Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on March 10, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

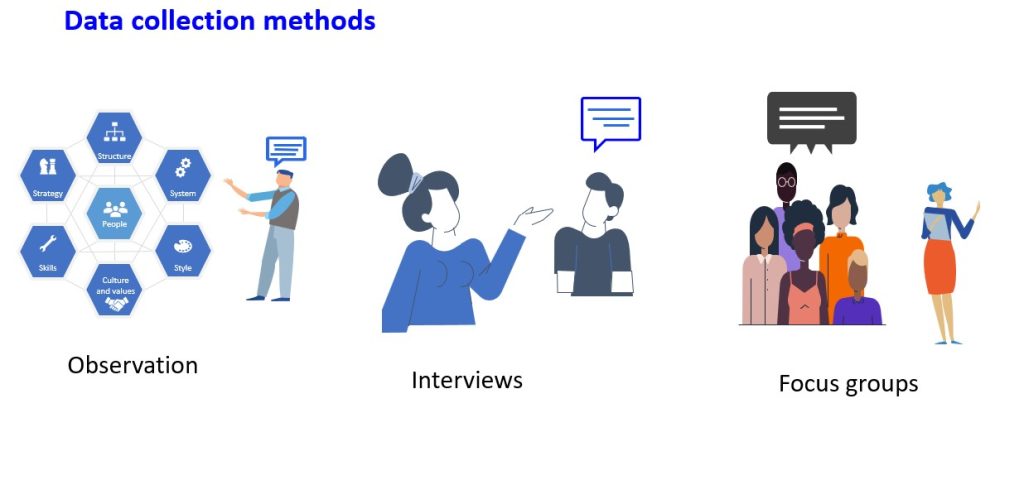

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure.

- Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order.

- Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing.

- Semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research .

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate research biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyze because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered “the best of both worlds.”

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalizability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualize your initial hypotheses.

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions.

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behavior, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large surveys . However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to “cherry-pick” responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic.

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no.”

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilize this research method.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favorably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behavior accordingly.

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/interviews-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, unstructured interview | definition, guide & examples, structured interview | definition, guide & examples, semi-structured interview | definition, guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Much of what we learned in the previous chapter on survey research applies to quantitative interviews as well. In fact, quantitative interviews are sometimes referred to as survey interviews because they resemble survey-style question-and-answer formats. They might also be called standardized interviews . The difference between surveys and standardized interviews is that questions and answer options are read to respondents in a standardized interview, rather than having respondents complete a survey on their own. As with surveys, the questions posed in a standardized interview tend to be closed-ended. There are instances in which a quantitative interviewer might pose a few open-ended questions as well. In these cases, the coding process works somewhat differently than coding in-depth interview data. We will describe this process in the following section.

In quantitative interviews, an interview schedule is used to guide the researcher as he or she poses questions and answer options to respondents. An interview schedule is usually more rigid than an interview guide. It contains the list of questions and answer options that the researcher will read to respondents. Whereas qualitative researchers emphasize respondents’ roles in helping to determine how an interview progresses, in a quantitative interview, consistency in the way that questions and answer options are presented is very important. The aim is to pose every question-and-answer option in the very same way to every respondent. This is done to minimize interviewer effect, or possible changes in the way an interviewee responds based on how or when questions and answer options are presented by the interviewer.

Quantitative interviews may be recorded, but because questions tend to be closed-ended, taking notes during the interview is less disruptive than it can be during a qualitative interview. If a quantitative interview contains open-ended questions, recording the interview is advised. It may also be helpful to record quantitative interviews if a researcher wishes to assess possible interview effect. Noticeable differences in responses might be more attributable to interviewer effect than to any real respondent differences. Having a recording of the interview can help a researcher make such determinations.

Quantitative interviewers are usually more concerned with gathering data from a large, representative sample. Collecting data from many people via interviews can be quite laborious. In the past, telephone interviewing was quite common; however, growth in the use of mobile phones has raised concern regarding whether or not traditional landline telephone interviews and surveys are now representative of the general population (Busse & Fuchs, 2012). Indeed, there are other drawbacks to telephone interviews. Aside from the obvious problem that not everyone has a phone (mobile or landline), research shows that phone interview respondents were less cooperative, less engaged in the interview, and more likely to express dissatisfaction with the length of the interview than were face-to-face respondents (Holbrook, Green, & Krosnick, 2003, p. 79). Holbrook et al.’s research also demonstrated that telephone respondents were more suspicious of the interview process and more likely than face-to-face respondents to present themselves in a socially desirable manner.

Research Methods, Data Collection and Ethics Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » 500+ Quantitative Research Titles and Topics

500+ Quantitative Research Titles and Topics

Table of Contents

Quantitative research involves collecting and analyzing numerical data to identify patterns, trends, and relationships among variables. This method is widely used in social sciences, psychology , economics , and other fields where researchers aim to understand human behavior and phenomena through statistical analysis. If you are looking for a quantitative research topic, there are numerous areas to explore, from analyzing data on a specific population to studying the effects of a particular intervention or treatment. In this post, we will provide some ideas for quantitative research topics that may inspire you and help you narrow down your interests.

