- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 11 March 2021

Attitudes and awareness of regional Pacific Island students towards e-learning

- Joel B. Johnson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9172-8587 1 ,

- Pritika Reddy 2 ,

- Ronil Chand 2 &

- Mani Naiker 1

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 18 , Article number: 13 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

19 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

This article has been updated

The rise of online modes of content delivery, termed e-learning, has increased student convenience and provided geographically remote students with more options for tertiary education. However, its efficacy relies upon student access to suitable technology and the internet, and the quality of the online course material. With the COVID-19 outbreak, education providers worldwide were forced to turn to e-learning to retain their student base and allow them to continue learning through the pandemic. However, in geographically remote, developing nations, many students may not have access to suitable technology or internet connections. Hence it is important to understand the potential of e-learning to maintain equitable access to education in such situations. This study found the majority (88%) of commencing students at the University of the South Pacific owned at least one ICT device and had access to the internet. Similarly, most students had adequate to strong ICT skills and a positive attitude toward e-learning. These attitudes among the student cohort, in conjunction with the previous experience of The University of the South Pacific in distance education, are likely to have contributed to its relatively successful transition from face-to-face to online learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The use of ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) to deliver educational content and learning support now forms a widespread and accepted norm of many institutes in the higher education sector across the world (Latchem, 2017 ; Sharma et al., 2020 ; Wu, 2016 ). Its growing leverage in developing countries is assisting in bringing the quality, sustainability, accessibility and delivery of education on par with those of the developing countries. The ICT based innovations and tools from the higher education institutes in the developing countries have shown promising and significantly positive results (Reddy et al., 2016 , 2020c ; Sharma & Reddy, 2015 ; Sharma et al., 2019a , 2020 , 2018b ).

Indeed, ICT is now an integral part of most institutes rather than supporting tools (Bhuasiri et al., 2012 ; Irfan et al., 2018 ). The use of e-learning is of particular importance for reaching students in geographically remote locations and improving the equity towards the delivery of education systems (Graham, 2019 ). However, certain barriers remain towards the use of ICT and e-learning as tools for enhancing educational equity (Lim et al., 2020 ; Yang et al., 2018 ). Firstly, some students in remote locations or those living in low socio-economic status (SES) situations may not have access to the appropriate technology or resources required to successfully participate and engage in the e-learning process (Yang et al., 2018 ). For instance, students may not be able to afford equipment such as laptops or desktop computers, or be able to afford internet access plans with sufficient bandwidth and data allowance for video streaming or other data-heavy applications (Chillemi et al., 2020 ). This is more prominent in developing countries such as those in the Pacific region (Reddy et al., 2017 , 2019 , 2020a , 2020b ; Sharma et al., 2018a , 2018b ). Hence in many of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs), government initiatives have been implemented to provide school students with laptops and tablets in order to allow them to access online resources and obtain assistance with their schoolwork (Reddy et al., 2016 , 2017 , 2020b , 2020c ). Similarly, students may only have limited access options for accessing the internet (e.g. through a mobile phone network) (Huang et al., 2017 ), especially in more remote locations (Beinicke & Bipp, 2018 ; Milakovich & Wise, 2019 ), or may be restricted to accessing the internet in certain locations such as local remote campuses and/or education centres, such as in Samoa and Tonga (Reddy et al., 2017 ; Sharma et al., 2019a , 2020 ).

In addition, studies have reported a "digital divide" among students of different socio-economic classes, with primary and secondary students from a low SES background typically having poorer ICT literacy (Scherer & Siddiq, 2019 ), albeit to a lesser degree compared to other domains such as reading and mathematics. It is important to note that this divide is due to differences in their literacy (i.e. familiarity and capability) with ICT devices, not their access to ICT devices per se (Cotten et al., 2014 ). However, in many instances, their lower ICT literacy would likely result from restricted access to e-technology at home or in rural schools in developing countries. Previous surveys show that over 50% of the population in the South Pacific now has access to the internet as a result of improved network infrastructure and the reduced cost of ICT devices (Reddy et al., 2017 ). However, these studies also highlight the variation in device ownership amongst the student population as a result of the financial, social and cultural challenges that exist in the PICs (Raturi, 2018 ; Reddy et al., 2019 ; Sharma et al., 2019a , 2020 , 2019b ). Education institutes and governments across the PICs have attempted to assist the students facing such challenges through interventions such as the provision of one free laptop or tablet per child, and equipping schools with adequate internet connections and computing devices (Sharma et al., 2020 , 2019b ). Similarly, the SchoolNet Project in Samoa and Tonga was funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and implemented by the government to enhance learning outcomes for secondary students and improve knowledge sharing through equitable ICT access (ADB, 2019 ). Nevertheless, despite such assistance from a number of stakeholders, digital literacy in the PICs remains a challenge. One recent study at a regional university in the South Pacific found 73% of the freshmen to have high to very high digital literacy competencies (Reddy et al., 2020d ); whereas another study conducted on high school students in Fiji found 61% to have very low to average competency in digital media literacy. Students will only continue to use digital technology if they have a positive attitude and perception towards technology-enabled learning (Reddy et al., 2020a , 2020d ). In turn, the students will only have a positive attitude towards technology-enabled learning if they possess the competencies needed to use the technology in question (Reddy et al., 2020a ). Hence the advocacy of digital literacy in the PICs has just begun.

However, challenges remain worldwide with the use of e-learning. Students who participate in e-learning may not necessarily receive the same educational benefits as those who enrol in face-to-face classes. It is typically more difficult and time-consuming to ask the lecturer a question through an online forum than in a face-to-face lecture or tutorial situation (Heirdsfield et al., 2011 ). Conversely, it may be more difficult for the educator to explain more complex topics online, where it is more difficult to capture non-verbal aspects used in teaching, such as fine hand gestures or annotations on a whiteboard (Arasaratnam-Smith & Northcote 2017 ; Phirangee & Hewitt, 2016 ). Additionally, a lack of real-time feedback from the students makes it more difficult for the lecturer to tailor their lecture content to suit the class's overall learning style. In other words, most lecturers must significantly transform their teaching style from that which they use in face-to-face classes in order to deliver the content in an online format effectively (Kebritchi et al., 2017 ). Similarly, another issue for content providers is the increased difficulty in designing effective online activities and assessments (Kebritchi et al., 2017 ). This can result in lower student engagement and interaction, combined with an increased chance of online cheating (Olt, 2002 ). From the perspective of both lecturers and students, it is often more of a challenge to build good verbal and non-written communication skills in an online format (Lalande, 1995 ), which are typical graduate attributes sought after by prospective employers. Overall, the failure of educators to meet these challenges may result in a poorer learning experience for their online cohort of students, which in turn has implications for student achievement and student loyalty to their education provider (Pham et al., 2019 ).

Some subjects, such as introductory chemistry units, include teaching certain practical skills to students in order to prepare them for future, more advanced units (Chandra & Sharma, 2018 ; Naiker et al., 2013 ; Naiker & Wakeling, 2015 ; Wakeling et al., 2014 ). This is typically delivered as a compulsory "residential" or "practicum" block for online/distance students, typically ranging from several days to a week in length, rather than the short, weekly lab sessions typically used with on-campus students. However, in many subjects which do not contain a compulsory practical component, gaining hands-on practical experience may still be quite useful for students to solidify their theoretical knowledge and gain greater insight into the practical implications of what they have learnt. For example, this situation is valid for computer programming courses. Such benefits are not available to students studying solely online.

