COVID-19’s Economic Impact around the World

Key takeaways.

- Although the COVID-19 pandemic affected all parts of the world in 2020, low-, middle- and high-income nations were hit in different ways.

- In low-income countries, average excess mortality reached 34%, followed by 14% in middle-income countries and 10% in high-income ones.

- However, middle-income nations experienced the largest hit to their gross domestic product (GDP) growth, followed by high-income nations.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, the world economy has been affected in many ways. Poorer countries have suffered the most, but, despite their greater resources, wealthier countries have faced their own challenges. This article looks at the impact of COVID-19 in different areas of the world.

First, I put 171 nations into three groups according to per capita income: low, middle and high income. Second, I examined health statistics to show how hard-hit by the virus these nations were. Then, by comparing economic forecasts the International Monetary Fund (IMF) made in October 2019 (pre-pandemic) for 2020 with their actual values, I obtained estimates for the pandemic’s impact on growth and key economic policy variables.

Low- and high-income groups each compose 25% of the world’s countries, and the middle-income group makes up 50%. Average income per capita in 2019 was more than five times larger in the middle-income group than in the low-income group. In the high-income countries, it was almost 20 times larger.

Health Outcomes and Policies

The first table shows that COVID-19 had a significant impact on all three groups. Average excess mortality, which indicates how much larger the number of deaths was relative to previous years, was more than 34% in low-income countries, almost 14% in middle-income countries and about 10% in high-income countries. And even though poorer countries were more affected by deaths, their COVID-19 testing was much more limited given their smaller resources.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, high-income countries did more than one test per person, while low-income countries did only one test per 27 people (or 0.037 per person). Given the significant differences in testing, it is not surprising that reported cases were much higher in wealthier countries. Finally, note that there were significant differences in the progress of vaccination. As of June 2021, nearly 20% of the population in the wealthiest countries was fully vaccinated compared to about 2% in the poorest countries.

Impact on GDP Growth

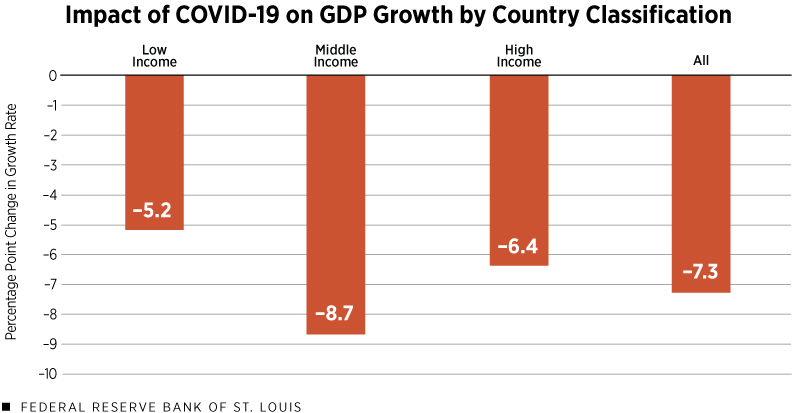

COVID-19-related lockdowns were very common during 2020-21, directly impacting economic activity. The figure below shows the impact on GDP. To isolate the impact of COVID-19 from previous trends, I plotted the difference between the actual GDP growth in 2020 and the IMF forecast made in October 2019.

The immediate consequence of closing many sectors of the economy was a significant decline in GDP growth, which was as large as 8.7 percentage points for the median middle-income countries. Wealthier countries suffered a bit less, with a median of 6.4 percentage points, mainly because they began to recover before the end of 2020. The impact of COVID-19 was smaller in poorer countries because many did not have the resources to implement strict lockdowns. However, even in this group of countries, median GDP growth was 5.2 percentage points lower than expected.

SOURCES: IMF World Economic Outlook Reports (April 2021 and October 2019), Penn World Table (version 10.0) and author’s calculations.

NOTE: The COVID-19 impact is the difference between the actual gross domestic product growth rate in 2020 and the IMF forecast for it made in October 2019.

Economic Policies

Differences in GDP performance are not only related to lockdowns but also to economic policy responses. The second table contains information about six policy variables.

In particular, the first three rows present the fiscal response to the pandemic computed as the difference between the actual value in 2020 and the IMF forecast made before the pandemic in October 2019 relative to GDP. Revenue relative to GDP declined slightly in all regions, but mostly in middle-income countries, reaching more than 1 percentage point of GDP.

Expenditures relative to GDP, however, increased in middle- and high-income countries while remaining stable in low-income countries. These expenditures increased by nearly 7 percentage points of GDP in high-income countries. The more significant fiscal deficit relative to GDP implied a larger increase in net government borrowing, which reached 7 percentage points of GDP in the median high-income countries.

Finally, COVID-19 also had a clear impact on the evolution of monetary aggregates such as cash and deposits. In the table, to isolate the impact of COVID-19 from previous trends, I present the growth rate of M1 and M2 M1 generally includes physical currency, demand deposits, traveler’s checks and other checkable deposits. M2 generally includes M1 plus savings deposits, money market securities, mutual funds and other time deposits. Note that the above definitions can differ slightly by country. net of the yearly growth rates of these variables between 2017 and 2019. The pandemic implied an increase in the growth rate of monetary aggregates across countries in all income groups, but more significantly in wealthier countries.

For instance, the growth rate in M1 was over 10 percentage points larger than in the previous two years in the median high-income countries. Without a change in money demand, such an acceleration in the quantity of money would have implied increasing inflation.

However, the last row of the table shows that inflation remained stable in 2020. In fact, for middle- and high-income countries, inflation in 2020 was lower than the IMF forecast made in October 2019.

Conclusions

COVID-19 impacted health outcomes in all regions of the world. Wealthier countries responded with more testing and quicker vaccination rates. Comparing actual outcomes with pre-pandemic forecasts, I found a significant impact of the pandemic on GDP growth, which is more prominent in middle-income countries.

I conjecture that the impact on GDP growth was less significant in the poorest countries because of less restrictive lockdowns and in the wealthiest countries because of more aggressive economic policies.

- M1 generally includes physical currency, demand deposits, traveler’s checks and other checkable deposits. M2 generally includes M1 plus savings deposits, money market securities, mutual funds and other time deposits. Note that the above definitions can differ slightly by country.

Juan M. Sánchez is an economist and senior economic policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. He has conducted research on several topics in macroeconomics involving financial decisions by firms, households and countries. He has been at the St. Louis Fed since 2010. View more about the author and his research.

Related Topics

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe .

Media questions

Publications

- Analysis & Opinions

- News & Announcements

- Newsletters

- Policy Briefs & Testimonies

- Presentations & Speeches

- Reports & Papers

- Quarterly Journal: International Security

- Artificial Intelligence

- Conflict & Conflict Resolution

- Coronavirus

- Economics & Global Affairs

- Environment & Climate Change

- International Relations

- International Security & Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Science & Technology

- Student Publications

- War in Ukraine

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South America

- Infographics & Charts

US-Russian Contention in Cyberspace

The overarching question imparting urgency to this exploration is: Can U.S.-Russian contention in cyberspace cause the two nuclear superpowers to stumble into war? In considering this question we were constantly reminded of recent comments by a prominent U.S. arms control expert: At least as dangerous as the risk of an actual cyberattack, he observed, is cyber operations’ “blurring of the line between peace and war.” Or, as Nye wrote, “in the cyber realm, the difference between a weapon and a non-weapon may come down to a single line of code, or simply the intent of a computer program’s user.”

The Geopolitics of Renewable Hydrogen

Renewables are widely perceived as an opportunity to shatter the hegemony of fossil fuel-rich states and democratize the energy landscape. Virtually all countries have access to some renewable energy resources (especially solar and wind power) and could thus substitute foreign supply with local resources. Our research shows, however, that the role countries are likely to assume in decarbonized energy systems will be based not only on their resource endowment but also on their policy choices.

What Comes After the Forever Wars

As the United States emerges from the era of so-called forever wars, it should abandon the regime change business for good. Then, Washington must understand why it failed, writes Stephen Walt.

Telling Black Stories: What We All Can Do

Full event video and after-event thoughts from the panelists.

