Famous Still-Life Photographers – The Art of Still-Life Photography

The best still-life photographers present lifeless objects in a charming, imaginative, and striking manner. This skill allows the observer to appreciate the beauty and magnificence of the items depicted in contemporary still-life photography. Modern still-life photography is an art form, but it also has extensive applications in the publishing, printing, and web image industries. In this article, we will explore the most famous still-life photographers responsible for creating the most renowned still-life photographs.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Olivia Parker (1941 – Present)

- 1.2 Paulette Tavormina (1949 – Present)

- 1.3 Jonathan Knowles (c. 1952 – Present)

- 1.4 Laura Letinsky (1962 – Present)

- 1.5 Mat Collishaw (1966 – Present)

- 1.6 Marcel Christ (1969 – Present)

- 1.7 Krista van der Niet (1978 – Present)

- 1.8 Jeroen Luijt (1978 – Present)

- 1.9 Henry Hargreaves (1979 – Present)

- 1.10 Evelyn Bencicova (1992 – Present)

- 2.1 What Influenced Still-Life Photography?

- 2.2 What Techniques Are Involved in Still-Life Photography?

Famous Still-Life Photographers

With contemporary still-life photography, an artist may communicate intellect, creativity, and aesthetic sense more powerfully than with any other photographic presentation, making it one of the most inventive kinds of art. Photographers now have the most effective and creative means of expressing their ideas through modern still-life photography. With the development of technology, the modern still-life photography genre evolved to its current form.

Since its inception, still-life photographs have seen several advancements, from the mobile camera obscura to the modern digital camera.

The most significant subgenre of photography that conveys inanimate subject matter—typically everyday things, whether created by nature or by man—lively and profoundly is still-life photography. Contemporary still-life photography has been greatly influenced by Greek, Roman, and Egyptian still-life art.

Ancient Egyptians decorated their temples and tombs with paintings. With those paintings, they wished to demonstrate their sacrifices to their gods.

The ancient Egyptian still-life artworks first gained popularity in the 15th century BC. Food-related paintings, including those of crops, shellfish, and meat, have also been discovered in old graveyards. In the Tomb of Menna, a noteworthy and ancient Egyptian still-life was found entwined with the particulars of their daily lives. However, contemporary still-life photographs and their actual content are currently considerably different from traditional methods. Both the subject content and the technology are up to date. Let’s check out some of the best still-life photographers.

Olivia Parker (1941 – Present)

| American | |

| 1941 | |

| Boston, Massachusetts | |

| (2018) |

The year 1995 saw the end of Olivia Parker’s view camera images due to a skiing mishap. Due to a broken leg that prevented her from using the darkroom for a year, she dabbled with digital software and PCs. Fine photographs and reliable prints developed as software and equipment advanced.

Parker misses producing silver prints, but using a digital camera in new ways has opened her to new possibilities.

“Using digital gives me complete flexibility to play without having to worry about using film or having a proper camera setup. However, view camera work was a far greater tutor for me in the beginning than digital would have been. It forced me to take my time, study the edges of the images, and evaluate the dynamics of what lies between the boundaries.”

Paulette Tavormina (1949 – Present)

| American | |

| 1949 | |

| Rockville Center, New York | |

| (2008) |

Tavormina became a commercial photographer after relocating to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she attended a course in black and white photography and darkroom technique. She now specializes in old Navajo jewelry and Indian ceramics.

She used her background in food design to operate as a prop and food expert for Hollywood movies including the 1999 feature, “The Astronaut’s Wife” , where she was responsible for designing complex food sequences.

While visiting Santa Fe, Tavormina was exposed to the masterpieces of Old Master still-life artists Maria Sibylla Merian and Giovanna Garzoni as well as the still-life paintings of Sarah McCarty, a Santa Fe-based still-life painter. She frequently frequents one of the city’s several farmers’ markets in quest of ideally imperfect floral subjects for her photography, amidst the bustle that characterizes the city.

Her arrangements frequently evoke the lavish richness of Old Master still-life painters from the 17th century and act as very personal interpretations of ageless, universal tales.

Jonathan Knowles (c. 1952 – Present)

| English | |

| c. 1952 – Present | |

| (2014) | |

| Yorkshire |

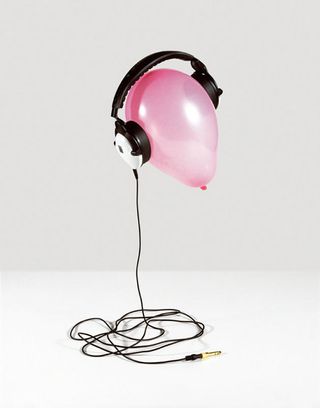

Jonathan Knowles is known for his unique brand of liquid photography. Knowles is a science enthusiast with a very technical approach to image creation. His passion is creating visual communication that seems natural, whether it is macro liquid photography at one extreme or locale lifestyle at the other.

He believes that the beauty of a good picture comes from catching perfect moments on camera rather than relying on extensive post-production processes.

This attitude, along with the fact that he loves advertising, has resonated with the advertising industry. Whether they are working with customers or on personal projects, his attitude is radically different. With clients these days, there are so many stakeholders that everything must be meticulously prepared and agreed upon before the shoot.

He draws inspiration from art, graphic design, music covers, and periodicals, in addition to photography. He also has a large collection of photographic books, which he revisits from time to time at the studio.

Laura Letinsky (1962 – Present)

| American | |

| 1962 | |

| Winnipeg, Canada | |

| (1998) |

Laura Letinsky has focused on the central issue of what precisely qualifies as a photograph throughout her career. Letinsky began his investigation of photography’s link with reality by taking pictures of people, but he soon changed his approach to concentrate almost entirely on objects in the style of still life.

As she experiments with concepts of perception and the transformational powers of the picture, her meticulously constructed compositions frequently center on the leftovers of a dinner or party.

Letinsky utilized tableware, leftover food, and other items like vases or fruit bowls for one of her earlier series of photographs. Letinsky eventually turns this garbage into a subject deserving of study by seeing the images in this series as observations of neglected or forgotten features and leftovers of daily living.

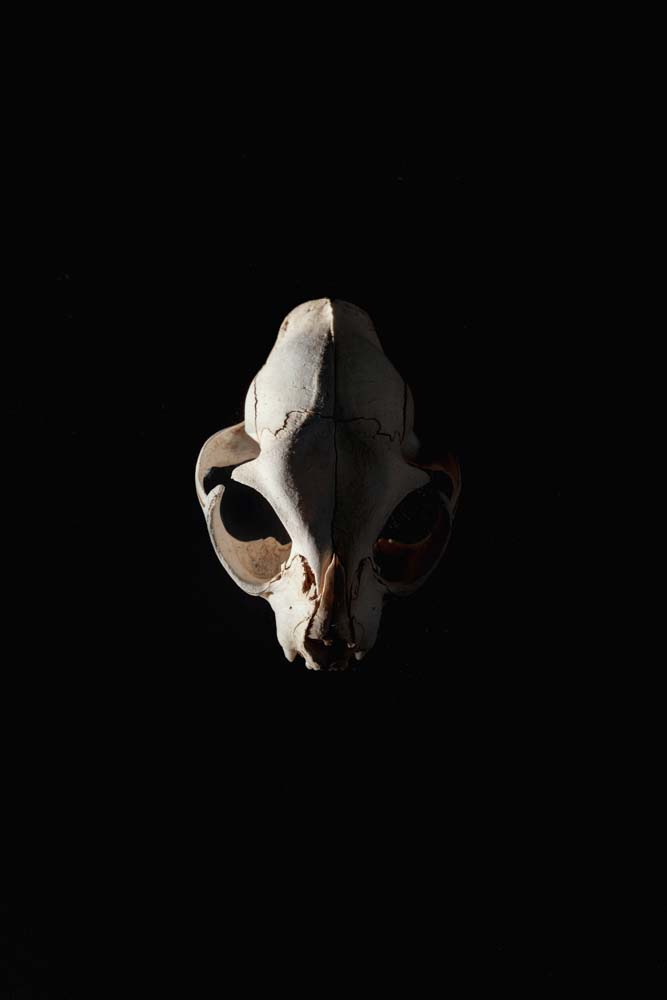

Mat Collishaw (1966 – Present)

| English | |

| 1966 | |

| (2018) | |

| Nottingham, UK |

Photography and video are used in Collishaw’s artwork. The photograph Bullet Hole (1988), which shows what looks to be a bullet hole wound in a person’s scalp, is his best-known piece. Collishaw obtained the original illustration from a pathology textbook, which really depicted an ice-pick wound. In the last thirty years, he has participated in several solo and group exhibits. He attended Goldsmiths College.

His art is frequently upsetting, and it often takes a second glance to fully comprehend what is happening in his pictures.

For the same reason that Collishaw is a good religious artist and a good artist-artist, he is also a fine political artist. He does so because he respects the power of pictures. The abstract escape and the minimalist half-smile are not for him. He wants to strike your mind in the gut. He validates the art of feeling by demonstrating how its intensity may have depth.

Marcel Christ (1969 – Present)

| Dutch | |

| 1969 | |

| (2020) | |

| Amsterdam |

Since Marcel Christ approaches still-life photography in such a distinctive way, his work is among the most identifiable in the field. Christ, who has researched both chemical engineering and photography, combines these two passions to produce his incredibly dynamic artwork. And it is precisely because of this background that he is an especially dynamic and creative photographer and cinematographer who enjoys pushing the limits of the effects and methods he employs. His artwork is the result of his fascination with the surprise and unpredictable nature of the substances he uses, yet in a strict studio atmosphere.

“Controlling coincidence,” he refers to it as. He accomplishes this by using it to give life to inanimate objects and commemorate little periods of time. Nothing in his art is “still.”