However, online learning is not without its benefits (Chandra & Sharma, 2018 ). In many instances, it provides the students with greatly increased flexibility, allowing them to learn wherever and whenever they want (Hollenbeck et al., 2005 ; Kilburn et al., 2014 ). There are considerable benefits associated with self-paced (Bhuasiri et al., 2012 ), self-directed and personalised learning. In addition to the increased equitable access to education afforded by online learning (Graham, 2019 ), students can replay lectures to solidify their knowledge of the content, and benefit from online peer feedback (van Popta et al., 2017 ) and peer mentoring (Fayram et al., 2018 ). Moreover, there are increasing volumes of high-quality resources, including OERs (open educational resources), available for students undertaking e-learning, even if their host institution does not necessarily provide these resources. Other ventures such as MOOCs (massive open online courses) and diagnostic tools, such as the Online Mathematics Diagnostic Tool (Sharma et al., 2019a , 2020 ) can also increase educational equity for students unable to attend prestigious universities (Gardner & Brooks, 2018 ; Littlejohn et al., 2016 ).

Literature review

The innovations in information and communication technology (ICT) and its integration into the education sector has massively impacted the education process, particularly in higher education. New learning methods such as web-based or Internet-based delivery modes have evolved into a broad range of learning modes, including e-learning, m-learning (mobile learning), tablet-learning and flipped classrooms (Ansong-Gyimah, 2020 ; Reddy et al., 2020b ). In the recent years, e-learning has become one of the most trending learning methods in academia (Bhuvaneswari & Dharanipriya, 2020 ). E-learning has been defined as the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in education which continues to evolve to meet the needs and demands of the students (Bhuvaneswari & Dharanipriya, 2020 ), E-learning involves the use of technology and web platform to create a two-way platform for communication and discussion between students and teachers, where student-to-student discussions enhance social learning, and teachers provide a scaffolded learning experience for students via timely feedback (Layali & Al-Shlowiy, 2020 ), E-learning encompasses a broad set of applications and processes such as computer-assisted learning, web-based training, virtual classrooms and digital collaboration (Kashive et al., 2020 ). is the reason for its popularity results from numerous associated advantages, including (Kashive et al., 2020 ; Layali & Al-Shlowiy, 2020 ; Raturi, 2018 ; Reddy et al., 2020b ):

No limitation of pace and time. Students can access the content and learn at their own speed and time

Promotion of active learning, as students take the lead role in the learning process

Promotion of student-centred, self-directed, interactive, flexible learning

Students are exposed to the use of versatile education tools

Although e-learning comes with a lot of advantages, there are many barriers that the higher education institutes face in the successful facilitation and delivery of e-learning including the network infrastructure, lack of students’ computer competencies, students’ efficacy in using technology for learning, and the potential for miscommunication between students and facilitators (Layali & Al-Shlowiy, 2020 ; Mousavi et al., 2020 ; Rafiq et al., 2020 ). Researchers have also highlighted that since e-learning is closely linked to technology, and because students must use these communication tools for learning, their competency and efficacy in the use of such technology is extremely important (Arshavskiy, 2017 ; Henderson et al., 2017 ; Sakarji et al., 2019 ). Kashive et al. ( 2020 ) and Rafiq et al., ( 2020 ) note that positive perceptions and attitudes of students toward technology is a strong determinant factor in a successful e-learning system. In the context of this study, student “attitude” can be defined as the “knowledge, feeling and action of an individual towards learning with technology or e-learning. Bhuvaneswari and Dharanipriya ( 2020 ) propose that attitude indicates the degree of potential adaptation to technology, and hence a favourable attitude to e-learning would mean that students would be more likely to accept online learning systems. Similarly, in the present study the term “perception” refers to how an individual feel about the use of technology for learning. Previous researchers have proposed that if students perceive that e-learning is useful and helpful to their studies, they will be more likely to accept it (Dospinescu & Dospinescu, 2020 ; Mahajan, 2020 ; Sakarji et al., 2019 ).

Due to the challenges of student acceptance, digital competency and technological acceptance, it could seem at face value that the learning outcomes of students participating solely in online education could be poorer than those engaging in face-to-face learning. However, the jury appears to still be out on whether there are statistically significant differences between the outcomes between these two modes of content delivery. Beinicke and Bipp ( 2018 ) reported that across the entire course content, e-learning was just as effective as in-person learning for procedural knowledge and more effective than in-person learning for declarative knowledge. Baxley ( 2018 ) argued for a more integrative approach, suggesting that online learning can successfully be used to augment face-to-face teaching methods and improve cohort achievement. However, most studies on the quality of e-learning services have been conducted in developed countries (Dursun et al., 2014 ; Machado-Da-Silva et al., 2014 ; Martínez-Argüelles et al., 2013 ) and it is unclear if the same underlying factors and trends would be similar in developing nations (Pham et al., 2019 ).

The South Pacific countries are one such group of developing nations, currently undergoing a technological revolution in order to meet the growing digital demands of the populace (Reddy et al., 2016 , 2020a , 2020c ; Sharma et al., 2019a ). Many higher education institutes in the South Pacific have transited to technology enabled learning to make the learning processes more effective and to meet the demands from the students. However, the phenomena of e-learning in the South Pacific is still developing and there are relatively few studies explored student attitudes and perceptions toward the use of technology, with most studies focused on technology and student acceptance (Raturi, 2018 ; Reddy et al., 2020b ; Sharma & Reddy, 2015 ; Sharma et al., 2020 , 2019b ).

Both the potential and challenges of e-learning were recently highlighted by the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. As a result, education providers worldwide were forced to turn to e-learning and emergency remote teaching within extremely short timespans. For universities with a traditionally predominant face-to-face delivery mode, this has resulted in many challenges as they scramble to transfer their unit content online (Miltiadous et al., 2020 ). Nevertheless, with forced campus closures due to local governmental policies, e-learning and to some extent, m-learning (mobile learning) are the only means left for universities to retain their student base and ensure they can continue learning throughout the pandemic. Universities in more regional areas and in developing nations have also been hit hard. In these situations, a considerable number of students may not have access to suitable ICT and/or internet access at their home location, so risk falling behind their peers when attempting the switch to e-learning. Universities that have a long history of online education, such as CQUniversity and Charles Sturt University in Australia, and the University of the South Pacific in the Pacific region, are considerably better off in this regard compared to many of the well-established "sandstone" universities, as the transition from "mostly online" to "fully online" is considerably easier to achieve. Furthermore, their student base is also likely to be better prepared in terms of organising access to suitable technology and internet access, as even the face-to-face units offered by such universities typically have a considerable online component/presence associated with the unit (CQUniversity, 2020 ; Rapanta et al., 2020 ).

Since the beginning of the pandemic, many studies have been published documenting university students' readiness towards e-learning and/or learning from home across the globe (Ali, 2020 ; Chung et al., 2020 ; Leacock & Warrican, 2020 ; Naji et al., 2020 ). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published data available on students' e-preparedness from the South Pacific region. Hence, the present study aims to provide insight into the preparedness of first-year students enrolled at the University of the South Pacific towards e-learning in the COVID-19 pandemic context. The University of the South Pacific (USP) occupies a unique status as one of three regional universities in the world, being owned by its 12 member countries: Cook Islands, Fiji Islands, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. With a student roll of about 30,000, USP has 14 campuses and 10 study centres spread over an area of 30 million square kilometres, with at least one campus hosted in each member country. The campuses vary in size and student populations, as well as the available support services and facilities, and modality of delivery. The main campus of USP is located in Fiji, which hosts the university's administrative, academic and commercial operations (Sharma & Reddy, 2015 ; Sharma et al., 2018a , 2019a ). The university offers flexible and distance learning programmes delivered through a variety of modes and technologies, although the majority of students are enrolled in face-to-face programmes. While the university is committed to delivering quality education and adequate learning support to students across its member countries, many students have somewhat limited access to computers and broadband internet, making the shift to online learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic quite a challenge.

The current study aims to investigate the attitudes and perceptions of USP students towards e-learning, their ICT and information literacy competencies, their self-efficacy and their confidence in using technology for learning. It is envisaged that our findings will be useful not only for education providers in the oceanic region but also for regional governments and other education stakeholders in developing nations more globally. Specifically, we aim to address the following research questions:

What is the current status of ICT (technological) literacy for the South Pacific students?

What is the current status of information literacy for the South Pacific students?

How frequently do students participate in various ICT activities?

How confident are students in using ICT products?

