- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Discover Chemistry

- Tiny Matters

Mad cow and the history, cause and spread of prion diseases

Mad cow disease, also known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) was first discovered in cattle in the UK in 1986. In 1996, BSE made its way into humans for the first time, setting off panic and fascination with the fatal disease that causes rapid onset dementia. In this episode, Sam and Deboki cover the cause, spread and concern surrounding mad cow and other prion diseases.

Transcript of this Episode

Sam: As a young kid I became pretty fascinated by the things that could kill me, particularly infectious diseases. Don’t ask me why, I just was. And the first one I remember becoming obsessed with was mad cow. The formal name for mad cow disease is bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE. The name makes sense — the brain of a cow with BSE looks spongy under a microscope, because of holes left by the disease. Although it can take years from the time a cow is infected to the time it first shows symptoms, like issues with coordination, once it does show symptoms things escalate quickly and the cow is usually dead within a couple weeks to six months.

Deboki: Mad cow disease was first discovered in 1986 in the UK, where it wreaked havoc for over a decade, killing nearly 200,000 cows and devastating many farming communities. In 1996, BSE made its way into humans for the first time, causing a decline in coordination, issues with vision, and the rapid onset of dementia. Over 200 cases of BSE have been reported — mostly in the UK — and everyone who was infected has died.

And in December 2003, mad cow made its first appearance in the US when an infected cow was discovered on a farm in Washington State. Today cases of BSE and of BSE making its way into people are pretty much nonexistent, thanks in large part to practices designed to keep us safe.

For example, mad cow kicked off because the feed being given to cows was infected. But since August 1997, the US FDA has banned the use of most cow parts and other animals to be used to make cow feed, limiting the risk of infected meat making it into their food.

Sam: I think we’re all used to hearing about infectious diseases caused by bacteria, viruses and a bunch of different parasites. But BSE is quite unusual: it’s not caused by any of those things. It’s caused by a protein, a fundamental building block of all living things.

Welcome to Tiny Matters. I’m Sam Jones and I’m joined by my co-host Deboki Chakravarti.

Deboki: Today on the show, we’re going to be focusing on prion diseases — rare, fatal brain diseases like mad cow that are caused by a protein malfunctioning and folding in a way it shouldn’t. I know the concept might sound a little weird and confusing, but Sam and I, and the scientists we chatted with, are going to break it down for you and talk about what’s being done to detect these diseases before something like mad cow happens again.

So what is a prion? It’s a protein that can take on two forms. The first one is what we consider the normal form, which doesn’t cause disease. Normal prions are found in the brain, although researchers don’t know much about what they do. But when people say “prion,” they’re usually not talking about the normal form. They’re usually talking about the other form…the bad, misfolded form that causes disease.

Mark Zabel: You can think of the normal form as sort of a really nice three-dimensional structure. Sort of balloon looking. When it misfolds into the prion, that balloon, three-dimensional structure becomes basically almost a two-dimensional structure. Think of it as like a bathroom tile. Very small, thin, flat.

Sam: That’s Mark Zabel, who’s the associate director of the Prion Research Center in the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at Colorado State University. He told us that when the misfolded prion — the bathroom tile as he described it — comes into contact with a normal prion, it causes it to also misfold. I think of it like a domino effect.

Deboki: And once you get a bunch of misfolded prions, those tiles stack up together and form fibers that tangle around each other, which then kills your neurons. As your neurons die off, it leaves holes in your brain—like the spongy brains seen in mad cow. And when you have holes in your brain it causes dementia, difficulty walking and speaking, sometimes even hallucinations, and ultimately death.

So how many misfolded prions is enough to cause disease?

Brian Appleby: I would say we don’t know that for sure except that prions aren’t desired to have. But is one misfolded prion protein enough to cause disease? Probably not. But the problem with prion disease is they aggregate, you know, they're kind of like the bad kids in the schoolyard. The bad kids recruit the good kids, and you have more bad kids, and that keeps amplifying and amplifying until you get disease. So that's kind of what happens — you get enough bad prions in the brain that it causes a variety of diseases in animals and humans.

Deboki: That’s Brian Appleby, a professor of neurology, psychiatry, and pathology at Case Western Reserve University.

Sam with Brian Appleby: What are some of the ways that someone could develop this disease? What would allow for these proteins to misfold?

Brian Appleby: So in humans, there's three main causes of prion disease. The most common cause by far is what we call sporadic. And there's a lot of similarity to that with Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, which are also sporadic illnesses for the most part. And what that means is that for reasons that we don't really understand, that normal protein becomes misfolded and misshapen spontaneously within the body after it's already been made. I equate it a lot to cancer. We all make cancer cells as we get older, but our body's generally able to detect them and get rid of them. The same is true with our proteins — we make bad proteins every day, but the likelihood of making bad proteins increases as we age, as well as our ability to detect them and clear them. And then you get these protein misfolding diseases like prion disease and Alzheimer's. Deboki: Brian told us around 85% of prion diseases are sporadic. But there are also prion diseases caused by a mutation in the gene that codes for the prion protein PRNP. This genetic mutation makes it more likely for the prion protein to misfold over a person’s lifetime.

And in addition to sporadic and genetic causes of prion disease, there are also acquired prion diseases. This is by far the most rare version and typically happens because of a medical procedure — say brain surgery, if there’s prion contamination on surgical equipment. It can also be caused by eating meat that contains infected nervous tissue. I think this is the version most people know about, because that’s what happened with mad cow.

People came down with the human version of BSE by eating beef that had been contaminated with nervous tissue of infected cows. But the cows developed BSE in the first place because they were fed sheep products infected with a prion disease called scrapie that’s been documented in sheep for over 300 years.

Sam: Another somewhat well-known acquired prion disease is kuru, which is caused by eating contaminated human brain tissue. In the 1950s and 60s, the Fore people in the highlands of Papua New Guinea experienced high levels of the disease, which turned out to be the result of ritualistic cannibalism where relatives prepared and consumed the bodies of deceased family members, including their brains.

So overall, there are 3 main categories of prion diseases — sporadic, genetic, and acquired — and within those categories you have more specific diseases like kuru which is of course acquired, fatal familial insomnia which is passed on genetically, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, or CJD, the most common prion disease that affects humans. CJD falls under all 3 categories — it can develop sporadically, genetically or be acquired. This is a form of prion disease that people exposed to BSE — mad cow — developed.

Deboki: And because the symptoms are pretty much identical throughout all of these diseases, the only way to really tell them apart is by looking at brain tissue under a microscope to see the size and distribution of the holes or prion protein deposits.

Brian Appleby’s work focuses on all three categories of human prion disease.

Sam with Brian Appleby: So what is it about prion diseases that you find so interesting?

Brian Appleby: A lot actually. So I am a trained neuropsychiatrist, geriatric psychiatrist by training. And I really got interested in the field primarily from the caregiver side because this is a very rapidly progressive neurodegenerative illness. It's horrible for families to go through and there's not a whole lot of clinical expertise to help them out. So that's how I originally got interested in it. And then of course at that time I was also kind of a dementia doctor, so there's a good overlap between the two. And then I got really interested in the science, which of course is extremely interesting. I think from the clinical side, seeing the patients, they're very difficult to diagnose sometimes. And then of course the biology and trying to understand that and how it affects public health.

Deboki: Brian is the director of the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center.

Brian Appleby: the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center was founded in 1997, mainly in response to the mad cow epidemic. Most countries wanted to develop surveillance programs to know whether or not people were being affected by mad cow disease. It's funded by the CDC and we're funded to do neuropathologic surveillance. So we collect brain tissue on patients who had CJD or another form of prion disease and examine it underneath the microscope to see whether or not it is in fact prion disease, because that's the only way to definitively diagnose it.

Deboki: They’re also working on developing tests to be able to more specifically diagnose people who appear to have a prion disease.

Brian Appleby: We also do a lot of outreach and education to clinicians, but also to funeral home providers because there's a lot of fear of potentially contracting this disease and people that deal with that.

Sam with Brian Appleby: I actually have a follow up based on what you just said, which was this sort of fear for people who are handling bodies of people who have passed away from prion diseases. There is some anxiety that you could actually get prion disease. How likely is that?

Brian Appleby: My predecessor used to say that the fear of prion disease was way more infectious than prion disease itself. And that's certainly true, right? It’s difficult to transmit prion disease and you really can only do it in certain scenarios. So you need to have infectious tissue which is almost always gonna be brain tissue. And then that either needs to be injected into a person, consumed orally by a person, or placed in another person's brain for transmission to occur. Now most of those scenarios don't happen in everyday life, right? So there are specific scenarios where it could happen though — neurosurgery, brain surgery, autopsies where we were removing the brain, and then in the past we used to reuse brain tissue and pieces that surrounded the brain in healthy individuals.

And in fact, that's how some prion disease got transmitted. One example is we used to get human growth hormone from cadavers through their pituitary gland, which is part of the brain. They would grind it up and inject it into children of short stature to treat their short stature and it would transmit prion disease. But we don't do that anymore. Now we make what we call recombinant human growth hormone or made in a laboratory human growth hormone. So we don't have to do those things. So it is hard to transmit. There are certain scenarios where you have to take precautions, but they are few.

Deboki: One place where precautions are of course necessary is if someone is doing laboratory research involving prions. In 2019, a researcher in France named Émilie Jaumain died of acquired CJD — at age 33, 10 years after pricking her thumb during an experiment with prion-infected mice. In 2021, a second lab worker in France was diagnosed with CJD, leading to a months-long moratorium on prion research at a number of public research institutions in the country.

Sam: Again, prion diseases in humans are incredibly rare and the scenarios where you’d be at risk for acquiring one are quite specific. But in other species, a prion disease called chronic wasting disease spreads easily and is on the rise.

Mark Zabel: Chronic wasting disease is a prion disease that affects cervids. Cervids include elk, deer, moose, caribou, reindeer, red deer. It’s a highly infectious disease. It's one of the most infectious prion diseases we've ever studied. It’s very similar to the sheep prion disease known as scrapie.

Sam: That’s Mark Zabel again, from Colorado State University. You heard him briefly at the top of the episode. Mark’s research focus is chronic wasting disease or CWD.

Mark Zabel: Until recently, within the past five to 10 years, it was thought that it jumped species and was caused from sheep scrapie and thought that maybe some deer came in contact with some contaminated environments, or came into contact with infected sheep. And that has been turned on its head just a little bit, based on some studies that my lab has done and others, but also the fact that CWD has most recently been found in Northern Europe, in Nordic countries, first in Norway, but since then, Sweden and Finland, and it's interesting because there's no known connection of CWD in those Nordic countries to North America.

There is sheep scrapie in Scandinavian countries, so there's a chance that it could have been a trans species event from sheep scrapie. We can't rule that out. But there's a really interesting story emerging in the Nordic countries, and that is they're finding a lot of moose with CWD. And the reason that's interesting is moose, unlike other cervid species, they're solitary animals. And we think that CWD is passed from deer to deer, elk to elk, by direct and indirect contact. But moose don’t behave that way, so how do they get it? That indicates that it's potentially a spontaneous disease.

Deboki: Remember a spontaneous disease is just that — it’s spontaneous. It’s like a form of cancer where, for no rhyme or reason, you just have cells that go rogue and start dividing like crazy. In the case of prion disease, it’s the prion proteins going rogue and misfolding like crazy.

Unlike human prion diseases, prions that cause CWD can be excreted in saliva. Deer are super social, they have nose to nose contact. Which is very cute, unless one of them has CWD. They can also excrete prions in urine and feces. And those prions can stick around in the environment for a long time, even decades.

Mark Zabel: We think they can accumulate to a point where now a deer sniffing around in the ground eating plants that have been contaminated with urine or feces can now be ingested in that way as well. So that's another indirect transmission. Also decaying carcasses in the environment from deer that passed away from CWD and other deer, elk or moose will come and kind of sniff around that carcass as well.

Deboki: The good and very important news to share is that at this point, there is no documented transmission of CWD to humans. But that doesn’t mean we should assume it will stay that way. Remember, BSE did cross the species barrier, from sheep to cows and then cows to humans.

Mark told us that one of his biggest concerns is that hunters are being exposed to CWD in large quantities. When people were exposed to mad cow, they were usually eating a burger that had been made from different cows combined into one patty, and maybe just one of those cows had the disease, so it was watered down. But for hunters, things are different.

Mark Zabel: Consider a hunter who’s killed a CWD infected animal. They're gonna feed that animal to a very small number of people, family and friends, maybe a handful, maybe a half dozen. The prion titer, the load that they get from eating that one sick animal, it's not diluted into a bunch of other animals. The infectious dose they're receiving is orders of magnitude higher than the people who ate an infected hamburger. So that could really stress the species barrier to breaking. That's one of my big fears.

Deboki: By the species barrier breaking, Mark means that with enough of that infectious protein present there’s a greater chance of infection and CWD could go from a deer problem to a human problem.

Sam: And I feel like we should say this again, because Mark reiterated it many times throughout our conversation: no cases of CWD jumping to humans have been reported. And there are ongoing studies looking at hunters to see if they’re dying of prion disease at a higher rate than the general public. Mark says that so far there's no evidence suggesting that.

I also asked Mark if there was concern about dogs contracting CWD. I’m a dog owner, and if you’ve ever owned a dog, chances are you know they're prone to sniff around and seek out gross and dead stuff. So I wondered if they were at risk.

Mark Zabel: I do have some good news for you about your dog though, and my dog. It seems that there's some species, some mammals, that are particularly resistant to prion disease — dogs are one of them. If you're a cat owner, unfortunately there is feline spongiform encephalopathy, and that was produced during the BSE outbreak. So not only did humans get it, but they also made cat and dog food out of some of those infected cattle and some cats in Europe ended up getting this new FSE, this new prion disease of cats, but no dogs. There is no canine spongiform encephalopathy.

Deboki: Mark and his colleagues are working on a bunch of things. One is developing tests that can easily detect CWD in feces found in the environment to monitor its spread. Just like human prion diseases, there are no current treatments for CWD, so they’re also working on therapeutics that could interfere with production of the diseased prion protein.

And Mark told us something else that’s really important about prion research. It’s applicable to a huge range of diseases where proteins don’t fold correctly.

Mark Zabel: Prion diseases belong to a larger family of diseases that we refer to as protein misfolding diseases. These are diseases that also are caused by normal proteins that we all express that misfold and start causing these amyloid or these plaques in the brain. Many of these diseases are much more common than prion diseases. So Alzheimer's disease, for example, Parkinson's disease, Lou Gehrig's disease, ALS — amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — traumatic brain injuries, chronic encephalopathies, are associated with proteins that misfold. So prion diseases are just a member of these much larger family of protein misfolding diseases.

Sam with Mark Zabel: That's interesting. And it also is interesting because I would imagine that, to some degree, the work that's done to try and understand those other contexts in which you have protein misfolding like a traumatic brain injury or Alzheimer's, that what you gather from those studies could often be more broadly applied.

Mark Zabel: Absolutely. And, since obviously I'm a prion researcher, I would turn that converse, because one thing that's really interesting about prion diseases that helps researchers, is that these lab animals I'm talking about rodents, especially, that we can genetically manipulate, they actually get a prion disease, and it is a bonafide prion disease, unlike Alzheimer's, right? Where we do study that in the lab and we use these genetically altered animals from mice, but it's just a model because they don't really get Alzheimer’s. We can manipulate them so that they get a form of something that looks like Alzheimer's, but it's not exactly Alzheimer's. But prion diseases can be completely recapitulated in a mouse, and that disease is exactly the same disease that humans will get from a prion disorder as well.

It’s really changing the way we think about proteins and how they function and what they really do.

Sam: Prion diseases are no doubt scary but hopefully this episode made you feel a little better about them. Unless you didn’t know they existed before this episode and in that case oops sorry. I can say with certainty that this episode would have made kid me — the one obsessed with mad cow — feel better, knowing that prion diseases are incredibly rare and being monitored, and that there are researchers making big strides to catch these diseases early, develop treatments, and prevent them altogether.

I think we can hop into this Tiny Show and Tell.

Deboki: Yeah, I can go first.

Sam: Perfect.

Deboki: My Tiny Show and Tell, it's not relevant to this episode, but it's also very related, because it's about a condition that kind of comes on very quickly and is very, very hard to test for, but that people have been making really exciting progress on recently. And this is preeclampsia, which is a condition that comes up around the middle of pregnancy that basically causes a lot of issues with blood pressure and can be really, really dangerous for people. It usually happens in around one in 25 pregnancies and in the US it affects black women more than white women.

I remember from previous experiences of being pregnant that it's like a thing that they ask you about very early on and that you're kind of like, "Ah, I don't know. I don't know how to tell you what my risk factors are for this." Doctors and nurses, they're always just trying to make sure to mitigate the risk of preeclampsia.

And one of the things that's really exciting is that the FDA has approved a blood test for helping pregnant people figure out if they're at risk for preeclampsia. So it's not necessarily something that I think you can take from my understanding super early on. But the way that it works right now, at least in Europe where this test is used, is that if you're around those middle weeks of pregnancy and you're starting to show symptoms of preeclampsia or things that could maybe be preeclampsia-like, you could take this test to figure out just how likely you are to actually have preeclampsia develop. Like I said, this is something that comes on very quickly. So you might have the symptoms of it, but you might not actually know for sure that's going to happen. But then once it does happen, it just happens so quickly that you need to be able to address it really quickly.

So having a test to help people figure out are these symptoms potentially preeclampsia earlier on, is super helpful. And it looks specifically at two proteins in the placenta and their ratios of one versus the other because if these two proteins are really unbalanced, you're more likely to develop severe preeclampsia. There's about a 96% accuracy for predicting who won't develop preeclampsia. And meanwhile, two-thirds of the people who do get a positive test result will end up developing severe preeclampsia. There's still a lot that needs to be done in terms of monitoring how well this test works, but I think it's just super important because I didn't mention this earlier, but some of the things that can happen with preeclampsia is that you can have kidney and liver failure, you can have seizures. So having some kind of test that can help people who are pregnant figure out what's going on so they can get the right treatment is super important.

Sam: Yeah. That is really important. And I think preeclampsia is something that a lot of people don't really know about maybe until they're trying to get pregnant or are pregnant. And in graduate school, actually, the research group right next to the lab I was in worked on preeclampsia.

Deboki: Oh, interesting.

Sam: And that's how I learned about it. I had no idea what it was and I like the idea of a test that could help tune a lot of people in to the fact that they could have preeclampsia, that it's likely that and not something else, so that if things do escalate, they can say to the doctor right away, "Look, I'm high risk for preeclampsia. That could be what this is," and just save that time that would be spent trying to figure out what might be going on. That's I mean lifesaving, right? So-

Deboki: Totally. Yeah.

