Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

How To Write A Presidential Speech

Katie Clower

The Importance of a Presidential Speech

Presidential speeches have been a prevalent and important part of our country’s society and culture since Washington’s inauguration in April of 1789 in which the first inaugural address, and presidential speech in general, was delivered. Since then, we as a country have beared witness to countless presidential and political speeches. Some have been moving, some inspirational and motivating, some heartbreaking and tear-jerking. Others have made us cringe out of anger, fear, or disappointment. Some have simply fallen flat, having been described as boring or awkward or unsettling.

Many presidential speeches are remembered and regarded to this day, despite how many decades or centuries ago they were delivered. Often, we remember and reflect on those which were the most special and important. But, in some cases the horribly written or delivered ones stick out in our minds, too. This writing guide is designed, in part, for those presidential or politician candidates and hopefuls to use as a tool to ensure their own speeches will be remembered and reflected on for years to come, for their positive messages and audience responses, not the opposite.

If you are not or do not plan to be a politician or president, do not stop reading! This guide is also written with the average person, even one with little to no political ties or aspirations, in mind. Public speech is a large aspect and topic of discussion in our society, one that has become critical to the presidential process. As such, many of us may be fascinated by and curious about the process of constructing and delivering a successful presidential speech. This guide will convey all of this information via data and analyses of previous both renowned and failed presidential speeches, deductions of what it was that made them so great or so catastrophic, syntheses of expert research and findings on the topic, and more. It does so in a casual, easy-to-follow tone, further making it a read for all.

Another reason this guide is applicable to everyone is because the speech-making tips and techniques shared throughout the text are true for not just political speech, but any form. Everyone has to deliver pitches, speeches, or presentations at some point in their lives or careers. The conclusion section emphasizes how the information and advice shared in this guide can apply to and help with all other forms of speech writing and delivering. With all of this in mind, this guide is meant for truly anyone who wants to take the time to read and be informed.

Goals of the Speech

Presidential speeches have become increasingly important over time as a means to connect with and appeal to the people in order to articulate and drive forward presidential goals, deliver or reflect on tragic or positive news, and more. As Teten put it in his study, “speeches are the core of the modern presidency” (334). He finds that while “in the past, speechmaking, as well as public appeal in the content of speeches, was not only infrequent but discouraged due to precedent and technology,” today it is one of the most important and most frequently utilized presidential tools (Teten, 334). Allison Mcnearney states that “even in an age of Twitter, the formal, spoken word from the White House carries great weight and can move, anger or inspire at home and around the world.” These findings make perfecting this method of communication with the people even more crucial to master. One part of doing so requires keeping in mind what the main, general goals of these speeches are.

Connection to Audience

While presidents and politicians deliver many different types of speeches which often have contrasting tones and messages depending on the occasion, there is always an exigence for politicians to make efforts to connect with their audience. This in turn results in a more positive audience perception and reaction to both the president and his speech. Later in the guide, specific rhetorical and linguistic strategies and moves will be discussed which have proven effective in fostering a connection with audience members through speech.

This overall notion of establishing connection works to break down barriers and make the audience feel more comfortable with and trusting of the speech giver. McNearney points to FDR as a president who successfully connected with the people, largely, she claims, through his fireside chats. The fireside chats exemplified a president making use of the media for the first time “to present a very carefully crafted message that was unfiltered and unchallenged by the press” (McNearney). Today, we often see our presidents use Twitter as a media avenue to connect and present their “unfiltered” version of a policy or goal.

Lasting Message

Another central and overarching goal presidents and politicians should keep in mind when writing and delivering a speech is to make it lasting and memorable. It is challenging to predict what exactly will resonate with people in a way that makes a speech long remembered. Many of the various rhetorical and linguistic techniques outlined in section III have helped former presidents deliver speeches that have become known as some of “the greats.”

Sometimes it is a matter of taking risks with a speech. Martin Luther King and Barack Obama are among some of the most powerful speech-givers our country has seen. Both men took risks in many of their speeches. Mcnearney points to Obama’s “A More Perfect Union” speech as being “risky” in its focus and discussion on racial tensions in the country, an often avoided or untouched conversation. But, the speech was well-received and well-remembered, proving this risk was worth it.

What to Do: Rhetorical and Linguistic Moves

A conjunction of previous findings from various scholars and my own research make up this section to portray the effective rhetorical and linguistic strategies that have been employed in successful presidential speech.

Emotive Language

In section II one of the central goals discussed in a presidential speech is to appeal to one’s audience . An effective way to do so is through emotive language and general emotional appeal. In their study, Erisen et al. note the value of “strik[ing] an emotional chord with the public” as a means to gain public support, increase public awareness, and overall aid presidents in pursuing their political agendas (469). They work to prove the effectiveness of this strategy through an analysis of an Obama speech, delivered during a time of growing economic crisis in the country.

Erisen et al. identify Obama’s implementation of both emotional and optimistic tones as rhetorical moves to connect with and appeal to his audience of constituents. The success of his use of emotionally-related rhetorical strategies are evident findings that came out of a survey that “reported that 68% of speech-watchers had a ‘positive reaction’ and that 85% felt ‘more optimistic’ about the direction the country was heading” (Erisen et al., 470). Stewart et al. also find that “more emotionally evocative messages… lead to higher levels of affective response by viewers” (125). This clear data indicates the power connecting with an audience through emotion can have on their response and future outlook.

Optimistic Tone

Along with Obama’s “optimistic tone” described above, others have employed what has been described as both hopeful and reassuring tones as rhetorical moves to appeal to an audience. Two of the ten “most important modern presidential speeches,” as selected by the nonpartisan affiliated scholars of the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, are JFK’s address on the space effort and FDR’s first inaugural address (McNearney). JFK’s address was successful and well-received because of the hopeful tone he employs when discussing the goal to land a man on the moon. He gave the people an optimistic perspective on this lofty goal, making “Americans feel like there was nothing we couldn’t do” (McNearney). In his inaugural address, Roosevelt too pairs bold claims with optimism and reassurance to his audience.

Inclusive Language

Another found strategy utilized by presidents to appeal to their audience through speech is the use of inclusive language. In Teten’s study, he looks at the use of the words “we” and “our”, specifically, in presidential State of the Union Addressesses over time. His findings revealed a steady increase in these words within the speeches over time. The usage of these “public address and inclusion words” create an appeal with presidents’ audiences because they help presidents in creating “an imagined community in which the president and his listeners coexist on a level plane (Teten, 339-342). These findings illustrate the importance of not presenting oneself as an omnipotent power and leader, but rather a normal citizen of the country like all of those watching. Identifying oneself with the audience this way breaks down any barriers present.

Persuasive Language

Persuasion is another often-used rhetorical strategy, especially during presidential campaigns. In their study about “language intensity,” Clementson et al. look at the use of “persuasive language” as a strategy presidential candidates employ during their campaigns. They assert that “candidates seem to vary their language as they try to persuade audiences to perceive them favorably” (Clementson et al., 592). In referring to this persuasive rhetorical strategy, they utilize the term “problem-solution structure” as one which is often well-received by an audience. People appreciate hearing exactly how a president or presidential candidate plans to fix a problem at hand.

What Not to Do

As stated earlier, while there are many speeches that are excellently written and delivered, there, too, are many speeches that flop. Alexander Meddings wrote an article which spotlights a number of political speeches which he deems some of the “worst” in modern history. In comparing what makes a good versus a bad speech he asserts that “a bad speech must, by definition, be flat, garbled and publicly damaging either for the speaker or for the cause they’re seeking to promote” (Meddings). In looking at some of the characteristics that make up some of the “worst” speeches, this section will highlight what not to do in the process of working to compose and deliver a successful speech.

The research demonstrates that length of speech actually proves very important. In Teten’s study, in addition to looking at inclusive language over time in presidential State of the Union Addresses, he also graphically measured the length, specifically number of words, of the addresses across time. His results proved interesting. There was a rise in length of these speeches from the first one delivered to those delivered in the early 1900s and then there was a sudden and far drop. There was a movement around the time of the drop to make speeches more concise, and it is clear, since they have remained much shorter as time has gone on, this choice was well-received.