What are current student attitudes and perceptions toward the use of computers?

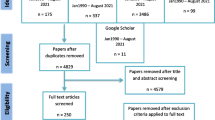

This study uses data collected as part of a PhD study on eLearning and digital literacy by one of the authors (PR). Research and ethics approval was provided by the USP research office. The survey instrument used in this study was a unipolar Likert scale 1–5 questionnaire administered to the students using Google Forms. A copy of the survey instrument is provided in the Additional file 1 . The questions were designed to gain an overview of the e-learning resources available to the students (e.g. type of electronic devices available; type of internet connection), the preparedness of students toward e-learning (e.g. length of time they have been using computers for, amount of time spent on the internet per day, level of ICT troubleshooting skills) and student perceptions or thoughts toward the use of ICT and e-learning. We refer to these aspects as "ICT resources", "ICT literacy" and "ICT perceptions" throughout this paper.

Our study population was first-year undergraduate students enrolled at the University of the South Pacific. Students were surveyed in February 2020 prior to the commencement of their first year of university study. All commencing students at the University of the South Pacific were invited to complete the survey and were given a window of approximately three weeks in which to do so. A total of 313 students opted to provide informed consent and complete the survey. At the closing time of the survey (24 February), there were approximately 83,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 globally, with less than 5000 cases outside of China (World Health Organization, 2020 ). There were no known cases of COVID-19 in any Pacific Island country or territory at this point, with the first case reported in French Polynesia around 17 days later (Craig et al., 2020 ). Hence we consider it unlikely that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted on the student responses in this survey, thus providing an accurate insight into the e-preparedness of first-year students who were predominantly expecting to study face-to-face in the upcoming semester.

In general, the response of USP in moving its teaching and learning online was not a major issue following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, as many courses offered by the university were already facilitated online for distance students. However, emergency remote teaching was a challenge for the university due to the persisting issues including network infrastructure and student access to suitable e-devices and the internet. The unit facilitators encountered many challenges during emergency remote teaching, including the design of assessments and exams to minimise the potential for online teaching, monitoring students' progress, and adjusting assessment due dates to accommodate students whose study had been disrupted as a result of difficulty accessing the internet or other external factors.

The questions that involved a quantizable response (e.g. "how often do you perform the following activities", "how important are the following", "rate yourself on these skills", or "how much do you agree with these statements") were numerically coded in a similar fashion to a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never/not important at all/no capability/strongly disagree) to 5 (frequently/very important/excellent/strongly agree). Statistical analyses were performed in R Studio, running R 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020 ). Students who did not respond to demographic data such as their age bracket, country or program were excluded from subsequent data analysis, leaving a total of 295 valid responses. Students who did not respond to a specific question were excluded from analyses pertaining to that question only.

Results and discussion

Demographics.

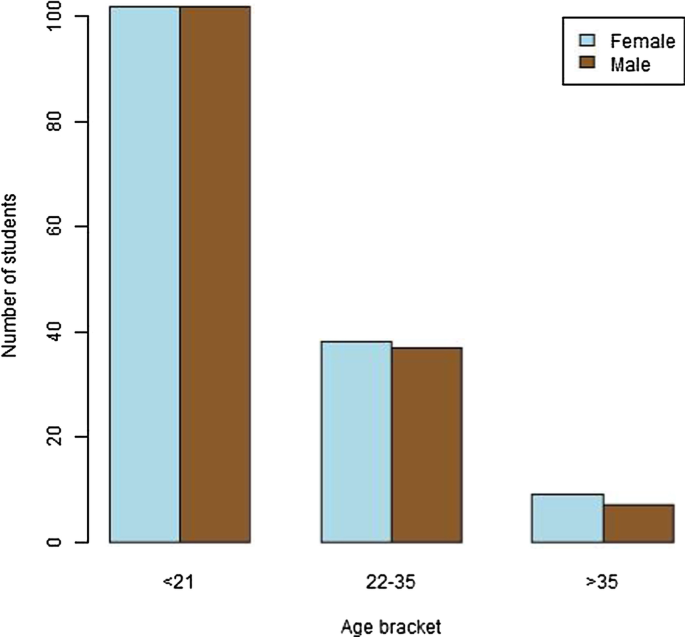

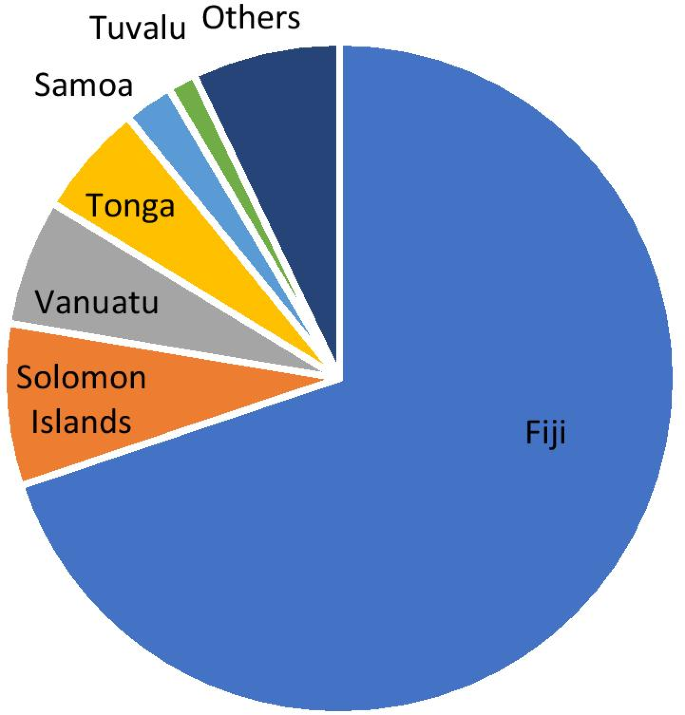

The number of male and female survey respondents were virtually equal, at 49.5% and 50.5% of the total respondents, respectively (Fig. 1 ). The majority of respondents were studying a Science program (60%), followed by Arts (30.8%) and Education (9.2%). Approximately 69.2% of the freshmen students were 21 years of age or under, with 25.4% between 22–35 years of age and the over 35 years age bracket making up the remaining 5.4% of students (Fig. 1 ). The number of respondents from the different Pacific Island countries is illustrated in Fig. 2 . The majority of students (69.8%) were from Fiji, with the next highest numbers of students from the Solomon Islands (7.8%), and Vanuatu (6.1%). Most of these students would normally study face-to-face, with a minority studying online/via distance.

Barplot showing the numbers of male and female students in each age bracket

Breakdown of the survey respondents by their country of residence

ICT resources

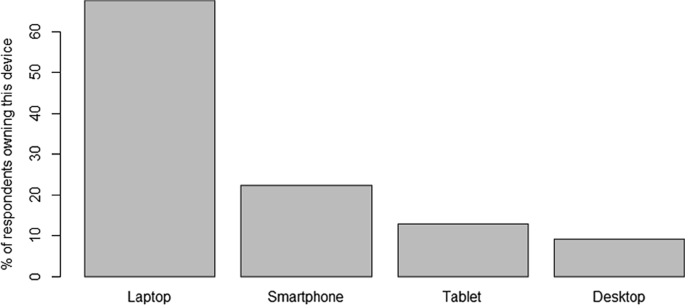

Of the 287 students who provided a valid response as to which ICT devices they own, 88.2% of all students reported owning at least one ICT device. The likelihood of a student owning at least one ICT device was not influenced significantly by their gender, age bracket, nationality or program of study (Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test; P > 0.05 for all). The majority of students (67.6%) owned a laptop, with approximately 9% of students owning a desktop computer and 13% owning a tablet or iPad (Fig. 3 ). Only 22.3% of students reported owning a smartphone in the present study. However, we consider that this low figure is due to most students not interpreting the question ("do you own an ICT device of your own?") as referring to smartphones. Indeed, it has previously been reported that the ownership of mobile devices in the PICs in 2014 was 93% (Reddy et al. 2016 ), which seems more reasonable.

