- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2021

Financial technology and the future of banking

- Daniel Broby ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5482-0766 1

Financial Innovation volume 7 , Article number: 47 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

52 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper presents an analytical framework that describes the business model of banks. It draws on the classical theory of banking and the literature on digital transformation. It provides an explanation for existing trends and, by extending the theory of the banking firm, it illustrates how financial intermediation will be impacted by innovative financial technology applications. It further reviews the options that established banks will have to consider in order to mitigate the threat to their profitability. Deposit taking and lending are considered in the context of the challenge made from shadow banking and the all-digital banks. The paper contributes to an understanding of the future of banking, providing a framework for scholarly empirical investigation. In the discussion, four possible strategies are proposed for market participants, (1) customer retention, (2) customer acquisition, (3) banking as a service and (4) social media payment platforms. It is concluded that, in an increasingly digital world, trust will remain at the core of banking. That said, liquidity transformation will still have an important role to play. The nature of banking and financial services, however, will change dramatically.

Introduction

The bank of the future will have several different manifestations. This paper extends theory to explain the impact of financial technology and the Internet on the nature of banking. It provides an analytical framework for academic investigation, highlighting the trends that are shaping scholarly research into these dynamics. To do this, it re-examines the nature of financial intermediation and transactions. It explains how digital banking will be structurally, as well as physically, different from the banks described in the literature to date. It does this by extending the contribution of Klein ( 1971 ), on the theory of the banking firm. It presents suggested strategies for incumbent, and challenger banks, and how banking as a service and social media payment will reshape the competitive landscape.

The banking industry has been evolving since Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena opened its doors in 1472. Its leveraged business model has proved very scalable over time, but it is now facing new challenges. Firstly, its book to capital ratios, as documented by Berger et al ( 1995 ), have been consistently falling since 1840. This trend continues as competition has increased. In the past decade, the industry has experienced declines in profitability as measured by return on tangible equity. This is partly the result of falling leverage and fee income and partly due to the net interest margin (connected to traditional lending activity). These trends accelerated following the 2008 financial crisis. At the same time, technology has made banks more competitive. Advances in digital technology are changing the very nature of banking. Banks are now distributing services via mobile technology. A prolonged period of very low interest rates is also having an impact. To sustain their profitability, Brei et al. ( 2020 ) note that many banks have increased their emphasis on fee-generating services.

As Fama ( 1980 ) explains, a bank is an intermediary. The Internet is, however, changing the way financial service providers conduct their role. It is fundamentally changing the nature of the banking. This in turn is changing the nature of banking services, and the way those services are delivered. As a consequence, in order to compete in the changing digital landscape, banks have to adapt. The banks of the future, both incumbents and challengers, need to address liquidity transformation, data, trust, competition, and the digitalization of financial services. Against this backdrop, incumbent banks are focused on reinventing themselves. The challenger banks are, however, starting with a blank canvas. The research questions that these dynamics pose need to be investigated within the context of the theory of banking, hence the need to revise the existing analytical framework.

Banks perform payment and transfer functions for an economy. The Internet can now facilitate and even perform these functions. It is changing the way that transactions are recorded on ledgers and is facilitating both public and private digital currencies. In the past, banks operated in a world of information asymmetry between themselves and their borrowers (clients), but this is changing. This differential gave one bank an advantage over another due to its knowledge about its clients. The digital transformation that financial technology brings reduces this advantage, as this information can be digitally analyzed.

Even the nature of deposits is being transformed. Banks in the future will have to accept deposits and process transactions made in digital form, either Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) or cryptocurrencies. This presents a number of issues: (1) it changes the way financial services will be delivered, (2) it requires a discussion on resilience, security and competition in payments, (3) it provides a building block for better cross border money transfers and (4) it raises the question of private and public issuance of money. Braggion et al ( 2018 ) consider whether these represent a threat to financial stability.

The academic study of banking began with Edgeworth ( 1888 ). He postulated that it is based on probability. In this respect, the nature of the business model depends on the probability that a bank will not be called upon to meet all its liabilities at the same time. This allows banks to lend more than they have in deposits. Because of the resultant mismatch between long term assets and short-term liabilities, a bank’s capital structure is very sensitive to liquidity trade-offs. This is explained by Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ). They explain that this makes a bank a’relationship lender’. In effect, they suggest a bank is an intermediary that has borrowed from other investors.

Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ) argue a lender can negotiate repayment obligations and that a bank benefits from its knowledge of the customer. As shall be shown, the new generation of digital challenger banks do not have the same tradeoffs or knowledge of the customer. They operate more like a broker providing a platform for banking services. This suggests that there will be more than one type of bank in the future and several different payment protocols. It also suggests that banks will have to data mine customer information to improve their understanding of a client’s financial needs.

The key focus of Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ), however, was to position a traditional bank is an intermediary. Gurley and Shaw ( 1956 ) describe how the customer relationship means a bank can borrow funds by way of deposits (liabilities) and subsequently use them to lend or invest (assets). In facilitating this mediation, they provide a service whereby they store money and provide a mechanism to transmit money. With improvements in financial technology, however, money can be stored digitally, lenders and investors can source funds directly over the internet, and money transfer can be done digitally.

A review of financial technology and banking literature is provided by Thakor ( 2020 ). He highlights that financial service companies are now being provided by non-deposit taking contenders. This paper addresses one of the four research questions raised by his review, namely how theories of financial intermediation can be modified to accommodate banks, shadow banks, and non-intermediated solutions.

To be a bank, an entity must be authorized to accept retail deposits. A challenger bank is, therefore, still a bank in the traditional sense. It does not, however, have the costs of a branch network. A peer-to-peer lender, meanwhile, does not have a deposit base and therefore acts more like a broker. This leads to the issue that this paper addresses, namely how the banks of the future will conduct their intermediation.

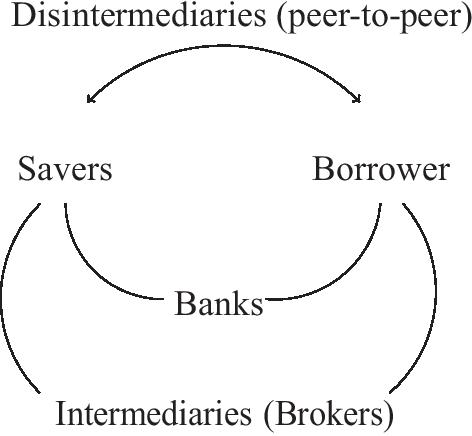

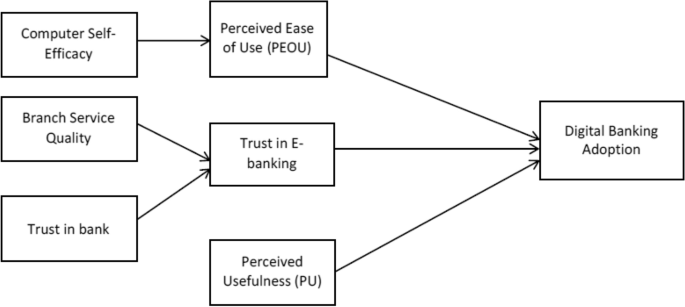

In order to understand what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the nature of the aforementioned intermediation, and the way it is changing. In this respect, there are two key types of intermediation. These are (1) quantitative asset transformation and, (2) brokerage. The latter is a common model adopted by challenger banks. Figure 1 depicts how these two types of financial intermediation match savers with borrowers. To avoid nuanced distinction between these two types of intermediation, it is common to classify banks by the services they perform. These can be grouped as either private, investment, or commercial banking. The service sub-groupings include payments, settlements, fund management, trading, treasury management, brokerage, and other agency services.

How banks act as intermediaries between lenders and borrowers. This function call also be conducted by intermediaries as brokers, for example by shadow banks. Disintermediation occurs over the internet where peer-to-peer lenders match savers to lenders

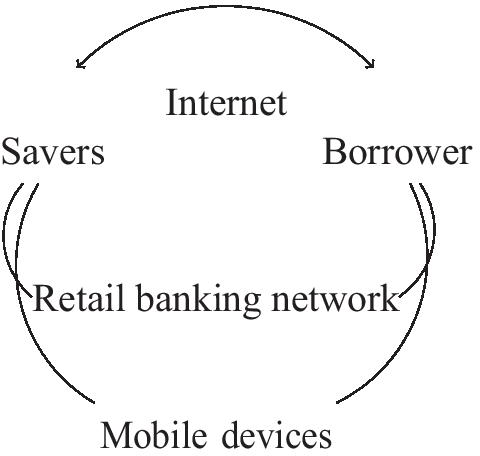

Financial technology has the ability to disintermediate the banking sector. The competitive pressures this results in will shape the banks of the future. The channels that will facilitate this are shown in Fig. 2 , namely the Internet and/or mobile devices. Challengers can participate in this by, (1) directly matching borrows with savers over the Internet and, (2) distributing white labels products. The later enables banking as a service and avoids the aforementioned liquidity mismatch.