Quantitative Research Titles

Quantitative Research Titles are as follows:

Business and Economics

- “Statistical Analysis of Supply Chain Disruptions on Retail Sales”

- “Quantitative Examination of Consumer Loyalty Programs in the Fast Food Industry”

- “Predicting Stock Market Trends Using Machine Learning Algorithms”

- “Influence of Workplace Environment on Employee Productivity: A Quantitative Study”

- “Impact of Economic Policies on Small Businesses: A Regression Analysis”

- “Customer Satisfaction and Profit Margins: A Quantitative Correlation Study”

- “Analyzing the Role of Marketing in Brand Recognition: A Statistical Overview”

- “Quantitative Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Trust”

- “Price Elasticity of Demand for Luxury Goods: A Case Study”

- “The Relationship Between Fiscal Policy and Inflation Rates: A Time-Series Analysis”

- “Factors Influencing E-commerce Conversion Rates: A Quantitative Exploration”

- “Examining the Correlation Between Interest Rates and Consumer Spending”

- “Standardized Testing and Academic Performance: A Quantitative Evaluation”

- “Teaching Strategies and Student Learning Outcomes in Secondary Schools: A Quantitative Study”

- “The Relationship Between Extracurricular Activities and Academic Success”

- “Influence of Parental Involvement on Children’s Educational Achievements”

- “Digital Literacy in Primary Schools: A Quantitative Assessment”

- “Learning Outcomes in Blended vs. Traditional Classrooms: A Comparative Analysis”

- “Correlation Between Teacher Experience and Student Success Rates”

- “Analyzing the Impact of Classroom Technology on Reading Comprehension”

- “Gender Differences in STEM Fields: A Quantitative Analysis of Enrollment Data”

- “The Relationship Between Homework Load and Academic Burnout”

- “Assessment of Special Education Programs in Public Schools”

- “Role of Peer Tutoring in Improving Academic Performance: A Quantitative Study”

Medicine and Health Sciences

- “The Impact of Sleep Duration on Cardiovascular Health: A Cross-sectional Study”

- “Analyzing the Efficacy of Various Antidepressants: A Meta-Analysis”

- “Patient Satisfaction in Telehealth Services: A Quantitative Assessment”

- “Dietary Habits and Incidence of Heart Disease: A Quantitative Review”

- “Correlations Between Stress Levels and Immune System Functioning”

- “Smoking and Lung Function: A Quantitative Analysis”

- “Influence of Physical Activity on Mental Health in Older Adults”

- “Antibiotic Resistance Patterns in Community Hospitals: A Quantitative Study”

- “The Efficacy of Vaccination Programs in Controlling Disease Spread: A Time-Series Analysis”

- “Role of Social Determinants in Health Outcomes: A Quantitative Exploration”

- “Impact of Hospital Design on Patient Recovery Rates”

- “Quantitative Analysis of Dietary Choices and Obesity Rates in Children”

Social Sciences

- “Examining Social Inequality through Wage Distribution: A Quantitative Study”

- “Impact of Parental Divorce on Child Development: A Longitudinal Study”

- “Social Media and its Effect on Political Polarization: A Quantitative Analysis”

- “The Relationship Between Religion and Social Attitudes: A Statistical Overview”

- “Influence of Socioeconomic Status on Educational Achievement”

- “Quantifying the Effects of Community Programs on Crime Reduction”

- “Public Opinion and Immigration Policies: A Quantitative Exploration”

- “Analyzing the Gender Representation in Political Offices: A Quantitative Study”

- “Impact of Mass Media on Public Opinion: A Regression Analysis”

- “Influence of Urban Design on Social Interactions in Communities”

- “The Role of Social Support in Mental Health Outcomes: A Quantitative Analysis”

- “Examining the Relationship Between Substance Abuse and Employment Status”

Engineering and Technology

- “Performance Evaluation of Different Machine Learning Algorithms in Autonomous Vehicles”

- “Material Science: A Quantitative Analysis of Stress-Strain Properties in Various Alloys”

- “Impacts of Data Center Cooling Solutions on Energy Consumption”

- “Analyzing the Reliability of Renewable Energy Sources in Grid Management”

- “Optimization of 5G Network Performance: A Quantitative Assessment”

- “Quantifying the Effects of Aerodynamics on Fuel Efficiency in Commercial Airplanes”

- “The Relationship Between Software Complexity and Bug Frequency”

- “Machine Learning in Predictive Maintenance: A Quantitative Analysis”

- “Wearable Technologies and their Impact on Healthcare Monitoring”

- “Quantitative Assessment of Cybersecurity Measures in Financial Institutions”

- “Analysis of Noise Pollution from Urban Transportation Systems”

- “The Influence of Architectural Design on Energy Efficiency in Buildings”

Quantitative Research Topics

Quantitative Research Topics are as follows:

- The effects of social media on self-esteem among teenagers.

- A comparative study of academic achievement among students of single-sex and co-educational schools.

- The impact of gender on leadership styles in the workplace.

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic performance of students.

- The effect of mindfulness meditation on stress levels in college students.

- The relationship between employee motivation and job satisfaction.

- The effectiveness of online learning compared to traditional classroom learning.

- The correlation between sleep duration and academic performance among college students.

- The impact of exercise on mental health among adults.

- The relationship between social support and psychological well-being among cancer patients.

- The effect of caffeine consumption on sleep quality.

- A comparative study of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depression.

- The relationship between physical attractiveness and job opportunities.

- The correlation between smartphone addiction and academic performance among high school students.

- The impact of music on memory recall among adults.

- The effectiveness of parental control software in limiting children’s online activity.

- The relationship between social media use and body image dissatisfaction among young adults.

- The correlation between academic achievement and parental involvement among minority students.

- The impact of early childhood education on academic performance in later years.

- The effectiveness of employee training and development programs in improving organizational performance.

- The relationship between socioeconomic status and access to healthcare services.

- The correlation between social support and academic achievement among college students.

- The impact of technology on communication skills among children.

- The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction programs in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- The relationship between employee turnover and organizational culture.

- The correlation between job satisfaction and employee engagement.

- The impact of video game violence on aggressive behavior among children.

- The effectiveness of nutritional education in promoting healthy eating habits among adolescents.

- The relationship between bullying and academic performance among middle school students.

- The correlation between teacher expectations and student achievement.

- The impact of gender stereotypes on career choices among high school students.

- The effectiveness of anger management programs in reducing violent behavior.

- The relationship between social support and recovery from substance abuse.

- The correlation between parent-child communication and adolescent drug use.

- The impact of technology on family relationships.

- The effectiveness of smoking cessation programs in promoting long-term abstinence.