- Defense, Emerging Technology, and Strategy

- Diplomacy and International Politics

- Environment and Natural Resources

- International Security

- Science, Technology, and Public Policy

- Africa Futures Project

- Applied History Project

- Arctic Initiative

- Asia-Pacific Initiative

- Cyber Project

- Defending Digital Democracy

- Defense Project

- Economic Diplomacy Initiative

- Future of Diplomacy Project

- Geopolitics of Energy Project

- Harvard Project on Climate Agreements

- Homeland Security Project

- Intelligence Project

- Korea Project

- Managing the Atom

- Middle East Initiative

- Project on Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship

- Security and Global Health

- Technology and Public Purpose

- US-Russia Initiative to Prevent Nuclear Terrorism

Special Initiatives

- American Secretaries of State

- An Economic View of the Environment

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Russia Matters

- Thucydides's Trap

Views on the Economy and the World

A blog by jeffrey frankel.

Blog Post - Views on the Economy and the World

- Jeffrey Frankel

The Covid-19 pandemic has had differentiated impacts across countries. This is true even among the set of Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs), which share the disadvantages of more poverty, less adequate health care, and fewer jobs that can be done remotely , compared to Advanced Economies.

Differentiation across continents

Surprisingly, the rates of infection and death have so far been lower in most EMDEs than in the US and Europe, as pointed out by Pinelopi Goldberg and Tristan Reed, and by Raghuram Rajan . Undercounting is undoubtedly massive, however. Furthermore, the situation is evolving rapidly .

Across continents, health in Latin America has been the hardest hit in general among EMDEs. Southeast Asia has been the least affected; for example, Vietnam and Thailand report extraordinarily few cases.

Why has the coronavirus hit Latin America so hard? Obvious possible reasons include the region’s inequality, large densely populated cities, many workers in the informal sector, inadequate public health systems, and many internal migrants (a problem that also looms large in India). A less obvious factor is that Latin America — like North America and Europe — had had less experience with pandemics in recent decades, as compared to East Asia or Africa, where SARS and Ebola made people more familiar with the dangers, and the consequent need for social distancing.

The situation in sub-Saharan Africa is unclear. On the one hand, the numbers of cases and deaths have been relatively low, at least up to now. The young population may help explain this. On the other hand, testing is probably even more inadequate here than elsewhere and the situation is worsening rapidly in South Africa. Apparently hotspots start in major metropolises with busy international airports – think Milan, London, New York, and now Johannesburg — and then inevitably spread out to neighboring regions with a lag.

Differentiation within Latin America

There is also a differentiation of the impact within continents. In Latin America, Brazil and Mexico are suffering especially badly. Brazil ranks #2 in the world, in absolute numbers of reported cases and deaths, after the United States. Uruguay is apparently doing the best. It is not that Uruguay is following the Trump philosophy and reporting few cases by means of a few tests; it has a low rate of positive results per test, which is the more meaningful statistic.

There is a ready explanation for why Brazil and Mexico are suffering such high rates of infection and mortality : poor political leadership. Their presidents are following the strategy that Trump has pioneered since the start: denying the seriousness of the situation and visibly undermining experts’ recommended responses such as campaigns to get people to wear masks. (Nicaragua probably belongs on this list of ostrich-leaders, but test numbers are unavailable.)

Then there is the case of Peru. It is hard to say what the government has done wrong, and yet reported cases and deaths per capita are worse than Brazil and almost as bad as the U.S. Similarly, one can’t explain why Chile reports more cases per capita than virtually any country.

Economic impact

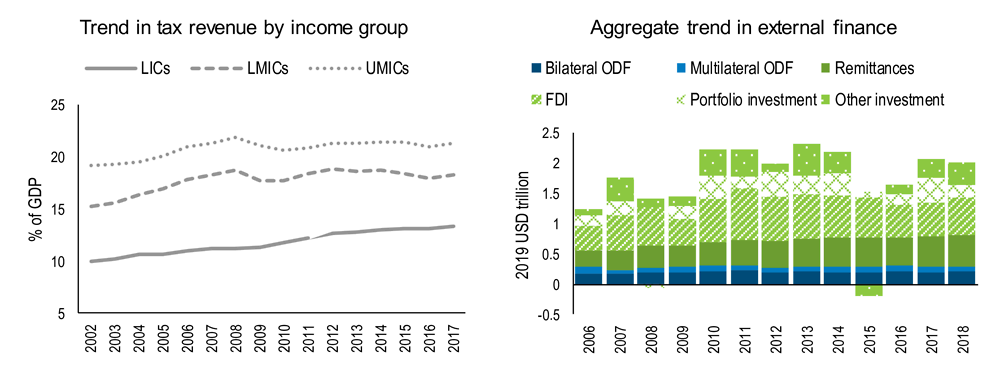

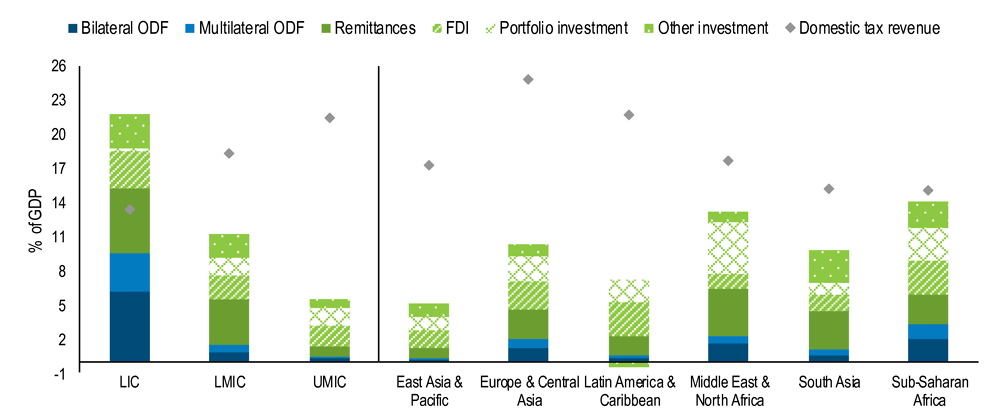

The economic impact of the pandemic shock is worse in EM and Developing Economies than in advanced economies. Besides the direct health impact, including lockdowns as in advanced countries, they have lost major sources of foreign exchange: export revenue (especially in the case of oil exporters), tourism, and remittances from emigrants. In March, global investors pulled out of emerging markets, in a switch to risk-off attitudes in financial markets generally. Subsequently, as a tremendous stimulus by the Fed restored investors’ reach for yield, capital flows returned to some countries. The current easy conditions in global financial markets mean that the much-invoked “perfect storm” analogy does not quite apply. But the situation facing EMDEs is bad enough as it is. Moreover, the current risk-tolerance in financial markets may not hold up.

The US and other advanced countries have been able to respond to the coronavirus recession with massive domestic government spending. EMDEs, in contrast, lack the fiscal space to respond with big spending programs , even for public health and support for hard-hit households, let alone for general macroeconomic stimulus. (The US can get away with running record deficits, not because it has been prudent in the past – it hasn’t – but because of its “exorbitant privilege”: investors everywhere are happy to hold dollars and US treasury bills.)

Some debtors, including Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Nigeria, and Venezuela, already had severe debt troubles even before the pandemic, and have had to restructure their debts or default. Some others like Peru entered 2020 with relatively strong debt and reserve positions (due to prudent policies put in place when mineral prices were high) and yet have been badly hit by both the pandemic and the global recession nonetheless.

The G20 moratorium and what it leaves out

In recognition of acute financing constraints, the G20 in April offered to suspend bilateral official debt payments for the year, for the world’s 73 poorest countries. But this step falls short in four different ways.

The suspension is of course not the same as debt forgiveness. There is little reason to think that the situation will be better at the end of the year. Further debt restructuring will be needed in some cases.

It is very unclear to what extent China will participate among the creditors offering relief. This matters a lot. As Carmen Reinhart and co-authors have uncovered, China is not merely the largest official creditor; its outstanding claims surpass “the loan books of the IMF, World Bank and of all other 22 Paris Club governments combined.”

The G20 moratorium also doesn’t include private creditors . Indeed, many debtors are showing themselves reluctant to take up the G-20 suspension offer for fear that downgrading would lose them access to private capital markets. In past debt crises, the international community (there used to be such a thing), asked the private sector to participate simultaneously with the IMF and rich-country governments: Rescue packages associated with IMF programs took steps so that the foreign exchange freed up by new public loans to the debtor country, conditional on sacrifices by its population, did not just go to paying off private creditors. In the 1990s currency crises, it was called Private Sector Involvement. Similarly, in the 1982 international debt crisis, rich-country banks were “bailed in” to the rescue effort rather than being “bailed out.” Where restructuring is necessary, private creditors should do their share.

