- Research Guides

Literature Review: A Self-Guided Tutorial

Using concept maps.

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Peer Review

- Reading the Literature

- Developing Research Questions

- Considering Strong Opinions

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Super Searching

- Finding the Full Text

- Citation Searching This link opens in a new window

- When to stop searching

- Citation Management

- Annotating Articles Tip

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- How to Review the Literature

- Using a Synthesis Matrix

- 7. Write literature review

Concept maps or mind maps visually represent relationships of different concepts. In research, they can help you make connections between ideas. You can use them as you are formulating your research question, as you are reading a complex text, and when you are creating a literature review. See the video and examples below.

How to Create a Concept Map

Credit: Penn State Libraries ( CC-BY ) Run Time: 3:13

- Bubbl.us Free version allows 3 mind maps, image export, and sharing.

- MindMeister Free version allows 3 mind maps, sharing, collaborating, and importing. No image-based exporting.

Mind Map of a Text Example

Credit: Austin Kleon. A map I drew of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing in 2008. Tumblr post. April 14, 2016. http://tumblr.austinkleon.com/post/142802684061#notes

Literature Review Mind Map Example

This example shows the different aspects of the author's literature review with citations to scholars who have written about those aspects.

Credit: Clancy Ratliff, Dissertation: Literature Review. Culturecat: Rhetoric and Feminism [blog]. 2 October 2005. http://culturecat.net/node/955 .

- << Previous: Reading the Literature

- Next: 1. Identify the question >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.williams.edu/literature-review

Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

- Choosing a Type of Review

- Developing a Research Question

- Searching the Literature

- Searching Tips

- ChatGPT [beta]

- Documenting your Search

- Using Citation Managers

- Concept Mapping

- Concept Map Definition

MindMeister

- Writing the Review

- Further Resources

Additional Tools

Google slides.

GSlides can create concept maps using their Diagram feature. Insert > Diagram > Hierarchy will give you some editable templates to use.

Tutorial on diagrams in GSlides .

MICROSOFT WORD

MS Word can create concept maps using Insert > SmartArt Graphic. Select Process, Cycle, Hierarchy, or Relationship to see templates.

NVivo is software for qualitative analysis that has a concept map feature. Zotero libraries can be uploaded using ris files. NVivo Concept Map information.

A concept map or mind map is a visual representation of knowledge that illustrates relationships between concepts or ideas. It is a tool for organizing and representing information in a hierarchical and interconnected manner. At its core, a concept map consists of nodes, which represent individual concepts or ideas, and links, which depict the relationships between these concepts .

Below is a non-exhaustive list of tools that can facilitate the creation of concept maps.

www.canva.com

Canva is a user-friendly graphic design platform that enables individuals to create visual content quickly and easily. It offers a diverse array of customizable templates, design elements, and tools, making it accessible to users with varying levels of design experience.

Pros: comes with many pre-made concept map templates to get you started

Cons : not all features are available in the free version

Explore Canva concept map templates here .

Note: Although Canva advertises an "education" option, this is for K-12 only and does not apply to university users.

www.lucidchart.com

Lucid has two tools that can create mind maps (what they're called inside Lucid): Lucidchart is the place to build, document, and diagram, and Lucidspark is the place to ideate, connect, and plan.

Lucidchart is a collaborative online diagramming and visualization tool that allows users to create a wide range of diagrams, including flowcharts, org charts, wireframes, and mind maps. Its mind-mapping feature provides a structured framework for brainstorming ideas, organizing thoughts, and visualizing relationships between concepts.

Lucidspark , works as a virtual whiteboard. Here, you can add sticky notes, develop ideas through freehand drawing, and collaborate with your teammates. Has only one template for mind mapping.

Explore Lucid mind map creation here .

How to create mind maps using LucidSpark:

Note: U-M students have access to Lucid through ITS. [ info here ] Choose the "Login w Google" option, use your @umich.edu account, and access should happen automatically.

www.figma.com

Figma is a cloud-based design tool that enables collaborative interface design and prototyping. It's widely used by UI/UX designers to create, prototype, and iterate on digital designs. Figma is the main design tool, and FigJam is their virtual whiteboard:

Figma is a comprehensive design tool that enables designers to create and prototype high-fidelity designs

FigJam focuses on collaboration and brainstorming, providing a virtual whiteboard-like experience, best for concept maps

Explore FigJam concept maps here .

Note: There is a " Figma for Education " version for students that will provide access. Choose the "Login w Google" option, use your @umich.edu account, and access should happen automatically.

www.mindmeister.com

MindMeister is an online mind mapping tool that allows users to visually organize their thoughts, ideas, and information in a structured and hierarchical format. It provides a digital canvas where users can create and manipulate nodes representing concepts or topics, and connect them with lines to show relationships and associations.

Features : collaborative, permits multiple co-authors, and multiple export formats. The free version allows up to 3 mind maps.

Explore MindMeister templates here .

- << Previous: Using Citation Managers

- Next: Writing the Review >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 10:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/litreview

Introduction to Academic Reading and Writing: Concept Map

- Concept Map

- Select a Topic

- Develop a Research Question

- Identify Sources

- Thesis Statements

- Effective Paragraphs

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Quote, Paraphrase, Summarize

- Synthesize Sources

- MLA and APA

- Transitions

- Eliminate Wordiness

- Grammar and Style

- Resource Videos

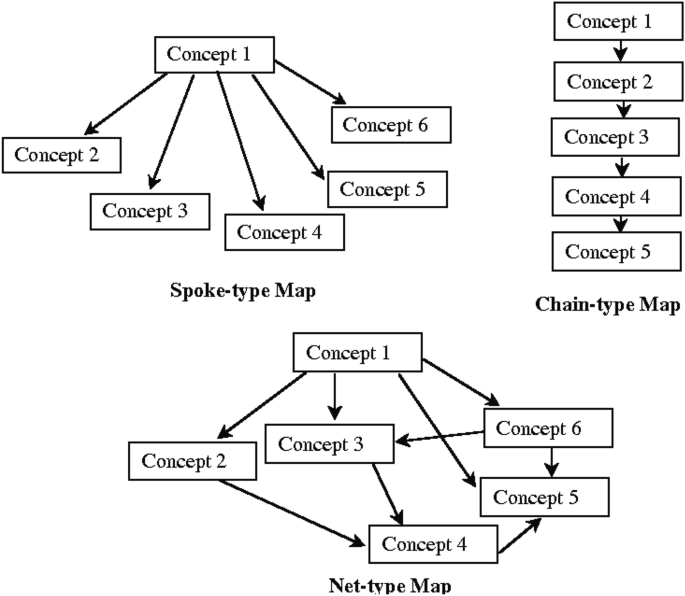

Concept Maps

Create a concept map using your annotations and highlights of the text .

Define your map’s focus question and topic. Your focus question guides your map in a certain direction. What is the purpose of what you read? Your topic is what you are reading about.

Create a list of relevant concepts, thoughts and implications of your topic as you read. , think about the relationships between these concepts and begin to organize the list of concepts from broad to specific. you can set a topic at the center, with supporting points and details branching outwards, or you can create a hierarchy, with the topic at the top and its components below. , add links and cros s -links between related concepts and label these links with words or phrases to clarify the relationship between concepts., color code, add symbols, and personalize to your map so that is meaningful to you..

Check out these free online Concept Mapping tools:

- Lucid Chart

Video by McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph, 2017 .

Concept Map Example

Map by Penn State University , Concept Maps iStudy Tutorial

- << Previous: Annotate

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 12:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lbc.edu/Introtoacademicreadingandwriting

Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- Concept Mapping

- Writing a Proposal

- For Faculty

Need help? Ask a librarian

Concept map example: Chocolate Purchasing Factors

What is concept mapping.

Concept Maps are a way to graphically represent ideas and how they relate to each other.

Concept maps may be simple designs illustrating a central theme and a few associated topics or complex structures that delineate hierarchical or multiple relationships.

J.D. Novak developed concept maps in the 1970's to help facilitate the research process for his students. Novak found that visually representing thoughts helped students freely associate ideas without being blocked or intimidated by recording them in a traditional written format.

Concept mapping involves defining a topic; adding related topics; and linking related ideas

Use Bubbl.us or search for more free mind-mapping tools on the web.

More Examples of Concept Maps

- Govt Factors in Consumer Choice

- Mental Health

- Social Psychology

- << Previous: Examples

- Next: Writing a Proposal >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 8:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.njit.edu/literaturereview

- Directories

- Concept mapping

- Lit review-type sources

- Grey literature

- Public affairs news

- Discipline-specific tools

- Writing & research help

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Literature review toolkit for policy studies

Literature review toolkit for policy studies: Concept mapping

Why create a concept map.

A concept map is a visualization of key idea in your research and the relationships between them. To create a concept map, pick out the main concepts of your topic and brainstorm everything you know about them, drawing shapes around your concepts and clustering the shapes in a way that's meaningful to you. How can this help?

- Helps you pull back to see the broader concepts at play.

- Can help identify the subject-based tool where literature can be found.

- Helps clarify both what you already know and where you have gaps in your knowledge.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Lit review-type sources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 26, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/litreviewtoolkit

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

A literature review of open-ended concept maps as a research instrument to study knowledge and learning

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2021

- Volume 56 , pages 73–107, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Kirsten E. de Ries ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6210-5604 1 ,

- Harmen Schaap 2 ,

- Anne-Marieke M. J. A. P. van Loon 1 ,

- Marijke M. H. Kral 1 &

- Paulien C. Meijer 2

12k Accesses

13 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In educational, social or organizational studies, open-ended concept maps are used as an instrument to collect data about and analyze individuals’ conceptual knowledge. Open-ended concept map studies devoted to knowledge and learning apply a variety of methods of analysis. This literature review systematically summarizes the various ways in which open-ended concept maps have been applied in previous studies of knowledge and learning. This paper describes three major aspects of these studies: what methods of analysis were used, what concept map characteristics were considered, and what conclusions about individuals’ knowledge or understanding were drawn. Twenty-five studies that used open-ended concept maps as a research instrument were found eligible for inclusion. In addition, the paper examines associations between the three aspects of the studies and provides guidelines for methodological coherence in the process of such analysis. This review underscores the importance of expatiating on choices made concerning these aspects. The transparency provided by this method of working will contribute to the imitable application of open-ended concept maps as a research tool and foster more informed choices in future open-ended concept map studies.”

Similar content being viewed by others

A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis

David Byrne

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

Drishti Yadav

How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others

Brian E. Neubauer, Catherine T. Witkop & Lara Varpio

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

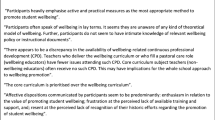

Concept maps were introduced by Novak and Gowin to activate or elaborate (prior) knowledge. “Concept maps are graphical tools for organizing and representing knowledge. They include concepts, usually enclosed in circles or boxes of some type, and relationships between concepts indicated by a connecting line linking two concepts” (Novak and Cañas 2008 , p.1). Concept maps have a wide variety of applications and are an increasingly popular learning and strategy tool (e.g. Novak and Cañas 2008 ; Stevenson, Hartmeyer and Bentsen 2017 ). It is on the rise as an instructional method (e.g. Nair and Narayanasamy 2017 ), to aid in curriculum design (e.g. Buhmann and Kingsbury 2015 ) and as an assessment tool (e.g. Marriott and Torres 2016 ). In recent years, concept maps have been used more widely as a research instrument. This includes the application of concept maps to study knowledge, explore mental models and misconceptions, or to describe people’s opinions. Figure 1 provides an example of a concept map. The focus question or prompt for the example in Fig. 1 could have been “What is a concept map?” or the topic provided could have been ‘Concept maps’.

Example of a hierarchical concept map by Ed Dole (adapted from Dori 2004 )

The words enclosed in circles are concepts, also referred to as nodes. These concepts are connected with arrows, or links, that are indicated with linking words, explaining the relation between the concepts. A proposition is a concept-link-concept combination, for instance ‘concept maps–include—hierarchies’. In this example, there are four hierarchies or strings of concepts stemming from the root concept ‘concept maps’. Links between concepts from the same hierarchy are called links. Links between concepts from different hierarchies are cross-links.

A concept map assignment includes: concepts or nodes, links or linking lines, linking phrases, and the concept map structure, and all these aspects can be either respondent driven or provided by the instructor (Ruiz-Primo 2000 ). For instance respondents think of concepts themselves, or are provided a list of concepts they can use for their concept map. In most studies that apply concept maps, at least one of these four aspects of the task is instructor-directed; most commonly, the concepts to be used are provided (Ruiz-Primo et al. 2001 ). In open-ended concept maps respondents choose their own terms for nodes, links or linking lines, linking phrases and structure, therefore they resemble the respondents’ knowledge structure (Cañas, Novak and Reiska 2013 ; Ruiz-Primo et al. 2001 ). Open-ended concept maps are graphical tools in which respondents are invited to represent their personal construction of knowledge, without instructor-directed aspects. In an open-ended concept map assignment, only a topic or prompt is provided to the respondents. For instance Ifenthaler, Masduki and Seel ( 2011 ) asked respondents to create a concept map to depict their understanding of research skills, Beyerbach ( 1988 ) asked students to draw a concept map for teacher planning and Çakmak ( 2010 ) asked respondents to generate a concept map concerning teacher roles in teaching process.

Open-ended concept maps are commonly applied to explore student knowledge, to evaluate what or how students learn or to explore misconceptions in student knowledge (Greene et al. 2013 ; Stevenson et al. 2017 ). The application of open-ended concept maps to study knowledge and learning faces new challenges concerning application and analysis, as this application transcends the traditional, strictly defined, quantitative use of concept maps in other domains, such as engineering, mathematics and psychology (Wheeldon and Faubert 2009 ). When exploring knowledge and learning, the strictly defined quantitative use of concept maps is believed not to do justice to the personal and idiosyncratic nature of people’s understanding (Novak 1990 ). Open-ended concept maps are therefore used to study people’s knowledge and understanding of complex phenomena, such as leadership or inclusive education. They are also used when respondents’ knowledge is expected to be fragmented, or when the misconceptions and/or limited nature of people’s understanding are part of the study (Greene et al. 2013 ; Kinchin, Hay and Adams 2000 ).