- The relationship between personality traits and academic achievement.

- The correlation between stress and job performance among healthcare professionals.

- The impact of online privacy concerns on social media use.

- The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in treating anxiety disorders.

- The relationship between teacher feedback and student motivation.

- The correlation between physical activity and academic performance among elementary school students.

- The impact of parental divorce on academic achievement among children.

- The effectiveness of diversity training in improving workplace relationships.

- The relationship between childhood trauma and adult mental health.

- The correlation between parental involvement and substance abuse among adolescents.

- The impact of social media use on romantic relationships among young adults.

- The effectiveness of assertiveness training in improving communication skills.

- The relationship between parental expectations and academic achievement among high school students.

- The correlation between sleep quality and mood among adults.

- The impact of video game addiction on academic performance among college students.

- The effectiveness of group therapy in treating eating disorders.

- The relationship between job stress and job performance among teachers.

- The correlation between mindfulness and emotional regulation.

- The impact of social media use on self-esteem among college students.

- The effectiveness of parent-teacher communication in promoting academic achievement among elementary school students.

- The impact of renewable energy policies on carbon emissions

- The relationship between employee motivation and job performance

- The effectiveness of psychotherapy in treating eating disorders

- The correlation between physical activity and cognitive function in older adults

- The effect of childhood poverty on adult health outcomes

- The impact of urbanization on biodiversity conservation

- The relationship between work-life balance and employee job satisfaction

- The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in treating trauma

- The correlation between parenting styles and child behavior

- The effect of social media on political polarization

- The impact of foreign aid on economic development

- The relationship between workplace diversity and organizational performance

- The effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy in treating borderline personality disorder

- The correlation between childhood abuse and adult mental health outcomes

- The effect of sleep deprivation on cognitive function

- The impact of trade policies on international trade and economic growth

- The relationship between employee engagement and organizational commitment

- The effectiveness of cognitive therapy in treating postpartum depression

- The correlation between family meals and child obesity rates

- The effect of parental involvement in sports on child athletic performance

- The impact of social entrepreneurship on sustainable development

- The relationship between emotional labor and job burnout

- The effectiveness of art therapy in treating dementia

- The correlation between social media use and academic procrastination

- The effect of poverty on childhood educational attainment

- The impact of urban green spaces on mental health

- The relationship between job insecurity and employee well-being

- The effectiveness of virtual reality exposure therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between childhood trauma and substance abuse

- The effect of screen time on children’s social skills

- The impact of trade unions on employee job satisfaction

- The relationship between cultural intelligence and cross-cultural communication

- The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in treating chronic pain

- The correlation between childhood obesity and adult health outcomes

- The effect of gender diversity on corporate performance

- The impact of environmental regulations on industry competitiveness.

- The impact of renewable energy policies on greenhouse gas emissions

- The relationship between workplace diversity and team performance

- The effectiveness of group therapy in treating substance abuse

- The correlation between parental involvement and social skills in early childhood

- The effect of technology use on sleep patterns

- The impact of government regulations on small business growth

- The relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover

- The effectiveness of virtual reality therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic motivation in adolescents

- The effect of social media on political engagement

- The impact of urbanization on mental health

- The relationship between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust

- The correlation between early childhood education and social-emotional development

- The effect of screen time on cognitive development in young children

- The impact of trade policies on global economic growth

- The relationship between workplace diversity and innovation

- The effectiveness of family therapy in treating eating disorders

- The correlation between parental involvement and college persistence

- The effect of social media on body image and self-esteem

- The impact of environmental regulations on business competitiveness

- The relationship between job autonomy and job satisfaction

- The effectiveness of virtual reality therapy in treating phobias

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic achievement in college

- The effect of social media on sleep quality

- The impact of immigration policies on social integration

- The relationship between workplace diversity and employee well-being

- The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy in treating personality disorders

- The correlation between early childhood education and executive function skills

- The effect of parental involvement on STEM education outcomes

- The impact of trade policies on domestic employment rates

- The relationship between job insecurity and mental health

- The effectiveness of exposure therapy in treating PTSD

- The correlation between parental involvement and social mobility

- The effect of social media on intergroup relations

- The impact of urbanization on air pollution and respiratory health.

- The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership effectiveness

- The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in treating depression

- The correlation between early childhood education and language development

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in STEM fields

- The impact of trade policies on income inequality

- The relationship between workplace diversity and customer satisfaction

- The effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between parental involvement and civic engagement in adolescents

- The effect of social media on mental health among teenagers

- The impact of public transportation policies on traffic congestion

- The relationship between job stress and job performance

- The effectiveness of group therapy in treating depression

- The correlation between early childhood education and cognitive development

- The effect of parental involvement on academic motivation in college

- The impact of environmental regulations on energy consumption

- The relationship between workplace diversity and employee engagement

- The effectiveness of art therapy in treating PTSD

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in vocational education

- The effect of social media on academic achievement in college

- The impact of tax policies on economic growth

- The relationship between job flexibility and work-life balance

- The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between early childhood education and social competence

- The effect of parental involvement on career readiness in high school

- The impact of immigration policies on crime rates

- The relationship between workplace diversity and employee retention

- The effectiveness of play therapy in treating trauma

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in online learning

- The effect of social media on body dissatisfaction among women

- The impact of urbanization on public health infrastructure

- The relationship between job satisfaction and job performance

- The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy in treating PTSD

- The correlation between early childhood education and social skills in adolescence

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in the arts

- The impact of trade policies on foreign investment

- The relationship between workplace diversity and decision-making

- The effectiveness of exposure and response prevention therapy in treating OCD

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in special education

- The impact of zoning laws on affordable housing

- The relationship between job design and employee motivation

- The effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation therapy in treating traumatic brain injury

- The correlation between early childhood education and social-emotional learning

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in foreign language learning

