16 Personal Essays About Mental Health Worth Reading

Here are some of the most moving and illuminating essays published on BuzzFeed about mental illness, wellness, and the way our minds work.

BuzzFeed Staff

1. My Best Friend Saved Me When I Attempted Suicide, But I Didn’t Save Her — Drusilla Moorhouse

"I was serious about killing myself. My best friend wasn’t — but she’s the one who’s dead."

2. Life Is What Happens While You’re Googling Symptoms Of Cancer — Ramona Emerson

"After a lifetime of hypochondria, I was finally diagnosed with my very own medical condition. And maybe, in a weird way, it’s made me less afraid to die."

3. How I Learned To Be OK With Feeling Sad — Mac McClelland

"It wasn’t easy, or cheap."

4. Who Gets To Be The “Good Schizophrenic”? — Esmé Weijun Wang

"When you’re labeled as crazy, the “right” kind of diagnosis could mean the difference between a productive life and a life sentence."

5. Why Do I Miss Being Bipolar? — Sasha Chapin

"The medication I take to treat my bipolar disorder works perfectly. Sometimes I wish it didn’t."

6. What My Best Friend And I Didn’t Learn About Loss — Zan Romanoff

"When my closest friend’s first baby was stillborn, we navigated through depression and grief together."

7. I Can’t Live Without Fear, But I Can Learn To Be OK With It — Arianna Rebolini

"I’ve become obsessively afraid that the people I love will die. Now I have to teach myself how to be OK with that."

8. What It’s Like Having PPD As A Black Woman — Tyrese Coleman

"It took me two years to even acknowledge I’d been depressed after the birth of my twin sons. I wonder how much it had to do with the way I had been taught to be strong."

9. Notes On An Eating Disorder — Larissa Pham

"I still tell my friends I am in recovery so they will hold me accountable."

10. What Comedy Taught Me About My Mental Illness — Kate Lindstedt

"I didn’t expect it, but stand-up comedy has given me the freedom to talk about depression and anxiety on my own terms."

11. The Night I Spoke Up About My #BlackSuicide — Terrell J. Starr

"My entire life was shaped by violence, so I wanted to end it violently. But I didn’t — thanks to overcoming the stigma surrounding African-Americans and depression, and to building a community on Twitter."

12. Knitting Myself Back Together — Alanna Okun

"The best way I’ve found to fight my anxiety is with a pair of knitting needles."

13. I Started Therapy So I Could Take Better Care Of Myself — Matt Ortile

"I’d known for a while that I needed to see a therapist. It wasn’t until I felt like I could do without help that I finally sought it."

14. I’m Mending My Broken Relationship With Food — Anita Badejo

"After a lifetime struggling with disordered eating, I’m still figuring out how to have a healthy relationship with my body and what I feed it."

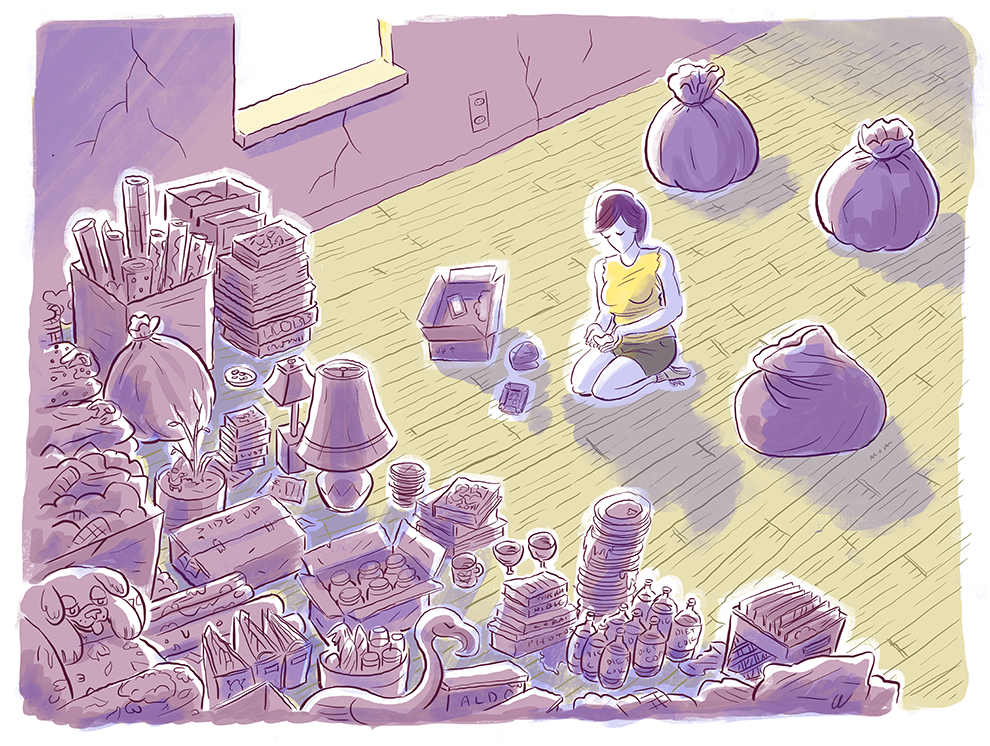

15. I Found Love In A Hopeless Mess — Kate Conger

"Dehoarding my partner’s childhood home gave me a way to understand his mother, but I’m still not sure how to live with the habit he’s inherited."

16. When Taking Anxiety Medication Is A Revolutionary Act — Tracy Clayton

"I had to learn how to love myself enough to take care of myself. It wasn’t easy."

Topics in this article

- Mental Health

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Importance of Mental Health

Elizabeth is a freelance health and wellness writer. She helps brands craft factual, yet relatable content that resonates with diverse audiences.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Beth-Plumptre-1000-6a0f2d14202a47fc8c1ec0d21a3e4e4f.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Westend61 / Getty Images

Risk Factors for Poor Mental Health

Signs of mental health problems, benefits of good mental health, how to maintain mental health and well-being.

Your mental health is an important part of your well-being. This aspect of your welfare determines how you’re able to operate psychologically, emotionally, and socially among others.

Considering how much of a role your mental health plays in each aspect of your life, it's important to guard and improve psychological wellness using appropriate measures.

Because different circumstances can affect your mental health, we’ll be highlighting risk factors and signs that may indicate mental distress. But most importantly, we’ll dive into all of the benefits of having your mental health in its best shape.

Mental health is described as a state of well-being where a person is able to cope with the normal stresses of life. This state permits productive work output and allows for meaningful contributions to society.

However, different circumstances exist that may affect the ability to handle life’s curveballs. These factors may also disrupt daily activities, and the capacity to manage these changes.

The following factors, listed below, may affect mental well-being and could increase the risk of developing psychological disorders .

Childhood Abuse

When a child is subjected to physical assault, sexual violence, emotional abuse, or neglect while growing up, it can lead to severe mental and emotional distress.

Abuse increases the risk of developing mental disorders like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, or personality disorders.

Children who have been abused may eventually deal with alcohol and substance use issues. But beyond mental health challenges, child abuse may also lead to medical complications such as diabetes, stroke, and other forms of heart disease.

The Environment

A strong contributor to mental well-being is the state of a person’s usual environment . Adverse environmental circumstances can cause negative effects on psychological wellness.

For instance, weather conditions may influence an increase in suicide cases. Likewise, experiencing natural disasters firsthand can increase the chances of developing PTSD. In certain cases, air pollution may produce negative effects on depression symptoms.

In contrast, living in a positive social environment can provide protection against mental challenges.

Your biological makeup could determine the state of your well-being. A number of mental health disorders have been found to run in families and may be passed down to members.

These include conditions such as autism , attention deficit hyperactivity disorder , bipolar disorder , depression , and schizophrenia .

Your lifestyle can also impact your mental health. Smoking, a poor diet , alcohol consumption , substance use , and risky sexual behavior may cause psychological harm. These behaviors have been linked to depression.

