| (2014) PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science. During the 2000s the terms ‘imperialism’ and ‘empire’ made a reappearance. This reappearance followed ‘unilateral’ military interventions by the United States and its allies. Because these military interventions were all justified using international legal argument that the international legal discipline also became increasingly concerned with these terms.

Given this, it is unsurprising that there also arose two critical schools of thinking about international law, who foregrounded its relationship to imperialism. These were those working in the Marxist tradition and the Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) movement. Both of these intellectual movements are contemporary examples of older traditions.

Despite this popularity, there has been little sustained attention to the specific concepts of imperialism that underlie these debates. This thesis attempts to move beyond this, through mapping the way in which Marxist and TWAIL scholars have understood imperialism and its relationship to international law.

The thesis begins by reconstructing the conceptual history of the terms ‘colonialism’, ‘empire’ and ‘imperialism’, drawing out how they are enmeshed in broader theoretical and historical moments. In particular it pays close attention to the historical and political consequences of adopting particular understandings of these concepts.

It then examines how these understandings have played out concretely. It reconstructs earlier Third Worldist thinking about imperialism and international law, before showing how contemporary TWAIL scholars have understood this relationship. It then looks at how the Marxist tradition has understood imperialism, before turning specifically to Marxist international legal theory.

Finally, it turns to the interrelationship between Marxist and Third Worldist theory, arguing that each tradition can contribute to remedying the limitations in the other. In so doing it also attempts to flag up the complex historical inter-relation between these two traditions of thinking about imperialism and international law. | Item Type: | Thesis (PhD) | | Additional Information: | © 2014 Robert Knox | | Library of Congress subject classification: | | | Sets: | | | Supervisor: | Hoffman, Florian | | URI: | |  Actions (login required) | | Record administration - authorised staff only |  Downloads per month over past year View more statistics Sign in through your institution- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

3. Ideology and Law- Published: October 1984

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

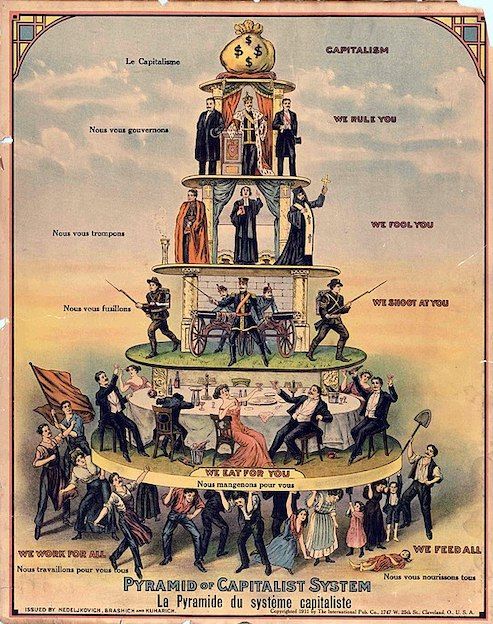

This chapter looks at the problem of consciousness in order to analyse the Marxist explanation of how the ruling class know how to rule, and in particular how they use law as an instrument of class oppression. The first section elaborates upon the Marxist theory of ideology. It does this in order to demonstrate the plausibility of the contention that a common perception of self-interest emerges within the dominant class. It then considers the merits of such a claim when confronted with the variety of laws and legal systems. Personal account- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional accessSign in with a library card. - Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways: IP based accessTypically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account. Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic. - Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator. Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian. Society MembersSociety member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways: Sign in through society siteMany societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal: - Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society. Sign in using a personal accountSome societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below. A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions. Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. Viewing your signed in accountsClick the account icon in the top right to: - View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access contentOxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian. For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more. Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions. | Month: | Total Views: | | October 2022 | 43 | | November 2022 | 25 | | December 2022 | 21 | | January 2023 | 7 | | February 2023 | 36 | | March 2023 | 56 | | April 2023 | 52 | | May 2023 | 121 | | June 2023 | 31 | | July 2023 | 9 | | August 2023 | 19 | | September 2023 | 57 | | October 2023 | 51 | | November 2023 | 41 | | December 2023 | 61 | | January 2024 | 27 | | February 2024 | 39 | | March 2024 | 60 | | April 2024 | 105 | | May 2024 | 80 | | June 2024 | 8 | | July 2024 | 5 | - About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide - Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers OnlySign In or Create an Account This PDF is available to Subscribers Only For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription. Bourdieu, Marxism and Law: Between Radical Criticism and Political Responsibility- First Online: 30 September 2022