- The impact of trade policies on the environment

- The relationship between workplace diversity and creativity

- The effectiveness of emotion-focused therapy in treating relationship problems

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in music education

- The effect of social media on interpersonal communication skills

- The impact of public health campaigns on health behaviors

- The relationship between job resources and job stress

- The effectiveness of equine therapy in treating substance abuse

- The correlation between early childhood education and self-regulation

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in physical education

- The impact of immigration policies on cultural assimilation

- The relationship between workplace diversity and conflict resolution

- The effectiveness of schema therapy in treating personality disorders

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in career and technical education

- The effect of social media on trust in government institutions

- The impact of urbanization on public transportation systems

- The relationship between job demands and job stress

- The correlation between early childhood education and executive functioning

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in computer science

- The effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy in treating PTSD

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in homeschooling

- The effect of social media on cyberbullying behavior

- The impact of urbanization on air quality

- The effectiveness of dance therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between early childhood education and math achievement

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in health education

- The impact of global warming on agriculture

- The effectiveness of narrative therapy in treating depression

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in character education

- The effect of social media on political participation

- The impact of technology on job displacement

- The relationship between job resources and job satisfaction

- The effectiveness of art therapy in treating addiction

- The correlation between early childhood education and reading comprehension

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in environmental education

- The impact of income inequality on social mobility

- The relationship between workplace diversity and organizational culture

- The effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in physical therapy education

- The effect of social media on misinformation

- The impact of green energy policies on economic growth

- The relationship between job demands and employee well-being

- The correlation between early childhood education and science achievement

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in religious education

- The impact of gender diversity on corporate governance

- The relationship between workplace diversity and ethical decision-making

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in dental hygiene education

- The effect of social media on self-esteem among adolescents

- The impact of renewable energy policies on energy security

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in social studies

- The impact of trade policies on job growth

- The relationship between workplace diversity and leadership styles

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in online vocational training

- The effect of social media on self-esteem among men

- The impact of urbanization on air pollution levels

- The effectiveness of music therapy in treating depression

- The correlation between early childhood education and math skills

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in language arts

- The impact of immigration policies on labor market outcomes

- The effectiveness of hypnotherapy in treating phobias

- The effect of social media on political engagement among young adults

- The impact of urbanization on access to green spaces

- The relationship between job crafting and job satisfaction

- The effectiveness of exposure therapy in treating specific phobias

- The correlation between early childhood education and spatial reasoning

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in business education

- The impact of trade policies on economic inequality

- The effectiveness of narrative therapy in treating PTSD

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in nursing education

- The effect of social media on sleep quality among adolescents

- The impact of urbanization on crime rates

- The relationship between job insecurity and turnover intentions

- The effectiveness of pet therapy in treating anxiety disorders

- The correlation between early childhood education and STEM skills

- The effect of parental involvement on academic achievement in culinary education

- The impact of immigration policies on housing affordability

- The relationship between workplace diversity and employee satisfaction

- The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in treating chronic pain

- The correlation between parental involvement and academic success in art education

- The effect of social media on academic procrastination among college students

- The impact of urbanization on public safety services.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

200+ Funny Research Topics

500+ Sports Research Topics

300+ American History Research Paper Topics

500+ Cyber Security Research Topics

500+ Environmental Research Topics

500+ Economics Research Topics

Principles of Sociological Inquiry

Chapter 9: interviews: qualitative and quantitative approaches, chapter 9 interviews: qualitative and quantitative approaches, why interview research.

Today’s young men are delaying their entry into adulthood. That’s a nice way of saying they are “totally confused”; “cannot commit to their relationships, work, or lives”; and are “obsessed with never wanting to grow up.” These quotes come from a summary of reviews on the website dedicated to Kimmel’s book, Guyland : http://www.guyland.net . But don’t take my word for it. Take sociologist Michael Kimmel’s word. He interviewed 400 young men, ages 16 to 26, over the course of 4 years across the United States to learn how they made the transition from adolescence into adulthood. Since the results of Kimmel’s research were published in 2008, Kimmel, M. (2008). Guyland: The perilous world where boys become men . New York, NY: Harper Collins. his book has made quite a splash. Featured in news reports, on blogs, and in many book reviews, some claim Kimmel’s research “could save the humanity of many young men,” This quote from Gloria Steinem is provided on the website dedicated to Kimmel’s book, Guyland : http://www.guyland.net . while others suggest that its conclusions can only be applied to “fraternity guys and jocks.” This quote comes from “Thomas,” who wrote a review of Kimmel’s book on the following site: http://yesmeansyesblog.wordpress.com/2010/03/12/review-guyland . Whatever your take on Kimmel’s research, one thing remains true: We surely would not know nearly as much as we now do about the lives of many young American men were it not for interview research.

9.1 Interview Research: What Is It and When Should It Be Used?

Learning objectives.

- Define interviews from the social scientific perspective.

- Identify when it is appropriate to employ interviews as a data-collection strategy.

Knowing how to create and conduct a good interview is one of those skills you just can’t go wrong having. Interviews are used by market researchers to learn how to sell their products, journalists use interviews to get information from a whole host of people from VIPs to random people on the street. Regis Philbin (a sociology major in college This information comes from the following list of famous sociology majors provided by the American Sociological Association on their website: http://www.asanet.org/students/famous.cfm . ) used interviews to help television viewers get to know guests on his show, employers use them to make decisions about job offers, and even Ruth Westheimer (the famous sex doctor who has an MA in sociology Read more about Dr. Ruth, her background, and her credentials at her website: http://www.drruth.com . ) used interviews to elicit details from call-in participants on her radio show. Interested in hearing Dr. Ruth’s interview style? There are a number of audio clips from her radio show, Sexually Speaking , linked from the following site: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~chuck/ruthpg . Warning: some of the images and audio clips on this page may be offensive to some readers. It seems everyone who’s anyone knows how to conduct an interview.