Meddings alludes to this in his piece, describing both William Henry Harrison’s presidential inaugural address and Andrew Johnson’s vice-presidential inaugural address as some of the worst speeches, largely because of how dragged out they were. A very important aspect of speech-giving is capturing the audience’s attention, and this cannot be accomplished through a lengthy, uninteresting oration.

Lying And/or Contradiction

Though it should be fairly obvious that one should not lie in a speech, for the consequences will be great, there have been a number of presidents and politicians who have done so. Regan, Clinton, and Trump are all among the presidents and politicians who have made false statements or promises within speeches. Though it is understandable that a politician would want to speak towards what he or she knows will resonate and appeal to the audience, doing so in a false or manipulative way is not commendable and will lead to much greater backlash than just being honest.

Word Choice

Some politicians have been caught lying in speeches when trying to cover up a controversy or scandal. Though one should try to avoid any sort of controversy, a president or person in power has to expect to have to talk on some difficult or delicate topics. This is where careful word choice becomes vital. Often the way to ensure a speech is written eloquently, carefully, and inoffensively is through various rounds of editing from a number of different eyes.

Applications to All Forms of Speech-Giving

This guide should prove helpful for not only those looking to run for office, but for everyone. The various strategies and techniques given within this guide are, for the most part, broad enough that they can be applied to any form of speech-giving or presenting. We will all have to give a speech, a toast, a presentation, and countless other forms of written or oral works in our lives. Refer to this guide when doing so.

In terms of political or presidential speech specifically, though, in a sense there is not a clear formula for how to write and deliver them. In studies looking at various different successful presidential speeches, orators, and speechwriters, it is clear they all have their own unique style and form that works for them. But, the tips provided in this guide will certainly work to help to create a proficient and successful political speech writer and orator.

Works Cited

Clementson, David E., Paola Pascual-Ferr, and Michael J. Beatty. “When does a Presidential Candidate seem Presidential and Trustworthy? Campaign Messages through the Lens of Language Expectancy Theory.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 46.3 (2016): 592-617. ProQuest. Web. 10 Dec. 2019.

Erisen, Cengiz, and José D. Villalotbos. “Exploring the Invocation of Emotion in Presidential Speeches.” Contemporary Politics , vol. 20, no. 4, 2014, pp. 469–488., doi:10.1080/13569775.2014.968472.

McNearney, Allison. “10 Modern Presidential Speeches Every American Should Know.”

History.com , A&E Television Networks, 16 Feb. 2018, www.history.com/news/10-modern-presidential-speeches-every-american-should-know.

Meddings, Alexander. “The 8 Worst Speeches in Modern Political History.”

HistoryCollection.co , 9 Nov. 2018, historycollection.co/8-worst-speeches-modern-political-history/7/.

Stewart, Patrick A., Bridget M. Waller, and James N. Schubert. “Presidential Speechmaking

Style: Emotional Response to Micro-Expressions of Facial Affect.” Motivation and Emotion 33.2 (2009): 125-35. ProQuest. Web. 1 Oct. 2019.

Teten, Ryan. “Evolution of the Modern Rhetorical Presidency: Presidential Presentation and

Development of the State of the Union Address.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 33.2 (2003): 333-46. ProQuest. Web. 30 Sep. 2019.

Writing Guides for (Almost) Every Occasion Copyright © 2020 by Katie Clower is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Manage Account

- Solar Eclipse

- Bleeding Out

- Things to Do

- Public Notices

- Help Center

How to write an inaugural address

The inaugural address is the center stage of american public life. it is a place where rhetorical ambition is expected. it symbolizes the peaceful transfer of power -- something relatively rare in human history..

By William McKenzie|Contributor

4:03 PM on Jan 10, 2017 CST

There are speeches, and then there are speeches. An inaugural address seems to be in a class of its own. In Lincoln's case, his words ended up chiseled in stone at the Lincoln Monument. How does a president, or president-elect, even start tackling an address that could shape history?

The inaugural address is the center stage of American public life. It is a place where rhetorical ambition is expected. It symbolizes the peaceful transfer of power -- something relatively rare in human history. It provides the public, Congress and members of a new president's own administration an indication of his tone and vision. It is intended to express the best, most inspiring, most unifying version of president's core beliefs. And that requires knowing your core beliefs.

I read that you went back and studied all prior inaugural addresses before starting to work on President Bush's 2001 inaugural address. What did you learn from that experience? Would you recommend it for others who go through this process?

Get smart opinions on the topics North Texans care about.

By signing up you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy

It is a pretty tough slog in the early 19 th century, before getting to Abraham Lincoln and the best speech of American history, his Second Inaugural Address. That speech is remarkable for telling a nation on the verge of a military victory that had cost hundreds of thousands of lives that it was partially responsible for the slaughter; that its massive suffering represented divine justice.

Strictly speaking, it is only necessary to read the greatest hits among inaugurals to get a general feel. But it would be a mistake to miss some less celebrated but worthy efforts such as Richard Nixon in 1968: "America has suffered from a fever of words... we cannot learn from each other until we stop shouting at one another." This theme of national unity is a consistent thread throughout inaugural history.

Having worked on two inaugural addresses, and read so many, do they by and large set the stage for the next four years? Or, are they mostly forgotten?

Some of the speeches are undeniably forgettable. But even those are never really forgotten. They are some of the most revealing documents of presidential history, when a chief executive tries to put his ideals and agenda into words. Students of the presidency will read those speeches to help understand a president's self-conception and the political atmosphere of his time.

What was the writing and editing process like with President Bush on these addresses? And what did you all learn from the first address that shaped the second one in 2005?

President Bush's first inaugural address was intended to be a speech of national unity and healing. He had just won a difficult election in which he lost the popular vote (which certainly sounds familiar). It was a moment of some drama, with his opponent, Vice President Gore, seated on the podium near the President-Elect.

President Bush would often edit speeches by reading them aloud to a small group of advisers, which he did several times at Blair House during the transition. "Our unity, our Union," he said in his first inaugural, "is a serious work of leaders and citizens and every generation. And this is my solemn pledge: I will work to build a single nation of justice and opportunity."

The second inaugural was quite different, not so much a speech of national unity as a speech of national purpose. President Bush had a strong vision of what he wanted his second inaugural to accomplish. "I want it to be the freedom speech," he told me in the Cabinet room after the first Cabinet meeting following his reelection had broken up. It was intended to be a tight summary of Bush's foreign policy approach, setting high goals while recognizing great difficulties in the post-9/11 world.

"We are led, by events and common sense, to one conclusion," he said. "The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world."

Globalization figured prominently as a theme in Donald Trump's victorious presidential campaign. I would assume we are likely to hear more in his address about America's place in the globalized economy. But what do you think? What themes are we likely to hear?

We are seeing a reaction to globalization across the western world, and this set of issues certainly motivated a portion of President-elect Trump's coalition. It is essential for political leaders to help a generation of workers prepare for an increasingly skills-based economy. It is a fantasy, however, for a political leader to promise the reversal of globalization, any more than he or she could promise the reversal of industrialization. Trump should address the struggles of middle and working class Americans. But it is deceptive and self-destructive to blame those struggles on trade and migrants.

What happens after these big speeches are given? Do presidents and the team that helped prepare them go back to the White House and high-five each other? I guess it would be a little indecorous to throw Gatorade buckets on each other, like victorious football teams do after winning the Super Bowl.

As I remember it, the new president attends a lunch hosted by congressional leaders. Then he goes to the reviewing stand in front of the White House for the inaugural parade. (Jimmy Carter actually walked in the parade a bit.)

I remember entering the White House that afternoon, walking into the Roosevelt Room (where senior staff and other meetings take place) and watching a workman take down the picture of Franklin Roosevelt from above the fireplace and put up the picture of Teddy Roosevelt. I felt fortunate to be present at a great tradition. In fact, every day at the White House was an honor.