When mental health is compromised, it isn’t always apparent to the individual or those around them. However, there are certain warning signs to look out for, that may signify negative changes for the well-being. These include:

- A switch in eating habits, whether over or undereating

- A noticeable reduction in energy levels

- Being more reclusive and shying away from others

- Feeling persistent despair

- Indulging in alcohol, tobacco, or other substances more than usual

- Experiencing unexplained confusion, anger, guilt, or worry

- Severe mood swings

- Picking fights with family and friends

- Hearing voices with no identifiable source

- Thinking of self-harm or causing harm to others

- Being unable to perform daily tasks with ease

Whether young or old, the importance of mental health for total well-being cannot be overstated. When psychological wellness is affected, it can cause negative behaviors that may not only affect personal health but can also compromise relationships with others.

Below are some of the benefits of good mental health.

A Stronger Ability to Cope With Life’s Stressors

When mental and emotional states are at peak levels, the challenges of life can be easier to overcome.

Where alcohol/drugs, isolation, tantrums, or fighting may have been adopted to manage relationship disputes, financial woes, work challenges, and other life issues—a stable mental state can encourage healthier coping mechanisms.

A Positive Self-Image

Mental health greatly correlates with personal feelings about oneself. Overall mental wellness plays a part in your self-esteem . Confidence can often be a good indicator of a healthy mental state.

A person whose mental health is flourishing is more likely to focus on the good in themselves. They will hone in on these qualities, and will generally have ambitions that strive for a healthy, happy life.

Healthier Relationships

If your mental health is in good standing, you might be more capable of providing your friends and family with quality time , affection , and support. When you're not in emotional distress, it can be easier to show up and support the people you care about.

Better Productivity

Dealing with depression or other mental health disorders can impact your productivity levels. If you feel mentally strong , it's more likely that you will be able to work more efficiently and provide higher quality work.

Higher Quality of Life

When mental well-being thrives, your quality of life may improve. This can give room for greater participation in community building. For example, you may begin volunteering in soup kitchens, at food drives, shelters, etc.

You might also pick up new hobbies , and make new acquaintances , and travel to new cities.

Because mental health is so important to general wellness, it’s important that you take care of your mental health.

To keep mental health in shape, a few introductions to and changes to lifestyle practices may be required. These include:

- Taking up regular exercise

- Prioritizing rest and sleep on a daily basis

- Trying meditation

- Learning coping skills for life challenges

- Keeping in touch with loved ones

- Maintaining a positive outlook on life

Another proven way to improve and maintain mental well-being is through the guidance of a professional. Talk therapy can teach you healthier ways to interact with others and coping mechanisms to try during difficult times.

Therapy can also help you address some of your own negative behaviors and provide you with the tools to make some changes in your own life.

A Word From Verywell

Your mental health state can have a profound impact on all areas of your life. If you're finding it difficult to address mental health concerns on your own, don't hesitate to seek help from a licensed therapist .

World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening our Response .

Lippard ETC, Nemeroff CB. The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders . Am J Psychiatry . 2020;177(1):20-36. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010020

Helbich M. Mental Health and Environmental Exposures: An Editorial. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2018;15(10):2207. Published 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102207

Helbich M. Mental Health and Environmental Exposures: An Editorial. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2018;15(10):2207. Published 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102207

National Institutes of Health. Common Genetic Factors Found in 5 Mental Disorders .

Zaman R, Hankir A, Jemni M. Lifestyle Factors and Mental Health . Psychiatr Danub . 2019;31(Suppl 3):217-220.

Medline Plus. What Is mental health? .

National Alliance on Mental Health. Why Self-Esteem Is Important for Mental Health .

By Elizabeth Plumptre Elizabeth is a freelance health and wellness writer. She helps brands craft factual, yet relatable content that resonates with diverse audiences.

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Mental Health Essay

Essay on Mental Health

According to WHO, there is no single 'official' definition of mental health. Mental health refers to a person's psychological, emotional, and social well-being; it influences what they feel and how they think, and behave. The state of cognitive and behavioural well-being is referred to as mental health. The term 'mental health' is also used to refer to the absence of mental disease.

Mental health means keeping our minds healthy. Mankind generally is more focused on keeping their physical body healthy. People tend to ignore the state of their minds. Human superiority over other animals lies in his superior mind. Man has been able to control life due to his highly developed brain. So, it becomes very important for a man to keep both his body and mind fit and healthy. Both physical and mental health are equally important for better performance and results.

Importance of Mental Health

An emotionally fit and stable person always feels vibrant and truly alive and can easily manage emotionally difficult situations. To be emotionally strong, one has to be physically fit too. Although mental health is a personal issue, what affects one person may or may not affect another; yet, several key elements lead to mental health issues.

Many emotional factors have a significant effect on our fitness level like depression, aggression, negative thinking, frustration, and fear, etc. A physically fit person is always in a good mood and can easily cope up with situations of distress and depression resulting in regular training contributing to a good physical fitness standard.

Mental fitness implies a state of psychological well-being. It denotes having a positive sense of how we feel, think, and act, which improves one’s ability to enjoy life. It contributes to one’s inner ability to be self-determined. It is a proactive, positive term and forsakes negative thoughts that may come to mind. The term mental fitness is increasingly being used by psychologists, mental health practitioners, schools, organisations, and the general population to denote logical thinking, clear comprehension, and reasoning ability.

Negative Impact of Mental Health

The way we physically fall sick, we can also fall sick mentally. Mental illness is the instability of one’s health, which includes changes in emotion, thinking, and behaviour. Mental illness can be caused due to stress or reaction to a certain incident. It could also arise due to genetic factors, biochemical imbalances, child abuse or trauma, social disadvantage, poor physical health condition, etc. Mental illness is curable. One can seek help from the experts in this particular area or can overcome this illness by positive thinking and changing their lifestyle.

Regular fitness exercises like morning walks, yoga, and meditation have proved to be great medicine for curing mental health. Besides this, it is imperative to have a good diet and enough sleep. A person needs 7 to 9 hours of sleep every night on average. When someone is tired yet still can't sleep, it's a symptom that their mental health is unstable. Overworking oneself can sometimes result in not just physical tiredness but also significant mental exhaustion. As a result, people get insomnia (the inability to fall asleep). Anxiety is another indicator.

There are many symptoms of mental health issues that differ from person to person and among the different kinds of issues as well. For instance, panic attacks and racing thoughts are common side effects. As a result of this mental strain, a person may experience chest aches and breathing difficulties. Another sign of poor mental health is a lack of focus. It occurs when you have too much going on in your life at once, and you begin to make thoughtless mistakes, resulting in a loss of capacity to focus effectively. Another element is being on edge all of the time.

It's noticeable when you're quickly irritated by minor events or statements, become offended, and argue with your family, friends, or co-workers. It occurs as a result of a build-up of internal irritation. A sense of alienation from your loved ones might have a negative influence on your mental health. It makes you feel lonely and might even put you in a state of despair. You can prevent mental illness by taking care of yourself like calming your mind by listening to soft music, being more social, setting realistic goals for yourself, and taking care of your body.

Surround yourself with individuals who understand your circumstances and respect you as the unique individual that you are. This practice will assist you in dealing with the sickness successfully. Improve your mental health knowledge to receive the help you need to deal with the problem. To gain emotional support, connect with other people, family, and friends. Always remember to be grateful in life. Pursue a hobby or any other creative activity that you enjoy.

What does Experts say

Many health experts have stated that mental, social, and emotional health is an important part of overall fitness. Physical fitness is a combination of physical, emotional, and mental fitness. Emotional fitness has been recognized as the state in which the mind is capable of staying away from negative thoughts and can focus on creative and constructive tasks.

He should not overreact to situations. He should not get upset or disturbed by setbacks, which are parts of life. Those who do so are not emotionally fit though they may be physically strong and healthy. There are no gyms to set this right but yoga, meditation, and reading books, which tell us how to be emotionally strong, help to acquire emotional fitness.

Stress and depression can lead to a variety of serious health problems, including suicide in extreme situations. Being mentally healthy extends your life by allowing you to experience more joy and happiness. Mental health also improves our ability to think clearly and boosts our self-esteem. We may also connect spiritually with ourselves and serve as role models for others. We'd also be able to serve people without being a mental drain on them.

