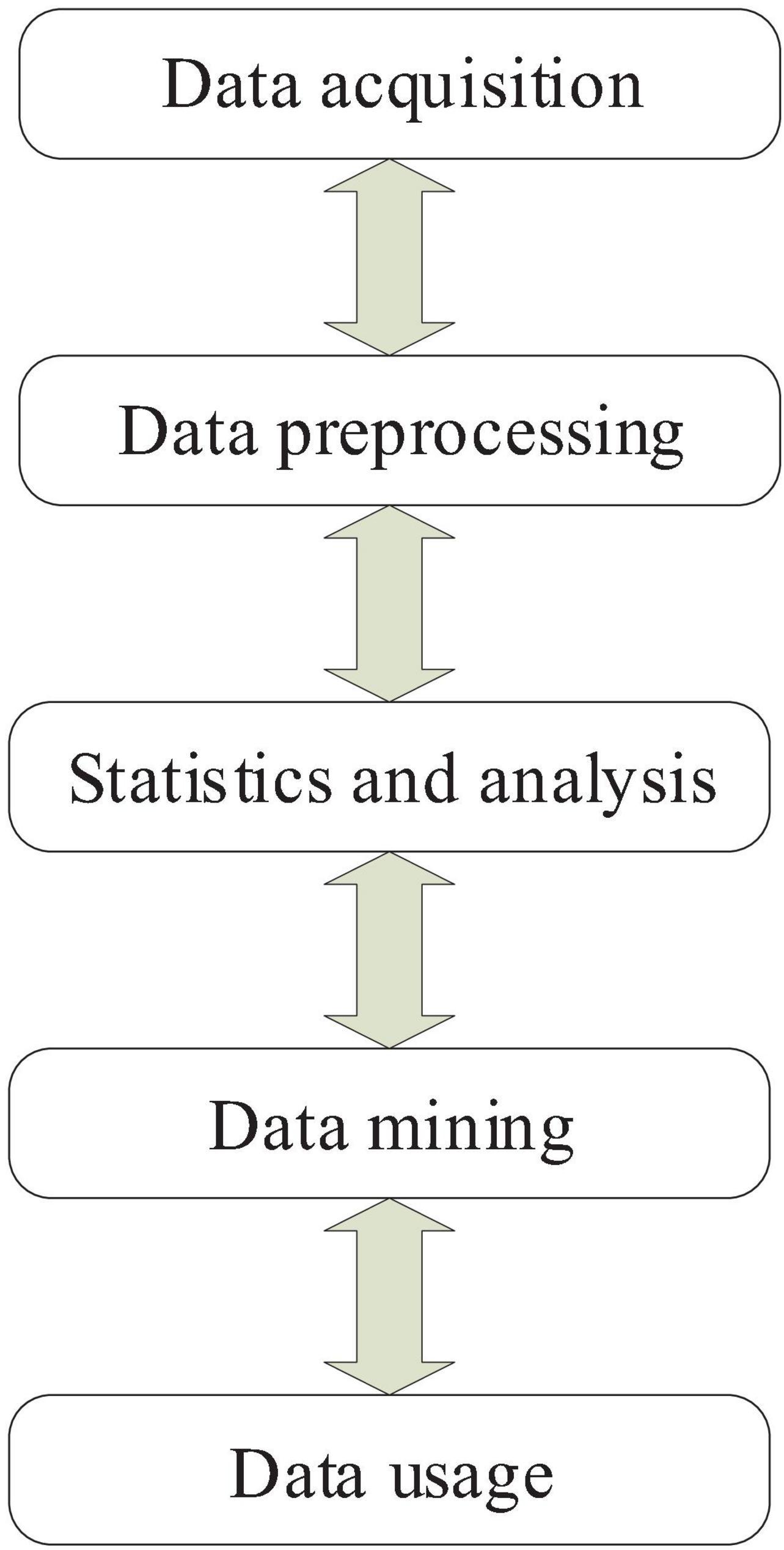

In general, there are many methods for analyzing big data, and in theory it is still in the exploration stage, but no matter what kind of big data analysis method follows the basic process, the flow chart is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Big data processing flow.

The first process of big data analysis is acquisition. Big data sampling ( Bivand and Krivoruchko, 2018 ; Cohen et al., 2018 ) means collect information collection platforms to collect users or other data. In the process of big data collection, the main problem is that the amount of data is huge, the amount of collection is large, and the data collection point is large. A large amount of data needs to be collected at the same time. Therefore, in the process of collecting big data, it is necessary to establish a larger database and how to further design the reasonable use and distribution of the database.

The second step is import and beneficiate. This mainly means that invalid information, redundant information and low-value information are excluded after the first information collection is completed, so it is necessary to execute the data before processing. Effective screening and brief analysis, and then import the resulting preliminary filtering information into another large database, this step is mainly to pre-process the big data.

The third step in big data processing is to perform statistics and analysis. This process is a process of further refinement of big data, analyzing and screening valid data, and performing statistical processing to obtain effective information.

The fourth step in big data is to deal with the mining ( Rezaei-Hachesu et al., 2017 ; Fan et al., 2018 ; Svefors et al., 2019 ) process. Unlike the above process, there is no clear path or statistical analysis method for big data information mining. It is mainly used for databases that collect large amounts of data and use various algorithms for calculations, so it is complex data. Try to get predictions or get other valid conclusions. The statistical analysis and mining process of big data is considered to be a key process for transforming data from data into value space and value sources in the process of big data information processing.

The final step is using information obtained from big data. In particular, it can be used for business decision behavior predictions, while sales companies can provide accuracy. Marketing, achieving service conversion, etc. The application prospect of big data is very broad, and it has a good application prospect in transportation, sales management, economic research and forecasting.

At present, there is no authoritative unified standard. At present, the “4V” function of big data has been widely recognized.

First, the data size is huge. In 2012, the world produced about 2.7 billion GB of data per day, the amount of data per day equals the sum of all stored data in the world before 2000. Baidu must process more than 70,000 GB of search data per minute, and Alipay generates an average of 73,000 transactions per minute. Traffic flow monitoring systems and video capture systems can generate large amounts of video data at any time. Temperature sensors in greenhouses and various detectors in the factory are also big data manufacturers. It can be said that the amount of data we generate per minute is unimaginable. Now, the scale of data that big data needs to process continues to grow, reaching orders of magnitude unimaginable in small data.

Second, there is a wide variety of data (Variety). In big data, in addition to the ever-increasing data size, the types of data that people need to deal with are beginning to emerge. The various data types are very numerous and very strange, and only a few can be handled using traditional techniques. Some are unstructured data that traditional technologies cannot handle, and this trend will be long-term, with unstructured data accounting for 90% of all data over the next decade. For example, Tudou’s video library, photos on social networking sites, records, etc., even include RFID status, mobile operator call history, video surveillance video, Weibo and status posted on WeChat. The size, format, and type of data from various sources may vary. Existing data processing techniques are useless and can cause significant difficulties when performing large amounts of processing.

Third, value is difficult to mine. The first two features show that the amount of data and data types in big data are amazing. Faced with a large amount of data, in order to mine hidden “treasures,” the analysis and processing of powerful cloud computing systems is only one aspect, not even the main one. How to analyze big data from the perspective of innovation according to needs, what to use big data ideas to examine big data to explore unimaginable economic and social values. In other words, only the combination of technology and innovation can unlock the value of big data. Otherwise, no amount of data will be useful.

Fourth, the processing speed is high (Velocity). This is the most significant feature of the big data era, unlike the era of small data and the era of probability and statistics. In traditional economic censuses, censuses and other areas, data can be tolerated for days or even a year, as the data obtained at this time still makes sense. Moreover, due to technical limitations, the collected data has been lagging behind, and the structure of statistical analysis is lagging behind, but it must be accepted. Data generation and collection is very fast, and the amount of data is growing all the time. With advanced technology, people can collect data in real time. But in most cases, if you don’t process the data in time, the advanced collection and sorting methods will be meaningless and you won’t need big data. For example, IBM proposed the concept of “big data-level stream computing,” which is designed for real-time analysis of data and results to increase practical value. Therefore, timely and fast processing of data and results is the most important feature of big data.

This is the most significant feature of the big data, unlike the era of small data and the era of probability and statistics. Due to technical limitations, the collected data is backward, and the structure of statistical analysis is also backward, but it must be accepted. Data generation and collection is very fast, and the amount of data has been growing. With advanced technology, people can collect data in real time. But in most cases, if you don’t process the data in time, the advanced collection and sorting methods will be meaningless. For example, IBM proposed the concept of “big data-level stream computing,” which aims to analyze data and results in real time to increase practical value. Therefore, timely and fast processing of data and results is the most significant feature of big data.

