What the Covid-19 Pandemic Revealed About Remote School

The unplanned experiment provided clear lessons on the value—and limitations—of online learning. Are educators listening?

Katherine Reynolds Lewis, Undark Magazine

:focal(512x344:513x345)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/d6/03d60640-f6dd-4840-984d-22d3f18f1d73/gettyimages-1282746597.jpg)

The transition to online learning in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic was, by many accounts, a failure. While there were some bright spots across the country, the transition was messy and uneven — countless teachers had neither the materials nor training they needed to effectively connect with students remotely, while many of those students were bored , isolated, and lacked the resources they needed to learn. The results were abysmal: low test scores, fewer children learning at grade level, increased inequity, and teacher burnout. With the public health crisis on top of deaths and job losses in many families, students experienced increases in depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Yet society very well may face new widespread calamities in the near future, from another pandemic to extreme weather, that will require a similarly quick shift to remote school. Success will hinge on big changes, from infrastructure to teacher training, several experts told Undark. “We absolutely need to invest in ways for schools to run continuously, to pick up where they left off. But man, it’s a tall order,” said Heather L. Schwartz, a senior policy researcher at RAND. “It’s not good enough for teachers to simply refer students to disconnected, stand-alone videos on, say, YouTube. Students need lessons that connect directly to what they were learning before school closed.”

More than three years after U.S. schools shifted to remote instruction on an emergency basis, the education sector is still largely unprepared for another long-term interruption of in-person school. The stakes are highest for those who need it most: low-income children and students of color, who are also most likely to be harmed in a future pandemic or live in communities most affected by climate change. But, given the abundance of research on what didn’t work during the pandemic, school leaders may have the opportunity to do things differently next time. Being ready would require strategic planning, rethinking the role of the teacher, and using new technology wisely, experts told Undark. And many problems with remote learning actually trace back not to technology, but to basic instructional quality. Effective remote learning won’t happen if schools aren’t already employing best practices in the physical classroom, such as creating a culture of learning from mistakes, empowering teachers to meet individual student needs, establishing high expectations, and setting clear goals supported by frequent feedback. While it’s ambitious to envision that every school district will create seamless virtual learning platforms — and, for that matter, overcome challenges in education more broadly — the lessons of the pandemic are there to be followed or ignored.

“We haven’t done anywhere near the amount of planning or the development of the instructional infrastructure needed to allow for a smooth transition next time schools need to close for prolonged periods of time,” Schwartz said. “Until we can reach that goal, I don’t have high confidence that the next prolonged school closure will be substantially more successful.”

Before the pandemic, only 3 percent of U.S. school districts offered virtual school, mostly for students with unique circumstances, such as a disability or those intensely pursuing a sport or the performing arts, according to a RAND survey Schwartz co-authored. For the most part, the educational technology companies and developers creating software for these schools promised to give students a personalized experience. But the research on these programs, which focused on virtual charter schools that only existed online, showed poor outcomes . Their students were a year behind in math and nearly a half-year behind in reading, and courses offered less direct time with a teacher each week than regular schools have in a day.

The pandemic sparked growth in stand-alone virtual academies, in addition to the emergency remote learning that districts had to adopt in March 2020. Educators’ interest in online instructional materials exploded, too, according to Schwartz, “and it really put the foot on the gas to ramp them up, expand them, and in theory, improve them.” By June 2021, the number of school districts with a stand-alone virtual school rose to 26 percent. Of the remaining districts, another 23 percent were interested in offering an online school, the report found.

But the sheer magnitude of options for online learning didn’t necessarily mean it worked well, Schwartz said: “It’s the quality part that has to come up in order for this to be a really good, viable alternative to in person instruction.” And individualized, self-directed online learning proved to be a pipe dream — especially for younger children who needed support from a parent or other family member even to get online, much less stay focused.

“The notion that students would have personalized playlists and could curate their own education was proven to be problematic on a couple levels, especially for younger and less affluent students,” said Thomas Toch, director of FutureEd, an education think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “The social and emotional toll that isolation and those traumas took on students suggest that the social dimension of schooling is hugely important and was greatly undervalued, especially by proponents for an increased role of technology.”

Students also often didn’t have the materials they needed for online school, some lacking computers or internet access at home. Teachers didn’t have the right training for online instruction , which has a unique pedagogy and best practices. As a result, many virtual classrooms attempted to replicate the same lessons over video that would’ve been delivered at school. The results were overwhelmingly bad, research shows. For example, a 2022 study found six consistent themes about how the pandemic affected learning, including a lack of interaction between students and with teachers, and disproportionate harm to low-income students. Numb from isolation and too many hours in front of a screen, students failed to engage in coursework and suffered emotionally .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/e1/05e16ea9-bd7f-4fbf-846e-177f05272f72/gettyimages-1229757662.jpg)

After some districts resumed in-person or hybrid instruction in the 2020 fall semester, it became clear that the longer students were remote, the worse their learning delays . For example, national standardized test scores for the 2020-2021 school year showed that passing rates for math declined about 14 percentage points on average, more than three times the drop seen in districts that returned to in-person instruction the earliest, according to a 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research study . Even after most U.S. districts resumed in-person instruction, students who had been online the longest continued to lag behind their peers. The pandemic hit cities hardest and the effects disproportionately harmed low-income children and students of color in urban areas.