Cite this chapter Part of the book series: Marx, Engels, and Marxisms ((MAENMA)) 645 Accesses The chapter aims to investigate the way Bourdieu’s sociology of juridical field has defined itself through its relationship with Marx and the Marxism of Althusser and Thompson. Firstly, it shows Bourdieu’s relationship with Marx through a case of misinterpretation concerning practical obedience to law. Then it tries to highlight how Bourdieu develops certain features of his sociology in opposition to and in dialogue with Althusser and Thompson, proposing an epistemological model of radical critique aimed at politically problematizing law through the analysis of the relationship between the juridical field, the field of power and the habitus. This model is contradicted neither by the realpolitk of reason nor by the political positions taken by Bourdieu in the 1990s in favour of public service and Welfare State. Indeed, it shows a Marxian ancestry in the constant concern to link the analysis and critique of normativity to power relations and social struggles, as emerges from the confrontation between Bourdieu and the Durkheimian-derived juridical perspectives. This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access. Access this chapterSubscribe and save. - Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout Purchases are for personal use only Institutional subscriptions Similar content being viewed by others Philosophical and Theological Aspects in the Thought of Johannes Althusius Rousseau, Jean-Jacques: Law Helvétius, Claude-AdrienBourdieu was familiar with Marxist studies in the juridical field thanks to S. Spitzer ( 1983 ). My analysis will not consider the specificities of Bourdieusian sociology outside of its relationship with Marx or Marxism, nor the Marxist authors who concerned themselves with law but whom Bourdieu does not discuss (e.g. Gramsci, Pashukanis, Poulantzas). Bourdieu ( 1987 : 849): “the movement from statistical regularity to legal rule represents a true social modification.” Marx and Engels ( 1976 : 31–32): “As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with what they produce and with how they produce.” As has been observed, on this point Bourdieu stands very close to the work of historians such as Robert W. Gordon. See Coombe ( 1989 ). Jean-Yves Caro was one of the first economists to deal with neoliberalism in France from a Bourdieusian perspective. See Caro ( 1981 and 1983 ). Yves Dezalay has analysed in numerous works the neoliberal transformations of law. See Dezalay ( 1992 ). Among his work with Brian Garth, see at least Dezalay and Garth ( 1998 , 2021 ). On the other dimensions of political struggle (redefinition of the macroeconomic calculus, internationalism, etc.) that Laval recognizes in Bourdieu, see Laval ( 2018 : 243–245). Bourdieu ( 1987 : 844): “Alain Bancaud and Yves Dezalay have demonstrated that even the most heretical of dissident legal scholars in France, those who associate themselves with sociological or Marxist methodologies to advance the rights of specialists working in the most disadvantaged areas of the law (such as social welfare law, droit social),” continue to claim a monopoly of the science of jurisprudence. See Bancaud and Dezalay ( 1984 ). The quotation in this note belongs to Eugen Ehrlich, but the translator did not indicate this. For an appreciation of the pars destruens and a critique of the pars construens of Duguit’s work, see Chevallier ( 1979 ). On this point, I have tried to interpret Bourdieu’s and Foucault’s methodological innovations in the juridical field as an extension of the external history of law, in the direction of a critique of the articulation of legal practices with phenomena of heterogeneous social normativity (Brindisi 2019 ). On the relationship between Bourdieu and Foucault see Brindisi and Irrera ( 2017 ), Laval ( 2018 ). Althusser, Louis. 2014 [1995]. On the Reproduction of Capitalism. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses . Ed. G.M. Goshgarian. London and New York: Verso. Google Scholar Bancaud, Alain, and Yves Dezalay. 1984. La sociologie juridique comme enjeu social et professionnel. Revue interdisciplinaire d’études juridiques 12 (1): 1–29. Article Google Scholar Bidet, Jacques. 2014. Introduction: An Invitation to Reread Althusser. In On the Reproduction of Capitalism. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses , ed. Louis Althusser, XIX–XXVIII. London and New York: Verso. Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987 [1986]. The Force of Law: Toward a Sociology of the Juridical Field . Trans. R. Terdinam. The Hastings Law Journal 38: 814–815. ———. 1989. Reproduction interdite. La dimension symbolique de la domination économique. Etudes rurales 113–114: 15–36. ———. 1990a [1987]. In Other Words: Essays Toward a Reflexive Sociology . Trans. M. Adamson. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ———. 1990b. Droit et passe-droit. Le champ des pouvoirs territoriaux et la mise en œuvre des réglements. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 81–82: 86–96. ———. 1991. Les juristes, gardiens de l’hypocrisie collective. In Normes juridiques et régulation sociale , ed. François Chazel and Jacques Comaille, 95–99. Paris: LGDJ. ———. 1992 [1980]. The Logic of Practice . Trans. R. Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ———. 1994. Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l’action . Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ———. 1996 [1989]. The State Nobility. Elite Schools in the Field of Power . Trans. L.C. Clough. Cambridge: Polity Press. ———. 1998a [1998]. Acts of Resistance: Against the New Myths of Our Time . Trans. R. Nice. New York: The New Press. ———. 1998b [1994]. Practical Reason. On the Theory of Action . Trans. R. Johnson. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ———. 2000 [1997]. Pascalian Meditations . Trans. R. Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ———. 2008 [2002]. Political Interventions. Social Science and Political Action . Trans. D. Fernbach. London and New York: Verso. ———. 2014 [2012]. On the State. Lectures at the College de France, 1989–1992 . Trans. D. Fernbach. Cambridge: Polity. ———. 2016. Sociologie générale. Cours au Collège de France 1983–1986, Volume 2 . Paris: Raisons d’agir/Seuil. ———. 2018 [2015]. Classification Struggles. General Sociology. Volume 1. Lectures at the College de France (1981–1982) . Trans. P. Collier. Cambridge: Polity. ———. 2020 [2015]. Habitus and Field. General Sociology, Volume 2. Lectures at the College de France (1982–1983) . Trans. P. Collier. Cambridge: Polity. ———. 2022. L’Intérêt au désintéressement. Cours au Collège de France 1983–1986 . Paris: Raisons d’agir/Seuil. Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jacques Maître. 1994. Avant-propos dialogué avec Pierre Bourdieu . In L’autobiographie d’un paranoïaqu , ed. Jacques Maître, V–XXII. Paris: Anthropos. Brindisi, Gianvito. 2018. Violenza simbolica e soggettivazione. Sul rapporto tra psicoanalisi e sociologia in Pierre Bourdieu. In Dimensione simbolica. Attualità e prospettive di ricerca , ed. Vincenzo Rapone, 55–79. Milano: Mimesis. ———. 2019. La storia esterna del giudiziario tra Bourdieu e Foucault. Teoria e critica della regolazione sociale 2: 183–205. Brindisi, Gianvito, and Orazio Irrera, eds. 2017. Bourdieu/Foucault: un rendez-vous mancato? Cartografie sociali. Rivista di sociologia e scienze umane 4: 7–244. Caro, Jean-Yves. 1981. La théorie économique du crime. Sociologie du travail 23 (1): 122–128. ———. 1983. Les économistes distingués. Logique sociale d’un champ scientifique . Paris: Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques. Chevallier, Jacques. 1979. Les fondements idéologiques du droit administratif français. In Variations autour de l’idéologie de l’intérêt général , ed. Jacques Chevallier, vol. 2, 3–57. Paris: PUF. Commaille, Jacques. 2008. Droit et sociologie. Des rapports au risque de l’histoire. Académie de sciences morales et politiques . Available online https://academiesciencesmoralesetpolitiques.fr/2008/06/09/sociologie-et-droit/ Coombe, Rosemary J. 1989. Room for Manoeuver: Toward a Theory of Practice in Critical Legal Studies. Law & Social Inquiry 14 (1): 69–121. Croce, Mariano. 2015. The Habitus and the Critique of the Present: A Wittgensteinian Reading of Bourdieu’s Social Theory. Sociological Theory 33 (4): 327–346. De Fiores, Claudio. 2019. Tra diritto e rivoluzione. La questione costituzionale in Karl Marx. Democrazia e diritto 2: 32–90. Dezalay, Yves. 1992. Marchands de droit. La restructuration de l’ordre juridique international par les multinationals du droit . Paris: Fayard. Dezalay, Yves, and Garth Bryant. 1998. Le «Washington consensus». Contribution à une sociologie de l’hégémonie du néolibéralisme. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 121–122: 3–22. Dezalay, Yves, and Bryant Garth. 2021. Law as Reproduction and Revolution: An Interconnected History . Stanford: University of California Press. Book Google Scholar Duguit, Léon. 1913. Les transformations du droit public . Paris: Armand Colin. Fabiani, Jean-Louis. 2016. Pierre Bourdieu. Un structuralisme héroique . Paris: Seuil. Hauriou, Maurice. 1884. L’histoire externe du droit . Paris: Cotillon. Laval, Christian. 2018. Foucault, Bourdieu et la question néolibérale . Paris: Éditions la Découverte. Legendre, Pierre. 1974. L’Amour du censeur. Essai sur l’ordre dogmatique . Paris: Seuil. Maine, Henry Sumner. 1875. Lectures on the Early History of Institutions . New York: Henry Holt and Company. Marx, Karl. 1974 [1880–1882]. The Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx . Ed. L. Krader. Assen: Van Gorkum. ———. 1975 [1842]. Proceedings of the Sixth Rhine Province Assembly. Third Article Debates on the Law on Thefts of Wood . Trans. C. Dutt. In MECW , vol. 1: 224–263. ———. 1976 [1847]. The Poverty of Philosophy . Trans. F. Knight. In MECW , vol. 6: 105–212. ———. 1986–1987 [1857–1858]. Economic Manuscripts of 1857– 58. Trans. E. Wangermann. In MECW , vol. 28. Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1976 [1932]. The German Ideology . Trans. C. Dutt. In MECW , vol. 5: 19–539. ———. 2017 [1848]. The Communist Manifesto . Trans. S. Moore. London: Pluto Press. Pallotta, Julien. 2015. Bourdieu face au marxisme althussérien: la question de l’état. Actuel Marx 58: 130–143. Sfez, Lucien. 1976. Duguit et la théorie de l’état (représentation et communication). Archives de Philosophie du droit 21: 111–130. Spitzer, Steven. 1983. Marxist Perspectives in the Sociology of Law. Annual Review of Sociology 9: 103–124. Supiot, Alain. 2017 [2005]. Homo juridicus. On the Anthropological Function of the Law . Trans. S. Brown. London and New York: Verso. Thompson, Edward Palmer. 1975. Whigs and Hunters. The Origins of the Black Act . London: Allen Lane. ———. 1976. Modes de domination et révolutions en Angleterre. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 2 (2–3): 133–151. ———. 1978. The Poverty of Theory & Others Essays . London: Merlin. Wacquant, Loïc. 1993. From Ruling Class to Field of Power: An Interview with Pierre Bourdieu on La Noblesse d’État . Theory, Culture & Society 10: 19–44. Xifaras, Mikhail. 2002. Marx, justice et jurisprudence une lecture des ‘vols de bois’. Revue Française d’Histoire des Idées Politiques 15: 63–112. Download references Author informationAuthors and affiliations. University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Caserta, Italy Gianvito Brindisi You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar Corresponding authorCorrespondence to Gianvito Brindisi . Editor informationEditors and affiliations. Department of Political and Social Sciences, University of Florence, Firenze, Italy Gabriella Paolucci Additional informationI’m grateful to Bridget Fowler for reading this paper and for her valuable suggestions. Rights and permissionsReprints and permissions Copyright information© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG About this chapterBrindisi, G. (2022). Bourdieu, Marxism and Law: Between Radical Criticism and Political Responsibility. In: Paolucci, G. (eds) Bourdieu and Marx. Marx, Engels, and Marxisms. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06289-6_13 Download citationDOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06289-6_13 Published : 30 September 2022 Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham Print ISBN : 978-3-031-06288-9 Online ISBN : 978-3-031-06289-6 eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)  Share this chapterAnyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative Policies and ethics - Find a journal

