- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight

Wonderful discussion. and yes, homework helps in learning and building skills in students.

not true it just causes kids to stress

Homework can be both beneficial and unuseful, if you will. There are students who are gifted in all subjects in school and ones with disabilities. Why should the students who are gifted get the lucky break, whereas the people who have disabilities suffer? The people who were born with this “gift” go through school with ease whereas people with disabilities struggle with the work given to them. I speak from experience because I am one of those students: the ones with disabilities. Homework doesn’t benefit “us”, it only tears us down and put us in an abyss of confusion and stress and hopelessness because we can’t learn as fast as others. Or we can’t handle the amount of work given whereas the gifted students go through it with ease. It just brings us down and makes us feel lost; because no mater what, it feels like we are destined to fail. It feels like we weren’t “cut out” for success.

homework does help

here is the thing though, if a child is shoved in the face with a whole ton of homework that isn’t really even considered homework it is assignments, it’s not helpful. the teacher should make homework more of a fun learning experience rather than something that is dreaded

This article was wonderful, I am going to ask my teachers about extra, or at all giving homework.

I agree. Especially when you have homework before an exam. Which is distasteful as you’ll need that time to study. It doesn’t make any sense, nor does us doing homework really matters as It’s just facts thrown at us.

Homework is too severe and is just too much for students, schools need to decrease the amount of homework. When teachers assign homework they forget that the students have other classes that give them the same amount of homework each day. Students need to work on social skills and life skills.

I disagree.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what’s going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Homework is helpful because homework helps us by teaching us how to learn a specific topic.

As a student myself, I can say that I have almost never gotten the full 9 hours of recommended sleep time, because of homework. (Now I’m writing an essay on it in the middle of the night D=)

I am a 10 year old kid doing a report about “Is homework good or bad” for homework before i was going to do homework is bad but the sources from this site changed my mind!

Homeowkr is god for stusenrs

I agree with hunter because homework can be so stressful especially with this whole covid thing no one has time for homework and every one just wants to get back to there normal lives it is especially stressful when you go on a 2 week vaca 3 weeks into the new school year and and then less then a week after you come back from the vaca you are out for over a month because of covid and you have no way to get the assignment done and turned in

As great as homework is said to be in the is article, I feel like the viewpoint of the students was left out. Every where I go on the internet researching about this topic it almost always has interviews from teachers, professors, and the like. However isn’t that a little biased? Of course teachers are going to be for homework, they’re not the ones that have to stay up past midnight completing the homework from not just one class, but all of them. I just feel like this site is one-sided and you should include what the students of today think of spending four hours every night completing 6-8 classes worth of work.

Are we talking about homework or practice? Those are two very different things and can result in different outcomes.

Homework is a graded assignment. I do not know of research showing the benefits of graded assignments going home.

Practice; however, can be extremely beneficial, especially if there is some sort of feedback (not a grade but feedback). That feedback can come from the teacher, another student or even an automated grading program.

As a former band director, I assigned daily practice. I never once thought it would be appropriate for me to require the students to turn in a recording of their practice for me to grade. Instead, I had in-class assignments/assessments that were graded and directly related to the practice assigned.

I would really like to read articles on “homework” that truly distinguish between the two.

oof i feel bad good luck!

thank you guys for the artical because I have to finish an assingment. yes i did cite it but just thanks

thx for the article guys.

Homework is good

I think homework is helpful AND harmful. Sometimes u can’t get sleep bc of homework but it helps u practice for school too so idk.

I agree with this Article. And does anyone know when this was published. I would like to know.

It was published FEb 19, 2019.

Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college.

i think homework can help kids but at the same time not help kids

This article is so out of touch with majority of homes it would be laughable if it wasn’t so incredibly sad.

There is no value to homework all it does is add stress to already stressed homes. Parents or adults magically having the time or energy to shepherd kids through homework is dome sort of 1950’s fantasy.

What lala land do these teachers live in?

Homework gives noting to the kid

Homework is Bad

homework is bad.

why do kids even have homework?

Comments are closed.