From the social scientific perspective, interviews A method of data collection that involves two or more people exchanging information through a series of questions and answers. are a method of data collection that involves two or more people exchanging information through a series of questions and answers. The questions are designed by a researcher to elicit information from interview participant(s) on a specific topic or set of topics. Typically interviews involve an in-person meeting between two people, an interviewer and an interviewee. But as you’ll discover in this chapter, interviews need not be limited to two people, nor must they occur in person.

The question of when to conduct an interview might be on your mind. Interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. They also have an advantage over surveys; with a survey, if a participant’s response sparks some follow-up question in your mind, you generally don’t have an opportunity to ask for more information. What you get is what you get. In an interview, however, because you are actually talking with your study participants in real time, you can ask that follow-up question. Thus interviews are a useful method to use when you want to know the story behind responses you might receive in a written survey.

Interviews are also useful when the topic you are studying is rather complex, when whatever you plan to ask requires lengthy explanation, or when your topic or answers to your questions may not be immediately clear to participants who may need some time or dialogue with others in order to work through their responses to your questions. Also, if your research topic is one about which people will likely have a lot to say or will want to provide some explanation or describe some process, interviews may be the best method for you. For example, I used interviews to gather data about how people reach the decision not to have children and how others in their lives have responded to that decision. To understand these “how’s” I needed to have some back-and-forth dialogue with respondents. When they begin to tell me their story, inevitably new questions that hadn’t occurred to me from prior interviews come up because each person’s story is unique. Also, because the process of choosing not to have children is complex for many people, describing that process by responding to closed-ended questions on a survey wouldn’t work particularly well.

In sum, interview research is especially useful when the following are true:

- You wish to gather very detailed information

- You anticipate wanting to ask respondents for more information about their responses

- You plan to ask questions that require lengthy explanation

- The topic you are studying is complex or may be confusing to respondents

- Your topic involves studying processes

Key Takeaways

- Understanding how to design and conduct interview research is a useful skill to have.

- In a social scientific interview, two or more people exchange information through a series of questions and answers.

- Interview research is often used when detailed information is required and when a researcher wishes to examine processes.

- Think about a topic about which you might wish to collect data by conducting interviews. What makes this topic suitable for interview research?

9.2 Qualitative Interview Techniques and Considerations

- Identify the primary aim of in-depth interviews.

- Describe what makes qualitative interview techniques unique.

- Define the term interview guide and describe how to construct an interview guide.

- Outline the guidelines for constructing good qualitative interview questions.

- Define the term focus group and identify one benefit of focus groups.

- Identify and describe the various stages of qualitative interview data analysis.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative interviews.

Qualitative interviews are sometimes called intensive or in-depth interviews A semistructured meeting between a researcher and respondent in which the researcher asks a series of open-ended questions; questions may be posed to respondents in slightly different ways or orders. . These interviews are semistructured; the researcher has a particular topic about which he or she would like to hear from the respondent, but questions are open ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each and every respondent. In in-depth interviews, the primary aim is to hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand and to hear it in their own words. In this section, we’ll take a look at how to conduct interviews that are specifically qualitative in nature, analyze qualitative interview data, and use some of the strengths and weaknesses of this method. In Section 9.4 “Issues to Consider for All Interview Types” , we return to several considerations that are relevant to both qualitative and quantitative interviewing.

Conducting Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative interviews might feel more like a conversation than an interview to respondents, but the researcher is in fact usually guiding the conversation with the goal in mind of gathering information from a respondent. A key difference between qualitative and quantitative interviewing is that qualitative interviews contain open-ended questions Questions for which a researcher does not provide answer options; questions that require respondents to answer in their own words. . The meaning of this term is of course implied by its name, but just so that we’re sure to be on the same page, I’ll tell you that open-ended questions are questions that a researcher poses but does not provide answer options for. Open-ended questions are more demanding of participants than closed-ended questions, for they require participants to come up with their own words, phrases, or sentences to respond.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher usually develops a guide in advance that he or she then refers to during the interview (or memorizes in advance of the interview). An interview guide A list of topics or questions that an interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview. is a list of topics or questions that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview. It is called a guide because it is simply that—it is used to guide the interviewer, but it is not set in stone. Think of an interview guide like your agenda for the day or your to-do list—both probably contain all the items you hope to check off or accomplish, though it probably won’t be the end of the world if you don’t accomplish everything on the list or if you don’t accomplish it in the exact order that you have it written down. Perhaps new events will come up that cause you to rearrange your schedule just a bit, or perhaps you simply won’t get to everything on the list.

Interview guides should outline issues that a researcher feels are likely to be important, but because participants are asked to provide answers in their own words, and to raise points that they believe are important, each interview is likely to flow a little differently. While the opening question in an in-depth interview may be the same across all interviews, from that point on what the participant says will shape how the interview proceeds. This, I believe, is what makes in-depth interviewing so exciting. It is also what makes in-depth interviewing rather challenging to conduct. It takes a skilled interviewer to be able to ask questions; actually listen to respondents; and pick up on cues about when to follow up, when to move on, and when to simply let the participant speak without guidance or interruption.

I’ve said that interview guides can list topics or questions. The specific format of an interview guide might depend on your style, experience, and comfort level as an interviewer or with your topic. I have conducted interviews using different kinds of guides. In my interviews of young people about their experiences with workplace sexual harassment, the guide I used was topic based. There were few specific questions contained in the guide. Instead, I had an outline of topics that I hoped to cover, listed in an order that I thought it might make sense to cover them, noted on a sheet of paper. That guide can be seen in Figure 9.4 “Interview Guide Displaying Topics Rather Than Questions” .

