An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

1. Use quotes to search for an exact match of a phrase.

2. Put a minus sign just before words you don't want.

3. Enter any important keywords in any order to find entries where all these terms appear.

- The PSNet Collection

- All Content

- Perspectives

- Current Weekly Issue

- Past Weekly Issues

- Curated Libraries

- Clinical Areas

- Patient Safety 101

- The Fundamentals

- Training and Education

- Continuing Education

- WebM&M: Case Studies

- Training Catalog

- Submit a Case

- Improvement Resources

- Innovations

- Submit an Innovation

- About PSNet

- Editorial Team

- Technical Expert Panel

The Role of Community Pharmacists in Patient Safety

What is a community pharmacy.

Community pharmacies are sometimes equated to retail pharmacies, operating out of both large and small chains or grocery stores. However, what constitutes a community-based pharmacy is much broader than the traditional retail setting. Community-based pharmacies also include outpatient pharmacies found within health systems, Federally Qualified Health Centers, primary care clinics, compounding pharmacies that prepare medications for patients who require unique dosing or modified formulations, 1 and specialty pharmacies where patients receive outpatient care for complex medication therapies. 2 Pharmacists may pursue community-based residencies or fellowships to enhance their clinical and leadership skills, preparing them for a role in community pharmacy. 3

What roles does a community pharmacist play in patient safety?

Historically, the concept of the “five rights” has been used to describe the steps that lead to safe medication use: the right dose of the right medication taken by the right patient at the right time and by the right route. However, this concept is oversimplified, as there are additional steps of safe medication use that should also be considered; steps that are dependent on the context in which the medication-related process is occurring. Each part of the medication use process may contain different numbers and types of “rights”. For example, in the community pharmacy setting, outcomes like the right education, right monitoring, right documentation, and right drug formulation may also be considered.

The modern concept of medication safety is much broader in scope than the “five rights” and the focus has subsequently shifted with an increased emphasis placed on the contribution of systems factors to medication safety. Factors not directly related to medications are considered, including how the workflow, technologies, policies and procedures, and other systems factors support the outcomes of the various rights, rather than focusing solely on completion of an oversimplified checklist.

Pharmacists in the community ensure medication safety similarly to how they would in any healthcare environment: throughout the medication-use process, including the ordering of medications to their storage, transcription, preparation, dispensing, counseling, and more. Prior to the dispensing process, the community pharmacist provides a clinical review of prescribed medications to ensure the therapies are appropriate. This review includes dosing appropriateness, interactions with other prescribed medications, contraindications, and more, while also considering that medications may have been ordered by multiple prescribers. 4,5 The pharmacist also provides critical monitoring in the dispensing of controlled substances, such as consulting prescription drug monitoring programs to look for patterns that might indicate abuse or diversion and to screen for potentially fatal interactions between medications that may come from multiple prescribers. 6,7 Pharmacists must identify patients at risk for fatal overdose and facilitate access to the emergency opioid reversal drug Narcan® (naloxone) as well as substance abuse treatment services when appropriate.

A clinical review is essential for all prescriptions and can help ensure that any errors occurring as a result of the care transition process are caught and corrected before the medication is dispensed. 8 For example, in the discharge process, the inpatient providers may have an incomplete history of the patient’s existing prescriptions when formulating the treatment plan. In addition, medications that may have been appropriate during the inpatient stay, but inappropriate for home use, may inadvertently be carried over into the patient’s outpatient treatment plan.

In addition to the dispensing process, the community pharmacist plays a critical patient safety role when it comes to ensuring that patients appropriately understand their medications. 4 Community pharmacists are equipped to provide education and counseling to patients to address questions they may have regarding factors such as dosing, administration, storage, potential side effects, and how to taper medications for acute events. Similarly, community pharmacists are an invaluable resource for supporting public health initiatives. One study found that patients visited a community-based pharmacy 35 times per year, as compared to a primary care physician, which occurs, on average, 4 times per year. 2 This frequent contact with patients makes community pharmacists optimally positioned to support public health initiatives and triage concerns. Numerous studies have proven the positive impact of pharmacists on preventative care such as health screenings and immunizations, opioid management, smoking cessation efforts, and management of chronic diseases such as diabetes. 9

What supports community pharmacies in providing patient safety?

Patient safety is best achieved in organizations that have a strong culture of safety . Organizations with a strong culture of safety are not only better positioned to ensure patient safety from the outset, but also more likely to recognize the importance of dedicating the time and resources to tracking, understanding, and appropriately addressing patient safety events or near-misses. Surveys such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Community Pharmacy Survey on Patient Safety can help pharmacies assess the current state of their safety culture and identify any areas for improvement.

In addition to a strong culture of safety, open communication with, and ease of access to, prescribers can support community pharmacists in the prevention of errors. 10,11 Interoperability between data systems, notably electronic health records and state-based health information exchanges, facilitates this open communication by ensuring consistency of information and seamless sharing of patient data between the pharmacist and the prescriber. Ease of access to providers enables the pharmacist to efficiently address potential concerns discovered upon clinical review of the patient’s treatment plan.

Finally, fostering relationships between patients and pharmacists can support safe continuity of care by helping patients develop trust in their pharmacists, increasing their likelihood to seek counseling, address concerns regarding their medication therapy, and provide a more comprehensive medical history.

Georgia Galanou Luchen, Pharm. D. Director, Member Relations Section of Community Pharmacy Practitioners and Section of Pharmacy Educators American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Bethesda, MD

Kendall K. Hall, MD, MS Managing Director, IMPAQ Health IMPAQ International Columbia, MD

Kate R. Hough, MA Editor, IMPAQ Health IMPAQ International Columbia, MD

- Compounding. National Community Pharmacists Association. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://ncpa.org/compounding

- Moose J, Branham A. Pharmacists as influencers of patient adherence. Pharmacy Times. August 21, 2014. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/pharmacists-as-influencers-of-patient-adherence-

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, American Pharmacists Association. Guidance document for the accreditation standard for postgraduate year one (PGY1) community-based pharmacy residency program. Updated March 2021. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/professional-development/residencies/docs/ashp-apha-pgy1-community-based-standard-guidance.ashx

- Goode JV, Owen J, Page A, Gatewood S. Community-based pharmacy practice innovation and the role of the community-based pharmacist practitioner in the United States. Pharmacy (Basel) . 2019;7(3):106. doi:10.3390/pharmacy7030106

- Messerli M, Blozik E, Vriends N, Hersberger KE. Impact of a community pharmacist-led medication review on medicines use in patients on polypharmacy--a prospective randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res . 2016;16:145. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1384-8

- Doong KS, Gaccione DM, Brown TA. Community pharmacist involvement in prescription drug monitoring programs. Pharmacy Times . December 13, 2016. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/community-pharmacist-involvement-in-prescription-drug-monitoring-programs

- Upton C, Gernant SA, Rickles NM. Prescription drug monitoring programs in community pharmacy: an exploration of pharmacist time requirements and labor cost. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(6):943-950. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.07.002

- Tetuan CE, Guthrie KD, Stoner SC, May JR, Hartwig DM, Liu Y. Impact of community pharmacist-performed post-discharge medication reviews in transitions of care. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(6):659-666. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.06.017

- Strand MA, DiPietro Mager NA, Hall L, Martin SL, Sarpong DF. Pharmacy contributions to improved population health: expanding the public health roundtable. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E113. Published 2020 Sep 24. doi:10.5888/pcd17.200350

- Botross A, Botross E, Ho C. Communication is key to medication safety. Hospital News. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://hospitalnews.com/communication-is-key-to-medication-safety

- National Healthcareer Association. Effective communication in vital for pharmacy technicians. Pharmacy Times. May 7, 2021. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/effective-communication-is-vital-for-pharmacy-technicians

In Conversation With... Georgia Galanou Luchen, Pharm. D.