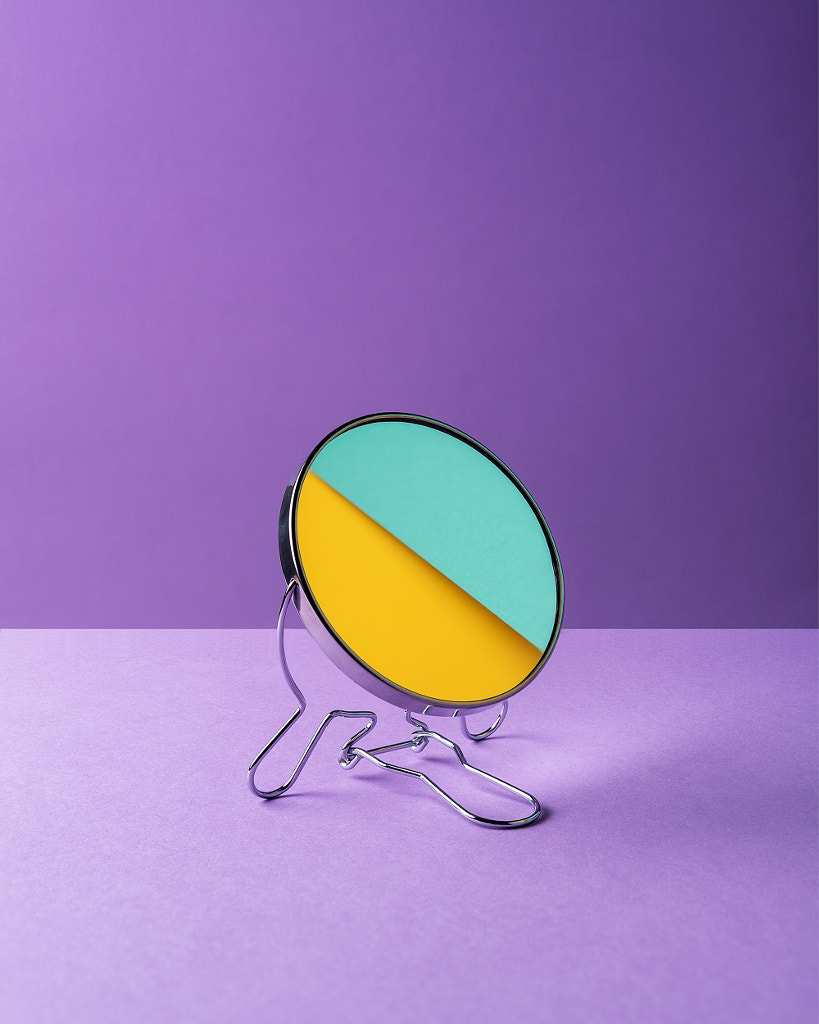

Krista van der Niet (1978 – Present)

| Dutch | |

| 1978 | |

| (2013) | |

| Bathmen, Netherlands |

Dutch-born photographer and academic Krista van der Niet works in both fields. Her photography mostly concentrates on still life, an age-old subject that she intriguingly enriches with humor and modernity. Even in her busiest works, she manages to attain an almost mathematical sense of equilibrium, which makes her work crisp and aesthetically beautiful.

She fascinatingly blends commonplace items and raises them to the level of art, frequently in order to attack media clichés—and occasionally just to make us laugh.

Naturally, van der Niet enjoys creating beautiful images—she can’t prevent herself from making everything look perfectly organized and beautiful. But it also becomes a little monotonous when it’s just about aesthetics. She desired an unsettling undercurrent. She also appreciates comedy in pictures that makes you want to smile.

Jeroen Luijt (1978 – Present)

| Dutch | |

| 1978 | |

| (2020) | |

| Amsterdam |

Jeroen consistently uses the abstract minimalist still life and the traditional still life in his artwork. His wide-ranging interest in painting, particularly the Old Dutch Masters, serves as an influence on his work. Additionally, it concerns both the substance and the aesthetic. The piece must have a specific connotation.

It takes a long time to create a still life, even an abstract piece.

Making the shot may be a labor-intensive task in addition to the idea and all the preparation. The level of post-processing of the photographs follows. As a result, taking a picture occasionally requires more than a week. Jeroen made the proper decision to pursue photography, as evidenced by the numerous awards his work has received.

Henry Hargreaves (1979 – Present)

| New Zealander | |

| 1979 | |

| (date unknown) | |

| New Zealand |

Hargreaves was raised in Christchurch, New Zealand, where he attended preschool through university. He never took photography classes, but it was always a pastime of his. He really went out and brought a camera and started playing to see if he could get this thing to shoot good images when he first started working in fashion in the early 2000s. He wanted to be the one pulling the strings behind the camera.

Despite shooting a wide range of subjects, he has learned many lighting methods and tactics, as well as an appreciation for the importance of balance in a composition.

He produces images that speak to him. Ideas can come from everywhere, but he typically believes he should try to build anything if it makes him laugh or continues popping into his head without being written down. The only obstacle when he makes a decision to act is his own drive.

Evelyn Bencicova (1992 – Present)

| Slovakian | |

| 1992 | |

| (2018) | |

| Bratislava |

Evelyn Bencicova’s effort never quite amounts to what it seems. Her images show well-planned arrangements with artistic sterility and poetic overtones of enduring need and longing. In her “fictions based on fact,” Bencicova creates captivating narrative settings that straddle memory, fantasy, and reality.

She manipulates the viewer’s vision to draw them into the hidden maze of her mind by using multidimensional symbolic representations as illusions.

Her photographs allow for a comprehensive investigation of the ideas that go much beyond what they initially show because of their unsettlingly gorgeous symbolic imagery and washed-out color palette, which are set inside weirdly symbolic situations. In order to create a distinctive aesthetic space where the conceptual and the visual come together, Bencicova’s approach blends academic studies with an interest in modern culture.

That concludes our exploration of famous still-life photographers. The possibility to explore arrangement and lighting, possibly far more than the subject of a still life itself, is one of the most fascinating and difficult features of still-life photographs and the explanation why many of the best still-life photographers are drawn to it. With the subject matter being nearly unlimited, contemporary still-life photography allows the photographer to fully express their creativity.

Take a look at our still-life photographers webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What influenced still-life photography.

The paintings made by the Dutch and Flemish Old Masters of the 17th century contain them frequently and prominently, and we can still see them in the works of still life photographers today. As one of the oldest instances of the genre in European painting, the Golden Age of Dutch and Flemish culture provided and continues to provide a plethora of Vanitas still-lifes, serving as an endless source of inspiration for modern artistic practices and still-life painters of all genres. Each of these pieces of art serves as a reminder to the audience of the fleeting nature of human existence, as well as the meaninglessness of all material possessions and accomplishments.

What Techniques Are Involved in Still-Life Photography?

This type of still life offers a huge area of technical exploration because photography is a medium that primarily depends on light. In the style of the Old Masters, still-life photographers produce the ideal contrast between deep shadows and piercing light that illuminates just particular things. Even though many of them are committed to the creative philosophy behind such a composition as well, their inventiveness is arguably best displayed in the fields of advertising and culinary photography. Given the significance of the Vanitas heritage in these nations and the fact that many of the best still-life photographers are from Belgium and the Netherlands, it should come as no surprise that the concept has also influenced numerous camera artists all over the world.

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Famous Still-Life Photographers – The Art of Still-Life Photography.” Art in Context. July 25, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-still-life-photographers/

Anthony, J. (2022, 25 July). Famous Still-Life Photographers – The Art of Still-Life Photography. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-still-life-photographers/

Anthony, Jordan. “Famous Still-Life Photographers – The Art of Still-Life Photography.” Art in Context , July 25, 2022. https://artincontext.org/famous-still-life-photographers/ .

Similar Posts

Helmut Newton – The Art of Fashion Photography

Famous Fashion Photographers – The Best Model Photographers

Famous German Photographers – Top 10 Well-Known Artists

Jock Sturges – The Controversial Life of the Nude Photographer

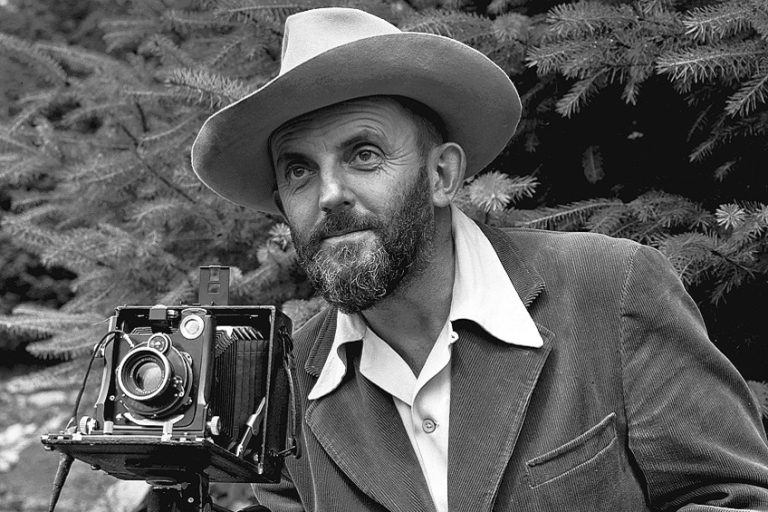

Ansel Adams – A Look at the Life of Photographer Ansel Adams

Francesca Woodman – Discover This Influential Photographer

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Still life: a poetic and photographic reflection

Born as a gender of the Dutch painting of the 16 th century, still life served to both a merely decorative taste and the need of deep reflections about the ephemerality of the human presence in the world. While vanitas had as a function to recollect that pleasures and appearances are ephemeral; while memento mori induced to reflection about life and death, reaching in both the forms and the allegorical character. Since the early days of photography, the model is the painting, and the theme of still life appears both in classics like Talbot and Bayard, and in modern Rodchenko and Cartier-Bresson. In the Brazilian modernist poetry, the reading of " Maçã " , by Manuel Bandeira, has already become classical as a cubist still life. Our work aims to investigate settings that the theme finds in the contemporary poetry of Paulo Henriques Brito and Ana Martins Marques, as well as in photographs of Robert Frank and Francesca Woodmann and in a video of Sam Taylor Wood, enhancing its indexical, allegorical and narrative character.