Sam: Yeah. Thanks for sharing Deboki.

Deboki: Mm-hmm.

Sam: That's good news. I like that.

Deboki: Yeah.

Sam: In my Tiny Show and Tell this week, I'm going to take us back 5,000 years. So this is not current day testing developments. This is very different. So in 2008, archeologists discovered a 5,000 year old grave in the town of Valentina in southwest Spain. And so in this super old grave, they found ivory tusks, amber, ostrich eggshells, and a crystal dagger. And so they thought, "Okay, this probably belonged to an elite leader." And so then they dubbed the individual, The Ivory Man. But now there's a team of researchers, and they use this new technique I had not heard about before. It actually looks at this enamel forming protein, amelogenin, which I guess sticks around much better than DNA does. And the other thing is, apparently male and female chromosomes have different versions of the gene that produces this amelogenin protein.

And so you can actually use it to determine sex. And so by analyzing these proteins on two of the teeth of this person found in the 5,000 year old grave, they confirmed that's not The Ivory Man. It's The Ivory Lady. So yeah, it was a woman.

They also found a bunch of chemical traces of cannabis, wine, even some mercury, because people loved mercury back in the day. They were using it as a pigment. They were ingesting it, thinking it was curing a bunch of things. Oops. But yes, they found a lot of other stuff near her body, which would suggest that maybe she was involved in some sort of religious rituals. And this was during the Copper Age. And it seems like in the Copper Age in the Mediterranean, that this was actually pretty much in line with a lot of what was happening.

A lot of prehistoric women actually had some prestige. They held authority. And so our modern assumption, which is very paternalistic and male dominated, we're kind of viewing the past through that lens. And actually, in some ways, a lot of these societies were more progressive than the ones we have today. And it also reminded me that last October, we did an episode about some of our travels last year, the travel that I shared was going to Greece. And so one of the islands that I went to when I was in Greece was Crete, where you had the Minoan Society. So the Minoans were around during the Bronze Age. There's some overlap with the Copper Age, but it's generally slightly after. So the Copper Age ends around 2000 BCE, whereas the Bronze Age ends around 1000 BCE. Again, with the Minoans, initially people thought, "Oh, it was all men that were in charge," the usual, and then more and more evidence kept coming forward really making a compelling argument that like, "No, the people in charge, the rulers, they were women."

Deboki: That's so cool. And it's so interesting how we've developed these techniques to be able to understand these questions in different ways and to look at these remains. And I got very excited just when I heard crystal dagger too. I was just like, "That sounds so amazing."

Sam: I know. I know. Right?

Deboki: Thanks for tuning in to this week’s episode of Tiny Matters, a production of the American Chemical Society. This week’s script was written by Sam, who is also our executive producer, and was edited by me and by Michael David. It was fact-checked by Michelle Boucher. The Tiny Matters theme and episode sound design are by Michael Simonelli and the Charts & Leisure team. Our artwork was created by Derek Bressler.

Sam: Thanks so much to Brian Appleby and Mark Zabel for joining us. If you’d like to support us, pick up a Tiny Matters coffee mug! Or through August 11th send us your questions and we’ll enter you into a raffle to win a Tiny Matters mug. These can be science questions, questions about a previous podcast episode, questions about how Deboki and I made our way to science communication. Truly the sky's the limit. Send your questions to tinymatters@acs.org . You can find me on social at samjscience.

Deboki: And you can find me at okidokiboki. See you next time.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

iHeartRadio

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

Mad Cow Disease - Science topic

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Mad Cow Disease (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy)

Mad cow disease, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), is a disease that was first found in cattle. It's related to a disease in humans called variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD). Both disorders are universally fatal brain diseases caused by a prion. A prion is a protein particle that lacks DNA (nucleic acid). It's believed to be the cause of various infectious diseases of the nervous system. Eating infected cattle products, including beef, can cause a human to develop mad cow disease.

What is mad cow disease?

Mad cow disease is a progressive, fatal neurological disorder of cattle resulting from infection by a prion. It appears to be caused by contaminated cattle feed that contains the prion agent. Most mad cow disease has happened in cattle in the United Kingdom (U.K.), a few cases were found in cattle in the U.S. between 2003 and 2006. Feed regulations were then tightened.

In addition to the cases of mad cow reported in the U.K. (78% of all cases were reported there) and the U.S., cases have also been reported in other countries, including France, Spain, Netherlands, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and Canada. Public health control measures have been implemented in many of the countries to prevent potentially infected tissues from entering the human food chain. These preventative measures appear to have been effective. For instance, Canada believes its prevention measures will wipe out the disease from its cattle population by 2017.

What is variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD)?