Editor’s Note: Georgia Galanou Luchen, Pharm. D., is the Director of Member Relations at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). In this role, she leads initiatives related to community pharmacy practitioners and their impact throughout the care continuum. We spoke with her about different types of community pharmacists and the role they play in ensuring patient safety.

Kendall Hall: So, Gina, can you just introduce yourself and describe your current role?

Gina Luchen: My name is Gina Galanou Luchen, and I am a pharmacist by training. I completed my undergraduate and Doctor of Pharmacy degrees at the University of Kansas School of Pharmacy. I then completed a postgraduate community-based pharmacy residency, followed by the ASHP [American Society of Health-System Pharmacists] Executive Fellowship in Association Leadership and Management. I am currently serving as the ASHP Director of Member Relations for the Section of Community Pharmacy Practitioners and Section of Pharmacy Educators. A little bit about my organization: the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) represents pharmacists serving as patient care providers both in acute and ambulatory care settings. We have nearly 58,000 members that work in pharmacy across the continuum of care with a goal to improve medication use, enhance patient safety, and advance pharmacy practice. In my role, I focus on community-based practitioners who are practicing within health systems or other community pharmacy settings. I am also highly involved with pharmacy education, supporting our members who educate student pharmacists and pharmacy residents and train the pharmacy workforce.

KH: Let’s talk about the training. Are there differences between how you train for working in an acute care facility versus in a community setting?

GL: That's a great question. When you graduate from a college or school of pharmacy, there are many postgraduate training opportunities. There are first- and second-year residency training programs. First-year pharmacy residencies are broken down into three major categories. One is what we consider the traditional pharmacy practice residency in an acute care setting. Residents usually train in a hospital or health-system environment, providing inpatient and outpatient pharmacy services within that institution. Second are community-based residencies, focusing on training within community pharmacies and ambulatory care clinics. Third are managed care residencies, and that's more specialized and looks at using clinical evidence and economics to optimize population health outcomes and medication benefits. There are also fellowship programs in research, policy, academia, nonprofit, industry, or other specialty practice areas.

KH: Thank you—that's very helpful for some context. To provide some clarity for individuals who may not be as familiar, what does it mean to be a community pharmacy, and what are the various operational types?

GL: When you think about a community pharmacy, most people bring to their mind their neighborhood pharmacy. But in the broad sense, community pharmacy is any healthcare setting that provides medication-related services to a patient within their community. The practice encompasses a large number of services and settings. You have the retail setting that can be found as stand-alone stores, both in smaller or larger chains, within grocery stores, or other retail settings. Then you have hospital or health-system outpatient pharmacies, which may serve patients of that particular institution or serve the larger public. And then you have clinic-based pharmacies that might be part of an ambulatory practice. For example, think of a specialized psychiatry clinic, or a primary care and multi-specialty physicians’ office, or assisted living facilities that may have community pharmacies embedded within them. Then you might have pharmacies that serve individuals who are homebound or provide home infusion therapy. Some pharmacies are designated as specialty pharmacies, and they provide specialized medications that treat complex conditions. There are also mail order pharmacies. And, if a patient requires nontraditional dosage forms or strengths of the medication, there are compounding pharmacies that handle custom compounded medications. In a nutshell, there are many settings in which community pharmacists practice and where community pharmacies can be found, but whenever you think of a patient condition that requires any type of medication therapy or any type of intervention within the community, you will likely find a pharmacy that helps to serve that patient and meet those needs.

KH: Wonderful. Thank you. I don't think we realized just how broad that term is and what it covers. With all of these different settings, what are the common and overarching goals of these community-based pharmacies?

GL: I think the goal of community-based practice is to support patients on an individual level not just in managing their medications, but also in managing their health, and to support public health in general. Outside of the traditional dispensing of medications, pharmacies in the community setting offer a variety of other services like medication counseling or disease state education. They assist patients in managing their entire medication therapy. Most community pharmacies today also provide immunizations, they provide point-of-care testing, and they provide consultations and other services needed within that population. There was a study that looked at accessibility for community pharmacies and found that nearly 90% of Americans live within 5 miles of a pharmacy. 1 This represents the tremendous opportunity that community pharmacists have to impact patient care, and that's why all these services that go beyond medication dispensing are so crucial to patients. When you think about the pharmacy’s responsibility, it's really to protect patients and to ensure that their therapy is optimal, safe, and effective. The pharmacist role within the community, and really across the continuum of care, is to increase medication optimization and safety, and ultimately to practice at the top of their license to help patients be healthier.

KH: Well, I think that's a great transition point to start talking about patient safety. What are some of the common patient safety events that can occur across these different settings? And what are some of the considerations that the pharmacist manages in order to protect the public?

GL: Pharmacists in the community manage safety similarly to how they would in any healthcare environment where patients are treated, and medications are handled. To start with, every pharmacist ensures that the services they provide encompass what we refer to as the “Five Rights,” and those are that the right drug makes it to the right patient, at the right dose, in the right route, and at the right time. Although these Five Rights are fundamental in establishing medication handling and dispensing, it's not always simple to ensure because, as we mentioned earlier, community-based pharmacists are part of a larger care continuum, and they provide services that are well beyond the dispensing process. So, when we're thinking about the safety considerations for a community pharmacy, we have to look at every single step, from the medication order to dispensing, the patient’s receipt of the medication, and the patient’s home.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) released a report 2 about the key elements of a medication review system for community pharmacies, and they described a number of different elements within that process. But in summary, it starts with the procurement of the medication, so that's purchasing the medication, which includes navigating through drug shortages, verifying that the medication comes from reputable sources, accounting for the shelf life and the storage of the medication, and even keeping a quantity on hand of key medications that are needed in the community for immediate access. That’s all what we call part of the medication supply chain safety and integrity, and those are things that community pharmacists look at on a daily basis.

You then have the therapeutic considerations of safety—that is, ensuring that the medication prescribed is intended to treat or manage the patient’s disease appropriately. This can take into account pharmacists screening for medication duplications, omissions, allergy screenings that could interfere with the prescribed therapy, a new diagnosis that may have been added and needs to be accounted for, ensuring that the dose is appropriate, looking at drug interaction, etc. So there’s a whole therapeutic profile review that occurs in every medication that's dispensed in the community, and it requires a full understanding of the patient's medication profile and their health status. Sometimes verification requires picking up the phone and calling the prescriber or patient.

Then you move into the dispensing process. We mentioned those Five Rights, verifying that the interpretation of the prescription you're getting is appropriately entered and accurately dispensed and that you're filling the correct medication. Other factors would be operational workflow, staffing, technology, and the environment.

