- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Social Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

- Identifying and Structuring Problems

- Investigating Ideas and Solutions

- Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Social problem-solving might also be called ‘ problem-solving in real life ’. In other words, it is a rather academic way of describing the systems and processes that we use to solve the problems that we encounter in our everyday lives.

The word ‘ social ’ does not mean that it only applies to problems that we solve with other people, or, indeed, those that we feel are caused by others. The word is simply used to indicate the ‘ real life ’ nature of the problems, and the way that we approach them.

Social problem-solving is generally considered to apply to four different types of problems:

- Impersonal problems, for example, shortage of money;

- Personal problems, for example, emotional or health problems;

- Interpersonal problems, such as disagreements with other people; and

- Community and wider societal problems, such as litter or crime rate.

A Model of Social Problem-Solving

One of the main models used in academic studies of social problem-solving was put forward by a group led by Thomas D’Zurilla.

This model includes three basic concepts or elements:

Problem-solving

This is defined as the process used by an individual, pair or group to find an effective solution for a particular problem. It is a self-directed process, meaning simply that the individual or group does not have anyone telling them what to do. Parts of this process include generating lots of possible solutions and selecting the best from among them.

A problem is defined as any situation or task that needs some kind of a response if it is to be managed effectively, but to which no obvious response is available. The demands may be external, from the environment, or internal.

A solution is a response or coping mechanism which is specific to the problem or situation. It is the outcome of the problem-solving process.

Once a solution has been identified, it must then be implemented. D’Zurilla’s model distinguishes between problem-solving (the process that identifies a solution) and solution implementation (the process of putting that solution into practice), and notes that the skills required for the two are not necessarily the same. It also distinguishes between two parts of the problem-solving process: problem orientation and actual problem-solving.

Problem Orientation

Problem orientation is the way that people approach problems, and how they set them into the context of their existing knowledge and ways of looking at the world.

Each of us will see problems in a different way, depending on our experience and skills, and this orientation is key to working out which skills we will need to use to solve the problem.

An Example of Orientation

Most people, on seeing a spout of water coming from a loose joint between a tap and a pipe, will probably reach first for a cloth to put round the joint to catch the water, and then a phone, employing their research skills to find a plumber.

A plumber, however, or someone with some experience of plumbing, is more likely to reach for tools to mend the joint and fix the leak. It’s all a question of orientation.

Problem-Solving

Problem-solving includes four key skills:

- Defining the problem,

- Coming up with alternative solutions,

- Making a decision about which solution to use, and

- Implementing that solution.

Based on this split between orientation and problem-solving, D’Zurilla and colleagues defined two scales to measure both abilities.

They defined two orientation dimensions, positive and negative, and three problem-solving styles, rational, impulsive/careless and avoidance.

They noted that people who were good at orientation were not necessarily good at problem-solving and vice versa, although the two might also go together.

It will probably be obvious from these descriptions that the researchers viewed positive orientation and rational problem-solving as functional behaviours, and defined all the others as dysfunctional, leading to psychological distress.

The skills required for positive problem orientation are:

Being able to see problems as ‘challenges’, or opportunities to gain something, rather than insurmountable difficulties at which it is only possible to fail.

For more about this, see our page on The Importance of Mindset ;

Believing that problems are solvable. While this, too, may be considered an aspect of mindset, it is also important to use techniques of Positive Thinking ;

Believing that you personally are able to solve problems successfully, which is at least in part an aspect of self-confidence.

See our page on Building Confidence for more;

Understanding that solving problems successfully will take time and effort, which may require a certain amount of resilience ; and

Motivating yourself to solve problems immediately, rather than putting them off.

See our pages on Self-Motivation and Time Management for more.

Those who find it harder to develop positive problem orientation tend to view problems as insurmountable obstacles, or a threat to their well-being, doubt their own abilities to solve problems, and become frustrated or upset when they encounter problems.

The skills required for rational problem-solving include:

The ability to gather information and facts, through research. There is more about this on our page on defining and identifying problems ;

The ability to set suitable problem-solving goals. You may find our page on personal goal-setting helpful;

The application of rational thinking to generate possible solutions. You may find some of the ideas on our Creative Thinking page helpful, as well as those on investigating ideas and solutions ;

Good decision-making skills to decide which solution is best. See our page on Decision-Making for more; and

Implementation skills, which include the ability to plan, organise and do. You may find our pages on Action Planning , Project Management and Solution Implementation helpful.

There is more about the rational problem-solving process on our page on Problem-Solving .

Potential Difficulties

Those who struggle to manage rational problem-solving tend to either:

- Rush things without thinking them through properly (the impulsive/careless approach), or

- Avoid them through procrastination, ignoring the problem, or trying to persuade someone else to solve the problem (the avoidance mode).

This ‘ avoidance ’ is not the same as actively and appropriately delegating to someone with the necessary skills (see our page on Delegation Skills for more).

Instead, it is simple ‘buck-passing’, usually characterised by a lack of selection of anyone with the appropriate skills, and/or an attempt to avoid responsibility for the problem.

An Academic Term for a Human Process?

You may be thinking that social problem-solving, and the model described here, sounds like an academic attempt to define very normal human processes. This is probably not an unreasonable summary.

However, breaking a complex process down in this way not only helps academics to study it, but also helps us to develop our skills in a more targeted way. By considering each element of the process separately, we can focus on those that we find most difficult: maximum ‘bang for your buck’, as it were.

Continue to: Decision Making Creative Problem-Solving

See also: What is Empathy? Social Skills

1.2 Defining a Social Problem

Figure 1.2 Sociologist Anna Leon-Guerrero. We use her definition of a social problem.

When you think about the current issues facing our society and our planet, you might name war, addiction, climate change, houselessness, or the global pandemic as social problems. You would be right, sort of. Sociologists need to be more specific than that. Because they are trying to explain what social problems are or how to fix them, they need a much more precise definition. Sociology professor and author Anna Leon-Guerrero (figure 1.2) defines a social problem as “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world.”(2018:4).

More concretely, it is not just that one person gets sick from COVID-19. The social problem is that our healthcare systems are overwhelmed with sick patients. People are experiencing different rates of exposure to COVID-19. Their health outcomes differ because of their race, class, and gender. Because social problems affect people across the social and physical worlds, the solutions to social problems must be collectively created. It is not enough for one person to get well, although that may really matter to you. Instead, we must act collectively, as groups, governments, or systems to identify and implement solutions. Our health is personal, but getting well depends on all of us.

To talk effectively about social problems, we must understand their characteristics. In this text, we will explore five important dimensions of a social problem :

- A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual.

- A social problem results from a conflict in values.

- A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality.

- A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences.

- A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action.

In the following section, we examine each of these five characteristics. Where these characteristics exist, social problems follow. Each component provides an additional layer of explanation about why any human problem is a social problem.

1.2.1 Social Problems: Beyond Individual Experience

Individuals have problems. Social problems, though, go beyond the experience of one individual. They are experienced by groups, nations, or people around the world. An individual experiences job loss, but the wider social problem may be rising unemployment rates. An individual may experience a divorce, but the wider social problem may be changing expectations around marriage and long-term partnerships. Solving a social problem is a collective task, outside of the capability of one individual or group.