This Q&A was conducted by William McKenzie, editor of The Catalyst: A Journal of Ideas from the Bush Institute. Email: [email protected] .

William McKenzie|Contributor

Doctor accused of tampering with IV bags at Dallas surgery center to stand trial

Eclipse-viewing chances in dallas-fort worth area ‘not looking good,’ weather service says, dashcam footage shows ‘scary’ dallas crash possibly connected with chiefs wr rashee rice, kansas city chiefs’ rashee rice suspected in connection with 6-vehicle crash in dallas, gasoline prices rising a bit faster than usual, but don’t fret, experts say.

EVENTS & ENTERTAINING

Food & drink, relationships & family, how to write an inaugural speech, more articles.

- How to Write a Farewell Graduation Speech

How to Give a Wedding Reception Speech

How to Avoid a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Components of Effective Communication

How to Describe a Love Relationship

An inaugural speech captures the triumphs and hopes for the future in the winner of a political campaign. After a long and tiresome journey to the top of the political heap, you now can rejoice and let others in on your victory. But before you put that pen to paper or those fingers to the keyboard, you may want to learn a few important tips on what makes an inaugural speech great and how to inspire the citizens you preside over to create change.

Reflect on the moments that led to your victory. Think of the setbacks and the struggles you endured to finally reach this office. You will want to jot down a few distinct memories that touched you in terms of your fight to gain the position you now have. Try to add to your notes as much detailed information of such memories so that you will write more easily when you begin.

Recognize a theme that symbolizes your platform, as well as your fight to gain office. A recurrent theme of President Obama’s campaign was “hope,” and in his inaugural speech, he presented that theme by discussing the trials American people have faced through the years and how they always overcame them through determination and hope (see Ref 1, 3).

Craft an outline that has at least three parts; an introduction, a body and a conclusion. In your outline, use the notes and theme to create an organized list of what you want to say in your speech (see Ref 2).

Start the speech by writing a powerful opening that draws your audience in, making them want to hear more. You can begin with a line that sums up what your supporters feel; in Obama’s speech, he stated that “I stand here today humbled by the task before us, grateful for the trust you have bestowed, mindful of the sacrifices borne by our ancestors.” Yet you can also begin with a story that mirrors the trials and tribulations you faced and will soon take on as a newly elected leader. Whatever you decide, just make sure it captures your audience’s attention.

Write the following paragraphs addressing your citizens’ desires and fears. You can use figurative language to describe your positions on subjects, but it is best to be direct and simplistic when discussing more serious events or situations. You, as a leader, have received the office because people believed that you represented the future so you should keep them believing that, while also remaining honest and somewhat stoic. Becoming too emotional will not give you an air of leadership, so keep that in mind when writing the speech.

End the speech with a call to arms for your fellow citizens. Let them know that you will do your best but that you can only achieve great things with their help. Bring the speech full circle by addressing your theme in a subtle way, and leave your audience with an inspirational last sentence.

Related Articles

How to Write a Farewell Graduation ...

How to Have a Sarcastic Sense of Humor

How to Write Letter to a New Girlfriend

How to Manage Conflict Through ...

Tips for Forgiving Your Best Friend

How to Build Trust and Credibility

How to Improve Oral Expression

Correct Way to Write an Acceptance for ...

How to Tell a Co-Worker His Email Is ...

How to Write a Speech for a Special ...

How to Make My Boyfriend Feel Competent ...

Creative Maid of Honor Speech Ideas

How to Deal With Someone Who Accuses ...

How to Give a Thank You Speech

Perceptual Barriers to Communication

How to Clear Up Misunderstandings in a ...

- D Lugan: Speech Analysis - Barack Obama's Inaugural Speech

- Scholastic: Writing with Writers - Speech Writing

- CNN: Obama's Inaugural Speech

Gerri Blanc began her professional writing career in 2007 and has collaborated in the research and writing of the book "The Fairy Shrimp Chronicles," published in 2009. Blanc holds a Bachelor of Arts in literature and culture from the University of California, Merced.

Photo Credits

Close-up of President's Face on a dollar bill image by PaulPaladin from Fotolia.com

- Today's Paper

- Most Popular

- N.Y. / Region

- Real Estate

- Politics Home

- FiveThirty Eight

- Election 2012

- G.O.P. Primary

- Inside Congress

UPDATED January 17, 2013

Build your own inaugural address, 1. how will you draw on america's past.

Presidents frequently reflect on the nation's history.

March 5, 1849 Zachary Taylor, like many before him, cited George Washington.

To defend your policies

“We are warned by the admonitions of history and the voice of our own beloved Washington to abstain from entangling alliances with foreign nations.”

January 20, 1973 Richard Nixon resigned in 1974.

To win public support

“Let us pledge together to make these next four years the best four years in America's history, so that on its 200th birthday America will be as young and as vital as when it began, and as bright a beacon of hope for all the world.”

January 20, 1953 Dwight D. Eisenhower's first Inaugural Address.

To measure national progress

“We have passed through the anxieties of depression and of war to a summit unmatched in man's history.”

January 20, 1993 Bill Clinton took office in 1993.

To show a changing world

“When George Washington first took the oath I have just sworn to uphold, news traveled slowly across the land by horseback and across the ocean by boat. Now, the sights and sounds of this ceremony are broadcast instantaneously to billions around the world.”

2. How will you acknowledge the moment?

Absent a crisis, Inaugural Addresses often emphasize continuity of government.

January 20, 1981 Ronald Reagan succeeded Jimmy Carter.

Celebrate how routine it is

“The orderly transfer of authority as called for in the Constitution routinely takes place as it has for almost two centuries and few of us stop to think how unique we really are.”

March 4, 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt urged action to fight the Great Depression

Push for immediate action

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror, which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

March 4, 1845 James Polk, like many early presidents, celebrated the Constitution.

Honor the Constitution

“The Constitution itself, plainly written as it is, the safeguard of our federative compact, the offspring of concession and compromise, binding together in the bonds of peace and union this great and increasing family of free and independent States, will be the chart by which I shall be directed.”

March 4, 1873 Ulysses S. Grant won re-election overwhelmingly in 1872.

Proclaim victory over your enemies

“I have been the subject of abuse and slander scarcely ever equaled in political history, which to-day I feel that I can afford to disregard in view of your verdict, which I gratefully accept as my vindication.”

3. What is America's biggest challenge?

Economic problems are among the most cited threats.

March 4, 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 started a large-scale program of public works.

End mass unemployment

“Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. This is no unsolvable problem if we face it wisely and courageously.”

January 20, 2005 George W. Bush's second Inaugural Address focused on expanding freedom.

Spreading freedom

“From the viewpoint of centuries, the questions that come to us are narrowed and few: Did our generation advance the cause of freedom? And did our character bring credit to that cause?”

March 4, 1897 William McKinley entered office amid a depression and arguments over a gold standard.

Protecting our credit

“The credit of the Government, the integrity of its currency, and the inviolability of its obligations must be preserved. This was the commanding verdict of the people, and it will not be unheeded.”

January 20, 1965 Lyndon B. Johnson helped establish Medicare, Medicaid and food stamps.

Reducing inequality

“In a land of great wealth, families must not live in hopeless poverty. In a land rich in harvest, children just must not go hungry.”

4. What is the role of government?

Views of govenrment have evolved, from frequent praise after the Revolutionary War to increased skepticism today.

January 20, 1937 Franklin D. Roosevelt said that government must act during the Great Depression.

To solve our biggest problems

“Democratic government has innate capacity to protect its people against disasters once considered inevitable, to solve problems once considered unsolvable.”

January 20, 1981 Ronald Reagan won his first term in the face of a weak economy.

To get out of the way

“In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

January 20, 2009 Barack Obama was re-elected in 2012.

To be practical

“The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works.”

March 4, 1817 James Monroe and other early presidents frequently praised government.