The variation in outcomes using open-ended concept maps as a research instrument reduces the comparability and leads to difficulty in data analysis (Watson et al. 2016a ; Yin et al. 2005 ). Previous studies describe limitations concerning methods of analysis. Several studies argue that quantitative analysis neglects the quality or meaning and learning (Bressington, Wells and Graham 2011 ; Buhmann and Kingsbury 2015 ; Kinchin et al. 2000 ). Others argue that it is an insufficient evaluation of values or perceptions as expressed by respondents (Jirásek et al. 2016 ). Some studies address contradicting outcomes when methods of analysis are compared, and they question the validity and reliability of concept map analysis and concept maps as a research instrument (Ifenthaler et al. 2011 ; Kinchin 2016 ; Watson et al. 2016a ; West et al. 2002 ). Cetin, Guler and Sarica ( 2016 ) claim that it is unclear how the reliability and validity of open-ended concept map analysis can be determined. Additionally, Ifenthaler et al. ( 2011 ) argue that some of the methods of analysis applied in previous studies have questionable reliability and validity. Tan, Erdimez and Zimmerman ( 2017 ) complement these statements by addressing the lack of clarity they perceived in the existing methods of analysis when choosing a method of analysis for their study.

This literature review explores the analysis of open-ended concept maps in previous studies. Firstly, we contemplate what aspects of the process of analysis to consider for this review, based on the quality appraisal of the process of analysis in qualitative research. Creswell ( 2012 ) emphasizes the interrelation of the steps concerning data gathering, interpretation and analysis in qualitative research. Accordingly, Huberman and Miles ( 2002 ) proposed three central validities for assessing the quality of qualitative research: descriptive, interpretative and theoretical. These are respectively concerned with the data collected or the characteristics of the data that are considered, how data are interpreted or analyzed, and the conclusions that are drawn. These three aspects should be aligned or coherent to increase the quality of research, and are therefore explored in previous open-ended concept map studies. The method of analysis applied, concept map characteristics measured, and conclusions drawn, and the associations between these aspects are explored (Chenail, Duffy, George and Wulff 2011 ; Coombs 2017 ). The research question is: Which methods of analysis are applied to open-ended concept maps when studying knowledge and learning, and how are these associated with concept map characteristics considered and conclusions drawn?

To answer the research question, we extract information concerning method of analysis applied, concept map characteristics measured, and conclusions drawn from previous open-ended concept map studies. Following guidelines for critical interpretative synthesis reviews, this review combines an aggregative and interpretative approach to critically understand the analysis in previous studies (Gough and Thomas 2012 ). The aggregation entails the representation of clusters for each aspect based on cross-case analysis, as presented in the results. Subsequently, patterns among these aspects are explored and interpreted, leading to considerations for future studies concerning these three aspects and their methodological coherence.

2.1 Selecting articles (inclusion)

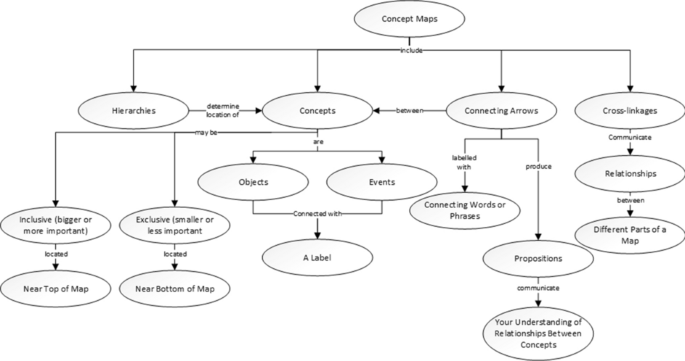

This review applies a comprehensive search strategy to include all relevant studies (Verhage and Boels 2017 ). Scientific articles are selected from three databases: the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC); PsycINFO; and the Web of Science (WOS). The keywords for the search are ‘concept map’, and ‘analysis’ or ‘assessment’ or ‘scoring’. Studies are included from 1984 onward, when Novak and Gowin established the term ‘concept map.’ Due to the broad social science disciplines included in WOS, a further selection is made based on the predetermined WOS Category ‘Education educational research’, to exclude for instance geographical studies that map cities, and are not concerned with knowledge or learning but spatial planning. The combined search yields 451 studies in ERIC, 198 studies in PsycINFO and 498 studies in WOS.

Three reviews of concept maps studies are used in a selective search strategy: the open-ended concept map studies described in these reviews are included in this study (Anohina and Grundspenkis 2009 ; Ruiz-Primo and Shavelson 1996 ; Strautmane 2012 ). Based on the snowballing technique with these reviews, 85 additional studies are included, and 1316 in total, as depicted in Fig. 2 . The first review by Anohina and Grundspenkis ( 2009 ) presented manual methods of analysis, and addressed the feasibility of automating these methods. The reviews by Ruiz-Primo and Shavelson ( 1996 ) and Strautmane ( 2012 ) related methods of analysis to the openness of the concept mapping assignments. These reviews did not explore the associations between the methods of analysis and the conclusions drawn in these studies. Our review is one of the first to address the associations between the methods of analysis, the concept map characteristics considered and the conclusions drawn, instead of focusing on these aspects separately. This coherence is relevant to explore as it enhances the rigor and quality of qualitative studies, by ensuring an appropriate alignment of these aspects within studies (Davis 2012 ; Poucher et al. 2020 ).

Search and selection strategy

2.2 Screening articles (exclusion)

The selected articles are screened. 254 duplicates are excluded. Next titles and abstracts are screened. In order to increase the quality of this process, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are discussed with co-researchers until consensus is reached. 703 articles did not apply concept maps, or concept maps were used as learning tool, instructional tool, for curriculum design or to analyze answers, texts or interviews. These are excluded. For the remaining 359 studies that apply concept maps as research instrument, step 2 of the screening is based on the methods section. Studies are included based on the following inclusion criteria:

Concept maps were used as a research instrument;

The study was an empirical study;

Respondents made their own concept map; and

An open-ended concept map assignment was applied.

In seven studies, other visual drawings than concept maps were used. In 31 studies, concept map analysis was described based on theory instead of empirical data. In 71 studies, concepts map were constructed by the researcher based on interviews, together with the respondent during an interview or at group level based on card sorting techniques. In 154 studies, at least one of the aspects of the concept mapping task was instructor-directed. Studies are included if one or more focus questions or one central concept was provided.

The critical appraisal of the methods section, leads to two additional exclusion criteria (Verhage and Boels 2017 ). Seventy studies applied another research instrument alongside concept maps. For these studies, the results sections are read to discover whether concept maps were evaluated separately. In 30 studies, concept map analysis was combined with interviews or reflective notes. 36 studies compared concept map scores with results from other research instruments, such as knowledge tests or interviews. These studies were excluded because the method of analysis or conclusions for the concept maps was not described separately. This is problematic for our research purposes, as this study is concerned with concept map analysis and conclusions based on concept maps analysis, and not analysis and conclusions based on other instruments. Four studies that applied two instruments—but reported on the analysis of concept maps separately—are included.

For step 3 of the selection process, the full texts of the remaining 30 studies are read. Five studies are excluded; in two studies, different concept map characteristics are summed up and not described separately. One study calculated correlations between different concept map characteristics, and two studies drew conclusions purely on group level, resulting in 25 studies being included in this review, as depicted in Fig. 2 .

2.3 Data selection from articles

Information on the following topics is extracted from the articles: the method of analysis, the concept map characteristics, the conclusions, the rationale behind the choices made, and general or descriptive information. A data selection scheme is developed which depicts the extracted information (Table 1 ). To increase the reliability of the data selection, this scheme was continuously discussed and adjusted by the authors over the entire selection process. Reliability was further ensured by using signal words, based on common terms used in the studies. For three of the studies included, the data selection was performed independently by two researchers. Both researchers selected statements from the articles concerning the items described in Table 1 . One researcher included 79 statements and the other 94 statements. The statements selected by the researchers overlapped completely. The 15 statements only selected by one researcher were discussed and added to the data. A total of 109 citations were extracted from these three studies.