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) is a rare, fatal brain disorder. It causes a rapid, progressive dementia (deterioration of mental functions), as well as associated neuromuscular disturbances. The disease, which in some ways resembles mad cow disease, traditionally has affected men and women between the ages of 50 and 75. The variant form, however, affects younger people (the average age of onset is 28) and has observed features that are not typical as compared with CJD. About 230 people with vCJD have been identified since 1996. Most are from the U.K. and other countries in Europe. It is rare in the U.S., with only 4 reported cases since 1996.

What is the current risk of acquiring vCJD from eating beef and beef products produced from cattle in Europe?

Currently this risk appears to be very small, perhaps fewer than 1 case per 10 billion servings--if the risk exists at all. Travelers to Europe who are concerned about reducing any risk of exposure can avoid beef and beef products altogether, or can select beef or beef products, such as solid pieces of muscle meat, as opposed to ground beef and sausages. Solid pieces of beef are less likely to be contaminated with tissues that may hide the mad cow agent. Milk and milk products are not believed to transmit the mad cow agent. You can't get vCJD or CJD by direct contact with a person who has the disease. Three cases acquired during transfusion of blood from an infected donor have been reported in the U.K. Most human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is not vCJD and is not related to beef consumption but is also likely due to prion proteins

Find a Treatment Center

- Neurology and Neurosurgery

Find Additional Treatment Centers at:

- Howard County Medical Center

- Sibley Memorial Hospital

- Suburban Hospital

Request an Appointment

Moyamoya Disease

Motor Stereotypies

Related Topics

- Brain, Nerves and Spine

Advertisement

Behavior towards health risks: An empirical study using the “Mad Cow” crisis as an experiment

- Published: 25 October 2007

- Volume 35 , pages 285–305, ( 2007 )

Cite this article

- Jérôme Adda 1 , 2

794 Accesses

23 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The paper exploits the “Mad Cow” crisis as a natural experiment to gain knowledge on the behavioral effect of new health information. The analysis uses a detailed data set following a sample of households through the crisis. The paper disentangles the effect of non-separable preferences across time from the effect of previous exposure. It shows that new health information interacts in a non-monotonic way with disease susceptibility. Individuals at low or high risk of infection do not respond to new health information. The results show that individual behavior partly offsets the effect of new health information.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Heterogeneous adaptive behavioral responses may increase epidemic burden

Risk and Prevention of Infectious Disease

Capturing Human Behaviour: Is It Possible to Bridge the Gap Between Data and Models?

The self-selection has been pointed out by Farrell and Fuchs ( 1982 ) and Viscusi and Hersch ( 2001 ) for instance in the case of tobacco.

Consumers learned about the crisis on March 20, 1996, so their reactions to the news are observed during 13 weeks. This is enough to study their immediate reaction but not longer term behavior.

The figure was produced with a roughness penalty method. See Green and Silverman ( 1994 ) and Chesher ( 1997 ) for an application. We experimented with different roughness penalties and settled for a value of 15 which produced a smooth enough graph and preserved the shape of the data.

Adda and Cornaglia ( 2006 ) document a related trade-off for tobacco consumption.

The country of origin of the beef was not recorded, because, up to 1997, it was not legal to reveal the country of origin to the consumer for “fear of distortions” on the beef market. Yet, shortly after the crisis, the French retail industry set up a label on domestic beef, which was assumed to be safer than foreign beef. In April 1996, the consumer had then the choice between French and foreign beef, but the precise origin of the foreign beef was not indicated. At the time of the crisis, French cows had also been diagnosed with BSE, so it is not clear whether the label was very meaningful. There is no indication that the introduction of this label changed the aggregate demand for beef.

With hindsight, this does not appear to be a rational behavior as these cuts are closer to the spine and therefore more likely to lead to contamination. However, at the time of the crisis, there was not extensive knowledge about the transmission of the disease, especially among consumers.

In France, the awareness of a link between beef, cholesterol and coronary heart diseases (CHD) is lower than in many other countries. France has the lowest rate of CHD in the world together with Japan. The rate is about three times lower than in the USA, and four times lower than in the UK. The consumption of beef is mostly determined by cultural differences across regions.

The first stage indicates that the instruments have power with F tests with associated p values of 0 for all endogenous variables.

We do not find statistical evidence of gender differences for younger children.

However, the fact that parents cannot split from their teenagers gives these children some bargaining power.

We also estimated a tobit model which takes into account the truncation at zero, as expenditures cannot be negative. Consumers with a small stock might have little scope to reduce their consumption, which might explain why they respond less to the crisis. We found that the results are comparable to the one in Table 3 .

We are grateful to W. Kip Viscusi for suggesting this point.

Becker and Mulligan ( 1997 ) discuss the case of an endogenous discount factor.

Adda, Jérôme and Francesca Cornaglia. (2006). “Taxes, Cigarette Consumption and Smoking Intensity,” American Economic Review 96(4), 1013–1028.

Article Google Scholar

Antoñanzas, Fernando, W. Kip Viscusi, Joan Rovira, Francisco J. Braña, Portillo Fabiola, and Iirineu Carvalho. (2000). “Smoking Risks in Spain: Part I Perception of Risks to the Smoker,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 21(2/3), 161–186.

Becker, Gary S. and Casey B. Mulligan. (1997). “The Endogenous Determination of Time Preference,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(3), 729–758.

Becker, Gary S. and Kevin M. Murphy. (1988). “A Theory of Rational Addiction,” Journal of Political Economy 96(4), 675–699.

Bourguignon, François. (1999). “The Cost of Children: May the Collective Approach to Household Behavior Help?” Journal of Population Economics 12(4), 503–521.

Browning, Martin and Pierre-André Chiappori. (1998). “Efficient Intra-Household Allocations: A General Characterization and Empirical Tests,” Econometrica 66(6), 1241–1278.

Chesher, Andrew. (1997). “Diet Revealed? Semiparametric Estimation of Nutrient Intake-Age Relationships,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 160(3), 389–428.

Deaton, Angus and John Muellbauer. (1980). “An Almost Ideal Demand System,” American Economic Review 70(3), 312–326.

Google Scholar

Ehrlich, Isaac and Hiroyuki Chuma. (1990). “A Model of the Demand for Longevity and the Value of Life Extension,” Journal of Political Economy 98(4), 761–782.

Farrell, Phillip and Victor Fuchs. (1982). “Schooling and Health: The Cigarette Connection,” Journal of Health Economics 1, 217–230.

Green, Peter J. and Bernard W. Silverman. (1994). Nonparametric Regression and Generalised Linear Models: A Roughness Penalty Approach . London: Chapman and Hall.

Gruber, Jonathan. (2001). “Risky Behavior among Youth: An Economic Analysis.” In Jonathan Gruber (ed), Risky Behavior Among Youth: An Economic Analysis . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurd, Michael, Daniel MacFadden, and Angela Merrill. (2001). “Predictions of Mortality among the Elderly.” In David Wise (ed), Themes in the Economics of Aging . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurd, Michael D. and Kathleen McGarry. (1995). “Evaluation of the Subjective Probabilities of Survival in the Health and Retirement Study,” Journal of Human Resources 30(0), S268–292.

Hurd, Michael D. and Kathleen McGarry. (2002). “The Predictive Validity of Subjective Probabilities of Survival,” Economic Journal 112(482), 966–985.

Khwaja, Ahmed, Frank Sloan, and Sukyung Chung. (2006). “The Effects of Spousal Health on the Decision to Smoke: Evidence on Consumption Externalities, Altruism and Learning within the Household,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 32(1), 17–35.

McElroy, Marjorie. (1990). “The Empirical Content of Nash Bargained Household Behavior,” Journal of Human Resources 25, 559–583.

Nichèle, Véronique and Jean-Marc Robin. (1995). “Simulation of Indirect Tax Reforms Using Pooled Micro and Macro French Data,” Journal of Public Economy 56, 225–244.

Pollak, Robert A. (1970). “Habit Formation and Dynamic Demand Functions,” Journal of Political Economy 78(4), 745–763.

Viscusi, W. Kip and Joni Hersch. (2001). “Cigarette Smokers as Job Risk Takers,” Review of Economics and Statistics 83(2), 269–280.

Viscusi, W. Kip (1990). “Do Smokers Underestimate Risks?” Journal of Political Economy 98(6), 1253–1269.

Viscusi, W. Kip (1993). “The Value of Risks to Life and Health,” Journal of Economic Literature 31, 1912–1946.

Viscusi, W. Kip (1997). “Alarmist Decisions with Divergent Risk Information,” The Economic Journal 107, 1657–1670.

Viscusi, W. Kip, Welsey A. Magat, and Joel Huber. (1987). “An Investigation of the Rationality of Consumer Valuations of Multiple Health Risks,” Rand Journal of Economics 18(4), 465–479.

Viscusi, W. Kip and Michael J. Moore. (1989). “Rates of Time Preference and Valuations of the Duration of Life,” Journal of Public Economics 38, 297–317.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK

Jérôme Adda

Institute for Fiscal Studies, 7 Ridgmount Street, London, WC1E 7AE, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jérôme Adda .

Additional information

I am grateful to SECODIP, the Observatoire des Consommations Alimentaires, to Christine Boizot for research assistance, to Gary Becker, Russell Cooper, Christian Dustmann, Valérie Lechene, Costas Meghir, Jean-Marc Robin, W. Kip Viscusi, Tim Besley, an anonymous referee and to seminar participants at Boston University, ESEM, Harvard University, INRA, INSEE, LSE, University of Bristol, University of Chicago, University College London and University of Toulouse for comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimer applies.