Figure 1.3 Sociologist C. Wright Mills, pictured on the left wrote about the Sociological Imagination

In his book The Sociological Imagination , American sociologist C. Wright Mills helps us understand the difference between individual problems and social problems, and connects the two concepts (figure 1.3). Mills (1959) uses the term personal troubles to describe troubles that happen both within and to an individual. He contrasts these personal troubles with social problems, which he calls public issues . Public issues transcend the experience of one individual, impacting groups of people over time.

To illustrate, a recent college graduate may be several hundred thousand dollars in debt because of student loans. They may have trouble paying for living expenses because of this debt. This would be a personal trouble. If we look for larger social patterns, however, we see that as of 2021 about 1 in 8 Americans have student loan debt, owing about 1.6 trillion dollars (Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2021). The volume of this debt, the related laws, policies, and practices, and the harm that is being caused stretch far beyond the experience of a few individuals, resulting in student loan debt becoming a public issue.

In addition to differentiating personal troubles and public issues, Mills also connects them using the sociological imagination , a quality of mind that connects individual experience and wider social forces. He writes, “The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. This is its task and its promise” (Mills 1959:6).

In other words, when we use our own sociological imaginations, we connect our own lives with the experiences of other people. We consider how our own past actions and the historical actions of others may have contributed to our current reality. We use our sociological imaginations to consider what the outcomes of our actions or of social policies might be. When you use your sociological imagination, complicated social problems begin to make sense. When Mills linked personal troubles and public issues, he emphasized that individuals are acted upon by wider social forces.

Figure 1.4 A society consists of more than individual people, just like a forest consists of more than just individual trees: The forest around Cougar Hot Springs, Oregon—More than just individual trees. Tokyo, Japan—More than individual people.

Building on Mills’s concepts, current sociologists highlight the complex relationships of the social world. In the 2019 Society for the Study of Social Problems Presidential Address, Society president Nancy Mezey explores the topic of climate change as a social problem. Understanding and solving climate change requires a deep understanding of the relationship of people and systems. She emphasizes that “society is not just a collection of unrelated individuals, but rather a collection of people who live in relationship with each other” (Mezey 2020: 606). To make this point, she uses the work of sociologist Allan Johnson. In his book The Forest and the Trees, Johnson compares the physical world to our social world:

In one sense, a forest is simply a collection of individual trees, but it is more than that. It is also a collection of trees that exist in particular relation to one another, and you cannot tell what that relation is by looking at the individual trees. Take a thousand trees and scatter them across the Great Plains of North America and all you have is a thousand trees. But take those same trees and put them close together, and now you have a forest. The same individual trees in one case constitute a forest and in another are just a lot of trees. The “empty space” that separates individual trees from one another is not a characteristic of any one tree or the characteristics of all the individual trees somehow added together. It is something more than that, and it is crucial to understand the relationships among trees that make a forest what it is. Paying attention to that “something more” — whether it is a family or a society or the entire world – and how people are related to it lies at the heart of what it means to practice sociology . (Johnson 2014: 11-12, emphasis added)

Using this comparison, Mezey reminds us human society is made up of interdependent individuals, groups, institutions, and systems, similar to the living ecosystem of the forest. This similarity is illustrated in figure 1.4. The reach of a social problem can also be planet-wide. As the response to COVID-19 demonstrates, migrations between countries, vaccination policies and implementations for any nation, and the responses of health systems in local areas can all impact whether any individual is likely to get COVID-19 or to recover from it. A social problem, then, is one that involves a wider scope of groups, institutions, nations, or global populations.

1.2.2 Social Problems: A Conflict in Values

Social problems can also be defined as issues in which social values conflict. A value is an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper. A society may share common values. For example, a society may value universal education, the ideal that all children should learn to read and write or, at minimum, be in school until they are 18. A different society may value practical experience, focusing on teaching children skills related to farming, hunting, or raising children. When core values are shared, there is no basis for conflict.

Social problems may begin to arise if people cannot agree on values. For example, some groups may value business growth and expansion. They oppose restrictions on pollution or emissions because following these regulations would cost money. In contrast, other groups might value sustaining the environment. They support regulations that limit industrial pollution, even when they cost more money. This conflict in values provides a rich soil from which a social problem may grow.

1.2.3 Social Problems: Inequality

A social problem can arise if there is a conflict between a widely shared value and a society’s success in meeting expectations around that value. For example, to sustain life, people need sufficient water, food, and shelter. To work well, a society values human life and creates infrastructure so that all members have water, food, and shelter. However, even at this most basic level, people experience significant inequality in their access to these resources.