Related Papers

"Writing and Seeing"

Maria de Fatima Lambert

This exhibition seeks to advance towards a space of continuity. The authors presented are emblematic, are historical, and they contemplate some of the dimensions of plasticity inscribed into the perspective of Looks and Writings. They do not, however, represent an exhaustive survey of all the important names that stand out in the historiography of Portuguese art, which is why there is a pressing need for future events to complement this first showing. The history of Portuguese art in the 20th century may also be constructed by focusing upon the inter-relationship between the image and writing, a persistent and relevant trend that has involved authors of unquestionable talent, and has accompanied the general development of poetry and literature and the performing arts. At the beginning of that century, the most representative and high-profile case in Portugal (though achieving recognition only belatedly) was Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, who made use of fragments of writing in his compositions, giving them a privileged place in keeping with the languages of synthetic cubism, futurism and Dadaism, which were at that time emerging (definitively). As was the case with other unquenchable artists, the very act of integrating external elements into his painting led to an expansion into new combinations, revealing an overlapping relatedness peopled by words from his private hoard, chosen for their creative and provocative seductiveness.

Monteiro, Mario do Rosario, Ming Kong, Mario S., & Pereira Neto, Maria Joao (eds.): Time and Space, CRC Press/Balkema (Taylor & Francis Group), 277-282.

Gizela Horvath

Painting is a spatial medium, and therefore the representation of time is a challenge for it. We can only conceptualize time through change, and the representation of change is not an easy task in the still, unmoving genre of painting. This text narrows the visual representation of time to the time of living beings: the visual representation of the passing of life. From the Renaissance onwards, special types of painting were dedicated to this theme: the memento mori, the vanitas, and the still life, which is (also) about the passing of time. In contemporary art, still lifes have lost the symbolism that refers to ideas of passing, of finitude. If still life does carry such a message (such as Andy Warhol's Flowers series), the reflection on the passage of time is expressed more abstractly in the language of the mathematical sublime as Immanuel Kant theorized it in the Critique of the Power of Judgment. This paper argues that, alongside memento mori and vanitas paintings, the still life also essentially directs our attention to the passage of time and expresses this message either through symbolic means, in the language of the beautiful, or through quantitative means, in the language of the sublime.

Communication presented at the MODERNIST EMOTIONS 2nd International Conference of the Société d’Etudes Modernistes - 22nd-24th June 2016, Paris Ouest Nanterre University.

Brazilian first wave of Modernist Art discussed among other issues the elaboration of a modern image for Brazil. This subject is present in 1920’s modernist painters like Tarsila do Amaral, Anita Malfatti and Candido Portinari who give face to African Brazilians in an attempt to elaborate a realistic representation of modern Brazilian society. It is quite productive to contrast those famous Brazilian painters to the production of Lithuania born painter Lasar Segall (1891-1957) and the poetry of Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902-1987) in works like “Alguma Poesia” (1930). Even tough preserving the general sense of modern poetry as defended by Mario de Andrade, which saw it in terms of objective depiction of reality, Drummond presents us poetic subjects that tell about the world never completely separating their views from the creator himself. As much as enlarging the context of Brazilian modernism in terms of a realism like that embraced by Segall, Drummond presents us poetry as something elaborated through movement. A perpetual motion that unfolds the gaze of the poet to his inner self, as much as its does depict his views on the world around. From a nationalistic modernist attempt to give face to the nation, Drummond unfolds the images of self through the poetic movement where looking and imagining, speaking about the Other as much and about the self elaborates a far more complicated modernist notion, one that is closer to the drawings of Seggal than to the idealised manners of the 20’s. If other modernist attempts were to detach themselves from the self, Brazilian modernist movement elaborates in Segall’s and Drummond’s painting and poetry an intricate discussion about the limits between I and the world as much as the limits between seeing, feeling and thinking. Presented at the MODERNIST EMOTIONS 2nd International Conference of the Société d’Etudes Modernistes - 22nd-24th June 2016, Paris Ouest Nanterre University.

Messias Basques

Iryna Shkola

The article deals with one of the urgent problems of modern literature genealogy – the transformation of genres, which is quite significant especially within the context of intermedial interaction between two arts – literature and painting. The transformation of the genre of still life, starting with painting and continuing in literature, is in the focus of the current scientific research. It is mentioned that the evolution of still life painting from flower framing Madonna in the 15 th – 16 th centuries, through raising in the works of Dutch and Flemish artists in the 17 th – 18 th centuries, till Impressionism view on depicting the objects has been changing the understanding of the term itself. The diversity of the meaning of still life as a term of painting genre was caused by different interpretations of the Dutch term “stilleven” in national arts and artistic epochs. This issue is also important to discover whereas to understand the author’s interpretation of a literary work th...

Lucy Somers

A short essay using Plato's theory of Mimesis to examine how far removed viewers are from the artist's statement in a few key examples; focusing on the still life and participatory art events.

PORTO ARTE: Revista de Artes Visuais

Francisco Dalcol

Arte, Individuo y Sociedad

Teresa Lousa

Smarthistory.org

Carmen Ripollés

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Educação & Realidade

Margarete Axt

Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas

Tadeu Chiarelli

Gisele Wolkoff

Revista de Literatura, História e Memória

Susana Viegas

Journal of Art & Design Education

Max Kandhola

Still Life, Landscape and Portrait. The Genres of Painting in Contemporary Art. Argentina and Latin America (Introduction)

Natalia Y Giglietti

Joana Brites , Marta Barbosa Ribeiro

Margarida Barbosa Leão

Botannica Tirannica

Ilana Feldman

Delfim Sardo

ARJ – Art Research Journal / Revista de Pesquisa em Artes

Matteo Bonfitto

Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem

Adriana Mazziero

Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 13(1), 80-86.

Bruno Marques

1 st International e-Conference on Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences

Vanessa Deister

Mistral | Journal of Latin American Women's Intellectual & Cultural History

Maria Emilia Fernandez

CORVINUS JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL POLICY

Julián David Romero Torres

michele louise schiocchet

Susana Lourenço Marques

Cristina Freire

Anna Viola Sborgi

European Journal of Fine and Visual Arts

Paulo Alexandre e Castro

Mengzhong Zhao

Ilha do Desterro A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies

Eliane Campello

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

10 Incredible still life photographers

Complete guide to still life photography – plus 10 contemporary still life photographers that need to be on your radar.

Still life photography, like any photographic discipline takes immense skill. A major benefit however of working with still life or miniature, is that you can try out lighting styles and techniques in a diorama, honing you abilities and adding depth to your knowledge – before taking your ideas to set.

You’ve tested your ideas, and you already know if they’ll work or not. Stanley Kubrick was well known for this, he’d make the entire scene in miniature and then take a 10×8 Polaroid to see if it came out on film how he wanted. A big win is of course it will save you loads of money on gear, don’t bother spending thousands on new lighting rigs, flags and diffusers, simply make them up in miniature and play around with materials you have at home so you can better understand their properties and how they’ll affect light…then scale them up!

In still life photography, the photographer has complete control over the scene. This means that they can take the time to set up the shot exactly as they want it, and then take their time taking the photo. This allows for a lot of experimentation, and gives the photographer a chance to really perfect their craft.

I thoroughly recommend in the first instance to find a still life photographer who’s work you really like and then try to imitate it. You’ll learn a lot, and fast. It’s the quickest way to mastery as you’ll appreciate how light interacts with different surfaces and textures and how different light sources interact with different objects.

Take this seemingly very simple shot by Ashraful Arefin. It’s emotive, artistic and beautifully composed. Better yet, it makes use of objects that can either be found at home, or found outside, all for free. A broken mug, some blossom from a tree and a setting sun to create the orange light in the background. From recreating this simple shot you’ll understand more about lighting, colour theory, composition, story telling, bokeh, depth of field and freezing motion. All for free. Still life photography takes practice and dedication, but the rewards and depth of understanding you’ll receive from undertaking a still life project will far outweigh the effort it takes to set up, plus, it’s alot of fun.

Still life photography can be literally anything. Food, toys, books, office supplies, you name it. The only limiting factor is your imagination. Take a branch of cherry blossom in the spring, place it in a jug by a window with a clean background, boom, looks just like a Cezanne. Fruits, jugs, soft furnishings and flowers are the traditional inanimate objects of choice of the great painters, but hopefully you’ll see from this article that anything can be made into a really cool still life image.

Most people are familiar with still life paintings, which often feature an arrangement of inanimate objects such as flowers, fruit, or books. While still life paintings may appear to be simple, they can actually be quite complex and challenging to create. In order to capture the essence of an object, the artist must have a keen eye for detail. They must also be able to create a sense of depth and perspective, using light and shadow to create a three-dimensional effect. The best still life paintings are those that not only accurately depict the subject matter, but also convey the artist’s unique vision and interpretation. As with any type of painting, the artist’s skill, talent, and imagination are key factors in creating a successful still life painting. The exact same principles apply to photography. Something to consider is that still life composition has been extensively covered by the master painters of the last one hundred years, so there’s a great deal to be gleaned from studying painters as well as photographers. Look at Paul Cezanne, Pieter Claesz, Caravaggio and of course Van Gogh for inspiration.