The G-20 moratorium doesn’t extend to middle-income countries. But some of them will need accommodation too.

What else is to be done? EMDEs need to be able to export to the rest of the world, to restore growth and to earn the foreign exchange to service their international debts. But global trade has collapsed. The twin reasons are the worst tariff war since the 1930s followed by the worst global recession since the 1930s. The whole world is paying a cost for an absence of political leadership and a virtual breakdown in the multi-lateral order.

- James W. Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth

- Member of the Board, Belfer Center

- Climate agreements

- Environmental economics

- U.S. foreign policy

- Monetary policy

- Economic policy

- Globalization

- International development

- International finance

- National security economics

- Bio/Profile

- Media Inquiries

- (617)-496-3834

- More by this author

Related Posts

Belfer center email updates, belfer center of science and international affairs.

79 John F. Kennedy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-1400

COVID-19: Effects in Developing Countries

In this section.

- Helping the Media to Strengthen Democracy

- How can the private sector promote social change?

- How to Achieve Social Change Through Governments

- Restoring Health and Economic Growth in Developing Countries

- Social Change Through Public Organizing and Social Movements

July 22, 2020

Four Harvard Kennedy School scholars offered a worrying picture of the current impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on developing countries and an equally daunting assessment of the medium-term outlook. In a virtual discussion on July 22, these faculty members provided examples of how individual countries are reeling from the pandemic as well as macro-economic perspectives on broader trends for regional trade and recovery from severe lockdowns. The participants were Eliana Carranza, adjunct lecturer in public policy and a senior economist at the World Bank Jobs Group; Rema Hanna, the Jeffrey Cheah Professor of South-East Asia Studies; Jeffrey Frankel, the James W. Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth; and Isabel Guerrero Pulgar, adjunct lecturer in public policy and a development economist. The session was part of the Dean’s Discussion series, hosted by Kennedy School Dean Douglas Elmendorf, the Don K. Price Professor of Public Policy, and moderated by his chief of staff, Sarah Wald, an adjunct lecturer.

Jeffrey Frankel

Jeffrey Frankel sketched a varied set of economic and public health policy responses by developing countries to the pandemic, with similarly varied outcomes. He said Latin America had been hit particularly hard, while Southeast Asia far less so, and that South Africa could be hitting a crisis stage. Heavy concentrations of populations in cities are among the explanations for negative effects for Latin America. The hardest-hit countries there, Mexico and Brazil, had suffered failures of leadership that magnified the negative effects, he said, “just as our leaders have failed us in the United States.” Developing countries are constrained by their balance of payments, as the global shock has hit their commodity exports, tourism, remittances and capital inflows.

Eliana Carranza

Eliana Carranza said the policy choice during the pandemic often has been framed as either saving lives or saving economies. “We should not think about those as opposing goals,” she said, and the cost-benefit tradeoff from policy choices does not need to be as steep as it is being framed. She also said it is important to think not only about the health emergency and economic reactivation phases, but also about a longer-term rebuilding phase that addresses the structural weaknesses that have been exposed in the pandemic.

Isabel Guerrero

Isabel Guerrero emphasized that the pandemic has been a moving target that requires an adaptive response. There are no best practices, she said; “it needs a lot of co creation with the community on what works.” She argued that a top- down approach doesn’t work in such a fluid crisis and pointed to the successful response by some countries to the Ebola virus outbreak in which “governments were smart enough to reach out to community organizations” that helped meet challenges including getting services the last mile to reach victims. In India, she said, social enterprise organizations stepped in and helped farmers by distribution food and buying up excess crops that couldn’t otherwise get to markets in the lockdown.

Rema Hanna said the pandemic is prompting nations to develop new ways to bring people together and strengthen their economies at a time of immense uncertainty. These innovations in turn force researchers and policymakers to develop new ways of thinking about public policy. She said that in such a downturn there is a need for increased spending and social protection even as tax revenues have declined. “We are in a situation where we have to think about this tradeoff,” Hanna said. A key to making these assessments successfully is finding reliable evidence. One example: gathering evidence to assess the value of cash transfer programs requires engaging with communities to see how policy translates into action at the local level. Some research has had to shift from in-person contact to online and mobile phone surveys to collect data. Hanna has worked closely with officials in Indonesia, where local conditions vary greatly by state. The challenge becomes one of trying to move quickly to get data in real time—and “to make sure the work we are doing at HKS is relevant to the crisis at large.”

Isabel Guerrero Pulgar

Douglas Elmendorf

The Global Economy: on Track for Strong but Uneven Growth as COVID-19 Still Weighs

A year and a half since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy is poised to stage its most robust post-recession recovery in 80 years in 2021. But the rebound is expected to be uneven across countries, as major economies look set to register strong growth even as many developing economies lag.

Global growth is expected to accelerate to 5.6% this year, largely on the strength in major economies such as the United States and China. And while growth for almost every region of the world has been revised upward for 2021, many continue to grapple with COVID-19 and what is likely to be its long shadow. Despite this year’s pickup, the level of global GDP in 2021 is expected to be 3.2% below pre-pandemic projections, and per capita GDP among many emerging market and developing economies is anticipated to remain below pre-COVID-19 peaks for an extended period. As the pandemic continues to flare, it will shape the path of global economic activity.

The United States and China are each expected to contribute about one quarter of global growth in 2021. The U.S. economy has been bolstered by massive fiscal support, vaccination is expected to become widespread by mid-2021, and growth is expected to reach 6.8% this year, the fastest pace since 1984. China’s economy – which did not contract last year – is expected to grow a solid 8.5% and moderate as the country’s focus shifts to reducing financial stability risks.

Lasting Legacies

Growth among emerging market and developing economies is expected to accelerate to 6% this year, helped by increased external demand and higher commodity prices. However, the recovery of many countries is constrained by resurgences of COVID-19, uneven vaccination, and a partial withdrawal of government economic support measures. Excluding China, growth is anticipated to unfold at a more modest 4.4% pace. In the longer term, the outlook for emerging market and developing economies will likely be dampened by the lasting legacies of the pandemic – erosion of skills from lost work and schooling; a sharp drop in investment; higher debt burdens; and greater financial vulnerabilities. Growth among this group of economies is forecast to moderate to 4.7% in 2022 as governments gradually withdraw policy support.

Among low-income economies, where vaccination has lagged, growth has been revised lower to 2.9%. Setting aside the contraction last year, this would be the slowest pace of expansion in two decades. The group’s output level in 2022 is projected to be 4.9% lower than pre-pandemic projections. Fragile and conflict-affected low-income economies have been the hardest hit by the pandemic, and per capita income gains have been set back by at least a decade.

Regionally, the recovery is expected to be strongest in East Asia and the Pacific, largely due to the strength of China’s recovery. In South Asia, recovery has been hampered by serious renewed outbreaks of the virus in India and Nepal. The Middle East and North Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean are expected to post growth too shallow to offset the contraction of 2020. Sub-Saharan Africa’s recovery, while helped by spillovers from the global recovery, is expected to remain fragile given the slow pace of vaccination and delays to major investments in infrastructure and the extractives sector.

Uncertain Outlook

The June forecast assumes that advanced economies will achieve widespread vaccination of their populations and effectively contain the pandemic by the end of the year. Major emerging market and developing economies are anticipated to substantially reduce new cases. However, the outlook is subject to considerable uncertainty. A more persistent pandemic, a wave of corporate bankruptcies, financial stress, or even social unrest could derail the recovery. At the same time, more rapid success in stamping out COVID-19 and greater spillovers from advanced economy growth could generate more vigorous global growth.

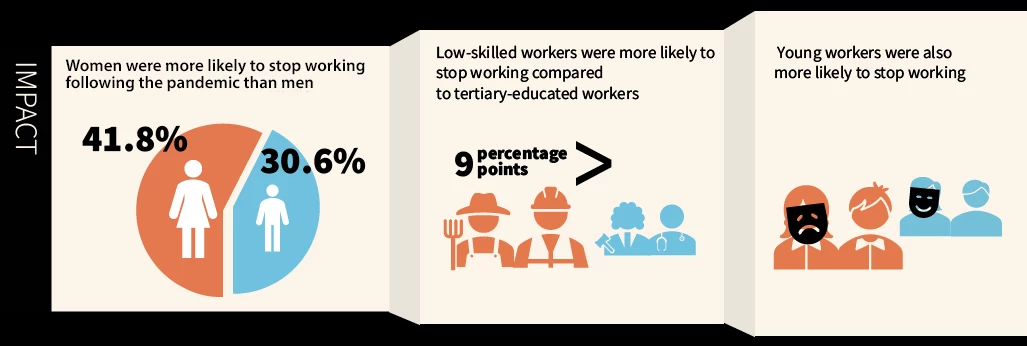

Even so, the pandemic is expected to have caused serious setbacks to development gains. Although per capita income growth is projected to be 4.9% among emerging market and developing economies this year, it is forecast to be essentially flat in low-income countries. Per capita income lost in 2020 will not be fully recouped by 2022 in about two-thirds of emerging market and developing economies, including three-quarters of fragile and conflict-affected low-income countries. By the end of this year, about 100 million people are expected to have fallen back into extreme poverty. These adverse impacts have been felt hardest by the most vulnerable groups – women, children, and unskilled and informal workers.

Global inflation, which has increased along with the economic recovery, is anticipated to continue to rise over the rest of the year; however, it is expected to remain within the target range for most countries. In those emerging market and developing economies in which inflation rises above target, this trend may not warrant a monetary policy response provided it is temporary and inflation expectations remain well-anchored.

Climbing Food Costs

Rising food prices and accelerating aggregate inflation may compound rising food insecurity in low-income countries. Policymakers should ensure that rising inflation rates do not lead to a de-anchoring of inflation expectations and resist using subsidies or price controls to reduce the burden of rising food prices, as these risk adding to high debt and creating further upward pressure on global agricultural prices.

A recovery in global trade after the recession last year offers an opportunity for emerging market and developing economies to bolster economic growth. Trade costs are on average one-half higher among emerging market and developing economies than advanced economies and lowering them could boost trade and stimulate investment and growth.

With relief from the pandemic tantalizingly close in many places but far from reach in others, policy actions will be critical. Securing equitable vaccine distribution will be essential to ending the pandemic. Far-reaching debt relief will be important to many low-income countries. Policymakers will need to nurture the economic recovery with fiscal and monetary measures while keeping a close eye on safeguarding financial stability. Policies should take the long view, reinvigorating human capital, expanding access to digital connectivity, and investing in green infrastructure to bolster growth along a green, resilient, and inclusive path.

It will take global coordination to end the pandemic through widespread vaccination and careful macroeconomic stewardship to avoid crises until we get there.

- Foreword by World Bank Group President David Malpass

- Report website

- Report download

- Press Release

- Blog: The Global Economic Outlook in five charts

- Download report data

- Download all charts (zip)

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

The Economic Impact of COVID-19 around the World

Working Paper 2022-030A by Fernando M. Martin, Juan M. Sánchez, and Olivia Wilkinson

For over two years, the world has been battling the health and economic consequences of the COVID‐19 pandemic. This paper provides an account of the worldwide economic impact of the COVID‐19 shock, measured by GDP growth, employment, government spending, monetary policy, and trade. We find that the COVID‐19 shock severely impacted output growth and employment in 2020, particularly in middle‐income countries. The government response, mainly consisting of increased expenditure, implied a rise in debt levels. Advanced countries, having easier access to credit markets, experienced the highest increase in indebtedness. All regions also relied on monetary policy to support the fiscal expansion. The specific circumstances surrounding the COVID‐19 shock implied that the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies did not put upward pressure on prices until 2021. We also find that the adverse effects of the COVID‐19 shock on output and prices have been significant and persistent, especially in emerging and developing countries.

Read Full Text

https://doi.org/10.20955/wp.2022.030

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Related Links

- Economist Pages

- JEL Classification System

- Fed In Print

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

- Get involved

Socio-economic impact

The UN’s Framework for the Immediate Socio-Economic Response to the COVID 19 Crisis warns that “The COVID-19 pandemic is far more than a health crisis: it is affecting societies and economies at their core. While the impact of the pandemic will vary from country to country, it will most likely increase poverty and inequalities at a global scale, making achievement of SDGs even more urgent.

Assessing the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on societies, economies and vulnerable groups is fundamental to inform and tailor the responses of governments and partners to recover from the crisis and ensure that no one is left behind in this effort.

Without urgent socio-economic responses, global suffering will escalate, jeopardizing lives and livelihoods for years to come. Immediate development responses in this crisis must be undertaken with an eye to the future. Development trajectories in the long-term will be affected by the choices countries make now and the support they receive.”

The United Nations has mobilized the full capacity of the UN system through its 131 country teams serving 162 countries and territories, to support national authorities in developing public health preparedness and response plans to the COVID-19 crisis.

Over the next 12 to 18 months, the socio-economic response will be one of one of three critical components of the UN’s COVID-19 response, alongside the health response, led by WHO, and the Global Humanitarian Response Plan.

As the technical lead for the socio-economic response, UNDP and its country offices worldwide are working under the leadership of the UN Resident Coordinators, and in close collaboration with specialized UN agencies, UN Regional Economic Commissions and IFIs, to assess the socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on economies and communities. The assessment reports available on this site contain the preliminary findings of regional and country analyses.

Massive production disruptions that started in China have led to a lower supply of goods and services that reduces overall hours worked, leading to lower incomes.

Briefs and Reports

Brief #2: Putting the UN Framework for Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19 into Action: Insights

Across the globe, the UN is supporting countries in preparing assessments of the socio-economic impacts of Covid-19. What are these assessments saying and what are the key socio-economic issues caused by the pandemic that the UN and its partners are seeing on the ground?

On behalf of the UN, UNDP prepares the monthly briefs Putting the UN Framework for Socio-Economic Response to Covid-19 Into Action exploring latest trends and providing key insights and analysis on the socio-economic impacts of Covid-19 on economies and societies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies

T. ibn-mohammed.

a Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG), The University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom

K.B. Mustapha

b Faculty of Engineering and Science, University of Nottingham (Malaysia Campus), Semenyih, Selangor43500, Malaysia

c School of The Built Environment and Architecture, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, United Kingdom

K.A. Babatunde

d Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Selangor43600, Malaysia

e Department of Economics, Faculty of Management Sciences, Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin, Nigeria

D.D. Akintade

f School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH United Kingdom

g Kent Business School, University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7PE, United Kingdom

h Faculty of Economics, Kyushu University, 744 Motooka, Nishi-ku, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan

M.M. Ndiaye

i Department of Industrial Engineering, College of Engineering, American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE

F.A. Yamoah

j Department of Management, Birkbeck University of London, London WC1E 7JL United Kingdom

k Sheffield University Management School (SUMS), The University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 1FL, United Kingdom

- • COVID-19 presents unprecedented challenge to all facets of human endeavour.

- • A critical review of the negative and positive impacts of the pandemic is presented.

- • The danger of relying on pandemic-driven benefits to achieving SDGs is highlighted.

- • The pandemic and its interplay with circular economy (CE) approaches is examined.

- • Sector-specific CE recommendations in a resilient post-COVID-19 world are outlined.

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on the 11th of March 2020, but the world is still reeling from its aftermath. Originating from China, cases quickly spread across the globe, prompting the implementation of stringent measures by world governments in efforts to isolate cases and limit the transmission rate of the virus. These measures have however shattered the core sustaining pillars of the modern world economies as global trade and cooperation succumbed to nationalist focus and competition for scarce supplies. Against this backdrop, this paper presents a critical review of the catalogue of negative and positive impacts of the pandemic and proffers perspectives on how it can be leveraged to steer towards a better, more resilient low-carbon economy. The paper diagnosed the danger of relying on pandemic-driven benefits to achieving sustainable development goals and emphasizes a need for a decisive, fundamental structural change to the dynamics of how we live. It argues for a rethink of the present global economic growth model, shaped by a linear economy system and sustained by profiteering and energy-gulping manufacturing processes, in favour of a more sustainable model recalibrated on circular economy (CE) framework. Building on evidence in support of CE as a vehicle for balancing the complex equation of accomplishing profit with minimal environmental harms, the paper outlines concrete sector-specific recommendations on CE-related solutions as a catalyst for the global economic growth and development in a resilient post-COVID-19 world.

1. Introduction

The world woke up to a perilous reality on the 11th of March, 2020 when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared novel coronavirus (COVID-19) a pandemic ( Sohrabi et al., 2020 ; WHO, 2020a ). Originating from Wuhan, China, cases rapidly spread to Japan, South Korea, Europe and the United States as it reached global proportions. Towards the formal pandemic declaration, substantive economic signals from different channels, weeks earlier, indicated the world was leaning towards an unprecedented watershed in our lifetime, if not in human history ( Gopinath, 2020 ). In series of revelatory reports ( Daszak, 2012 ; Ford et al., 2009 ; Webster, 1997 ), experts across professional cadres had long predicted a worldwide pandemic would strain the elements of the global supply chains and demands, thereby igniting a cross-border economic disaster because of the highly interconnected world we now live in. By all accounts, the emerging havoc wrought by the pandemic exceeded the predictions in those commentaries. At the time of writing, the virus has killed over 800,000 people worldwide ( JHU, 2020 ), disrupted means of livelihoods, cost trillions of dollars while global recession looms ( Naidoo and Fisher, 2020 ). In efforts to isolate cases and limit the transmission rate of the virus, while mitigating the pandemic, countries across the globe implemented stringent measures such as mandatory national lockdown and border closures.

These measures have shattered the core sustaining pillars of modern world economies. Currently, the economic shock arising from this pandemic is still being weighed. Data remains in flux, government policies oscillate, and the killer virus seeps through nations, affecting production, disrupting supply chains and unsettling the financial markets ( Bachman, 2020 ; Sarkis et al., 2020 ). Viewed holistically, the emerging pieces of evidence indicate we are at a most consequential moment in history where a rethink of sustainable pathways for the planet has become pertinent. Despite this, the measures imposed by governments have also led to some “accidental” positive effects on the environment and natural ecosystems. As a result, going forward, a fundamental change to human bio-physical activities on earth now appears on the spectrum of possibility ( Anderson et al., 2020 ). However, as highlighted by Naidoo and Fisher (2020) , our reliance on globalization and economic growth as drivers of green investment and sustainable development is no longer realistic. The adoption of circular economy (CE) – an industrial economic model that satisfies the multiple roles of decoupling of economic growth from resource consumption, waste management and wealth creation – has been touted to be a viable solution.

No doubt, addressing the public health consequences of COVID-19 is the top priority, but the nature of the equally crucial economic recovery efforts necessitates some key questions as governments around the world introduce stimulus packages to aid such recovery endeavours: Should these packages focus on avenues to economic recovery and growth by thrusting business as usual into overdrive or could they be targeted towards constructing a more resilient low-carbon CE? To answer this question, this paper builds on the extant literature on public health, socio-economic and environmental dimensions of COVID-19 impacts ( Gates, 2020b ; Guerrieri et al., 2020 ; Piguillem and Shi, 2020 ; Sohrabi et al., 2020 ), and examines its interplay with CE approaches. It argues for the recalibration and a rethink of the present global economic growth model, shaped by a linear economy system and sustained by profit-before-planet and energy-intensive manufacturing processes, in favour of CE. Building on evidence in support of CE as a vehicle for optimizing the complex equation of accomplishing profit while minimizing environmental damage, the paper outlines tangible sector-specific recommendations on CE-related solutions as a catalyst for the global economic boom in a resilient post-COVID-19 world. It is conceived that the “accidental” or the pandemic-induced CE strategies and behavioural changes that ensued during coronavirus crisis can be leveraged or locked in, to provide opportunities for both future resilience and competitiveness.

In light of the above, the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 , the methodological framework, which informed the critical literature review is presented. A brief overview of the historical context of previous epidemics and pandemics is presented in Section 3 as a requisite background on how pandemics have shaped human history and economies and why COVID-19 is different. In Section 4 , an overview of the impacts (both negative and positive) of COVID-19 in terms of policy frameworks, global economy, ecosystems and sustainability are presented. The role of the CE as a constructive change driver is detailed in Section 5 . In Section 6 , opportunities for CE after COVID-19 as well as sector-based recommendations on strategies and measures for advancing CE are presented, leading to the summary and concluding remarks in Section 7.

A literature review exemplifies a conundrum because an effective one cannot be conducted unless a problem statement is established ( Ibn-Mohammed, 2017 ). Yet, a literature search plays an integral role in establishing many research problems. In this paper, the approach taken to overcome this conundrum involves searching and reviewing the existing literature in the specific area of study (i.e. impacts of COVID-19 on global economy and ecosystems in the context of CE). This was used to develop the theoretical framework from which the current study emerges and adopting this to establish a conceptual framework which then becomes the basis of the current review. The paper adopts the critical literature review (CLR) approach given that it entails the assessment, critique and synthetisation of relevant literature regarding the topic under investigation in a manner that facilitates the emergence of new theoretical frameworks and perspectives from a wide array of different fields ( Snyder, 2019 ). CLR suffers from an inherent weakness in terms of subjectivity towards literature selection ( Snyder, 2019 ), prompting Grant and Booth (2009) to submit that systematic literature review (SLR) could mitigate this bias given its strict criteria in literature selection that facilitates a detailed analysis of a specific line of investigation. However, a number of authors ( Morrison et al., 2012 ; Paez, 2017 ) have reported that SLR does not allow for effective synthesis of academic and grey literature which are not indexed in popular academic search engines like Google Scholar, Web-of-Science and Scopus. The current review explores the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies, rather than investigating a specific aspect of the pandemic. As such, adopting a CLR approach is favoured in realising the goal of the paper as it allows for the inclusion of a wide range of perspectives and theoretical underpinnings from different sources ( Greenhalgh et al., 2018 ; Snyder, 2019 ).

Considering the above, this paper employed archival data consisting of journal articles, documented news in the media, expert reports, government and relevant stakeholders’ policy documents, published expert interviews and policy feedback literature that are relevant to COVID-19 and the concept of CE. To identify the relevant archival data, we focused on several practical ways of literature searching using appropriate keywords that are relevant to this work including impact (positive and negative) of COVID-19, circular economy, economic resilience, sustainability, supply chain resilience, climate change, etc. After identifying articles and relevant documents, their contents were examined to determine inclusions and exclusions based on their relevance to the topic under investigation. Ideas generated from reading the resulting papers from the search were then used to develop a theoretical framework and a research problem statement, which forms the basis for the CLR. The impact analysis for the study was informed by the I = P × A × T model whereby the “impact” (I) of any group or country on the environment is a function of the interaction of its population size (P), per capita affluence (A), expressed in terms of real per capita GDP, as a valid approximation of the availability of goods and services and technology (T) involved in supporting each unit of consumption.

As shown in the methodological framework in Fig. 1 , the paper starts with a brief review of the impacts of historical plagues to shed more light on the link between the past and the unprecedented time, which then led to an overview of the positive and negative impacts of COVID-19. The role of CE as a vehicle for constructive change in the light of COVID-19 was then explored followed by the synthesis, analysis and reflections on the information gathered during the review, leading to sector-specific CE strategy recommendations in a post-COVID-19 world.

Methodological framework for the critical literature review.

3. A brief account of the socio-economic impacts of historical outbreaks

At a minimum, pandemics result in the twin crisis of stressing the healthcare infrastructure and straining the economic system. However, beyond pandemics, several prior studies have long noted that depending on latency, transmission rate, and geographic spread, any form of communicable disease outbreak is a potent vector of localized economic hazards ( Bloom and Cadarette, 2019 ; Bloom and Canning, 2004 ; Hotez et al., 2014 ). History is littered with a catalogue of such outbreaks in the form of endemics, epidemics, plagues and pandemics. In many instances, some of these outbreaks have hastened the collapse of empires, overwhelmed the healthcare infrastructure, brought social unrest, triggered economic dislocations and exposed the fragility of the world economy, with a knock-on effect on many sectors. Indeed, in the initial few months of COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more evident that natural, accidental or intentional biological threats or outbreak in any country now poses an unquantifiable risk to global health and the world economy ( Bretscher et al., 2020 ).