ICT device ownership among the surveyed students. Note that the total percentages do not sum to 100% as some respondents owned more than one type of device

The most common type of internet connection that students reported access to was mobile internet service (57.3% of students), followed by Wi-Fi connection (29.5%). Only 5.9% of students reported access to a Broadband internet service at home, while 7.3% reported access to a Broadband internet service at their university campus. Prior studies conducted in the South Pacific reveal that more people now have access to the internet, with subscriptions increasing every year due to the falling price of internet services and improvements in the network infrastructure (Reddy et al., 2017 , 2020a , 2020b ; Sharma & Reddy, 2015 ; Sharma et al., 2020 ). However, persisting connectivity issues impact on how students access the internet or which internet connection they use (Reddy et al. 2017 , 2020b ). This has resulted in a growing trend toward the use of mobile devices in the South Pacific, as a result of the falling prices and more affordable data plans for mobile devices (Reddy et al., 2016 ). Consequently, surveys conducted among South Pacific students indicated that 90% are in favour of using their mobile phone for learning purposes (Reddy et al., 2017 ), in a trend known as mobile learning (m-learning). This has significant implications for education providers and stakeholders with interest in improving education access equity. Typically, mobile internet access will be slower and more variable compared to Wi-Fi or Broadband access. Furthermore, the data costs (per gigabyte) can be much higher than satellite or cable internet access. On the whole, students who can only access the internet through a mobile phone service are likely to have more restricted access to the internet in general. This can make it harder for them to access online content material, particularly when associated with data-heavy applications such as streaming lecture videos or accessing live tutorial videoconferences.

More recently, government initiatives of providing free Wi-Fi in countries such as Fiji, Vanuatu, Cook Islands, Niue and the Solomon Islands – particularly at higher education centres – have shown an increase in Wi-Fi use. Furthermore, we believe that an increase in internet usage and e-device ownership will continue to increase in the education sector, particularly due to the mandatory shift from the traditional method of face-to-face learning to online learning during and post COVID-19 pandemic. From our personal observations in South Pacific countries, the onset of the pandemic has resulted in internet providers lowering data plan prices, in some cases in collaboration with South Pacific educational institutes to ensure all students have adequate internet access to continue their learning journey.

Student ICT literacy

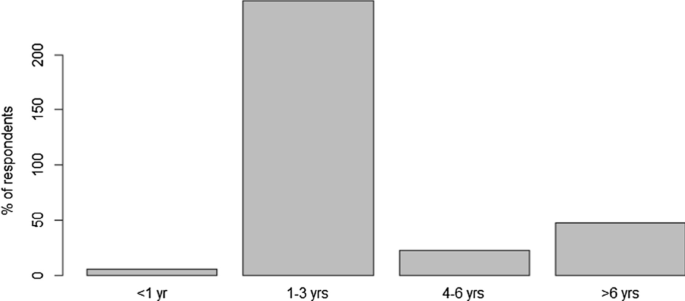

Approximately 47.1% of the students reported having used computers and/or the internet for a time period of longer than 6 years prior to the survey (Fig. 4 ). Only 5.5% of students had used ICT devices for less than one year. However, there was a significant interaction between the length of time students had used ICT and their likelihood of owning at least one ICT device (Fisher's Exact test; P < 0.05). Students who had used ICT for 1–3 years were much less likely to own an ICT device than expected by chance, while students who had used ICT for over 3 years were more likely to own an ICT device.

Number of years of experience using ICT devices among the surveyed students

The majority of students (60.7%) reported spending between 1–4 h per day on the internet for university or school-related purposes, with around a fifth spending 5–8 h per day on these activities (Table 1 ). Over 6% of students used the internet for over 9 h each day for university purposes. Slightly more students than this (9.8%) used the internet for over 9 h each day for edutainment, which can be loosely interpreted as media intended to be both educational and enjoyable. As defined in the survey provided to students, this includes purposes such as games, music, videos and social networks. Students' distribution across the other three-time brackets for edutainment followed an approximately normal distribution, with almost half (46%) spending 1–4 h on it per day.

Further breakdown of time spent on the internet revealed that students reported their most frequent activity as email, followed by accessing online educational resources and communication (through non-email means such as Skype, Viber, Facebook or online forums) and social networking (Table 2 ). The majority of students reported accessing their online educational resources "very often" and reading free course content "sometimes".

A common definition of ICT literacy is "an individual's ability to use computers to investigate, create, and communicate in order to participate effectively at home, at school, in the workplace, and society" (Fraillon et al., 2013 ). Hence, it is informative to assess the length of time spent and activities performed by students using ICT and their efficacy at performing various common ICT-related tasks. In general, the students in this cohort reported strong skills in computers' technical use (Table 3 ). Their average information literacy was a little lower compared to their technical capabilities. Still, it ranged between "good" and "excellent" for the majority of students. In the South Pacific the concept of information literacy is growing. For example, the current cohort of university students surveyed for this study have to complete a compulsory information literacy unit in their first year of their study (Reddy et al., 2020d ). Therefore, the current student cohort's information literacy competencies should also improve significantly throughout their study when compared to their other literacies.

Student attitudes towards ICT

The majority of students (55.6%) reported either "loving" or "liking" new technology and that they were usually the first to try new technology among their acquaintances. Only 19% of students reported that they "were not used to new technology" or were "one of the last people to try new technology", suggesting an overall positive attitude and interest towards ICT among the student cohort.

The most important uses of e-learning, as reported by the student cohort, were for video/audio tutorials, email groups and open education resources (Table 4 ). Only a few students reported the use of education games, blogs, social networking sites or wikis/podcasts for education purposes. Most students were moderately to strongly confident in their abilities to use technology, although not necessarily with troubleshooting computer problems (Table 5 ).

Virtually all students reported a positive attitude toward the use of technology in the learning process, particularly for keeping connected to their course material and accessing a wide range of educational resources (Table 6 ).

General discussion

The current study shows that of the 88% of participants who own at least one ICT device, all have access to the internet in some form, whether it be through mobile data, Wi-Fi or broadband, either on campus or at home. In comparison with prior such studies, the study noted an increase in device ownership and Internet accessibility for the South Pacific countries. Given that all participants of this study were students from USP, they would also have access to university computer labs across all campuses which can be utilised for learning purposes, in addition to their personal e-devices. Furthermore, the university also provides free Wi-Fi access at all campuses so that students who do not have personal access to the internet can use the services provided at the campuses. Overall, these are quite positive trends toward the uptake of digital technologies across the South Pacific region and the current and future potential for e-learning. This concurs with previous studies reporting that technology-enabled learning has been well received by most students (Raturi, 2018 ; Reddy et al., 2019 ; Sharma et al., 2020 , 2019b ). Although there have been drawbacks, as discussed in the introductory sections, initiatives to improve the facilitation of technology-enabled learning from the higher education stakeholders in the South Pacific have been put in place by government agencies and researchers. These include the provision of ICT devices and training to students in need.

