Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

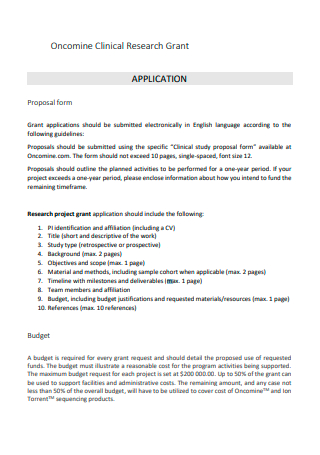

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research pp 249–254 Cite as

How to Write a Winning Clinical Research Proposal?

- Christian Lattermann 8 &

- Janey D. Whalen 9

- First Online: 02 February 2019

2313 Accesses

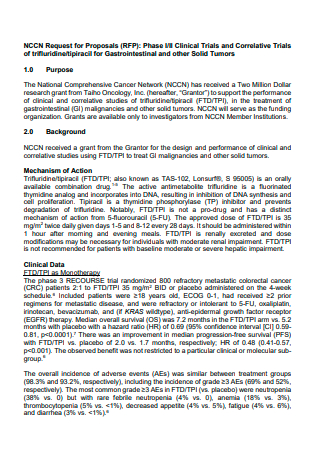

This chapter addresses general approaches towards writing a clinical research proposal. The landscape in research has changed in the last decade and has become more translational in nature. Therefore, research proposals are read and evaluated by scientists from various fields that may not be intricately familiar with specific techniques and technique-related jargon. This chapter is designed to address the need for more translational and reviewer-friendly proposal writing and is built on errors and mistakes commonly seen in research proposals.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Shapiro FR. The Yale book of quotations, section: Blaise Pascal. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2006. p. 583.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Christian Lattermann

Icartilage.com, Boston, MA, USA

Janey D. Whalen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christian Lattermann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

UPMC Rooney Sports Complex, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Volker Musahl

Department of Orthopaedics, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Jón Karlsson

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Kantonsspital Baselland (Bruderholz, Laufen und Liestal), Bruderholz, Switzerland

Michael T. Hirschmann

McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Olufemi R. Ayeni

Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA

Robert G. Marx

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, IL, USA

Jason L. Koh

Institute for Medical Science in Sports, Osaka Health Science University, Osaka, Japan

Norimasa Nakamura

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 ISAKOS

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Lattermann, C., Whalen, J.D. (2019). How to Write a Winning Clinical Research Proposal?. In: Musahl, V., et al. Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_27

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_27

Published : 02 February 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-662-58253-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-662-58254-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Advertisement

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Preparation of the Investigator for a Proposal

The research proposal, insights into the reviewer's perspective, conclusions, writing successful research proposals for medical science .

(Schwinn) Professor of Anesthesiology and Surgery; Associate Professor of Pharmacology/Cancer Biology, Duke University Medical Center; Senior Fellow, Duke Pepper Aging Center.

(DeLong) Associate Professor, Division of Biometry and Medical Informatics, Duke University Medical Center.

(Shafer) Staff Anesthesiologist, Palo Alto VA Health Care System; Associate Professor of Anesthesia, Stanford University.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

- Search Site

Debra A. Schwinn , Elizabeth R. DeLong , Steven L. Shafer; Writing Successful Research Proposals for Medical Science . Anesthesiology 1998; 88:1660–1666 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199806000-00031

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

HIGH-QUALITY research proposals are required to obtain funds for the basic and clinical sciences. In this era of diminishing revenues, the ability to compete successfully for peer-reviewed research money is essential to create and maintain scientific programs. Ideally, the essentials of “grantsmanship” are learned through observation and participation in grant preparation, but the training environment experienced by most physicians typically focuses on clinical skills. Most physicians are never exposed to a research environment and therefore do not learn how to write grants. The result is that many clinical studies, even when designed by skilled clinicians and those that address important clinical questions, often do not compete successfully with proposals written by basic scientists. This creates a perception that clinical studies are not favorably viewed by research review committees. The opposite is probably closer to the truth; research review committees are very keen to fund excellent clinical research. Although greater numbers of researchers with Ph.D. degrees have applied for National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants compared with researchers with M.D. degrees over the last 10 yr, funding rates (percent applications funded) have remained approximately the same for these investigators ( Figure 1 ; 1995 success rates: all degrees, 6,759 [26.8%]; M.D. - Ph.D., 370 [23.1%]; M.D., 1,518 [28.1%]; Ph.D., 4,746 [26.8%]; other degree, 125 [23.1%]).[section]