Saunders-Hastings and Krewski (2016) reported that there have been several pandemics over the past 100 years. A short but inexhaustible list of outbreaks of communicable diseases include ‘the great plague’ ( Duncan-Jones, 1996 ; Littman and Littman, 1973 ), the Justinian plague ( Wagner et al., 2014 ), the Black Death ( Horrox, 2013 ), the Third Plague pandemic ( Bramanti et al., 2019 ; Tan et al., 2002 ), the Spanish flu ( Gibbs et al., 2001 ; Trilla et al., 2008 ), HIV/AIDS ( De Cock et al., 2012 ), SARS ( Lee and McKibbin, 2004 ), dengue ( Murray et al., 2013 ), and Ebola ( Baseler et al., 2017 ), among others. The potency of each of these outbreaks varies. Consequently, their economic implications differ according to numerous retrospective analyses ( Bloom and Cadarette, 2019 ; Bloom and Canning, 2004 ; Hotez et al., 2014 ). For instance, the Ebola epidemic of 2013-2016 created socio-economic impact to the tune of $53 billion across West Africa, plummeted Sierra Leone's GDP in 2015 by 20% and that of Liberia by 8% between 2013 and 2014, despite the decline in death rates across the same timeframe ( Fernandes, 2020 ).

As the world slipped into the current inflection point, some of the historical lessons from earlier pandemics remain salutary, even if the world we live in now significantly differs from those of earlier period ( McKee and Stuckler, 2020 ). Several factors differentiate the current socio-economic crisis of COVID-19 from the previous ones ( Baker et al., 2020 ), which means direct simple comparisons with past global pandemics are impossible ( Fernandes, 2020 ). Some of the differentiating factors include the fact that COVID-19 is a global pandemic and it is creating knock-on effects across supply chains given that the world has become much more integrated due to globalisation and advancements in technology ( McKenzie, 2020 ). Moreover, the world has witnessed advances in science, medicine and engineering. The modest number of air travellers during past pandemics delayed the global spread of the virus unlike now where global travel has increased tremendously. From an economic impact perspective, interest rates are at record lows and there is a great imbalance between demand and supply of commodities ( Fernandes, 2020 ). More importantly, many of the countries that are hard hit by the current pandemic are not exclusively the usual low-middle income countries, but those at the pinnacle of the pyramid of manufacturing and global supply chains. Against this backdrop, a review of the impact of COVID-19 is presented in the next section.

4. COVID-19: Policy frameworks, global economy, ecosystems and sustainability

4.1. evaluation of policy frameworks to combat covid-19.

The strategies and policies adopted by different countries to cope with COVID-19 have varied over the evolving severity and lifetime of the pandemic during which resources have been limited ( Siow et al., 2020 ). It is instructive that countries accounting for 65% of global manufacturing and exports (i.e. China, USA, Korea, Japan, France, Italy, and UK) were some of the hardest to be hit by COVID-19 ( Baldwin and Evenett, 2020 ). Given the level of unpreparedness and lack of resilience of hospitals, numerous policy emphases have gone into sourcing for healthcare equipment such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators ( Ranney et al., 2020 ) due to global shortages. For ventilators, in particular, frameworks for rationing them along with bed spaces have had to be developed to optimise their usage ( White and Lo, 2020 ). Other industries have also been affected, with shocks to their existence, productivity and profitability ( Danieli and Olmstead-Rumsey, 2020 ) including the CE-sensitive materials extraction and mining industries that have been hit by disruption to their operations and global prices of commodities ( Laing, 2020 ).

As highlighted in subsequent sub-sections, one of the psychological impacts of COVID-19 is panic buying ( Arafat et al., 2020 ), which happens due to uncertainties at national levels (e.g. for scarce equipment) and at individual levels (e.g. for everyday consumer products). In both instances, the fragility, profiteering and unsustainability of the existing supply chain model have been exposed ( Spash, 2020 ). In fact, Sarkis et al. (2020) questioned whether the global economy could afford to return to the just-in-time (JIT) supply chain framework favoured by the healthcare sector, given its apparent shortcomings in dealing with much needed supplies. The sub-section that follow examines some of the macro and micro economic ramifications of COVID-19.

4.1.1. Macroeconomic impacts: Global productions, exports, and imports

One challenge faced by the healthcare industry is that existing best practices, in countries like the USA (e.g. JIT macroeconomic framework), do not incentivise the stockpiling of essential medical equipment ( Solomon et al., 2020 ). Although vast sums were budgeted, some governments (e.g. UK, India and USA) needed to take extraordinary measures to protect their supply chain to the extent that manufacturers like Ford and Dyson ventured into the ventilator design/production market ( Iyengar et al., 2020 ). The US, in particular activated the Defense Production Act to compel car manufacturers to shift focus on ventilator production ( American Geriatrics Society, 2020 ; Solomon et al., 2020 ) due to the high cost and shortage of this vital equipment. Hospitals and suppliers in the US were also forced to enter the global market due to the chronic shortfall of N95 masks as well as to search for lower priced equipment ( Solomon et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, the global production of these specialist masks is thought to be led by China ( Baldwin and Evenett, 2020 ; Paxton et al., 2020 ) where COVID-19 broke out, with EU's supply primarily from Malaysia and Japan ( Stellinger et al., 2020 ). Such was the level of shortage that the US was accused of ‘pirating’ medical equipment supplies from Asian countries intended for EU countries ( Aubrecht et al., 2020 ).

France and Germany followed suit with similar in-ward looking policy and the EU itself imposed restrictions on the exportation of PPEs, putting many hitherto dependent countries at risk ( Bown, 2020 ). Unsurprisingly, China and the EU saw it fit to reduce or waive import tariffs on raw materials and PPE, respectively ( Stellinger et al., 2020 ). Going forward, the life-threatening consequences of logistics failures and misallocation of vital equipment and products could breathe new life and impetus to technologies like Blockchain, RFID and IoT for increased transparency and traceability ( Sarkis et al., 2020 ). Global cooperation and scenario planning will always be needed to complement these technologies. In this regard, the EU developed a joint procurement framework to reduce competition amongst member states, while in the US, where states had complained that federal might was used to interfere with orders, a ventilator exchange program was developed ( Aubrecht et al., 2020 ). However, even with trade agreements and cooperative frameworks, the global supply chain cannot depend on imports – or donations ( Evenett, 2020 ) for critical healthcare equipment and this realisation opens doors for localisation of production with consequences for improvements in environmental and social sustainability ( Baldwin and Evenett, 2020 ). This can be seen in the case of N95 masks which overnight became in such high demand that airfreights by private and commercial planes were used to deliver them as opposed to traditional container shipping ( Brown, 2020 ).

As detailed in forthcoming sections, a significant reduction in emissions linked to traditional shipping was observed, yet there was an increase in use of airfreighting due to desperation and urgency of demand. Nevertheless, several countries are having to rethink their global value chains ( Fig. 2 ) as a result of realities highlighted by COVID-19 pandemic ( Javorcik, 2020 ). This is primarily because national interests and protectionism have been a by-product of COVID-19 pandemic and also because many eastern European/Mediterranean countries have a relative advantage with respect to Chinese exports. As shown in Fig. 2 , the global export share which each of these countries has, relative to China's share of the same exports (x-axis) is measured against the economies of countries subscribing to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (y-axis). For each product, the ideal is to have a large circle towards the top right-hand corner of the chart.

A summary of how some Eastern European / Mediterranean countries have advantages over China on certain exports – based on the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System from 2018, where export volume is represented by dot sizes in millions of USD; Source: Javorcik (2020) .

4.1.2. Microeconomic impacts: Consumer behaviour

For long, there has been a mismatch between consumerist tendencies and biophysical realities ( Spash, 2020 ). However, COVID-19 has further exacerbated the need to reflect on the social impacts of individual lifestyles. The behaviour of consumers, in many countries, was at some point alarmist with a lot of panic buying of food and sanitary products ( Sim et al., 2020 ). At private level, consumer sentiment is also changing. Difficult access to goods and services has forced citizens to re-evaluate purchasing patterns and needs, with focus pinned on the most essential items ( Company, 2020 ; Lyche, 2020 ). Spash (2020) argued that technological obsolescence of modern products brought about by rapid innovation and individual consumerism is also likely to affect the linear economy model which sees, for instance, mobile phones having an average life time of four years (two years in the US), assuming their manufacture/repair services are constrained by economic shutdown and lockdowns ( Schluep, 2009 ). On the other hand, a sector like healthcare, which could benefit from mass production and consumerism of vital equipment, is plagued by patenting. Most medical equipment are patented and the issue of a 3D printer's patent infringement in Italy led to calls for ‘Open Source Ventilators’ and ‘Good Samaritan Laws’ to help deal with global health emergencies like COVID-19 ( Pearce, 2020 ). It is plausible that such initiatives/policies could help address the expensive, scarce, high-skill and material-intensive production of critical equipment, via cottage industry production.