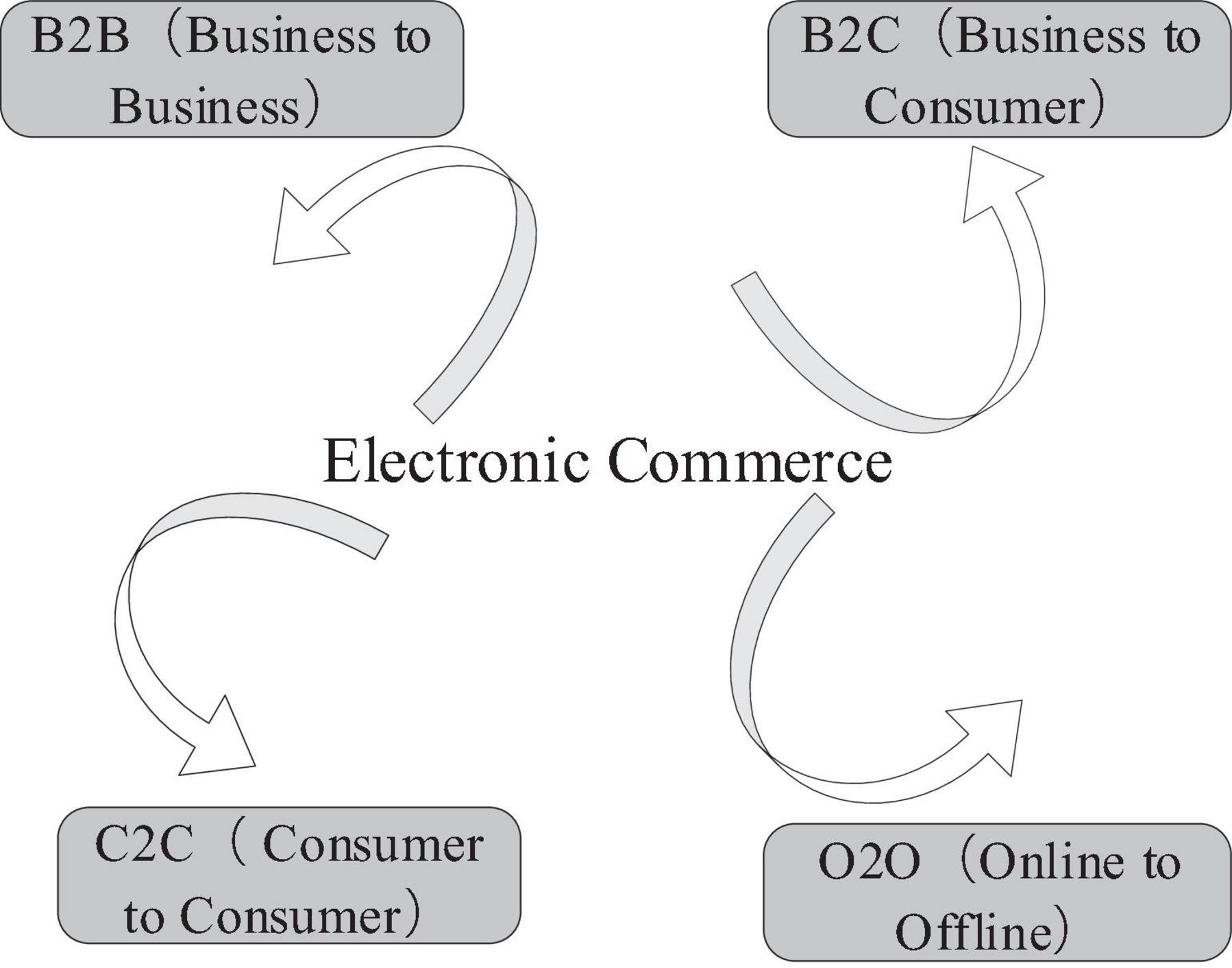

E-Commerce Concept

E-commerce generally refers to Internet technology, based on browser/server applications, through the Internet platform, buyers and sellers through various trade activities to achieve consumer online shopping, online payment and new business activities of various business activities and other models. The expansion history of e-commerce has a close relationship with the progress of computer network technology. E-commerce includes many models, such as B2B ( Ning et al., 2018 ) (Business to Business), B2C (Business to Consumer), C2C (Consumer to Consumer), and O2O (Online to Offline). The main centralized e-commerce model is shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2. Main e-commerce model.

This article focuses on C2C ( Sukrat and Papasratorn, 2018 ) e-commerce. C2C e-commerce refers to a network service provider that uses computer and network technology to provide e-commerce platforms and transaction processes to users in a paid or non-paid manner. Allow both parties to conduct online transactions on their platform. The two sides of the transaction are mainly individual users, and the trading method is based on bidding and bargaining. Like B2B and B2C, C2C is also a basic e-commerce transaction model. In real life, it is similar to the “small commodity wholesale market.” There are many self-employed people in a website, and the website’s role in e-commerce is equivalent to the “market manager” in actual market transactions. At the same time, in order to promote smooth transactions between buyers and sellers, C2C e-commerce provides a series of support services for both parties. For example, in cooperation with market information collection, credit evaluation systems and various payment methods have been established. Due to the rapid expansion of e-commerce, industrial agglomeration has become more impressive. The most prominent performance of industrial agglomeration is the industrial concentration of “Internet + traditional industries” such as “Taobao Village.” C2C is the mainstream of this e-commerce business model. C2C e-commerce “Taobao Village” is a product based on urban and rural expansion in China. It has Chinese characteristics and is a “Chinese product.” This is both a theoretical issue and a very real social phenomenon. The Chinese government has put forward the “Internet+” proposal. With the expansion of China’s strategic emerging industries, “Internet + traditional industries” will become a shortcut for China’s backward regions to seek expansion, which can shorten the time required for expansion, making C2C e-commerce a “hometown of Taobao.” Therefore, in order for the industry to complete transactions, an e-commerce platform and online and offline resources and services are needed. It can be said that the C2C model is an e-commerce model that is very suitable for industrial agglomeration. The biggest advantage of the C2C e-commerce model is that it can produce and deliver enterprise products or services on demand, so that enterprises can quickly develop into large enterprises, and the C2C e-commerce model provides consumers with cheap and affordable purchases. Product and service platforms enable businesses and consumers to achieve a win-win situation.

In traditional market transactions, the delivery of goods from producers to stores requires warehouse storage, vehicle transportation, etc., which increases inventory costs and transportation costs, resulting in increased transaction costs. Unlike real-world trading, since e-commerce joins the virtual network, both buyers and sellers trade through the e-commerce platform, so there is no need for face-to-face communication. This form saves the seller’s transaction costs, including physical store and merchandise inventory and transportation costs. At the same time, buyers can also shop without going out, and can quickly compare products of different merchants through the network, which allows buyers to get more information, more efficient and lower cost. C2C e-commerce uses Internet communication channels based on open standards. Compared with traditional communication methods (such as mail, fax, newspaper, radio, and television), communication costs are greatly reduced.

Industry Agglomeration Virtual E-Commerce

Industrial cluster concept.

Industrial clusters attract the attention of many scholars by attracting resources, economies of scale, knowledge learning and innovation, saving transaction costs, and improving cooperation efficiency. Many mathematicians have studied the composition, characteristic mechanism, and identification criteria of industrial clusters through theoretical derivation, model construction, structural equations, and case studies, and elaborated and summarized the concept of industrial clusters. The definition of industrial agglomeration is that in a relatively limited space of a certain area, geographically adjacent or different geographical entities closely related to relevant institutions and government agencies spontaneously gather together, called industrial clusters. The division of labor between entities and continuous cooperation and innovation have formed a complex cluster network, providing environmental and technical support. The difference is that industrial clusters can adapt to economic expansion, and further transformation and upgrading will form a new industrial cluster model. At the same time, mutual trust, mutual decision-making, and close cooperation have created the greatest value and benefits for the industry. Finally, for the measurement and acquisition of industrial clusters, combined with the practical significance of empirical research, the measurement of industrial clusters is unified by the concentration of specific industries, that is, specific industries. A measure of the spontaneous aggregation of related entities or institutions in a particular industry in the region. If the total quantity or total capacity reaches the previous unified level, it indicates that there is an industrial cluster in the area.

The Relationship Between E-Commerce and Industrial Clusters

With the rise and prosperity of e-commerce, the new business organization system breaks the regional and spatial barriers, promotes the use of e-commerce and partners, establishes synergy and sharing mechanisms, and continuously meets the needs of users. Proactively improve user experience and satisfaction. In addition, e-commerce platforms and logistics platforms are increasingly used in new business models. Although these platforms are very different, the role of the company cannot be underestimated. The platform typically includes several key functional modules such as trading markets, logistics platforms, enterprise services, cluster information, and corporate communities. Cluster companies can conduct informal technology and information exchange on the platform. Through the construction of an e-commerce platform, industrial cluster enterprises can share market conditions, the latest industry technologies, and related industry information in real-time and quickly, creating greater economic benefits for enterprises. This close partnership helps industry clusters increase trust and mutual benefit. In short, e-commerce applications can help industrial clusters effectively integrate regional resources, meet market demands promptly, expand clusters, and increase the level of collaboration and competitiveness of enterprises within the cluster. Currently, the introduction of e-commerce applications has further promoted the expansion of supply chain coordination. As an effective spatial organization model, industrial clusters play an increasingly important role in improving the overall economic level of the region and optimizing the allocation of industrial resources. The rapid expansion of industrial clusters provides natural conditions for the expansion of enterprises, between enterprises and between supply chain members. Similar companies continue to gather, and upstream and downstream companies in the supply chain are also gathered to promote the use of e-commerce. A deeper impact on the synergy of the supply chain. Therefore, for the sake of strengthening the application of e-commerce. Based on continuous research by many scholars, it is further proved that the rapid expansion of industrial clusters promotes the coordinated management of supply chains.

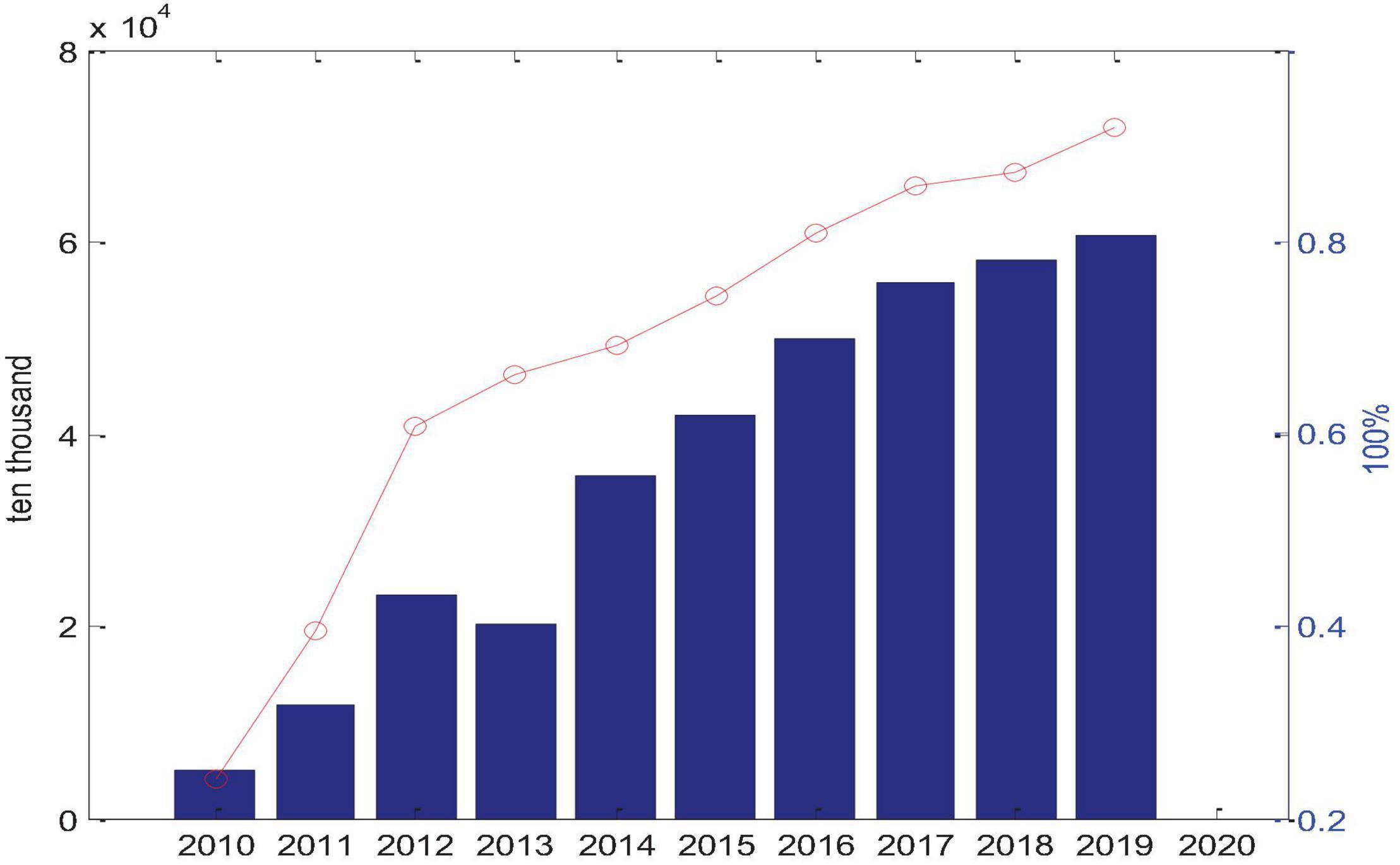

Since 1980, the economy and the world have continued to develop. The Internet and information technology are constantly innovating. In addition to constantly affecting people’s daily lives in various aspects, it also leads the transformation of modern new production organizations. Figure 3 shows the statistics of Chinese netizens in the past decade. As can be seen from the above data, since the popularity of smartphones in 2013, mobile network users have occupied almost the entire network in the past 7 years. In the future expansion, mobile network users will develop more rapidly, making the popularity of mobile Internet and smart phones break the expansion of PC networks. At anytime, anywhere, and on the Internet, the online concept of the PC era has been broken, and immediacy has become a unique personality in the age of network information. A large amount of information, rapid response and scale effect are the main features of the e-commerce. The rapid spread of mobile phone business applications shows that the use of mobile phone networks by netizens has changed from basic communication entertainment to life entertainment. Since 2013, thanks to the expansion of domestic smart phone technology, the Internet access method based on mobile Internet has opened a new period of e-commerce and access to the Internet anytime and anywhere, so that more buyers and sellers can conduct transactions through the network, and Each transaction is based on online trading of various trading tools, and the trading platform and trading model have been rapidly developed. E-commerce has become a grassland, which has an impact on the production value chain, profit model and marketing methods of traditional industries. It can be seen that the growth of the network has boosted the expansion of e-commerce. The growth of e-commerce has promoted industrial agglomeration, and industrial agglomeration has formed economic globalization.