Latest from Bostonia

When celtics star derrick white banged up his smile in the nba finals, this bu alum’s dental office fixed him up, rev. james lawson, crusading confidant of mlk, dies at 95, his first broadway show just earned this cfa alum a tony award nod, kyrie irving signs his dad—bu alum drederick irving—to his shoe line, opening doors: michele courton brown (cas’83), six bu alums to remember this memorial day, american academy of arts & sciences welcomes five bu members, com’s newest journalism grad took her time, could boston be the next city to impose congestion pricing, alum has traveled the world to witness total solar eclipses, opening doors: rhonda harrison (eng’98,’04, grs’04), campus reacts and responds to israel-hamas war, reading list: what the pandemic revealed, remembering com’s david anable, cas’ john stone, “intellectual brilliance and brilliant kindness”, one good deed: christine kannler (cas’96, sph’00, camed’00), william fairfield warren society inducts new members, spreading art appreciation, restoring the “black angels” to medical history, in the kitchen with jacques pépin.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

Trending Today

Spending Too Much Time on Homework Linked to Lower Test Scores

A new study suggests the benefits to homework peak at an hour a day. After that, test scores decline.

Samantha Larson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/58/e3587081-d161-4c6e-b4f9-a94b3520c60d/homework.jpg)

Polls show that American public high school teachers assign their students an average of 3.5 hours of homework a day . According to a recent study from the University of Oviedo in Spain, that’s far too much.

While doing some homework does indeed lead to higher test performance, the researchers found the benefits to hitting the books peak at about an hour a day. In surveying the homework habits of 7,725 adolescents, this study suggests that for students who average more than 100 minutes a day on homework, test scores start to decline. The relationship between spending time on homework and scoring well on a test is not linear, but curved.

This study builds upon previous research that suggests spending too much time on homework leads to higher stress, health problems and even social alienation. Which, paradoxically, means the most studious of students are in fact engaging in behavior that is counterproductive to doing well in school.

Because the adolescents surveyed in the new study were only tested once, the researchers point out that their results only indicate the correlation between test scores and homework, not necessarily causation. Co-author Javier Suarez-Alvarez thinks the most important findings have less to do with the amount of homework than with how that homework is done.

From Education Week :

Students who did homework more frequently – i.e., every day – tended to do better on the test than those who did it less frequently, the researchers found. And even more important was how much help students received on their homework – those who did it on their own preformed better than those who had parental involvement. (The study controlled for factors such as gender and socioeconomic status.)

“Once individual effort and autonomous working is considered, the time spent [on homework] becomes irrelevant,” Suarez-Alvarez says. After they get their daily hour of homework in, maybe students should just throw the rest of it to the dog.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Samantha Larson | | READ MORE

Samantha Larson is a freelance writer who particularly likes to cover science, the environment, and adventure. For more of her work, visit SamanthaLarson.com

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: August de Richelieu

Does homework still have value? A Johns Hopkins education expert weighs in

Joyce epstein, co-director of the center on school, family, and community partnerships, discusses why homework is essential, how to maximize its benefit to learners, and what the 'no-homework' approach gets wrong.

By Vicky Hallett

The necessity of homework has been a subject of debate since at least as far back as the 1890s, according to Joyce L. Epstein , co-director of the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University. "It's always been the case that parents, kids—and sometimes teachers, too—wonder if this is just busy work," Epstein says.

But after decades of researching how to improve schools, the professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Education remains certain that homework is essential—as long as the teachers have done their homework, too. The National Network of Partnership Schools , which she founded in 1995 to advise schools and districts on ways to improve comprehensive programs of family engagement, has developed hundreds of improved homework ideas through its Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program. For an English class, a student might interview a parent on popular hairstyles from their youth and write about the differences between then and now. Or for science class, a family could identify forms of matter over the dinner table, labeling foods as liquids or solids. These innovative and interactive assignments not only reinforce concepts from the classroom but also foster creativity, spark discussions, and boost student motivation.

"We're not trying to eliminate homework procedures, but expand and enrich them," says Epstein, who is packing this research into a forthcoming book on the purposes and designs of homework. In the meantime, the Hub couldn't wait to ask her some questions:

What kind of homework training do teachers typically get?