Figure 9.4 Interview Guide Displaying Topics Rather Than Questions

In my interviews with child-free adults, the interview guide contained questions rather than brief topics. One reason I took this approach is that this was a topic with which I had less familiarity than workplace sexual harassment. I’d been studying harassment for some time before I began those interviews, and I had already analyzed much quantitative survey data on the topic. When I began the child-free interviews, I was embarking on a research topic that was entirely new for me. I was also studying a topic about which I have strong personal feelings, and I wanted to be sure that I phrased my questions in a way that didn’t appear biased to respondents. To help ward off that possibility, I wrote down specific question wording in my interview guide. As I conducted more and more interviews, and read more and more of the literature on child-free adults, I became more confident about my ability to ask open-ended, nonbiased questions about the topic without the guide, but having some specific questions written down at the start of the data collection process certainly helped. The interview guide I used for the child-free project is displayed in Figure 9.5 “Interview Guide Displaying Questions Rather Than Topics” .

Figure 9.5 Interview Guide Displaying Questions Rather Than Topics

As you might have guessed, interview guides do not appear out of thin air. They are the result of thoughtful and careful work on the part of a researcher. As you can see in both of the preceding guides, the topics and questions have been organized thematically and in the order in which they are likely to proceed (though keep in mind that the flow of a qualitative interview is in part determined by what a respondent has to say). Sometimes qualitative interviewers may create two versions of the interview guide: one version contains a very brief outline of the interview, perhaps with just topic headings, and another version contains detailed questions underneath each topic heading. In this case, the researcher might use the very detailed guide to prepare and practice in advance of actually conducting interviews and then just bring the brief outline to the interview. Bringing an outline, as opposed to a very long list of detailed questions, to an interview encourages the researcher to actually listen to what a participant is telling her. An overly detailed interview guide will be difficult to navigate through during an interview and could give respondents the misimpression that the interviewer is more interested in her questions than in the participant’s answers.

When beginning to construct an interview guide, brainstorming is usually the first step. There are no rules at the brainstorming stage—simply list all the topics and questions that come to mind when you think about your research question. Once you’ve got a pretty good list, you can begin to pare it down by cutting questions and topics that seem redundant and group like questions and topics together. If you haven’t done so yet, you may also want to come up with question and topic headings for your grouped categories. You should also consult the scholarly literature to find out what kinds of questions other interviewers have asked in studies of similar topics. As with quantitative survey research, it is best not to place very sensitive or potentially controversial questions at the very beginning of your qualitative interview guide. You need to give participants the opportunity to warm up to the interview and to feel comfortable talking with you. Finally, get some feedback on your interview guide. Ask your friends, family members, and your professors for some guidance and suggestions once you’ve come up with what you think is a pretty strong guide. Chances are they’ll catch a few things you hadn’t noticed.

In terms of the specific questions you include on your guide, there are a few guidelines worth noting. First, try to avoid questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no, or if you do choose to include such questions, be sure to include follow-up questions. Remember, one of the benefits of qualitative interviews is that you can ask participants for more information—be sure to do so. While it is a good idea to ask follow-up questions, try to avoid asking “why” as your follow-up question, as this particular question can come off as confrontational, even if that is not how you intend it. Often people won’t know how to respond to “why,” perhaps because they don’t even know why themselves. Instead of “why,” I recommend that you say something like, “Could you tell me a little more about that?” This allows participants to explain themselves further without feeling that they’re being doubted or questioned in a hostile way.

Also, try to avoid phrasing your questions in a leading way. For example, rather than asking, “Don’t you think that most people who don’t want kids are selfish?” you could ask, “What comes to mind for you when you hear that someone doesn’t want kids?” Or rather than asking, “What do you think about juvenile delinquents who drink and drive?” you could ask, “How do you feel about underage drinking?” or “What do you think about drinking and driving?” Finally, as noted earlier in this section, remember to keep most, if not all, of your questions open ended. The key to a successful qualitative interview is giving participants the opportunity to share information in their own words and in their own way.

Even after the interview guide is constructed, the interviewer is not yet ready to begin conducting interviews. The researcher next has to decide how to collect and maintain the information that is provided by participants. It is probably most common for qualitative interviewers to take audio recordings of the interviews they conduct.

Recording interviews allows the researcher to focus on her or his interaction with the interview participant rather than being distracted by trying to take notes. Of course, not all participants will feel comfortable being recorded and sometimes even the interviewer may feel that the subject is so sensitive that recording would be inappropriate. If this is the case, it is up to the researcher to balance excellent note-taking with exceptional question asking and even better listening. I don’t think I can understate the difficulty of managing all these feats simultaneously. Whether you will be recording your interviews or not (and especially if not), practicing the interview in advance is crucial. Ideally, you’ll find a friend or two willing to participate in a couple of trial runs with you. Even better, you’ll find a friend or two who are similar in at least some ways to your sample. They can give you the best feedback on your questions and your interview demeanor.

All interviewers should be aware of, give some thought to, and plan for several additional factors, such as where to conduct an interview and how to make participants as comfortable as possible during an interview. Because these factors should be considered by both qualitative and quantitative interviewers, we will return to them in Section 9.4 “Issues to Consider for All Interview Types” after we’ve had a chance to look at some of the unique features of each approach to interviewing.

Although our focus here has been on interviews for which there is one interviewer and one respondent, this is certainly not the only way to conduct a qualitative interview. Sometimes there may be multiple respondents present, and occasionally more than one interviewer may be present as well. When multiple respondents participate in an interview at the same time, this is referred to as a focus group Multiple respondents participate in an interview at the same time. . Focus groups can be an excellent way to gather information because topics or questions that hadn’t occurred to the researcher may be brought up by other participants in the group. Having respondents talk with and ask questions of one another can be an excellent way of learning about a topic; not only might respondents ask questions that hadn’t occurred to the researcher, but the researcher can also learn from respondents’ body language around and interactions with one another. Of course, there are some unique ethical concerns associated with collecting data in a group setting. We’ll take a closer look at how focus groups work and describe some potential ethical concerns associated with them in Chapter 12 “Other Methods of Data Collection and Analysis” .