- Track your research

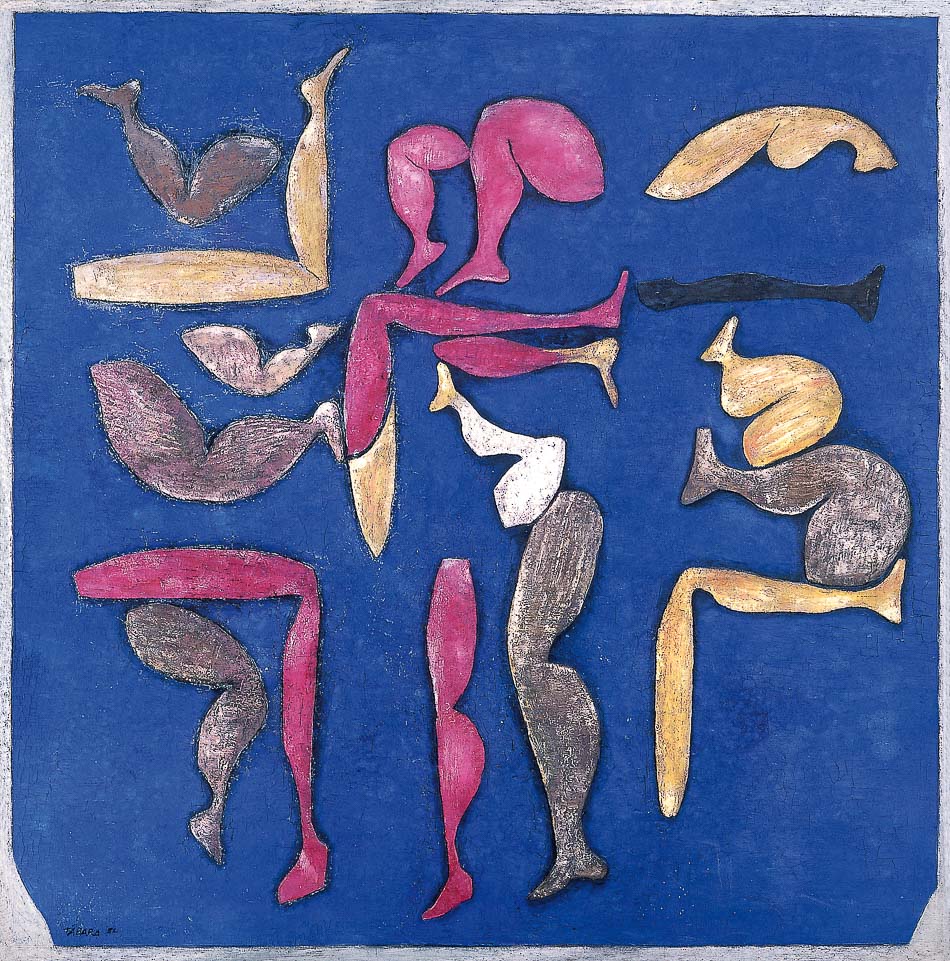

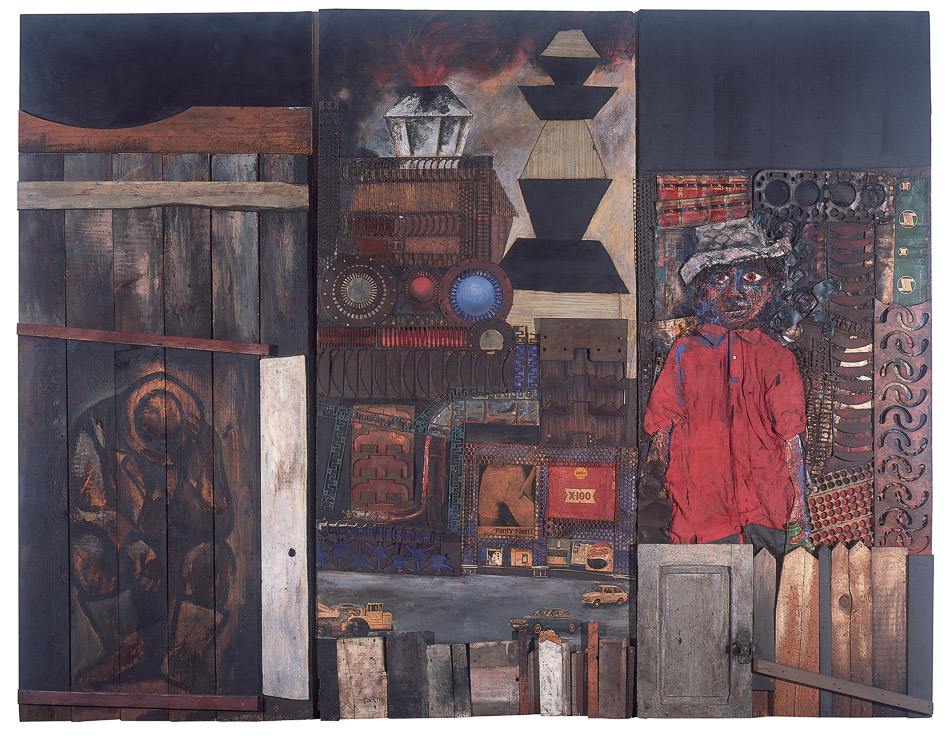

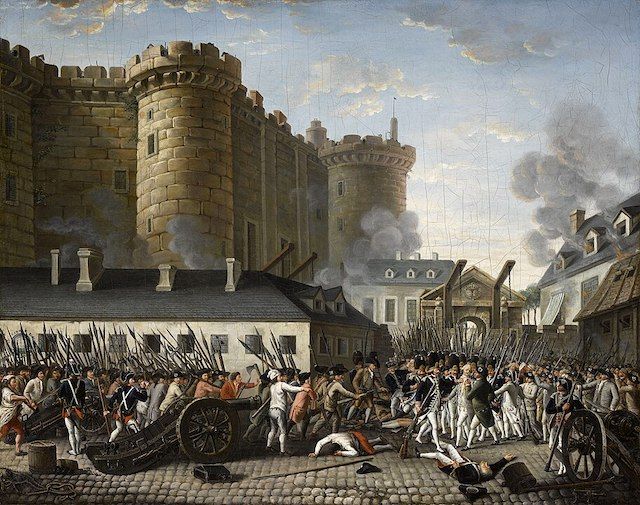

Ten Theses on Marxism and DecolonisationDossier no. 56  Violeta Parra (Chile), Untitled (unfinished), 1966. Embroidery on sackcloth, 136 x 200 cm. The works of art in this dossier belong to Casa de las Américas’ Haydee Santamaría Art of Our America ( Nuestra América ) collection. Since its founding, Casa de las Américas has established close ties with a significant number of internationally renowned contemporary artists who have set visual arts trends in the region. Casa’s galleries have hosted temporary exhibitions including different artistic genres, expressions, and techniques by several generations of mainly Latin American and Caribbean artists. Many of these works, initially exhibited in Casa’s galleries, awarded prizes in its contests, and donated by the artists, have become part of the Haydee Santamaría Art of Our America collection, representing an exceptional artistic heritage.  Roberto Matta (Chile), Cuba es la capital (‘Cuba Is the Capital’), 1963. Soil and plaster on Masonite (mural), 188 x 340 cm. Located at the entrance to Casa de las Américas. Cultural Policy and Decolonisation in the Cuban Socialist ProjectAbel prieto, director of casa de las américas. The Cuban Revolution came about in a country subordinated to the US from all points of view. Although we had the façade of a republic, we were a perfect colony, exemplary in economic, commercial, diplomatic, and political terms, and almost in cultural terms. Our bourgeoisie was constantly looking towards the North: from there, they imported dreams, hopes, fetishes, models of life. They sent their children to study in the North, hoping that they would assimilate the admirable competitive spirit of the Yankee ‘winners’, their style, their unique and superior way of settling in this world and subjugating the ‘losers’. This ‘vice-bourgeoisie’, as Roberto Fernández Retamar baptised them, were not limited to avidly consuming whatever product of the US cultural industry fell into their hands. Not only that – at the same time, they collaborated in disseminating the ‘American way of life’ in the Ibero-American sphere and kept part of the profits for themselves. Cuba was an effective cultural laboratory at the service of the Empire, conceived to multiply the exaltation of the Chosen Nation and its world domination. Cuban actresses and actors dubbed the most popular American television series into Spanish, which would later flood the continent. In fact, we were among the first countries in the region to have television in 1950. It seemed like a leap forward, towards so-called ‘progress’, but it turned out to be poisoned. Very commercial Cuban television programming functioned as a replica of the ‘made in the USA’ pseudo-culture , with soap operas, Major League and National League baseball games, competition and participation programmes copied from American reality shows, and constant advertising. In 1940, the magazine Selections of the Reader’s Digest , published by a company of the same name, began to appear in Spanish in Havana with all of its poison. This symbol of the idealisation of the Yankee model and the demonisation of the USSR and of any idea close to emancipation was translated and printed on the island and distributed from here to all of Latin America and Spain. The very image of Cuba that was spread internationally was reduced to a tropical ‘paradise’ manufactured by the Yankee mafia and its Cuban accomplices. Drugs, gambling, and prostitution were all put at the service of VIP tourism from the North. Remember that the Las Vegas project had been designed for our country and failed because of the revolution. Fanon spoke of the sad role of the ‘national bourgeoisie’ – already formally independent from colonialism – before the elites of the old metropolis, ‘who happen to be tourists enamoured of exoticism, hunting, and casinos’. He added: We only have to look at what has happened in Latin America if we want proof of the way the ex-colonised bourgeoisie can be transformed into ‘party’ organiser. The casinos in Havana and Mexico City, the beaches of Rio, Copacabana, and Acapulco, the young Brazilian and Mexican girls, the thirteen-year-old mestizas, are the scars of this depravation of the national bourgeoisie. 1 Our bourgeoisie, submissive ‘party organisers’ of the Yankees, did everything possible for Cuba to be culturally absorbed by their masters during the neocolonial republic. However, there were three factors that slowed down this process: the work of intellectual minorities that defended, against all odds, the memory and values of the nation; the sowing of Martí’s principles and patriotism among teachers in Cuban public schools; and the resistance of our powerful, mestizo, haughty, and ungovernable popular culture, nurtured by the rich spiritual heritage of African origin. In his speech ‘History Will Absolve Me’, Fidel listed the six main problems facing Cuba. Among them, he highlighted ‘the problem of education’ and referred to ‘comprehensive education reform’ as one of the most urgent missions that the future liberated republic would have to undertake. 2 Hence, the educational and cultural revolution began practically from the triumph of 1 January 1959. On the 29 th of that same month, summoned by Fidel, a first detachment of three hundred teachers alongside one hundred doctors and other professionals left for the Sierra Maestra to bring education and health to the most remote areas. Around those same days, Camilo and Che launched a campaign to eradicate illiteracy among the Rebel Army troops since more than 80% of the combatants were illiterate. On 14 September, the former Columbia Military Camp was handed over to the Ministry of Education so that it could build a large school complex there. The promise of turning barracks into schools was beginning to be fulfilled, and sixty-nine military fortresses became educational centres. On 18 September, Law No. 561 was enacted, creating ten thousand classrooms and accrediting four thousand new teachers. The same year, cultural institutions of great importance were created: the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC), the National Publishing House, the Casa de las Américas, and the National Theatre of Cuba, which has a department of folklore and an unprejudiced and anti-racist vision unprecedented in the country. All of these new revolutionary institutions were oriented towards a decolonised understanding of Cuban and universal culture. But 1961 was the key year in which a profound educational and cultural revolution began in Cuba. This was the year when Eisenhower ruptured diplomatic relations with our country. This was the year when our foreign minister, Raúl Roa, condemned ‘the policy of harassment, retaliation, aggression, subversion, isolation, and imminent attack by the US against the Cuban government and people’ at the UN. 3 This was the year of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the relentless fight against the armed gangs financed by the CIA. This was the year when the US government, with Kennedy already at the helm, intensified its offensive to suffocate Cuba economically and isolate it from Nuestra Am é rica – Our America – and from the entire Western world. 4 1961 was also the year when Fidel proclaimed the socialist character of the revolution on 16 April, the eve of the Bay of Pigs invasion, as Roa exposed the plan that was set to play out the following day. This is something that – considering the influence of the Cold War climate and the McCarthyite, anti-Soviet, and anti-communist crusade on the island – showed that the young revolutionary process had been shaping, at incredible speed, cultural hegemony around anti-imperialism, sovereignty, social justice, and the struggle to build a radically different country. But it was also the year of the epic of the literacy campaign; of the creation of the National School of Art Instructors; of Fidel’s meetings with intellectuals and his founding speech on our cultural policy, ‘Words to the Intellectuals’; of the birth of the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC) and the National Institute of Ethnology and Folklore. 5 In 1999 in Venezuela – almost four decades later – Fidel summed up his thinking regarding the cultural and educational component in any true revolutionary process: ‘A revolution can only be the child of culture and ideas’. 6 Even if it makes radical changes, even if it hands over land to the peasants and eliminates large estates, even if it builds houses for those who survive in unhealthy neighbourhoods, even if it puts public health at the service of all, even if it nationalises the country’s resources and defends its sovereignty, a revolution will never be complete or lasting if it does not give a decisive role to education and culture. It is necessary to change human beings’ conditions of material life, and it is necessary to simultaneously change the human being, their conscience, paradigms, and values. For Fidel, culture was never something ornamental or a propaganda tool – a mistake commonly made throughout history by leaders of the left. Rather, he saw culture as a transformative energy of exceptional scope, which is intimately linked to conduct, to ethics, and is capable of decisively contributing to the ‘human improvement’ in which Martí had so much faith. But Fidel saw culture, above all, as the only imaginable way to achieve the full emancipation of the people: it is what offers them the possibility of defending their freedom, their memory, their origins, and of undoing the vast web of manipulations that limit the steps they take every day. The educated and free citizen who is at the centre of Martí’s and Fidel’s utopia must be prepared to fully understand the national and international environment and to decipher and circumvent the traps of the machinery of cultural domination. In 1998, at the 6 th Congress of the UNEAC, Fidel focused on the topic ‘related to globalisation and culture’. So-called ‘neoliberal globalisation’, he said, is ‘the greatest threat to culture – not only ours, but the world’s’. He explained how we must defend our traditions, our heritage, our creation, against ‘imperialism’s most powerful instrument of domination’. And, he concluded, ‘everything is at stake here: national identity, homeland, social justice, revolution, everything is at stake. These are the battles we have to fight now’. 7 This is, of course, about ‘battles’ against cultural colonisation, against what Frei Betto calls ‘globo-colonisation’, against a wave that can liquidate our identity and the revolution itself.  Enrique Tábara (Ecuador), Coloquio de frívolos (‘Colloquium of the Frivolous’), 1982. Acrylic on canvas,140.5 x 140.5 cm. Fidel was already convinced that, in education, in culture, in ideology, there are advances and setbacks. No conquest can be considered definitive. That is why he returns to the subject of culture in his shocking speech on 17 November 2005 at the University of Havana. 8 The media machinery, together with incessant commercial propaganda, Fidel warns us, come to generate ‘conditioned responses’. ‘The lie’, he says, ‘affects one’s knowledge’, but ‘the conditioned response affects the ability to think’. 9 In this way, Fidel continued, if the Empire says ‘Cuba is bad’, then ‘all the exploited people around the world, all the illiterate people, and all those who don’t receive medical care or education or have any guarantee of a job or of anything’ repeat that ‘the Cuban Revolution is bad’. 10 Hence, the diabolical sum of ignorance and manipulation engenders a pathetic creature: the poor right-winger, that unhappy person who gives his opinion and votes and supports his exploiters. ‘Without culture’, Fidel repeated, ‘no freedom is possible’. 11 We revolutionaries, according to him, are obliged to study, to inform ourselves, to nurture our critical thinking day by day. This cultural education, together with essential ethical values, will allow us to liberate ourselves definitively in a world where the enslavement of minds and consciences predominates. His call to ‘emancipat[e] ourselves by ourselves and with our own efforts’ is equivalent to saying that we must decolonise ourselves with our own efforts. 12 And culture is, of course, the main instrument of that decolonising process of self-learning and self-emancipation. In Cuba, we are currently more contaminated by the symbols and fetishes of ‘globo-colonisation’ than we have been at other times in our revolutionary history. We must combat the tendency to underestimate these processes, and we must work in two fundamental directions: intentionally promoting genuine cultural options and fostering a critical view of the products of the hegemonic entertainment industry. It is essential to strengthen the effective coordination of institutions and organisations, communicators, teachers, instructors, intellectuals, artists, and other actors who contribute directly or indirectly to the cultural education of our people. All revolutionary forces of culture must work together more coherently. We must turn the meaning of anti-colonial into an instinct. IntroductionIn 1959, the Cuban revolutionary leader Haydee Santamaría (1923–1980) arrived at a cultural centre in the heart of Havana. This building, the revolutionaries decided, would be committed to promoting Latin American art and culture, eventually becoming a beacon for the progressive transformation of the hemisphere’s cultural world. Renamed Casa de las Américas (‘Home of the Americas’), it would become the heartbeat of cultural developments from Chile to Mexico. Art saturates the walls of the house, and in an adjacent building sits the massive archive of correspondence and drafts from the most significant writers of the past century. The art from Casa adorns this dossier. The current director of Casa, Abel Prieto – whose words open this dossier – is a novelist, a cultural critic, and a former minister of culture. His mandate is to stimulate discussion and debate in the country. Over the course of the past decade, Cuba’s intellectuals have been gripped by the debate over decolonisation and culture. Since 1959, the Cuban revolutionary process has – at great cost – established the island’s political sovereignty and has struggled against centuries of poverty to cement its economic sovereignty. From 1959 onwards, under the leadership of the revolutionary forces, Cuba has sought to generate a cultural process that allows the island’s eleven million people to break with the cultural suffocation which is the legacy of both Spanish and US imperialism. Is Cuba, six decades since 1959, able to say that it is sovereign in cultural terms? The balance sheet suggests that the answer is complex since the onslaught of US cultural and intellectual production continues to hit the island like its annual hurricanes. To that end, Casa de las Américas has been holding a series of encounters on the issue of decolonisation. In July 2022, Vijay Prashad, the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, delivered a lecture there that built upon the work being produced by the institute. Dossier no. 56, Ten Theses on Marxism and Decolonisation , draws from and expands upon the themes of that talk.  Antonio Seguí (Argentina), Untitled , 1965. Oil on canvas, 200 x 249 cm. Thesis One: The End of History . The collapse of the USSR and the communist state system in Eastern Europe in 1991 came alongside a terrible debt crisis in the Global South that began with Mexico’s default in 1982. These two events – the demise of the USSR and the weakness of the Third World Project – were met with the onslaught of US imperialism and a US-driven globalisation project in the 1990s. For the left, this was a decade of weakness as our left-wing traditions and organisations experienced self-doubt and could not easily advance our clarities around the world. History had ended, said the ideologues of US imperialism, with the only possibility forward being the advance of the US project. The penalty inflicted upon the left by the surrender of Soviet leadership was heavy and led not only to the shutting down of many left parties, but also to the weakened confidence of millions of people with the clarities of Marxist thought. Thesis Two: The Battle of Ideas . During the 1990s, Cuban President Fidel Castro called upon his fellow Cubans to engage in a ‘battle of ideas’, a phrase borrowed from The German Ideology (1846) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. 1 What Castro meant by this phrase is that people of the left must not cower before the rising tide of neoliberal ideology but must confidently engage with the fact that neoliberalism is incapable of solving the basic dilemmas of humanity. For instance, neoliberalism has no answer to the obstinate fact of hunger: 7.9 billion people live on a planet with food enough for 15 billion, and yet roughly 3 billion people struggle to eat. This fact can only be addressed by socialism and not by the charity industry. 2 The Battle of Ideas refers to the struggle to prevent the conundrums of our time – and the solutions put forth to address them – from being defined by the bourgeoisie. Instead, the political forces for socialism must seek to offer an assessment and solutions far more realistic and credible. For instance, Castro spoke at the United Nations in 1979 with great feeling about the ideas of ‘human rights’ and ‘humanity’: There is often talk of human rights, but it is also necessary to speak of the rights of humanity. Why should some people walk around barefoot so that others can travel in luxurious automobiles? Why should some live for 35 years so that others can live for 70? Why should some be miserably poor so that others can be overly rich? I speak in the name of the children in the world who do not have a piece of bread. I speak in the name of the sick who do not have medicine. I speak on behalf of those whose right to life and human dignity has been denied. 3 When Castro returned to the Battle of Ideas in the 1990s, the left was confronted by two related tendencies that continue to create ideological problems in our time: - Post-Marxism. An idea flourished that Marxism was too focused on ‘grand narratives’ (such as the importance of transcending capitalism for socialism) and that fragmentary stories would be more precise for understanding the world. The struggles of the working class and peasantry to gain power in society and over state institutions were seen as just another false ‘grand narrative’, whereas the fragmented politics of the non-governmental organisations were seen as more feasible. The retreat from power into service delivery and into a politics of reform was made in the name of going beyond Marx. But this argument – to go beyond Marx – was really, as the late Aijaz Ahmad pointed out, an argument to return to the period before Marx, to neglect the facts of historical materialism and the zig-zag possibility of building socialism as the historical negation of capitalist brutality and decadence. Post-Marxism was a return to idealism and to perfectionism.

