1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Submissions

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology is a constantly-growing collection of original essays on important philosophical topics, figures, and traditions. These essays are introductions rather than argumentative articles, although arguments or preferred positions on issues are sometimes suggested.

We’re always looking for authors to contribute. If you’re interested in contributing a 1000-word essay (or essays) on a philosophical topic that interests you and would interest our readers, please email us . Please either send us your full essay for review, or an essay proposal, or any other inquiries regarding the appropriateness and desirability of your topic and approach. We are currently focused on prioritizing essays on “core” topics typically addressed in introductory philosophy and ethics classes, so that our essays address nearly all the topics anyone would want or need to address in teaching such classes.

1000-Word Philosophy will only consider article submissions by philosophy instructors or advanced graduate students in philosophy who have extensive experience teaching philosophy. While the Editors wish to encourage philosophical writers at all stages, they have found that it is nearly impossible for someone to develop a successful essay for 1000-Word Philosophy if they do not have teaching experience and so, for efficiency, we have this requirement for submissions.

An incomplete list of desired essays is available here . We are especially interested in essays on topics frequently addressed in introductory courses, as well as topics that are difficult to cover in introductory courses because the relevant literature is difficult for beginning students. We especially welcome material addressing under-represented philosophical traditions, including global philosophy, philosophy of race, LGBTQIA issues, and more, as well as submissions on all topics by women and members of other under-represented populations.

We are open to the possibility of multiple essays on the same topic since there are always many useful ways of addressing any philosophical issue.

A Call for Papers flyer is available here . A graphic of that Call is below, suitable for saving and sharing. A call for essays to help address current events has been posted: please share it. Also, a “ t eaching units ” page has been created.

The style of essays published by 1000-Word Philosophy is best seen by reading the essays themselves ; please focus on the more recent essays as examples . We strive to publish essays that are radically concise, extremely clear, well-organized, and inviting . Each serves as an ideal introduction to the problem, question, issue, or figure. Essays should be clear and understandable to readers with little to no philosophical background. We hope the essays serve as a springboard for informed discussion and debate and a basis for further learning on the topics.

Typical features of our essays include:

- a short, inviting introduction;

- a “what this essay is about” statement at the end of the introduction;

- labeled and numbered sections: please do not italicize the section headings;

- short paragraphs that focus on only one topic: this is especially important for online publications;

- clear and direct explanation: never too little, never too much ;

- clear, simple, and direct language and word choices;

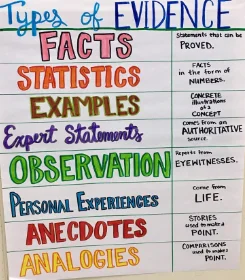

- vivid examples to illustrate abstract points;

- rigorous editing to eliminate any needless words, sentences, and sections;

- few to no rhetorical questions: explain the issues and make statements instead;

- little to no “name-dropping” for topical or issues-focused essays: focus on the ideas themselves, not the thinker who developed or articulated them: address that in the notes;

- at best, merely suggestive conclusions on issues, presented in tentative, discussion-provoking ways;

- an understanding of our intended audience—people who lack prior understanding of the issues of the article—and how they are are likely to approach issues, and so a presentation that works for them: article drafts should be “tested” with students and general readers, and revised in light of their feedback, before submission.

The 1000 word wordcount is of only the main text and headings: it does not include any endnotes or other text.

Submitting to 1000-Word Philosophy is not like submitting to a traditional academic journal. For article drafts or proposals that are promising, the typical review and editing-to-publication process involves feedback at many stages from multiple editors and sometimes external reviewers. These reviews address everything from the overall structure of the essay to the presentation of the philosophical issues to exact word choices. The editors seek to ensure that our essays meet high scholarly standards and are readily accessible to readers without any background in the topics. Accordingly, to meet our intended audiences, contributors with promising submissions can expect far more fine-grained and interactive feedback than at academic journals. This careful and meticulous process, however, results in very strong introductory essays that are understandable, interesting, and beneficial to nearly any reader.

A submission template is available in Word and Google Docs . Do not submit PDF files, as those are difficult to review. Essay submissions via links to a cloud-based platform, such as Google Docs, or Dropbox, or Microsoft OneDrive are welcome, especially if the file can be edited and commented on through that cloud service.

Please format your submission so it, as close as you can, resembles a published article at 1000-Word Philosophy . Please use 12-point Times New Roman font for all text, including any footnotes, left-justify or left-align all the text, single-space your submission, line break (not tab) for each paragraph (there are no tab indents online), use the standard footnote feature (not manually created notes), and add links to the references in the manner 1000-Word Philosophy essays typically have links: please examine recent essays to identify that style.

Acceptance Rate

We publish approximately 10% of essays that are submitted, usually after weeks of substantial revisions and editing.

Essays published at 1000-Word Philosophy are peer-reviewed publications.

Why Contribute?

1000-Word Philosophy has an extensive readership. In 2022, we had over 1,030,755 views and 663,361 visitors , and we are working to increase those numbers so your essay will be highly visible to a global readership. Some essays have over 100,000 views because, in part, they are used in courses. We are trying to identify better ways to track the use of the essays in teaching, and as sources for online discussion, and publicize these numbers. We are planning to compile the essays into a living – that is, constantly developing – open-access and open-source print collection that will be ideal for classroom use, as well as general readers.

For further discussion of why you might want to contribute an essay to this project, see this discussion at the Philosophers’ Cacoon blog . For more information on our reviewing process, see this article at the APA Blog .

If you are interested in developing ideal, high-impact materials for both teaching and public philosophy, then 1000-Word Philosophy is for you.

A 2022 End of Year Report is available here .

If you would like to provide financial support for this project, you may donate here . Thank you!

All essays are original contributions to 1000-Word Philosophy and are published with permission from the authors. Contributing authors retain any and all copyright interests in their individual works. 1000-Word Philosophy holds the copyright to the collective work. Do not reproduce this work in part or in full without appropriate attribution.

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:.

Seductive Delusions

A form of refuge, the first enchantment, a prayer for the dead, the classics, love in the age of the pickup artist, death is not the end, most popular, against advice, it’s all over, wanting bad things, on being an arsehole, submissions.

We accept submissions through Submittable for our thrice-yearly print journal, and for our website, which is updated continuously.

The Point is a magazine of philosophical writing that embodies two distinct but complementary convictions: on the one hand, that humanistic thinking has relevance for contemporary life; on the other, that our lives are full of experiences worth thinking about. We welcome submissions for our print journal, which is published three times a year, and for our website, which is updated continuously. Submissions are accepted through Submittable .

Each issue of the magazine has three main sections: ESSAYS, SYMPOSIUM and REVIEWS. Our essays blend memoir, criticism and journalism to examine the ideas and beliefs that shape our world. The symposium is a collection of responses to a question chosen by the editors (e.g., What is protest for? What is marriage for? What is privacy for?). Reviews can be about pretty much anything at all. Print essays run between 3,000 and 6,000 words; reviews and symposium articles are of medium length (1,500-3,000 words). We also accept ideas-driven reported pieces for our CORRESPONDENCE section (3,000-5,000 words).

Contributors whose articles appear in the print journal will be compensated. The website runs articles of any length but preferably of about 1,500-3,000 words.