Figure 3. Number and proportion of mobile phone users.

Industrial Agglomeration Virtual E-Commerce Analysis

China’s e-commerce transaction scale.

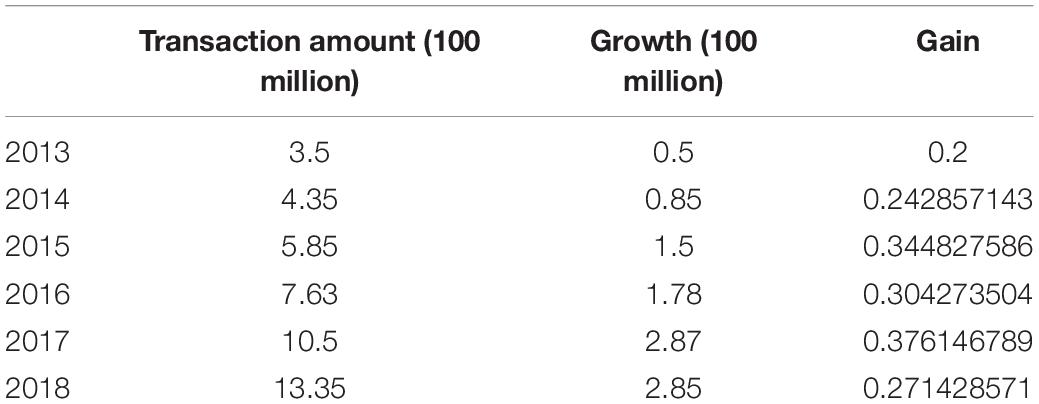

In the e-commerce environment, China’s e-commerce has undergone earth-shaking changes, especially in the past 30 years, the rapid growth of signal technology and technological innovation have made all aspects related to e-commerce stand out. The cost of online transactions has been greatly reduced, network communication is extremely convenient, and e-commerce is everywhere. On the basis of China’s national conditions, the application and expansion of e-commerce in China is different from that of other countries, but its expansion is in full swing. The expansion of China’s e-commerce is a signification part of accelerating the informationization of the national economy. At the same time, the application of e-commerce has also changed the production organization of enterprises to a large extent. Enterprises and users can interact directly with e-commerce related R&D, technology expansion, production, procurement, marketing and product operations. Other services and links can fully introduce user engagement and control market demand trends in real time. Table 1 shows the scope of China’s e-commerce transactions collected from the China E-Commerce Research Center.

Table 1. Scope of China’s e-commerce transactions.

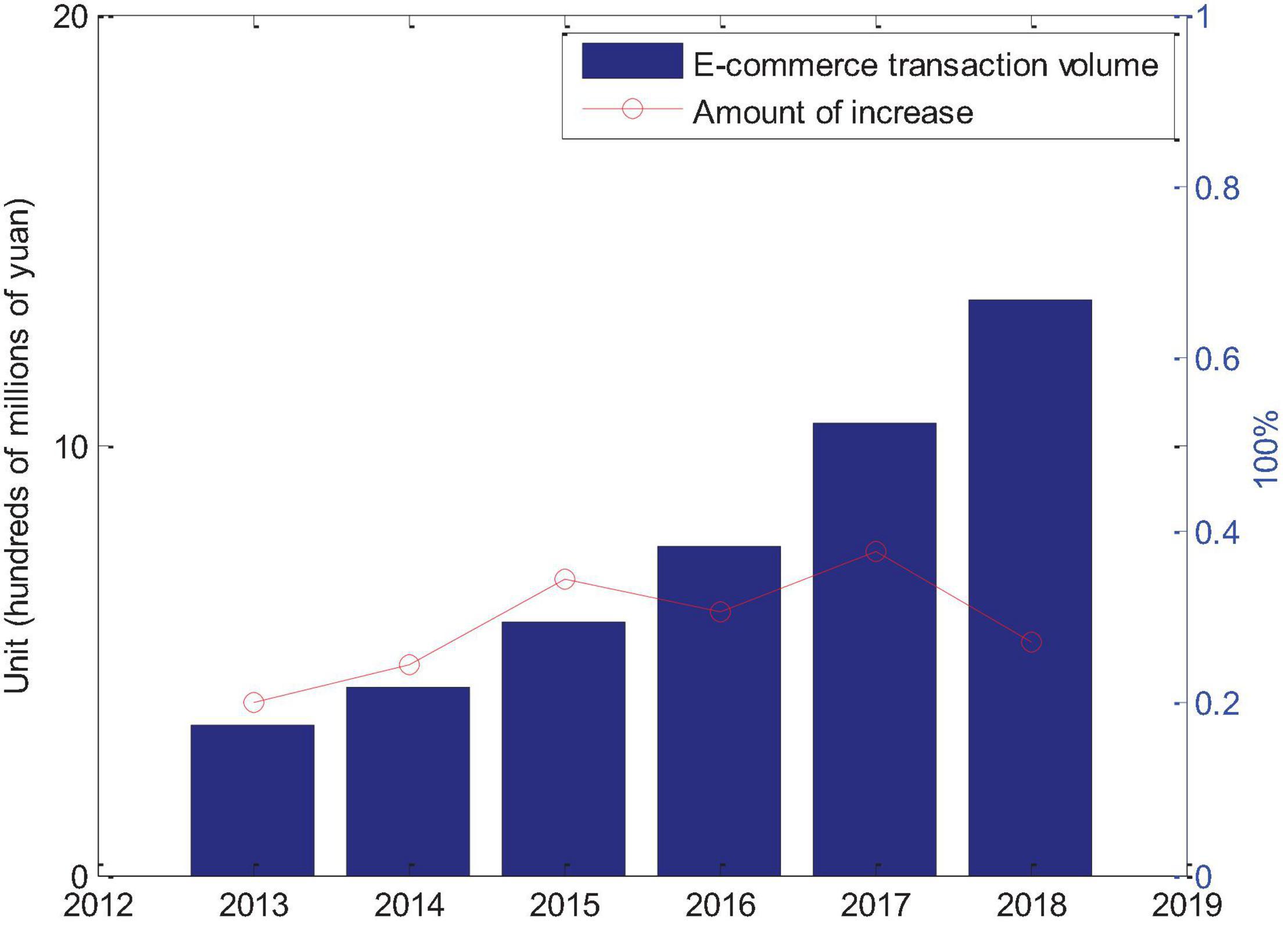

Figure 4 shows the scope of China’s e-commerce market transactions from 2013 to 2017. It can be seen that as of 2018, China’s e-commerce still maintains a rapid growth trend. With the continuous encouragement and support of the government, all relevant systems are in a stage of continuous improvement. Under the impetus of e-commerce, enterprises and users, constantly proposing new consumer demand will help the rapid expansion of the upstream and downstream industry chains of traditional enterprises and provide new impetus for China’s economic expansion.

Figure 4. Trends in the scale of China’s e-commerce transactions.

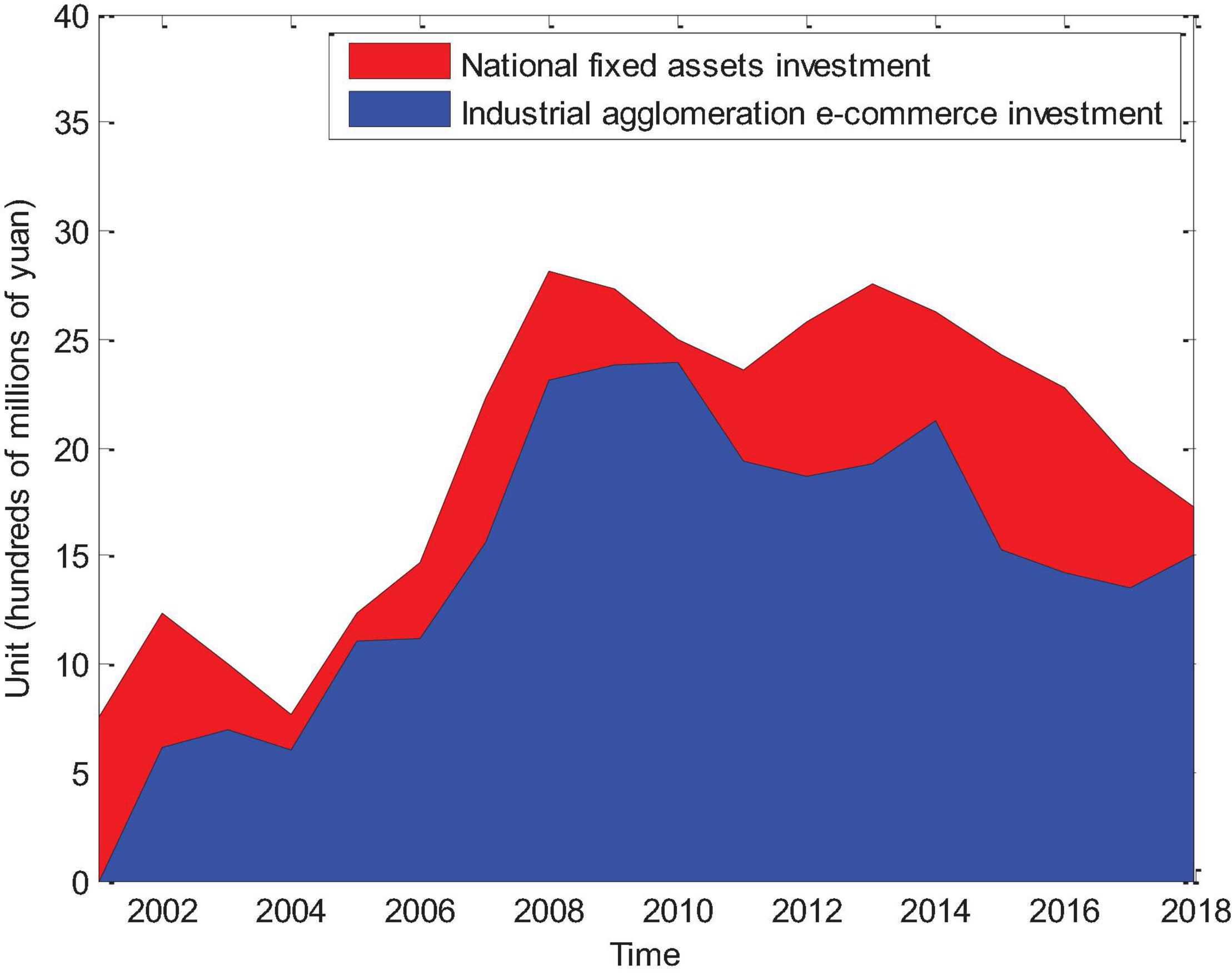

It can be seen from Figure 5 that from 2001 to 2008, industrial agglomeration e-commerce investment and fixed asset investment are all levels of sustained growth, which proves that e-commerce expansion is relatively rapid during this period. In the future, industrial agglomeration investment profits can be Add a lot. From 2008 to 2015, the level of China’s economy was in a period of slow growth, and the investment level during this period was almost stable. After 2015, due to the saturation of the economy, the investment level remained at a certain level and the economic expansion region was stable.