For perspective, it should be noted that production capacity of PPE (even for the ubiquitous facemasks) have been shown by COVID-19 to be limited across many countries ( Dargaville et al., 2020 ) with some countries having to ration facemask production and distribution in factories ( San Juan, 2020 ). Unsurprisingly, the homemade facemask industry has not only emerged for the protection of mass populations as reported by Livingston et al. (2020) , it has become critical for addressing shortages ( Rubio-Romero et al., 2020 ) as well as being part of a post-lockdown exit strategy ( Allison et al., 2020 ). A revival of cottage industry production of equipment and basic but essential items like facemasks could change the landscape of global production for decades, probably leading to an attenuation of consumerist tendencies.This pandemic will also impact on R&D going forward, given the high likelihood that recession will cause companies to take short-term views, and cancel long and medium-term R&D in favour of short-term product development and immediate cash flow/profit as was certainly the case for automotive and aerospace sectors in previous recessions.

4.2. Overview of the negative impacts of COVID-19

The negative effects have ranged from a severe contraction of GDP in many countries to multi-dimensional environmental and social issues across the strata of society. In many respects, socio-economic activities came to a halt as: millions were quarantined; borders were shut; schools were closed; car/airline, manufacturing and travel industries crippled; trade fairs/sporting/entertainment events cancelled, and unemployment claims reached millions while the international tourist locations were deserted; and, nationalism and protectionism re-surfaced ( Baker et al., 2020 ; Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020 ; Devakumar et al., 2020 ; Kraemer et al., 2020 ; Thunstrom et al., 2020 ; Toquero, 2020 ). In the subsections that follow, an overview of some of these negative impacts on the global economy, environment, and society is presented.

4.2.1. Negative macroeconomic impact of COVID-19

Undoubtedly, COVID-19 first and foremost, constitutes a ferocious pandemic and a human tragedy that swept across the globe, resulting in a massive health crisis ( WHO, 2020b ), disproportionate social order ( UN DESA, 2020 ), and colossal economic loss ( IMF, 2020 ). It has created a substantial negative impact on the global economy, for which governments, firms and individuals scramble for adjustments ( Fernandes, 2020 ; Pinner et al., 2020 ; Sarkis et al., 2020 ; Sohrabi et al., 2020 ; Van Bavel et al., 2020 ). Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has distorted the world's operating assumptions, revealing the absolute lack of resilience of the dominant economic model to respond to unplanned shocks and crises ( Pinner et al., 2020 ). It has exposed the weakness of over-centralization of the complex global supply and production chains networks and the fragility of global economies, whilst highlighting weak links across industries( Fernandes, 2020 ; Guan et al., 2020 ; Sarkis et al., 2020 ). This has had a direct impact on employment and heightened the risk of food insecurity for millions due to lockdown and border restrictions ( Guerrieri et al., 2020 ). To some extent, some of the interventional measures introduced by governments across the world have resulted in the flattening of the COVID-19 curve (as shown in Fig. 3 ). This has helped in preventing healthcare systems from getting completely overwhelmed ( JHU, 2020 ), although as at the time of writing this paper, new cases are still being reported in different parts of the globe. Fernandes (2020) and McKibbin and Fernando (2020) reported thatthe socio-economic impact of COVID-19 will be felt for many months to come.

Daily confirmed new COVID-19 cases of the current 10 most affected countries based on a 5-day moving average. Valid as of August 31st, 2020 at 11:46 PM EDT ( JHU, 2020 ).

Guan et al. (2020) submitted that how badly and prolonged the recession rattles the world depends on how well and quickly the depth of the socio-economic implications of the pandemic is understood. IMF (2020) reported that in an unprecedented circumstance (except during the Great Depression), all economies including developed, emerging, and even developing will likely experience recession. In its April World Economic Outlook, IMF (2020) reversed its early global economic growth forecast from 3.3% to -3 %, an unusual downgrade of 6.3% within three months. This makes the pandemic a global economic shock like no other since the Great Depression and it has already surpassed the global financial crisis of 2009 as depicted in Fig. 4 . Economies in the advanced countries are expected to contract by -6.1% while recession in emerging and developing economies is projected (with caution) to be less adverse compared to the developed nations with China and India expected to record positive growth by the end of 2020. The cumulative GDP loss over the next year from COVID-19 could be around $9 trillion ( IMF, 2020 ).

Socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 lockdown: (a) Comparison of global economic recession due to COVID-19 and the 2009 global financial crisis; (b) Advanced economies, emerging and developing economies in recession; (c) the major economies in recession; (d) the cumulative economic output loss over 2020 and 2021. Note: Real GDP growth is used for economic growth, as year-on-year for per cent change ( IMF, 2020 ).

With massive job loss and excessive income inequality, global poverty is likely to increase for the first time since 1998 ( Mahler et al., 2020 ). It is estimated that around 49 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty due to COVID-19 with Sub-Sahara Africa projected to be hit hardest. The United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs concluded that COVID-19 pandemic may also increase exclusion, inequality, discrimination and global unemployment in the medium and long term, if not properly addressed using the most effective policy instruments ( UN DESA, 2020 ). The adoption of detailed universal social protection systems as a form of automatic stabilizers, can play a long-lasting role in mitigating the prevalence of poverty and protecting workers ( UN DESA, 2020 ).

4.2.2. Impact of COVID-19 on global supply chain and international trade

COVID-19 negatively affects the global economy by reshaping supply chains and sectoral activities. Supply chains naturally suffer from fragmentation and geographical dispersion. However, globalisation has rendered them more complex and interdependent, making them vulnerable to disruptions. Based on an analysis by the U.S. Institute for Supply Management, 75% of companies have reported disruptions in their supply chain ( Fernandes, 2020 ), unleashing crisis that emanated from lack of understanding and flexibility of the several layers of their global supply chains and lack of diversification in their sourcing strategies ( McKenzie, 2020 ). These disruptions will impact both exporting countries (i.e. lack of output for their local firms) and importing countries (i.e. unavailability of raw materials) ( Fernandes, 2020 ). Consequently, this will lead to the creation of momentary “manufacturing deserts” in which the output of a country, region or city drops significantly, turning into a restricted zone to source anything other than essentials like food items and drugs ( McKenzie, 2020 ). This is due to the knock-on effect of China's rising dominance and importance in the global supply chain and economy ( McKenzie, 2020 ). As a consequence of COVID-19, the World Trade Organization (WTO) projected a 32% decline in global trade ( Fernandes, 2020 ). For instance, global trade has witnessed a huge downturn due to reduced Chinese imports and the subsequent fall in global economic activities. This is evident because as of 25 th March 2020, global trade fell to over 4% contracting for only the second time since the mid-1980s ( McKenzie, 2020 ). Fig. 5 shows a pictorial representation of impact of pandemics on global supply chains based on different waves and threat levels.

Impact of pandemics on global supply chains. Adapted from Eaton and Connor (2020) .

4.2.3. Impact of COVID-19 on the aviation sector

The transportation sector is the hardest hit sector by COVID-19 due to the large-scale restrictions in mobility and aviation activities ( IEA, 2020 ; Le Quéré et al., 2020 ; Muhammad et al., 2020 ). In the aviation sector, for example, where revenue generation is a function of traffic levels, the sector has experienced flight cancellations and bans, leading to fewer flights and a corresponding immense loss in aeronautical revenues. This is even compounded by the fact that in comparison to other stakeholders in the aviation industry, when traffic demand declines, airports have limited avenues to reducing costs because the cost of maintaining and operating an airport remains the same and airports cannot relocate terminals and runaways or shutdown ( Hockley, 2020 ). Specifically, in terms of passenger footfalls in airports and planes, the Air Transport Bureau (2020) modelled the impact of COVID-19 on scheduled international passenger traffic for the full year 2020 under two scenarios namely Scenario 1 (the first sign of recovery in late May) and Scenario 2 (restart in the third quarter or later). Under Scenario 1, it estimated an overall reduction of: between 39%-56% of airplane seats; 872-1,303 million passengers, corresponding to a loss of gross operating revenues between ~$153 - $ 231 billion. Under Scenario 2, it predicted an overall drop of: between 49%-72% of airplane seats; 1,124 to 1,540 million passengers, with an equivalent loss of gross operating revenues between ~$198 - $ 273 billion. They concluded that the predicted impacts are a function of the duration and size of the pandemic and containment measures, the confidence level of customers for air travel, economic situations, and the pace of economic recovery ( Air Transport Bureau, 2020 ).