Please note that The Point does not publish fiction or poetry, although we gladly accept criticism about fiction and poetry. As a general rule, we do not publish pure memoir or straight book/film reviews, but rather look for writing that combines some kind of personal or journalistic narrative with a philosophical or critical argument. The best way get a feel for our editorial inclinations is to read the magazine.

Simultaneous submissions are fine but we ask that you let us know promptly if the piece has been accepted elsewhere. Due to the volume of submissions and limited staff, we may not be able to respond to all inquiries, though we do try to respond when we can. If we are interested in a submission you will be notified.

Awards & Honors

2010 Pushcart Prize for Adam Bright’s “Here, Now” (issue 1)

2011 Pushcart special mention for Etay Zwick’s “Predatory Habits” (issue 2)

2012 Pushcart special mention for John Lingan’s “Salvation for Civilians” (issue 4)

Jonny Thakkar’s “Hail Mary Time” (issue 4)

2013 Pushcart special mention and Gawker’s Best of the Web for Emilie Shumway’s “My Job Search” (issue 5)

2014 Best American Essays for Timothy Aubry’s “A Matter of Life and Death” (issue 7)

Best American Essays honorable mention for Katharine Smyth’s “Prey” (issue 7)

Charles Comey’s “The Love We Use” (issue 7)

Barrett Swanson’s “Perilous Aesthetics” (issue 7)

Pushcart Prize for Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “Hell” (issue 9) .

Pushcart Prize for Adam Bright’s “Here, Now” (issue 1)

Pushcart special mention for Etay Zwick’s “Predatory Habits” (issue 2)

Pushcart special mention for John Lingan’s “Salvation for Civilians” (issue 4)

Jonny Thakkar’s “Hail Mary Time” (issue 4)

Pushcart special mention and Gawker’s Best of the Web for Emilie Shumway’s “My Job Search” (issue 5)

Best American Essays for Timothy Aubry’s “A Matter of Life and Death” (issue 7)

Best American Essays honorable mention for Katharine Smyth’s “Prey” (issue 7)

Barrett Swanson’s “Perilous Aesthetics” (issue 7)

Pushcart Prize for Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “Hell” (issue 9) .

2015 Pushcart Prize for David Unger’s “Fail Again” (issue 10)

Pushcart special mention for Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “The Insane Idea” (issue 11)

Charles Comey’s “Against Honeymoons” (issue 10)

Best American Essays honorable mention for S. G. Belknap’s “The Tragic Diet” (issue 9)

Dawn Herrera Helphand’s “Into the Cave” (issue 8)

Moira Weigel’s “Searching for Shanghai” (issue 8)

2016 Best American Essays 2016 for Charles Comey’s “Against Honeymoons” (issue 10)

Best American Essays honorable mention for Brandon Terry’s “After Ferguson” (issue 10)

Laurel Berger’s “The Magic of Untidiness” (online)

Lisa Ruddick’s “When Nothing Is Cool” (online)

David Unger’s “Fail Again” (issue 10)

2017 Pushcart Special Mention for Kris Lenz’s “Stendhal Syndrome” (issue 10)

2018 Pushcart special mention for Ben Jeffery’s “After the Flood” (issue 12)

Sophie Beck’s “Returning the Gaze” (issue 12)

Best American Essays Honorable Mention for Sophie Beck’s “Returning the Gaze.” (issue 12)

2015 Pushcart Prize for David Unger’s “Fail Again” (issue 10) Pushcart special mention for Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “The Insane Idea” (issue 11) Charles Comey’s “Against Honeymoons” (issue 10) Best American Essays honorable mention for S. G. Belknap’s “The Tragic Diet” (issue 9) Dawn Herrera Helphand’s “Into the Cave” (issue 8) Moira Weigel’s “Searching for Shanghai” (issue 8)

Best American Essays 2016 for Charles Comey’s “Against Honeymoons” (issue 10)

Best American Essays honorable mention for Brandon Terry’s “After Ferguson” (issue 10)

David Unger’s “Fail Again” (issue 10)

Pushcart Special Mention for Kris Lenz’s “Stendhal Syndrome” (issue 10)

Pushcart special mention for Ben Jeffery’s “After the Flood” (issue 12)

Sophie Beck’s “Returning the Gaze” (issue 12)

Best American Essays Honorable Mention for Sophie Beck’s “Returning the Gaze.” (issue 12)

Martha Nussbaum

Brandon Terry

Lorraine Daston

Yuval Levin

Robert Pippin

Moira Weigel

Barney Frank

Jacob Mikanowski

Lisa Ruddick

Slavoj Žižek

Terms & Conditions

In submitting the article, you warrant that it is original, that all the facts contained therein are true and accurate, that it does not infringe another's copyright or proprietary rights, and that the article has not appeared in any other publication in whole or in part. You will be deemed to have accepted these terms upon submission of your article.

The Point is run by a small and dedicated team that puts together the print issue, keeps the website fresh, organizes events, tables at literary festivals, and more. And while we keep things rolling throughout the year, we always appreciate any additional help. If you’d like to volunteer for The Point, we have a number of opportunities, from editorial assistance to repping the magazine on your college or university campus. Simply fill in the form below with your contact details and indicate what volunteer opportunities you’d be interested in (you can select more than one), and we’ll contact you when they come up. Do note that for editorial volunteer opportunities, more materials may be requested.

Get The Point newsletter delivered right to your inbox.

Find out about our upcoming events, latest articles and issue releases.

PhilosophYouth

Flash philosophy submissions, how it works.

Anyone may submit their flash philosophy piece for review.

All submissions undergo the PhilosophYouth review process to ensure that every piece published is high quality and up to par with our standards.

When an essay is published, the writer is credited and reserves the intellectual property rights to their work . PhilosophYouth does, however, reserve the right to retain or remove the piece on/from the PhilosophYouth website as we see fit.

How to Submit

Read our Submission Guidelines and ensure that your essay adheres to them.

Fill out the form at the end of this page.

A confirmation email (within 24 hours) will inform you that we have received your flash philosophy submission.

A follow-up email will arrive within 7-14 days updating you on the status of your piece and any next steps you must take.

Once your piece has been approved, we will update you with some final details before publishing it on our site.

Submission Guidelines

Submissions should be approximately 200 -500 words long, typically spanning just a few paragraphs and a maximum of one page (don't feel the need to fill the whole page).

We suggest this length because these flash philosophy pieces are meant to be bite-sized conversation starters rather than fully fleshed-out theories or lengthy treatises. Please be aware that as a conversation starter, some people will almost certainly have critiques of any philosophical idea. We welcome discussion (through the comments section), though we assure you that any personal attacks will not be tolerated.

This is a loose limit, but if you would like to submit a significantly shorter or longer piece, please don't hesitate to contact us and we'll be happy to consider your request.

We believe the best writing is concise and easily understandable .

Writing in the first person is accepted and encouraged, while unnecessarily stilted, dated, or complicated language is discouraged.

Feel free to use modern examples, but stay away from excessive and unnecessary slang or vulgarity.

Suggested Structure

Very quickly and briefly introduce your topic. Say what question or issue you will be tackling and your thesis statement (what single point you're trying to convince the reader of).

Explain your argument in a logical manner. Give reasons for all of your statements and conclusions, and never assume that the reader will just immediately believe what you say.

Try to include at least one strong counterargument and respond to it.

Conclude by clearly, concisely, and strongly coming back to the main premises and final conclusion of your argument.

Submissions must not under any circumstances contain plagiarism .

Quotes or ideas directly taken from or found in another person's work must be properly cited.