Figure 5. Changes in national fixed asset investment and industrial agglomeration e-commerce investment from 2001 to 2018.

The Impact of the Level of Big Data Expansion on E-Commerce in Industrial Agglomeration

With the increasing popularity and expansion of the Internet, e-commerce has become an important aspect of Internet applications. In addition to the old e-commerce companies, traditional stores also opened their own online shopping malls. Consumers are also increasingly enjoying this convenient and fast way to shop. According to CNNIC’s statistical report, as of last year, the number of Internet users in China has reached 1.008 billion, and the proportion of online shopping among netizens has increased to 55.7%. In addition to online shopping, many service industries or national administrative departments have also increased the construction of online platforms, such as online car rental, travel route booking, room service, online transaction management fees, etc., further expanding the application field. E-commerce has created more business growth points. The expansion of business types and the explosive growth of business volume have brought a lot of data information. The old e-commerce companies Amazon, Alibaba and so on are all beneficiaries of big data. It can be said that without the support of big data technology, there is no e-commerce enterprise today.

The expansion of big data makes practitioners more competitive in e-commerce. From the perspective of the number of competitors, China’s e-commerce industry is currently in a highly concentrated stage. Although a large number of e-commerce companies have emerged, in the field of online retail, Taobao, Tmall, Jingdong, No. 1 store, Amazon and many others occupy most of the market. The emergence of big data has further increased barriers to entry, so the number of competitors in the online retail industry will change less. From the perspective of foreign competitors, it will undoubtedly increase the intensity of market competition. For example, the way Amazon enters the Chinese market is to acquire Joyo. From the perspective of switching costs, the e-commerce industry has typical low-cost conversion characteristics for consumers. On-site e-commerce companies often use large subsidies, promotions and free shipping to retain old users and win new users, which makes the market competitive. The pressure is constantly increasing. Pursuit of economies of scale. Most industries have significant economies of scale. E-commerce operators are pursuing economies of scale and blindly expanding, resulting in overcapacity, which ultimately led to fierce competition in the industry.

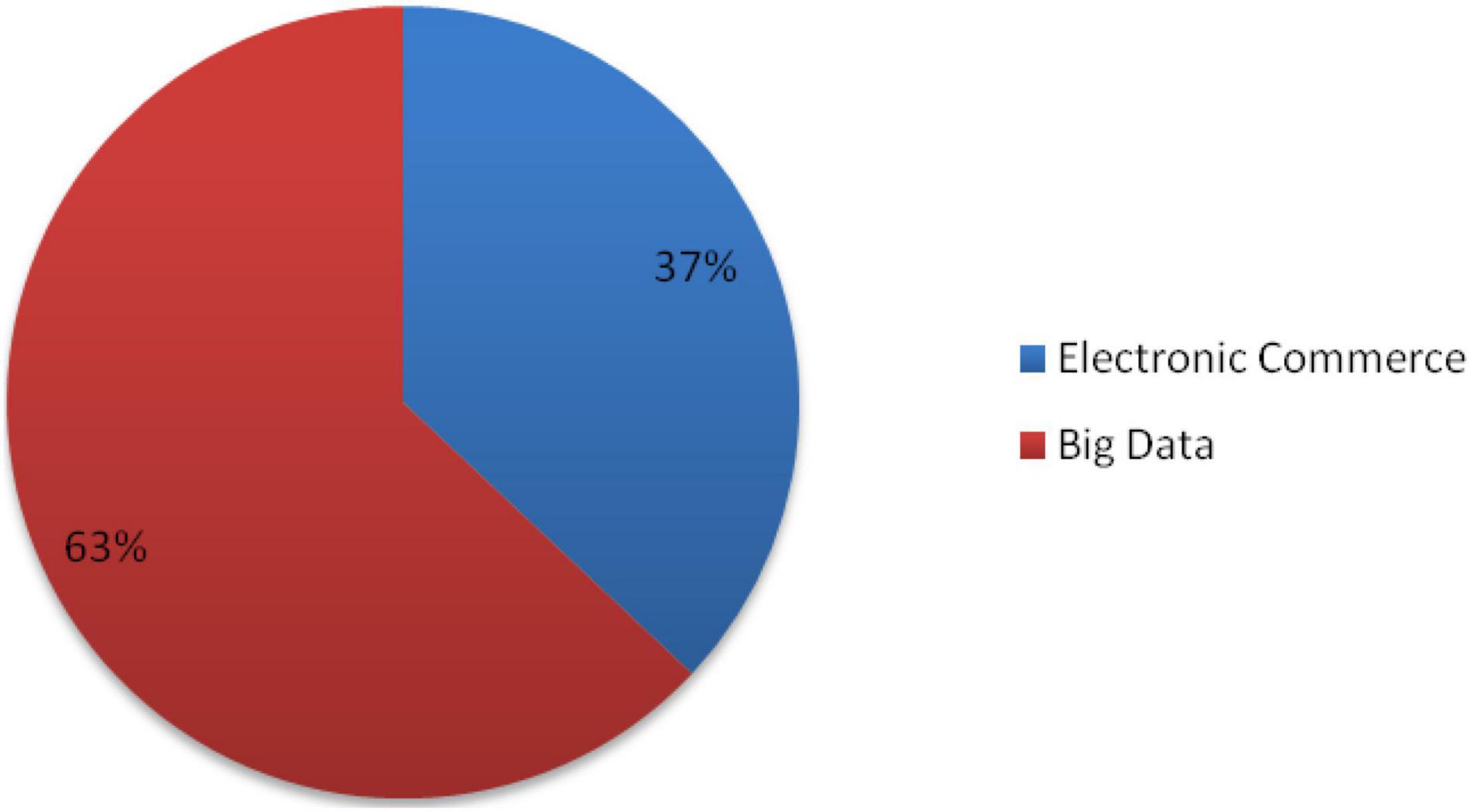

Figure 6 shows the expansion index for big data and e-commerce. As can be seen from the above data, in the future expansion process, big data is indispensable as a tool to support e-commerce and industrial agglomeration, and e-commerce is expanding very rapidly. The expansion of industrial agglomeration plays a very significant role. In the future, the expansion of e-commerce in all walks of life cannot be ignored. The future world is the electronic world and the data world. As an effective management mode of enterprise manufacturing and industrial organization, industrial cluster and supply chain management have become the inevitable requirements and strategic measures for enterprises to survive and develop in various fields. The coupled industrial cluster supply chain provides a new expansion trend for resource coordination and industrial upgrading, enabling cluster enterprises to improve traditional production methods, respond quickly to user needs, and consciously work closely together to grasp rapid changes more quickly and accurately. In order to deal with this problem, it is necessary to improve the operational efficiency of the enterprise through the information charge platform and modern management tools. Through the information platform, this work-use management becomes more complex, professional and standardized, thus freeing up enough energy to respond to industry changes.

Figure 6. Impact of big data and e-commerce on industrial agglomeration expansion.

In industrial agglomeration, the pioneering role of core enterprises should not be overlooked. If the pioneering enterprises can be cultivated effectively, through it to other enterprises and supporting enterprises to enter the industry to play a direct demonstration and produce cohesion, so that the formation of industrial agglomeration has a driving effect. At present, some of the core enterprises in the industry have already established a relatively complete e-commerce system. If we can combine the needs of SMEs in the industry, open up some of the functions of the system to a certain extent, and realize the sharing of information and knowledge with enterprises in the industry, this is very beneficial to enhancing the enthusiasm of SMEs to participate in industrial division of labor and cooperation, and at the same time lowering the this is very beneficial to increase the enthusiasm of SMEs to participate in industrial division of labor and cooperation, and at the same time reduces the threshold for SMEs to participate in e-commerce. A well-developed social network based on marketization or externalization is the basis for the formation and development of industrial clusters. To this end, the construction of information service organizations and networks within industrial clusters should be supported and encouraged to provide a variety of information services to enterprises, reducing the wasted costs and incomplete information caused by enterprises collecting information alone. At the same time, the construction of public institutions and means of communication that facilitate interaction between producers and the market should be strengthened, cooperation between enterprises and universities or research institutes should be encouraged, and the establishment of local public institutions that provide technical training, technical support and market information to producers should be supported. In addition, the construction of information advisory services should be accelerated and a multi-level public information platform should be established. In this regard, government departments or professional information service providers can intervene to provide a full range of information service approaches and dovetail with government public data platforms to achieve low-cost information services and knowledge provision within the industry.

Analysis of Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Business Models in Industrial Agglomeration