![clinical research proposal writing Figure 1. Overall success rates for NIH funding of scientific applications, 1986 - 1995. No difference in funding rate is observed between applicants holding M.D. versus Ph.D. degrees. As the success rate for first-time applications was 11.3% in 1993, it is apparent that resubmission of a revised application significantly increases the overall chance of having research proposal ultimately funded.[section]](https://asa2.silverchair-cdn.com/asa2/content_public/journal/anesthesiology/88/6/10.1097_00000542-199806000-00031/4/m_31ff1.png?Expires=1714478590&Signature=DF7-UG0u~UJKg~wyOGmJ4waYoPjUxVIrlVBxQ0~ghz-Jf-oIsRlCqxm4Qt3wH4M-l6wWrzOwEaqCekVUFcbGhitKEhM8DIDKCOI~6XmRDAUa~phZZz2tt9Pl7RaAw2tnyOQTOVU-cDkRhxGNGTz1BeeAZ9Tg4v73jLJ6ltntapoy6Sp0kQBf0iHxYPBO3RDE~ds4jxXNEMLjNbzXSIWapjuJyb1rSYj0j9tRPeFq6UHlMddud6m4R67UnrD5KsRECAkYP14B9KZFv06k7IiCdsDfrxfswUJ2jY3gDlsQDLYqKaaXRWiCHHeE4fNLtu5jR-DXfly1vlt4igxeVh8sjw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Figure 1. Overall success rates for NIH funding of scientific applications, 1986 - 1995. No difference in funding rate is observed between applicants holding M.D. versus Ph.D. degrees. As the success rate for first-time applications was 11.3% in 1993, it is apparent that resubmission of a revised application significantly increases the overall chance of having research proposal ultimately funded.[section]

Capable medical researchers ultimately write research proposals for funding by the NIH. Standards of excellence for NIH grants are high (only the top [almost equal to] 20% of grants are funded). Research questions posed must be hypothesis driven; the investigator must be qualified to perform the study; and preliminary evidence should be presented demonstrating that the research is feasible and will answer the questions posed. The goal of this article is to review important elements of successful research proposals, with emphasis on funding sources available to the anesthesiology community. Two important anesthesia-specific organizations exist to support anesthesia research - The Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (FAER, an organization under the auspices of the American Society of Anesthesiologists) and the International Anesthesiology Research Society (IARS).

Successful applications for research support from FAER and IARS have many of the characteristics of grants funded by the NIH and other peer-reviewed funding sources. These characteristics include (1) a highly qualified investigator(s);(2) for junior investigators, a mentor with a successful track record in scientific investigation, peer-reviewed funding, and mentorship of fellows and faculty;(3) a supportive academic environment; and (4) a scientifically sound proposal. Each of these characteristics is discussed in the subsequent sections.

Training of the Investigator

One of the most important components of a successful research proposal is a well-trained investigator. Training in clinical anesthesia is not training in research methodology or scientific thinking; it does not prepare an individual for a career in investigation. Although obvious for basic science research, clinical research also requires commitment of a minimum of 1 yr of dedicated training with a good mentor, and more typically 2 - 3 yr in the field of the proposed research. The applicant also needs to demonstrate commitment to a career in investigation. Several years of scientific training is the first demonstration of such commitment. Research proposals must document institutional support for nonclinical time, and the investigator must provide evidence that this time has been used wisely and will continue to be dedicated to the proposed research.

The research proposal must document a track record of productivity by the investigator. This expectation increases as the training and career of the investigator progresses. Fellowship awards do not have an expectation of prior research training, so publications from prior research are not expected. At the fellowship level, outstanding letters of recommendation, undergraduate and medical school performance, and related accomplishments are most important. Because previous training is not required of the fellowship applicant, prior success of the mentor (publications and track record with previous trainees) weighs heavily in the fellowship review. For junior faculty, peer-reviewed publications are expected from the fellowship period. Young Investigator Annoucements (from FAER) and several new IARS awards require several years as a successful junior faculty member, so expectations of demonstrated research success are further increased. The investigator must demonstrate (1) rigorous training, (2) commitment to research, (3) an appropriate career path, and (4) a track record of productive work. None of these are trivial issues, and none can be easily accomplished without making a commitment to research early in the academic career.