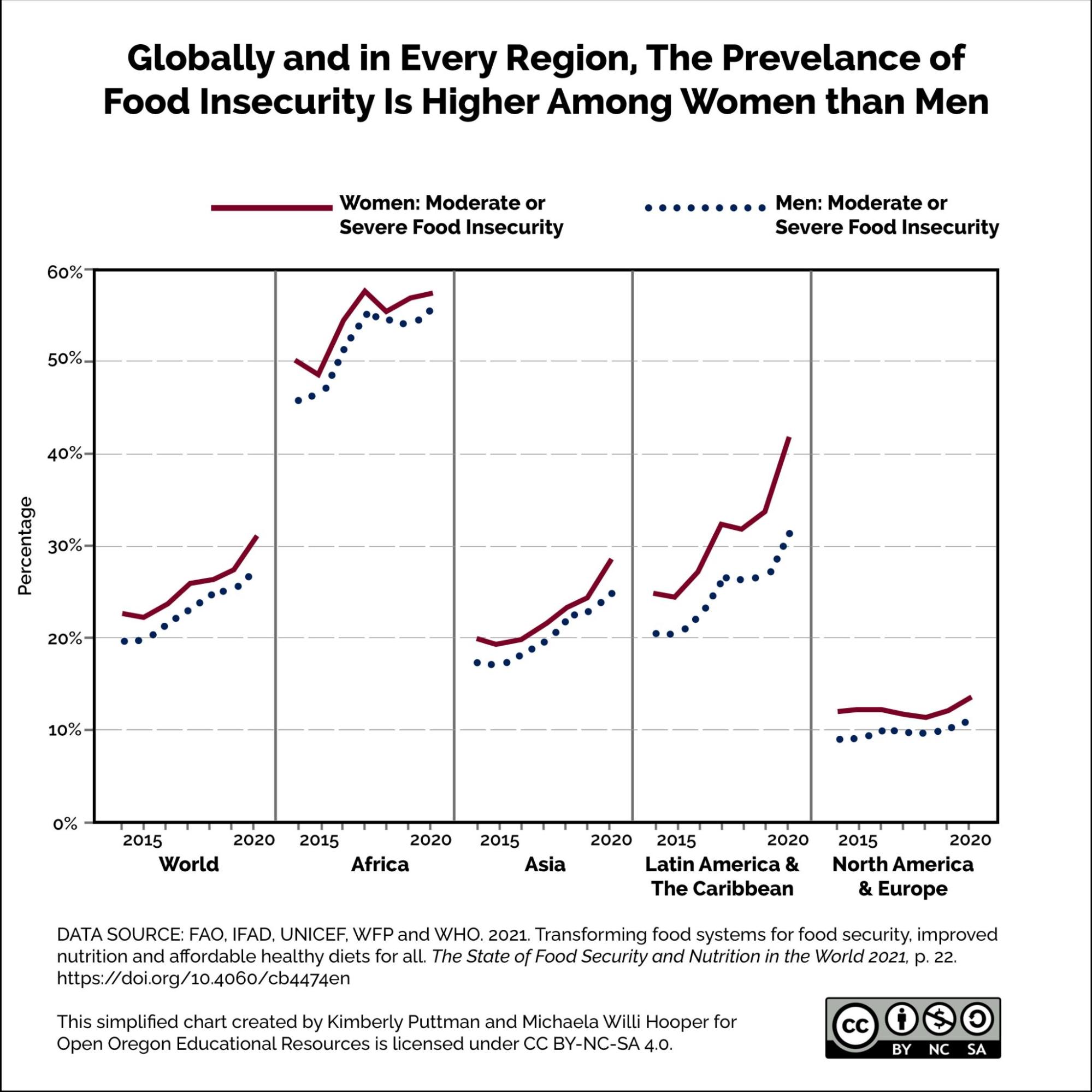

Figure 1.5 In this chart, we see that women experience more food insecurity than men, in every region of the world. In Africa, more than half of all people experience hunger. This rate of food insecurity has also increased around the world between 2015 and 2020. How do you think COVID-19 might have impacted world hunger? Figure 1.5 Image Description

For example, the United Nations reports that one in three people worldwide do not have access to adequate food. That number is rising (United Nations 2020). As we can see in the chart in figure 1.5, women are more likely than men to experience hunger in all regions of the world. The related report also notes that 22 percent of all children worldwide are stunted because they do not have enough to eat (FAO 2021).

In another example at the local level, the Oregon Food Bank explicitly defines hunger as a social problem. They write, “Hunger isn’t just an individual experience; it’s a symptom of barriers to employment, housing, health care and more—and a result of unfair systems that continue to keep these barriers in place” (Oregon Food Bank 2021). In exploring who is hungry in Oregon, they note that communities of color experience greater housing instability and therefore greater food insecurity than White families (Oregon Food Bank 2019). Unequal access and unequal outcomes are both common in our world and fundamental to social problems.

1.2.4 Social Problems: A Social Construction with Real Consequences

Figure 1.6: This 10 minute video on social construction explores what it means to jointly create our social reality. What else do you see that is socially constructed? Note to Reviewers: This 10 minute video on social construction is under construction. The final version will be included with the final version of the book. At the same time, we welcome comments on this draft.

Sociologists delight in statistics, those numbers that measure rates, patterns, and trends. You might think that a social problem exists when things get measurably worse—unemployment rises, food prices increase, deaths from AIDS skyrocket, or gender-related hate crimes explode. Changes in the numbers, or objective measures, provide only part of the story. Sometimes these changes go unnoticed in the wider society and don’t result in conflict or action. Other times a local community takes action, but another local community with similar statistics does not.

To explain this difference, we turn to the fundamental sociological concept of social construction , the idea that we create meaning through interaction with others. This concept asserts that while material objects and biological processes exist, it is the meaning that we give to them that creates our shared social reality. The video in figure 1.6 provides more examples of this concept.

The term social construction was used in 1966 by sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann. They wrote a book called The Social Construction of Reality . In it, they argued that society is created by humans and human interaction. These interactions are often habits. They use the term habitualization to describe how “any action that is repeated frequently becomes cast into a pattern, which can then be … performed again in the future in the same manner and with the same economical effort” (Berger and Luckmann 1966). Not only do we construct our own society but we also accept it as it is because others have created it before us. Society is, in fact, habit .

For example, a school building exists as a school and not as a generic building because you and others agree that it is a school. If your school is older than you are, it was created by the agreement of others before you. In a sense, it exists by consensus, both prior and current. This is an example of the process of institutionalization, the act of implanting a convention or social expectation into society. By employing the convention of naming a building as a school , the institution, while socially constructed, is made real and assigned specific expectations as to how it will be used.

Another way of looking at the social construction of reality is through an idea developed by American sociologist W. I. Thomas. The Thomas theorem states, “If [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas 1928). In other words, people’s behavior can be determined by their subjective construction of reality rather than by objective reality. For example, a teenager who is repeatedly given a label—rebellious, emo, goth—often lives up to the term even though it initially wasn’t a part of their character.

Figure 1.7 What do you think the person in the photo, gesturing “Thumbs up” is trying to say? Depending on his country, he may be saying great , on e, or five . Even our gestures are socially constructed.

Sociologists who study how we interact also recognize that language and body language reflect our values. One has only to learn a foreign language to know that not every English word can be easily translated into another language. The same is true for gestures. What does the gesture in figure 1.7 mean? While Americans might recognize a thumbs-up as meaning great , in Germany it would mean one , and in Japan, it would mean five . Thus, our construction of reality is influenced by our symbolic interactions. When we apply this idea of the social construction of reality to social problems, then, we say that a social problem only exists when people say they have one.

Figure 1.8 In this picture of social protest, the protester is holding a sign “Whatever we wear, wherever we go, Yes means Yes and No means No” Over time our ideas about bodily autonomy, consent, and gender based violence are changing.

Let’s look at the crime of rape to understand this concept more clearly. Initially, rape was defined as a property crime. This view of women’s bodies is profoundly disturbing to us today but was common in seventeenth-century English law. Legally, women were considered the property of their fathers or their husbands. Therefore, rape was legally understood as decreasing the value of their property. Taking this model further, married women could not be raped by their husbands because consent was implied as part of the marriage contract.

When feminists in the 1970s challenged this legal definition, laws related to rape began to change. Rape, which included marital rape, became defined as a crime of violence and social control against an individual person (Rose 1977). In a more recent study, researchers examined how rape was defined in a college community between 1955 and 1990. Early descriptions of rape in school and community newspapers painted the picture that White women students were safe on campus. If they ventured beyond campus to predominantly Black neighborhoods, they risked being raped. Rape was considered a crime committed by a racialized other, a Black or Brown stranger rather than a member of a White student community. This perspective saw police as responsible for keeping women safe (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020).

With the work of feminist activists, the concept of rape and the response to rape changed. In the 1970s and 1980s, women’s centers and health professionals defined rape as an act of sexual violence that supported the structural power of men and an issue that threatened women’s health. The person who experienced rape began to be called a survivor rather than a victim . Men who raped or committed other kinds of sexual harassment could be identified as part of the campus community rather than being defined as a stranger or an outsider. The changes in the social construction of rape allowed for more effective community responses in preventing rape, prosecuting rape, and supporting the healing of rape survivors (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020).