Two more things that people don't necessarily think about within the pharmacist’s realm of what we do to secure patient safety include the patient education component. This is ensuring that the patient understands the treatment provided to them. An example can be a pharmacist who is completing a medication review to ensure that the patient is comfortable with what they're taking, that they understand why they're taking their therapy, or counseling on controlled substance utilization or even opioid storage and safety. Lastly, care transitions. It's important to remember that community pharmacists are part of the overall healthcare team for a patient. Their role is crucial in reinforcing education after discharge, coordinating with the prescriber or multiple specialists, to ensure that everybody is on the same page as far as the medication profile for the patient, and preventing any duplications or omissions. The pharmacist is the last line of defense between the patient and that medication, and it's the last opportunity to protect the health of patients.

KH: Listening to you makes me realize that there's such an opportunity for the pharmacist in these settings to serve as a safety net or a double check to some of the things that go on both in the physician's office and at home. How do you take advantage of that? Is it the education piece with the patients?

GL: The community pharmacy, and pharmacy as a profession in general, has a really strong culture of safety. We realize how important our role is in protecting the public. If you look at the oath of the pharmacist, it starts by saying, “I'll consider the welfare of humanity and relief of suffering as my primary concerns” and then goes on to mention that assuring optimal outcomes for patients is really a top priority. You carry a lot of that responsibility as part of the overall culture of being a pharmacist. But the responsibility is with everyone. It starts with the pharmacy technician who takes the medication at the drop-off, to the pharmacist that provides the review, through to the collaboration between the pharmacist and the nurse or the physician to discuss any questions that may arise. From a culture standpoint, there are protocols in place for continuous evaluation and quality improvement within the pharmacy. Each institution has their own methods for ensuring that the staff is well-trained and comfortable performing their duties, that there's appropriate automation and technology, and the environment is distraction-free. And then, of course, there are tools that community pharmacies use to continue enhancing that safety culture. AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] has a community pharmacy survey, Community Pharmacy Survey on Patient Safety Culture , that's intended for pharmacy sites to evaluate their approach to safety. It is a self-critique of sorts and asks, “How can I learn from my staff? How can I learn from my patients?” For improving that safety process, ISMP has a self-assessment for community pharmacies as well, outlining different elements of the medication use system to help improve and prevent errors. Then there are even voluntary accreditations for pharmacies. ASHP has an accreditation standard for community and outpatient pharmacy practices with an entire section dedicated to medication safety, patient safety, and supporting continuous quality improvement. So, I think it's an ongoing process, regardless of your setting, establishing that culture to ensure that anyone who touches any aspect of care regards the patient’s safety as a top priority.

KH: So, what would you say are the biggest challenges to safety in the community pharmacy space?

GL: Every community pharmacy operates a little differently and the patient populations and services they offer also vary, but I think if you're speaking generally about common challenges we see in the community-based setting, I would say time available for conducting patient-related services. Again, ISMP has looked at errors that relate to the time the pharmacist has available to review and dispense the medication. and it's clear that pushing for higher volumes and faster dispensing and introducing multiple interruptions creates a risk. Another big challenge for community-based practitioners is that reimbursement is tied to the dispensing, not the clinical services that are so crucial to the safety. This means that the time the pharmacist spends conducting the therapeutic review, clarifying questions with the provider, and talking to the patient are not covered by reimbursement. This limits the availability that you have as a pharmacist.

Then you have interoperability concerns. Having access to patient information is extremely important for ensuring that community pharmacies are able to appropriately conduct a profile review, screen for allergies, do that therapeutic screening that we discussed earlier. If you're tied to a clinic or hospital, you might have access to the patient's direct chart or patient records, which allows you to do a more comprehensive review. However, unfortunately, that's not the case for most of our community pharmacies, who may have to piece it together and spend the extra time calling the nurse line and trying to get a hold of the physician, which I think brings us to a third challenge, which is access to the providers. This again affects the timing and safety of working with patients. In a clinic or health system, you might have a direct line of communication with providers when issues arise. That becomes more challenging in community settings where a pharmacist has to spend a significant amount of time trying to access the prescriber and there's no standard way to communicate with every provider. But overall, when you think about patient safety, it's important to remember it’s not just about the dispensing, it’s about the service provided, and it's about assessing the overall care and the overall system to ensure that safety is in place. Community pharmacies are great at continuous quality improvement as a gold standard. They keep looking at the issues and they keep evaluating what's going right and what's going wrong, in order to continue improving.

KH: You know, it seems that having continuity is something that I keep hearing in what you're saying in terms of having good communication with providers, with the patients. With transitions of care, could we talk a bit about those pharmacies that are part of health systems and their role in care transitions?

GL: I think every pharmacy has an extremely important role in care transitions. Ultimately, we talked about community pharmacies being the final safety net for that patient before they go home with a medication. But going back to the issues that we mentioned, interoperability is a huge component of being able to perform safe transitions. In an ideal world, what we would like to see is all community pharmacists having access to patient records and being able to review medication profiles, have access to providers, and document their interventions. Think about care as a feedback loop versus silos of care. Community pharmacies have a tremendous role to play because they often have the most touch points with the patient. At times they see patients on a weekly basis. So that's an opportunity for education, an opportunity for further clarification, an opportunity to look at the patient and evaluate, how's your adherence? Are you comfortable with your therapy? Can you afford your medication? These are all factors that play into patient safety. We could do everything right and then that patient goes home and doesn’t understand their therapy and doesn’t adhere to the therapy and then we're back to non-optimized use, not because anything went wrong with the diagnosis or anything went wrong with the actual care of the patient, but because they just didn't understand how to appropriately utilize their treatment. So, care transitions are critical in ensuring patient safety, and community pharmacies are really important in helping establish those relationships with providers and with patients and avoiding those mistakes.

KH: Are there any tools available for pharmacies that are not part of the system where the patient usually gets care? Or is it a reliance on the use of interoperable computer systems?

GL: There are definitely ways to ensure patient safety, no matter if you're part of an integrated system or a part of a stand-alone pharmacy. For a pharmacy provider who works in a community setting that may not have access to the electronic health record, or may not have direct access to the provider, there's still the responsibility of taking care of the patient. Professional education in these instances is so important, ensuring that you're up to speed with the latest treatment guidelines and understanding the appropriateness of therapy from your clinical expertise. The pharmacy team has the responsibility to serve as a patient advocate and communicate on behalf of the patient. The team also participates in quality reviews, looking at where errors happened, and collecting data that can be presented both to their institution, but also to collaborative organizations or collaborative practitioners and say, “Hey, we're seeing that these are the errors that are occurring, how can we work together to improve them? How can we collaborate better?” Most errors are related to system gaps, not individual providers, so constant reassessment of the processes is key.

Engaging patients in their own care is really important because ultimately, the patient can give you more information than anybody else. Maybe they can connect you directly to their provider, or maybe they can provide you more information about where the confusion arises. From the patient’s standpoint, they, or their caregivers, need to ensure they are actively involved in their own care and advocate for their own needs. Ensure that they understand why a medication change was made to their treatment. Sometimes patients are afraid to ask, but it's really important to talk with their pharmacist, talk with their provider, and understand why changes are being made so an error can be prevented, and medication use can be optimized. It also allows the development of trusting relationships with providers. We often hear the term “pharmacy hopping.” But it is important to establish long-term relationships with one pharmacist, one primary provider, and consistent specialists. This brings continuity to your care and goes a long way in preventing errors.

KH: Are there formal mechanisms by which pharmacists and clinicians whose patients are coming to them can communicate about patterns or trends?