The quality of the mentor is another important aspect of awards granted to fellows and junior faculty. Identification of a mentor is explicitly required for FAER and certain junior level NIH grant applications. First and foremost, the mentor must be a successful investigator. Criteria for this include a track record of publication in the area of the proposed research, continued peer-reviewed funding, and a history of successfully training young investigators. Although mentorship is not considered heavily in more senior grant applications, input from a more experienced investigator often remains beneficial throughout one's career (as we can personally attest to). In addition to the mentor, high-quality coinvestigators, collaborators, and consultants also play important roles in strengthening a research proposal.

Environment

Good research is best accomplished in a supportive, cooperative environment. Because of the changing climate of clinical medicine, researchers (both clinical and basic science) face increasing pressure to minimize research time. It is not possible to become a successful investigator in one's spare time. Documentation of adequate nonclinical time for research (not for committee meetings or other unrelated tasks) is essential. Receiving funding at a junior level often enables the department to match funds or to guarantee nonclinical time to the budding investigator. In general, the more non-clinical time available to an investigator, the more competitive the application.

Other important elements of the environment include people, space, and institutional resources. People include mentors, consultants who can help with specific methodologies, statistical support, helpful colleagues, experienced technicians, a clinical research team, and a dedicated chairperson. There must be adequate space for performing the proposed studies, office space for research personnel, and storage space for equipment and supplies. Institutional resources include related departmental and interdepartmental seminar series, a critical mass of investigators in a related area, instrument development and repair shops, and necessary laboratory space and common facilities.

Criteria for a sound research proposal are the same whether the proposal is submitted to NIH, FAER, IARS, or other funding sources. In crafting a proposal, it is essential to consider the perspective of the reviewer; therefore, items of interest to the reviewer are listed after general definition of the grant proposal.

Review committees receive dozens of grants. NIH study sections may review as many as 150 proposals during one session. Typically, only two or three reviewers are assigned to read each grant in detail, but everyone is expected to read each abstract. Hence, the abstract is often one of the most important parts of the research proposal. The abstract should address the significance of the question and the overall topic, state the hypothesis, and point out key preliminary data. Additionally, the abstract should provide a synopsis of methodologies planned. In the end, the reviewer must be convinced that the applicant is uniquely (or ideally) suited to undertake this important study by the end of this concise paragraph.

Body of the Grant

Specific Aims. The specific aims section is critically important in a scientific proposal. It is here that the investigator crystallizes the overall goal of the research and states specific hypotheses.

Beginning with the specific aims, the proposal must be well written and logically organized. A poorly organized grant application is difficult to review, even if the science is otherwise excellent. Typically, the specific aims begin with a short introduction (one paragraph), followed by a formally stated hypothesis. The hypothesis must be answerable by the research methods proposed. Generally, two or three specific aims are outlined with subheadings where appropriate. Organization of the specific aims is often temporal, starting with a proposed mechanism or the first set of studies in a clinical project. In general, the specific aims section should be no longer than one page.

Background and Significance. The background section provides an opportunity to bring reviewers up to date on current research in the area of the proposal. This section should summarize succinctly studies from the literature and related work published by the investigator. The most crucial aspect of the background is to build a case for significance of the proposed research regarding the ultimate clinical application or mechanistic understanding. Ideally, the background section should demonstrate that the current proposal is a logical extension of previous studies in the field and will provide new information and novel insights. In general, the background section should be about one fourth of the length of the grant proposal.

Preliminary Data. Preliminary data provide the opportunity for the investigator to demonstrate his or her ability to perform the proposed research. The goal in presenting preliminary data is to convince the reviewer that the investigator is capable of performing the proposed studies and that the mechanisms proposed are plausible. Good preliminary data support novel (or even unlikely) hypotheses. Each experimental method proposed should be accompanied by preliminary data demonstrating facility and expertise with related preparations. For example, if the investigator proposes using a specific electrophysiologic technique to study an ion channel, evidence demonstrating that this technique has been used by the investigator with other ion channels and a Figure showingresults from pilot experiments on the channel of interest would suffice. In clinical studies, demonstration of a working investigative team and the ability to enroll a given number of patients per week is helpful. Figures or tables help to convey the message in a succinct manner. They also conserve space in the proposal and create a more impressive effect. Although it is best if the applicant has generated his or her own preliminary data, for training awards, preliminary data from the mentor's laboratory is entirely appropriate. An effective way to organize preliminary data is to present it in the same order as the specific aims (e.g., C.1 preliminary data corresponds to A.1 specific aims, C.2 preliminary data corresponds to A.2 specific aims, etc.). Presentation of preliminary data usually takes about one fourth to one third of the length of the grant application.