If you’re conducting more thorough research, the Dutch masters are certainly worth investigating. Dutch still life painting reached its peak in the 17th century, a period coinciding with the Dutch Golden Age. This was a time of great prosperity for the Netherlands, and art was part of the country’s cultural flowering. The paintings were typically small and intimate, often featuring simple arrangements of everyday objects such as flowers, fruit, glasses, and plates. What set Dutch still life’s apart from those of other countries was the level of realism achieved by the artists. They used a technique known as “trompe l’oeil,” which employs subtle gradations of light and shadow to create an illusion of three-dimensional depth. This allowed them to achieve a level of realism that was uncanny for its time. Thanks to the skill of these artists, Dutch still life painting remains some of the most highly prized in the world.

So if you’re looking to get started in still life photography, this article is the complete guide you need to master skills, tips, lighting, and lens needed in creating stunning still life shots.

Table of Contents

- What is Still Life Photography

Types of Still Life Photography

- Equipment Required for Still Life Photography

- Still Life Photography Ideas – The Best Contemporary Still Life Photographers

What is Still Life Photography?

Still life photography is a form of photography and a work of art focusing on everyday or commonplace inanimate objects. Anything that’s still basically…because, still life…even though the thing might be dead, like a bug. But ‘Still Dead’ might be confusing for some people.. would be a cool play on words for a project idea though!

These objects can literally be anything but more often than not are objects found in nature or in the home that have some inherent beauty, think flowers, fruit, rocks or jugs, soft furnishings and table settings.

Constructing an engaging still life takes great sill and patience. You have to be willing to experiment as you won’t get it right first time.

The principal idea of still life photography isn’t just to create a beautiful scene, it’s to examine the relationship between objects.

Of course you can just photograph one object on it’s own, but then the relationship is with the negative space around it, rather than with another object.

Still life photography is one of the most common types of photography used and prevalent on social media, often referred to as ‘lay-flats’.

There are tons of still-life images across the internet and on websites, billboards, and TV advertisements.

Most people have taken still life photographs before but not really paid a great deal of attention to it. Each time you capture places you’ve been, things you’ve done, or even meals you made, you’re taking still life photographs with your mobile phone. Only in the context that we are exploring, it’s executed with greater intent and much more control over the subject, it’s setting and how it’s lit. The most common types of still life photography are:

#1. Food Photography

Food photography is a kind of still-life photography that features all kinds of food, from fully cooked meals to raw produce.

Typically people aren’t included in these shots as the intention is to show off the produce. Either for the purpose of selling a product, or for selling individual produce. Whilst including people in the still life isn’t the norm, this only means there’s room for the genre to grow, why not experiment with it in your own work?

Consider alternatives to producing beautiful shots of food as well, why not explore the dark side? Food rots, this could make for an interesting project. The scene would no longer depict abundance, but decay and death.

Or check out Klaus Pichler’s still life photographs of rotting fruit

Product photography falls into commercial photography categories. Here, you showcase a product to sell it.

These images are typically much more beautiful as opposed to the above which is more conceptual, the intention is purely to drive sales rather than to adorn the walls of a gallery.

#3. Table-top Photography

Table-top photography is another category of still life photography that focuses on arranging objects in an aesthetically pleasing manor on top of a table.

Tables add structure and solid geometric shapes to your composition, this then allows you to add softer elements such as fruits and flowers and immediately have contrast in texture, colour, shape and form.

It is one of the most common still life photography styles, and it is the easiest to pull off.

#4. Flower Photography

Flower photography is a classic and unique type of still life photography with flowers as the subject of the photographs.

You’ll often find still life photographers arranging beautiful bouquets or petals neatly and creatively.

#5. Black and White Photography

Black and white photography captures still life images but switches from colour to grayscale.

This is one form of still life photography that photographers can use to improve their still life photography skills.

Black and white still life photography captures objects in a black and white, it carries a different mood that photographers can leverage for creative vision.

#6. Flat-lay Photography

Flat-lay in flat-lay photography refers to the angle of view and doesn’t necessarily refer to the subject.

Shooting the perfect flat-lay still life photography requires the sensor to be kept parallel to the surface where you have your subject.

Flat-lay has become an increasingly trendy type of photography on social networks like Instagram, with still life photographers from around the world uploading some amazing shots.

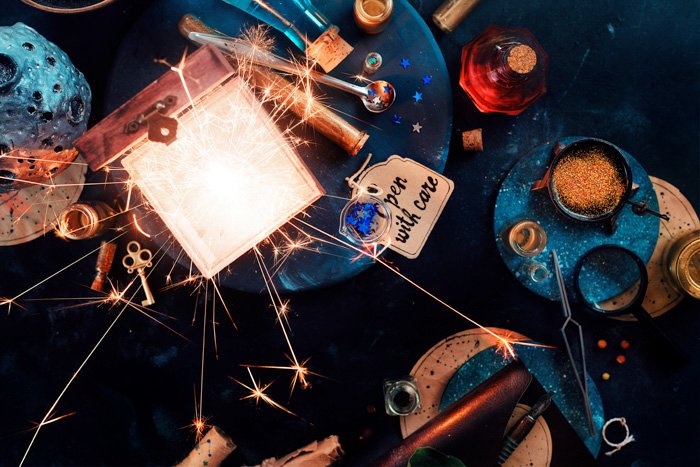

#7. Concept Photography

With concept photography, still life photographers use objects to represent things beyond what they are.

Concept Photography may appear strange or unusual and might be difficult to decipher at first glance, but they convey a deeper meaning and are captured in a way that drives home that meaning.

The below image for example.

The light above the hands looks like light when it reflects off of water in a swimming pool wall. The hands reaching up to the light, are we to believe the subject is drowning? But there is no water? Metaphorically drowning? In what? Conceptual work should leave the image open to interpretation and invite questions.

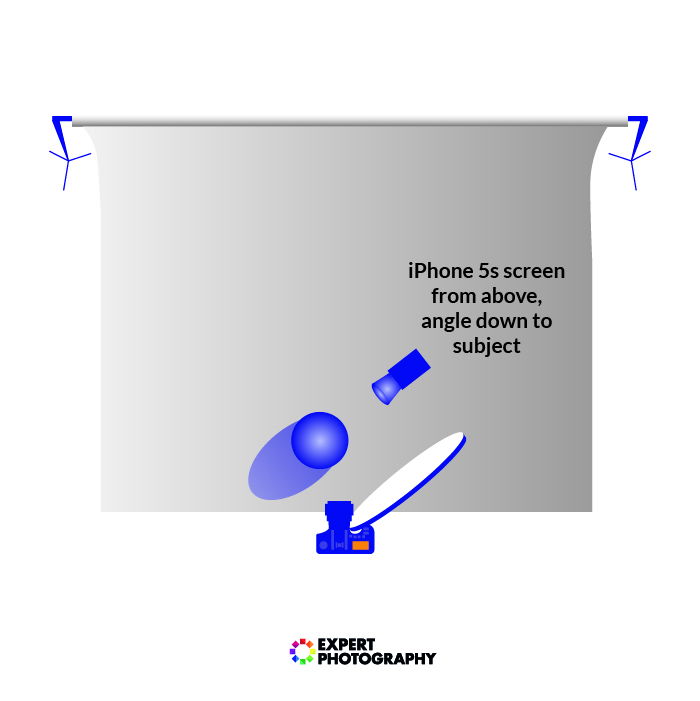

#8. Toy Photography

Toy Photography is a fun way of recreating iconic scenes and depicting real-life events while exploring the use of additional light sources in still life photography.

Toy photography can be incredibly fun as you can place toys completely out of context to create a new narrative.

Toy photography is excellent for another reason, and that’s because you can test different light sources on miniature people to see if they work before you head out to a portrait shoot with a real person. A great way to be creative on a budget and explore new ideas.

Equipment required for Still Life Photography

In still life photography, there are no rules or regulations made on concrete concerning the equipment to use.

Part of the fun is the challenge of coming up with new and exciting combos to make things work perfectly. Generally, below are some pieces of equipment you will need:

Yes, obvious I know. From large-format film camera to smartphone camera, it doesn’t matter which you use.

Any camera is fine to take still life photographs with, it depends more on what you need the final shot to look like.

But as a rule of thumb, if you’re needing to print it big for an advert, or it needs to be high resolution for a cook book say, then you’ll want a high end DSLR more than likely.

Lenses are also another important piece of equipment for shooting still life photography, and the prime 50 mm lens is the classic choice.

The prime 50 mm lens is inexpensive and offers a realistic image without distortion on a full-frame camera.

The 50mm is dependable and largely mimics how the human eye sees the world, so it’s a great way to place the audience in the scene. The higher the lens number in mm the more it will compress perspective, which is great if you have a starter lens that can’t shoot at wide apertures. You can get around this to a degree by using a longer focal length in mm, the longer the lens, the more exaggerated the depth of field becomes.

#3. Lighting

Lighting is another piece of equipment you need in still life photography, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be conventional.

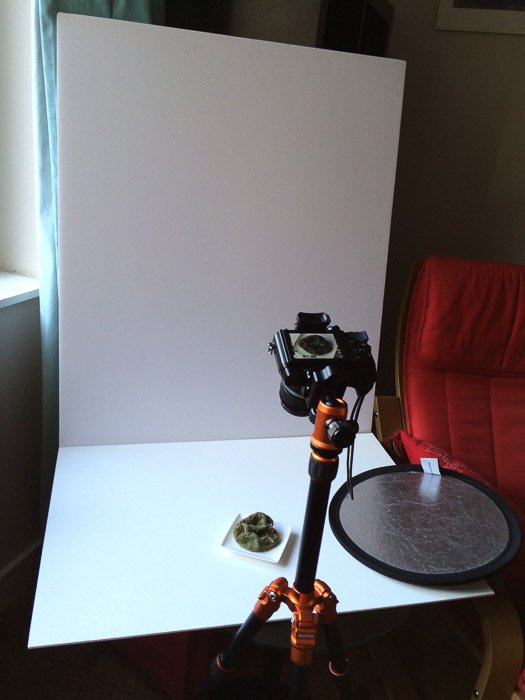

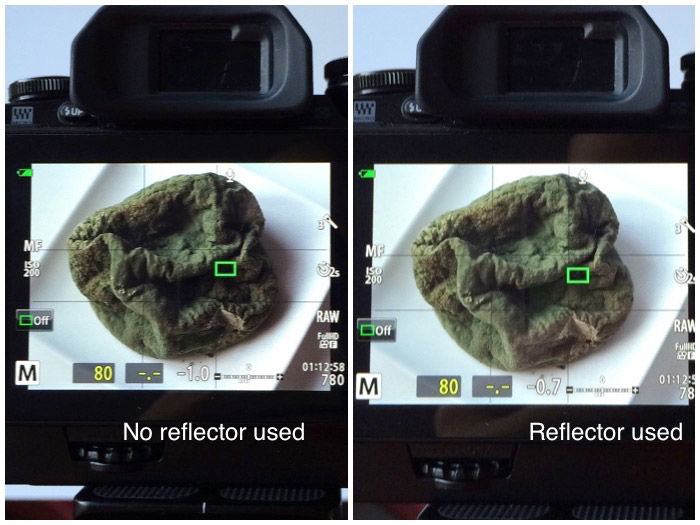

In addition to flashes and speed lights, you can harness the beauty of natural light for your compositions. Photographers who decide to go with natural light rely on diffusers and reflectors. If you don’t have these, don’t forget you’re playing in miniature, so simply use a white pillowcase, piece of plain paper or even some tin foil.

Coloured reflectors can bring warmth and liveliness to a still life photograph and help the composition by adding particular tones and colours. Again, don’t overthink it, use coloured A4 card.

Diffusers and strobes are additional lighting tools but avoid on-camera lighting that produces a straight-on flash. Its effect is usually harsh and will make your composition look flat.

Always light from the side, never from straight on.

Use a desk lamp if you’re looking for cheap alternative for lighting.

Using a lightbox is also a great alternative and gives you a clean white background to work with.

The tripod is another useful tool for creating great still life imagery. It’s easier to take shots with the camera in a fixed location as you can tweak the setup of your objects without upsetting your overall composition.

A tripod makes this possible when you set up the camera and frame your image while rearranging background and photo subjects.

#5. Image Editing Software

Images straight out of the camera typically look a bit rubbish.

If you don’t have Photoshop or Lightroom no problem, there are plenty of great editing apps you can get on your phone completely free, I’m doing a round up post on these soon.

#6. Backgrounds

You also need backgrounds and surfaces to enhance your subject and make your shots engaging.

Canvas, wood, bedsheets, whatever you can think of. If you place it far enough in the background it won’t be in focus anyway.

#7. A Spirit level

This is invaluable when you’re shooting lay flats.

They are much more complicated to rig up, but if you have a spirit level you can gauge if you are taking your picture parallel to the subject. Getting your lay flats actually flat will make the look a lot better.

Still Life Photography Ideas – 10 contemporary photographers

Without further ado, here are twelve still life photographers that will hopefully inspire you to create a still life of your own.

Hardi Saputra

Surreal, dreamlike and full of whimsy, Hardi Saputra makes creating beautiful, creative still life photographs look easy. I’m keen to draw attention to his work and to list him first in this article because he embraces the idea of utilising what is around him. Yes his scenes are dreamlike, but everything he uses to create his scenes either exists in a typical household or is very cheap to acquire. Take the scene below for example, a child’s toy giraffe, some cotton wool, coloured paper, some string and some ping pong balls, a bit of fiddling with some glue, and you’ve got a picture. Don’t overthink your work or get stuck thinking that you need to spend money to make a cool scene. Use your imagination and make use of all sorts of scraps lying around. For scale, Hardi has said in interviews that he uses a 40cm square box to make his miniature scenes. This should help give you an idea of how you can create beauty on a small scale. He also stated that he started his photographic journey using an Android phone to take pictures. The quality of modern phone cameras is immense, pair it with a few desk lamps and a cardboard box, and you’ve got yourself a mini studio.

“My inspiration comes from my dreams. I always want to see a beautiful field of grass, beautiful clouds, and the stars. Instead of just imagining them, I decided to turn them into artwork. I also get inspiration from video games. The rocket was inspired by the Red Rocket station from Fallout games. I chose soft fabric materials and cute astronauts because I love playing a video game called LittleBigPlanet. The other sources of my inspiration are cartoons and anime. Most of them have unique and beautiful stories, skies and colours, especially the anime from Studio Ghibli because their clouds are so pretty.”

Henry Hargreaves

Henry makes this list because he takes information that is widely available and turns it into conceptual art. The contents of inmates last meals is only a Wikipedia search away, all you need is an idea and a bit of imagination and you’ve got yourself a really cool still life photography project. Exploring difficult topics like the last meal is also a really interesting intellectual exercise and is a great way to expand the creation of new ideas for you own, original pieces. Food is a universal language, each of us needing to eat, but having many different preferences. It allows you to connect with people on a deeper level by exploring what they eat, you could even embark upon a project that explores identity through food, can a picture of food be a portrait of a person? It opens up a whole new world for you to explore and develop ideas. Henry mentions on his website that he thoroughly enjoys collaborating on his projects, which is an excellent idea when trying to create your own still life pieces. Not only is it always handy to have a second person around for company and to challenge your ideas, but inevitably when setting up lights and dealing with small details, it’s always handy to have someone with you to help. You can then also help them with their project and learn from their mistakes too, so you both learn faster.

“In my photography I have always been fascinated by the mix of the mundane and the extraordinary. So I while was reading about efforts to stop the Last Meal tradition in Texas it sparked my interest. In the most unnatural moment there is (state sponsored death) what kind of requests for food had been made?”

There is a great deal to be discovered in Anna’s incredibly beautiful still life photographs. She combines the toolkit of the great still life painters and brings it up to date with the use of the camera. Extreme depth of field, texture and minimalist composition all combine to make truly stunning images. Notice how Anna uses colour in her work. It’s extremely important when trying to master composition that you factor in colour when putting together these images. In the image directly below, the cloth is the same colour as the flowers, the jug and bowl in the background also have accents of pink that help balance the image. The deliberately picked petals at the bottom of the frame help draw the eye to the bottom of the frame and the background also has accents of pink, and the complimentary colour blue. See if you can gather objects from home to make a scene like this at home using your dining table or a block of wood. To get the painterly effect, you’ll need to add a texture layer in photoshop or using a phone app. Try the Mextures iphone app.

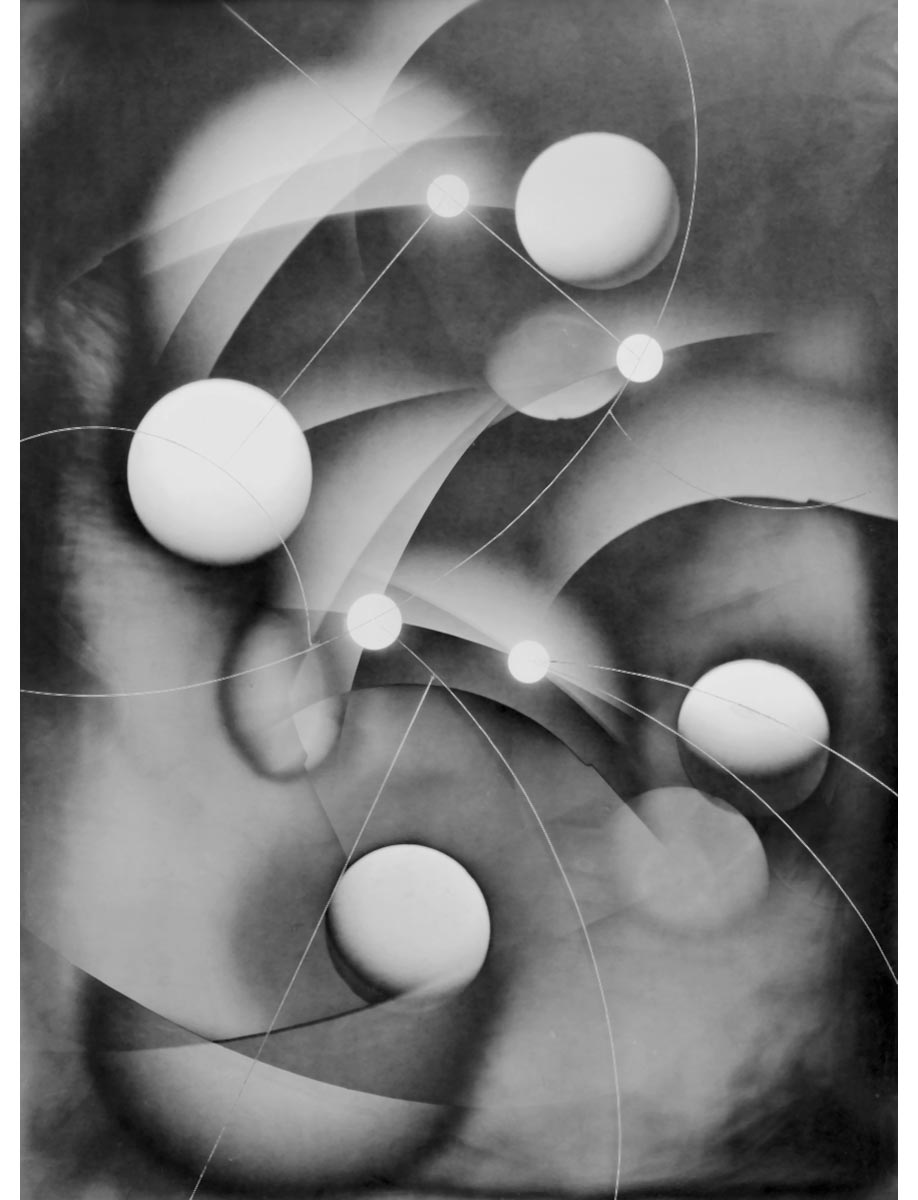

Michael Jackson

This one is a bit of a cheat as Jackson creates his still life images in the dark room rather than by setting up objects and photographing them. He is the only person in the world (to my knowledge) that creates these images known as Luminograms. A combination of different light sources, modifiers and bits of glass combine to make something that is truly extraordinary and entirely unique. Most photography students (I hope) will have access to a dark room, but even if you don’t just wait until night time, turn off all the lights and you’ll be able to play with a torch, some tubes and black and white darkroom paper. See if you can crack the code and work out how he does it!

