Health Care Reform

- First Online: 26 February 2022

Cite this chapter

- Jonathan Oberlander 5

1051 Accesses

1 Altmetric

This chapter analyzes the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) turbulent political journey and the current state of health care reform in the United States, with particular focus on developments in health politics and policy during the Obama and Trump administrations. Reforming American health care is perennially a politically treacherous task due to a combination of interest group pressures, fragmented political institutions, and a prominent anti-government strain in US political ideology. The adoption of piecemeal, incremental reforms during the twentieth century makes it difficult to enact more comprehensive solutions to the formidable problems in American health care today. Recent developments in US health politics show that it is possible to move past the inertia of the status quo—but progress is both fragile and limited. The sustained battles over the ACA’s implementation and repeal are shaped by growing ideological and political divisions between Democrats and Republicans, and partisan polarization has altered the normal political trajectory that follows the enactment of a major new social policy program like the ACA. The chapter explains why the ACA proved much more politically vulnerable than initially anticipated, but also resilient despite sustained efforts to roll it back. The chapter also considers the impact of Covid-19 and how the (dis)organization of American health care and health policy has complicated the challenge of responding to the pandemic in the United States.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Banthin, J., and J. Holahan. 2020. Making Sense of Competing Estimates: The Covid-19 Recession’s Effect on Health Coverage . Available from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102777/making-sense-of-competing-estimates_1.pdf .

Béland, D., P. Rocco, and A. Waddan. 2016. Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics, and the Affordable Care Act . Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Google Scholar

Brown, L.D. 2011. The Elements of Surprise: How Health Reform Happened. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 36 (3): 419–427.

Article Google Scholar

Hacker, J.S., and P. Pierson. 2018. The Dog That Almost Barked: What the ACA Repeal Fight Says About the Resilience of the American Welfare State. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 43 (4): 551–577.

Jost, T.S., and K. Keith. 2020. ACA Litigation: Politics Pursued Through Other Means. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 45 (4): 485–499.

Levitt, L. 2020. The Affordable Care Act’s Enduring Resilience. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 45 (4): 609–616.

McCarty, N. 2019. Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know . New York: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Morone, J.A. 1992. Bias of American Politics: Rationing Health Care in a Weak State. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 140: 1923–1938.

Nather, D., and L. Gamio. 2017. The Most Unpopular Bill in Three Decades. Available from: https://www.axios.com/unpopular-health-care-bill-2454397857.html .

Oberlander, J. 2003. The Politics of Health Reform: Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good Health Plans? Health Affairs 22 (Suppl.), W3: 391–404.

———. 2010. Long Time Coming: Why Health Reform Finally Passed. Health Affairs 9 (6): 1112–1116.

———. 2016. Implementing the ACA: The Promise and Limits of Health Care Reform. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 41 (4): 803–826.

———. 2017. Replace, Repeal, Repair, Retreat—Republicans’ Health Care Quagmire. New England Journal of Medicine 377 (11): 1001–1003.

———. 2019. Lessons from the Long and Winding Road to Medicare for All. American Journal of Public Health 109 (11): 1497–1500.

———. 2020. The Ten Years’ War: Politics, Partisanship, and the ACA. Health Affairs 39 (3): 471–478.

Peterson, M.A. 2005. The Congressional Graveyard for Health Care Reform. In Healthy, Wealthy and Fair: Health Care for a Good Society , ed. L.D. Brown, L.R. Jacobs, and J.A. Morone, 205–234. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Schwartz, K., K. Pollitz, J. Tolbert, and M. Musumeci. 2020. Gaps in Cost Sharing Protections for Covid-19 Testing and Treatment Could Spark Public Concerns about Covid-19 Vaccine Costs . Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/gaps-in-cost-sharing-protections-for-covid-19-testing-and-treatment-could-spark-public-concerns-about-covid-19-vaccine-costs/ . Accessed 11 Apr 2021.

Starr, P. 2011. Remedy and Reaction: The Peculiar American Struggle Over Health Care Reform . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Steinmo, S., and J. Watts. 1995. It’s the Institutions, Stupid! Why Comprehensive National Health Insurance Always Fails in America. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 20 (2): 329–372.

Tolbert, J., K. Orgera, and A. Damico. 2020. Key Facts About the Uninsured Population . Available from: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/ . Accessed 8 Apr 2021.

White, J. 2013. The 2010 U.S. Health Care Reform: Approaching and Avoiding How Other Countries Finance Health Care. Health Economics, Policy and Law 8 (3): 289–315.

Further Reading

The involvement of presidents from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Barack Obama in health care reform is vividly explored in David Blumenthal and James Morone’s (2009) The Heart of Power (Berkeley: University of California Press). Other excellent accounts of the history and politics of US health policy during the twentieth century include Paul Starr’s (2nd edition, 2017) The Social Transformation of American Medicine (New York: Basic Books), Theodore Marmor’s (2nd edition, 2000) The Politics of Medicare (London: Routledge), and Jacob Hacker’s (1996) The Road to Nowhere (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

There is a large and growing literature on the politics of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). John McDonough’s (2011) Inside National Health Reform (Berkeley: University of California Press) and Paul Starr’s (2011) Remedy and Reaction (2011) (New Haven: Yale University Press) explore the remarkable constellation of political forces and choices that led to the law’s enactment as well as the promise and limits of the ACA’s design. The post-enactment conflicts over the ACA at the state level and in the context of federalism are skillfully analyzed by Daniel Béland, Philip Rocco, and Alex Waddan’s (2016) Obamacare Wars and David Jones’ (2017) Exchange Politics (New York: Oxford University Press). Jamila Michener’s excellent (2018) Fragmented Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) goes beyond the ACA to show how federalism reproduces inequalities in state Medicaid programs and how enrollment in such programs impact political participation by low-income beneficiaries.

Recent scholarship in American health politics has also examined the formidable barriers to controlling health care costs. Miriam Laugesen’s (2016) Fixing Medical Prices (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) and Eric Patashnik, Alan Gerber, and Conor Dowling’s (2017) Unhealthy Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press) are exceptional accounts of the political forces that shape US health care spending. Beyond the scholarly literature, the Kaiser Family Foundation ( https://www.kff.org/ ) and Commonwealth Fund ( https://www.commonwealthfund.org/ ) are essential sources of news, data, and analysis of current issues in U.S. health care policy.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Policy and Management, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Jonathan Oberlander

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jonathan Oberlander .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Gillian Peele

Department of Political Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Bruce E. Cain

School of Social, Political and Global Studies, Keele University, Staffordshire, UK

Jon Herbert

School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, UK

Andrew Wroe

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Oberlander, J. (2022). Health Care Reform. In: Peele, G., Cain, B.E., Herbert, J., Wroe, A. (eds) Developments in American Politics 9. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89740-6_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89740-6_15

Published : 26 February 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-89739-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-89740-6

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Cover Archive

- Research from China

- Highly Cited Collection

- Review Series Index

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The Association of Physicians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The american health care system, american perceptions of other health care systems, comparisons of health care systems, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Health care reforms in America: perspectives, comparisons and realities *

*Based on a Lecture given at the John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford on 6 October 2009.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

R.J. Glassock, Health care reforms in America: perspectives, comparisons and realities , QJM: An International Journal of Medicine , Volume 103, Issue 9, September 2010, Pages 709–714, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcq072

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Health care reforms are now a reality in America after a long and tortuous debate. President Obama has achieved a 'victory' unlike anything seen since the term of President Lyndon Johnson, over 40 years ago. The new law brings America closer to universal coverage and access to affordable health care for its citizens, but the cost of the program and its impact on individuals, physicians, hospitals, the pharmaceutical and device industry and insurance companies is not yet fully known. The debate preceding the enactment of health care reform brought up numerous comparisons (often invidious and falsified) between the American system of health care and other systems throughout the world, including the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and Medicare in Canada. This overview examines the issues raised in the debate, perceptions of health care systems on a global basis, provides some perspectives on the reform of health care systems and examines some of the realities underlying these changes for the future of health care in America.

The great generational debate on how to reform the health care system in America came to a dramatic conclusion late in the evening of 21 March 2010 when the House of Representatives approved (by a vote of 219 to 212) a previously approved Senate version of health reform legislation. 1 Two days later, President Obama signed the landmark legislation into law and became the first President since Lyndon Johnson in 1965 to accomplish such a major change in the American health care. 2 Clarion calls for repeal and lawsuits over its constitutionality appeared quickly after the passage of this historic reform effort. As of this writing it appears that the law may become a significant factor in the mid-term elections of 2010. Issues such as payment for abortion, mandates on individuals and companies to purchase or provide insurance with penalties (‘play or pay’), new regulatory requirements on insurance companies, costs of the new programs and how to pay for them, and the impact of reform on a burgeoning federal budget, including deficits continue to be discussed. Underlying this post-passage debate is the very real and pervasive effect of a slowly reversing recession and continued high unemployment rates. The nature of the debate that preceded passage has had a polarizing effect on American political discourse that will be a challenge, perhaps the greatest one, facing the young administration of President Obama. This grand debate on health care reform proved to be tortuous, partisan and often rancorous; full of accusations and counter-accusations, distortions and invidious comparisons; and burdened by the enormous complexity of the American health care system itself and the environment (a generational economic recession) in which an attempt at change was initiated.

The stakes in health care reform are enormous. Health care in America in 2009 consumed about one in every six dollars ($2.3-Trillion total) of the gross domestic product (GDP) and the costs are rising at a pace that greatly exceeds general inflation, although the rate of rise has attenuated somewhat since 2006. The venerated Medicare program, a government-funded but privately administered (though fiscal intermediaries) health insurance program for 15-million elderly (over 65 years of age) and disabled citizens (including over 500 000 Americans with end-stage renal disease), is predicted to be insolvent by 2017 or earlier. Medicare spending varies widely in America depending on health status, income level and other regional factors. 3 A promise to slow the projected growth of the Medicare program may delay insolvency, but will be difficult to actually accomplish. The Medicaid program, funded jointly by the Federal and State governments, provides care for ∼13-million individuals below a designated ‘poverty level’ of income, is severely strained by the economic crisis and is already greatly underfunded. Payment rates currently in Medicaid are so low than many doctors and hospitals eschew participation, as is their right. The new law will greatly increase the number of Medicaid recipients and thus will require an even greater transfer of federal funds to the states. Premium payments for private (non-governmental) insurance are skyrocketing, and many employers who pay a large portion of the premium costs, are balking at payment increases since these additional costs reduce their competitiveness on the world economic stage. The impact of the new law, and its provisions of new regulations governing private insurance, on the rate of rise in private insurance premiums is not yet known, but many believe that these rates will continue to escalate. Overall expenditures for health care in America have been rising steadily and dramatically, from 6% of GDP in 1965 to almost 17% in 2009 and projected to increase to over 20% of GDP by 2015. The escalating costs are fueled in large part by over abundant use of expensive high-technology, new and costly brand-name pharmaceuticals (including drugs that basically replicate the effects of already available drugs), limits on the availability of generic drugs and the accelerating aging of the society at large. Litigation costs of medical negligence claims and the practice of ‘defensive medicine’ have made a relatively minor impact on rising expenditures, despite the claims of organized medicine to the contrary. 4 The fundamental ‘fee-for-service’ model thrives on volume not on quality or efficiency of medical case. All of this has occurred while the uninsured (or underinsured) class has burgeoned to over 47-million individuals, including ∼13-million undocumented (non-citizen) persons (‘illegal aliens’). The new law will provide coverage by making subsidies available to purchase health insurance at affordable rates to ∼32-million of these previously uninsured or under-insured individuals, leaving only the undocumented aliens without some form of either public or private insurance.

The picture of the ‘health care system’ in America that emerged as the debate proceeded was not a pretty one, and the new law seems on the surface to be a step in the direction of correcting many of its most glaring deficiencies, but the fine details of the new law will only become apparent as its provisions are ‘rolled-out’ over the next 5–10 years. The desire to introduce reform into the health care system is not new to American politics. Indeed, for the last 80 years every President has half-heatedly or enthusiastically supported reform beginning with Franklin Delano Roosevelt who attempted, unsuccessfully, to include ‘universal health care’ as a part of his social security program enacted during the ‘great depression’ of the 1930’s.

The ‘dysfunctional’ American health care system that exists in 2010 and is about to undergo its most dramatic change in over 45 years can best be described as a unique hybrid of: (i) privately owned (for-profit) health insurance entities (largely employment driven); (ii) government funded but privately administered insurance plans for the elderly and disabled (Medicare); (iii) a State–Federal insurance program for a portion of the poor (Medicaid); (iv) a mixture of Federal government owned and operated systems (veterans administration, military and Indian health service hospitals and clinics); (v) a scattering of not-for-profit entitles owning hospitals and staffed by salaried physicians (e.g. the Kaiser Permanente System); and (vi) a conglomeration of locally supported (through taxation of the citizens) public hospitals and clinics, largely serving the poor and the uninsured (including non-citizens). Employment-based health insurance (self-insured or purchased via employer from an insurance company) currently accounts for over 60% of the health insurance coverage in America USA (see also Figure 1 ). 5

Health care coverage in America. 5

This ‘patchwork system’ has evolved over many decades. Its individual components are not well integrated. Its ‘fee-for-service’ approaches to payment encourages the dominance of high-technology oriented specialty practice and threatens the viability of primary care practice, by economically dis-incentivizing new entrants into this vital part of an integrated system of care. Control of burgeoning costs in the overall system has resisted mostly half-hearted efforts. Only a few sub-systems have been successful in melding specialty with primary care practice in ways that both control costs and provide tangible benefits of integrated care to subscribers. One of the great anachronisms of the American system was that unlike nearly all other health care systems in the industrialized world, it continued to adhere to the notion that access to affordable health care is a privilege and not a fundamental right for its citizenry. The enactment of the new law partly corrects this persistent anomaly in arguably one of the richest and most developed countries in the world.

Thus, reform of the ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘economically unsustainable’ American health care and health insurance systems has focused on changing the insurance rules, attempting to curtail the ever-escalating costs, and extending coverage to as many citizens as possible—all without fundamentally altering the ‘hybrid’ system of organization, dominated by ‘fee-for-service’ payment methods. Consideration of a single payer system of universal coverage (like Medicare in Canada) and a Federally owned and operated system of universal coverage [like the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK] were quickly rejected as not fitting the American model of ‘free-enterprise’ and were vigorously opposed by political conservatives who believe in limiting government intervention into fundamentally private matters, such as access to and choice of health care providers. Throughout the debate leading to enactment of the new law intense lobbying efforts by stakeholders (organized medicine, hospital associations, insurance entities, pharmaceutical companies, state and local government leaders, constituency groups, labour unions and the like) shaped the structure and complexity of the final legislation. In the end, each gave some and received some (or more than they gave), and the new law remedies some inequities but it creates others. Whether any reform will be successful in restraining the rising and unsustainable costs of health care remains be seen, although promises have been made. Keeping these promises will be another matter for another time.

One of the most striking aspects of the long and rancorous debate over health care reform in America was how the health systems in other countries were characterized and in many instances defamed in the media and in ‘town-hall’ style gatherings. For example, the single-payer, universal coverage Medicare system in Canada, managed at a provincial level in a prospective budgeting process, was widely characterized as ‘rationing by the queue’. Citizens of Canada sacrificed immediate access to a provider of their choice for the assurances that everyone would be covered but not necessarily at their beck and call. Canadians were described as ‘unhappy’ with their system and ‘flocking in droves’ to America for needed care. At the same time many American citizens were sending their prescriptions to Canada to avoid the high costs of drugs prevalent in the American system.

The NHS in England was also characterized, unfairly in my view, as understaffed, underfunded, operated by an inefficient and impersonal bureaucracy, within antiquated facilities having few amenities, with long-waiting times for elective procedures, limiting care for the elderly, lacking in freedom of choice of providers, and practicing covert ‘rationing by the queue’ as well as overtly, via the National Institute for Clinical Excellence program of comparative effectiveness evaluation linked to funding for drugs and procedures. At the same time, in America, comparative effectiveness research was being strongly encouraged by both federal and private funds. 6 In addition, clinical practice guidelines promulgated by professional societies and organizations were growing industries in the USA and elsewhere, but in general these were divorced from cost considerations.

In a fascinating, recently published and sometimes poignant book 7 (also called ‘naive’ by one reviewer 8 ), Washington Post correspondent. T.R. Reid provides unique insights and a wealth of historical information on how the ‘systems’ of health care coverage evolved in the various countries of world. 7 Reid notes that the beginning of health care systems can be traced to the ‘Iron Chancellor’ Otto von Bismarck’s pioneering social system inaugurated in Germany in 1883. The Bismarck model, as it is now known, uses a private but not-for-profit system of tightly regulated insurers jointly financed by employer and employee (or subsidized by the Federal government for the unemployed). Both doctors and hospitals are private entities and patients are given free-choice of plans and providers in a tightly regulated system of fees and re-imbursement. The creation of the NHS by Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan and Clement Atlee in the UK in 1948 brought forth a new system, known as the Beveridge model after Lord William Beveridge who virtually single-handedly wrote the landmark report in 1942 upon which the NHS was built. Unlike the Bismarck system, most facilities are owned and operated by the government and many providers (except General Practioners; GP) are employees of the NHS. Universal coverage is provided through taxation and a tightly regulated (and highly politicized) budgetary system. ‘Free at the point of delivery’ is a frequently repeated mantra. General practioners contract with the government for global care of panels of patients and access to specialists is controlled. A parallel private system of insurance has evolved but is used by only a minority of citizens. A third model also arose in the post-WW-II period in Canada, created first by Thomas ‘Tommie’ Douglas in the province of Saskatchewan in 1945 and Canada-wide in 1961 called Medicare . It is a universal coverage program in which the central government provides (via the Provinces) a national ‘single-payer’ health insurance in a tightly regulated budgetary system. ‘Out of plan’ care is allowed, as in the NHS. Doctors and hospitals are mostly private. A final ‘model’ system is also described by Reid; the ‘Out-of-Pocket’ model in which the care is provided on a cash basis—those without cash generally go un-served or depend on intermittent and episodic acute care in emergency rooms or charity clinics and hospitals. Outside of America the Bismark plan, or one of its variants, has been the most popular.

In America, all of these models can be found in some form. For the employed, under age 65 years it is like Germany (or France and Japan) except most insurance plans are for-profit (The new law puts a ‘cap’ on administraive cost); for the over 65 year age group, it is like Canada (or South Korea or Taiwan); for the Native Americans, Military or Veterans it is like the UK (and Cuba); and for the unemployed and uninsured it is like many countries that do not have an organized system of public health insurance, such as India, most parts of China and in equatorial Africa. In America, there are also a few models that resemble the NHS—the Kaiser-Permanente System and the Puget Sound Health Care system. These systems adopt an employed staff-model of managed care within a not-for-profit ownership system of hospitals and clinics linked to a premium-based insurance plans. Care is provided in a highly integrated system of primary care physicians and specialists. A full-range of services is available either within the system or on contract to other providers.

Of all of these, the Bismarck model provides the greatest choice of providers except when insurance and care is provided under one corporate umbrellas as is the case in some parts of Japan. The Bismarck model as applied in France is very highly regarded for ease of access, extent of coverage, overall cost, integration of health information systems (‘Carte Vitale’) and outcomes. The health care systems in the Netherlands and in Northern European countries are also highly esteemed and emulated. 9

However, regardless of the model system employed, there is general agreement, and much angst, that pressures of escalating cost (largely due to high use of advanced technology) are straining budgets and that rationing of care (either covert or overt) is increasing. Cost-containment remains as an over-riding issue in all systems of care, despite incremental reforms, including the new law in America. No effective plans for controlling ever-spiraling upward costs have yet been put in place—the new law in America is no exception. Government-sponsored universal health care systems, such as those in Canada, are reconsidering a role for private health care and have been largely unsuccessful in reducing costs.

The American hybrid system is viewed by many as fragmented, chaotic, difficult and complex to navigate, and harboring some disturbingly unfair insurance practices. Some of these may eventually be corrected by implementation of the new law, aptly called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPAC). Despite its shortcomings, 60–70% of Americans are ‘satisfied’ with their health care, according to polling results. The American system remains as specialty and fee-for-service dominated, expensive (over $7600 per capita per year), and high-technology oriented. Primary care is poorly integrated and electronic information systems are crude and underutilized. Prevention often takes a distant third place behind diagnosis and treatment in priorities for care. It is litigious, profit-driven and rife with ‘defensive-medicine’ and entrepreneurial practices. 10 Extra-ordinarily wide geographic variation in costs are well documented, 3 and not directly related to quality of care, which is mediocre in too many and excellent in too few sites. Until enactment of PPAC access to affordable care was not guaranteed to everyone leading to de facto rationing based on ability-to-pay. The main governmental support systems for health care are bordering on insolvency and without dramatic changes will be ‘bankrupt’ in the next decade. The bright spots are that America continues as a center of innovation and experimentation in new ways to deliver excellent care efficiently and inexpensively, is a training ground for some of the best doctors in the world and is a major site for research and development of new drugs and procedures. Non-Americans view the American system as wasteful of precious resources, full of redundant capacity, woefully insufficient in terms of access to primary care, only average in overall quality compared to cost (poor in value) and unconscionably out of step with the industrialized nations of the world by denial of the fundamental right to affordable health care for all of its inhabitants. The last of these justifiable criticisms has been, at least in part, corrected by the enactment of the new law.

The reforms signed into law by President Obama charts a new and uncertain path for the unique hybrid American health care system, and may inadvertently create a panoply of new issues. The overall costs of care and the efficiency of the system in which care is delivered will come under increasingly harsh scrutiny, particularly as the unsustainable costs of health care become more evident in each succeeding year. Crossing the moral divide and providing access to basic and affordable health care to nearly all its citizens is perhaps the most significant step taken by America in 2010, even though 13-million persons, mainly undocumented aliens, will likely remain outside the system. Improved emphasis on preventative care, comparative cost effectiveness and electronic medical records might help stem the oncoming financial tidal wave but the long-term economic benefits of these steps is far from clear. Universal health care provided by a single governmental organization seems quite unattainable at present. Fear of uncontrollable budget deficits, added tax burdens and a ‘government’ takeover of one-sixth of the nation’s economy have provided major, and perhaps crucial, resistance to change. Maintenance of free choice of providers, preservation of physician autonomy and reform of the litigation system of injury from sub-standard care is also high on the agenda.

The future of the American health care system, as reformatted by the new law, can only be seen dimly as the implementation phase shifts into gear. 11 Retention of the antiquated fee-for-service reimbursement system seems destined to fuel further cost inflation. The effect of mandates (‘play or pay’) on employees, individuals and employers to purchase or provide health insurance and the eventual costs to business is hard to estimate but early data suggests that health care insurance premiums will rise. Opening the flood-gates for issuance of millions of new insurance policies, heavily subsidized by federal and state governments, will only intensify the precarious state of the governmental systems, already strapped for cash. What the broadened access to medical care will do to the insurance industry, the public and private hospital systems and to a medical establishment already bereft of primary care providers can only be guessed. A serious shortage of primary care providers already exists in America, and the effect of new incentives for newly minted doctors to enter primary care instead of specialty careers is largely unknown. Trillions of dollars will have to be extracted from current programs over the next decade or so in order to pay for the newly insured without promoting unsustainable new budget deficits. Will future Congresses and Administrations have the courage to make these cuts and deal with the pain they will create in their constituencies? Only time will tell. It does appear likely that health care reform in America will have to be revisited soon and repeatedly to resolve the issue of costs in a way that promotes value and rational use of limited resources. Stay tuned.

The author is indebted to Dr Alan Hull, Dr Christopher O’Callaghan and Dr Christopher Winearls and to Mr Charles Baird for their review of an earlier version of this manuscript and their many helpful suggestions.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Author notes

- health care reform

- universal health insurance

- statutes and laws

- pharmacy (field)

- health care systems

- medical devices

- national health service (uk)

- barack obama

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2393

- Print ISSN 1460-2725

- Copyright © 2024 Association of Physicians of Great Britain and Ireland

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- CME & MOC

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The US Medicaid Program : Coverage, Financing, Reforms, and Implications for Health Equity

- 1 Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 2 Grantmakers In Health, Washington, DC

- 3 Department of Government and School of Public Policy, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

- Editorial Medicaid as a Driver of Health Equity Alice Hm Chen, MD, MPH; Mark A. Ghaly, MD, MPH JAMA

- Viewpoint Assessing Health Outcomes Attributable to Medicaid Expansion At 5 Years Heidi Allen, PhD, MSW; Benjamin D. Sommers, MD, PhD JAMA

- Viewpoint A Blueprint for Comprehensive Medicaid Reform Rebekah E. Gee, MD, MPH; David Shulkin, MD; Iyah Romm, BS JAMA

- Viewpoint Value-Based Care in the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation John E. McDonough, DrPH, MPA; Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS JAMA

- Viewpoint Medicaid’s Moment for Protecting and Promoting Women’s Health Mohammad Hussain Dar, MD; Charissa Fotinos, MD, MS; Christopher R. Cogle, MD JAMA

Question Who does Medicaid insure, how is the program financed and delivered, how have policies evolved, and how could reforms address racial and ethnic health equity?

Findings In 2022, Medicaid insured approximately 80.6 million individuals (56.4% from racial and ethnic minority groups in 2019). In 2020, estimated Medicaid spending was $671.2 billion (16.3% of total US health spending). The proportion of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid managed care was 69.5% in 2019, 45 states have pursued 139 Medicaid delivery system reforms from 2003 to 2019, and 38 states and Washington, DC, have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Racial and ethnic health disparities are common within Medicaid, and evidence on the association of Medicaid policies and reforms with achieving racial health equity remains limited.

Meaning Medicaid is an important source of insurance and accounts for substantial health care spending. Medicaid reforms have expanded coverage and provide further opportunities to reduce disparities and address health inequities.

Importance Medicaid is the largest health insurance program by enrollment in the US and has an important role in financing care for eligible low-income adults, children, pregnant persons, older adults, people with disabilities, and people from racial and ethnic minority groups. Medicaid has evolved with policy reform and expansion under the Affordable Care Act and is at a crossroads in balancing its role in addressing health disparities and health inequities against fiscal and political pressures to limit spending.

Objective To describe Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and spending and to examine areas of Medicaid policy, including managed care, payment, and delivery system reforms; Medicaid expansion; racial and ethnic health disparities; and the potential to achieve health equity.

Evidence Review Analyses of publicly available data reported from 2010 to 2022 on Medicaid enrollment and program expenditures were performed to describe the structure and financing of Medicaid and characteristics of Medicaid enrollees. A search of PubMed for peer-reviewed literature and online reports from nonprofit and government organizations was conducted between August 1, 2021, and February 1, 2022, to review evidence on Medicaid managed care, delivery system reforms, expansion, and health disparities. Peer-reviewed articles and reports published between January 2003 and February 2022 were included.

Findings Medicaid covered approximately 80.6 million people (mean per month) in 2022 (24.2% of the US population) and accounted for an estimated $671.2 billion in health spending in 2020, representing 16.3% of US health spending. Medicaid accounted for an estimated 27.2% of total state spending and 7.6% of total federal expenditures in 2021. States enrolled 69.5% of Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care plans in 2019 and adopted 139 delivery system reforms from 2003 to 2019. The 38 states (and Washington, DC) that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act experienced gains in coverage, increased federal revenues, and improvements in health care access and some health outcomes. Approximately 56.4% of Medicaid beneficiaries were from racial and ethnic minority groups in 2019, and disparities in access, quality, and outcomes are common among these groups within Medicaid. Expanding Medicaid, addressing disparities within Medicaid, and having an explicit focus on equity in managed care and delivery system reforms may represent opportunities for Medicaid to advance health equity.

Conclusions and Relevance Medicaid insures a substantial portion of the US population, accounts for a significant amount of total health spending and state expenditures, and has evolved with delivery system reforms, increased managed care enrollment, and state expansions. Additional Medicaid policy reforms are needed to reduce health disparities by race and ethnicity and to help achieve equity in access, quality, and outcomes.

- Editorial Medicaid as a Driver of Health Equity JAMA

Read More About

Donohue JM , Cole ES , James CV , Jarlenski M , Michener JD , Roberts ET. The US Medicaid Program : Coverage, Financing, Reforms, and Implications for Health Equity . JAMA. 2022;328(11):1085–1099. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.14791

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 August 2022

What next for the polyclinic? New models of primary health care are required in many former Soviet Union countries

- Nigel Edwards 1 &

- Igor Sheiman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5238-4187 2

BMC Primary Care volume 23 , Article number: 194 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2511 Accesses

Metrics details

There is unfinished reform in primary care in Russia and other former Soviet Union (FSU) countries. The traditional ‘Semashko’ multi-specialty polyclinic model has been retained, while its major characteristics are increasingly questioned. The search for a new model is on a health policy agenda. It is relevant for many other countries.

In this paper, we explore the strengths and weaknesses of the multi-specialty polyclinic model currently found in Russia and other FSU countries, as well as the features of the emerging multi-disciplinary and large-scale primary care models internationally. The comparison of the two is a major research question. Health policy implications are discussed.

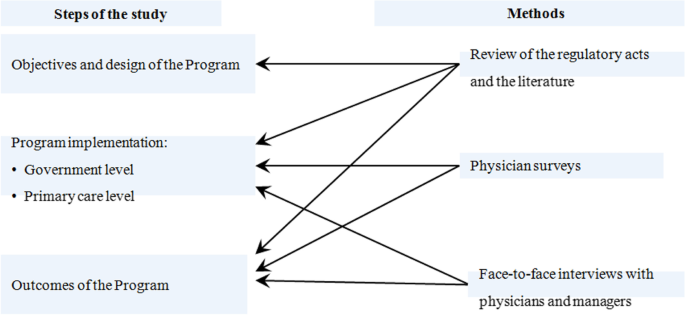

We use data from two physicians’ surveys and recent literature to identify the characteristics of multi-specialty polyclinics, indicators of their performance and the evaluation in the specific country context. The review of the literature is used to describe new primary care models internationally.

The Semashko polyclinic model has lost some of its original strengths due to the excessive specialization of service delivery. We demonstrate the strengths of extended practices in Western countries and conclude that FSU countries should “leapfrog” the phase of developing solo practices and build a multi-disciplinary model similar to the extended practices model in Europe. The latter may act as a ‘golden mean’ between the administrative dominance of the polyclinic model and the limited capacity of solo practices. The new model requires a separation of primary care and outpatient specialty care, with the transformation of polyclinics into centers of outpatient diagnostic and specialty services that become part of hospital services while working closely with primary care.

The comprehensiveness of care in a big setting and potential economies of scale, which are major strengths of the polyclinic model, should be retained in the provision of specialty care rather than primary care. Internationally, there are lessons about the risks associated with models based on narrow specialization in caring for patients who increasingly have multiple conditions.

• The Semashko polyclinic model has lost strengths due to excessive specialization.

• Solo and group PHC practices are no longer suitable to manage multimorbidity.

• A new ‘extended general practice’ reorients the health system towards PHC.

• Restructuring polyclinics is possible by transforming them into outpatient specialty units of hospital structures.

Peer Review reports

In the former Soviet Union (FSU) and some Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, the traditional ‘Semashko’ Soviet multi-specialty polyclinic model, originally developed in the 1930s, has been retained [ 1 ]. However, in many rural and some urban areas of FSU countries, the traditional polyclinic model shifted towards solo and group primary care practices in the 1990s in response to policymakers’ demands for stronger primary health care (PHC). This shift towards solo and group practices continues today in many countries of this region [ 2 ].

The existing PHC models are currently facing a number of challenges. The professionals running standalone practices are struggling to respond to a growing proportion of people with multi-morbidity and complex healthcare needs, in a context of underdeveloped and underfunded supportive services, such as social care, rehabilitation, long-term care and palliative care [ 3 ]. While in theory, the mostly urban polyclinic-based generalists could be delivering more comprehensive care, in practice, patients seek out ‘narrow’ specialists based in polyclinics (cardiologists, neurologists, etc., further referred as specialists) instead for the management of relatively common conditions that would be in the scope of PHC providers in other countries [ 1 ]. Neither the polyclinic approach taken in urban areas nor the rural solo/group practice are functioning well and new approaches are needed.

In this paper, we focus on the Russian Federation and consider a number of questions that policy makers, payers and medical leaders could discuss when planning changes to their services. Firstly, what are the current strengths and weaknesses of the polyclinic model currently found in Russia and other FSU countries and does this mean that there are some aspects that should be preserved. Secondly, what are the features of the emerging multi-disciplinary and large-scale primary care models internationally. Thirdly, which elements of the new models of primary care could be adapted to the Russian and other similar settings. We argue the case that polyclinics should be transformed – not into the model of standalone or small group practices that is common – but instead into the ‘extended general practice’ model seen across Europe that re-orients the health system towards comprehensive PHC delivered by multi-disciplinary teams.

The evidence on the strengths and weaknesses of the polyclinic model set out in this paper is based on a review of the literature and two physician surveys. The review is focused on: a) determining characteristics of multi-specialty polyclinics in Russia, indicators of their performance and the evaluation in the specific country context; b) description of the emerging extended PHC practices internationally; c) comparison of the two models. We searched MEDLINE using the query: (Ambulatory Care Facilities[mh] OR polyclinic) AND (model OR type OR semashko) AND (USSR OR russia OR europe OR european union) AND 1990:2022[dp]. 1614 findings were checked manually and 36 were relevant. We also used sources snowballed from these reports and the grey literature related to Russian health care, including those in limited circulation, unpublished documents, memorandums, and presentations from our personal collections covering more than twenty years.

The surveys of Russian physicians are designed to explore the managerial environment for their performance of the staff in polyclinics. Firstly, the managerial control is evaluated via questions like: Is the number of patient visits planned by the polyclinics’ administrators? Does the failure to implement plans can cause a reduction in physicians’ remuneration? Who determines the average length of a patient visit and what happens if it is regularly violated? Are physicians involved in managerial actions to improve the performance of polyclinics?

Secondly, we assess the level of physicians’ clinical autonomy. The examples of questions: Do you select patients for check-ups and screening or rely on administrative decisions? Do your referrals to hospital admissions and CT/MRI tests require the authorization of polyclinics administrators? Which indicators of performance are used for your reporting to the administration?

Thirdly, teamwork and coordination of providers in polyclinics is evaluated. We ask questions about their joint planning of curative activities, inter-discipline consultations and training sessions, as well as the leading role of district physicians in the team—in joint planning and managing chronic cases.

International comparisons of primary care performance are based on the national and OECD databases.

A small-scale survey of polyclinics’ physicians was conducted in January 2020 in three urban polyclinics in Moscow city and Moscow oblast (the region near Moscow). They represent a big multi-specialty urban polyclinic with an average number of staff of around 80–90 health workers. In Moscow city, these polyclinics have been consolidated into bigger outpatient centers with three to five polyclinics each. But this new level of administration was not taken into account, to reflect the usual pattern of administration of polyclinics in Russian big cities. The questions relate only to the staff of individual polyclinics (not their amalgamation). The special area of interest is the attitude of generalists and specialists. A list of 13 questions (appendix 1 ) was sent to all three polyclinics’ physicians through the Russian social network “Vkontakte”. This survey was anonymous, respondents were not compensated and were reassured that any negative feedback would not affect them. The postgraduate students of the National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow) dispersed the survey. It was sent to 129 physicians, 103 physicians (80%) responded, including 67 district physicians and 37 specialists. The questionnaire had the same questions to all respondents, and the latter were required to answer all questions by the design of the survey. Therefore, the response rate was the same for all questions. Similarly, the fraction of participants and respondents was the same for each question. Ten physicians on the list were randomly selected and approached directly for face-to-face interviews.

This small-scale survey doesn’t represent all physicians in the country, but it can provide additional evidence to our observations on the limitations of professional autonomy in polyclinics. Some questions from this survey were also used in our recent study of the national preventive program [ 4 ].

This survey was designed to receive more detailed evidence of the level of interaction between professionals in polyclinics, including the exchange of information about patients’ emergency calls, the level of awareness of patients’ hospital admissions, the involvement of polyclinics' physicians in the rehabilitation activities after hospital admissions of stroke and heart attack cases. A special area of interest is the referral pattern of district physicians: what is the share of first visits that is referred to specialists?

The second survey was conducted online in October 2020 in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic through the mobile ap “Handbook of Physician” (available in Google Play and AppStore) with 540 thousand registered users. 2316 physicians responded to the survey. They represented 81 of 85 regions of the country. 1118 respondents worked in polyclinics (48%), 1068 – in hospitals (46%), the rest – in other settings. Since the survey was designed to look at broader issues of service integration (between polyclinics, hospitals, emergency care centers, etc.), we selected respondents that worked in polyclinics and studied their responses to the questions about the level of integration within polyclinics. All questions were asked with the note “in regular conditions of work before March 2020”. This part of the questionnaire is provided in appendix 2 .

Survey 2 covers generalists and specialists in the staff of polyclinics in practically all types of primary care settings in Russia which vary in size. A high popularity of the ap in all Russian regions and a substantial number of respondents that represent various medical organizations and physician specialties make the survey a reliable instrument of the study.

The polyclinic model

The polyclinic model was established in the USSR in the early 1930s and inherited by FSU and some CEE countries. The polyclinic is a multi-specialty entity providing both primary care and most outpatient specialty care. Typically, there are separate clinics for adults and children and each has a catchment area and a patient list managed mostly by district therapists, district pediatricians and general practitioners (GPs) – all of which are collectively referred to as ‘district physicians’ (DPs). Mental health care is not provided by this service – this is the area of specialty organizations. GPs with a broad task profile are only emerging and account for only 15% of DPs. The catchment population of polyclinics in big urban areas ranges from 30,000 to 120,000 people [ 5 ].

People can choose a polyclinic, and most choose the provider closest to their place of residence. Patients enrolled in a polyclinic form the patient list. According to federal regulations, DPs and GPs act as gatekeepers and refer patients to specialists and hospitals. But many regions loosen the requirements of gatekeeping: patients increasingly see specialists directly without a referral from primary-care physicians.

There has been a trend towards specialization within PHC since the 1990s. The Semashko model of a district unit with mainly a district physician has given way to multi-specialist polyclinics, which currently employ 15–20 categories of specialists in big urban areas (including for example, cardiology, gynecology, surgery, etc.), and three to five categories in small cities. Rural and small city areas are served mostly by small solo practices. Outpatient specialists account for around two-thirds of polyclinic staff and service activity [ 5 ]. It is important to note that the increased professional diversity of the polyclinic staff has been based on a growing number of medical specialists rather than nurses and other allied health professionals. The role of nurses is limited to non-clinical functions. The nurses to physicians ratio is only 2.1, as against 3.0 in Germany, 3.8 in Canada and 4.3 in the US ([ 6 ], p.179).

Legislation defines the polyclinic as a PHC model, which consists of ‘primary physician service’ (care provided by DPs) and ‘specialty primary care’. The latter includes some care equivalent to that provided by outpatient specialists in Western countries, but also care that is effectively managed by family doctors elsewhere, for example, angina and type 2 diabetes.

The governance of polyclinics is highly centralized. The regional health authority appoints directors of polyclinics and manages their performance, most of the rules and patterns of care provision are set by the federal Ministry of Health. The administration of polyclinics is a multilayered structure: a director, a medical director, a few deputies, the head of the district unit, and heads of specialty and diagnostic units. Most polyclinics are state owned and staffed with salaried medical personnel. The growing private sector is also based on this model.

The majority of a polyclinic’s financial revenue is derived from a regional mandatory health insurance (MHI) fund on a capitation basis. But the revenue of a polyclinic can be reduced if it has not reached a minimum number of visits. This target is set and controlled by the regional health authority and MHI fund (which jointly act as a purchaser of care). When there is a risk of not reaching a planned number of visits, the administration of polyclinics has to encourage multiple referrals of patients. Polyclinics’ preventive services are paid for on a fee-for-service basis. The rates of payment are set for a fixed package of services under a so called “program of dispensarization” (a nation-wide vertical program of check-ups and screenings). The control of the actual number of preventive services is conducted by MHI funds and administration of polyclinics. While this method of payment motivates physicians to implement the program, it limits their professional autonomy on the choice of preventive services for an individual. They have to provide the entire bundle of services to be reimbursed, irrespective of the actual need of a patient [ 4 ].

The salary of medical personnel has fixed and variable parts. The latter is based on some pay-for-performance indicators, including the number of visits managed by the individual physician, number of patient complaints and some preventive services. The variable part is determined individually by administration.

Evaluation of the model

There is an unfavourable context for the operation of the urban polyclinic model in modern Russia. There are low levels of health funding (currently, public funding is around 3.5% of GDP), there is a 30% shortage of district therapists, structural distortions in the workforce which are explored below, a hospital-centred model and little focus on chronic disease management [ 7 ].

A major strength of the model is its capacity to provide an easy access to primary and specialist care, at least in theory. Patients can see a DP, receive diagnostic services and have consultations with specialists ‘under one roof’. Specialists may or may not be located in the same premises. But even if they are, this does not mean that patients can have tests and see specialists the same day. This process usually takes weeks because of the shortage of specialists [ 7 ].

Polyclinics have a number of potential advantages due to the consolidation of service delivery. These include additional leverage to implement care pathways and shared use of capital investment resources. Polyclinics can also centralize administrative and support services, with potential economies of scale. Furthermore, large settings can redistribute resources across geographic areas through setting up small branches in remote areas and polyclinic workers can stand in for each other in case of illness or holidays. There is evidence that these strengths are not fully realized in Russia and managerial action is needed to deal with this [ 8 ].

Another potential strength of the polyclinic model is better financial sustainability relative to solo and group practices. The model has enabled the introduction of a fundholding scheme in some regions of Russia, with polyclinics as major financial risk-bearers. Within a short period of its implementation (four to five years in most regions), this has allowed strong economic incentives to be used to increase the role of PHC in the health system [ 5 ].

The larger scale of polyclinics also allows them to respond to national health programs more effectively. For example, larger scale has allowed the implementation of the recent federal program called “Resource-saving polyclinics” that covers most big polyclinics in the country. The objective is to improve the efficiency of internal processes through new appointment systems, separation of patient flows across individual providers, improve electronic communication and develop better organization of the working space, etc. These innovations are more cost effective in big settings. The response to COVID-19 is also facilitated by large-scale facilities.

There are, however, a number of major weaknesses of the polyclinic model.

First, strong administrative pressure on physicians in polyclinics and their limited professional autonomy . Physicians are poorly involved in the management of polyclinics. They work according to the rules determined by polyclinics’ administrators, who in turn follow the commands of the federal and regional health authorities. Administrators set DPs’ catchment areas, plan the number of patient visits, develop the norms for the average length of a patient visit, determine the scope of preventive services and their coverage, ration expensive diagnostic resources for each physician and approve referrals to hospital.

The first survey provided evidence of managerial control and limited professional autonomy:

66% of physicians reported that plans for the number of patient visits are developed by the polyclinics’ administrators. Only 34% plan this activity themselves.

59% indicated that the failure to implement plans on the number of visits can cause a reduction in their remuneration.

66% reported ‘administrative action’ if the norms for the average length of a patient visit are regularly violated.

Only 25% of physicians select patients for check-ups and screening programmes themselves after assessing their risk factors. The rest rely on administrative decisions on the targeted populations. The share of those who select patients for chronic disease management themselves is higher though – 69%.

Just under 50% reported that their referral of patients to hospital requires the authorization of heads of specialty units, 15% – the deputy director, 12% – medical commissioners and 6% – other actors. There is a similar distribution of responses for the authorization of CT and MRI referrals.

28% of respondents reported administrators’ ‘excessive administrative regulation’ of clinical decisions.

Second, the loss of the primary care providers’ leading curative and coordination roles . In Russia, DPs are traditionally seen as gatekeepers for access to specialty services. Theoretically, they are supposed to act as a patient’s guide through the health system and ensure continuity of treatment. However, a high level of polyclinic care specialization distorts the coordination role of primary care providers. In a big multi-specialist entity with a growing division of labour and many specialists working together, many traditional curative functions of DPs are delegated to specialists. It is hard for DP to resist the temptation to refer a patient to a specialist next door. Clinical recommendations, pathways and quality control actors tend to incentivise specialist consultation. Polyclinics’ administrators often encourage referrals to specialists to meet the specified minimum number of visits. The task profile of DPs’ curative work therefore gradually narrows. They deal with a few simple diseases, and the majority of patient care (even gastritis, ulcer, bronchitis) is managed by specialists [ 5 ]. Contrary to GPs, district physicians are allowed to practice without postgraduate training. As a result, a DP’s coordination role also narrows.

The first survey provides the following evidence of a lack of cooperation and coordination in the urban polyclinic:

35.5% of DPs said that the development of plans for the joint management of cases by DPs and specialists did not occur, 45.2% said it ‘rarely’ occurred, 9.7% said it ‘sometimes’ occurred and only 1.6% said it ‘always’ happened. This is contrary to the expectation that a big entity facilitates joint working.

Training sessions for DPs with the involvement of specialists were reported as a regular event by only 4% of polyclinics’ physicians, as a rare event by 35%, while the rest of the respondents indicated their absence.

Only 3.2% of respondents reported medical case conferences as a regular event.

This survey allows us to determine a task profile of DPs and their role in a multi-specialty team:

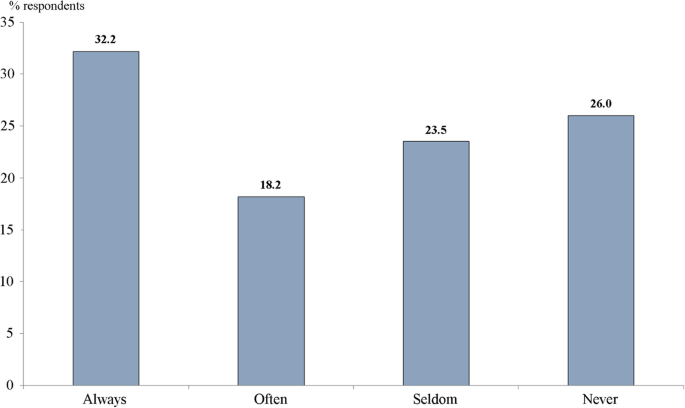

Only 29,7% of DPs reported that they referred to specialists less than 10% of patients, that is had referral patterns similar to European GPs who referred from 5 to 15% of patients to specialists [ 2 ]. The bulk of Russian physicians referred every second patient to specialists, indicating an excessive specialization of primary care and a limited task profile of generalists. Unsurprisingly, only 26% of DPs reported themselves as “captains of the team” in joint planning of curative activities.

The second survey provides a more detailed evidence of a level of integration in Russian polyclinics. Its results were compared with similar estimates made in 2012 [ 9 ].

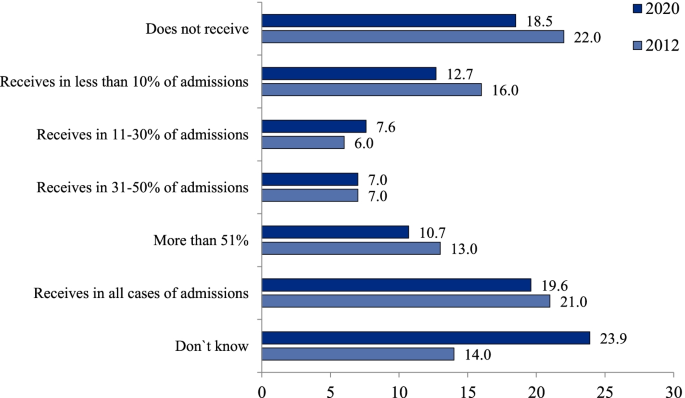

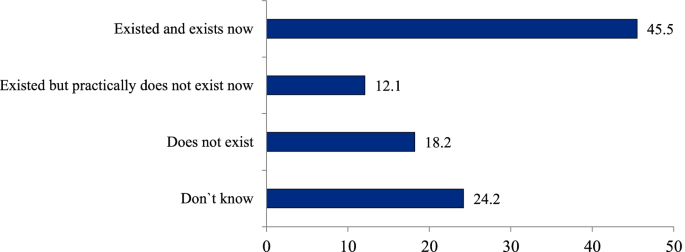

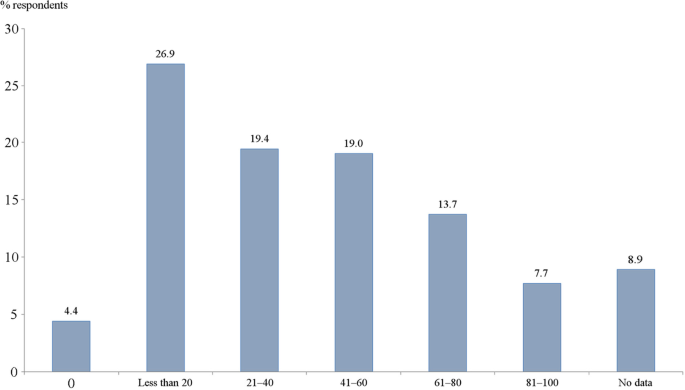

An important indicator of the interaction of polyclinics and hospitals is the level of information exchange between them. Only 19.6% of respondents said that their polyclinics received the information about all hospital admissions of patients in their catchment area in 2020; 18.5%—didn’t receive it at all; 23.9% could not answer this question, which was close to the negative answer. The level of physicians’ awareness of hospital admissions in 2020 was even less than in 2012 (Fig. 1 ). This in turn complicates the continuity of care after hospitals admissions. The survey indicates that even for “catastrophic” cases of a stroke or a myocardial infarction the practice of visiting patients within the first days of their hospital admission is not common: it is reported only by 45.5% of respondents (Fig. 2 ).

Distribution of polyclinic physicians’ responses to the question `How often does your polyclinic receive information about hospital admissions of patients in the catchment area`, % (survey 2)

Distribution of polyclinic physicians’ responses to the question `Does your polyclinic have a regular practice of visiting patients within first days after their hospital admission with a stroke or a myocardial infarction`, % (survey 2)

Substantial efforts have been undertaken recently in introducing modern IT in medical facilities, but a national electronic medical record system has not been built yet. Only a few big cities have a system that covers both outpatient and inpatient facilities. The majority of outpatient physicians don’t know much about care utilization on other stages of service delivery.

Third, the limitation of outpatient specialists’ task profile and curative competences. For the reasons mentioned above, a multi-specialist polyclinic generates demand for specialty care . This demand is served by two specific types of specialist who provide only outpatient care: those who work in polyclinics dealing only with simple cases as first-contact providers; and those who provide only inpatient care for complex cases. The former face the problem of professional isolation from their counterparts in hospitals and have limited clinical competences, for example, they do not carry out operations or manage difficult cases. The latter have very limited responsibilities for outpatient consultations. Thus, a multi-specialist polyclinic not only generates demand but also requires a growing supply of specialists. Only 13% of physicians in Russia are generalists [ 5 ], compared with 27% in the UK, 29% in France and 48% in Canada, with 23% being the average for the OECD countries [ 6 ].

Fourth, the lack of economic incentives in a multi-specialty polyclinic . A salaried status and the principle of a ‘common pot’ inherent in a big entity decrease the economic motivation of polyclinics’ health workers relative to their self-employed counterparts in solo and group practices. The first survey of physicians indicates that their income is poorly linked to the financial revenue of the polyclinic: 49% of respondents reported that they did not see this link, 37% saw the link, while the rest did not answer.

Fifth, a low potential for patient choice of PHC providers and their competition . Russian citizens have a strong interest in provider choice but the majority cannot choose due to the prevalence of big entities. Also, there is a growing interest in physician practices that are smaller and therefore closer to patients’ homes.

Some indicators of polyclinics’ performance

Large-scale provision of primary care in polyclinics might be expected to reduce the burden on hospitals, but this has not been the case. In spite of a relatively high number of outpatient physician consultations (9.9 per person), the hospital admission rate in Russia is 52% higher than the OECD average and even higher than in European countries, including Estonia, which had similar high levels of admission in the first post-Soviet period and then had rejected a multi-specialty polyclinic model. A poor-performing primary care system in Russia increases the probability of acute deterioration in people living with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure and some other illnesses, therefore requires hospital admissions that are avoided internationally. Together with a high average length of hospital stay, a significant frequency of admissions produce a very high total utilization of inpatient care: bed-days per capita in Russia is more than two times higher than the OECD average (Table 1 ). Similarly, the utilization of emergency care per capita in Russia is nearly three times higher than the average for OECD countries [ 5 ].

This can be attributed to a number of factors. Firstly, inpatient care remains a major priority of health policy, with a major proportion of funding going to this sector. Secondly, the curative capacity of outpatient specialists in polyclinics is lower than that of their counterparts in hospitals because they deal only with relatively simple cases. Thirdly, patients prefer to be admitted to a hospital due to a traditional mistrust of polyclinic physicians. Administrative pressure – a major characteristic of the model – does not allow patients’ trust to increase.

A theoretically important feature of the polyclinic model is its focus on preventive activities but this does not happen in practice. Physicians and other professionals have no discretion over their patients’ involvement in large-scale health programs and cannot adapt them to the specific environment of their work. An example is the current federal program of ‘dispensarization’, which covers all adults with check-ups and screenings and is implemented according to standard rules. Polyclinics’ physicians are not involved in the design of the program and cannot choose the scope of preventive activities, the targeted populations or the forms of follow-up activities for identified cases of chronic disease. This has caused a number of serious problems: an overburden on DPs, distortions in reporting, poor communication between providers of preventive and curative services, excessive prescribing of diagnostic tests and a lack of follow-up activities for identified cases. The survey of physicians conducted online in April 2019 (randomly selected 1103 physicians) demonstrated that only 7.7% of respondents indicated that a set of actual curative activities met the requirements of a pattern of dispensary surveillance issued by the Federal Ministry of Health. The analysis of medical records of 7043 patients after their hospital admissions with a stroke or a myocardial infarction indicates that nearly half of these patients have not seen a doctor during the year prior to admission [ 11 ].

Heart attacks and other cardiac ischemia mortality rate in Russia is 310 per 100 000 population (in 2019) – nearly three time higher than the average OECD (110). There is a similar gap is for stroke mortality (180 vs 60) ([ 10 ] p. 91).

Polyclinics’ responses to challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate both the strengths and weaknesses of the model. There is some evidence of its potential for the mobilization of resources, which has allowed polyclinics to allocate resources to the most vulnerable areas of service delivery and organize flexible testing and tracing of patients and their contacts. This has been facilitated by polyclinics being instructed to implement government policy through decrees and commands. On the other hand, physicians in polyclinics do not have the competences required to take on a major role in triaging or managing new cases. Hospitals have become overburdened as they have taken on this role. The excessive specialization of primary care has also prevented continuity of outpatient care for people with coronavirus.

Discussion: where next for primary care in FSU countries?

Developing a new approach – learning from elsewhere.

FSU and some CEE countries are seeking a new model of PHC that combines the strengths of solo, close-to-home practices and large multi-specialist polyclinics while addressing their weaknesses. A shift to the model of small independent primary care practices, that have been common in Western Europe, may not be a reasonable alternative to the polyclinic model. Firstly, because patients in Russia do not favour this model and its historic legacy means they will try to bypass it. Secondly, the scale of change in the workforce required would be very large and potentially impractical. Thirdly, and most significantly, it would potentially mean losing the opportunity to adopt a more modern and appropriate approach to primary care rather than copying an old model that is starting to exhibit difficulties.

In a number of countries there has been growing interest in the development of larger multidisciplinary primary care practices or networks in response to the growing complexity of patients, the desire to provide more care locally, demand for extended hours and pressures on the workforce. In Spain [ 12 ], France [ 13 ] and the UK [ 14 ] it is increasingly common for primary care services to cover in excess of 20,000 population and these are very different from the existing polyclinics as they rely on a much wider spectrum of primary care expertise including pharmacists, a number of different therapy disciplines, mental health professionals, dentists, opticians, hearing aid technicians and dieticians. They also have an extensive role for nurses. They may also provide a base for social work and staff who can assist patients with non-medical problems and who can direct people to services that can help them. Larger units may have administrative staff to reduce the time taken on non-clinical tasks by health professionals.

The main points of difference to the current multi-specialty polyclinic model in Russia are the following:

The level of narrow specialization of care is much higher in the polyclinic model than in an ‘extended general practice’ model. Groenengen et al. (2015) [ 15 ] found that the median number of additional professionals in extended general practice is five to six in Australia, England, Iceland, New Zealand, Poland, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden, while in Russia it may reach 20 categories [ 5 ]. This excessive specialization has destroyed the polyclinic’s original design as a centre of PHC based on teamwork, coordination and continuity of care and resulted in a fragmented provision of services with the duplication of specialists in outpatient and inpatient settings.

The curative and coordination role of generalists remains central in the extended practices in Western Europe, while it tends to be small in the polyclinic model: specialists replace rather than supplement generalists.