Feminist activists continue this work. Black activist Tarana Burke founded the #MeToo movement in 2006 so that survivors of sexual violence could tell their stories. These stories highlight how common sexual violence is for women, men, and nonbinary people. It expands our conversation about rape to a wider discussion around the causes and consequences of sexual violence. If you would like to learn more about #MeToo from Burke herself, please watch this TED Talk, “ Me Too Is a Movement, Not a Moment .” Actor Alyssa Milano drew attention to this movement when she tweeted #MeToo in 2017. This movement has resulted in some changes in the law (Beitsch 2018) and in stronger prosecution of perpetrators of sexual violence, in some cases (Carlsen et al. 2018).

In this constructionist view, the definition of rape, the actors in the crime, and the responsibility for fixing the problem changed over time, with significant consequences to the people involved. Even concepts like consent, active agreement to sexual activity (see figure 1.8), are taught and learned. A Cup of Tea and Consent [YouTube] teaches the concept (some explicit language). We will see the usefulness of the social construction of a social problem as we explore each social problem raised in this book.

1.2.5 Social Problems: Interdependent Solutions of Individual Agency and Collective Action

All life is interelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. We are made to live together because of the interrelated structure of reality. This is the way our universe is structured, this is its interrelated quality. We aren’t going to have peace on earth until we recognize this basic fact of the interrelated structure of all reality.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., activist, sociologist, and minister

Figure 1.9 Video: Martin Luther King Jr. A Christmas Speech: . Martin Luther King Jr. asserts that we are all interrelated, another word for interdependence in his Christmas Speech from 1967. While watching the whole speech is optional, you may want to view from minutes 7:10-7:12 to listen to the quote that begins this section.

Our diversity can be a source of innovative solutions to social problems. At the same time, the ways in which we are different divide us. We see bullying, hate crimes, war, gender based violence, and other patterns of treating each other differently based on our social location. At the same time, many of us go to school, raise families, live in neighborhoods, and die of old age. How is it that we are able to maintain our sense of community?

We begin to answer this question by reminding ourselves that the sociological imagination helps us see that there are wider social forces at play in our individual lives. Interdependence is the concept that people rely on each other to survive and thrive (Schwalbe 2018). Martin Luther King Jr. asserts that we are all interrelated, another word for interdependence, in his Christmas Speech from 1967 in figure 1.9. While watching the whole speech is optional, you may want to view from minutes 7:10-7:12 to listen to the quote that begins this section.

Interdependence is everywhere, but specific examples of social, economic, and physical interdependence may help us see it more clearly. With social interdependence, we rely on other people to cooperate to support our life. We give the same cooperation to others in turn. For example, when you consider your own life, you might notice how many people helped you become the person you are. When you were very young, you relied on a parent or caregivers to feed you, to clothe you, to keep you warm, and maybe to read you bedtime stories. As we widen this picture, we see that your caregivers relied on store owners and doctors, farmers and truckers, business people, and friends to support the work of caring for you. You may not have had a happy life, yet you lived long enough to read these words. This book was brought to you by authors, editors, artists, videographers, designers, musicians, librarians, and other students like you. These relationships demonstrate our social interdependence.

In addition to social interdependence, we experience economic interdependence. As we shop for groceries this week, we see empty shelves and rising food prices. COVID-19 is disrupting the global supply chain. Farmers growing oranges in Mexico can’t find laborers to pick the fruit. U.S. car manufacturers can’t get electronic chips manufactured in China. Even when people in Vietnam sew T-shirts or factory workers in Korea build TVs, the ships that carry these products from one country to another wait for dock workers to unload them. Our experiences with COVID-19 underline the truth of our economic interdependence.

We express this economic interdependence in relationships that describe the power of workers and the power of business owners. In 2017, Francis Fox Piven, the president of the American Sociological Association, defined interdependent power, arguing that while wealth and privilege create power, workers, tenants, and voters also have the power of participation. We see interdependent power today in the Great Resignation, with people deciding to resign from their jobs rather than return to work. We see it in restaurants reducing hours or closing down because they can’t find workers to wait tables and bus dishes. We see this in frontline workers becoming even more critical in providing basic services to a quarantined public. We live in a globally interdependent economy.

Finally, and maybe foundationally, we are physically interdependent. I remember being on a boat in a glacial lake in Alaska. The tour guide, a biologist, was asking the people on the tour about how many oceans there were in the world. All of us were desperately trying to remember fifth-grade geography, and counting the various oceans we remembered. Atlantic, Pacific, Indian . . . wait did the Arctic and Antarctic count as oceans? Maybe five? Maybe six? Maybe seven? At each answer, the biologist shook her head, “No.” We were stumped.

Figure 1.10 The Pacific Ocean at Lincoln City, Oregon, or maybe just one view of our planet’s one ocean.

She revealed that scientists who study the ocean now say that we have just one ocean (even though the ocean in figure 1.10 happens to be the Pacific Ocean, a few blocks from my house). It contains all the ocean water across our entire planet. Debris from a tsunami in Japan washed up on beaches from the tip of Alaska to the Baja peninsula and Hawaii. Rivers contribute up to 80 percent of the plastics pollution found in the ocean. We see that the COVID-19 virus travels with people around the world as infections move from place to place. As we cross the globe on our feet, bikes, camels, trains, cars, and airplanes, our diseases travel with us. We are physically interdependent.

Figure 1.11 When do we comply with the social norms of mask-wearing and elbow bumping?

Each of these ways of considering our interdependence matters when it comes to studying social problems and creating change. Because our actions affect one another, any social problem or solution ripples through our social world. For example, social scientists are examining mask-wearing during COVID-19.

In the video “ The Importance of Social Norms” (episode 8 on the website) , researcher Dr. Vera te Velde from the University of Queensland explores mask-wearing behavior around the world. She wanted to find out what would make mask wearing a social norm. Social norms are the rules or expectations that determine and regulate appropriate behavior within a culture, group, or society.

Dr. de Velde finds that when people trust each other and their government, they are much more likely to wear masks. Trust and shared agreement around social norms encourage consistent behavior. In other words, when we notice our interdependence and trust that others will follow social norms, we are more likely to follow them too. Sociologist Michael Schwalbe, in The Sociologically Examined Life, calls this mindfulness of interdependence. When we are aware, or mindful, of how our actions impact others, we are noticing our interdependence. We then often act for the good of all.

The interdependent nature of social problems also requires interdependent solutions. For this, we look at individual agency and collective action. The discipline of sociology always asks why? , but the sociologists who study social problems are particularly committed to taking action. They try to understand why a problem occurs to inform policy decisions, create community coalitions, or support healthy families. In the best cases, they seek to know their own biases and work to remediate them, so their research is used to create change. This challenge is explicitly stated by SSSP President Mezey:

The theme for the 2019 SSSP [Society for the Study of Social Problems] meeting is a call to sociologists and social scientists in general to draw deeply and widely on sociological roots to illuminate the social in all social problems with an eye to solving those problems. The theme calls us to speak broadly and widely, so that our discipline becomes a central voice in larger public discourses. I am calling on you, the reader, through this presidential address to focus on what is perhaps the largest social problem: climate change. Indeed, because we have been focusing on individual rather than social solutions regarding climate change—we are now facing grave and imminent danger. (Mezey 2020:606)

Society president Mezey tells us that studying problems is not enough. We must focus on the most critical social problem—climate change, to support all of us in taking action.

Addressing social problems requires individuals to act. Social agency is the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change. In other words, any individual can choose to vote, to protest, to parent well, or to be authentic about who they are in the world. Each act of positive social agency matters to that person and their community, even if the small waves of change are hard to see in the wider world.

Collective action refers to the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision. whose goal is to enhance their condition and achieve a common objective (Sekiwu and Okan 2022). These kinds of actions people take are creative responses to local issues. We typically think of collective action as a protest march or a social movement. Collective action can also be setting up the Salmon River Grange as the distribution center for food, clothes, and pizza for survivors of the Echo Mountain Fire. It could also be reinvigorating an Indigenous language or connecting businesses and nonprofits so you can provide digital literacy skills training. People, communities, and organizations imagine the future they want to see, and take organized action to make it happen.

To confront the social problems of our world, we need a both/and approach to their resolution. We act with individual agency to create a life that is healthy and nurturing and we act collectively to address interdependent issues.

1.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Defining a Social Problem

1.2.6.1 open content, shared previously.

“Social Construction of Reality” is adapted from “ Social Construction of Reality ” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e , Openstax , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social problems. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

Figure 1.3. “ Sociologist C Wright Mills ” by Institute for Policy Studies is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Figure 1.4a. Photo by Deric is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.4b. Photo by Chris Chan is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.7. Photo by Aziz Acharki is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.8. Photo by Raquel García is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.11. Photo by Maxime is licensed under the Unsplash License .

1.2.6.2 All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.2. “ Anna Leon-Guerrero ” © Pacific Lutheran University is included under fair use.

Figure 1.9 “ Martin Luther King, Jr., Christmas Sermon ” by Mapping Minds is licensed under the Standard YouTube License .

1.2.6.3 Open Content, Original

“Defining a Social Problem” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 1.5. “Chart of World Hunger” by Kim Puttman and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 1.6. “ Social Construction Video (Draft) ” by Liz Pearce, Kim Puttman and Colin Stapp, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 1.10. Photo by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Image Description for Figure 1.5:

Globally, and in every region, the prevalence of food insecurity is higher among women than men

A line chart shows moderate or severe food insecurity for both women and men in different regions of the world from 2015 to 2020. The lines are often close, but women are always more food insecure than men. Throughout the world, food insecurity has risen for both women and men (from around 20% in 2015 to over 30% for women in 2020). The two lines diverge the most for Latin America and the Caribbean, where food insecurity went from approximately 25% in 2015 to over 40% in 2020. Food insecurity rates for both men and women are highest in Africa (almost 60% for both men and women in 2020) and lowest in North America (between 10 and 15% in 2020).

Data source: State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021, prepared by FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO.

This simplified version created by Michaela Willi Hooper and Kimberly Puttman and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

[Return to Figure 1.5]

Social Problems Copyright © by Kim Puttman. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Skip to main content

Teaching SEL

Social Emotional Learning Lessons for Teachers and Counselors

Social Decision Making and Problem Solving

Enhancing social-emotional skills and academic performance.

The approach known as Social Decision Making and Social Problem Solving (SDM/SPS) has been utilized since the late 1970s to promote the development of social-emotional skills in students, which is now also being applied in academic settings. This approach is rooted in the work of John Dewey (1933) and has been extensively studied and implemented by Rutgers University in collaboration with teachers, administrators, and parents in public schools in New Jersey over several decades.

SDM/SPS focuses on developing a set of skills related to social competence, peer acceptance, self-management, social awareness, group participation, and critical thinking.

The curriculum units are structured around systematic skill-building procedures, which include the following components:

- Introducing the skill concept and motivation for learning; presentation of the skill in concrete behavioral components

- Modeling behavioral components and clarifying the concept by descriptions and behavioral examples of not using the skill

- Offering opportunities for practice of the skill in “student-tested,” enjoyable activities, providing corrective feedback and reinforcement until skill mastery is approached

- Labeling the skill with a prompt or cue, to establish a “shared language” that can be used for future situations

- Assigning skill practice outside of structured lessons

- Providing follow-through activities and integrating prompts in academic content areas and everyday interpersonal situations

Connection to Academics

Integrating SDM/SPS into students’ academic work enhances their social-emotional skills while enriching their academic performance. Research consistently supports the benefits of social-emotional learning (SEL) instruction.

Readiness for Decision Making

This aspect of SDM/SPS targets the development of skills necessary for effective social decision making and interpersonal behavior across various contexts. It encompasses self-management and social awareness. A self-management unit focuses on skills such as listening, following directions, remembering, taking turns, and maintaining composure in the classroom. These skills help students regulate their emotions, control impulsivity, and develop social literacy. Students learn to recognize physical cues and situations that may trigger high-arousal, fight-or-flight reactions or dysregulated behavior. Skills taught in this domain should include strategies to regain control and engage clear thinking, such as breathing exercises, mindfulness, or techniques that activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

A social awareness unit emphasizes positive peer relationships and the skills necessary for building healthy connections. Students learn to respond positively to peers who offer praise, compliments, and express positive emotions and appreciation. Skills in this unit also include recognizing when peers need help, understanding when they should seek help from others, and learning how to ask for help themselves. Students should develop the ability to provide and receive constructive criticism and collaborate effectively with diverse peers in group settings.

Decision Making Framework – FIG TESPN

To equip students with a problem-solving framework, SDM/SPS introduces the acronym FIG TESPN. This framework guides students when faced with problems or decisions and aims to help them internalize responsible decision making. The goal is for students to apply this framework academically and personally, even in challenging and stressful situations.

FIG TESPN stands for:

- (F)eelings are my cue to problem solve.

- (I) have a problem.

- (G)oals guide my actions.

- (T)hink of many possible things to do.

- (E)nvision the outcomes of each solution.

- (S)elect your best solution, based on your goal.

- (P)lan, practice, anticipate pitfalls, and pursue your best solution.

- (N)ext time, what will you do – the same thing or something different?

Integration of FIG TESPN into academics

Once students have become familiar with the FIG TESPN framework, there are limitless opportunities for them to apply and practice these skills. Many of the texts students read involve characters who make decisions, face conflicts, deal with intense emotions, and navigate complex interpersonal situations. By applying the readiness skills and FIG TESPN framework to these assignments, students can meet both academic and social-emotional learning (SEL) state standards.

Teachers and staff play a crucial role in modeling readiness skills and the use of FIG TESPN. They can incorporate these skills into their questioning techniques, encouraging individual students and groups to think critically when confronted with problems. This approach helps students internalize the problem-solving framework and develop their decision-making abilities.

By integrating social decision making and problem-solving skills into academic subjects such as social studies, social justice, ethics, and creative writing, students gain a deeper understanding of the FIG TESPN framework. The framework becomes an integral part of their learning experience and supports their growth in both academic and social-emotional domains.

SDM/SPS Applied to Literature Analysis

- Think of an event in the section of the book assigned. When and where did it happen? Put the event into words as a problem.

- Who were the people that were involved in the problem? What were their different feelings and points of view about the problem? Why did they feel as they did? Try to put their goals into words.

- For each person or group of people, what are some different decisions or solutions to the problem that he,she, or they thought of that might help in reaching their goals?