To continue being awesome

“The heart of every citizen must expand with joy when he reflects how near our Government has approached to perfection; that in respect to it we have no essential improvement to make.”

5. How will you unite Americans?

As early as Thomas Jefferson, presidents have urged Americans to unite after close elections.

March 4, 1801 Thomas Jefferson won office after the bitter, partisan election of 1800.

Cite shared values

“But every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

January 20, 1961 John F. Kennedy spoke of "defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger."

Appeal to sense of duty

“And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

March 4, 1881 James A. Garfield said Americans should accept emancipation.

Show how we have moved past old problems

“My countrymen, we do not now differ in our judgment concerning the controversies of past generations, and fifty years hence our children will not be divided in their opinions concerning our controversies.”

March 4, 1861 Abraham Lincoln appealed for states to rejoin the Union.

Warn of disunion

“I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. ”

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

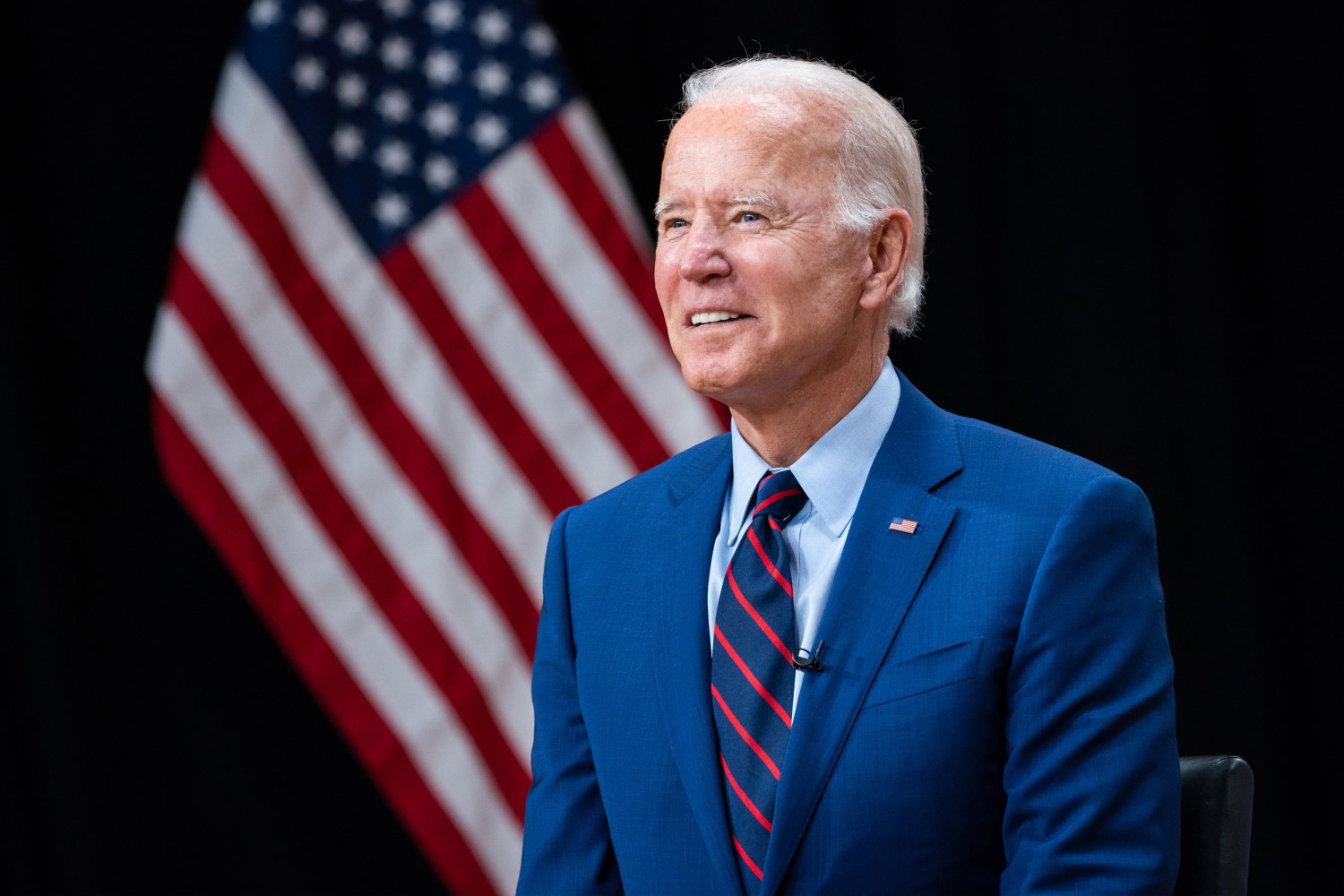

Inaugural Address by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.

The United States Capitol

11:52 AM EST

THE PRESIDENT: Chief Justice Roberts, Vice President Harris, Speaker Pelosi, Leader Schumer, Leader McConnell, Vice President Pence, distinguished guests, and my fellow Americans.

This is America’s day.

This is democracy’s day.

A day of history and hope.

Of renewal and resolve.

Through a crucible for the ages America has been tested anew and America has risen to the challenge.

Today, we celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause, the cause of democracy.

The will of the people has been heard and the will of the people has been heeded.

We have learned again that democracy is precious.

Democracy is fragile.

And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed.

So now, on this hallowed ground where just days ago violence sought to shake this Capitol’s very foundation, we come together as one nation, under God, indivisible, to carry out the peaceful transfer of power as we have for more than two centuries.

We look ahead in our uniquely American way – restless, bold, optimistic – and set our sights on the nation we know we can be and we must be.

I thank my predecessors of both parties for their presence here.

I thank them from the bottom of my heart.

You know the resilience of our Constitution and the strength of our nation.

As does President Carter, who I spoke to last night but who cannot be with us today, but whom we salute for his lifetime of service.

I have just taken the sacred oath each of these patriots took — an oath first sworn by George Washington.

But the American story depends not on any one of us, not on some of us, but on all of us.

On “We the People” who seek a more perfect Union.

This is a great nation and we are a good people.

Over the centuries through storm and strife, in peace and in war, we have come so far. But we still have far to go.

We will press forward with speed and urgency, for we have much to do in this winter of peril and possibility.

Much to repair.

Much to restore.

Much to heal.

Much to build.

And much to gain.

Few periods in our nation’s history have been more challenging or difficult than the one we’re in now.

A once-in-a-century virus silently stalks the country.

It’s taken as many lives in one year as America lost in all of World War II.

Millions of jobs have been lost.

Hundreds of thousands of businesses closed.

A cry for racial justice some 400 years in the making moves us. The dream of justice for all will be deferred no longer.

A cry for survival comes from the planet itself. A cry that can’t be any more desperate or any more clear.

And now, a rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat.

To overcome these challenges – to restore the soul and to secure the future of America – requires more than words.

It requires that most elusive of things in a democracy:

In another January in Washington, on New Year’s Day 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

When he put pen to paper, the President said, “If my name ever goes down into history it will be for this act and my whole soul is in it.”

My whole soul is in it.

Today, on this January day, my whole soul is in this:

Bringing America together.

Uniting our people.

And uniting our nation.

I ask every American to join me in this cause.

Uniting to fight the common foes we face:

Anger, resentment, hatred.

Extremism, lawlessness, violence.

Disease, joblessness, hopelessness.

With unity we can do great things. Important things.

We can right wrongs.

We can put people to work in good jobs.

We can teach our children in safe schools.

We can overcome this deadly virus.

We can reward work, rebuild the middle class, and make health care secure for all.

We can deliver racial justice.

We can make America, once again, the leading force for good in the world.

I know speaking of unity can sound to some like a foolish fantasy.

I know the forces that divide us are deep and they are real.

But I also know they are not new.

Our history has been a constant struggle between the American ideal that we are all created equal and the harsh, ugly reality that racism, nativism, fear, and demonization have long torn us apart.

The battle is perennial.

Victory is never assured.

Through the Civil War, the Great Depression, World War, 9/11, through struggle, sacrifice, and setbacks, our “better angels” have always prevailed.