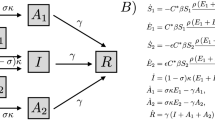

The first order condition of model 1 is:

where u i and V i denote the partial derivative of the utility function and second period indirect utility function with respect to the i th argument. First differentiating this expression gives:

which can be written more compactly as:

Standard restrictions on the shape of the utility function imply that u i > 0, u ii < 0, V i > 0, V ii < 0. Moreover, the definition of the survival probability implies that \(\partial \pi(S,\kappa)/\partial S=\pi_1\le 0\) and that \(\partial \pi(S,\kappa)/\partial \kappa=\pi_2\le 0\) , if individuals perceive that nvCJD is a threat to life.

If u 12 ≥ 0 (beef and other meat products are complements) and the relationship between survival and beef consumption is concave ( π 11 ≤ 0, then \(\tilde{A}_B\le 0\) , \(\tilde{A}_p\le 0\) and \(\tilde{A}_y \ge 0\) . The effect of health information on consumption of beef is equal to:

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Adda, J. Behavior towards health risks: An empirical study using the “Mad Cow” crisis as an experiment. J Risk Uncertainty 35 , 285–305 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9026-5

Download citation

Published : 25 October 2007

Issue Date : December 2007

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9026-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health risks

- Health behavior

- Intra-household decision

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

17 Mad Cow Disease and Englishmen: Dementia of Humans—Prions: Folding Protein Transmissible Diseases

- Published: September 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter studies mad cow disease. In 1985–1986, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease, was first identified in cattle of southern England, and within two years, over 1,000 instances of infected cattle surfaced in more than 200 herds. Epidemiologic investigations indicated that the addition of meat and bone meal as a protein supplement to cattle feeds was the likely source of that infection. By 1993, cases of mad cow disease peaked at over 1,000 per week. In addition to controlling the BSE epidemic in cattle, procedures were established to gauge whether this disease was a human health problem and to safeguard the population from the potential risk of BSE transmission. As a defense measure, in 1990, a national Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) surveillance unit was established in the United Kingdom to monitor changes in the disease pattern of CJD that might indicate transmission of BSE to humans. Although CJD is the most common form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in humans, it is a rare disease with a uniform world incidence of about 1 case in 1 to 2 million persons per year.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 16 |

| November 2022 | 8 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| October 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 6 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.322(7290); 2001 Apr 7

Regular review

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy and variant creutzfeldt-jakob disease.

It is sometimes forgotten that in the story of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease there is but one incontestable fact, that bovine spongiform encephalopathy is the cause of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. First suggested by their temporospatial association and the distinctive features of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the link has since been proved by their equally distinctive and shared biological and molecular features. 1 – 3 All the rest is speculation, more or less plausible according to the arguments advanced and the absence of any satisfactory alternative explanations.

From an epidemiological point of view bovine spongiform encephalopathy has been a classic epidemic and will undoubtedly become a textbook example for students (fig (fig1). 1 ). From economic, political, and medical points of view it has been an unmitigated disaster. Why did it begin when it did, and how did it happen?

Summary points

- The infectious agent that causes scrapie in sheep crossed the species barrier to bovines to cause bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- Changes in the rendering of livestock carcases allowed infectivity to survive and contaminate meat and bone meal in livestock feed, amplifying infection to epidemic proportions

- Export of contaminated meat and bone meal and live cattle incubating the disease caused the spread of bovine spongiform encephalopathy to other countries

- Bovine spongiform encephalopathy caused variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, most probably through adulteration of cooked meat products with mechanically recovered meat contaminated by compressed spinal cord and paraspinal ganglia

- International regulatory measures are limiting the further spread of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, its entry into the human food chain, and potential secondary human to human spread of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, so that both diseases should gradually disappear

Chronology of epidemic of bovine spongiform encephalopathy in United Kingdom, 1986-2000

Origin of bovine spongiform encephalopathy: recycled scrapie

The first case of a cow with bovine spongiform encephalopathy was diagnosed in 1986, and because of the long incubation periods that are characteristic of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies—scrapie, for example, has an incubation period of about three years—the moment of infection can be assumed to have occurred years earlier. Was this just a chance occurrence, or was there some kind of environmental event that led to the infection?

The theory favoured by most scientists who have studied the disease is that it originated from an infection by scrapie in sheep. It began in the United Kingdom and not elsewhere because of a comparatively high incidence of scrapie in UK sheep and a comparatively large proportion of sheep in the mix of carcases rendered for animal feed for livestock. 4 It began in the mid-1980s because of the elimination several years earlier of a step in tallow extraction from rendered carcases that allowed some tissue infected with scrapie to survive the process and to be recycled as cattle adapted scrapie or bovine spongiform encephalopathy. 5