The Process of Problem Solving

- Editor's Choice

- Experimental Psychology

- Problem Solving

In a 2013 article published in the Journal of Cognitive Psychology , Ngar Yin Louis Lee (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and APS William James Fellow Philip N. Johnson-Laird (Princeton University) examined the ways people develop strategies to solve related problems. In a series of three experiments, the researchers asked participants to solve series of matchstick problems.

In matchstick problems, participants are presented with an array of joined squares. Each square in the array is comprised of separate pieces. Participants are asked to remove a certain number of pieces from the array while still maintaining a specific number of intact squares. Matchstick problems are considered to be fairly sophisticated, as there is generally more than one solution, several different tactics can be used to complete the task, and the types of tactics that are appropriate can change depending on the configuration of the array.

Louis Lee and Johnson-Laird began by examining what influences the tactics people use when they are first confronted with the matchstick problem. They found that initial problem-solving tactics were constrained by perceptual features of the array, with participants solving symmetrical problems and problems with salient solutions faster. Participants frequently used tactics that involved symmetry and salience even when other solutions that did not involve these features existed.

To examine how problem solving develops over time, the researchers had participants solve a series of matchstick problems while verbalizing their problem-solving thought process. The findings from this second experiment showed that people tend to go through two different stages when solving a series of problems.

People begin their problem-solving process in a generative manner during which they explore various tactics — some successful and some not. Then they use their experience to narrow down their choices of tactics, focusing on those that are the most successful. The point at which people begin to rely on this newfound tactical knowledge to create their strategic moves indicates a shift into a more evaluative stage of problem solving.

In the third and last experiment, participants completed a set of matchstick problems that could be solved using similar tactics and then solved several problems that required the use of novel tactics. The researchers found that participants often had trouble leaving their set of successful tactics behind and shifting to new strategies.

From the three studies, the researchers concluded that when people tackle a problem, their initial moves may be constrained by perceptual components of the problem. As they try out different tactics, they hone in and settle on the ones that are most efficient; however, this deduced knowledge can in turn come to constrain players’ generation of moves — something that can make it difficult to switch to new tactics when required.

These findings help expand our understanding of the role of reasoning and deduction in problem solving and of the processes involved in the shift from less to more effective problem-solving strategies.

Reference Louis Lee, N. Y., Johnson-Laird, P. N. (2013). Strategic changes in problem solving. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25 , 165–173. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2012.719021

good work for other researcher

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Careers Up Close: Joel Anderson on Gender and Sexual Prejudices, the Freedoms of Academic Research, and the Importance of Collaboration

Joel Anderson, a senior research fellow at both Australian Catholic University and La Trobe University, researches group processes, with a specific interest on prejudice, stigma, and stereotypes.

Experimental Methods Are Not Neutral Tools

Ana Sofia Morais and Ralph Hertwig explain how experimental psychologists have painted too negative a picture of human rationality, and how their pessimism is rooted in a seemingly mundane detail: methodological choices.

APS Fellows Elected to SEP

In addition, an APS Rising Star receives the society’s Early Investigator Award.

Privacy Overview

Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science pp 6287–6292 Cite as

Problem Solving

- Shameem Fatima 3

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

31 Accesses

Complex problem solving ; Problem solving ability ; Social problem solving

A problem is a condition that needs to be resolved to achieve a desired goal. Problem-solving makes use of higher order cognitive processes that regulate lower order mental processes to achieve the goal. Problem solving ability is a person’s capability to transform the problematic condition to the goal state by using higher cognitive functions.

Introduction

The whole life involves problem solving from small scale to large scale problems, from simple to complex problems, and from personal and psychological to social, environmental, and collective problems. Problem solving in all problems involves three components: givens (facts or stimuli presented), goals (desired ending), and operations (methods or techniques to achieve the desired objective). Commonly, we engage in problem solving to overcome hindrances, to accomplish a goal, or to find a solution to a problem that has no readymade solution...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Besnard, D., & Cacitti, L. (2005). Interface changes causing accidents. An empirical study of negative transfer. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 62 (1), 105–125.

Article Google Scholar

Campbell, J. I. D., & Robert, N. D. (2008). Bidirectional associations in multiplication memory: Conditions of negative and positive transfer. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34 (3), 546–555.

PubMed Google Scholar

Catroppa, C., & Anderson, V. (2006). Planning, problem-solving and organizational abilities in children following traumatic brain injury: Intervention techniques. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 9 (2), 89–97.

Google Scholar

Cattell, R. B. (1971). Abilities: Their structure, growth, and action . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cazalis, F., Feydy, A., Valabrègue, R., Pélégrini-Issac, M., Pierot, L., & Azouvi, P. (2006). An fMRI study of problem-solving after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 20 (10), 1019–1028.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Duncker, K. (1935). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens [The psychology of productive thinking] . Berlin: Julius Springer.

Funke, J. (2001). Dynamic systems as tools for analysing human judgment. Thinking & Reasoning, 7 (1), 69–89.

Gentile, J. R. (2000). Learning, transfer of. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (Vol. 5, pp. 13–16). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Gentner, D. (2000). Analogy. In R. A. Wilson & F. C. Keil (Eds.), The MIT encyclopedia of the cognitive sciences (pp. 17–20). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

German, T. P., & Barrett, H. C. (2005). Functional fixedness in a technologically sparse culture. Psychological Science, 16 (1), 1–5.

Gunzelmann, G., & Anderson, J. R. (2003). Problem solving: Increased planning with practice. Cognitive Systems Research, 4 (1), 57–76.

Lovett, M. C. (2002). Problem solving. In D. Medin (Ed.), Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology: Memory and cognitive processes (pp. 317–362). New York: Wiley.

Newman, S. D., Carpenter, P. A., Varma, S., & Just, M. A. (2003). Frontal and parietal participation in problem solving in the Tower of London: fMRI and computational modeling of planning and high-level perception. Neuropsychologia, 41 , 1668–1682.

Novick, L. R., & Bassok, M. (2005). Problem solving. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 321–349). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rakoczy, H., Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2009). Young children’s selective learning of rule games from reliable and unreliable models. Cognitive Development, 24 , 61–69.

Seguino, S. (2007). Plus ça change? Evidence on global trends in gender norms and stereotypes. Feminist Economics, 13 (2), 1–28.

Sio, U. N., & Ormerod, T. C. (2009). Does incubation enhance problem solving? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135 (1), 94–120.

Sugrue, B. (1995). A theory-based framework for assessing domain-specific problem solving ability. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 14 (3), 29–35.

Unterrainer, J. M., & Owen, A. M. (2006). Planning and problem solving: From neuropsychology to functional neuroimaging. Journal of Physiology, Paris, 99 (4–6), 308–317.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore, Pakistan

Shameem Fatima

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shameem Fatima .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd K Shackelford

Viviana A Weekes-Shackelford

Section Editor information

Oklamoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA

Jaimie Arona Krems

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Fatima, S. (2021). Problem Solving. In: Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_625

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_625

Published : 22 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-19649-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-19650-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

OPINION article

Use of a creative problem solving (cps) approach in a senior thesis course to advance undergraduate publications.

- Department of Psychological Science, Albion College, Albion, MI, United States

We outline a creativity-based course model for supervising and promoting undergraduate research at a small liberal arts college of about 1,600 undergraduate students, with no graduate offerings. This approach could easily be modified and implemented at weekly brownbag or joint laboratory meetings at similar and larger types of schools. At our institution this course is required of all psychology research thesis students (on average 8 per year) and requires the cooperation of the students, their thesis supervisors, and the course instructor. In part because of this course, during the past 20 years, our department faculty have published a total of 47 publications with undergraduates in peer-reviewed outlets such as Personality and Individual Differences, Psychology of Music, Psychology of Women Quarterly , and Sex Roles . Importantly, according to PsycINFO, these undergraduate-generated publications have garnered more than 500 citations, attesting to the impact that undergraduate research can have on the larger field in terms of knowledge generation. In addition to impactful peer-reviewed publications, our undergraduate students have presented 163 posters at national conferences such as the Association for Psychological Science, Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Society for Neuroscience, and Psychonomic Society. Below we outline how our senior thesis course stimulates the creative dissemination of knowledge that is required during the publication process.