If you need help with in-text citation, simply do the best you can and make sure to include the links to all of your sources so that we can help make sure everything is cited properly.

Additional guidelines

- Each essay is reviewed by a real person, so if your essay is a bit out-of-the-box or there is anything that you think we should know about or that you think you need help with, feel free to include any personal notes or clarifications for the reviewer in the Notes section of the essay submission form.

Do not attempt to submit essays through email . You may follow up and inquire about essays through email, but any essays sent through email will not be considered. Only essays submitted through the proper form will be reviewed for publication.

You may send us any further questions through [email protected] or through our Contact Us page .

- What is the role of the discussion facilitator? The discussion facilitator helps everyone get the most out of each discussion session by kindling conversation, making sure that everyone gets the chance to share their thoughts, and maintaining the civil, productive, and philosophical qualities of the discussion. In the spirit of our mission and vision, PhilosophYouth discussion facilitators are not teachers but youth and, unlike philosophy teachers, are permitted to engage in the discussion in addition to leading it. Accordingly, any opinions expressed by our representatives are entirely their own, and we encourage you to challenge any opinions that you disagree with. If you are interested in becoming a PhilosophYouth discussion facilitator, you may volunteer at philosophyouth.org/volunteer.

- What will I learn at a Discussion Circle? The topics we discuss are different every single week, but the key central piece of every discussion is practicing how to think deeply about a problem, express your thoughts clearly, and be open to learning from the input of others. In addition to a regular venue for philosophical conversation, you will also gain exposure to a range of topics and, of course, to the diversity of thought that is always brought out in a round table discussion. Each discussion will make you think through a great conversation.

- Are discussion sessions like philosophy classes? Discussion sessions are similar to philosophy classes in that we spend the session exploring different problems through a philosophical lens, learning about the answers philosophy has provided, and developing our own solutions. However, they are different from philosophy classes in that there is no lecturer or formal teacher, and everyone is given an equal opportunity to speak their mind and develop their ideas.

- Do I need to study or prepare before joining a discussion session? PhilosophYouth exists for the benefit and enjoyment of young philosophers, so our discussion sessions never require or assume any prerequisite knowledge. We do sometimes provide a simple primer and a few extra resources together with the topic once it is released, but it is all optional and provided only to improve your discussion experience.

- Who is allowed to join? Anyone! Whether this will be your first experience with philosophy or your thousandth, anyone is free to join, as the community-based nature of each discussion session ensures that it will be engaging for anyone who attends. We would like to note, however, that PhilosophYouth is geared primarily toward younger people (most of our members are in high school or college), though adults are welcome to come and join the conversation as well. Parents who want to supervise their child's first discussion session with PhilosophYouth are also welcome to sit in.

- Do I need to apply or become a member before I can join a session? All you have to do to join is fill out the short form below! Simply follow the instructions listed above, confirm your slot, and you will receive the Zoom details through email. After your first session, you will receive a follow-up email asking whether you would like to become a member and continue philosophizing with PhilosophYouth. If you agree, you will officially become a member (you may opt out any time) and gain access to our private Discord server.

- Can participants get a Certificate for joining? Unfortunately the fluid nature of discussions means that we cannot provide a certificate guaranteeing that you completed a particular curriculum. We can, however, provide a Certificate of Membership to members who request it. This certificate will indicate how many discussion sessions you have participated in and any written work you may have published with PhilosophYouth.

- My question wasn't answered here. Where can I ask it? Please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected]. You may also use the form on the Contact Us page, and we will get back to you shortly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Flash philosophy submission form.

Thank you for submitting your essay! You will receive a confirmation email in the next 7 days updating you on the status of your submission.

- Funding Opportunities

- Discussion-Based Events

- Graduate Programs

- Ideas that Shape the World

- Digital Community

- Planned Giving

How to Publish Your Paper in a Top Philosophy Journal

What is the process for publishing your paper in a top-ranking journal? The interview below provides an in-depth look at the paper submission process from a philosopher’s perspective. Jeanne Hoffman interviews IHS’s Philosophy Program Officer, Dr. Bill Glod to get his thoughts on getting papers written in the first place, what to do when the editors of a journal are taking months to make a decision, and how to go about revising and resubmitting your paper if necessary.

Read the interview below:

Jeanne Hoffman: Today is the first installment in our new series on the Journal Submission Process for each discipline. My first guest is IHS Program Officer, Dr. Bill Glod to talk about the Journal Submission Process in Philosophy. Welcome, and thanks for joining us.

Bill Glod: Well thanks for having me, I’m glad I just had to talk about Philosophy, I was starting to plan … well, I don’t know about other disciplines. I may not know about Philosophy either, but we’ll see.

Jeanne Hoffman: Let’s go a little earlier than the journal submission process. What about writing the article itself?

Bill Glod: That’s a good question.

Usually, during the early stages of the paper, I go wild, I just write down every crazy idea, crazy assertion in search of an argument that I can think of. There’s no holds barred on what is actually a crazy idea. So I want to gather as much of those as possible. I’ll scrap most of them, of course, but they will give me somewhat of an idea, sort of how the paper, the direction it’s going to go and some of the particulars, hopefully, original insights. I don’t think you can have much originality without getting crazy stuff down first. So that’s the first stage.

I actually don’t do a ton of reading either. I prefer writing so much more, and so I usually, when I’m planning about a particular paper I want to write, a journal article usually, I want to limit my engagement to about two inter-lockers. These are two particular authors or topics to use as sort of the foil of my article. Preferably these are things that have been published as recent articles in high tier journals, maybe the highest tier journal in the discipline. And articles defending some particular thesis that I want to rebut.

I think it’s good to mention I try to avoid devoting an entire article to rebutting one author’s claims unless that author is sort of the top expert in his or her field. Journals typically like you to focus on two, at least two authors, two topics. It’ll only really make sense to focus on one author’s topic if you are following up on an article within the particular issue of a journal, but that’s usually a smaller article, not a feature-length kind of 20 page thing.

Jeanne Hoffman: So then since you kind of do your writing first, do you go back and do your citations after you looked up sources afterwards? What’s your process for that?

Bill Glod: What I try to do is extract the quotations from the articles that I’m going to address, especially the specific quotations that will be my biggest challenge. Of course, I want to frame the foil’s arguments in the best possible light. As far as going back and citing things, that’s usually the last stage of the process. I have the articles gathered, I have the page numbers sort of parenthetically marked beside them. I try to avoid populating every footnote with as many citations as I can find. That may be a sign that you’re a well read scholar or it may be a sign that you’re trying too hard, so I think in some cases … I’ve never had an issue with let’s say referees saying, “well you didn’t cite enough stuff”. There may be other issues that I’ve had with papers that referees have found, but it’s not been a matter of the citation.

As far as going back and citing things, that’s usually the last stage of the process. I have the articles gathered, I have the page numbers sort of parenthetically marked beside them. One thing I try to avoid is populating every footnote with as many citations as I can find. That may be a sign that you’re a well-read scholar or it may be a sign that you’re trying too hard. I’ve never had an issue with let’s say referees saying, “well you didn’t cite enough stuff.” There may be other issues that I’ve had with papers that referees have found, but it’s not been a matter of the citation.

Unless your discipline or something about the nature of your paper requires a lot of citations, don’t go out of your way to do it. There are opportunity costs.