2.4 Data analysis

Data analysis is performed by using the selected articles for within- and cross-case analysis (Miles and Huberman 1994 ). In this review, the cases are the articles included. The first step of analysis is to order the extracted information in a meta-matrix (see " Appendix A ") that presents all relevant condensed data for each case or article separately (Miles and Huberman 1994 ). If no explicit statements are found, information is added by using the within-case analytic strategy of ‘overreading’ (Ayres, Kavanaugh and Knafl 2003 ). For instance, for a study that counted specific concept map characteristics but did not describe the method of analysis any further, the method of analysis was described as quantitative analysis. To prepare data for cross-case analysis, different labels for the same aspect are unified. For instance, ‘counting nodes’ is relabeled as ‘number of nodes.’

The second step entails coding the selected statements concerning the research object, research design, methods of analysis, concept map characteristics, and conclusions drawn in the articles, using a cross-case analysis approach. Preliminary coding of statements concerning methods of analysis is based on the way studies refer to their method of analysis. However, the same term was sometimes used to refer to more than one analysis method, while in other cases, multiple terms were used to refer to a single method. Thus, the designation of clusters based on how the studies referred to their methods of analysis proved inconclusive and ambiguous.

Different distinctions between methods of analysis are found in the literature. For example, in the review by Anohina and Grundspenkis ( 2009 ) the use of an expert’s map is one choice, as well as the choice for quantitative or qualitative analysis and structural or relational analysis, to make a distinction between methods of analysis. In the review by Strautmane ( 2012 ), the criteria for similarity analysis, e.g. “proposition similarity to expert’s CM”, or “convergence with expert’s CM”, are described as separate criteria. Also in the review by Ruiz-Primo and Shavelson ( 1996 ), comparison with a criterion map, is described as a separate method of analysis. In this review, the distinction between quantitative, qualitative, similarity and holistic analysis is chosen, as these methods of analysis consider the concept map characteristics distinctively and they are based on different principles and theoretical assumptions. Holistic analysis is a separate method of analysis, as it is based on a rubric, and similarity is a separate analysis, as it is based on a reference map. Moreover, these four methods of analysis lead to different types of conclusions, and are therefore considered as distinctive ways to analyze and interpret data from concept maps. In conceptual terms, these four methods of analysis are mutually exclusive, as they estimate the concept map characteristics differently. However, when applied to analyze data, they can be combined: similarity analysis compares concept maps to a reference map, either qualitatively or quantitatively.

The statements concerning concept map characteristics are unified; for instance, ‘breadth and depth’ or ‘hierarchical structure of the map’ were both coded as structural complexity. All concept map characteristics related to the semantic content of the map, referred to as ‘terms used’, ‘content comprehensiveness’, ‘correctness’ or ‘sophistication’, are clustered as semantic sophistication. The conclusions are clustered in the same way as the methods of analysis. Conclusions about numbers of concept map characteristics are labelled as quantitative, conclusions about descriptions are labelled as qualitative, conclusions about overlap with a reference map are labeled as similarity and conclusions about the quality of the map as a whole are labelled as holistic.

For the same three studies that two researchers selected statements from independently, the statements were coded by two researchers independently. A total of 109 statements were coded. Krippendorf’s alpha of the inter-rater agreement was 0.91. The discrepancies in coding were all related to concept map characteristics. For instance, counting cross-links was coded as interlinkage by one researcher and as structural complexity by the other researcher, while the validity of links was labeled as semantic sophistication by one researcher and category representation by the other. The first author coded the data from the remaining 22 articles included in the review and consulted the co-authors when in doubt.

The third step of the analysis was exploring the associations between the methods of analysis, concept map characteristics and conclusions drawn. Across all articles, the associations between the choices made in these three areas were explored. For instance, for all studies that applied quantitative analysis, the concept map characteristics considered were explored and listed. This showed that quantitative analysis was concerned with specific concept map characteristics, e.g. size, structural complexity, category representation, interlinkage or complexity index. Subsequently, the conclusions drawn were explored for each combination of methods of analysis and concept map characteristics considered. Based on the associations found across articles between the methods of analysis applied, the concept map characteristics considered and the conclusions drawn, considerations for methodological coherence between these aspects were formulated.

Twenty-five empirical studies from 1988 through 2018 used open-ended concept maps. Twenty-one of these studies consisted of multiple measurements, most commonly a pre-test/post-test design. Four of these studies compared two experimental groups, and two compared an experimental and control group. Two of the four studies that consisted of one measurement compared two experimental groups. In two studies, respondents received their previous concept map to adjust in the post-test, and in one study respondents could choose to adjust their previous map or to start a new one. Concept maps were either made on paper with pen, on sticky notes or on a computer, most commonly with the CMapTool, developed by the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. " Appendix A " provides the meta-matrix of these studies, including all selected information. For each aspect (method of analysis, concept map characteristics, and conclusions) the categorization or clustering based on the cross-case data analysis is presented in separate paragraphs. How concept map characteristics are associated with methods of analysis is described in the paragraph concerning the concept map characteristic. How conclusions drawn are related to concept map characteristics and methods of analysis is described at the end of the paragraph concerning conclusions drawn.

3.1 Methods of analysis

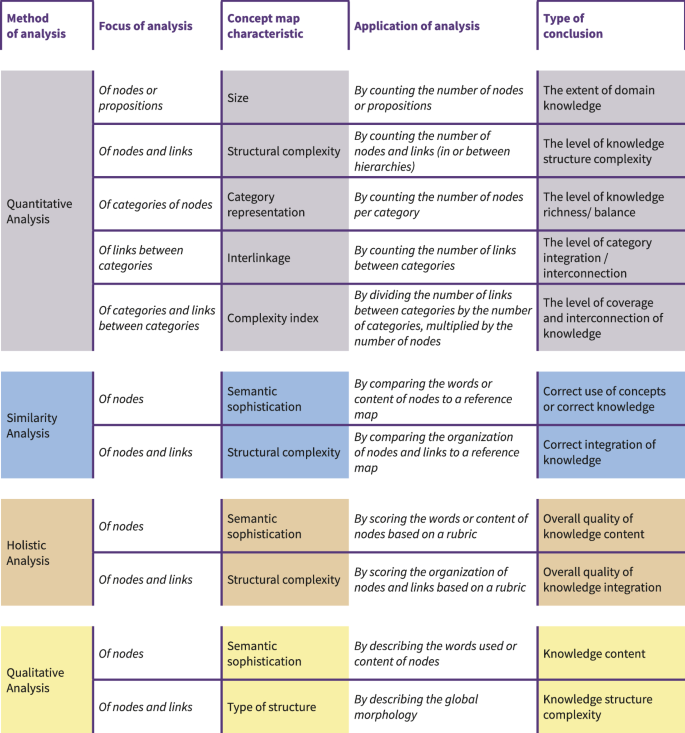

The different methods of analysis as described in the studies are extracted and presented in the table below. The explanation of these methods of analysis is provided after Table 2 .

