A Summary and Analysis of Audre Lorde’s ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’ is a 1977 essay by the American poet Audre Lorde (1934-92). In the essay, Lorde argues that poetry is a necessity for women, as it puts them in touch with old feelings and ways of knowing which they have long forgotten. Poetry also offers women a way to bring those feelings to light again and to share them with others.

You can read ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’ here before proceeding to our summary and analysis of Lorde’s essay below. The essay takes around five minutes to read.

‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’: summary

Lorde begins by drawing a connection between poetry and life, arguing that poetry is a form of illumination which helps us to make sense of our lives. True poetry, which stems from a distillation of experience, can then give rise to thoughts, much as a dream can give rise to a concept or a feeling can give rise to an idea, or as knowledge precedes, and helps us to develop, an understanding of something.

Poetry can thus help us to conquer our fears, since it allows us to understand and take control of those fears. Quoting lines from her 1973 poem ‘Black Mother Woman’, Lorde addresses other women, pointing out that their true spirits lie ‘hidden’ within them, out of sight. However, it is within the darkness that these secret ‘places of possibility’ within women have grown and survived.

These dark places within women contain great potential for creativity and power. The problem with European culture is that it privileges ideas over these dark, secret places inside. Connecting with the ancient ways of knowing encourages women to value their feelings over ‘ideas’.

However, Lorde believes that women can combine these two modes of knowing – feelings and ideas – in their poetry. This is why, for women, poetry is not a luxury, but a vital necessity. Poetry is one of the ways women can give a name to those nameless feelings they experience, so those feelings can be transformed into thought.

Poetry, Lorde argues, is the framework for women’s whole lives. It provides women with a way to make acceptable those ideas which would otherwise have been baffling or frightening. By respecting their own feelings, women can turn them into language and share them with other women. Indeed, poetry can even help to create a language for things, a language which does not already exist.

Lorde then discusses the difficult nature of ‘possibility’, or potential for change. It can easily be extinguished or diminished, especially when women are accused (by men) of being immature or overly reliant on their feelings. Lorde counters the ‘white fathers’, who said ‘ I think, therefore I am ’, with her own mantra from ‘the Black mother’: ‘I feel, therefore I can be free.’

But action is also needed. Rather than seeking new ideas to bring about the change that’s needed, Lorde urges women to turn to the ‘old and forgotten’ ideas which will give them courage. Poetry is a way of rediscovering these ideas and, more importantly, the authentic feelings women have. To give up poetry or dismiss it as a luxury is to deprive oneself of a better future for women.

‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’: analysis

It was W. H. Auden who famously said, in his poem ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’, that ‘ poetry makes nothing happen ’. He went on to remark that poetry’s value was as a ‘way of happening’: an act in and of itself which keeps the poet’s voice alive, or their ‘mouth’ from falling silent.

In ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’, Lorde goes further and seems to suggest that poetry can make things happen, although she shares with Auden a distrust of viewing ‘poetry’ and ‘action’ as two separate and distinguishable modes.

Words like ‘vital’ and ‘necessity’ make it clear to us that Lorde views poetry as an essential component of women’s struggle to liberate themselves from patriarchal oppression and control.

But she also suggests that, in particular, she has Black women in mind: words and phrases like ‘noneuropean’ (which appear to call back to the African heritage of African-American women in the modern United States) and ‘Black mother’ indicate that, for Lorde, poetry is especially valuable to women of colour who are facing racial as well as patriarchal oppression.

At one memorable moment in ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’, Audre Lorde quotes the line, ‘I think, therefore I am’, attributing it to ‘white fathers’. Specifically, this line is from the work of the seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes, who argued that he could be sure of his own existence because he was capable of rational thought.

Lorde’s recasting of this formula into ‘I feel, therefore I can be free’ reveals that the freedom that white men like Descartes could take for granted has always been unknowable to Black women, at least as lived experience. And ‘experience’ is another key term in ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury’: poetry is both a reflection of experience and a way of experiencing the world.

Because poetry does not rely on cold fact or reason, but instead fuses feelings, thoughts, ideas, and experience together in a heady mixture of intuition and knowledge, it can lead to a deeper kind of enlightenment or wisdom which acknowledges that how we feel about the world is as important as what the world ‘is’.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Advertisement

The legacy of audre lorde, arts & culture.

The art and life of Mark di Suvero

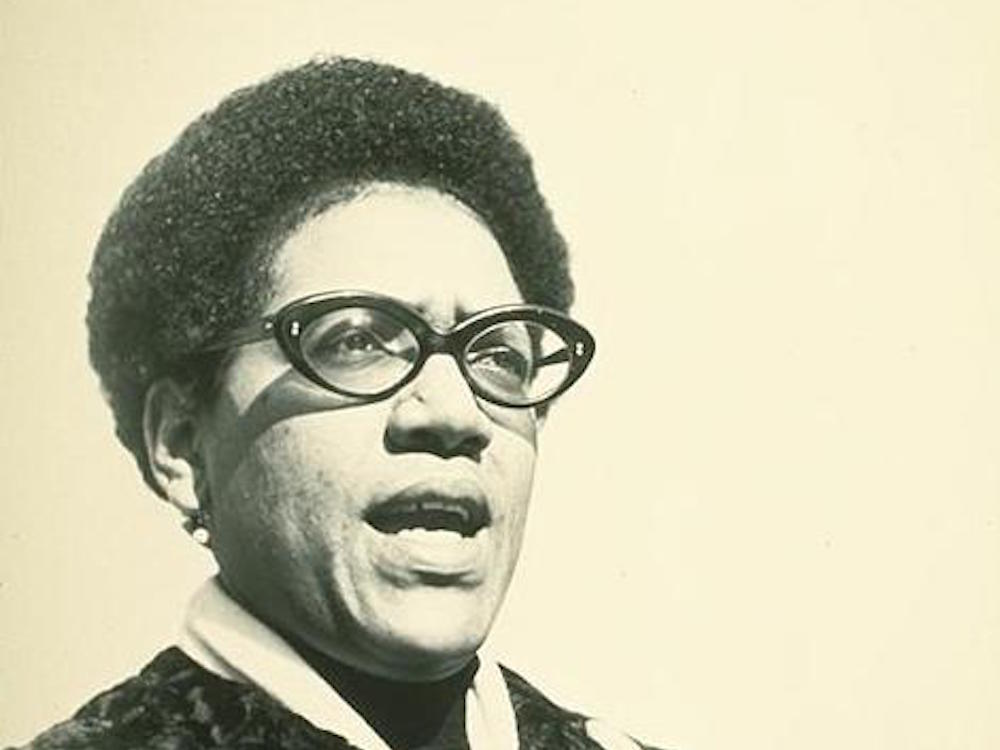

Audre Lorde. Photo: Elsa Dorfman. CC BY-SA (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/).

There is this thing that happens, all too often, when a Black woman is being introduced in a professional setting. Her accomplishments tend to be diminished. The introducer might laugh awkwardly, rushing through whatever impoverished remarks they have prepared. Rarely do they do the necessary research to offer any sense of whom they are introducing. The Black woman is spoken of in terms of anecdote rather than accomplishment. She is referred to as sassy on Twitter, maybe, or as a lover of bacon, random tidbits bearing no relation to the reasons she is in that professional setting. Whenever this happens to me or I witness it happening to another Black woman, I turn to Audre Lorde. I wonder how Lorde would respond to such a microaggression because in her prescient writings she demonstrated, time and again, a remarkable and necessary ability to stand up for herself, her intellectual prowess and that of all Black women, with power and grace. She recognized the importance of speaking up because silence would not protect her or anyone. She recognized that there would never be a perfect time to speak up because “while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us.”