Future teachers and administrators really have little formal training on how to design homework before they assign it. This means that most just repeat what their teachers did, or they follow textbook suggestions at the end of units. For example, future teachers are well prepared to teach reading and literacy skills at each grade level, and they continue to learn to improve their teaching of reading in ongoing in-service education. By contrast, most receive little or no training on the purposes and designs of homework in reading or other subjects. It is really important for future teachers to receive systematic training to understand that they have the power, opportunity, and obligation to design homework with a purpose.

Why do students need more interactive homework?

If homework assignments are always the same—10 math problems, six sentences with spelling words—homework can get boring and some kids just stop doing their assignments, especially in the middle and high school years. When we've asked teachers what's the best homework you've ever had or designed, invariably we hear examples of talking with a parent or grandparent or peer to share ideas. To be clear, parents should never be asked to "teach" seventh grade science or any other subject. Rather, teachers set up the homework assignments so that the student is in charge. It's always the student's homework. But a good activity can engage parents in a fun, collaborative way. Our data show that with "good" assignments, more kids finish their work, more kids interact with a family partner, and more parents say, "I learned what's happening in the curriculum." It all works around what the youngsters are learning.

Is family engagement really that important?

At Hopkins, I am part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools , a research center that studies how to improve many aspects of education to help all students do their best in school. One thing my colleagues and I realized was that we needed to look deeply into family and community engagement. There were so few references to this topic when we started that we had to build the field of study. When children go to school, their families "attend" with them whether a teacher can "see" the parents or not. So, family engagement is ever-present in the life of a school.

My daughter's elementary school doesn't assign homework until third grade. What's your take on "no homework" policies?

There are some parents, writers, and commentators who have argued against homework, especially for very young children. They suggest that children should have time to play after school. This, of course is true, but many kindergarten kids are excited to have homework like their older siblings. If they give homework, most teachers of young children make assignments very short—often following an informal rule of 10 minutes per grade level. "No homework" does not guarantee that all students will spend their free time in productive and imaginative play.

Some researchers and critics have consistently misinterpreted research findings. They have argued that homework should be assigned only at the high school level where data point to a strong connection of doing assignments with higher student achievement . However, as we discussed, some students stop doing homework. This leads, statistically, to results showing that doing homework or spending more minutes on homework is linked to higher student achievement. If slow or struggling students are not doing their assignments, they contribute to—or cause—this "result."

Teachers need to design homework that even struggling students want to do because it is interesting. Just about all students at any age level react positively to good assignments and will tell you so.

Did COVID change how schools and parents view homework?

Within 24 hours of the day school doors closed in March 2020, just about every school and district in the country figured out that teachers had to talk to and work with students' parents. This was not the same as homeschooling—teachers were still working hard to provide daily lessons. But if a child was learning at home in the living room, parents were more aware of what they were doing in school. One of the silver linings of COVID was that teachers reported that they gained a better understanding of their students' families. We collected wonderfully creative examples of activities from members of the National Network of Partnership Schools. I'm thinking of one art activity where every child talked with a parent about something that made their family unique. Then they drew their finding on a snowflake and returned it to share in class. In math, students talked with a parent about something the family liked so much that they could represent it 100 times. Conversations about schoolwork at home was the point.

How did you create so many homework activities via the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program?

We had several projects with educators to help them design interactive assignments, not just "do the next three examples on page 38." Teachers worked in teams to create TIPS activities, and then we turned their work into a standard TIPS format in math, reading/language arts, and science for grades K-8. Any teacher can use or adapt our prototypes to match their curricula.

Overall, we know that if future teachers and practicing educators were prepared to design homework assignments to meet specific purposes—including but not limited to interactive activities—more students would benefit from the important experience of doing their homework. And more parents would, indeed, be partners in education.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

More From Forbes

Why homework doesn't seem to boost learning--and how it could.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Some schools are eliminating homework, citing research showing it doesn’t do much to boost achievement. But maybe teachers just need to assign a different kind of homework.

In 2016, a second-grade teacher in Texas delighted her students—and at least some of their parents—by announcing she would no longer assign homework. “Research has been unable to prove that homework improves student performance,” she explained.

The following year, the superintendent of a Florida school district serving 42,000 students eliminated homework for all elementary students and replaced it with twenty minutes of nightly reading, saying she was basing her decision on “solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students.”

Many other elementary schools seem to have quietly adopted similar policies. Critics have objected that even if homework doesn’t increase grades or test scores, it has other benefits, like fostering good study habits and providing parents with a window into what kids are doing in school.

Those arguments have merit, but why doesn’t homework boost academic achievement? The research cited by educators just doesn’t seem to make sense. If a child wants to learn to play the violin, it’s obvious she needs to practice at home between lessons (at least, it’s obvious to an adult). And psychologists have identified a range of strategies that help students learn, many of which seem ideally suited for homework assignments.

For example, there’s something called “ retrieval practice ,” which means trying to recall information you’ve already learned. The optimal time to engage in retrieval practice is not immediately after you’ve acquired information but after you’ve forgotten it a bit—like, perhaps, after school. A homework assignment could require students to answer questions about what was covered in class that day without consulting their notes. Research has found that retrieval practice and similar learning strategies are far more powerful than simply rereading or reviewing material.

One possible explanation for the general lack of a boost from homework is that few teachers know about this research. And most have gotten little training in how and why to assign homework. These are things that schools of education and teacher-prep programs typically don’t teach . So it’s quite possible that much of the homework teachers assign just isn’t particularly effective for many students.

Even if teachers do manage to assign effective homework, it may not show up on the measures of achievement used by researchers—for example, standardized reading test scores. Those tests are designed to measure general reading comprehension skills, not to assess how much students have learned in specific classes. Good homework assignments might have helped a student learn a lot about, say, Ancient Egypt. But if the reading passages on a test cover topics like life in the Arctic or the habits of the dormouse, that student’s test score may well not reflect what she’s learned.

The research relied on by those who oppose homework has actually found it has a modest positive effect at the middle and high school levels—just not in elementary school. But for the most part, the studies haven’t looked at whether it matters what kind of homework is assigned or whether there are different effects for different demographic student groups. Focusing on those distinctions could be illuminating.

A study that looked specifically at math homework , for example, found it boosted achievement more in elementary school than in middle school—just the opposite of the findings on homework in general. And while one study found that parental help with homework generally doesn’t boost students’ achievement—and can even have a negative effect— another concluded that economically disadvantaged students whose parents help with homework improve their performance significantly.

That seems to run counter to another frequent objection to homework, which is that it privileges kids who are already advantaged. Well-educated parents are better able to provide help, the argument goes, and it’s easier for affluent parents to provide a quiet space for kids to work in—along with a computer and internet access . While those things may be true, not assigning homework—or assigning ineffective homework—can end up privileging advantaged students even more.

Students from less educated families are most in need of the boost that effective homework can provide, because they’re less likely to acquire academic knowledge and vocabulary at home. And homework can provide a way for lower-income parents—who often don’t have time to volunteer in class or participate in parents’ organizations—to forge connections to their children’s schools. Rather than giving up on homework because of social inequities, schools could help parents support homework in ways that don’t depend on their own knowledge—for example, by recruiting others to help, as some low-income demographic groups have been able to do . Schools could also provide quiet study areas at the end of the day, and teachers could assign homework that doesn’t rely on technology.

Another argument against homework is that it causes students to feel overburdened and stressed. While that may be true at schools serving affluent populations, students at low-performing ones often don’t get much homework at all—even in high school. One study found that lower-income ninth-graders “consistently described receiving minimal homework—perhaps one or two worksheets or textbook pages, the occasional project, and 30 minutes of reading per night.” And if they didn’t complete assignments, there were few consequences. I discovered this myself when trying to tutor students in writing at a high-poverty high school. After I expressed surprise that none of the kids I was working with had completed a brief writing assignment, a teacher told me, “Oh yeah—I should have told you. Our students don’t really do homework.”

If and when disadvantaged students get to college, their relative lack of study skills and good homework habits can present a serious handicap. After noticing that black and Hispanic students were failing her course in disproportionate numbers, a professor at the University of North Carolina decided to make some changes , including giving homework assignments that required students to quiz themselves without consulting their notes. Performance improved across the board, but especially for students of color and the disadvantaged. The gap between black and white students was cut in half, and the gaps between Hispanic and white students—along with that between first-generation college students and others—closed completely.

