- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Social Mettle

Manuscript Speech: Definition, Examples, and Presentation Tips

A manuscript speech implies reading a pre-written speech word by word. Go through this SocialMettle write-up to find out its meaning, some examples, along with useful tips on how to present a manuscript speech.

Tip! While preparing the manuscript, consider who your audience is, so as to make it effectual.

Making a speech comes to us as a ‘task’ sometimes. Be it in school, for a meeting, or at a function; unless you are at ease with public speaking, speeches may not be everyone’s cup of tea. A flawless and well-structured delivery is always welcome though. Memories of delivering and listening to a variety of speeches are refreshed when confronted with preparing for one.

Being the most effective way of communication, a speech is also a powerful medium of addressing controversial issues in a peaceful manner. There are four types of speeches: impromptu, extemporaneous, manuscript, and memorized. Each has its purpose, style, and utility. We have definitely heard all of them, but may not be able to easily differentiate between them. Let’s understand what the manuscript type is actually like.

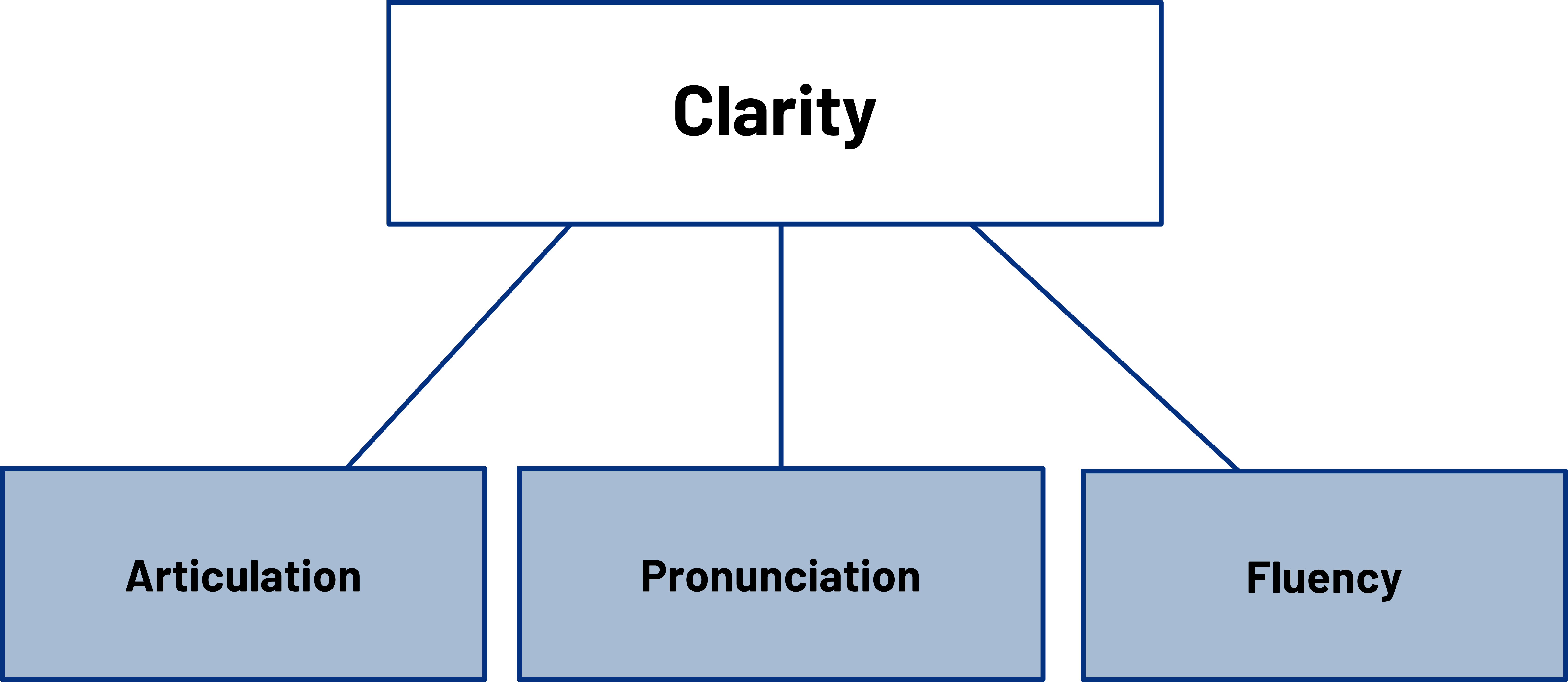

Definition of Manuscript Speech

This is when a speaker reads a pre-written speech word by word to an audience.

It is when an already prepared script is read verbatim. The speaker makes the entire speech by referring to the printed document, or as seen on the teleprompter. It is basically an easy method of oral communication.

Manuscript speaking is generally employed during official meetings, conferences, and in instances where the subject matter of the speech needs to be recorded. It is used especially when there is time constraint, and the content of the talk is of prime importance. Conveying precise and succinct messages is the inherent purpose of this speech. Public officials speaking at conferences, and their speech being telecast, is a pertinent example.

There can be various occasions where this style of speech is used. It depends on the context of the address, the purpose of communication, the target audience, and the intended impact of the speech. Even if it is understood to be a verbatim, manuscript speaking requires immense effort on the part of the speaker. Precision in the delivery comes not just with exact reading of the text, but with a complete understanding of the content, and the aim of the talk. We have witnessed this through many examples of eloquence, like the ones listed below.

- A speech given by a Congressman on a legislative bill under consideration.

- A report read out by a Chief Engineer at an Annual General Meeting.

- A President’s or Prime Minister’s address to the Parliament of a foreign nation.

- A televised news report (given using a teleprompter) seen on television.

- A speech given at a wedding by a best man, or during a funeral.

- A religious proclamation issued by any religious leader.

- A speech in honor of a well-known and revered person.

- Oral report of a given chapter in American history, presented as a high school assignment.

Advantages and Disadvantages

✔ Precision in the text or the speech helps catch the focus of the audience.

✔ It proves very effective when you have to put forth an important point in less time.

✔ Concise and accurate information is conveyed, especially when talking about contentious issues.

✘ If you are not clear in your speech and cannot read out well, it may not attract any attention of the audience.

✘ As compared to a direct speech, in a manuscript that is read, the natural flow of the speaker is lost. So is the relaxed, enthusiastic, interactive, and expressive tone of the speech lost.

✘ A manuscript speech can become boring if read out plainly, without any effort of non-verbal communication with the audience.

Tips for an Appealing Manuscript Speech

❶ Use a light pastel paper in place of white paper to lessen the glare from lights.

❷ Make sure that the printed or written speech is in a bigger font size than normal, so that you can comfortably see what you are reading, which would naturally keep you calm.

❸ Mark the pauses in your speech with a slash, and highlight the important points.

❹ You can even increase the spacing between words for easier reading (by double or triple spacing the text).

❺ Highlight in bold the first word of a new section or first sentence of a paragraph to help you find the correct line faster.

❻ Don’t try to memorize the text, highlights, or the pauses. Let it come in the flow of things.

❼ Practice reading it out aloud several times, or as many times as you can.

❽ Try keeping a smile on your face while reading.

❾ Keep in mind that a manuscript speech does not mean ‘mere reading out’. Maintaining frequent eye contact with the audience helps involving them into the subject matter.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

Persuasive Speech Outline, with Examples

March 17, 2021 - Gini Beqiri

A persuasive speech is a speech that is given with the intention of convincing the audience to believe or do something. This could be virtually anything – voting, organ donation, recycling, and so on.

A successful persuasive speech effectively convinces the audience to your point of view, providing you come across as trustworthy and knowledgeable about the topic you’re discussing.

So, how do you start convincing a group of strangers to share your opinion? And how do you connect with them enough to earn their trust?

Topics for your persuasive speech

We’ve made a list of persuasive speech topics you could use next time you’re asked to give one. The topics are thought-provoking and things which many people have an opinion on.

When using any of our persuasive speech ideas, make sure you have a solid knowledge about the topic you’re speaking about – and make sure you discuss counter arguments too.

Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- All school children should wear a uniform

- Facebook is making people more socially anxious

- It should be illegal to drive over the age of 80

- Lying isn’t always wrong

- The case for organ donation

Read our full list of 75 persuasive speech topics and ideas .

Preparation: Consider your audience

As with any speech, preparation is crucial. Before you put pen to paper, think about what you want to achieve with your speech. This will help organise your thoughts as you realistically can only cover 2-4 main points before your audience get bored .