Mental sickness is becoming a growing issue in the 21st century. Not everyone receives the help that they need. Even though mental illness is common these days and can affect anyone, there is still a stigma attached to it. People are still reluctant to accept the illness of mind because of this stigma. They feel shame to acknowledge it and seek help from the doctors. It's important to remember that "mental health" and "mental sickness" are not interchangeable.

Mental health and mental illness are inextricably linked. Individuals with good mental health can develop mental illness, while those with no mental disease can have poor mental health. Mental illness does not imply that someone is insane, and it is not anything to be embarrassed by. Our society's perception of mental disease or disorder must shift. Mental health cannot be separated from physical health. They both are equally important for a person.

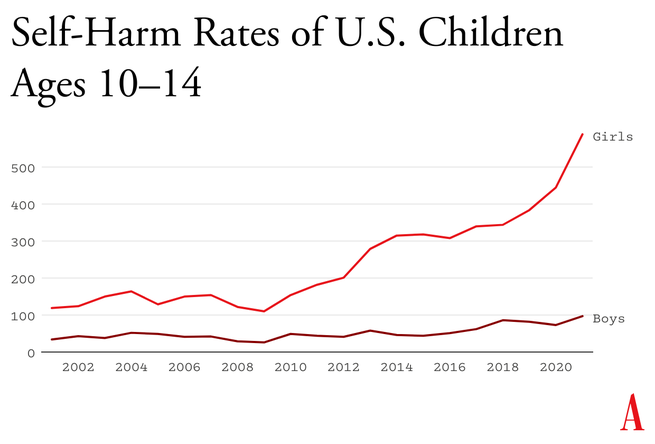

Our society needs to change its perception of mental illness or disorder. People have to remove the stigma attached to this illness and educate themselves about it. Only about 20% of adolescents and children with diagnosable mental health issues receive the therapy they need.

According to research conducted on adults, mental illness affects 19% of the adult population. Nearly one in every five children and adolescents on the globe has a mental illness. Depression, which affects 246 million people worldwide, is one of the leading causes of disability. If mental illness is not treated at the correct time then the consequences can be grave.

One of the essential roles of school and education is to protect boys’ and girls' mental health as teenagers are at a high risk of mental health issues. It can also impair the proper growth and development of various emotional and social skills in teenagers. Many factors can cause such problems in children. Feelings of inferiority and insecurity are the two key factors that have the greatest impact. As a result, they lose their independence and confidence, which can be avoided by encouraging the children to believe in themselves at all times.

To make people more aware of mental health, 10th October is observed as World Mental Health. The object of this day is to spread awareness about mental health issues around the world and make all efforts in the support of mental health.

The mind is one of the most powerful organs in the body, regulating the functioning of all other organs. When our minds are unstable, they affect the whole functioning of our bodies. Being both physically and emotionally fit is the key to success in all aspects of life. People should be aware of the consequences of mental illness and must give utmost importance to keeping the mind healthy like the way the physical body is kept healthy. Mental and physical health cannot be separated from each other. And only when both are balanced can we call a person perfectly healthy and well. So, it is crucial for everyone to work towards achieving a balance between mental and physical wellbeing and get the necessary help when either of them falters.

Mental Health Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on mental health.

Every year world mental health day is observed on October 10. It was started as an annual activity by the world federation for mental health by deputy secretary-general of UNO at that time. Mental health resources differ significantly from one country to another. While the developed countries in the western world provide mental health programs for all age groups. Also, there are third world countries they struggle to find the basic needs of the families. Thus, it becomes prudent that we are asked to focus on mental health importance for one day. The mental health essay is an insight into the importance of mental health in everyone’s life.

Mental Health

In the formidable years, this had no specific theme planned. The main aim was to promote and advocate the public on important issues. Also, in the first three years, one of the central activities done to help the day become special was the 2-hour telecast by the US information agency satellite system.

Mental health is not just a concept that refers to an individual’s psychological and emotional well being. Rather it’s a state of psychological and emotional well being where an individual is able to use their cognitive and emotional capabilities, meet the ordinary demand and functions in the society. According to WHO, there is no single ‘official’ definition of mental health.

Thus, there are many factors like cultural differences, competing professional theories, and subjective assessments that affect how mental health is defined. Also, there are many experts that agree that mental illness and mental health are not antonyms. So, in other words, when the recognized mental disorder is absent, it is not necessarily a sign of mental health.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

One way to think about mental health is to look at how effectively and successfully does a person acts. So, there are factors such as feeling competent, capable, able to handle the normal stress levels, maintaining satisfying relationships and also leading an independent life. Also, this includes recovering from difficult situations and being able to bounce back.

Important Benefits of Good Mental Health

Mental health is related to the personality as a whole of that person. Thus, the most important function of school and education is to safeguard the mental health of boys and girls. Physical fitness is not the only measure of good health alone. Rather it’s just a means of promoting mental as well as moral health of the child. The two main factors that affect the most are feeling of inferiority and insecurity. Thus, it affects the child the most. So, they lose self-initiative and confidence. This should be avoided and children should be constantly encouraged to believe in themselves.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

How to Start an Essay About Mental Health

Mental health is a topic that is gaining increasing attention in contemporary society. As societal awareness of mental health issues grows, so does the need for thoughtful and well-researched essays on this subject.

If you are looking to start an essay about mental health, it is important to approach the topic with sensitivity, knowledge, and a clear understanding of its significance. In this article, we will explore the key steps to successfully begin your essay on mental health.

Understanding the Importance of Mental Health

Mental health is an integral part of our overall well-being. It encompasses our emotional, psychological, and social well-being, affecting how we think, feel, and act. Despite its importance, mental health has historically been stigmatized and overlooked.

However, with growing awareness, the significance of mental health in our daily lives is increasingly recognized.

When we talk about mental health, we are referring to more than just the absence of mental illness. It is a state of well-being in which an individual can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively, and contribute to their community.

Mental health encompasses various aspects such as emotional stability, psychological resilience, and the ability to form and maintain meaningful relationships.

Understanding the complexities of mental health is crucial for promoting overall well-being. It is not a one-size-fits-all concept, as each person may experience mental health differently. Factors such as genetics, upbringing, life experiences, and social support systems all play a role in shaping an individual’s mental health.

Defining Mental Health

Before delving into the complexities of mental health, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of what it entails. Mental health refers to a state of well-being in which an individual can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively, and contribute to their community.

It encompasses various aspects such as emotional stability, psychological resilience, and the ability to form and maintain meaningful relationships.

Emotional stability is an essential component of mental health. It involves being able to recognize and manage our emotions effectively. This includes understanding our feelings, expressing them appropriately, and regulating our emotional responses to different situations.

Emotional stability allows us to navigate through life’s ups and downs with resilience and adaptability.

Psychological resilience is another crucial aspect of mental health. It refers to our ability to bounce back from adversity and cope with challenges effectively.

Resilience is not about avoiding difficulties but rather about developing the skills and mindset to navigate through them. It involves having a positive outlook, seeking support when needed, and finding healthy ways to cope with stress.

The ability to form and maintain meaningful relationships is also closely tied to mental health. Healthy relationships provide us with support, love, and a sense of belonging. They contribute to our overall well-being and help us navigate through life’s challenges. Building and nurturing relationships requires effective communication, empathy, and the ability to establish boundaries.

The Impact of Mental Health on Daily Life

It is important to highlight the profound impact mental health has on our daily lives. Untreated mental health conditions can hinder our ability to manage stress, maintain relationships, and perform well in our personal and professional endeavors.

Understanding how mental health affects individuals and society as a whole is crucial for raising awareness and fostering support for those experiencing mental health challenges.

When our mental health is compromised, it can affect our ability to cope with everyday stressors. Simple tasks may become overwhelming, and we may struggle to find joy and fulfillment in our daily lives. Mental health conditions can manifest in various ways, including anxiety, depression, mood swings, and difficulty concentrating.