- For each of these ideas or options, what are all of the things that might happen next? Envision and write both short- and long-term consequences.

- What were the final decisions? How were they made? By whom? Why? Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- How was the solution carried out? What was the plan? What obstacles were met? How well was the problem solved? What did you read that supports your point of view?

- Notice what happened and rethink it. What would you have chosen to do? Why?

- What questions do you have, based on what you read? What questions would you like to be able to ask one or more of the characters? The author? Why are these questions important to you?

a simplified version…

- I will write about this character…

- My character’s problem is…

- How did your character get into this problem?

- How does the character feel?

- What does the character want to happen?

- What questions would you like to be able to ask the character you picked, one of the other characters, or the author?

SDM/SPS Applied to Social Studies

- What is the event that you are thinking about? When and where is it happening? Put the event into words as a problem, choice, or decision.

- What people or groups were involved in the problem? What are their different feelings? What are their points of view about the problem?

- What do each of these people or groups want to have happen? Try to put their goals into words.

- For each person or group, name some different options or solutions to the problem that they think might help them reach their goals. Add any ideas that you think might help them that they might not have thought of.

- For each option or solution you listed, picture all the things that might happen next. Envision long- and short-term consequences.

- What do you think the final decision should be? How should it be made? By whom? Why?

- Imagine a plan to help you carry out your solution. What could you do or think of to make your solution work? What obstacles or roadblocks might keep your solution from working? Who might disagree with your ideas? Why? What else could you do?

- Rethink it. Is there another way of looking at the problem that might be better? Are there other groups, goals, or plans that come to mind?

Applying FIG TESPN to Emigration

- What countries were they leaving?

- How did they feel about leaving their countries?

- What problems were going on that made them want to leave?

- What problems would leaving the country bring about?

- What would have been their goals in leaving or staying?

- What were their options and how did they envision the results of each possibility?

- What plans did they have to make? What kinds of things got in their way at the last minute? How did they overcome the roadblocks?

- Once they arrived in a new country, how did they feel? What problems did they encounter at the beginning? What were their first goals?

Adapted from: Fostering Social-Emotional Learning in the Classroom

Social Skills Training for Adults: 10 Best Activities + PDF

Struggles with social skills in adulthood can cause avoidance of social situations and interfere with building long-lasting relationships.

Providing social skills training to clients with anxiety, fear of public speaking, and similar issues could ensure more optimal functioning.

This article provides strategies and training options for the development of various social skills. Several resources to help target specific struggles related to the development of social skills in adults are also included, and the approaches can be tailored to improve social responses in specific domains.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Social skills training for adults explained, social skills coaching: 2 best activities, role-playing exercises: 4 scripts & examples, top 2 resources & worksheets, 4 insightful videos & podcasts, positivepsychology.com’s helpful tools, a take-home message.

Social skills training includes interventions and instructional methods that help an individual improve and understand social behavior. The goal of social skills training is to teach people about verbal and nonverbal behaviors that are involved in typical social interactions (“Social,” n.d.).

Social skills training is usually initiated when adults have not learned or been taught appropriate interpersonal skills or have trouble reading subtle cues in social interactions. These instances can also be associated with disorders that impede social development, such as autism.

Therapists who practice social skills training first focus on breaking down more complex social behaviors into smaller portions. Next, they develop an individualized program for patients, depending on what social skills they need to work on, and gradually introduce those skills to their patients, building up their confidence through gradual exposure.

For instance, a person who has trouble making eye contact because of anxiety in social situations might be given strategies to maintain eye contact by the therapist. Eye contact is the foundation for most social interaction, and interventions will often start with improving the individual’s ability to maintain eye contact.

During therapy, other challenging areas will be identified such as starting or maintaining a conversation or asking questions. Each session will focus on different activities that typically involve role-play and sometimes will take place in a group setting to simulate different social experiences.

Once confidence has been built up during therapy or social skills group settings, these social skills can be brought into daily life.

Useful assessments: Tests, checklists, questionnaires, & scales

Before engaging your clients in social skills interventions or any type of therapeutic intervention, it is important to determine if social skills therapy is a good approach to help them with their current situation.

The Is Social Skills Training Right for Me? checklist is a self-assessment opportunity for clients to determine if social skills therapy is appropriate for their specific situation or if another approach will be more beneficial.

However, self-assessment activities can sometimes be unreliable, as the individual might not fully understand the treatment models that are available to them. Additionally, if a client has issues with social skills, they may not be aware of their deficiencies in social situations.

In these situations, therapists should ask clients about the issues they are having and encourage them to engage in self-questioning during sessions.

9 Questions to ask your clients

Prior to starting social skills training or activities, the therapist and client should narrow down which areas need help. A therapist can do this by asking the client a series of questions, including:

- Where do you think you are struggling?

- Are there any social situations that make you feel anxious, upset, or nervous?

- Do you avoid any specific social situations or actions?

- Have you ever had anyone comment on your social behavior? What have they said?

- What do you think will help you improve the skills you are struggling with?

Clients can also ask themselves some questions to determine if the social skills therapy process is right for them.

These questions can include:

- What aspects of my life am I struggling with?

- Are there specific social situations or skills that I struggle with?

- Do I have trouble keeping or maintaining relationships with friends, family members, and coworkers?

- Am I avoiding specific social situations out of fear?

Getting clients to ask these questions will help determine if this process will benefit them. Having clients “buy in” to the process is important, to ensure that the approach is right for them and increase the likelihood that they will be engaged to complete activities with a reasonable degree of efficacy.

It is estimated that adults make eye contact 30–60% of the time in general conversation, increasing to 60–70% of the time when trying to form a more intimate relationship (Cognitive Development Learning Centre, 2019).

Giving people who are struggling socially the tools to make more eye contact is usually the first step in social skills training exercises.

The Strategies for Maintaining Eye Contact worksheet provides some practical strategies and tips to practice making eye contact.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Often, one of the most prominent struggles for people lacking social skills is starting a conversation, especially with people they are not familiar with.

Fleming (2013) details a helpful method for people who struggle with starting conversations. The ARE method can be used to initiate a conversation and gain an understanding of the person’s interests to facilitate a strong relationship.

- Anchor: Connect the conversation to your mutually shared reality (e.g., common interests) or the setting in which you encountered the individual.

- Reveal: Provide some personal context to help deepen the connection between you and the other person.

- Encourage: After giving them some context, provide the other person with positive reinforcement to encourage them to share.

This worksheet Starting a Conversation – The ARE Method guides participants through each step in the ARE process. It also provides examples of how the ARE method can be incorporated into a typical conversation and used as a workable strategy in social skills training activities.

A Guide to Small Talk: Conversation Starters and Replies provides an outline of conversation ideas to help start any conversation, no matter the setting.

After developing the ability to start a conversation, being able to project assertiveness and understand one’s limits is essential in ensuring clear communication.

These worksheets on Different Ways to Say ‘No’ Politely and Using ‘I’ Statements in Conversation facilitate assertive communication and give clients the confidence to set personal limits.

A lack of opportunity to learn coping strategies and difficulty with emotional regulation have been associated with anxiety and low problem-solving abilities (Anderson & Kazantzis, 2008).

An individual’s lack of ability to problem solve in social situations significantly affects their ability to come up with reasonable solutions to typical social problems, which in turn, causes them to avoid more difficult social situations.

Practicing social problem solving is a key component of social skills training. This worksheet on Social Problem Solving allows your clients to define the problems they are facing and rate the potential solutions from low to high efficacy.

Based on the rating, therapists can instruct clients to practice their social reasoning during sessions. Practicing these skills builds clients’ confidence and increases the likelihood that they will access these solutions under pressure.

Similarly, the Imagining Solutions to Social Problems worksheet implements a related process, but challenges participants to engage in a visualization activity. While engaging in visualization, participants have the opportunity to imagine what they would say or do, and reflect on what they have learned and why the solution they chose was best for that particular problem.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Supplementing modeling and practical activities with interactive audio-visual aids, such as podcasts and videos, is an essential practice in ensuring that patients seeking social skills training are getting multiple perspectives to develop their social intelligence.

Below, we have provided resources to help your clients with different social skills and situations.

An introvert’s guide to social freedom – Kaspars Breidaks

This TEDx talk focuses on providing guidelines for self-identified introverts. In this video, Breidaks frames introversion as an opportunity, rather than a weakness.

Based on his experiences moving from a small town to a big city and eventually starting improv comedy, he developed a workshop to help integrate principles of improvisation into social skills training.

His workshops focus on creating connections through eye contact and breaking through shyness by training the small talk muscle. Because of his experience, he recommends you say yes to yourself before saying yes to others. Breidaks theorizes that only by developing our awareness of our own true emotions and thoughts can we become more comfortable interacting with others.

This video is helpful if your patients need workable tips to improve their interactions with strangers and is an excellent complement to some of our worksheets on developing skills for small talk.

10 Ways to have a better conversation – Celeste Headlee

This TEDx talk is focused on tactics to have more effective conversations. In her TED talk, Headlee emphasizes the importance of honesty, clarity, and listening to others as well as yourself.

Headlee shares her ideas about how to talk and listen to others, specifically focusing on sustaining clear, coherent conversation and the importance of clear, direct communication.

She argues that technology has interfered with the development of interpersonal skills, stating that conversation is an art that is fundamentally underrated and should be emphasized more, especially among young children.

The main point Headlee tries to get across is to avoid multitasking and pontificating during conversation. Individuals who are struggling with active listening and keeping a conversation going would benefit from the tips she offers in this video, as she uses a lot of the same principles when interviewing her radio guests to ensure that she is getting the most out of their appearances.

She specifically emphasizes the importance of being continually present while talking and listening to someone, which is strongly emphasized in social skills training.

How Can I Say This – Beth Buelow

Each episode also provides techniques or approaches to help listeners become more confident when dealing with different social situations. The podcast also takes listener questions about dealing with social situations and issues.

If your clients are struggling with introducing themselves to new people, they may benefit from the episodes on talking to strangers and how to have difficult conversations.

Available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts .

Social Skills Coaching – Patrick King

King focuses on using emotional intelligence and understanding human interaction to help break down emotional barriers, improve listeners’ confidence, and equip people with the tools they need for success.

Although King’s expertise is centered on romantic relationships, this podcast provides strategies to improve one’s emotional awareness and engage in better communication.

People engaging in social skills training would benefit from the episode on social sensitivity, which examines the social dynamics of the brain. It also explains why our brains are programmed to respond more to specific traits (e.g., warmth, dominance) and why people with those traits are often elevated to higher positions within the social hierarchy.

Available on Apple Podcasts .

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

There are several resources available on our website to complement the social skills training that you are providing to your clients.

Our Emotional Intelligence Masterclass© trains helping professionals in methodology that helps increase their client’s emotional intelligence.

The client workbook has several exercises that practitioners can give their clients to develop an awareness of their emotions and, subsequently, understand how those emotions might contribute to interactions with others.

Our Positive Psychology Toolkit© provides over 400 exercises and tools, and the Social Network Investment exercise, included in the Toolkit, focuses on reflecting on a client’s current social network. By further looking into the amount of time and investment devoted to the members of their social network, clients can further identify who is supportive of their endeavors and who negatively affects experiences.

With this knowledge, relationships can be analyzed before devoting even more time and investment that might not facilitate positive emotions.

People who struggle with initiating conversation might also have trouble talking about their emotions. Our exercise on Asking for Support , also in the Toolkit, can provide assistance to someone having trouble communicating their emotions.

It also provides strategies to practice asking for help when needed. This exercise also gives you the opportunity to identify any personal barriers that are impending your ability to seek help from others.

You might be interested in this sister article, Social Skills Training for Kids , which provides top resources for teachers.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

Improving social skills is an important skill to develop for anyone trying to facilitate professional and personal connections.

However, sometimes clients might not even realize they need targeted interventions to help with their social skills, and they might approach a therapist with other challenges around anxiety entering new situations.

For that reason, we hope this article provided valuable options for the development of social skills, with useful activities and social skills worksheets to be incorporated into your sessions.

We encourage you and your clients to explore these exercises together and engage in goal-setting tools to target areas that will benefit their daily lives, relationships, and communication.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Anderson, G., & Kazantzis, N. (2008). Social problem-solving skills for adults with mild intellectual disability: A multiple case study. Behaviour Change , 25 (2), 97–108.

- Cognitive Development Learning Centre. (2019). Training eye contact in communication . Retrieved May 4, 2021, from https://cognitive.com.sg/training-eye-contact-in-communication/

- Fleming, C. (2013). It’s the way you say it: Becoming articulate, well-spoken and clear (2nd ed.). Berrett-Koehler.

- Social skills training. (n.d.). In Encyclopedia of mental disorder. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from http://www.minddisorders.com/Py-Z/Social-skills-training.html

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Hello, I am trying to open the link to the ARE-method but am unable to.

Please try to access the worksheet here .

If you experience further issues with accessing the link, please let me know!

Warm regards, Julia | Community Manager

Sounds so good for my young adult. Do you know of any in person sessions, workshops, which would benefit him being in person.

I would like to know what the best book to get for my husband for him to learn social skills conversations. Thank You

check out our article “ 12 Must-Read Social Skills Books for Adults & Kids “.

Hope this helps!

Kind regards, Julia | Community Manager

Are there any online classes for people suffering with anxiety, Aspergers and a lack of social skills? This is a great article, but there are no therapists who teach social skills. These are skills that come from parents. Like me, when you have no parent or friends to teach you, what do you do? Please make an online course. I would pay to watch a course and even buy materials.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment and interest in an online course addressing anxiety, Aspergers, and social skills. I understand how challenging it can be to find the right resources, especially when traditional sources of support may not be readily available.

While we don’t currently offer an online course, we are happy to recommend a helpful resource that cater to individuals experiencing similar difficulties: Psychology Today has a great directory you can use to find therapists in your local area. Usually, the therapists provide a summary in their profile with their areas of expertise and types of issues they are used to working with.

I hope this helps.

Hello, I just found out about this website today and this is the exact type of service I need. I unfortunately cannot find any one like this that is near me or accept my insurance. And I need this fast since my quality of life is so bad, I have severe social anxiety, and never had friends or a relationship.