Jeanne Hoffman: What about revisions? I know the average highly intelligent person coming out of college is probably used to being able to throw together a stream of consciousness paper for a professor and getting an A. What about in grad school and beyond?

Bill Glod: I’m not smart enough to do that at a sophisticated level. I know some people who have that ability, but I rewrite the same paper over and over. Not every revision is sort of a whole scale reconstruction, but I usually for an article that makes it into print, I’ve rewritten the thing in some degree at least two dozen times. Now I like to kill trees sometimes, I like to sort of walk around with a paper and mark it up and things like that and do like a print out a new copy once I’ve made the revisions of the previous marked up copy, but I’ll do that about two dozen times at least for any paper because there’s always something new to find.

Something I forgot to mention from earlier is when I’m engaging the particular authors that I want to critique, I try to be Socratic. I try to give an internal critique of their arguments, so as much as possible. So I say well, they have this particular premise that I share with them, but I think that that premise actually leads to different conclusions than they support. I think that’s a really powerful way to engage people who disagree with you on a particular issue without just butting heads. If you don’t have any common ground with the person you’re critiquing, not only is it just not an interesting paper, it doesn’t really advance anything and it doesn’t really convince anybody so I try to do that as much as possible.

I also try to look for volunteers to read my papers at various stages of completion. So I don’t want to wait to share a polished piece because I want to know early on if I’m barking up the wrong tree. If readers think I’m just wasting my time with a silly argument or if it’s a topic that nobody cares about or if it’s a topic that’s already been addressed that I wasn’t aware of, then I try to sort of nip that in the bud so I’m not wasting time and stuff like that.

I want somebody’s input on whether I’m making an original argument or not.

Jeanne Hoffman : How do you know that the article is ready for submission and that you should send it off?

Bill Glod : Sometimes it comes from somebody, external pair of eyes who can say “this looks ready to ship off” and sometimes it’s just once you’ve been doing this long enough, it’s sort of an intuition that you have. So there’s no sort of hard-and-fast set of criteria for determining when is this ready to go out, but I would say that you shouldn’t tinker with a paper endlessly. Once it feels roughly finished, then I think that’s when you should submit it. Then let the referees be the unpaid research assistants. If you spend so much time tinkering with the paper that the marginal benefits of that are far outweighed by the cost of it sitting there gathering dust on your desk. Get it out for review. If there are substantive changes that need to be made to your argument, good referees will be able to highlight that.

Jeanne Hoffman : For law, when you’re submitting an article, you’re allowed to simultaneously submit to journals. I know that isn’t true for Philosophy. What’s the process that you have to go through and what do you need to think about when submitting an article?

Bill Glod : Well, that’s true, you can only submit to one journal at a time. The Philosophy journal world is pretty small and if you get a reputation for submitting your article to multiple journals, you’re going to be blacklisted.

Now as far as the actual submission process itself, it varies by journal-to-journal. So you can find information about journal turnaround times, there are Wiki links, there’s a Philosophy journal Wiki on that. The link doesn’t come to mind but I think we could probably chase it down and include it with this. But as far as the particular process goes, it will depend. Some journals have really quick turnaround times, two to three months, where the referees will get you the feedback and it’s rejected, revised or you know, the ask for a revision or it’s accepted.

Typically, it’s rare to get a straight up acceptance after three months, but it’s been known to happen. That’s sort of the first stage.

I like to keep a list of my working papers. So I have about four or five working papers right now at various stages of completion. I also like to keep on that same piece of paper the list of articles that I’ve already published just to remind myself that it can be done. Just to have that all out in front of me helps give me an idea of what my goals are near term and longer term. This way, like I said, I have five working papers at various stages of completion. Some are maybe, I think ready within a few weeks and some other ones are probably not going to be ready until next year, but having that there I think is valuable to have and I always cycle the papers that I work on. I don’t try to work on the same one until it drives me nuts. I sort of take a break and then work on a different one and then come back to the original one. Oftentimes I find that I have a fresh take on the paper that I didn’t have before once I returned to it.

As far as what journals one should aim for, what I try to do is aim for the higher tier, mainstream journals in my field. I don’t care about quick turnaround times and I think people get too hung up on quick turnaround times. Now it’s easy to say when you’re going on the job market and you want to get that publication line on your CV and you’re tempted to say “well, this journal isn’t as highly ranked as this other one, but it has a quicker turnaround time.”

I would recommend getting into the mindset of not concerning yourself too much with turnaround times. I know that some of the better journals out there will tend to take longer, but I think you should still aim high. Don’t give up the chance to publish in Ethics , the Journal Ethics , just for the sake of a quicker turnaround time.

So that’s as far as what to aim for, I think you should definitely look at the journal ranking and discount the value of the turnaround time.

Jeanne Hoffman: What about looking at those high ranking journals and trying to figure out which one you should submit to if they’re all good, and they have a three to four month turnaround time, what should I aim for? Which one should I look at?

Speaker 2 : It depends on your topic. You’ll know which journals are sort of the best for your particular specialty, so if you’re writing an article on ethics, you can aim for Journal of Philosophy, getting it published there or Phil Review or things like that. Those are going to be great places to get published. Those are overall generally very highly ranked journals. But also Ethics, the main journal for Ethical Philosophy, Journal of Political Philosophy, those are some of the really top things and there’s pretty much a consensus that those are some of the top journals in a particular field.

For instance, ethics or political Philosophy, that knowledge is out there, but I think that in some cases, it would help you if you’re not able to get your paper into the big guns, knowing who’s on the editorial board can often be helpful information. You should take a look at all the journals, they’ll list their various editors and if you see people whose work you like and you want to try to get your work in front of them, then familiarity with who’s on a particular journal’s editorial board will possibly increase your chances.

Also, I think something helpful to do when you submit your paper is to be helpful to the editor. As an editor at a journal, one of the hardest things to find sometimes is a referee who is qualified enough, an expert on the topic who can give quality feedback on your submission, but oftentimes, the editor doesn’t know who this person is or not only that, they don’t know who to identify who would be reliable at giving feedback.

So if you know somebody who might be able to do this, then it doesn’t hurt to suggest some possible referees for you paper. Now you need to be ethical about this. If this person knows it’s your work when they get it in front of them, then it’s no longer a blind review process. But if you know some people in your field who, if you had your choice, you would like them to see your paper, then it doesn’t hurt to suggest some possible referees to the editor and just sort of help him along and say hey, this person’s not familiar with my work, they wouldn’t know it’s me, so if you’re looking for somebody, these are some possible names that you might consider cause again, editors will appreciate that.

Of course, the can always decide to pick their own, so that input isn’t really going to sway anything negatively or unethically. It’s not sleazy to do that.

Jeanne Hoffman: If I sent a paper off, five months goes by, I haven’t heard a thing, what do I do, given that I signed that contract is my paper basically on hold until they get back to me?

Bill Glod : Your paper is your property, you can remove it at any time. So if you don’t like that a journal’s taking too long, or if they’re not being straight with you, you can decide, “I’m going to shop it somewhere else.” Hopefully, that doesn’t happen, but if you find yourself in that situation, they can’t hold your paper hostage.

Usually what journals do when you submit the paper is to say, “Thanks, you’ll hear back, we hope to have a verdict within three or four months.” So I would say that if those months go by and you haven’t heard anything, it’s fine to make a polite inquiry. Now, don’t be annoying. Don’t make an inquiry eight weeks after you’ve submitted your paper and say, “Have you got it yet?” That will just give them a reason to reject your paper.