In 1979, for example, Audre Lorde wrote a letter to Mary Daly, and when Daly did not respond, Lorde made her entreaty an open letter. Lorde was primarily concerned with the erasure of Black women in Daly’s Gyn/Ecology , a manifesto urging women toward a more radical feminism. In her open letter, Lorde wrote: “So the question arises in my mind, Mary, do you ever really read the work of Black women? Did you ever read my words, or did you merely finger through them for quotations which you thought might valuably support an already conceived idea concerning some old and distorted connection between us? This is not a rhetorical question.” The letter is both gracious and incisive. What Lorde is really demanding of Daly and white feminists more broadly is for them to seriously engage with and acknowledge Black women’s intellectual labor.

In the thirty years since Lorde wrote that open letter, Black women have continued to implore white women to recognize and engage with their intellectual contributions and the material realities of their lives. They have asked white women to acknowledge that, as Lorde also wrote in her open letter to Daly, “the oppression of women knows no ethnic nor racial boundaries, true, but that does not mean it is identical within those differences.” One of the hallmarks of Lorde’s prose and poetry is her willingness to recognize, acknowledge, and honor the lived realities of women—not only those who share her subject position but also those who do not. Her thinking always embodied what we now know as intersectionality and did so long before intersectionality became a defining feature of contemporary feminism in word if not in deed.

Lorde never grappled with only one aspect of identity. She was as concerned with class, gender, and sexuality as she was with race. She held these concerns and did so with care because she valued community and the diversity of the people who were part of any given community. She valued the differences between us as strengths rather than weaknesses. Doing this was of particular urgency, because to her mind, “the future of our earth may depend upon the ability of all women to identify and develop new definitions of power and new patterns of relating across difference.”

But how do you best represent a significant, in all senses of the word, body of work? This is the question that has consumed me as I assembled The Selected Works of Audre Lorde . Lorde is a towering figure in the world of letters, at least for me. I first encountered her writing in my early twenties, as a young Black queer woman. She was the first writer I ever read who lived and loved the way I did and also looked like me. She was a beacon, a guiding light. And she was far more than that because her prose and poetry astonished me—intelligent, fierce, powerful, sensual, provocative, indelible.

When I read her books, I underlined and annotated avidly. I whispered her intimately crafted turns of phrase, enjoying the sound and feel of them in my mouth, on my tongue. Lorde was the first person who actively demonstrated for me that a writer could be intensely concerned with the inner and outer lives of Black queer women, that our experiences could be the center instead of relegated to the periphery. She wrote beyond the white gaze and imagined a Black reality that did not subvert itself to the cultural norms dictated by whiteness. She valorized the body as much as she valorized the mind. She valorized nurturing as much as she valorized holding people accountable for their actions, calling out people and practices that decentered the Black queer woman’s experience and knowledge. Most important, she prioritized the collective because “without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression.” As a reader, it is gratifying to see the legacy Lorde has created and to see the genealogy of her work in the writing of the women who have followed in her footsteps. Without Lorde’s essay “The Uses of Anger,” we might never have known Claudia Rankine’s manifesto of poetic prose, Citizen .

In one of her most fiery essays, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Lorde asks, “What does it mean when tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy?” She quickly answers her own question: “It means that only the most narrow perimeters of change are possible and allowable.” Lorde gave these remarks in 1979 after being invited to an academic conference where there was only one panel with a Black feminist or lesbian perspective and only two Black women presenters. Forty years later, such meager representation is still an issue in many supposedly feminist and inclusive spaces. The essay is pointed, identifying pernicious issues marginalized people face in certain oppressive spaces—having to be the sole representative of their subject position, having to use their intellectual and emotional labor to address oppression instead of any of their other intellectual interests as if the marginalized are equipped to talk about only their marginalization.

This is a reality we often lose sight of when we surrender to assimilationist ideas about social change. There is, for example, a strain of feminism that believes if only women act like men, we will achieve the equality we seek. Lorde asks us to do the more difficult and radical work of imagining what our realities might look like if masculinity were not the ideal to which we aspire, if heterosexuality were not the ideal to which we aspire, if whiteness were not the ideal to which we aspire.

In Lorde’s body of work, we see her defying this idea of the dominant culture as the default, this idea that she should write about only her oppression, but while doing so she never abandons her subject position. She is empathetic, curious, critical, intuitive. She is as open about her weaknesses as she is about her strengths. She is an exemplar of public intellectualism who is as relevant in this century as she was in the last.

We are rather attached to the notion of truth as singular, but the best writing reminds us that truth is complex and subjective. The best writing reminds us that we need not relegate the truth to the narrow perimeters of right and wrong, black and white, good and evil. I have thought about how narrow the perimeters of change really are when we insist on using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house. This narrow brand of thinking has only intensified since the 2016 presidential election, when Donald Trump was elected. Whatever progress it seemed like we were making during the Obama era has retracted sharply, painfully. We live in a very fractured time, one where difference has become weaponized, demonized, and where discourse demands allegiance to extremes instead of nuanced points of view. We live in a time where the president of the United States flouts all conventions of the office, decorum, and decency. Police brutality persists, unabated. Women share their experiences with sexual harassment or violence but rarely receive any kind of justice.

It seems like things have gotten only worse since the height of Lorde’s career, when she was writing about the very things we continue to deal with—the place of women and, more specifically, Black women in the world, what it means to raise Black girls and boys in a world that will not welcome them, what it means to live in a world so harshly stratified by class, what it means to live in a vulnerable body, what it means to live. There are very few voices for women and even fewer voices for Black women, speaking from the center of consciousness, from the I am out to the we are , but Lorde was, throughout her storied career, one such voice. In her poem “Power,” Lorde wrote about a white police officer who murdered a ten-year-old Black boy and was acquitted by a jury of eleven of his peers and one Black woman who succumbed to the will of those peers. She captured the rage of such injustice and how futile it feels to try to fight such injustice, but she also demonstrated that even in the face of futility, silence is never an option.

A great deal of Lorde’s writing was committed to articulating her worldview in service of the greater good. She crafted lyrical manifestos. The essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” made the case for the importance of poetry, arguing that poetry “is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.” In “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Lorde examines women using their erotic power to benefit themselves instead of benefiting men. She notes that women are often vilified for their erotic power and treated as inferior. She suggests that we can rethink and reframe this paradigm. This is what is so remarkable about Lorde’s writing—how she encourages women to understand weaknesses as strengths. She writes: “As women, we need to examine the ways in which our world can be truly different. I am speaking here of the necessity for reassessing the quality of all aspects of our lives and our work, and how we move toward and through them.” In this, she offers an expansive definition of the erotic, one that goes well beyond the carnal to encompass a wide range of sensate experiences.

Rethinking and reframing paradigms is a recurring theme in Lorde’s writing. As the child of immigrants who came to the United States for their American dream only to have that dream shattered by the Great Depression, Lorde understood the nuances of oppression from an early age. It was poetry that gave her the language to make sense of that oppression and to resist it, and she was a prolific poet with several collections to her name, including The First Cities , Cables to Rage , From a Land Where Other People Live , Coal , and The Black Unicorn .

Her work took other forms—teaching; cofounding Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press; public speaking; and a range of advocacy efforts for women, lesbians, and Black people. During her time in Germany, she gave rise to the Afro-German movement—helping Black German women use their voices to join the sisterhood she valued so dearly. She also demanded that white German women confront their whiteness, even when it made them defensive or uncomfortable. In an essay about Lorde’s time in Germany, Dagmar Schultz wrote that “many white women learned to be more conscious of their privileges and more responsible in the use of their power.”