“What we did during the pandemic is not the optimal use of online learning in education for the future,” said Ashley Jochim, a researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “Online learning is not a full stop substitute for what kids need to thrive and be supported at school.”

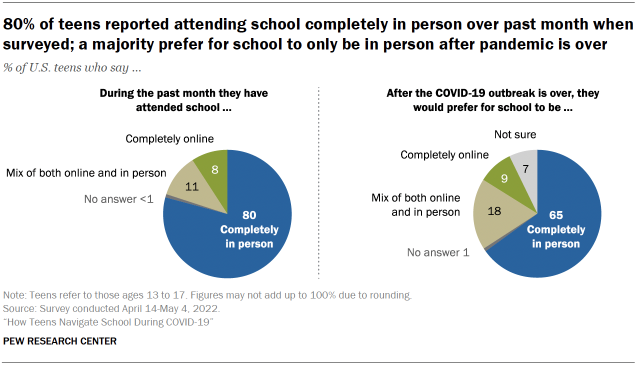

Children also largely prefer in-person school. A 2022 Pew Research Center survey suggested that 65 percent of students would rather be in a classroom, 9 percent would opt for online only, and the rest are unsure or prefer a hybrid model. “For most families and kids, full-time online school is actually not the educational solution they want,” Jochim said.

Virtual school felt meaningless to Abner Magdaleno, a 12th grader in Los Angeles. “I couldn’t really connect with it, because I’m more of, like, a social person. And that was stripped away from me when we went online,” recalled Magdaleno. Mackenzie Sheehy, 19, of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, found there were too many distractions at home to learn. Her grades suffered, and she missed the one-on-one time with teachers. (Sheehy graduated from high school in 2022.)

Many teachers feel the same way. “Nothing replaces physical proximity, whatever the age,” said Ana Silva, a New York City English teacher. She enjoyed experimenting with interactive technology during online school, but is grateful to be back in person. “I like the casual way kids can come to my desk and see me. I like the dynamism — seeing kids in the cafeteria. Those interactions are really positive, and they were entirely missing during the online learning.”

During the 2022-2023 school year, many districts initially planned to continue online courses for snow days and other building closures. But they found that the teacher instruction, student experience, and demands on families were simply too different for in-person versus remote school, said Liz Kolb, an associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. “Schools are moving away from that because it’s too difficult to quickly transition and blend back and forth among the two without having strong structures in place,” Kolb said. “Most schools don’t have those strong structures.”

In addition, both families and educators grew sick of their screens. “They’re trying to avoid technology a little bit. There’s this fatigue coming out of remote learning and the pandemic,” said Mingyu Feng, a research director at WestEd, a nonprofit research agency. “If the students are on Zoom every day for like, six hours, that seems to be not quite right.”

Despite the bumpy pandemic rollout, online school can serve an important role in the U.S. education system. For one, online learning is a better alternative for some students. Garvey Mortley, 15, of Bethesda, Maryland, and her two sisters all switched to their district’s virtual academy during the pandemic to protect their own health and their grandmother’s. This year, Mortley’s sisters went back to in-person school, but she chose to stay online. “I love the flexibility about it,” she said, noting that some of her classmates prefer it because they have a disability or have demanding schedules. “I love how I can just roll out of bed in the morning, and I can sit down and do school.” Some educators also prefer teaching online, according to reports of virtual schools that were inundated with applications from teachers because they wanted to keep working from home . Silva, the New York high school English teacher, enjoys online tutoring and academic coaching, because it facilitates one-on-one interaction.

And in rural districts and those with low enrollment, some access to online learning ensures students can take courses that could otherwise be inaccessible. “Because of the economies of scale in small rural districts, they needed to tap into online and shared service delivery arrangements in order to provide a full complement of coursework at the high school level,” said Jochim. Innovation in these districts, she added, will accelerate: “We’ll continue to see growth, scalability, and improvement in quality.”

There were also some schools that were largely successful at switching to online at the start of the pandemic, such as Vista Unified School District in California, which pooled and shared innovative ideas for adapting in March 2020; the school quickly put together an online portal so that principals and teachers could share ideas and the district could allot the necessary resources. Digging into examples like this could point the way to the future of online learning, said Chelsea Waite, a senior researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, who was part of a collaborative project studying 70 schools and districts that pivoted successfully to online learning. The project found three factors that made the transition work: a focus on resilience, collaboration, and autonomy for both students and educators; a healthy culture that prioritized relationships; and strong yet flexible systems that were accustomed to adaptation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/64/606453dd-d157-45da-a865-5161f95b6f08/gettyimages-1228656332.jpg)

“We investigated schools that did seem to be more prepared for the Covid disruption, not just with having devices in students’ hands or having an online curriculum already, but with a learning culture in the school that really prioritized agency and problem solving as skills for students and adults,” Waite said. “In these schools, kids are learning from a very young age to be a little bit more self-directed, to set goals, and pursue them and pivot when they need to.”