If you still want to keep your paper at a journal and it’s taking longer than you’d like and that happens a lot, cause a lot of times the editors are trying to find referees, I would say a polite inquiry if you haven’t heard anything in four or five months is perfectly acceptable and professional thing to do.

Jeanne Hoffman: What’s the difference between a revise and a resubmit and a conditional acceptance?

Speaker 2: Oh, okay, that’s a good question. A revise and resubmit usually involves there needing to be a more substantive change to your paper, so maybe one or both of the referees thinks “this paper is promising, I think it’s possibly on its way to being published, but there’s some, at least one perhaps major issue or problem in the argument that you need to address as the author” to the referee’s satisfaction. So I think that revised resubmits tend to call for more substantive changes. Conditional acceptances are basically ones where they say “we will publish your paper.” You just need to address a couple of things here or there, and they tend to be minor suggestions. I think that’s the main difference.

Now revise and resubmit is nothing to hang your head about. Of course, it’s a lot of work, in many cases to have to address the referee’s concerns, but I would say about 60 to 70 percent of revise resubmits end up being accepted if you do decide to resubmit them.

Jeanne Hoffman: Do you think people always put the work into revise and resubmit so is the 60, 70 based on whatever people send in or if you really dedicate yourself to following the referee’s suggestions, do you think you have a higher chance?

Bill Glod: That’s a good question. I think that at least the last two revise resubmits that I’ve gotten have all eventually been accepted, both of them were eventually accepted. But I did put a lot of work in. In some ca, es it seems like it’s more work than what you put into the original article because you want to get this thing right and you want to address the referee’s concerns, if they are valid concerns. A lot of times there’s additional work involved because what the request is for you to have a separate sheet where you go through each of the referees concerns and then explain how you addressed them in the paper. But it really depends. Some people literally just mail in their resubmissions, and I’m sure that doesn’t help their cause.

I’ve found that as long as you’re earnest and you think that the referee suggestions and the revisions have made this a better paper, it’s recognizably your own and you’re still defending a thesis that you want to defend. Then you have really good chances of placing the paper once you’ve worked hard at revising it.

Jeanne Hoffman: So in conditional acceptances, if the ref says “you just need to do this one thing and your paper’s published,” and I think the ref is wrong, do I have any leeway on that or do I have to withdraw my paper at that point?

Bill Glod : I think it depends on the editor, I mean if you’re just upfront and honest and say look if I do this suggestion, I think it’s going to change the paper, then it depends. The editor might say, “Okay, I understand that,” because they still might want to publish your article, right? You have some leverage here.

But again, it depends upon the nature of what they think needs to be changed and if in your mind the change affects or degrades the integrity of your paper or changes your argument. In the end, it’s your work that you want to publish. You don’t want to get a publication line defending an argument that isn’t you, that isn’t what you earnestly believe.

Otherwise, what’s the point? You’re basically just writing a fraud paper.

Jeanne Hoffman: Let’s say I’m about two years from going on the job market and I have this paper I really want to get published and I’m hitting up the higher ranked journals, so I’d say that gives me maybe what, four to six submissions depending on how fast the turnaround time is in that time period. If I’m not getting any luck with those journals and I want to have something on my resume by the time I go on the job market, should I give up on the higher ranked journals and shoot lower and go for a sure thing or should I still continue to put the effort into the higher ranked journals?

Speaker 2: Well, I’m not sure if I have a directly satisfying answer to this question. I think it underscores the importance while you’re a grad student of getting papers under review early on in the process, so don’t wait until the year you go on the market. This is why I think it’s important from day one of your grad program to think about giving yourself the time to submit publishable, quality work and I think by that time if you aim for the top journals and they end up rejecting them while it goes through a process, hopefully you’ll get some feedback and even if it gets rejected at maybe the top three journals in your field, hopefully, you’ll have amassed enough feedback by then, you’ve had like six referees look at it, and maybe this paper will be so improved that maybe it will be able to get into a still a very good journal by the time you’re going on the market, so I think in a way, the response to the question is really preparation. You’re going to have to prepare. You need to prepare early on in your program so that you’re not facing this tough choice about well, I could submit to a lower ranked journal cause it has a quicker turnaround time. Try to avoid putting yourself in that position.

But it may depend upon what your advisor says in this matter. If they say look, you’re CV needs to have a couple of lines on it, then maybe, in this case, it would make sense to do that. But general, I would say that you should aim for the highest ranked places that you think your article has a chance of getting published in and then work down from there. Keep a rank ordering of five or six journals. If your paper gets rejected by one journal, you can send it right out to the next journal.

Whatever you do, just don’t hang your head too long over the rejection.

Jeanne Hoffman : Well thanks so much for joining us, Dr. Glod.

Bill Glod: Thank you.

Previous Post How to prioritize (and complete) the coursework for your PhD program

Next post 9 questions to help you prepare for your academic conference presentation.

Comments are closed.

- Privacy Policy

© 2024 Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University

Here is the timeline for our application process:

- Apply for a position

- An HR team member will review your application submission

- If selected for consideration, you will speak with a recruiter

- If your experience and skills match the role, you will interview with the hiring manager

- If you are a potential fit for the position, you will interview with additional staff members

- If you are the candidate chosen, we will extend a job offer

All candidates will be notified regarding the status of their application within two to three weeks of submission. As new positions often become available, we encourage you to visit our site frequently for additional opportunities that align with your interests and skills.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Why Publish with PQ?

- About The Philosophical Quarterly

- About the Scots Philosophical Association

- About the University of St. Andrews

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Chairman of the Editorial Board

Franz Berto

About the journal

The Philosophical Quarterly is one of the most highly regarded and established academic journals in philosophy.

Call for Papers: New Work on Epistemic Injustice

Featuring both invited papers and papers selected from among those submitted in response to this Call for Papers, this volume aims to showcase new work on epistemic injustice. We welcome contributions focusing on both highly theoretical and applied issues having to do with epistemic injustice, broadly construed. Deadline for submissions: June 30, 2024.

Submit your work

Love, Sex, and Parenting

One sometimes hears stories to the effect that analytic philosophy is intrinsically incapable of dealing fruitfully with weighty practical, social and political matters, but in recent years analytic philosophy has been undergoing a ‘practical turn’, with scholars in this tradition getting more and more involved with those weighty matters. As such, the editors of PQ have compiled a new virtual issue featuring a selection of articles focusing on the topic of 'Love, Sex, and Parenting'. All articles have been made free to read for a limited time.

Read the collection

The Scots Philosophical Association

The Philosophical Quarterly is jointly owned by the Scots Philosophical Association (SPA), whose initiatives promote the research, teaching and broader dissemination of philosophy in Scotland.

PQ Scholarships

The St Andrews Philosophy Department uses revenues from The Philosophical Quarterly to fund doctoral studentships in the St Andrews-Stirling Graduate Programme, covering both maintenance and fees for three years.

Latest articles

Email alerts

Register to receive email alerts as soon as new content from The Philosophical Quarterly is published online.

Accepting high quality papers relating to all aspects of philosophy, the Philosophical Quarterly regularly publishes articles, discussions and reviews, and runs an annual Essay Prize. The outstanding book review section provides peer review and comment on significant philosophical books. We aim to offer authors speedy decisions on manuscripts submitted, and currently 90% of submissions are processed within three months.

Find out how to submit

OUP Philosophy on Twitter

Follow us for the latest Philosophy news, resources, and insights from Oxford University Press, including updates and free articles from the Philosophical Quarterly .

Related Titles

- Contact the University of St. Andrews

- Contact the Scots Philosophical Association

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1467-9213

- Print ISSN 0031-8094

- Copyright © 2024 Scots Philosophical Association and the University of St. Andrews

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How to Publish in Philosophy

How to Publish in Philosophy and Political Theory

Alan Coffee (King’s College London)

I – The Process

- What to publish

- There are a great many ways to publish your ideas and work: blogging, online forums and academic websites, conference papers and proceedings, book reviews, replies to other authors and papers, survey articles, book chapters, handbook chapters, peer-reviewed journal articles. There is a value in doing each of these and most academics will do most at some point in their careers.

- I focus here on peer-reviewed journal articles. These are focused, tightly argued treatments of a particular idea that has been worked through in meticulous detail.

- From this perspective, publishing some of the other kinds of writing listed above (e.g. book reviews or blog articles) can often serve as preparation for later article writing. They give us some practice at writing and provide opportunities for criticism and feedback (this isn’t to say that these forms of writing don’t have their own unique value too, only that if you are aiming to publish journal articles then your plan should include these too).

- Journal Articles: Overview of the process

- Publishing in journal articles is an extremely slow process . Acceptance rates are very low. Rejection is normal for all academics even well into their careers. The review process always takes several months and can even last up to a year. It will certainly take months if not years before even an accepted article actually appears in print!

- Don’t make acceptance your sole purpose . Your primary aim at first is to get good feedback. This is a worthwhile goal in its own right. A reviewer is someone who will read your work more closely than almost anyone other than your supervisor. Getting as many fresh and new perspectives from reviewers is the most valuable thing you can have in philosophy.

The review process is roughly as follows.

- Review by the editorial staff (typically this takes about 30 days, though I’ve had between 3-50 days). The editor decides if the paper is good enough to send out to reviewers. Even getting past this stage is an important milestone in anyone’s career.

- Peer review by 2-3 reviewers . This normally takes about 3 months (though I’ve had it take over a year). Personally, I chase up the editor at the 100 day mark.

- The decision . There are normally four outcomes: (1) accepted as it is (rare); (2) accepted with some fairly innocuous changes to be made; (3) rejected outright (sadly very common); (4) rejected but with an invitation to resubmit often with some very detailed comments to help you do this (“revise and resubmit”, an extremely common step towards eventual publication).

If you are asked to revise and resubmit the normal time frame is 12-18 months. You can do it much more quickly but since you have the opportunity to get it right if you do what the reviewers ask then it is wise to take a good proportion of the time they offer. The revisions are normally substantial and the invitation to resubmit is invariably a one-time offer.

It may easily take another couple of months before the final decision.

- Print . Once your paper is accepted it may well be another six months before it appears “online early” at the journal and another six (I’ve had much longer) before appearing in print.

- Duration . Assuming that it took you a year to write an article that was ready to be sent out (a fairly typical length of time), then based on the timings given above, an article that goes through the revise/resubmit process could easily take an additional 18 months before being accepted, and further year before anyone actually sees it. From start to finish, that’s three and a half years!

- Acceptance rates

- Journal acceptance rates are astonishingly low. It is not unusual for a top tier journal to have a 2-5% acceptance rate and most reputable journals have no more than 15-20%. Given that these journals attract the best writers, then even seasoned academics are routinely rejected.

- You can check journal acceptance rates on their websites and a number of academic site run comparisons.

- The quality and quantity of critical feedback from editors and reviewers is very varied. If you haven’t received any, then always ask. Every editor knows how important this is to you. Most are sympathetic.

Even when you’ve had some feedback, it’s amazing what a politely worded response – thanking them for having helped you even though the outcome is disappointing – can do. More than once an email like that has triggered a far more personal and detailed set of comments and advice that I’ve been genuinely grateful for.

- Very quickly one learns the kinds of things that only come with experience: how to express yourself more clearly and precisely; how to formulate a single, clear line of argument that others actually can follow; what is strictly necessary for your argument; what kinds of details or side issues to leave out; and what sort of literature base to include.

- Selecting a journal

- Even being rejected can take a long time so it’s important to make sure you pick a suitable journal. You don’t want to sell yourself short but neither do you want to waste time. If you are aiming at the job market then finding a journal will have the right level of credibility for you will be a determining factor.

- You should also be sure to choose a journal that is likely to publish on your subject. Editors are apparently frequently astonished at the number of people who seem not to have ever read their journal before submitting. So always browse the website first. You should also look at the names of people who have published there to see if they are in your field and check the members of the editorial board (the group of academic advisors who oversee the journal. There will be a list on the journal’s website). If you have never heard of any of them then this does not bode well.

- Personally, I invariably write to the journal editor first with a brief email asking whether my idea sounds like a good fit. I’ve always had a nice response and it has given me a positive lift during the long months of waiting.

II – Writing

Writing an article is something of an art form. Any good PhD candidate has mastered enough general philosophy and knows enough about a specialised area to publish something in a decent venue. The stumbling block comes in how to present your ideas. It takes time to develop the requisite skills in presenting an argument. You have to identify a suitably interesting and narrow argument, you need to express yourself in a way that inspires confidence in your readers, and you must avoid raising unnecessary objections in their mind. Often this will be as much about tone, pace and pitch as it will about logic and principle.

- More than perhaps any other piece of writing, a journal article is a focused piece of work. An article should say only one thing. (If it says more, then the supplementary messages should not distract from the article’s main focus but be merely bi-products of making that primary point).

- For an editor and reviewer to agree that a paper is ready for publication it must be clear what its contribution to the literature and debate is. Focusing on a single point achieves two aims. (1) First, your reader can see what the paper’s contribution is. (2) It gives you the opportunity to go deeply enough into an issue to say anything worthwhile.

- A good article gets straight to the point. The first lines tell you exactly what it will be about, and why this is important and interesting.

- The only material that makes it into the final article must be justified according to whether it helps make the paper’s overall argument. If it doesn’t then it must be left out. While this might seem disappointing, it should be seen positively. Save this point for your next paper!

(A piece of advice a film documentary maker once gave me was that almost invariably, the idea to which you are most wedded and which excites you most, that’s the idea that has to be cut! It often just doesn’t fit and is being shoehorned in because you like it so much. Be ruthless, she said.)

- Identifying a single line of argument isn’t always easy. It is particularly difficult for someone is doing or has recently completed a PhD because they have so much to say.

Depending on how original or offbeat your work is, you may often find that to make a point, you have to first prove something else, but this second point only seems to make sense once you have established that first point. Extracting just one line for an article sometimes seems hopeless! But as you build up a body of work, this problem normally diminishes as you can then simply cite your earlier paper and concentrate on the matter in hand.

(By the way, writing a BA or MA essay is no different from writing an article in respect to focus: Get straight to the point. Make one point. Go deeper into it . It’s that simple).

- It’s important to find a style and tone that suits you. This takes time to work out. Generally, you should use as much natural language as possible. Short, direct sentences, using your own words are invariably easier to understand than technical jargon. It also exudes confidence and is actually more impressive than long-winded turns of phrase.