Lorde was not constrained by boundaries. She combined the personal and the political, the spiritual and the secular. As an academic she fearlessly wrote about the sensual and the sexual even though the academy has long disdained such interests. Her erotic life was as valuable as her intellectual life and she was unabashed in making this known. This refusal to be constrained was notably apparent in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name , which she called a “biomythography.” In her definitive biography of Lorde, Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde , Alexis De Veaux describes Zami as a book that “recovers from existing male-dominated literary genres (history, mythology, autobiography, and fiction) whatever was inextricably female, female-centered.” In Zami and much of her other work, Lorde expressed the radical idea that Black women could hold the center, be the center, and she was unwavering in this belief.

At her most vulnerable, Lorde gave the world some of her most powerful writing with her work in The Cancer Journals , which chronicled her life with breast cancer and having a double mastectomy. “But it is that very difference which I wish to affirm, because I have lived it, and survived it, and wish to share that strength with other women. If we are to translate the silence surrounding breast cancer into language and action against this scourge, then the first step is that women with mastectomies must become visible to each other.” With these words, she assumed as much control as she could over a body succumbing to disease and a public narrative that, until then, allowed a singular narrative about what it meant to live with illness. She made herself visible and gave other women permission to make themselves visible in a world that would prefer that they disappear, stay silent.

In all of her writing, Audre Lorde offers us language to articulate how we might heal our fractured sociopolitical climate. She gives us instructions for making tools with which we can dismantle the houses of our oppressors. She remakes language with which we can revel in our sensual and sexual selves. She forges a space within which we can hold ourselves and each other accountable to both our needs and the greater good.

All too often, people misappropriate the words and ideas of Black women. They do so selectively, using the parts that serve their aims, and abandoning those parts that don’t. People will, for example, parrot Lorde’s ideas about dismantling the master’s house without taking into account the context from which Lorde crafted those ideas. Lorde is such a brilliant and eloquent writer; she has such a way of shaping language that of course people want to repeat her words to their own ends. But her work is far more than something pretty to parrot. In The Selected Works of Audre Lorde , you will be able to appreciate the grace, power, and fierce intelligence of her writing, to understand where she was writing from and why, and to bear witness to all the unforgettable ways she made herself, and all Black women, gloriously visible.

Roxane Gay’s writing appears in Best American Mystery Stories 2014 , Best American Short Stories 2012 , Best Sex Writing 2012 , Harper’s Bazaar , A Public Space , McSweeney’s , Tin House , Oxford American , American Short Fiction , Virginia Quarterly Review , and many other publications. She is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times . She is the author of the books Ayiti , An Untamed State , the New York Times best-selling Bad Feminist , the nationally best-selling Difficult Women , and New York Times best-selling Hunger: A Memoir of My Body . She is also the author of World of Wakanda for Marvel and the editor of Best American Short Stories 2018 . She is currently at work on film and television projects, a book of writing advice, an essay collection about television and culture, and a YA novel entitled The Year I Learned Everything .

Reprinted from The Selected Works of Audre Lorde . Copyright © 2020 by Roxane Gay. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

A Burst of Light: Audre Lorde on Turning Fear Into Fire

By maria popova.

“There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear,” Toni Morrison exhorted in considering the artist’s task in troubled times . In our interior experience as individuals, as in the public forum of our shared experience as a culture, our courage lives in the same room as our fear — it is in troubled times, in despairing times, that we find out who we are and what we are capable of.

That is what the great poet, essayist, feminist, and civil rights champion Audre Lorde (February 18, 1934–November 17, 1992) explores with exquisite self-possession and might of character in a series of diary entries included in A Burst of Light: and Other Essays ( public library ).

Seventeen days before she turned fifty, and six years after she underwent a mastectomy for breast cancer, Lorde was told she had liver cancer. She declined surgery and even a biopsy, choosing instead to go on living her life and her purpose, exploring alternative treatments as she proceeded with her planned teaching trip to Europe. In a diary entry penned on her fiftieth birthday, Lorde reckons with the sudden call to confront the ultimate fear:

I want to write down everything I know about being afraid, but I’d probably never have enough time to write anything else. Afraid is a country where they issue us passports at birth and hope we never seek citizenship in any other country. The face of afraid keeps changing constantly, and I can count on that change. I need to travel light and fast, and there’s a lot of baggage I’m going to have to leave behind me. Jettison cargo.

“Not every man knows what he shall sing at the end,” the poet Mark Strand, born within weeks of Lorde, wrote in his stunning ode to mortality . Exactly a month after her diagnosis, with the medical establishment providing more confusion than clarity as she confronts her mortality, Lorde resolves in her journal:

Dear goddess! Face-up again against the renewal of vows. Do not let me die a coward, mother. Nor forget how to sing. Nor forget song is a part of mourning as light is a part of sun.

By the spring, she had lost nearly fifty pounds. But she was brimming with a crystalline determination to do the work of visibility and kinship across difference. She taught in Germany, immersed herself in the international communities of the African Diaspora, and traveled to the world’s first Feminist Book Fair in London. “I may be too thin, but I can still dance!” she exults in her diary on the first day of June. She dances with her fear in an entry penned six days later:

I am listening to what fear teaches. I will never be gone. I am a scar, a report from the frontlines, a talisman, a resurrection. A rough place on the chin of complacency.

Echoing Dr. King’s abiding observation that “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality [and] whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly,” she adds:

I am saving my life by using my life in the service of what must be done. Tonight as I listened to the ANC speakers from South Africa at the Third World People’s Center here, I was filled with a sense of self-answering necessity, of commitment as a survival weapon. Our battles are inseparable. Every person I have ever been must be actively enlisted in those battles, as well as in the battle to save my life.

Two days later, as the opaqueness of her prospects thrusts her once again into maddening uncertainty, she redoubles her resolve to let fear be her teacher of courage:

Survival isn’t some theory operating in a vacuum. It’s a matter of my everyday living and making decisions. How do I hold faith with sun in a sunless place? It is so hard not to counter this despair with a refusal to see. But I have to stay open and filtering no matter what’s coming at me, because that arms me in a particularly Black woman’s way.

In a sentiment that parallels Rosanne Cash’s courageous navigation of uncertainty in the wake of her brain tumor diagnosis, Lorde adds:

When I’m open, I’m also less despairing. The more clearly I see what I’m up against, the more able I am to fight this process going on in my body that they’re calling liver cancer. And I am determined to fight it even when I am not sure of the terms of the battle nor the face of victory. I just know I must not surrender my body to others unless I completely understand and agree with what they think should be done to it. I’ve got to look at all of my options carefully, even the ones I find distasteful. I know I can broaden the definition of winning to the point where I can’t lose.

Echoing French philosopher Simone Weil’s bold ideas on how to make use of our suffering , Lorde writes three days later:

We all have to die at least once. Making that death useful would be winning for me. I wasn’t supposed to exist anyway, not in any meaningful way in this fucked-up whiteboys’ world. I want desperately to live, and I’m ready to fight for that living even if I die shortly. Just writing those words down snaps every thing I want to do into a neon clarity… For the first time I really feel that my writing has a substance and stature that will survive me.

Beholding the overwhelming response to her just-released nonfiction collection, Sister Outsider — the source of her now-iconic indictment against silence — Lorde reflects:

I have done good work. I see it in the letters that come to me about Sister Outsider , I see it in the use the women here give the poetry and the prose. But first and last I am a poet. I’ve worked very hard for that approach to living inside myself, and everything I do, I hope, reflects that view of life, even the ways I must move now in order to save my life. I have done good work. There is a hell of a lot more I have to do. And sitting here tonight in this lovely green park in Berlin, dusk approaching and the walking willows leaning over the edge of the pool caressing each other’s fingers, birds birds birds singing under and over the frogs, and the smell of new-mown grass enveloping my sad pen, I feel I still have enough moxie to do it all, on whatever terms I’m dealt, timely or not. Enough moxie to chew the whole world up and spit it out in bite-sized pieces, useful and warm and wet and delectable because they came out of my mouth.

Over the following year, Lorde continued asking herself the difficult, beautiful questions that allowed her to concentrate the laser beam of her determination and her purpose as an artist and cultural leader into a focal point of absolute clarity. In a diary entry from October of 1985, several months after her daughter’s hard-earned graduation from Harvard, she wonders:

Where does our power lie and how do we school ourselves to use it in the service of what we believe? […] How can we use each other’s differences in our common battles for a livable future? All of our children are prey. How do we raise them not to prey upon themselves and each other? And this is why we cannot be silent, because our silences will come to testify against us out of the mouths of our children.

In early December, she resolves with magmatic determination:

No matter how sick I feel, I’m still afire with a need to do something for my living. […] I want to live the rest of my life, however long or short, with as much sweetness as I can decently manage, loving all the people I love, and doing as much as I can of the work I still have to do. I am going to write fire until it comes out my ears, my eyes, my noseholes — everywhere. Until it’s every breath I breathe. I’m going to go out like a fucking meteor!

Lorde lived nearly another decade after her diagnosis, during which she was elected Poet Laureate of New York State. In an African naming ceremony performed in the Virgin Islands shortly before her death at the age of fifty-eight, she took the name Gamda Adisa — “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known.”

Complement this particular portion of A Burst of Light , an explosive read in its totality, with Alice James on how to live fully while dying , Descartes on the vital relationship between fear and hope , and Seneca on overcoming fear , then revisit Lorde on the indivisibility of identity and the courage to break silence .

— Published March 1, 2018 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2018/03/01/audre-lorde-a-burst-of-light/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, audre lorde books culture diaries philosophy poetry psychology, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

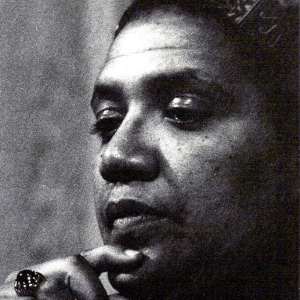

Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde (/ˈɔːdri lɔːrd/; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, February 18, 1934– November 17, 1992) was an African American writer, feminist, womanist, lesbian, and civil rights activist. As a poet, she is best known for technical mastery and emotional expression, particularly in her poems expressing anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life. Her poems and prose largely dealt with issues related to civil rights, feminism, and the exploration of black female identity. In relation to non-intersectional feminism in the United States, Lorde famously said, “Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference—those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older—know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.”

Life and work

Lorde was born in New York City to Caribbean immigrants from Barbados and Carriacou, Frederick Byron Lorde (called Byron) and Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde, who settled in Harlem. Lorde’s mother was of mixed ancestry but could pass for white, a source of pride for her family. Lorde’s father was darker than the Belmar family liked, and they only allowed the couple to marry because of Byron Lorde’s charm, ambition, and persistence. Nearsighted to the point of being legally blind, and the youngest of three daughters (two older sisters, Phyllis and Helen), Audre Lorde grew up hearing her mother’s stories about the West Indies. She learned to talk while she learned to read, at the age of four, and her mother taught her to write at around the same time. She wrote her first poem when she was in eighth grade.

Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, she chose to drop the “y” from her first name while still a child, explaining in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name that she was more interested in the artistic symmetry of the “e”-endings in the two side-by-side names “Audre Lorde” than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended.

Lorde’s relationship with her parents was difficult from a young age. She was able to spend very little time with her father and mother, who were busy maintaining their real estate business in the tumultuous economy after the Great Depression, and when she did see them, they were often cold or emotionally distant. In particular, Lorde’s relationship with her mother, who was deeply suspicious of people with darker skin than hers (which Lorde’s was) and the outside world in general, was characterized by “tough love” and strict adherence to family rules. Lorde’s difficult relationship with her mother would figure prominently in later poems, such as Coal’s “Story Books on a Kitchen Table.”

As a child, Lorde, who struggled with communication, came to appreciate the power of poetry as a form of expression. She memorized a great deal of poetry, and would use it to communicate, to the extent that, “If asked how she was feeling, Audre would reply by reciting a poem.” Around the age of twelve, she began writing her own poetry and connecting with others at her school who were considered “outcasts” as she felt she was.

She attended Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students, and graduated in 1951.

In 1954, she spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal, during which she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as a lesbian and poet. On her return to New York, she attended Hunter College, graduating class of 1959. There, she worked as a librarian, continued writing and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master’s degree in Library Science in 1961. She also worked during this time as a librarian at Mount Vernon Public Library and married attorney Edwin Rollins; they divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968.

In 1968 Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, where she met Frances Clayton, a white professor of psychology, who was to be her romantic partner until 1989.

Lorde’s time at Tougaloo College, like her year at the National University of Mexico, was a formative experience for Lorde as an artist. She led workshops with her young, black undergraduate students, many of whom were eager to discuss the civil rights issues of that time. Through her interactions with her students, she reaffirmed her desire not only to live out her “crazy and queer” identity, but devoted new attention to the formal aspects of her craft as a poet. Her book of poems Cables to Rage came out of her time and experiences at Tougaloo.

From 1977 to 1978 Lorde had a brief affair with the sculptor and painter Mildred Thompson. The two met in Nigeria in 1977 at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Their affair ran its course during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C.

The Berlin Years

In 1984 Audre Lorde started a visiting professorship in Berlin Germany at the Free University of Berlin. She was invited by Dagmar Schultz who met her at the UN “World Women’s Conference” in Copenhagen in 1980. While Lorde was in Germany she made a significant impact on the women there and was a big part of the start of the Afro-German movement. The term Afro-German was created by Lorde and some Black German women as a nod to African-American. During her many trips to Germany, she touched many women’s lives including May Ayim, Ika Hugel-Marshell, and Hegal Emde. All of these women decided to start writing after they met Audre Lorde. She encouraged the women of Germany to speak up and have a voice. Instead of fighting through violence, Lorde thought that language was a powerful form of resistance. Her impact on Germany reached more than just Afro-German women. Many white women and men found Lorde’s work to be very beneficial to their own lives. They started to put their privilege and power into question and became more conscious.

Because of her impact on the Afro-German movement, Dagmar Schultz put together a documentary to highlight the chapter of her life that was not known to many. Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years was accepted by the Berlinale in 2012 and from then was showed at many different film festivals around the world and received five awards. The film showed the lack of recognition that Lorde received for her contributions towards the theories of intersectionality.

Audre Lorde battled cancer for fourteen years. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, she was diagnosed with liver cancer. After her diagnosis, she chose to become more focused on both her life and her writing. She wrote The Cancer Journals, which won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award in 1981. She featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, which shows her as an author, poet, human rights activist, feminist, lesbian, a teacher, a survivor, and a crusader against bigotry. She is quoted in the film as saying: “What I leave behind has a life of its own. I’ve said this about poetry; I’ve said it about children. Well, in a sense I’m saying it about the very artifact of who I have been.”

From 1991 until her death, she was the New York State Poet Laureate. In 1992, she received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. In 2001, Publishing Triangle instituted the Audre Lorde Award to honour works of lesbian poetry.

Lorde died of liver cancer on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix, where she had been living with Gloria I. Joseph. She was 58. In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gamba Adisa, which means “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known”.

Lorde focused her discussion of difference not only on differences between groups of women but between conflicting differences within the individual. “I am defined as other in every group I’m part of,” she declared. “The outsider, both strength and weakness. Yet without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression”. She described herself both as a part of a “continuum of women” and a “concert of voices” within herself.

Her conception of her many layers of selfhood is replicated in the multi-genres of her work. Critic Carmen Birkle wrote: “Her multicultural self is thus reflected in a multicultural text, in multi-genres, in which the individual cultures are no longer separate and autonomous entities but melt into a larger whole without losing their individual importance.” Her refusal to be placed in a particular category, whether social or literary, was characteristic of her determination to come across as an individual rather than a stereotype. Lorde considered herself a “lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” and used poetry to get this message across.

Lorde’s poetry was published very regularly during the 1960s—in Langston Hughes’ 1962 New Negro Poets, USA; in several foreign anthologies; and in black literary magazines. During this time, she was also politically active in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist movements.

In 1968, Lorde published The First Cities, her first volume of poems. It was edited by Diane di Prima, a former classmate and friend from Hunter College High School. The First Cities has been described as a “quiet, introspective book,” and Dudley Randall, a poet and critic, asserted in his review of the book that Lorde “does not wave a black flag, but her blackness is there, implicit, in the bone”.

Her second volume, Cables to Rage (1970), which was mainly written during her tenure as poet-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, addressed themes of love, betrayal, childbirth, and the complexities of raising children. It is particularly noteworthy for the poem “Martha,” in which Lorde openly confirms her homosexuality for the first time in her writing: "[W]e shall love each other here if ever at all.”

Nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1973, From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press) shows Lorde’s personal struggles with identity and anger at social injustice. The volume deals with themes of anger, loneliness, and injustice, as well as what it means to be an African-American woman, mother, friend, and lover.

1974 saw the release of New York Head Shop and Museum, which gives a picture of Lorde’s New York through the lenses of both the civil rights movement and her own restricted childhood: stricken with poverty and neglect and, in Lorde’s opinion, in need of political action.

Despite the success of these volumes, it was the release of Coal in 1976 that established Lorde as an influential voice in the Black Arts Movement (Norton), as well as introducing her to a wider audience. The volume includes poems from both The First Cities and Cables to Rage, and it unties many of the themes Lorde would become known for throughout her career: her rage at racial injustice, her celebration of her black identity, and her call for an intersectional consideration of women’s experiences. Lorde followed Coal up with Between Our Selves (also in 1976) and Hanging Fire (1978).

In Lorde’s volume The Black Unicorn (1978), she describes her identity within the mythos of African female deities of creation, fertility, and warrior strength. This reclamation of African female identity both builds and challenges existing Black Arts ideas about pan-Africanism. While writers like Amiri Baraka and Ishmael Reed utilized African cosmology in a way that “furnished a repertoire of bold male gods capable of forging and defending an aboriginal black universe,” in Lorde’s writing “that warrior ethos is transferred to a female vanguard capable equally of force and fertility.”

Lorde’s poetry became more open and personal as she grew older and became more confident in her sexuality. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Lorde states, "Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought…As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring ideas." Sister Outsider also elaborates Lorde’s challenge to European-American traditions.

The Cancer Journals (1980), derived in part from personal journals written in the late seventies, and A Burst of Light (1988) both use non-fiction prose to preserve, explore, and reflect on Lorde’s diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from breast cancer. In both works, Lorde deals with Western notions of illness, treatment, and physical beauty and prosthesis, as well as themes of death, fear of mortality, victimization versus survival, and inner power.

Lorde’s deeply personal novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), described as a “biomythography,” chronicles her childhood and adulthood. The narrative deals with the evolution of Lorde’s sexuality and self-awareness.

In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984), Lorde asserts the necessity of communicating the experience of marginalized groups in order to make their struggles visible in a repressive society. She emphasizes the need for different groups of people (particularly white women and African-American women) to find common ground in their lived experience.

One of her works in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches is “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Lorde questions the scope and ability for change to be instigated when examining problems through a racist, patriarchal lens. She insists that women see differences between other women not as something to be tolerated, but something that is necessary to generate power and to actively “be” in the world. This will create a community that embraces differences, which will ultimately lead to liberation. Lorde elucidates, “Divide and conquer, in our world, must become define and empower." Also, one must educate themselves about the oppression of others because expecting a marginalized group to educate the oppressors is the continuation of racist, patriarchal thought. She explains that this is a major tool utilized by oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns. She concludes that in order to bring about real change, we cannot work within the racist, patriarchal framework because change brought about in that will not remain.

Another work in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches is “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.*” Lorde discusses the importance of speaking, even when afraid because one’s silence will not protect them from being marginalized and oppressed. Many people fear to speak the truth because of how it may cause pain, however, one ought to put fear into perspective when deliberating whether to speak or not. Lorde emphasizes that “the transformation of silence into language and action is a self-revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger." People are afraid of others’ reactions for speaking, but mostly for demanding visibility, which is essential to live. Lorde adds, “We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and ourselves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid." People are taught to respect their fear of speaking more than silence, but ultimately, the silence will choke us anyway, so we might as well speak the truth.

In 1980, together with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of color. Lorde was State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992.

Her writings are based on the “theory of difference,” the idea that the binary opposition between men and women is overly simplistic; although feminists have found it necessary to present the illusion of a solid, unified whole, the category of women itself is full of subdivisions.

Lorde identified issues of class, race, age, gender, and even health– this last was added as she battled cancer in her later years– as being fundamental to the female experience. She argued that, although differences in gender have received all the focus, it is essential that these other differences are also recognized and addressed. “Lorde,” writes the critic Carmen Birkle, “puts her emphasis on the authenticity of experience. She wants her difference acknowledged but not judged; she does not want to be subsumed into the one general category of ‘woman.’” This theory is today known as intersectionality.

While acknowledging that the differences between women are wide and varied, most of Lorde’s works are concerned with two subsets that concerned her primarily—race and sexuality. In Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s documentary A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, Lorde says, "Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the ‘60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a Black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a Black lesbian and feminist".

In her essay “The Erotic as Power,” written in 1978 and collected in Sister Outsider, Lorde theorizes the Erotic as a site of power for women only when they learn to release it from its suppression and embrace it. She proposes that the Erotic needs to be explored and experienced wholeheartedly, because it exists not only in reference to sexuality and the sexual, but also as a feeling of enjoyment, love, and thrill that is felt towards any task or experience that satisfies women in their lives, be it reading a book or loving one’s job. She dismisses “the false belief that only by the suppression of the erotic within our lives and consciousness can women be truly strong. But that strength is illusory, for it is fashioned within the context of male models of power.” She explains how patriarchal society has misnamed it used it against women, causing women to fear it. Women also fear it because the erotic is powerful and a deep feeling. Women must share each others’ power rather than use it without consent, which is abuse. They should do it as a method to connect everyone in their differences and similarities. Utilizing, the erotic as power allows women to use their knowledge and power to face the issues of racism, patriarchy, and our anti-erotic society.

Contemporary feminist thought

Lorde set out to confront issues of racism in feminist thought. She maintained that a great deal of the scholarship of white feminists served to augment the oppression of black women, a conviction that led to angry confrontation, most notably in a blunt open letter addressed to the fellow radical lesbian feminist Mary Daly, to which Lorde claimed she received no reply. Daly’s reply letter to Lorde, dated 4½ months later, was found in 2003 in Lorde’s files after she died.

This fervent disagreement with notable white feminists furthered Lorde’s persona as an outsider: "In the institutional milieu of black feminist and black lesbian feminist scholars [...] and within the context of conferences sponsored by white feminist academics, Lorde stood out as an angry, accusatory, isolated black feminist lesbian voice".

The criticism was not one-sided: many white feminists were angered by Lorde’s brand of feminism. In her 1984 essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Lorde attacked underlying racism within feminism, describing it as unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy. She argued that, by denying difference in the category of women, white feminists merely furthered old systems of oppression and that, in so doing, they were preventing any real, lasting change. Her argument aligned white feminists who did not recognize race as a feminist issue with white male slave-masters, describing both as “agents of oppression.”

Lorde’s comments on feminism

In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes: “Certainly there are very real differences between us of race, age, and sex. But it is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences, and to examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them and their effects upon human behavior and expectation.” More specifically she states: “As white women ignore their built-in privilege of whiteness and define woman in terms of their own experience alone, then women of color become ‘other’.” Self-identified as “a forty-nine-year-old Black lesbian feminist socialist mother of two,” Lorde is considered as “other, deviant, inferior, or just plain wrong” in the eyes of the normative “white male heterosexual capitalist” social hierarchy. “We speak not of human difference, but of human deviance,” she writes. In this respect, Lorde’s ideology coincides with womanism, which “allows black women to affirm and celebrate their color and culture in a way that feminism does not.”

Influences on Black Feminism

Lorde’s work on black feminism continues to be examined by scholars today. Jennifer C. Nash examines how black feminists acknowledge their identities and find love for themselves through those differences. Nash cites Lorde, who writes, “I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices." Nash explains that Lorde is urging black feminists to embrace politics rather than fear it, which will lead to an improvement in society for them. Lorde adds, “Black women sharing close ties with each other, politically or emotionally, are not the enemies of Black men. Too frequently, however, some Black men attempt to rule by fear those Black women who are more ally than enemy.” Lorde insists that the fight between black women and men must end in order to end racist politics.

Personal Identity

Throughout Lorde’s career she included the idea of a collective identity in many of her poems and books. Audre Lorde did not just identify with one category but she wanted to celebrate all parts of herself equally. She was known to describe herself as African-American, black, feminist, poet, mother, etc. In her novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name Lorde focuses on how her many different identities shape her life and the different experiences she has because of them. She shows us that personal identity is found within the connections between seemingly different parts of life. Personal identity is often associated with the visual aspect of a person, but as Lies Xhonneux theorizes when identity is singled down to just to what you see, some people, even within minority groups, can become invisible. In her late book The Cancer Journals she said “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” This is important because an identity is more than just what people see or think of a person, it is something that must be defined by the individual. “The House of Difference” is a phrase that has stuck with Lorde’s identity theories. Her idea was that everyone is different from each other and it is the collective differences that make us who we are, instead of one little thing. Focusing on all of the aspects of identity brings people together more than choosing one piece of an identity.

Audre Lorde and womanism

Audre Lorde’s criticism of feminists of the 1960s identified issues of race, class, age, gender and sexuality. Similarly, author and poet Alice Walker coined the term “womanist” in an attempt to distinguish black female and minority female experience from “feminism”. While “feminism” is defined as “a collection of movements and ideologies that share a common goal: to define, establish, and achieve equal political, economic, cultural, personal, and social rights for women” by imposing simplistic opposition between “men” and “women,” the theorists and activists of the 1960s and 1970s usually neglected the experiential difference caused by factors such as race and gender among different social groups.

Womanism and its ambiguity

Womanism’s existence naturally opens various definitions and interpretations. Alice Walker’s comments on womanism, that “womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender,” suggests that the scope of study of womanism includes and exceeds that of feminism. In its narrowest definition, womanism is the black feminist movement that was formed in response to the growth of racial stereotypes in the feminist movement. In a broad sense, however, womanism is “a social change perspective based upon the everyday problems and experiences of black women and other women of minority demographics,” but also one that “more broadly seeks methods to eradicate inequalities not just for black women, but for all people” by imposing socialist ideology and equality. However, because womanism is open to interpretation, one of the most common criticisms of womanism is its lack of a unified set of tenets. It is also criticized for its lack of discussion of sexuality.

Lorde actively strived for the change of culture within the feminist community by implementing womanist ideology. In the journal "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde’s 1981 Keynote Admonishing the National Women’s Studies Association," it is stated that Lorde’s speech contributed to communication with scholars’ understanding of human biases. While “anger, marginalized communities, and US Culture” are the major themes of the speech, Lorde implemented various communication techniques to shift subjectivities of the “white feminist” audience. Lorde further explained that “we are working in a context of oppression and threat, the cause of which is certainly not the angers which lie between us, but rather that virulent hatred leveled against all women, people of color, lesbians and gay men, poor people—against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions, moving towards coalition and effective action.”

Audre Lorde and critique of womanism

A major critique of womanism is its failure to explicitly address homosexuality within the female community. Very little womanist literature relates to lesbian or bisexual issues, and many scholars consider the reluctance to accept homosexuality accountable to the gender simplistic model of womanism. According to Lorde’s essay “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” “the need for unity is often misnamed as a need for homogeneity.” She writes, “A fear of lesbians, or of being accused of being a lesbian, has led many Black women into testifying against themselves.”

Contrary to this, Audre Lorde was very open to her own sexuality and sexual awakening. In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, her famous “biomythography” (a term coined by Lorde that combines “biography” and “mythology”) she writes, “Years afterward when I was grown, whenever I thought about the way I smelled that day, I would have a fantasy of my mother, her hands wiped dry from the washing, and her apron untied and laid neatly away, looking down upon me lying on the couch, and then slowly, thoroughly, our touching and caressing each other’s most secret places.” According to scholar Anh Hua, Lorde turns female abjection—menstruation, female sexuality, and female incest with the mother—into powerful scenes of female relationship and connection, thus subverting patriarchal heterosexist culture.

With such a strong ideology and open-mindedness, Lorde’s impact on lesbian society is also significant. An attendee of a 1978 reading of Lorde’s essay “Uses for the Erotic: the Erotic as Power” says: “She asked if all the lesbians in the room would please stand. Almost the entire audience rose.”

The Callen-Lorde Community Health Center is an organization in New York City named for Michael Callen and Audre Lorde, which is dedicated to providing medical health care to the city’s LGBT population without regard to ability to pay. Callen-Lorde is the only primary care center in New York City created specifically to serve the LGBT community.

The Audre Lorde Project, founded in 1994, is a Brooklyn-based organization for queer people of color. The organization concentrates on community organizing and radical nonviolent activism around progressive issues within New York City, especially relating to queer and transgender communities, AIDS and HIV activism, pro-immigrant activism, prison reform, and organizing among youth of color.

The Audre Lorde Award is an annual literary award presented by Publishing Triangle to honor works of lesbian poetry, first presented in 2001.

In 2014 Lorde was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago, Illinois that celebrates LGBT history and people.

#AmericanWriters #BlackWriters #FemaleWriters

- Audre Lorde: Empowering Feminism Through Poetry

Audre Lorde , a prominent African American poet, writer, and activist, left an indelible mark on the world of feminist literature. Through her powerful and evocative poetry, Lorde explored the complexities of identity, race, sexuality, and gender, making her a pioneer in the feminist movement. Her poems continue to resonate with readers, challenging societal norms and inspiring women to embrace their authentic selves. This article delves into Lorde's poems about feminism, showcasing her unique perspective and unwavering commitment to social justice.

1. "A Litany for Survival"

2. "sister outsider", 3. "power".

One of Audre Lorde's most renowned poems is "A Litany for Survival." In this emotionally charged piece, Lorde emphasizes the importance of strength and resilience in the face of oppression. She speaks directly to marginalized women, calling for unity and empowerment. Here is an excerpt:

For those of us who live at the shoreline , standing upon the constant edges of decision, crucial and alone, for those of us who cannot indulge the passing dreams of choice, who love in doorways coming and going, in the hours between dawns, looking inward and outward, at once before and after, seeking a now that can breed futures like bread in our children's mouths so their dreams will not reflect the death of ours.

In this powerful verse, Lorde emphasizes the experiences of women who are denied agency and forced to navigate life's challenges alone. She highlights the importance of fighting for a better future for oneself and future generations.

In her collection of essays and speeches titled "Sister Outsider," Audre Lorde explores the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality. While not a poem in itself, this collection is an essential read for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of Lorde's feminist perspective. It contains her famous essay, "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House," which challenges the limitations of mainstream feminism and calls for inclusive activism.

In "Power," Audre Lorde delves into the complexities of power dynamics and the impact they have on marginalized communities. She highlights the necessity of acknowledging one's power and using it to effect positive change. Here is an excerpt:

I have not been able to touch the destruction within me. But unless I learn to use the difference between poetry and rhetoric my power too will run corrupt as poisonous mold or lie limp and useless as an unconnected wire and one day I will take my teenaged plug and connect it to the nearest socket raping an 85 year old white woman who is somebody's mother and as I beat her senseless and set a torch to her bed a greek chorus will be singing in 3/4 time "Poor thing. She never hurt a soul. What beasts they are."

In this poignant poem, Lorde confronts the potential for power to be misused and abused. She calls for individuals to harness their power for justice and equality rather than perpetuating harm.

Audre Lorde's poems about feminism demonstrate her unwavering commitment to challenging societal norms and fighting for equality. Through her evocative words, she empowers marginalized women and encourages them to embrace their identities fully. Lorde's poetry continues to inspire generations of feminists, serving as a reminder that literature can be a powerful tool for social change.

- Funny Poems About Moms from Daughters: Celebrating the Comical Side of Motherhood

- Poems That Embrace Non-Violence: Spreading Harmony Through Words

Entradas Relacionadas

Famous Poems About Sexism: A Powerful Exploration of Gender Inequality

Poetry Unveiling Gender Inequality: An Unfiltered Reflection

The Feminist Poetry of Carol Ann Duffy

Rupi Kaur: Empowering Feminism Through Poetry

Poems About Double Standards: Unveiling Societal Hypocrisy Through Poetry

Poems that Challenge and Explore Gender Roles

Audre Lorde

Poet and author Audre Lorde used her writing to shine light on her experience of the world as a Black lesbian woman and later, as a mother and person suffering from cancer. A prominent member of the women’s and LGBTQ rights movements, her writings called attention to the multifaceted nature of identity and the ways in which people from different walks of life could grow stronger together.

Audrey Geraldine Lorde was born on February 18, 1934 to Frederic and Linda Belmar Lorde, immigrants from Grenada. She was the youngest of three sisters and grew up in Manhattan. As a child, Lorde dropped the “y” from her first name to become Audre.

Lorde connected with poetry from a young age. She once commented, “I used to speak in poetry...when I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry.” She was around 12 or 13 at the time. She graduated from Hunter High School, where she edited the literary magazine. After an English teacher rejected one of her poems, Lorde submitted it to Seventeen magazine – it became her first professional publication.

After working a variety of jobs in New York and Connecticut, Lorde studied for a year at the National University of Mexico in Cuernavaca. It was there that she grew confident in her identity as both a lesbian and a poet. Lorde then earned her bachelor’s degree from Hunter College and a master’s degree in library science from Columbia University. She worked as a librarian in New York City public schools from 1961-1968.

In 1962, Lorde married Edwin Rollins, a white, gay man, and they had two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. Lorde and Rollins divorced in 1970.

During the 1960s, Lorde began publishing her poetry in magazines and anthologies, and also took part in the civil rights, antiwar, and women’s liberation movements. Lorde published her first volume of poems, The First Cities , in 1968. That same year, she earned a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and became the writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College, a historically Black college in Mississippi. There, she discovered her love of teaching and met Frances Clayton, a professor of psychology and her partner until 1989.

Lorde’s work was already notable for her strong expressions of African American identity, but her second anthology, Cables to Rage (1970), took on more overtly political themes, such as racism, sexism, and violence. It also included “Martha,” a poem that acknowledged her lesbianism. Her third collection, From a Land Where Other People Live (1973), was a finalist for a National Book Award for Poetry. Lorde’s work is characterized by its emphasis on matters of social and racial justice, as well as its authentic portrayal of queer sexuality and experience.

Lorde continued writing prolifically through the 1970s and 1980s, exploring the intersections of race, gender, and class, as well as examining her own identity within a global context. Her 1978 collection, The Black Unicorn , was inspired by a trip to Benin with her children. In it, she drew strength from a spiritual connection with the goddesses of African mythology. In 1982, Lorde released what she coined a “biomythography”: Zami: A New Spelling of My Name . Combining elements of history, biography, and myth, it told of Lorde’s journey of self-discovery and acceptance as a Black lesbian in her childhood and young adult years. Lorde’s 1984 collection, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches , included her canonical essay, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” which called on feminists to acknowledge the many differences among women and to utilize them as a source of power rather than one of division.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 1977, Lorde found that the ordeals of cancer treatment and mastectomy were shrouded in silence for women, and found them even further isolating as a Black lesbian woman. Lorde felt that the narratives of coping and healing she did encounter were designed solely for white, heterosexual women. In an effort to combat this silence and to foster connection with other lesbians and women of color facing the same struggle, Lorde offered a raw portrait of her own pain, suffering, reflection, and hope in The Cancer Journals (1980). The book won the American Library Association’s Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award for 1981 and became a classic work of illness narrative.

Lorde’s advocacy on behalf of women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community continued outside her literary career as well. In 1979, she was a prominent speaker at the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. In 1981, with Barbara Smith and several other writers, Lorde founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. Kitchen Table was devoted to promoting feminists of color and their writings. Lorde was also a founding member of Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa, an organization that advocated on behalf of women living under apartheid.

Lorde was a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Hunter College. She received many honors throughout her career including the 1990 Bill Whitehead Memorial Award and the 1991 Walt Whitman Citation of Merit, making her the Poet Laureate of the State of New York for 1991-1992. Her 1988 prose collection A Burst of Light won a Before Columbus Foundation National Book Award. Lorde earned honorary doctorates from Hunter College, Oberlin College, and Haverford College. In 2001, the Publishing Triangle association instituted the Audre Lorde Award for distinguished works of lesbian poetry. Lorde was posthumously elected to the American Poets Corner at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City in 2020.

Lorde’s cancer returned and she passed away in 1992. Shortly before her death, she participated in an African naming ceremony in which she took the name Gamba Adisa. Befitting the writer who continually explored and expressed her self-identity, it means “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known.”

Published June 2021.

Works Cited:

“Audre Lorde, 58, A Poet, Memoirist And Lecturer, Dies.” The New York Times . November 20, 1992. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/20/books/audre-lorde-58-a-poet-memoirist-and-lecturer-dies.html

“Audre Lorde.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/audre-lorde

“Audre Lorde.” Poets.org. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://poets.org/poet/audre-lorde

“Audre Lorde, New York State Poet Laureate, Dead at 58.” AP News. November 18, 1992. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/a04031e9d7cfbb38fb4af5859d3257d5

Lorde, Audre. 2018. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House . Penguin Modern. London, England: Penguin Classics.

Sullivan, James D. "Lorde, Audre (1934-1992), poet, essayist, and feminist." American National Biography. Jan. 1, 2003; Accessed May 6, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1603482

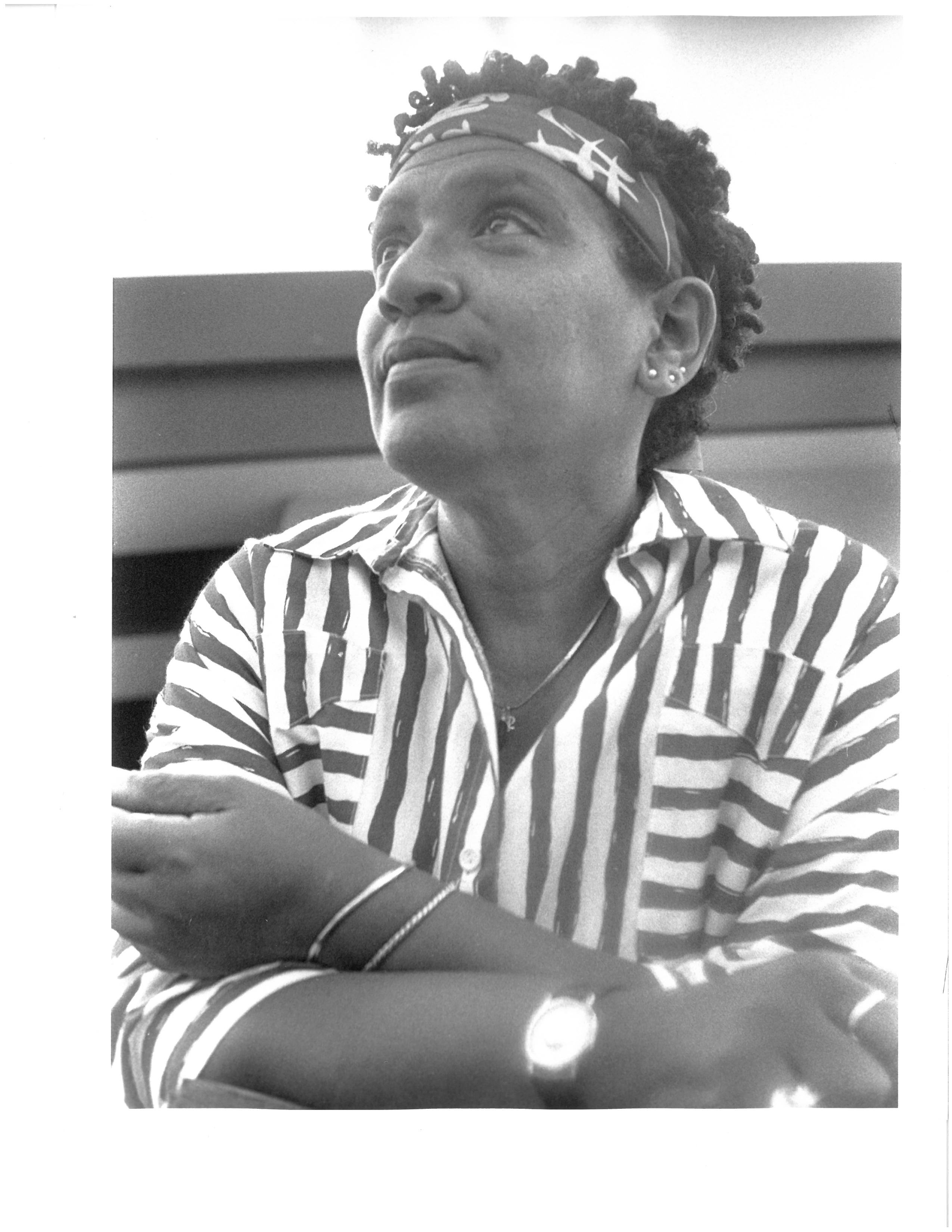

Photo credit: "Audre Lorde" by K. Kendall is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/07aa8e3d-9e7d-490a-b36e-0fc622482670

How to Cite this page:

MLA – Brandman, Mariana. “Audre Lorde.” National Women’s History Museum, 2021. Date accessed.

Chicago – Brandman, Mariana. “Audre Lorde.” National Women’s History Museum. 2021. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/audre-lord

Additional Resources:

De Veaux, Alexis. Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde . New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

Audre Lorde Collection, 1950-2002. Spelman College Archives. https://www.spelman.edu/docs/archives-guides/audre-lorde-collection-finding-aid---2020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=61876f51_0

Lorde, Audre., Gay, Roxane. The Selected Works of Audre Lorde . United States: W. W. Norton, 2020.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Maya Angelou

Related background, “when we sing, we announce our existence”: bernice johnson reagon and the american spiritual', mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, women’s rights lab: black women’s clubs.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Audre Lorde

Poet, essayist, and novelist Audre Lorde was born Audrey Geraldine Lorde on February 18, 1934, in New York City. Her parents were immigrants from Grenada. The youngest of three sisters, she was raised in Manhattan and attended Catholic school. While she was still in high school, her first poem appeared in Seventeen magazine. Lorde received her BA from Hunter College and an MLS from Columbia University. She served as a librarian in New York public schools from 1961 through 1968. In 1962, Lorde married Edward Rollins. They had two children, Elizabeth and Jonathon, before divorcing in 1970.

Her first volume of poems, The First Cities (Poets Press), was published in 1968. In the same year, she became the writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, where she discovered a love of teaching. At Tougaloo, she also met her long-term partner, Frances Clayton. The First Cities was quickly followed with Cables to Rage (Paul Breman, 1970) and From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press, 1973), which was nominated for a National Book Award. In 1974, she published New York Head Shot and Museum (Broadside Press). Whereas much of her earlier work focused on the transience of love, this book marked her most political work to date.

In 1976, W. W. Norton released her collection Coal and, shortly thereafter, published The Black Unicorn (1995). Poet Adrienne Rich said of The Black Unicorn that “Lorde writes as a Black woman, a mother, a daughter, a Lesbian, a feminist, a visionary; poems of elemental wildness and healing, nightmare and lucidity.” Her other volumes include Chosen Poems Old and New (1982) and Our Dead Behind Us (1986), both published by W. W. Norton. Poet Sandra M. Gilbert noted not only Lorde’s ability to express outrage, but also that she was capable of “of rare and, paradoxically, loving jeremiads.”

Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer and chronicled her struggles in her first prose collection, The Cancer Journals (Spinsters, Ink, 1980), which won the Gay Caucus Book of the Year award for 1981. Her other prose volumes include Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Crossing Press, 1982), Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press, 1984), and A Burst of Light (Firebrand Press, 1988), which won a National Book Award. She received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1981.

In the 1980s, Lorde and writer Barbara Smith founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. She was also a founding member of Sisters in Support of Sisters in South Africa, an organization that worked to raise concerns about women under apartheid.

Audre Lorde was a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Hunter College. She was the poet laureate of New York from 1991–92. She died of breast cancer in 1992. The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (W. W. Norton) was published in 1997. In 2021, Lorde was inducted to the American Poets Corner at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Related Poets

Newsletter sign up.

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

- Poems & Essays

- Poetry in Motion NYC

Home > Poems & Essays > On Poetry > Carl Phillips on Audre Lorde

Carl Phillips on Audre Lorde

In May of 1970, Audre Lorde visited Fassett Studio to record a reading for Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room .

The Fonograf Editions 12″ LP of this reading includes a 12-page liner notes booklet with poems by Fred Moten and Pamela Sneed; and essays by Tongo Eisen-Martin, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and Carl Phillips, whose essay is reprinted here.

Carl Phillips on Audre Lorde Until listening to this recording, I’d never heard Audre Lorde’s speaking voice. I don’t think I had any particular preconceptions of how she’d sound. I just hoped she wouldn’t disappoint me the way so many of my poetry idols have, once I’ve heard them read; it’s amazing how many poets seem unable to read their own work well, by which I mean with a confidence that doesn’t shun humility, and with a persuasiveness that avoids sounding pedantic.