In each of these moments, enough of us came together to carry all of us forward.

And, we can do so now.

History, faith, and reason show the way, the way of unity.

We can see each other not as adversaries but as neighbors.

We can treat each other with dignity and respect.

We can join forces, stop the shouting, and lower the temperature.

For without unity, there is no peace, only bitterness and fury.

No progress, only exhausting outrage.

No nation, only a state of chaos.

This is our historic moment of crisis and challenge, and unity is the path forward.

And, we must meet this moment as the United States of America.

If we do that, I guarantee you, we will not fail.

We have never, ever, ever failed in America when we have acted together.

And so today, at this time and in this place, let us start afresh.

Let us listen to one another.

Hear one another. See one another.

Show respect to one another.

Politics need not be a raging fire destroying everything in its path.

Every disagreement doesn’t have to be a cause for total war.

And, we must reject a culture in which facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.

My fellow Americans, we have to be different than this.

America has to be better than this.

And, I believe America is better than this.

Just look around.

Here we stand, in the shadow of a Capitol dome that was completed amid the Civil War, when the Union itself hung in the balance.

Yet we endured and we prevailed.

Here we stand looking out to the great Mall where Dr. King spoke of his dream.

Here we stand, where 108 years ago at another inaugural, thousands of protestors tried to block brave women from marching for the right to vote.

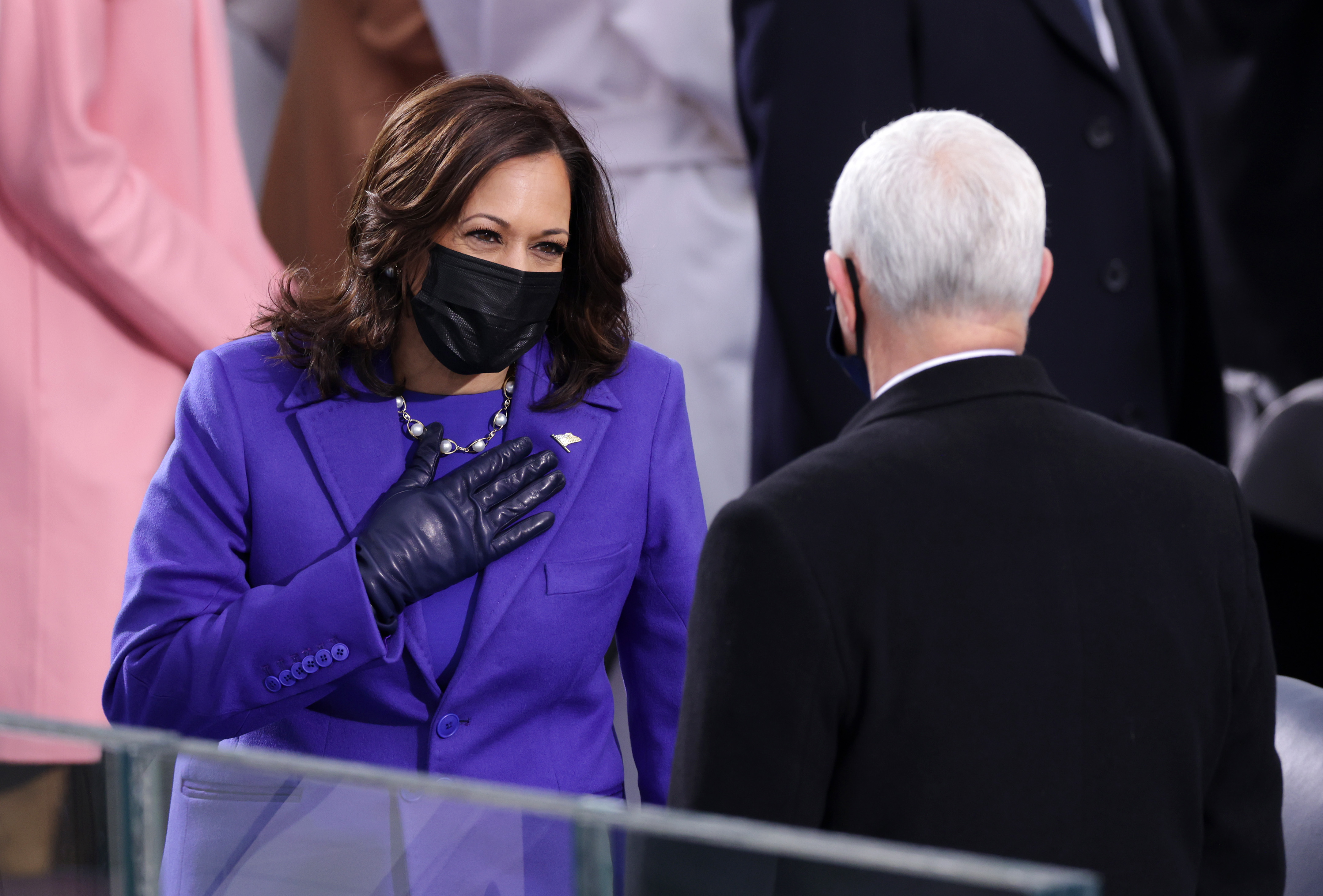

Today, we mark the swearing-in of the first woman in American history elected to national office – Vice President Kamala Harris.

Don’t tell me things can’t change.

Here we stand across the Potomac from Arlington National Cemetery, where heroes who gave the last full measure of devotion rest in eternal peace.

And here we stand, just days after a riotous mob thought they could use violence to silence the will of the people, to stop the work of our democracy, and to drive us from this sacred ground.

That did not happen.

It will never happen.

Not tomorrow.

To all those who supported our campaign I am humbled by the faith you have placed in us.

To all those who did not support us, let me say this: Hear me out as we move forward. Take a measure of me and my heart.

And if you still disagree, so be it.

That’s democracy. That’s America. The right to dissent peaceably, within the guardrails of our Republic, is perhaps our nation’s greatest strength.

Yet hear me clearly: Disagreement must not lead to disunion.

And I pledge this to you: I will be a President for all Americans.

I will fight as hard for those who did not support me as for those who did.

Many centuries ago, Saint Augustine, a saint of my church, wrote that a people was a multitude defined by the common objects of their love.

What are the common objects we love that define us as Americans?

I think I know.

Opportunity.

And, yes, the truth.

Recent weeks and months have taught us a painful lesson.

There is truth and there are lies.

Lies told for power and for profit.

And each of us has a duty and responsibility, as citizens, as Americans, and especially as leaders – leaders who have pledged to honor our Constitution and protect our nation — to defend the truth and to defeat the lies.

I understand that many Americans view the future with some fear and trepidation.

I understand they worry about their jobs, about taking care of their families, about what comes next.

But the answer is not to turn inward, to retreat into competing factions, distrusting those who don’t look like you do, or worship the way you do, or don’t get their news from the same sources you do.

We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal.

We can do this if we open our souls instead of hardening our hearts.

If we show a little tolerance and humility.

If we’re willing to stand in the other person’s shoes just for a moment. Because here is the thing about life: There is no accounting for what fate will deal you.

There are some days when we need a hand.

There are other days when we’re called on to lend one.

That is how we must be with one another.

And, if we are this way, our country will be stronger, more prosperous, more ready for the future.

My fellow Americans, in the work ahead of us, we will need each other.

We will need all our strength to persevere through this dark winter.

We are entering what may well be the toughest and deadliest period of the virus.

We must set aside the politics and finally face this pandemic as one nation.

I promise you this: as the Bible says weeping may endure for a night but joy cometh in the morning.

We will get through this, together

The world is watching today.

So here is my message to those beyond our borders: America has been tested and we have come out stronger for it.

We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again.

Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s.

We will lead not merely by the example of our power but by the power of our example.

We will be a strong and trusted partner for peace, progress, and security.

We have been through so much in this nation.

And, in my first act as President, I would like to ask you to join me in a moment of silent prayer to remember all those we lost this past year to the pandemic.