The strategic options banks have to match lenders with borrowers. The traditional and challenger banks are in the same space, competing for business. The distributed banks use the traditional and challenger banks to white label banking services. These banks compete with payment platforms on social media. The Internet heralds an era of banking as a service

There are also physical changes that are being made in the delivery of services. Bricks and mortar branches are in decline. Mobile banking, or m-banking as Liu et al ( 2020 ) describe it, is an increasingly important distribution channel. Robotics are increasingly being used to automate customer interaction. As explained by Vishnu et al ( 2017 ), these improve efficiency and the quality of execution. They allow for increased oversight and can be built on legacy systems as well as from a blank canvas. Application programming interfaces (APIs) are bringing the same type of functionality to m-banking. They can be used to authorize third party use of banking data. How banks evolve over time is important because, according to the OECD, the activity in the financial sector represents between 20 and 30 percent of developed countries Gross Domestic Product.

In summary, financial technology has evolved to a level where online banks and banking as a service are challenging incumbents and the nature of banking mediation. Banking is rapidly transforming because of changes in such technology. At the same time, the solving of the double spending problem, whereby digital money can be cryptographically protected, has led to the possibility that paper money will become redundant at some point in the future. A theoretical framework is required to understand this evolving landscape. This is discussed next.

The theory of the banking firm: a revision

In financial theory, as eloquently explained by Fama ( 1980 ), banking provides an accounting system for transactions and a portfolio system for the storage of assets. That will not change for the banks of the future. Fama ( 1980 ) explains that their activities, in an unregulated state, fulfil the Modigliani–Miller ( 1959 ) theorem of the irrelevance of the financing decision. In practice, traditional banks compete for deposits through the interest rate they offer. This makes the transactional element dependent on the resulting debits and credits that they process, essentially making banks into bookkeeping entities fulfilling the intermediation function. Since this is done in response to competitive forces, the general equilibrium is a passive one. As such, the banking business model is vulnerable to disruption, particularly by innovation in financial technology.

A bank is an idiosyncratic corporate entity due to its ability to generate credit by leveraging its balance sheet. That balance sheet has assets on one side and liabilities on the other, like any corporate entity. The assets consist of cash, lending, financial and fixed assets. On the other side of the balance sheet are its liabilities, deposits, and debt. In this respect, a bank’s equity and its liabilities are its source of funds, and its assets are its use of funds. This is explained by Klein ( 1971 ), who notes that a bank’s equity W , borrowed funds and its deposits B is equal to its total funds F . This is the same for incumbents and challengers. This can be depicted algebraically if we let incumbents be represented by Φ and challengers represented by Γ:

Klein ( 1971 ) further explains that a bank’s equity is therefore made up of its share capital and unimpaired reserves. The latter are held by a bank to protect the bank’s deposit clients. This part is also mandated by regulation, so as to protect customers and indeed the entire banking system from systemic failure. These protective measures include other prudential requirements to hold cash reserves or other liquid assets. As shall be shown, banking services can be performed over the Internet without these protections. Banking as a service, as this phenomenon known, is expected to increase in the future. This will change the nature of the protection available to clients. It will change the way banks transform assets, explained next.

A bank’s deposits are said to be a function of the proportion of total funds obtained through the issuance of the ith deposit type and its total funds F , represented by α i . Where deposits, represented by Bs , are made in the form of Bs (i = 1 *s n) , they generate a rate of interest. It follows that Si Bs = B . As such,

Therefor it can be said that,

The importance of Eq. 3 is that the balance sheet can be leveraged by the issuance of loans. It should be noted, however, that not all loans are returned to the bank in whole or part. Non-performing loans reduce the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet and act as a constraint on capital, and therefore new lending. Clearly, this is not the case with banking as a service. In that model, loans are brokered. That said, with the traditional model, an advantage of financial technology is that it facilitates the data mining of clients’ accounts. Lending can therefore be more targeted to borrowers that are more likely to repay, thereby reducing non-performing loans. Pari passu, the incumbent bank of the future will therefore have a higher risk-adjusted return on capital. In practice, however, banking as a service will bring greater competition from challengers and possible further erosion of margins. Alternatively, some banks will proactively engage in partnerships and acquisitions to maintain their customer base and address the competition.

A bank must have reserves to meet the demand of customers demanding their deposits back. The amount of these reserves is a key function of banking regulation. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision mandates a requirement to hold various tiers of capital, so that banks have sufficient reserves to protect depositors. The Committee also imposes a framework for mitigating excessive liquidity risk and maturity transformation, through a set Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio.

Recent revisions of theory, because of financial technology advances, have altered our understanding of banking intermediation. This will impact the competitive landscape and therefor shape the nature of the bank of the future. In this respect, the threat to incumbent banks comes from peer-to-peer Internet lending platforms. These perform the brokerage function of financial intermediation without the use of the aforementioned banking balance sheet. Unlike regulated deposit takers, such lending platforms do not create assets and do not perform risk and asset transformation. That said, they are reliant on investors who do not always behave in a counter cyclical way.

Financial technology in banking is not new. It has been used to facilitate electronic markets since the 1980’s. Thakor ( 2020 ) refers to three waves of application of financial innovation in banking. The advent of institutional futures markets and the changing nature of financial contracts fundamentally changed the role of banks. In response to this, academics extended the concept of a bank into an entity that either fulfills the aforementioned functions of a broker or a qualitative asset transformer. In this respect, they connect the providers and users of capital without changing the nature of the transformation of the various claims to that capital. This transformation can be in the form risk transfer or the application of leverage. The nature of trading of financial assets, however, is changing. Price discovery can now be done over the Internet and that is moving liquidity from central marketplaces (like the stock exchange) to decentralized ones.

Alongside these trends, in considering what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the unregulated lending market that competes with traditional banks. In this part of the lending market, there has been a rise in shadow banks. The literature on these entities is covered by Adrian and Ashcraft ( 2016 ). Shadow banks have taken substantial market share from the traditional banks. They fulfil the brokerage function of banks, but regulators have only partial oversight of their risk transformation or leverage. The rise of shadow banks has been facilitated by financial technology and the originate to distribute model documented by Bord and Santos ( 2012 ). They use alternative trading systems that function as electronic communication networks. These facilitate dark pools of liquidity whereby buyers and sellers of bonds and securities trade off-exchange. Since the credit crisis of 2008, total broker dealer assets have diverged from banking assets. This illustrates the changed lending environment.

In the disintermediated market, banking as a service providers must rely on their equity and what access to funding they can attract from their online network. Without this they are unable to drive lending growth. To explain this, let I represent the online network. Extending Klein ( 1971 ), further let Ψ represent banking as a service and their total funds by F . This state is depicted as,

Theoretically, it can be shown that,

Shadow banks, and those disintermediators who bypass the banking system, have an advantage in a world where technology is ubiquitous. This becomes more apparent when costs are considered. Buchak et al. ( 2018 ) point out that shadow banks finance their originations almost entirely through securitization and what they term the originate to distribute business model. Diversifying risk in this way is good for individual banks, as banking risks can be transferred away from traditional banking balance sheets to institutional balance sheets. That said, the rise of securitization has introduced systemic risk into the banking sector.

Thus, we can see that the nature of banking capital is changing and at the same time technology is replacing labor. Let A denote the number of transactions per account at a period in time, and C denote the total cost per account per time period of providing the services of the payment mechanism. Klein ( 1971 ) points out that, if capital and labor are assumed to be part of the traditional banking model, it can be observed that,

It can therefore be observed that the total service charge per account at a period in time, represented by S, has a linear and proportional relationship to bank account activity. This is another variable that financial technology can impact. According to Klein ( 1971 ) this can be summed up in the following way,

where d is the basic bank decision variable, the service charge per transaction. Once again, in an automated and digital environment, financial technology greatly reduces d for the challenger banks. Swankie and Broby ( 2019 ) examine the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the evaluation of banking risk and conclude that it improves such variables.