Based on these studies it appears that the same term was sometimes used to refer to more than one analysis method, while in other cases, multiple terms were used to refer to a single method. These varieties increase the ambiguity experienced with concept map analysis, as described by Watson et al. ( 2016b ). Based on the ways in which concept map characteristics are estimated, we propose the following distinction: quantitative, similarity, holistic and qualitative analysis. Quantitative analysis, or counting concept map characteristics, was performed absolutely or relatively—for example, the number of links was counted separately or calculated in relation to the number of nodes. Category representation was also determined absolute, as the number of nodes belonging to a category, or relative, dividing the number of nodes belonging to a category by the total number of nodes in a map. These different calculations can result in different conclusions. According to Besterfield-Sacre and colleagues ( 2004 , p. 113), quantitative analysis “fails to capture the quality of that content. Further, these scoring methods can be time consuming, lack standards, and may introduce inappropriate bias.”

Similarity analysis described or calculated the percentage of overlap and/or discrepancy compared to a reference map. To calculate percentage of overlap, the terms used by respondents need to be aligned with the reference map. Similarity analysis provided insights into the (degree of) overlap and discrepancies with a reference map and was performed manually or in an automated manner (Ifenthaler et al. 2011 ).

Holistic analysis included scoring the structure or content for the concept map as a whole. Besterfield-Sacre and colleagues ( 2004 ) developed the scoring rubric that was commonly used for holistic analysis. They developed this rubric to score the overall comprehensiveness, organization and correctness of the map, based on the topics experts discussed while analyzing concept maps. Holistic analysis was determined on an inter-rater basis and is a cognitive complex task for which subject matter knowledge is necessary; this scoring is subjective (Borrego et al. 2009 ; Yaman and Ayas 2015 ).

Qualitative analysis of semantic content was performed in most studies, either inductively or deductively to determine categories. Qualitative analysis was the only way to explore concept maps content inductively.

Most studies applied more than one method of analysis. Quantitative analysis was applied in 19 studies, qualitative analysis also in 19 studies, holistic analysis in six studies and similarity analysis in five studies. Why methods of analysis were chosen is described in several studies. Ritchhart and colleagues ( 2009 , p. 152) stressed that qualitative analysis “allowed us to best represent all of the data from the maps”. Beyerbach ( 1988 , p.339) applied qualitative analysis, as it revealed “the nature of growth of student teachers’ thinking [..] and conceptual development”. Quantitative analysis was chosen as it “demonstrates the student learning gains” (Borrego et al. 2009 , p.14). Similarity analysis was performed as “Comparisons of the students' maps to an expert's map will provide information regarding how much is learned from the course and whether the concepts that are learned and included in the maps are done so "correctly" and as intended according to the expert-the faculty instructor” (Freeman and Urbaczewski 2002 , p. 42). Besterfield-Sacre et al. ( 2004 , p. 109) choose holistic scoring to explore students’ conceptual understanding, as an increase in understanding results “in higher quality maps as reflected by the holistic score.”

3.2 Concept map characteristics

This section describes what concept map characteristics were measured, how and why. Table 3 provides an overview of the results. The concept map characteristics described in this review concern characteristics as portrayed in the included studies. These include characteristics concerning the structure of concept maps, such as size, structural complexity and type of structure, and characteristics concerning the content of concept maps, for instance the terms used or categories represented in concept maps. The different concept map characteristics as portrayed in the included studies are presented below.

The number of nodes was referred to as the size or extent, and considered as “a simple indicator for the size of the underlying cognitive structure” (Ifenthaler et al. 2011 , p. 55). Size was established by counting the number of unique or correct nodes or propositions. Invalid nodes were included to study mental models or when misconceptions were important.

3.2.2 Structural complexity

Structural complexity is concerned with how complex the structure of a concept map is. The concept map nodes and links were used to study structural complexity quantitatively, holistically or in similarity. The scoring system for structural complexity from Novak and Gowin ( 1984 ), based on the number of hierarchies, cross-links and examples, was applied in seven studies, and these measures were adjusted in four of these studies. Specific aspects of structural complexity, were breadth or number of hierarchies and depth or hierarchy level (Beyerbach 1988 ; Read 2008 ). Other references to structural complexity, all calculated based on the number of links, are complexity, connectedness or dynamism and these measures are more commonly used for non-hierarchical concept maps (Ifenthaler et al. 2011 ; Tripto et al. 2018 ; Weiss et al. 2017 ). Freeman and Urbaczewski ( 2002 , p. 45) computed structural complexity as the number of relationships depicted in the map beyond the minimal amount necessary to connect all of the concepts linearly. Ifenthaler and colleagues ( 2011 ) included computations from graph theory, such as unlinked nodes that are not connected to the other nodes, the cyclic nature of a map, i.e. if all nodes can be reached easily, or the longest and/or shortest paths from the central node. Structural complexity was also scored based on a rubric, taking into account the overall organization of the map. For instance a score of 1 if the concept map is connected only linearly, a score of 2 when there are some connections between hierarchies, or a score of 3 for a sophisticated structure (Besterfield-Sacre et al. 2004 ). Another way to score structural complexity is by comparing structural characteristics with a reference map (Ifenthaler et al. 2011 ).

The analysis of structural complexity is more sensitive in measuring change than other analyses (West et al. 2000 ). However, the limited hierarchical interpretation of structural complexity based on quantitative analysis can lead to different scores than holistic scoring of structural complexity (Watson et al. 2016a ). According to West and colleagues ( 2000 , p. 821), scoring structural characteristics “[becomes] more difficult as maps grow more complex,” and Blackwell and Williams ( 2007 , p. 7) mentioned that scoring structural characteristics “can conceal the essentially subjective basis on which it rests.”

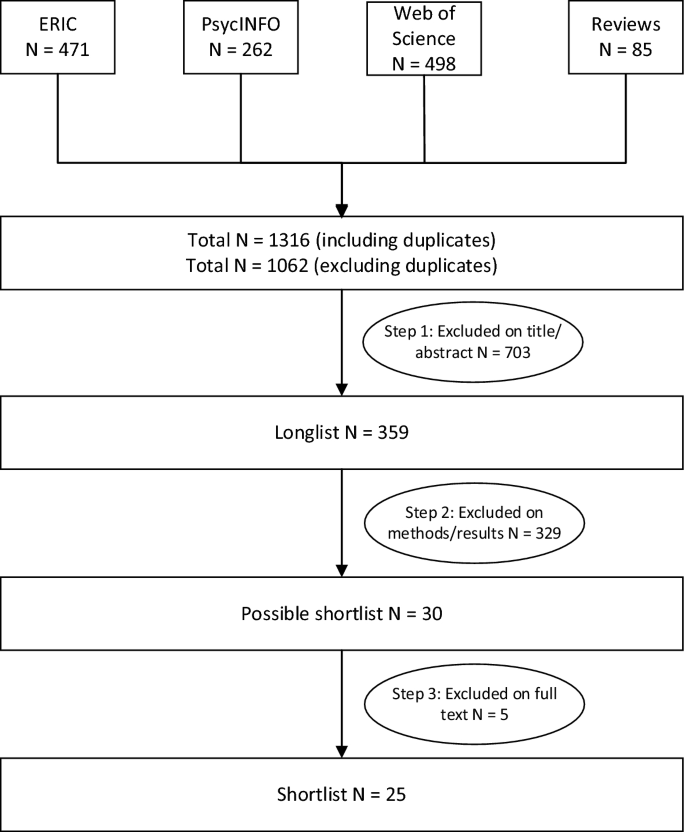

3.2.3 Type of structure

Studies concerned with the type of structure or shape of the map categorized concept maps qualitatively based on global morphologies. Global morphologies are common typical structures found in concept maps, such as chain, spoke or net structures, as depicted in Fig. 3 . This analysis provides a measure for the aptitude for learning and “avoids many pitfalls of quantitative analysis” (Hay et al. 2008 , p. 224). Yaman and Ayas ( 2015 , p. 853) categorized concept maps based on their type of structure, and stated that it was “very easy and informative.”