Our senior thesis course structure is based on the Creative Problem Solving (CPS) framework, a well-known and validated approach to creativity enhancement in educational settings. This approach emphasizes creative and critical thinking in instruction—both at an individual and a group level ( Baer, 1988 ; Isaksen et al., 1994 ; Treffinger et al., 2006 ). In the CPS framework, creative thinking occurs when a problem or challenge is considered from many different perspectives, which leads to a multitude of possible solutions or answers (this is also known as divergent thinking—see Wieth and Francis, 2018 for a review). In this stage of creative problem solving, many original solutions or answers are desired ( Boynton, 2001 ). The second aspect of the CPS framework is critical thinking (also known as convergent thinking—see Wieth and Francis, 2018 for a review). After generating possible solutions to a problem or challenge, it is essential for the student to converge on a single most useful solution for that particular problem or challenge ( Campbell, 1960 ; Mednick, 1962 ; Lundsteen, 1986 ; Amabile, 1988 ; Mumford, 2003 ; Sternberg, 2010 ). In this article, we outline how using the CPS framework in our senior thesis research course has prepare and enable our students to thrive during the publication process.

Reiterative critical feedback of written and oral production is an essential component of the CPS approach used in our senior thesis course. Written assignments in this course are no different than what advisors usually ask of their thesis students (e.g., complete a draft of the Introduction or Method), but in keeping with the CPS approach, each written component goes through a cycle of creative and critical feedback from several peers during class. As can be seen from the most recent syllabus, available as Supplementary Material , students must bring their writing to class four times across the semester to be reviewed by peers. Collaboration, social support ( John-Steiner, 2000 ), and honest critique ( Nemeth et al., 2001 ) are viewed as key factors in creative breakthroughs. Therefore, each time peer-review occurs, students are asked to provide and receive constructive feedback from at least two peers in the course. The instructor of the course orchestrates the pairings to ensure that students receive a diverse set of feedback. Typically, a student is paired with a classmate using a similar research approach AND with a classmate using a very different research approach. At a liberal arts college, there is often only one faculty member per psychological discipline (e.g., cognitive psychology), so a student may be working with an advisor that is a cognitive psychologist but receiving feedback from a student working with a social psychologist or neuroscientist. Receiving feedback from someone in a different area of psychology often encourages more divergent thinking and helps students understand the greater context of their research. In other words, the first step in the peer-review process is designed to encourage more creative thinking.

The second part of the CPS framework employed during peer-review in the senior thesis course is designed to encourage critical thinking by having students to practice converging on a best solution to a problem or challenge. For example, during the peer-review process, each student must decide which suggestions are appropriate and helpful for their project and which suggestions are counter to the purpose of the project. However, unlike when students receive feedback from their faculty advisor or an outside faculty member, students feel more comfortable critically evaluating the suggestions from their peers. This provides an excellent mechanism for students to practice critical evaluation after being exposed to a wide range of feedback.

Another way we encourage critical thinking in our course is to scaffold students' research by having students make four platform presentations, each with a different focus for a different audience. During the class, students make two 20-min platform presentations to their peers and other faculty. After receiving feedback from peers on the written portion of the Introduction and Method, the student must give a presentation that covers the Introduction and Method sections. After receiving feedback from peers on the written portion of the Results and Discussion, the student must give a presentation that covers the Results and Discussion sections. After presenting for the allotted time, there is approximately 15 min of discussion devoted to each student's project and presentation. The student's research advisor along with other faculty in the department attend these presentations throughout the semester and provide feedback in an intellectually safe environment. The attendance of faculty other than the instructor is of critical importance during these presentations and serves several purposes. In addition to instruction and practice of psychology presentation skills, the discussion after the presentation allows the faculty to model appropriate conflict resolution and problem solving strategies. Research has shown that fostering an environment where honest and thoughtful dissent is accepted and appreciated enhances productivity and fosters creativity ( Nemeth et al., 2004 ). At first students are often surprised and perhaps a bit intimidated when they experience two or more faculty members debating some aspect of their project, but by the end of the semester, students are more comfortable joining in the debate in a meaningful and appropriate way. Modeling critical and thoughtful responses not only leads our students to hone their thinking and presentation skills, it also provides them essential experience for responding to comments during the peer-review publication process.

As a culminating experience, students must also present their work in two other venues: a regional undergraduate psychology conference and a college-wide research symposium. The purpose of these myriad presentations is for students to learn what components of all the work they have done are essential for presentation to different audiences. In other words, students must converge on a best solution depending on the audience to whom they are presenting. In each situation, the student must modify their presentation for the audience. For many of our research students, this is their first foray into professional psychology meetings, so rather than going initially to a national meeting, we require students in the course to present at regional undergraduate psychology research conference held each spring. This meeting provides students with the opportunity to receive additional reviews of their work, this time from psychology faculty and other psychology majors at different schools who may bring perspectives different from those in our department. To develop more critical feedback response skills, students are required to present at a college-wide symposium given to faculty and students outside the psychology department. For the all-college symposium, students learn how to present their research in a very different way than they have done for their theses and presentations to “psychology-oriented” audiences. For instance, although the importance of basic research into personality may be self-evident to psychologists, it is less obvious to faculty and students not trained in our discipline. Thus, students need to, again, think about their work from a wider perspective, this time including a very diverse audience, to find the most effective way of presenting their research. Much like the peer-review process often provides researchers with different and sometimes even conflicting suggestions; these presentations help students see their own work from multiple perspectives and forces them to choose a presentation and feedback response format that best fits the audience.

Our course outlined here prepares students for what is required during publication by exposing our students to diverse feedback from students, psychology faculty, and college-wide faculty. This is similar to the sundry reviews authors often receive after submitting a manuscript. In addition, our creativity focused classroom model also promotes critical thinking, a fundamental component of creativity, as outlined by the CPS framework ( Isaksen et al., 1994 ). By teaching students to evaluate feedback from a variety of individuals and adjust their presentations to various audiences, we are encouraging critical thinking that helps students understand the importance of finding the best way to present their research. Furthermore, these critical thinking skills help students not get overwhelmed by reviews of their manuscript and the, often many, demands reviewers make. Providing this course to all thesis students in our department has enabled us to teach students more about the research and publication process, allowed us to include more students on publications and national presentations that arise from their own research, and support our fellow faculty in their senior thesis advising endeavors by ensuring that their students meet their goals and deadlines. Using the CPS framework in a course, does take a certain amount of effort and collaboration from advisors, students, and other faculty, but we, and our fellow faculty in the department, believe that those efforts are well-spent as our senior thesis students' work often turns into influential publications in their respective fields.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00749/full#supplementary-material

Amabile, T. M. (1988). “A model of creativity and innovation in organizations,” in Research in Organizational Behavior. Vol. 10, eds B. M. Staw and L. L. Cummings (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press), 123–167.

Google Scholar

Baer, J. M. (1988). Long-term effects of creativity training with middle school students. J. Early Adolesc. 8, 183–193. doi: 10.1177/0272431688082006

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Boynton, T. (2001). Applied research using alpha/theta training for enhanced creativity and well-being. J. Neurother. 5, 5–18. doi: 10.1300/J184v05n01_02

Campbell, D. T. (1960). Blind variation and selective retentions in creative thought as in other knowledge processes. Psychol. Rev . 67, 380–400. doi: 10.1037/h0040373

Isaksen, S. G., Dorval, K. B., and Treffinger, D. J. (1994). Creative Approaches to Problem Solving . Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

John-Steiner, V. (2000). Creative Collaboration. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lundsteen, S. W. (1986). Critical Thinking in Problem Solving: A Perspective for the Language Arts Teacher. Retrieved from: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED294184

Mednick, S. A. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychol. Rev. 69, 220–232.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Mumford, M. D. (2003). Where have we been, where are we going? Taking stock in creativity research. Creativity Res. J. 15, 107-120. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2003.9651403

Nemeth, C., Brown, K., and Rogers, J. (2001). Devil's advocate vs. authentic dissent: stimulating quantity and quality. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 31, 707–720. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.58

Nemeth, C. J., Personnaz, M., Personnaz, B., and Goncalo, J. (2004). The liberating role of conflict in group creativity: A cross-national study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 34, 365–374. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.210

Sternberg, R. (2010). “Teaching for creativity,” in Nurturing Creativity in the Classroom , eds R. Beghetto and J. Kaufman (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 394–414.

Treffinger, D. J., Isaksen, S. G., and Dorval, K. B. (2006). Creative Problem Solving: An Introduction (4th ed.). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Wieth, M. B., and Francis, A. P. (2018). Conflicts and consistencies in creativity research and teaching. Teach. Psychol. 45, 363–370l. doi: 10.1177/0098628318796924

Keywords: undergraduate research, mentoring undergraduate students, faculty collaborations, student development, graduate school preparation

Citation: Wieth MB, Francis AP and Christopher AN (2019) Use of a Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Approach in a Senior Thesis Course to Advance Undergraduate Publications. Front. Psychol. 10:749. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00749

Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 18 March 2019; Published: 09 April 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Wieth, Francis and Christopher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mareike B. Wieth, [email protected] Andrea P. Francis, [email protected] Andrew N. Christopher, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

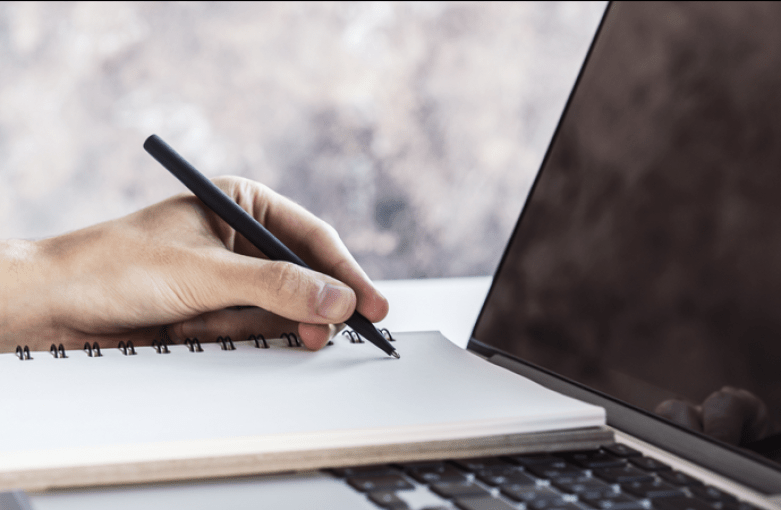

Journaling for Problem Solving: Effective Techniques and Prompts

A problem is often followed by a lot of emotions, thoughts, or information. We need to navigate through this to find the best solution. This can be overwhelming. To work through the problem, you might need to get the problem out of your head and into the open. One way to do this is with a journal for problem-solving.

Table of Contents

Your problems might come in many different shapes. You might be in emotional turmoil or have to make a difficult decision. With an issue as broad as this, there isn’t one kind of journaling effective for all kinds of problems.

Let’s have a look at 4 journaling techniques and 12 prompts for problem-solving.

Types of journals for problem solving

There are several types of journals you can use for solving problems. Let’s have a look at 4 of those.

1. Thought journal

A thought journal is a type of journaling where you let your thoughts flow uninterrupted onto the paper. There is no predefined structure, no prompts, or anything else for you to think about. Your thoughts need to run freely.

You’ll often get new insights and ideas when you let your thoughts run freely. This is great for finding alternative solutions to a problem. Sometimes you won’t get any useful insights with you journal. That’s okay. You gave your brain a chance to vent and calm down, which is just as valuable.

How to use a thought journal

Thought journaling is a simple yet effective type of journaling for problem-solving. Here’s how you can do it in 3 steps:

- Take a moment to reflect on your problem. What is it? How does it make you feel? What are you thinking right now? Take a moment to be present with whatever is going on.

- Start writing using your short reflection as a starting point. Let your thoughts flow uninterrupted onto the paper.

- Continue writing until your head feels clear, you have found a solution, or you don’t want to write anymore.

You might want to go through your journal once you’ve finished to see if there are any insights you’ve missed in the middle of writing.

When to use a thought journal for problem solving

You can use a thought journal as a tool to solve any kind of problem. But it’s most effective when it’s related to high stress or anxiety.

2. Pros and cons

You probably already know the pros and cons list. It’s a classic tool to help you make a decision when you have to choose between a limited number of options.

How to use pros and cons

The pros and cons list is probably the simplest tool on this list. Here’s how you can do it yourself.

- Have a piece of paper and divide it into two columns. Name one column pros and the other cons.

- Fill the pros column with all the good things about this option

- Fill the cons column with all the negatives about this option

Once you’ve filled the columns, it’s time to reflect. How does your situation look now that you’ve weighed your options side by side?

If you have to choose between more than one option, such as which school to pick, you can go through the process with each option.

When to use a pros and cons for problem solving

The pros and cons list works best when you have to make a decision between a limited number of options. This might be choosing a school or a job. The more options you have, the less effective this method is.

3. Fake letter for problem solving

Fake letters are a popular journaling technique where you’ll write a letter to either yourself or someone else. The reason why it’s fake is that it’ll never be sent. Nobody but you will ever see it.

There are several types of fake letters. Here we’ll look into two of them. One for problems and another for difficult emotions

How to use a fake letter for problem solving

Most people find it easier to find a solution to a friend’s problem than to find one on their own. A fake letter for problem-solving takes advantage of this.

With this technique, you’ll pretend that a friend is in the exact same situation as you. They have asked for your advice on how to solve a problem they’re facing (your problem). Write a letter to your friend and give them advice on how to solve it.

Your advice might not be perfect every time, but it’ll help you think no matter what. It’ll help you move closer to a solution.

How to use a fake letter to vent

A fake letter to vent is similar to the one for problem-solving. The main difference is that you’re looking for tension relief instead of a solution here.

With this technique, you’ll write a fake letter to someone else. Someone who has frustrated you lately but that you aren’t able to tell how you feel. Pretend to write a letter to that person. In the letter, you tell them whatever it is you need to do.

Remember, you don’t have to sugarcoat anything. Let all your anger, sadness, fear, or frustration out. Write whatever it is you need to, how you need to.

When to use a fake letter for problem solving

A fake letter for problem solving is effective for any kind problem.

When to use a fake letter to vent

A fake letter to vent should be used when a person, thing, or situation provokes a lot of strong feelings in you.

Related: Find peace with a gratitude journal

4. Prioritization journal

When we have to make a difficult decision, we often have to prioritize between several things. When you know what you want, that’ll be easy.

Most people have an idea about what they want, but once they dig a little deeper, they have no idea.

A prioritization journal can help you dig past the surface and discover what you truly want. And the more you practice this, the better you’ll know yourself. The easier it’ll be to make decisions and prioritize.

Related: Learn how to increase productivity with a journal

How to use a prioritization journal

Before you can use your prioritization journal to solve problems, you have to know what your priorities are.

