An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Effects of Reading Interventions Implemented for Upper Elementary Struggling Readers: A Look at Recent Research

Rachel e. donegan.

Northern Illinois University

Jeanne Wanzek

Vanderbilt University

In this study, we conducted a review of reading intervention research (1988–2019) for upper elementary struggling readers and examined intervention area (e.g., foundational, comprehension, or multicomponent) and intensity (e.g., hours of intervention, group size, and individualization) as possible moderators of effects. We located 33 studies containing 49 treatment-comparison contrasts, found small effects for foundational reading skills ( g = 0.22) and comprehension ( g = 0.21), and decreased effects when considering standardized measures only. For intervention area, only multicomponent interventions predicted significant effects for both comprehension and foundational outcomes. For intensity, we did not find systematic evidence that longer or individualized interventions were associated with larger effects. However, interventions implemented in very small groups predicted larger comprehension outcomes. Overall, more research examining the quality of school provided reading instruction and how the severity of reading difficulties may impact effects of more intensive interventions is needed.

The upper elementary grades represent a critical time in literacy development. There are several advancements expected of students as they transition from the early elementary to late elementary grades. Students are expected to read texts that increasingly include longer, more difficult words ( Hiebert, 2008 ). In addition, students are expected to read and comprehend expository text which they may have had little exposure to earlier in their schooling ( Duke, 2000 ) and which poses unique and increasing challenges to comprehension ( Duke & Roberts, 2010 ). These challenges that emerge as students transition from the primary to upper elementary grades can contribute to continued reading difficulties for students who struggled with reading in the primary grades and also may be associated with the appearance of new, late-emerging reading difficulties for other students leading to a substantial population of struggling readers as students progress to their last years in elementary school ( Compton, Fuchs, Fuchs, Elleman, & Gilbert, 2008 ; Lipka, Lesaux, Siegel, 2006 ).

Upper elementary struggling readers are unique from those found in the primary grades and consequently may require specialized and diverse intervention approaches. In contrast to struggling readers in the primary grades where word reading difficulties account for the majority of the reading problems ( Nation & Snowling, 1997 ; Shankweiler et al., 1999 ), older struggling readers may demonstrate difficulties in foundational skills such as word reading, or more advanced skills such as comprehension of text, or they may struggle in both domains ( Leach, Scarborough, Rescorla, 2003 ; Lipka et al., 2006 ). According to the Simple View of Reading, deficits in either domain can severely impact overall reading performance ( Gough & Tumner, 1986 ).

In order to address the diverse reading needs of this group of struggling readers, interventions that focus on foundational skills or comprehension as well as multicomponent interventions that include instruction in both domains may all be needed. Foundational skill interventions include instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics and word recognition, and/or fluency. Effective phonics instruction for older struggling readers should go beyond the decoding of single syllable words to include strategies for decoding multisyllabic such as using syllabication and word parts (e.g., roots and affixes) to break apart and decode longer words ( Boardman et al., 2008 ). Repeated reading, where students read the same passage multiple times while receiving feedback and teacher or peer support, and nonrepetitive reading, where students receive the same feedback and supports but read one or more texts without additional readings, are two types of fluency interventions that have both been shown effective for improving struggling readers’ foundational reading skills ( Lee & Yoon, 2017 ; Zimmerman, Reed, & Aloe, 2019 ).

Explicit vocabulary instruction and comprehension strategy instruction are two effective approaches for improving the reading comprehension of older struggling readers ( Elleman, Lindo, Morphy, & Compton, 2009 ; Kamil et al., 2008 ). Direct instruction in word meaning that goes beyond definition teaching to include deep processing activities including generating examples and nonexamples and creating semantic maps are effective for increasing the vocabulary knowledge of older struggling readers ( Bryant, Goodwin, Bryant, & Higgins, 2003 ). When it comes to comprehension strategy instruction, three particular areas that show consistent positive effects for older struggling readers are learning strategies for identifying the main idea, summarizing the text, and self-regulating or monitoring learning strategies while reading ( Wanzek, Wexler, Vaughn, & Cuillo, 2010 ; Solis et al., 2012 ).

Multicomponent interventions that include instruction in both foundational and comprehension skills have shown promise for students in the upper elementary grades according to a review by Wanzek et al. (2010) . These interventions combine effective instruction across components making them well-aligned to the needs of older struggling readers who tend to have difficulties across reading domains. However, there were few studies examining multicomponent interventions at the time of the review. In addition, since the Wanzek et al. review, more research examining multicomponent reading interventions for upper elementary students with reading difficulties has been conducted.

Intensive Interventions

It may also be important to consider features of intervention intensity such as implementation intensity (e.g., total duration and group size) and individualization when considering intervention approaches for older struggling readers since these readers may demonstrate persistent reading difficulties or present reading skills that are far below those of their peers.

There has been limited work examining the effects of reading interventions implemented for different durations and in different sized groups for older students and the results have been mixed. One recent study examining the effects of intervention duration for late elementary students, those randomly assigned to two years of intervention demonstrated stronger word reading skills than those randomly assigned to receive intervention for only one year; however, these effects did not extend to comprehension outcomes ( Miciak et al., 2018 ). Another study examining impact of group size on middle school struggling readers found a pattern of effects favoring students randomly assigned to smaller groups for decoding and spelling outcomes but these differences were not statistically significant ( Vaughn et al., 2010 ).

Previous work has demonstrated individualized interventions that include instruction designed to address individual student need may be effective for elementary and secondary students who have failed to respond adequately to previous interventions ( Denton et al., 2013 ; O’Connor, Fulmer, Harty, & Bell, 2005 ; Pyle & Vaughn, 2012 ). However, there hasn’t been conclusive evidence that individualized interventions have added value over standardized interventions where instruction is consistent across students. For example, a study by Vaughn et al. (2011) compared reading outcomes of middle school struggling readers randomly assigned to a standardized intervention, individualized intervention, or business as usual comparison group and found both intervention groups similarly outperformed the comparison group on decoding, fluency and comprehension.

In summary, fourth and fifth grade struggling readers present diverse reading needs. Due to these diverse needs, a broad range of interventions have been developed. When examining the effects of interventions, in addition to considering instructional content, a closer look at intensity when considering intervention effects may be needed, especially for students with intensive reading needs.

Several researchers have examined reading intervention research for older students, including students in the upper elementary grades. Flynn, Zheng, & Swanson (2012) synthesized the effects of reading interventions for students in Grades 5 to 9 with reading disabilities and reported small to moderate effects across outcomes but noted few studies examined comprehension or multicomponent interventions. Outcomes did not differ significantly by type of intervention or duration of intervention. Scammacca, Roberts, Vaughn, & Stuebing (2015) used meta-analytic techniques to analyze the effects of reading interventions for older students (grades 4–12) and found a mean effect size of 0.49 for all measures as well as an effect of 0.21 for standardized reading outcomes. The authors noted that the effects of interventions decreased across year of publication with more recent studies demonstrating smaller effects, suggesting a trend of diminishing effects. Scammacca and colleagues also reported some moderation of outcomes by intervention type, with vocabulary interventions resulting in higher effects than other types of interventions. Comprehension interventions were also found to have a significantly higher mean effect size than fluency or multicomponent interventions. The number of hours of intervention was not a significant moderator of outcomes for more recent studies.

Wanzek et al. (2013) examined the research on interventions with 75 or more sessions for students with reading difficulties in Grades 4 to12. Overall effects were reported as 0.10 for comprehension outcomes, 0.16 for reading fluency outcomes, 0.16 for word fluency outcomes, and 0.15 for spelling outcomes with only comprehension outcomes having significant variation across studies. The authors reported no significant moderation of the comprehension outcomes by group size or number of hours of intervention.

These research syntheses combined research on interventions for students in the upper elementary grades with the middle and secondary grades. Although no moderation by grade level was reported, outcomes and moderators of outcomes can vary dramatically across this wide range of grade levels ( Pearson, Palinscar, Biancarosa, & Berman, 2020 ), making it difficult to ascertain the implications specifically for upper elementary students. Wanzek et al. (2010) conducted a comprehensive review of school-based reading intervention research for students in Grades 4 and 5. They located 13 studies that used between group treatment-comparison designs. Out of these 13 studies, five focused on comprehension interventions with medium to very large mean effects reported, six studies focused on foundational skills with small to moderate effects reported for word study interventions specifically, and two studies focused on multicomponent interventions with medium to large effects reported. Overall, there were positive effects for reading interventions provided to upper elementary struggling readers. However, there were a small number of studies available overall, and the authors noted limitations of some of the studies including the use of unstandardized, researcher-developed measures to evaluate the effects of comprehension and vocabulary interventions. These types of measures are often associated with larger effects when compared to standardized, norm-referenced outcomes ( Edmonds et al., 2009 ; Scammacca et al., 2015 ) and only provide information on outcomes closely aligned with the intervention rather than more generalizable outcomes. In addition, Wanzek et al. reported there were few studies on multicomponent interventions.

Since Wanzek’s et al.’s (2010) earlier review, several large-scaled randomized control trials focusing on late elementary struggling readers have been completed. This more robust research base along with Scammacca et al.’s (2015) finding of a trend of diminishing effects for more recent studies, and the unique and changing needs of struggling readers as they transition to the late elementary grades warrant an updated review of the research on reading interventions for late elementary students. The purpose of this review is to update and extend the earlier synthesis by Wanzek and colleagues (2010) for upper elementary struggling readers. To do this, we conducted updated searches to identify reading intervention research with late elementary students published since 2007. To extend the work, we carried out a statistical analysis of effects of intervention on reading outcomes, examining how intervention areas and intensity may have moderated effects. We sought to answer the following research questions:

- What are the effects of reading interventions for fourth and fifth grade struggling readers?

- How are effects moderated by intervention areas and intensity?

Inclusion Criteria

We adapted Wanzek et al.’s (2010) inclusion criteria for this review. In order to be included in this review, studies had to meet the following criteria:

- A reading intervention targeting literacy in English for students struggling with reading was provided. Reading interventions provided to all students as a part of the general education curriculum were excluded.

- The reading intervention included instruction in word study, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, or a combination of these components and was provided in a school setting. Programs conducted in home, clinic, or camp settings were excluded.

- Participants in the reading intervention were described by study authors as below grade level in reading, at risk for reading disabilities or difficulties, or identified with reading disabilities or disaggregated data for these readers was provided. Studies that included participants with sensory or intellectual disabilities were excluded.

- More than 50% of participants were in fourth or fifth grade (9 to 11 years old) or disaggregated data for these participants was provided.

- Interventions were provided for a minimum of 15 sessions.

- Study outcomes included at least one measure of reading.

- The study used an experimental or quasi-experimental design where effects of intervention were compared across groups, and data for calculating effect sizes were provided. Quasi-experimental studies had to either include evidence of baseline equivalence or use a group assignment procedure to equate group (e.g., matched-pairs).

- The study was published in English in a peer-reviewed journal.

Search and Screening Procedures

In order to identify studies for this review, we both conducted updated searches and identified studies included Wanzek’s et al., (2010) earlier review that met our inclusion criteria. In order to identify articles published since Wanzek and colleagues (2010) review, we followed a three-step search process. First, we conducted a search of three electronic databases, ERIC, Education Full Text, PsycINFO. We used search terms combining key words for reading ( read* ), struggling readers (reading difficult*, learning disabilit*, dyslexi*, learning problem*, reading failure, language impair*, reading disability*, low-achieving ) and reading intervention (remedial reading, teaching methods, reading NEAR/4 intervention*, reading education, special education ). Since the purpose of this search was to identify studies published since the original review, we limited results to documents from 2007 to 2019. Second, to identify recently published articles, we conducted a hand search of major journals that frequently publish reading intervention research ( Exceptional Children, Journal of Educational Psychology, Journal of Learning Disabilities, Journal of Special Education, Learning Disabilities Quarterly, Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, Reading and Writing, Remedial and Special Education, Scientific Studies of Reading ) for articles published online or in print in 2018 and 2019. Finally, ancestral searches were conducted of identified articles that met all inclusion criteria.

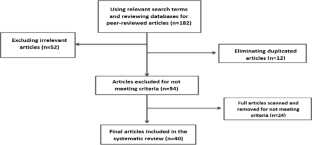

Using these search procedures, 5,100 articles were identified. Articles identified from the electronic and hand search were screened using a two-step process (see Figure 1 ). First, abstracts of identified articles were screened. After conducting the abstract screening, the full text of the remaining articles was screened. Common reasons articles were eliminated included during the abstract screen and full text screen were the majority of participants were outside fourth or fifth grades or a reading intervention was not provided. In total, 25 articles published since the original review were identified for inclusion.

Prisma diagram.

Note . *One article described two studies

Next, we screened articles included in the original review for inclusion. Out of the 12 articles detailing treatment/comparison design studies included in the original review, seven articles describing eight studies met all inclusion criteria and were included. Three articles were excluded because they did not include information to calculate effect sizes and two articles were excluded because the intervention provided targeted literacy in a language other than English. In total, this left 33 studies identified for inclusion in this review.

In order to systematically capture study information, we developed a code sheet that included information on participants; study design and quality; measures including the component skill measured (foundational or comprehension) and if the measure was a norm-referenced, standardized reading outcome or an unstandardized measure such as an experimenter created measure, a skill inventory, or informal diagnostic measure closely aligned to the intervention; intervention areas including if the intervention included instruction in foundational reading skills only (phonemic awareness, phonics, or fluency), comprehension only (vocabulary and comprehension) or was multicomponent including instruction across both foundational skills and comprehension; intervention intensity including total hours of intervention, group size, and individualization; and reading outcomes. Studies were identified as including individualized instruction if any of the instructional targets or materials used in the intervention were initially planned and adjusted during the course of the intervention based on individual student progress. Due to reporting by some study authors of group size and hours of intervention as a range, these study characteristics were coded categorically. For group size, studies were coded according to the maximum group size reported (or average group size if maximum size was not reported) by the authors and were coded as implemented in group sizes of one or two, group sizes of four to seven, or groups of nine or more. For hours of intervention, studies were coded as having an intervention of 15 or fewer hours, 16 to 30 hours, or more than 30 hours. If the information described above was not included in the article, the first author of the article was contacted to request the information.

All studies were coded by the first author. To assess interrater reliability, two advanced doctoral students were trained in screening and coding procedures. Training included reviewing inclusion criteria and identifying articles that met did not meet inclusion criteria, reviewing the codebook and coding sample articles to reach a minimum of 90% reliability. Then, we randomly selected 20% of articles from both the abstract screen and full text screen to be double screened. Interrater reliability was 93% for the abstract screening and 92% for the full text screening. We randomly selected 13% of included articles to be double coded. Interrater reliability was 100% across all sections of the code sheet.

Meta-analytic Methods

Several of the identified articles included multiple treatment groups, resulting in a total of 49 treatment/comparison contrasts. These were analyzed separately for foundational and comprehension outcomes. Effect sizes were calculated with post-test mean and standard deviations using the Campbell Collaborative Calculator ( Wilson, n.d. ). The calculator provided Cohen’s d effect sizes. For one study ( Reed, Aloe, Reeger, & Folsom, 2019 ), we used author reported effect sizes and variances in the absence of post-test means and standard deviations. All effect sizes were converted to Hedges g using the following formula

where n 1 and n 2 correspond to the number of participants in each group and df equals the total number of participants minus the number of groups. For studies with multiple effect sizes, we computed the average effect size for foundational and comprehension outcomes, weighting the averages by the sample size.

We examined the effect sizes for the presence of outliers by constructing stem and leaf plots. In order to assess the presence and magnitude of heterogeneity in effect sizes, we calculated Q , τ 2, , I 2 statistics. In order to analyze effects, we used a weighted regression using a random effects model. We calculated weights for each effect size using the following formula

where σ 2 refers to the subject sampling variance estimate and τ 2 refers to the between study variance. We applied these weights when conducting the regression. We assessed the impact of the following moderators: type of measure (standardized or unstandardized), intervention components (foundational, comprehension, or multicomponent), and intensity (group size, hours of intervention, individualization).

Participants

The 33 studies included 4565 total participants. Participants included readers with and at risk for disabilities and students generally classified as struggling readers and therefore included a broad range of reading abilities (see Table 1 ). Across studies, on average 55% of participants were male and 45% of participants were female.

Intervention Descriptions and Outcomes

Note . T = Treatment; C = Comparison; Avg. = Average; Found. = Foundational; PA = Phonological awareness; WR & S = Word reading and spelling; Comp. = Comprehension; Vocab. = Vocabulary; GMRT = Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test; WRMT = Woodcock Reading Mastery Test; TOWRE = Test of Word Reading Efficiency; TOSREC = Test of Silent Reading Efficiency and Comprehension; PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test;

Forty-seven interventions were implemented across 49 treatment/comparison contrasts in the included studies (see Table 1 ). Out of the 49 contrasts, 38 contrasted a reading intervention with typical school reading instruction only. Typical school reading instruction consisted of core reading instruction for all students and also may have consisted of school provided intervention to some students in treatment and/or comparison groups as schools deemed necessary. In three contrasts, a researcher-provided intervention was compared with an active control condition ( Keller, Ruthruff, & Keller, 2019 ) or an alternative researcher-provided intervention ( Ring, Barefoot, Avrit, Brown, & Black, 2013 ; Torgesen et al., 2001 ). In three contrasts, a researcher-provided intervention was compared to a school-provided intervention ( Kim, Capotosto, Hartry, & Fitzgerald, 2011 ; Kim, Samson, Fitzgerald, & Hartry, 2010 ). In two contrasts, a teacher provided intervention was compared to a different teacher provided intervention ( Das, Hayward, Georgiou, Janzen, & Boora, 2008 ; Xin & Rieth, 2001 ). In two contrasts, a researcher-provided intervention was compared to a previously received intervention ( Das, Mishra, & Pool, 1995 ).

Intervention Implementation

Most interventions were implemented by researchers ( n = 33). The remaining were implemented by in-service or pre-service teachers ( n = 10), paraeducators ( n = 2), or volunteers ( n = 1). The majority of the interventions ( n = 20) were multicomponent, 16 focused on foundational skills only, and 11 included instruction in comprehension only. In order to assess the intensity of the implemented intervention, we analyzed the total hours of intervention, group size, and if any aspect of the intervention was individualized (see Table 2 ). Most interventions ( n = 17) included more than 30 hours of instruction. Out of the five interventions implemented for the most hours, three were after-school or summer programs ( Kim et al., 2010 ; Kim et al., 2011 ; Reed et al., 2019 ), one included two daily intervention sessions ( Torgesen et al., 2001 ), and one implemented a reading intervention across two school years ( Miciak et al., 2018 ).

Study Characteristics

Note . Q = Quasi-experimental; E = Experimental; SWD = Students with disabilities; Indiv. = Individualized

Group size varied widely across the interventions. Most interventions ( n = 22) were implemented in small groups with a maximum group size between four to seven students. Two studies that implemented interventions with the largest groups also included limited time for practice and instruction in smaller groups ( Kim et al., 2011 ; Reed et al., 2019 ).

Eleven interventions included at least some individualization of instruction during the intervention. Out of these, only one intervention included individualization throughout instruction ( Thames et al., 2008 ). The remaining interventions included individualization in specific components of the intervention but not for the full intervention. These included computerized multicomponent practice ( Kim et al., 2010 ; Kim et al., 2011 ; Roberts et al., 2018 ), word study instruction ( Miciak et al., 2018 [two interventions]; Vaughn, Solís, Miciak, Taylor, & Fletcher, 2016 ), fluency instruction (Young, Mohr, Rasinski, 2015), brief multicomponent small group instruction (provided in addition to larger group instruction that was not individualized; Reed et al., 2019 ), or individualized texts based on student performance ( O’Connor et al., 2002 ; Therrien, Wickstrom, & Jones, 2006 ).

Meta-Analytic Results

In this section, we report the meta-analytic results, including mean effects and variance explained, both overall for foundational and comprehension outcomes and for each moderator. We initially interpret effect sizes as small, medium, or large using benchmarks suggested by Cohen (1988) though more nuanced interpretation of these effects in comparison to effects from similar studies are found in the discussion.

Foundational outcomes.

There were 46 effects for foundational outcomes. We constructed a stem and leaf plot to detect outliers (see Figure 2 ) and found two effect sizes at the top end of the distribution from unstandardized reading outcomes. We retained these effect sizes and used a moderator analysis to further investigate differences in effects between standardized and unstandardized reading outcomes.

Stem and leaf plot of foundational outcome effect sizes

The estimated mean effect across all studies was g = 0.22 ( p < .001, 95% CI [0.10, 0.33]) indicating a small positive and significant effect of reading interventions on foundational reading outcomes. The Q statistic indicated heterogeneity was present ( Q total = 159.44, df = 45, p < .001). Further analysis indicated large heterogeneity ( I 2 = 71.78, τ 2 = 0.10). In order to determine if there was a difference in effects for standardized versus unstandardized reading outcomes, we entered outcome type into the regression equation as a predictor. Outcome type explained a significant amount of heterogeneity ( Q between = 21.02, df = 1, p < .001) and thus was a predictor of effects. Unstandardized outcomes were associated with large, positive effects ( g = 0.83, SE = .014, p < .001; β = 0.73, p < .001). For standardized outcomes, the mean effect was smaller and nonsignificant (see Table 3 ).

Foundational Outcomes

Next, we determined the mean effect size and significance for each moderator when entered into the regression separately (see Table 3 ). Then we entered all moderators into the equation together to determine which moderators predicted unique variance in effect sizes. For intervention components, small, positive effects were found for multicomponent interventions ( g = 0.16, SE = 0.08, p = .04) and were significantly different from outcomes for foundational and comprehension interventions ( β = 0.16, SE = 0.08, p = .04). The effect sizes for foundational interventions, though also small and positive ( g = 0.36, SE = .13, p < .01), did not predict unique effects when compared to interventions with other components. For group size, interventions implemented in instructional groups of four to seven predicted small effects ( g = 0.25, SE = 0.08, p = .002; β = 0.25, p = .002). Interventions implemented for 16 to 30 hours were associated with small, positive effects ( g = 0.35, SE = 0.14, p = .01), although these effects were not unique from interventions of different durations. Finally, interventions that were not individualized predicted small, positive effects ( g = 0.25, SE = 0.07, p < .001; β = 0.25, p < .001) that were more consistent than effects from individualized interventions.

When all predictors were entered together into the regression equation, a significant portion of heterogeneity was explained ( Q between = 24.00, df = 12, p = .02). Outcome type was the only predictor of unique effects on foundational outcomes with larger effects for unstandardized outcomes ( β = 0.68, SE = 0.17, p < .001).

Comprehension outcomes.

There were 53 effect sizes for comprehension outcomes. We used the same procedure to detect outliers (see Figure 3 ). We did not detect any outliers but followed the same procedure and used a moderator analysis to further investigate differences in effects.

Stem and leaf plot of comprehension outcome effect sizes

The estimated mean effect was g = 0.21 ( p < .001, 95% CI [0.12, 0.30]) indicating a small positive, significant effect of reading interventions on comprehension reading outcomes. The Q statistic indicated significant heterogeneity ( Q total = 113.41, df = 52, p <.001). Further analysis indicated medium heterogeneity ( I 2 = 54.15, τ 2 = 0.05). We used the same procedure to determine if there was a difference in effects by outcome type and found a significant amount of heterogeneity explained ( Q between = 9.05, df = 1, p = .003). Outcome type was a significant predictor of effects. Both outcome types predicted significant effects with unstandardized outcomes predicting larger effects ( g = 0.44, SE = 0.10, p < .001; β = 0.30, p = .003) than standardized outcomes ( g = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p = .009; β = 0.13, p = .009).

We used the same procedure to calculate mean effect sizes and determine significance for each moderator (see Table 4 ). For intervention components, multicomponent interventions predicted small, positive effects ( g = 0.17, SE = 0.06, p = .004; β = 0.17, p = .004). Though small, positive effects were also noted for comprehension interventions ( g = 0.29, SE = 0.10, p = .003), these interventions did not predict unique effects when compared to interventions with different components. Group size predicted effects. Interventions implemented in groups of one or two students predicted the largest effects with medium, positive effects noted ( g = 0.50, SE = 0.10, p < .001; β = 0.41, p < .001) while mean effect sizes for larger groups were nonsignificant. Interventions that included 15 or fewer hours of instruction predicted unique effects on comprehension outcomes with medium, positive effects noted ( g = 0.44, SE = 0.12, p < .001; β = 0.28, p = .02); however, this finding is limited due to five of the 14 effect sizes for this moderator related to unstandardized outcomes. Interventions that more than 30 hours predicted unique effects with small, positive significant effects noted ( g = 0.16, SE = 0.07, p = .01; β = 0.16, p = .01). Interventions that were not individualized predicted small, positive effects on comprehension outcomes that were more consistent than effects from individualized interventions ( g = 0.25, SE = 0.05, p < .001; β = 0.25, p < .001).

Comprehension Outcomes

When all predictors were entered together into the regression equation, a significant portion of heterogeneity was explained ( Q between = 28.86, df = 12, p = .004). Group size was the only unique predictor of comprehension outcomes with very small groups (one or two students) predicting positive, larger effects ( β = 0.44, SE = 0.12, p < .001).

Year of publication.

The studies included in the review were published over more than 3 decades (1988–2019), and other investigators have found year of publication moderated effects ( Austin et al., 2019 ; Scammacca et al., 2015 ). Thus, we completed an exploratory analysis on the effect of year of publication on both foundational and comprehension outcomes by entering it into the regression equation as a predictor. We found year of publication explained a significant portion of heterogeneity and was a significant predictor of effect size for comprehension outcomes only with more recent studies associated with smaller effects ( Q between = 5.20, df = 1, p = .02; β = −0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .02).

Publication bias.

In order to assess publication bias, we used analysis of visual displays of effect sizes and a statistical analysis. First, we constructed funnel plots by plotting each study’s effect size against an estimate of the study size and visually analyzed the plots for symmetry. Then we used Egger’s linear regression method to statistically evaluate the symmetry of the plots by regressing the standardized effect sizes on their precisions ( Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997 ). An intercept including zero and symmetrical plots with an equal dispersal of studies on both sides of the overall mean effect would indicate no publication bias. An intercept not including zero and asymmetry in the plots would indicate the possible presence of publication bias. For foundational outcomes, the funnel plot did not show significant asymmetry ( p = .27) indicating a lack of evidence of publication bias for these outcomes. For comprehension outcomes, the funnel plot did show significant asymmetry ( p < .001). Visual inspection showed smaller studies smaller studies with low or negative effects missing indicating some evidence of publication bias. Thus, the reported effect size for comprehension outcomes may be inflated.

Wanzek et al. (2010) synthesized the results of reading intervention research for upper elementary students with reading difficulties or disabilities conducted from 1988 to 2007 and found small to moderate effects for foundational interventions, medium to large effects for comprehension interventions, and medium to large effects for multicomponent interventions. The goal of this study was to update and extend Wanzek’s et al.’s earlier review by conducting a meta-analytic review, including studies published since 2007, and examining intervention components and intensity as potential moderators of effects.

Overall, we found positive effects of upper elementary reading interventions for foundational and comprehension reading outcomes, but effects that were smaller than those described in Wanzek et al.’s (2010) review. When it comes to interpreting the magnitude of effects, Lipsey et al. (2012) recommend comparing effects to those obtained in similar interventions to interpret magnitude. The mean effects of our study may best be compared to the results of Scammacca et al.’s (2015) findings for reading interventions studies with fourth to 12 th grade students conducted from 2005–2011 since the majority of our effects come from studies published since 2005. Scammacca et al. report mean effects of g = 0.23 across all reading outcomes, g = 0.21 across all reading comprehension outcomes, and g = 0.13 across all standardized reading outcomes. We found effects of similar magnitude with overall mean effects from g = 0.21 to 0.22 for all reading outcomes and mean effects from standardized outcomes ranging from g = 0.09 to 0.13.

Also similar to Scammacca et al. (2015) , we noted a trend of diminishing effects where the effects in this examination were smaller than those in past reviews focused on similar age students ( Wanzek et al., 2010 ; Flynn et al., 2012 ). In fact, several recent, large scale, high quality studies included in this review reported null effects for standardized reading outcomes ( Connor et al., 2018 ; Roberts et al., 2018 ; Vaughn et al., 2016 ; Vaughn, Roberts, Miciak, Taylor, & Fletcher, 2019 ; Wanzek & Roberts 2012 ). To further investigate this trend of diminishing effects, we examined if more recent publications were associated with smaller effects by analyzing year of publication as a potential moderator. We found more recent publications associated with smaller effects for comprehension outcomes only. These diminishing effects for comprehension may be due to increased study quality in more recent investigations ( Austin et al., 2019 ).

However, we did not find a similar relation between year of publication and effect size for foundational outcomes. Descriptively, we did note several differences in participants from the that may be important to note alongside our findings as possible explanations. Across the studies from Wanzek’s earlier review, on average participants earned a standard score of 81 in foundational reading skills at pretest. In the more recent studies published since Wanzek’s earlier review, participants on average demonstrated stronger foundational reading skills with an average standard score of 90 at pretest. It’s possible that this improved performance was due to students receiving better reading instruction or more students receiving reading intervention from their schools. Others have noted improved classroom reading instruction as a potential explanation of diminishing effects ( Lemons, Fuchs, Gilbert, & Fuchs, 2014 ). However, information included in studies on classroom reading instruction and school-based reading interventions was often limited.

Another possible explanation considers the population targeted in the more recent studies. Not only did the students in the more recent studies enter with better foundational reading skill, less of them were also identified with disabilities. Of the eight studies included in Wanzek’s earlier review, seven included a majority of participants with disabilities (see Table 2 ). Out of the 17 recent studies that gave information regarding participant disability status, only 3 studies included a majority of participants with identified disabilities.

It is critical to note, these explanations are speculative. More detailed examinations of school-provided interventions, core reading instruction, and more complete reporting on student disability or at-risk status are needed and may shed light on the reasons behind the diminishing effects for standardized reading outcomes in comparison to effects reported in previous meta-analytic reviews.

Foundational reading

Foundational reading interventions predicted small, though not unique, effects ( g = 0.36) on all foundational reading outcomes. Across the studies, there were mixed effects for interventions focused solely on fluency with three interventions predicting small to medium, positive effects and 3 predicting negative effects. There were more consistent, positive effects for foundational interventions that included a combination of foundational reading components. Keller et al., (2019) reported large, positive effects for unstandardized reading outcomes for an intervention package that included computerized and researcher-provided instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, spelling, fluency, text reading strategies along with mindfulness training. Torgesen et al., (2001) reported small, positive effects for standardized reading outcomes for an intervention that included researcher provided instruction focused on phonemic awareness, encoding, and decoding at the word level.

Interventions including decoding focused on multisyllabic words such as structural analysis (breaking a word down into decodable parts by using affixes or syllables) have been found by others to be effective for improving the reading outcomes of older struggling readers ( Edmonds et al., 2009 ) and also showed promise in our review. Toste, Capin, Williams, Cho, & Vaughn (2019) implemented a rigorous high-quality study examining the effects of a foundational reading intervention focused on multi-syllabic word reading and showed the largest effects among the foundational reading interventions (ES = 0.51 to 0.75) and word reading outcomes (ES = 0.45 to 0.80). In addition, several multicomponent interventions that showed the strongest, positive effects for foundational reading outcomes included decoding instruction focused on the word-level and expanded to the text level ( Miciak et al., 2018 ; O’Connor et al., 2002 ; Ring et al., 2012; Vaughn et al., 2019 ). This systematic integration of decoding skills is also recommended as an effective approach for younger struggling readers as it helps build generalization of skills to other contexts (Gersten et al., 2009).

Comprehension

Comprehension interventions also predicted small, but not unique, effects on comprehension outcomes ( g = 0.29). Six interventions ( Cirino et al., 2017 ; Fuchs et al., 2018 ; Mason, Davison, Hammer, Miller, & Glutting, 2013 ) where small to medium positive effects were noted for comprehension outcomes all focused on strategy instruction including main idea and summarization. Strategy instruction, where comprehension strategies are taught using direct and explicit instruction has shown strong evidence of effectiveness for improving students’ reading comprehension ( Kamil et al., 2008 ; Shanahan et al., 2010 ). Main idea and summarization, two specific strategies, have also been widely and effectively used to improve the comprehension of older struggling readers specifically ( Solis et al., 2012 ).

Similar to Wanzek et al.’s (2010) earlier findings, multicomponent interventions predicted significant, positive and unique effects for both foundational and comprehension outcomes. Unlike Wanzek et al.’s earlier finding, the mean effect was small across both outcomes ( g = 0.16 for foundational; g = 0.17 for comprehension). This finding differs from Scammacca et al.’s (2015) finding where comprehension interventions predicted the strongest effects.

The density of comprehension and vocabulary instruction in several intervention studies included in this review provides a possible explanation ( Kim et al., 2011 ; Reed et al., 2019 ; Vadasy & Sanders, 2008 ; Wanzek et al., 2017 ). These multicomponent interventions may be better equipped to address the needs of the current population of struggling readers. In contrast to the studies from Wanzek’s earlier review where students tended to show more substantial deficits in foundational reading skills than comprehension, students in the more recent studies tended to show more substantial difficulties in comprehension than in foundational skills. In regards to the instruction included in the multicomponent interventions, although these interventions included instruction in foundational reading skills, there was also substantial, explicit and systematic comprehension and vocabulary instruction. For example, when instruction focused on text reading fluency, it frequently occurred alongside comprehension instruction. Therefore, the balance of components of instruction in these interventions may be better suited to the older struggling reader

In order to examine the effects of intervention intensity on reading outcomes, we examined hours of intervention, group size, and individualization as moderators. When examining effect of intervention duration and group size, we had mixed findings.

Group size was a significant moderator of comprehension outcomes. The smallest groups had the largest mean effects. This may be especially important as other investigators have noted comprehension as a difficult outcome to impact for older students (e.g., Vaughn et al., 2016 , Vaughn et al., 2019 , Miciak et al., 2018 ). Smaller groups may have afforded more opportunities for teacher and student conversations, more student specific feedback, and differentiation of instruction to meet individual student needs. Previous findings have also been mixed in the area of instructional group size. Wanzek et al. (2013) reported no moderation of student reading outcomes based on group size; however, group size could only be examined categorically with studies implementing instructional groups of 5 or less compared to studies implementing instructional groups of 6 or more. Flynn et al. (2012) noted small group instruction had a positive correlation with student outcomes, but the authors also noted interpretation is difficult because all of the studies with small groups also had other instructional components that may be related to student outcomes.

Longer duration interventions predicted significant effects for comprehension outcomes only, and these effects were small. In addition, this finding may be explained by intervention components as 15 out of the 19 interventions included were multicomponent. Recent syntheses of intervention research with students in older grade levels have also found the duration of intervention did not moderate student outcomes in the interventions (e.g., Flynn et al., 2012 ; Wanzek et al., 2013 ; Scammacca et al., 2015 ; though Scammacca found that older studies of shorter duration demonstrated higher effect sizes).

While there hasn’t been evidence that interventions with smaller groups or longer durations produce larger effects for older struggling readers broadly, there is evidence that these factors may matter for students with the most severe reading difficulties and disabilities, especially in accelerating foundational reading outcomes (e.g., Donegan, Wanzek, & Al Otaiba, 2020 ; Miciak et al., 2018 ; Sanchez & O’Connor, 2015 ). A few studies included in this review that implemented interventions for the longest durations (e.g., 60 hours or more) reported positive effects for students with severe reading difficulties and disabilities ( Miciak et al., 2018 ; Reed et al., 2019 ; Torgesen et al., 2001 ). Our findings related to the intensity moderators may have been different had there been enough studies to examine this population only.

Interventions that were not individualized showed more consistent effects than those that were individualized for both foundational and comprehension outcomes. Interventions described as individualized vary across the literature, both in how the individualization occurs and how much of the instruction is individualized. In order to capture the effects of different types and levels of individualization, we chose to define it broadly. Reading interventions were identified as individualized if any aspect of instruction was initially planned and adjusted throughout the intervention based on student learning. Using this definition, we identified 11 interventions as individualized, the vast majority of which described only specific components of instruction (e.g., word reading instruction, fluency instruction) as individualized and none of which used data-based individualization, one specific method of systematic and iterative intervention adjustment based on student data shown to be effective for improving student reading outcomes ( Jung, Mcmaster, Kunkel, Shin, & Stecker, 2018 ). It should be noted that student participants in four out of the 11 studies with individualized instruction demonstrated foundational reading skills at or below the 16 th percentile ( Miciak et al., 2018 ; O’Connor et al., 2002 ; Therrien et al., 2006 ; Vaughn et al., 2016 ), and two studies included more than 20% of participants with disabilities ( Kim et al., 2010 ; Reed et al., 2019 ). Therefore, it’s possible that these interventions were targeted to students with more significant needs which may account for the smaller effects.

Limitations, Implications and Future Directions for Research

As often is the case with research, many questions remain. First, it appears a trend of diminishing effects is continuing with smaller effects for standardized outcomes found in this review of recent reading intervention studies than in past reports. Improvements in school-provided core reading instruction and intervention and changing reading profiles of participating students offer possible explanations. However, more detailed examinations are needed to invest in either of these hypotheses. Second, there did not seem to be a systematic relationship between intervention duration and effects. Longer interventions may have been targeted to students with more intensive needs which may have impacted effects. One study ( Miciak et al., 2018 ) did offer preliminary evidence that longer interventions may be more effective than shorter ones for students with severe reading difficulties and disabilities. More experimental investigations of the impact of intervention duration for students in the grade range are needed in order for conclusions to be drawn. In addition, we found little evidence that individualized components or interventions offer added value. However, our investigation did not consider if these effects may have differed for students with the most severe reading difficulties and none of our studies used data-based individualization, one particular method of individualization shown to be effective. Finally, we did find some evidence of publication bias for comprehension outcomes. Although it appeared minimal, this may have resulted some inflation of mean effects for comprehension outcomes.

In summary, the results of this review suggest overall positive effects of reading intervention for upper elementary students; smaller, nonsignificant effects for standardized foundational reading outcomes; and small significant effects for standardized comprehension outcomes. According to the results of this review, multicomponent interventions show promise for improving foundational and comprehension reading outcomes. In addition, interventions implemented in very small groups may be an effective way to increase intensity and improve comprehension outcomes.

This research was supported in part by Grant H325H140001 from the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education and by Award Number R01HD091232 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Education.

Contributor Information

Rachel E. Donegan, Northern Illinois University.

Jeanne Wanzek, Vanderbilt University.

* Denotes studies included in this meta-analytic review

Action Research: What Can I Do to Improve the Reading Habits of Students?

Reading is critical to success both in school and life. It is a fundamental skill for children and adults alike. Like speech itself, it is the key to knowledge and opens up worlds. This action research aims to cultivate a reading habit of students. Uninterrupted Sustained Silent Reading (USSR) programme is the tool used to materialise this objective. The research samples are 21 students taken from Class IV of Gangrithang Primary School under Bumthang district. My experience in teaching and working at the Primary level for the last eighteen and half years as a teacher, made me to realized that student engagement particularly in reading books were not satisfactory as expected. This experience and realization has motivated me to take up an action research project to enhance reading habit of students. A questionnaire and a semi-structured interview schedule were used as the instruments of data collection. Findings reveal that out of 21 sampling 17 students confirmed USSR and teacher modeling are the most effective measure that can promote reading habits among students.

- Related Documents

Improving School Work in Challenging Context: Practitioners’ Views following a Participatory Action Research Project from Eritrea

This article is based on 18-month participatory action research (PAR) project conducted with teachers and school leadership personnel with strong backing of the regional education office in one of the remote and most culturally diverse regions in Eritrea. It argues for a comprehensive understanding of managing a learning process in challenging circumstances of schooling. Qualitative analysis was used to interpret 14 semi-structured interview transcripts of project participants from two study schools. A framework for understanding teaching as the intersection of knowledge of learners, processes of teaching and learning and subject matter is used. The analysis based on the interview data, longer term engagements with participants and review of relevant documents enabled authors to synthesize views of participants into five main professional perspectives: need to overcome transitory nature of teachers, knowledge of learners, proactive guidance, professional commitment, collaborative practices. Those issues arguably constitute quality education in the study schools and beyond.

Socio-personal and Economic Profile of Tribal Farmers Practicing Indigenous Technical Knowledge in Ranchi district of Jharkhand

The present study has been undertaken during 2019-2020 to appraise the socio-personal and economic profile of tribal farmers of Ranchi district of Jharkhand. Four villages were randomly selected from the two purposively selected blocks namely Tamar and Angara blocks of Ranchi district of Jharkhand state. The data were collected from 45 randomly selected tribal farmers practicing ITKs pertaining to pest and disease management by personal interviewing the respondents through a well tested structured interview schedule, who were considered as tribal key informants. The findings revealed that majority of the key informants were females (60%) belonging to old age group (71.11%) of Oraon community (46.66%). Majority of the respondents had education upto primary level only (31.12%), whereas about 30 per cent of them were either illiterate or could read and write only. Highest proportion of the key informants had marginal size of land holding with long farming experience (57.78%). Altogether one-third of the respondents had membership of only one organisation and 42.22 per cent of them were not associated with any formal organisation. Majority of the respondents had low level of risk-orientation (57.77%) and innovativeness (60%). Interventions on education, training and technology were suggested as the suitable measures for raising their socio-economic status.

A conceptual framework for advanced practice: an action research project operationalizing anadvanced practitioner/consultant nurse role

Transforming human services for wellness and social justice: a participatory action research project, exploring the fourth order.

Companies are organised to fulfil two distinctive functions: efficient and resilient exploitation of current business and parallel exploration of new possibilities. For the latter, companies require strong organisational infrastructure such as team compositions and functional structures to ensure exploration remains effective. This paper explores the potential for designing organisational infrastructure to be part of fourth order subject matter. In particular, it explores how organisational infrastructure could be designed in the context of an exploratory unit, operating in a large heritage airline. This paper leverages insights from a long-term action research project and finds that building trust and shared frames are crucial to designing infrastructure that affords the greater explorative agenda of an organisation.

Small meat lockers working group: a participatory action research project to revitalize the decentralized meatpacking sector in Iowa

Promoting social entrepreneurship in poor socio-economic contexts: evidence from an action research project in zimbabwe ─ southern africa, wonder-inspired leadership: cultivating ethical and phenomenon-led healthcare.

Three forms of leadership are frequently identified as prerequisites to the re-humanization of the healthcare system: ‘authentic leadership’, ‘mindful leadership’ and ‘ethical leadership’. In different ways and to varying extents, these approaches all focus on person- or human-centred caring. In a phenomenological action research project at a Danish hospital, the nurses experienced and then described how developing a conscious sense of wonder enhanced their ability to hear, to get in resonance with the existential in their meetings with patients and relatives, and to respond ethically. This ability was fostered through so-called Wonder Labs in which the notion of ‘phenomenon-led care’ evolved, which called for ‘slow thinking’ and ‘slow wondrous listening’. For the 10 nurses involved, it proved challenging to find the necessary serenity and space for this slow and wonder-based practice. This article critiques and examines, from a theoretical perspective, the kind of leadership that is needed to encourage this wonder-based approach to nursing, and it suggests a new type of leadership that is itself inspired by wonder and is guided by 10 tangible elements.

Facilitating neonatal MARSI evidence into practice: Investigating multimedia resources with Australian Neonatal Nurses – A participatory action research project

Creating change: developing a midwifery action research project, export citation format, share document.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Action Research on Reading Skills

Related Papers

Aysha Sharif

LINGUISTIKA

Deri Sis Nanda

Hannah Rose Aguila

This paper aims to assess the reading comprehension skills of Grade V pupils of Conde Elementary School in terms of critical, integrative, interpretative and literal level of reading. Students encounter trouble in decoding and recognizing words in the text. Several factors which greatly affect reading comprehension include the readers' knowledge of the topic, knowledge of language structures, knowledge of text structures and genre, knowledge of cognitive and metacognitive strategies, their reasoning abilities, their motivation and their level of engagement. The researchers utilized the descriptive type of research by using the validated questionnaire as a tool in gathering data. The findings revealed that, the pupil-respondents found difficulties in interpretative, critical analysis and integrative level of reading comprehension. Different reading activities and exercises could be employed to teach students explicit reading strategies and promote higher level of thinking skills.

IJMRAP Editor

A descriptive-quantitative research design was used and respondents were selected through stratified random sampling according to gender. There were 80 males and 74 females in primary levels on which 66 males (51.60%) and 62 females (48.40%) were selected as respondents for the study. Out of 128 respondents, 53 learners (41.40%) have self-employed parent or guardian, 39 learners (30.50%) have unemployed parent or guardian, 16 learners (12.50%) have government employee parent or guardian, 13 learners (10.20%) have private employee parent or guardian, and 7 learners (5.50%) have OFW parent or guardian. Most of the respondents are Yakan speaker learners (40.50%), followed by Binisaya speaker learners (25.80%) and the Tausug speaker learners (23.40%), and then the rest are Chavacano (7.80%) and Tagalog (2.30%) speaker learners. The oral reading and silent reading skills of primary learners were both on frustration level, while the listening comprehension of the primary learners are on instructional level. Gender of primary learners are significant but not on learners' parent/guardian occupation on all three areas such as oral reading, silent reading, and listening comprehension. On mother tongue spoken, it is significant on oral reading but not significant on two areas such as silent reading and listening comprehension.

VDM publisher

Antar Abdellah

Maulana Iksan

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities

Md. Ruhul Amin

The research paper explores that how the students can develop their reading skills by using effective reading approaches. It is acknowledged that the reading comprehension is one of the most important parts in the English curriculum in all education level of Bangladesh. It is observant that teaching reading approaches are considered as an important procedure to develop the skills of the Bangladeshi students. In Bangladesh most of the teachers do not have the idea of teaching reading approaches. For this reason, the teachers should need to enhance their skills, knowledge and gathering proper idea about effective reading approaches as well as need to prepare themselves to utilize their practical experiences and knowledge on to their students. So the prime purpose of this study to show the effective reading approaches in order to develop student’s reading skills in English. From June to December in 2018, an action research has been applied to a number of 40 students at higher secondary level in Manikganj, Bangladesh. The most important question of the study is ‘could the reading approaches help student’s English reading comprehension studies?’ The outcome of the study specifies that students who have been tutored about the reading strategies have a development to a great level.

United International Journal for Research & Technology (UIJRT)

UIJRT | United International Journal for Research & Technology

The study determined the factors that affect the reading comprehension of Grade 7 students in Magallanes National High School, Magallanes, Sorsogon for school year 2019-2020. A mixed method research approach was used to understand and determine the factors that affect the reading comprehension of Grade 7 students. The participants of the study were the 148 Grade 7 students of Magallanes National High School. In order to determine the reading comprehension level of students in the pre-test and post-test, pre-test and post-test was used. To determine the difference between the results of pre-test and post-test, T-test of paired samples was used. Likewise, to gather relevant information on the factors that may affect the reading comprehension of students an interview schedule was used. Moreover, the data gathered were analyzed using frequency count, mean scores, and Descriptive Phenomenology method. The study showed that there are 14 non-readers, 134 students under frustration level, 136 under instructional level and 6 under independent level in the pre-test. There are 14 non-readers, 14 students under frustration level, 171 under instructional level and 91 students under independent level in the post-test. Likewise, one of the factors that affects the reading comprehension of students is the lack of reading materials was one of the factors affecting the reading comprehension of students, wherein students are provided with limited materials for reading. Another factor is that teachers do not conduct monitoring and home visitation. Students were not monitored or visited especially those who need reading remediation. Moreover, the reading difficulties experienced by students such as understanding the text in English, sometimes difficulty understanding the reading text that is long and words that are longer and having a few knowledge about the reading text are also considered factors. Furthermore, the computed t value on the difference between the results of pre-test and post-test is 5.05. Moreover, to improve the reading comprehension of students, a workbook entitled “ON YOUR MARKS, GET SET, READ: A Workbook for Grade 7 Students” was proposed. In the light of the findings, the present study recommended that teachers may use appropriate learning materials and strategies and may provide reading activities that are relevant for the students to enrich and enhance their reading skills particularly in reading comprehension. Likewise, teachers should conduct monitoring and home visitation to struggling readers and they may collaborate with each other to provide instructional materials (print or non-print) and conduct relevant reading activities for the students. To improve the reading comprehension of students, teachers may employ strategies and may utilize appropriate reading materials. that may improve Another, there is a need to utilize and implement the developed reading material from this study. Moreover, researchers may conduct a study similar to the present study in a wider scope and that they make a study on the reading variables that has not looked into or on the gaps of the study.

RELATED PAPERS

Gaurav Sharma

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Mehrsheed Sinaki

Razon Y Palabra

Gabriela Leveroni

Media Peternakan

Dedy Duryadi Solihin

sairu philip

Can Tho University Journal of Science

Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura

Medicină internă

Patrícia Vasconcelos

Paola Beninato

Foundations of Management

Pawel Sitek

Journal of Logic and Computation

Eunate Mayor

Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry

Johan Vermeulen

Melinda Simon

Prace Literackie

Olga Taranek-Wolańska

Rodrigo Henrique

Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry

Pallavi Bhuyan

olaf m koch

Feminist Economics

Francesca Bettio

ranjan goswami

The American Journal of Human Genetics

Bruno Leheup

Aquaculture International

Marcelo Tesser

Dedee Murrell

Revista Científica Ágora

jhonnel samaniego

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

Implementing Action Research in EFL/ESL Classrooms: a Systematic Review of Literature 2010–2019

- Published: 09 March 2020

- Volume 33 , pages 341–362, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Amira Desouky Ali ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4175-4194 1

1837 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

Action research studies in education often address learners’ needs and empower practitioners to effectively change instructional practices and school communities. A systematic review of action research (AR) studies undertaken in EFL/ESL setting was conducted in this paper to systematically analyze empirical studies on action research published within a ten-year period (between 2010 and 2019). The review also aimed at investigating the focal themes in teaching the language skills at school level and evaluating the overall quality of AR studies concerning purpose, participants, and methodology. Inclusion criteria were established and 40 studies that fit were finally selected for the systematic review. Garrard’s ( 2007 ) Matrix Method was used to structure and synthesize the literature. Results showed a significant diversity in teaching the language skills and implementation of the AR model. Moreover, findings revealed that (50%) of the studies used a mixed-method approach followed by a qualitative method (37.5%); whereas only (12.5%) employed quantitative methodology. Research gaps for future action research in developing language skills were highlighted and recommendations were offered.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Medical Science Educator’s Guide to Selecting a Research Paradigm: Building a Basis for Better Research

Megan E.L. Brown & Angelique N. Dueñas

Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: a systematic evidence map

Melissa Bond, Katja Buntins, … Michael Kerres

Teacher-Student Interactions: Theory, Measurement, and Evidence for Universal Properties That Support Students’ Learning Across Countries and Cultures

Abdallah MS (2016) Towards improving content and instruction of the ‘TESOL/TEFL for special needs’ course: an action research study. Educ Action Res 25(3):420–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1173567

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad S (2012) Pedagogical action research projects to improve the teaching skills of Egyptian EFL student teachers. Proceedings of the ICERI2012, 5th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (PP.3589-3598). Madrid: Spain

Ahn H (2012) Teaching writing skills based on a genre approach to L2 primary school students: an action research. Engl Lang Teach 5(2):2–16

Google Scholar

Ainscow M, Booth T, Dyson A (2004) Understanding and developing inclusive practices in schools: a collaborative action research network. Int J Incl Educ 8(2):125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360311032000158015