Furthermore, mental health plays a significant role in our relationships. When we are struggling with our mental well-being, it can impact our ability to connect with others, communicate effectively, and maintain healthy boundaries. This can lead to strained relationships, feelings of isolation, and a decreased sense of belonging.

In the workplace, mental health is a crucial factor in our productivity and overall job satisfaction. When we are mentally healthy, we are better able to focus, make decisions, and handle stress effectively.

On the other hand, untreated mental health conditions can lead to decreased productivity, absenteeism, and difficulties in maintaining professional relationships.

Recognizing the impact of mental health on daily life is essential for promoting a supportive and inclusive society.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

Before you begin writing, it is essential to adequately prepare yourself. This involves choosing an appropriate topic and conducting preliminary research to establish a solid foundation for your essay.

Writing an essay on mental health can be a rewarding experience that allows you to delve into a topic that is both important and relevant in today’s society.

When selecting a topic, consider exploring areas such as the impact of mental health on different demographics, the role of stigma in mental health treatment, or the effectiveness of various therapeutic approaches.

Choosing Your Topic

When selecting a topic for your essay on mental health, consider areas that interest you or resonate with your personal experiences. This will ensure your essay reflects your passion and authenticity, making it a compelling read. It is also wise to choose a topic that is relevant and addresses current issues or trends in the field of mental health.

One possible topic could be exploring the impact of social media on mental health. In today’s digital age, social media has become an integral part of our lives, but it also has its drawbacks. By examining the potential negative effects of excessive social media use on mental well-being, you can shed light on an important issue that affects many individuals.

Another topic worth considering is the intersection of mental health and cultural diversity. By exploring how different cultural backgrounds and beliefs influence the perception and treatment of mental health, you can contribute to a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of this complex field.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Once you have chosen your topic, conduct preliminary research to familiarize yourself with the existing literature and perspectives in the field of mental health.

This will enable you to develop a well-informed and comprehensive essay. Utilize reputable sources such as scholarly articles, books, and reputable websites to gather accurate information and insights on your chosen topic.

Start by exploring academic databases that specialize in psychology and mental health research. These databases provide access to a wide range of scholarly articles and studies conducted by experts in the field. By reviewing the latest research findings, you can stay up-to-date with the current advancements and debates in mental health.

In addition to academic sources, consider consulting books written by renowned psychologists or mental health professionals. These books often provide a deeper understanding of specific topics and offer valuable insights based on years of research and clinical experience.

Furthermore, reputable websites such as government health agencies or mental health organizations can provide reliable information and resources. These organizations often publish reports, guidelines, and statistics that can support your arguments and provide a broader context for your essay.

Remember to critically evaluate the sources you come across during your research. Look for peer-reviewed articles, check the credentials of the authors, and consider the methodology used in the studies. By ensuring the credibility of your sources, you can strengthen the validity and reliability of your essay.

Crafting Your Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement is the backbone of every effective essay. It serves as a concise and well-articulated summary of the main argument or point you will be addressing throughout the essay.

When crafting your thesis statement, ensure that it is specific, arguable, and supported by evidence. A well-crafted thesis statement sets the tone for your essay and provides a roadmap for the reader.

Importance of a Strong Thesis

A strong thesis statement is essential as it condenses the main focus of your essay into a single sentence. It allows your readers to understand the purpose and direction of your essay from the outset.

A well-defined thesis also helps you maintain coherence and clarity throughout your writing, ensuring you stay on track and deliver a well-structured essay.

Tips for Writing a Compelling Thesis

When formulating your thesis statement, consider the following tips:

- Be specific and concise

- Avoid vague language

- Ensure your thesis is arguable

- Use strong language and avoid hedging

- Assert the main argument or point of your essay

- Support your thesis statement with evidence and examples

Outlining Your Essay

An essay outline serves as a roadmap for your writing and helps you organize your thoughts coherently. It provides structure and clarity, making the writing process smoother and increasing the overall coherence of your essay.

The Benefits of an Essay Outline

By creating an outline, you can:

- Organize your ideas logically

- Ensure a smooth flow of information

- Maintain coherence throughout your essay

- Identify any gaps or missing information

- Stay focused on your main argument or point

How to Create an Effective Outline

When creating an essay outline, break your essay into logical sections or paragraphs. Each section should focus on a particular aspect of mental health, supporting your thesis statement. Arrange your main points and supporting evidence in a logical and coherent manner, ensuring smooth transitions between paragraphs. A well-structured outline will serve as a guide throughout your writing process.

Writing the Introduction

The introduction is a crucial part of any essay as it sets the tone and captivates the reader’s attention. A compelling introduction encourages readers to engage with your essay and establishes the significance of mental health as a topic of discussion.

Grabbing the Reader’s Attention

Hook your readers from the beginning by using an attention-grabbing opening sentence or anecdote. This could be a startling statistic, a thought-provoking quote, or a short personal story. By immediately piquing your readers’ interest, you create a compelling reason for them to continue reading and delve further into your essay.

Introducing Your Thesis

After capturing the readers’ attention, smoothly transition into introducing your thesis statement. Clearly state your main argument or point and briefly outline the main components you will be discussing in your essay.

This will give the readers a sense of what to expect and ensure they understand the focus of your essay from the outset.In conclusion, starting an essay about mental health requires careful consideration and preparation.

In conclusion, starting an essay about mental health requires careful consideration and preparation. By understanding the importance of mental health, conducting preliminary research, crafting a strong thesis statement, outlining your essay, and writing a captivating introduction, you will set a solid foundation for a thoughtful and impactful essay on mental health.

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- Open access

- Published: 22 November 2012

Quality of life of people with mental health problems: a synthesis of qualitative research

- Janice Connell 1 ,

- John Brazier 2 ,

- Alicia O’Cathain 1 ,

- Myfanwy Lloyd-Jones 2 &

- Suzy Paisley 3

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes volume 10 , Article number: 138 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

93k Accesses

159 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

To identify the domains of quality of life important to people with mental health problems.

A systematic review of qualitative research undertaken with people with mental health problems using a framework synthesis.

We identified six domains: well-being and ill-being; control, autonomy and choice; self-perception; belonging; activity; and hope and hopelessness. Firstly, symptoms or ‘ill-being’ were an intrinsic aspect of quality of life for people with severe mental health problems. Additionally, a good quality of life was characterised by the feeling of being in control (particularly of distressing symptoms), autonomy and choice; a positive self-image; a sense of belonging; engagement in meaningful and enjoyable activities; and feelings of hope and optimism. Conversely, a poor quality life, often experienced by those with severe mental health difficulties, was characterized by feelings of distress; lack of control, choice and autonomy; low self-esteem and confidence; a sense of not being part of society; diminished activity; and a sense of hopelessness and demoralization.

Conclusions

Generic measures fail to address the complexity of quality of life measurement and the broad range of domains important to people with mental health problems.

Introduction

There has been a shift in mental health services from an emphasis on treatment focused on reducing symptoms, based on a narrow notion of health and disease, to a more holistic approach which takes into consideration both well-being and functioning [ 1 ]. Mental health services in the United Kingdom, for example, are now being planned and commissioned based on psychological formulations addressing a person’s wider well-being, need, and functional outcome alongside, or sometimes in place of, diagnostic categories and clinical ideas of cure and outcome [ 2 ]. At the same time, there has been an increasing use of generic measures of health related quality of life like EQ-5D and SF-36 in assessing the benefits of health care interventions in order to inform decisions about provision and reimbursement (eg National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) [ 3 ] and for assessing patient reported outcomes [ 4 ]. It is claimed these generic measures are appropriate for both physical and mental health conditions; however some argue they are not suitable for people with severe mental health problems, particularly psychosis [ 5 , 6 ].