Global morphologies in concept maps (from Kinchin, Hay and Adams 2000 )

3.2.4 Semantic sophistication

Semantic sophistication is concerned with the terms as used by the respondents, for concepts as well as for links. Semantic sophistication was explored by describing or clustering the terms used by the respondents qualitatively. Analysis of the semantic sophistication or content revealed the information in concept maps and what respondents think (Kostromina et al. 2017 ; Ward and Haigh 2017 ): “These qualitative analyses go beyond traditional assessment techniques in providing the instructor with a much clearer view of what his/her students know, think, and understand” (Freeman and Urbaczewski 2002 , p. 51). Semantic sophistication was also scored based on a rubric, taking into account the comprehensiveness or correctness of content, and whether maps conformed to fact, logic or known truth (Besterfield-Sacre et al. 2004 ). Gregoriades and colleagues ( 2009 ) described how holistic scoring allowed them to assess overall understanding. The semantic sophistication was also measured in comparison to a reference map. Beyerbach ( 1988 , p. 341) calculated “convergence towards a group consensus, and convergence toward an expert's map to indicate conceptual growth.” Freeman and Urbaczewski ( 2002 , p. 42) compared students’ maps to an expert’s map to assess how much was learned and whether the learned concepts were integrated correctly.

3.2.5 Category representation

Category representation is concerned with categories of nodes and/or links in concept maps. Different types of categories were established, either valid and invalid nodes or propositions, where invalid nodes are outside of the scope of the prompt, and invalid propositions are incorrectly linked. Another category was old and new nodes in repeated measures, where old nodes were already present in the first map, and new nodes were added in the second map. Also content-related categories were distinguished, for instance concepts at different levels. One study distinguished different system levels, in order to reveal students’ systems thinking abilities—or, more specifically, students’ “ability to identify system components and processes at both micro and macro levels” (Tripto et al. 2018 , p. 649). Category representation can only be calculated quantitatively after categories are determined in maps qualitatively. Category representation was calculated by the number of nodes per category and was also referred to as knowledge richness, frequencies of themes, presence of systems, representational level or category distribution (Çakmak 2010 ; Kostromina et al. 2017 ; Ritchhart et al. 2009 ; Tripto et al. 2018 ; Yaman and Ayas 2015 ). Ritchhart and colleagues ( 2009 , p. 154) calculated the percent of responses in each category. Çakmak ( 2010 ) studied perceptions about roles based on the number of concepts assigned to each role.

3.2.6 Interlinkage

Interlinkage concerns the links between categories, and can only be calculated after categories are established. Interlinkage was also referred to as ‘complexity’ or ‘degree of interconnectedness.’ Interlinkage was interpreted as “students’ ability to identify relations between system components” (Tripto et al. 2018 , p. 649). Specifically, the interlinkage between old and new nodes was used to study learning, or how new knowledge is connected to existing knowledge (Hay et al. 2008 ). Güccük and Köksal ( 2016 ) explored meaningful learning based on the number of interlinks and interpreted more interlinks as more meaningful learning. Ward and Haigh ( 2017 , p. 1248) concluded that the analysis of interlinkage between old and new nodes allowed for holistic examination of the quality of learning.

3.2.7 Complexity index

The complexity index is calculated based on the number of concepts, number of categories, and number of links between categories. It was calculated in two studies to “characterize the overall coverage of and connectedness between the categories” (Watson et al. 2016b , p. 549). The complexity index is a particularization of interlinkage, calculated by dividing the number of interlinks by the number of categories, then multiplying this number with the number of nodes (Segalàs et al. 2012 , p. 296).

A variety of concept map characteristics was considered, leading to different insights. Size was measured in 18 studies. Structural complexity was also taken into account in 18 studies. Structural complexity considered nodes and links and seems relatively easy and objective to determine; however, it is more interpretative than it seems, especially as concept maps grow more complex. Type of structure was measured in three studies, and revealed the overall structure of the concept map, disregarding the content and allocating one score for the overall structure of the map. Although it is a time-consuming step to describe and interpret terms used by respondents, this is the only way to gain insights into the semantic content of the maps. The semantic sophistication was taken into account in 13 studies. Terms used were sorted into themes or categories, which was done in eleven studies, either inductively or deductively, based on a theoretical framework or scoring rubric, or in comparison with a reference map. Evaluating the terms used and categorizing or unifying them was a necessary preliminary step for calculating other concept map characteristics, namely: category representation, interlinkage and complexity index. These characteristics were only considered when meaningful categories were present and interconnection of these categories was convenient, for instance, in the case of systems thinking. Interlinkage was determined in five studies and the complexity index in two studies.

Explanation of the rationale for concept map characteristics and measures varied from just mentioning which characteristics are measured and how, to studies that explain their operationalization based on theoretical descriptions of the research object that is explicitly deduced into specific concept map characteristics and measures. Some studies explicitly explained the choice for concept map characteristics based on the conclusions to be drawn. For instance Besterfield-Sacre et al. ( 2004 , p.106) explain counting cross-links as follows: “We propose that measuring inter-relatedness is a way to assess the extent of knowledge integration.” How concept map characteristics were related to methods of analysis, is described in Table 3 .

3.3 Conclusions drawn in the studies

The different conclusions drawn in the included studies about knowledge or learning are presented below. Conclusions about knowledge, for instance knowledge extent, were based on the number of nodes (Gregoriades et al. 2009 ). In repeated measures, an increase in number of nodes was interpreted as “more detail” (Beyerbach 1988 , p. 345) or “greater domain knowledge” (Freeman and Urbaczewski 2002 , p. 45). Counting the nodes was performed to “quantify knowledge understanding” (Besterfield-Sacre et al. 2004 , p. 105). Conclusions about an “increase in richness” (Van den Boogaart et al. 2018 , p. 297) or “balanced understanding” (Watson et al. 2016b , p. 556) were based on counting the number of nodes per category. Conclusions about better coverage and interconnectedness or systemic thinking were based on the complexity index (Segalàs et al. 2012 ). Conclusions about what respondents knew, or in repeated measures about how their knowledge changed over time were based on describing the content of concept maps (Freeman and Urbaczewski 2002 , p. 42). It “revealed that teachers assign a significant role both to its own activity and activity of the University administration, as well as cooperation with students” (Kostromina et al. 2017 , p. 320).