Allwright D, Bailey KM (1991) Focus on the language classroom: an introduction to classroom research for language teachers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Alsowat H (2017) A systematic review of research on teaching English language skills for Saudi EFL students. Adv Lang Lit Stud 8(5):30–45

Alvarez CLF (2014) Selective use of the mother tongue to enhance students’ English learning processes…beyond the same assumptions. PROFILE Issues Teach Prof Dev 16(1):137–151. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.38661

Arteaga-Lara HM (2017) Using the process-genre approach to improve fourth-grade EFL learners’ paragraph writing. Lat Am J Content Lang Integr Learn 10(2):217–244. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2017.10.2.3

Bethany-Saltikov J (2012) How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Burns A (2010) Doing action research in English language teaching: a guide for practitioners. Routledge, New York, p 196 ISBN 978-0-415-99145-2

Campbell E, Cuba M (2015) Analyzing the role of visual cues in developing prediction-making skills of third- and ninth-grade English language learners. CATESOL J 27(1):53–93

Campbell YC, Filimon C (2018) Supporting the argumentative writing of students in linguistically diverse classrooms: an action research study. RMLE Online 41(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2017.1402408

Carolina B, Astrid R (2018) Speaking activities to foster students’ oral performance at a public school. Engl Lang Teach 11(8):65–72

Carr W, Kemmis S (1986) Becoming critical: education. knowledge and action research. Falmer, London

Cerón CN (2014) The effect of story read-alouds on children’s foreign language development. Gist Educ Learn Res J 8:83–98

Chaves O, Fernandez A (2016) A didactic proposal for EFL in a public school in Cali. HOW 23(1):10–29. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.1.139

Chen S, Huang F, Zeng W (2018) Comments on systematic methodologies of action research in the new millennium: a review of publications 2000–2014. Action Res 16(4):341–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750317691103

Cho Y, Egan TM (2009) Action learning research: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Hum Resour Dev Rev 8(4):431–462 SAGE Publications

Cochrane TD (2014) Critical success factors for transforming pedagogy with mobile web 2.0. Br J Educ Technol 45(1):65–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01384.x

Cooper K, White RE (2012) Qualitative research in the postmodern era: contexts of qualitative research. Springer, Dordrecht

Dewi R, Kultsum U, Armadi A (2017) Using communicative games in improving students’ speaking skills. Engl Lang Teach 10(1):63–71

El-Deghaidy H (2012) Education for sustainable development: experiences from action research with science teachers. Discourse Commun Sustain Educ 3(1):23–40

Elliott J (1991) Action research for educational change. Open University Press, Milton Keynes

Fahrurrozi (2017) Improving students’ vocabulary mastery by using Total physical response. Engl Lang Teach 10(3):118–127. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n3p118

Fischer JC (2001) Action research, rationale and planning: developing a framework for teacher inquiry. In: Burnaford G, Fischer J, Hobson D (eds) Teachers doing research: The power of action through inquiry, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, pp 29–48

Fullerton S, Clemson A, Robson K (2015) Using a scaffolded multi-component intervention to support the reading and writing development of English learners. i.e. Inq Educ 7(1):1–20 http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1104&context=ie

Gámez DY, Cuellar JA (2019) The use of Plotagon to enhance the English writing skill in secondary school students. Profile Issues Teach Prof Dev 21(1):139–153. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n1.71721

Garrard J (2007) Health sciences literature review made easy: the matrix method. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury

Greenwood DJ, Levin M (1998) Introduction to action research: social research for social change. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Gutiérrez KG, Puello MN, Galvis LA (2015) Using pictures series technique to enhance narrative writing among ninth grade students at Institución Educativa Simón Araujo. Engl Lang Teach 8(5):45–71

Halwani N (2017) Visual aids and multimedia in second language acquisition. Engl Lang Teach 10(6):53–59

Hamilton C (2018) The Effects of peer-revision on student writing performance in a middle school ELA classroom (doctoral dissertation). University of South Carolina. ProQuest: Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4596

Han L (2017) Analysis of the problems in language teachers’ action research. Int Educ Stud 10(11):123–128

Jaime-Osorio MF, Caicedo-Muñoz MC, Trujillo-Bohórquez IC (2019) A radio program: a strategy to develop students’ speaking and citizenship skills. HOW 26(1):8–33. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.26.1.470

Jones-Jackson B (2015) Supplemental Literacy Instruction: Examining its effects on student learning and achievement outcomes: An action research study (doctoral dissertation). Capella University, ProQuest: Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED558987

Juriah J (2015) Implementing controlled composition to improve vocabulary mastery of EFL students. Dinamika Ilmu 15(1):137–162

Kemmis S, McTaggert R (1998) The action research planner. Deakin University Press, Geelong

Kostandy M (2013) Teachers as agents of change: A case study of action research for school improvement in Egypt (unpublished Master’s thesis). American University in Cairo, Graduate School of Education, Cairo, Egypt

Lan Y-J (2015) Action research contextual EFL learning in a 3D virtual environment. Lang Learn Technol 19(2):16–31

Lavalle PI, Briesmaster M (2017) The study of the use of picture descriptions in enhancing communication skills among the 8th-grade students—learners of English as a foreign language. I.e. Inq Educ 9(1):1–16 Article 4

Lee MW (2018) Translation revisited for low-proficiency EFL writers. ELT J 72(4):365–373

Madriñan MS (2014) The use of first language in the second-language classroom: a support for second language acquisition. Gist Educ Learn Res J 9:50–66

Marenco-Domínguez JM (2017) Peer-tutoring fosters spoken fluency in computer-mediated tasks. Lat Am J Content Lang Integr Learn 10(2):271–296. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2017.10.2.5

McNiff J, Whitehead J (2006) All you need to know about action research. SAGE Publications, London

Mertler CA (2014) Action research: improving schools and empowering educators (4th ed). SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Miles GE (2006) Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher, 3rd edn. Merrill Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Montelongo J, Herter RJ, Ansaldo R, Hatter N (2010) A lesson cycle for teaching expository reading and writing. J Adolesc Adult Lit 53(8):656–666. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.53.8.4

Murillo HA (2013) Adapting features from the SIOP component: lesson delivery to English lessons in a Colombian public school. PROFILE 15(1):171–193

Nair S, Sanai M (2018) Effects of utilizing the STAD method (cooperative learning approach) in enhancing students’ descriptive writing skills. International. J Educ Pract 6(4):239–252

Nasrollahi M, Krishnasamy PN, Noor N (2015) Process of implementing critical Reading strategies in an Iranian EFL classroom: an action research. Int Educ Stud 8(1):9–16

Niño F, Páez M (2018) Building writing skills in English in fifth graders: analysis of strategies based on literature and creativity. Engl Lang Teach 11(9):102–117

Nova J, Chavarro C, Córdoba A (2017) Educational videos: a didactic tool for strengthening English vocabulary through the development of affective learning in kids. Gist Educ Learn Res J 14:68–87

Nurhayati DA (2015) Improving students’ English pronunciation ability through go fish game and maze game. Dinamika Ilmu 15(2):215–233

Ortiz SM, Cuéllar MT (2018) Authentic tasks to foster oral production among English as a foreign language learners. HOW 25(1):51–68. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.362

Ortiz-Neira RA (2019) The impact of information gap activities on young EFL learners’ oral fluency. Profile: Issues Teach Prof Dev 21(2):113–125. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n2.73385

Samawiyah Z, Saifuddin M (2016) Phonetic symbols through audiolingual method to improve the students’ listening skill. DINAMIKA ILMU 16(1):35–46

Sánchez RA (2017) Reading comprehension course through a genre-oriented approach at a school in Colombia. HOW 24(2):35–62. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.24.2.331