- Spend some time on self-discovery. Make a list of your values, dreams, and life necessities.

- Give each item on your list a number. Give the most important thing 1, the second 2, and so on. Be sure that you rank them based on how you really feel.

- Update the list frequently to ensure that it’s still relevant.

Once you have a list of priorities, you can use it as a tool every time you face a new decision. Weight how the different decisions affect the long-term effect of your goals and values. The option which benefits your top priorities is usually the best decision.

This method is similar to a goal journal. You can read more about goal journaling here .

Related: How to beat procrastination

When to use a prioritization journal for problem solving

This type of journaling can be used for any kind of problem but are most effective when you have to make a difficult decision. This might be when choosing a school, a job, or something as simple as whether you should go to the gym today.

Journaling prompts for problem solving

Prompts are short statements or questions that can help you get started with a journal and can work on numerous things. One of them is problem-solving. Here are 12 prompts you can use for your problem-solving journal.

- Describe a recent challenge that you’ve overcome. How did you do it?

- Identity a recurring issue in your life. What is it and how can you overcome it?

- Take a complex issue you’re facing and break it into as many smaller parts as possible. Which part of the problem can you solve right now?

- Think back to a situation where you had to make a tough decision. What did you chose and how did it play out?

- Think back to a time where you faced failure or setback. How did you bounce back?

- Think back to a moment where things didn’t go as planned. How did turn out?

- What is the worst thing that can happen? How likely is it that this will happen?

- Think back to a time where you successfully collaborated with someone else. How did it turn out?

- Right now, what feels best to me?

- If I make this choice, how do I think it’ll affect my future?

- Have a faced a similar problem in the past. Did I learn anything from it?

- What would I do in this situation if I didn’t care about what other people think?

Finishing thoughts

Journaling is a great tool for problem-solving. It can give you an overview of the situation, calm your thoughts and emotions, and help you make a decision that aligns best with your values.

Hopefully, you’ll find that journaling can make dealing with your problems a bit easier.

What to read about next:

The Power of Small Wins: Achieving Success One Step at a Time

Thought journal: Journaling for stress and anxiety

Productivity Journaling: Unlocking Efficiency and Success

Gratitude Journal: A Beginner’s Guide to Cultivate Gratitude

Reach Your Goals with a Goal Journal: Turn Dreams into Reality

- Recent Posts

- Personal Productivity: What It Is and How to Improve It - March 7, 2024

- Multitasking: Breaking Free from the Counterproductive Habit - January 21, 2024

- The 20-Second rule: A simple Technique for Better Habits - August 30, 2023

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Search Menu

- Animal Research

- Cardiovascular/Pulmonary

- Health Services

- Health Policy

- Health Promotion

- History of Physical Therapy

- Implementation Science

- Integumentary

- Musculoskeletal

- Orthopedics

- Pain Management

- Pelvic Health

- Pharmacology

- Population Health

- Professional Issues

- Psychosocial

- Advance Articles

- COVID-19 Collection

- Featured Collections

- Special Issues

- PTJ Peer Review Academies

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Why Publish With PTJ?

- Open Access

- Call for Papers

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Promote your Article

- About Physical Therapy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Permissions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Materials and methods, discussion and conclusion.

- < Previous

Use of the ICF Model as a Clinical Problem-Solving Tool in Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Medicine

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Werner A Steiner, Liliane Ryser, Erika Huber, Daniel Uebelhart, André Aeschlimann, Gerold Stucki, Use of the ICF Model as a Clinical Problem-Solving Tool in Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Medicine, Physical Therapy , Volume 82, Issue 11, 1 November 2002, Pages 1098–1107, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/82.11.1098

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The authors developed an instrument called the “Rehabilitation Problem-Solving Form” (RPS-Form), which allows health care professionals analyze patient problems, to focus on specific targets, and to relate the salient disabilities to relevant and modifiable variables. In particular, the RPS-Form was designed to address the patients' perspectives and enhance their participation in the decision-making process. Because the RPS-Form is based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Model of Functioning and Disability, it could provide a common language for the description of human functioning and therefore facilitates multidisciplinary responsibility and coordination of interventions. The use of the RPS-Form in clinical practice is demonstrated by presenting an application case of a patient with a chronic pain syndrome.

The most effective health care interventions for complex medical conditions, such as those encountered in people with chronic diseases, are thought by many authors to probably be delivered by multidisciplinary care teams. 1 This team model originates from the belief that a comprehensive therapeutic approach is required to fully address the current health care needs of patients with complex or chronic diseases. 2 , 3 Such integrated care, in our view, requires an exchange of information among all people involved in the therapeutic process. Multidisciplinary health care thus necessitates tools that function across professional boundaries 4 and that can handle differences in perspectives (eg, those shown to exist between physicians and nurses). 4 , 5 Health care professionals, as well as their patients, may perceive specific needs and disorders and their overall management quite differently. 4 , 6 – 8 Dissimilar points of view regarding a patient's health care needs and goals can lead to inappropriate treatment strategies, can hamper communication, 9 and can decrease the patient's adherence. 10 In order to avoid critical differences between the patient's and the health care professional's treatment goals, the goals need to be clarified prior to planning interventions. 11

Another important aspect is that the consequences of disease manifest differently in different people. Although many patients may have the same disease, their responses to disease can be unique, and these particulars can become crucial in the care of patients. 12 Patient-centered practice is thought by some authors 13 to improve health status and increase the efficiency of care.

To summarize our thoughts, a patient-centered evaluation tool is needed in order to acknowledge the views, experience, and perspectives of all participants involved in the health care process. Ideally, such a tool should fulfill the clinical needs of both the patient and the health care team, should be simple to use, and should have a background that can be accepted by all involved partners.

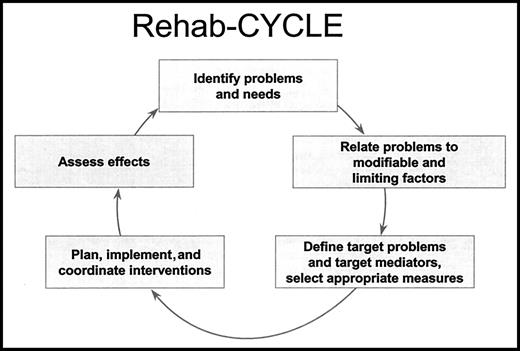

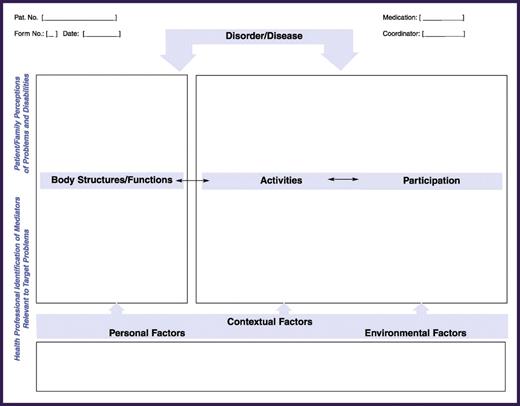

Based on the framework of the Rehabilitation Cycle (and its modified version, the Rehab-CYCLE) developed by Stucki and Sangha 14 ( Fig. 1 ), we developed a further extension that we called the “rehabilitation problem-solving form” (RPS-Form) ( Fig. 2 ). This form is used to identify specific and relevant target problems, discern factors that cause or contribute to these problems, and plan the most appropriate interventions. In addition, the RPS-Form was designed to be used as a tool to facilitate both intraprofessional and interprofessional communications and to improve the communication between health care professionals and their patients.