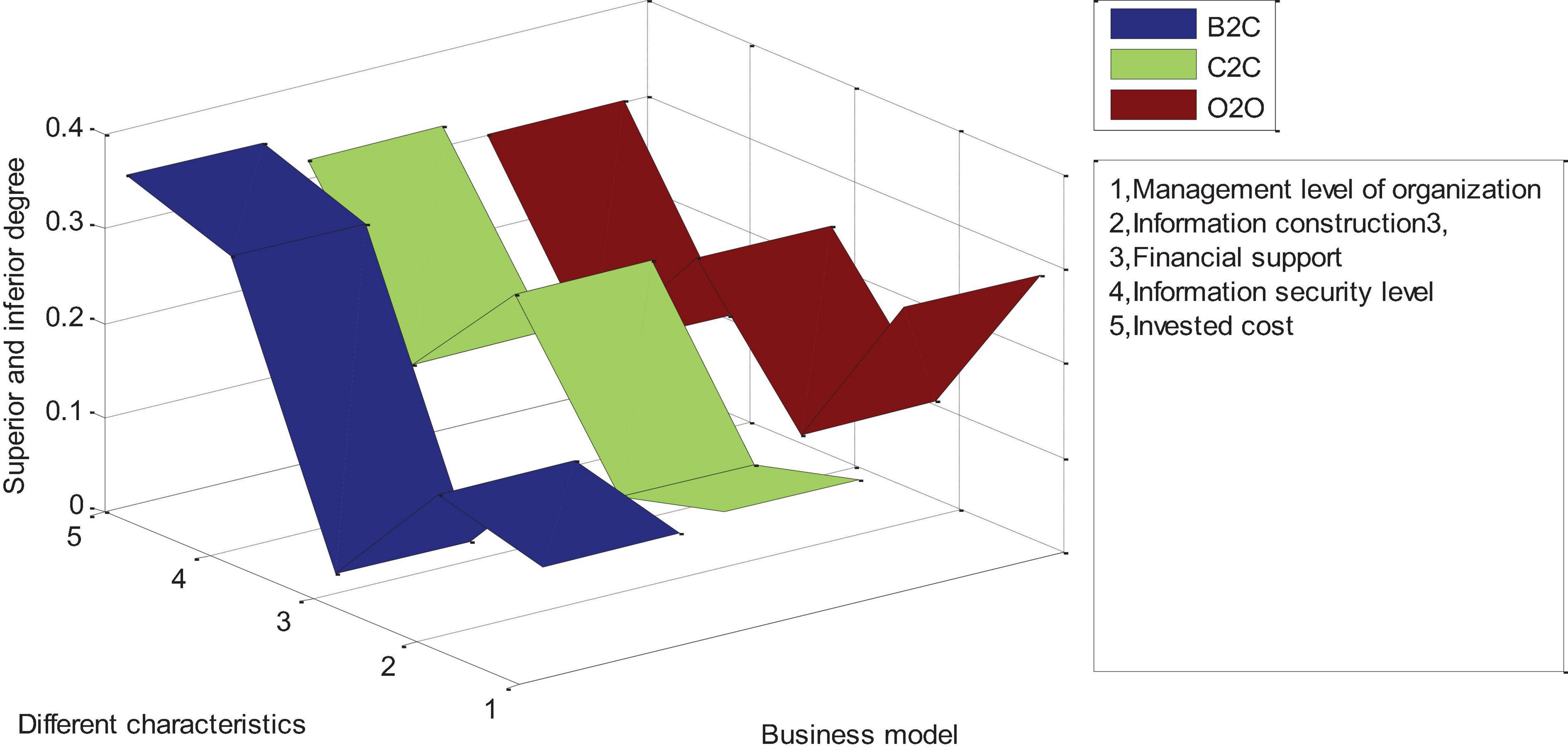

As shown in Figure 7 , for the industrial agglomeration of the B2C e-commerce model, all goods and services of the enterprise are carried out through the network, including online shopping, online payment, logistics and after-sales. They are all done over the Internet and won’t be traded face to face. This model puts forward higher requirements for industrial agglomeration enterprises. Compared with the C2C and O2O models, the selection of the B2C e-commerce model requires that the industrial agglomeration area has a good organizational management level and complete information construction, because all activities are carried out online. Among the three e-commerce models, the B2C model has the highest information security requirements and requires more financial support and sufficient strength to ensure smooth transactions. For the C2C model, the needs of enterprises are much lower than those of B2C. For industries with insufficient funds, low level of enterprise informatization and low management level, C2C e-commerce model can be selected. The industrial cluster area builds an e-commerce trading platform through website construction. Consumers can find the trading objects and negotiate the transaction through the platform. Industrial agglomeration enterprises only need to optimize platform management, maintain transaction order, formulate transaction specifications, and improve trust mechanisms. Therefore, the C2C e-commerce model has lower requirements for the company’s capital, information and management level than the B2C model. For the O2O model, the network becomes the platform for offline transactions. For industrial clusters, the function of the C2C e-commerce model is to undertake the browsing work of consumers, let consumers understand the information through the platform, and then conduct transactions online. Therefore, it is necessary to reduce the investment cost of the C2C e-commerce model, and its management level and informatization level are lower than the B2C and O2O e-commerce models. Most industrial clusters can conduct business activities through the C2C platform.

Figure 7. Advantages and disadvantages of different e-commerce in industrial agglomeration.

As the rising of Internet industry and other technologies, on the basis of the rapid expansion of e-commerce, the coordination problem of e-commerce has gradually emerged, affecting the organizational environment. At present, the research related to e-commerce and supply chain collaboration is getting more and more attention. As a new impetus for economic expansion, e-commerce has brought new impetus to the supply chain. In the process of supply chain coordination, e-commerce means making the required information more convenient and accurate, thus further enhancing the trust of the supply chain enterprises and the internal and external trust, and bringing economic benefits, the company has further expanded. In this paper, through the different applications of virtual e-commerce in industrial agglomeration, different e-commerce types highlight different characteristics in big data. Therefore, this paper analyses industrial agglomeration and electronics through literature comparison and data survey. The relationship between business, and through the investigation, we can see that the industrial agglomeration investment has been continuously expanded with the expansion of e-commerce and big data, which also proves that the future expansion of e-commerce is promising. Finally, the application of three different e-commerce models in industrial agglomeration is compared. The results show that different e-commerce models are determined by their own different, so we must choose the correct e-commerce model to adapt to the expansion of society through the actual situation.

Industrial agglomeration is an important way to enhance regional economic development, while e-commerce promotes the integration of enterprises into the world market. The author intends to analyse the problems of enterprise e-commerce in this context from the perspective of industrial agglomeration, and propose how to better realize the interaction between e-commerce and industrial agglomeration, so as to achieve the improvement of the competitiveness of enterprises in the industry.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

HY was responsible for designing the framework of the entire manuscript from topic selection to solution to experimental verification.

Research on the Path and Countermeasures of Cultivating and Expanding Rural Collective Economy in Kaifeng City.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anam, F., Asad, A., Wan, M., and Ahmad, N. Z. (2017). Analyzing the academic research trends by using university digital resources: a bibliometric study of electronic commerce in China. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 5, 1606–1613. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2017.050918

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bivand, R., and Krivoruchko, K. (2018). Big data sampling and spatial analysis: “which of the two ladles, of fig-wood or gold, is appropriate to the soup and the pot? Stat. Probab. Lett. 136, 87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.spl.2018.02.012

Cao, Y., Xia, Y., Cheng, J., Huade, Z., and Yuancai, C. (2017). A novel visible-light-driven In-based MOF/graphene oxide composite photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic activity toward the degradation of amoxicillin. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 200, 673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.07.057

Cohen, M. C., Lobel, R., and Perakis, G. (2018). Dynamic pricing through data sampling. Prod. Oper. Manag. 27, 1074–1088. doi: 10.1111/poms.12854

Fan, C., Xiao, F., and Yan, C. (2018). Research and applications of data mining techniques for improving building operational performance. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 5, 181–188. doi: 10.1007/s40518-018-0112-x

Gui, Y.-M., Wu, Z., and Gong, B.-G. (2019). Value-added service investment decision of B2C platform in competition. Kongzhi Juece Control Decis. 34, 395–405.

Google Scholar

Han, Y., Shao, X. F., Tsai, S. B., Fan, D., and Liu, W. (2021). E-government and foreign direct investment: evidence from Chinese cities. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. (JGIM) 29, 1–17. doi: 10.4018/jgim.20211101.oa42

Heiner, E., and Marc, G. (2018). Looking forward, looking back: British journal of management 2000-2015: looking forward, looking back. Br. J. Manag. 29, 3–9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12257

Irene, N. (2018). Review: electronic commerce. ITNOW 42, 31–31.

Liu, X.-F., Zhan, Z.-H., Deng, J. D., Li, Y., Gu, T., and Zhang, J. (2018). An energy efficient ant colony system for virtual machine placement in cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 22, 113–128. doi: 10.1109/tevc.2016.2623803

Nádudvari, Á, Fabiańska, M. J., Marynowski, L., Kozielska, B., Konieczyński, J., Smołka-Danielowska, D., et al. (2018). Distribution of coal and coal combustion related organic pollutants in the environment of the upper silesian industrial region. Sci. Total Environ. 62, 1462–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.092

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Navarro-Méndez, D. V., Carrera-Suárez, L. F., Sánchez-Escuderos, D., Cabedo-Fabres, M., Baquero-Escudero, M., Gallo, M., et al. (2017). Wideband double monopole for mobile, WLAN, and C2C services in vehicular applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 16, 16–19. doi: 10.1109/lawp.2016.2552398

Nik, B., Mark, W., Ranjit, S., and Michael, T. (2017). The use of microsoft excel as an electronic database for handover and coordination of patients with trauma in a district general Hospital. BMJ Innov. 3:130. doi: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2016-000182

Ning, J., Babich, V., Handley, J., and Keppo, J. (2018). Risk-aversion and B2B contracting under asymmetric information: evidence from managed print services. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 66, 392–408. doi: 10.1287/opre.2017.1673

Rezaei-Hachesu, P., Oliyaee, A., Safaie, N., and Ferdousi, R. (2017). Comparison of coronary artery disease guidelines with extracted knowledge from data mining. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 9, 95–101. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2017.16

Setiawan, A. B., Dunan, A., and Mudjianto, B. (2022). “Policies and innovations of financial technology business models in the digital economy era on the E-business ecosystem in indonesia,” in Handbook of Research on Green, Circular, and Digital Economies as Tools for Recovery and Sustainability , eds de Pablos, O. Patricia, Z. Xi, and A. Mohammad Nabil (Pennsylvania. PA: IGI Global), 22–42. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-9664-7.ch002

Sukrat, S., and Papasratorn, B. (2018). An architectural framework for developing a recommendation system to enhance vendors’ capability in C2C social commerce. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 8:22.

Suska, M. (2022). “E-commerce: the pillar of the digital economy,” in The European Union Digital Single Market , eds L. D. Dabrowski and M. Suska (Abingdon: Routledge), 63–91.

Svefors, P., Sysoev, O., Ekstrom, E. C., Persson, L. A., Arifeen, S. E., Naved, R. T., et al. (2019). Relative importance of prenatal and postnatal determinants of stunting: data mining approaches to the MINIMat cohort, Bangladesh. BMJ Open 9:e025154. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025154

Wang, K., Xu, C., Yan, Z., Guo, S., and Zomaya, A. (2017). Robust big data analytics for electricity price forecasting in the smart grid. IEEE Trans. Big Data 5, 34–45. doi: 10.1109/tbdata.2017.2723563

Wang, X.-S., and Yu, C.-Y. (2017). Impact of spatial agglomeration on industrial pollution emissions intensity in China. Zhongguo Huan. Kexue China Environ. Sci. 37, 1562–1570.

Xuan, S. U. N. (2017). Multi-indicator evaluation and analysis of coordinated industrial expansion of urban agglomerations. Urban Environ. Stud. 05:1750006. doi: 10.1142/s2345748117500063

Yang, L., Zheng, Y. Y., Wu, C. H., Dong, S. Z., Shao, X. F., and Liu, W. (2022). Deciding online and offline sales strategies when service industry customers express fairness concerns. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 16, 427–444.

Yu, P., Gong, R., and Sampat, M. (2022). “Blockchain technology in china’s digital economy: balancing regulation and innovation,” in Regulatory Aspects of Artificial Intelligence on Blockchain , ed. T. Pardis Moslemzadeh (Pennsylvania. PA: IGI Global), 132–157. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-7927-5.ch007

Zhou, Y.-Z., Li, P.-X., Wang, S.-G., Xiao, F., Li, J. Z., and Gao, L. (2017). Research progress on big data and intelligent modelling of mineral deposits. Bull. Miner. Petrol. Geochem. 36, 327–331.

Keywords : virtual e-commerce, industrial agglomeration expansion, big data, e-commerce model, standard system

Citation: Yue H (2022) Research on E-Commerce Data Standard System in the Era of Digital Economy From the Perspective of Organizational Psychology. Front. Psychol. 13:900698. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.900698

Received: 21 March 2022; Accepted: 14 April 2022; Published: 04 May 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Yue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongqiang Yue, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Articles on E-commerce

Displaying 1 - 20 of 67 articles.