In terms of the technological competency of the students, the overall response was noted to be above average, indicative of widespread technological acceptance. The results for the usage of digital technology indicated that the participants mostly used their technology for accessing and sending emails, followed by accessing online educational resources and social networking websites. The high competency of students in using emails is prominent as a result of all USP students being issued with a university email address. Similarly, USP facilitates at least some portion of all courses through an online learning management system (Moodle), thus accessing educational resources through this platform is expected to be a regular part of their study experiences. In contrast, students’ usage of digital library resources and free online course content was considerably lower, predominantly ranging from “rarely” to “sometimes” in the former instance. Hence, we believe that as commencing first-year students, they may have lacked knowledge about these aforementioned resources. A study conducted by Reddy et al. ( 2020c ) similarly revealed that students in the South Pacific lack digital literacy knowledge, suggesting that more outreach efforts and awareness programs are needed to expose the students to the latest digital literacy trends. In other words, students from the South Pacific appear to generally have sufficient technological skills, but may require further support with their digital literacy (finding academically sound information, judging its reliability, etc.). Various initiatives have been put in place in the South Pacific to impart and solidify students’ computer skills, including:

A framework for Pacific Regional Framework 2018–2030 – Moving Towards Education 2030, which includes increasing students’ digital literacy (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2018 )

The National Framework of Digital Literacy in Fiji, which includes programmes for students from Year 1 – Year 12

The SchoolNet Project in Samoa to incorporate e-learning and increase the use of computers at secondary and primary schools, run by the Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility

Pilot trial of one laptop per child (OLPC) initiative in Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Island, Tonga and Vanuatu, run by the Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility

Provision of ICT training by the USP to around 860 primary school students and 680 parents in the Western division of Fiji (Yusuf, 2009 )

Overall, the attitude of the majority of students towards online learning was positive. The students perceived that online learning connected them more with their peers and facilitators, gave them access to wider range of learning materials, made the learning process more creative and enabled self-paced learning. This agrees with a recent study conducted in the South Pacific by Reddy et al., ( 2020a ), who found that the aforementioned benefits of online learning resulted in the positive attitudes toward technology, ensuring that students were open to continued use of e-learning.

As the present study was conducted just prior to the arrival of COVID-19 in the South Pacific and before all higher education institutes had to move their delivery mode online (USP, 2020a ), it provides an insight into the “typical” level of e-preparedness among students from the Pacific Island Countries. The majority of students in this study showed high levels of e-preparedness, indicating that they would be expected to be somewhat ready for the transition from face-to-face to online learning. This agrees with anecdotal observations during the pandemic, where it was reported that the semester and exams were able to progress via an online format with minimal disruptions and participation rates of up to 80% (USP, 2020b ). In contrast, Chung et al. ( 2020 ) reported that over 50% of Malaysian students did not wish to continue with e-learning following the COVID-19 pandemic. The key challenges identified by these students were internet connectivity, a lack of continuity in the online delivery methods used by different lecturers, and difficulty understanding online content provided by lecturers (Chung et al., 2020 ). This highlights the digital competency of university educators and staff as another important facet of e-learning (Ali, 2020 ). Indeed, high levels technological and digital literacy among educators was identified by several authors to be a key factor in the successful transition to online learning (Chung et al., 2020 ; Naji et al., 2020 ; Rapanta et al., 2020 ).

Despite these promising results found amongst students from the South Pacific, ongoing work is necessary to identify and assist students experiencing difficulty in accessing and using digital technology to assist their learning process. This highlights the importance for universities to maintain awareness of the e-capabilities of their student population, perhaps through the use of surveys such as the one presented in this study, or the Student Experience of Learning and Teaching (SELT) survey. This will assist these institutions in delivering a robust system of education that can adapt to future challenges.

The increasing use of online modes of content delivery has the benefit of increasing convenience for students, by allowing them to choose where and when to learn, but also has the potential to improve equitable access to education by providing students in geographically remote locations with the option to pursue tertiary education without having to relocate to a more urban locality. However, a number of challenges to this approach remains, including ensuring equitable access to suitable technology and internet connections, maintaining high quality in online learning resources and ensuring the learning outcomes of online students are comparable to those achieved through face-to-face classes.

Following the recent outbreak of COVID-19, education providers worldwide have been forced to turn to e-learning to retain their student base and allow them to continue learning through the pandemic. However, in geographically remote, developing nations, many students may not have access to suitable technology or internet at their home location but are rather dependent upon face-to-face classes at their local university campus to allow them to participate in higher education.

This study found that among the commencing 2020 cohort of students at the University of the South Pacific, 88% possessed at least one ICT device and access to the internet. Similarly, most students had adequate to strong ICT skills and a positive attitude toward e-learning. These attitudes among the student cohort, in conjunction with the previous experience of The University of the South Pacific in distance education, are likely to have contributed to the relatively successful transition from face-to-face to online learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational institutes should maintain ongoing awareness of the e-capabilities of the student cohorts in order to be best prepared for future challenges to the educational sector.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset is available from the authors upon request.

Change history

14 april 2021.

The original publication was missing its supplementary files. The article has been updated to include the missing files.

ADB. (2019). Samoa: SchoolNet and community access project. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/documents/samoa-schoolnet-and-community-access-project . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education, 10 (3), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16 .

Article Google Scholar

Ansong-Gyimah, K. (2020). Students’ perceptions and continuous intention to use e-learning systems: The case of Google Classroom. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15 (11), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i11.12683 .

Arasaratnam-Smith, L. A., & Northcote, M. (2017). Community in online higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 15 (2), 188–198.

Google Scholar

Arshavskiy, M. (2017). eLearning evolution - the 3 biggest changes in 5 years and how to adapt to them for success. Retrieved from https://www.shiftelearning.com/blog/elearning-evolution-the-biggest-changes . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Baxley, G.K. (2018). The benefits of online learning: The use of an e-component to enhance academic achievement scores in face-to-face classrooms. (Ph.D.). Trident University International, Ann Arbor. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2064442685 ProQuest One Academic database. (10829951). Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Beinicke, A., & Bipp, T. (2018). Evaluating training outcomes in corporate e-learning and classroom training. Vocations and Learning, 11 (3), 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9201-7 .

Bhuasiri, W., Xaymoungkhoun, O., Zo, H., Rho, J. J., & Ciganek, A. P. (2012). Critical success factors for e-learning in developing countries: A comparative analysis between ICT experts and faculty. Computers & Education, 58 (2), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.010 .

Bhuvaneswari, S. S. B., & Dharanipriya, A. (2020). Attitude of UG students towards e-learning. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 9 (2), 35–40.

Chandra, S., & Sharma, B. (2018). Near, far, wherever you are: Chemistry via distance in the South Seas. American Journal of Distance Education, 32 (2), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2018.1440106 .

Chillemi, O., Galavotti, S., & Gui, B. (2020). The impact of data caps on mobile broadband Internet access: A welfare analysis. Information Economics and Policy, 50, 100843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2019.100843 .

Chung, E., Subramaniam, G., & Christ Dass, L. (2020). Online learning readiness among university students in Malaysia amidst Covid-19. Asian Journal of University Education, 16 (2), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v16i2.10294 .

Cotten, S. R., Davison, E. L., Shank, D. B., & Ward, B. W. (2014). Gradations of disappearing digital divides among racially diverse middle school students. In L. Robinson, S. R. Cotten & J. Schulz (Eds.), Communication and Information Technologies Annual (Vol. 8, pp. 25–54). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2050-206020140000008017 .

CQUniversity. (2020, 19 Mar 2020). Online learning has its time in the sun, as unis cope with COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.cqu.edu.au/cquninews/stories/general-category/2020-general/online-learning-has-its-time-in-the-sun,-as-unis-cope-with-covid-19 . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Craig, A. T., Heywood, A. E., & Hall, J. (2020). Risk of COVID-19 importation to the Pacific islands through global air travel. Epidemiology and Infection, 148, e71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268820000710 .

Dospinescu, O., & Dospinescu, N. (2020). Perception over e-learning tools in higher education: comparative study Romania and Moldova. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the IE 2020 International Conference, Madrid, Spain, pp. 59–64. https://doi.org/10.24818/ie2020.02.01 .

Dursun, T., Oskaybas, K., & Gokmen, C. (2014). Perceived quality of distance education from the user perspective. Contemporary Educational Technology, 5 (2), 121–145.

Fayram, J., Boswood, N., Kan, Q., Motzo, A., & Proudfoot, A. (2018). Investigating the benefits of online peer mentoring for student confidence and motivation. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7 (4), 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-10-2017-0065 .

Fraillon, J., Schulz, W., & Ainley, J. (2013). Students’ computer and information literacy. In J. Fraillon, J. Ainley, W. Schulz, T. Friedman, & E. Gebhardt (Eds.), International computer and information literacy study: Assessment framework (pp. 69–100). Cham: Springer.