I have a suspicion that he uses something like a Pringles tube and presses it firmly against the paper and then shines a light into it at an angle. The shadow of the edge of the tube would then create the 3D ball illusion. This may be well off, but it’s my guess. I think the straight lines are either created with a resist (something like a pencil and then washed off afterwards), or scored into the paper

Paulette Tavormina

Paulette Tavormina is one of the most celebrated photographers of still life scenes, with her stunning and intricate images of everyday objects revolutionizing the genre. Born in Pittsburgh, PA, Paulette first discovered her passion for photography at a young age. Although she initially envisioned a career behind the camera, she soon found herself drawn instead to art direction and design. After earning a degree from Parsons School of Design in New York City, she went on to work as a set designer for theatre productions across the United States. It was during this time that she developed an interest in still life photography.

Paulette’s unique style stems from her love of crafting intricate compositions out of ordinary objects. She creates lush scenes that incorporate everything from flowers and fruit to toys and trinkets. Her carefully arranged scenes are brought to life by her use of vivid colours and rich textures, resulting in photographs that are at once beautiful and intriguing. Over the years, Paulette has built up an impressive body of work that has earned her critical acclaim both domestically and internationally. Today, she is considered one of the top photographers working in the still life field.

To create your own work in her style, collect fresh flowers and place them on black card. Don’t immediately spend money on fresh flowers, you can make plenty of interesting compositions out common flowers such as Dandelions, field daisies and Sweet Cicely. Then you’ll need a single direction light source, use a room with only one window for ease.

Jeroen Luijt

Still life photographer Jeroen Luijt was born in Holland in 1966. After studying art and design at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague, he began his career as a commercial photographer. However, it wasn’t until he turned his camera towards still life that he found his true calling. Luijt’s work is characterized by a strong use of light and shadow, as well as a keen eye for detail. His focus on simple objects—a cup, a vase, a book—has resulted in some truly stunning images. In recent years, Luijt has also begun to experiment with virtual reality, creating immersive experiences that allow viewers to explore his photographs in new ways. Whether he’s working in traditional photography or pushing the boundaries of technology, Jeroen Luijt continues to produce extraordinary work that highlights the beauty of the everyday.

Laura Letinsky

Laura Letinsky is a renowned photographer who is best known for her stunningly detailed and graceful still life photographs. Born in Chicago in 1959, she was initially drawn to the medium of photography from a young age, using her high school darkroom to explore the possibilities of this new art form. After graduating from college with a degree in art history and religion, she decided to pursue her passion for photography professionally, studying at the San Francisco Art Institute before going on to complete an MFA at Yale University.

Letinsky’s work has been widely recognized and celebrated, with over 45 exhibitions and projects spanning countries around the world. Her style involves a careful and meticulous approach that focuses on capturing small details – an object here or a hand gesture there – within larger settings. She is famous for exploring themes such as domesticity and human relationships through intricate visual compositions that draw the viewer in. Her skilful use of light reveals beauty in even unexpected or mundane subjects, highlighting their textures, colours, and subtle interactions amongst one another.

Today, Letinsky continues to explore new topics within her artwork while teaching photography at various universities across North America. Her lifelong dedication to exploring both aesthetics and ideas through the lens have resulted in some truly stunning photographic creations that both inspire and challenge the viewer.

“In giving ourselves over to our sense of vision, it’s as if we’re saying it’s the only sense that matters.”

Olivia Parker

Born in 1938 in Pasadena, California, Olivia Parker was a self-taught photographer with a passion for capturing beauty through the lens of her camera. Her career began in the 1960s, when she shot a series of photographs depicting everyday objects and landscapes that were featured in titles such as Look, Harper’s Bazaar, and Town & Country. However, Parker quickly developed a unique style that set her apart from other photographers working at the time. While many others relied on vogue clothing and architecture to create dramatic visual compositions, Parker preferred simpler subject matter like fruit or bread. She often arranged these objects into still life’s on table top surfaces, drawing attention to the surfaces themselves rather than to any surrounding scenery. This approach helped to revolutionize the field of still life photography and has influenced countless artists since. Today, Olivia Parker remains one of the most celebrated names in this genre of art, with numerous exhibitions around the world and a legacy that continues to inspire new generations of photographers.

Born in Tel Aviv, Israel, in 1967, Ori Gersht is one of the world’s most prominent imaging artists. His distinctive style blends documentary photography with painterly imagery, exploring themes of death, war, and environmental destruction.

Ori first discovered his passion for photography as a teenager, when he began documenting newspaper announcements about political conflicts in Europe at the end of the Cold War. These images would eventually serve as inspiration for his signature hybrid style of still life photography.

Throughout his career, Ori has travelled all over the world to capture spectacular images at breath-taking locations such as Chernobyl and Oslo’s Vinderen Cemetery. He uses sophisticated equipment to freeze moments of intense emotion or tension that play out almost too quickly to see. Whether capturing fragments of exploded vintage porcelain shattered by air gun pellets or a bulldozer working its way through a layer of rime ice on top of crevices filled with icicles and snow crystals, Ori’s work offers complex layers of symbolism and beautiful visual contrast.

Despite the power and intensity of his photos, Ori manages to convey a sense of serenity in each image that belies their often devastating subject matter. His unique blend of intense emotion and meditative calm has made him one of the most celebrated still life photographers of his generation.

Margriet Smulders

Still life photographer Margriet Smulders is best known for her highly stylized and meticulously composed images. Born in the Netherlands in 1958, Smulders began her career as a fashion photographer before turning her attention to still life’s. Working in both digital and film mediums, she often combines traditional photography techniques with digital post-processing to create her signature look. Her work is characterized by a careful attention to detail, whether she is photographing a simple floral arrangement or a elaborate tableau. In recent years, Smulders has also begun experimenting with incorporating found objects and nature into her still life’s, creating unique and evocative images that are as much about the process of creating them as they are about the final product. no matter what the subject matter, Smulders’ photos always exude a sense of calm and beauty.

Creating beautiful and successful still life images is an impressive feat, and as you can see from the images above, has incredible scope for you to apply your creativity and imagination to in order to develop and explore your own ideas.

It doesn’t matter your creative vision or artistic goals. Still life photography is a fantastic place to start and a different type of photography worth trying.

Still Life Photography: The Ultimate Guide (+ 9 Tips)

A Post By: Lea Hawkins

Ever looked at a simple fruit bowl and wondered if it could be something more? Well, it can! Still life photography is all about transforming ordinary objects into visual art, and it comes with an array of powerful advantages:

- It’s highly accessible (you can do it in your own home!)

- It doesn’t require ultra-expensive gear

- It’s not nearly as hard as it might seem

I’ve been taking still life images for years, and in this article, I offer everything you need to improve your shots. I cover all the key elements including lighting, composition, and editing – so that, no matter your level of experience, you’ll be ready to shoot some amazing still life photos of your own.

Let’s get started.

What is still life photography?

Still life photography is an art form that involves capturing inanimate objects. This can include anything from a bowl of fruit to a carefully arranged collection of antique tools.

The appeal of still life photography lies in its accessibility and its potential for immense creativity. With complete control over all elements, from lighting to composition, you can turn ordinary objects into something extraordinary.

Seeing everyday objects through an artistic eye is the essence of still life photography. It’s about finding beauty in the mundane and ordinary. Whether you’re a professional photographer or just starting, still life photography invites you to see the world anew, and it’s a wonderful way to explore your creativity!

Essential still life photography gear

You don’t need to spend a fortune to get started with still life photography. An entry-level mirrorless camera or DSLR will work just fine. These camera types provide more control and flexibility compared to simple point-and-shoot models. Paired with a close-focusing lens , they allow you to capture sharp images of your subjects that you can edit, print, and hang on your wall.

A tripod is another important item, and while not every still life photographer works exclusively with a tripod, it’s a great piece of equipment to obtain. Even a slight camera movement can change the focus and composition, so a tripod will help streamline your workflow. More importantly, it’ll keep your camera steady, which is crucial for achieving clear, sharp images in low light conditions.

Other useful accessories include reflectors to reduce shadows and diffusers to handle too-harsh lighting.

That said, you don’t need to go gear-crazy; the key is to understand that quality images don’t necessarily come from expensive gear. With the right basic tools, beautiful still life images are entirely within your reach.

Key still life photography settings

Manual mode is where you want to begin in still life photography. Working in this mode gives you ultimate control over your image, allowing you to fine-tune the aperture, ISO, and shutter speed. With control over these settings, your creativity can truly shine.

A narrow aperture such as f/8 is a standard choice for still life photography. It keeps the subject in focus, giving you the crisp details that’ll make your still life images stand out. As for the ISO: Keep it low to maintain the best image quality. As long as you’re using a tripod, shutter speed is less critical; you can slow it down without causing blur.

Understanding these settings is essential to achieving professional-looking photos. While dialing in apertures, ISOs, and shutter speeds may seem technical at first, you’ll find that it quickly becomes second nature!

Basic lighting for still life photography

Light is an essential component of still life photography , and many still lifes feature beautiful lighting arrangements (which often create moody, painterly effects).

But it’s important to realize that you don’t need fancy lighting to create a stunning still life . When you’re starting out, I recommend using whatever light you have available, such as:

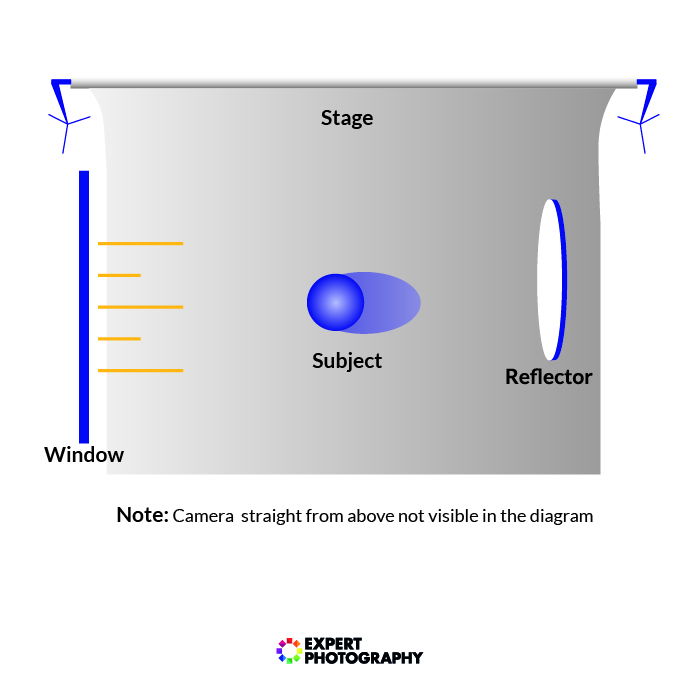

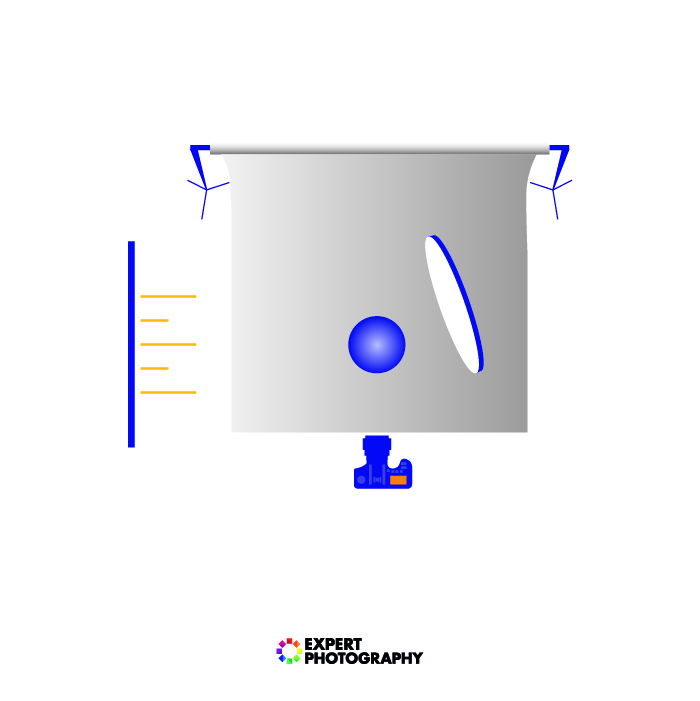

- Indirect light from a window

- A flashlight

Don’t just create your setup, take one shot, and call it a day. Instead, try out different lighting effects! Use a curtain to block out some window light, then remove the curtain to let the light stream in. Shine a flashlight at your main subject, then try a second shot where the flashlight is positioned off to the side and shrouds your subjects in shadow. Make sense?

Note that, if you’re using lamps, flashlights, or candles, you will definitely need a tripod; indoor lighting won’t get you a fast-enough shutter speed for handheld shots. (This can be a relatively cheap model; as long as it’s positioned on a sturdy surface, it should be able to keep your camera steady.) When you’re ready to shoot, just mount your camera to the tripod, activate the two-second self-timer , and start taking images.

Still life photography composition

Learning to compose still life photos is often a struggle for beginners. This is understandable, as still life composition brings up a ton of questions, such as: Where should I place all my items? Should they overlap? Should they be close to the background? What camera angle should I use?

Fortunately, still life composition isn’t as hard as it might seem. I have two main recommendations, and they will take you far:

First, if you’ve not encountered them before, read about the rule of thirds and the rule of odds . These will offer a fantastic compositional starting point for beautiful still life shots, plus they’re really easy to use.

Second, just keep moving your items around.

This latter recommendation might seem a bit silly, but I promise: If you rearrange your objects enough, you’ll eventually hit on an arrangement that looks great. Don’t just settle for the first composition that you try – instead, test an arrangement, then evaluate it critically. Determine what you like and dislike about it, then make adjustments.

As you create different compositions, here are a few items to keep an eye on:

- Overly empty gaps (you generally want to keep the entire arrangement balanced!)

- Busy areas (you don’t want to confuse the viewer with too much activity)

- Movement between objects (aim to lead the eye from one object to the next)

Remember: A tiny tweak can make a huge difference. So if an arrangement doesn’t seem perfect, make a few changes. Chances are that you’ll soon hit upon a better setup!

Tips and tricks to improve your still life photos

Now that you’re familiar with the basics, let’s dive into some of the higher-level aspects of still life photography, including subject selection, different lighting directions, and more!

1. Look at the work of great still life photographers

It’s a valuable practice to study the work of great still life photographers online. By observing their photos, you can learn about the different ways to arrange elements, and you can even find inspiration for new subjects.

But don’t limit yourself to photography alone; look at the world of painting as well. Masters like Cezanne offer a treasure trove of lessons on composition, balance, and the use of color. The way these painters arranged objects, used light, and chose colors can translate into unique insights for your photography. A painter’s eye for composition can open new doors for your creativity.

Learning from others can be an exciting and enlightening process. While it’s important to develop your unique style, the techniques and ideas you glean from observing the masters can enhance your skills.

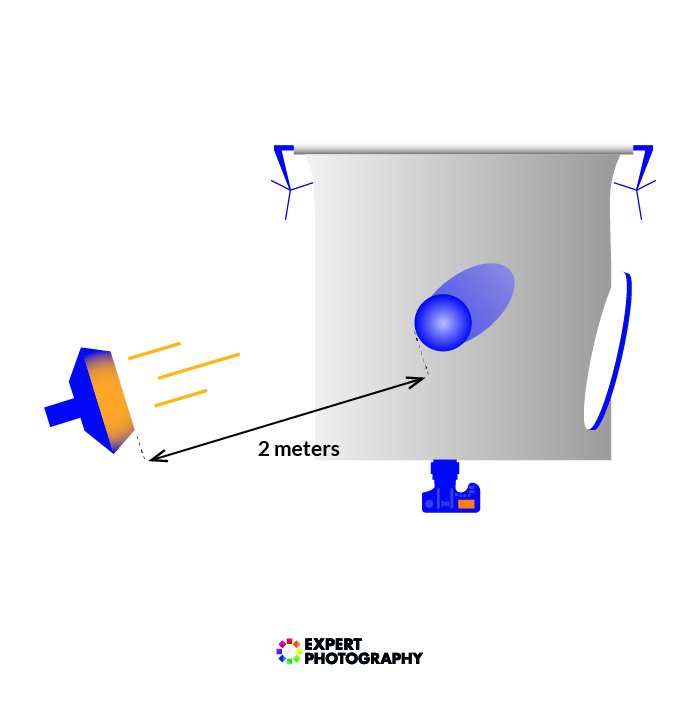

2. Experiment with sidelighting

Sidelighting is a powerful tool in still life photography. By ensuring that your light source is hitting the subject from the side rather than the front or back, you add shadows that improve a sense of three-dimensionality. The play of light and shadow brings depth and drama to an image, allowing ordinary objects to appear extraordinary.

A 45-degree angle is often a fantastic starting point for sidelighting. It offers a balanced blend of light and shadow, producing a visually appealing effect. Don’t be afraid to play with different angles and light sources; experimentation is key to finding what works best for your particular setup.

Realize that the angle of light can drastically change the mood and appearance of your photograph. By embracing the experimentation and understanding how sidelighting works, you add an essential tool to your still life photography toolkit. It’s a step towards creating more engaging, eye-catching images.

Bottom line: Whether you’re using natural light from a window or an artificial source, sidelighting can become your go-to option for stunning still life shots.

3. Pick items that interest you

Still life photography beginners often struggle to pick a subject and get started. But in truth, there are no “best” still life subjects, so there’s no need to stress! Ideal subjects are simply items that interest you , and they can come from anywhere, including:

- Around your house

- Flea markets and thrift stores

- Estate sales

- The grocery store

- The florist

Of course, the words “still life” generally conjure up visions of vases of flowers, pears on candlelit tables, old paper, and violins. And you can certainly capture beautiful still life shots by obtaining and arranging these “classical” items.

But you don’t need to spend time pursuing such images if they don’t interest you. Instead, ask yourself: What is meaningful to me ? What objects do I love? Is there a story I would like to tell with my still life?

Alternatively, you might look for items that simply catch your eye. This next shot contains a piece of dried seaweed on some calico. Was the seaweed meaningful to me? Not really. Did it tell a story? Nope. It simply looked beautiful, so I wanted to capture it!