Meanwhile, the traditional banking model can be expressed as a product of the number of accounts, M , and the average size of an account, N . This suggests a banks implicit yield is it rate of interest on deposits adjusted by its operating loss in each time period. This yield is generated by payment and loan services. Let R 1 depict this. These can be expressed as a fraction of total demand deposits. This is depicted by Klein ( 1971 ), if one assumes activity per account is constant, as,

As a result, whether a bank is structured with traditional labor overheads or built digitally, is extremely relevant to its profitability. The capital and labor of tradition banks, depicted as Φ i , is greater than online networks, depicted as I i . As such, the later have an advantage. This can be shown as,

What Klein (1972) failed to highlight is that the banking inherently involves leverage. Diamond and Dybving (1983) show that leverage makes bank susceptible to run on their liquidity. The literature divides these between adverse shock events, as explained by Bernanke et al ( 1996 ) or moral hazard events as explained by Demirgu¨¸c-Kunt and Detragiache ( 2002 ). This leverage builds on the balance sheet mismatch of short-term assets with long term liabilities. As such, capital and liquidity are intrinsically linked to viability and solvency.

The way capital and liquidity are managed is through credit and default management. This is done at a bank level and a supervisory level. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision applies capital and leverage ratios, and central banks manage interest rates and other counter-cyclical measures. The various iterations of the prudential regulation of banks have moved the microeconomic theory of banking from the modeling of risk to the modeling of imperfect information. As mentioned, shadow and disintermediated services do not fall under this form or prudential regulation.

The relationship between leverage and insolvency risk crucially depends on the degree of banks total funds F and their liability structure L . In this respect, the liability structure of traditional banks is also greater than online networks which do not have the same level of available funds, depicted as,

Diamond and Dybvig ( 1983 ) observe that this liability structure is intimately tied to a traditional bank’s assets. In this respect, a bank’s ability to finance its lending at low cost and its ability to achieve repayment are key to its avoidance of insolvency. Online networks and/or brokers do not have to finance their lending, simply source it. Similarly, as brokers they do not face capital loss in the event of a default. This disintermediates the bank through the use of a peer-to-peer environment. These lenders and borrowers are introduced in digital way over the internet. Regulators have taken notice and the digital broker advantage might not last forever. As a result, the future may well see greater cooperation between these competing parties. This also because banks have valuable operational experience compared to new entrants.

It should also be observed that bank lending is either secured or unsecured. Interest on an unsecured loan is typically higher than the interest on a secured loan. In this respect, incumbent banks have an advantage as their closeness to the customer allows them to better understand the security of the assets. Berger et al ( 2005 ) further differentiate lending into transaction lending, relationship lending and credit scoring.

The evolution of the business model in a digital world

As has been demonstrated, the bank of the future in its various manifestations will be a consequence of the evolution of the current banking business model. There has been considerable scholarly investigation into the uniqueness of this business model, but less so on its changing nature. Song and Thakor ( 2010 ) are helpful in this respect and suggest that there are three aspects to this evolution, namely competition, complementary and co-evolution. Although liquidity transformation is evolving, it remains central to a bank’s role.

All the dynamics mentioned are relevant to the economy. There is considerable evidence, as outlined by Levine ( 2001 ), that market liberalization has a causal impact on economic growth. The impact of technology on productivity should prove positive and enhance the functioning of the domestic financial system. Indeed, market liberalization has already reshaped banking by increasing competition. New fee based ancillary financial services have become widespread, as has the proprietorial use of balance sheets. Risk has been securitized and even packaged into trade-able products.

Challenger banks are developing in a complementary way with the incumbents. The latter have an advantage over new entrants because they have information on their customers. The liquidity insurance model, proposed by Diamond and Dybvig ( 1983 ), explains how such banks have informational advantages over exchange markets. That said, financial technology changes these dynamics. It if facilitating the processing of financial data by third parties, explained in greater detail in the section on Open Banking.

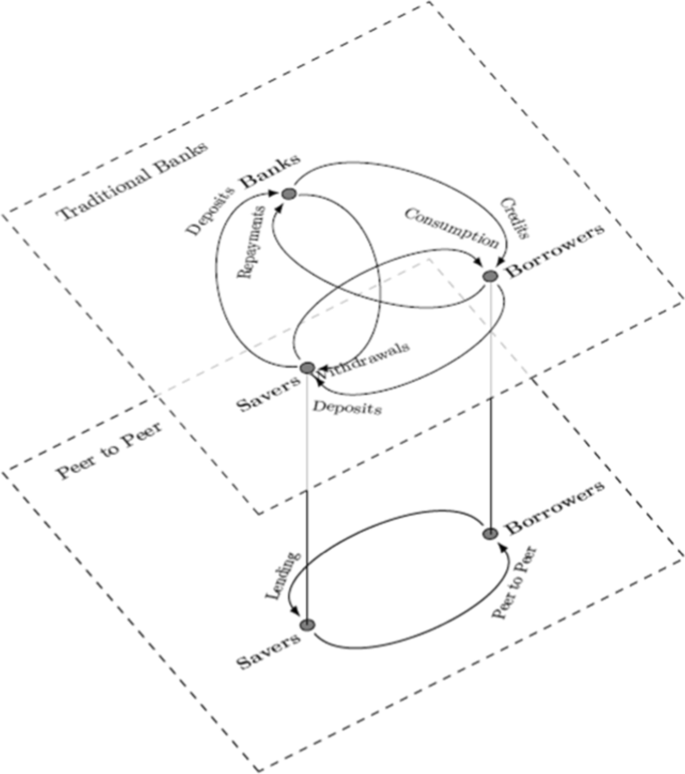

At the same time, financial technology is facilitating banking as a service. This is where financial services are delivered by a broker over the Internet without resort to the balance sheet. This includes roboadvisory asset management, peer to peer lending, and crowd funding. Its growth will be facilitated by Open Banking as it becomes more geographically adopted. Figure 3 illustrates how these business models are disintermediating the traditional banking role and matching burrowers and savers.

The traditional view of banks ecosystem between savers and borrowers, atop the Internet which is matching savers and borrowers directly in a peer-to-peer way. The Klein ( 1971 ) theory of the banking firm does not incorporate the mirrored dynamics, and as such needs to be extended to reflect the digital innovation that impacts both borrowers and severs in a peer-to-peer environment

Meanwhile, the banking sector is co-evolving alongside a shadow banking phenomenon. Lenders and borrowers are interacting, but outside of the banking sector. This is a concern for central banks and banking regulators, as the lending is taking place in an unregulated environment. Shadow banking has grown because of financial technology, market liberalization and excess liquidity in the asset management ecosystem. Pozsar and Singh ( 2011 ) detail the non-bank/bank intersection of shadow banking. They point out that shadow banking results in reverse maturity transformation. Incumbent banks have blurred the distinction between their use of traditional (M2) liabilities and market-based shadow banking (non-M2) liabilities. This impacts the inter-generational transfers that enable a bank to achieve interest rate smoothing.

Securitization has transformed the risk in the banking sector, transferring it to asset management institutions. These include structured investment vehicles, securities lenders, asset backed commercial paper investors, credit focused hedge and money market funds. This in turn has led to greater systemic risk, the result of the nature of the non-traded liabilities of securitized pooling arrangements. This increased risk manifested itself in the 2008 credit crisis.

Commercial pressures are also shaping the banking industry. The drive for cost efficiency has made incumbent banks address their personally costs. Bank branches have been closed as technology has evolved. Branches make it easier to withdraw or transfer deposits and challenger banks are not as easily able to attract new deposits. The banking sector is therefore looking for new point of customer contact, such as supermarkets, post offices and social media platforms. These structural issues are occurring at the same time as the retail high street is also evolving. Banks have had an aggressive roll out of automated telling machines and a reduction in branches and headcount. Online digital transactions have now become the norm in most developed countries.

The financing of banks is also evolving. Traditional banks have tended to fund illiquid assets with short term and unstable liquid liabilities. This is one of the key contributors to the rise to the credit crisis of 2008. The provision of liquidity as a last resort is central to the asset transformation process. In this respect, the banking sector experienced a shock in 2008 in what is termed the credit crisis. The aforementioned liquidity mismatch resulted in the system not being able to absorb all the risks associated with subprime lending. Central banks had to resort to quantitative easing as a result of the failure of overnight funding mechanisms. The image of the entire banking sector was tarnished, and the banks of the future will have to address this.

The future must learn from the mistakes of the past. The structural weakness of the banking business model cannot be solved. That said, the latest Basel rules introduce further risk mitigation, improved leverage ratios and increased levels of capital reserve. Another lesson of the credit crisis was that there should be greater emphasis on risk culture, governance, and oversight. The independence and performance of the board, the experience and the skill set of senior management are now a greater focus of regulators. Internal controls and data analysis are increasingly more robust and efficient, with a greater focus on a banks stable funding ratio.

Meanwhile, the very nature of money is changing. A digital wallet for crypto-currencies fulfills much the same storage and transmission functions of a bank; and crypto-currencies are increasing being used for payment. Meanwhile, in Sweden, stores have the right to refuse cash and the majority of transactions are card based. This move to credit and debit cards, and the solving of the double spending problem, whereby digital money can be crypto-graphically protected, has led to the possibility that paper money could be replaced at some point in the future. Whether this might be by replacement by a CBDC, or decentralized digital offering, is of secondary importance to the requirement of banks to adapt. Whether accommodating crytpo-currencies or CBDC’s, Kou et al. ( 2021 ) recommend that banks keep focused on alternative payment and money transferring technologies.

Central banks also have to adapt. To limit disintermediation, they have to ensure that the economic design of their sponsored digital currencies focus on access for banks, interest payment relative to bank policy rate, banking holding limits and convertibility with bank deposits. All these developments have implications for banks, particularly in respect of funding, the secure storage of deposits and how digital currency interacts with traditional fiat money.

Open banking

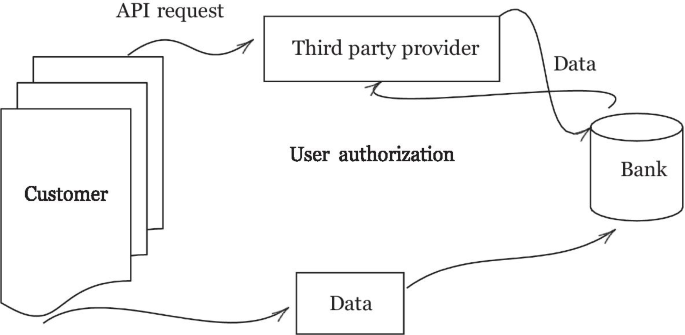

Against the backdrop of all these trends and changes, a new dynamic is shaping the future of the banking sector. This is termed Open Banking, already briefly mentioned. This new way of handling banking data protocols introduces a secure way to give financial service companies consensual access to a bank’s customer financial information. Figure 4 illustrates how this works. Although a fairly simple concept, the implications are important for the banking industry. Essentially, a bank customer gives a regulated API permission to securely access his/her banking website. That is then used by a banking as a service entity to make direct payments and/or download financial data in order to provide a solution. It heralds an era of customer centric banking.

How Open Banking operates. The customer generates data by using his bank account. A third party provider is authorized to access that data through an API request. The bank confirms digitally that the customer has authorized the exchange of data and then fulfills the request

Open Banking was a response to the documented inertia around individual’s willingness to change bank accounts. Following the Retail Banking Review in the UK, this was addressed by lawmakers through the European Union’s Payment Services Directive II. The legislation was designed to make it easier to change banks by allowing customers to delegate authority to transfer their financial data to other parties. As a result of this, a whole host of data centric applications were conceived. Open banking adds further momentum to reshaping the future of banking.

Open Banking has a number of quite revolutionary implications. It was started so customers could change banks easily, but it resulted in some secondary considerations which are going to change the future of banking itself. It gives a clear view of bank financing. It allows aggregation of finances in one place. It also allows can give access to attractive offerings by allowing price comparisons. Open Banking API’s build a secure online financial marketplace based on data. They also allow access to a larger market in a faster way but the third-party providers for the new entrants. Open Banking allows developers to build single solutions on an API addressing very specific problems, like for example, a cash flow based credit rating.

Romānova et al. ( 2018 ) undertook a questionnaire on the Payment Services Directive II. The results suggest that Open Banking will promote competitiveness, innovation, and new product development. The initiative is associated with low costs and customer satisfaction, but that some concerns about security, privacy and risk are present. These can be mitigated, to some extent, by secure protocols and layered permission access.

Discussion: strategic options

Faced with these disruptive trends, there are four strategic options for market participants to con- sider. There are (1) a defensive customer retention strategy for incumbents, (2) an aggressive customer acquisition strategy for challenger banks (3) a banking as a service strategy for new entrants, and (4) a payments strategy for social media platforms.

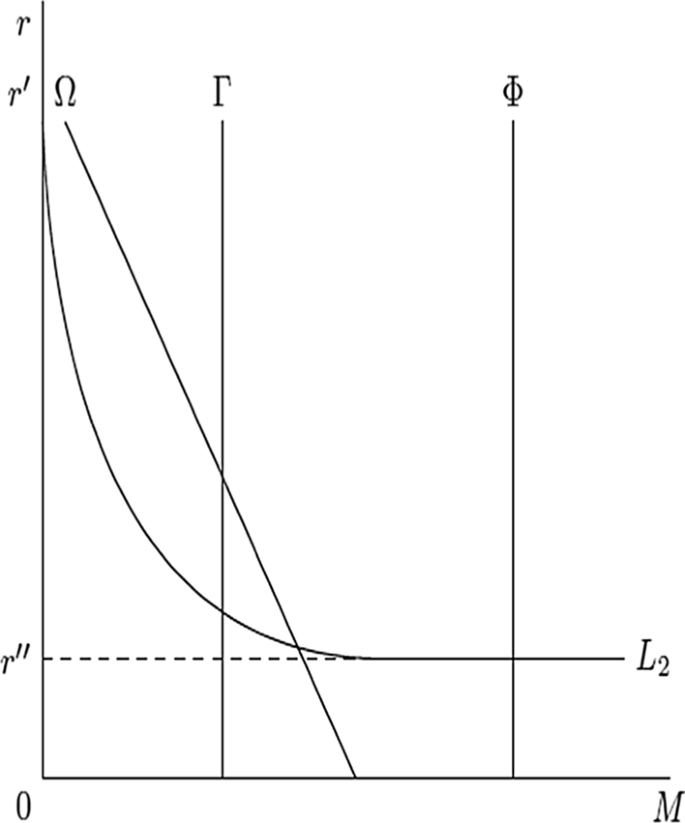

Each of these strategies has to be conducted in a competitive marketplace for money demand by potential customers. Figure 5 illustrates where the first three strategies lie on the tradeoff between money demand and interest rates. The payment strategy can’t be modeled based on the supply of money. In the figure, the market settles at a rate L 2 . The incumbent banks have the capacity to meet the largest supply of these loans. The challenger banks have a constrained function but due to a lower cost base can gain excess rent through higher rates of interest. The peer-to-peer bank as a service brokers must settle for the market rate and a constrained supply offering.

The money demand M by lenders on the y axis. Interest rates on the y axis are labeled as r I and r II . The challenger banks are represented by the line labeled Γ. They have a price and technology advantage and so can lend at higher interest rates. The brokers are represented by the line labeled Ω. They are price takers, accepting the interest rate determined by the market. The same is true for the incumbents, represented by the line labeled Φ but they have a greater market share due to their customer relationships. Note that payments strategy for social media platforms is not shown on this figure as it is not affected by interest rates

Figure 5 illustrates that having a niche strategy is not counterproductive. Liu et al ( 2020 ) found that banks performing niche activities exhibit higher profitability and have lower risk. The syndication market now means that a bank making a loan does not have to be the entity that services it. This means banks in the future can better shape their risk profile and manage their lending books accordingly.

An interesting question for central banks is what the future Deposit Supply function will look like. If all three forms: open banking, traditional banking and challenger banks develop together, will the bank of the future have the same Deposit Supply function? The Klein ( 1971 ) general formulation assumes that deposits are increasing functions of implicit and explicit yields. As such, the very nature of central bank directed monetary policy may have to be revisited, as alluded to in the earlier discussion on digital money.

The client retention strategy (incumbents)

The competitive pressures suggest that incumbent banks need to focus on customer retention. Reichheld and Kenny ( 1990 ) found that the best way to do this was to focus on the retention of branch deposit customers. Obviously, another way is to provide a unique digital experience that matches the challengers.

Incumbent banks have a competitive advantage based on the information they have about their customers. Allen ( 1990 ) argues that where risk aversion is observable, information markets are viable. In other words, both bank and customer benefit from this. The strategic issue for them, therefore, becomes the retention of these customers when faced with greater competition.

Open Banking changes the dynamics of the banking information advantage. Borgogno and Colangelo ( 2020 ) suggest that the access to account (XS2A) rule that it introduced will increase competition and reduce information asymmetry. XS2A requires banks to grant access to bank account data to authorized third payment service providers.

The incumbent banks have a high-cost base and legacy IT systems. This makes it harder for them to migrate to a digital world. There are, however, also benefits from financial technology for the incumbents. These include reduced cost and greater efficiency. Financial technology can also now support platforms that allow incumbent banks to sell NPL’s. These platforms do not require the ownership of assets, they act as consolidators. The use of technology to monitor the transactions make the processing cost efficient. The unique selling point of such platforms is their centralized point of contact which results in a reduction in information asymmetry.

Incumbent banks must adapt a number of areas they got to adapt in terms of their liquidity transformation. They have to adapt the way they handle data. They must get customers to trust them in a digital world and the way that they trust them in a bricks and mortar world. It is no coincidence. When you go into a bank branch that is a great big solid building great big facade and so forth that is done deliberately so that you trust that bank with your deposit.

The risk of having rising non-performing loans needs to be managed, so customer retention should be selective. One of the puzzles in banking is why customers are regularly denied credit, rather than simply being charged a higher price for it. This credit rationing is often alleviated by collateral, but finance theory suggests value is based on the discounted sum of future cash flows. As such, it is conceivable that the bank of the future will use financial technology to provide innovative credit allocation solutions. That said, the dual risks of moral hazard and information asymmetries from the adoption of such solutions must be addressed.

Customer retention is especially important as bank competition is intensifying, as is the digitalization of financial services. Customer retention requires innovation, and that innovation has been moving at a very fast rate. Until now, banks have traditionally been hesitant about technology. More recently, mergers and acquisitions have increased quite substantially, initiated by a need to address actual or perceived weaknesses in financial technology.

The client acquisition strategy (challengers)

As intermediaries, the challenger banks are the same as incumbent banks, but designed from the outset to be digital. This gives them a cost and efficiency advantage. Anagnostopoulos ( 2018 ) suggests that the difference between challenger and traditional banks is that the former address its customers problems more directly. The challenge for such banks is customer acquisition.

Open Banking is a major advantage to challenger banks as it facilitates the changing of accounts. There is widespread dissatisfaction with many incumbent banks. Open Banking makes it easier to change accounts and also easier to get a transaction history on the client.

Customer acquisition can be improved by building trust in a brand. Historically, a bank was physically built in a very robust manner, hence the heavy architecture and grand banking halls. This was done deliberately to engender a sense of confidence in the deposit taking institution. Pure internet banks are not able to do this. As such, they must employ different strategies to convey stability. To do this, some communicate their sustainability credentials, whilst others use generational values-based advertising. Customer acquisition in a banking context is traditionally done by offering more attractive rates of interest. This is illustrated in Fig. 5 by the intersect of traditional banks with the market rate of interest, depicted where the line Γ crosses L 2 . As a result of the relationship with banking yield, teaser rates and introductory rates are common. A customer acquisition strategy has risks, as consumers with good credit can game different challenger banks by frequently changing accounts.

Most customer acquisition, however, is done based on superior service offering. The functionality of challenger banking accounts is often superior to incumbents, largely because the latter are built on legacy databases that have inter-operability issues. Having an open platform of services is a popular customer acquisition technique. The unrestricted provision of third-party products is viewed more favorably than a restricted range of products.

The banking as a service strategy (new entrants)

Banking from a customer’s perspective is the provision of a service. Customers don’t care about the maturity transformation of banking balance sheets. Banking as a service can be performed without recourse to these balance sheets. Banking products are brokered, mostly by new entrants, to individuals as services that can be subscribed to or paid on a fee basis.

There are a number banking as a service solutions including pre-paid and credit cards, lending and leasing. The banking as a service brokers are effectively those that are aggregating services from others using open banking to enable banking as a service.

The rise of banking as a service needs to be understood as these compete directly with traditional banks. As explained, some of these do this through peer-to-peer lending over the internet, others by matching borrows and sellers, conducting mediation as a loan broker. Such entities do not transform assets and do not have banking licenses. They do not have a branch network and often don not have access to deposits. This means that they have no insurance protection and can be subject to interest rate controls.

The new genre of financial technology, banking as a service provider, conduct financial services transformation without access to central bank liquidity. In a distributed digital asset world, the assets are stored on a distributed ledger rather than a traditional banking ledger. Financial technology has automated credit evaluation, savings, investments, insurance, trading, banking payments and risk management. These banking as a service offering are only as secure as the technology on which they are built.

The social media payment strategy (disintermediators and disruptors)

An intermediation bank is a conceptual idea, one created solely on a social networking site. Social media has developed a market for online goods and services. Williams ( 2018 ) estimates that there are 2.46 billion social media users. These all make and receive payments of some kind. They demand security and functionality. Importantly, they have often more clients than most banks. As such, a strategy to monetize the payments infrastructure makes sense.

All social media platforms are rich repositories of data. Such platforms are used to buy and sell things and that requires payments. Some platforms are considering evolving their own digital payment, cutting out the banks as middlemen. These include Facebook’s Diem (formerly Libra), a digital currency, and similar developments at some of the biggest technology companies. The risk with social media payment platform is that there is systemic counter-party protection. Regulators need to address this. One way to do this would be to extend payment service insurance to such platforms.

Social media as a platform moves the payment relationship from a transaction to a customer experience. The ability to use consumer desires in combination with financial data has the potential to deliver a number of new revenue opportunities. These will compete directly with the banks of the future. This will have implications for (1) the money supply, (2) the market share of traditional banks and, (3) the services that payment providers offer.

Further research

Several recommendations for research derive from both the impact of disintermediation and the four proposed strategies that will shape banking in the future. The recommendations and suggestions are based on the mentioned papers and the conclusions drawn from them.

As discussed, the nature of intermediation is changing, and this has implications for the pricing of risk. The role of interest rates in banking will have to be further reviewed. In a decentralized world based on crypto currencies the central banks do not have the same control over the money supply, This suggest the quantity theory of money and the liquidity preference theory need to be revisited. As explained, the Internet reduces much of the friction costs of intermediation. Researchers should ask how this will impact maturity transformation. It is also fair to ask whether at some point in the future there will just be one big bank. This question has already been addressed in the literature but the Internet facilities the possibility. Diamond ( 1984 ) and Ramakrishnan and Thakor ( 1984 ) suggested the answer was due to diversification and its impact on reducing monitoring costs.

Attention should be given by academics to the changing nature of banking risk. How should regulators, for example, address the moral hazard posed by challenger banks with weak balance sheets? What about deposit insurance? Should it be priced to include unregulated entities? Also, what criteria do borrowers use to choose non-banking intermediaries? The changing risk environment also poses two interesting practical questions. What will an online bank run look like, and how can it be averted? How can you establish trust in digital services?

There are also research questions related to the nature of competition. What, for example, will be the nature of cross border competition in a decentralized world? Is the credit rationing that generates competition a static or dynamic phenomena online? What is the value of combining consumer utility with banking services?

Financial intermediaries, like banks, thrive in a world of deficits and surpluses supported by information asymmetries and disconnectedness. The connectivity of the internet changes this dynamic. In this respect, the view of Schumpeter ( 1911 ) on the role of financial intermediaries needs revisiting. Lenders and borrows can be connected peer to peer via the internet.

All the dynamics mentioned change the nature of moral hazard. This needs further investigation. There has been much scholarly research on the intrinsic riskiness of the mismatch between banking assets and liabilities. This mismatch not only results in potential insolvency for a single bank but potentially for the whole system. There has, for example, been much debate on the whether a bank can be too big to fail. As a result of the riskiness of the banking model, the banks of the future will be just a liable to fail as the banks of the past.

This paper presented a revision of the theory of banking in a digital world. In this respect, it built on the work of Klein ( 1971 ). It provided an overview of the changing nature of banking intermediation, a result of the Internet and new digital business models. It presented the traditional academic view of banking and how it is evolving. It showed how this is adapted to explain digital driven disintermediation.

It was shown that the banking industry is facing several documented challenges. Risk is being taken of balance sheet, securitized, and brokered. Financial technology is digitalizing service delivery. At the same time, the very nature of intermediation is being changed due to digital currency. It is argued that the bank of the future not only has to face these competitive issues, but that technology will enhance the delivery of banking services and reduce the cost of their delivery.

The paper further presented the importance of the Open Banking revolution and how that facilitates banking as a service. Open Banking is increasing client churn and driving banking as a service. That in turn is changing the way products are delivered.

Four strategies were proposed to navigate the evolving competitive landscape. These are for incumbents to address customer retention; for challengers to peruse a low-cost digital experience; for niche players to provide banking as a service; and for social media platforms to develop payment platforms. In all these scenarios, the banks of the future will have to have digital strategies for both payments and service delivery.

It was shown that both incumbents and challengers are dependent on capital availability and borrowers credit concerns. Nothing has changed in that respect. The risks remain credit and default risk. What is clear, however, is the bank has become intrinsically linked with technology. The Internet is changing the nature of mediation. It is allowing peer to peer matching of borrowers and savers. It is facilitating new payment protocols and digital currencies. Banks need to evolve and adapt to accommodate these. Most of these questions are empirical in nature. The aim of this paper, however, was to demonstrate that an understanding of the banking model is a prerequisite to understanding how to address these and how to develop hypotheses connected with them.

In conclusion, financial technology is changing the future of banking and the way banks intermediate. It is facilitating digital money and the online transmission of financial assets. It is making banks more customer enteric and more competitive. Scholarly investigation into banking has to adapt. That said, whatever the future, trust will remain at the core of banking. Similarly, deposits and lending will continue to attract regulatory oversight.

Availability of data and materials

Diagrams are my own and the code to reproduce them is available in the supplied Latex files.

Adrian T, Ashcraft AB (2016) Shadow banking: a review of the literature. In: Banking crises. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 282–315

Allen F (1990) The market for information and the origin of financial intermediation. J Financ Intermed 1(1):3–30

Article Google Scholar

Anagnostopoulos I (2018) Fintech and regtech: impact on regulators and banks. J Econ Bus 100:7–25

Berger AN, Herring RJ, Szegö GP (1995) The role of capital in financial institutions. J Bank Finance 19(3–4):393–430

Berger AN, Miller NH, Petersen MA, Rajan RG, Stein JC (2005) Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. J Financ Econ 76(2):237–269

Bernanke B, Gertler M, Gilchrist S (1996) The financial accelerator and the flight to quality. The review of economics and statistics, pp1–15

Bord V, Santos JC (2012) The rise of the originate-to-distribute model and the role of banks in financial intermediation. Federal Reserve Bank N Y Econ Policy Rev 18(2):21–34

Google Scholar

Borgogno O, Colangelo G (2020) Data, innovation and competition in finance: the case of the access to account rule. Eur Bus Law Rev 31(4)

Braggion F, Manconi A, Zhu H (2018) Is Fintech a threat to financial stability? Evidence from peer-to-Peer lending in China, November 10

Brei M, Borio C, Gambacorta L (2020) Bank intermediation activity in a low-interest-rate environment. Econ Notes 49(2):12164

Buchak G, Matvos G, Piskorski T, Seru A (2018) Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. J Financ Econ 130(3):453–483

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Detragiache E (2002) Does deposit insurance increase banking system stability? An empirical investigation. J Monet Econ 49(7):1373–1406

Diamond DW (1984) Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. Rev Econ Stud 51(3):393–414

Diamond DW, Dybvig PH (1983) Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. J Polit Econ 91(3):401–419

Diamond DW, Rajan RG (2000) A theory of bank capital. J Finance 55(6):2431–2465

Edgeworth FY (1888) The mathematical theory of banking. J Roy Stat Soc 51(1):113–127

Fama EF (1980) Banking in the theory of finance. J Monet Econ 6(1):39–57

Gurley JG, Shaw ES (1956) Financial intermediaries and the saving-investment process. J Finance 11(2):257–276

Klein MA (1971) A theory of the banking firm. J Money Credit Bank 3(2):205–218

Kou G, Akdeniz ÖO, Dinçer H, Yüksel S (2021) Fintech investments in European banks: a hybrid IT2 fuzzy multidimensional decision-making approach. Financ Innov 7(1):1–28

Levine R (2001) International financial liberalization and economic growth. Rev Interna Tional Econ 9(4):688–702

Liu FH, Norden L, Spargoli F (2020) Does uniqueness in banking matter? J Bank Finance 120:105941

Pozsar Z, Singh M (2011) The nonbank-bank nexus and the shadow banking system. IMF working papers, pp 1–18

Ramakrishnan RT, Thakor AV (1984) Information reliability and a theory of financial intermediation. Rev Econ Stud 51(3):415–432

Reichheld FF, Kenny DW (1990) The hidden advantages of customer retention. J Retail Bank 12(4):19–24

Romānova I, Grima S, Spiteri J, Kudinska M (2018) The payment services directive 2 and competitiveness: the perspective of European Fintech companies. Eur Res Stud J 21(2):5–24

Modigliani F, Miller MH (1959) The cost of capital, corporation finance, and the theory of investment: reply. Am Econ Rev 49(4):655–669

Schumpeter J (1911) The theory of economic development. Harvard Econ Stud XLVI

Song F, Thakor AV (2010) Financial system architecture and the co-evolution of banks and capital markets. Econ J 120(547):1021–1055

Swankie GDB, Broby D (2019) Examining the impact of artificial intelligence on the evaluation of banking risk. Centre for Financial Regulation and Innovation, white paper

Thakor AV (2020) Fintech and banking: What do we know? J Financ Intermed 41:100833

Vishnu S, Agochiya V, Palkar R (2017) Data-centered dependencies and opportunities for robotics process automation in banking. J Financ Transf 45(1):68–76

Williams MD (2018) Social commerce and the mobile platform: payment and security perceptions of potential users. Comput Hum Behav 115:105557

Download references

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowldgements.

There was no funding associated with this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Financial Regulation and Innovation, Strathclyde Business School, Glasgow, UK

Daniel Broby

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author confirms the contribution is original and his own. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Broby .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

I declare I have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Broby, D. Financial technology and the future of banking. Financ Innov 7 , 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-021-00264-y

Download citation

Received : 21 January 2021

Accepted : 09 June 2021

Published : 18 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-021-00264-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cryptocurrencies

- P2P Lending

- Intermediation

- Digital Payments

JEL Classifications

- Open access

- Published: 07 July 2023

Unlocking the full potential of digital transformation in banking: a bibliometric review and emerging trend

- Lambert Kofi Osei ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7461-4839 1 ,

- Yuliya Cherkasova 2 &

- Kofi Mintah Oware 1

Future Business Journal volume 9 , Article number: 30 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

7458 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

Every aspect of life has been affected by digitization, and the use of digital technologies to deliver banking services has increased significantly. The purpose of this study was to give a thorough review and pinpoint the intellectual framework of the field of research of the digital banking transformation (DBT).

Methodology

This study employed bibliometric and network analysis to map a network in a single study, and a total of 268 publications published between 1989 and 2022 were used.

Our findings demonstrate that the UK, USA, Germany, and China are the countries that have conducted most of the studies on the digital banking transformation. Only China and India are considered emerging economies; everyone else is looking at it from a developed economy perspective. Additional research reveals that papers rated with A* and A grades frequently publish studies on digital banking transformation. Once more, the analysis identifies key theoretical underpinnings, new trends and research directions. The current research trend points toward FinTech, block chain, mobile financial services apps, artificial intelligence, mobile banking service platforms and sustainable business models. The importance of emphasizing the need for additional research in these fields of study cannot be stressed, given the expanding popularity of blockchain technology and digital currency in the literature.

Originality

It appears that this is the first study that examines the theoretical studies of digital banking transformation using bibliometric analysis. The second element of originality is about the multiple dimensions of the impact of technology in the banking sector, which includes customer, company, bank, regulation authority and society.

Introduction

The advent of information communication technology (ICT) is believed to have caused a paradigm shift in all aspects of human life. Technology has therefore become a necessary, unavoidable demand for society and the business environment, from work automation to service digitalization, from cloud computing to data analytics, from virtual collaboration to smart homes. Almost every industry is undergoing constant transformation because to technology. In the past 20 years, digitalization has had an impact on a variety of sectors, presenting fresh business prospects and encouraging new systems of innovation [ 1 ].

The finance sector is actively experimenting and inventing with the power of technology's digitization. It is also one of the industries that have successfully embraced digitization. One of the most laudable digital developments of the finance sector is the widespread adoption of digital banking over traditional banking methods. Recently, potentially disruptive technological breakthroughs and Internet-based solutions appear to have been introduced to the banking industry, one of the most established and conservative sectors of the economy. Digital transformation in banking is essential to enhance how banks and other financial organizations learn about, communicate with and satisfy the needs of customers. An effective digital transformation starts with understanding digital client behavior, preferences, choices, likes, dislikes, and stated and unstated expectations, to be more precise. Many academics are interested in how information and communications technology is advancing and how it can affect the banking industry [ 2 ]. However, the bibliometric analysis conducted by academics utilizing VOS viewer is assumed to be the first to look at the digital banking transformation (DBT) studies from a performance analysis and science mapping perspective.

Large data sets from databases like Web of Science, Scopus index or Dimension are permitted for bibliometric study. The bibliometric analysis moves the banks' digital transformation survey from single to multi-dimensional outcomes. A quick search of DBT studies shows that the first journal was published in 1989, despite the earliest forms of digital banking being traced back to the advent of ATMs and cards in the 1960s. The quantum of increase after 2014, amounting to 203 articles, representing 76% of all published articles on the topic, compels this study to focus on this field of DBT studies. We contend that establishing the area's intellectual framework is more crucial than ever. As a result, we make a contribution by offering a relevant, distinctive and significant intellectual map of the literature on digital banking studies through quantitative and bibliometric analysis. In mapping the intellectual structure of DBT, our study sets out to address the following critical research questions:

Who are the predominant contributors (publication by year, journals, publishers, authors, publication, journal quality, country, and universities) to the DBT theory?

What are the country's collaboration and citation analysis of the impact of digitalization on banks?

What is digital banking theory's intellectual foundation (co-citation)?

What are emerging research themes/trends and future direction (bibliography coupling

and keywords analysis) to digital banking theory?

In response to the above four questions, this study has at least four significant additions to the literature on digital banking. First, we extend and build upon prior assessments of digital banking by offering a factual, quantitative perspective on the theory's historical development across time. Of course, this study considers notable contributors, the intellectual framework and theoretical groundwork of the discipline, the degree to which individuals are connected, and thematic subdomains. We show how digital banking has advanced by evaluating the significant offshoots from the original work by [ 3 ]. Second, we objectively assess how faithfully emerging subtopic literature streams acknowledge and build upon Burk and Pfitzmann’s seminal works. As a result, our paper is uniquely suited to detect significant gaps that might exist in subtopic areas, and we offer suggestions for improving literature unification. Thirdly, we show how scholars of digital banking have historically changed their study goals over time in response to gaps between theory and practice in order to determine how faithfully they have addressed these gaps. Finally, we contribute to the digital banking literature by identifying emerging digital banking research and study trends. Overall, we think that our research exposes chances to grow more effectively and collaboratively in the future by highlighting well-traveled roads that previous researchers have taken, identifying potential cracks that may leave the literature in a state of disarray, and so forth [ 4 ].

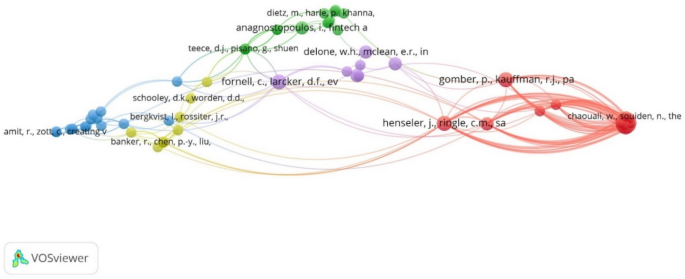

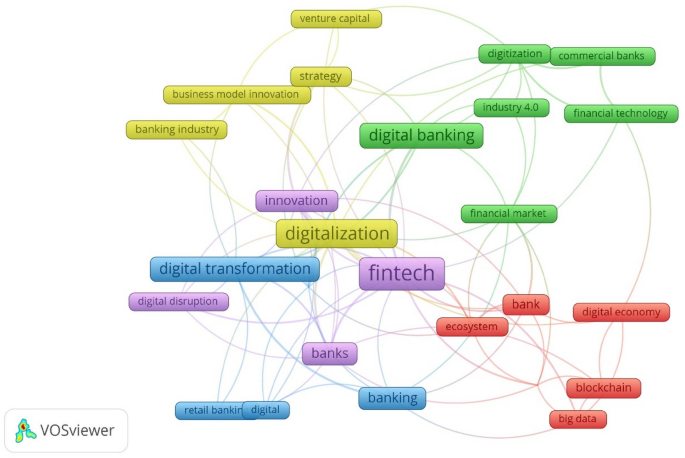

This study used bibliometric and network analysis to map a network that comprises authors, co-authors, keyword occurrences, journal citations and author names in a single study. The approach can give a thorough overview and pinpoint the field's intellectual hierarchy [ 5 ]. Furthermore, according to [ 6 ], bibliometric approaches are suitable for mapping the academic structure of a certain area because doing so enables researchers to recognize "'what,' 'where' and 'by whom' founded the field. We carry out a thorough bibliometric evaluation to meet the research objectives by carefully extracting the sample literature using the proper inclusion and exclusion criteria and selecting the search string. The first stage involved a descriptive analysis, while the second stage involved a comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Utilizing VOSviewer and Rstudio assistance, citation and co-citation analyses were carried out to determine the intellectual structure of the study on digital banking studies. Weighted citation measures were used to identify the lead publications from the clusters.

The format of our paper is as follows: A brief theoretical overview of the DBT literature, including its core principles, significant developments and limits, is given in section " Theoretical background ." Section " Methods " describes the research approach in depth, and section " Results " shows the results of our investigation. The limitations of our study and their consequences for theory and practice are discussed in section " Discussions and future research agenda ." Finally, we provide our final observations in section " Conclusion ."

Theoretical background

Society, economics, banks and banking are changing as a result of technological advancement. Banks are an unneeded remnant whose purpose is best provided by alternate arrangements, even though we still need banking. The value chain of traditional banking has been disintermediated by technology, and its business model has been severely altered. As a result, Fin-Tech adoption and digital technology collaboration are widespread, constant and profoundly changing company structures [ 7 ]. Nearly 90% of banks fear losing business to Fin-Tech, which has replaced traditional value chains with shorter multi-modal and multi-directional nodes, according to KPMG's 2017 annual reports. Digitalization permeates the contemporary world, and the banking industry is no different. Our lives seemed to have grown so ingrained with digital technology that we would feel empty without it. Banks of all sizes are investing a lot in digital initiatives to maintain their uniqueness and meet as many of their customers' needs as possible. Digitalization leads to more customization and closer to customers. It is called digital banking when a bank renders its services online, and customers can make transactions and other activities online. Since over 73% of consumers use products from numerous platforms, Lee and Shin [ 8 ] highlight that bank model disruption and ascribe this to ongoing innovation followed by disruptive challenges, with the possibility of losing market share to Fin-Techs omnipresent.Mobile technologies and social media digitize bank value chains simultaneously addressing and influencing client demands and expectations.

However, according to our knowledge, not much research has been done on the banking sector. Nevertheless, it is well known that the banking sector, which is frequently IT-intensive, requires special consideration due to its significance for the whole economy. Berger [ 2 ] emphasizes that the benefits of technology adoption may not convert into improved production, which is consistent with the literature mentioned above. According to Berger, rather than the organization itself, the advantages of technology might be passed on to consumers and other production-related elements. Sharing data allow banks to process information more efficiently while also achieving huge economies of scale in the processing of payments. For instance, banks have reportedly employed information processing to handle deposit and loan client information as well as to more accurately assess risks, according to Berger and Mester. Additionally, they have employed telecommunications technologies to expeditiously process payments and disseminate this data while consuming fewer resources (2003, p. 58). This would imply that cost productivity increased in the 1990s.

Digital transformation has an impact on business processes and alters how banks conduct operations. A contributing aspect to the traditional relationship between customers and banks is digital transformation. Customers in particular have the right to use a variety of communication channels to engage in active and convenient engagement with banks and other customers via online customer support services. Most importantly, digital transformation enables banks to service a variety of consumers simultaneously, enhancing the bank's operational efficiency. In addition, the employee's job procedures are digitalized, reducing time and resources for both human resources and transaction execution. Thus, the bank will benefit from digital transformation by increasing output (raising the number of clients) and decreasing input expenses (reducing the number of employees and the time to make transactions).

The banking and FinTech industries will expand further in joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions toward convergence among banks, FinTech and technology organizations, and social media network providers as the new decade gets underway [ 9 ]. Digital technologies including blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), data platforms, cybersecurity regulation technology and strategic collaborations will be well positioned to be retained in the banking business in a completely digitally changed financial environment [ 10 ]. Up until the advent of digital banking and the branch-based banking model in the early 1990s, traditional banking remained unaltered and unopposed. In the USA, Stanford Federal Credit Union opened the first online bank in 1994. The number of local bank branches has substantially decreased globally with the advent of online banking. Globally, the number of digital banks has been steadily rising at the same time. The first digital disruptor was ING Direct, which launched as an entirely online bank in 1996 and over the course of a little more than a decade attracted more than 20 million customers in nine countries without having to make any investments in physical infrastructure. In 2013, the FinTech bank "N26" received initial approval for a banking license. Amazon introduced an e-commerce-based checking account feature in 2021, while Facebook developed a social network-based banking service in 2020. By 2020, banking clients have been accustomed to using mobile banking apps, direct deposit to P2P payments and cloud-based banking platforms with AI.

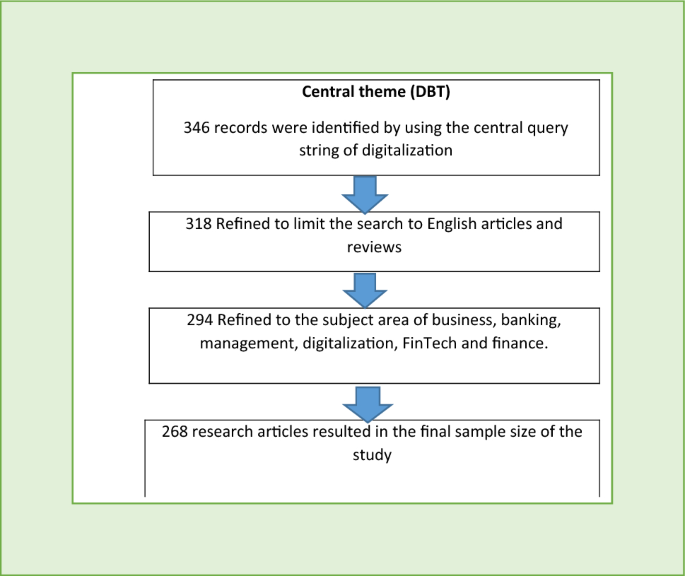

To address our research issues in the present study, we employed two bibliometric analytic techniques. Since bibliometric analysis is quantitative, systematic, transparent and repeatable, it is strongly recommended for mapping the intellectual architecture of a literature stream [ 11 ]. The specifics of our research methodology and key conclusions are shown in Fig. 1 .

Flow chart of searching strategy and data collection process

To achieve its goals, this study suggests using publications and citations to analyze the performance of authors, institutions, countries and journals. Another unique approach used in this study is known as scientific mapping. Co-authorship analysis, clustering, citation analysis and keywords analysis are the approach factors [ 5 ]. Bibliometric approaches have been applied in recent investigations [ 12 , 13 ]. Then, we employ it to start the process of developing a bibliometric investigation [ 5 ]. The following actions are a part of the four-step process: data gathering and analysis, selecting the limiting criteria, data analysis, discussions and conclusions.

Defining the search terms

We started by conducting a methodical keyword search of the current literature on digital banking [ 14 ]. We extracted data from the Scopus index database. According to [ 15 ], Scopus has a larger journal than any other service that conducts data mining. As a result, this study made use of this database to mine data for its bibliometric analysis. To identify digital banking impact articles, we used the keyword methodology outlined by scholars who have recently conducted reviews of DBT. By concentrating primarily on work that has undergone thorough peer review, we aimed to maintain the academic integrity of our sample. Conference transcripts and book chapters were taken out of the analysis. Additionally, we excluded any non-English-language publications; 298 articles make up our final sample, which is deemed adequate for bibliometric study. These articles were published between 1989 and 2022. The keys words are: digital, bank, banking, business model, company, finance, economics and social sciences.

Keyword protocol applied in Scopus for extracting articles.

Data search and collection

As a result of several authors using the Scopus database for bibliometric analysis, it was chosen as the database from which the study's data were extracted [ 12 , 13 ]. In comparison with Web of Science and Dimension, the Scopus database has many indexed journals. The first stage of data extraction involved 295 publications with the titles "effect of digitalization on banks" and "digital transformation of banks" in June 2022. The following stage of the data processing was restricted to 268 English-language journals. The research is restricted to publications in the fields of banking, business management, accounting, economics, econometrics and finance. The last research search turned up 268 papers that were written between 1985 and 2022. Our literature review and bibliometric analysis are built on the foundation of the sample size of 268 articles. The method of data extraction is displayed in Table 1 .

This study raises different research questions covering contributors to DBT or impacts of digitalization on banks and banking, average journals and journal quality citation, digital banking intellectual foundations (co-citation), emerging research themes/trends and future direction (bibliography coupling and keywords analysis) in institutional theory.

Who are the predominant contributors to digital banking theory

This study responds to the first research question by addressing the dominant contributors to the DBT theory by using the following criteria: publication by year, journals, publishers, authors, publication, journal quality, country, and universities.

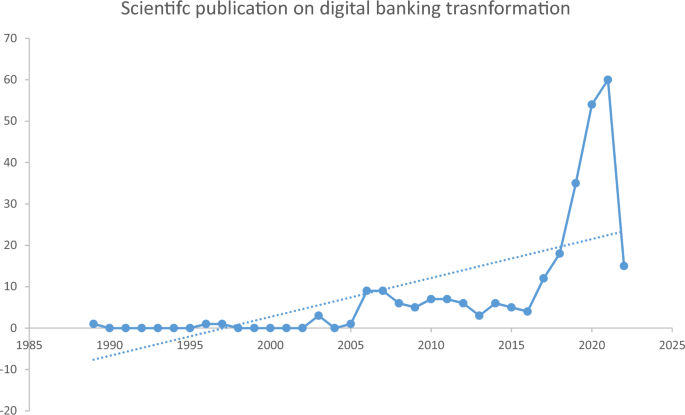

Publication by year

Figure 2 illustrates the number of DBT publications between 1989 and early 2022, recording 268 scientific publications. DBT received little attention from the scientific community in the early years from 1989 to 2005, recording as little as seven publications. The available data further show that publication increased slightly to sixty-seven (67) over a twenty (20) year period from 2006 to 2016. However, there was a dramatic change in this trend afterwards. Approximately 72 percent of these scientific publications, representing one hundred ninety-four (194) articles, occurred in the last six years. The figure further revealed that the years 2020 and 2021 alone accounted for 43 percent of all scientific publications in the field of DBT. Perhaps the havoc of Covid–19 and the strategic role of banks in successfully influencing the payment system architecture in particular resonated well with researchers to pay much attention to the field around this later period. While the quantity of publications has increased, publications within elite journals continue to grow. As recently as 2017, more over 40% of DBT research was published in prestigious publications. In fact, since 2017, the average annual proportion of publications in the top tier to all publications is 62 percent. As a result, our findings imply that the standard of published research has generally kept up with the volume of publications.

Trends in digital banking publication since 1989

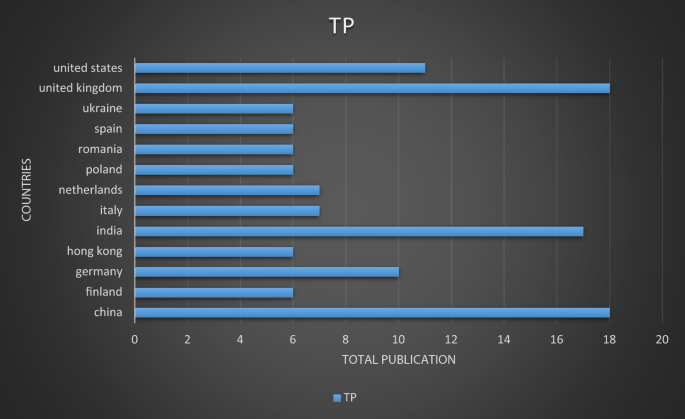

Publication activity by country

Our findings also show that DBT research has a truly global reach, as shown by the participation of authors from 65 different countries. Figure 3 gives a graphic representation of the top countries publishing DBT research. For better clarity, the study limited Fig. 3 to cover countries with more than five publications. Although the publication of digital banking is international, it is interesting to notice that a significant portion of the work originates from a limited group of wealthy nations. More specifically, more than 46% of all published DBT studies come from the USA, UK, India, China, Germany, Netherlands, Hon Kong, Romania, Finland, Poland, Ukraine, Italy and Spain. Only China and India are from emerging economies. Figure 3 illustrates publication activities by country.

Top publishing countries on DBT

Publishing activity by journal