Conclusions about the complexity of knowledge, or the complexity of the knowledge structure, were based on the number of links. For instance, a conclusion about “more complex constructions of their knowledge” was based on the number of links, or structural complexity of concept maps (Read 2008 , p. 127). In repeated measures, conclusions about “conceptual growth” were drawn based on structural complexity measures (Beyerbach 1988 , p. 342). Conclusions about knowledge integration and learning gains (Borrego et al. 2009 ) were based on scoring the structural quality of concept maps based on a rubric and, in repeated measures, about additional conceptual understanding (Besterfield-Sacre et al. 2004 ; Watson et al. 2016b ). Conclusions about the use of semantically correct concepts (Ifenthaler et al. 2011 ), or correct integration of concepts (Freeman and Urbaczewski 2002 ), were based on a comparison with a reference map. Other conclusions drawn based on comparison with a reference map were that students have significant misconceptions (Gregoriades et al. 2009 ), or that respondents gained a better understanding (Freeman and Urbaczewski 2002 ; Ifenthaler et al. 2011 ). Conclusions about meaningful learning were based on counting the number of links between old and new concepts (Hay 2007 ). Conclusions about development were also based on the type of structure of concept maps in repeated measures. Conclusions drawn based on the type of structure were in one study, that pre- and post-maps were both mainly non-hierarchical (Yaman and Ayas 2015 ), and in one study, that 16 of 18 respondents’ pre- and post-maps showed “remarkable structural homology, even where the content and its internal organisation were different” (Hay et al. 2008 , p. 233).

Most studies applied more than one method of analysis and combined concept map characteristics when conclusions were drawn. Two of the three studies applying one method of analysis, qualitatively described the terms used in maps. The other study that applied one method of analysis, explored the semantic sophistication and structural complexity holistically. All other studies analyzed at least one concept map characteristic with two methods of analysis (for instance combining quantitative and similarity analysis of structural complexity), but most commonly multiple concept map characteristics and multiple methods of analysis were applied. However, a conclusion concerning counting different concept map characteristics was that it has shown opposing results within several studies: “While cross link scores were lower in some cases, hierarchy scores increased dramatically demonstrating that students were seeing each proposition in greater depth” (Blackwell and Williams 2007 , p. 6). Or in the study of Freeman and Urbaczewski ( 2002 ), where structural complexity scores decreased while all other scores increased. In all studies, an increase in a measure or concept map characteristic was interpreted as conceptual development or growth, and in all but one repeated measures studies, development was found. This particular study described the main themes based on qualitative analysis of the terms used, without interpreting this as development. Two studies mentioned that the number of links or cross-links did not increase, and two studies found homogenous types of structures, but still concluded that understanding increased, mainly based on other measures.

Although most studies draw conclusions about conceptual understanding or in repeated measures about conceptual growth, conclusions drawn are related to the methods of analysis applied and concept map characteristics considered. Conclusions about an increase or growth, are mainly based on counting structural concept map characteristics, or applying quantitative analysis. Conclusions about meaningful learning and more balanced understanding, were also based on quantitative analysis. Conclusions about knowledge, learning or conceptual growth, or integration of knowledge were based on a comparison with a reference map. Conclusions concerning knowledge integration, learning and coverage were based on holistic analysis. Conclusions about the content of maps, and what respondent know or what themes they mention, were based on qualitative analysis of terms used.

4 Conclusion

The central research question was: Which methods of analysis are applied to open-ended concept maps when studying knowledge and learning, and how are these associated with concept map characteristics considered and conclusions drawn? The conclusions are presented based on the three main aspects of the research question, namely methods of analysis, concept map characteristics and conclusions drawn, as well as their mutual associations.

4.1 Methods of analysis

This review explored the methods of analysis applied in open-ended concept map studies and provided a first step towards exploring which methods of analysis are applied and how. Four categories of methods of analysis were identified, namely: (1) quantitative analysis based on counting concept map characteristics; (2) similarity analysis based on a comparison with a referent map; (3) holistic analysis that entails the scoring of maps as a whole based on a rubric; and (4) qualitative analysis that involves describing characteristics, for instance the terms used.

The 25 studies applied different methods of analysis. Due to the idiosyncratic nature of the data stemming from open-ended concept maps they can be analyzed in different ways (Novak 1990 ). Qualitative and quantitative analysis are most commonly applied to open concept maps, but to make concept maps more comparable, it is common to use both methods, in which case quantitative analysis is preceded by qualitative analysis. Quantitative analysis is performed to count differences between maps. Similarity analysis explores the overlap with a reference map based on the nodes or structural characteristics. Holistic analysis scores the structure and content of concept maps. Qualitative analysis is used to explore or describe concept map characteristics and to explore the uniqueness of each map.

Each method of analysis deals with the idiosyncratic data differently. Qualitative analysis of semantic sophistication is the only way to explore the idiosyncratic nature of open-ended concept maps and the terms for concepts as the respondents use them. Quantitative analysis reduces the unique terms respondents use to numbers. Similarity and holistic analyses value the terms used based on an existing framework and provide a score for overlap or correctness respectively. When an open-ended concept map is used to gather the unique terms respondents use and there is no correct map available, qualitative analysis is required to explore or describe this information or to make quantitative analysis more meaningful.

4.2 Concept map characteristics

Concept map characteristics are not always explicitly described, and many different descriptions are used for similar concept map characteristics. This study distinguished between seven concept map characteristics as described in the included articles. Concept map characteristics that were counted or evaluated quantitatively are size, structural complexity, category representation, interlinkage and complexity index. These are all related to structure, except for category representation, as this referred to the number of concepts per category. The type of structure, semantic sophistication, categories and interlinkage can be described or evaluated qualitatively. These are all related to the content of the map, except for type of structure. The structural complexity and semantic sophistication can also be evaluated in relation to a reference map based on a rubric. Similarity and holistic methods of analysis combine structural and content-related features of concept maps.

4.3 Conclusions drawn in the studies

Our review shows that although the methods of analysis vary, the conclusions drawn are quite similar. Despite whether concept map characteristics were counted, compared, scored or described, conclusions were drawn about understanding or conceptual growth in repeated measures. All studies with repeated measures applying quantitative analysis found an increase of a measure that was interpreted as conceptual growth. Similarity analysis in repeated measures revealed an increased overlap in specific measures, which was considered as development of understanding. Holistic analysis revealed that better understanding or knowledge integration was found in repeated measures. Three studies used qualitative analysis to identify conceptual growth, for instance, the concept of leadership, where students considered leadership more as a process in the post-test. Twenty of the 21 studies with repeated measures found some type of development or learning gains, most commonly referred to as conceptual growth.

4.4 Associations across articles

Associations were explored between the coding of the methods of analysis, the concept map characteristics, and the conclusions drawn, in order to provide guidelines for methodological coherence between these aspects. Figure 4 provides an overview of the types of conclusions that can be drawn from open-ended concept maps, in accordance with the identified methods of analysis and concept map characteristics.

Associations between methods of analysis, concept map characteristics and types of conclusions

Figure 4 can serve as a guide for future open-ended concept map studies which use the specific types of conclusions to be drawn as a means of deciding what method of analysis to apply and what concept map characteristics to consider. For instance, in cases of quantitative analysis, Fig. 4 suggests that no conclusions can be drawn about correctness or quality, only about the extent of domain knowledge, and an increase or decrease in repeated measures. In similarity analysis, correct and incorrect nodes and links are determined, based on a correct model. Therefore, conclusions can be drawn concerning correctness. When applying a rubric for holistic scoring, one overall score is often given for the entire map, in which the overall quality is scored (Besterfield-Sacre et al. 2004 ). Quality of content includes correctness, but only for the map as a whole. The concept map characteristics of size, category representation and semantic sophistication consider the nodes and lead to conclusions about knowledge. The concept map characteristics of structural complexity, interlinkage, complexity index and type of structure consider both the nodes and the links and lead to conclusions about knowledge structure or integration. By explicitly using the conclusion to be elicited as a basis for choosing methods of analysis and concept map characteristics, the transparency of research increases, which enables better quality assessment (Coombs 2017 ; Verhage and Boels 2017 ).