The Rehab-CYCLE is a modified version of the Rehabilitation Cycle developed by Stucki and Sangha. 14 It guides the health care professional with a logical sequence of activities. Endpoints of this rehabilitation management system are successful problem solving or individual goals achieved. The Rehab-CYCLE involves identifying the patient's problems and needs, relating the problems to relevant factors of the person and the environment, defining therapy goals, planning and implementing the interventions, and assessing the effects.

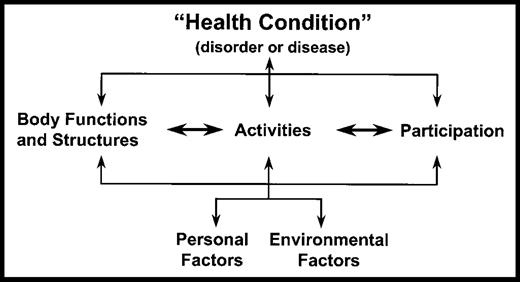

The Rehabilitation Problem-Solving Form (RPS-Form) is based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Model of Functioning and Disability 15 (see Fig. 3 ). The main difference is that the RPS-Form is divided into 3 parts: (1) header for basic information, (2) upper part to describe the patient's perspective, and (3) lower part for the analysis of the health care professionals. Copyright 2000 by Dr Werner Steiner, Switzerland. Reprint allowed with permission only.

The aims of our article are to present the theoretical construct that underlies the recently developed RPS-Form and to advocate its use in rehabilitation. The Rehab-CYCLE is used as a framework to present this clinical problem-solving tool because the rehabilitation team followed the different steps of this approach and because we believe the RPS-Form and the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Model of Functioning and Disability 15 that underlies this approach ( Fig. 3 ) are integrated in the Rehab-CYCLE.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Model of Functioning and Disability 15 visualizes the interactions among the various components in the “process” of functioning and disability. The ICF provides a description of situations with regard to human functioning and disability and serves as a framework to organize information. Functioning and disability (“body functions and structures,” “activities,” and “participation”) are seen as an interaction between the “health condition” (“disorder/disease”) and the contextual factors (“personal factors” and “environmental factors”). This figure has been modified and reprinted with permission of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization.

The Rehab-CYCLE

Rehabilitation, in our view, is a continuous process that involves identifying the problems and needs of individuals, relating the problems to relevant factors of the person and the environment, defining therapy goals, planning and implementing the interventions, and assessing the effects of interventions using measurements of relevant variables. To guide health care professionals in successful rehabilitation management, Stucki and Sangha 14 developed the Rehab-CYCLE. The ultimate goal of the Rehab-CYCLE is to improve a patient's health status and quality of life by minimizing the consequences of disease.

The Rehab-CYCLE ( Fig. 1 ) is a structured approach to rehabilitation management that includes all tasks from problem analysis to the assessment of the effects, thereby involving the patient in clinical decision making. The emphasis is on the patient's perspective (eg, through patient-rated questionnaires), taking into account the patient's needs and preferences, and discussing therapy goals by means of the RPS-Form, which will be presented in this article.

Because the consequences of disease manifest differently in different people, it is necessary to have a conceptual framework for ordering and understanding what disease means to a patient. At the Institute of Physical Medicine of the University Hospital Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland), the WHO's ICF Model of Functioning and Disability 15 was recently implemented for this purpose by using the RPS-Form.

The RPS-Form consists of a single data sheet that is based on the ICF. The ICF classifies health and health-related components (such as education and labor) that describe body functions and structures, activities, and participation.

The overall aim of the developers of the ICF was to provide a unified and standard language and framework for the description of all aspects of human health and some health-relevant aspects of well-being. 15 The ICF provides a structure to present this information in a meaningful, interrelated, and easily accessible way. The information is organized in 2 parts, with each part having 2 components. Part 1 of the ICF (functioning and disability) consists of (1) body functions and structures and (2) activities and participation, and part 2 of the ICF (contextual factors) consists of (1) environmental factors and (2) personal factors.

Each ICF component can be expressed in both positive and negative terms. At one end of this scale are the terms that indicate nonproblematic (ie, neutral and positive) aspects of health and health-related states, and at the other end are the terms can be used to indicate problems. Nonproblematic aspects of health are summarized under the umbrella term “functioning,” whereas “disability” serves as an umbrella term for impairment, activity limitation, or participation restriction.

An ICF component consists of various domains and, within each domain, categories, which are the units of the ICF classification. All ICF categories are “nested” so that broader categories are defined to include more detailed subcategories of the parent category.

Health-related states of an individual are then recorded by selecting the appropriate category code or codes and then adding qualifiers, which are numeric codes, and specifying the extent or the magnitude of the functioning or disability in that category or the extent to which an environmental factor is a facilitator or barrier (for details, see the recently released full version of the ICF 15 ).

The ICF also provides a model of functioning and disability, which reflects interactions between the components of the ICF ( Fig. 3 ). The ICF Model of Functioning and Disability 15 is a biopsychosocial model designed to provide a coherent view of various dimensions of health at biological, individual, and social levels.

As illustrated in Figure 3 , an individual's functioning or disability in a specific domain represents an interaction between the “health condition” (eg, diseases, disorders, injuries, traumas) and the contextual factors (ie, “environmental factors” and “personal factors”). The interactions of the components in the model are in 2 directions, and interventions in one component can potentially modify one or more of the other components.

The RPS-Form

The RPS-Form ( Fig. 2 ) is constructed similarly to the ICF Model of Functioning and Disability ( Fig. 3 ). Each component of the ICF model is graphically highlighted by a gray background. For instance, “disorder/disease” (or “health condition”) is highlighted at the top of the model; the main components of functioning or disabilities are highlighted in the middle of the model, with (left to right) body level (“body structures/functions”), individual level (“activities”), and societal level (“participation”); and the contextual factors (“personal factors” and “environmental factors”) are highlighted at the bottom of the model. As indicated in Figure 2 by the gray arrows pointing downward and upward, “disorder/disease” as well as “environmental factors” and “personal factors” may have an impact on all components of functioning and disabilities.

The RPS-Form is designed to distinguish between the perspectives held by the patient and those of the health care professional. The patient's view is recorded in the upper part of the form denoted with “patient (or relatives): problems and disabilities,” and the health care professional's views are noted in the lower part denoted with “health professionals: mediators relevant to target problems.” The header of the RPS-Form is reserved for basic information: identification of the patient (“pat. no.”), form identification number (“form no.”), date (“date”), disorder/disease (eg, in words), current medication (“medication”) and case coordinator (“coordinator”).

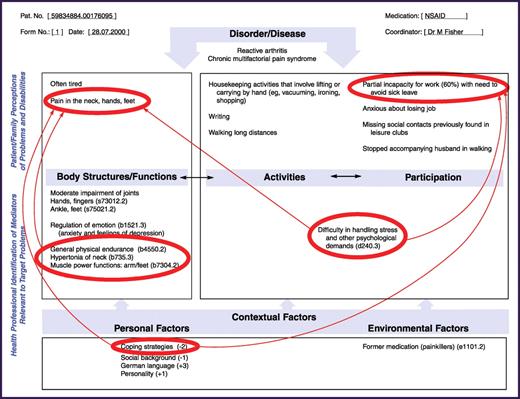

RPS-Form: Case of a Woman With Chronic Pain

A 49-year-old woman of Asian origin who had been living in Switzerland for over 20 years, was married, had no children, and had worked for 10 years as a nurse was referred as an inpatient to the Department of Rheumatology and Institute of Physical Medicine at the University Hospital Zurich for treatment for generalized painful reactive arthritis. This referral followed an episode of gastrointestinal infectious disease 2 years previously, with a positive stool identification of Yersinia enterocolitica as the pathogenic agent. Upon entry, the patient had a chronic pain syndrome that mostly affected her cervical (C5-C6 degenerative modifications) and thoracic spine. The patient also had pain at multiple locations such as in the elbows, hands, knees, and feet. No additional involvement of the axial skeleton could be found. One year prior to referral as an inpatient she started receiving weekly injections of methotrexate (increasing the dose from 10 to 25 mg at time of referral), with hydroxychloroquine (2 × 200 mg/d) added after 7 months and sulfasalazine (4 × 500 mg/d) added after 10 months. This mixed drug therapy did not alleviate the patient's symptoms.

At various times in the past, the patient received at the University Hospital Zurich corticosteroid injections in both feet and elbow (Kenacort * 20 mg/injection), which together with numerous sessions of physical therapy helped to reduce the symptoms. The patient's chronic secondary depression was treated with antidepressive agents (Surmontil † 10 mg/d), which did not entirely alleviate this condition. As a consequence of this chronic pain syndrome, the patient reduced her professional activity as a nurse to 60% 3 years before she was referred as an inpatient, and she stopped all professional activity 2 years later.

The clinical laboratory investigations made at the beginning of her hospitalization were normal, with no indication of any inflammatory or infectious activity, muscle degradation, or any other metabolic or biological abnormality. The diagnosis at the time of discharge from the hospital was chronic multifactorial pain syndrome with cervical and thoracic spondylarthritis and status after reactive arthritis associated with secondary depression. The patient continued her basic medication, including her antirheumatic drugs (weekly methotrexate injections of 20 mg, hydroxychloroquine 2 × 200 mg/d). The patient was discharged from the bed unit after 2 weeks and then was admitted to the Interdisciplinary Outpatient Pain Program (IOPP), which is hosted at the Department of Rheumatology and Institute of Physical Medicine of the University Hospital Zurich.

Identification of problems and disabilities and reporting them on the RPS-Form

According to Stucki and Sangha, 14 the identification of a patient's problems and needs is the first step in rehabilitation management. In the case of our patient, a series of interviews were initially conducted with the rehabilitation team (physician, psychologist, physical therapist, and social worker). In addition, questionnaires were used to comprehensively assess her experience with chronic pain. These questionnaires were the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), 16 a generic health status measure; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), 17 which we used as a screening instrument for depressive and anxiety disorders; and the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ), 18 which we used to analyze the patient's pain coping strategies.

The concerns of the patient, as compiled by the various members of the health care team and supported by the analysis of the initial SF-36, HADS, and CSQ results, were then reported by the case coordinator on the upper part of the RPS-Form ( Fig. 4 ). In order to avoid interpretation that goes beyond the patient's statements, we argue that it is essential to describe these concerns in the patient's own words and to discuss these entries with the patient.

The Rehabilitation Problem-Solving Form (RPS-Form) applied to a patient with chronic pain. The form visualizes the current understanding of the patient's state of functioning and disability, her target problems, and how the health care professional team relates them to hypothetical mediators and contextual factors. NSAID=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Copyright 2000 by Dr Werner Steiner, Switzerland. Reprint allowed with permission only.

As shown in Figure 4 , the patient reported neck pain, as well as pain in the hands and feet. She often felt tired, which she said prevented her from participating in leisure clubs as she had done 2 years before. Writing or housekeeping activities that involved lifting and carrying objects with the hands (eg, using a vacuum cleaner) were very difficult tasks for her. Walking long distances became almost impossible due to the pain in her feet, and she could no longer join her husband on his walks. Above all, she was anxious about losing her job as a nurse as a consequence of the further degeneration of her health and that this would lead to financial dependency on her husband.

Relate problems to relevant and modifiable factors

So far, the problem analysis that occurred was a compilation of the patient's problems and needs. Each specialist then examined the patient, keeping in mind concerns stated by the patient on the RPS-Form.

Through this process, the rehabilitation team tried to relate these problems to impairments, activity limitations, participation restrictions, or personal and environmental factors. All team members were requested to generate hypotheses about cause and effects. That is, the rehabilitation team attempted to identify those characteristics of the patient or her environment that caused or contributed to her problems, either directly or indirectly by transmission. The multiple interactions between patient and environment, and between all components of the patient's organism, require thinking in terms of causal networks, rather than in straight lines where A causes B, which leads to C. 12

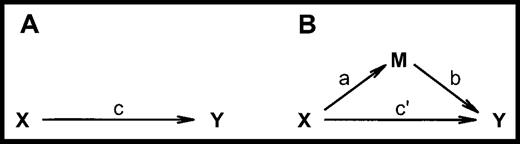

Because it is often unclear whether a variable is directly responsible for a disability or whether it is a trigger that releases certain processes linked with the disability, the umbrella term “mediator” is used on the RPS-Form to describe such variables. The concept of mediation 19 is explained in Figure 5 .

The concept of mediation as explained by Baron and Kenny. 19 (A) Variable X is assumed to affect another variable (variable Y). Variable X is called the initial (or independent) variable, and the variable that it affects (variable Y) is called the outcome variable. The direct impact of the independent variable is indicated by path c. (B) The effect of variable X on variable Y is mediated by a process or mediating variable (variable M), with path b indicating the impact of the mediator. The variable X may still affect variable Y (path c′). The mediator also has been called an intervening or process variable. Complete mediation can occur when variable X no longer affects variable Y (path c′ = zero) after variable M has been controlled.

Mediators, as identified by the various members of the rehabilitation team, are reported by the case coordinator on the lower part of the RPS-Form ( Fig. 4 ). At this stage, the RPS-Form is completed to be discussed at the next interdisciplinary treatment team meeting.

Which terms should be used to denote mediators?

In order to ensure a common language for interdisciplinary teams, we recommend that health care professionals specify the mediators on the RPS-Form, listing corresponding terms that are listed in the ICF 15 ( Fig. 4 ). Only the well-defined ICF items, we believe, can ensure consistency in the use of terminology across disciplines, and inconsistency can pose a barrier to effective communication. 20

The ICF terms can be interpreted by means of 3 separate but related constructs, 15 all using “qualifiers” for operationalization. Body functions and body structures can be described by a qualifier, with the negative scale used to indicate the extent or magnitude of an impairment (eg, the qualifier “s73021.2” can be used to indicate moderate impairment of the joints of the hands and fingers). For the activities and participation component, 2 constructs are available: capacity and performance. 15 The capacity qualifier describes an individual's ability to execute a task or an action, and the performance qualifier describes what an individual does in his or her current environment. Both qualifiers can be used with and without personal assistance or assistive devices. For simplicity, these 2 constructs are not differentiated further in this article. Therefore, the activities and participation classification results in a single list of items, denoted by a leading “d.” The item code “d240.3” ( Fig. 4 ), for example, refers to the ICF item d240 (“difficulty in handling stress and other psychological demands”), without differentiating between activities and participation. The qualifier “3” denotes a severe difficulty in accomplishing this task, disregarding aspects of capacity and performance.

Qualifiers also can be added to environmental factors. A decimal point denotes a barrier (.1 to .4), whereas a plus sign denotes a facilitator (+1 to +4). 15 For our patient ( Fig. 4 ), the former medication (ie, chronic abuse of pain killers [e1101.2]), was considered a moderate barrier for her rehabilitation.

Although personal factors or resources are extremely importance in the rehabilitation process, 21 they are not classified in the ICF because of the large social and cultural variance associated with them. 15 In our opinion, however, this should not hinder the rehabilitation team in addressing personal factors relevant to the target problems or in describing their quantitative property in analogy to the qualifier system applied to environmental factors ( Fig. 4 ). In our case, personal factors considered relevant to problem solving were: command of the German language (+3 denotes a severe facilitator), personality (+1), social background (−1), and coping strategies (−2).