There’s no reason this kind of support should wait until students get to college. To be most effective—both in terms of instilling good study habits and building students’ knowledge—homework assignments that boost learning should start in elementary school.

Some argue that young children just need time to chill after a long day at school. But the “ten-minute rule”—recommended by homework researchers—would have first graders doing ten minutes of homework, second graders twenty minutes, and so on. That leaves plenty of time for chilling, and even brief assignments could have a significant impact if they were well-designed.

But a fundamental problem with homework at the elementary level has to do with the curriculum, which—partly because of standardized testing— has narrowed to reading and math. Social studies and science have been marginalized or eliminated, especially in schools where test scores are low. Students spend hours every week practicing supposed reading comprehension skills like “making inferences” or identifying “author’s purpose”—the kinds of skills that the tests try to measure—with little or no attention paid to content.

But as research has established, the most important component in reading comprehension is knowledge of the topic you’re reading about. Classroom time—or homework time—spent on illusory comprehension “skills” would be far better spent building knowledge of the very subjects schools have eliminated. Even if teachers try to take advantage of retrieval practice—say, by asking students to recall what they’ve learned that day about “making comparisons” or “sequence of events”—it won’t have much impact.

If we want to harness the potential power of homework—particularly for disadvantaged students—we’ll need to educate teachers about what kind of assignments actually work. But first, we’ll need to start teaching kids something substantive about the world, beginning as early as possible.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Study: Homework Doesn’t Mean Better Grades, But Maybe Better Standardized Test Scores

Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at UVA's Curry School of Education

The time students spend on math and science homework doesn’t necessarily mean better grades, but it could lead to better performance on standardized tests, a new study finds.

“When Is Homework Worth The Time?” was recently published by lead investigator Adam Maltese, assistant professor of science education at Indiana University, and co-authors Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education , and Xitao Fan, dean of education at the University of Macau. Maltese is a Curry alumnus, and Fan is a former Curry faculty member.

The authors examined survey and transcript data of more than 18,000 10th-grade students to uncover explanations for academic performance. The data focused on individual classes, examining student outcomes through the transcripts from two nationwide samples collected in 1990 and 2002 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

Contrary to much published research, a regression analysis of time spent on homework and the final class grade found no substantive difference in grades between students who complete homework and those who do not. But the analysis found a positive association between student performance on standardized tests and the time they spent on homework.

“Our results hint that maybe homework is not being used as well as it could be,” Maltese said.

Tai said that homework assignments cannot replace good teaching.

“I believe that this finding is the end result of a chain of unfortunate educational decisions, beginning with the content coverage requirements that push too much information into too little time to learn it in the classroom,” Tai said. “The overflow typically results in more homework assignments. However, students spending more time on something that is not easy to understand or needs to be explained by a teacher does not help these students learn and, in fact, may confuse them.

“The results from this study imply that homework should be purposeful,” he added, “and that the purpose must be understood by both the teacher and the students.”

The authors suggest that factors such as class participation and attendance may mitigate the association of homework to stronger grade performance. They also indicate the types of homework assignments typically given may work better toward standardized test preparation than for retaining knowledge of class material.

Maltese said the genesis for the study was a concern about whether a traditional and ubiquitous educational practice, such as homework, is associated with students achieving at a higher level in math and science. Many media reports about education compare U.S. students unfavorably to high-achieving math and science students from across the world. The 2007 documentary film “Two Million Minutes” compared two Indiana students to students in India and China, taking particular note of how much more time the Indian and Chinese students spent on studying or completing homework.

“We’re not trying to say that all homework is bad,” Maltese said. “It’s expected that students are going to do homework. This is more of an argument that it should be quality over quantity. So in math, rather than doing the same types of problems over and over again, maybe it should involve having students analyze new types of problems or data. In science, maybe the students should write concept summaries instead of just reading a chapter and answering the questions at the end.”

This issue is particularly relevant given that the time spent on homework reported by most students translates into the equivalent of 100 to 180 50-minute class periods of extra learning time each year.

The authors conclude that given current policy initiatives to improve science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, education, more evaluation is needed about how to use homework time more effectively. They suggest more research be done on the form and function of homework assignments.

“In today’s current educational environment, with all the activities taking up children’s time both in school and out of school, the purpose of each homework assignment must be clear and targeted,” Tai said. “With homework, more is not better.”

Media Contact

Rebecca P. Arrington

Office of University Communications

[email protected] (434) 924-7189

Article Information

November 20, 2012

/content/study-homework-doesn-t-mean-better-grades-maybe-better-standardized-test-scores

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

School of Education

School of education study: homework doesn’t improve course grades but could boost standardized test scores.

Thursday, November 15, 2012

School of Education resources and social media channels

- SOE Intranet

Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

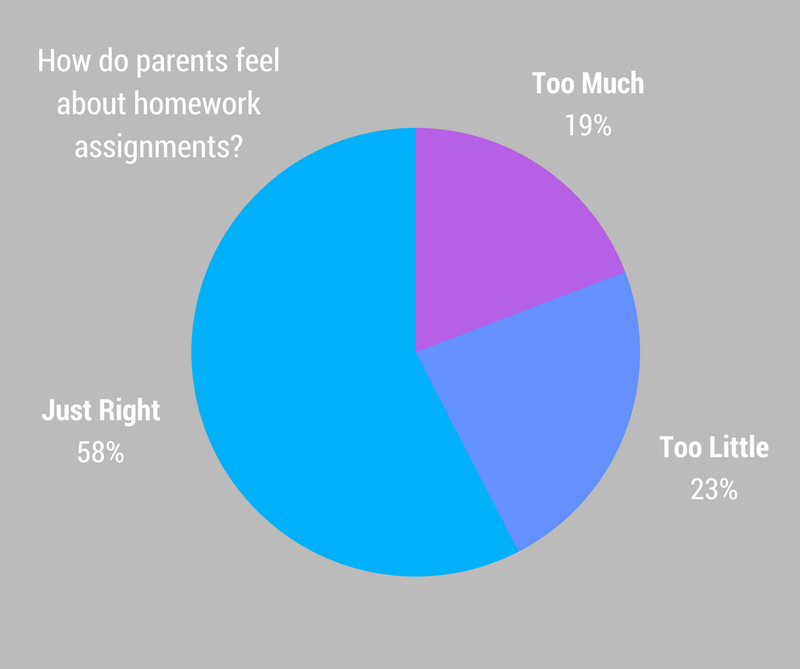

Educators should be thrilled by these numbers. Pleasing a majority of parents regarding homework and having equal numbers of dissenters shouting "too much!" and "too little!" is about as good as they can hope for.

But opinions cannot tell us whether homework works; only research can, which is why my colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students' scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. Students assigned homework in 2nd grade did better on math, 3rd and 4th graders did better on English skills and vocabulary, 5th graders on social studies, 9th through 12th graders on American history, and 12th graders on Shakespeare.

Less authoritative are 12 studies that link the amount of homework to achievement, but control for lots of other factors that might influence this connection. These types of studies, often based on national samples of students, also find a positive link between time on homework and achievement.

Yet other studies simply correlate homework and achievement with no attempt to control for student differences. In 35 such studies, about 77 percent find the link between homework and achievement is positive. Most interesting, though, is these results suggest little or no relationship between homework and achievement for elementary school students.

Why might that be? Younger children have less developed study habits and are less able to tune out distractions at home. Studies also suggest that young students who are struggling in school take more time to complete homework assignments simply because these assignments are more difficult for them.