How safe are your solar eclipse glasses? Cheap fakes from online marketplaces pose a threat, supply-chain experts say

Yao "Henry" Jin , Miami University and Simone Peinkofer , Michigan State University

In the market for a car? Soon you’ll be able to buy a Hyundai on Amazon − and only a Hyundai

Vivek Astvansh , McGill University

What is dropshipping? 6 things to consider before you start dropshipping as a side hustle

Brent Coker , The University of Melbourne

Rural communities are being left behind because of poor digital infrastructure, research shows

Aloysius Igboekwu , Aberystwyth University ; Maria Plotnikova , Aberystwyth University , and Sarah Lindop , Aberystwyth University

Temu: China’s answer to Amazon is already Australia’s most popular free app. What makes it so addictive?

Shasha Wang , Queensland University of Technology and Xiaoling Guo , The University of Western Australia

UPS and Teamsters agree on new contract, averting costly strike that could have delayed deliveries for consumers and retailers

Jason Miller , Michigan State University

UPS impasse with union could deliver a costly strike, disrupting brick-and -mortar businesses as well as e-commerce

The problem with cashless payments

Tristan Dissaux , Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB)

Five emerging trends that could change our lives online

Theo Tzanidis , University of the West of Scotland

How many Amazon packages get delivered each year?

Anne Goodchild , University of Washington and Rishi Verma , University of Washington

Could cargo bike deliveries help green e-commerce ?

Antoine Robichet , Université Gustave Eiffel and Patrick Nierat , Université Gustave Eiffel

Fast fashion: why your online returns may end up in landfill – and what can be done about it

Patsy Perry , Manchester Metropolitan University

A heated steering wheel for $20 a month? What’s driving the subscriptions economy

Louise Grimmer , University of Tasmania

ACCC says consumers need more choices about what online marketplaces are doing with their data

Katharine Kemp , UNSW Sydney

What it would take for more Ghanaians to adopt mobile payment systems

Masud Ibrahim , AAM University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development and Robert E. Hinson , University of Ghana

Ghana’s electronic transaction tax: not a bad idea, but must be properly designed

Adu Owusu Sarkodie , University of Ghana

Burnout by design? Warehouse and shipping workers pay the hidden cost of the holiday season

Christopher O'Neill , Monash University ; Jake Goldenfein , The University of Melbourne ; Jathan Sadowski , Monash University ; Lauren Kate Kelly , RMIT University , and Thao Phan , Monash University

How COVID-19 has increased the risk of compulsive buying behavior and online shopping addiction among young consumers

Navaz Naghavi , Taylor's University ; Hassam Waheed , University of Derby ; Kelly-Ann Allen , Monash University , and Saeed Pahlevansharif , Taylor's University

Many of New Zealand’s most popular websites use ‘dark patterns’ to manipulate users – is it time to regulate?

Cherie Lacey , Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and Alex Beattie , Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

How retail giants could thrive on the post-pandemic high street

Tamsin McLaren , University of Bath

Related Topics

- Digital economy

- Online retail

- Online shopping

Top contributors

Professor of Marketing and Consumer Behaviour, Queensland University of Technology

Senior Lecturer in Retail Marketing, University of Tasmania

Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Director, Supply Chain Transportation and Logistics Center, University of Washington

Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management, Michigan State University

Professor, Director: School of Consumer Intelligence and Information Systems, University of Johannesburg

Co-director, Centre for Digital Business, University of Salford

Senior Lecturer and Co-Director of the Centre for Digital Business, University of Salford

Professor of Accounting, University of Portsmouth

Professor of Marketing and Innovation, Director, Marketing Innovation and The Chinese and Emerging Economies (MICEE) Network, Warwick Business School, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

Senior Lecturer in Centre for Digital Business, University of Salford

Professor of Marketing and Retail, University of Stirling

Assistant Professor, Northeastern University

Senior Lecturer, The University of Melbourne

Associate Professor of Political Science, Brock University

Cartier Chaired Professor of Behavioural Sciences, Full Professor, Department of Entrepreneurship, ESCP Business School

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

20 years of Electronic Commerce Research

- Published: 29 March 2021

- Volume 21 , pages 1–40, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Satish Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5200-1476 1 ,

- Weng Marc Lim 2 , 3 ,

- Nitesh Pandey 1 &

- J. Christopher Westland 4

13k Accesses

110 Citations

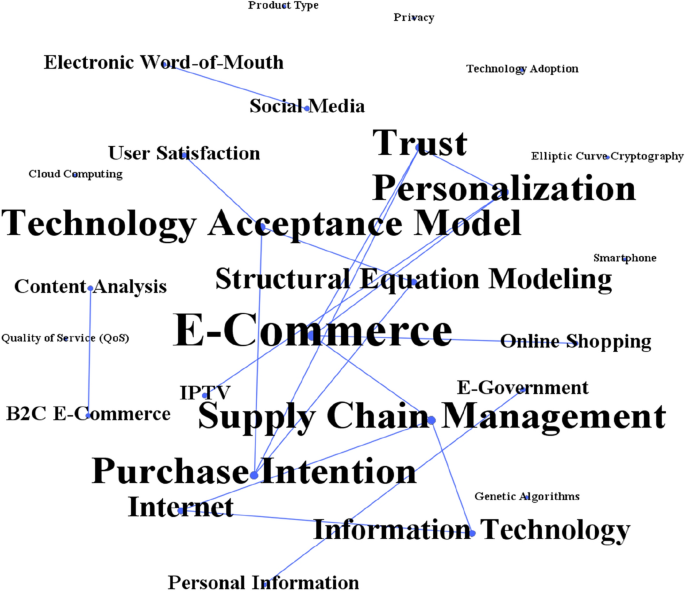

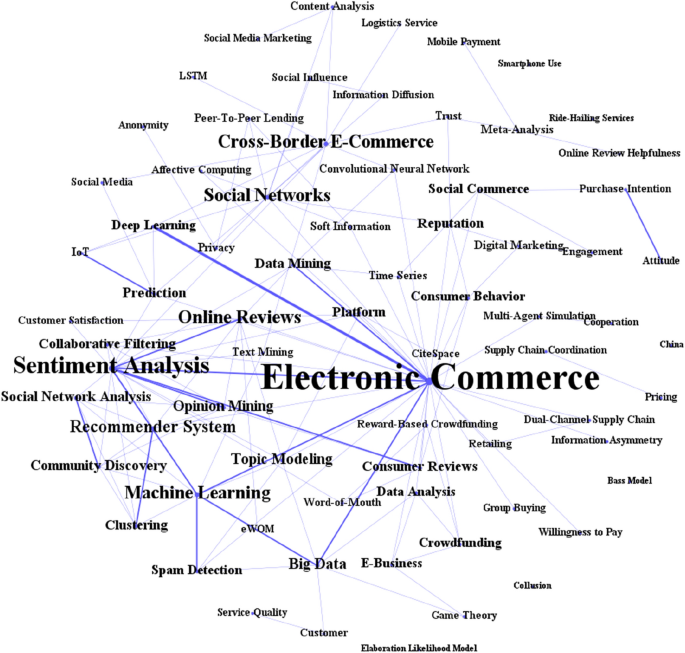

Explore all metrics

2021 marks the 20th anniversary of the founding of Electronic Commerce Research ( ECR ). The journal has changed substantially over its life, reflecting the wider changes in the tools and commercial focus of electronic commerce. ECR ’s early focus was telecommunications and electronic commerce. After reorganization and new editorship in 2014, that focus expanded to embrace emerging tools, business models, and applications in electronic commerce, with an emphasis on the innovations and the vibrant growth of electronic commerce in Asia. Over this time, ECR ’s impact and volume of publications have grown rapidly, and ECR is considered one of the premier journals in its discipline. This invited research summarizes the evolution of ECR ’s research focus over its history.

Similar content being viewed by others

How digital technologies reshape marketing: evidence from a qualitative investigation

Federica Pascucci, Elisabetta Savelli & Giacomo Gistri

Digital technologies: tensions in privacy and data

Sara Quach, Park Thaichon, … Robert W. Palmatier

Artificial intelligence in E-Commerce: a bibliometric study and literature review

Ransome Epie Bawack, Samuel Fosso Wamba, … Shahriar Akter

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The year 2021 marks the 20th anniversary of the founding of Electronic Commerce Research ( ECR ). The journal has changed substantially over its life, reflecting the wider changes in the tools and commercial focus of electronic commerce. ECR ’s early focus was on telecommunications and electronic commerce. After reorganization and new editorship in 2014, that focus expanded to embrace emerging tools, business models, and applications in electronic commerce, with an emphasis on emerging technologies and the vibrant growth of electronic commerce in Asia. Over these years, ECR has steadily improved its stature and impact, as evidenced through various quantitative (e.g., citations, impact factors) and qualitative (e.g., peer-informed journal ranks) measures. According to Clarivate Analytics, ECR ’s impact factor in 2019 was 2.507, Footnote 1 which means that articles published in ECR between 2017 and 2018 received an average of 2.507 citations from journals indexed in Web of Science in 2019. The five-year impact factor of ECR was 2.643, 1 which indicates that articles published in ECR between 2014 and 2018 received an average of 2.643 citations from Web of Science-indexed journals in 2019. According to Scopus, ECR ’s CiteScore was 4.3, Footnote 2 which implies that articles published in ECR between 2016 and 2019 received an average of 4.3 citations from journals indexed in Scopus in 2019. The source normalized impact per paper (SNIP) of ECR was 1.962, which suggests that the average citations received by articles in the journal is 1.962 times the average citations received by articles in the same subject area of Scopus-indexed journals in 2019. Apart from these quantitative measures, ECR has also been rated highly by peers in the field, as seen through journal quality lists. For example, ECR has been consistently ranked as an “A” journal by the Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA 2010) and the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC 2013, 2016, 2019) journal ranking lists.

This research presents a 20-year retrospective bibliometric analysis of the evolution of context and focus of ECR ’s articles [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. To curate a rich bibliometric overview of ECR ’s scientific achievements, this study explores seven research questions (RQ) which are commonly asked by both authors and our Editorial Board members:

RQ1. What is the trend of publication and citation in ECR ?

RQ2. Who are the most prolific contributors (authors, institutions, and countries) in ECR ?

RQ3. What are the most influential publications in ECR ?

RQ4. Where have ECR publications been cited the most?

RQ5. What is the trend of collaboration in ECR ?

RQ6. Who are the most important constituents of the collaboration network in ECR ?

RQ7. What are the major research themes in ECR ?

A bibliometric analysis can offer a broad, systematic overview of the literature to delineate the evolution of electronic commerce technologies, and point the direction to trending topics and methodologies [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Our research is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines our bibliometric methodology. Section 3 goes on to performance analysis to uncover contributor and journal performance trends (RQ1–RQ4), the co-authorship analysis performed to unpack collaboration and constituent characteristics (RQ5–RQ6), and the bibliometric coupling and keyword analyses used to reveal the major themes and trends within the ECR corpus (RQ7). Section 4 applies graph theoretic analysis. Section 5 applies cluster analysis. Section 6 applies thematic analysis. Finally, we conclude the study with key takeaways from this retrospective.

2 Methodology

Bibliometric methodologies apply graph theoretic and statistical tools for analysis of bibliographic data [ 15 ] and include performance analysis and science mapping [ 16 ]. To answer research question 1 to research question 4, this study uses performance analysis to measure the output of authors’ productivity and impact, with productivity measured using publications per year, and impact measured using citations per year. We begin by measuring the productivity and impact of ECR , and then the productivity and impact of authors, institutions, and countries using both publications and citations per year metrics on top of ancillary measures such as citations per publication and h -index. Finally, we measure the impact of ECR articles using citations and shed light on prominent publication outlets citing ECR articles.

To answer research question 5 to research question 7, this study uses co-authorship, bibliographic coupling, and keyword analyses. We begin by conducting a co-authorship analysis, which is a network-based analysis that scrutinizes the relationships among journal contributors [ 17 ]. Next, we perform bibliographic coupling to obtain the major themes within the ECR corpus. The assumption of bibliographic coupling connotes that two documents would be similar in content if they share similar references [ 18 , 19 ]. Using article references, a network was created, wherein shared references were assigned with edge weights and documents were denoted with nodes. The documents were divided into thematic clusters using the Newman and Girvan [ 20 ] algorithm. Finally, we track the development of themes throughout different time periods using a temporal keyword analysis. The assumption of this analysis suggest that keywords are representative of the author’s intent [ 21 ] and thus important for understanding the prominence of themes pursued by authors across different time periods. Indeed, we found that these bibliometric methods complement each other relatively well, as bibliographic coupling was useful to locate general themes while keywords were useful to understand specific topics.

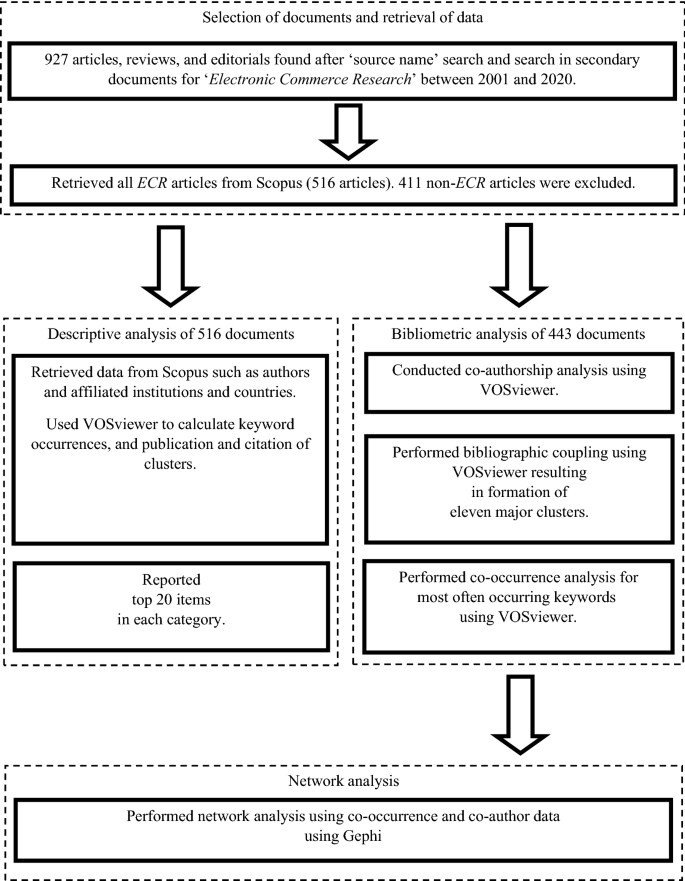

To acquire bibliographic data of ECR articles for the bibliometric analyses mentioned above, this study uses the Scopus database, which is one of the largest academic database that is almost 60% larger than the Web of Science [ 21 ]. Past research has also indicated that the citations presented within the Scopus database correlate more with expert judgement as compared to Google Scholar and Web of Science [ 22 ]. We begin by conducting a source search for “ Electronic Commerce Research ,” which resulted in 927 articles, and after filtering out non- ECR articles, we obtain a list of 516 ECR articles (see Fig. 1 ). However, ECR only gained Scopus indexation in 2005, and thus, only 443 ECR articles (2005–2020) contained full bibliometric data, whereas the remaining 73 ECR articles (2001–2004) contained only partial bibliometric data (e.g., no affiliation, abstract, and keyword entry). All 516 ECR articles were fetched and included in the performance analysis as partial bibliometric data was sufficient, but only 443 ECR articles were included in science mapping (e.g., co-authorship, bibliographic coupling, and keyword analyses using VOSviewer [ 23 ] and Gephi [ 24 ]) as full bibliometric data was required. This collection of articles met the minimum sample size of 200 articles for bibliometric analysis recommended by Rogers, Szomszor, and Adams [ 25 ].

Research design. Note Bibliometric analysis was conducted for only 443 (primary) documents as 73 (secondary) documents lack full data (affiliation, abstract and keywords)

3 Performance analysis: productivity and impact

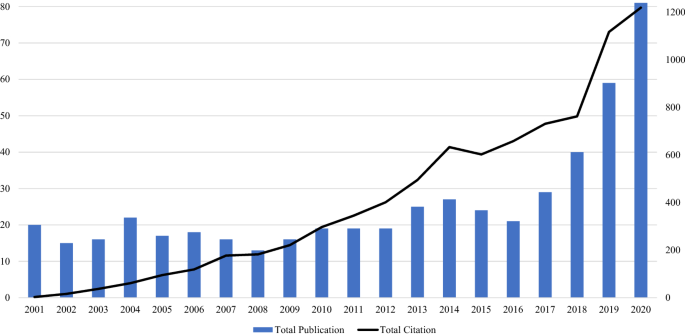

The publication and citation trends of ECR between 2001 and 2020 are presented in Fig. 2 (RQ1). In terms of publication, the number of articles published in ECR has grown from 20 articles per year in 2001 to 81 articles per year in 2020, with an average annual growth rate of 7.64%. In terms of citations, the number of citations that ECR articles received has grown from three citations in 2001 to 1219 citations in 2020, with an average annual growth rate of 37.19%. These statistics suggest that ECR ’s publications and citations have seen exponential growth since its inception, and that the journal’s citations have grown at a much faster rate than its publication, which is very positive.

Annual publication and citation structure of ECR

3.2 Authors

The most prolific authors in ECR between 2001 and 2020 are presented in Table 1 (RQ2). The most prolific author is Jian Mou, who has published six articles in ECR , which have garnered a total of 95 citations. This is followed by Yan-Ping Liu and Liyi Zhang, who have published three articles each in ECR , which have received a total of 46 and 42 citations, respectively. Among the top 20 contributors, the author with the highest citation average per publication is Katina Michael (TC/TP and TC/TCP = 59 citations), who is followed closely by Yue Guo (TC/TP and TC/TCP = 51 citations); they are the only two authors who have an average citation greater than 50 for their ECR articles.

3.3 Institutions

The most prolific institutions for ECR between 2001 and 2020 are presented in Table 2 (RQ2). IBM, with 14 articles and 371 citations, emerges as the highest contributing institution to ECR . It is surprising yet encouraging to see a high number of contributions coming from practice, which reflects the ECR ’s receptiveness to publish industry-relevant research. Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that this contribution is derived from the collective effort of IBM’s research labs around the world (e.g., Delhi, Haifa, and New York)—a unique advantage that most higher education institutions do not enjoy unless they have full-fledged research-active international branch campuses around the world. The second and third most contributing institutions are Nanjing University and Xi’an Jiaotong University, with 11 and 10 articles that have been cited 116 and 29 times, respectively. This is yet another interesting observation, as the contributions by Chinese institutions suggest that ECR is a truly international journal despite its origins and operations stemming in the United States. Finally, the University of California (TC/TP and TC/TCP = 34.86 citations) emerges as the institution that averages the most citations per publication, followed by IBM (TC/TP and TC/TCP = 26.50 citations) and Texas Tech University (TC/TP and TC/TCP = 26.20 citations).

3.4 Countries

The most prolific countries in ECR between 2001 and 2020 are presented in Table 3 (RQ2). China emerges as the most prolific contributor, with 152 articles and 1066 citations. This is followed by the United States, which has contributed 143 articles and 2813 citations. No country other than China and the United States has contributed more than 50 articles to ECR . Nevertheless, it is important to note that ECR also receives contributions from many countries around the world, as the remaining ± 50% of contributions in the top 20 list comes from 18 different countries across Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

3.5 Articles

The most cited articles in ECR between 2001 and 2020 are presented in Table 4 (RQ3). The most cited article published in ECR during this period is Füller et al.’s [ 26 ] article on the role of virtual communities in new product development (TC = 270). This is followed by Sotiriadis and van Zyl’s [ 27 ] article on electronic word of mouth and its effects on the tourism industry (TC = 188), Nonnecke et al.’s [ 28 ] article on the phenomena of ‘lurking’ in online communities (TC = 185), Lehdonvirta’s [ 29 ] article on the factors that drive virtual product purchases (TC = 170), and Bae and Lee’s [ 30 ] article on the effect of gender on consumer perception of online reviews (TC = 125). The diversity of topics in the most cited articles indicate that electronic commerce is indeed a multi-faceted subject, which we will explore in detail in the later sections.

3.6 Publication outlets

The publication outlets that have cited ECR articles the most between 2001 and 2020 are presented in Table 5 (RQ4). The list includes many prestigious journals such as International Journal of Information Management (ABDC = A*, IF = 8.210), Information and Management (ABDC = A*, IF = 5.155), and Decision Support Systems (ABDC = A*, IF = 4.721), among others. The presence of such reputed journals reflects ECR ’s own reputation of high standing among its peers. Apart from ECR , the publication outlets that have highly cited ECR include Lecture Notes in Computer Science including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics (TC = 218), Computers in Human Behavior (TC = 95), and ACM International Conference Proceeding Series (TC = 88), which reflect the diversity in publication outlets that ECR is making an impact (e.g., book, conference, journal).

4 Co-authorship analysis: scientific network

4.1 co-authorship.

The co-authorships in ECR between 2005 and 2020 are presented in Table 6 (RQ5). On the one hand, the co-authorship analysis shows that the share of articles written by a single author has gone down over the years from 10.94% (2005–2008) to 8.61% (2017–2020). The small and decreasing share of single-authored articles do not come as a surprise given the importance and proliferation of collaboration to address increasing thematic and methodological complexity in research [ 31 ]. On the other hand, the co-authorship analysis shows that multi-authored articles have increased their share in ECR , especially articles with three authors or more. In particular, the share of articles with three and five or more authors have increased from 31.25% and 4.69% between 2005 and 2008 to 34.45% and 14.35% between 2017 and 2020, respectively. These statistics suggests that collaboration is growing in prominence, which is consistent with recent observations reported by other premier journals in business [ 32 , 33 , 34 ], and that ECR is a good home for collaborative research.

4.2 Network centrality

The most important authors, institutions, and countries across different measures of centrality are presented in Table 7 (RQ6). In this study, we employ four measures of centrality: degree of centrality, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and eigen centrality.

In essence, degree of centrality refers to the number of relational ties a node has in a network. In contrast, betweenness centrality refers to a node’s ability to connect otherwise unconnected groups of nodes, wherein nodes act as a gateway for the flow of information. Whereas, closeness centrality refers to a node’s closeness to every other node in the network, whereby nodes that reflect a greater number of shortest paths than others in a network indicates the ability of those nodes to transmit information and knowledge across the network with relative ease. Finally, eigen centrality refers to a node’s relative importance in a network, whereby nodes that are connected to other highly connected nodes are crucial to information transfer.

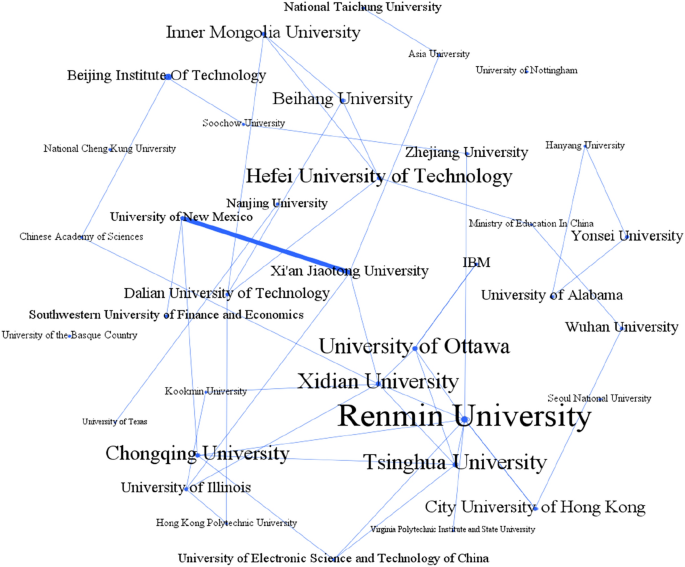

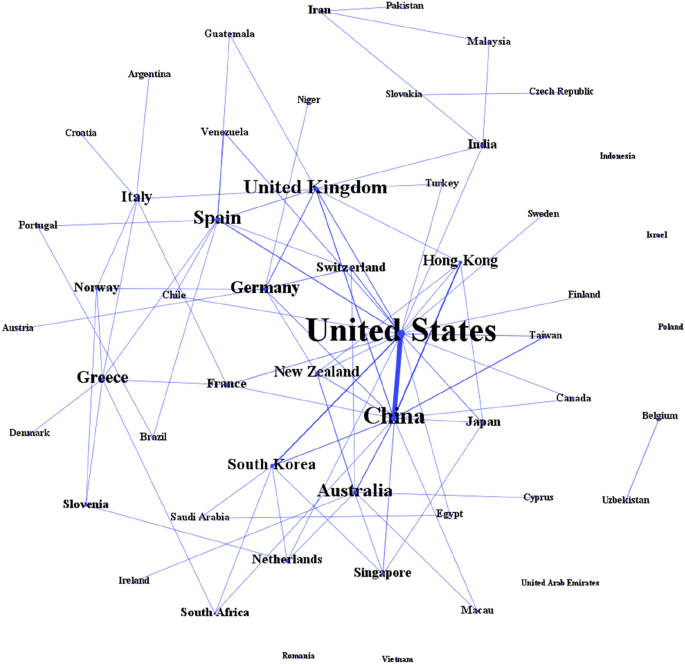

In terms of authors, Jian Mou emerged as the most important author for degree of centrality and betweenness centrality, whereas Xin Luo and Jian-xin Wang were flagged as the most important authors for closeness centrality and eigen centrality, respectively. In terms of institutions, Renmin University emerged as the most important institution for degree centrality and betweenness centrality, whereas the University of Ottawa was rated as the most important institution for closeness centrality and eigen centrality. In terms of countries, China emerged as the most important country for betweenness centrality, whereas the United States emerged as the most important country for the other three measures of centrality. Collectively, these findings indicate the most important constituents for degree of centrality, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and eigen centrality in terms of authors, institutions, and countries.

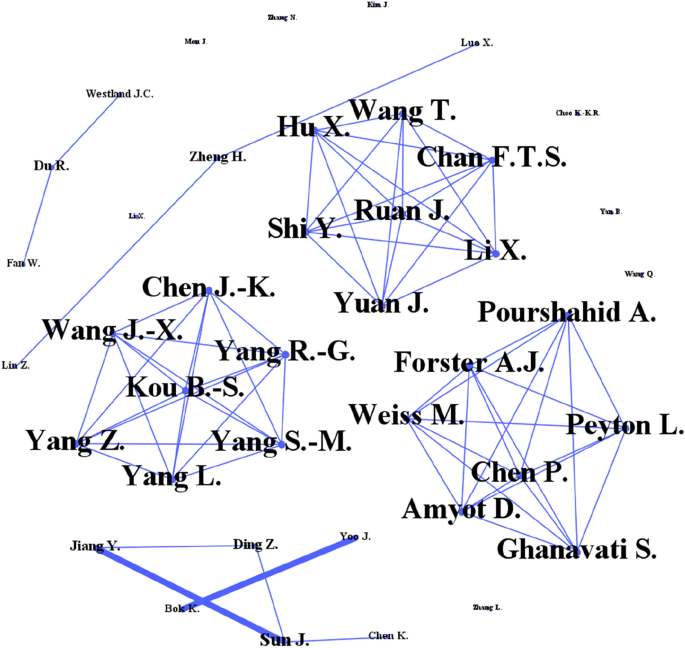

4.3 Collaboration network

The author collaboration network in Fig. 3 indicates that authors groups in ECR are fairly separated from each other, especially among highly connected authors (more than five links in the network). This suggests that most authors in ECR chose to work in a single team rather than across multiple teams. The institution collaboration network in Fig. 4 reaffirms our earlier finding that Renmin University is indeed the most important constituent of the network, especially among highly connected institutions (more than five links in the network). The institution collaboration network also appears to be more complex than the author collaboration network, wherein institutions appear to be far more connected to each other, indicating a good degree of collaboration across institutional lines. The country network in Fig. 5 presents a similar network scenario, where countries appear to be fairly well connected, with the United States being at the center of the country-level collaboration network. These findings suggest that ECR authors collaborate more actively across institutions and countries than teams.

Author co-authorship network. Note Threshold for inclusion is five or more links in the network

Institution co-authorship network. Note Threshold for inclusion is five or more links in the network

Country co-authorship network. Note Threshold for inclusion is five or more links in the network

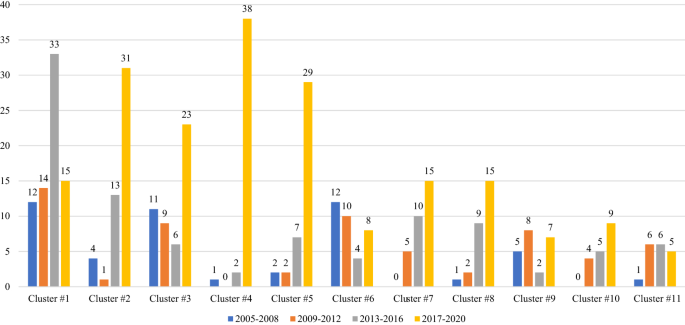

5 Bibliographic coupling: thematic clusters

Bibliographic coupling is applied to unpack the major clusters (themes) within the ECR corpus. The method is predicated on the assumption that documents that share the same references are similar in content [ 18 , 35 ]. The application of bibliographic coupling on 443 ECR articles resulted in the formation of 30 clusters, wherein 11 major clusters were identified. The 11 major clusters, which contained 401 (or 90.5%) ECR articles, were ordered based on number of publications and average publication years, with more recent clusters ordered before older clusters in the case of clusters sharing the same number of publications. The summary of the 11 major clusters, which take center stage in this study, is presented in Table 8 .

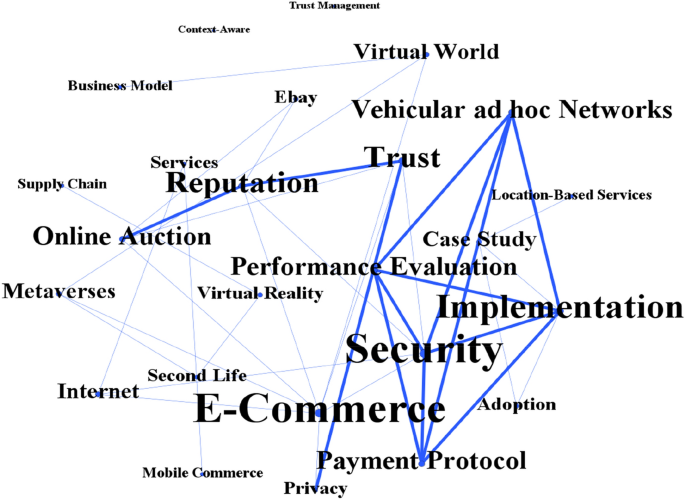

5.1 Cluster #1: online privacy and security

Cluster #1 contains 74 articles that have been cited 963 times with an average publication year of 2013.09. The most cited article in this cluster is Zarmpou et al.’s [ 36 ] article on the adoption of mobile services. This is followed by Chaudhry et al.’s [ 37 ] article on user encryption schemes for e-payment systems, and Antoniou and Batten’s [ 38 ] article on purchaser’s privacy and trust in online transactions. Other articles in this cluster have considered topics such as e-commerce trust models [ 39 ], consumer privacy [ 40 ], cybercrime and cybersecurity issues [ 41 ], gender differences [ 42 ], and the development and implementation of various authentication systems [ 43 , 44 ]. Thus, ECR articles in this cluster appear to be centered on online privacy and security issues , including equivalent solutions for improved authentication and encryption to improve trust in electronic commerce.

5.2 Cluster #2: online channels and optimization

Cluster #2 contains 49 articles that have been cited 415 times with an average publication year of 2016.67. The most cited article in this cluster is Jeffrey and Hodge’s [ 45 ] article on impulse purchases in online shopping. This is followed by Biller et al.’s [ 46 ] article on dynamic pricing for online retailing in the automotive industry, and Yan’s [ 47 ] article on profit sharing and firm performance in manufacturer-retailer dual-channel supply chains. Other articles in this cluster have examined online channels such as peer-to-peer networks and social commerce [ 48 , 49 ] and optimal supply chain configuration [ 50 , 51 ]. Thus, ECR articles in this cluster appear to be concentrated on online channels and optimization , particularly in terms of the channel characteristics and price and supply chain optimization in electronic commerce.

5.3 Cluster #3: online engagement and preferences

Cluster #3 contains 49 articles that have been cited 982 times with an average publication year of 2013.98. The most cited article in this cluster is Nonnecke et al.’s [ 28 ] article on online community participation. This is followed by Sila’s [ 52 ] article on business-to-business electronic commerce technologies, and Ozok and Wei’s [ 53 ] article on consumer preferences of using mobile and stationary devices. Other articles in this cluster have explored topics such as online community participation and social impact across countries [ 54 ], online opinions across regions and its impact on consumer preferences [ 55 , 56 ], content and context factors [ 57 ], data mining techniques [ 58 ], and recommender systems and their application in online environments [ 59 , 60 ]. Thus, ECR articles in this cluster appear to be focused on online engagement and preferences , including the adoption and usage of technology (e.g., data mining, recommender systems) to curate engagement and shape preferences among target customers in electronic commerce.

5.4 Cluster #4: online market sentiments and analyses