- Sometimes brevity is forced upon you. It is often difficult to meet the journal’s word count limit (often only 8,000 – 10,000 words) while saying everything you want to say. In these cases you will often find yourself editing out all unnecessary words, not only shortening the paper but making it sharper and crisper into the bargain.

- As a general rule I can usually cut around 1,000 words without actually losing any substantive points. It’s amazing how many additional ‘that’s other tiny words creep into one’s writing.

- Sections : Articles comprise several sections. There is no fixed number of these. But a section needs to be long enough to say something worthwhile and yet short enough to address a coherent sub-topic. Between 3-5 sections is a good number. Each represents a mini chapter, having an introduction to the new point, an argument and a conclusion that links it to the next section. I find that it usually takes 1,500 – 2,500 to do this effectively. But articles vary considerably so look through papers you found clearly written and find what works for you.

- Paragraphs : A good paragraph makes a single substantive point. If the paragraph is too short then it’s doubtful that a serious enough point has been made (if a paragraph is less than about five sentences or 100 words then perhaps it should be extended, cut or reworked to fit with another point). If a paragraph is too long then it probably contains too many separate ideas. I find that 200-300 words works best for me.

Combining the two points above, if we assume an average paragraph length of, say, 250 words and section length of, say, 2000, then a section might contain 8 paragraphs. This means that you can make about 8 separate points in that section. In that case, you should be able to get from the start of the new topic that the section introduces to the brink of the next new topic in 8 clear steps corresponding to your paragraphs.

The same principle applies to the whole paper. If there are four sections in a shortish paper, then you will have around 24 paragraphs – or discrete moves – at your disposal. When you are planning and organising your paper, it is sometimes helpful to set these out as 24 bullet points to assess the flow of your argument.

As a rule, the first line of a paragraph should tell you what it’s about. A good way to review your own work is to read off the first line of each paragraph, watching to see if this does correspond to the shape of the argument you have outlined. Is this story coherent or complete?

- Repetition : There is no room for any repetition when you have only (say) 24 points to make. Always try to keep related material together in one place and refer back to it only rarely. This isn’t easy to do but it is good a practice to learn.

- Pitch : It is often hard to know how much background to include when writing an article. Context is very important and not all readers will be familiar with the subject. On the other hand, too much detail is tedious and confusing. Often when you first encounter a new area the temptation is to put in too many basic or elementary points that don’t distinguish your paper. I find that by telling myself (and telling others) the story over and over again, I naturally start to drop the deadwood and eventually cut straight to the chase.

- Editing : A polished paper buys you a lot of goodwill with editors and reviewers. While it may not make the difference between acceptance and rejection, a carefully written paper that is free from typos and actually conforms to the style guidelines of the journal will very often receive more detailed and helpful feedback from reviewers who appreciate the care that has gone into the production.

- Putting pen to paper

- Start writing straightaway. Putting pen to paper clarifies one’s thoughts. You can have a great idea in your mind but it is only when you put it into written words that it becomes clear how much preliminary explanation is needed, how many convoluted separate strands of argument there actually are, how significant the objections actually are, and how vague and unclear many of your brilliant-sounding points turn out to be when they are set out in writing.

- Of course you need to plan your article carefully and so writing and planning go together as part of an iterative process. You should always write to a plan. But when you are first faced with a blank piece of paper the mere act of writing often serves as a catalyst for ideas to flow.

- It is always best to block off substantial chunks of time. Writing philosophy is intellectually challenging. One has several balls in the air (or plates spinning on poles) at the same time. A good argument brings together several complicated ideas and objections. All of this takes a fair amount of time and concentration to work up in your mind. I have heard it said that it takes about an hour to ‘warm up’ and get to the point at which you have all the different parts of the argument in your mind. If you have only set aside an hour then you may well not benefit from this.

- Responding to review points

- Getting feedback from reviewers is one of the best things that can happen from the publishing process, irrespective of outcome. This is true even when the review is severe.

- It is through the review that you improve your writing. Even if the reviewer is wrong it is extremely useful to understand how your arguments are perceived by people from outside your circle. I had learned to write for my supervisor during my PhD. She came to understand everything I was saying and I learned to anticipate her particular viewpoint. So I was astonished to find just how differently my writing was perceived by others, especially in the harsh world of anonymous peer review. (It’s only harsh at first. Once you find your way around it you soon discover how to avoid many of the negative comments).

- Review points should be taken seriously. Publication depends on it. This does not mean, however, that you have to accommodate every comment that each reviewer makes. For one thing, this might not be possible as there can be three or even four separate reviewers. For another, reviewers do not always get things right. Nevertheless, since the comments have come from the people who hold the future of your paper in their hands, you must engage seriously with them.

- I often find it helpful to write a response letter to the editors and reviewers explaining how I understood their points and setting out my proposed course of action. If I want to push back against a comment, I do it there explaining why I cannot accommodate that particular point. The advantage of doing this is first that it allows me to take stock of the situation as a whole, linking related points and distilling these into various levels of seriousness to the argument and importance in terms of action from me. A second benefit is that it allows the editor to give me at least an indication that this approach is acceptable before I dedicate several months to the process. Finally, from the feedback from reviewers it does often placate them by showing that I thought carefully about what they’d said even if I reacted differently.

- Finally, it’s not unusual to receive two reports with opposite conclusions. (Perhaps editors choose referees with this in mind.) There is often a ‘good cop’ that understands what you are saying and is broadly supportive and a ‘bad cop’ that hates what you’ve done and isn’t afraid to say it. Sometimes the latter comes from a slightly different part of the discipline (especially if you work in a cross-disciplinary field) which highlights the often very precise locations of the tight borders that exist between very narrow fields. While this is irritating, you should take heart. It is all useful feedback.

Appendix – Some links and resources

- General advice (Thom Brooks)

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1085245

- Advice from editors

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/jan/03/how-to-get-published-in-an-academic-journal-top-tips-from-editors

- Writing tips

http://faculty.washington.edu/mbrown/writing.pdf

- Embracing rejection

https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2013/07/08/essay-importance-rejection-academic-careers

The Writing Desk

Welcome to the first issue of The Raven, a magazine devoted to reviving the tradition of philosophical literature that deserves to be called literature. The Raven will publish original philosophy that is welcoming to readers with or without academic training in philosophy.

Although “public philosophy” as currently practiced benefits the profession of philosophy—and, one hopes, the public as well—it rarely involves practicing the discipline of philosophy in public. It tends to address issues that are already of interest to a non-academic audience, in a manner already familiar to it. We believe that philosophy worth claiming public attention can do more. The Raven will invite its audience to consider specifically philosophical questions and apply philosophical methods to them.

The launch of this magazine is a confluence of two different streams of experience. One of us was disappointed as an academic philosopher to see the philosophical literature professionalized at the expense of the humane concerns and tastes to which it spoke until recently. The other was frustrated as a journalist and magazine editor to see popular literary magazines publishing essays that parade as philosophy but are nothing of the sort. We both wanted to read philosophy that’s intellectually ambitious but professionally unassuming.

Of course, there are philosophical topics that require specialist knowledge or skills, and it is not our aim to popularize them. But large swathes of philosophy can be intriguing and approachable to large swathes of the educated public. Today’s philosophers are still referring to Harry Frankfurt’s “Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person,” Susan Wolf’s “Moral Saints,” or Thomas Nagel’s “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”—thought-provoking essays published in an earlier era by prestigious professional journals in which one would be hard pressed to find their like today.