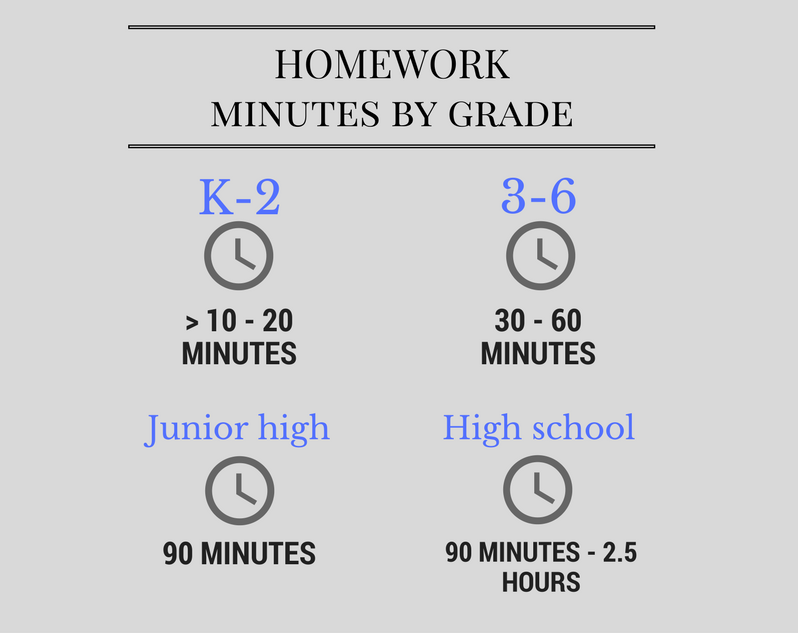

These recommendations are consistent with the conclusions reached by our analysis. Practice assignments do improve scores on class tests at all grade levels. A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2½ hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what's going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects. They argue it can lead to boredom with schoolwork, since all activities remain interesting only for so long. Homework can deny students access to leisure activities that also teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework -- pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques than the teacher.

My feeling is that homework policies should prescribe amounts of homework consistent with the research evidence, but which also give individual schools and teachers some flexibility to take into account the unique needs and circumstances of their students and families. In general, teachers should avoid either extreme.

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

Heavier Homework Load Linked to Lower Math, Science Performance, Study Says

- Share article

The optimal amount of homework for 13-year-old students is about an hour a day, a study published earlier this month in the Journal of Educational Psychology suggests. And spending too much time on homework is linked to a decrease in academic performance.

Researchers from the University of Oviedo administered surveys to 7,725 Spanish secondary school students, asking about how many days per week they did homework, how much time they spent on it, how much effort they put in, and how much help they received. The students also took a test with 24 math and 24 science questions.

Students who did homework more frequently—i.e., every day—tended to do better on the test than those who did it less frequently, the researchers found. And even more important was how much help students received on their homework—those who did it on their own performed better than those who had parental involvement. (The study controlled for factors such as gender and socioeconomic status.)

The researchers also found that prior knowledge—measured by previous letter grades—was a better predictor of test performance than any homework factor.

Regarding the amount of time students spent on homework, the results were a bit more complicated.

Overall, students spent on average between one and two hours a day doing homework from all subjects.

Those who spent about 90 to 100 minutes a day on homework scored highest on the assessment—however, they didn’t outperform their peers who spent less time on homework by much. The researchers therefore determined that going from 70 minutes of homework a day to 90 minutes a day is not an efficient use of time. “That small gain requires two hours more homework per week, which is a large time investment for such small gains,” they wrote. “For that reason, assigning more than 70 minutes homework per day does not seem very efficient, as the expectation of improved results is very low.”

And after 90 to 100 minutes of homework, they found, test scores declined. The relationship between minutes of homework and test scores is not linear, but curved.

“The key is that the optimum time is about 60 or 70 minutes [of homework] a day,” Javier Suarez-Alvarez, co-lead researcher on the study, said in an interview.

The study does, of course, come with some caveats. As the researchers note, the results are not causal; they only show a correlation between homework and test scores. Also, the survey did not distinguish between math and science homework. Suarez-Alvarez said the study also brings up questions about how factors like “academic intelligence, self-concept, and self-esteem” play into academic performance.

Even so, the study offers some insights that middle school teachers may find helpful. “Our data indicate that it is not necessary to assign huge quantities of homework, but it is important that assignment is systematic and regular, with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning,” the researchers write.

Or as Suarez-Alvarez put it, “Maybe it’s more important how they do the homework than how much.”

Chart: From “Adolescents’ Homework Performance in Mathematics and Science: Personal Factors and Teaching Practices,” Journal of Educational Psychology , March 16, 2015.

A version of this news article first appeared in the Curriculum Matters blog.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Gray Matters: What role should homework play in learning?