Define target problems and target mediators on the RPS-Form

After clinical examination of the patient and compilation of all limiting and modifiable mediators on the RPS-Form, a revision process is needed to exchange information within the rehabilitation team as well as with the patient in order to define realistic therapy goals and to plan the most appropriate interventions. The clinical examination may have revealed underlying conditions that force the health care professional to set therapy goals that differ from the personal preferences and beliefs of the patient. When using the Rehab-CYCLE to revise the problems mentioned by the patient ( Fig. 4 , upper part), there is a desire to meet the patient's expectations and to achieve his or her commitment, but always taking into account practical and evidence-based knowledge of the rehabilitation team (eg, aspects of secondary and tertiary prevention). Thus, this process of defining the target problems is usually the result of consent between the patient and the health care team. The target problems are visualized on the RPS-Form by circling the corresponding items. In the case of our patient, they include the alleviation of pain in the neck, hands, and feet and the avoidance of sick leave ( Fig. 4 ).

The importance of the mediators compiled by the health care professional on the RPS-Form might vary from low to high, as does their potential to be modified during the intervention period. It is the “art of rehabilitation” to discern the target mediators (ie, those mediators supposed to have the greatest potential to solve the target problems). This process generally takes place at the interdisciplinary team meeting, where the RPS-Form serves as a basis for team members to discuss findings and hypotheses in the framework of the ICF Model of Functioning and Disability. According to the target problems, the resulting target mediators are marked on the RPS-Form by circling the corresponding items ( Fig. 4 ). Lines can be then drawn to each of the corresponding target problems (dark connecting lines in Fig. 4 ).

The case model

Once these hypothetical relationships are stated by the health care team, the RPS-Form represents an explicit and interdisciplinary elaborated “case model,” explaining by which mediators the target problems can be solved. Because this case model is based on assumptions, the rehabilitation team must carefully explore associations or causal links between mediators and target problems during the intervention period. Individual therapy goals can now be formulated, usually including both target problems and target mediators, and the RPS-Form serves as an excellent tool for communicating these goals to the patient.

The model of our case ( Fig. 4 ) shows that the target problem “pain in neck, hands, feet” is mediated by 3 pathways: (1) by mechanisms related to the body functions (ie, “general physical endurance,” “hypertonia of neck,” and “muscle power functions: arms/feet”), (2) by an indirect mechanism (ie, “difficulty in handling stress and other psychological demands,” and (3) by poor coping strategies. Similarly, the target problem “partial incapacity for work (60%) → avoid sick leave” was related to the same mediators except coping strategies.

Mediators considered by the health care professional to have a low potential to solve the patient's problems during the treatment process are not directly included in this initial case model ( Fig. 4 ). However, their importance might change with progress of the rehabilitation process.

Plan, implement, and coordinate interventions

The concept of the IOPP emphasizes the active participation of the patient and a multidisciplinary team approach to treatment. According to the target mediators specified on the RPS-Form, the initial program for our patient included physical therapy to decrease the muscle contractures of the neck, to improve her general physical endurance, and to increase the muscle force in her arms and feet. The psychological therapy focused on learning daily living strategies to manage pain (ie, coping strategies), to better handle stress (eg, at work), and to deal with other demands (eg, her husband wanted her to accompany him on long walks). Medical therapy included the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to manage her joint problems.

Assess effects of interventions

A rehabilitation management program for complex medical conditions, we believe, needs a routine check of goal attainment by comparing outcomes with target problems ( Fig. 1 , “assess effects”). Use of qualifiers, as shown in Figure 4 , allows the rehabilitation team to quantitatively monitor results in longitudinal care. However, information about the sensitivity and reliability of this new qualifier measurement system is still absent. A better solution to measure longitudinal changes of outcomes would be to use validated instruments such as psychometrically sound questionnaires and standardized clinical parameters. 22 In the case of our patient, outcomes have been measured by a battery of instruments. The corresponding assessment information was presented in the interdisciplinary team meeting. The presentation of these results would go beyond the aims of this article and is disregarded here.

According to the patient's progress in the rehabilitation process, it might be necessary to adjust treatment. After the assessment of effects ( Fig. 1 ), or when a full round of the Rehab-CYCLE is completed, the rehabilitation team compares changes of target problems and target mediators with therapy goals. The degree of problem solving, among other topics, is then a key factor for the rehabilitation team to decide whether a new “problem-solving cycle” should be completed.

The Rehab-CYCLE is therefore an evolutionary and interactive approach that implies continuous survey and a dynamic handling of all elements of the problem-solving process. Each RPS-Form represents a snapshot model of a patient's functioning and disabilities. We therefore advocate that, for every patient with complex health problems, several consecutive RPS-Forms should be used in longitudinal care, these forms should be collected as comprehensive documentation of the treatment process, and this process should be related to observed outcomes. Thereby, sound instruments such as internationally validated, patient-rated questionnaires can help the health care professional to measure whether therapy goals are achieved.

The RPS-Form described in this article has been applied to many different health conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease, neurologic problems such as hemiplegia, musculoskeletal problems such as arthritis and low back pain) at the Institute of Physical Medicine of the University Hospital Zurich. This tool, we believe, is simple to use, helps to fully address the patients' perspectives, and serves as a platform where multidisciplinary care teams can exchange information using a common language. The RPS-Form supports care teams in offering a visual representation of the salient aspects of a disease, as well as of the relationships between disabilities and underlying factors. Therefore, this tool also forms a basis for treatment team meetings to discuss the individual goals of the interventions. The underlying ICF Model of Functioning and Disability provides both the common language and the rational framework for the description of health states associated with diseases and disorders.

The ICF (and the preceding ICIDH-2: International Classification of Disability and Health 23 ) is the result of an effort that started in 1993 and that focused on cross-cultural and multisectoral issues and involved the active participation of 1,800 experts from 65 countries. 15 Studies have been undertaken in an effort to ensure that the ICF is applicable across cultures, age groups, and genders, and it can be used to collect reliable and comparable data on health outcomes of individuals and populations. The ICF was accepted in November 2001 by 191 countries as the international standard to describe and measure health and disability. At present, the ICF is available in 6 languages (English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and Russian); translations into other languages (eg, German) will follow in 2002. Because the ICF contains the collective views of an international group of experts, 23 we believe the RPS-Form permits international communication about clinical problem solving at any level of health.

There are other major conceptual models that can guide health care professionals in understanding disabilities and functioning. Earlier conceptual models used in the same context were reviewed by Jette. 24 One of the first models was developed by the sociologist Nagi. 25 Nagi's classification scheme varies from that of the WHO 23 , 26 primarily by suggesting the concept of functional limitations, that is, the physical manifestation of functional problems at the level of the organism as a whole. According to Nagi, 25 a functional limitation represents a direct way through which impairments contribute to disability. This conceptualization often is considered useful for differentiating between performance-based measures of function and self-reports, an important aspect that was not explicitly integrated in the WHO's International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (ICIDH). 26 However, this aspect is handled by the ICF with the introduction of the concept of capacity and performance.

In the history of rehabilitation management at the Institute of Physical Medicine of the University Hospital Zurich, the first model used in physical therapy was the model of Pope and Tarlov, 27 which is an extension of Nagi's basic disablement formulation. 24 With progress in the initial version of the ICIDH, 26 a revised version, the ICIDH-2, 28 was introduced as a tool for thinking about and describing health and health-related states such as functioning and disabilities. The ICIDH-2 differs substantially from the 1980 version of ICIDH in the depiction of the interrelationships between functioning and disability. The ICIDH-2 was found to be useful in rehabilitation, because the underlying model allows health care professionals to state the complex relationships between “health condition” (eg, diseases, disorders), the components of health (body structures and functions, activities, and participation), and the contextual (ie, environmental and personal) factors. Along with the growing international acceptance of the ICF, the ICF Model of Functioning and Disability and the corresponding classification scheme are considered the future tools for organizing information about functioning and disabilities.