The losses incurred by the aviation industry require context and several other comparison-based predictions within the airline industry have also been reported. For instance, the International Civil Aviation Organization ICAO (2020) predicted an overall decline ininternational passengers ranging from 44% to 80% in 2020 compared to 2019. Airports Council International, ACI (2020) also forecasted a loss of two-fifths of passenger traffic and >$76 billion in airport revenues in 2020 in comparison to business as usual. Similarly, the International Air Transport Association IATA (2020) forecasted $113 billion in lost revenue and 48% drop in revenue passenger kilometres (RPKs) for both domestic and international routes ( Hockley, 2020 ). For pandemic scenario comparisons, Fig. 6 shows the impact of past disease outbreaks on aviation. As shown, the impact of COVID‐19 has already outstripped the 2003 SARS outbreak which had resulted in the reduction of annual RPKs by 8% and $6 billion revenues for Asia/Pacific airlines, for example. The 6‐month recovery path of SARS is, therefore, unlikely to be sufficient for the ongoing COVID-19 crisis ( Air Transport Bureau, 2020 ) but gives a backdrop and context for how airlines and their domestic/international markets may be impacted.

Impact of past disease outbreaks on aviation ( Air Transport Bureau, 2020 ).

Notably, these predictions are bad news for the commercial aspects of air travel (and jobs) but from the carbon/greenhouse gas emission and CE perspective, these reductions are enlightening and should force the airline industry to reflect on more environmentally sustainable models. However, the onus is also on the aviation industry to emphasise R&D on solutions that are CE-friendly (e.g. fuel efficiency; better use of catering wastes; end of service recycling of aircraft in sectors such as mass housing, or re-integrating airplane parts into new supply chains) and not merely investigating ways to recoup lost revenue due to COVID-19.

4.2.4. Impact of COVID-19 on the tourism industry

Expectedly, the impact of COVID-19 on aviation has led to a knock-on effect on the tourismindustry, which is nowadays hugely dependent on air travel. For instance, the United Nation World Tourism Organization UNWTO (2020) reported a 22% fall in international tourism receipts of $80 billion in 2020, corresponding to a loss of 67 million international arrivals. Depending on how long the travel restictions and border closures last, current scenario modelling indicated falls between 58% to 78% in the arrival of international tourists, but the outlook remains hugely uncertain. The continuous existence of the travel restrictions could put between 100 to 120 million direct tourism-related jobs at risk. At the moment, COVID-19 has rendered the sector worst in the historical patterns of international tourism since 1950 with a tendency to halt a 10-year period of sustained growth since the last global economic recession ( UNWTO, 2020 ). It has also been projected that a drop of ~60% in international tourists will be experienced this year, reducing tourism's contribution to global GDP, while affecting countries whose economy relies on this sector ( Naidoo and Fisher, 2020 ). Fig. 7 depicts the impact of COVID-19 on tourism in Q1 of 2020 based on % change in international tourists’ arrivals between January and March.

The impact of COVID-19 on tourism in quarter 1of 2020. Provisional data but current as of 31st August 2020 ( UNWTO, 2020 ).

4.2.5. Impact of COVID-19 on sustainable development goals

In 2015, the United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the view to improve livelihood and the natural world by 2030, making all countries of the world to sign up to it. To succeed, the foundations of the SDGs were premised on two massive assumptions namely globalisation and sustained economic growth. However, COVID-19 has significantly hampered this assumption due to several factors already discussed. Indeed, COVID-19 has brought to the fore the fact that the SDGs as currently designed are not resilient to shocks imposed by pandemics. Prior to COVID-19, progress across the SDGs was slow. Naidoo and Fisher (2020) reported that two-thirds of the 169 targets will not be accomplished by 2030 and some may become counterproductive because they are either under threat due to this pandemic or not in a position to mitigate associated impacts.

4.3. Positive impact of COVID-19

In this section, we discussed some of the positive ramifications of COVID-19. Despite the many detrimental effects, COVID-19 has provoked some natural changes in behaviour and attitudes with positive influences on the planet. Nonetheless, to the extent that the trends discussed below were imposed by the pandemic, they also underscore a growing momentum for transforming business operations and production towards the ideal of the CE.

4.3.1. Improvements in air quality

Due to the COVID-19-induced lockdown, industrial activities have dropped, causing significant reductions in air pollution from exhaust fumes from cars, power plants and other sources of fuel combustion emissions in most cities across the globe, allowing for improved air quality ( Le Quéré et al., 2020 ; Muhammad et al., 2020 ). This is evident from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration ( NASA, 2020a ) and European Space Agency ( ESA, 2020 ) Earth Observatory pollution satellites showing huge reductions in air pollution over China and key cities in Europe as depicted in Fig. 8 . In China, for example, air pollution reduction of between 20-30% was achieved and a 20-year low concentration of airborne particles in India is observed; Rome, Milan, and Madrid experienced a fall of ~45%, with Paris recording a massive reduction of 54% ( NASA, 2020b ). In the same vein, the National Centre for Atmospheric Science, York University, reported that air pollutants induced by NO 2 fell significantly across large cities in the UK. Although Wang et al. (2020) reported that in certain parts of China, severe air pollution events are not avoided through the reduction in anthropogenic activities partially due to the unfavourable meteorological conditions. Nevertheless, these data are consistent with established accounts linking industrialization and urbanization with the negative alteration of the environment ( Rees, 2002 ).

The upper part shows the average nitrogen dioxide (NO 2 ) concentrations from January 1-20, 2020 to February 10-25, 2020, in China. While the lower half shows NO 2 concentrations over Europe from March 13 to April 13, 2020, compared to the March-April averaged concentrations from 2019 ( ESA, 2020 ; NASA, 2020a ).

The scenarios highlighted above reiterates the fact that our current lifestyles and heavy reliance on fossil fuel-based transportation systems have significant consequences on the environment and by extension our wellbeing. It is this pollution that was, over time, responsible for a scourge of respiratory diseases, coronary heart diseases, lung cancer, asthma etc.( Mabahwi et al., 2014 ), rendering plenty people to be more susceptible to the devastating effects of the coronavirus ( Auffhammer et al., 2020 ). Air pollution constitutes a huge environmental threat to health and wellbeing. In the UK for example, between ~28,000 to ~36,000 deaths/year was linked to long-term exposure to air pollutants ( PHE, 2020 ). However, the reduction in air pollution with the corresponding improvements in air quality over the lockdown period has been reported to have saved more lives than already caused by COVID-19 in China ( Auffhammer et al., 2020 ).

4.3.2. Reduction in environmental noise

Alongside this reduction in air pollutants is a massive reduction in environmental noise. Environmental noise, and in particular road traffic noise, has been identified by the European Environment Agency, EEA (2020) to constitute a huge environmental problem affecting the health and well-being of several millions of people across Europe including distortion in sleep pattern, annoyance, and negative impacts on the metabolic and cardiovascular system as well as cognitive impairment in children. About 20% of Europe's population experiences exposure to long-term noise levels that are detrimental to their health. The EEA (2020) submitted that 48000new cases of ischaemic heart disease/year and ~12000 premature deaths are attributed to environmental noise pollution. Additionally, they reported that ~22 million people suffer chronic high annoyance alongside ~6.5 million people who experienceextreme high sleep disturbance. In terms of noise from aircraft, ~12500 schoolchildren were estimated to suffer from reading impairment in school. The impact of noise has long been underestimated, and although more premature deaths are associated with air pollution in comparison to noise, however noise constitutes a bigger impact on indicators of the quality of life and mental health ( EEA, 2020 ).