Not all of our offerings will emulate those classics. The Raven is a magazine, not an academic journal, and so it is committed to offering a variety of reader experiences. In addition to feature-length articles, we will publish shorter philosophical notes, sometimes with an eye to popular trends, as well as book reviews. And our mission will no doubt evolve as we learn what writers want to write and readers want to read.

The magazine would not be possible without the support of the William H. Miller III Philosophy Department of Johns Hopkins University, our editorial committee, and our contributors. With their help, we hope to grow and flourish in a way pleasing to you, our readers.

For news about The Raven, please follow us on Twitter and Facebook .

- Advanced Search

- All new items

- Journal articles

- Manuscripts

- All Categories

- Metaphysics and Epistemology

- Epistemology

- Metaphilosophy

- Metaphysics

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Religion

- Value Theory

- Applied Ethics

- Meta-Ethics

- Normative Ethics

- Philosophy of Gender, Race, and Sexuality

- Philosophy of Law

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Value Theory, Miscellaneous

- Science, Logic, and Mathematics

- Logic and Philosophy of Logic

- Philosophy of Biology

- Philosophy of Cognitive Science

- Philosophy of Computing and Information

- Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Physical Science

- Philosophy of Social Science

- Philosophy of Probability

- General Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Science, Misc

- History of Western Philosophy

- Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy

- Medieval and Renaissance Philosophy

- 17th/18th Century Philosophy

- 19th Century Philosophy

- 20th Century Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy, Misc

- Philosophical Traditions

- African/Africana Philosophy

- Asian Philosophy

- Continental Philosophy

- European Philosophy

- Philosophy of the Americas

- Philosophical Traditions, Miscellaneous

- Philosophy, Misc

- Philosophy, Introductions and Anthologies

- Philosophy, General Works

- Teaching Philosophy

- Philosophy, Miscellaneous

- Other Academic Areas

- Natural Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Cognitive Sciences

- Formal Sciences

- Arts and Humanities

- Professional Areas

- Other Academic Areas, Misc

- Submit a book or article

- Upload a bibliography

- Personal page tracking

- Archives we track

- Information for publishers

- Introduction

- Submitting to PhilPapers

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Subscriptions

- Editor's Guide

- The Categorization Project

- For Publishers

- For Archive Admins

- PhilPapers Surveys

- Bargain Finder

- About PhilPapers

- Create an account

Welcome to PhilPapers

Results of 2020 PhilPapers Survey posted 2021-11-01 by David Bourget We've now released the results of the 2020 PhilPapers Survey, which surveyed 1785 professional philosophers on their views on 100 philosophical issues. Results are available on the 2020 PhilPapers Survey website and in draft article form in " Philosophers on Philosophy: The 2020 PhilPapers Survey " . Discussion is welcome in the PhilPapers Survey 2020 discussion group .

Philosophical Studies

An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition

- Publishes articles that exemplify clarity and precision.

- Keeps readers informed about central issues and problems in contemporary analytic philosophy.

- Welcomes papers that apply formal techniques to philosophical problems

- Received high marks in a survey in which an overwhelming majority of participants expressed their willingness to publish in the journal again.

- Thomas A. Blackson,

- Jason Kawall,

- Blake Roeber,

- Mona Simion,

- Una Stojnic,

- Natalie Stoljar

- Wayne Davis,

- Jennifer Lackey

Latest issue

Volume 181, Issue 2-3

With "Book Symposium: Mark Schroeder's Reasons First"

Latest articles

Indiscernibility and the grounds of identity.

- Samuel Z. Elgin

Incommensurability and hardness

- Chrisoula Andreou

Vague perception

- Patrick McKee

Instrumental divergence

- J. Dmitri Gallow

Proximal intentions intentionalism

- Victor Tamburini

Journal updates

Author academy: training for authors, journal information.

- Arts & Humanities Citation Index

- Current Contents/Arts and Humanities

- Google Scholar

- MLA International Bibliography

- Mathematical Reviews

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- TD Net Discovery Service

- The Philosopher’s Index

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Springer policies

© Springer Nature B.V.

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Writing Tips Oasis - A website dedicated to helping writers to write and publish books.

17 Top Philosophy Book Publishers

By Madalina Olteanu

If you’ve written a philosophy book and are in need of a publishing house , below we’ve featured 17 top philosophy book publishers for your perusal.

1. Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press was established by Whitney Darrow in 1905 in Princeton, New Jersey. At present, they also have offices in Beijing, China, and in Woodstock, England. After over a century of publishing exceptional books, their purpose has remained that of enriching the knowledge of their audience.

Their backlist includes subjects such as philosophy, sociology, history, mathematics, or education. In terms of philosophy, they are interested in Eastern philosophy, aesthetics, and metaphysics & epistemology, to give some examples. “Philosophies of India”, by Heinrich Robert Zimmer, and “The Sin of Knowledge”, by Theodore Ziolkowski are just two titles worth checking out.

Interested in submitting a proposal? Make sure to read the guidelines first.

2. Rowman & Littlefield

Headquartered in Lanham, Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield have several offices in both the US and the UK. Their backlist is comprised of textbooks, scholarly materials, professional books, and general books.

In terms of subjects, they are interested in philosophy, Slavic studies, linguistics, performing arts, and many more. If you check out their philosophy section, ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics are just a few categories you will find. To become familiar with their preferences, you could read about “Modernity between Wagner and Nietzsche”, by Brayton Polka, or “Revolts in Cultural Critique”, by Rosemarie Buikema.

Luckily, they are open to submissions – you can learn more here .

3. Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press was founded in 1893 in New York, NY. By aiming to promote original research in many important subjects, such as history or economy, the press is constantly expanding the perspectives of their readers.

Philosophy, Asian studies, religion, psychology, business, and science are just a few subjects featured on their backlist. To see what they’re interested in, you could check out “Gender and Finance”, by Brigitte Young, and “Of Time and Lamentation”, by Raymond Tallis.

If you would like to collaborate with them, make sure to send a proposal that includes a short description of your book, a chapter outline, and a market analysis, along with a few other details mentioned here .

4. Duke University Press

Based in Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press was founded in 1921. They add around 140 new titles to their backlist every year, and they provide their readers with digital collections and journals as well.

A few of the many subjects they’re interested in are philosophy, sociology, medicine & health, mathematics, law, and disability studies. “The Wombs of Women”, by Françoise Vergès, and “A Democratic Enlightenment”, by Morton Schoolman are two books that could help you get an idea about their preferences.

If you’re a prospective author, your submission should include your CV, a cover letter, a chapter outline, essay abstracts, and 1-2 sample chapters. If you’re a Duke University Press author, your guidelines are available here .

5. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press

With headquarters in Vancouver, British Columbia, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press was founded in 1967. At present, they have more than 1,500 titles on their backlist.

Their range of interests varies widely, and it includes philosophy & theory, Eastern European literature, Canadian history, art, music, and women’s studies. Two titles worth checking out are “Habermas’s Public Sphere – A Critique”, by Michael Hofmann, and “Aesthetic Ecology of Communication Ethics”, by Özüm Üçok-Sayrak.

To collaborate with them, you can send a proposal that should contain your name, email address, book description, and the reason why it would be a relevant contribution to its field. If they take interest in your project, they will ask you to send the full manuscript. Read more about the guidelines here .

6. Hackett Publishing Company

Hackett Publishing Company was founded in 1972 and it has offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Indianapolis, Indiana.