One of the challenges of using the concept ‘quality of life’ as a basis for outcome measurement is that it can be defined, and therefore measured, in innumerable ways. The assumptions underlying such measurement can be influenced by both academic discipline and ideological perspective [ 7 ]. As a result there are many different overlapping models of quality of life including objective and subjective indicators, needs satisfaction, psychological and subjective well-being models, health, functioning and social models [ 8 ]. One on-going tension is whether a measure should have a subjective or objective orientation. A subjective orientation may emphasise the importance of ‘being’, which in turn can be viewed either in hedonistic terms as the experience of current happiness or pleasure, or as a more eudemonic approach which considers the more pervading attributes of self-fulfilment, realisation or actualization [ 9 , 10 ]. A subjective evaluative approach may also be taken which asks people to rate how satisfied they are with their lives and aspects of it [ 11 ]. On the other hand, a more objective approach used in social policy places its emphasis on meeting needs, whether they are healthy, have sufficient income for food and satisfactory living conditions, are well educated and have access to resources [ 9 , 12 ]. A review of eleven instruments for measuring quality of life for people with severe mental illness identified that the most commonly assessed domains are employment or work, health, leisure, living situation, and relationships [ 13 ]. These measures combine an objective with a subjective approach that establishes levels of satisfaction with these different objective life domains. However, concerns have been raised regarding the limited coverage of domains assessed in such instruments [ 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, it is criticised that measures have primarily been generated from the perspective of mental health professionals or other experts using a top-down approach rather than by an assessment of what individuals with mental health problems perceive to be important to their quality of life [ 15 ]. These are also important potential criticisms of the generic measures of health related quality of life like the EQ-5D and SF-36 [ 5 ].

The aim of this literature review was to examine the quality of life domains that are important from the perspective of an individual with mental health problems. This research was part of a larger project considering the applicability and suitability of generic health related quality of life measures for people with mental health problems (MRC project number G0801394).

We sought to identify all primary qualitative research studies (involving methods such as interviews and focus groups) which explicitly asked adults with mental health problems what they considered to be important to their quality of life or how their quality of life had been affected by their mental health problems.

A range of approaches is available for synthesizing qualitative research [ 16 ]. Paterson et al. [ 17 ] recommend that the choice is made on the basis of the nature of the research question and design, the prevailing paradigm, and the researcher’s personal preference. In this review, framework synthesis was used. This is based on the ‘framework’ approach for the analysis of primary data [ 18 ] and is a highly structured approach to organizing and analyzing data which permits the expansion and refinement of an a priori framework to incorporate new themes emerging from the data [ 16 ]. It is appropriate here because the aim of our wider study was to identify whether existing outcomes measures are useful for measuring quality of life for people with mental health problems.

Search methods

Systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness evidence require extensive searching based on a clearly focussed search question. Defining a focussed question was neither possible nor appropriate here because a pre-specified search question would have imposed on the search process an a priori conceptual understanding of the topic under review. Given the abstract nature of the relevant concepts and associated search vocabulary, and given the exploratory and inductive nature of the review process, we needed to use an iterative approach to searching. This incorporated a number of different search techniques including keyword searching, taking advice from experts, hand searching and citation searching of relevant references and world-wide-web searching. The iterative approach provided a means of accommodating within the search process new themes emerging from the review as the scope of our conceptual understanding developed. The identification of relevant search terms was an evolving process. Four search iterations were undertaken. The choice of search terms used in earlier iterations was based on our initial understanding of the review topic and on papers identified by experts at the outset of the review. The choice of search terms used in later iterations was informed by the review of evidence identified by earlier search iterations. Key terms included mental health; mental illness; mental disorder; quality of life; well-being; well being; life satisfaction; life functioning; life change; recovery; subjective experience; lived experience; lifestyle; coping; adaptation; qualitative; qualitative research. For a full list of search terms and details of the evolving search iterations see Additional file 1 : Appendix 1 and Additional file 2: Appendix 2. Database searches were undertaken between October 2009 and April 2010 and included Medline, ASSIA, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. The searches were not restricted by date, language or country.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Quality of life

The search started from a premise of not imposing a pre-conceived definition or model of ‘quality of life’. Whilst some studies retrieved had an explicit aim to explore quality of life we found other studies with very similar findings to those which explicitly examined the concept of quality of life even though quality of life was not the subject of investigation. These studies examined the concepts of: recovery, lived experience, subjective experience, psychosocial issues, health needs, and strategies for living. Complexities thus arose in deciding whether the studies were about the same substantive concept of quality of life or were tapping into a separate but overlapping concept. As Sandelowski [ 19 ] states ‘often research purposes and questions are so broadly stated it is only by looking at the kinds of findings produced that topical similarity can be determined’. We were aware of the danger that the inclusion of these studies could introduce themes that were not central to the concept of quality of life but were rather allied to a separate but related concept. A pragmatic decision was made to examine the research aims and interview questions of those studies which did not directly investigate the concept of quality of life and only include those which asked broad open-ended questions about how participants’ mental health affected their lives, what was important to or would improve their lives, or equated their findings with quality of life in some way. We excluded studies that deliberately started with a premise of the importance of any particular domain of quality of life or were structured solely around a pre-conceived list of domains.

Qualitative research

We included primary qualitative research studies that used qualitative interviews or focus groups data to identify the views of individuals with mental health problems. We excluded studies that used content analysis which presented results as a frequency list with no supporting participant quotes. Some studies sought the views of people with mental health problems and of carers or professionals; in such cases, we only included those studies in which the views of people with mental health problems could be separately identified.

- Mental health

We included research on all mood disorders (eg depression, bi-polar, mania), neurosis and stress related disorders (eg anxiety, phobias, post traumatic stress disorder) personality disorders and schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders. Included studies had to state that participants had mental health problems as identified either through diagnosis, or through attendance at an establishment for people with mental health problems. Studies where mental health problems were secondary to a physical health problem were excluded.

The use of quality assessment in reviews of qualitative research is contested. Quality assessment is usually used in framework synthesis but this may be associated with its use alongside systematic reviews of effectiveness [ 16 ]. In this review, articles were not quality assessed and systematically excluded on the basis of quality. However, it was of paramount importance that any included study elicited the perspective of individuals with mental health problems and where this appeared not to be the case they were excluded. Consequently, studies were excluded when it was strongly suspected that the views of the researcher, or the method of analysis, had overly influenced the findings. These articles were examined and discussed at length by the research team before being excluded.

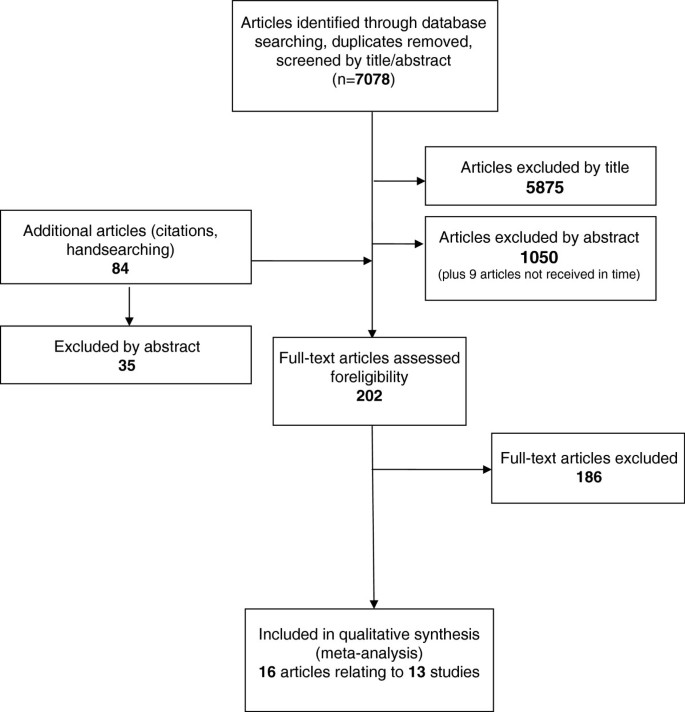

Although the searches were not restricted to English language articles, non-English language articles were excluded because of the potential for mis-interpretation. Five potentially relevant articles were excluded on the grounds of language (Figure 1 ).

PRISMA flow diagram of searched articles.

Data extraction and analysis

The following details of the studies were extracted: mental health problem studied; author affiliation; time and location of study; number and demographic details of participants; research aims and questions; recruitment and sampling methods; and method of data collection and analysis. Themes within the findings and discussion sections were extracted for the thematic analysis.

Framework analysis [ 18 ] was used to allow the identification of common and variable patterns of themes within and across different studies. The first stage of framework analysis- familiarisation - was undertaken by reading all included papers. The second stage involved examining the findings from these papers to identify initial themes for a thematic framework. These ten initial descriptive themes were either identified as main themes from more than one study, or arose consistently across studies. These were: activity; relationships; the self; the future/aspirations; symptoms/well-being/emotions; spirituality; control/coping; insight/education; health care services/interventions; and resources/basic needs. The third stage, data organisation, involved charting data from the findings and discussion sections that corresponded to each theme. Text was transferred verbatim to ensure contextual accuracy. It was common for text to be identified as supporting more than one theme, for example a quote describing how work was good for their self-esteem would be placed in the thematic categories ‘activity’ and ‘self’. At the next stage each initial theme was examined and further sub-themes identified and documented within the framework chart. To assist with the final stage of framework - mapping - the sub-themes were listed and examined for their conceptual similarities and differences. To aid this process, we searched the wider literature to find papers which would help us to understand the data, to make connections between sub-themes, and to assist in the development of our final themes. For example, ‘belonging’ was an emerging theme, and we identified Hagerty et al’s [ 20 ] research which explored and defined this concept. We then returned to our framework chart to re-examine our data in light of the wider literature. Other influential literature was on the theory of ‘doing, being, becoming’ [ 21 ], ill-being vs well-being and intrinsic and extrinsic quality of life [ 22 , 23 ] and demoralization [ 24 ]. We have reported this literature when describing the theme in the findings because it was influential in shaping our understanding of the theme. The themes and domains from the included papers were presented and organised in contrasting styles by the authors of those papers. Depending upon the theoretical background of the researcher, and the method of analysis used, this resulted in themes which were either objective and descriptive (e.g. relationships, occupation) or abstract or metaphoric in their presentation (e.g. ‘Upset and calm changes patterns of being with and apart from others’). For the latter, whether a theme was major or minor was the subjective view of the authors. We have reported a theme as being a major theme within the studies if it was: a) a titled theme within the study findings b) was reported as being represented throughout the data or c) formed a substantive part of those studies that used abstract or metaphoric themes or of those that were not organised thematically. For transparency the original themes or section titles from the original papers have been presented after the quotes provided to illustrate our findings.

Validation and trustworthiness

Validation procedures were incorporated into the review at all stages. Two researchers (JC and MLJ) independently identified articles from the first search iteration, and compared results to clarify the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Potential full articles were identified from further searches by the primary researcher and independently checked by the second researcher. The included articles were examined independently by both researchers to identify the main themes for the initial framework. Disagreements at all stages were resolved by discussion. Additionally, a multidisciplinary team of researchers met regularly in addition to meetings with clinicians and a user representative to discuss and challenge the inclusion and exclusion criteria, thematic framework, and conceptual interpretations and conclusions.

Description of included studies

Thirteen studies were identified from 16 articles [ 25 – 40 ]; two had fuller reports available, one an internal report [ 25 , 26 ] and the other a dissertation [ 27 , 28 ], the fuller reports [ 26 , 28 ] have been referenced in the findings. Further, one study indicated that not all emerging themes were presented in the paper and had a supplementary paper dedicated to the impact of bi-polar disorder on work functioning, which was included in our analysis [ 37 , 38 ]. The studies were published between 1994 and 2010 in a number of countries: Canada (5), UK (3), Sweden (2), USA (1), Australia (1) and New Zealand (1). The professional affiliations of the first author were occupational therapy (5), nursing (4), psychology (2), psychiatry (1) and social work (1). The mental health disorder most frequently represented was schizophrenia (or other psychotic disorder): this was the only population researched in three studies and the majority population in a further two. Three studies included individuals with bi-polar disorder only and one panic disorder only. Other studies had a mixed population including the above disorders plus persons with personality disorder, severe depression, and anxiety disorders. Two studies did not specify the disorder; they included persons described as having ‘enduring mental health problems’ and ‘psychiatric disability’.

Two studies had a primarily positive orientation in that they asked ‘what is required for a good quality of life’, and four studies a negative orientation through asking ‘how has your mental health affected your quality of life’. The remainder considered both ‘what had helped and hindered quality of life’. Most studies presented their findings descriptively, and four had a conceptual/abstract orientation. Further details of the studies [ 25 – 40 ] can be found in Table 1 .

We identified six major themes: well-being and ill-being; control, autonomy and choice; self-perception; belonging; activity; and hope and hopelessness. The themes identified within each of the studies can be found in Table 2 .

Well-being and Ill-being

Well-being has long been regarded as an important dimension of health related quality of life scales [ 14 ]. The emotional component of subjective well-being consists of high levels of positive affect (experiencing pleasant emotions and moods), and lack of low levels of negative affect (experiencing few unpleasant emotions and moods) [ 23 ]. Within our papers, symptoms of mental illness and aspects of emotional well-being were intertwined, with an emphasis on the negative rather than the positive. This suggested that ill-being, which is more akin to distress and the symptoms of mental illness, is an important aspect of quality of life for those with severe mental health problems.

The most evident ‘ill-being’ themes were general feelings of distress from symptoms; the experience of psychosis/mania; depressed mood; problems with energy and motivation and fear and anxiety.

Distress from symptoms

Distress, or the subjective experience of the symptoms of mental illness, was evident in the majority of studies [ 26 , 28 , 30 – 32 , 35 , 36 , 40 ] and a major theme in four [ 28 , 30 , 35 , 40 ]. The subjective experience of mental illness was described as wretched [ 36 ] a burden, debilitating, painful [ 40 ], tormenting [ 35 ], and as having a tyrannical power over life [ 28 ]. Pre-occupation with the symptoms of mental health problems interfered greatly with the most basic tasks of everyday living [ 26 , 28 , 31 , 40 ], making it difficult to deal with anything but the present moment [ 40 ]. Instead life was consumed with coping on a daily basis and living ‘one day at a time’ - sometimes on a moment to moment basis [ 28 , 31 , 34 ].

Symptoms of mental illness were described primarily in negative and restrictive ways . Subjects reported continually trying to deal with the symptoms , describing symptoms as “ a great burden .” The symptoms seemed to be so encompassing that these men had difficulty seeing beyond the pain of today . “ This illness is a great burden . Day - to - day survival is a big question , and I just feel in a turmoil a lot of the time ”; “ I ’ ve had terrible suffering for over 20 years.” [ 40 - A pervasive feeling of distress ]

Experience of psychosis/mania

Distressing symptoms reported included hallucinations and delusions (particularly hearing voices, thought disturbances and paranoia) [ 26 , 28 , 30 ], reality disorientation [ 28 ], mania, and hypomania [ 38 ], feelings of discomfort, weirdness or oddness [ 28 ], and irritability or agitation [ 30 ]. These symptoms could interfere directly with day to day living by having an effect on behaviour control [ 26 , 30 , 35 , 38 ], concentration, memory or decision making [ 26 , 30 , 31 ] and sense of self-identity [ 28 , 31 , 37 ].

“ When I hear voices erm , that stops me from doing a day to day existence , I ’ m preoccupied with the voices ”; “ … the voices , how they ’ ve affected my life , erm , er just day to day living basically … Erm just er , getting out , getting out and doing things er … go to the shops , erm , erm , cooking , anything , anything like that ”; “ I daren ’ t go out now , thoughts in my head , make me think bad things ; I get paranoid when there ’ s crowds of people. ” [ 26 - Fear of exacerbating mental health difficulties ].