It’s also useful to think about who your audience are at this point. If they are unlikely to know much about your topic then you’ll need to factor in context of your topic when planning the structure and length of your speech. You should also consider their:

- Cultural or religious backgrounds

- Shared concerns, attitudes and problems

- Shared interests, beliefs and hopes

- Baseline attitude – are they hostile, neutral, or open to change?

The factors above will all determine the approach you take to writing your speech. For example, if your topic is about childhood obesity, you could begin with a story about your own children or a shared concern every parent has. This would suit an audience who are more likely to be parents than young professionals who have only just left college.

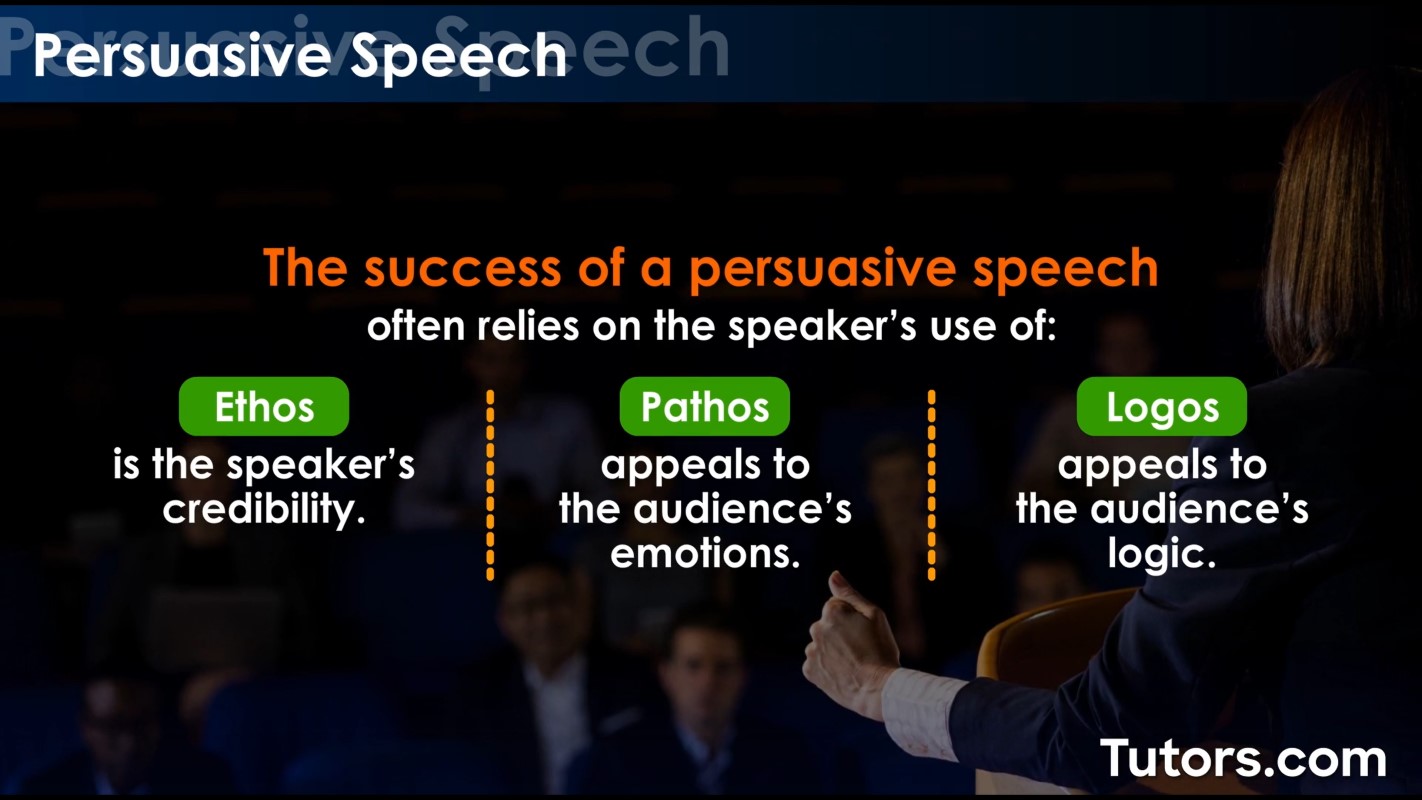

Remember the 3 main approaches to persuade others

There are three main approaches used to persuade others:

The ethos approach appeals to the audience’s ethics and morals, such as what is the ‘right thing’ to do for humanity, saving the environment, etc.

Pathos persuasion is when you appeal to the audience’s emotions, such as when you tell a story that makes them the main character in a difficult situation.

The logos approach to giving a persuasive speech is when you appeal to the audience’s logic – ie. your speech is essentially more driven by facts and logic. The benefit of this technique is that your point of view becomes virtually indisputable because you make the audience feel that only your view is the logical one.

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos: 3 Pillars of Public Speaking and Persuasion

Ideas for your persuasive speech outline

1. structure of your persuasive speech.

The opening and closing of speech are the most important. Consider these carefully when thinking about your persuasive speech outline. A strong opening ensures you have the audience’s attention from the start and gives them a positive first impression of you.

You’ll want to start with a strong opening such as an attention grabbing statement, statistic of fact. These are usually dramatic or shocking, such as:

Sadly, in the next 18 minutes when I do our chat, four Americans that are alive will be dead from the food that they eat – Jamie Oliver

Another good way of starting a persuasive speech is to include your audience in the picture you’re trying to paint. By making them part of the story, you’re embedding an emotional connection between them and your speech.

You could do this in a more toned-down way by talking about something you know that your audience has in common with you. It’s also helpful at this point to include your credentials in a persuasive speech to gain your audience’s trust.

Obama would spend hours with his team working on the opening and closing statements of his speech.

2. Stating your argument

You should pick between 2 and 4 themes to discuss during your speech so that you have enough time to explain your viewpoint and convince your audience to the same way of thinking.

It’s important that each of your points transitions seamlessly into the next one so that your speech has a logical flow. Work on your connecting sentences between each of your themes so that your speech is easy to listen to.

Your argument should be backed up by objective research and not purely your subjective opinion. Use examples, analogies, and stories so that the audience can relate more easily to your topic, and therefore are more likely to be persuaded to your point of view.

3. Addressing counter-arguments

Any balanced theory or thought addresses and disputes counter-arguments made against it. By addressing these, you’ll strengthen your persuasive speech by refuting your audience’s objections and you’ll show that you are knowledgeable to other thoughts on the topic.

When describing an opposing point of view, don’t explain it in a bias way – explain it in the same way someone who holds that view would describe it. That way, you won’t irritate members of your audience who disagree with you and you’ll show that you’ve reached your point of view through reasoned judgement. Simply identify any counter-argument and pose explanations against them.

- Complete Guide to Debating

4. Closing your speech

Your closing line of your speech is your last chance to convince your audience about what you’re saying. It’s also most likely to be the sentence they remember most about your entire speech so make sure it’s a good one!

The most effective persuasive speeches end with a call to action . For example, if you’ve been speaking about organ donation, your call to action might be asking the audience to register as donors.

Practice answering AI questions on your speech and get feedback on your performance .

If audience members ask you questions, make sure you listen carefully and respectfully to the full question. Don’t interject in the middle of a question or become defensive.

You should show that you have carefully considered their viewpoint and refute it in an objective way (if you have opposing opinions). Ensure you remain patient, friendly and polite at all times.

Example 1: Persuasive speech outline

This example is from the Kentucky Community and Technical College.

Specific purpose

To persuade my audience to start walking in order to improve their health.

Central idea

Regular walking can improve both your mental and physical health.

Introduction

Let’s be honest, we lead an easy life: automatic dishwashers, riding lawnmowers, T.V. remote controls, automatic garage door openers, power screwdrivers, bread machines, electric pencil sharpeners, etc., etc. etc. We live in a time-saving, energy-saving, convenient society. It’s a wonderful life. Or is it?

Continue reading

Example 2: Persuasive speech

Tips for delivering your persuasive speech

- Practice, practice, and practice some more . Record yourself speaking and listen for any nervous habits you have such as a nervous laugh, excessive use of filler words, or speaking too quickly.

- Show confident body language . Stand with your legs hip width apart with your shoulders centrally aligned. Ground your feet to the floor and place your hands beside your body so that hand gestures come freely. Your audience won’t be convinced about your argument if you don’t sound confident in it. Find out more about confident body language here .

- Don’t memorise your speech word-for-word or read off a script. If you memorise your persuasive speech, you’ll sound less authentic and panic if you lose your place. Similarly, if you read off a script you won’t sound genuine and you won’t be able to connect with the audience by making eye contact . In turn, you’ll come across as less trustworthy and knowledgeable. You could simply remember your key points instead, or learn your opening and closing sentences.

- Remember to use facial expressions when storytelling – they make you more relatable. By sharing a personal story you’ll more likely be speaking your truth which will help you build a connection with the audience too. Facial expressions help bring your story to life and transport the audience into your situation.

- Keep your speech as concise as possible . When practicing the delivery, see if you can edit it to have the same meaning but in a more succinct way. This will keep the audience engaged.

The best persuasive speech ideas are those that spark a level of controversy. However, a public speech is not the time to express an opinion that is considered outside the norm. If in doubt, play it safe and stick to topics that divide opinions about 50-50.

Bear in mind who your audience are and plan your persuasive speech outline accordingly, with researched evidence to support your argument. It’s important to consider counter-arguments to show that you are knowledgeable about the topic as a whole and not bias towards your own line of thought.

- Speech Crafting →

How to Write an Effective Manuscript Speech in 5 Steps

If your public speaking course requires you to give a manuscript speech, you might be feeling a little overwhelmed. How do you put together a speech that’s effective and engaging? Not to worry – with a few simple steps, you’ll be prepared to pull off a manuscript speech that’s both impactful and polished. In this post, we’ll walk through the 5 steps you need to follow to craft an effective manuscript speech that’ll leave your audience impressed. So let’s get started!

Quick Overview of Key Question

A manuscript speech involves writing down your entire speech word-for-word and memorizing it before delivering it. To begin, start by writing down your introduction , main points, and conclusion. Once you have written your speech, practice reading it out loud to get used to the phrasing and memorize each part .

Preparing a Manuscript Speech

When preparing for your manuscript speech, it is essential to consider both the content of your speech and the format in which you will deliver the speech. It is important to identify any key points or topics that you would like to cover in order to ensure that your manuscript is properly organized and succinct. Additionally, when selecting the style of delivery, be sure to choose one that best fits with your specific message and goals . One style of delivery includes utilizing a conversational tone in order to engage with your audience and help foster an interactive environment . When using this delivery style, be sure to use clear and concise language as well as humor and anecdotes throughout your speech . In addition, select a pacing that allows for flexibility with audience responses without detracting from the overall structure or flow of your text. Alternatively, another style of delivery involves reading directly from the manuscript without deviating from the text. This method works best when coupled with visual aids or props that support the information being relayed. Additionally, it is important to remember to practice reading the manuscript aloud several times prior to its delivery in order to ensure quality content and an acceptable rate of speed. No matter which delivery style you decide upon, careful preparation and rehearsal are essential components of delivering an effective manuscript speech. After deciding on a style of delivery and organizing the content of your speech accordingly, you can move on to formatting your document correctly in order to ensure a professional presentation during its delivery.

Document Format and Outline Structure

Before you dive into the content research and development stages of crafting your manuscript speech, it is important to consider the structure that your specific delivery will take. The format of your document can be varied depending on preferences and requirements, but always remember to keep it consistent throughout. When formatting your document, choose a universal style such as APA or MLA that may be easily recognisable to readers and familiar to most academics. Not only should this ensure your work meets some basic standards, but it will also make sure any information sources are appropriately cited for future reference. Additionally, you should provide visibility for headings to break up topics when needed, whilst keeping the language succinct and easy to understand. Creating an outline is integral in effectively structuring both a written piece of work and delivering a speech from paper. Use a hierarchical system of divisional points starting with a central concept, followed by additional details divided into sub sections where necessary and ending with a conclusion. This overview will act as a roadmap during the writing process—keeping track of ideas, identifying gaps in the presentation structure, and helping ensure clarity when presenting your points live on stage. It may be best practice to include a few statements or questions at the end of each key point to challenge thought in your audience and keep them engaged in the conversation. This could prompt new ideas or encourage defined discussion or debate amongst viewers. Depending on the topic itself, introducing two sides of an argument can allow an all-encompassing view point from which all members of an audience can draw their conclusions from majority opinion. Once you’ve established a full document format and outlined its corresponding structure for delivery, you’re ready for the next step: carefully developing comprehensive content along with appropriate ideas behind each sentence, word choice , and syntax used in every phrase. With these vital pieces in place, you are one step closer to creating an effective manuscript speech!

Content, Ideas and Language

The content, ideas, and language you use in your manuscript speech should be tailored to the audience you are addressing. It is important to consider the scope of the audience’s knowledge, level of interest in the topic and any special needs or cultural sensitivities. The most obvious way of doing this is by understanding who will be listening to the speech. You can also research the subject matter thoroughly to ensure you have a well-rounded perspective on the issue and that your opinion is well-informed.

While incorporating facts and personal experiences can help make any point stronger, ensure all ideas included in the speech have a relevancy to the main argument. Finally, avoid using difficult words or jargons as they may detract from any points being made. In terms of language, it’s recommended to use an active voice and write plainly while maintaining interesting visuals. This will help keep listeners engaged and make it easy for them to understand what’s being said. Additionally, focus on using appropriate vocabulary that will sound classy and create a good impression on your audience. Use simpler terms instead of long-winded ones, as regularly as possible, so that your message integrates easier with listeners. Now that you’ve considered content ideas and language for your manuscript speech, it’s time to go forward with writing and practicing it.

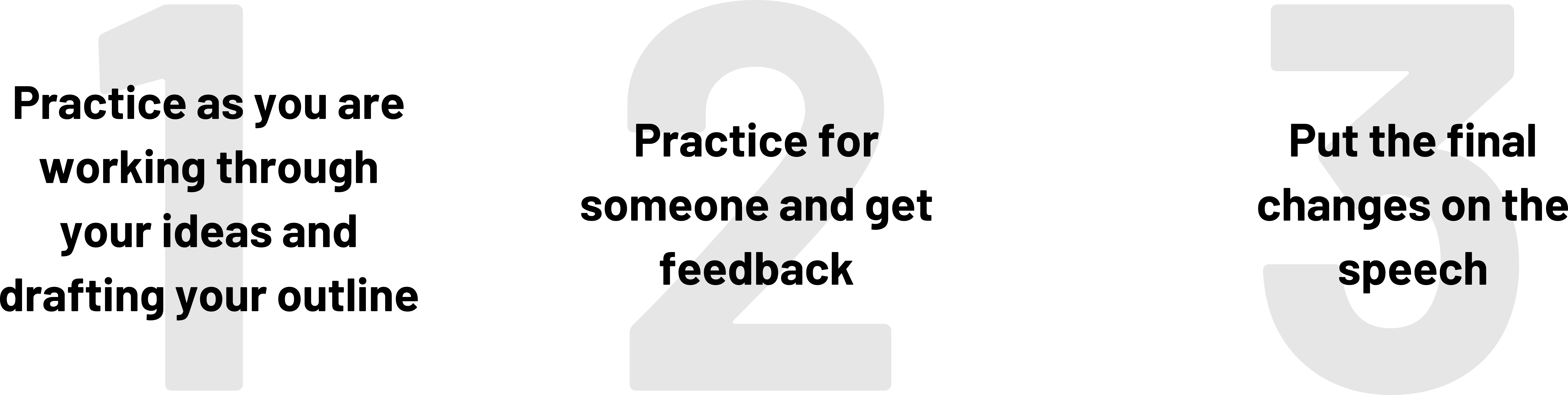

Writing and Practicing a Manuscript Speech

When writing a manuscript speech, it’s important to choose a central topic and clearly define the message you want to convey. Start by doing some research to ensure that your facts are accurate and up-to-date. Take notes and begin to organize your points into a logical flow. Once the first draft of your speech is complete, read it over multiple times, checking for grammar and typos. Also consider ways to effectively utilize visuals, such as photos or diagrams, as props within your speech if they will add value to your content. It is essential to practice delivering your speech using the manuscript long before you stand in front of an audience. Time yourself during practice sessions so that you can get comfortable staying within the parameters provided for the speech. Achieving a perfect blend of speaking out loud and reading word-by-word from the script is a vague area that speakers must strike a balance between in order to engage their audience without appearing overly rehearsed or overly off-the-cuff. Finally, look for opportunities to get feedback on your manuscript speech as you progress through writing and practicing it. Ask family members or friends who are familiar with public speaking for their input, or join an organization like Toastmasters International – an organization dedicated to improving public speaking skills – for more constructive criticism from experienced professionals. Crafting a powerful story should be the next step in preparing for an effective manuscript speech. Rather than delivering cold data points, use storytelling techniques to illustrate your point: Describe how others felt when faced with a challenge, what strategies they used to overcome it, and how their lives changed as a result. Telling stories makes data memorable, entertaining and inspiring – all qualities which should be considered when writing an engaging manuscript speech.

Crafting a Powerful Story

A powerful story is one of the most important elements of a successful manuscript speech. It is the main ingredient to make your speech memorable to the audience and help it stand out from all the other speeches. When crafting a story, there are a few things you should consider: 1) Choose an Appropriate Topic: The topic of your story should be appropriate for the type of speech you will be giving. If you are giving a motivational speech , for example, ensure your story has an uplifting message or theme that listeners can take away from it. Additionally, avoid topics that are too controversial so as not to offend any members of the audience. 2) Relay Your Experience: You could also use your own experience to create powerful stories in your manuscript speech. This gives listeners an authentic perspective of the topic and makes them feel connected to you and your message. Besides personal experiences, you may also draw stories from current events and movies/books which listeners can relate to depending on their age group. 3) Be Animated: As you deliver your story, be sure to convey emotions with proper tone and gestures in order to keep the audience engaged and increase its resonance. Using props and visual aids can also complement the delivery of your story by making it more experiential for listeners. Finally, before moving on to writing the rest of the manuscript speech, ensure that you have developed a powerful story that captures the hearts of those who hear it. With a great story to start off with, listeners will become more invested in what is about to come next in this speech – some tips for delivery!

Key Points to Remember

Writing a powerful story is essential to creating a successful manuscript speech. When selecting topics and stories, it’s important to consider the type of speech, the message, and making sure it’s appropriate and isn’t offensive. Drawing from personal experience and current events can enhance the audience’s connection with the topic, while being animated with tone and gestures will make it more engaging. Visual aids and props can complement this as well. Introducing a great story will draw people to your speech and help them get invested in what comes next.

Tips for Delivery of a Manuscript Speech

Delivering a manuscript speech effectively is essential for making sure your message gets across to your audience. While it may seem daunting, by following a few simple tips, you can ensure that you present your speech in the most professional manner possible. Before you start delivering your speech, be sure to practice it several times in advance. This will help you become comfortable with your words so that they don’t come out stilted while presenting. It is also important to emphasize vocal variety by changing the tone and intensity of your voice to keep the audience’s focus; boring monotone voices are often difficult to listen to. Remember to slow down or speed up depending on the importance of what you’re saying; never read word-for-word from your script – instead, aim for an engaging, conversational delivery. When delivering a manuscript speech, hand gestures can prove particularly useful for emphasizing key points. You can use arm movements and body language to convey the emotions behind your words without them feeling forced or unnatural. Again, practice helps here as well; make yourself aware of your posture and make subtle adjustments throughout until you feel comfortable speaking while moving around confidently on stage. Eye contact is another key element of effective presentation . Make sure to look into the eyes of every member of your audience at least once during your presentation – this will help them feel like they are interacting with you directly and make them more receptive to your ideas. Feel free to break away from traditional powerpoint slides if they aren’t necessary – take advantage of the natural lighting in the room and navigate through the visible space instead. Finally, remember that how you conclude the speech is just as important as how you began it, so aim for a powerful ending that leaves those listening with a lasting impression of what was discussed and learned throughout your presentation. With these tips for delivery in mind, you’re almost ready to leave a lasting impression on your audience – something we’ll discuss further in the next section!

Making a Lasting Impression with Your Audience

When you first create your manuscript speech, it is of utmost importance to consider your audience. Each part of the speech must be tailored to the people who will be listening. If a speaker can connect with an audience and make an emotional impact, the work that went into crafting the document will pay off. Using a conversational tone, humor, storytelling, and analogies can help keep the audience engaged during your speech. These techniques give the listener something to connect with and remember after the presentation is over. However, be sure to balance any humorous anecdotes or stories with a professional demeanor as not to lose credibility with your audience. Considering each part of the message and its potential impression on the listeners can also help guide you in tailoring a manuscript speech. When introducing yourself, try to use language that connects with the background of your peers; focus on wanting to help others with what you have learned or experienced so they feel like you are truly talking directly to them. Conclude by summing up important points in an inspirational way and leave listeners motivated and determined to apply the advice given in their own lives. Through this manner of “closing out” an effective speech, the audience can carry away meaningful information that will stay with them long after you finish speaking. Now that you understand how essential it is for speakers to make a lasting impression on their audiences, let us move onto learning how to confidently handle questions from your listeners as part of your presentation.

How to Handle Questions from Your Audience

When writing a manuscript speech, there are certain things you should consider when handling questions from your audience. This is an essential part of giving a successful talk to a group of people. The best way to handle questions is to take notes and make sure you can answer them directly after the speech is completed. It is important to be prepared with responses to any potential questions that may arise during your presentation. This will show your audience that you have taken the time and effort towards understanding their concerns and addressing them accordingly.

Additionally, it is also beneficial to anticipate possible areas of criticism or disagreement among members of your audience, as this allows you to provide evidence or offer an alternate route for them to consider when questioning the points made in your presentation. It is also important to remain courteous and professional when answering questions , even if someone challenges your views or speaks unkindly about your topic. It is always best practice to remain composed and ensure everyone in the room feels respected. Furthermore, having an open discussion with your audience following a well-prepared manuscript speech can add value by expanding on topics outlined. It also presents an opportunity for further clarifications and understanding beyond just getting out the message. This can be done by asking the participants what they thought of the presentation, what points they found most interesting, and other general feedback they might offer. If handled correctly, these moments can be used as learning opportunities for both yourself and others. Ultimately, handling questions from your audience confidently and gracefully is an important component of delivering a successful manuscript speech. By taking the time to prepare a response tailored towards each inquiry, even if it involves debate, you show respect towards those who took their time out of their day to attend your talk.

Additionally, it presents an opportunity to expand on topics covered while allowing meaningful dialogue between participants. With that said, it’s now time turn our focus onto crafting an effective conclusion for our manuscripts speeches – one which can bring our ideas full circle and leave our audience with memorable words!

Conclusion and Overall Manuscript Speech Strategy

The conclusion of any speech is an important part of the process and should not be taken lightly. Regardless of the structure or content of the speech, the conclusion can help drive home the points you have made throughout your speech. It also serves to leave a lasting impression on the listener. The conclusion should not be too long or drawn-out, but it should be meaningful and relevant to your topic and overall message. When writing your conclusion, consider recapping some of the key points made in the body of your speech. This will help to reinforce those ideas that you want to stick with the listener most. Additionally, make sure to emphasize how what has been addressed in your speech translates into real-world solutions or recommendations. This can help ensure that you have conveyed an actionable and tangible impact with your speech. One way to approach crafting an effective manuscript for a speech is to take note of the overall theme or objective that you wish to convey. From there, think about how best to organize your information into manageable sections, ensuring that each one accurately reflects your main points from both a visual and verbal standpoint. Consider what visuals or other tools could be used to further illustrate or clarify any complex concepts brought up in the main body of your speech. Finally, be sure to craft an appropriate conclusion that brings together all of these points into a cohesive whole, leaving your listeners with powerful words that underscore the importance and significance of what you have said. Overall, successful manuscript speeches depend on clear and deliberate preparation. Spending time outlining, writing, and editing your speech will ensure that you are able to effectively communicate its message within a set timeframe and leave a lasting impact on those who heard it. By following this process carefully, you can craft manuscripts that will inform and inspire audiences while driving home key talking points effectively every time.

Frequently Asked Questions and Their Answers

What are the benefits of giving a manuscript speech.

Giving a manuscript speech has many benefits. First, it allows the speaker to deliver a well-researched and thought-out message that is generally consistent each time. Since the speaker has prepared their speech in advance, they can use rehearsals to perfect their delivery and make sure their message is clear and concise.

Additionally, having a manuscript allows the speaker the freedom to focus on engaging the audience instead of trying to remember what to say next. Having a written script also helps remove the fear of forgetting important points or getting sidetracked on tangents during the presentation. Finally, with a manuscript, it’s possible to easily modify content from performance to performance as needed. This can help ensure that every version of the speech remains as relevant, meaningful, and effective as possible for each audience.

How does one prepare a manuscript speech?

Preparing a manuscript speech requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are the five steps to help you write a successful manuscript speech: 1. Research: Take the time to do your research and gather all the facts you need. This should be done well in advance so that you can prepare your speech carefully. 2. Outline: Lay out an outline of the major points you want to make in your speech and make sure each point builds logically on the one preceding it. 3. Draft: Once you have an outline, begin to flesh it out into a first draft of your manuscript speech. Be sure to include transitions between key points as well as fleshing out any examples or anecdotes that may help illustrate your points. 4. Edit: Once you have a first draft, edit it down multiple times. This isn’t where detailed editing comes in; this is more about making sure all the big picture elements work logically together, ensuring smooth transitions between ideas, and ensuring your words are chosen precisely to best convey their meaning. 5. Practice: The last step is perhaps the most important – practice! Rehearse your manuscript speech until you know it like the back of your hand, so that when it’s time for delivery, you can be confident of success.

What are some tips for delivering a successful manuscript speech?

1. Prepare in advance: Draft a script and practice it several times before delivering it. This will allow you to be comfortable with your material and avoid any awkward pauses when you are presenting your speech. 2. Speak clearly: Make sure that you speak loudly and clearly enough for everyone in the room to hear you. It is also important to enunciate your words properly so that your message can easily be understood by your audience. 3. Engage with the audience: Use eye contact when addressing your audience, ask questions and wait for responses, and pause to allow people time to mull over your points. These techniques help to ensure that everyone is engaged and interested in what you are saying. 4. Create visual aids: Create slides or other visuals that augment the material in your manuscript speech. This can help to keep the audience focused on what they are hearing as well as providing a reference point for them after your speech is finished. 5. Rehearse: Rehearse the delivery of your manuscript speech at least once prior to giving it so that you feel confident about how it will sound when presented in front of an audience. Identify any areas where improvements may be needed and focus on perfecting them before delivering the speech.

My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

How to Write an Outline for a Persuasive Speech, with Examples

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

Persuasive speeches are one of the three most used speeches in our daily lives. Persuasive speech is used when presenters decide to convince their presentation or ideas to their listeners. A compelling speech aims to persuade the listener to believe in a particular point of view. One of the most iconic examples is Martin Luther King’s ‘I had a dream’ speech on the 28th of August 1963.

In this article:

What is Persuasive Speech?

Here are some steps to follow:, persuasive speech outline, final thoughts.

Persuasive speech is a written and delivered essay to convince people of the speaker’s viewpoint or ideas. Persuasive speaking is the type of speaking people engage in the most. This type of speech has a broad spectrum, from arguing about politics to talking about what to have for dinner. Persuasive speaking is highly connected to the audience, as in a sense, the speaker has to meet the audience halfway.

Persuasive Speech Preparation

Persuasive speech preparation doesn’t have to be difficult, as long as you select your topic wisely and prepare thoroughly.

1. Select a Topic and Angle

Come up with a controversial topic that will spark a heated debate, regardless of your position. This could be about anything. Choose a topic that you are passionate about. Select a particular angle to focus on to ensure that your topic isn’t too broad. Research the topic thoroughly, focussing on key facts, arguments for and against your angle, and background.

2. Define Your Persuasive Goal

Once you have chosen your topic, it’s time to decide what your goal is to persuade the audience. Are you trying to persuade them in favor of a certain position or issue? Are you hoping that they change their behavior or an opinion due to your speech? Do you want them to decide to purchase something or donate money to a cause? Knowing your goal will help you make wise decisions about approaching writing and presenting your speech.

3. Analyze the Audience

Understanding your audience’s perspective is critical anytime that you are writing a speech. This is even more important when it comes to a persuasive speech because not only are you wanting to get the audience to listen to you, but you are also hoping for them to take a particular action in response to your speech. First, consider who is in the audience. Consider how the audience members are likely to perceive the topic you are speaking on to better relate to them on the subject. Grasp the obstacles audience members face or have regarding the topic so you can build appropriate persuasive arguments to overcome these obstacles.

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

4. Build an Effective Persuasive Argument

Once you have a clear goal, you are knowledgeable about the topic and, have insights regarding your audience, you will be ready to build an effective persuasive argument to deliver in the form of a persuasive speech.

Start by deciding what persuasive techniques are likely to help you persuade your audience. Would an emotional and psychological appeal to your audience help persuade them? Is there a good way to sway the audience with logic and reason? Is it possible that a bandwagon appeal might be effective?

5. Outline Your Speech

Once you know which persuasive strategies are most likely to be effective, your next step is to create a keyword outline to organize your main points and structure your persuasive speech for maximum impact on the audience.

Start strong, letting your audience know what your topic is, why it matters and, what you hope to achieve at the end of your speech. List your main points, thoroughly covering each point, being sure to build the argument for your position and overcome opposing perspectives. Conclude your speech by appealing to your audience to act in a way that will prove that you persuaded them successfully. Motivation is a big part of persuasion.

6. Deliver a Winning Speech

Select appropriate visual aids to share with your audiences, such as graphs, photos, or illustrations. Practice until you can deliver your speech confidently. Maintain eye contact, project your voice and, avoid using filler words or any form of vocal interference. Let your passion for the subject shine through. Your enthusiasm may be what sways the audience.

Topic: What topic are you trying to persuade your audience on?

Specific Purpose:

Central idea:

- Attention grabber – This is potentially the most crucial line. If the audience doesn’t like the opening line, they might be less inclined to listen to the rest of your speech.

- Thesis – This statement is used to inform the audience of the speaker’s mindset and try to get the audience to see the issue their way.

- Qualifications – Tell the audience why you are qualified to speak about the topic to persuade them.

After the introductory portion of the speech is over, the speaker starts presenting reasons to the audience to provide support for the statement. After each reason, the speaker will list examples to provide a factual argument to sway listeners’ opinions.

- Example 1 – Support for the reason given above.

- Example 2 – Support for the reason given above.

The most important part of a persuasive speech is the conclusion, second to the introduction and thesis statement. This is where the speaker must sum up and tie all of their arguments into an organized and solid point.

- Summary: Briefly remind the listeners why they should agree with your position.

- Memorable ending/ Audience challenge: End your speech with a powerful closing thought or recommend a course of action.

- Thank the audience for listening.

Persuasive Speech Outline Examples

Topic: Walking frequently can improve both your mental and physical health.

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to start walking to improve their health.

Central idea: Regular walking can improve your mental and physical health.

Life has become all about convenience and ease lately. We have dishwashers, so we don’t have to wash dishes by hand with electric scooters, so we don’t have to paddle while riding. I mean, isn’t it ridiculous?

Today’s luxuries have been welcomed by the masses. They have also been accused of turning us into passive, lethargic sloths. As a reformed sloth, I know how easy it can be to slip into the convenience of things and not want to move off the couch. I want to persuade you to start walking.

Americans lead a passive lifestyle at the expense of their own health.

- This means that we spend approximately 40% of our leisure time in front of the TV.

- Ironically, it is also reported that Americans don’t like many of the shows that they watch.

- Today’s studies indicate that people were experiencing higher bouts of depression than in the 18th and 19th centuries, when work and life were considered problematic.

- The article reports that 12.6% of Americans suffer from anxiety, and 9.5% suffer from severe depression.

- Present the opposition’s claim and refute an argument.

- Nutritionist Phyllis Hall stated that we tend to eat foods high in fat, which produces high levels of cholesterol in our blood, which leads to plaque build-up in our arteries.

- While modifying our diet can help us decrease our risk for heart disease, studies have indicated that people who don’t exercise are at an even greater risk.

In closing, I urge you to start walking more. Walking is a simple, easy activity. Park further away from stores and walk. Walk instead of driving to your nearest convenience store. Take 20 minutes and enjoy a walk around your neighborhood. Hide the TV remote, move off the couch and, walk. Do it for your heart.

Thank you for listening!

Topic: Less screen time can improve your sleep.

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to stop using their screens two hours before bed.

Central idea: Ceasing electronics before bed will help you achieve better sleep.

Who doesn’t love to sleep? I don’t think I have ever met anyone who doesn’t like getting a good night’s sleep. Sleep is essential for our bodies to rest and repair themselves.

I love sleeping and, there is no way that I would be able to miss out on a good night’s sleep.

As someone who has had trouble sleeping due to taking my phone into bed with me and laying in bed while entertaining myself on my phone till I fall asleep, I can say that it’s not the healthiest habit, and we should do whatever we can to change it.

- Our natural blue light source is the sun.

- Bluelight is designed to keep us awake.

- Bluelight makes our brain waves more active.

- We find it harder to sleep when our brain waves are more active.

- Having a good night’s rest will improve your mood.

- Being fully rested will increase your productivity.

Using electronics before bed will stimulate your brainwaves and make it more difficult for you to sleep. Bluelight tricks our brains into a false sense of daytime and, in turn, makes it more difficult for us to sleep. So, put down those screens if you love your sleep!

Thank the audience for listening

A persuasive speech is used to convince the audience of the speaker standing on a certain subject. To have a successful persuasive speech, doing the proper planning and executing your speech with confidence will help persuade the audience of your standing on the topic you chose. Persuasive speeches are used every day in the world around us, from planning what’s for dinner to arguing about politics. It is one of the most widely used forms of speech and, with proper planning and execution, you can sway any audience.

How to Write the Most Informative Essay

How to Craft a Masterful Outline of Speech

Leave a Comment

I accept the Privacy Policy

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities

Vivamus integer non suscipit taciti mus etiam at primis tempor sagittis euismod libero facilisi.

© 2024 My Speech Class

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

36 Speaking from a Manuscript: How to Read Without Looking Like You Are Reading

How to Write and Use Manuscripts

There will be times when reading from a manuscript is helpful. When giving a eulogy and you are likely to experience strong emotions, having your words written out and in front of you will be very helpful. Politicians often speak from manuscripts because there will be people weighing the meaning of each word. They often have speech writers who take their ideas and make them sound professional, and they likely have several people look it over for any offensive words or questionable phrases.

The advantage to speaking with a manuscript is you have your speech in front of you. This gives you an opportunity to plan interesting wordplays and to use advanced language techniques. By managing the exact wording, you can better control the emotional tone. Another advantage to using a manuscript is you can share your speech with others both for proofing and for reference. For example, many people like to have written copies of the toast given to them at a special occasion or a copy of the eulogy to the loved one. Politically speaking, a manuscript can be helpful to help keep you on track and to help you say only the things that you mean to say.

The disadvantage to a manuscript is if not done properly, your speech may feel like an “essay with legs.” Speaking from a manuscript is a skill; I would argue that it is one of the most difficult of all types because your goal is to read without appearing to read. It can be so tempting to lock eyes on the page where it is safe and then never look up at the audience. Finally, it is very difficult for most people to gesture when reading a manuscript. Many people run their hands down the page to keep their place while others clutch the podium and never let go. These disadvantages can be overcome with practice. You can be dynamic and engaging while using a manuscript, but it does take work.

Keys to Using a Manuscript

- Always write a manuscript in manuscript format and never in essay format. (It should look like poetry).

- Practice your speech at a podium so you can figure out how to change pages smoothly.

- Learn the art of eye fixations.

- Practice with a friend so you can master eye contact.

- If you struggle with gestures, make a note on your manuscript to remind you to gesture.

- Practice, practice, practice–you should actually practice more than in a typical speech since it is a harder delivery method.

Formatting a Manuscript

- Do not start a sentence on one page and then finish it on another.

- Do not fold the manuscript–it won’t lay flat on the podium.

- Do not print on both sides of the page.

- Do not staple the manuscript

- Number your pages.

- Use a large font and then make it one size larger than you think you need.

- It should look like poetry.

- Have extra spaces between every main idea.

- Bold the first word of every main section.

- Use /// or …. to indicate pauses in your speech.

- Emphasize a word with a larger font or by making it bold.

- If you have a parallel construction where you repeat the same word, bold or underline the repeated word.

- Use an easy-to-read font.

- Make a note (SLIDE) when you need to change your slide.

- It is OK to omit punctuation.

- Do whatever formatting works best for you.

Sample manuscripts

Notice how this student formats her manuscript by making it spread out and easy to read:

Today // it is an honor for me to stand here before you at the Freedom Banquet and pay tribute to a man

,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, that in his lifetime …………………………………. has touched ………………….. and changed …………………………… uncountable lives across the globe

Today /// we are here to honor ……………. a president, ……………………….. a father, ……………………………… a husband ……………………………………. and a true savior in Mr. Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

Tribute speech by Tanica van As delivered at the University of Arkansas

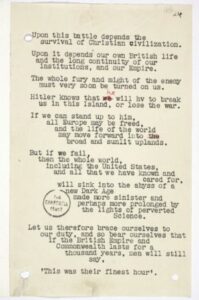

Manuscript From History

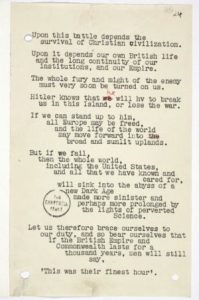

Winston Churchill’s Speech in Response to German’s Invasion of Britain and Finest Hour Speech

Sometimes referred to as the Psalms format or free verse format, the speech is written like it will be spoken.

How to Present with a Manuscript

To best read a manuscript, we need to borrow some items from speed reading. When you were first learning to read, you learned to read each letter–D–O–G. You would look at the letter “D,” then your eyes would look at the letter “O, ” and finally, your eyes would move over to look at the letter “G.” You would fixate (or rest) your eyes on three different places. Eventually, you got better at reading and better at seeing, so you would now look at “dog” in one eye fixation and your brain was able to take in the information–dog. Now, you no longer read one letter at a time, that would be way too slow. Now you look at all three letters and see it as a word.

Over time, you learned to see bigger words–like “communication” (13 letters). Now, consider this… the phase “The dog ran fast” contains 13 letters. Since you can see the word “communication” as one eye fixation and understand it as one thing, in theory, your eyes should be able to see “the dog ran fast” as one eye fixation and understand it too. We have been trained to look at each word individually with separate eye fixations. For example, …the … dog… ran… fast… is four different eye fixations. With a little practice, you can train your eyes to see the whole phrase with one look. Here are some sentences, practice looking at each of the sentences with one eye fixation.

I ate the red apple

My car is green

My cat is moody

You tried it didn’t you? You can only learn if you try them out. If you didn’t try it, go back and look at those sentences again and try to see the whole sentence with one look. With practice, you can look at an entire sentence as one thing (eye fixation). Your brain can understand all those words as one thought. Now, try this. Wherever you are right now, look up at the wall nearest you and then look back down. Write down all the things you can recall about what you saw–I saw a yellow wall with brown trim, two bookcases, a clock, a printer, a bird statue. Your brain is amazing; it can look up to a wall and in one eye fixation, it can take in all that it sees.

You can take in many sentences as well. You can actually see two sentences in one look. Try to look down at these next two sentences in one eye fixation. Test yourself by looking down and then looking up and saying what you remember out loud.

The boy sang a song

The girl danced along

With a little practice, most people can see chunks of five words across and three lines down. Give it a try. Once again, try to look at the three sentences as one and then look up and say them.

The happy frog leaped

off the lily pad

and into the cool water

It takes practice, but you can do it. The bonus feature of doing the practice and learning this skill is you will learn to read faster. Since a lot of college work and professional preparation relies on reading the information, it would benefit you for the rest of your life to learn this valuable skill. While researching, I came across this excellent slide presentation by Sanda Jameson on Reading for College that goes into more depth about the process. I highly recommend you review it to help you with your manuscript reading and to help you become a better reader in your college classes.

https://www.nwmissouri.edu/trio/pdf/sss/study/Reading-for-college.pdf

By now, you have figured out that using chunking and working on eye fixations is going to help you read your manuscript easier. Arranging your manuscript where you have only five to seven words on a line will make it easier to see as one fixation. Organizing your manuscript where you can see several lines of text at once, can help you put a lot of information in one eye fixation.

Now, let’s look at a eulogy written by one of my students, Sydney Stout. She wrote this eulogy to her grandpa who loved dancing and encouraged her to do the same. First, notice the manuscript format where it is written like it will be spoken. It is chunked into lines that are usually 5-7 words long. The list of names is written like a stair step showing the stair step in the voice when the names are spoken. Try reading this except out loud focusing on eye fixations. Try to see one whole line at a time and then read it again trying to see two lines at a time.

Dancing is a delicate art

An activity many people love and enjoy

but someone that loves dancing

more than anyone I know

is my grandfather.

You all know my grandfather

Maybe you know him as James

….. Jack

……… Dad

…………. Papa Jack

………………… or in my case………………. . just Papa.

Papa // you have led me through life

like any great dance partner should

And I’ve memorized the steps you’ve taught me

………………………………………. …. And they have allowed me to dance

……………………………………………………………… gracefully

………………………………………………………….. through my own life

Tribute speech by Sydney Stout delivered at the University of Arkansas

Watch this eulogy speech to Rosa Parks by Oprah Winfrey. Notice how each word is carefully chosen and how if you notice closely, you can tell that she is using a manuscript. Notice how seamlessly she turns the pages and notice how she spends most of her time looking up at the audience. Masterfully, she uses gestures to enhance the rhythmic flow o the speech and to draw the audience’s attention.

Timing Your Manuscript

Practice your manuscript at least 5 to 7 times. Trust me when I say, It is harder to speak with a manuscript than it is to give a speech with brief notes and it requires considerable more practice to get it right.

Use this chart as a general reference for the timing of your speech to the length of your manuscript.

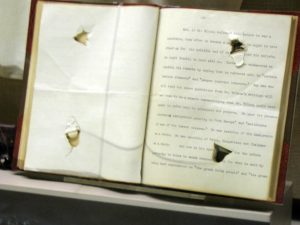

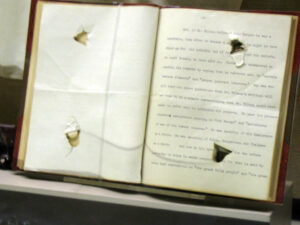

A Speech Saved the President’s Life

Teddy Roosevelt’s life was saved when an assassin’s bullet was slowed down by his 50 paged speech manuscript. The doctor on sight determined that although the bullet didn’t puncture his lungs, he should still go to the hospital immediately. A determined Roosevelt balked and said, “You get me to that speech.” He delivered a 50-minute speech before going to the hospital. Doctors decided it was safer to leave the bullet in his chest and declared that his speech had indeed saved his life.

More on this story from the history channel: https://www.history.com/news/shot-in-the-chest-100-years-ago-teddy-roosevelt-kept-on-talking

Please share your feedback, suggestions, corrections, and ideas.

I want to hear from you.

Do you have an activity to include? Did you notice a typo that I should correct? Are you planning to use this as a resource and do you want me to know about it? Do you want to tell me something that really helped you?

Click here to share your feedback.

Klein, C. (2019). When Teddy Roosevelt was shot in 1912, a speech may have saved his life. https://www.history.com/news/shot-in-the-chest-100-years-ago-teddy-roosevelt-kept-on-talking

Speech in minutes. (n.d.). http://www.speechinminutes.com/

Stout, S. (n.d.). Eulogy to Papa with the theme of dancing. Delivered in Lynn Meade’s Advanced Public Speaking Class at the University of Arkansas. Used with permission.

Van As, T. (n.d.) Tribute to Nelson Mandela. Delivered in Lynn Meade’s Advanced Public Speaking Class at the University of Arkansas. Used with permission.

Winfrey, O. (2010). Eulogy to Rosa Parks. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cfhtfNfIPE Standard YouTube License.

Media Attributions

- Winston Churchill’s Manuscript is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Winston Churchill’s Speech in Response to German’s Invasion of Britain

- Winston Churchill Finest Hour Speech

- Teddy’s speech © Janine Eden, Eden Pictures is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Advanced Public Speaking Copyright © 2021 by Lynn Meade is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Here is a generic, sample speech in an outline form with notes and suggestions.

Learning Objective

- Understand the structural parts of a persuasive speech.

Attention Statement

Show a picture of a person on death row and ask the audience: does an innocent man deserve to die?

Introduction

Briefly introduce the man in an Illinois prison and explain that he was released only days before his impending death because DNA evidence (not available when he was convicted), clearly established his innocence.

A statement of your topic and your specific stand on the topic:

“My speech today is about the death penalty, and I am against it.”

Introduce your credibility and the topic: “My research on this controversial topic has shown me that deterrence and retribution are central arguments for the death penalty, and today I will address each of these issues in turn.”

State your main points.

“Today I will address the two main arguments for the death penalty, deterrence and retribution, and examine how the governor of one state decided that since some cases were found to be faulty, all cases would be stayed until proven otherwise.”

Information: Provide a simple explanation of the death penalty in case there are people who do not know about it. Provide clear definitions of key terms.

Deterrence: Provide arguments by generalization, sign, and authority.

Retribution: Provide arguments by analogy, cause, and principle.

Case study: State of Illinois, Gov. George Ryan. Provide an argument by testimony and authority by quoting: “You have a system right now…that’s fraught with error and has innumerable opportunities for innocent people to be executed,” Dennis Culloton, spokesman for the Governor, told the Chicago Tribune . “He is determined not to make that mistake.”

Solution steps:

- National level . “Stay all executions until the problem that exists in Illinois, and perhaps the nation, is addressed.”

- Local level . “We need to encourage our own governor to examine the system we have for similar errors and opportunities for innocent people to be executed.”

- Personal level . “Vote, write your representatives, and help bring this issue to the forefront in your community.”

Reiterate your main points and provide synthesis; do not introduce new content.

Residual Message

Imagine that you have been assigned to give a persuasive presentation lasting five to seven minutes. Follow the guidelines in Table 14.6 “Sample Speech Guidelines” and apply them to your presentation.

Table 14.6 Sample Speech Guidelines

Key Takeaway

A speech to persuade presents an attention statement, an introduction, the body of the speech with main points and supporting information, a conclusion, and a residual message.

- Apply this framework to your persuasive speech.

- Prepare a three- to five-minute presentation to persuade and present it to the class.

- Review an effective presentation to persuade and present it to the class.

- Review an ineffective presentation to persuade and present it to the class

Business Communication for Success: Public Speaking Edition Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Delivering a Speech

Introduction

9.1 Managing Public Speaking Anxiety

Sources of speaking anxiety.

Aside from the self-reported data in national surveys that rank the fear of public speaking high for Americans, decades of research conducted by communication scholars shows that communication apprehension is common among college students (Priem & Solomon, 2009). Communication apprehension (CA) is fear or anxiety experienced by a person due to real or perceived communication with another person or persons. CA is a more general term that includes multiple forms of communication, not just public speaking. Seventy percent of college students experience some CA, which means that addressing communication anxiety in a class like the one you are taking now stands to benefit the majority of students (Priem & Solomon, 2009). Think about the jitters you get before a first date, a job interview, or the first day of school. The novelty or uncertainty of some situations is a common trigger for communication anxiety, and public speaking is a situation that is novel and uncertain for many.

Public speaking anxiety is a type of CA that produces physiological, cognitive, and behavioral reactions in people when faced with a real or imagined presentation (Bodie, 2010). Physiological responses to public speaking anxiety include increased heart rate, flushing of the skin or face, and sweaty palms, among other things. These reactions are the result of natural chemical processes in the human body. The fight or flight instinct helped early humans survive threatening situations. When faced with a ferocious saber-toothed tiger, for example, the body released adrenaline, cortisol, and other hormones that increased heart rate and blood pressure to get more energy to the brain, organs, and muscles in order to respond to the threat. We can be thankful for this evolutionary advantage, but our physiology has not caught up with our new ways of life. Our body does not distinguish between the causes of stressful situations, so facing down an audience releases the same hormones as facing down a wild beast.

Cognitive reactions to public speaking anxiety often include intrusive thoughts that can increase anxiety: “People are judging me,” “I’m not going to do well,” and “I’m going to forget what to say.” These thoughts are reactions to the physiological changes in the body but also bring in the social/public aspect of public speaking in which speakers fear being negatively judged or evaluated because of their anxiety. The physiological and cognitive responses to anxiety lead to behavioral changes. All these thoughts may lead someone to stop their speech and return to their seat or leave the classroom. Anticipating these reactions can also lead to avoidance behavior where people intentionally avoid situations where they will have to speak in public.

Addressing Public Speaking Anxiety

While we cannot stop the innate physiological reactions related to anxiety from occurring, we do have some control over how we cognitively process them and the behaviors that result. Research on public speaking anxiety has focused on three key ways to address this common issue: systematic desensitization, cognitive restructuring, and skills training (Bodie,2010).

Although systematic desensitization may sound like something done to you while strapped down in the basement of a scary hospital, it actually refers to the fact that we become less anxious about something when we are exposed to it more often (Bodie, 2010). As was mentioned earlier, the novelty and uncertainty of public speaking is a source for many people’s anxiety. So becoming more familiar with public speaking by speaking more often can logically reduce the novelty and uncertainty of it.

Systematic desensitization can result from imagined or real exposure to anxiety-inducing scenarios. In some cases, an instructor leads a person through a series of relaxation techniques. Once relaxed, the person is asked to imagine a series of scenarios including speech preparation and speech delivery. This is something you could also try to do on your own before giving a speech. Imagine yourself going through the process of preparing and practicing a speech, then delivering the speech, then returning to your seat, which concludes the scenario. Aside from this imagined exposure to speaking situations, taking a communication course like this one is a great way to engage directly in systematic desensitization. Almost all students report that they have less speaking anxiety at the end of a semester than when they started, which is at least partially due to the fact they engaged with speaking more than they would have done if they were not taking the class.

Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive restructuring entails changing the way we think about something. A first step in restructuring how we deal with public speaking anxiety is to cognitively process through our fears to realize that many of the thoughts associated with public speaking anxiety are irrational (Allen, Hunter & Donohue, 2009). For example, people report a fear of public speaking over a fear of snakes, heights, financial ruin, or even death. It’s irrational to think that the consequences of giving a speech in public are more dire than getting bit by a rattlesnake, falling off a building, or dying. People also fear being embarrassed because they mess up. Well, you cannot literally die from embarrassment, and in reality, audiences are very forgiving and overlook or do not even notice many errors that we, as speakers, may dwell on. Once we realize that the potential negative consequences of giving a speech are not as dire as we think they are, we can move on to other cognitive restructuring strategies.

Communication-orientation modification therapy (COM therapy) is a type of cognitive restructuring that encourages people to think of public speaking as a conversation rather than a performance (Motley, 2009). Many people have a performance-based view of public speaking. This can easily be seen in the language that some students use to discuss public speaking. They say that they “rehearse” their speech, deal with “stage fright,” then “perform” their speech on a “stage.” There is no stage at the front of the classroom; it is a normal floor. To get away from a performance orientation, we can reword the previous statements to say that they “practice” their speech, deal with “public speaking anxiety,” then “deliver” their speech from the front of the room. Viewing public speaking as a conversation also helps with confidence. After all, you obviously have some conversation skills, or you would not have made it to college. We engage in conversations every day. We do not have to write everything we are going to say out on a note card, we do not usually get nervous or anxious in regular conversations, and we are usually successful when we try. Even though we do not engage in public speaking as much, we speak to others in public all the time. Thinking of public speaking as a type of conversation helps you realize that you already have accumulated experiences and skills that you can draw from, so you are not starting from scratch.

Last, positive visualization is another way to engage in cognitive restructuring. Speaking anxiety often leads people to view public speaking negatively. They are more likely to judge a speech they gave negatively, even if it was good. They are also likely to set up negative self-fulfilling prophecies that will hinder their performance in future speeches. To use positive visualization, it is best to engage first in some relaxation exercises such as deep breathing or stretching, and then play through vivid images in your mind of giving a successful speech. Do this a few times before giving the actual speech. Students sometimes question the power of positive visualization, thinking that it sounds corny. Ask an Olympic diver what his or her coach says to do before jumping off the diving board and the answer will probably be “Coach says to image completing a perfect 10 dive.” Likewise a Marine sharpshooter would likely say his commanding officer says to imagine hitting the target before pulling the trigger. In both instances, positive visualization is being used in high-stakes situations. If it is good enough for Olympic athletes and snipers, it is good enough for public speakers.

Skills training is a strategy for managing public speaking anxiety that focuses on learning skills that will improve specific speaking behaviors. These skills may relate to any part of the speech-making process, including topic selection, research and organization, delivery, and self-evaluation. Skills training, like systematic desensitization, makes the public speaking process more familiar for a speaker, which lessens uncertainty. In addition, targeting specific areas and then improving on them builds more confidence, which can in turn lead to more improvement. Feedback is important to initiate and maintain this positive cycle of improvement. You can use the constructive criticism that you get from your instructor and peers in this class to target specific areas of improvement.

Self-evaluation is also an important part of skills training. Make sure to evaluate yourself within the context of your assignment or job and the expectations for the speech. Do not get sidetracked by a small delivery error if the expectations for content far outweigh the expectations for delivery. Combine your self-evaluation with the feedback from your instructor, boss, and/or peers to set specific and measurable goals and then assess whether or not you meet them in subsequent speeches. Once you achieve a goal, mark it off your list and use it as a confidence booster. If you do not achieve a goal, figure out why and adjust your strategies to try to meet it in the future.

Physical Relaxation Exercises

Suggestions for managing speaking anxiety typically address its cognitive and behavioral components, while the physical components are left unattended. While we cannot block these natural and instinctual responses, we can engage in physical relaxation exercises to counteract the general physical signs of anxiety caused by cortisol and adrenaline release, which include increased heart rate, trembling, flushing, high blood pressure, and speech disfluency.

Some breathing and stretching exercises release endorphins, which are your body’s natural antidote to stress hormones. Deep breathing is a proven way to release endorphins. It also provides a general sense of relaxation and can be done discretely, even while waiting to speak. In order to get the benefits of deep breathing, you must breathe into your diaphragm. The diaphragm is the muscle below your lungs that helps you breathe and stand up straight, which makes it a good muscle for a speaker to exercise. To start, breathe in slowly through your nose, filling the bottom parts of your lungs up with air. While doing this, your belly should pooch out. Hold the breath for three to five full seconds and then let it out slowly through your mouth. After doing this only a few times, many students report that they can actually feel a flooding of endorphins, which creates a brief “light-headed” feeling. Once you practice and are comfortable with the technique, you can do this before you start your speech, and no one sitting around you will even notice. You might also want to try this technique during other stressful situations. Deep breathing before dealing with an angry customer or loved one, or before taking a test, can help you relax and focus.

Stretching is another way to release endorphins. Very old exercise traditions like yoga, tai chi, and Pilates teach the idea that stretching is a key component of having a healthy mind and spirit. Exercise in general is a good stress reliever, but many of us do not have the time or willpower to do it. However, we can take time to do some stretching. Obviously, it would be distracting for the surrounding audience if a speaker broke into some planking or Pilates just before his or her speech. Simple and discrete stretches can help get the body’s energy moving around, which can make a speaker feel more balanced and relaxed. Our blood and our energy/ stress have a tendency to pool in our legs, especially when we are sitting.

Vocal Warm-Up Exercises

Vocal warm-up exercises are a good way to warm up your face and mouth muscles, which can help prevent some of the fluency issues that occur when speaking. Newscasters, singers, and other professional speakers use vocal warm-ups. I lead my students in vocal exercises before speeches, which also helps lighten the mood. We all stand in a circle and look at each other while we go through our warm-up list. For the first warm-up, we all make a motorboat sound, which makes everybody laugh. The full list of warm-ups follows and contains specific words and exercises designed to warm up different muscles and different aspects of your voice. After going through just a few, you should be able to feel the blood circulating in your face muscles more. It is a surprisingly good workout!

Top Ten Ways to Reduce Speaking Anxiety

Many factors contribute to speaking anxiety. There are also many ways to address it. The following is a list of the top ten ways to reduce speaking anxiety that I developed with my colleagues, which helps review what we have learned.

- Remember, you are not alone. Public speaking anxiety is common, so do not ignore it—confront it.

- Remember, you cannot literally “die of embarrassment.” Audiences are forgiving and understanding.

- Remember, it always feels worse than it looks.

- Take deep breaths. It releases endorphins, which naturally fight the adrenaline that causes anxiety.

- Look the part. Dress professionally to enhance confidence.

- Channel your nervousness into positive energy and motivation.

- Start your outline and research early. Better information = higher confidence.

- Practice and get feedback from a trusted source. (Do not just practice for your cat.)

- Visualize success through positive thinking.

- Prepare, prepare, prepare! Practice is a speaker’s best friend.

9.2 Delivery Methods and Practice Sessions

There are many decisions to make during the speech-making process. Making informed decisions about delivery can help boost your confidence and manage speaking anxiety. In this section, we will learn about the strengths and weaknesses of various delivery methods. We will also learn how to make the most of your practice sessions.

Delivery Methods

Different speaking occasions call for different delivery methods. While it may be acceptable to speak from memory in some situations, lengthy notes may be required in others. The four most common delivery methods are impromptu, manuscript, memorized, and extemporaneous.

Impromptu Delivery