- Post-colonialism . Sections of the left began to argue that the impact of colonialism was so great that no amount of transformation would be possible, and that the only answer to what could come after colonialism was a return to the past. They treated the past, as the Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui argued in 1928 about the idea of indigenism, as a destination and not as a resource. Several strands of post-colonial theory developed, some of them offering genuine insights often drawn from the best texts of patriotic intellectuals of the new post-colonial nations and of the national liberation revolutionary tradition (anchored by writers such as Frantz Fanon). By the 1990s, the post-colonial tradition, which had previously been committed to revolutionary change in the Third World, was now swept up in North Atlantic university currents that favoured revolutionary impossibility. Afro-pessimism, one part of this new tradition, suggested – in its most extreme version – a desolate landscape of ‘social death’ for people of African descent, with no possibility of change. Decolonial thought or decolonialidad trapped itself by European thought, accepting the claim that many human concepts – such as democracy – are defined by the colonial ‘matrix of power’ or ‘matrix of modernity’. The texts of decolonial thought returned again and again to European thought, unable to produce a tradition that was rooted in the anti-colonial struggles of our time. The necessity of change was suspended in these variants of post-colonialism.

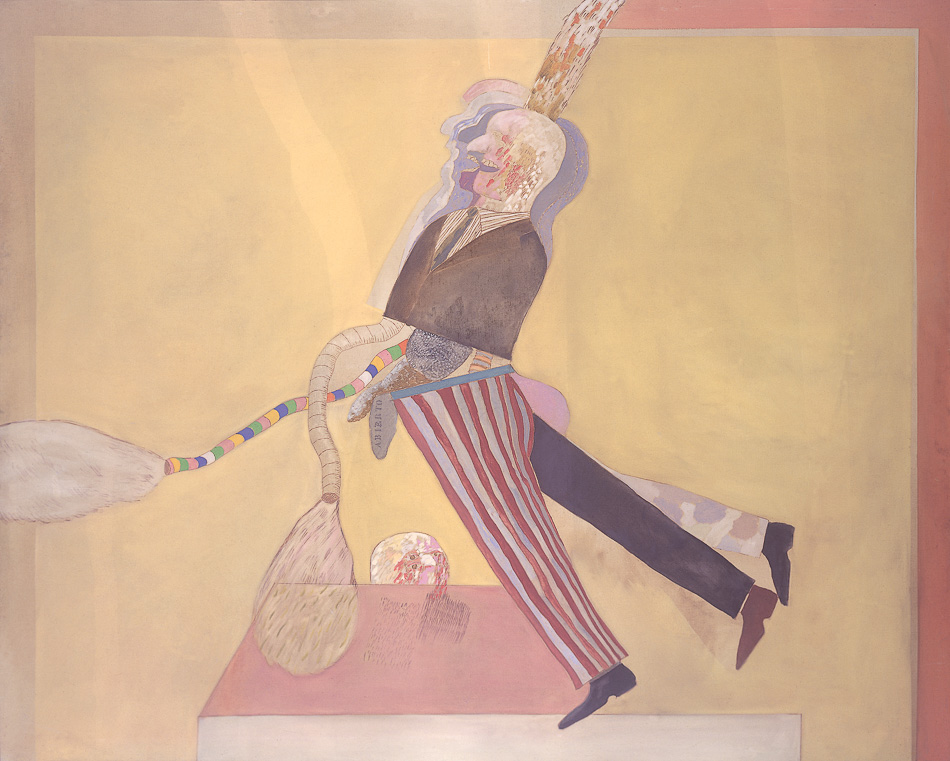

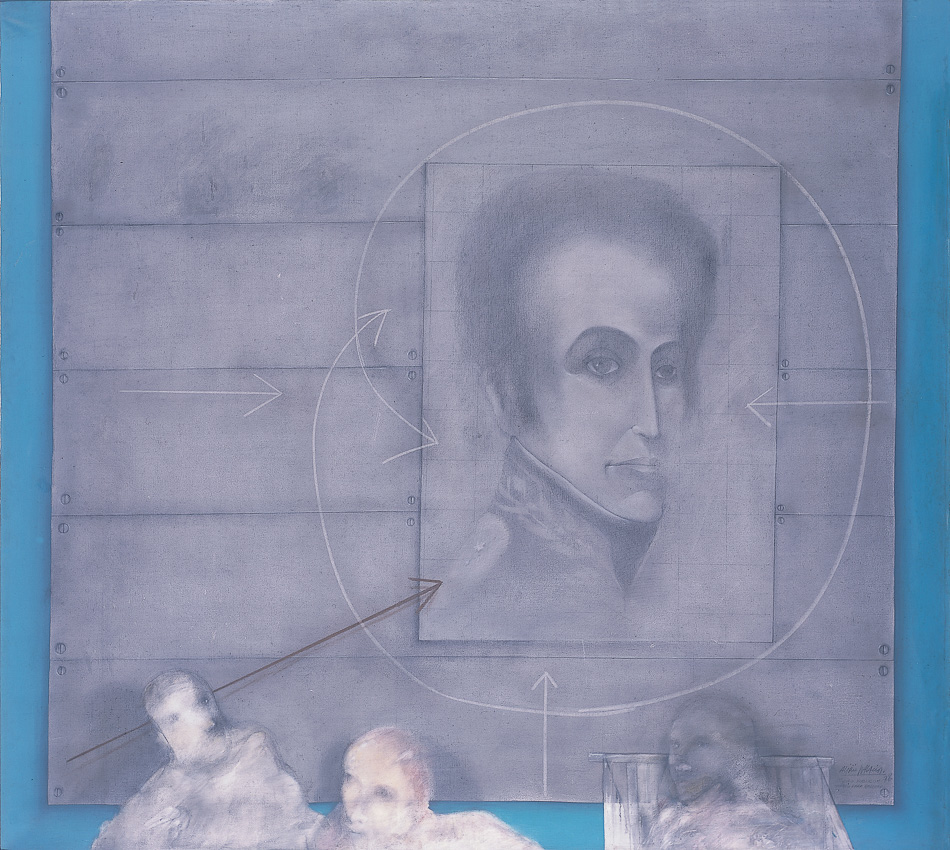

The only real decolonisation is anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism. You cannot decolonise your mind unless you also decolonise the conditions of social production that reinforce the colonial mentality. Post-Marxism ignores the fact of social production as well as the need to build social wealth that must be socialised. Afro-pessimism suggests that such a task cannot be accomplished because of permanent racism. Decolonial thought goes beyond Afro-pessimism but cannot go beyond post-Marxism, failing to see the necessity of decolonising the conditions of social production.  Antonio Martorell (Puerto Rico), Silla (‘Chair’), n.d., edition unknown. Woodcut. 100 x 62 cm. Thesis Three: A Failure of Imagination. In the period from 1991 to the early 2000s, the broad tradition of national liberation Marxism felt flattened, unable to answer the doubts sown by post-Marxism and post-colonial theory. This tradition of Marxism no longer had the kind of institutional support provided in an earlier period, when revolutionary movements and Third World governments assisted each other and when even the United Nations’ institutions worked to advance some of these ideas. Platforms that developed to germinate left forms of internationalism – such as the World Social Forum – seemed to be unwilling to be clear about the intentions of peoples’ movements. The slogan of the World Social Forum, for instance, was ‘another world is possible’, which is a weak statement, since that other world could just as well be defined by fascism. There was little appetite to advance a slogan of precision, such as ‘socialism is necessary’. One of the great maladies of post-Marxist thought – which derived much of its ammunition from forms of anarchism – has been the purist anxiety about state power. Instead of using the limitations of state power to argue for better management of the state, post-Marxist thought has argued against any attempt to secure power over the state. This is an argument made from privilege by those who do not have to suffer the obstinate facts of hunger and illiteracy, who claim that small-scale forms of mutual aid or charity are not ‘authoritarian’, like state projects to eradicate hunger. This is an argument of purity that ends up renouncing any possibility of abolishing the obstinate facts of hunger and other assaults on human dignity and well-being. In the poorer countries, where small-scale forms of charity and mutual aid have a negligible impact on the enormous challenges before society, nothing less than the seizure of state power and the use of that power to fundamentally eradicate the obstinate facts of inequality and wretchedness is warranted. To approach the question of socialism requires close consideration of the political forces that must be amassed in order to contest the bourgeoisie for ideological hegemony and for control over the state. These forces experienced a pivotal setback when neoliberal globalisation reorganised production along a global assembly line beginning in the 1970s, fragmenting industrial production across the globe. This weakened trade unions in the most important, high-density sectors and invalidated nationalisation as a possible strategy to build proletarian power. Disorganised, without unions, and with long commute times and workdays, the entire international working class found itself in a situation of precariousness. 4 The International Labour Organisation refers to this sector as the precariat – the precarious proletariat. Disorganised forces of the working class and the peasantry, of the unemployed and the barely employed, find it virtually impossible to build the kind of theory and confidence out of their struggles needed to directly confront the forces of capital. One of the key lessons for working-class and peasant movements comes from the struggles being incubated in India. For the past decade, there have been general strikes that have included up to 300 million workers annually. In 2020–2021, millions of farmers went on a year-long strike that forced the government to retreat from its new laws to uberise agricultural work. How were the farmers’ movement and the trade union movement able to do this in a context in which there is very low union density and over 90% of the workers are in the informal sector? 