Finally, you can capture “found” still life arrangements – that is, still life arrangements that already exist (in houses, backyards, or on the street). Here’s a found still life, taken of a friend’s bedside table:

When picking still life subjects, here’s my final piece of advice:

If you’re stuck, just find some items that are personal and important to you, such as:

- Family heirlooms

- Pictures containing relatives

- Books that you love

Then, after a bit of arranging, you’ll capture a still life that’s loaded with meaning!

4. Work with a theme

Still struggling to pick the right still life photography subjects? Then I highly recommend working around a single theme.

Themes are an essential aspect of still life photography that can add depth and coherence to your images. They help you move beyond randomly selected objects and push you to think about the mood and meaning you want to convey. Whether it’s a color, season, or concept, a unifying theme can drive creativity.

For example, if you choose a theme around the color blue, you may gather items like blue glassware, a blue scarf, or blueberries. The consistent color palette not only creates visual harmony but also allows you to explore various textures and shapes within a specific color family.

Themes also help in storytelling. A setup focused on a seasonal theme, like autumn, can evoke feelings of warmth, change, or nostalgia. From leaves to pumpkins, selecting objects that resonate with the chosen theme helps in creating visually compelling stories that speak to the viewer.

5. Carefully select a background

The background can make – or break- your still life. If you want great results, you must choose your background with great care.

Specifically, don’t choose a background that features distracting elements. Avoid eye-catching colors that draw the eye, and if you use fabric, make sure you iron it first (few things are more distracting than a wrinkled backdrop!).

Instead, keep it simple. Fabric, cardboard, and existing walls often work great, provided that they’re relatively plain. The goal is to emphasize your still life subjects (so the viewer knows exactly where to look).

Here’s an image featuring a plain backdrop made from a couple of old potato sacks:

And here’s another shot, this time featuring a sheet of red fabric:

Also, experimentation is important! Different background textures and colors can complement your subjects in different ways, so it pays to test out a few options before deciding on a final arrangement. You may be surprised by the backdrops that make your still life really pop.

And while I generally do advocate using a narrow aperture and a deep depth of field when starting out, over time, you might want to try experimenting with focus and depth of field . You can create a shallow depth of field effect – where you keep the front element sharp and the background blurry – for more artistic shots. It’s a trick that can also come in handy if you like the background but find it a little too conspicuous.

6. Try light painting for creative still life shots

Light painting is a thrilling technique that allows you to “paint” with light. It involves setting your camera to a long shutter speed, usually in the range of 10 to 30 seconds, and then moving a flashlight or candle around your subject during the exposure. The result can be mesmerizing.

One of the great things about light painting is that it enables you to have greater control over your lighting without investing in expensive strobes and softboxes. You can create unique effects and highlights exactly where you want them. All you need is a dark room and a source of light, such as a flashlight, candle, or even a glow stick.

Experiment with different light sources, movements, and exposure times. You’ll soon discover a whole new world of creative possibilities. Light painting can add depth, character, and flair to your photos, making it a valuable technique in your still life photography toolbox.

7. Consider using artificial lighting

Once you’ve mastered basic still life lighting using natural sources like windows or candles, you may wish to explore artificial lighting for more control. Studio strobes, speedlights, or continuous LEDs are common options, and each has its advantages.

For those just starting, speedlights can be an affordable choice. They are portable and easy to use but still deliver excellent results. Strobes, on the other hand, are more powerful and include modeling lights so you can see the lighting effect in advance.

Whatever your choice, softboxes are essential. A bare flash will result in harsh and unflattering light. Softboxes diffuse the light, making it softer and more pleasing to the eye. They come in various sizes and shapes, allowing you to fine-tune the lighting effect to match your vision.

Artificial lighting may seem intimidating at first, but with practice, you can use it to create stunning still life photographs. From generating specific effects to offering complete control over the intensity and direction of light, artificial lighting opens up a new realm of creativity. It’s an investment not just in equipment but in expanding your artistic capabilities.

8. Shoot from different angles

The angle you choose to shoot from can dramatically alter the look and feel of your still life photograph. While it’s common to start with a standard frontal composition, experimenting with different angles adds richness and variety to your portfolio.

Moving to the right or the left, shooting from above or below – these choices offer new perspectives on familiar subjects. Even slight adjustments in camera height can change how a setup is captured. Higher angles can amplify depth, making objects appear more spread out, while lower angles can give a greater sense of intimacy or grandiosity.

Experimentation is key here. There are no rigid rules, so feel free to explore various angles until you find what resonates with your subject and theme. Try photographing a bowl of fruit from directly above to emphasize shape and pattern, or shoot a vase of flowers from below to give it a towering, majestic appearance. The creativity of angles is in your hands.

9. Make sure you spend time editing your still life photography

Post-processing can make a huge difference to your still life photos, so I highly recommend you spend time editing your images in Lightroom, Photoshop, Capture One, or some other program.

Start out with basic adjustments, such as white balance, exposure, contrast, and saturation. Then, as you become more experienced, play around with more advanced options.

Consider doing HDR photography , where you take several images at different exposure levels then blend them together in Lightroom. Or use Photoshop to add a beautiful texture to your image for a painterly look:

How to create stunning still life photography: final words

As you’ve discovered, the world of still life photography offers a vast playground for creativity, exploration, and skill-building. By working with themes, you can craft images that are not only visually stunning but also filled with depth and story. Shooting from different angles adds another layer of expression and offers endless possibilities for capturing ordinary objects in extraordinary ways.

Remember to embrace the tools and techniques outlined, and practice to see how they transform your still life photography. The joy of creating mesmerizing still life photos isn’t reserved for professionals; it’s within your reach.

So experiment with lighting, composition, and editing. Have fun! Enjoy yourself! You’re bound to end up with some stunning photos.

Now over to you:

What type of still life photos do you plan to take? Which of these tips are your favorites? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Read more from our Tips & Tutorials category

is an Australian photographer working mainly in the areas of portraiture, fine art, and for the local press. Her work has been published, exhibited, selected and collected – locally, nationally and internationally, in many forms. All shot with very minimal gear and the photographic philosophy that it’s not so much the equipment, but what you do with it. You can see more of her work at www.leahawkins.com

- Guaranteed for 2 full months

- Pay by PayPal or Credit Card

- Instant Digital Download

- All our best articles for the week

- Fun photographic challenges

- Special offers and discounts

No products in the cart.

Still Life Photography: Ideas, Tips, and Theory for Success

- Jonathan Jacoby

Last updated:

- February 13, 2023

- See comments

Still life photography was born out of an ancient discipline in the visual arts. Already centuries ago, countless artists used the field of still life painting to test and display their technical skills.

Today in modern photography, not so much has changed. The still life image is still an incredibly useful medium to experiment, broaden your creative horizons, and show off your talent.

It can also serve as a useful base for generating new photography ideas and improving the diversity of your portfolio.

Today’s guide is going to delve deeply into the world of still life photography. By the end of this short read, you will understand not just what still life photography is all about and how it is viewed.

You will also have the aesthetic and technical understanding necessary to create excellent still life images by yourself. Without further ado, let’s get right into it!

What is Still Life Photography?

First, let’s lay down some working definitions. Still life photos are prominent in many genres and fields of visual art and design, but their popularity actually leads to a lot of confusion as to what precisely makes a still life and what doesn’t.

In simple words, a still life is a scene that portrays a static ( still ) set of subjects, usually everyday objects. These can be man-made or natural, inanimate objects or organic (such as plants).

As you can imagine, the arrangement and presentation of these objects – not to mention the choice of props – all play a huge role in how the viewer’s eye perceives a still life photo.

Anatomy of a Still Life Photo

To gain an understanding of how still life photography works in practice, you need to be aware of how it functions at its core.

When you dissect a still life and how it is made, it reveals itself as actually so much more than a visual motif. In truth, still life shots are the intersection where nearly all basic photography skills and techniques come into play at once.

That includes composition , exposure , lighting , aesthetics , complete control of your gear, and working with color .

Thanks to this universality, still life photography is a truly amazing learning tool for photographers of any experience level!

Throughout the rest of this chapter, we will delve deeper into what makes a still life photograph tick and how you can approach its many components without getting overwhelmed.

Created Still Lifes and Their Appeal

Though there are as many types of still life photographs as there are still life photographers, many choose to broadly divide still lifes into one of two categories.

The first of these are created still lifes. The word “created” here references the fact that the props, i.e. your subjects, are staged and carefully posed and put in place.

Because of this, created still lifes usually take place in a studio environment.

However, they don’t have to. You can create a still life scene by arranging props you find out in the outdoors and in natural light!

Created still life photography is seen by many as more beginner-friendly because it affords you unlimited time and creative control over every aspect of your composition.

Found Still Life Photography

As directly opposed to created still life photography, there is the found kind.

For a still life to be found means that for its props to be left as they were in nature, without any involvement on the side of the photographer.

Of course, you can still use artificial lighting (though there are some purists who would argue otherwise), but the main idea is to try and find interesting still life compositions in the world around you instead of staging them.

One word of caution: the found still life photographer faces one particular ethical duty shared with street photographers and many others.

Namely, to be honest about whether a photograph was really “found” or not.

For the sake of your dignity and the integrity of the medium, don’t pass of even minimally created still lifes as found photography!

Technical Guide for Successful Still Life Photography

Now that you should have a basic grasp of the aesthetic and compositional aspects of still life photography, let’s explore the technical side of the medium.

In the following, I’ll go over all the camera settings and key techniques you’ll need for success, including gear, lens requirements, and more!

Recommended Camera Bodies

Of the attributes that make a camera body perfect for still life photography, much of it has to do with sensor size.

The debate between APS-C and full frame cameras will likely never end completely, but larger sensor formats do offer some notable advantages for still life photographers.