Depressed mood

Depression was a diagnosis of a proportion of participants in two of the studies [ 28 , 29 ] and bi-polar disorder the primary diagnosis in three further studies [ 35 , 37 , 39 ]. Negative affect, in the more severe form of depression including feeling suicidal [ 26 ] (as opposed to simply being sad, unhappy), was also identified in studies where the primary diagnosis was psychosis related [ 26 , 30 , 34 , 36 , 40 ]. It was also the symptoms of depression in bi-polar patients that were reported as being particularly distressing [ 35 ], together with the unpredictability and instability of mood [ 35 , 38 ].

Energy and motivation

Depression was often expressed as associated with a lack of energy and/or motivation. Although energy and motivation might be regarded as two distinct concepts (physical and psychological), they were closely associated and for the most part reported together within the primary research. Energy, or lack of it, was a major theme in one study [ 39 ] and all but three of the primary research articles [ 32 , 33 , 35 ] described the debilitating effects of lack of energy. The three studies where energy and motivation were not evident focused on the nursing implications of panic disorder [ 32 ] the psycho-social issues related to bipolar disorder [ 35 ] and the positive determinants of health [ 33 ]. Participants reported feeling generally drained of energy [ 26 , 28 – 30 , 38 , 40 ] associated with a lack of motivation, enthusiasm, or interest in things [ 26 , 28 – 31 , 34 , 36 , 40 ]. The side effects of medication [ 26 ] or problems with sleep [ 26 , 30 ] were reported as having a causal effect.

“ The quality of my life in the last few years has been horrible , because it has taken so much energy and struggle to get through so many things …. I ’ ve got to get out , go out and do things or go to concerts or go to school things , or go to meetings or something , and doing some of those things is so tough , to make yourself , you know , get up and go . Just getting up to go out for a walk was really hard for me , whereas walking is one of my , you know , I love to go out and walk .” [ 29 - Distant hopes fuel the relentless struggle to carry on ]

Because lack of energy was a problem, conserving energy for those activities that brought pleasure and joy was important [ 39 ]. Whilst lack of energy was the dominant theme, hypomanic states in bi-polar disorder were associated with increased energy and enthusiasm but were often short-lived with a return to a usual depressed state [ 38 ].

Fear and anxiety

Two studies reported that ‘fear’ was a theme that was represented throughout their interview data [ 28 , 30 ]. Fear, anxiety, or worry was present in some form in all of the studies. The subjective experiences of the symptoms were reported as being very frightening [ 26 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 40 ]. This tended to be identified in the studies on schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder and panic disorder. As a consequence, individuals lived in fear of relapse or a return to hospital [ 26 , 28 , 30 ]. There were associated financial worries which had implications for planning for the future and making commitments [ 30 , 34 , 37 ].

Living day to day with a psychotic illness was described as a very frightening and isolating experience . The participants described their sense of fear while experiencing symptoms , watchfulness for reoccurrence of illness , concerns over safety , experiences of anxiety and rejection in interactions with others , avoidance of stressors , feelings that they were being treated as “ fragile ” by their families , and a sense of powerlessness in gaining control over symptoms [ 27 - The experience of illness ]

Anxiety in social situations was especially evident and took various forms including anxiety about leaving the house, crowds and public places [ 26 ], concerns for their own safety [ 26 , 28 , 36 ], and that of others [ 26 ], worrying about what others thought of them and how they appeared [ 26 , 28 , 30 ], worries and concerns within relationships [ 29 ] and fears of rejection [ 40 ]. Worries concerning relapse or aggravation of symptoms and social anxiety often resulted in the avoidance of any activity or situation which might be perceived as stressful [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 33 ] thus limiting the possibilities of improving other aspects of quality of life.

Avoiding situations they had previously enjoyed because of fear of how they would appear or that the stress associated with those situations would mean deterioration in mental health : “ I ’ ve cut down on the sort of positions I get myself in … because of bad experiences in the past …. you just try less things with the fear that you ’ re going to get very ill again and go to hospital ” [ 30 - reduced control of behaviour and actions ]

Within the studies reviewed there tended to be an emphasis on the absence of ill-being rather than the presence of well-being. However, the positive themes identified that were important to people included an overall sense of well-being [ 31 , 33 , 39 ], feeling healthy [ 31 ], peaceful, calm and relaxed [ 26 , 30 , 33 , 39 ], stable [ 30 , 35 ], safe [ 33 , 39 ] and free from worry and demands [ 33 , 39 ]. Enjoyment or happiness were not identifiable themes within the reviewed studies but were associated primarily with the need for activities to be enjoyable [ 31 , 36 , 39 ].

Physical well-being

Physical health was not a strong theme within the reviewed studies. The compounding effects of physical health problems were indicated in two studies [ 26 , 36 ] and physical health was listed as the second most important aspect of quality of life by participants in another [ 37 ]. A healthy lifestyle was considered beneficial which included exercise, avoiding drugs and generally taking care of oneself [ 26 , 28 , 33 ].

Control, autonomy and choice

The importance of aspects of choice and control to quality of life was identified in eight studies [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 ] and was a main theme in three of these [ 30 , 34 , 35 ]. It was often discussed in the context of the availability of external resources which enabled choice and control, including medication and treatment, support, information and finances.

Symptom control

One of the most evident aspects of control was the management of the most distressing or pervading aspects of mental illness, particularly for those with psychosis related disorders [ 26 , 28 , 31 – 35 , 38 , 39 ]. Control was usually described as being achieved through medication [ 26 , 28 , 33 – 35 , 39 ]. Having control meant that individuals could move beyond ‘the all encompassing world of their illness’ [ 28 ] and instead attend to other important areas of their lives [ 28 , 31 ]. However, medication could also have a detrimental effect on quality of life through side effects, [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 34 ] feelings of dependency, [ 34 , 35 ] and fear of the consequences of not taking it [ 30 ]. It was therefore necessary to find the right medication to balance symptom management and side effects [ 26 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 39 ] as a means to a sense of well-being [ 28 ].

“ I ’ m on good medication , no symptoms , no side effects . I used to go through all the side - effects and symptoms and I don ’ t have anything now . . before that , I never really felt human . . I ’ m human , I ’ m flesh , you know like that in my mind and , it ’ s just a good feeling . I can ’ t explain how I was , used to be but since I ’ ve been on this medication I feel like a human … I don ’ t have any side - effects or anything or any problems . . I just take my pills and go . Like I feel like a human being … it ’ s just great ”; “ I think for me , apparently the most important one is just managing the illness … different medications , side - effects , knowing what they are … for me there ' s been limited discomfort ” [ 28 - Experience of illness - gaining control ]

The concept of control was particularly important for those with bipolar disorder, and was related to an inability to control or pre-empt the onset of mood episodes or their behaviour [ 35 , 38 ] and to a need for stability [ 35 ].

Being informed and having an understanding and insight about the illness was considered to be important [ 26 , 28 , 32 , 34 , 39 ]. To achieve this it was important to have an accurate diagnosis [ 32 , 33 ]. This meant that people could receive effective medication [ 33 ], knew what to expect for the future [ 28 , 33 , 39 ] and could develop strategies to manage their illness and deal with it better [ 28 , 34 ]. This was regarded as a first step on the way to recovery [ 32 ] and improving quality of life [ 39 ].

Independence/dependence

There was a complex relationship between independence, dependence, and support. Both support [ 26 , 28 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 ] and independence [ 32 , 33 , 37 ], particularly financial independence [ 37 ] were regarded as being important for quality of life. Support helped people manage their illness, access resources, and increase their self-confidence [ 33 ]. However, it could also result in feelings of dependency [ 26 , 37 ] with a resulting loss of a sense of control and self-esteem [ 37 ]. Hence there could be a dilemma between wanting help and support and at the same time resenting it [ 29 ]. On the other hand, choosing to be dependent could enhance power and control [ 39 ]. Personal autonomy, finding the optimum balance between support and independence, was therefore important to quality of life [ 25 , 33 ].

“ I think that ’ s a big part of what I recognize now as quality of life is feeling I can take care of myself without being heavily dependent on a long - term basis on either the welfare system or my Dad , unless I ’ m choosing to do so for a specific reason ” [ 33 - Independence : ‘ Or rather , not being independent , but not being dependent ]

Personal strength, determination, and self-sufficiency were also regarded as important [ 26 , 32 , 33 , 38 ]. It meant people were able to make use of available resources and develop self-help and personal coping strategies [ 26 , 28 , 32 , 37 ] which in turn promoted independence and a sense of control [ 28 , 32 , 37 ].

The concept of choice was most associated with the availability of financial resources [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 37 ] and with limited employment opportunities [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 34 , 38 , 40 ]. Having sufficient financial resources meant people could more readily have a healthy lifestyle [ 33 ], engage in activities that promoted well-being [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 33 ], facilitate the attainment of an optimum balance between dependency and independence [ 26 , 37 ], have a choice in their surroundings [ 26 , 28 , 34 ] and be able to plan for the future [ 30 ].

“ I ’ d have had more money if I ’ d stayed in the [ job ] … I ’ d have been able to board the animals and go on holiday . I would have been able to afford a bigger house maybe even have some help with some of my domestic tasks . yes . it ’ s limited my choices ”…“ Lack of control of your finances because what you get in benefits goes immediately what with all the things you have to pay out for . So you have to be very careful … That ’ s another sort of loss of control of part of your life which doesn ’ t make you feel very good about yourself ” [ 30 - Financial constraints on activities and plans ]

Also of value was being able to choose whether or not to take part in things (particularly social activities), [ 28 , 34 ] flexible work conditions, [ 38 ] when and with whom to disclose mental illness, [ 34 ] and choices associated with mental health services, workers and interventions [ 26 ].

Self-perception

A number of aspects of self associated with quality of life were identified: self-efficacy - having a belief and confidence in your own abilities; self-identity - having a perception of self and knowing who you are; self-esteem - having a sense of self-worth and self-respect; and self-stigma - internalizing the negative views of others. These were linked to a further theme of self-acceptance. These self concepts were closely associated and used interchangeably within the studies reviewed making them difficult to differentiate. Aspects of the self and self-perception were a major theme in three studies [ 28 , 32 , 35 ] and were present in some form within all of the other studies except one [ 29 ] which had an abstract analytical style and only had undertones suggesting low self- esteem/image.

Self-identity

Problems related to self-identity, having a sense of self and ‘knowing who you are’ appeared particularly to be related to bi-polar disorder, schizophrenia, and panic disorder. The studies described difficulties with having a coherent sense of self, identity, and personality [ 31 , 32 , 35 , 37 , 39 ].

‘ when you end up in the hospital with a full - blown mania and you think that you ’ re a king and you ’ re screaming at the top of your lungs … trying to eat your hospital bed and , and … you don ’ t know how to deal with it or , or how to be . You don ’ t know how to become yourself again . You don ’ t know what happened to you . It ’ s like your identity has been changed . It ’ s like somebody hands you a different driver ’ s license and you ’ re like , ‘ Well who is this person ?’ [ 37 - Identity ]

This loss of a sense of self necessitated a re-negotiation [ 31 ] or reclaiming [ 32 ] of self, based on self-acceptance, self-knowledge and understanding, [ 31 , 32 , 37 , 39 ] and relationships with reliable others [ 39 ]. Spirituality also had a role in achieving a sense of self [ 28 ].

Self-efficacy

This concept was expressed in the reviewed studies primarily as a lack of self-confidence, but also as feelings of inadequacy, uselessness, failure, an inability to cope, and helplessness [ 26 , 28 , 30 – 33 , 35 , 37 ]. Mental health problems were associated with a lack of confidence [ 26 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 38 ]. This lack of confidence limited day to day functioning and activities [ 26 ], and access to helpful resources [ 26 ] and affected choice and opportunities in employment [ 26 , 28 , 38 ] and relationships [ 26 , 28 ]. Bipolar disorder could be associated with an increase in self-confidence during manic episodes [ 38 ].

Self-esteem and self-acceptance

The theme of self- esteem includes the concepts of self-image, worth, value, and shame, and a view of the self as ‘defective’ [ 26 , 28 , 30 , 35 – 37 , 40 ]. It was primarily reported as a negative concept closely associated with loss of self-identity [ 37 ] and confidence [ 35 ]. Occupational activity was considered particularly important for self-esteem and status [ 28 , 36 , 38 ], as was the satisfaction gained from helping others [ 28 ]. However, the difficulties encountered in obtaining employment often resulted in a lowering of self-esteem [ 30 , 40 ]. A closely related concept to self-esteem was the positive concept of self-acceptance, [ 28 , 32 , 37 , 40 ] acceptance of the self as a person with an illness [ 32 ], or the belief that the illness did not represent everything that they were [ 28 , 37 ].

Self-stigma

The theme of ‘the self’ was closely related to the next theme of ‘belonging’, particularly through the concepts of ‘stigma’ and ‘feeling normal’ (see below). This inter-relationship is most evident in the concept of self-stigmatization, an internalisation of the negative views of others [ 28 ].

Individuals living with severe and persistent mental illnesses suffer from a form of stigma - self - stigma - perhaps the most powerful of all stigmas as it affects the inner sense of self in very profound ways . ‘ I stigmatize myself . I just have a very low self - image . I ' m kind of hard on myself for not conducting myself the way I should be … not being as productive as I could be . It ' s a reflection from general community ' s perceptions of what this illness is all about . […] [ 27 - Sense of Self : Self doubt , criticism - a barrier ]

The concept of belonging has been defined as the experience of integration and personal involvement in a system or environment at differing interpersonal levels. It can have two dimensions: ‘valued involvement’ - the experience of feeling valued, needed, accepted; and ‘fit’ - the person’s perception that his or her characteristics articulate with, or complement, the system or environment [ 20 ].

Of the primary research studies included in the review, one identified ‘connecting and belonging’ as being important to quality of life [ 34 ]. Others identified closely related main themes: being part of a social context [ 33 ], rejection and isolation from the community [ 35 ], a need for acceptance by others [ 40 ], social support [ 37 ], relationships [ 28 ], barriers placed on relationships [ 30 ], labeling and attitudes from others [ 30 ], stigma [ 28 , 30 , 37 , 40 ], alienation [ 40 ], detachment and isolation [ 30 ].

Relationships

Relationships were clearly central to the concept of ‘belonging’. These relationships included close connections with family and friends and also more casual relations with the local community, in the workplace, with service providers or with society at large. The complex nature of relationships and the positive and/or negative effects on quality of life were evident in all the primary studies.

The provision of support was a particularly strong theme, being a major theme in three studies [ 33 , 37 , 39 ]. Both practical [ 26 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 37 , 39 ] and emotional [ 26 , 28 , 32 – 34 , 37 , 39 ] care and support was identified as important to quality of life. This could be from family and friends [ 26 , 28 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 ] or peers and work colleagues [ 28 , 38 , 39 ]. Also important was the support received from professionals [ 26 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 39 ]. When families and professionals were unsupportive, quality of life declined [ 26 , 28 , 39 ].

“[.] if you have schizophrenia or you have mental illnesses a lot of support helps , helps you get back on track ”; “ The support that they give me means a lot to me . I wouldn ' t be where I am today without my family and my friends . They ' ve supported me in every little way that they could … like my Mom will drive me to doctor ' s appointments … just having my family in [ name ] living around me … I know that if , if I can ' t get somewhere myself I can always rely on family members to take me ” [ 28 - Relationships with supportive family members ]

Within the reviewed studies the most predominant benefits of good and reliable relationships were to feel accepted and understood [ 26 , 28 , 33 – 35 , 37 , 40 ], and having company, camaraderie and shared interests [ 28 – 31 , 33 , 34 , 36 ]. Good relationships also satisfied the need for love, care, and affection [ 26 , 28 , 33 , 34 , 37 ], facilitated the experience of joy, fun, and happiness [ 29 , 33 ], someone to talk to/share problems with [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 39 ], to feel needed/helpful to others [ 28 , 30 , 33 , 39 ], to have people in whom one had trust and confidence [ 26 , 33 , 39 ] and who provided motivation and encouragement [ 33 ].