Similarly, many of the takeaways from the pandemic trace back to the basics of effective education, not technological innovation. A landmark report by the National Academies of Sciences called “How People Learn,” most recently updated in 2018, synthesized the body of educational research and identified four key features in the most successful learning environments. First, these schools are designed for, and adapt to, the specific students, building on what they bring to the classroom, such as skills and beliefs. Second, successful schools give their students clear goals, showing them what they need to learn and how they can get there. Third, they provide in-the-moment feedback that emphasizes understanding, not memorization. And finally, the most successful schools are community-centered, with a culture of collaboration and acceptance of mistakes.

“We as humans are social learners, yet some of the tech talk is driven by people who are strong individual learners,” said Jeremy Roschelle, executive director of Learning Sciences Research at Digital Promise, a global education nonprofit. “They’re not necessarily thinking about how most people learn, which is very social.”

Another powerful insight from pandemic-era remote schooling involves the evolving role of teachers, said Kim Kelly, a middle school math teacher at Northbridge Middle School in Massachusetts and a K-8 curriculum coach. Historically, a teacher’s role is the keeper of knowledge who delivers instruction. But in recent years, there has been a shift in approach, where teachers think of themselves as coaches who can intervene based on a student’s individual learning progress. Technology that assists with a coach-like role can be effective — but requires educators to be trained and comfortable interpreting data on student needs.

For example, with a digital learning platform called ASSISTments, teachers can assign math problems, students complete them — potentially receiving in-the-moment feedback on steps they’re getting wrong — and then the teachers can use data from individual students and the entire class to plan instruction and see where additional support is needed.

“A big advantage of these computer-driven products is they really try to diagnose where students are, and try to address their needs. It’s very personalized, individualized,” said WestEd’s Feng, who has evaluated ASSISTments and other educational technologies. She noted that some teachers feel frustrated “when you expect them to read the data and try to figure out what the students’ needs are.”

Teacher’s colleges don’t typically prepare educators to interpret data and change their practices, said Kelly, whose dissertation focused on self-regulated online learning. But professional development has helped her learn to harness technology to improve teaching and learning. “Schools are in data overload; we are oozing data from every direction, yet none of it is very actionable,” she said. Some technology, she added, provided student data that she could use regularly, which changed how she taught and assigned homework.

When students get feedback from the computer program during a homework session, the whole class doesn’t have to review the homework together, which can save time. Educators can move forward on instruction — or if they see areas of confusion, focus more on those topics. The ability of the programs to detect how well students are learning “is unreal,” said Kelly, “but it really does require teachers to be monitoring that data and interpreting.” She learned to accept that some students could drive their own learning and act on the feedback from homework, while others simply needed more teacher intervention. She now does more assessment at the beginning of a course to better support all students.

At the district or even national level, letting teachers play to their strengths can also help improve how their students learn, Toch, of FutureEd, said. For example, if a teacher is better at delivering instruction, they could give a lesson to a larger group of students online, while another teacher who is more comfortable in the coach role could work in smaller groups or one-on-one.

“One thing we saw during the pandemic are smart strategies for using technology to get outstanding teachers in front of more students,” Toch said, describing one effort that recruited exceptional teachers nationally and built a strong curriculum to be delivered online. “The local educators were providing support for their students in their classrooms.”

Remote schooling requires new technology, and already, educators are swamped with competing platforms and software choices — most of which have insufficient evidence of efficacy . Traditional independent research on specific technologies is sparse, Roschelle said. Post-pandemic, the field is so diverse and there are so many technologies in use, it’s almost impossible to find a control group to design a randomized control trial, he added. However, there is qualitative research and evidence that give hints about the quality of technology and online learning, such as case studies and school recommendations.

Educational leaders should ask three key questions about technology before investing, recommended Ryan Baker, a professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania: Is there evidence it works to improve learning outcomes? Does the vendor provide support and training, or are teachers on their own? And does it work with the same types of students as are in their school or district? In other words, educators must look at a technology’s track record in the context of their own school’s demographics, geography, culture, and challenges. These decisions are complicated by the small universe of researchers and evaluators, who have many overlapping relationships. (Over his career, for example, Baker has worked with or consulted for many of the education technology firms that create the software he studies.)

It may help to broaden the definition of evidence. The Center on Reinventing Public Education launched the Canopy project to collect examples of effective educational innovation around the U.S.

“What we wanted to do is build much better and more open and collective knowledge about where schools are challenging old assumptions and redesigning what school is and should be,” she added, noting that these educational leaders are reconceptualizing the skills they want students to attain. “They’re often trying to measure or communicate concepts that we don’t have great measurement tools for yet. So they end up relying on a lot of testimonials and evidence of student work.”

The moment is ripe for innovation in online and in-person education, said Julia Fallon, executive director of the State Educational Technology Directors Association, since the pandemic accelerated the rollout of devices and needed infrastructure. There’s an opportunity and need for technology that empowers teachers to improve learning outcomes and work more efficiently, said Roschelle. Online and hybrid learning are clearly here to stay — and likely will be called upon again during future temporary school closures.

Still, poorly-executed remote learning risks tainting the whole model; parents and students may be unlikely to give it a second chance. The pandemic showed the hard and fast limits on the potential for fully remote learning to be adopted broadly, for one, because in many communities, schools serve more than an educational function — they support children’s mental health, social needs, and nutrition and other physical health needs. The pandemic also highlighted the real challenge in training the entire U.S. teaching corps to be proficient in technology and data analysis. And the lack of a nimble shift to remote learning in an emergency will disproportionately harm low-income children and students of color. So the stakes are high for getting it right, experts told Undark, and summoning the political will.