Each model mentioned can be used to generate hypotheses about the interrelationships of different components included in the model. The key to successful rehabilitation management, however, is understanding the relationship between target problems and the components (impairments, functional limitations, and psychosocial and environmental factors) that affect them and addressing those (ie, the target mediators) with the most potential for improvement. In this process, the Rehab-CYCLE is open to all ideologies of hypothesis generating, clinical reasoning, and decision making.

The Rehab-CYCLE ( Fig. 1 ) is a structured approach to rehabilitation management that should help to systematically review disease consequences, to define therapy goals, to relate problems to mediators, and to optimize treatment by relating interventions to results during the rehabilitation process. It is thus similar to the hypothesis-oriented algorithm for clinicians (HOAC) described by Rothstein and Echternach 29 in that it guides the health care professional with a logical sequence of activities and relies on the patient to describe his or her problems and on the health care professional to generate testable hypotheses. Both approaches are open to any treatment strategy. The main difference, we believe, is that the Rehab-CYCLE is a more patient-centered approach with a biopsychosocial perspective.

In the case management at the Institute of Physical Medicine of the University Hospital Zurich, applying the new and unfamiliar systematic coding scheme of ICF classification initially hampered teamwork and communication among the health care team. It is not the correct coding of ICF items, but the problem-solving technique that can lead to better care for the patient. Therefore, when introducing the RPS-Form, health care professionals should feel free in how to describe health and disability (eg, permit initial flexibility in wording, neglect alphanumeric ICF codes and “qualifiers”). Even this simple version of the RPS-Form trains health care professionals in proceeding through the Rehab-CYCLE, permits both health care professionals and patients to focus on salient aspects of the disease, and assists with treatment decision making shared by both the patients and the health care professionals. Because understanding and motivation of the patient is usually a requirement for his active involvement in the rehabilitation process, the simple version of the RPS-Form could even be advantageous in the communication with certain patients.

After establishing the procedures associated with the RPS-Form, we believe the time may have come to introduce the standardized terms of the ICF classification. 23 Use of these terms then can ensure consistency in terminology across disciplines, improve interprofessional communication, and facilitate multidisciplinary responsibility and coordination of interventions in physical therapy and rehabilitative medicine.

Dr Steiner, Ms Ryser, Ms Huber, Mr Aeschlimann, and Mr Stucki provided concept/idea/design. Dr Steiner and Ms Huber provided writing. Ms Ryser provided data collection. Dr Steiner, Ms Ryser, and Mr Uebelhart provided data analysis. Dr Steiner and Mr Aeschlimann provided project management. Mr Aeschlimann provided fund procurement and clerical support. Ms Huber, Mr Uebelhart, and Mr Aeschlimann provided institutional liaisons. Mr Uebelhart and Mr Aeschlimann provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission). The authors thank Leanne Pobjoy for her help in preparing the manuscript and Professor Beat A Michel, Director of the Department of Rheumatology and Institute of Physical Medicine, for his continuous support

The Rehab-CYCLE project has been supported, in part, by an unrestricted educational grant from the Zurzach Rehabilitation Foundation.

Bristol-Myers Squibb, La Grande Arche Nord, 92044 Paris, France.

Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, Div of American Home Products Corp, PO Box 8299, Philadelphia, PA 19101.

Wagner EH . The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management . BMJ . 2000 ; 320 : 569 – 572 .

Google Scholar

Minsky BD . Multidisciplinary case teams: an approach to the future management of advanced colorectal cancer . Br J Cancer . 1998 ; 77 ( suppl 2 ): 1 – 4 .

Kole Snijders AM , Vlaeyen JW , Goossens ME , et al. . Chronic low-back pain: what does cognitive coping skills training add to operant behavioral treatment ? Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol . 1999 ; 67 : 931 – 944 .

Jacobson DH , Winograd CH . Psychoactive medications in the long-term care setting: differing perspectives among physicians, nursing staff, and patients . J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol . 1994 ; 7 : 176 – 183 .

Adamek ME , Kaplan MS . Caring for depressed and suicidal older patients: a survey of physicians and nurse practitioners . Int J Psychiatry Med . 2000 ; 30 : 111 – 125 .

Donovan JL , Blake DR . Qualitative study of interpretation of reassurance among patients attending rheumatology clinics: “just a touch of arthritis, doctor ?”. BMJ . 2000 ; 320 : 541 – 544 .

Potts M , Weinberger M , Brandt KD . Views of patients and providers regarding the importance of various aspects of an arthritis treatment program . J Rheumatol . 1984 ; 11 : 71 – 75 .

Silvers IJ , Hovell MF , Weisman MH , Mueller MR . Assessing physician/patient perceptions in rheumatoid arthritis: a vital component in patient education . Arthritis Rheum . 1985 ; 28 : 300 – 307 .

Neville C , Fortin PR , Fitzcharles M , et al. . The needs of patients with arthritis: the patient's perspective . Arthritis Care and Research . 1999 ; 12 : 85 – 95 .

Gopinath B , Radhakrishnan K , Sarma PS , et al. . A questionnaire survey about doctor-patient communication, compliance, and locus of control among south Indian people with epilepsy . Epilepsy Res . 2000 ; 39 : 73 – 82 .

Suarez Almazor ME , Conner Spady B , Kendall CJ , et al. . Lack of congruence in the ratings of patients' health status by patients and their physicians . Med Decis Making . 2001 ; 21 : 113 – 121 .

McWhinney IR . Being a general practitioner: what it means . European Journal of Family Practice . 2001 ; 6 : 135 – 139 .

Stewart M , Brown JB , Donner A , McWhinney IR , et al. . The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes . J Fam Pract . 2000 ; 49 : 796 – 804 .

Stucki G , Sangha O . Principles of rehabilitation . In: Klippel JH , Dieppe PA , eds. Rheumatology . 2nd ed. London, England : Mosby ; 1998 : 11.1 – 11 .14.

Google Preview

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). ICF full version . Geneva, Switzerland : World Health Organization ; 2001 .

Ware JE Jr , Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection . Med Care . 1992 ; 30 : 473 – 483 .

Zigmond AS , Snaith RP . The hospital anxiety and depression scale . Acta Psychiatr Scand . 1983 ; 67 : 361 – 370 .

Rosenstiel AK , Keefe FJ . The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment . Pain . 1983 ; 17 : 33 – 44 .

Baron RM , Kenny DA . The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations . J Pers Soc Psychol . 1986 ; 51 : 1173 – 1182 .

Wanlass RL , Reutter SL , Kline AE . Communication among rehabilitation staff: “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” deficits ? Arch Phys Med Rehabil . 1992 ; 73 : 477 – 481 .

Lorish CD , Abraham N , Austin J , et al. . Disease and psychosocial factors related to physical functioning in rheumatoid arthritis . J Rheumatol . 1991 ; 18 : 1150 – 1157 .

Stucki G , Sangha O . Clinical quality management: putting the pieces together . Arthritis Care Res . 1996 ; 9 : 405 – 412 .

ICIDH-2: International Classification of Disability and Health. Prefinal draft . Geneva, Switzerland : World Health Organization ; 2000 .

Jette AM . Physical disablement concepts for physical therapy research and practice . Phys Ther . 1994 ; 74 : 380 – 386 .

Nagi S . Some conceptual issues in disability and rehabilitation . In: Sussman MB , eds. Sociology and Rehabilitation . Washington, DC : American Sociological Association ; 1965 : 100 – 113 .

ICIDH—International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps: A Manual of Classification Relating to the Consequences of Disease . Geneva, Switzerland : World Health Organization ; 1980 .