To those 400,000 fellow Americans – mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, friends, neighbors, and co-workers.

We will honor them by becoming the people and nation we know we can and should be.

Let us say a silent prayer for those who lost their lives, for those they left behind, and for our country.

This is a time of testing.

We face an attack on democracy and on truth.

A raging virus.

Growing inequity.

The sting of systemic racism.

A climate in crisis.

America’s role in the world.

Any one of these would be enough to challenge us in profound ways.

But the fact is we face them all at once, presenting this nation with the gravest of responsibilities.

Now we must step up.

It is a time for boldness, for there is so much to do.

And, this is certain.

We will be judged, you and I, for how we resolve the cascading crises of our era.

Will we rise to the occasion?

Will we master this rare and difficult hour?

Will we meet our obligations and pass along a new and better world for our children?

I believe we must and I believe we will.

And when we do, we will write the next chapter in the American story.

It’s a story that might sound something like a song that means a lot to me.

It’s called “American Anthem” and there is one verse stands out for me:

“The work and prayers of centuries have brought us to this day What shall be our legacy? What will our children say?… Let me know in my heart When my days are through America America I gave my best to you.”

Let us add our own work and prayers to the unfolding story of our nation.

If we do this then when our days are through our children and our children’s children will say of us they gave their best.

They did their duty.

They healed a broken land. My fellow Americans, I close today where I began, with a sacred oath.

Before God and all of you I give you my word.

I will always level with you.

I will defend the Constitution.

I will defend our democracy.

I will defend America.

I will give my all in your service thinking not of power, but of possibilities.

Not of personal interest, but of the public good.

And together, we shall write an American story of hope, not fear.

Of unity, not division.

Of light, not darkness.

An American story of decency and dignity.

Of love and of healing.

Of greatness and of goodness.

May this be the story that guides us.

The story that inspires us.

The story that tells ages yet to come that we answered the call of history.

We met the moment.

That democracy and hope, truth and justice, did not die on our watch but thrived.

That our America secured liberty at home and stood once again as a beacon to the world.

That is what we owe our forebearers, one another, and generations to follow.

So, with purpose and resolve we turn to the tasks of our time.

Sustained by faith.

Driven by conviction.

And, devoted to one another and to this country we love with all our hearts.

May God bless America and may God protect our troops.

Thank you, America.

12:13 pm EST

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

clock This article was published more than 11 years ago

Write your own inaugural address

Here's the view of @BarackObama on Jan. 21 for #inaug2013 pic.twitter.com/X4bigfLn — JCCIC (@JCCIC) January 13, 2013

Thousands of viewers will brave lengthy, maze-like security procedures and frigid temperatures on Inauguration Day for the chance to watch -- and hear -- history being made.

Inspiring that crowd and the millions watching at home is no easy task for a president, or a presidential speechwriter. Fortunately for them, the best speeches generally follow a similar structure: A greeting, description of the state of the country, plans to address major issues, and an appeal to the crowd before concluding.

Words Matter: What an Inaugural Address Means Now

Jan 15, 2021, 6:35 AM

UNIFYING THEME: Polarization: Its Past, Present and Future

Presidents' words create national identity. For better or worse, presidential rhetoric tells the American people who they are. Ultimately, a president's voice must provide the American people with a concrete vision of how-and more importantly, why-to move forward together.

RELATED NEWS featuring Vanessa Beasley:

- U.S. News & World Report: "Limited Power for the World's Most Powerful Man" (July 16, 2021)

By Vanessa B. Beasley , Associate Professor of Communication Studies and Vice Provost for Academic Affairs

Presidents' words matter. Such a statement may seem especially relevant right now, but it has been true throughout the course of U.S. history. Richard Neustadt wrote in 1960 that "presidential power is the power to persuade," and much of his focus was on how chief executives must bargain with members from other branches of government. Yet consider how much of presidents' executive action can be done through their words alone as well as how far those words can now reach due to the rise of mass and social media. They can veto, nominate, declare war, agree to peace, issue executive orders, define the state of the union, and pardon. Today, as Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson have argued, "[P]residential rhetoric is the source of executive power, enhanced in the modern presidency by the ability to speak where, when, and on whatever topic they choose and to reach a national audience through coverage by the electronic media."

In the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, many are thinking about the difference between what a president's words can do and what they should do. Recent images of the Capitol steps captured this contrast clearly when insurrectionists, determined to break into the building and terrorize its occupants, transformed the scaffolding installed for the ceremony of a peaceful transfer of power on Inauguration Day into scaling ladders. In the days since, amidst heightened fears for public safety, there have been recurring questions about what kinds of security will be required on Inauguration Day 2021. But what kinds of words could possibly be deployed as well?

When we consider the history of what most presidents have said when inaugurated, it is worth remembering this is an invented tradition; there is no Constitutional requirement for a new president to give an inaugural address. The actual requirement is only for the new president to be sworn in and take an oath per Article II, Section 1. Yet ever since George Washington chose to give an inaugural address in April 1789, in New York City, his successors have given such a speech. In addition to becoming a traditional part of a larger civic ritual, over time this speech has come to occupy a unique space in the public performance of the presidency.

Listening to-and later, watching-an inaugural address can inform both U.S. citizens and the broader world alike what kind of leader a new president will be. Think of a young John F. Kennedy, inexperienced in foreign policy, giving his inaugural address at the height of the Cold War, with outgoing president (and architect of D-Day) Dwight Eisenhower nearby in camera shot from almost every angle. Today Kennedy's inaugural address may be remembered for its elegant, moving chiasmus-"Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country"-focused on domestic service. On the day it was given, though, the visual message designed for a global television audience in general and the Soviet Union in particular was meant to be just as noticeable: The United States might have a new president, but it was no less prepared to protect democracy around the world.

As this example indicates, a presidential inaugural address is arguably less about an individual president and more about how well and fully he (and one day soon, she) comprehends this new role and its symbolic import. This speech offers the first public test. Does the new office holder truly know how to act on the oath just taken, acknowledging the necessity to transcend the views of one person or one party? In other words, this speech signals how much the new president understands what the presidency means-or can mean-to the American people, whose communal shared interests the U.S. president, as opposed to members of Congress shivering behind him, has vowed to safeguard. For this reason, the inaugural address needs to be grounded in historical tradition but also responsive to the emergent needs of its own time.

Arguably, few presidents have understood this need better than Washington did. In his inaugural address, he referred to the speech itself as his "first official act" as president, a role many of his contemporaries were dubious about due to fears the position would simply replicate the British monarchy or otherwise steer too much power into a nascent federal system. Within this context, Washington crafted the very first presidential words ever uttered for the purpose of reassuring his audience, those in attendance in the Senate Chamber as well as those who would read about the speech in the following days. His intentions were clear. He would remain humble and serve despite his own "anxieties," a word he used in the first sentence; remain reverent to the "Almighty Being who rules over the universe" and who might presumably favor the new nation; and, more than anything else, remain obliged to the new Congress (acknowledging he understood the Constitutional limitations imposed on the executive) and therefore the "public good."

To define this wholly new concept of an American public good, Washington did not spell out a policy agenda but identified what his role as its guardian would require: "no local prejudices, or attachments; no separate views, nor party animosities, will misdirect the comprehensive and equal eye which ought to watch over this great assemblage of communities and interests…." With Federalists and Anti-Federalists having been at odds about the structure and scope of the new government, Washington was not only carving out clear ground for the presidency, but he was also providing ideological rivals with an alternative way to view themselves. They might remain political adversaries, but they should always remember that they were the custodians of an "experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people," who must surely remain focused on "a regard for the public harmony."

It would be up to Washington's successors to similarly define and eventually expand American national identity in such transcendent terms. As I have argued elsewhere, the great majority of presidents have done so with remarkable similarity, using themes related to civil religion to define American identity as overriding other partisan or sectional allegiances. Historically, civil religious themes have been associated with American national identity not only because of their pseudo-religious aspects (e.g., a promise of providential favor on the United States, as in Washington's inaugural, or the subsequent political appropriation of John Winthrop's scriptural framing of the land as "a shining city on a hill") but also because of the idea that the nation offered its citizens opportunities to become someone new, a recurring theme of American identity also famously captured by early foreign observers such as Crevecoeur and de Tocqueville.

This idea of the inaugural address as an invitation to collective renewal--of convening a new beginning, together--is also one of the patterns identified by Campbell and Jamieson in their study of the characteristic rhetorical elements consistent in all presidential inaugurals over time. Especially after contentious elections, they write, this first speech must respond to an urgent need to "unif[y] the audience by reconstituting its members as 'the people,' who can witness and ratify the ceremony." Viewed through this lens, the address is therefore not only an opportunity for presidents to demonstrate an understanding of their role, but it is also an opportunity for "the people" to do the same.

An example is Thomas Jefferson's first inaugural after the fiercely divisive election of 1800, which was also the first time an incumbent president had not been reelected. To reunite a divided people, Jefferson did not ignore the reality of the divisions still among them or the unprecedented nastiness of the campaign. "During the contest of opinion through which we have passed, the animation of discussion and of exertion has sometimes worn an aspect which might impose on strangers unused to think freely and to speak and to write what they think," he noted, reminding citizens that it was their unique democratic privilege to be able to disagree so openly about politics. "But this now being decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the Constitution, all will, of course, arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good." Jefferson was defining American identity by setting a clear boundary: Americans follow the rules, even when they do not like the outcome.

And yet of course any discussion of Jefferson's definition of American character must state the obvious: Like Washington, he was never really speaking to or about all of the inhabitants of the United States. There was no acknowledgement of enslaved people or indigenous people as part of this common good. There was no sense that these people were part of what was being reunited after an election or at any other time either. Following the rules of the day, in fact, demanded otherwise, including the violent separation of kin and tribe in order to build a new nation. Likewise, while white women were considered invaluable to a virtuous republic, there was no understanding that their interests might be in any way different from the white men who voted presumably, if not always accurately, for them.

In 2021, an awareness of how many of "the people" have been ignored in prior inaugural addresses raises questions about what an inaugural address means now. If it is to be rooted in rhetorical traditions, which ones? Like other genres of presidential speech, inaugural addresses are constructed around pillars of baked-in impulses and assumptions held by previous generations about who deserved to be called an American and whose interests should be included in a non-partisan, unifying sense of the common good. Even one of the most beautiful phrases in any inaugural, Lincoln's appeal to the "better angels of our nature" in his first, gives pause when you realize that the "us" implied in Lincoln's sense of "our nature," was necessarily almost exclusively white and male because of who his intended audience in 1861 was as well as his stated intent in the same speech not to interfere with "the institution of slavery" during his presidency.

Does this fact mean that Lincoln's first words as president, like the traditions they were written to follow, are irrelevant to what presidents should do today when they invite the American people to renew their faith in a democratic republic? To the contrary, they are instructive exactly because they reveal where to begin the rhetorical work that remains to be done: the revision of a tradition of presidential speech with the explicit goal of expanding the common good into something larger than partisan interest or individual gain, as the previous examples indicate, but also making it clear in unequivocal terms that everyone has a stake in this good. Everyone.

At this moment, it may be difficult to imagine what that would sound like. Barack Obama's notion of the nation as an imperfect but evolving union comes to mind as one possible foundational trope, even though it originally came from one of his campaign speeches and not the bully pulpit. It may also be true that, over time, the televised spectacle of the inauguration itself-coverage of the formal breakfast, the fancy dress balls, and even the breathiness of the news announcers pointing out who is and is not attending this time-has increasingly turned our collective attention to the ceremony as primarily a visual event rather an oratorical one. If this is true, it could explain why Donald Trump clung so tightly to his claims about how many attendees packed onto the Capitol lawn and parade route in January, 2017. Perhaps his belief was that such imagery alone was sufficient to represent a nation united in its hopes for a new president.

Images are rhetorical, to be sure. I began this essay by referencing the horrific images of the U.S. Capitol on the afternoon of January 6, 2021. As haunting as those photographs and videos are, and as much as even a rhetorician like myself must concede that words cannot repair everything, words are almost always the place to start looking for both cause and effect. Now is the moment to take seriously what presidents' words can do.

A president's words on Inauguration Day reveal not only what kind of president he or she will be, but they also should offer an idiom of identity the American people might imagine they can share. In 2021, as it was in another speech given by Abraham Lincoln in 1863, it may be time to think carefully about how words may have the potential to remake America. At minimum, we must consider more expansively and honestly than ever before who "we" are, who "we" have been, and how "we" can move forward if the nation is to be renewed. Does the peaceful transition of power from one U.S. president to another require that a new chief executive give an inaugural address as part of a civic ritual of renewal? No. Does the prospect of authentic unity among the American people depend on the invocation of an expansive "us" able to imagine a common good not yet realized? Yes.

- Vanessa Beasley

Vanessa Beasley , a Vanderbilt University alumna and expert on the history of U.S. political rhetoric, is vice provost for academic affairs, dean of residential faculty and an associate professor of communication studies. As Vice Provost and Dean of Residential Faculty, she oversees Vanderbilt's growing Residential College System as well as the campus units that offer experiential learning inside and outside of the classroom.

Following stints on the faculty of Texas A&M University, Southern Methodist University and the University of Georgia, she returned to Vanderbilt in 2007 as a faculty member in the Department of Communication Studies . Active in the Vanderbilt community, she has served as chair of the Provost's Task Force on Sexual Assault, director of the Program for Career Development for faculty in the College of Arts and Science, and as a Jacque Voegeli Fellow of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities.

Beasley's areas of academic expertise include the rhetoric of American presidents, political rhetoric on immigration, and media and politics. She is the author of numerous scholarly articles, book chapters and other publications, and is the author of two books, Who Belongs in America? Presidents, Rhetoric , and Immigration and You, the People: American National Identity in Presidential Rhetoric, 1885-2000. She was recently named president-elect of the Rhetoric Society of America , set to begin her term in July 2022.

Beasley attended Vanderbilt as an undergraduate and earned a bachelor of arts in speech communication and theatre arts. She also holds a Ph.D. in speech communication from the University of Texas at Austin.

[1] Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Politics of Leadership (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1960), 11.

[2] Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words , 2 nd ed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 6.

[3] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-2.

[4] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/george-washington

[5] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/george-washington

[6] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/george-washington

[7] Vanessa B. Beasley, You, The People: American National Identity in Presidential Rhetoric (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004).

[8] Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words , 2 nd ed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[9] Campbell and Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency , 31.

[10] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-19

[11] Beasley, You, the People.

[12] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-34

[13] Authenticated text and audio available at https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88478467

[14] Gary Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

Explore Story Topics

- Polarization

- Polarization: Its Past Present and Future

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Communication Skills

- Public Speaking

- Speechwriting

How to Write a Presidential Speech

Last Updated: May 19, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Patrick Muñoz . Patrick is an internationally recognized Voice & Speech Coach, focusing on public speaking, vocal power, accent and dialects, accent reduction, voiceover, acting and speech therapy. He has worked with clients such as Penelope Cruz, Eva Longoria, and Roselyn Sanchez. He was voted LA's Favorite Voice and Dialect Coach by BACKSTAGE, is the voice and speech coach for Disney and Turner Classic Movies, and is a member of Voice and Speech Trainers Association. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 115,605 times.

Are you running for president? There are some tried and true ways to write an effective campaign speech. Maybe you're running for school president or another office. You want your speech to be memorable and persuasive!

Presidential Speech Template

Opening the Presidential Speech

- You should make this theme simple enough that you can express it in one sentence.

- Make sure that you repeat your theme several times throughout your speech, especially in the beginning, middle, and end.

- You could start the speech with an anecdote, a quip or a strong quote. Don’t be afraid to offer a little humor, but it immediately clears what you would bring to the table. [3] X Research source

- When ending a speech, you could say: “If I am elected school president, I will focus on lengthening lunch hours, adding more student clubs, and reducing student fees.”