GL: It goes back to the ongoing patient safety monitoring and the error reports that pharmacists review. A really strong, ongoing safety program is documenting errors or near-misses. There are many different documentation forms out there- one is called Assess-ERR™, and it guides you through how to document the error or near-miss to understand what type of error was it? What kind of medication did it involve? What were the circumstances around it? So, when the pharmacist or administrator reviews these documents, they can look at trends and determine if something is a one-off mistake or a pattern. Sometimes there could be a systems issue that requires staff education or updating a policy or process. Or it could be we're seeing a recurring misunderstanding from a provider warranting a call or clarification. So that's why that continuous quality improvement process is so important, because it looks at errors not only in an isolated incident, but trends over time, and identifies internal and external opportunities in a more formalized way.

KH: How is that feedback provided? Is it provided directly to those involved? Is it provided back to the safety group at the hospital? How do you to make sure that you get the information to the right people?

GL: It depends on the circumstances. If it's a prescribing or dispensing trend like we talked about earlier, then that would be a communication with the specific provider’s office or mak[ing] an internal change to the system or process. But if it is a transitions-of-care concern that you find, such as a medication missed at discharge, the pharmacist would call the discharge facility to confirm whether there was, in fact, an error or if it was intentional, and then make the changes with the provider. So, it's all on a case-by-case basis, depending on what type of error you're seeing. Overall, the complete medication review is that key component that happens before the patient goes home to ensure that all medications are correct.

KH: Is there anything that you think we should cover that we've missed or anything additional around patient safety in this setting?

GL: I think talking about some of the changes that are on the horizon that are helpful in planning for patient safety would be good to cover. From an operational standpoint, there's an effort to provide broader access to key providers and ensure that community pharmacists everywhere have access to the health information data that they need. CMS [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] is working to build out a roadmap for electronic exchange of data and e-prescribing to avoid errors and help with more communication and integration. There are also groups like the Pharmacy HIT [Health Information Technology] Collaborative that advocate for integrated networks of care. And then similarly, CPESN [Community Pharmacy Enhanced Services Network] is working to encourage community pharmacies’ involvement in providing enhanced patient care services. So, from an interoperability standpoint, there's a lot of action because we realize it's so important to communicate with one another. We're also seeing consistent use of technology to avoid errors, like barcode scanning and clinical decision support tools. These [technologies] catch errors that maybe the provider might not. We're also seeing innovative partnerships between settings to promote safety. For example, we're seeing partnerships between health systems and community-based pharmacies, creating collaborations for care transitions. Lastly, we mentioned some barriers with the time available for dispensing and clinical services, such as patient education. There is a push for regulatory change right now in recognizing pharmacists as providers and reimbursement for both dispensing and for other clinical responsibilities, such as counseling. The important thing to recognize is that community pharmacists do so much more than dispense medication.

1. National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Face-to-face with community pharmacies. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.nacds.org/pdfs/about/rximpact-leavebehind.pdf

2. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Improving medication safety in community pharmacy: Assessing risk and opportunities for change. 2009. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-02/ISMP_AROC_whole_document.pdf

This project was funded under contract number 75Q80119C00004 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors are solely responsible for this report’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. None of the authors has any affiliation or financial involvement that conflicts with the material presented in this report. View AHRQ Disclaimers

Perspectives on Safety

Perspective

WebM&M Cases

Annual Perspective

Ensuring medication reconciliation. December 19, 2007

After his wife died, he joined nurses to push for new staffing rules in hospitals. March 6, 2024

Rx for a better prescription. Hospital bans doctors from using confusing medical abbreviations. October 5, 2005

The First Annual HealthGrades Pediatric Patient Safety in American Hospitals Study. August 25, 2010

HealthGrades Eighth Annual Patient Safety in American Hospitals Study. March 23, 2011

Patient Safety: Research into Practice. September 13, 2006

Insurers' Medical Loss Ratios and Quality Improvement Spending in 2011. April 10, 2013

Safety in Numbers: Evidence-based Development of a Medicine Management Learning Tool. May 22, 2013

Sustaining Improvement. July 20, 2016

Achieving the Promise of Health Information Technology: Improving Care Through Patient Access to Their Records. October 7, 2015

Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. Updated edition. March 27, 2005

Improving the Reliability of Health Care. February 8, 2006

Adult Hospital Stays with Infections Due to Medical Care, 2007. September 15, 2010

You can't understand something you hide: transparency as a path to improve patient safety. July 8, 2015

Silence Kills: The Seven Crucial Conversations for Healthcare. March 6, 2005

Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: 2018 User Database Report. April 4, 2018

Quality and Safety Education. August 12, 2009

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses. June 13, 2007

To ask or not to ask?: the results of a formative assessment of a video empowering patients to ask their health care providers to perform hand hygiene. February 10, 2010

Health Information Technology in the United States: The Information Base for Progress. October 25, 2006

Impact of the Care Quality Commission on Provider Performance: Room for Improvement? November 21, 2018

Improving Diagnosis. November 28, 2018

AHRQ Nursing Home Survey on Patient Safety Culture: 2016 User Comparative Database Report. November 23, 2016

Patient Safety in Ambulatory Settings. November 2, 2016

Obstetric Care Consensus No. 5: Severe Maternal Morbidity: Screening and Review. May 9, 2018

With Safety in Mind: Mental Health Services and Patient Safety. September 6, 2006

Magnet in Support of Patient Safety. November 26, 2014

The English Patient Safety Programme. February 10, 2010

Leadership Guide to Patient Safety: Resources and Tools for Establishing and Maintaining Patient Safety. September 28, 2005

Advancing Patient Safety: Reviews From the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Making Healthcare Safer III Report. September 2, 2020

A simple surgery with harrowing complications. August 8, 2012

The 2019 John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards. July 8, 2020

The 2014 John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards. May 6, 2015

Characteristics of Weekday and Weekend Hospital Admissions, 2007. March 17, 2010

Guide for Developing a Community-Based Patient Safety Advisory Council. October 3, 2007

Whistle-blowing nurse is acquitted in Texas. February 24, 2010

Risky business: James Bagian—NASA astronaut turned patient safety expert—on being wrong. July 14, 2010

Getting Your Best Health Care: Real-World Stories for Patient Empowerment. April 27, 2011

Latex: a lingering and lurking safety risk. April 4, 2018

Surviving a bad diagnosis. September 28, 2016

Prevention of perioperative medication errors. March 17, 2023

The star of the diagnostic journey: assessing patient perspectives. November 28, 2018

Hospitals may be the worst place to stay when you're sick. March 14, 2012

For second opinion, consult a computer? December 12, 2012

Drug shortages persist in US, harming care. November 28, 2012

The hidden dangers of outsourcing radiology. November 30, 2011

Speaking up for safety—it’s not simple. October 3, 2018

Why are so many women being misdiagnosed? August 30, 2017

Is the future of medical diagnosis in computer algorithms? May 29, 2019

Mother says ER misdiagnosis leads to son's death. December 4, 2013

Healthcare 411: medication safety toolkit. March 18, 2009

Kaiser learns from tragic medical errors. June 4, 2008

Do no harm: promoting patient safety. September 28, 2005

What pilots can teach hospitals about patient safety. November 8, 2006

Doctors say 'I'm sorry' before 'See you in court.' May 28, 2008

Your hospital's deadly secret. March 12, 2008

Hospitals put emphasis on collection of medication data. August 30, 2006

Hospital design plays important role in patient outcomes. April 27, 2005

Measuring shared mental models in healthcare. November 7, 2018

2018 John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards. July 17, 2019

Contributions from Ergonomics and Human Factors. November 17, 2010

Patient Safety Papers. November 22, 2006

The fading art of the physical exam. September 29, 2010

US drug shortages threatening those whose lives depend on crucial remedies. May 18, 2011

Doctors could learn something about medical handoffs from the Navy. May 4, 2011

Leading High-Reliability Organizations in Healthcare. May 4, 2016

Freedom to Speak Up: A Review of Whistleblowing in the NHS. May 27, 2015

Medical errors in dentistry. November 4, 2015

Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust: Public Inquiry. February 20, 2013

The best medicine for fixing the modern hospital. December 12, 2012

The drawbacks of data-driven medicine. June 26, 2013

New system for patients to report medical mistakes. October 3, 2012

ISMP Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Community Pharmacy. April 19, 2023

Defining and enhancing collaboration between community pharmacists and primary care providers to improve medication safety. February 22, 2023

ASHP Guidelines on Preventing Diversion of Controlled Substances. December 14, 2022

Concerns regarding tablet splitting: a systematic review. December 7, 2022

Medication adverse events in the ambulatory setting: a mixed-methods analysis. October 26, 2022

Community Pharmacy Survey on Patient Safety Culture. October 24, 2022

Disrespectful behavior in your workplace. April 13, 2022

Pharmacy Education and Practice. January 26, 2022

Medication safety issues with newly authorized PAXLOVID. January 12, 2022

Mix-ups between the influenza (Flu) vaccine and COVID-19 vaccines. October 20, 2021

Important Actions Community Pharmacists Need to Take Now to Reduce Potentially Harmful Dispensing Errors. October 26, 2021 - October 26, 2021

Medicine self-administration errors in the older adult population: a systematic review. June 9, 2021

Medication incident recovery and prevention utilising an Australian community pharmacy incident reporting system: the QUMwatch study. May 5, 2021

Drug shortages amid the COVID-19 pandemic. February 24, 2021

Pharmacist counseling when dispensing naloxone by standing order: a secret shopper study of 4 chain pharmacies. December 9, 2020

Wrong drug and wrong dose dispensing errors identified in pharmacist professional liability claims. November 4, 2020

Fighting against COVID-19: innovative strategies for clinical pharmacists. May 6, 2020

Pharmacist linkage in care transitions: from academic medical center to community. October 30, 2019

Special Issue on Prescription Drug Misuse. September 25, 2019

Community pharmacy medication review, death and re-admission after hospital discharge: a propensity score-matched cohort study. September 4, 2019

Ten ways to improve medication safety in community pharmacies. August 7, 2019

Impact of medication reviews delivered by community pharmacist to elderly patients on polypharmacy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. June 26, 2019

Effect of a central call center on employee perceptions of safety culture within community pharmacies in an academic health system. June 5, 2019

Patient Safety. May 22, 2019

Connect With Us

Sign up for Email Updates

To sign up for updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address below.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 Telephone: (301) 427-1364

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Electronic Policies

- HHS Digital Strategy

- HHS Nondiscrimination Notice

- Inspector General

- Plain Writing Act

- Privacy Policy

- Viewers & Players

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- The White House

- Don't have an account? Sign up to PSNet

Submit Your Innovations

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation.

Continue as a Guest

Track and save your innovation

in My Innovations

Edit your innovation as a draft

Continue Logged In

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation. Note that even if you have an account, you can still choose to submit an innovation as a guest.

Continue logged in

New users to the psnet site.

Access to quizzes and start earning

CME, CEU, or Trainee Certification.

Get email alerts when new content

matching your topics of interest

in My Innovations.

The Future of Community Pharmacy: Direct Patient Care

Community-based pharmacy is evolving from a place of product distribution into a healthcare destination.

By Athena Ponushis and Nidhi Gandhi, Pharm.D.

Many pharmacists who spend time filling prescriptions keep hearing of a future where their role will be more focused on the patient, not the product. It’s anticipated that their attention will shift from dispensing to providing convenient clinical care. Some forward-thinking pharmacies are already enabling pharmacists to live in this awaited world, helping patients manage their medication experience and documenting interventions. These pharmacies are sharing their innovative models and schools are studying the impact, providing a window into the future of community-based pharmacy practice.

Picture pharmacists having routine interactions with patients to review, optimize and synchronize medications rather than just episodic or transactional meetings at the counter. Pharmacists will collaborate with primary care practices as part of an integrated healthcare team, making recommendations on one shared medical record, reinforcing patient care plans. Patients who want care on demand go to their pharmacists for point-of-care testing, immunizations and travel consults, or prescriptions for contraception, smoking cessation and HIV prevention. Imagine pharmacogenomic screenings being commonplace, as pharmacists look at genetics to predict drug response and tailor treatments. So goes the perceived evolution of community-based pharmacists, from performing clinical interventions to becoming initial clinicians, ushering in a time when community pharmacies are considered essential to the healthcare landscape.

“We are training our student pharmacists for the future and this is the future we see,” said Linda Garrelts MacLean, interim dean, clinical professor of pharmacotherapy at Washington State University College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “I believe that community pharmacies are going to be the place where care is delivered, that access to the learned intermediary, someone who can assess, evaluate, prescribe when appropriate and even more importantly, refer when necessary.”

Washington state has been progressive on a number of pharmacy fronts since the 1970s. MacLean and Dr. Julie Akers, clinical associate professor of pharmacotherapy at WSU, are finalizing a study on the effectiveness of pharmacy treatments, comparing the care pharmacists provide for minor illnesses and self-limiting conditions to what is offered at more traditional settings, such as physician offices, urgent care centers or hospital emergency departments. The study will inherently set a baseline to measure how enhanced pharmacy services are influencing quality of care and access to care.

Once analyzed, MacLean believes the study will provide evidence that community pharmacists can contribute to caring for patients, compelling other states and pharmacies to replicate services and treat common ailments such as strep throat, urinary tract infections and severe headaches, including migraines. Akers has found, through surveys and anecdotally, that patients are confident in receiving care from pharmacists. It may take a little education (patients don’t always know what training pharmacists have had or what services are being offered) but once they know, Akers has not seen any hesitation in a patient’s willingness to be seen by a pharmacist.

“More involved direct patient care is the future of pharmacy practice, and schools need to ensure that they are graduating practice-ready pharmacists who are prepared to move into that role. Schools should take the time to fully assess their curriculum, making sure it is robust enough to where they are going to have pharmacists who are confident and ready to go start these services,” Akers said. “Also ensuring that they are building strong advocacy with their students so that as students want to move toward this future, they understand the legislative and regulatory framework of what they are allowed to do within their state and how to overcome any barriers.”

At WSU, student pharmacists take an intensive, weeklong, point-of-care and clinical services course at the beginning of their second year. Rather than re-create the material the state pharmacy association had created for continuing education for practicing pharmacists, faculty collaborated with the association, giving students access to online modules that they complete over the summer before school begins. Students spend the entire first day of class going condition by condition, reviewing key guidelines through patient cases, deciding whether to use prescriptive authority, refer to a more advanced care setting or recognize that over-the-counter self-care products are appropriate for that case.

“What I find interesting is that prior to this course, our students have completed their over-the-counter self-care pharmacotherapy course, and in that course it’s over-the-counter or refer because the patient needs a prescription. So it’s always comical when we’re doing these patient cases that the students’ automatic response is, ‘We have to refer because that’s what we’ve learned before.’ It’s changing that mindset for them, realizing that as an advanced care practitioner pharmacist, you can handle some of these minor illnesses and conditions with prescriptive authority,” Akers said.

Other days are dedicated to immunizations. Students are certified in immunization administration and receive specialty training on pediatric immunization. Students learn how to screen for HIV, strep and influenza, practicing throat and nasal swabs on themselves or a team member before going through a rubric-graded assessment, ensuring they can collect the sample without it being contaminated. They have open practice laboratory sessions and breakout sessions where they learn how to run a travel consultation, interact with a patient and do the paperwork.

“We began this course after getting approval from our full faculty to move it forward as required curriculum for all of our graduates. That’s what was most important: getting all of our faculty to recognize that we truly believe as a program that this is the future of pharmacy,” Akers noted. “We really believe that this is the base knowledge that’s required for an entry-level pharmacist.”

The Path Forward

In its 2018 report, “The Next Transition in Community-Based Pharmacy Practice,” the American Pharmacists Association found that pharmacists are trained to perform certain tasks but often experience work settings that are not conducive to such practice. The study found that new roles abound for community pharmacists in this “new patient-centered, medication experience era,” but stressed the difference between professional identity and commercial identity. To change perceptions of community pharmacy, the APhA encouraged pharmacists to see transformation “through the patient’s eyes.” From the patient’s vantage point, a medication experience is not clinical, it’s personal.

The Council of Deans formed a task force to find opportunities to improve community-based practice and give viable recommendations to AACP and member institutions to pursue such possibilities and make them realities. The task force chair, Dr. Jennifer Adams, associate dean for academic affairs, director of interprofessional education, clinical associate professor at Idaho State University College of Pharmacy, said the task force will structure recommendations in three separate areas.

First, advancing pharmacy technician practice. Pharmacists must have good support staff if they are going to take on new roles, so elevating pharmacy technicians is crucial. “What are the types of tasks pharmacy technicians can do? What can we train them to do if they don’t already have that level of training, and what’s appropriate there, in terms of scope? What needs to be reserved for pharmacists?” Adams asked. “The way Idaho has tackled this is really from the perspective of delegating, allowing pharmacists to delegate tasks to technicians as long as those tasks are appropriate for their education, training and experience.” An example would be immunization administration. Determining if it’s the right immunization for that patient at that time would be the responsibility of the pharmacist, but the actual administration could be done by a technician. Same with point-of-care testing: the pharmacist would decide to do the test but the technician could administer it. Some pharmacies are delegating the accuracy checking of the dispensing process to technicians. “Data show that when they are delegated that task and given that authority, pharmacy technicians are actually more accurate than pharmacists because they tend to have fewer distractions,” Adams added.

Second, advancing the scope of pharmacy practice. “Our university has been closely involved with our board of pharmacy and our state association and we have navigated relationships with legislators to advance scope of practice,” Adams said. The Idaho board looked at other boards of pharmacy, but also looked at medicine and nursing, examining how their licensees were regulated and found they regulate based on this concept of standard of care.

“What our board of pharmacy learned from our healthcare colleagues was, pardon the pun, but pharmacists tend to be really prescriptive in their regulations. We write out the exact details of how hot the water in the pharmacy needs to be, the amount of counter space that needs to be provided, we get way into the weeds, rather than saying the facility needs to be appropriate so that the practitioners in the facility can provide the appropriate standard of care,” Adams said. “So there is nuance, and sometimes it’s unnerving for pharmacists to begin to think that way, but our board of pharmacy in Idaho has shifted all of our regulation to a standard of care model, which allows pharmacists to practice at the top of their education and training and not be restricted by their license.”.

More involved direct patient care is the future of pharmacy practice, and schools need to ensure that they are graduating practice-ready pharmacists who are prepared to move into that role.

Idaho has been the trailblazer for independent prescriptive authority. Pharmacists in Idaho can prescribe based on four parameters: when no new diagnosis is required, when a CLIA-waived test can guide diagnosis, when a condition is minor and self-limiting or in an emergency. At first, the board of pharmacy made a list of medications pharmacists could prescribe for those categories, each year adding new medications to the list for legislators to approve. Legislators saw the same scenario playing out—they would hear opposition from the medical community, give pharmacists a chance and then see the positive outcomes. At the end of the 2019 legislative session, legislators eliminated the list. It’s now up to a pharmacist or pharmacy to determine what fits into those categories.

“One advantage to that is that during a public health emergency like COVID-19, a pharmacy can say, ‘You know what, we are going to do our best to take care of everyone who we want to keep out of urgent care centers and hospital emergency rooms because we want to relieve the burden on the healthcare system, so now we are going to treat acute sinusitis and uncomplicated urinary tract infections,’” Adams said. Several states have passed emergency regulations during this crisis, allowing pharmacists to do more, like extend refills. “My thought is, how better to be prepared for an emergency situation than to have that be what your daily practice is?” Adams pointed out. “If I am already doing these things and I am already taking care of patients at this level, it’s not such a stressful shift for me in an emergency.”

Third, the task force will provide recommendations to advance payment reimbursement for services. Idaho was successful in adding pharmacists to the list of nonphysician providers in its Medicaid basic plan this year, enabling pharmacists to bill for services based on scope of practice, with no restricted services. Adams believes a groundswell from state Medicaid programs will lead the effort of reimbursement, showing that when you pay pharmacists for services, outcomes improve and costs go down. “The other component the task force has talked about is not trying to create a new or different way for pharmacists to get reimbursed,” Adams said, “but that we fit ourselves in with the way the rest of the healthcare system bills for services.”

My thought is, how better to be prepared for an emergency situation than to have that be what your daily practice is? If I am already doing these things and I am already taking care of patients at this level, it’s not such a stressful shift for me in an emergency.

AACP President Todd Sorensen’s Bold Aim for the profession, that by 2025, 50 percent of primary care physicians in the U.S. will have a formal relationship with a pharmacist, prompted the 2020 Professional Affairs Committee to present a policy recommendation that will be considered by the 2020 AACP House of Delegates. The committee is also developing a survey tool, a database of successful models to serve as a resource for schools and pharmacies. “We want to take a comprehensive approach of looking at how pharmacists can collaborate with primary care practices, from models that we know about and models that maybe we are less familiar with, but helping to disseminate that information to schools, identifying the needs for these collaborations and ways to build sustainable models,” said Dr. Gina Moore, assistant dean for clinical and professional affairs, associate professor, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy, and chair of the committee.

Schools are the thread running through all the recommendations, bringing people together, doing the research and engaging in advocacy to advance community-based practice. “We must share our success stories, not just within pharmacy, but with other audiences, including physicians, professional organizations and the public,” Moore said. “We must share the benefits of collaborating with community pharmacists.”

A Model to Unite, Mobilize and Amplify

Americans have access to more than 62,000 community pharmacy locations for medication therapy management, immunizations and walk-in patient consultations. To adapt to the rapidly evolving value-based healthcare system, the community pharmacy practice model must be transformed into a place for patients to receive comprehensive medication-related care from pharmacists and the pharmacy team.