Gardner, J., & Brooks, C. (2018). Student success prediction in MOOCs. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 28 (2), 127–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-018-9203-z .

Graham, A. (2019). Benefits of online teaching for face-to-face teaching at historically black colleges and universities. Online Learning, 23 (1), 144–163.

Heirdsfield, A., Walker, S., Tambyah, M., & Beutel, D. (2011). Blackboard as an online learning environment: What do teacher education students and staff think? Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 36 (7), 1.

Henderson, M., Selwyn, N., & Aston, R. (2017). What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘useful’ digital technology in university teaching and learning. Studies in Higher Education, 42 (8), 1567–1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007946 .

Hollenbeck, C. R., Zinkhan, G. M., & French, W. (2005). Distance learning trends and benchmarks: Lessons from an online MBA program. Marketing Education Review, 15 (2), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2005.11488904 .

Huang, K.-T., Cotten, S. R., & Rikard, R. V. (2017). Access is not enough: the impact of emotional costs and self-efficacy on the changes in African-American students’ ICT use patterns. Information, Communication & Society, 20 (4), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1203456 .

Irfan, M., Putra, S. J., & Alam, C. N. (2018). E-Readiness for ICT implementation of the higher education institutions in the Indonesian. Paper presented at the 2018 6th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Parapat, Indonesia, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/CITSM.2018.8674330 .

Kashive, N., Powale, L., & Kashive, K. (2020). Understanding user perception toward artificial intelligence (AI) enabled e-learning. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 38 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-05-2020-0090 .

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46 (1), 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713 .

Kilburn, A., Kilburn, B., & Cates, T. (2014). Drivers of student retention: System availability, privacy, value and loyalty in online higher education. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 18 (4), 1.

Lalande, V. (1995). Student support via audio teleconferencing: Psycho-educational workshops for post-bachelor nursing students. American Journal of Distance Education, 9 (3), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923649509526898 .

Latchem, C. (2017). Using ICTs and blended learning in transforming technical and vocational education and training . Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Layali, K., & Al-Shlowiy, A. (2020). Students’ perceptions of e-learning for ESL/EFL in Saudi universities at time of coronavirus: A literature review. Indonesian EFL Journal (IEFLJ), 6 (2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.25134/ieflj.v6i2.3378 .

Leacock, C. J., & Warrican, S. J. (2020). Helping teachers to respond to COVID-19 in the Eastern Caribbean: issues of readiness, equity and care. Journal of Education for Teaching . https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1803733 .

Lim, C. P., Ra, S., Chin, B., & Wang, T. (2020). Leveraging information and communication technologies (ICT) to enhance education equity, quality, and efficiency: case studies of Bangladesh and Nepal. Educational Media International, 57 (2), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2020.1786774 .

Littlejohn, A., Hood, N., Milligan, C., & Mustain, P. (2016). Learning in MOOCs: Motivations and self-regulated learning in MOOCs. The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.12.003 .

Machado-Da-Silva, F. N., Meirelles, Fd. S., Filenga, D., & Brugnolo Filho, M. (2014). Student satisfaction process in virtual learning system: Considerations based in information and service quality from Brazil’s experience. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 15 (3), 122–142.

Mahajan, M. V. (2020). A study of students’ perception about e-learning. Indian Journal of Clinical Anatomy and Physiology, 5 (4), 501–507. https://doi.org/10.18231/2394-2126.2018.0116 .

Martínez-Argüelles, M. J., Blanco Callejo, M., & Castán Farrero, J. M. (2013). Dimensions of perceived service quality in higher education virtual learning environments. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 10 (1), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v10i1.1411 .

Milakovich, M.E., & Wise, J.-M. (2019). Digital learning. In: Overcoming the digital divide: achieving access, quality, and equality. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788979467

Miltiadous, A., Callahan, D. L., & Schultz, M. (2020). Exploring engagement as a predictor of success in the transition to online learning in first year chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 97 (9), 2494–2501. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00794 .

Mousavi, A., Mohammadi, A., Mojtahedzadeh, R., Shirazi, M., & Rashidi, H. (2020). E-Learning Educational Atmosphere Measure (EEAM): A new instrument for assessing e-students’ perception of educational environment. Research in Learning Technology, 28, 2308. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v28.2308 .

Naiker, M., Wakeling, L., & Aldred, P. (2013). The relevance of chemistry practicals-first year students’ perspective at a regional university in Victoria, Australia. Paper presented at the Proceedings of The Australian Conference on Science and Mathematics Education (formerly UniServe Science Conference), Sydney, Australia, pp. 169–173. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IISME/article/view/7015 .

Naiker, M., & Wakeling, L. (2015). Evaluation of group based inquiry oriented learning in undergraduate chemistry practicals. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education, 23 (5), 1–17.

Naji, K. K., Du, X., Tarlochan, F., Ebead, U., Hasan, M. A., & Al-Ali, A. K. (2020). Engineering students’ readiness to transition to emergency online learning in response to COVID-19: Case of Qatar. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16, 10.

Olt, M. R. (2002). Ethics and distance education: Strategies for minimizing academic dishonesty in online assessment. Online journal of distance learning administration, 5 (3), 1–7.

Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2018). Pacific regional education framework (PacREF) 2018 - 2030: Moving towards education 2030 . Retrieved from https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Pacific-Regional-Education-Framework-PacREF-2018-2030.pdf . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Pham, L., Limbu, Y. B., Bui, T. K., Nguyen, H. T., & Pham, H. T. (2019). Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16 (1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0136-3 .

Phirangee, K., & Hewitt, J. (2016). Chapter 4—Loving this dialogue!!!!: Expressing emotion through the strategic manipulation of limited non-verbal cues in online learning environments. In S. Y. Tettegah & M. P. McCreery (Eds.), Emotions, Technology, and Learning (pp. 69–85). San Diego: Academic Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Rafiq, F., Hussain, S., & Abbas, Q. (2020). Analyzing students’ attitude towards e-learning: A case study in higher education in Pakistan. Pakistan Social Sciences Review, 4 (1), 367–380.

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science and Education, 2 (3), 923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y .

Raturi, S. (2018). Understanding learners preferences for learning environments in higher education. The Online Journal of Distance Education and e-Learning, 6 (3), 84–100.

Reddy, E., Reddy, P., Sharma, B., Reddy, K., & Khan, M. G. M. (2016). Student readiness and perception to the use of smart phones for higher education in the Pacific. Paper presented at the 2016 3rd Asia-Pacific World Congress on Computer Science and Engineering (APWC on CSE), Nadi, Fiji, pp. 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1109/APWC-on-CSE.2016.049 .

Reddy, E., Sharma, B., Reddy, P., & Dakuidreketi, M. (2017). Mobile learning readiness and ICT competency: A case study of senior secondary school students in the Pacific Islands. Paper presented at the 2017 4th Asia-Pacific World Congress on Computer Science and Engineering (APWC on CSE), Mana Island, Fiji, pp. 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1109/APWConCSE.2017.00031 .

Reddy, P., Chaudhary, K., & Sharma, B. (2019, 9–11 Dec. 2019). Predicting media literacy level of secondary school students in Fiji. Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Melbourne, Australia, pp. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/CSDE48274.2019.9162411 .

Reddy, P., Chaudhary, K., Sharma, B., & Chand, R. (2020a). The two perfect scorers for technology acceptance. Education and Information Technologies . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10320-2 .

Reddy, P., Sharma, B., & Chandra, S. (2020b). Student readiness and perception of tablet learning in higher education in the Pacific—A case study of Fiji and Tuvalu: Tablet learning at USP. Journal of Cases on Information Technology (JCIT), 22 (2), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.4018/JCIT.2020040104 .

Reddy, P., Sharma, B., & Chaudhary, K. (2020c). Measuring the digital competency of freshmen at a higher education institute. Paper presented at the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Dubai, UAE, pp. 1–12. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2020/6

Reddy, P., Sharma, B., & Chaudhary, K. (2020). Digital literacy: A review of literature. International Journal of Technoethics (IJT), 11 (2), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJT.20200701.oa1 .

Sakarji, S. R., Nor, K. B. M., Razali, M. M., Talib, N., Ahmad, N., & Saferdin, W. (2019). Investigating student’s acceptance of e-learning using technology acceptance model among diploma in office management and technology students at Uitm Melaka. Journal of Information, 4 (13), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.35631/JISTM.413002 .

Scherer, R., & Siddiq, F. (2019). The relation between students’ socioeconomic status and ICT literacy: Findings from a meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 138, 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.011 .

Sharma, B., & Reddy, P. (2015). Effectiveness of tablet learning in online courses at University of the South Pacific. Paper presented at the 2nd Asia-Pacific World Congress on Computer Science and Engineering (APWC on CSE), Nadi, Fiji, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/APWCCSE.2015.7476229 .

Sharma, B., Lauano, Fi. J., Narayan, S., Anzeg, A., Kumar, B., & Raj, J. (2018a). Science teachers accelerated programme model: A joint partnership in the Pacific region. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 46 (1), 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2017.1359820 .

Sharma, B. N., Nand, R., Naseem, M., Reddy, E., Narayan, S. S., & Reddy, K. (2018b). Smart learning in the Pacific: Design of new pedagogical tools. Paper presented at the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE), Wollongong, Australia, pp. 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE.2018.8615269 .

Sharma, B., Prasad, A., Narayan, S., Kumar, B., Singh, V., Nusair, S., & Khan, G. (2019a). Partnerships with governments to implement in-country science programmes in the South Pacific region. Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Melbourne, Australia, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/CSDE48274.2019.9162419 .

Sharma, B. N., Reddy, P., Reddy, E., Narayan, S. S., Singh, V., Kumar, R., & Prasad, R. (2019b). Use of mobile devices for learning and student support in the Pacific region. In Y. Zang & D. Crsitol (Eds.), Handbook of mobile teaching and learning (pp. 109–134). Cham: Springer.

Sharma, B., Nand, R., Naseem, M., & Reddy, E. V. (2020). Effectiveness of online presence in a blended higher learning environment in the Pacific. Studies in Higher Education, 45 (8), 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1602756 .

USP. (2020a). The University of the South Pacific: COVID-19 pandemic management plan . Retrieved from Fiji: https://www.usp.ac.fj/fileadmin/files/services/prop_facil/OHS/COVID-19/Pandemic-Plan-2020/COVID-19-USP-Response-Plan-2020.pdf . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

USP. (2020b, 27 Jul 2020). COVID-19 and its impact on the 2020 academic year. Retrieved from https://www.usp.ac.fj/news/story.php?id=3272 . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

van Popta, E., Kral, M., Camp, G., Martens, R. L., & Simons, P.R.-J. (2017). Exploring the value of peer feedback in online learning for the provider. Educational Research Review, 20, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.10.003 .

Wakeling, L., Naiker, M., Gopalan, R.D., & Voro, T. (2014). Investigating first-year chemistry students perception of the relevance of practicals at the University of the South Pacific, Fiji. Paper presented at the The Australian Conference on Science and Mathematics Education, Sydney, ISBN Number 978-0-9871834-3-9. http://repository.usp.ac.fj/10001/1/Wakeling_ACSME_abstract.pdf .

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report—39 . Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200228-sitrep-39-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=5bbf3e7d_4 . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

Wu, B. (2016). Identifying the influential factors of knowledge sharing in e-learning 2.0 systems. International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems (IJEIS), 12 (1), 85–102.

Yang, H. H., Zhu, S., & MacLeod, J. (2018). Promoting education equity in rural and underdeveloped areas: Cases on computer-supported collaborative teaching in China. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14 (6), 2393–2405. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/89841 .

Yusuf, J. (2009). Flexible delivery issues: The case of the University of the South Pacific. International Journal of instructional Technology and Distance Education, 6 (6), 65–71.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the University of the South Pacific for their assistance with data collection.

No specific funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity, North Rockhampton, QLD, Australia

Joel B. Johnson & Mani Naiker

Department of Computing Science and Information Systems, Fiji National University, Suva, Fiji

Pritika Reddy & Ronil Chand

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PR and RC collected the data; JJ conducted the data analysis and prepared the initial manuscript draft; all authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joel B. Johnson .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from The University of the South Pacific's Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to data collection. Participants were able to decline participation or withdraw at any point of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Survey Instrument.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Johnson, J.B., Reddy, P., Chand, R. et al. Attitudes and awareness of regional Pacific Island students towards e-learning. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 18 , 13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00248-z

Download citation

Received : 20 November 2020

Accepted : 16 February 2021

Published : 11 March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00248-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Distance education

- First-year undergraduates

- Preparedness

Nursing student´s attitudes toward e-learning: a quantitative approach

- Open access

- Published: 13 August 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 2129–2143, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Alina de las Mercedes Martínez Sánchez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1170-6976 1 &

- Abdullah Karaksha ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0498-4209 2

5583 Accesses

5 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

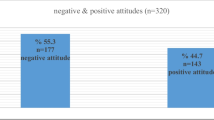

This article seeks to determine the attitudes of undergraduate nursing students toward e-learning at the (X). A quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive, and exploratory approach was the procedural methodology selected in this study. A suitable sample of sophomore nursing scholars (n = 71) was registered. A total of 58 students returned the questionnaire (82.8% were females). Students who have previous computer training were significantly more confident in connecting to the internet than those with no prior computer training (t = 2.1, p < 0.05). Students who had prior experience in e-learning predicted they would feel significantly more nervous when working with computers than those who did not have this prior experience (t = 2.3, p < 0.05). In general, our investigation uncovered a differently favorable view of nursing students towards e-learning, however, some negative attitudes were also recorded. Factors likes students` motivation and personalities, backgrounds and feelings related to the control of their educational process must be considered in the application of e-learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effect of educational program on the psychological challenges of electronic learning among university nursing students: a quasi-experimental study

Bakheeta AbdEl-Aziz Mohammed, Ikram Ibraheem Mohammed, … Amera Azzet Abd El-Naser

Determining attitudes toward e-learning: what are the attitudes of health professional students?

Ayla Güllü, Mustafa Kara & Şenay Akgün

Advances in e-learning in undergraduate clinical medicine: a systematic review

T. Delungahawatta, S. S. Dunne, … C. P. Dunne

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Electronic learning (e-learning) in healthcare teaching was positioned as an important innovation in education for healthcare professionals. The academic setting is one of the most contexts analyzed concerning to nursing education to develop abilities required, regarding to perform competencies related to nursing care practice (Rouleau et al., 2019 ).

E-learning is an internet or network-based training method, which comprises a set of instructions provided over electronic media systems (Omar et al., 2012 ). Debate over an accurate definition of e-learning is still in progress; though it is widely accepted that e-learning is a variety of contents delivered in different formats, i.e., text, video, or image patterns, and electronically offered via internet, laptop, personal digital assistant (PDA) or CD-ROM (Behera, 2013 ). Despite the diversity of the contents that define e-learning, benefits of the system have been widely documented (Basha, 2020 ; Marengo, 2005 ; Regmi & Jones, 2021 ).

Due to the need of nurses to access up-to-date information on illnesses, medicines, and proficiency, e-learning is of great value to nursing practice (Kadioglu et al., 2020 ). The advantages of online learning systems on nursing students have been widely documented (Gerkin et al., 2009 ; Koivisto et al., 2017; Pront et al., 2018 ; Seada, 2017 ) and most studies show high levels of satisfaction among students on the use of online learning systems. Likewise, nursing students often refer to advantage and approach as the primary reasons to take online courses. In accordance, some advantages of e-learning have been described. E-learning reduces education costs; e-learning content is punctual and more trustworthy, with an end-to-end learning procedure and the creation of worldwide groups through online interconnection (Ruggeri et al., 2013 ). Compared with the conventional method, e-learning is cheaper to achieve, self-paced (e-learning courses can be taken when required), quicker (known material can be skipped) and provides more reliable content (traditional education focus on diverse teachers` approach on the same subject) (Cheng, 2012; Jung 2011 ). The challenging issues of clinical conditions in nursing education limit the student-patient connection within the traditional didactic education. Furthermore, restricted clinical hours and deployments, unreliable existence of patients with illnesses, and each patient’s singularity and their support system make the achievement of a high-quality teaching experience for the students even harder (Pfefferle & Stock 2010 ).

Several authors highlight the benefit of online education in nursing instruction (Morente et al., 2013 ; Vaona et al., 2018 ; Wasmiy & Noha 2014 ). Recently, flexibility in nature regardless of learner geographical place and material access were described as one of the e-learning advantages (Regmi & Jones, 2020 ). In addition, e-learning has been recognized for continuing professional development for medical and nursing students (Ota et al., 2018 ). Online education has also been said to result in an enhanced preservation and a greater hold on the topic since lots of aspects that are fused in e-learning highlight the communication, namely video, audio, and quizzes interface. Moreover, e-learning can be simply achieved for large groups of learners (Gross, 2018 ). Consistent with Keefe & Wharrad ( 2012 ), nursing scholars who interface with virtual patients in preconceived situations may prevent unwarranted risks in meetings with real patients.

There is the fact that students might sometimes reject e-learning. The successful execution of e-learning tools relies upon the users’ knowledge and skills on computers. Such ingredients are said to involve users’ primary endorsement of computer equipment and their hereafter attitude on the use of web-based learning systems (Kim & Moore, 2005 ; Jones & Jones, 2005 ). In addition, positive attitudes towards e-learning lead to major chances that learners will adopt this new learning system (Zabadi & Al-Alawi, 2016 ).

On the contrary, recent studies report negative and uncertain nursing students´ attitudes about e-learning (Soriano & Oducato, 2021 ; Nsouli & Vlachopoulos 2021 ; Hvalič-Touzery et al., 2017). Some nursing students consider that face to face lectures increase student knowing more than e-learning classroom (Omolola et al., 2016 ). The assimilation and application of e-learning has changed and evolving, as are student outlooks. Though the availability of the current academic techniques, teaching and learning are not stimulated by e-learning. Achieving a much better comprehension of students’ disposition upon e-learning will give educators deeper vision and prospect for developing strategies that match students’ needs (Williams et al., 2011 ).

To add another layer of complexity, previous research suggested that gender may play a role towards e-learning preference. Males usually have positive experience with technology while females do not like to learn from computers and prefer person-to-person learning (Ausburn et al., 2009 & Johnson,. D. 2011). Another research has suggested that age could impact student performance and interaction with technology (Willey, T., Edwards, S., & Nonchalkier, V. 2008).

Before moving forward in applying this new teaching approach, there is a need to obtain more information concerning nursing students’ attitudes towards e-learning, and to determine in what way it could best be implemented for nursing scholars. As mentioned before, E-learning is becoming more essential to the future of nurse education and the facilitation of lifelong learning because of its benefits to extend learning and culture beyond the classroom. Therefore, it is important to examine student expectations concerning of this new learning method (McVeigh, 2009 ), so foundations and strategies to manage barriers toward e-learning can be designed and implemented. Additionally, research conducted to explore nursing students’ attitudes toward e-learning is important considering that it has been encouraged for its ability to captivate learners, customize the learning process and successful implementation in clinical skill acquisition (Bloomfield, 2013 ). Similarly, the relevance of studies related to the application of e-learning in nursing education has been supported from the perspective of the necessity to perform computer information technology staff development that is of high quality, accessible and tailored to enhance the increasing role information technology has in teaching and learning and the nursing profession (Button et al., 2014 ). Likewise, e-learning instruction method has shown evidence-based insights in nursing clinical practice to improve professional competences (Beeckman et al., 2008 ).

To evaluate the impact of e-learning tools, we followed Kirkpatrick ( 1996 ), who presented a 4-level evaluation model comprising reaction (1), learning (2), behaviour (3), and results (4). Our study is interested in the first level of evaluation, the reaction, as it measures the students’ perception, interest and motivation of the e-learning tools (Kirkpatrick, 1996 ). Therefore, this article seeked to determine the attitudes of undergraduate nursing students toward e-learning at the (X).

The following assumptions were proposed:

H 1 : A correlation exists between gender and internet self-efficacy toward e-learning.

H 2 : A relation exists between computer training and learner computer anxiety.

H 3 : A correlation exists between prior experiences of e-learning and students’ positive attitudes towards computers.

2 Research methodology

2.1 research design.

A quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive, and exploratory approach was the procedural methodology selected in this study. In the view of Rincon et al., ( 2003 ), survey-based analyses are frequently used in the discipline of education perhaps owing to the evident ease and openness of this method. Campoy & Pantoja ( 2000 ) highlight surveys’ skill to oversimplify results achieved in the population as one of their main benefits. This study used a descriptive method because it best fit our intentions, consistent with the concepts by Fox ( 1987 ), who explains the use of the descriptive approach in educational research by virtue of the absence of information, its production and availability.

2.2 Participants

The designed survey was sent to sophomores nursing students who are enrolled in the course Pharmacology for Nursing at the Physiotherapy and Nursing University School, (“X”). The students were chosen using a convenience sampling. Convenience sampling is widely held since it is not costly, not as time expending as other sampling strategies, and simplistic. When used to generate a potential hypothesis or study objective, convenience sampling is effective. When no other sampling method is feasible, convenience sampling can be used to develop hypotheses and objectives for use in more rigorous research studies (Stratton, 2021 ). According to our objectives, the individuals used in the research are selected because they are readily available and because we know they belong to the population of interest. The prevalence of sampling through non-probabilistic methods (pseudo-random, empirical or snowball) in educational research (Mayorga & Ruiz, 2002).

2.3 Ethical considerations

The Human Ethics Committee from (“X”) deemed the study exempt from review. All nursing students in the second year of the bachelor’s program were informed verbally about the study one week prior to implementation. Participating in the study was voluntary and anonymity was guaranteed. Neither e-mail addresses nor other personal data were included within online questionnaires to avoid revealing respondents’ identities.

2.4 Measurement

After an extensive scientific articles review (Fan, 2005 , Maag, 2006 , Ali, 2012 , Chong et al., 2016 , Akimanimpaye, 2015 ) an ad hoc questionnaire was designed incorporating Semantic Differential Scales measuring attitudes (Guillasper et al., 2020 ). The instrument consisted of three sections: (1) demographic information (age, gender, pathway to study nursing, experience with an e-learning), (2) self-assessment related to the position in relation to computers, learner’s computer uneasiness (seven items), and (3) internet self-efficiency (eight items). The last two sections were designed to determinate students’ attitudes towards the use of computers in their learning process, and their confidence in using computers in their learning, respectively. Five-point Likert scales that range from vigorously dissent to actively consent was utilized for opinion level scaling. An “I don’t know” option was included in the scale to close the gap produced between what students really know and the scores they get. This approach helps participations to avoid making a guess when they are not aware of the answer (Singh, 2001 ).

For the reliability of the instrument, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients was determined. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the 15-item attitude toward e-learning (Sect. 2 and Sect. 3) scale was 0.88 and 0.7, respectively (Table 1 ). Therefore, internal consistency of the questionnaire was adequate—an alpha value on top of 0.7 suggests acceptable reliability according to sources (Schrepp, 2020 ). Overall, the instrument had a good internal consistency resulting in a reliable tool to measure attitudes towards e-learning.

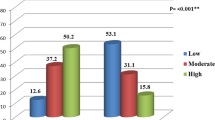

To further assess the validity of the questionnaire, a pilot test was carried out amongst 10 undergraduate nursing students to ensure that the questionnaire precisely addressed the research questions, there were no confusing questions, and that all items were evaluated. No changes were made to the questionnaire based on the results of the pilot test. However, students who contributed to the pilot test were omitted from the study.