“There are these benefits in online education, but there are also these real weaknesses we know from prior research and experience,” Jochim said. “So how do we build a system that has online learning as a complement to this other set of supports and experiences that kids benefit from?”

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning journalist covering children, race, gender, disability, mental health, social justice, and science.

This article was originally published on Undark . Read the original article .

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

How is the digital divide is affecting U.S. students’ homework?

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Image: Erin Clark/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Katherine Schaeffer

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Research carried out by Pew Research Center highlights how a lack of internet connectivity and digital skills negatively affected K-12 students' ability to complete school work at home.

- Research shows these problems were faced by families of different incomes, race and location.

- One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often.

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time – an experience often called the “ homework gap ” – may continue to feel the effects this school year.

Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found about the students most likely to be affected by the homework gap and their experiences learning from home.

Around nine-in-ten U.S. parents with K-12 children at home (93%) said their children have had some online instruction since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, and 30% of these parents said it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet as an educational tool, according to an April 2021 Pew Research Center survey .

Gaps existed for certain groups of parents. For example, parents with lower and middle incomes (36% and 29%, respectively) were more likely to report that this was very or somewhat difficult, compared with just 18% of parents with higher incomes.

This challenge was also prevalent for parents in certain types of communities – 39% of rural residents and 33% of urban residents said they have had at least some difficulty, compared with 23% of suburban residents.

Around a third of parents with children whose schools were closed during the pandemic (34%) said that their child encountered at least one technology-related obstacle to completing their schoolwork during that time. In the April 2021 survey, the Center asked parents of K-12 children whose schools had closed at some point about whether their children had faced three technology-related obstacles. Around a quarter of parents (27%) said their children had to do schoolwork on a cellphone, 16% said their child was unable to complete schoolwork because of a lack of computer access at home, and another 14% said their child had to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

Parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed amid COVID-19 were more likely to say their children faced technology-related obstacles while learning from home. Nearly half of these parents (46%) said their child faced at least one of the three obstacles to learning asked about in the survey, compared with 31% of parents with midrange incomes and 18% of parents with higher incomes.

Of the three obstacles asked about in the survey, parents with lower incomes were most likely to say that their child had to do their schoolwork on a cellphone (37%). About a quarter said their child was unable to complete their schoolwork because they did not have computer access at home (25%), or that they had to use public Wi-Fi because they did not have a reliable internet connection at home (23%).

A Center survey conducted in April 2020 found that, at that time, 59% of parents with lower incomes who had children engaged in remote learning said their children would likely face at least one of the obstacles asked about in the 2021 survey.

A year into the outbreak, an increasing share of U.S. adults said that K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork at home during the pandemic. About half of all adults (49%) said this in the spring 2021 survey, up 12 percentage points from a year earlier. An additional 37% of adults said that schools should provide these resources only to students whose families cannot afford them, and just 13% said schools do not have this responsibility.

Even before the pandemic, Black teens and those living in lower-income households were more likely than other groups to report trouble completing homework assignments because they did not have reliable technology access. Nearly one-in-five teens ages 13 to 17 (17%) said they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, a 2018 Center survey of U.S. teens found.

One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often. Just 4% of White teens and 6% of Hispanic teens said this often happened to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in the survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

A wide gap also existed by income level: 24% of teens whose annual family income was less than $30,000 said the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibited them from finishing their homework, but that share dropped to 9% among teens who lived in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How universities can use blockchain to transform research

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

Empowering women in STEM: How we break barriers from classroom to C-suite

Genesis Elhussein and Julia Hakspiel

March 1, 2024

Why we need education built for peace – especially in times of war

February 28, 2024

These 5 key trends will shape the EdTech market upto 2030

Malvika Bhagwat

February 26, 2024

With Generative AI we can reimagine education — and the sky is the limit

Oguz A. Acar

February 19, 2024

How UNESCO is trying to plug the data gap in global education

February 12, 2024

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

How teens navigate school during covid-19, a majority of teens prefer in-person over virtual or hybrid learning. hispanic and lower-income teens are particularly likely to fear they’ve fallen behind in school due to covid-19 disruptions.

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand teens’ and parents’ experiences with schooling, virtual learning and the digital divide amid the coronavirus pandemic. For this analysis, we surveyed 1,316 pairs of U.S. teens and their parents – one parent and one teen from each household. The survey was conducted online by Ipsos from April 14 to May 4, 2022.

Ipsos invited one parent from each of a representative set of households with parents of teens in the desired age range from its KnowledgePanel, a probability-based web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses, to take this survey. For some of these questions, parents were asked to think about one teen in their household (if there were multiple teens ages 13 to 17 in the household, one was randomly chosen). At the conclusion of the parent’s section, the parent was asked to have this chosen teen come to the computer and complete the survey in private.

The survey is weighted to be representative of two different populations: 1) parents with teens ages 13 to 17 and 2) teens ages 13 to 17 who live with parents. For each of these populations, the survey is weighted to be representative by age, gender, race, ethnicity, household income and other categories.

Here are the questions used for this report , along with responses, and its methodology .

More than two years after the COVID-19 outbreak forced school officials to shift classes and assignments online, teens continue to navigate the pandemic’s impact on their education and relationships, even while they experience glimpses of normalcy as they return to the classroom.

Eight-in-ten U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 say they attended school completely in person over the past month, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted April 14-May 4. Fewer teens say they attended school completely online (8%) or did so through a mix of both online and in-person instruction (11%) in the month prior to taking the survey.

When it comes to the type of learning environment youths prefer, teens strongly favor in-person over remote or hybrid learning. Fully 65% of teens say they would prefer school to be completely in person after the COVID-19 outbreak is over, while a much smaller share (9%) would opt for a completely online environment. Another 18% say they prefer a mix of both online and in-person instruction, while 7% are not sure of their preferred type of schooling after the pandemic.

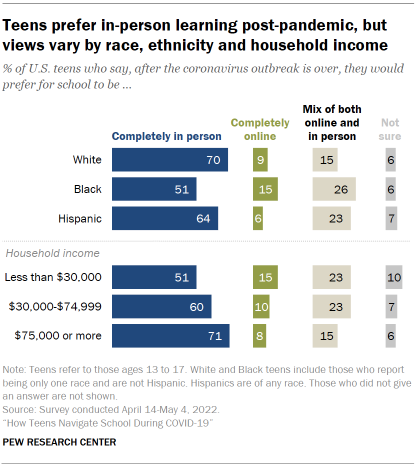

Across major demographic groups, teens favor attending school completely in person over other options. Still there are some differences that emerge by race and ethnicity and household income.

While 70% of White teens and 64% of Hispanic teens say they would prefer for school to be completely in person after the COVID-19 outbreak is over, that share drops to 51% among Black teens. At the same time, Black or Hispanic teens are more likely than White teens to prefer a mix of both online and in-person instruction post-pandemic.

In addition, 71% of teens living in higher-income households earning $75,000 or more a year report they prefer for school to be completely in person after the pandemic is over. That share drops to six-in-ten or less among those whose annual family income is less than $75,000. Preference for hybrid schooling is also more common among teens living in households earning less than $75,000 a year than among teens in households earning more.

Teens and parents express their views about virtual learning and the pandemic’s impact on educational achievement

From declining test scores to widening achievement gaps , teachers, parents and advocates have raised concerns about the negative impact the pandemic may have had on students. Beyond academic woes, experts also warn that these disruptions could have lingering effects on young people’s mental and emotional well-being.

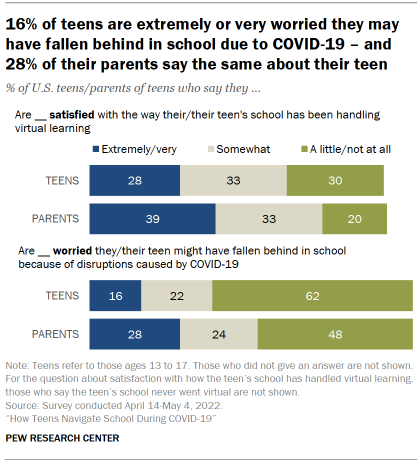

Teens hold mixed views of how their schools tackled remote schooling. Some 28% of teens say they are extremely or very satisfied with the way their school has handled virtual learning, while a similar share report being only a little or not at all satisfied with their school’s performance. Some teens fall in the middle of the spectrum, with 33% saying they are somewhat satisfied with this. (Another 9% state their school has not had virtual learning.)

In addition to having teens weigh in on these subjects, the Center also asked parents of these same teens about their child’s experience with school during the pandemic. The survey finds that parents, too, hold somewhat divided views on remote learning, though they offer a somewhat more positive assessment than their children. About four-in-ten parents of teens (39%) say they are extremely or very satisfied with the way their child’s school has handled virtual learning; 33% say they are somewhat satisfied about this, while 20% report being only a little or not at all satisfied by this.

When asked about the effect COVID-19 may have had on their schooling, a majority of teens express little to no concern about falling behind in school due to disruptions caused by the outbreak. Still, there are youth who worry the pandemic has hurt them academically: 16% of teens say they are extremely or very worried they may have fallen behind in school because of COVID-19-related disturbances.

Parents tend to express more concern than their children. Roughly three-in-ten parents report they are extremely (12%) or very (16%) worried their teen may have fallen behind in school due to the pandemic.

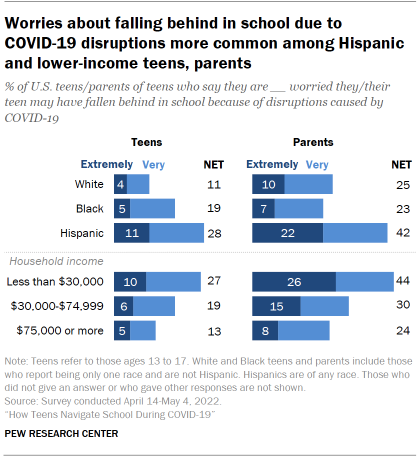

The level of concern about falling behind in school varies by race and ethnicity – for both teens and their parents.

Roughly three-in-ten Hispanic teens (28%) say they are extremely or very worried they may have fallen behind in school because of disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak, compared with 19% of Black teens and 11% of White teens. 1 This pattern is present among parents as well. Hispanic parents (42%) are more likely than their White (25%) or Black counterparts (23%) to report being extremely or very worried their teen may have fallen behind in school during this time.

Teens and parents from lower-income households are also more likely to express concern about the pandemic’s negative impact on schooling. For example, 44% of parents living in households earning less than $30,000 a year say they are extremely or very worried their teen has fallen behind in school because of COVID-19 disruptions, but this falls to 24% among those whose annual household income is $75,000 or more. Teens from households making less than $75,000 annually are also more likely than those from households with higher incomes to express concern about falling behind in school.

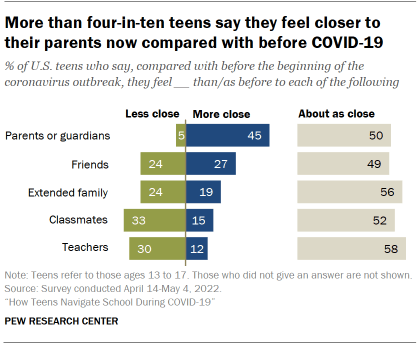

More than four-in-ten teens report feeling closer to their parents or guardians since the start of the pandemic

With recent research pointing to the negative impacts the coronavirus outbreak has had on adolescents’ social connections, teens were asked to share how their relationships may have changed since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Some 45% of teens say they feel more close to their parents or guardians compared with before the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak. A smaller share says the same for their friends, extended family, classmates or teachers.

At the same time, some teens express feeling less connected to certain groups. Roughly one-third say they feel less close to classmates (33%) or teachers (30%), while 24% each feel this way about their friends or extended family. Just 5% of teens say they feel less close to their parents or guardians than they did before the pandemic.

Still, the most common responses to these questions hint at social stability. Roughly half or more teens say they are about as close to their friends, parents or guardians, classmates, extended family or teachers as they were before the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Teens’ views about how their relationships may have evolved during the pandemic share similar sentiments across many of the demographic groups explored in the study. There are, however, some modest differences by race and ethnicity. For example, Hispanic and Black teens are more likely than White teens to say they feel less close to their friends than before the pandemic.

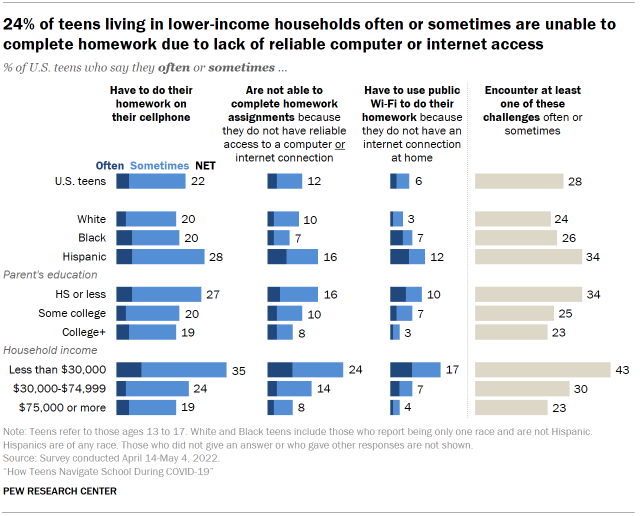

About three-in-ten teens face at least one challenge related to the ‘homework gap’

Even prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, some teens faced problems completing their homework because they lacked a computer or internet access at home – a phenomenon often referred to as the “ homework gap .” And as students pivoted to virtual learning , and later shifted between online and in-person classes, access to technology and reliable internet connectivity continued to be crucial to student success.

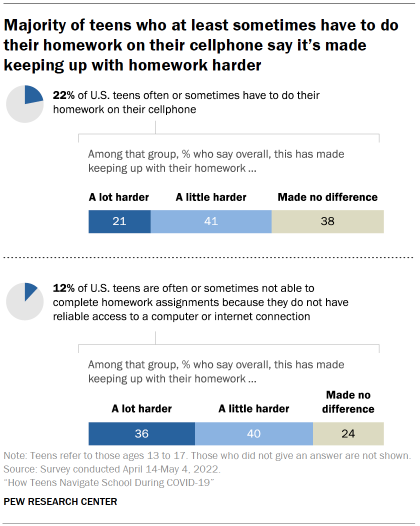

The new survey reveals some teens – especially those from less affluent households – face digital challenges to completing their schoolwork. About one-in-five teens (22%) say they often or sometimes have to do their homework on a cellphone. Some 12% say they at least sometimes are not able to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, while 6% say they have to use public Wi-Fi to do their homework at least sometimes because they do not have an internet connection at home. (Respondents were not specifically asked to think about the pandemic when asked these questions.)

Some 24% of teens who live in a household making less than $30,000 a year say they at least sometimes are not able to complete their homework because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, compared with 14% of those in a household making $30,000 to $74,999, and 8% of those in a household making $75,000 or more. Teens whose parent reports an annual income of less than $30,000 are also more likely to say they often or sometimes have to do homework on a cellphone or use public Wi-Fi for homework, compared with those living in higher-earning households.

There are similar patterns by parental education: Larger shares of teens whose parent has a high school diploma or less say they at least sometimes face each of the three challenges the survey asked about, compared with those whose parent has a bachelor’s or advanced degree.