5 Discussion

When relating these conclusions to broader theory, the first point of discussion is that 20 out of 21 repeated measures studies identified learning or conceptual growth. This raises the question whether all development is interpreted as development, and whether an increase in nodes and links represents better understanding or not. Rikers, Schmidt and Boshuizen ( 2000 ), who studied encapsulated knowledge and expertise in diagnosing clinical cases, found that the proportion of encapsulating concepts increases as an indicator of expertise development. This entails a decrease in the number of nodes and links as expertise develops, as experts are able to differentiate between concepts and relationships that are more and less relevant according to a specific contexts. Accordingly, Mintzes and Quinn ( 2007 ) explore different phases in expertise development based on meaningful learning theory. Their distinction between phases of development is based on the number of expert concepts, which in turn are relevant superordinate concepts that are absent from novices’ concept maps. Accordingly, Schwendimann ( 2019 ), who studied the process of development of concept maps, also found differences between novices and experts mainly in the professional terminology experts use for their concepts and linking words. Therefore, the conclusion that an increase is always better is contradicted by many studies of expertise development in the field of cognitive science (Chi, Glaser and Farr 1988 ).

Our review did not aim to discuss the value of open-ended concept maps as an instrument to study knowledge or knowledge development. Nor did it aim to explore the validity of different methods of analysis, or determine which method of analysis is most valid, as these methods of analysis can be related to different research purposes or research objects (Kim and Clariana 2015 ). Quantitative analysis is based on an evaluative approach which assesses knowledge or growth based on specific measures or characteristics, such as size or complexity. Similarity and holistic methods analyze concept maps from expected structures or content and have an evaluative or prescriptive purpose. Similarity analysis and holistic analysis take a more normative approach to the analysis of open-ended concept maps, by comparing them to a reference map or scoring the map based on a rubric, respectively. On the other hand, qualitative analysis has a more explorative purpose. Merriam and Grenier ( 2019 ) explain similar purposes of qualitative research methods and point out that more open or qualitative analysis is suited to more explorative purposes, while more restricted approaches are more appropriate for evaluative purposes.

This review has several limitations. Only studies applying open-ended concept maps to study knowledge and learning were included. The results of this study could be different when reviewing studies that apply more closed concept maps, or studies that combine the application of concept maps with other research instruments. Also, the research objects are not included in Fig. 4 , as references to research objects were ambiguous in previous studies and it was unclear whether studies referred to the same objects differently, or studied different objects. As a result, this review focused on the process of analysis, disregarding what aspects of knowledge or learning were studied. Moreover, Fig. 4 provides no guidelines for alignment with other aspects of coherence in qualitative studies, for instance the philosophical positioning, the fundamental beliefs or theoretical perspective taken (Caelli et al. 2003 ; Davis 2012 ).

The findings in this review could be substantiated by further research exploring implicit choices or implicit methodological coherence that could not be extracted from the articles. This could take the form of interviews with the authors of the studies about their methodological assumptions, approaches and chosen methods of analysis. They could then be asked why and how they made choices related to their research object, the concept map characteristics they considered and the conclusions they drew.

While previous reviews by Ruiz-Primo and Shavelson ( 1996 ), Anohina and Grundspenkis ( 2009 ) and Strautmane ( 2012 ) explored aspects of the process of analysis separately, or related the method of analysis applied to the level of openness of the concept map task, this review examined three aspects of the analysis process in coherence. By doing so, the present study aims to inform the ongoing discussion in social sciences and beyond about the quality of analysis. Unfortunately, open-ended concept map studies often still feature ambiguous language use. This ambiguity decreases transparency about the method of analysis, the concept map characteristics, and, ultimately, the conclusions drawn and the methodological coherence of these aspects (Chenail et al. 2011 ; Seale 1999 ). Clarifying which approach is chosen to make sense of the information in open-ended concept maps provides a method of dealing with idiosyncratic information provided by the respondents and will support other researchers or policy makers to better interpret and value the conclusions drawn. By describing studies on the basis of the proposed distinction between methods of analysis applied and how they interpret or value information from concept maps, the constraints of each method can be discussed, and findings or conclusions can be understood with a degree of confidence (Chenail et al. 2011 ). This distinction between methods of analysis can enhance transparency about the conclusions to which a specific method of analysis can and cannot lead. Clarity about the choices within and across studies is stimulated by uniform referencing to these choices, which decreases the confusion caused by the variety of ways in which scholars refer to similar constructs. In future research, the guidelines provided in this study will assist scholars to make more informed choices for their analysis of idiosyncratic data gathered with open-ended concept maps.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are the papers as mentioned in the results and summarized in Appendix A. They are also indicated with an * in the references section of this review. The materials used to code this data are provided in the article. The condensed data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author Kirsten de Ries. The data are not publicly available due to the fact that not all these paper are Open Access.

Code availability

No computer codes or mathematical algorithm is used in this paper. The coding of our data was performed by the authors based on the coding scheme presented in the data section.

References indicated with * were included in the literature review

*Anohina, A., Grundspenkis, J.: Scoring concept maps: an overview. Comp. Sys. Tech. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1145/1731740.1731824

Article Google Scholar

Ayres, L., Kavanaugh, K., Knafl, K.A.: Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qual. Health Res. 13 , 871–883 (2003)

*Besterfield-Sacre, M., Gerchak, J., Lyons, M.R., Shuman, L.J., Wolfe, H.: Scoring concept maps: an integrated rubric for assessing engineering education. J. Eng. Educ. 93 , 105–115 (2004)

*Beyerbach, B.A.: Developing a technical vocabulary on teacher planning: preservice teachers’ concept maps. Teach. Teach. Educ. 4 , 339–347 (1988)

*Blackwell, C., Williams, J.: The utilization of concept maps in evaluating leadership comprehension. Proc. 2007 AAAE Res. Conf. 34, 698–707 (2007)

*Borrego, M., Newsmander, C., McNair, L.D., McGinnis, S.P.: Using concept maps to assess interdisciplinary integration of green engineering knowledge. Adv. Eng. Educ. 1 , 1–25 (2009)

Google Scholar

Bressington, D.T., Wells, H., Graham, M.: A concept mapping exploration of social workers’ and mental health nurses’ understanding of the role of the approved mental health professional. Nurse Educ. Today (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.034

Buhmann, S.Y., Kingsbury, M.: A standardized holistic framework for concept map analysis combining topological attributes and global morphologies. Knowl. Man. E-Learn. 7 , 20–35 (2015)

Caelli, K., Ray, L., Mill, J.: ‘Clear as Mud’: toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Meth. 2 (2), 1–16 (2003)

*Çakmak, M.: An examination of concept maps created by prospective teachers on teacher roles. Procd. Soc. Behv. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.354

Cañas, A.J., Novak, J.D., Reiska, P.: Cmapanalysis: an extensible concept map analysis tool. JETT 4 , 25–36 (2013)

Cetin, B., Güler, N., Sarica, R.: Using generalizability theory to examine different concept map scoring methods. EJER (2016). https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2016.66.12

Chenail, R.J., Duffy, M., St George, S., Wulff, D.: Facilitating coherence across qualitative research. TQR 16 , 263–275 (2011)

Chi, M., Glaser, R., Farr, M.: The nature of expertise. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, New Jersey (1988)

Coombs, C.: Coherence and transparency: some advice for qualitative researchers. Production (2017). https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.006817

Creswell, J.W.: Educational research: planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Preston, Boston (2012)