In July 2019, the Academia-CPESN Transformation (ACT) Pharmacy Collaborative was formed as a nationwide forum where community pharmacy leaders and schools of pharmacy could come together to make the patient-centered vision of community pharmacy a reality. The goal of this collaborative is to support the transformation of community-based pharmacy practice from a product-based care model to a community-based pharmacy care delivery model, focusing on the enhanced services that support people who are taking medications to help them reach their health goals. Some examples of enhanced services include clinical medication synchronization, medication reconciliation, comprehensive medication management, durable medical equipment evaluation and support, point-of-care testing, travel immunizations and travel medication consultations.

The establishment of the ACT Pharmacy Collaborative came as a result of a grant from the Community Pharmacy Foundation to the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy in partnership with CPESN USA. The Collaborative, with support from AACP, has three main drivers: to unite, mobilize and amplify community pharmacy practice transformation with colleges/schools and community pharmacy partners nationwide. A full description of the Collaborative and how colleges/schools can be involved can be found in the “Blueprint for Building a National Partnership Collaborative” on the ACT Pharmacy Collaborative’s centralized website (www.actforpharmacy.com).

Dr. Sophia (Cothrel) Herbert is a Community Pharmacy Practice Development Fellow within the Community Leadership and Innovation in Practice Center at the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy and works to support the transformation of community pharmacy practice. She serves as the Pennsylvania Flip the Pharmacy Team Project Manager, also funded by the Community Pharmacy Foundation, and is a member of the leadership team for the ACT Pharmacy Collaborative under the mentorship of professors Kim Coley and Melissa McGivney. Within her research initiatives with community partners, she mentors student pharmacists for research and quality improvement projects.

The University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy recently created a community pharmacy practice-based research network to support ongoing practice transformation in Pennsylvania. Herbert noted, “The idea behind the network is to engage community pharmacists who are willing and able to perform practice-based research in collaboration with patients and research partners. There will continue to be a focus on stakeholder engagement in all network activities.”

For Herbert, community pharmacy means “patient access to care within their own communities. There is a successful future for community pharmacies that strive to meet the medication and other health needs of their patients, within their own communities where they live, work and play,” she said. “The combined efforts of the ACT Pharmacy Collaborative, Flip the Pharmacy and CPESN are driving community pharmacy practice toward a patient-centered care model, and the combination of these forces and efforts will bring us closer to that vision of community pharmacies providing optimal patient care.”

During her fellowship, Herbert has worked on several projects involving student pharmacist participation through the ACT Pharmacy Collaborative such as the National Day of Service, Patient Case Challenge, CPESN/ACT Student Scholar program and CPESN/ACT Student Match program, which facilitates student experiences at community pharmacies across the country in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. “I have been most excited about facilitating student connections and experiences through these initiatives, especially the CPESN/ACT Student Scholar program that will allow selected students to interact with and learn from community leaders and CPESN practices in an impactful way,” she said.

Athena Ponushis is a freelance writer based in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. Nidhi Gandhi is the Academic Leadership and Education Fellow at AACP

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 21 July 2011

Public health in community pharmacy: A systematic review of pharmacist and consumer views

- Claire E Eades 1 ,

- Jill S Ferguson 2 &

- Ronan E O'Carroll 1

BMC Public Health volume 11 , Article number: 582 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

57k Accesses

315 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

The increasing involvement of pharmacists in public health will require changes in the behaviour of both pharmacists and the general public. A great deal of research has shown that attitudes and beliefs are important determinants of behaviour. This review aims to examine the beliefs and attitudes of pharmacists and consumers towards pharmaceutical public health in order to inform how best to support and improve this service.

Five electronic databases were searched for articles published in English between 2001 and 2010. Titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher according to the inclusion criteria. Papers were included if they assessed pharmacy staff or consumer attitudes towards pharmaceutical public health. Full papers identified for inclusion were assessed by a second researcher and data were extracted by one researcher.

From the 5628 papers identified, 63 studies in 67 papers were included. Pharmacy staff: Most pharmacists viewed public health services as important and part of their role but secondary to medicine related roles. Pharmacists' confidence in providing public health services was on the whole average to low. Time was consistently identified as a barrier to providing public health services. Lack of an adequate counselling space, lack of demand and expectation of a negative reaction from customers were also reported by some pharmacists as barriers. A need for further training was identified in relation to a number of public health services. Consumers: Most pharmacy users had never been offered public health services by their pharmacist and did not expect to be offered. Consumers viewed pharmacists as appropriate providers of public health advice but had mixed views on the pharmacists' ability to do this. Satisfaction was found to be high in those that had experienced pharmaceutical public health

Conclusions

There has been little change in customer and pharmacist attitudes since reviews conducted nearly 10 years previously. In order to improve the public health services provided in community pharmacy, training must aim to increase pharmacists' confidence in providing these services. Confident, well trained pharmacists should be able to offer public health service more proactively which is likely to have a positive impact on customer attitudes and health.

Peer Review reports

Promotion of healthy lifestyles is one of the five core roles of a pharmacist, as defined by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, (RPSGB) [ 1 ]. Although pharmacists have always had some involvement in health improvement, the focus on this aspect has greatly increased over recent years [ 2 ]. This changing role was formalised by the introduction of the new pharmacy contract in 2005 in England and Wales and 2006 in Scotland which outlined the public health service pharmacists would be required to provide. These services include provision of advice on healthy living and self care and involvement in health promotion campaigns in Scotland, England and Wales with the additional requirement to provide a smoking cessation and sexual health service in Scotland [ 3 , 4 ].

Community pharmacy holds a number of benefits as a setting for public health activities. With extended opening hours and no appointment needed for advice, community pharmacy can be more accessible than other settings. An estimated 600,000 people visit community pharmacies in Scotland every day and approximately 94% of the Scottish population visit a community pharmacy at least once in a year [ 5 ]. This gives community pharmacies access to a range of individuals in both good and poor health, and to those that may not have contact with any other health professionals. Reviews of evidence assessing public health initiatives in community pharmacy have confirmed the potential of pharmacy in this area and suggest that pharmacists can indeed make a positive contribution to public health [ 6 , 7 ].

Although there is clear potential for pharmacy to contribute in a unique way to public health, changes in the behaviour of both pharmacists and pharmacy customers are likely to be required for the service to be successful. Pharmacists must accept their role in public health and make the necessary changes in behaviour to carry out the service. Similarly, the general public must accept pharmacists as providers of public health services and be willing to seek advice on some health issues from pharmacists rather than other sources.

The factors that affect and predict behaviour have been the subject of a great deal of research. The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is a model that has been widely used to predict and change behaviour across a range of settings [ 8 ]. The model states that voluntary behaviours are largely predicted by our intentions regarding the behaviour. Intentions are in turn determined by our attitude towards the behaviour (our judgement of whether the behaviour is a good thing to do), subjective norms (our judgement of what important others think of the behaviour), and perceived behavioural control (our expectation of how successful we will be in carrying out the behaviour). A review by Sutton found that on average the TPB predicted between 40 and 50% of the variance in intention and between 19 and 38% of the variance in behaviour [ 9 ]. While theories such as the TPB cannot entirely predict behaviour, these findings demonstrate the important role of beliefs in understanding behaviour.

Therefore, in order to understand and assist the behaviour changes associated with providing a public health service in community pharmacy, it is important to establish the beliefs of the general public and pharmacists regarding this role. Three systematic reviews have previously been carried out in this area. One assessed pharmacist views and another general public views towards various public health services [ 10 , 11 ]. The third reviewed papers on the provision of emergency hormonal contraception (EHC) in pharmacy and included public and pharmacist views [ 12 ]. The review of pharmacists' perceptions of public health covered literature published up to 2001 and found that although pharmacists valued the health improvement role they were more comfortable with medicine related health improvement work [ 10 ]. The review also found that pharmacists had concerns about being intrusive and believed they needed more support to provide public health services. Training was found to positively affect pharmacists' attitudes and behaviours in relation to health promotion [ 10 ].

The review on consumer views covered literature up to 2002 and found that pharmacists were perceived as 'drug experts' rather than experts on health and illness. Although consumers were generally satisfied with health advice given by pharmacists, they primarily used pharmacies for dispensing prescriptions and buying over the counter medication [ 11 ]. The final review summarised literature on the provision of EHC in pharmacy up to the end of 2004. The review reported that the service was largely viewed positively by both pharmacists and service users but that some concerns were raised by consumers regarding privacy [ 12 ].

Since these reviews were conducted, the introduction of the new pharmacy contract has brought about a great deal of change in community pharmacies. In order to continue to improve the public health service provided in community pharmacies, up to date information is needed regarding the beliefs and attitudes of pharmacists and consumers towards pharmaceutical public health. Beliefs about the public health role may or may not be similar to those found in the previous review. Establishing current views would allow potential barriers to the public health service to be established and appropriately tackled. The objective of this review is to summarise and evaluate quantitative and qualitative evidence published since the previous reviews were conducted on the beliefs and attitudes of pharmacists and consumers towards pharmaceutical public health.

The electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Dissertation Abstracts International were searched for articles published in English from February 2001 to February 2010. The following combination of search terms was used with each database: (pharm* or pharmacy staff or community pharmacy or consumer or public or customer) and (attitud* or belie* or perce* or knowledge or view or opinion) and (public health or health improvement or health promotion or self care or self management or smoking cessation or sexual health or prevent* or diet or healthy diet or healthy eating or exercise or physical activity or weight or health education or chlamydia testing or emergency contraception or alcohol or needle exchange or methadone or injecting equipment or drug misuse).

Titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria outlined in table 1 . Full text papers were retrieved for studies considered relevant and for those with titles and abstracts that contained insufficient information to allow judgement of relevance. The full text papers were assessed against the inclusion criteria by one researcher and those identified as relevant were checked again by a second researcher. Data were extracted from included studies using a data extraction form based on the example provided by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [ 13 ]. In order to assess methodological quality, studies were assessed against the checklist outlined by Crombie which is suitable for use with descriptive surveys [ 14 ]. The methodological quality of qualitative studies was assessed against the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative studies [ 15 ].

Literature Search

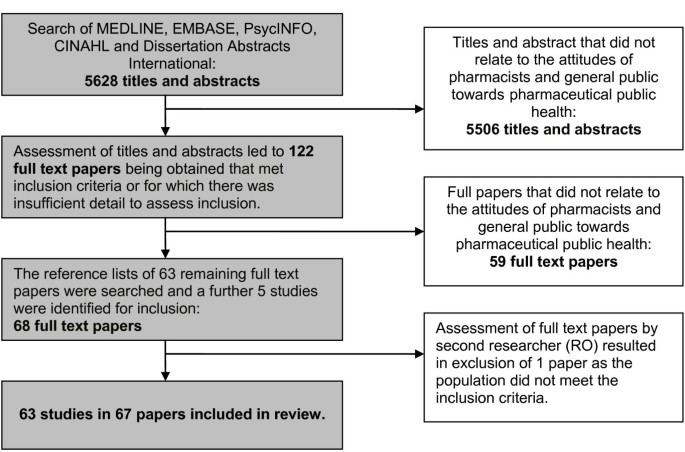

A total of 5628 abstracts were reviewed and 122 full text papers were assessed against the inclusion criteria outlined in Table 1 . A second researcher assessed the 71 papers shortlisted for inclusion and 63 studies published in 67 papers were included for review. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies identified by the searches.

Flow diagram of searches and inclusion assessment of studies .

Description of Included Studies

The characteristics of the studies included in the review are presented in additional file 1 . The majority of studies assessed the views of pharmacists (n = 29), support staff (n = 3) or both (n = 1). Three studies investigated both pharmacist and general public views and the remaining studies assessed the views of the general public or pharmacy customers (n = 27). The most common topics investigated were sexual health services (n = 17), smoking cessation (n = 14), general health promotion/screening (n = 12), and services for drug misusers (n = 10). The majority of studies were carried out in Europe (n = 31) and North America (n = 23). The most commonly employed methodology was surveys (n = 50). Eight studies used structured or semi-structured interviews, two used focus groups and two studies used both focus group and survey methods. Table 2 outlines the country of publication of papers included in the review sorted by topic area. It shows the proportion of UK and non-UK papers published after the introduction of the new pharmacy contract in the UK (2006 to 2010).

Quality of Included Studies

Quality varied across the studies included. The quality of reporting was often poor with 16 studies not reporting any information on the age of participants [ 16 – 35 ], 8 not reporting age or gender [ 36 – 43 ] and 2 not reporting gender [ 44 , 45 ]. Fifteen studies did not report response rates [ 17 , 25 , 29 , 43 , 46 – 56 ] and two only reported the response rates for part of the sample [ 57 , 58 ]. Only three studies followed up a sample of non-responders [ 59 – 61 ]. Response rates where reported were generally average to good with the majority (71%) achieving response rates of 50% and over. The way participants were recruited was not clearly reported in one study [ 50 ] and the results were not adequately explained in another [ 62 ]. In the latter case, the names of themes arising from the analysis of interviews were stated with little explanation of the direction of opinion of pharmacists in relation to these themes. The majority of studies included in the review employed convenience sampling (n = 29), 5 used purposive sampling [ 41 , 56 , 62 – 64 ] and only 13 used random sampling methods [ 16 , 18 , 32 – 38 , 47 , 50 , 58 , 65 – 68 ]. Of the 12 studies included that used qualitative methodologies only one employed respondent validation [ 62 ] or made a statement of how the personal characteristics of the researchers may have influenced analysis [ 69 ]. Methods and analysis were not adequately described in one study [ 43 ], data was not transcribed verbatim in another study [ 70 ] and multiple coding was not used in two further studies [ 41 , 51 ].

- Pharmacy Staff

The attitudes and beliefs of pharmacists and pharmacy staff investigated in the papers included in this review related to four main topics: perceptions of role, competence/confidence, barriers and training.

Perceptions of Role

The majority of participants in a survey in Scotland agreed (63%) or strongly agreed (16%) that public health is important to their practice and a little over half agreed (48%) or strongly agreed (8%) that they were public health practitioners [ 21 ]. A survey in Nigeria also reported that the majority of participants (94%) thought it was acceptable for pharmacists to be involved in health promotion activities [ 71 ]. Pharmacists and support staff taking part in focus groups in Sweden on the whole welcomed their role as a health promoter [ 56 ]. However, it was noted that not all participants felt this way and preferred to develop activities in areas in which they received their basic training. Consistent with this, a study in Moldova found that participants rated public health activities significantly lower in importance than all other aspects of professional practice assessed (e.g. dispensing activities) [ 65 ]. Furthermore, a survey in Scotland offering participants a choice of hypothetical jobs found that participants would rather provide a minor illness service than health promotion advice and would forgo £2798 of income to do this [ 72 ].