Analysis of Qualitative Interview Data

Analysis of qualitative interview data typically begins with a set of transcripts of the interviews conducted. Obtaining said transcripts requires having either taken exceptionally good notes during an interview or, preferably, recorded the interview and then transcribed it. Transcribing interviews is usually the first step toward analyzing qualitative interview data. To transcribe Creating a complete, written copy of a recorded interview by playing the recording back and typing in each word that is spoken on the recording, noting who spoke which words. an interview means that you create, or someone whom you’ve hired creates, a complete, written copy of the recorded interview by playing the recording back and typing in each word that is spoken on the recording, noting who spoke which words. In general, it is best to aim for a verbatim transcription, one that reports word for word exactly what was said in the recorded interview. If possible, it is also best to include nonverbals in an interview’s written transcription. Gestures made by respondents should be noted, as should the tone of voice and notes about when, where, and how spoken words may have been emphasized by respondents.

If you have the time (or if you lack the resources to hire others), I think it is best to transcribe your interviews yourself. I never cease to be amazed by the things I recall from an interview when I transcribe it myself. If the researcher who conducted the interview transcribes it himself or herself, that person will also be able to make a note of nonverbal behaviors and interactions that may be relevant to analysis but that could not be picked up by audio recording. I’ve seen interviewees roll their eyes, wipe tears from their face, and even make obscene gestures that spoke volumes about their feelings but that could not have been recorded had I not remembered to include these details in their transcribed interviews.

The goal of analysis The process of arriving at some inferences, lessons, or conclusions by condensing large amounts of data into relatively smaller bits of understandable information. is to reach some inferences, lessons, or conclusions by condensing large amounts of data into relatively smaller, more manageable bits of understandable information. Analysis of qualitative interview data often works inductively (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2006). For an additional reminder about what an inductive approach to analysis means, see Chapter 2 “Linking Methods With Theory” . If you would like to learn more about inductive qualitative data analysis, I recommend two titles: Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine; Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. To move from the specific observations an interviewer collects to identifying patterns across those observations, qualitative interviewers will often begin by reading through transcripts of their interviews and trying to identify codes. A code A shorthand representation of some more complex set of issues or ideas. is a shorthand representation of some more complex set of issues or ideas. In this usage, the word code is a noun. But it can also be a verb. The process of identifying codes in one’s qualitative data is often referred to as coding . Coding involves identifying themes across interview data by reading and rereading (and rereading again) interview transcripts until the researcher has a clear idea about what sorts of themes come up across the interviews.

Qualitative researcher and textbook author Kristin Esterberg (2002) Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. describes coding as a multistage process. Esterberg suggests that there are two types of coding: open coding and focused coding. To analyze qualitative interview data, one can begin by open coding The first stage of developing codes in qualitative data; involves reading data with an open mind and jotting down themes or categories that various bits of data seem to suggest. transcripts. This means that you read through each transcript, line by line, and make a note of whatever categories or themes seem to jump out to you. At this stage, it is important that you not let your original research question or expectations about what you think you might find cloud your ability to see categories or themes. It’s called open coding for a reason—keep an open mind. Open coding will probably require multiple go-rounds. As you read through your transcripts, it is likely that you’ll begin to see some commonalities across the categories or themes that you’ve jotted down. Once you do, you might begin focused coding.

Focused coding A later stage of developing codes in qualitative data; occurs after open coding and involves collapsing or narrowing themes and categories identified in open coding, succinctly naming them, describing them, and identifying passages of data that represent them. involves collapsing or narrowing themes and categories identified in open coding by reading through the notes you made while conducting open coding. Identify themes or categories that seem to be related, perhaps merging some. Then give each collapsed/merged theme or category a name (or code), and identify passages of data that fit each named category or theme. To identify passages of data that represent your emerging codes, you’ll need to read through your transcripts yet again (and probably again). You might also write up brief definitions or descriptions of each code. Defining codes is a way of making meaning of your data and of developing a way to talk about your findings and what your data mean. Guess what? You are officially analyzing data!

As tedious and laborious as it might seem to read through hundreds of pages of transcripts multiple times, sometimes getting started with the coding process is actually the hardest part. If you find yourself struggling to identify themes at the open coding stage, ask yourself some questions about your data. The answers should give you a clue about what sorts of themes or categories you are reading. In their text on analyzing qualitative data, Lofland and Lofland (1995) Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. H. (1995). Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis (3rd ed.) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. identify a set of questions that I find very useful when coding qualitative data. They suggest asking the following:

- Of what topic, unit, or aspect is this an instance?

- What question about a topic does this item of data suggest?

- What sort of answer to a question about a topic does this item of data suggest (i.e., what proposition is suggested)?

Asking yourself these questions about the passages of data that you’re reading can help you begin to identify and name potential themes and categories.

Still feeling uncertain about how this process works? Sometimes it helps to see how interview passages translate into codes. In Table 9.1 “Interview Coding Example” , I present two codes that emerged from the inductive analysis of transcripts from my interviews with child-free adults. I also include a brief description of each code and a few (of many) interview excerpts from which each code was developed.

Table 9.1 Interview Coding Example

As you might imagine, wading through all these data is quite a process. Just as quantitative researchers rely on the assistance of special computer programs designed to help with sorting through and analyzing their data, so, too, do qualitative researchers. Where quantitative researchers have SPSS and MicroCase (and many others), qualitative researchers have programs such as NVivo ( http://www.qsrinternational.com ) and Atlasti ( http://www.atlasti.com ). These are programs specifically designed to assist qualitative researchers with organizing, managing, sorting, and analyzing large amounts of qualitative data. The programs work by allowing researchers to import interview transcripts contained in an electronic file and then label or code passages, cut and paste passages, search for various words or phrases, and organize complex interrelationships among passages and codes.