Methods. The methods are the guts of the research proposal. Unfortunately, many investigators run out of steam by the time they reach the methods, leaving reviewers unconvinced by the proposed methodology. Ideally, the model being investigated should be broken down into simple, logical components, each accompanied by a description of specific experiments/interventions to be performed. The investigator should assume that at least one reviewer is an expert in each method presented. Therefore, enough detail should be provided to convince an expert that the experiment or technique is being performed properly. Methods presented as a list of recipes, requiring the reviewer to guess which method applies to each study, are recipes for disaster. Individual experimental techniques should be state of the art. In addition, approaching a problem from several angles is often helpful. “Lingo” of the field should be avoided; it is very annoying to reviewers to have to look up unexplained abbreviations or to have models alluded to rather than described. For training grants, methods should involve techniques currently being performed in the laboratory of the mentor. An effective way to organize the methods section is to follow the same order as the preliminary data and specific aims sections (e.g., D.1 methods corresponds to C.1 preliminary data and A.1 specific aims, etc.).

The methods sections should include a description of the design, conduct, and analysis of each study being proposed. Common errors in design include lack of specification of primary outcome, lack of randomization or blinding in clinical trials, inadequate justification of sample size, failure to adjust the total study number for expected dropouts/failed experiments or patient refusal, and use of single drug doses or concentrations rather than development of dose - response or concentration - response relations. Common errors in conducting research include lack of confirmation of drug concentrations, inadequate reproducibility of final results, lack of standardization of procedures, inadequate follow-up, incomplete data recording, and overall lack of organization.

Inadequate or inappropriate statistical methods can be a major weakness of a grant proposal. Many investigators feel confident with all aspects of their methods except the statistical section. Because statistical issues underlie the design and analysis strategy for every study, the input of a biostatistician is essential in planning the research and writing the grant application. Statistical considerations include specification of the primary end points that drive power calculations. Common statistical errors in research proposals include lack of sample size/power calculations, treating continuous variables as dichotomous, repeated t tests when a more comprehensive modeling approach should be taken, application of statistical tests that assume normality without verifying assumptions, failure to consider covariate effects, and failure to distinguish between interindividual and intraindividual variability. The investigator should be familiar with the concept of statistical power and be prepared to estimate some of the quantities needed to formulate an alternative hypothesis appropriately. The statistical analysis should be clearly outlined with specific methodology directed toward the hypotheses of the study. A statistical reviewer is unlikely to be convinced by a statement that “appropriate statistical methodology will be used” or by a barrage of nonspecific statistical jargon. At least one full paragraph (and sometimes an entire page) of the research proposal should be devoted to statistical analysis. Often several smaller statistics sections are appropriately included after each method is presented.

Even the best methods have potential problems and weaknesses. It is critical that the methods section discuss potential problems that may be encountered during the study and state how the investigator proposes to deal with these problems creatively. Reviewers tend to be impressed when the investigator presents potential problems that never occurred to them, because it suggests that the investigator is an expert in this area of research. A time line and organizational plan (who will be responsible for what) should also be included in the methods section so the reviewers can determine whether the investigator is being realistic in his or her approach. The methods section is typically one third to one half of the length of the entire grant proposal.