Hi there a lot of the links don’t work in this article? How can I access the resources?

Thanks for your question! We are working on updating all the broken links in our articles, as they can be outdated. Which specific resource are you looking for?

Maybe I can help 🙂

Kind regards, -Caroline | Community Manager

Living socially isolated, getting told I have autism ad the age of 33, I found out that I have a lot to learn about being social with people. Now knowing what my “ problem” is also gave me the drive to improve my people skills. Fearing I willing never fully understand feelings ( not even my own) all help is welcome. And this was a very helpful article. Living in a world with tips and tricks to look normal will never be easy. But you sure help me .. thank you..

AMAZING work.. .as always. Thank you !

Thank you Gabriella social skills have been a real issue for me for my whole life. There are so many helpful avenues to explore thanks this article.

Steven Cronson My brothers didn’t consider me an Aspie and made a pact to ignore me , block me I hadn’t even learned many social skills my brother a psychiatrist tried by giving me ptsd and gad a Divorce to try to get me to end my life. My wife proudly fought back and figured out how better to understand me. And I fought the awful had medicine Lexapro that I consider the devil in a pill that made me flat and losing my superpower focusing ability. I hope a producer latched on to my fascinating story of greed, over good, attack on my very life and a brother doctor that should never been one. My dad a psychiatrist made me a DDS to be respected and listened to but not even work and married off in a fake but better life. They accused me an Aspie blind to empathy. B

I’m sorry to read about your challenges with your family. It’s good that you have what sounds like a supportive ally in your wife. And indeed, medications don’t work for everyone — or it may be the case that a different medication may suit you better. Definitely raise these concerns with a trusted psychiatrist if you feel medication could help you.

As you note, it’s a harmful myth that those on the autism spectrum don’t feel empathy. And this myth unfairly stigmatises members of this community. I’m sorry to read about these accusations from your family.

On another note, if you’d like to work on your social skills, consider reaching out to support groups for those with Aspergers in your area, or seeking the support of a therapist with expertise in this area. Psychology Today has a great directory you can use to find therapists in your local area. Usually, the therapists provide a summary in their profile with their areas of expertise and types of issues they are used to working with.

I hope this helps, and I wish you all the best.

– Nicole | Community manager

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Ensuring Student Success: 7 Tools to Help Students Excel

Ensuring student success requires a multi-faceted approach, incorporating tools like personalized learning plans, effective time management strategies, and emotional support systems. By leveraging technology and [...]

EMDR Training & 6 Best Certification Programs

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy has gained significant recognition for its effectiveness in treating trauma-related conditions and other mental health issues (Oren & [...]

Learning Disabilities: 9 Types, Symptoms & Tests

Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, Sylvester Stalone, Thomas Edison, and Keanu Reeves. What do all of these individuals have in common? They have all been diagnosed [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

Download 3 Free Positive Education Exercises Pack (PDF)

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

- Creating Environments Conducive to Social Interaction

- Thinking Ethically: A Framework for Moral Decision Making

- Developing a Positive Climate with Trust and Respect

- Developing Self-Esteem, Confidence, Resiliency, and Mindset

- Developing Ability to Consider Different Perspectives

- Developing Tools and Techniques Useful in Social Problem-Solving

- Leadership Problem-Solving Model

- A Problem-Solving Model for Improving Student Achievement

- Six-Step Problem-Solving Model

- Hurson’s Productive Thinking Model: Solving Problems Creatively

- The Power of Storytelling and Play

- Creative Documentation & Assessment

- Materials for Use in Creating “Third Party” Solution Scenarios

- Resources for Connecting Schools to Communities

- Resources for Enabling Students

This is the home page for socialproblemsolving.com!

- DOI: 10.1037/10805-000

- Corpus ID: 142742173

Social problem solving: Theory, research, and training.

- E. Chang , T. D'Zurilla , L. Sanna

- Published 2004

253 Citations

Social problem-solving and depressive symptom vulnerability: the importance of real-life problem-solving performance, problem solving and behavior therapy revisited, social problem-solving processes and mood in college students: an examination of self-report and performance-based approaches, competencies for complexity: problem solving in the twenty-first century, thinking about the consequences: the detrimental role of future thinking on intrapersonal problem-solving in depression, longitudinal associations between psychological capital and problem-solving among social workers: a two-wave cross-lagged study., problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis., analysis of social problem solving and social self-efficacy in prospective teachers., person-based social problem solving among 10-, 14- and 16-year-olds.

- Highly Influenced

The Influence of Social Problem-Solving Ability on the Relationship Between Daily Stress and Adjustment

5 references, problem-solving therapy : a social competence approach to clinical intervention, problem-solving therapy for depression. theory, research and clinical guidelines, problem solving and behavior modification., social problem solving and negative affective conditions., social problem solving in adults, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

The Pathway 2 Success

Solutions for Social Emotional Learning & Executive Functioning

Teaching Social Problem-Solving with a Free Activity

February 3, 2018 by pathway2success 5 Comments

- Facebook 77

Kids and young adults need to be able to problem-solve on their own. Every day, kids are faced with a huge number of social situations and challenges. Whether they are just having a conversation with a peer, working with a group on a project, or dealing with an ethical dilemma, kids must use their social skills and knowledge to help them navigate tough situations. Ideally, we want kids to make positive choices entirely on their own. Of course, we know that kids don’t start off that way. They need to learn how to collaborate, communicate, cooperate, negotiate, and self-advocate.

Social problem solving skills are critical skills to learn for kids with autism, ADHD, and other social challenges. Of course, all kids and young adults benefit from these skills. They fit perfectly into a morning meeting discussion or advisory periods for older kids. Not only are these skills that kids will use in your classroom, but throughout their entire lives. They are well worth the time to teach!

Here are 5 steps to help kids learn social problem solving skills:

1. Teach kids to communicate their feelings. Being able to openly and respectfully share emotions is a foundational element to social problem solving. Teaching I statements can be a simple and effective way to kids to share their feelings. With an I statement, kids will state, “I feel ______ when _____.” The whole idea is that this type of statement allows someone to share how their feeling without targeting or blaming anyone else. Helping kids to communicate their emotions can solve many social problems from the start and encourages positive self-expression.

2. Discuss and model empathy. In order for kids to really grasp problem-solving, they need to learn how to think about the feelings of others. Literature is a great way teach and practice empathy! Talk about the feelings of characters within texts you are reading, really highlighting how they might feel in situations and why. Ask questions like, “How might they feel? Why do you think they felt that way? Would you feel the same in that situation? Why or why not?” to help teach emerging empathy skills. You can also make up your own situations and have kids share responses, too.

3. Model problem-solving skills. When a problem arises, discuss it and share some solutions how you might go forward to fix it. For example, you might say, “I was really expecting to give the class this math assignment today but I just found out we have an assembly. This wasn’t in my plans. I could try to give part of it now or I could hold off and give the assignment tomorrow instead. It’s not perfect, but I think I’ll wait that way we can go at the pace we need to.” This type of think-aloud models the type of thinking that kids should be using when a problem comes up.