5 Because of the fights led by informal workers – primarily women workers in the care sector – trade unions began to take up the issues of informal workers – again, mainly women workers – as issues of the entire trade union movement over the course of the past two decades. Fights for permanency of tenure, proper wage contracts, dignity for women workers, and so on produced a strong unity between all the different fractions of workers. The main struggles that we have seen in India are led by these informal workers, whose militancy is now channelled through the organised power of the trade union structures. More than half of the global workforce is made up of women – women who do not see issues that pertain to them as women’s issues , but as issues that all workers must fight for and win. This is much the same for issues pertaining to workers’ dignity along the lines of race, caste, and other social distinctions. Furthermore, unions have been taking up issues that impact social life and community welfare outside of the workplace, arguing for the right to water, sewage connections, education for children, and to be free from intolerance of all kinds. These ‘community’ struggles are an integral part of workers’ and peasants’ lives; by entering them, unions are rooting themselves in the project of rescuing collective life, building the social fabric necessary for the advance towards socialism.  Alirio Palacios (Venezuela), Muro público (‘Public Wall’), 1978. Oil on canvas, 180 x 200 cm. Thesis Four: Return to the Source . It is time to recover and return to the best of the national liberation Marxist tradition. This tradition has its origins in Marxism-Leninism, one that was always widened and deepened by the struggles of hundreds of millions of workers and peasants in the poorer nations. The theories of these struggles were elaborated by people such as José Carlos Mariátegui, Ho Chi Minh, EMS Namboodiripad, Claudia Jones, and Fidel Castro. There are two core aspects to this tradition: - From the words ‘national liberation’, we get the key concept of sovereignty . The territory of a nation or a region must be sovereign against imperialist domination.

- From the tradition of Marxism, we get the key concept of dignity . The fight for dignity implies a fight against the degradation of the wage system and against the old, wretched, inherited social hierarchies (including along the lines of race, gender, sexual orientation, and so on).

Thesis Five: ‘Slightly Stretched’ Marxism . Marxism entered the anti-colonial struggles not through Marx directly, but more accurately through the important developments that Vladimir Lenin and the Communist International made to the Marxist tradition. When Fanon said that Marxism was ‘slightly stretched’ when it went out of its European context, it was this stretching that he had in mind. 6 Five key elements define the character of this ‘slightly stretched’ Marxism across a broad range of political forces: - It was clear to the early Marxists that liberalism would not solve the dilemmas of humanity, the obstinate facts of life under capitalism (such as hunger and ill-health). Not one capitalist state project put the solution to these dilemmas at the heart of its work, leaving it instead to the charity industry. The capitalist state projects pushed the idea of ‘human rights’ to abstraction; Marxists, on the other hand, recognised that only if these dilemmas are transcended can human rights be established in the world.

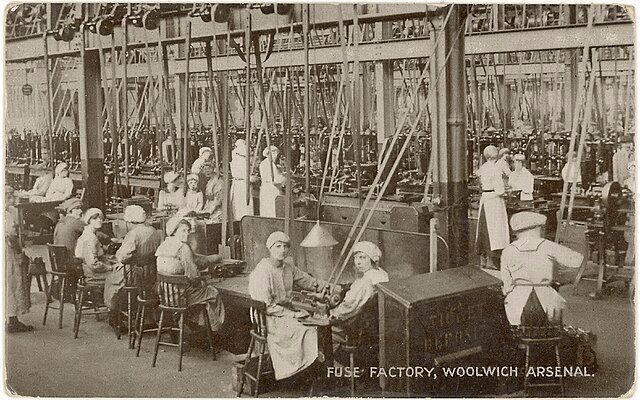

- The modern form of industrial production is the precondition for this transcendence because only it can generate sufficient social wealth that can be socialised. Colonialism did not permit the development of productive forces in the colonised world, thereby making it impossible to create sufficient social wealth in the colonies to transcend these dilemmas.

- The socialist project in the colonies had to fight against colonialism (and, therefore, for sovereignty) as well as capitalism and its social hierarchies (and, therefore, for dignity). These remain the two key aspects of national liberation Marxism.

- Due to the lack of development of industrial capitalism in the colonies, and therefore of a large enough number of industrial workers (the proletariat), the peasantry and agricultural workers had to be a key part of the historical bloc of socialism.

- It is important to register that socialist revolutions took place in the poorer parts of the world – Russia, Vietnam, China, Cuba – and not in the richer parts, where the productive forces had been better developed. The dual task of the revolutionary forces in poorer states that had won independence and instituted left governments was to build the productive forces and to socialise the means of production. The governments in these countries, shaped and supported by public action, had a historical mission far more complex than anything envisaged by the first generation of Marxists. A new, boundless Marxism emerged from these places, where an experimental attitude towards socialist construction emerged. However, many of these developments in socialist construction were not elaborated into theory, which meant that the theoretical tradition of national liberation Marxism was not fully available to contest both the post-Marxist and post-colonial assault on socialist praxis in the Third World.