Introduction to Revised Application. Because so few grant applications are funded on their first submission (11.5% in 1993), the new investigator should not be unduly alarmed if his or her application is not funded. When a grant application has been unsuccessful, an investigator should revise the application and reapply, even if the original score was “noncompetitive”(meaning the grant was in the lower 50% of applications). Often the reviewers suggest key changes that will improve the application significantly. When submitting a revised application, an introduction (placed before the specific aims section) is used to discuss how criticisms of the original grant have been addressed in the revised proposal. Because the reviewer's comments are intended to be helpful, it is important to address each concern carefully in the revised proposal (changed text should be highlighted in the revised application by italic, bold, or identifying lines in the margin), with changes outlined in the introduction section. Angry responses to reviewers do not facilitate funding of the revised application. Remember that reviewers usually have a copy of the prior review, and they expect corrections or, when appropriate, an explanation of why you have chosen not to incorporate some suggestions from a prior review. Time taken to revise an application is well spent; as Figure 1 demonstrates, investigators who persist in revising and resubmitting their applications have an increased chance ([almost equal to] 20% with no previous NIH support, [almost equal to] 35% if previously funded) of ultimately being funded.[section]

In writing a research grant, it is helpful to consider the reviewer's perspective. Key features considered by reviewers include significance, approach, and feasibility. It is wise for the investigator to reread his or her application before submission with these features in mind. The NIH recently has published two documents on-line that discuss review criteria; examination of these documents before submission of a research proposal may prove helpful. These include the Report of the Committee on Rating Grant Applications[double vertical bar] and Review Criteria for Rating Unsolicited Research Grants.#

Significance

First and foremost, is the investigator asking an important question? There are two general ways research studies can be significant. The first is to demonstrate clinical significance. The litmus test for clinical significance is whether the proposed research will improve patient care. The second is elucidation of fundamental mechanisms underlying disease or biologic processes. The ideal research question succeeds in being significant in both areas.

The reviewer assesses whether the research plan can support or refute the stated hypothesis. In addition, the reviewer assesses whether the methodologies used provide adequate or, better yet, elegant approaches to the problem. Recently, the NIH has mandated an increasing emphasis on innovation in research. [1] **

Review committees generally are composed of individuals with expertise in many scientific areas. Additionally, study sections often retain outside reviewers with expertise in the proposed research area. The investigator should assume that his or her methods will be critiqued by at least one expert. Therefore, the investigator should not propose a method that would strike the world's expert in the field as being simplistic, inappropriate, or nonsensical, because the world's expert just might be one of the reviewers. Conversely, some reviewers do not have expertise in the proposed area of research. To ensure that the nonexpert is convinced of the validity and importance of proposed methodologies, the overall proposal should be written with a logical flow of ideas that build from basic to sophisticated concepts. Beginning each portion of the methods section with a short introduction for the nonexpert, followed by a more detailed description of the proposed methods, is an effective strategy to address the needs of both expert and nonexpert reviewers.

Feasibility

The investigator must convince reviewers that the chosen approach is feasible. Preliminary data provide the best demonstration of feasibility. Feasibility is often demonstrated by a track record of publications or peer-reviewed grant support for the applicant or mentor using the proposed experimental approach. Feasibility also can be demonstrated by appropriate statistical analysis of the proposal. For example, a power analysis and corresponding data on the number of patients with the required characteristics at the investigator's institution helps convince reviewers that a clinical study is feasible.

Anesthesiology Funding Sources

Funding for research performed by anesthesiologists is available from many sources. Because the discipline of anesthesiology overlaps many other fields, anesthesiologists have the opportunity to apply for research funds from agencies as diverse as the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, American Heart Association (national and local), American Thoracic Society, American Society for Regional Anesthesiology, critical care societies, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Science Foundation, Shriners, Society for Cardiovascular Anesthesiology, Society for Obstetrics and Perinatology, National Aeronautics and Space Aviation, NIH, and many other private foundations. Grants from FAER and IARS are available specifically to the anesthesiology community.

It is important that anesthesiologists continue to apply for NIH grants. For fiscal year 1996, the NIH awarded 149 research grants (including career development grants, R29, R01, and program project grants) to departments of anesthesiology, totaling $21 million in direct costs ([almost equal to]$31 million in total costs). Because of the diversity of research projects in anesthesiology, these grants were awarded by 14 different institutes, centers, and divisions within the NIH. In analyzing data for three recent review sessions (June 1996, October 1996, and February 1997) from the surgery, anesthesiology, and trauma study section, 26% of anesthesiology applications scored in the top 20th percentile, and 31% scored in the top 25th percentile; clearly no bias exists against anesthesiology in this predominantly surgical study section, at least in this limited sample (Alison Cole, anesthesiology representative for the National Institute of General Medicine Science at the NIH, personal communication, December, 1997). Table 1

Table 1. Number of Recipients of NIH Research Project Annoucements

A brief list of funding opportunities available to anesthesiologists early in their career is shown in Table 2 . Several sites are available on the World Wide Web ( Table 3 ) to facilitate access to grant/training resources for anesthesiologists. We have created an additional website ( http://pkpd.icon.palo-alto.med.va.gov/grants/grants.htm ), which provides access to more comprehensive lists of funding agencies and direct links to funding sources. This website also contains example grants designed to illustrate the grant writing principles discussed in this article.