When it comes to racial and ethnic differences, Hispanic teens are more likely than both Black and White teens to say they at least sometimes are not able to complete homework because they lack reliable computer or internet access, and they are more likely than White teens to say the same about having to do their homework on a cellphone or using public Wi-Fi for homework. Black and White teens are equally likely to report at least sometimes experiencing each of the three problems the survey covered.

All told, 28% of teens experience at least one of these three homework-related challenges often or sometimes. Some 43% of teens living in a household with an annual income of less than $30,000 report at least sometimes facing one or more of these challenges to completing homework – about twice the share of teens from households making $75,000 or more annually and 13 percentage points higher than the share of teens in a household making $30,000 to $74,999 annually who say so. And 34% of Hispanic teens have experienced the same – 10 points higher than the share of White teens who have experienced at least one of these challenges at least sometimes, but statistically equivalent to the share of Black teens who report this.

For some youth, these challenges have made it harder to keep up with their homework. Among those who have not been able to complete homework often or sometimes due to lack of reliable computer or internet access, 36% say it has made keeping up with their homework a lot harder. About one-in-five of those who at least sometimes have to do homework on their cellphone say the same.

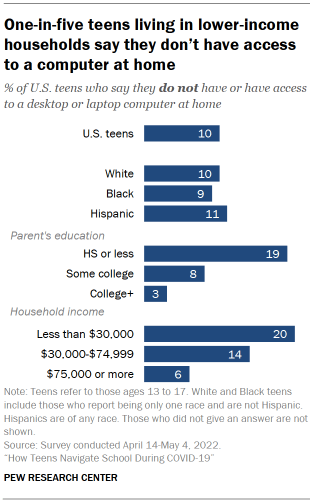

Teen computer access at home differs by parent’s level of education, household income

While most teens say they have a home computer, there are some – particularly those living in households with lower incomes or whose parent has a high school education or less – who do not have this technology at home. One-in-ten teens report not having access to a desktop or laptop computer at home.

This rises to one-in-five for those living in a household with an annual income of less than $30,000, and to a similar share (19%) for teens whose parent has a high school diploma or less formal education.

- There were not enough Asian American respondents in the sample to be broken out into a separate analysis. As always, their responses are incorporated into the general population figures throughout the report. ↩

- A 2018 Center survey also asked U.S. teens about technology challenges related to the homework gap. Due to differences in the ways that survey was conducted versus this analysis, direct comparisons cannot be made across the two surveys to understand change over time. Still, there are common patterns between the two separate surveys; for example, teens living in lower-income households are more likely to experience homework gap-related problems than those in higher-income households. ↩

Sign up for our Internet, Science and Tech newsletter

New findings, delivered monthly

Report Materials

Table of contents, connection, creativity and drama: teen life on social media in 2022, more so than adults, u.s. teens value people feeling safe online over being able to speak freely, teens, social media and technology 2022, u.s. teens are more likely than adults to support the black lives matter movement, digital readiness gaps, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Student Engagement

How has the pandemic changed the way educators think about homework, by daniel lempres jan 19, 2022.

Alex Rockheart / Shutterstock

This article is part of the guide: Voices of Change.

Ray Salazar has been teaching high school Journalism and English in Chicago Public Schools for over twenty years. He usually begins the academic year with lessons on written profiles, but in the fall of 2020, he felt that wouldn’t meet the moment. Instead, he crafted an entirely new curriculum that he felt would better resonate with students, a series of reading and writing assignments that looked at the stages of grief.

“I think that now more than ever we need to make sure that whatever we’re teaching has some relevance to the real world,” Salazar said. “It doesn’t mean that everything has to be connected to the pandemic, but students have to be able to find meaning in what they’re doing.”

Salazar used to craft assignments as preparation for upcoming classes, but he noticed the pandemic has made it more difficult for many students to get their work done. So he made a small adjustment: He stopped tying class discussions to the previous night’s homework. “That just decreases the chances of them engaging in the next class,” he says.

Salazar is part of a growing movement of educators rethinking homework in light of the pandemic. The heightened stress of COVID-19 has led many teachers to think more critically about their impact on students’ mental wellbeing, and districts around the country are turning toward social-emotional learning as a way to nurture and better support students during this time of isolation and increased anxiety. The pandemic has also reignited a debate that teachers and academics have struggled with for decades: What is the most effective strategy for assigning and grading homework?

Studies show that the pandemic caused a drop in test scores in reading and math, with the students who were already struggling showing the largest declines . But educators disagree about how they should respond. According to a study conducted by Challenge Success, a school reform nonprofit, high school students are already doing more homework than they were before the pandemic, averaging 3 hours of homework a night, up from 2.7 hours before the pandemic. Over 40 percent of students report that they’re sleeping less, and close to 3 in 5 students say they’re more stressed about school than they were before.

Supporters say homework is necessary to reinforce what happens in the classroom. Homework helps build certain life skills like organization, perseverance and problem-solving. It also gives parents a chance to be involved in their child’s education. But other educators have a different view. They say students need time to exercise, socialize and recharge. They cite homework’s impact on the achievement gap between students of differing socioeconomic backgrounds. Assignments requiring online access have become ubiquitous over the last decade, and according to one Pew survey , close to one in five teenagers reported that unreliable access to a computer or internet connection interfered with their schoolwork even before the pandemic. School districts and educators have responded in a variety of ways.

The pandemic has led to what are akin to “triaging decisions,” says Andrew Maxey, director of strategic initiatives for Tuscaloosa City Schools in Alabama. Maxey has spent over two decades in public education, both in the classroom and at the administrative level. He spearheads the Alabama Conference on Grading and Assessment in Learning , an annual event where educators discuss best practices for testing and grading students.

Many educators have been in “survival mode,” Maxey says. They’re providing additional flexibility, assigning and grading less homework in light of the pandemic.

“Some of those things are a really solid practices that because we’ve made them in the context of a pandemic, we’re setting ourselves up to not come back to them when we’re through this experience,” he adds.

Giving Students Choices

Because independent schools have more flexibility, some were able to take a more innovative approach, says Denise Pope, a professor of education at Stanford University and co-founder of Challenge Success. “Some of these independent schools had kids online during normal school hours,” Pope says. “But you won’t have to do homework after 3 o’clock.” Other schools saw having kids in remote class all day wasn’t feasible. These teachers would hold an optional session akin to office hours for students to ask questions and get extra help. Her research has found that both of these strategies were more effective than an entire day of remote classes followed by traditional homework.

Some school districts in California are doing away with failing grades, choosing instead to give students an opportunity to retake tests or resubmit assignments. A proposal under review in Arlington County, Va., suggests no longer grading homework at all, leaning instead on assessments, while elementary schools across the country have moved away from homework entirely, citing numerous studies that reflect little to no benefit for younger students. (Research does reflect a benefit for older students, but that research wasn’t carried out during extended periods of remote learning, says Pope.)

Perhaps greater than the crisis of lower test scores, Pope says, is the epidemic of disengagement educators are seeing. She said the pandemic has caused many students to simply check out. “Once the light of learning goes off in their eyes,” she says, “It’s really hard to get it back on.”

Half of students reported spending more time on schoolwork during the pandemic, but over 40 percent also reported putting less effort into that work, and feeling less engaged, according to the Challenge Success study. This worries Pope, because engagement with learning is closely tied to academic achievement and mental wellbeing. “It’s disheartening,” she says. “The idea that kids are just going through the motions, not really finding it cognitively engaging.”

In his classroom, Ray Salazar now tries to assign less homework, and assign things that give students choices. “Homework should make them feel like they have some power over their learning,” he says.

He doesn’t think pushing students harder will repair the damage of the pandemic, and says it’s wrong to compare students to pre-pandemic test scores. To that end, the focus on learning loss might not benefit students, especially students of color. “I don’t believe in talking about how we’re behind. We are where we are,” he said. “The world has shifted.” He says telling students they’re behind is counterproductive. “Sometimes we just have to say, ‘we’re doing enough.’”

This story is part of an EdSurge Research series chronicling diverse educator experiences. These stories are made publicly available with support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative . EdSurge maintains editorial control over all content. (Read our ethics statement here .) This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 .

Daniel is a freelance reporter and researcher based in Oakland, Calif.

Voices of Change

Indigenous Knowledge Is Often Overlooked in Education. But It Has A Lot to Teach Us.

By helen thomas.

The Pandemic Left Us Looking for Answers. We Found Them in Our Alternative Education Model.

By christopher hoang.

I Wanted Balance Between My Career and Personal Life. Now, I Sing A Different Tune.

By deitra colquitt.

Students Are Suffering From Low Academic Self-Esteem. Democratizing the Classroom Can Save Them.

By nikki glenn, more from edsurge.

To Make Assignments More Meaningful, I’m Giving Students a More Authentic Audience

By jonathan lancaster.

Playful Pedagogy: Gamer Types and Board Games for Inclusive Learning

By scott beiter.

As a Principal, I Thought I Promoted Psychological Safety. Then a Colleague Spoke Up.

By damen scott.

Education Workforce

Teacher layoffs are coming as pandemic relief money for schools dries up, by nadia tamez-robledo.

Journalism that ignites your curiosity about education.

EdSurge is an editorially independent project of and

- Product Index

- Write for us

- Advertising

FOLLOW EDSURGE

© 2024 All Rights Reserved

COMMENTS

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, she found that homework usually does more harm than good, she says. For one thing, students list it among the top three stressors in their lives. For another, research shows homework—except for independent reading of books that students choose—doesn’t correlate with student success.

The transition to online learning in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic was, by many accounts, a failure. ... When students get feedback from the computer program during a homework ...

Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found about the students most likely to be affected by the homework gap and their experiences learning from home. 1. Around nine-in-ten U.S. parents with K-12 children at home (93%) said their children have had some online instruction since the coronavirus outbreakbegan in February 2020, and 30% of these ...

Fully 65% of teens say they would prefer school to be completely in person after the COVID-19 outbreak is over, while a much smaller share (9%) would opt for a completely online environment. Another 18% say they prefer a mix of both online and in-person instruction, while 7% are not sure of their preferred type of schooling after the pandemic.

But educators disagree about how they should respond. According to a study conducted by Challenge Success, a school reform nonprofit, high school students are already doing more homework than they were before the pandemic, averaging 3 hours of homework a night, up from 2.7 hours before the pandemic. Over 40 percent of students report that they ...