- If you’re running for a student position, review sample student campaign speeches. There are many of these templates online.

- For example, if your audience is concerned about the economy, and you have training in economics, mention it--especially if your opponents do not.

- Tell the audience an anecdote relating to what sets you apart. It will make it more memorable.

Developing the Presidential Speech

- The middle of your speech should be the longest because that's where most of your content lies.

- Don't slack off on the beginning and end of your speech. Even though they are shorter, they can make your speech memorable--or forgettable.

- You could open by saying something like: "Here are the three things we need to change."

- Be specific. Use statistics and human anecdotes to highlight the problem. However, be brief. You want to focus on solutions more than problems.

- Boil the speech down to 2 to 3 key issues that you plan to change. Be very specific when you outline your solutions.

- Expand on each of your key promises by detailing the problem and how you plan to address it specifically.

- Don’t make the middle of the speech too dry. Constantly reinforce your personality and theme throughout the details of your promises.

- Go with the flow. If you notice your audience getting ants, liven up your speech or end it early.

- Stick by the event's rules. Some events may require that your speech is only 5 minutes, while others want it to be at least 30 minutes.

- If you are talking about the Vietnam war, you can make yourself more relatable to younger generations by mentioning the soldiers who were no older than themselves.

- If you are running for high school president, say that you will ensure the administration listens to student wishes for a longer lunch break.

- If you are running for school president, mention things you’ve done that helped the school to make you seem more qualified.

- If you come from a coal mining family, and you are giving your speech in a blue-collar area, mention it! This will make you more relatable.

- For example, if you want people to join your campaign, ask them to vote for you. Be sure to thank them for their consideration as well.

Delivering the Presidential Speech

- Some speeches play to people’s fears and anger, but the best ones remain positive and play toward people’s optimism. People want to know how you will improve things.

- This is why broadcast writing is less dense than print writing, generally. When writing a speech, keep the sentences concise.

- Try to use one direct point per sentence. People can understand complex topics better when they are reading.

- You don’t need to fixate on proper grammar, punctuation, and so forth in a speech that will be given verbally (and presidential speeches are designed to be spoken).

- It’s more important to capture the cadences and colloquialisms of regular speech, while staying true to yourself.

- Ancient philosophers who perfected the art of rhetoric called this “pathos.” An appeal to the emotions.

- The philosophers believed that the core of any persuasive speech should be logos (an appeal to reason). However, they believed that speeches without pathos failed to move.

- Have a clear idea of what you want to say. Keep the finest details confined to notes so that you can refer to them if you need to.

- Remember that giving a speech is theater. You need to be dramatic and show passion, but you don’t want to stumble over words or look down like you’re reading it.

- They say that when people get in trouble, it’s usually because they went negative.

- The best place to include a joke is in the opening of your speech. Create a rapport with the audience and use a joke that is specific to the location.

- Stay away from any offensive jokes and make sure a joke is appropriate to the occasion.

- Show, don't tell. Show your telling points with vivid human stories or a relatable anecdote.

Expert Q&A

- Remember to have good posture while you're giving your speech. Thanks Helpful 13 Not Helpful 1

- If you don't win the election, just remember to be a good sport to everybody. Your opportunities in the future are more likely to become greater. Thanks Helpful 11 Not Helpful 1

- Make eye contact. It's important not to spend the entire speech looking down! Thanks Helpful 10 Not Helpful 1

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://blog.prepscholar.com/good-persuasive-speech-topics

- ↑ Patrick Muñoz. Voice & Speech Coach. Expert Interview. 12 November 2019.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6sm47j-Am4

- ↑ http://presidentialrhetoric.com/campaign2012/index.html

- ↑ https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/17-3-organizing-persuasive-speeches/

- ↑ http://grammar.yourdictionary.com/style-and-usage/writing-a-school-election-speech.html

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jenna Lawrence

Nov 2, 2017

Did this article help you?

May 1, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Teacher Opportunities

- AP U.S. Government Key Terms

- Bureaucracy & Regulation

- Campaigns & Elections

- Civil Rights & Civil Liberties

- Comparative Government

- Constitutional Foundation

- Criminal Law & Justice

- Economics & Financial Literacy

- English & Literature

- Environmental Policy & Land Use

- Executive Branch

- Federalism and State Issues

- Foreign Policy

- Gun Rights & Firearm Legislation

- Immigration

- Interest Groups & Lobbying

- Judicial Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Political Parties

- Science & Technology

- Social Services

- State History

- Supreme Court Cases

- U.S. History

- World History

Log-in to bookmark & organize content - it's free!

- Bell Ringers

- Lesson Plans

- Featured Resources

Lesson Plan: 2021 Joe Biden Inauguration Viewing Guides

What Makes a Good Inaugural Address

Historian and author Michael Beschloss used examples of five historic inaugural addresses to discuss what makes an effective inaugural address. He cited the inaugural address of Lincoln (1865), Roosevelt (1933), Kennedy(1961), Reagan 1981, Bush (2001), and Obama (2009).

Description

This lesson provides several activities for students to help them understand events occurring on inauguration day and interpret the inaugural address that will be given by Joe Biden on January 20, 2021. Teachers can choose to have students view the inaugural address and use one of several viewing guides to analyze the speech. Activities and handouts include a note-taking chart, guiding questions, topical analysis, an evaluative rubric, and a BINGO game.

Teachers have the option of assigning one of the following viewing guides to students as they watch the January 20, 2021 inauguration of Joseph Biden. Each of these Google Docs include the links to the introductory video clip, a link to the inauguration and the individual assignment/activities. These assignments can be completed in steps as a class or students can complete these assignments on their own. To access and complete these assignments, students can make a copy of the following Google resources. Students can submit these assignments digitally by linking their completed copy of the Google Doc handout.

Handout: Inauguration General Note-Taking Chart (Google Doc)

Handout: Inaugural Address Guiding Questions (Google Doc)

Handout: Inauguration BINGO (Google Doc)

Handout: Analyzing the Inaugural Address by Topic (Google Doc)

- Handout: Inaugural Address Rubric Evaluation (Google Doc)

Before beginning class, have students brainstorm answers to the following questions. This can be adapted to synchronous remote learning by having students answer in the chat or on the discussion board.

What challenges are currently facing the country?

- What issues should President Biden include in his inaugural address?

INTRODUCTION:

Introduce the idea of an inaugural address by having them view the following video clip featuring author and historian Michael Bechloss. Students should answer each of the questions associated with the video clip.

Video Clip: What Makes a Good Inaugural Address (8:51)

What challenges faced Franklin Roosevelt in 1933? How did he use his inaugural speech to address these challenges?

According to Michael Bechloss, what makes a good speech?

How did Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address in 1865 meet the challenges of the time?

Why was the date of inauguration changed after the 1933 inauguration?

What was the focus of John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address? Why did he do this?

What similarities exist between the inaugural addresses discussed by Michael Bechloss?

Why is an understanding of history important to writing an effective inaugural address?

- Based on this information, what advice would you give to an incoming president as they write their inaugural address?

INAUGURATION DAY:

Using the video clip in the introduction as foundation, the following activities can be used to help students understand and analyze President Biden’s inaugural address on January 20, 2021. Choose one of the following activities for students to complete when viewing election night coverage.

Students can view coverage of the 2021 inauguration using the link below:

Video Clip: Video Clip: President Biden Inaugural Address (21:37)

INAUGURAL ADDRESS ACTIVITIES AND VIEWING GUIDES:

NOTE-TAKING CHART:

Students will use this handout as they view the inaugural address to take notes and focus on specific elements of the speech such as:

Specific Issues/Topics Discussed

Tone and Images Used

Words and Ideas Repeated Throughout

Notable Quotes/Historic Events/Important Documents Referenced

Principles of Government/American Ideals Referenced

The Role of Government in Addressing the Nation’s Problems

- Priorities for His Presidency