Table 2. Potential Funding Sources

Table 3. Grant/Training Resources on the WWW

Successful grant applications require a well-trained investigator who carefully outlines a hypothesis-driven research proposal. Unique to FAER and IARS research committees is that the reviewers are mostly investigators and practicing anesthesiologists. These reviewers fully appreciate the importance of clinical research and enthusiastically support high-quality clinical studies. Although descriptive clinical studies are interesting to practicing clinicians, from a scientific perspective, clinical research must be driven by testable hypotheses. Without a testable hypothesis, clinical research cannot pass the test of adequate significance required for funding.

It is our hope that by demystifying the grant writing and review process that more anesthesiologists will be encouraged to submit proposals for research funding. As part of this effort, we strongly encourage residents and fellows interested in research careers to obtain adequate research training and to apply for appropriate fellowship/junior faculty awards early in their careers.

[section] NIH Extramural Data and Trends, Fiscal Years 1986 - 1995. Bethesda, Office of Reports and Analysis (component of the Office of Extramural Research), National Institutes of Health. (Published on-line and periodically updated. http://www.nih.gov/grants/award/award.htm ).

[double vertical bar] Report of the Committee on Rating Grant Applications. Revised 5/17/96. Bethesda, National Institutes of Health. (Published on-line. http://www.nih.gov/grants/peer/rga.pdf ).

# Review Criteria for Rating Unsolicited Research Grants. NIH Guide, Vol. 26, No. 22, 6/27/97. Bethesda, National Institutes of Health. (Published on-line. http://www.nih.gov/grants/guide/1997/97.06.27/notice-review-criter9.html ).

** Brown KS: A winning strategy for grant application: Focus on impact. The Scientist 1997; April 8:13–4

Citing articles via

Most viewed, email alerts, related articles, social media, affiliations.

- ASA Practice Parameters

- Online First

- Author Resource Center

- About the Journal

- Editorial Board

- Rights & Permissions

- Online ISSN 1528-1175

- Print ISSN 0003-3022

- Anesthesiology

- ASA Monitor

- Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- © Copyright 2024 American Society of Anesthesiologists

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

87Chapter 4 Writing your research proposal

- Published: November 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In many ways it’s a reflection of yourself as a researcher and an insight into your proposed work. A poorly written proposal has the ability to wreck a project and embarrass the researcher before it has even begun. Similarly, a well-constructed proposal bodes well for the success of the project and displays the researcher in a good light amongst their peers and supervisors. The research proposal identifies: • What the topic is, both in terms of background and the individual area of interest. • What you plan to accomplish and why it needs doing. • What in particular you are trying to find out, i.e. the research question. • How you will get the answer to your question, i.e. your methodology. • What others will learn from it and why it is worth learning. • How long it will take. • How much money it will cost. Through your research proposal you are attempting to convince potential supporters that your project is worth doing, you are scientifically competent to run it, and are in possession of the necessary management skills to ensure its completion. The proposal concisely describes the key elements of the study process, although in sufficient depth to permit evaluation. It is a stand-alone document that must contain evidence of an answerable question, demonstrate your grasp of the literature, and also clearly show that your methodology is sound. A research time-table is required to demonstrate a realistic appreciation of how the study will progress through time. The research proposal serves many purposes to many different parties. Amongst these purposes, some of the key ones are: • Acting as a route map and timetable for all involved in your project. • Giving a clear overview of your planned work to ensure favourable decision at ethical review. • Gaining funding to carry out your proposed study. • Securing a place to undertake a higher scientific degree. • Being an opportunity to ‘blow your own trumpet’ on paper. Although there are several bodies who will be obliged to see your proposal, there is a reasonable chance it will end up being wider read than this, so a coherent piece of work will reflect well on you.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 32: Writing a Research Proposal

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Introduction.