In sum, the following excerpt, from a paper analyzing the workplace sexual harassment interview data I have mentioned previously, summarizes how the process of analyzing qualitative interview data often works:

All interviews were tape recorded and then transcribed and imported into the computer program NVivo. NVivo is designed to assist researchers with organizing, managing, interpreting, and analyzing non-numerical, qualitative data. Once the transcripts, ranging from 20 to 60 pages each, were imported into NVivo, we first coded the data according to the themes outlined in our interview guide. We then closely reviewed each transcript again, looking for common themes across interviews and coding like categories of data together. These passages, referred to as codes or “meaning units” (Weiss, 2004), Weiss, R. S. (2004). In their own words: Making the most of qualitative interviews. Contexts, 3 , 44–51. were then labeled and given a name intended to succinctly portray the themes present in the code. For this paper, we coded every quote that had something to do with the labeling of harassment. After reviewing passages within the “labeling” code, we placed quotes that seemed related together, creating several sub-codes. These sub-codes were named and are represented by the three subtitles within the findings section of this paper. Our three subcodes were the following: (a) “It’s different because you’re in high school”: Sociability and socialization at work; (b) Looking back: “It was sexual harassment; I just didn’t know it at the time”; and (c) Looking ahead: New images of self as worker and of workplace interactions. Once our sub-codes were labeled, we re-examined the interview transcripts, coding additional quotes that fit the theme of each sub-code. (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006) Blackstone, A., Houle, J., & Uggen, C. “At the time, I thought it was great”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Montreal, QC, August 2006. Currently under review.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Qualitative Interviews

As the preceding sections have suggested, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Whatever topic is of interest to the researcher employing this method can be explored in much more depth than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods such as survey research, but they also are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives rather than being asked to fit those perspectives into the perhaps limited response options provided by the researcher. And because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes, or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of qualitative interviews that occurs in person is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even her or his choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits do not come without some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall whatever details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviors are being asked about. As Esterberg (2002) puts it, “If you want to know about what people actually do, rather than what they say they do, you should probably use observation [instead of interviews].” Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Transcribing interviews is labor intensive—and that’s before coding even begins. It is also not uncommon to offer respondents some monetary incentive or thank-you for participating. Keep in mind that you are asking for more of participants’ time than if you’d simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labor intensive but also emotionally taxing. When I interviewed young workers about their sexual harassment experiences, I heard stories that were shocking, infuriating, and sad. Seeing and hearing the impact that harassment had had on respondents was difficult. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project should keep in mind their own abilities to hear stories that may be difficult to hear.

- In-depth interviews are semistructured interviews where the researcher has topics and questions in mind to ask, but questions are open ended and flow according to how the participant responds to each.

- Interview guides can vary in format but should contain some outline of the topics you hope to cover during the course of an interview.

- NVivo and Atlas.ti are computer programs that qualitative researchers use to help them with organizing, sorting, and analyzing their data.

- Qualitative interviews allow respondents to share information in their own words and are useful for gathering detailed information and understanding social processes.

- Drawbacks of qualitative interviews include reliance on respondents’ accuracy and their intensity in terms of time, expense, and possible emotional strain.

- Based on a research question you have identified through earlier exercises in this text, write a few open-ended questions you could ask were you to conduct in-depth interviews on the topic. Now critique your questions. Are any of them yes/no questions? Are any of them leading?

- Read the open-ended questions you just created, and answer them as though you were an interview participant. Were your questions easy to answer or fairly difficult? How did you feel talking about the topics you asked yourself to discuss? How might respondents feel talking about them?

9.3 Quantitative Interview Techniques and Considerations

- Define and describe standardized interviews.

- Describe how quantitative interviews differ from qualitative interviews.

- Describe the process and some of the drawbacks of telephone interviewing techniques.

- Describe how the analysis of quantitative interview works.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of quantitative interviews.

Quantitative interviews are similar to qualitative interviews in that they involve some researcher/respondent interaction. But the process of conducting and analyzing findings from quantitative interviews also differs in several ways from that of qualitative interviews. Each approach also comes with its own unique set of strengths and weaknesses. We’ll explore those differences here.

Conducting Quantitative Interviews

Much of what we learned in the previous chapter on survey research applies to quantitative interviews as well. In fact, quantitative interviews are sometimes referred to as survey interviews because they resemble survey-style question-and-answer formats. They might also be called standardized interviews Interviews during which the same questions are asked of every participant in the same way, and survey-style question-and-answer formats are utilized. . The difference between surveys and standardized interviews is that questions and answer options are read to respondents rather than having respondents complete a questionnaire on their own. As with questionnaires, the questions posed in a standardized interview tend to be closed ended. See Chapter 8 “Survey Research: A Quantitative Technique” for the definition of closed ended. There are instances in which a quantitative interviewer might pose a few open-ended questions as well. In these cases, the coding process works somewhat differently than coding in-depth interview data. We’ll describe this process in the following subsection.

In quantitative interviews, an interview schedule A document containing the list of questions and answer options that quantitative interviewers read to respondents. is used to guide the researcher as he or she poses questions and answer options to respondents. An interview schedule is usually more rigid than an interview guide. It contains the list of questions and answer options that the researcher will read to respondents. Whereas qualitative researchers emphasize respondents’ roles in helping to determine how an interview progresses, in a quantitative interview, consistency in the way that questions and answer options are presented is very important. The aim is to pose every question-and-answer option in the very same way to every respondent. This is done to minimize interviewer effect Occurs when an interviewee is influenced by how or when questions and answer options are presented by an interviewer. , or possible changes in the way an interviewee responds based on how or when questions and answer options are presented by the interviewer.

Quantitative interviews may be recorded, but because questions tend to be closed ended, taking notes during the interview is less disruptive than it can be during a qualitative interview. If a quantitative interview contains open-ended questions, however, recording the interview is advised. It may also be helpful to record quantitative interviews if a researcher wishes to assess possible interview effect. Noticeable differences in responses might be more attributable to interviewer effect than to any real respondent differences. Having a recording of the interview can help a researcher make such determinations.