- COMPONENTS OF THE RESEARCH PLAN

- PLAN FOR ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT

- PRESENTATION OF THE PROPOSAL

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

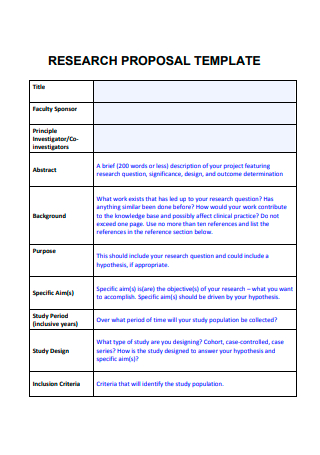

The initial stages of the research process include development of the research question and delineation of methods of data collection. The success of the project depends on how well these elements have been developed and defined in advance, so that the proper resources are gathered and methods proceed with reliability and validity. The plan that describes all these preparatory elements is the research proposal . The proposal describes the purpose of the study, the importance of the research question, the research protocol and justifies the feasibility of the project.

The proposal can serve several purposes. First, it represents the synthesis of the researcher's critical thinking and the scientific literature to ensure that the research question is refined enough to be studied, that the assumptions and theoretical rationale on which the study is based are logical and that the method is appropriate for answering the question. Second, the well prepared proposal may constitute the body of a grant application when external funding is required. Third, it is part of an application for review by peer or administrative committees. This is the document that will be carefully scrutinized by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) (see Chapter 3 ). Fourth, the proposal enhances communication among colleagues who may be co-investigators and with consultants whose advice may be needed. Finally, the careful, detailed account of the study procedures serves as a guide throughout the data collection phase to ensure that the researchers follow the outlined rules of conduct. The research proposal, therefore, is an indispensable instrument in initiating and implementing a project.

When proposals are written as part of a grant application for funding from foundations or government agencies, the researcher must obtain the guidelines of the agency to which the proposal will be submitted. Generally, requirements and components of a proposal will be the same for grant applications as they are for academic and clinical institutions; however, to write a successful grant application, the researcher must understand the interests of the funding agency, the extent of available funds, the deadlines for submitting proposals, and the proper format of the application. ∗

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the process of developing and writing a research proposal. The exact format of the proposal will depend on the requirements or instructions of the individuals, clinics, faculty or agencies that will review the project. The order of presentation of material may vary, as may the extent of the information required. The following guidelines are meant to reflect the most common elements of a proposal. A research proposal has two basic parts, as shown in Table 32.1 . The first part provides details of the research plan, and the other describes the administrative and personnel support required to carry out the project.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Research Development and Proposal Writing

The Division of Cardiovascular Medicine Strategic Research Development team actively supports our clinical fellows, postdoctoral fellows, and junior faculty in project development & proposal writing.

Priorities include:

- Diversity Supplements (all career stages)

- Fellowships (clinical fellows and postdocs)

- First major research grant (junior faculty)

- Select large program projects (all career stages*)

Services Include:

- Identifying funding opportunities

- Editing and critically evaluating proposals

- Interpreting sponsor requirements and providing strategic advice

- Drafting specific administrative sections of the application

- Assisting with pre-award budgeting, progress reports, and other supports

- Coordinating completion of proposals, subcontracts, and select large collaborative projects

- Providing educational resources, workshops, and one-on-one consultations

Our model of 1:1 grant support is designed to enable the PI to focus on the science:

- Recurring meetings to discuss progress, review drafts, and strategize

- Project management, including checklists and timelines

- Shared collaborative folders containing comprehensive educational resources and templates

- Mock reviews scheduled as needed

Individuals submitting fellowships and career development awards are highly encouraged to register for and complete the Grant Writing Academy's Proposal Bootcamp as they prepare their submissions. Sign up here: https://grantwriting.stanford.edu/online-proposal-bootcamp/

Subcontracts may receive limited project management support (coordinating with RMG, a first draft of the budget justification based on the budget, and help gathering required documents).

*Larger grants (i.e. program project grants) are a very time-sensitive endeavor. Support for these will continue to be on a very limited basis and must be approved by division leadership.

Support is only available for proposals in which the PI is submitting through the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine.

Deadline to request support: